Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This article discusses the possibilities of audiovisual records as research data in intercultural relationships, or those that allow us to understand the Other. The research aims to contribute to the theory that is being developed on the nature and value of narratives in photographic and video representation and analysis of basic realities of teaching that are difficult to capture and quantify. Specifically, we examine whether audiovisual recording is a good tool for gathering and analysing information about intentions and interpretations contained in human relationships and practices. After presenting some epistemological and methodological dilemmas such as the crisis of representation in the social sciences or the «etic-emic» conflict and proposing some solutions taken from audiovisual anthropology, we analyse the nature of intercultural relationships in two schools –ethnographies– that support the study completed in 2011 and funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation: the use of visual narratives as a substrate of intercultural relationships between culturally diverse kindergarten and primary education pupils. As an example, we describe how we discovered some categories that allow us to understand the universe of meanings that make sense of, determine and shape their cultural relations. Finally, we describe the contributions of NVivo 9, a software package that facilitates the analysis of photo and video recordings and narratives.

1. Introduction

Research since the 1980s on teaching processes has revealed the dilemma addressed in this article: the existence of intangible situations that are not only unquantifiable but also difficult to convey in words. This is the case of intercultural relations, where it is essential to know people’s location and movement, together with the feelings of rejection and exclusion sometimes experienced by immigrant schoolchildren. Such situations, as in the sphere of Intercultural Education, become complicated when those involved in the teaching processes do not know the language of the receiving country or they are not sufficiently fluent in it, such as in the case of kindergarten pupils.

This is a dilemma that has accompanied one of the greatest epistemological crises of the late 20th century, known as «the crisis of representation» (Rorty, 1983; Gergen, 1992; Crawford & Turton, 1992; Shotter, 2001), which questioned the foundations of objectivity made from the standpoint of Cartesian rationality based on the premise that the human mind showed the truth of reality by its representation using language. This cornerstone of objectivity was questioned by the absence of personal and contextual referents of the people making that representation.

One of the approaches for dealing with the dilemma and leaving behind this crisis situation was put forward by Anthropology, which proposed to address study situations by using narratives that provide spatial and temporal contextual elements of the action or event, and the personal context of the observer/narrator in order to be able to facilitate an understanding of the event or field of study. In this sense, the researcher is not permitted to speak on behalf of the participants and describe their behaviour and relationships using the researcher’s own cultural and scientific framework as reference – the «emic/etic» dilemma. Additionally, in Intercultural Education the underlying principle of «knowledge of the other» contributes to understanding of and affection for different Others, as when they start to form relationships they get to know each other and then start to love each other. However, to understand a personal action or social event, we need to know the intention of the person who is acting in this way as well as the interpretation or meaning given to those actions by the person on the receiving end of them (Mead, 1982; Blumer, 1982; Schutz, 1974; Berger & Luckmann, 1986). From the approach of symbolic interaction and social construction of reality, both processes are essential for acting as a group even though on the surface they may not seem to share common values. For example, for Mead (1982) both the intentions and the interpretations of human behaviour are necessary for taking group action in which each person has to interpret the actions of the rest while giving clues about the intentions behind their own conduct.

It was in the second half of the 20th century that Audio-visual Anthropology emerged as a discipline within Anthropology, concerned with studying the use of audio-visual recordings –photography, sound, video– as part of anthropological research in general and educational ethnography in particular (Ardèvol, 2006; van Leeuwen, 2008; Pink, 2007; 2009). In this context, as knowledge of the Other is one of the basic tenets of Intercultural Education, this article aims to tackle the following questions: to what extent do photo and video recordings help to understand the Other, that is, to know the intentions and interpretations of the people acting?; how, and to what extent, do audio-visual narrations provide contextual references for these actions? From a methodology point of view, what audio-photographic and film information should we collect and how should it be analysed to produce audio-visual documents that enable everyone to see the Others’ reality and truth objectively? In order to answer these questions, the following section shows some figures and describes the construction of some of the categories generated in the project funded by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation (2009-11). We will then go on to describe the contribution made by NVivo 9, a software program for handling audio-visual recordings in qualitative research, in order to describe, produce and categorise or code the intercultural relationships. Lastly, we will provide a set of conclusions drawn from the analysis.

2. The contribution of audio-visual recordings to knowledge of the other

To illustrate how we approached the issues outlined above, we present some of the elements of the two ethnographies carried out at the kindergarten and primary school (CEIP) «La Paloma» de Azuqueca de Henares (Guadalajara) and CEIP «Cervantes», a primary school in the centre of Madrid. We started work by selecting two groups of pupils at each school, one in kindergarten and the other in primary. We began our field work at the first school on 4 March 2009 and completed it on 16 June 2011. At the second school, field work started on 19 February 2009 and was completed on 21 June 2011. We went to each school one day a week. Both schools were chosen for their cultural diversity, among other reasons. Specifically, in CEIP «La Paloma», the Primary Education section had: 10 Spanish children, 1 Spanish girl of ethnic gypsy background, 6 Latin American children, 4 Rumanian children, 1 child from Burkina-Faso and 1 child from Morocco; and in Kindergarten: 18 Spanish children, 1 child from Latin America and 3 children from Nigeria. In the Primary Education section of CEIP «Cervantes»: 1 Spanish girl, 8 children from Ecuador, 4 children from Morocco, 1 girl from Paraguay, 2 from the Dominican Republic, 1 Peruvian boy, 1 Italian girl, 1 from the Philippines, 1 from Argentina and 1 from Colombia; and in Kindergarten: 3 Spanish children, 5 from Ecuador, 2 from Morocco, 3 from the Dominican Republic, 1 Peruvian boy, 2 from Bolivia, 1 Italian, 2 from the Philippines, 1 from Argentina and 1 from Venezuela. We worked with a total of 101 pupils.

Both ethnographies shared the feature of working with audio-visual narrations. There is a difference between one and the other ethnography, which is that CEIP «Cervantes» identified pupil groups through video recordings made in the playground, where each week the itinerary and activities of a particular child were filmed. This enabled us to see the companions chosen by each pupil to share their time in school with and the activities and cultural operators mediating their relationships.

During these years, the topics covered by the pupils in their audio-visual narratives were:

In CEIP «La Paloma»: What I like and don’t like about school; How I see myself and how others see me; My family and my surroundings; Reporters: Interviews with important women; Reporters: Our view of the playground; School autobiography.

In CEIP «Cervantes»: What we’re like; The neighbourhood from my school; The school from my neighbourhood; My autobiography; This is my family; Reporters in the playground; Smells, colours and sounds of Madrid.

In the reference classrooms, the stills and video camera became essential for the «native gaze» to emerge (Ardèvol, 2006; Pink, 2007) through the narratives produced by the boys and girls over the three school years. Photography and video, in addition to the classic function of recording reality that they play in educational research, formed a space where pupils created representation and therefore where meanings were discussed that enabled everyone involved –pupils and researchers– to understand who they were and what they thought about, what they liked and preferred, and what contexts they inhabited and constituted.

For example, one of the categories we dealt with was «Football: different meanings and practices», explaining that in a group of children who are fans of this sport there is much more going on than merely a particular group having an affinity for a particular physical activity. It revealed the disaffection shown by this group towards their peers, whose preference for other kinds of games and activities excludes them from playtime and complicity both in the playground and in the classroom. As we delved deeper into the data analysis, we found that football as an activity is made up of a whole array of practices and meanings which, to some extent, conditioned the interpersonal relationships of Primary Education pupils at CEIP «La Paloma». We came to understand that among group identities, there is one based on football that lends a certain stability to interactions, turning this sport into a social gathering in the playground, but also into mutual knowledge through which they shared experiences and wishes that went beyond the time spent together at break time. Of the 16 boys and 7 girls in the group, 8 boys mentioned football as a major reference point in all their narratives. As pupils made their photos and audio-visual narratives, we as participating observers began collecting evidence that football was a part of their relationships by which some sought social recognition from their peers by demonstrating their skills and physical prowess in the sport, and by possessing certain items such as footballs and football shoes in the colours of the country’s most famous clubs. They sought and obtained the group’s recognition and acceptance and this gave rise to a series of shared meanings: «he plays football well», «he’s an ace football player», and so on, in representations of themselves that were recognised by the other children. Seven boys in this group even showed their preference for an ideal type of woman, linked with the image of Sara Carbonero (a Spanish female sports journalist), Angelina Jolie or Cristiano Ronaldo’s girlfriend, all of whom were, and still are, references from a context outside school but loaded with meaning for them.

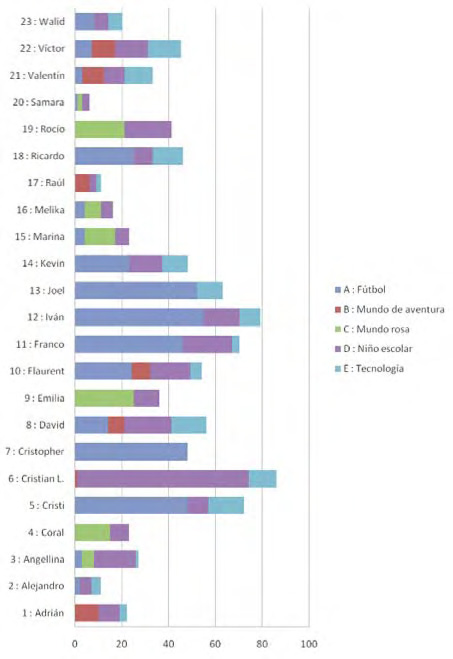

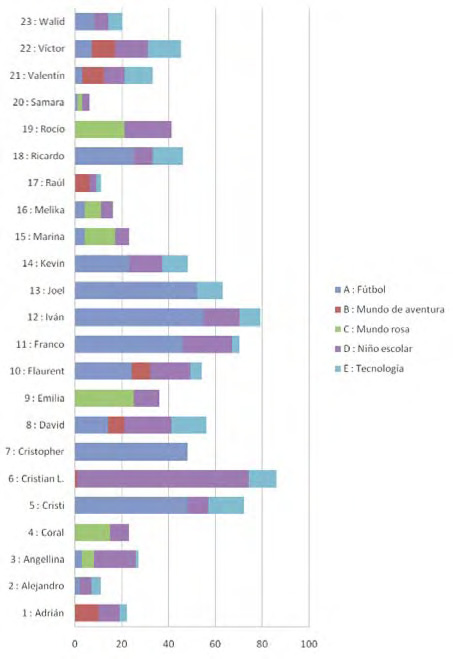

Gaining access to an understanding of this complex dynamic within the interpersonal and intercultural relationships in the sixth year primary school group would not have been possible without the pupils’ audio-visual self-narratives. Their lively, emotional and evocative photo and video records of their own referential framework made our field work into an experience of communication, social relations and learning, as understood by Ardèvol (2006), Pink, (2007) and Banks (2007). The task of thinking about what they want to say and what images they want to capture on film, plus showing and sharing their audio-visual productions in the classroom, gave rise to an exchange of meaning that enabled us to delve into topics and issues around the «school child» and the «social child», or the subject that acts with intent and within a framework of reference. In Figure 1 below, we present the relevance of each of the topics or operators around which we grouped the data for each boy and girl in «La Paloma» school. It is evident that, alongside football, the children shared a series of interests and concerns to do with the subject of «technology». This category was made up of meanings gained from their use of stills cameras and audio recording equipment during the narration process, which were, inevitably, situations that prompted pupils to share experiences and get to know each other better.

This way of proceeding with our study gave the ethnographic process two fundamental aspects, above all because it turned the photos and video recordings into valuable material for accessing «knowledge of the other». One, described by Ardèvol (2006), who argues that the relevance of the self-definitions made possible by using the camera in fieldwork, lies in that the best description of a culture is made by the native –the «emic» approach– because they are part of the cultural world that we want to understand and because these data are fundamental for addressing the researcher’s doubts, questions and interpretations. The other, already described, because audio-visual narratives produce an exchange of meanings that are neither visible nor accessible by directly observing reality, so they became essential material for complementing the observations recorded in our field notebooks2. We agree with Wolcott (2003) that if all ethnography demands that we observe the cultural aspects of behaviour to find common patterns, we need to focus our attention not only on actions but also delve into the meanings that these actions have for the social actors involved. Our direct observation of reality, together with the data and information provided by the pupils when they spoke about and discussed the audio-visual narratives, reassessed the subjectivity, interaction and exchange of meaning between the researcher, the pupils and the context in which they were acting and relating to each other (Bautista, 2009; Burn, 2010; Kushner, 2009). To paraphrase Kushner (2009: 10) «the audio-visual has the power to provoke intersubjectivity». This is a fundamental epistemological process for understanding the function and value that audio-visual narratives have in constructing true and consistent knowledge of the Other that, in turn, will allow the intercultural relationship to run smoothly and strongly. But, how did we get to categories such as «Football: different meanings and practices», immersed in the content of the audio-visual recordings?

3. Contributions of the NVivo 9 program for handling and analysing audio-visual data

By reviewing computing programs that assist with qualitative research data analysis3, we identified that the NVivo 94 application would be a valuable help in organising, handling and analysing large quantities of data recorded in photographs, audio and video. «Large-scale projects requiring several researchers sharing large quantities of audio-visual data benefit from using this technology. Researchers who decide to use CAQDAS (Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software) have a range of options for storing and analysing their data» (Pink, 2007: 139). In our case, it is evident that the value of the audio-visual recordings for our study was heightened enormously by using NVivo 9. Imagine the tedious and laborious task of handling and analysing thousands of photographs and hundreds of video recordings using conventional software. The difficulties in analysing and handling the data would hamper a thorough exploration of the content of the photos and video recordings and narratives, hindering in-depth analysis and cross referencing of the data.

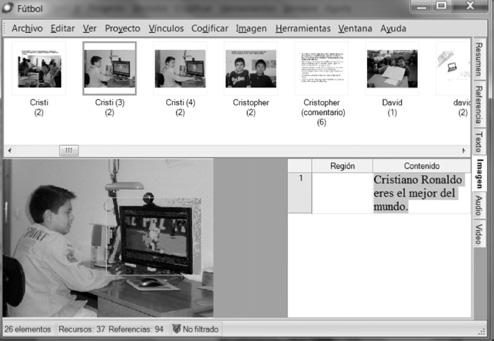

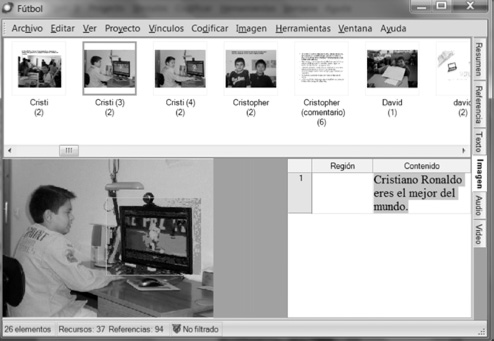

For our research this software turned out to be a tool that simplified the tasks of sorting, analysing, connecting, grouping and viewing textual and audio-visual data collected using various techniques and from different informants. The first activity this software allows us to do is connected with a basic task in ethnography, which is to define and establish initial links between the data. As a tool for carrying out this task, NVivo 9 has various functions for defining and specifying the «links» between photographic, audio, video and textual data, which in our study enabled us to relate pupils’ audio-visual recordings to researchers’ field notes and comments. To make this task easier from the outset, NVivo has a tool called «queries» which enabled us to explore data in a simple way. With «queries» we were able to ask various questions of the data in such a way that we could start to initially group information together. For example, these «queries» have enabled us to identify which of their peers each child played with during the break times recorded on video. Image 1 below is a screen shot showing the children with which Edward, a Primary Education pupil at CEIP «Cervantes», played with and the number of interactions between them in each of the sessions recorded.

NVivo also shows all the information in detail, allowing us to access every moment of each video and enabling us to watch and analyse how Edward relates to each of his 14 peers. These connections between data allow us to «find concepts that help us to make sense of what is happening in the scenes documented by the data» (Hammersley & Atkinson, 1994: 227). As commented above, from the first audio-visual narratives, we discovered how football emerged as a primary concept that made sense of various data collected using different techniques. This meant we could make groupings that allowed us to gradually understand how intercultural relationships were being established and what they consisted of. As in the case of football, these groupings enabled us to validate that behind a love of the sport there was an array of highly diverse meanings and practices that made sense of the relationships between the children and showed the true nature of the boys and girls in the classrooms. NVivo enabled to get a level of intersubjective recording of detailed descriptions and comparative explanation on how our pupils were relating to each other and what cultural objects and practices were mediating in these interactions. As Geertz said, (2001: 37-38) «the task consists in discovering the conceptual structures that inform our subjects’ acts, what is «said» in social discourse, and in building a system of analysis in terms of what is generic about those structures, what belongs to them because of what they are, is highlighted and remains against other determining factors of human behaviour. In ethnography, the function of theory is to supply a vocabulary that can express what symbolic action has to say about itself, that is, on the role of culture in human life».

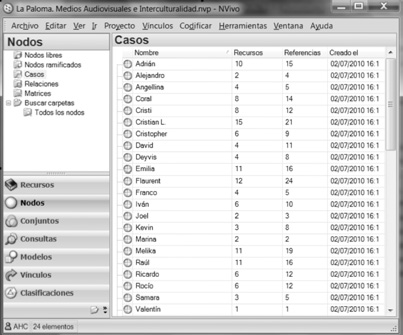

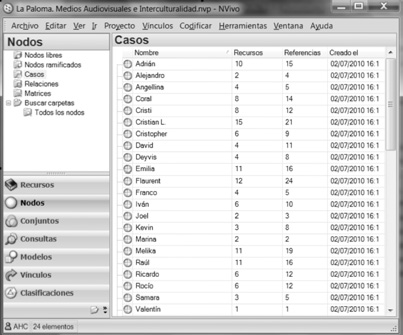

This complex process within ethnography needs a tool that is sufficiently flexible and powerful to relate different kinds of recordings (textual, digital, audio-visual, image, sound, etc.). «Nodes» such as the ones used by NVivo enabled us to do this complex task. As shown in Image 2, in addition to an accessible environment for working with the data, this tool enables complex groups of meanings to be set up as they are built from different kinds of recordings, at different times and by different individuals.

NVivo 9 also provides a workspace that is not available in any other CAQDAS, as Lewins & Silver (2007) acknowledge, and we consider it to be essential for any ethnographic research project and for our study in particular. The data grouping environment called «cases» helped us to focus on the study of each boy and girl and was where we stored various kinds of data to know more about them. Image 3 shows the twenty-five cases of the pupils in 6th year of Primary Education at CEIP «La Paloma», holding a large number of audio-visual recordings taken by the children together with recordings obtained by the three researchers who provided relevant information about who they were and what their relationships were.

This way, we captured the view of several participants and what was anecdotal and meaningful in the actions and discourse of the social agents; this enabled us to know what they were feeling and thinking in order to understand how they were acting. In these groups of «cases» we collected each pupil’s discourse, together with the views of their classmates and any relevant events recorded by the researchers involving each of the subjects. We therefore built second order data because we coincided with Geertz (2001: 23) in that «what we call our data are really interpretations of interpretations of other people on what they and their fellow countrymen think and feel». Returning to Image 2, it can be seen how each «case» groups together different kinds of recordings, giving us easy access –as with the «nodes»– to audio-visual and textual data, and verify for each child –as in the case of the example under discussion– what cultural operators were mediating in their relationships and what practices were associated, as well as the meanings they held for each pupil.

With the same work options provided by the grouping of «nodes», in «cases» we were able to access each pupil’s many audio-visual representations, as well as the discourses and meanings extracted during the process of eliciting the image referred to in the above paragraph. The potential of the «cases» lies in providing a space in which to describe the story of each social agent, their values, meanings and norms that govern their social life and that allows them to be embodied. The «cases» allowed us to look at individuality, the detail of the culture as it was experienced by each pupil, enabling us to make sense of reality from an intersubjective discourse and get under each boy and girl’s skin to understand their point of view and their feelings in their different contexts: school and social.

4. Conclusions

We understand that knowledge of the Other is one of the core aspects of Intercultural Education and of the solution to the «etic-emic» dilemma faced by ethnographic studies. We approached this knowledge by specifying and sharing the intentions and interpretations of human actions in situations of collaborative work, such as the audio-visual narration of stories that are relevant to the people in them. In this context, we can provide some answers to the three questions posed in the introduction:

To what extent can photo and video recordings help to understand the Other, that is, to know the intentions and interpretations of the people acting? In the work carried out during the school years 2008/09, 2009/10 and 2010/11, both photographic and video images were the basic systems used for representing the collaborative relationships, as they enabled us to show not only the perception of reality through the eyes of the people taking part, but also to convey attitudes, feelings, events and intangible relationships that are hard to communicate using words; in the case of some pupils, the fascination with fame or the power of some football players. In this sense, we consider that the use of photographic and film language was valuable in capturing the intentional behaviour of some of the participants and to show the interpretations of those on the receiving end of these actions.

How and to what extent do audio-visual narrations provide contextual references of these behaviours? We found that the photographic and film language used in the stories or in the autobiographical accounts favoured an understanding of pupils’ personal or socio-cultural reality, as it gave continuity to the situations they experienced through the spatial and temporal aspects recorded. This essence of the narration has enabled us to contextualise socio-cultural events, indicating not only the physical characteristics of the people and places involved, but also to present them in the economic or political framework in which they live, that is, in a specific place and at a particular moment in time. That contextualisation helps to make sense of someone’s life – the beliefs, thoughts, emotions, intentions and so on that explain their actions – and to facilitate an understanding of the interpretations of that life made by the people they interact with. They are representations that facilitate knowledge of the Other, an essential aspect of Intercultural Education.

What audio-photographic and film information should we collect and how should it be analysed to produce audio-visual documents that enable everyone to objectively see the Others’ reality and truth? We have said that audio-visual recording is a good tool for collecting information on human phenomena. To understand how that recording should be made, we should add that social situations are historically and culturally organised, that these scenarios of activity are made up of material and symbolic elements with meanings that make sense of behaviours and relationships that occur within them. Therefore, to understand the action of humans in those scenarios –their intentions and interpretations– their continuity in space and time should be recorded, as their meanings are in the temporal order and in the succession of places in which these practices occur; a «continuum» that is inherent in film language. Now, as well as addressing the continuity of the film shots of the cultural situations under scrutiny, we should add the importance of the camera’s point of view, the requirement to give the recorder to the Others so that they can convey their intentions, concerns and interpretations; this will enable us to confront the «etic-emic» dilemma and, for example, find out the reason for their affections or the attraction that a high proportion of pupils taking part feel for audio-visual technology. Lastly, as we reflect on intercultural relationships, we should state that audio-visual data are valid for representing their essential elements and help to produce interesting knowledge when they are handled by computer programs such as NVivo 9, that facilitate the visualisation, ordering, relation, grouping and analysis of different kinds of recordings – text, audio, photography, video, etc.

Notes

1 It may be worth pointing out that these processes of elicitation entail a projective observation as contemplated by audio-visual ethnography, which consists in putting social agents in front of their own still shots or films in order to obtain more and better data. This became a technique that enabled comments to be recovered and events remembered in order to delve deeper into them, as well as generating discussion, views and exchanging different points of view (Ardèvol, 2006). During three school years, pupils made narratives about nine topics, so we worked on one topic per quarter.

2 We have already pointed out the elicitation processes produced by pupils’ audio-visual narratives and the resulting projective observation. We can now point out that this type of observation produced a textuality from the story, or narration of what was being represented, enabling us to make a dialogic observation of the reality within a structure of exchange of knowledge and interpretations alongside the pupils. The photo and video records meant that it was possible to make observations that complemented our direct perception; this enabled us to complete, explain, discard or delve deeper into the information and descriptions in our field notebooks.

3 This group of software packages is known as CAQDAS: Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software.

4 There are various types of software available to help analyse qualitative data and they are described in work by Weitzman & Miles (1995), Fielding & Lee (1998) and Lewins & Silver (2007). We used «code-based theory construction software» for its complexity and its flexibility in handling and analysing data. The website for the CAQDAS Project being carried out by leading intellectuals for data study is also a useful resource.

References

Ardèvol, E. (2006). La búsqueda de una mirada. Antropología vi sual y cine etnográfico. Barcelona: Editorial UOC.

Banks, M. (2007). Using Visual Data in Qualitative Research. Lon don: Sage.

Bautista, A. (2009). Relaciones interculturales mediadas por narraciones audiovisuales en educación. Comunicar, 33, 169-179. (DOI: 10.3916/c33-2009-03-006).

Berger, P. & Luckmann, T. (1986). La construcción social de la realidad. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu-Murguia.

Blumer, H. (1982). El interaccionismo simbólico. Perspectiva y método. Barcelona: Hora.

Burn, A. (2010). Emociones en la oscuridad: Imágenes y alfabetización mediática en jóvenes. Comunicar, 35, 33-42. (DOI: 10.39 16/ C35-2010-02-03).

Crawford, P.I. & Turton, D. (1992). Film as Ethnography. Man chester: Manchester University Press.

Fielding, N.G. & Lee, R.M. (1998). Computer Analysis and Qua litative Research. London: Sage.

Geertz, C. (2001). La interpretación de las culturas. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Gergen, K.J. (1992). El yo saturado: dilemas de identidad en el mun do contemporáneo. Barcelona: Paidós.

Hammersley, M. & Atkinson, P. (1994). Etnografía. Métodos de investigación. Barcelona: Paidós.

Kushner, S. (2009). Recuperar lo personal. In J.I. Rivas & D. He rre ra (Eds.), Voz y educación (pp. 9-16). Barcelona: Octaedro.

Lewins, A. & Silver, C. (2007). Using Software in Qualitative Research: A Step-by-step Guide. London: Sage.

Mead, G.H. (1982). Espíritu, persona y sociedad. Barcelona: Paidós.

Pink, S. (2007). Doing Visual Ethnography. London: Sage.

Pink, S. (2009). Visual Interventions. Applied Visual Anthropo logy. London: Sage.

Rorty, R. (1983). La filosofía y el espejo de la naturaleza. Madrid: Cátedra.

Schutz, A. (1974). El problema de la realidad social. Buenos Ai res: Amorrortu.

Shotter, J. (2001). Realidades conversacionales. La construcción de la vida a través del lenguaje. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

Van Leeuwen, T. & Jewitt, C. (2008). Handbook of Visual Analysis. London: Sage.

Web de QSR International: (www.qsrinternational.com) (29-05-2011).

Web del Proyecto CAQDAS. (http://caqdas.soc.surrey.ac.uk) (20-05-2011).

Weitzeman, E.A. & Miles, M.B. (1995). Computer Programs for Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Wolcott, H.F. (2003). Sobre la intención etnográfica. In H.M. Velasco Maillo, F.J. García Castaño & M. Díaz de Rada (Coords.), Lecturas de antropología para educadores. El ámbito de la antropología de la educación y de la etnografía escolar (pp. 127-144). Madrid: Trotta.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Este artículo analiza las posibilidades de los registros audiovisuales como datos en la investigación sobre relaciones interculturales, o aquellas que van dirigidas al conocimiento del otro. Pretende contribuir a la teorización sobre el valor de las narraciones fotográficas y videográficas en la representación y análisis de realidades de la enseñanza que son difíciles de captar y cuantificar. Concretamente, estudiamos si el registro audiovisual es una buena herramienta para recoger y analizar información situada sobre las intenciones e interpretaciones contenidas en las relaciones humanas. Después de presentar algunos dilemas epistemológicos y metodológicos, como la denominada crisis de la representación en ciencias sociales o el conflicto «etic-emic», y de plantear algunas soluciones dadas desde la antropología audiovisual, analizamos la naturaleza de algunas situaciones de educación intercultural recogidas en los dos colegios –etnografías– que soportan el estudio finalizado en 2011 y financiado por el Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación de España, sobre el uso de narraciones audiovisuales como sustrato de las relaciones entre el alumnado diverso culturalmente de educación infantil y primaria. A modo de ejemplo, describimos cómo hemos llegado a algunas de las categorías o constructos que llevan a entender el universo de significados que dan sentido a la vez que condicionan y configuran las relaciones interculturales de esos centros. Finalmente, describimos las aportaciones de algunas herramientas del software NVivo 9 en el análisis del contenido de registros y narraciones foto-videográficas.

1. Introducción

En la investigación que se ha venido realizando desde los años ochenta sobre los procesos de enseñanza ha emergido el dilema que abordamos en este artículo: la existencia de situaciones intangibles que, además de no ser cuantificables, son difíciles de comunicar con palabras. Tal es el caso de las relaciones interculturales donde la ubicación y movimiento de las personas son imprescindibles de conocer, así como las sensaciones de rechazo y exclusión sentidas a veces por el alumnado inmigrante. Son acontecimientos que, como sucede en el ámbito de la educación intercultural, se complican cuando los participantes en los procesos de enseñanza no conocen el lenguaje del país de acogida o no lo han adquirido suficientemente, en el caso del alumnado de la etapa infantil.

Ha sido un dilema que ha acompañado a uno de los conflictos epistemológicos más relevantes ocurridos a finales del siglo pasado, conocido como «crisis de representación» (Rorty, 1983; Gergen, 1992; Crawford & Turton, 1992; Shotter, 2001), que cuestionaba los fundamentos de objetividad que se hacían desde la racionalidad cartesiana basada en el presupuesto de que la mente humana mostraba lo verdadero de una realidad mediante la representación que hacía de ella utilizando el lenguaje. Tal fundamento de objetividad se puso en tela de juicio por la ausencia de los referentes personales y contextuales de quienes hacen esa representación.

Uno de los planteamientos para afrontar el anterior dilema y salir de esa situación de crisis se ha realizado desde la Antropología, proponiendo una aproximación a las situaciones de estudio mediante narraciones que proporcionen elementos contextuales espacio-temporales de la acción o acontecimiento,… y personales del observador/narrador con el fin de facilitar la comprensión de ese evento o ámbito de estudio. En este sentido, se desautoriza al investigador para hablar en nombre de los participantes y comunicar sus comportamientos y relaciones utilizando los propios marcos culturales y científicos como referencia –dilema «emic/etic»–. Además, en educación intercultural subyace el principio del «conocimiento del otro» que lleva a la comprensión y generación de afectos sobre y con los otros distintos, pues cuando se relacionan se conocen y, entonces, empiezan a quererse. Ahora bien, para entender una acción personal, o un acontecimiento social, es necesario conocer la intencionalidad de quienes actúan así como la interpretación o significado que otorgan a esas acciones quienes reciben su efecto (Mead, 1982; Blumer, 1982; Schutz, 1974; Berger & Luckmann, 1986). Desde los planteamientos del interaccionismo simbólico y de la construcción social de la realidad, ambos procesos son esenciales para actuar conjuntamente aunque a priori no compartan valores comunes. Por ejemplo, para Mead (1982), tanto las intenciones como las interpretaciones de un comportamiento humano son necesarias para emprender acciones grupales, donde cada uno debe de interpretar los actos del resto a la vez que dar indicaciones sobre las intenciones de sus conductas.

Fue en la segunda mitad del siglo pasado, cuando emergió la Antropología Audiovisual como disciplina dentro de la Antropología preocupada por estudiar el uso de los registros audiovisuales –fotografía, sonido, vídeo– en la investigación antropológica en general y en la etnografía educativa en particular (Ardèvol, 2006; Van Leeuwen, 2008; Pink, 2007; 2009). En este contexto, al ser el conocimiento del otro uno de los fundamentos de la educación intercultural, en este artículo pretendemos abordar estos interrogantes: ¿en qué medida los registros foto-videográficos ayudan a comprender al otro, es decir, a conocer las intenciones e interpretaciones de quienes actúan?, ¿cómo, y en qué grado, las narraciones audiovisuales proporcionan referentes contextuales de esas acciones? Desde un punto de vista metodológico, ¿qué información audio-fotográfica y cinematográfica debemos recoger y cómo ha de ser analizada para producir documentos audiovisuales que aproximen a todos con objetividad a la realidad y verdad de los otros? Con el fin de dar respuesta a estas cuestiones, expondremos algunos datos y la ejemplificación de la construcción de alguna de las categorías generadas en el proyecto subvencionado por el Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (2009-11). Después, describiremos las aportaciones de NVivo 9, software orientado al tratamiento de los registros audiovisuales en la investigación cualitativa, para describir, elaborar y categorizar o codificar las relaciones interculturales. Finalmente, aportaremos algunas de las conclusiones del anterior análisis.

2. Aportaciones de los registros audiovisuales al conocimiento del otro

Para entender cómo abordamos los interrogantes anteriores, vamos a presentar, a modo de ilustración, algunos de los elementos de las dos etnografías que desarrollamos: la correspondiente al Centro de Educación Infantil y Primaria (CEIP) «La Paloma» de Azuqueca de Henares (Guadalajara) y el CEIP «Cervantes», una escuela ubicada en el centro de Madrid. Iniciamos el trabajo seleccionando dos grupos de alumnos en cada centro, uno de educación infantil y otro de educación primaria. Comenzamos el trabajo de campo en el primer colegio el 4 de marzo del 2009 y abandonamos el campo el 16 de junio del 2011. En el segundo lo iniciamos el 19 de febrero de 2009 y lo abandonamos el 21 de junio de 2011. Asistimos a cada colegio un día a la semana. Ambos colegios fueron elegidos, entre otras razones, por la diversidad cultural que acogen. Concretamente, en el CEIP «La Paloma», en Educación Primaria hubo: diez niños españoles, una niña española de etnia gitana, seis niños latinoamericanos, cuatro niños rumanos, uno de Burkina-faso y un niño de Marruecos; y en Educación infantil: 18 niños españoles, dos latinoamericanos y tres nigerianos. En el CEIP «Cervantes», en Educación Primaria: una niña española, ocho ecuatorianos, cuatro niños marroquíes, una niña paraguaya, dos dominicanos, una venezolana, un peruano, dos bolivianos, una italiana, una filipina, una argentina y un colombiano; y en Educación Infantil: tres españolas, cinco ecuatorianos, dos marroquíes, tres dominicanos, un peruano, dos bolivianos, un italiano, dos filipinos, una argentina y un venezolano. Trabajamos con un total de 101 alumnos.

Las dos etnografías tienen en común la forma de trabajar con las narraciones audiovisuales. Existe una diferencia entre una y otra, y es que en el CEIP «Cervantes» se identificaron los agrupamientos del alumnado a través del registro videográfico de los recreos, donde cada semana se grabó con la cámara el itinerario y las actividades que realizó un alumno determinado. De esta forma, pudimos conocer a los compañeros que eligió cada alumno para compartir este tiempo escolar y las actividades y operadores culturales que mediaron en sus relaciones.

Durante estos años, las temáticas trabajadas por el alumnado en sus narraciones audiovisuales fueron:

En el CEIP «La Paloma»: Qué me gusta y no me gusta del colegio; cómo me veo, cómo me ven; mi familia y mi entorno; reporteros: entrevistas a mujeres importantes; reporteros: nuestra visión del recreo; autobiografía escolar…

En el CEIP «Cervantes»: así somos; el barrio desde mi colegio; el colegio desde mi barrio; mi autobiografía; esta es mi familia; historias de mi barrio; reporteros en el recreo; olores, colores y sonidos de Madrid…

En las aulas de referencia, la cámara fotográfica y de vídeo se han revelado imprescindibles para que emerja la «mirada nativa» (Ardèvol, 2006; Pink, 2007) a través de las narraciones que los niños y niñas elaboraron en los tres cursos escolares. La fotografía y el vídeo, además de la función ya clásica que cumplen en la investigación educativa para registrar la realidad, dieron lugar a un espacio donde los estudiantes crearon representaciones y, por tanto, donde se discutieron significados que permitieron a todos los participantes –alumnado e investigadores– comprender quiénes eran y en qué pensaban, cuáles eran sus gustos y preferencias, y qué contextos habitaban y les constituían.

Así, por ejemplo, llegamos a una de las categorías «El fútbol: significados y prácticas diversas», que explica como la afición a este deporte de un conjunto de niños de educación primaria encierra algo más que una afinidad por una actividad física para un grupo determinado, y la desafección correspondiente que ese equipo muestra por otros compañeros, cuyos gustos por otro tipo de juegos y actividades les excluye de sus ratos de juego y complicidades en el recreo y en el aula. A medida que fuimos profundizando en el análisis de los datos, el fútbol, como actividad, conformó un universo de prácticas y significados que, en alguna medida, condicionó las relaciones interpersonales del alumnado de Educación Primaria del CEIP «La Paloma». Comprendimos que entre las identidades de grupo, hay una en torno al fútbol que otorgó cierta estabilidad en las interacciones, convirtiendo este deporte en un encuentro social en el recreo, pero también en conocimiento mutuo a través del cual compartían experiencias y deseos más allá del tiempo de patio. De los 16 niños y 7 niñas que conformaban el grupo, 8 niños hicieron alusión al fútbol como un referente importante en todas sus narraciones. Según el alumnado fue realizando sus fotos y narraciones audiovisuales, nuestra observación participante fue evidenciando que el fútbol era un contenido de relación mediante el cual algunos de ellos buscaban el reconocimiento social de sus compañeros por las destrezas y condiciones físicas que asociaban a este deporte, y por la posesión de determinados objetos como balones o zapatillas de los clubs deportivos más conocidos en nuestro país. Buscaban y obtenían un reconocimiento y aceptación del grupo, y de este modo se movilizaron unos significados que compartieron entre sí: «juega bien al fútbol», «es un crack jugando al fútbol»…. representaciones de sí mismos que fueron reconocidas por los otros. Incluso, siete niños de este grupo mostraron un gusto por un ideal de mujer, asociado a la imagen de Sara Carbonero, Angelina Jolie, o la novia de Cristiano Ronaldo, que eran y son referentes de un contexto ajeno a la escuela pero cargados de significados para ellos.

El acceso a la comprensión de esta dinámica compleja, contenido de la relación interpersonal e intercultural en el grupo de sexto de primaria, no hubiera sido posible sin las auto-narraciones audiovisuales del alumnado; registros de datos foto-videográficos vivos, emotivos y evocadores de cuáles eran sus referentes, que convirtieron el trabajo de campo en una experiencia de comunicación, relación social y aprendizaje, tal y como lo entiende Ardèvol (2006), Pink, (2007) y Banks (2007). La tarea de pensar qué quieren contar y qué imágenes de la realidad van a captar, junto con la exhibición y puesta en común de las producciones audiovisuales en el aula, generaron una práctica de intercambio de significados que nos permitió adentrarnos en temas y cuestiones que pusieron en relación al «niño escolar» con el «niño social», o sujeto que actúa con una intención y desde un marco referencial. A continuación, en el gráfico 1, presentamos la relevancia de cada uno de los temas u operadores en torno a los cuales agrupamos los datos para cada niño y niña del colegio «La Paloma». Resulta evidente cómo, además del fútbol, compartieron unos intereses y preocupaciones en torno a la «tecnología». Una categoría conformada por significados nutridos del uso que hicieron de las cámaras de fotos y grabadoras de audio en los procesos de narración que, ineludiblemente, fueron situaciones que llevaron al alumnado a compartir experiencias y, consecuentemente, a un mayor conocimiento mutuo.

Esta forma de proceder en nuestro estudio otorgó dos dimensiones fundamentales al proceso etnográfico, sobre todo porque convirtió los registros foto-videográficos en un material valioso para acceder al «conocimiento del otro». Una, señalada por Ardèvol (2006), quien plantea que la relevancia de las auto-definiciones que posibilita la introducción de la cámara en el trabajo de campo reside en que la mejor descripción de una cultura la realiza el nativo –aproximación «emic–, porque se mueve dentro del universo cultual que queremos comprender, y porque estos datos son básicos para abordar las dudas, cuestiones e interpretaciones del investigador. Y otra, ya señalada, porque las narraciones audiovisuales generan un intercambio de significados no visibles ni accesibles mediante la observación directa de la realidad, de modo que se convirtieron en un material imprescindible para complementar las observaciones registradas en nuestros diarios de campo2. Estamos de acuerdo con Wolcott (2003) en que si toda etnografía nos exige observar el comportamiento en sus dimensiones culturales para descubrir pautas comunes, necesitamos no solo centrar la atención en las acciones, hay que profundizar en los significados que esas acciones tienen para los actores sociales. Nuestra observación directa de la realidad, junto con los datos e informaciones que nos ofrecía el alumnado cuando hablaba y discutía sobre las narraciones audiovisuales, revalorizó la subjetividad, la interacción e intercambio de significados entre el investigador, los estudiantes y el contexto en el que éstos actuaban y se relacionaban (Bautista, 2009; Burn, 2010; Kushner, 2009). Parafraseando a Kushner (2009: 10) «lo audiovisual tiene el poder de provocar intersubjetividad». Proceso epistemológico fundamental para comprender la función y el valor que las narraciones audiovisuales tienen en la construcción de un conocimiento del otro veraz y consistente que, a su vez, dará fluidez y fuerza a la relación intercultural. Pero, ¿cómo hemos llegado a categorías como «El fútbol: significados y prácticas diversas», inmersa en los contenidos soportados en los registros audiovisuales?

3. Aportaciones del programa NVivo 9 para el tratamiento y análisis de datos audiovisuales

Revisando los programas informáticos que ayudan al análisis de datos en investigación cualitativa3, hemos identificado que la aplicación NVivo 94 supone una valiosa ayuda para la organización, tratamiento y análisis de grandes cantidades de datos registrados mediante fotografía, audio y vídeo. «Los proyectos de gran envergadura que requieren varios investigadores quienes comparten grandes cantidades de datos audiovisuales se ven beneficiados en el uso de estas tecnologías. Los investigadores que deciden utilizar los CAQDAS, disponen de posibilidades para almacenar y analizar sus datos» (Pink, 2007: 139). En nuestro caso, es evidente que el valor que tuvieron los registros audiovisuales en nuestro estudio se vio enormemente potenciado por el uso de NVivo 9. Piénsese la tediosa e ingente labor que supondría manejar y analizar miles de fotografías y cientos de registros de vídeo en software convencionales. Las dificultades para analizar y tratar dichos datos se traducirían en una limitación clara para explorar todo el contenido de los registros y narraciones foto-videográficas, obstaculizando un análisis en profundidad y transversal de los datos.

Este software se ha revelado en nuestra investigación como una herramienta que facilita tareas de ordenación, análisis, conexión, agrupamiento y visualización de datos textuales y audiovisuales recogidos a través de distintas técnicas y por medio de diferentes informantes. La primera actividad que permite este software tiene que ver con una tarea básica en la etnografía que es definir y establecer las primeras relaciones entre los datos. Como herramienta facilitadora de esta tarea, NVivo 9 ofrece diferentes funciones para definir y explicitar los «vínculos» entre datos de fotografía, audio, vídeo y texto, que en nuestro estudio nos sirvió para poner en relación las representaciones audiovisuales de los alumnos con las notas de diario y reflexiones de los investigadores. Para facilitar esta tarea en un primer momento, NVivo dispone de una herramienta llamada «consultas» que nos permite explorar los datos de una forma sencilla. Con las «consultas» podemos realizar diferentes preguntas a los datos de tal forma que comenzaremos a realizar unos primeros agrupamientos de información. Por ejemplo, estas «consultas» nos han permitido identificar con qué compañeros se relacionaban cada uno de los niños en los recreos que hemos registrado en vídeo. A continuación, en la imagen 1, podemos ver una captura de pantalla donde se muestran los compañeros con quienes Edward, alumno de Educación Primaria del CEIP «Cervantes», se relacionó y el número de interacciones en cada una de las sesiones registradas.

Pero además, NVivo recoge toda la información en detalle, permitiéndonos acceder a todos los momentos de cada uno de esos vídeos y, de esta forma, contemplar y analizar cómo se relacionó Edward con cada uno de sus 14 compañeros. Estas conexiones entre datos, nos permiten «encontrar algunos conceptos que nos ayuden a dar sentido a lo que tiene lugar según las escenas documentadas por los datos» (Hammersley & Atkinson, 1994: 227). Como ya se ha comentado, a raíz de las primeras narraciones audiovisuales, descubrimos cómo la afición al fútbol emergió como un primer concepto que dio sentido a distintos datos recogidos mediante diferentes técnicas. De esta forma, fuimos realizando agrupamientos que hicieron posible comprender progresivamente cómo se establecían las relaciones interculturales y su contenido. Y, como en el caso del balompié, estos agrupamientos nos permitieron ir ratificando que tras la afición a ese deporte se definió un universo de significados y prácticas muy diversas que dieron sentido a las relaciones entre el alumnado, y que mostraron quiénes eran los niños y niñas que habitaban las aulas. NVivo nos permitió un nivel de registro intersubjetivo de descripción detallada y explicación contrastada sobre cómo nuestros alumnos se relacionaban y qué objetos y prácticas culturales mediaban esas interacciones. Como reconoce Geertz (2001: 37-38) «la tarea consiste en descubrir las estructuras conceptuales que informan los actos de nuestros sujetos, lo «dicho» del discurso social, y en construir un sistema de análisis en cuyos términos aquello que es genérico de esas estructuras, aquello que pertenece a ellas porque son lo que son, se destaque y permanezca frente a los otros factores determinantes de la conducta humana. En etnografía, la función de la teoría es suministrar un vocabulario en el cual pueda expresarse lo que la acción simbólica tiene que decir sobre sí misma, es decir, sobre el papel de la cultura en la vida humana».

Para este proceso complejo propio de la etnografía se requiere de una herramienta lo suficientemente flexible y potente que ponga en relación registros de diferente naturaleza (textual, digital, audiovisual, imagen, sonido…). Fue a través de los «nodos» cómo NVivo nos permitió hacer esta tarea compleja. Según se evidencia en la imagen 2, además de un entorno accesible para trabajar con los datos, esta herramienta permite crear grupos de significados complejos porque están construidos por registros de distinta naturaleza, en diferentes momentos y por diferentes agentes.

Además, NVivo 9 pone a nuestra disposición un espacio de trabajo que no está disponible en ningún otro CAQDAS, como reconocen Lewins y Silver (2007) y que nosotros consideramos imprescindible para toda investigación etnográfica, y para nuestro estudio en particular. El espacio de agrupamiento de datos llamado «casos», ayuda a centrarnos en el estudio de cada niño y niña donde recogemos los datos de distinta naturaleza para conocerlos. En la imagen 3 vemos los veinticinco casos del alumnado de sexto de Primaria del CEIP «La Paloma», donde se recoge gran cantidad de registros audiovisuales tomados por los niños junto con los registros obtenidos por los tres investigadores que aportamos información relevante sobre quiénes eran y sus relaciones.

De esta forma, captamos la mirada de los diferentes participantes, lo anecdótico y significativo de las acciones y discursos de los agentes sociales que facilita conocer qué sienten y piensan para comprender cómo actúan. En estos agrupamientos de «casos», fuimos recogiendo los discursos de cada alumno, así como la opinión del resto de sus compañeros y de los acontecimientos relevantes captados por los investigadores que involucran a cada sujeto. Por lo tanto, construimos datos de segundo orden porque coincidimos con Geertz (2001: 23) en que «lo que nosotros llamamos nuestros datos son realmente interpretaciones de interpretaciones de otras personas sobre lo que ellas y sus compatriotas piensan y sienten». Volviendo a la imagen 2, puede observarse cómo cada «caso» agrupan diferentes tipos de registros, permitiendo acceder –al igual que en los «nodos»– de una forma sencilla a los datos audiovisuales y textuales y, comprobar para cada niño –como el caso del ejemplo que nos ocupa– qué operadores culturales mediaban en sus relaciones y qué prácticas llevaban asociados, así como los significados que todo ello tenía para cada alumno.

Con las mismas posibilidades de trabajo que disponen los agrupamientos de «nodos», en los «casos» podemos acceder a las múltiples representaciones audiovisuales de cada alumno, así como los discursos y significados extraídos en el proceso de elicitación de la imagen al que nos hemos referido en el apartado anterior. La potencialidad de los «casos» reside en proporcionar un espacio donde describir la historia de cada agente social, sus valores, significados y normas por las que se rigen su vida social y que permite encarnarles. Los «casos» nos han permitido atender a la individualidad, al detalle de la cultura tal y como la experimentaba cada estudiante, permitiéndonos dar sentido a la realidad desde un discurso intersubjetivo y poniéndonos en la piel de cada niño para comprender su punto de vista y su sentir en sus diferentes contextos: escolar y social.

4. Conclusiones

Entendemos que el conocimiento del otro es uno de los elementos nucleares de la educación intercultural y de la solución al dilema «etic-emic» planteado en los estudios etnográficos. Abordamos tal conocimiento a través de la explicitación y puesta en común de las intenciones e interpretaciones de las actuaciones humanas en situaciones de trabajo colaborativo, tales como la narración audiovisual de historias relevantes para sus protagonistas. En este contexto, pretendemos aportar algunas respuestas a las tres preguntas que presentamos en la introducción:

¿En qué medida los registros foto-videográficos ayudan a comprender al otro, es decir, a conocer las intenciones e interpretaciones de quienes actúan? En el trabajo realizado durante los cursos 2008/09, 2009/10 y 2010/11, tanto la imagen fotográfica como la de vídeo fueron básicas como sistemas de representación de las relaciones colaborativas pues permitieron mostrar no solo la percepción de la realidad a través de los ojos de los participantes, sino también comunicar actitudes, sensaciones, acontecimientos, relaciones intangibles difíciles de comunicar con palabras; en el caso de algunos alumnos, la fascinación por la fama o el poder de ciertos jugadores de fútbol. En este sentido, consideramos que el uso de los lenguajes de la fotografía y del cine fue valioso para recoger la intencionalidad del comportamiento de algún participante y para manifestar las interpretaciones de quienes reciben los efectos de dichas acciones.

¿Cómo y en qué grado, las narraciones audiovisuales proporcionan referentes contextuales de esos comportamientos? Hemos experimentado que el lenguaje foto-cinematográfico usado en los relatos o en las narraciones autobiográficas favoreció la comprensión de la realidad personal o sociocultural del alumnado pues dio continuidad a las situaciones que vivieron mediante los elementos espaciales y temporales que registraron. Esta esencia de la narración nos ha permitido contextualizar eventos socioculturales, indicando no solo las características físicas de los personajes y ambientes, sino presentándolos en el marco económico, político… en el que viven, es decir, en un lugar concreto y en un momento histórico determinado. Esa contextualización ayuda a dar sentido a la vida de un personaje –creencias, pensamientos, emociones, intenciones… que explican su actuación–, y a facilitar la comprensión de las interpretaciones de esa vida que hacen quienes se relacionan con él. Son representaciones que facilitan el conocimiento del otro, o dimensión esencial de la educación intercultural.

¿Qué información audio-fotográfica y cinematográfica debemos recoger y cómo ha de ser analizada para producir documentos audiovisuales que aproximen a todos con objetividad a la realidad y verdad de los otros? Hemos manifestado que el registro audiovisual es un buen instrumento para recoger información situada sobre los fenómenos humanos. Para entender cómo ha de hacerse esa grabación, debemos añadir que las situaciones sociales están histórica y culturalmente organizadas, que estos escenarios de actividad están conformados por elementos materiales y simbólicos con significados que dan sentido a los comportamientos y relaciones acontecidas en su seno. Por lo tanto, para entender la acción de los humanos en esos escenarios –sus intenciones e interpretaciones– hay que registrar su continuidad en el espacio y en el tiempo, pues sus significados están en el orden temporal y en la sucesión de lugares en los que se desarrollan dichas prácticas; «continuun» que es consustancial en el lenguaje del cine. Ahora bien, además de plantear la continuidad de las tomas cinematográficas de las situaciones culturales que son objeto de estudio, hemos de añadir la importancia del punto de vista de la cámara, la exigencia de dar la grabadora a los otros para que comuniquen sus intenciones, preocupaciones e interpretaciones y, de esta forma, podamos afrontar el dilema «etic-emic» y, por ejemplo, llegar a saber el porqué de sus afectos o de la atracción que buena parte del alumnado participante siente por la «tecnología audiovisual». Finalmente, en el momento de la reflexión sobre las relaciones interculturales, hemos de manifestar que los datos audiovisuales son válidos para representar elementos esenciales de las mismas y ayudan a elaborar conocimiento interesante cuando son tratados con programas de ordenador como NVivo 9, que facilitan la visualización, ordenación, relación, agrupación y análisis de registros de diferente naturaleza: texto, audio, fotografía, vídeo…

Notas

1 No está de más señalar que estos procesos de elicitación implican una observación proyectiva tal y cómo es contemplada desde la etnografía audiovisual, que consiste en poner a los agentes sociales ante sus propios fotogramas o films para obtener más y mejores datos. Se convierte en una técnica que permite rescatar comentarios y recordar acontecimientos para profundizar en ellos, así como generar discusiones, opiniones y hacer fluir diferentes puntos de vista (Ardèvol, 2006). Durante tres años escolares el alumnado ha realizado narraciones en torno a nueve temas, de modo que hemos trabajado un tema por trimestre.

2 Ya hemos señalado los procesos de elicitación a los que dan lugar las narraciones audiovisuales del alumnado, y la consiguiente observación proyectiva. Ahora señalar que este tipo de observación hizo del relato, o narración de lo representado, una textualidad que nos permitió una observación dialógica de la realidad bajo una estructura de intercambio de conocimientos e interpretaciones junto al alumnado. Los registros foto-videográficos posibilitaron una observación, por tanto, complementaria a la percepción directa que hicimos; pudiendo, de esta forma, completar, matizar, desechar o profundizar en las informaciones y descripciones de los diarios de campo.

3 Este grupo de software es conocido como CAQDAS: Computer Assisted Qualitative Data AnalisiS.

4 Existen diferentes tipos de software que nos ayudan a analizar datos cualitativos que podemos conocer en diferentes obras como las de Weitzman & Miles (1995), Fielding & Lee (1998) y Lewins & Silver (2007), donde nos interesan utilizar «software de construcción de teorías en base a códigos» por su complejidad y la flexibilidad que disponen para el tratamiento y análisis de datos. También, puede consultarse la web del Proyecto CAQDAS que se lleva a cabo por importantes intelectuales en el estudio de los mismos.

Referencias

Ardèvol, E. (2006). La búsqueda de una mirada. Antropología vi sual y cine etnográfico. Barcelona: Editorial UOC.

Banks, M. (2007). Using Visual Data in Qualitative Research. Lon don: Sage.

Bautista, A. (2009). Relaciones interculturales mediadas por narraciones audiovisuales en educación. Comunicar, 33, 169-179. (DOI: 10.3916/c33-2009-03-006).

Berger, P. & Luckmann, T. (1986). La construcción social de la realidad. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu-Murguia.

Blumer, H. (1982). El interaccionismo simbólico. Perspectiva y método. Barcelona: Hora.

Burn, A. (2010). Emociones en la oscuridad: Imágenes y alfabetización mediática en jóvenes. Comunicar, 35, 33-42. (DOI: 10.39 16/ C35-2010-02-03).

Crawford, P.I. & Turton, D. (1992). Film as Ethnography. Man chester: Manchester University Press.

Fielding, N.G. & Lee, R.M. (1998). Computer Analysis and Qua litative Research. London: Sage.

Geertz, C. (2001). La interpretación de las culturas. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Gergen, K.J. (1992). El yo saturado: dilemas de identidad en el mun do contemporáneo. Barcelona: Paidós.

Hammersley, M. & Atkinson, P. (1994). Etnografía. Métodos de investigación. Barcelona: Paidós.

Kushner, S. (2009). Recuperar lo personal. In J.I. Rivas & D. He rre ra (Eds.), Voz y educación (pp. 9-16). Barcelona: Octaedro.

Lewins, A. & Silver, C. (2007). Using Software in Qualitative Research: A Step-by-step Guide. London: Sage.

Mead, G.H. (1982). Espíritu, persona y sociedad. Barcelona: Paidós.

Pink, S. (2007). Doing Visual Ethnography. London: Sage.

Pink, S. (2009). Visual Interventions. Applied Visual Anthropo logy. London: Sage.

Rorty, R. (1983). La filosofía y el espejo de la naturaleza. Madrid: Cátedra.

Schutz, A. (1974). El problema de la realidad social. Buenos Ai res: Amorrortu.

Shotter, J. (2001). Realidades conversacionales. La construcción de la vida a través del lenguaje. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

Van Leeuwen, T. & Jewitt, C. (2008). Handbook of Visual Analysis. London: Sage.

Web de QSR International: (www.qsrinternational.com) (29-05-2011).

Web del Proyecto CAQDAS. (http://caqdas.soc.surrey.ac.uk) (20-05-2011).

Weitzeman, E.A. & Miles, M.B. (1995). Computer Programs for Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Wolcott, H.F. (2003). Sobre la intención etnográfica. In H.M. Velasco Maillo, F.J. García Castaño & M. Díaz de Rada (Coords.), Lecturas de antropología para educadores. El ámbito de la antropología de la educación y de la etnografía escolar (pp. 127-144). Madrid: Trotta.

Document information

Published on 30/09/12

Accepted on 30/09/12

Submitted on 30/09/12

Volume 20, Issue 2, 2012

DOI: 10.3916/C39-2012-03-07

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?