Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This research studies an assessment system of distance learning that combines an innovative virtual assessment tool and the use of synchronous virtual classrooms with videoconferencing, which could become a reliable and guaranteed model for the evaluation of university e-learning activities. This model has been tested in an online course for Secondary School Education Specialists for Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American graduates. The research was designed from a qualitative methodology perspective and involved teachers, students and external assessors. During the whole process great care was taken to preserve data credibility, consistency and reliability, and a system of categories and subcategories that represents online assessment has been developed. The results confirm that we have made considerable progress in achieving a viable, efficient and innovative educational model that can be implemented in Higher Distance Education. Also, videoconferencing and synchronous virtual classrooms have proved to be efficient tools for evaluating the e-assessment method in virtual learning spaces. However, we need to keep testing this model in other educational scenarios in order to guarantee its viability.

1. Introduction

There has been a remarkable increase in international studies on formative assessment, and the concept of assessment has aroused interest not only from a pedagogical point of view, but also from the strategic and even economic perspective, leading to a redefinition of the concept.

In our study we focus on online formative assessment, and our initial research reveals elements that are identical to those found in any assessment method and which have to be contextualized according to the specific learning situation to be observed, measured and improved. In their studies, Gikandi, Morrow & Davis (2011) state that assessment (whether formative or summative) in online learning contexts includes characteristics that differ from face-to-face contexts, especially due to the asynchronous nature of the participant’s interactivity, which means that educators must rethink pedagogy in virtual settings in order to achieve effective formative assessment strategies.

As we pointed out in a previous analysis (Blázquez & Alonso, 2006), prior to 2005 the most common topics in e-learning settings were the categorization of formative and summative assessments (Birnbaum, 2001; Wentling & Jonson, 1999), models such as the Input-Process-Output Model (Mehrotra & al., 2001) and others with similar elements (Stufflebeam, 2000; Rockwell & al., 2000; Potts & al., 2000; Forster & Washington, 2000; Moore & al., 2002).

More recent studies have focused on formative e-assessment which, as Rodríguez & Ibarra (2011:35) point out, «relies on the open, flexible and shared conception of knowledge, emphasizing the use of assessment strategies that promote and maximize the student’s formative opportunities». In this sense, Oosterhoff, Conrad & Ely (2008) stress the importance of formative assessment in online courses. In our context, Peñalosa (2010) states that to identify the progress of interactive and cognitive processes in formative virtual settings it is necessary to formulate a valid, sensitive strategy to assess performance, together with a series of tools that enable us to identify changes in the complexity of knowledge-building on the part of the students.

Weschke & Canipe (2010) present assessment guidance aimed at teachers, in which they highlight an interactive assessment process that uses indicators such as assessment of student courses, self-assessment, submitted activities and rubrics, all of which makes cooperative assessment more valuable for professional development.

More recent studies present two innovative tools for the assessment of virtual settings: eRubrics and videoconferences. Serrano & Cebrián (2011) are developing an eRubric system in Higher Education in which the student becomes the main assessor of the process. This implies a methodological change in the conception of the e-assessment agent who by tradition has always been the teacher. Regarding the use of videoconferencing, Cubo et al (2009) urge the installation of Virtual Synchronous Classrooms as learning environments in Spain, and Cabero & Prendes (2009) pointed out that initial assessment (debate on previous knowledge), processual assessment (monitoring the students’ interaction) and final assessment (oral presentations, oral exams…) could all be done via videoconference.

We consider it necessary to continue with the innovative educational proposal, since it is the formative methods and strategies that will establish the use of technology and not the other way round since, as Sancho (2011) states, technology in itself does not entail formative innovation and it can even reinforce conservative behaviour and discourage participation. E-learning is enabling teacher and students to explore new formative and collaborative methods with the flexibility that conventional educational structures are unable to offer.

Our interest in trying out an innovative formative e-assessment system led our research team to design a specific proposal for an online Secondary Education Specialist course aimed at graduates from Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American universities wishing to train as secondary education teachers. Our virtual learning proposal considered an environment that was designed to be flexible, based on access to original and varied sources, and with the students as active participants in their own training, accompanied by a team of coordinated and inter-functional teachers who shared responsibility for the process both individually and in a group setting. In this process the interaction formulas were negotiated and priority was given to problem solving, alternating individual and collaborative work, and offering a rich diversity of materials (media) and continuous formative and comprehensive assessment with dialogue as the main premise.

Throughout the course, the aim was for students to acquire the knowledge and skills necessary to reflect, analyze and criticize the main contents that shape the formative aspects of a secondary or middle school teaching in different Western countries and train them to carry out their functions at that level of education.

The constructivist approach implemented in the course was based on a virtual training design executed in the Moodle platform that combined a learning activity that fostered collaborative work with cooperation among students and between students and teachers. One of the training focal points was the learning and support-mentoring model. The tutor was responsible for the entire training process and assessment of the student who in turn received input from specialist teachers and continuous and distance assessment reinforced by self-assessment, co-assessment and interviews via videoconference.

The assessment and qualification system proposed for the course is a flexible model, adapted to the circumstances of the course and the students, where learning was assessed throughout the training process itself and included online tasks which were evaluated from the perspective of individual and group learning. All this was embodied in individual activities, collaborative activities, a final monograph project, interview via videoconference and in other issues such as active and quality participation.

For the interview via videoconference as assessment element, we used Adobe Connect’s Synchronous Virtual Classroom whose functions include, among others, online and live conferences between users. The meeting room includes several visualisation panels (pods) and components, and also allows several users, or meeting attendees, to share computer screens or files, chat, transfer live audio or video and participate in other interactive activities online.

With this context and the pedagogical experience stated, we aimed to carry out research to develop and check the viability of a formative assessment system for reliable online teaching with knowledge accreditation guaranteed, without the need for the physical presence of the higher education student. At the same time we aimed to:

• Collaborate in the innovation and development of e-learning as an educational change agent, particularly in line with the proposals for the European Higher Education Area.

• Experiment with the suitability of the Moodle open software platform for the students’ individual and collaborative work and for the final interview via videoconference as part of the online assessment we are testing.

2. Materials and methods

The study examines assessment in virtual learning settings within a specialist university course for students who want to train as secondary education teachers. The distinguishing feature of the course for the students, together with the singularity of the proposed methodology and assessment evaluation ), is the basis of the qualitative research proposal; as Rodríguez, Gil & García (1999) assert, it is about studying reality in its natural context to give meaning or interpret the phenomena according to the meanings they have for those involved. This study aims to give special meaning to the subjective aspects of the actors of the action, and is interested in the impressions and observations of the participants who can deduce the theories inductively.

Following Rodríguez, Gil & García (1999), the research has been developed in four stages: a preliminary stage, fieldwork, an analytical stage and a informative stage. In this section we will describe the preliminary stage and the fieldwork with the results and discussion to follow.

• Preliminary stage: This stage is developed out of the research’s conceptual theoretical framework. The field to be studied is defined in this stage, together with the different stages of the qualitative research design and the description of the object to be studied, the triangulation, the data collection tools and techniques along with the analysis to be developed.

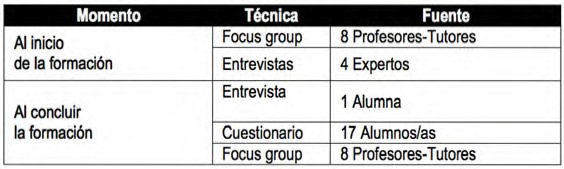

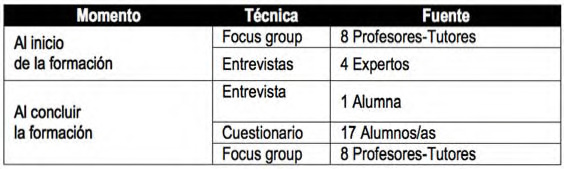

• Field work: This was the data collection, which was carried out at the beginning of the specialist course and after it had finished.

2.1. Participants

• Teachers or tutors are essentially characterized by their university and psycho-pedagogical training, so they are particularly familiar with teaching/learning models. There were eight participants.

• The students were graduates who had gained a variety of university degrees and who wanted to obtain a diploma to certify their psycho-pedagogical knowledge and training to educate secondary school students. Twenty students participated.

• The group of experts was made up of four teachers, highly specialised in teaching/learning systems. Three were specialists and members of distance learning institutions, two of whom were from the Open University (United Kingdom) and a third was from the UNED (Spain). The fourth member is a renowned Spanish expert in virtual training.

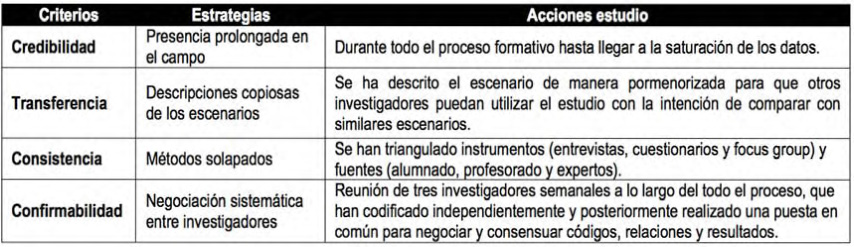

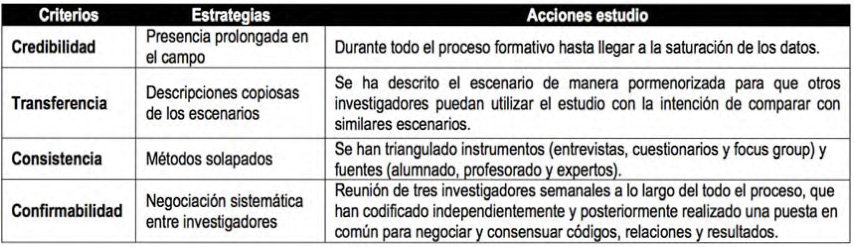

2.2. Rigorous methodology

A constant throughout the process has been the rigorous methodology in the design and development of the study. This enabled us to generate evidential data, i.e., consolidate the research’s rigour and relevance. To do so we controlled the four concepts that according to Rodriguez, Gil & Garcia (1999) are essential: credibility, transfer, consistency and validation.

3. Results

3.1. Data synthesis

To divide this study into units we followed a thematic approach that considered talks, events and activities taking place in the same situation studied and the possibility of finding segments that speak about a similar subject. This procedure enabled us to synthesize and create group units of meaning that match the study objectives.

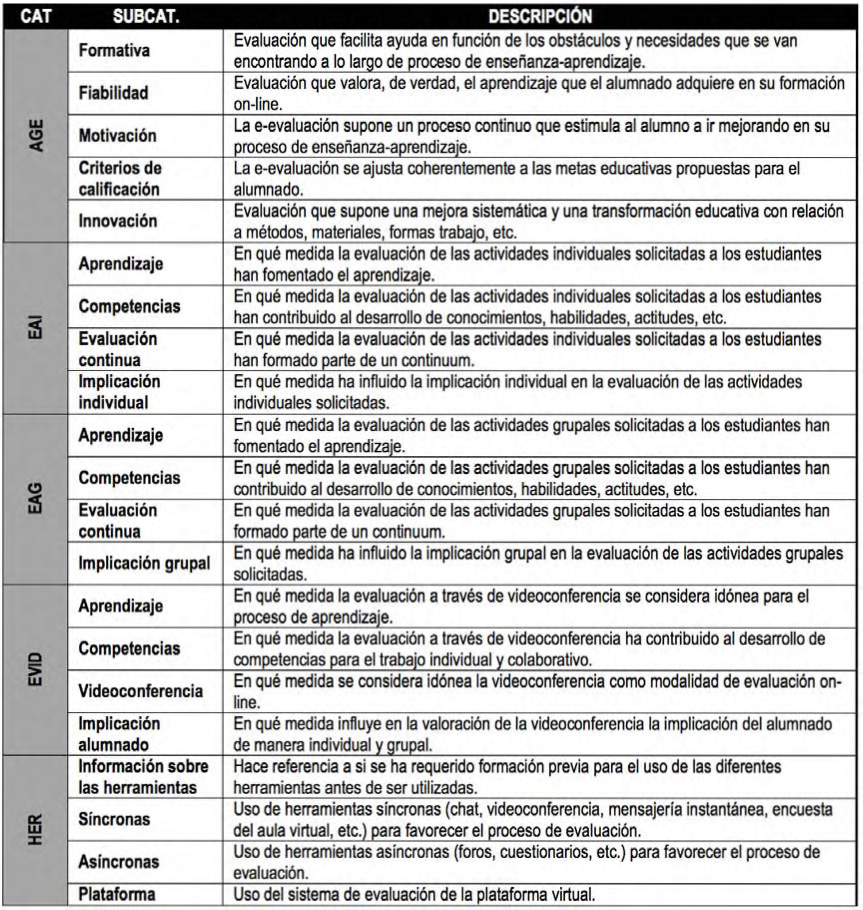

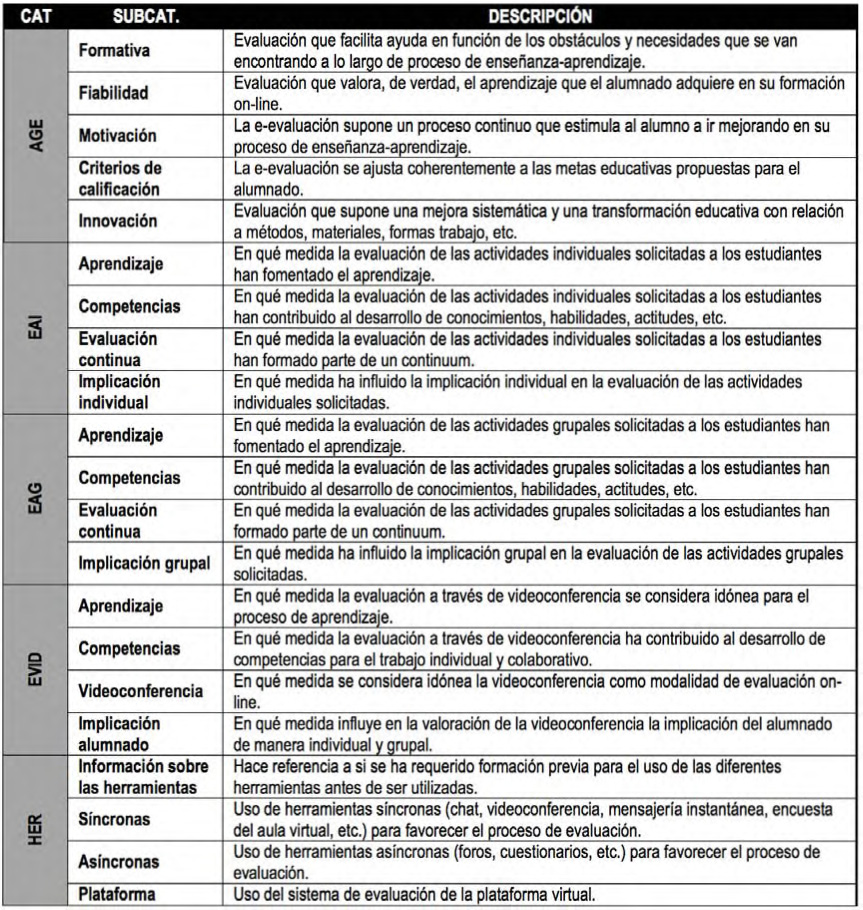

For the identification and classification of items we devised a system of categories and sub-categories following a deductive-inductive classification. Deductively, since it was based on a previous research study (Alonso & Blázquez, 2009) that helped define the initial macro-categories. Inductively, because we then proceeded to devise new codes, categories and sub-categories from the recorded data. The final category system is described below (the sub-categories that arise from the study are described in Table 3):

3.2. Disposition and data transformation

For this stage we used the NVIVO qualitative data analysis software, which made the coding and analysis of the transcriptions or documents much easier. It helped us to store, organize and extract summarized reports of the most significant data emerging from the analysis, in addition to combine two dimensions in our analysis by integrating a narrative perspective and a more analytical one.

In this phase of the analysis process the results in Figure 1 are presented by category and technique, indicating which category was addressed in each technique and if the assessment was positive or negative:

Results that answer the data in Figure 1 are:

a) Open questionnaire for the students. In the General Aspects of the Assessment (GAA) category, the students surveyed (15 of the 17 questionnaires analyzed) were pleased overall with the type of assessment proposed: «From my point of view, the assessment includes all four dimensions of the assessment process, that is: prior design of the criteria, a comparison of information to obtain a balanced judgment, a decision-making process and the communication of results» (student).

Some students suggested changes in the qualification system motivated by purely subjective aspects. They define assessment as follows: «Continuous training has been very good and we have been able to discuss and develop it with thematic forums for each issue. The activities proposed and implemented have been useful to consolidate the acquired knowledge or to work with it in a slightly more practical way, not so theoretical. With the final project, we have been able to work with that acquired knowledge, while we have studied it more in depth and through which we have been able to demonstrate it, as with the final interview» (student, questionnaire).

Regarding the Assessment of Individual Activities (AIA), 12 of the 17 students surveyed valued these activities very highly for enhancing the teaching-learning process and, therefore, the assessment: «With the completion of activities you learn a lot, because to be able to carry them out you must study and understand the theory and then put it into practice. And that is how you best learn the content» (student).

Likewise, there are many references in the text in relation to continuous assessment, with students especially valuing this point (all 17 course students). In fact, this is why most of them consider it a good assessment system: «Overall I thought it was a good assessment system, taking into account the course’s characteristics. The system used has made us work on the content on a daily basis. With the individual and group activities, and participation in the forums, you can achieve such a goal» (student).

The students generally consider the individual activities requested by the teachers as a very effective tool to ensure the quality of the course’s assessment system. As for the Assessment of Group Activities (AGA), students mainly ignored this category, but those who answered (3 out of 17) were very positive in their judgment, as one student says: «With the final project I was able to consolidate the contents dealt with on the course, and to study in depth other related issues».

The students know that these activities do not work on their own and they point out as positive aspects both the maintenance of the platform where the activities were found and the tutoring by the course teachers-tutors.

In relation to the tools used for the videoconference (AVID), the students said their experience of the forums was positive, and the tools themselves were highly rated; once again they emphasized the continuous feedback from the teachers-tutors. Regarding the Assessment via Videoconference category, students want more eye contact throughout the course, with occasional videoconferences every so often.

b) Interview with a course student. In the assessment of Individual Activities Requested from the Student (AIA), the interviewee appreciates the fact that more value or weight is given to the activities since she considers that «it is the best way to learn».

As for the Assessment of Group Activities (AGA), the online chat experience was not rated very highly because the students found it difficult to establish effective written communication, and so the tool was not well-received. In Assessment via Videoconference (AVID), the student addressed the assessment issue to ensure that the person behind the screen and the person carrying out the exercises was really the person studying for the diploma, which is closely related to the reliability sub-category of General Aspects of the Assessment. In a very subjective manner the student says: «In my case the grade obtained is reliable, but I do not know if some people could be cheating, I hadn’t even thought about that. Yesterday I told my grandmother, that somebody could do another person’s exercises, but maybe I am not very clever and had not thought of that».

c) Focus group. In our analysis of the two focus groups set up with the course teachers-tutors the teachers rate the course highly in terms of the General Aspects of the Assessment (GAA). A recurring topic was that of assessment criteria, namely the percentage allocation criteria, as several of the teachers (6 out of 8 teachers-tutors) believe that the individual activities should have more weight due to the work done by the students and their personal participation.

Regarding the Assessment of Individual Activities Requested from the Student (AIA), the teachers-tutors admit that these activities enabled to them to make a more accurate assessment, since they helped them to get to the students they were evaluating: «What happens is that on a course like this, with so few students, and intense supervision, the assessment has been continuous. We carried out an extremely accurate assessment of who they were, what they were doing, why they were not doing it, why they were late submitting the activities» (course teacher-tutor).

As for the Assessment of Group Activities (AGA), the views varied: 60% of the teachers argue that no work was carried out 100% collaboratively, because the students simply divided up the work and then joined it together. Other teachers-tutors, however, stated that the group activities had truly given them the criteria to get to know the students better and evaluate them.

In Assessment via Videoconference (AVID), we found that some teachers (2 of the 8 tutors) were reluctant to use the videoconference systems. «They are not reliable, at least not for me (...) in my case, the entire course went great, but as I was telling tutor 2, for me the assessment... in fact, I had only two students, because two left, one via webcam, the other via telephone. The one over the phone, I questioned him about activities, about the subject, to see what had been done and how. Well, imagine when he could not answer me directly because the communication kept cutting off, and I called again and asked the same question. And with the webcam, exactly the same, it didn’t work...» (teacher-tutor). However, another group (65%) was inclined to use the videoconference systems as a communication and assessment tool, and were very satisfied with this completely virtual experience since they were able to accredit the knowledge acquired, emphasizing the need for more virtual interviews during the course.

Finally, the teachers said that this course had been the most innovative they had worked on, despite the need for more work to be done on certain pedagogical aspects.

d) Interviews with experts. Experts provided information on three of the categories, first on the Assessment of Individual Activities Requested from the Students (AIA), where they emphasize the importance of continuous assessment: «I think a continuous assessment of the individual and group contributions is essential in these settings» (assessment expert).

As for the Assessment of Group Activities Requested from the Students (AGA), the experts focus on the need for a good online chat system for synchronous communication and even for the final assessment.

In the Assessment via Videoconference (AVID), one of the experts focused on its reliability: «Many times in a face-to-face setting we tell the students to start creating an electronic portfolio, in the end they will submit a project or a research report. What we know is that the students have given it to us physically, but we don’t have the mechanism, we have it when we are talking to them. This can be done online, but you have to find another criterion and the criterion is that the student-tutor ratio cannot be very high» (expert). In addition, another expert clarifies that «If you are doing an online course properly you know your students well, and it would be impossible for them to ‘cheat’ in their work. The important thing is that if it is well-designed I assure you they do not lie» (expert).

Finally, experts have also called attention to the need to establish coherence between the training model and the assessment system, so that the necessary means to enable online and distance assessment are arbitrated whenever the formative model follows these parameters.

4. Discussion

In this study we have presented an online assessment model that does not require the presence of the students, based on a constructive consideration of knowledge where learning can and should be assessed and evaluated throughout the training process itself, with tasks that can be assessed from the perspective of individual and group learning. The assessment of this study has helped us establish the following conclusions:

1) Progress has been made in achieving an innovative model for feasible and effective e-assessment, which ensures its use in distance higher education, which is valued as a highly beneficial contribution for those following e-learning models anchored in standard summative assessments, arising from traditional teaching processes.

2) It can be asserted that the assessment we propose is formative: it is part of a process and enables improvement throughout. We therefore follow the line of argument of Rodriguez & Ibarra (2011) who defend that e-assessment must be a learning opportunity designed to improve and promote meaningful learning and which is currently not employed in universities because their system continues to place emphasis on the teachers’ workload rather than in the students’ learning.

3) Most students consider the assessment followed as a highly motivating method since, in addition to the different techniques and tools used, the assessment is considered to be part of the teaching-learning process and not only an activity that takes place at the end of the course.

4) According to the degree of satisfaction of the students, experts and teachers, the results show that progress has been made in several key directions for a much more active teaching that relies less on memory and is more focused on the students’ workload and, importantly, with an assessment model that does not require a face-to-face setting. This corroborates the contributions made by Sloep & Berlanga (2011), who propose the creation of learning networks beyond the universities’ borders.

5) The results of this study bring together teaching innovation intended for universities with e-learning as agent for educational change. The use of interviews via videoconference is the most significant innovation in our study, although it could be improved as an assessment method since it still generates insecurities when used as an assessment tool. However, the experience is considered highly positive and, although we must continue to sharpen the technique, it seems we are on the right track. As suggested by Blázquez (2004) we must use these technologies to innovate and not to repeat ineffective traditional models, misusing synchronous resources (such as videoconference) at the expense of asynchronous resources (website, e-mail, discussion forums, etc.).

6) The formative assessment model tested provides regulated university activities for students who are unable to attend face-to-face final exams due to reasons of distance, which points to a huge potential educational market for our universities, especially in Latin American countries.

7) As noted by Solectic (2000), the specificity of the teaching materials demands a series of activities that help students put their resources, strategies and skills into practice, and which encourage them to participate in the knowledge-building process. This, from the beginning, was the purpose of the individual activities and, as we have established, the students have also understood individual activities in the same way, since they receive the highest rating as a continuous assessment standard.

8) In general, the implementation of this online assessment method has been positive, especially when focusing on continuous assessment throughout the activities, projects and interviews (via videoconference), together with a tutorial model that ensures the supervision of the student’s learning progress, enhanced by a manageable ratio of five students per tutor. In turn, this is reinforced by the distinctiveness of the pilot scheme in which the teachers were selected for their desire to participate and motivation.

9) There is always scope for improvement, with minor changes concerning the flexibility of the assessment activities and the singular valuation of collaborative activities, which have to go beyond simple task distribution. An increase in the number of interviews should also be encouraged, which in turn will give teachers greater confidence when dealing with Synchronous Virtual Classroom technology.

10) We conclude by pointing out that, based on qualitative transfer criteria, we encourage the teaching community to build similar scenarios to implement formative e-assessment processes and to follow the principles presented in the study.

References

Alonso, L. & Blázquez, F. (2009). Are the Functions of Teachers in E-learning and Face-to-Face Learning Environments Really Different? Educational Technology & Society, 12(4), 331-343.

Birnbaum, B.W. (2001). Foundations and Practices in the Use of Distance Education. Lewiston, NY: Mellen Press.

Blázquez, F. & Alonso, L. (2006). Aportaciones para la evaluación on-line. Tarraconensis, Edició Especial, 207-228.

Blázquez, F. (2004). Nuevas tecnologías y cambio educativo. In F. Salvador, J.L. Rodríguez & A. Bolívar (Eds.), Diccionario En ciclopédico de Didáctica (pp.345-353). Málaga: Aljibe.

Cabero, J. & Prendes, M.P. (2009). La videoconferencia. Apli caciones a los ámbitos educativo y empresarial. Sevilla: MAD.

Cubo, S., Alonso, L., Arias, J., Gutiérrez, P., Reis, A. & Yuste, R. (2009). Modelización didáctica-pedagógica, metodológica y tecnológica de las aulas virtuales: implantación en la Universidad de Extremadura. In J. Valverde (Ed.), Buenas prácticas educativas con TIC. Cáceres: SPUEX.

Forster, M. & Washington, E. (2000). A Model for Developing and Managing Distance Education Programs Using Interactive Video Technology. Journal of Social Work Education, 36(1), 147-59.

Gikandi, J.W., Morrow, D. & Davis, N.E. (2011). Online Formative Assessment in Higher Education: A Review of the literature. Computers & Education 57, 2.333-2.351.

Mehrotra, C.M., Hollister, C.D. & McGahey, L. (2001). Distance Learning: Principles for Effective Design, Delivery and Evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Moore, M., Lockee, B. & Burton, J. (2002). Measuring Success: Evaluation Strategies for Distance Education. Educause Quarterly, 25(1), 20-26.

Oosterhoff, A., Conrad, R.M. & Ely, D.P. (2008). Assessing Learners Online. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Peñalosa, E. (2010). Evaluación de los aprendizajes y estudio de la interactividad en entornos en línea: un modelo para la investigación. RIED, 13 (1), 17-38.

Potts, M.K. & Hagan, C.B. (2000). Going the Distance: Using Systems Theory to Design, Implement, and Evaluate a Distance Edu cation Program. Journal of Social Work Education, 36(1), 131-145

Rockwell, K., Furgason, J. & Marx, D.B. (2000). Research and Evaluation Needs for Distance Education: A Delphi Study. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, III.

Rodríguez, G. & Ibarra, M.S. (2011). e-Evaluación orientada al e-aprendizaje estratégico en educación superior. Madrid: Narcea.

Rodríguez, G., Gil, J. & García, E. (1999). Metodología de la investigación cualitativa. Málaga: Aljibe.

Sancho, J. (2011). Entrevista a Juana María Sancho Gil. En Edu cación y Tecnologías. Las voces de los expertos. Buenos Aires: An ses.

Serrano, J. & Cebrián, M. (2011). Study of the Impact on Student Learning Using the eRubric Tool and Peer Assessment. In Varios: Education in a Technological World: Communicating Current and Emerging Research and technological efforts. EDIT. Formatex Research Center (In press).

Sloep, P. & Berlanga, A. (2011). Redes de aprendizaje, aprendizaje en red. Comunicar, 37, XIX, 55-64. (DOI: 10.3916/C37-2011-02-05).

Solectic, A. (2000). La producción de materiales escritos en los programas de educación a distancia: problemas y desafíos. In L. Litwin (2000), La educación a distancia. Temas para el debate en una nueva agenda educativa. España: Amorrortu.

Stufflebeam, D.L. (2000). Guidelines for Developing Evaluation Checklists. (www.wmich.edu/evalctr/checklists) (15-12-2011).

Wentling, T. & Johnson, S. (1999). The Design and Develop ment of an Evaluation System for Online Instruction. www.universia.pr/cultura/videoconferencia.jsp. (30-09-2011).

Weschke, B. & Canipe, S. (2010). The Faculty Evaluation Process: The First Step in Fostering Professional Development in an Online University. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 7(1), 45-58.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

En el presente trabajo de investigación se somete a estudio un sistema de evaluación de los aprendizajes en enseñanza a distancia en el que, combinando un tipo de evaluación virtual pedagógicamente innovadora y el uso de aulas virtuales síncronas, con videoconferencia, pueda acreditarse un modelo fiable y garante de evaluación de los procesos de enseñanza/aprendizaje para actividades de e-learning universitarias. El modelo se ha probado en un curso online de Especialista en Educación Secundaria dirigido a titulados universitarios españoles, portugueses y latinoamericanos. Desde una perspectiva metodológica cualitativa, se diseñó una investigación cuyos participantes han sido el profesorado y el alumnado protagonistas de la formación, así como evaluadores externos. Durante todo el proceso se han cuidado especialmente los aspectos relacionados con la credibilidad, consistencia y confirmabilidad de los datos obtenidos, extrayendo de modo inductivo un sistema de categorías y subcategorías que representan la evaluación de los aprendizajes en procesos formativos online. Los resultados confirman que se ha avanzado en la consecución de un modelo innovador de e-evaluación viable, eficaz y que garantiza su aplicación en enseñanza superior a distancia. Asimismo, el uso de videoconferencias y de las aulas virtuales síncronas para realizar entrevistas de eevaluación ha resultado ser un instrumento eficaz en espacios virtuales de aprendizaje. De cualquier modo, se evidencia la necesidad de continuar experimentando este modelo en otros escenarios educativos.

1. Introducción

Los estudios sobre evaluación educativa han alcanzado una notable expansión a nivel internacional. El propio concepto de evaluación ha concitado numerosos intereses no solo desde el punto de vista pedagógico, sino también estratégico e incluso económico, lo que ha propiciado la modificación y precisión de su definición en los últimos años.

Centramos nuestro estudio en la evaluación on-line de los aprendizajes, donde de partida encontramos elementos idénticos a los que surgen en cualquier sistema de evaluación y que habrán de ser contextualizados conforme a la situación concreta de aprendizaje a observar, medir y mejorar. En sus estudios, Gikandi, Morrow y Davis (2011) indican que la evaluación –ya sea formativa o sumativa– en contextos de aprendizaje en línea incluye características distintivas en comparación con los contextos presenciales, en particular debido a la naturaleza asíncrona de la interactividad entre los participantes. Por lo tanto, exige a los educadores repensar la pedagogía en ambientes virtuales, a fin de lograr estrategias efectivas de evaluación formativa.

Con anterioridad a 2005, el tema más común que hemos encontrado en entornos de e-learning ha sido el de la clasificación de las evaluaciones entre formativa y sumativa (Birnbaum, 2001; Wentling & Jonson, 1999), modelos como el Input-Proceso-Output (Mehrotra & al., 2001) y otros derivados que contemplan componentes similares (Stufflebeam, 2000; Rockwell & al., 2000; Potts & al., 2000; Forster & Washington, 2000; Moore & al., 2002), tal y como señalamos en revisiones anteriores (Blázquez y Alonso, 2006).

Estudios más actuales comienzan a centrar sus esfuerzos en la e-evaluación de aprendizajes, que tal y como destacan Rodríguez e Ibarra (2011:35): «se apoya en la concepción abierta, flexible y compartida del conocimiento, centrando la atención en el uso de estrategias de evaluación que promueven y maximizan las oportunidades de aprendizaje de los estudiantes». En esta línea, Oosterhoff, Conrad y Ely (2008) destacan la importancia de la evaluación formativa en los cursos que se desarrollan online.

En nuestro contexto, Peñalosa (2010) defiende que para identificar el progreso de los procesos cognitivos e interactivos en entornos virtuales de aprendizaje, es necesario contar con una estrategia sensible y válida de evaluación del desempeño, así como una serie de herramientas que permitan detectar cambios en la complejidad de las construcciones de conocimientos por parte de los estudiantes.

Weschke y Canipe (2010) presentan orientaciones de evaluación dirigidas al profesorado, y destacan un proceso de evaluación interactiva donde se utilizan indicadores como la evaluación de los cursos de los estudiantes, la autoevaluación, actividades presentadas y el cumplimiento de rúbricas, otorgando valor a la evaluación cooperativa para el desarrollo profesional.

Dentro de los últimos estudios realizados detectamos dos instrumentos que implican innovación en la evaluación en entornos virtuales, serían las e-rúbricas y el uso de videoconferencias. Serrano y Cebrián (2011) están desarrollando un sistema de e-rúbricas en educación superior en el que el estudiante desempeña el rol de evaluador principal del proceso, lo que supone un cambio metodológico en la concepción del agente de la e-evaluación, que por tradición ha sido el profesorado. Con respecto a la videoconferencia, destacamos en el ámbito nacional los esfuerzos de Cubo y otros (2009) por incluir las aulas virtuales síncronas como espacios de aprendizaje, así como los de Cabero y Prendes (2009), quienes destacan que a través de la videoconferencia se puede llevar a cabo evaluación inicial (debate sobre conocimientos previos), procesual (seguimiento de la interacción del alumnado) y final (exposiciones orales, exámenes orales…).

Consideramos necesario trabajar en la línea de propuestas educativas innovadoras, pues los métodos y estrategias docentes serán los que determinarán el uso de la tecnología, y no al contrario, ya que estamos de acuerdo con Sancho (2011) en que la tecnología por sí misma no supone innovación docente, sino que a veces, sirve para reforzar comportamientos conservadores y escasamente participativos. El e-learning está permitiendo a profesores y estudiantes explorar nuevos modos de aprendizaje y colaboración, desde la flexibilidad que las configuraciones educativas convencionales no suelen ofrecer.

Interesados en probar un sistema de e-evaluación de los aprendizajes innovador, desde nuestro equipo de investigación se diseñó una propuesta específica para un curso on-line de especialista en Educación Secundaria dirigido a personas tituladas universitarias españolas, portuguesas y latinoamericanas que desearan formarse para ser docentes en Educación Secundaria. Nuestra propuesta de enseñanza virtual contemplaba un entorno concebido como flexible, basado en el acceso a fuentes originales y variadas, para unos estudiantes considerados participantes activos en su propia formación, acompañados por un equipo de profesores coordinado e interfuncional que compartía con los estudiantes, tanto individualmente como en grupo, la responsabilidad del proceso. Un proceso en el que se negociaban las fórmulas de interacción y donde primaba la resolución de problemas, en el que se alternaba el trabajo personal y el cooperativo, y que ofrecía una rica diversidad de materiales (multimedia), y una evaluación continua, formativa e integral, cuya principal premisa es el diálogo. A lo largo del curso, se pretendía que los estudiantes adquirieran conocimientos y destrezas necesarias para reflexionar, analizar y someter a crítica los principales contenidos que configuran los aspectos formativos de un profesor de enseñanza secundaria o media en distintos países del mundo occidental y formarlo para su desempeño en ese nivel educativo.

La metodología constructivista que se implementó en el curso partía de un diseño formativo virtual en la plataforma Moodle que combinaba una actividad didáctica que fomentaba el trabajo colaborativo y en la cooperación del alumnado entre sí y de alumnos/profesores. Uno de los ejes de la formación fue el modelo tutorial de aprendizaje y acompañamiento, en tanto que el tutor se encargaba de todo el proceso formativo y de su evaluación del estudiante, que a su vez recibía aportaciones de profesores especialistas, experimentando una evaluación continua y a distancia reforzada por autoevaluación, coevaluación y entrevistas a través de videoconferencia.

El sistema de evaluación y calificación que se propuso para el curso era un modelo flexible, adaptado a las circunstancias del curso y de los estudiantes, donde el aprendizaje se evaluó a lo largo del propio proceso formativo incluía tareas en línea y evaluadas desde la perspectiva del aprendizaje individual y grupal. Todo esto se concretaba en actividades individuales, actividades colaborativas, trabajo monográfico final, entrevista mediante videoconferencia y otros aspectos como la participación activa y de calidad.

Para la entrevista por videoconferencia como elemento evaluador, hemos utilizado la aplicación de prueba que nos presenta el Aula Virtual Síncrona de Adobe Connect. En este programa entre otras muchas aplicaciones se encuentran las reuniones, conferencias en línea y en directo entre varios usuarios. La sala de reuniones contiene diversos paneles de visualización (pods) y componentes. Y permite a varios usuarios, o asistentes a la reunión, compartir pantallas de ordenador o archivos, chatear, transmitir audio y vídeo en directo y participar en otras actividades interactivas en línea.

En este contexto y con la experiencia pedagógica indicada, nos propusimos realizar una investigación cuyo objetivo fundamental fue desarrollar y comprobar la viabilidad de un sistema de evaluación de los aprendizajes para la enseñanza virtual fiable y con garantías de acreditación de conocimientos, sin necesidad de la presencia física del estudiante de enseñanza superior. Al tiempo pretendimos:

• Colaborar en la innovación y el desarrollo del e-learning como agente de cambio educativo, particularmente en lo que se propone desde el Espacio Europeo de Enseñanza Superior.

• Experimentar la idoneidad de la plataforma de software libre Moodle para el trabajo individual y colaborativo de los alumnos para la realización de la entrevista final a través de videoconferencia como elemento para la evaluación online que probamos.

2. Material y métodos

El estudio que se presenta investiga la evaluación en entornos virtuales de aprendizaje, correspondiente a un curso de especialista universitario para personas que desean formase como docentes de secundaria. Las peculiaridades de los estudiantes del curso, así como la singularidad de la metodología y del sistema de evaluación propuestos para el mismo (descritos ya en la introducción), son la fundamentación de una propuesta de investigación de corte cualitativo; en tanto que, tal y como afirman Rodríguez, Gil y García (1999), se trata de estudiar la realidad en su contexto natural para dar sentido o interpretar los fenómenos de acuerdo con los significados que tienen para las personas implicadas. En definitiva, este estudio trata de otorgar especial significado a los aspectos subjetivos de los propios actores de la acción, interesándose en las impresiones y reflexiones de los participantes para poder extraer teorías de una manera inductiva.

Siguiendo a Rodríguez, Gil y García (1999), se ha desarrollado la investigación en cuatro fases: preparatoria, trabajo de campo, fase analítica e informativa. En este apartado explicaremos las fases preparatorias y el trabajo de campo desarrollado. Los apartados referentes a los resultados y su discusión los mencionaremos posteriormente.

Fase preparatoria: de la que surge el marco teórico conceptual de la investigación. En ella se definió el campo de estudio, así como las diferentes etapas del diseño de investigación cualitativa, describiendo el objeto de estudio, la triangulación, las técnicas e instrumentos de recogida de datos y los tipos de análisis a desarrollar.

Trabajo de campo: consistió en la recogida de datos, que se realizó en dos espacios temporales, en el inicio y tras la conclusión del curso de especialista.

2.1. Participantes

• Los profesores o tutores se caracterizan fundamentalmente por su formación de corte universitario y psicopedagógico, lo que quiere decir que están especialmente familiarizados con modelos de enseñanza/aprendizaje. Participaron ocho.

• Por otro lado, el alumnado, diplomados y/o licenciados en distintas carreras universitarias que deseaban obtener una certificación que avalara sus conocimientos psicopedagógicos y su preparación para formar alumnos de educación secundaria. Participaron 20.

• Los expertos han sido cuatro profesores altamente especializados en sistemas de enseñanza/aprendizaje, tres de ellos especialistas y miembros de instituciones de enseñanza a distancia. Dos de ellos de la Open University (Reino Unido) y un tercero de la UNED (España), el cuarto es un español de reconocido prestigio en formación virtual.

2.2. Rigor metodológico

Una constante durante todo el proceso ha sido el rigor metodológico con el que ha sido diseñada y desarrollada la investigación. Esto nos permite crear evidencias, es decir, fortalecer la investigación con rigor y pertinencia. Para ello hemos controlado los cuatro conceptos que según Rodríguez, Gil y García (1999) son imprescindibles: la credibilidad, la transferencia, la consistencia y la confirmabilidad.

3. Resultados

3.1. Reducción de datos

Para la separación en unidades en este estudio se utilizó principalmente el criterio temático, considerando conversaciones, sucesos, actividades que ocurren en la misma situación estudiada y la posibilidad de encontrar segmentos que hablan de un mismo tema. Este procedimiento nos ha llevado a crear una síntesis y agrupamiento en unidades de significación que se correspondían con los objetivos del estudio.

Con respecto a la identificación y clasificación de elementos es recomendable destacar que se creó un sistema de categorías y sub-categorías de manera deductiva-inductiva. Deductivamente, en tanto que se fundamentó en un estudio de investigación previo (Alonso & Blázquez, 2009) que permitió definir las macrocategorías iniciales. Inductivamente, dado que posteriormente se procedió a la elaboración de nuevas codificaciones, categorías y subcategorías, a partir de los registros realizados. El sistema de categorías finales se expone a continuación (las sub-categorías emergentes del estudio se describen en la tabla 3).

3.2. Disposición y transformación de datos

Para esta fase se utilizó el software de análisis de datos cualitativos NVIVO que facilita notablemente la codificación y análisis de las transcripciones o documentos. Nos ha permitido almacenar, organizar y obtener informes resumidos de los datos más significativos que iban emergiendo del análisis, así como combinar una doble dimensión en nuestro análisis integrando una perspectiva narrativa y otra más analítica.

En esta fase del proceso de análisis se presentan los resultados a través de la gráfica 1 por categorías y técnicas, indicando qué categoría se abordó en cada técnica y si la valoración realizada fue positiva o negativa.

A continuación destacamos algunos resultados en los que se da respuesta a los datos de la gráfica 1:

a) Cuestionario abierto al alumnado. Con respecto a la primera categoría, aspectos generales de la evaluación (AGE), el alumnado encuestado (15 de los 17 cuestionarios analizados) se ha mostrado satisfecho en términos generales con el tipo de evaluación planteada: «Desde mi punto de vista la evaluación comprende las cuatro dimensiones del proceso de evaluación, es decir, hay un diseño previo de los criterios, un contraste de información para la obtención de un juicio ponderado, adopción de decisiones y comunicación de los resultados» (alumno).

De cualquier modo, hay estudiantes que sugieren cambios en el sistema de calificación, motivados por aspectos meramente subjetivos. Definen la evaluación de este modo: «La formación continua ha sido muy buena y se ha podido debatir y complementar la formación a través de los foros temáticos de cada uno de los temas. Las actividades propuestas y realizadas han servido, para afianzar conocimientos adquiridos o trabajarlos de una manera un poco más práctica, no tan teórica. Y mediante el proyecto final, hemos podido trabajar con esos conocimientos adquiridos, a la vez que se ha profundizado aún más en ellos y a través del cual hemos podido demostrarlos, al igual que con la entrevista final» (alumno, cuestionario).

Con respecto a la evaluación de las actividades individuales (EAI), 12 de los 17 alumnos y alumnas encuestados, han valorado muy positivamente el uso de las mismas para favorecer los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje y por tanto la evaluación: «Con la realización de las actividades se aprende mucho, ya que para realizarlas has de estudiar y comprender los contenidos teóricos y después llevarlos a la práctica que es como mejor se aprenden los contenidos» (alumna).

Asimismo, son amplias las referencias en el texto en relación a la evaluación continua, descubriendo que el alumnado confiere especial valor a este aspecto (los 17 alumnos y alumnas del curso), de hecho es la razón por la que la mayoría de ellos consideran que es un buen sistema de evaluación: «En general me ha parecido un buen sistema de evaluación teniendo en cuenta las características del curso. El sistema empleado ha hecho, que los contenidos se trabajasen diariamente. Con las actividades individuales y colectivas, y la participación en los foros se puede conseguir dicho objetivo» (alumno).

En general, el alumnado ha valorado las actividades individuales solicitadas por parte de los profesores como una herramienta muy eficaz para garantizar la calidad del sistema de evaluación del curso. En cuanto a la evaluación de las actividades grupales (EAG), el alumnado no ha prestado mucha atención a esta categoría, pero quien lo hace (3 de los 17 encuestados) lo realiza de manera muy positiva como afirma una alumna: «Con el trabajo final he podido afianzar mejor los contenidos tratados en el curso, así como profundizar en otros temas relacionados».

El alumnado tiene claro que estas actividades no funcionan solas y señala como aspectos positivos tanto el mantenimiento de la plataforma donde se encontraban las actividades, como la tutorización que se ha realizado por parte de los profesores-tutores del curso.

En relación a las herramientas utilizadas para la videoconferencia (EVID), el alumnado destaca como positivo el uso de foros, que son valorados como una herramienta excelente, destacando una vez más el continuo feed-back producido por parte de los profesores-tutores. Con respecto a la categoría evaluación a través de videoconferencia, el alumnado demanda más contacto visual a lo largo del curso, con videoconferencias puntuales cada cierto tiempo.

b) Entrevista realizada a una alumna del curso. Respecto a la evaluación de las actividades individuales solicitadas al alumnado (EAI), la entrevistada valora positivamente que se otorgue mayor valor o peso a las actividades, pues considera que «es como mejor se aprende».

En cuanto a la evaluación de las actividades grupales (EAG) en la entrevista se destacó la experiencia del chat como negativa, pues al alumnado le resultó complicado establecer una comunicación escrita eficaz, resultando el uso de la herramienta problemática. Finalmente en cuanto a la evaluación de la videoconferencia (EVID), la alumna abordó el tema de evaluación para garantizar que la persona que está detrás y que realiza los ejercicios es realmente la persona que obtiene el diploma, con lo que está muy relacionado con la subcategoría fiabilidad de los aspectos generales de la evaluación. De una manera muy subjetiva una alumna nos contesta al respecto que: «En mi caso la nota obtenida es fiable, pero no sé si hay gente que podrá hacer trampa, yo no me lo había planteado. Ayer se lo comentaba a mi abuela, que puede hacer las actividades otro, pero yo a lo mejor soy muy tonta y no había pensado en eso».

c) Focus group. Se analizan los dos focus group que se llevaron a cabo con los profesores tutores del curso. Con respecto a los aspectos generales de la evaluación (AGE), el profesorado ha valorado muy positivamente el curso. Un tema recurrente resultó ser el de los criterios de evaluación, en concreto el criterio de asignación de porcentajes, pues varios de los profesores (6 de los 8 profesores-tutores) consideran que las actividades individuales deben tener un peso mayor, debido al trabajo e implicación personal que suponen para el estudiante.

En segundo lugar, en referencia a la evaluación de las actividades individuales solicitadas al alumnado (EAI), los profesores-tutores reconocen que gracias a las mismas se ha llevado a cabo una evaluación de lo más precisa, donde han podido conocer perfectamente a los alumnos a los que evaluaban: «Lo que pasa es que con un curso como este con tan pocos estudiantes, con un seguimiento tan grande, la evaluación ha sido continua, es decir, llevamos una evaluación tremendamente precisa, de quiénes eran, qué estaban haciendo, por qué no lo hacía, por qué se había retrasado…» (profesor-tutor del curso).

En cuanto a la evaluación de las actividades grupales (EAG), las opiniones se diversifican, el 60% del profesorado defiende que no se llegó a llevar a cabo un trabajo colaborativo cien por cien, pues el alumnado se limitó a repartirse las partes y luego unirlas. Otros profesores-tutores, en cambio defendían que las actividades grupales habían sido las que verdaderamente les habían dado criterios para evaluar y conocer más a los alumnos.

Por último, en referencia a la evaluación a través de la videoconferencia (EVID), con respecto al curso encontramos reticencias por parte de algún sector del profesorado (2 de los 8 profesores tutores) para utilizar la videoconferencia. «No da fiabilidad, a mí por lo menos no me la ha dado, (…) en mi caso, todo el curso genial todo muy bien, pero se lo comentaba al tutor 2, a mí la evaluación… es más, yo me quedé con dos alumnos, porque dos abandonaron, a uno se la hice por webcam y otra telefónicamente, la de telefónicamente le planteé cuestiones sobre actividades, otras acerca del tema, a ver qué había hecho y cómo lo había hecho, bueno pues imaginaros cuando no era capaz de responderme directamente se cortaba la comunicación, y le volvía a llamar y le hacía la misma pregunta. Y con la webcam exactamente lo mismo, se iba…» (profesor-tutor). Sin embargo, otro sector del profesorado (65%) sí resultó proclive al empleo de la videoconferencia como herramienta comunicativa y de evaluación, mostrando una elevada satisfacción con esta experiencia totalmente virtual que además acreditaba los conocimientos adquiridos a lo largo del mismo, insistiendo en la necesidad de realizar más entrevistas virtuales a lo largo del curso.

Finalmente, el profesorado alegó que este curso había sido el más innovador en el que había trabajado, a pesar de la necesidad de seguir trabajando ciertos aspectos pedagógicos.

d) Entrevistas a expertos. Los expertos aportaron información sobre tres de las categorías, la primera sobre la evaluación de las actividades individuales solicitadas a los alumnos (EAI), donde destacan la importancia de la evaluación continua: «Creo que una valoración continuada de los aportes tanto individuales como de grupo son esenciales en estos entornos» (experto evaluación).

En cuanto a la evaluación de las actividades grupales solicitadas a los alumnos (EAG), los expertos se centran en la necesidad de tener un buen sistema de chat para la comunicación sincrónica e incluso para la evaluación final.

Con respecto a la evaluación a través de la videoconferencia (EVID), uno de ellos se ha centrado en la fiabilidad exponiendo: «Muchas veces cuando nosotros de forma presencial le decimos al alumno que vaya haciendo un portafolio electrónico o al final va a presentar un proyecto o una memoria de investigación. Lo que sabemos es que el alumno físicamente nos lo ha dado a nosotros, pero no tenemos el mecanismo, lo tenemos cuando estamos hablando con él. Eso se puede hacer en la Red, pero hay que buscar otro criterio y es que la ratio alumno-tutor no puede ser muy elevada» (experto). Además otros matizan que: «Si estás realizando adecuadamente un curso online conoces a tus estudiantes profundamente, y sería imposible que te ‘engañaran’ en su trabajo. Lo importante es que esté bien diseñado y te aseguro que no engañan» (experto).

Por último, otro de los apuntes que realizan es la necesidad de establecer una coherencia entre el tipo de formación y el sistema de evaluación, de modo que se arbitren los medios necesarios para poder realizar una evaluación virtual y a distancia cuando la modalidad formativa sigue estos parámetros.

4. Discusión

En este estudio hemos presentado un modelo de evaluación on-line que no requiere de la presencialidad del alumnado, basándonos en una consideración constructiva del conocimiento, donde el aprendizaje puede y debe valorarse y evaluarse a lo largo del propio proceso formativo, utilizando tareas evaluables desde la perspectiva del aprendizaje individual y grupal. La evaluación de este estudio nos ha permitido establecer las siguientes conclusiones:

1) Se ha avanzado en la consecución de un modelo innovador de e-evaluación viable, eficaz y que garantiza su aplicación en enseñanza superior a distancia, que se valora como un aporte altamente beneficioso para cuantos docentes practiquen modelos de enseñanzas e-learning anclados en evaluaciones sumativas estándares, producto de procesos de enseñanzas tradicionales.

2) Se puede afirmar que la evaluación que planteamos es formativa, es decir forma parte de un proceso y permite la mejora a lo largo del mismo. Estamos por tanto en la línea argumentativa de Rodríguez e Ibarra (2011) que defienden que la e-evaluación debe ser una oportunidad de aprendizaje orientada a mejorar y promover aprendizajes significativos y que actualmente en el sistema universitario no se realiza pues se sigue poniendo el énfasis en el trabajo del profesorado antes que en el aprendizaje de los estudiantes.

3) La mayoría del alumnado considera el método de evaluación empleado como altamente motivador pues además de las diferentes técnicas y herramientas que se utilizan, se considera la evaluación como parte del proceso de enseñanza aprendizaje y no solo como una actividad que se realiza al final de curso.

4) Por el grado de satisfacción de alumnado, expertos y profesorado, los resultados avalan que se ha avanzado en varias direcciones claves para una enseñanza mucho más activa, menos la memorizadora, más centrada en tareas del alumnado y, lo que es de destacar, con un sistema de evaluación que no precisa la presencialidad. De modo que se confirman las aportaciones Sloep y Berlanga (2011), que proponen la posibilidad de crear redes de aprendizaje más allá de las fronteras entre las universidades.

5) Los resultados de este estudio hacen converger la pretendida innovación docente en la universidad con el e-learning como agente de cambio educativo. El uso de la entrevista por videoconferencia representa la innovación más significativa de nuestro estudio, si bien como método de evaluación es susceptible de mejora, pues todavía produce inseguridades en su uso como instrumento de evaluación. Sin embargo, se valora la experiencia como altamente positiva, y aunque hay que continuar avanzando para afinar la técnica, parece que estamos en el buen camino. De cualquier modo, tal y como se ha sugerido (Blázquez, 2004) debemos utilizar estas tecnologías para innovar y no para reproducir modelos tradicionales poco efectivos, abusando de los recursos sincrónicos (como videoconferencias) en desmedro de los asincrónicos (página web, e-mail, foros de discusión, etc.).

6) El modelo de evaluación de los aprendizajes ensayado facilita la existencia de actividades universitarias regladas para estudiantes imposibilitados geográficamente de acceder a pruebas finales (exámenes) presenciales, con lo que se abre un enorme mercado formativo a nuestras universidades, especialmente a países latinoamericanos.

7) Como señala Solectic (2000), la especificidad de los materiales didácticos requiere que se ubiquen una serie de actividades que ayuden a que los estudiantes pongan en juego sus recursos, estrategias y habilidades y participen en la construcción del conocimiento. Éste, desde el principio, fue nuestro objetivo en relación con las actividades individuales y como hemos ido comprobando así lo han percibido los estudiantes, ya que las actividades individuales son las más valoradas como estandarte de evaluación continua.

8) En general la implementación de esta modalidad de evaluación no presencial ha sido positiva, especialmente al trabajar centrados en una evaluación continua mediante las actividades, trabajos y entrevistas (mediante videoconferencia), así como la existencia de un modelo tutorial, que garantiza un seguimiento del proceso de aprendizaje del estudiante, potenciado por una ratio de fácil gestión, cinco alumnos por tutor. A su vez, este factor está reforzado por la singularidad de la experiencia piloto, donde el profesorado fue seleccionado por su alta implicación y motivación.

9) De cualquier modo siempre hay propuestas de mejora a implementar referentes a ligeros cambios relacionados con la flexibilidad en las actividades y la valoración singular de las actividades colaborativas, que han de ir más allá del mero reparto de tareas. Asimismo, se debe potenciar el incremento en el número de entrevistas, lo que a su vez proporcionará mayor seguridad al profesorado en el manejo de la tecnología de Aulas Virtuales Síncronas.

10) Concluimos señalando que, partiendo del criterio cualitativo de transferencia, animamos a la comunidad docente con escenarios similares a implementar procesos de e-evaluación de los aprendizajes a seguir los principios presentados en el estudio.

Referencias

Alonso, L. & Blázquez, F. (2009). Are the Functions of Teachers in E-learning and Face-to-Face Learning Environments Really Different? Educational Technology & Society, 12(4), 331-343.

Birnbaum, B.W. (2001). Foundations and Practices in the Use of Distance Education. Lewiston, NY: Mellen Press.

Blázquez, F. & Alonso, L. (2006). Aportaciones para la evaluación on-line. Tarraconensis, Edició Especial, 207-228.

Blázquez, F. (2004). Nuevas tecnologías y cambio educativo. In F. Salvador, J.L. Rodríguez & A. Bolívar (Eds.), Diccionario En ciclopédico de Didáctica (pp.345-353). Málaga: Aljibe.

Cabero, J. & Prendes, M.P. (2009). La videoconferencia. Apli caciones a los ámbitos educativo y empresarial. Sevilla: MAD.

Cubo, S., Alonso, L., Arias, J., Gutiérrez, P., Reis, A. & Yuste, R. (2009). Modelización didáctica-pedagógica, metodológica y tecnológica de las aulas virtuales: implantación en la Universidad de Extremadura. In J. Valverde (Ed.), Buenas prácticas educativas con TIC. Cáceres: SPUEX.

Forster, M. & Washington, E. (2000). A Model for Developing and Managing Distance Education Programs Using Interactive Video Technology. Journal of Social Work Education, 36(1), 147-59.

Gikandi, J.W., Morrow, D. & Davis, N.E. (2011). Online Formative Assessment in Higher Education: A Review of the literature. Computers & Education 57, 2.333-2.351.

Mehrotra, C.M., Hollister, C.D. & McGahey, L. (2001). Distance Learning: Principles for Effective Design, Delivery and Evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Moore, M., Lockee, B. & Burton, J. (2002). Measuring Success: Evaluation Strategies for Distance Education. Educause Quarterly, 25(1), 20-26.

Oosterhoff, A., Conrad, R.M. & Ely, D.P. (2008). Assessing Learners Online. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Peñalosa, E. (2010). Evaluación de los aprendizajes y estudio de la interactividad en entornos en línea: un modelo para la investigación. RIED, 13 (1), 17-38.

Potts, M.K. & Hagan, C.B. (2000). Going the Distance: Using Systems Theory to Design, Implement, and Evaluate a Distance Edu cation Program. Journal of Social Work Education, 36(1), 131-145

Rockwell, K., Furgason, J. & Marx, D.B. (2000). Research and Evaluation Needs for Distance Education: A Delphi Study. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, III.

Rodríguez, G. & Ibarra, M.S. (2011). e-Evaluación orientada al e-aprendizaje estratégico en educación superior. Madrid: Narcea.

Rodríguez, G., Gil, J. & García, E. (1999). Metodología de la investigación cualitativa. Málaga: Aljibe.

Sancho, J. (2011). Entrevista a Juana María Sancho Gil. En Edu cación y Tecnologías. Las voces de los expertos. Buenos Aires: An ses.

Serrano, J. & Cebrián, M. (2011). Study of the Impact on Student Learning Using the eRubric Tool and Peer Assessment. In Varios: Education in a Technological World: Communicating Current and Emerging Research and technological efforts. EDIT. Formatex Research Center (In press).

Sloep, P. & Berlanga, A. (2011). Redes de aprendizaje, aprendizaje en red. Comunicar, 37, XIX, 55-64. (DOI: 10.3916/C37-2011-02-05).

Solectic, A. (2000). La producción de materiales escritos en los programas de educación a distancia: problemas y desafíos. In L. Litwin (2000), La educación a distancia. Temas para el debate en una nueva agenda educativa. España: Amorrortu.

Stufflebeam, D.L. (2000). Guidelines for Developing Evaluation Checklists. (www.wmich.edu/evalctr/checklists) (15-12-2011).

Wentling, T. & Johnson, S. (1999). The Design and Develop ment of an Evaluation System for Online Instruction. www.universia.pr/cultura/videoconferencia.jsp. (30-09-2011).

Weschke, B. & Canipe, S. (2010). The Faculty Evaluation Process: The First Step in Fostering Professional Development in an Online University. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 7(1), 45-58.

Document information

Published on 30/09/12

Accepted on 30/09/12

Submitted on 30/09/12

Volume 20, Issue 2, 2012

DOI: 10.3916/C39-2012-03-06

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?