Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Although we live in a global society, educators face many challenges in finding meaningful ways to connect students to people of other cultures. This paper offers a case study of a collaboration between teachers in the US and Turkey, where 7th grade students interacted with each other via online social media as a means to promote cultural understanding. In a close analysis of a single learning activity, we found that children had opportunities to share ideas informally through social media, using their digital voices to share meaning using online writing, posting of images and hyperlinks. This study found that students valued the opportunity to develop relationships with each other and generally engaged in sharing their common interests in Hollywood movies, actors, celebrities, videogames and television shows. However, not all teachers valued the use of popular culture as a means to find common ground. Indeed, teachers had widely differing perspectives of the value of this activity. Through informal communication about popular culture in a «Getting to Know You» activity, students themselves discovered that their common ground knowledge tended to be US-centric, as American students lacked access to Turkish popular culture. However, the learning activity enabled students themselves to recognize asymmetrical power dynamics that exist in global media culture.

1. Introduction

Undoubtedly, Web 2.0 technologies enable learners to travel across time and space. In the past two decades, all around the world, most general accounts of education have emphasized that schooling needs to take account of the multiple channels of communication and media now in popular use (Lee, Lau, Carbo, & Gendina, 2012; New London Group, 1996). In the context of English language arts education, in particular, the traditional print-based concepts of literacy, text, and meaning are becoming strategically displaced as teachers and school leaders begin to recognize that people now use language, images, sound, and multimedia for everyday purposes of expression and communication and that the relevant associated competencies must be part of elementary and secondary education (Hobbs, 2010; Tuzel, 2013a; Tuzel, 2013b). Undoubtedly, literacy today is “situationally specific” and “dynamically changing” (Coiro, Knobel, Lankshear, & Leu, 2008: 5) all around the world. In Turkey, for example, there has been a significant investment in providing access to digital technology in elementary and secondary schools to support teaching and learning (Unal & Ozturk, 2012).

In this paper, we present a case study of an international collaboration involving middle school teachers from two countries, working in collaboration with the authors to design and implement an intercultural learning experience that brings together Turkish and American students in Grade 7 using digital and social media. The goal of the initiative was designed to help students (a) develop confidence in expressing themselves with people using online social media, (b) promote cultural knowledge and critical thinking about media and popular culture, and (c) advance global understanding between middle-school students in Turkey and the United States. By linking together subject-area instruction in social studies and foreign language education in English, this initiative explored how to use the power of social media for sustained social and cultural interaction over a period of six weeks. Evidence from this case study demonstrates that the use of digital and social media to activate children’s voice requires sensitivity to differential perceptions of the value of popular culture among teachers as well as robust appreciation of the asymmetries and inequalities still inherent in global information and entertainment flows.

1.1. Cross cultural learning goes digital

Globalization and digital technology have combined to open up cultures to a fast-paced world of change and educators have been inspired to bring the world into their classrooms, enabling students to have a civic voice (Hobbs, 2010; Stornaiuolo, DiZio, & Helming, 2013). Although traditional global pen pal programs have been in place in the USA since the 1920s (Hill, 2012), in the years after the 9/11 terrorist attack, some educators began exploring with how to promote student voice and global understanding to bring together Americans and peoples of the Middle East through cross-cultural communication learning experiences. To increase students' experiences with people different from themselves, such projects may include work with international students from local universities, immigrant organizations in the community, service learning projects, exchanges through e-mail or videos, and taking students overseas (Merryfield, 2002). In these projects, teachers may ask students to use email or online communication to develop keyboard skills, share poetry, report writing, and journal writing – all fundamental dimensions of literacy education.

The rise of social media has made it easier for teachers and students from diverse cultures to meet and work together. Teachers may emphasize cross-cultural learning experiences as a transformative way to teach “children to care and make a difference in the world while simultaneously trying to make a difference in the world” (Aldridge & Goldman, 2007: 78). Such efforts can be useful not only to students, but to teachers as well. Cross-cultural projects may not only promote confidence in self-expression, but may also promote the development of reflective-synthetic knowledge, a concept articulated by Kincheloe (2004) who described it as a process that advances student voice while revealing to both teachers and students the often hidden assumptions about the nature of knowledge itself.

1.2. Media and digital literacy for global education

The term digital literacy has begun to emerge to reflect the broad constellation of practices that are needed to thrive online (Rheingold 2012; Gilster, 1999). Most conceptualizations focus on the pragmatic skills associated with the use of digital tools and texts. As Greenhow, Robelia and Hughes (2011: 250) note, “Digital literacy includes knowing how and when to use which technologies and knowing which forms and functions are most appropriate for one’s purposes”. But other definitions explicitly conceptualize digital literacy as a broader literacy competency, building on the tradition of media literacy and including the ability of learners to access, analyze, create, reflect and take action using the power of communication and information to make a difference in the world (Hobbs, 2010).

Even more broadly, across Europe, Asia, South America and Africa, the term media and information literacy (MIL) has been recognized as a means to foster more equitable access to information and knowledge; promote freedom of expression; advance independent and pluralistic media systems; and improve the quality of education. By empowering “citizens to understand the functions of media and other information providers, to critically evaluate their content, and to make informed decisions as users and producer of information and media content”, media and information literacy, while sometimes seen as separate and distinct fields, are conceptualized as a combined set of competencies necessary for life and work today (UNESCO, 2013: 16).

Only a few school-based projects have aimed to advance learner voice by connecting young people from across communities to promote cultural understanding through media literacy. For example, elementary educators in the USA used a variety of media literacy practices, including viewing and discussion, critical analysis of images, film/media production and interaction with young people from Kuwait as a way for children to gain knowledge of the people and culture of the region (Hobbs & al., 2011a; Hobbs & al., 2011b). By talking about how news, media and popular culture embed stereotypes about culture and values, children as young as eight and nine were able to recognize that media messages (including photographs, movies, websites and books) can be critically interrogated. Media analysis and production activities can help build critical thinking and activate student voice while simultaneously advancing knowledge and language skill development (Hobbs, 2007; Tuzel, 2012a; Tuzel, 2012b). For example, during the process of an action research project, a Turkish teacher who used media literacy education activities in language arts, using popular culture texts (film, TV serial, magazine etc.) for learning, found increases in students’ levels of media literacy, critical thinking and language skills; in addition to expanding textual awareness, this learning activity shifted learners’ conceptualization of literacy from the alphabetic to the multimodal (Tuzel, 2012a).

Social media and other virtual environments have the potential to play a role in terms of cultivating intellectual curiosity and advancing civic voice in conjunction with learning about people and cultures around the world. Intergroup dialogue (generally involving young adults) has been shown to be effective in combating negative stereotypes and prejudices about countries and cultures, promoting tolerance and intercultural acceptance (Hurtado, 2005) and a growing number of organizations are bringing global dialogues to college students using digital media (Soliya, 2014). However, historical asymmetries of status and power between groups may affect the quality of learning for the majority/empowered and minority/disempowered group members (Cikara, Bruneau, & Saxe, 2011).

Accordingly, based on this review of the literature, we report the results of a single school-based instructional activity that aimed to activate student voice and promote global awareness. In exploratory research, we examine these research questions: How did US and Turkish learners and teachers experience the cross-cultural communication project? What were the affordances and limitations of using a social media exchange activity for activating student voice and building cross-cultural understanding?

2. Methods

This section briefly summarizes the case study method we employed to explore the use of a private online social network to facilitate co-learning between middle-school teachers and students in the United States and Turkey. The project was designed to enable American and Turkish students to (a) develop confidence in expressing themselves with people using online social media, (b) promote cultural knowledge and critical thinking about media and popular culture, and (c) advance global cultural understanding between middle-school students in Turkey and the United States. By linking together subject-area instruction in social studies and foreign language education in English, this initiative helped both teachers and learners explore how to use the power of an online social network for sustained social and cultural interaction.

A six-week online cross-cultural learning experience program using a private online social network was developed and implemented by researchers in collaboration with The George School faculty (a pseudonym for a private school in Northern California) and the faculty of The Blossom School (a pseudonym for a private school in Western Turkey). Close analysis of one lesson provided us with an opportunity to gather exploratory data about the way teachers and students perceive the value of using one’s voice to encounter people from another culture and learn about their lives, experiences and interests.

A total of 84 children between the ages of 12 and 14 participated in the project. A middle-school history teacher at George School and his 43 Grade 7 students worked with five English teachers at Blossom School in Turkey, along with two M.A. students in Education, and 41 Grade 7 Turkish students enrolled in an English class.

2.1. Research process

In this study, interviews, documents, observations, video recordings and students’ work samples were used to analyze the quality of the learning experience. The researchers conducted interviews with both teachers and students before, during and after the implementation to record the thoughts and opinions of the teachers and students. The researchers paid special attention to changes in students’ comments about the other culture. The authors also focused on the reasons for the posts and interactions of the students. Therefore, the authors tried to make an extensive analysis of the causes of events and situations (Ellet, 2007:19). Data triangulation provides support for reliability as different data collection tools including interviews, observation and written and visual document analysis in the social network were used. In both schools, students participated in the project and performed the tasks requested of them during the implementation on a voluntary basis.

2.2. Curriculum development

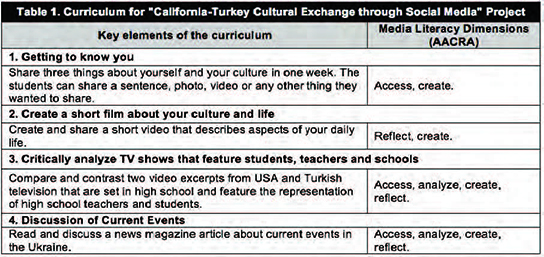

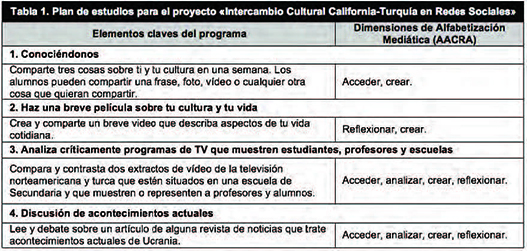

Using the model of a university-school partnership, Turkish and American middle-school teachers worked collaboratively with researchers to prepare four lesson plans based on the core principles of media literacy (NAMLE, 2008). University school partnerships provide important supports to educators who aim to explore innovative instructional practices in digital and media literacy education (Moore, 2013). The development of four lesson plans enabled students to share information about the culture and the values of their family and community, learn more about the history, cultural practices and social norms of these two cultures, and critically analyze popular entertainment media representations of culture and values. Table 1 provides a summary of the complete curriculum as aligned with elements from the five-part AACRA definition of digital and media literacy (Hobbs, 2010). Researchers and teachers were careful to include a balance of learning experiences that encouraged students to access, analyze, create, and reflect on information and ideas in the context of the global co-learning experience. Before implementation of the curriculum, the researchers held four online planning meetings with both Turkish and American teachers where a timetable and learning process was established and the students were pre-registered in the social media platform.

3. Findings

In order to focus on how middle-school students developed confidence in expressing themselves using online social media by finding common ground with peers from halfway around the world, we describe and analyze the implementation of only the first lesson. In a close analysis the “Getting to Know You” learning activity, children had opportunities to share ideas informally through social media, using their digital voices to share meaning using online writing and posting of images. While students valued the opportunity to develop relationships with each other by sharing their common interests in Hollywood movies, actors, celebrities, videogames and television shows, teachers had widely differing perspectives of the value of this activity. Through informal communication about popular culture, students themselves discovered that their common ground knowledge tended to be US-centric, as American students lacked access to Turkish popular culture. The learning activity foregrounded the asymmetrical power dynamics that exist in global media culture where information and entertainment flows are primarily one-way in nature and perceptions about the value of popular culture are contested. As is appropriate with case study research, we interweave interpretation with narrative description.

3.1. Learning to talk across cultures

• Lesson 1, “Getting to Know You”, was an ice breaker activity, aimed to introduce students to each other and help them develop confidence in interacting with others as they gained familiarity with the Ning social media platform. Through this activity, students began to discover their similarities and differences. Teachers asked their students to share three things about themselves and their culture in one week; they did not limit students about the structure, length or content of their posts. The 84 participating Turkish and American students could share a sentence, photo, video or any other thing they wanted to share. In order to support students in the process of relationship formation, students were assigned to one of seven groups (with six students in each group). The small group structure made it easier for students to read and follow each other’s posts and respond to each other personally. Students shared 391 posts during the implementation of Lesson 1, for an average of 4.6 posts per student during the week. Some of these posts were questions designed to engage another student while others were just aimed at presenting themselves and their own culture.

Students demonstrated significant interest in participating in this activity. However, in the first few days, they sometimes had difficulty responding to questions or commenting on each other’s posts. Two main reasons seem evident: most importantly, Turkish students were expressing themselves in a foreign language while USA students were communicating in their native language. Also, the ten-hour time difference between The Blossom School and The George School made it initially difficult for students to understand how to follow each other’s comments. It took a few days for students to understand how to navigate and read the posts as Turkish and American students each posted comments at different times of the day (at school) and the evening (at home).

The novelty of “talking” across space and time was fascinating to many young students. Early on, a student from The George School noted:

• “USA Student 1: This is kind of a random comment, but I think that it is kind of mindblowing when you think about the fact that two people can be sitting at a computer, typing on the same forum, but for one person it is the early morning (it is 10:40 in the morning as I type this) and for the other it is late at night (I think it is 8:40 at night in Turkey)”.

Students enjoyed the opportunity to interact socially and share information about their own culture. In general, students preferred to write simple sentences. However, students also uploaded photos and videos of themselves, friends and family, favorite places and food. Some students shared links to music, movie series and computer games they loved, asked what their peers thought about them, or responded to similar questions. The researchers observed that the students visited their profiles and the discussion board many times during the week when Lesson 1 was being implemented. Student behavior reflects Stern's (2008) observation about the authentic personal pleasure young adolescents experience using social media for self-presentation and peer validation.

Analysis of the 391 posts that students shared during this activity reveals a wide range of subjects. Some of these subjects are about ordinary elements of daily life, community and environment, favorite activities, school work, information about their parents and siblings and their relationships with them, countries they visited and favorite foods. The students were very open to interaction and curious about each other’s lives. They wanted to inform the students with whom they were talking and elaborate on the subjects of their conversations. Notice the clear evidence of relationship development displayed in the exchange below: “USA Student 2: My brother is 16. How old is your brother? Turkish Student 1: My brother is 8 years old. He is younger than me. I’ve got dogs too. I’ve got 2 dogs. One of my dog [sic] have 3 puppy. They are very sweet I can share their photo maybe. What about your dogs? Can you share their photos?”

The activity clearly enabled students to build trust and respect and it may also have prevented students from approaching each other based on stereotypes, helping them to see each other as individuals. Within a day or two, the American students, who thought that they were interacting with Middle Eastern people, realized that the students with whom they were talking were individuals with families, personal lives and hobbies. They stopped seeing the students at the other school as a group of foreigners and started to see them as individuals. It was certainly the same for Turkish students, too, who may have had stereotypes about American culture.

3.2. Finding common ground through media and popular culture

More than two-thirds of all the social interactions during Lesson 1 focused on the discovery of common ground through shared interests in mass media and popular culture. Posts included information and opinions about American mass media, as students discussed a variety of actors, movies, TV series video games, popular books, music and similar subjects. In these dialogues, many students discovered that they were interested in the same types of popular culture products as the students in the other country. They were excited by the discovery of their common interests in music, fashion, gaming and movies.

Thanks to these dialogues, children realized that although they lived in different parts of the world, they admired the same singers and actors, watched the same movies and TV series and played the same computer games in their free time. They were excited to recognize that popular culture was a kind of common global culture. The informal quality of language and expression used on the social network, plus the amount of conversation about media and popular culture, was somewhat unnerving to Turkish teachers of English language who were unfamiliar with the pedagogy of media literacy education. To illustrate this point, consider this exchange between Turkish and American teens:

• Turkish Student 3: Do you know Mythbusters that show is really good.

• USA Student 4: OMG! That show is amazing!

• USAStudent 6: Yeah I used to watch that show and want to try doing the things they did. It was a little dangerous though.

• Turkish Student 5: Yea, they blow up everything: D

• USA Student 3: Hahahahaha, Do you know the show “Top Gear”?

• Turkish Student 3: Yea, It’s an American show, right?

• USA Student 3: It’s actually from the UK but there is an American version and lots of other versions although the original one is from the UK

• USA Student 6: No, my parents won’t let me :(

During this activity, students developed confidence in expressing their voice by sending posts, interacting and asking questions. While most used grammatically correct English, others used some of the linguistic conventions of text messaging, including emoticons and excessive punctuation in their informal writing. Students discovered that they had valuable knowledge that was of interest to others. In particular, American students were surprised to learn that Turkish students were familiar with their favorite TV shows, videogames, movies and music.

3.3. Conflicting values about popular culture among teachers

Teachers had differing perceptions about the value of Lesson 1, which encouraged children to use social media as an informal sharing opportunity to encounter each other as human beings. Mr. Herbert, from George School, was very happy that his students started to learn about the personal interests of children who were growing up in Turkey. He was pleased that students could activate their out-of-school knowledge about sports, media, music and family life in interacting with Turkish middle-school students through social media. Because students know so little about daily life in Turkey, Mr. Herbert believed that his students were learning from their Turkish peers to “question the prejudices and stereotypes conveyed by the American mass media” about the people and cultures of the Middle East. At the end of the first week of the activity, he noticed students' attitude shifts during classroom discussion and he focused on the changes he observed in the prejudices of the students. He described how students started to question their knowledge about the Middle East and Turkey.

By contrast, teachers at the Blossom School in Turkey had a different perspective about the value of Lesson 1. Turkish teachers had hoped that the project would be an opportunity to promote Turkish culture and values. For this reason, they were unhappy that in Lesson 1, students were mostly discussing American popular culture. Teachers encouraged their students to talk about elements of the Turkish culture such as traditional Turkish coffee, carpets, food, geography, history and hospitality. Despite these admonitions, the Turkish students kept on posting comments about American mass media and pop culture. In an interview, Mr. Yaman expressed this concern, “In this project, we mainly wanted the students to promote their lifestyle and culture to the American students. I believe that they should focus on Turkish culture, but they mostly talked about American movies and celebrities”. One of the Turkish graduate students who helped the Turkish teachers with this project said, “I witnessed that teachers were uncomfortable with students’ using social media and creating video, especially when such activity led to the production of popular culture texts that threatened national school-sanctioned curricula and the teachers’ authority".

These findings are aligned with work by Moore (2013) who reports various sources of anxiety among elementary and secondary teachers concerning the inclusion of popular culture in the classroom. Although informal learning in formal educational contexts can be highly valuable, this study illustrates that experiences with using one’s voice in a social media network may “shape young people's knowledge construction in unexpected ways”, inspiring teachers to “structure informal practices that were not perceived to hold a legitimate place in formal education” (Greenhow & Lewin, 2015: 18).

3.4. Discovering asymmetries in access to media and popular culture

Turkish students were both excited to discover their common interests and disappointed to see that the American students had such limited knowledge about Turkish culture and media. Some Turkish students asked their American peers about their familiarity with particular Turkish actors and musicians. Turkish children were curious if American students were familiar with the best and most famous Turkish movies and TV series. However, they did not get any responses. Because of the historical development, size and scale of the USA media industry, Americans have less access to global popular culture than people from other nations (Crothers, 2013). For example, only seven cities in the United States carry the television network Al Jazeera America (Cassara, 2014).

When the Turkish children were interviewed, many revealed their disappointment that the conversations about popular culture were a “one-way street” with an exclusive focus on American media from Hollywood and Silicon Valley. The asymmetry of knowledge about popular culture was at times frustrating to the Turkish students. For example, one Turkish student said, “We know about the American TV series, movies and singers. Justin Bieber is very famous and handsome both for them and for us. But there are also singers in our country who are as handsome and talented as Justin Bieber, yet they do not know about them”.

Over time, American children also grew more aware of the asymmetry problem, and by the end of the six-week curriculum, both groups had increased their awareness of how some asymmetries in their online relationship that were the result of structural, economic and political differences in the global media system. Mr. Herbert, the American teacher, was supportive of the children's discovery of the problem of asymmetrical access. According to the teacher, for some students, it was a shock to learn that, despite their privileged status as American school children enrolled in a private school, they missed having access to global information and entertainment coming from Turkey. It was an eye-opening experience that introduced children to the intersection of individual and institutional dynamics at work in relation to cultural imperialism (Schiller, 1969) where the pursuit of commercial interests by US-based transnational corporations undermined the cultural autonomy of countries around the world. At the end of the learning experience, one American student wrote, “I learned that the world outside of America is actually pretty similar to ours, and that different people view different things in very different ways. But I noticed that I have no idea about Turkish cultures and life. I learned a lot from this, and it was really great!”.

Media globalization has created new kinds of inequalities between nations in relation to media production and global distribution that reflect wider political and economic problems of dependency (Boyd-Barrett, 1998). The rise of media globalization, which emerged at the beginning of the 20th century from the global export of Hollywood film, has now expanded to include music, video games, advertising, merchandising and celebrity culture. We did not expect to find that, as the use of a private online social network empowered student voice, it also enabled students to develop a deeper understanding of the global flows of entertainment and information that shape how cultural products are exchanged and experienced. We did not expect that young people would learn to use their digital voices in interacting with foreign peers by finding common ground in the pleasures of movies, television shows, videogames, and popular music. We did not expect for this practice to be controversial with classroom teachers. Through a close analysis of an activity where young teens interacted informally with each other to find common ground, this study is the first to demonstrate that, through interacting with global peers, even young teenagers can begin to recognize the nature of one-way information flows that are driven by the global media system where USA music, movies and videogames dominate.

4. Discussion and conclusions

The opportunity to talk across the limitations of time and space can be transformative. This paper has offered a case study of a collaboration between teachers in the US and Turkey, where 7th grade students interacted with each other informally via online social media as a means to activate student voice and promote cultural understanding. In the context of this middle-school global learning experience, children had opportunities to share ideas through social media, using online writing, posting of images, and the creation of short films, posters and electronic comic books. We have shown that there is educational value in the informal use of social media with young adolescents, whose in-school use of social media in the context of social studies and foreign language education has not yet been researched widely. For young adolescents, it may be empowering to discover that people from far-off lands have families, pets, friends, and all the ordinary joys, trials and tribulations of growing up. The opportunity to use social media for ordinary conversation –finding common ground– may have benefits that include but go far beyond the mastery of English grammar and usage.

Digital media are useful for crossing borders of all kinds. While students valued the opportunity to develop relationships with each other by sharing their common interests in Hollywood movies, actors, celebrities, videogames and television shows, teachers had widely differing perspectives of the value of this activity. While we anticipated that this project would enable us to explore how middle-school students navigate geographic and cultural borders, this research demonstrates that teacher attitudes about popular culture represent another key fault line that may either support, deepen or limit the value of digital literacy instructional practices, particularly when social media activities are used by students to engage in authentic cross-cultural dialogue. More research will be needed to fully understand the conditions under which students' use of social media to share informal knowledge may inadvertently become a kind of power wedge between students and adults.

This study has implications for the professional development of educators with interests in student voice. When students are able to freely express themselves, they will inevitably reveal their authentic and deeply-felt attachments to mass media and popular culture. Teachers who may be ambivalent, conflicted or even hostile to popular culture in the classroom and professional development must address this issue in the context of digital learning. For this reason, Hagood, Alvermann and Heron-Hruby (2010) have suggested that teachers who participate in carefully designed long-term professional development programs should become comfortable in integrating popular culture texts into their curricula. According to Alvermann (2012: 218), “that such identity constructions frequently become visible through films, music, rap lyrics, and so on is yet another reason why popular culture texts have a place in a school’s curriculum and its classrooms”. Of course, there may be valid reasons for why some students may not wish to explore their identities through popular culture texts introduced in the school curriculum, especially if (however well intended), the classroom activities colonize or trivialize young people’s interests (Burn, Buckingham, Parry, & Powell, 2010).

But because educators have a love-hate relationship with mass media, popular culture and digital media, these attitudes inevitably come into play when digital technologies are used in education. We recognize the powerful opportunity that cross-cultural projects may play in promoting a reflective stance among teachers, who may discover the particularities of their values through collaborative projects like the one we describe in this paper. It may be that hidden assumptions about the nature of knowledge itself, including the sometimes rigid and hierarchical positioning of “high” and “low” culture, can be revealed through activities that enable students to bring their lived experience of popular culture and daily life into the classroom (Hobbs & Moore, 2013). In the design and development of instructional pedagogies that use social media to promote cross-cultural dialogue, teachers may benefit from structured opportunities to reflect on how their attitudes about mass media and popular culture may shape their curriculum choices and use of digital texts, tools and technologies.

References

Aldridge, J., & Goldman, R. (2007). Moving toward Transformation: Teaching and Learning in Inclusive Classrooms. Birmingham, AL: Seacoast Publishing.

Alvermann, D.E. (2012). Is there a Place for Popular Culture in Curriculum and Classroom Instruction? [The Point Position] (Volume 2, pp. 214-220, 227-228). In A.J. Eakle (Ed.), Curriculum and Instruction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Boyd-Barrett, O. (1998). Media Imperialism Reformulated (pp. 157-177). In D. Thussu (Ed.), Electronic Empires: Global Media and Local Resistance. London: Arnold.

Burn, A., Buckingham, D., Parry, B., & Powell, M. (2010). Minding the Gaps: Teachers’ Cultures, Students’ Cultures (pp. 183-201). In D.E. Alvermann (Ed.), Adolescents’ Online Literacies: Connecting Classrooms, Digital Media, and Popular Culture. New York: Peter Lang.

Cassara, M. (2014). Al Jazeera Remaps Global News Flows. In S. Robert, P. Fortner, & M. Fackler (Eds.), The Handbook of Media and Mass Communication Theory. New York: Wiley Online.

Cikara, M., Bruneau, E., & Saxe, R. (2011). Us and Them: Intergroup Failures of Empathy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(3), 149-153.

Coiro, J., Knobel, M., Lankshear, C., & Leu, D.J. (2008). Central Issues in New Literacies and New Literacies Research (pp. 1-22). In J. Coiro, M. Knobel, C. Lankshear, & D.J. Leu. (Eds.), The Handbook of Research in New Literacies. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Crothers, L. (2013). Globalization and American Popular Culture. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Ellet, W. (2007). The Case Study Handbook. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Gilster, D. (1999). Digital Literacy. New York: Wiley.

Greenhow, C., & Lewin, C. (2015). Social Media and Education: Reconceptualizing the Boundaries of Formal and Informal Learning. Learning, Media and Technology, 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2015.1064954

Greenhow, C., Robelia, B., & Hughes, J. (2011). Web 2.0 and Classroom Research: What Path should We take Now? Educational Researcher, 38(4), 246-259.

Hagood, M., Alvermann, D.E., & Heron-Hruby, A. (2010). Bring it to Class: Unpacking Pop Culture in Literacy Learning. New York: Teachers College Press.

Hill, M. (2013). International Pen Pals Engaging in a Transformational Early Childhood Project. Doctoral dissertation, University of Alabama, Birmingham. (http://goo.gl/AdhHc4) (2016-08-01).

Hobbs, R. (2007). Reading theMedia : Media Literacy in High School English. New York: Teachers College Press.

Hobbs, R. (2010). Digital and Media Literacy: Connecting Classroom and Culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin/Sage.

Hobbs, R., & Moore, D.C. (2013). Discovering Media Literacy: Digital Media and Popular Culture in Elementary School. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin/Sage.

Hobbs, R., Cabral, N., Ebrahimi, A., Yoon, J., & Al-Humaidan, R. (2011b). Field Based Teacher Education in e-Elementary Media Literacy as a Means to Promote Global Understanding. Action in Teacher Education, 33, 144-156.

Hobbs, R., Yoon, J., Al-Humaidan, R. Ebrahimi, A., & Cabral, N. (2011a). Online Digital Media in Elementary School. Journal of Middle East Media, 7, 1-23.

Hurtado, S. (2005). The Next Generation of Diversity and Intergroup Relations Research. Journal of Social Issues, 61(3), 595-610. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00422.x

Kincheloe, J. (2004). The Knowledges of Teacher Education: Developing a Critical Complex Epistemology. Teacher Education Quarterly 31(1), 49-66.

Lee, A., Lau, J., Carbo, T., & Gendina, N. (2012). Conceptual Relationship of Information Literacy and Media Literacy in Knowledge Societies. World Summit on the Information Society. UNESCO Media and Information Literacy. (http://bit.ly/1LgJLbL) (2016-09-12).

Merryfield, M. (2002). The Difference a Global Educator can Make. Educational Leadership 60(2), 18-21.

Moore, D.C. (2011). Asking Questions First: Navigating Popular Culture and Transgression in an Inquiry-based Media Literacy Classroom. Action in Teacher Education 33, 219-230.

Moore, D.C. (2013). Bringing the World to School: Integrating News and Media Literacy in Elementary Classrooms. Journal of Media Literacy Education 5(1), 326-336.

National Association for Media Literacy Education (2008). Core Principles of Media Literacy Education. (http://goo.gl/alhkrZ) (2015-08-11).

New London Group (1996). A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66, 60-92.

Rheingold, H. (2012). Net Smart: How to Thrive Online. New York: Basic.

Schiller, H. (1969). Mass Communication and American Empire. New York: M. Kelley Publishers.

Soliya (Ed.) (2014). What we do. (www.soliya.net) (2015-08-15).

Stern, S. (2008). Producing Sites, Exploring Identities: Youth Online Authorship. In D. Buckingham (Ed.), Youth, Identity and Digital Media (pp. 95-117). J.D. and C.T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Stornaiuolo, A., DiZio, J.K., & Helming, E.A. (2013). Expanding Community: Youth, Social Networking and Schools. [Desarrollando la comunidad: jóvenes, redes sociales y escuelas]. Comunicar, 40, 79-87. https://doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-02-08

Tuzel, S. (2012a). Ilkogretim ikinci kademe Turkce derslerinde medya okuryazarligi: Bir Eylem Arastirmasi. PhD Dissertation, Unpublished. Canakkale: Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University.

Tuzel, S. (2012b). Integration of Media Literacy Education with Turkish Courses. Mustafa Kemal University Journal of Social Sciences Institute, 9(18), 81-96.

Tuzel, S. (2013a). Integrating Multimodal Literacy Instruction into Turkish Language Teacher Education: An Action Research. Anthropologist 16(3), 619-630.

Tuzel, S. (2013b). The Analysis of Language Arts Curriculum in England, Canada, the USA and Australia Regarding Media Literacy and their Applicability to Turkish Language Teaching. Educational Science: Theory & Practice, 13(4), 2291-2316.

Unal, S., & Ozturk, I. (2012). Barriers to ITC Integration into Teachers’ Classroom Practices: Lessons from a Case Study on Social Studies Teachers in Turkey. World Applied Sciences Journal, 18(7), 939-944.

UNESCO. (2013). Media and Information Literacy: Policy and Strategy Guidelines. (https://goo.gl/ZPhgWk) (2015-08-11).

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Si bien vivimos en una sociedad global, los educadores se enfrentan a numerosos desafíos a la hora de hallar formas significativas de conectar a los alumnos con gente de otras culturas. Este artículo muestra un caso práctico de colaboración entre profesores de los Estados Unidos y Turquía, en el que alumnos de séptimo grado interactuaron entre sí a través de las redes sociales con el fin de promover la comprensión cultural. Al analizar una única actividad de aprendizaje hallamos que los alumnos tenían la oportunidad de compartir ideas informalmente a través de las redes sociales, usando su voz digital para compartir significados mediante la escritura online, publicación de imágenes e hipervínculos. Este estudio halló que los alumnos valoraban la oportunidad de relacionarse entre sí y tendían a compartir su interés común en películas de Hollywood, actores, famosos, videojuegos y programas de televisión. Sin embargo, no todos los profesores valoraban el uso de la cultura popular como medio para la búsqueda de puntos en común. En efecto, los profesores tenían perspectivas muy distintas sobre el valor de esta actividad. Mediante la comunicación informal en torno a la cultura popular en una actividad de conocimiento mutuo, los propios alumnos descubrieron que sus conocimientos en común tendían a estar centrados en los Estados Unidos, en tanto en cuanto los alumnos americanos no tenían acceso a la cultura popular turca. Sin embargo, la actividad de aprendizaje permitió a los propios alumnos reconocer las dinámicas de poder asimétrico que existen en la cultura mediática global.

1. Introducción

Sin duda, las tecnologías Web 2.0 permiten a los estudiantes viajar en el tiempo y en el espacio. En las dos últimas décadas, las experiencias educativas por todo el mundo han enfatizado el hecho de que la escolaridad debe tener en cuenta los múltiples canales y medios de comunicación que hoy son de uso popular (Lee, Lau, Carbo, & Gendina, 2012; New London Group, 1996). En el contexto de la educación artística en inglés en particular, los conceptos tradicionales de publicación impresa de alfabetización, texto y significado se están viendo estratégicamente desplazados a medida que los profesores y líderes escolares comienzan a ver que hoy las personas usan el lenguaje, imágenes, sonido y multimedia para fines de comunicación y expresión cotidiana y que las competencias relevantes asociadas deben ser parte de la Educación Primaria y Secundaria (Hobbs, 2010; Tuzel, 2013a; Tuzel, 2013b). Sin duda, la alfabetización hoy es «situacionalmente específica» y «dinámicamente cambiante» (Coiro, Knobel, Lankshear, & Leu, 2008: 5) por todo el mundo. En Turquía, por ejemplo, ha habido una inversión significativa en dotar a las escuelas de Educación Primaria y Secundaria de acceso a la tecnología digital para apoyar la enseñanza y el aprendizaje (Unal & Ozturk, 2012).

En este artículo presentamos un caso práctico de colaboración internacional que involucra a profesores de Educación Secundaria de dos países trabajando en colaboración con los autores para diseñar e implementar una experiencia de aprendizaje intercultural que una a alumnos de séptimo grado turcos y norteamericanos usando redes sociales y medios digitales. El objetivo de la iniciativa fue diseñado para ayudar a los alumnos a: a) Desarrollar confianza a la hora de expresarse usando las redes sociales; b) Promover el conocimiento cultural y el pensamiento crítico en torno a los medios y la cultura popular; c) Avanzar hacia una comprensión global entre alumnos de Turquía y de los Estados Unidos. Al unir la educación específica en estudios sociales y la educación en el idioma inglés, esta iniciativa exploró cómo usar el poder de las redes sociales para lograr una interacción social y cultural sostenida en un periodo de seis semanas. La evidencia de este estudio demuestra que el uso de medios digitales y redes sociales para activar la voz de los menores requiere sensibilidad a las diferentes percepciones del valor de la cultura popular entre los profesores, así como una apreciación sólida de las asimetrías y desigualdades aún inherentes a los flujos de información y entretenimiento globales.

1.1. Digitalización del aprendizaje intercultural

La globalización y la tecnología digital se han combinado para abrir las culturas a un mundo en constante cambio y los educadores han sido inspirados para llevar el mundo a sus aulas, permitiendo a los alumnos tener una voz cívica (Hobbs, 2010; Stornaiuolo, DiZio, & Helming, 2013). Si bien los programas tradicionales globales de amistad por correspondencia han tenido lugar en EE.UU. desde los años 20 (Hill, 2012), en los años siguientes al ataque terrorista del 11/S algunos educadores comenzaron a explorar cómo fomentar la voz de sus alumnos y una comprensión global para unir las experiencias de los estudiantes estadounidenses con las de las gentes de Oriente Medio mediante experiencias de aprendizaje intercultural. Para aumentar las experiencias de los alumnos con gente distinta de ellos, este tipo de proyectos deben incluir el trabajo con estudiantes internacionales de universidades locales, organizaciones de inmigrantes dentro de la comunidad, proyectos de servicio y aprendizaje, intercambios mediante e-mail o vídeos y viajes de los alumnos al extranjero (Merryfield, 2002). En estos proyectos los profesores pueden pedir a los alumnos que usen el e-mail o la comunicación online para desarrollar su destreza frente al teclado, compartir poesía, escribir informes y diarios, todas ellas dimensiones fundamentales de la alfabetización.

El crecimiento de las redes sociales ha facilitado que profesores y alumnos de distintas culturas puedan conocerse y trabajar juntos. Los profesores pueden alentar las experiencias de aprendizaje intercultural como una experiencia transformadora que enseñe a los menores a preocuparse y marcar la diferencia en el mundo, al tiempo que intentan marcar una diferencia en el mundo (Aldridge & Goldman, 2007: 78). Estos esfuerzos pueden resultar útiles no solo para los alumnos, sino también para los profesores. Los proyectos interculturales no solo pueden promover la confianza en la propia expresión, sino también el desarrollo de un conocimiento reflexivo-sintético, un concepto articulado por Kincheloe (2004), quien lo describió como un proceso que fomenta la propia voz de los estudiantes al tiempo que revela a profesores y alumnos las otras asunciones ocultas sobre la naturaleza del conocimiento mismo.

1.2. Alfabetización mediática y digital para una educación global

El término «alfabetización digital» surgió para reflejar la amplia constelación de prácticas necesarias para un crecimiento online (Rheingold 2012; Gilster, 1999). La mayoría de conceptualizaciones se enfocan en las habilidades pragmáticas asociadas con el uso de herramientas y textos digitales. Como apuntan Greenhow, Robelia y Hughes (2011: 250), «La alfabetización digital incluye el conocimiento de cómo y cuándo usar qué tecnologías y de qué formas y funciones son más adecuadas a los propósitos de uno». Pero otras definiciones conceptualizan explícitamente la alfabetización digital como una competencia más amplia, sumándose a la tradición de la alfabetización mediática e incluyendo la capacidad de los alumnos de acceder, analizar, crear, reflexionar y actuar usando el poder de la comunicación y la información para marcar una diferencia en el mundo (Hobbs, 2010).

Desde una perspectiva aún más amplia, en Europa, Asia, Latinoamérica y África, el término «alfabetización mediática y de la información (media and information literacy, o MIL) ha sido reconocido como un medio para fomentar un acceso más equitativo a la información y el conocimiento; promover la libertad de expresión; avanzar en sistemas mediáticos independientes y plurales; y mejorar la calidad de la educación. Al empoderar «a los ciudadanos para que comprendan las funciones de los medios y otros proveedores de información, evaluar críticamente su contenido y tomar decisiones informadas como usuarios y productores de información y contenido mediático», la alfabetización mediática y de la información, si bien a veces parece abarcar campos distintos y separados, se conceptualiza como un conjunto de competencias combinadas necesario para la vida y el trabajo de hoy (UNESCO, 2013: 16).

Solo algunos proyectos escolares han apuntado a una evolución de la voz de los alumnos al conectar a jóvenes de distintas comunidades para promover la comprensión cultural mediante la alfabetización mediática. Por ejemplo, los profesores de educación elemental en EE.UU. usaron una variedad de prácticas de alfabetización mediática, incluyendo el visionado y el debate, el análisis crítico de imágenes, la producción audiovisual y la interacción con jóvenes de Kuwait como medio para que los jóvenes obtengan conocimientos de las gentes y culturas de una región (Hobbs & al, 2011a; Hobbs & al., 2011b). Al hablar de cómo las noticias y la cultura mediática y popular incluyen estereotipos sobre la cultura y sus valores, niños de ocho y nueve años pudieron reconocer que los mensajes mediáticos (incluyendo fotografías, películas, páginas web y libros) pueden ser cuestionados críticamente. Las actividades de análisis y producción mediática pueden ayudar a construir un pensamiento crítico y activar la voz de los alumnos al tiempo que desarrollan un conocimiento y habilidades lingüísticas (Hobbs, 2007; Tuzel, 2012a; Tuzel, 2012b). Por ejemplo, durante el proceso de un proyecto de investigación-acción, un profesor turco que usaba actividades de alfabetización mediática en las artes lingüísticas, usando textos de la cultura popular (películas, series de TV, revistas, etc.) para el aprendizaje, halló un aumento en los niveles de alfabetización mediática, pensamiento crítico y capacidad lingüística de los alumnos; además de expandir la conciencia textual, esta actividad de aprendizaje modificó el concepto de alfabetización de los alumnos desde lo alfabético hacia lo multimodal (Tuzel, 2012a).

Las redes sociales y otros entornos virtuales tienen el potencial de jugar un papel importante a la hora de cultivar la curiosidad intelectual y desarrollar una voz cívica junto con el aprendizaje sobre personas y culturas de todo el mundo. El diálogo intergrupal (que generalmente involucra a jóvenes adultos) se ha probado efectivo para combatir los estereotipos negativos y prejuicios sobre países y culturas, promoviendo la tolerancia y la aceptación intercultural (Hurtado, 2005) y un número creciente de organizaciones está acercando los diálogos globales a los alumnos usando medios digitales (Soliya, 2014). Sin embargo, las asimetrías históricas de estatus y poder entre los grupos pueden afectar a la calidad del aprendizaje para los miembros de grupos mayoritarios/empoderados y minoritarios/desempoderados (Cikara, Bruneau, & Saxe, 2011).

Por consiguiente, basándonos en este análisis literario, informamos sobre los resultados de una única actividad escolar que apuntaba a activar la voz de los alumnos y a promover una concienciación global. En la investigación exploratoria examinamos los siguientes interrogantes: ¿Cómo experimentaron el proyecto de comunicación intercultural los estudiantes y profesores de EE.UU. y Turquía? ¿Cuáles fueron los logros y limitaciones del uso de una actividad de intercambio por redes sociales a la hora de activar la voz de los alumnos y construir una comprensión intercultural?

2. Métodos

Esta sección resume brevemente el método de estudio empleado para explorar el uso de una red social privada para facilitar el aprendizaje mutuo de profesores y alumnos de Educación Secundaria en los Estados Unidos y Turquía. El proyecto fue diseñado para permitir a los alumnos estadounidenses y turcos: a) desarrollar confianza a la hora de expresarse usando redes sociales; b) promover el conocimiento cultural y el pensamiento crítico sobre los medios y la cultura popular; c) desarrollar una comprensión cultural global entre los alumnos de Educación Secundaria en Turquía y los Estados Unidos. Al unir la educación en estudios sociales y la educación en el idioma inglés, esta iniciativa ayudó a profesores y alumnos a explorar cómo usar el poder de una red social para lograr una interacción social y cultural sostenida.

Los investigadores desarrollaron e implementaron un programa de experiencia de aprendizaje internacional usando una red social privada en colaboración con el personal de la Blossom School (el pseudónimo de una escuela privada en Turquía Occidental). El análisis minucioso de una lección nos dio la oportunidad de reunir información exploratoria sobre la forma en que profesores y alumnos perciben el valor de usar la propia voz para conocer a gente de otra cultura y aprender sobre sus vidas, experiencias e intereses.

Un total de 84 niños entre las edades de 12 y 14 años participó en el proyecto. Un profesor de historia de Educación Secundaria en George School en EE.UU., y sus 43 alumnos de séptimo grado, trabajó junto a cinco profesores de inglés en la Escuela Blossom en Turquía, junto a dos estudiantes con una maestría en Educación y 41 alumnos turcos de séptimo grado matriculados en una clase de inglés.

2.1 Proceso de investigación

En este estudio, las entrevistas, documentos, observaciones, grabaciones de vídeo y las muestras de trabajo de los alumnos se usaron para analizar la calidad de la experiencia de aprendizaje. Los investigadores realizaron entrevistas tanto a profesores como a los alumnos antes, durante y después de la implementación para registrar los pensamientos y opiniones de los profesores y alumnos. Los investigadores prestaron especial atención a los cambios en los comentarios de los alumnos sobre la otra cultura. Los autores también se enfocaron en los motivos de las publicaciones e interacciones de los alumnos. Por lo tanto, los autores trataron de realizar un extenso análisis de las causas de los eventos y situaciones (Ellet, 2007: 19). La triangulación de datos da una mayor confiabilidad en tanto en cuanto se usaron distintas herramientas de recolección de datos en la red social, incluyendo entrevistas, observación y análisis escrito y visual de documentos. En ambas escuelas los alumnos participaron en el proyecto y realizaron las tareas que les fueron requeridas de forma voluntaria durante la implementación.

2.2. Desarrollo curricular

Usando el modelo de una asociación universidad-escuela, los profesores de Educación Secundaria turcos y estadounidense trabajaron en colaboración con los investigadores para preparar cuatro planes lectivos basados en los principios fundamentales de la alfabetización mediática (NAMLE, 2008). Las asociaciones universidad-escuela dan un importante respaldo a los educadores que apuntan a explorar prácticas instructivas innovadoras en la alfabetización mediática (Moore, 2013). El desarrollo de cuatro planes lectivos permitió a los alumnos compartir información sobre su cultura y valores familiares y comunitarios, aprender más sobre la historia, prácticas culturales y normas sociales de estas dos culturas, y analizar críticamente las representaciones mediáticas de cultura y valores del entretenimiento popular. La Tabla 1 ofrece un resumen del programa curricular completo con los cinco elementos de la definición de la alfabetización mediática y digital: acceder, analizar, crear, reflexionar y actuar (AACRA) (Hobbs, 2010). Los investigadores y profesores se preocuparon de incluir un balance de las experiencias de aprendizaje que animaron a los alumnos a conocer estas dimensiones en el contexto de la experiencia global del aprendizaje cooperativo. Antes de implementar el plan curricular, los investigadores mantuvieron reuniones de planificación online con los profesores, tanto turcos como norteamericanos, en las que se estableció un programa y un proceso de aprendizaje y los alumnos fueron pre registrados en la red social en cuestión.

3. Resultados

Para enfocarnos en la manera en que los alumnos desarrollaron confianza a la hora de expresarse en redes sociales hallando puntos en común con sus pares del otro lado del mundo, describimos y analizamos tan solo la implementación de la primera lección. En un análisis minucioso de la actividad «Conociéndonos», los menores tuvieron la ocasión de compartir ideas informalmente en redes sociales, usando sus voces digitales para compartir significados mediante la escritura online y la publicación de imágenes. Mientras los alumnos valoraron la oportunidad de entablar relaciones entre sí compartiendo su interés común en películas de Hollywood, actores, famosos, videojuegos y programas de televisión, los profesores tenían perspectivas muy distintas sobre el valor de esta actividad. Mediante la comunicación informal sobre la cultura popular, los propios alumnos descubrieron que sus conocimientos en común tendían a estar centrados en EE.UU., en tanto en cuanto los estudiantes americanos no tenían acceso a la cultura popular turca. La actividad puso en primer plano las dinámicas asimétricas de poder que existen en la cultura mediática popular en la que los flujos de información y entretenimiento son de naturaleza unidireccional y las percepciones sobre el valor de la cultura popular se cuestionan. Como corresponde a este estudio, intercalamos la interpretación con la descripción narrativa.

3.1. Aprender a hablar entre culturas

• La lección 1, «Conociéndonos», fue una actividad para romper el hielo que apuntaba a presentar a los alumnos entre sí y ayudarles a desarrollar confianza a la hora de interactuar con otros a medida que se familiarizaban con la red social Ning. A través de esta actividad los alumnos comenzaron a descubrir sus semejanzas y diferencias. Los profesores pidieron a los alumnos que compartieran tres cosas sobre ellos y su cultura en una semana; no pusieron límites en cuanto a la estructura, extensión o contenido de las publicaciones. Los 84 alumnos turcos y americanos participantes podían compartir una frase, foto, vídeo o cualquier otra cosa que quisieran compartir. Para apoyar a los alumnos en el proceso de formación de relaciones, se asignó a los participantes a un grupo de siete (con seis alumnos en cada grupo). La estructura en grupos pequeños hizo que fuera más fácil para los alumnos leer y seguir las publicaciones de los otros y responderlas personalmente. Los alumnos compartieron 391 publicaciones durante la implementación de la lección 1, con una media de 4,6 publicaciones por alumno durante la semana. Algunas de estas publicaciones eran preguntas diseñadas para interpelar a otro alumno, mientras otras apuntaban simplemente a presentarse ellos mismos y su cultura.

Los alumnos demostraron un interés significativo a la hora de participar en esta actividad. Sin embargo, en los primeros días a veces les resultaba difícil responder a preguntas o hacer comentarios a las publicaciones de otros. Los dos motivos principales parecen obvios: fundamentalmente, los alumnos turcos se expresaban en un idioma extranjero mientras que los alumnos norteamericanos lo hacían en su lengua natal. Además, las diez horas de diferencia entre la Escuela Blossom y la Escuela George hizo que al principio les resultara complicado entender cómo seguir los comentarios de los otros. Les llevó unos días comprender cómo navegar y leer las publicaciones, pues los alumnos turcos y estadounidenses publicaban sus comentarios en diferentes momentos del día (en la escuela) y por las tardes (en casa). La novedad de «hablar» saltando las barreras espacio-temporales fue fascinante para muchos alumnos jóvenes. Al principio, un alumno de la Escuela George escribió:

• Estudiante 1 de EE.UU.: «Este es un comentario un tanto aleatorio, pero creo que es alucinante pensar en el hecho de que dos personas pueden estar sentadas frente a un ordenador, escribiendo en el mismo foro, pero para una de ellas es por la mañana temprano (son las 10:40 de la mañana mientras escribo esto) y para la otra es de noche (creo que son las 8:40 de la noche en Turquía)».

Los alumnos disfrutaron la oportunidad de interactuar socialmente y compartir información sobre su propia cultura. En general, los alumnos preferían escribir frases simples. Sin embargo, también subían fotos y vídeos de ellos mismos, sus amigos y familia, sus lugares y comida favorita. Algunos alumnos compartieron links de música, películas, series y videojuegos que amaban, preguntaban qué pensaban sus pares sobre ellos, o respondían a preguntas similares. Los investigadores observaron que los alumnos visitaban sus perfiles y el foro muchas veces durante la semana mientras se implementaba la lección 1. El comportamiento de los alumnos refleja la observación de Stern (2008) sobre el auténtico placer personal que experimentan los adolescentes al usar las redes sociales para presentarse y obtener la aprobación de sus pares.

El análisis de las 391 publicaciones compartidas por los alumnos durante esta actividad revela una amplia gama de temas. Algunos de estos temas cubren elementos ordinarios de la vida cotidiana, la comunidad y el entorno, actividades favoritas, tareas escolares, información sobre sus padres y hermanos y su relación con ellos, los países que habían visitado y sus comidas favoritas. Los alumnos estaban muy abiertos a interactuar y mostraban curiosidad sobre las vidas de los otros. Querían informar a los alumnos con los que hablaban y desarrollar los temas de sus conversaciones. Nótese la clara evidencia del desarrollo de relaciones que se muestra en el siguiente intercambio:

• Estudiante 2 de EE.UU.: «Mi hermano tiene 16 años. ¿Cuántos años tiene tu hermano? Estudiante turco 1: Mi hermano tiene ocho años. Es más joven que yo. También tengo perros. Tengo 2 perros. Uno de mis perros tiene 3 cachorros. Son muy tiernos, quizá pueda compartir su foto. ¿Y tus perros? ¿Podrías compartir sus fotos?».

La actividad claramente permitió a los alumnos desarrollar confianza y respeto y también pudo haber evitado que se interpelaran basándose en estereotipos, ayudando a que se vieran unos a otros como individuos. En uno o dos días, los alumnos estadounidenses, que pensaban que estaban interactuando con gente de Oriente Medio, se dieron cuenta de que los estudiantes con los que hablaban eran individuos con familias, vidas personales y hobbies. Dejaron de ver a los alumnos de la otra escuela como un grupo de extranjeros y comenzaron a verlos como individuos. Lo mismo sucedió con los estudiantes turcos, que podían haber tenido estereotipada la cultura americana.

3.2. Hallando puntos en común a través de los medios y la cultura popular

Más de dos tercios de las interacciones sociales que tuvieron lugar durante la lección 1 se enfocaron en el hallazgo de puntos en común mediante intereses compartidos en los medios de masas, en tanto en cuanto los alumnos hablaron sobre actores, películas, series de TV, videojuegos, libros populares, música y temas parecidos. En estos diálogos, muchos alumnos descubrieron que les interesaba el mismo tipo de productos de cultura popular que a los alumnos del otro país. Les emocionó descubrir sus intereses comunes sobre música, moda, juegos y películas.

Gracias a estos diálogos, los menores se dieron cuenta de que aunque vivían en distintas partes del mundo, admiraban a los mismos cantantes y actores, veían las mismas películas y series de TV y jugaban a los mismos videojuegos en su tiempo libre. Les emocionó reconocer que la cultura popular era un tipo de cultura global común. La cualidad informal del lenguaje y expresiones usadas en la red social, además de la cantidad de conversaciones sobre medios y cultura popular, fue un tanto enervante para los profesores de inglés de Turquía que no estaban familiarizados con la pedagogía de la alfabetización mediática. Para ilustrar este punto vale la pena considerar este intercambio entre adolescentes turcos y norteamericanos:

• Estudiante turco 3: Conoces Mythbusters ese programa es muy bueno.

• Estudiante norteamericano 4: ¡ODM! ¡Ese programa es increíble!

• Estudiante norteamericano 6: Sí yo solía verlo y quería hacer las cosas que hacían en él. Pero era un poco peligroso.

• Estudiante turco 5: Sí, vuelan todo por los aires :D

• Estudiante norteamericano 3: Jajajajajajajajaja, ¿Conoces el programa «Top Gear»?

• Estudiante turco 3: Sí, es un programa americano, ¿cierto?

• Estudiante norteamericano 3: En realidad es del Reino Unido pero hay una versión americana y muchas otras versiones, aunque la original es del Reino Unido.

• Estudiante norteamericano 6: No, mis padres no me dejan :(

Durante esta actividad, los alumnos desarrollaron confianza a la hora de expresarse mediante publicaciones, interactuando y haciendo preguntas. Mientras la mayoría usaba un inglés gramaticalmente correcto, otros usaban algunas de las convenciones lingüísticas de los mensajes de textos, incluyendo emoticonos y puntuación excesiva en su escritura informal. Los alumnos descubrieron que tenían conocimientos valiosos que interesaban a otros. En particular, a los alumnos norteamericanos les sorprendió descubrir que los estudiantes turcos conocían sus programas de TV, videojuegos, música y películas favoritas.

3.3. Conflicto de valores sobre cultura popular entre los profesores

Los profesores tenían distintas percepciones sobre el valor de la lección 1, que alentó a los menores a usar las redes sociales como una oportunidad de compartir y conocerse unos a otros como seres humanos. Mr. Herbert, de la Escuela George, estaba muy contento de que sus alumnos comenzaran a aprender más sobre los intereses personales de los alumnos turcos. Le gustó que los alumnos pudieran activar sus conocimientos extraescolares sobre deportes, medios, música y vida familiar a la hora de interactuar con estudiantes de Educación Secundaria de Turquía en las redes sociales. Debido a que los alumnos sabían tan poco sobre la vida cotidiana en Turquía, Mr. Herbert pensaba que sus alumnos estaban aprendiendo de sus pares turcos a «cuestionar los prejuicios y estereotipos transmitidos por los medios de masas norteamericanos» sobre las personas y culturas de Oriente Medio. Al final de la primera semana de la actividad, advirtió cambios de actitud en los alumnos en los debates dentro de la clase y se enfocó en los cambios observados en los prejuicios de los alumnos. Describió cómo los alumnos comenzaron a cuestionar sus conocimientos sobre Oriente Medio y Turquía.

En cambio, los profesores de la Escuela Blossom en Turquía tenían una perspectiva distinta sobre el valor de la lección 1. Los profesores turcos habían esperado que el proyecto fuera una oportunidad para promocionar la cultura y valores turcos. Por este motivo, se mostraron disgustados de que en la lección 1 los alumnos tratasen principalmente la cultura popular americana. Los profesores alentaron a sus alumnos a hablar sobre elementos de la cultura turca como el tradicional café turco, las alfombras, la comida, geografía, historia y hospitalidad. Pese a estos consejos, los alumnos turcos seguían publicando comentarios sobre medios de masas norteamericanos y cultura pop. En una entrevista, Mr. Yaman mostró su preocupación, «En este proyecto queríamos que los alumnos promocionasen su estilo de vida y cultura entre los estudiantes norteamericanos. Creo que deberían enfocarse en la cultura turca, pero sobre todo hablaban sobre películas y celebridades norteamericanas». Uno de los alumnos universitarios turcos que ayudó a los profesores turcos en este proyecto dijo: «Vi que los profesores no estaban cómodos con que los alumnos usaran redes sociales e hicieran vídeos, sobre todo cuando dicha actividad llevó a la producción de textos sobre cultura popular que amenazaba el programa de estudios nacional obligatorio de la escuela y la autoridad de los profesores».

Estos hallazgos encajan con el trabajo de Moore (2013) que habla de varias fuentes de ansiedad entre los profesores de Educación Primaria y Secundaria en cuanto a la inclusión de la cultura popular en las clases. Si bien el aprendizaje informal en contextos educativos formales puede ser muy valioso, este estudio ilustra que experiencias con el uso de la propia voz en una red social puede «configurar la construcción de conocimiento de los jóvenes en formas inesperadas», inspirando a los profesores a «estructurar prácticas informales que no estaba previsto que tuvieran un lugar legítimo en la educación formal» (Greenhow & Lewin, 2015: 18).

3.4. Descubrimiento de asimetrías en el acceso a los medios y a la cultura popular

Los alumnos turcos se mostraron tan emocionados por descubrir sus intereses comunes como decepcionados al ver que los alumnos norteamericanos tenían un conocimiento tan limitado de la cultura y los medios turcos. Algunos alumnos turcos preguntaron a sus pares norteamericanos por su familiaridad con determinados actores y músicos turcos. Los niños turcos tenían curiosidad por saber si los alumnos norteamericanos conocían las mejores y más famosas películas y series de TV turcas. Sin embargo, no obtuvieron respuesta. Debido al desarrollo histórico, tamaño y escala de la industria mediática de EE.UU., los norteamericanos tienen menos acceso a la cultura popular global que la gente de otras nacionalidades (Crothers, 2013). Por ejemplo, solo siete ciudades en los Estados Unidos transmiten el canal de televisión Al Jazeera America (Cassara, 2014).

Al ser entrevistados, muchos niños turcos mostraron su decepción con el hecho de que las conversaciones sobre cultura popular fueran una «calle de un solo sentido» con el único foco en los medios norteamericanos de Hollywood y Silicon Valley. La asimetría en los conocimientos sobre cultura popular a veces resultaba frustrante para los alumnos turcos. Por ejemplo, un estudiante turco dijo: «Nosotros conocemos las series de TV americanas, sus películas y cantantes. Justin Bieber es muy famoso y lindo tanto para ellos como para nosotros. Pero también hay cantantes en nuestro país que son tan lindos y talentosos como Justin Bieber, pero ellos no los conocen».

Con el tiempo, los niños norteamericanos también se dieron cuenta del problema de la asimetría, y hacia el final del plan de estudios de seis semanas ambos grupos habían aumentado su percepción de las asimetrías en su relación online que eran el resultado de las diferencias estructurales, económicas y políticas en el sistema mediático global. Mr. Herbert, el profesor americano, apoyaba el descubrimiento del problema del acceso asimétrico por parte de los niños. Según el profesor, para algunos alumnos fue un shock darse cuenta de que, pese a su estatus privilegiado como alumnos americanos matriculados en una escuela privada, no tenían acceso a la información y entretenimiento globales de Turquía. Fue una experiencia reveladora que puso a los niños frente a la intersección de dinámicas individuales e institucionales funcionando en relación con el imperialismo cultural (Schiller, 1969) donde la búsqueda de intereses comerciales por parte de corporaciones transnacionales de EE.UU. socavaba la autonomía cultural de otros países por todo el mundo. Al final de la experiencia de aprendizaje, un alumno norteamericano escribió: «Aprendí que el mundo fuera de EE.UU. es bastante parecido al nuestro, y que distintas personas ven cosas distintas de maneras diferentes. Pero me di cuenta de que no sé nada sobre la cultura y la vida turca. Aprendí mucho de esto, ¡Fue fantástico!».

La globalización mediática ha creado nuevos tipos de desigualdades entre naciones en relación a la producción y distribución global mediática que reflejan problemas más amplios de dependencia política y económica (Boyd-Barrett, 1998). El aumento de la globalización mediática, que surgió a principios del siglo XX de la exportación global del cine de Hollywood, ahora se ha expandido para incluir música, videojuegos, publicidad, merchandising y cultura de celebridades. No era esperable descubrir que, en la medida que el uso de una red social privada empoderaba la voz de los alumnos, también les permitía desarrollar una mayor comprensión de los flujos globales de entretenimiento e información que configuran la manera en que los productos culturales son compartidos y experimentados. No era esperable que los jóvenes aprendiesen a usar sus voces digitales interactuando con pares extranjeros hallando puntos en común en los placeres de las películas, programas de televisión, videojuegos y música popular. No era esperable que esta práctica resultara controvertida para los profesores. Mediante el análisis minucioso de una actividad en la que los adolescentes interactuaban formalmente entre sí para hallar puntos en común, este estudio es el primero en demostrar que, en la interacción con pares globales, incluso los adolescentes más jóvenes pueden comenzar a reconocer la naturaleza de los flujos de información unidireccionales dirigidos por el sistema mediático global en el que la música, películas y videojuegos norteamericanos lo dominan todo.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

La oportunidad de hablar saltándose las limitaciones espacio-temporales puede ser transformadora. Este artículo ha ofrecido el estudio del caso práctico de una colaboración entre profesores en Estados Unidos (EE.UU.) y Turquía, donde alumnos de séptimo grado interactuaron entre sí informalmente a través de una red social como medio para activar la voz de los alumnos y promover la comprensión cultural. En el contexto de esta experiencia de aprendizaje global en escuelas de Secundaria, los menores tuvieron la oportunidad de compartir ideas a través de una red social, usando la escritura online, la publicación de imágenes y la creación de películas cortas, pósters y cómics electrónicos. Se ha mostrado que hay valor educativo en el uso informal de las redes sociales con adolescentes, cuyo uso de las redes sociales en la escuela en el contexto de los estudios sociales y la enseñanza de un idioma extranjero aún no ha sido ampliamente estudiada. Para los adolescentes puede ser empoderador descubrir que la gente de tierras lejanas tiene familias, mascotas, amigos y todas las alegrías, problemas y preocupaciones ordinarias que se tienen al crecer. La oportunidad de usar las redes sociales para mantener una conversación –hallando puntos en común– puede tener beneficios que incluyen pero van más allá del dominio y uso de la gramática inglesa.

Los medios digitales son útiles para cruzar fronteras de todo tipo. Mientras que los alumnos valoraron la oportunidad de relacionarse entre sí compartiendo sus intereses comunes en las películas de Hollywood, actores, celebridades, videojuegos y programas de televisión, los profesores tenían perspectivas muy distintas del valor de esta actividad. Si bien se anticipaba que este proyecto nos permitiría explorar cómo los adolescentes exploran los límites geográficos y culturales, esta investigación demuestra que la actitud de los profesores sobre cultura popular representa otra línea divisoria clara que puede respaldar, profundizar o limitar el valor de las prácticas educativas de alfabetización digital, en particular cuando las actividades en redes sociales son usadas por los alumnos para involucrarse en un auténtico diálogo intercultural. Será necesario investigar más para terminar de comprender las condiciones bajo las que el uso de las redes sociales para compartir conocimientos informales puede convertirse inadvertidamente en un tipo de brecha de poder entre los alumnos y los adultos.

Este estudio tiene implicaciones para el desarrollo profesional de los educadores interesados en la voz estudiantil. Cuando los alumnos sean capaces de expresarse libremente, inevitablemente se revelarán sus auténticos y profundos lazos con los medios de masas y la cultura popular. Los profesores que puedan ser ambivalentes, conflictivos o incluso hostiles con la cultura popular en la clase y con su desarrollo profesional deben abordar este tema en el contexto del aprendizaje digital. Por este motivo Hagood, Alvermann y Heron-Hruby (2010) han sugerido que los profesores que participen en programas de desarrollo profesional a largo plazo cuidadosamente diseñados deberían aprender a sentirse cómodos integrando textos de cultura popular en sus programas educativos. Según Alvermann (2012: 218) «que dichas construcciones de la identidad a menudo se hagan visibles mediante películas, música, letras de rap, etcétera, es una razón más para que los textos de cultura popular tengan un lugar en el programa de estudios de una escuela y en sus clases». Por supuesto, puede haber razones válidas por las que algunos alumnos no deseen explorar sus identidades mediante textos de cultura popular incluidos en el programa educativo, especialmente si (sin importar cuán bienintencionadas) las actividades de clase colonizan o trivializan los intereses de los jóvenes (Burn, Buckingham, Parry, & Powell, 2010).

Pero debido a que los educadores tienen una relación de amor-odio con los medios de masas, la cultura popular y los medios digitales, estas actitudes inevitablemente entran en juego cuando se usan tecnologías digitales en la educación. Reconocemos la gran oportunidad que pueden suponer los proyectos interculturales a la hora de promover una postura reflexiva entre los profesores, que pueden hallar las particularidades de sus valores mediante proyectos colaborativos como el que describimos en este artículo. Puede ser que algunas suposiciones ocultas sobre la naturaleza del conocimiento mismo, incluyendo el posicionamiento a veces rígido y jerárquico de «alta» y «baja» cultura puedan revelarse mediante actividades que permitan a los alumnos traer al aula su experiencia vivida de cultura popular y vida diaria (Hobbs & Moore, 2013). En el diseño y desarrollo de pedagogías instructivas que usen redes sociales para promover el diálogo intercultural, los profesores pueden beneficiarse de oportunidades estructuradas para reflejar cómo sus actitudes frente a los medios de masas y la cultura popular pueden dar forma a sus elecciones curriculares y al uso de textos, herramientas y tecnologías digitales.

Referencias