Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This article examines student and teachers’ use and perceptions of Twitter, based on a mixed-method comparative approach. Participants (N=153) were education majors who used Twitter as a part of required coursework in their programs at two universities in Spain and the United States. The theoretical background covers research on international work carried out on Twitter as well as a brief overview of the introduction of technology in two educational national systems. Quantitative data were collected via a survey, while qualitative data were obtained from students’ reflective written texts. The majority of participants from both contexts perceived educational benefits to Twitter. However, their use of Twitter, and the nature of their perceptions of its educational value, appeared to differ in important ways. The U.S. participants’ longer and more frequent use of Twitter was accompanied by more positive beliefs regarding the educational relevance of Twitter. While many Spanish participants saw value in the use of Twitter to find and share information, U.S. students highlighted interactive and collaborative uses. The study uncovers some challenges for learning related to Twitter’s short format. In the conclusion section we discuss implications for learning and teaching in an age of ubiquitous social media.

1. Introduction

This article addresses future educators’ beliefs about and experiences with educational uses of the microblogging service Twitter. Research has suggested that successful ICT implementation is related to not only hardware and teachers’ digital skills, but also to teachers’ beliefs and attitudes (Ertmer & OttenbreitLeftwich 2013). Furthermore, it has been noted that teachers’ attitudes regarding technology are influenced by their own learning experiences with technology as students (Hermans, Tondeur, van Braak, & Valcke 2008). Thus, attention to educators’ beliefs and attitudes is considered by many to be necessary for successful ICT integration in educational systems (Teo, 2009; TiradoMorueta & Aguaded, 2014).

While Twitter is used in many countries and has received significant attention in education (Junco, Heiberger, & Loken 2011; Carpenter & Krutka, 2014a), comparative research on this technology is relatively uncommon. Comparative studies of social media other than Twitter have generally aimed at exploring users’ profiles and their habits and routines (Adnan, Leak, & Longleya, 2014; AmichaiHamburger & Hayat, 2011; Ku, Chen, & Zhang, 2013; Jackson & Wang 2013). However, little previous comparative research on social media has addressed educational applications. Although some research on social media in education has included international samples (Wesely, 2013), a comparative approach that seeks to parse differences among participants from various countries or contexts has been missing.

The current study is based on required, coursebased use of Twitter by university students majoring in education fields, which was mainly aimed at enhancing participants’ engagement with course content and building their digital skills. It also provided an early experience meant to influence the participants’ attitudes and beliefs regarding the use of social media for learning and teaching in their future professional careers. In a previous stage of research (Carpenter, Tur, & Marín, 2016), student teachers’ perceptions of Twitter for their learning and their future professional careers were explored. However, some questions arose from this phase: can these perceptions be influenced by students’ real usage? Are there differences in the way students use Twitter for educational aims? Also, while the impact on students’ learning of some characteristics of Twitter have already been explored, more information was needed and Twitter’s format is further explored in this new step. Thus, this article explores relatively underresearched aspects of the impact of ICT and social media in the educational systems of the USA and Spain from a comparative perspective. Analysing students’ reported behaviours and perceptions, this work explores commonalities and differences in the impact of social media, and Twitter in particular, on educational experiences in these two countries.

2. Background

2.1. Twitter in education

There is a growing interest regarding Twitter in many research areas. In education, previous studies have focused on the employment of microblogging for learning aims and its possible support of innovative teaching practices.

Twitter has been employed for diverse teaching practices since soon after its launch in 2006 (Carpenter & Krutka 2014a; Castañeda, Costa, & TorresKompen, 2011). Shah, Shabgahi and Cox (2015) suggested four uses of Twitter for learning: formal and informal learning community, collaborative learning, mobile learning and reflective thinking. Several studies, such as those by Carpenter (2014), KassensNoor (2012), Marín and Tur (2014), Mercier, Rattray and Lavery (2015) and Tur and Marín (2015), have explored the enhancement of informal and collaborative learning with Twitter. Some research has suggested that such collaboration can reach the level of a Community of Practice (DePaoli & Larooy, 2015; Wesely, 2013). Studies have also demonstrated the impact of Twitter on learning and students’ engagement (Junco, Heiberger, & Loken, 2011; Junco, Elavsky, & Heiberger, 2013) and in particular to overcome obstacles to participation in the context of largelecture classrooms (West, Moore, & Barry, 2015). Twitter has been explored as a tool to support teachers’ professional development (Carpenter & Krutka, 2014a; 2015). The extant literature has also identified challenges associated with educational uses of Twitter, such as the potential for the information flow to be overwhelming for some users (Davis, 2015).

2.2. ICT and Social Media in the Educational Systems of the USA and Spain

Nowell’s (2014) research reported that social media use with U.S. students can improve studentteacher relationships and extend learning beyond the classroom. In the case of Twitter, its use by U.S. educators appears to have been on the rise in recent years (Lu, 2011; University of Phoenix, 2014). Kurtz (2009: 2) described how Twitter provided elementary school parents and families “windows into their children’s days”, while Hunter and Caraway (2014) reported that Twitter positively impacted high school students’ literature engagement and motivation. Twitter does, therefore, appear to offer real educational potential. It remains to be seen, however, to what degree that potential will be realized.

What is now generally understood is the need in Spain to develop students’ digital skills (Area & al., 2014). The Escuela 2.0 programme, which is based on the characteristics of Web 2.0 and social media tools, postulates that every individual can generate and share knowledge (Correa, Losada, & Fernández, 2012). The increased use of Web 2.0 tools for educational aims is likely related to the increase in the use of social media and the development of a knowledge society in Spain. Innovative social media use to support K12 students collaboration and learning has been documented by Basilotta and Herrada (2013). Blogging by primary and secondary students is quite common, as evidenced by the annual awards “Espiral Edublogs” given to student blogs at all grade levels since 2007 (https://goo.gl/8RMxbO). Educational activities with Twitter, however, are not yet as common. Muñoz (2012) reported some use of Twitter in the contexts of primary and secondary level history, philosophy, language learning and storytelling activities. Activities from literature classes based on Spanish masterpieces, such as “El Lazarillo de Tormes” (Molina, 2011) or “Don Quijote” (Domenech, 2015), have also been documented.

3. Research

3.1. Context

This study was set in two different higher education institutions. The sample was one of convenience; the researchers, as employees at these institutions, knew that trainee teachers were using Twitter for required coursework at each university. The University of the Balearic Islands in Spain is the only public university in the region of the Balearic Islands and has different units on the islands of Majorca, Menorca and Ibiza. The university has approximately 11,000 undergraduate and 2000 postgraduate students. Elon University is a private university in the southeast of the United States that enrolls approximately 6000 students.

3.2. Participants

The participants from the University of the Balearic Islands were from the Majorca and Ibiza campuses. They were all students preparing to be teachers, most of them undergraduates (n=85) and, in addition, some postgraduates in Ibiza (n=15). In the case of Majorca, participants were students in their third year of study preparing to be primary school teachers. In Ibiza, primary student teachers were in their first year of study and the other students were studying a Master’s degree program in preparation for teaching. The participants (n=53) from Elon University were all undergraduates in their second, third, or fourth year of studies. The Elon students were preparing to be teachers in a variety of subject areas and at the primary and secondary levels.

3.3. Twitter procedure

Participants in both countries used Twitter as a part of required coursework. Tasks varied according to the different courses in which the participants were enrolled. In both contexts, students were required to have a public Twitter account. They had to “follow” the Twitter accounts of their classmates and other educators or educational organizations beyond their classmates. Students were also required to send a minimum number of tweets that included a course hashtag and related to course content. In the U.S., participants also were required to participate in Twitter chats, which are onehour long, synchronous Twitter discussions focused on a particular topic (Carpenter & Krutka, 2014b). At semester’s end, the students in both settings submitted written reflections on their use of Twitter.

3.4. Research questions

This work aimed to explore the differences in uses of and beliefs regarding social media, in particular Twitter, among students in the USA and Spain. Thus, this study addressed the following research questions:

• Are there differences in the way U.S. and Spanish students use Twitter?

• Are there differences in the way U.S. and Spanish students perceive the educational use of Twitter?

• Are there differences in the way U.S. and Spanish students perceive the short format of Twitter and its impact on learning?

3.5. Methodology

With the aim of a comparative study in mind, we collaborated to design an anonymous online questionnaire to be implemented in both contexts. This instrument, which was designed in Spanish and English to be adapted to each university, gathered quantitative data regarding student experiences with Twitter and their perceptions of Twitter and other social media. At the end of the semester, we asked the participants to write a reflection on their personal experience with the use of Twitter in order to gather qualitative data that would provide rich description and examples to supplement the quantitative findings.

3.6. Instrument

The survey used in Carpenter and Krutka’s (2014a; 2015) research on educators’ use of Twitter was the starting point for the creation of the instrument for this study. The authors’ own experiences and the existing literature on social media use in education informed an initial survey draft in English. We considered cultural differences in order to try to design a survey that would allow participants from both countries to describe their experiences and perceptions. The survey was translated into Spanish, and reviewed by a colleague to ensure that items would be clear to participants. The instrument gathered descriptive statistics regarding the participants, and also included closed questions. The closed questions were measured on nominal or fivepoint ordinal Likert scales.

4. Results

The questionnaire was answered by 153 participants: 100 education majors from Spain (65.4%) and 53 from the U.S. (34.6%).

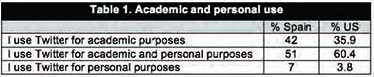

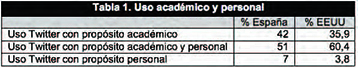

a) Research Question 1: Are there differences in the way U.S. and Spanish students use Twitter? Participants were asked about whether they used Twitter for academic and/or personal reasons (Table 1). In both contexts, majorities reported use for academic and personal purposes. Because the participants were required to use Twitter for at least one of their courses, there were only a few respondents who indicated solely personal purposes. A chisquare test for association indicated there was not a statistically significant association between nationality and the balance of academic and personal use, ?2(2)= 1.503, p=.472.

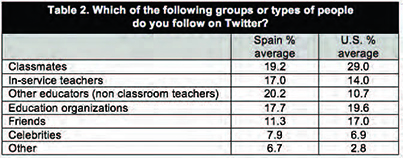

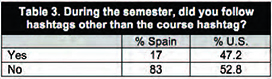

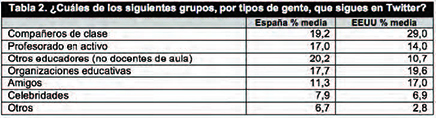

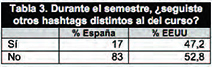

Participants were also asked about their following behavior on Twitter. The survey allowed respondents to choose from a list of types of Twitter users and indicate a percentage for how much they followed each type. The average percentages are shown in Table 2. While among the U.S. students, classmates (29%), education organizations (19.6%) and friends (17%) were most popular, students from the Spain highlighted other educators –non classroom teachers– (20.2%), classmates (19.2%), education organizations (17.7%) and inservice teachers (17%). Because of outliers and the nonnormal distribution of the data, independentsamples ttests were determined to be inappropriate for analyzing this data, and Mann Whitney U tests were instead conducted. Mean rank scores for U.S. and Spanish students were not significantly different for following of inservice teachers (U=2266.5, z=–1.480, p=.139), educational organizations, (U=2318, z=–1.287, p=.198), friends (U =2631, z=.070, p=.944), and celebrities (U= 2494, z=–.628, p=.530). Mean rank scores for U.S. and Spanish participants were, however, statistically significantly different for following classmates (U=1631.5, z= –3.934, p<.001) and other educators who were not classroom teachers (U=1688.5, z=–3.718, p<.001). Respondents were also asked if they followed hashtags apart from the required course hashtag (Table 3). U.S. students were significantly more likely to follow additional hashtags (?2(1) =15.832, p<.001).

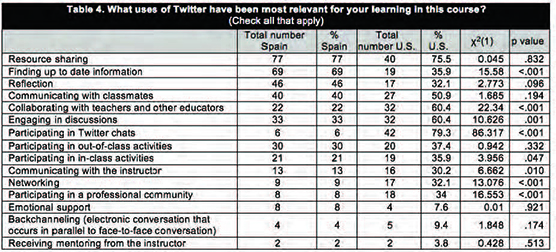

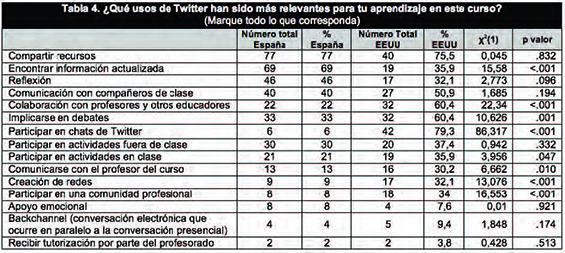

b) Research question 2: Are there differences in the way U.S. and Spanish students perceive the educational use of Twitter? Concerning the uses of Twitter that were most relevant for the students’ learning in the course, participants from both universities highlighted resource sharing, reflecting, and communicating with classmates (Table 4). However, opinions regarding the relevance of many other Twitter uses differed between the two countries. For example, for participants from Spain finding up to date information (69%) was also important; whereas for U.S. respondents participating in Twitter chats (79.3%), collaborating with teachers and other educators (60.4%), and engaging in discussions (60.4%) were more relevant. U.S. participants also tended to perceive a wider variety of relevant learning applications for Twitter, selecting on average 5.86 different uses in contrast to 4.02 relevant uses selected by Spanish participants. These differences in relevance may in part be explained by some of the variation in what students were asked to do in the courses in the two countries. That the U.S. students had, on average, been using Twitter longer for academic purposes might also have contributed to their perceiving a wider variety of relevant learning uses.

Comments from participants’ reflections provided more detailed glimpses of their perceptions of the educational use of Twitter. For example, a Spanish student credited Twitter with helping her to integrate ideas from her course: “I think that we have used it most to transmit the information we found on our own and share it, a true cooperative work. It has been useful to me to put in their place the pieces of many concepts that we were working with in class”. A U.S. student appreciated the multifaceted nature of Twitter and how participants can tailor their use to meet their needs: “I had the ability to follow and connect with so many people on Twitter this semester. I read articles I may not have encountered had it not been for Twitter. I participated in Twitter chats and met teachers who were supportive and gave me great ideas for the future. I truly learned that you can use it to various extents and for different purposes. You can use Twitter however it would best meet your needs and that may be different for every person. I learned from my professor, fellow students, and other individuals related to the world of education”.

c) Research question 3: Are there differences in the way U.S. and Spanish students perceive the short format of Twitter and its impact on learning?

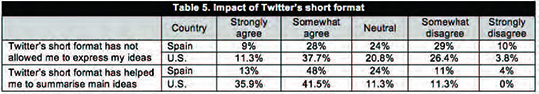

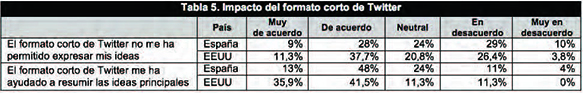

Although many respondents indicated that they perceived multiple relevant uses of Twitter to support their learning in their courses, there was some apparent ambivalence regarding Twitter’s format. One survey item explicitly addressed a potential learning constraint associated with Twitter, asking students their level of agreement with the statement “Twitter’s short format has not allowed me to express my ideas.” For this item, opinions were quite divided (Table 5). A MannWhitney U test was run to determine if there were statistically significant differences in beliefs about the limitations of Twitter’s short format between Spanish and U.S. respondents. Distributions of the Likert scores for Spanish and U.S. students were broadly similar, as assessed by visual inspection. Likert scores for U.S. participants were not statistically significantly different from their Spanish peers, U =2273, z =–1.496, p= .135.

A number of students from both Spain and the U.S. commented in their reflection papers on times that they felt that Twitter did not allow them to communicate their ideas in ways that they preferred. For example, one U.S. participant commented, “Too often I had to edit my tweets to be shorter than I had originally intended, which was frustrating as often I could not say exactly what I wanted due to the word limit.” And a Spanish student explained, «I am too introspective to make quick contributions as [Twitter] needs; I think too much about things before doing them. To write a tweet I have to believe what I write or what I retweet is interesting enough. This means reading well what you are going to write, verifying the reliability of what you say and the source that you use, and looking for the ideas that offer different views… all this is impossible [on Twitter], because it wouldn’t be so immediate as it is supposed to be».

Despite such critiques of limitations associated with Twitter’s short format, a majority of students from both countries indicated either strongly agree or somewhat agree with the statement “Twitter’s short format has helped me to summarise main ideas” (Table 5). A MannWhitney U test was run to determine if there were statistically significant differences in beliefs about this particular benefit of Twitter’s short format between Spanish and U.S. participants. Distributions of the Likert scores for Spanish and U.S. students were not similar, as assessed by visual inspection. Likert scores for U.S. respondents were statistically significantly lower, indicating stronger agreement, than for Spanish peers, U=1918, z=–2.979, p=.003.

5. Discussion and conclusion

Twitter is sometimes dismissed as the frivolous domain of oversharing teens, vain celebrities, and relentless selfpromoters, but in reality these media impact a wide range of serious phenomena such as journalism, political campaigning, protest movements, business marketing, and charity fundraising (Shirky, 2011; Theocharis, Lowe, van Deth, & GarcíaAlbacete, 2015). Our results suggest that students from two different countries perceived that Twitter can also have a meaningful impact in the educational sphere. Students from both contexts indicated they followed classmates and other professional users or institutions more than friends or celebrities, suggesting that despite its reputation, Twitter may be an appropriate tool for educational and professional aims.

The potential for flexible and open learning associated with the introduction of social media into education (Salinas, 2013; Marín, Negre, & PérezGarcías, 2014; Marín & Tur, 2014), together with policies in the USA and Spain that have promoted the integration of ICT in schools, indicate that teacher education programmes should consider how to prepare prospective teachers for new and challenging learning environments. Furthermore, if educators’ attitudes and beliefs about teaching and learning with technology are formed at early stages, even while they themselves are students (Hermans, Tondeur, vanBraak, & Valcke, 2008), and if beliefs can become the most important barriers for future uptake (Ertmer & OttenbreitLeftwich, 2013), it seems that teacher education programmes should attend to their students’ beliefs and perceptions regarding educational uses of technology.

The current work is in line with recent research that focused on attitudes and beliefs for successful ICT integration in educational institutions (Teo 2009; TiradoMorueta & Aguaded, 2014). Furthermore, this work is a step forward in research since it considers educational usages, affordances and drawbacks from a comparative perspective.

In the case of our participants, many in Spain and some in the United States revealed that they had not previously used Twitter for educational purposes, and quite a few expressed surprise at realizing such applications for Twitter. This fact reinforces the need to provide supposed “digital native” students with guidance regarding educational applications of technologies; young people do not inevitably recognize and/or engage with technologies’ learning affordances (Luckin & al., 2009). Scaffolded learning experiences with social media could help to change attitudes and beliefs towards more favourable positions. However, despite majorities in both contexts indicating that they did see educational potential in Twitter, there were still some students who remained skeptical. In our sample, data showed that students in Spain mostly used Twitter for academic purposes for the first time during the semester of our research, whereas more U.S. participants had previously engaged in academic uses of Twitter.

Our research aligns with previous studies that have suggested Twitter’s capacities to impact student learning, especially in terms of collaboration skills, participation, engagement, and course results (Carpenter, 2014; Junco, Heiberger, & Loken, 2011; Junco, Elavsky, & Heiberger, 2013; KassensNoor, 2012; West, Moore, & Barry, 2015). With the aim of exploring particular aspects of this impact, this current research has observed that Twitter has mostly involved students in sharing and finding resources, debating and communicating and, reflecting. Qualitative data confirms this impact, with many of the students noting their surprise regarding the educational value of these activities. Also, the very few comments in Spain about having followed external hashtags is coherent with the low percentage achieved by items related to external discussions. Furthermore, written reflections by students in both countries note the potentially overwhelming impact of access to so much information, which is consistent with conclusions by Davis (2015). Considering the main educational usages of Twitter defined in prior research (Shah, Shabgahi, & Cox, 2015) it seems that students have observed the impact of Twitter for formal and collaborative learning and reflection, and more work would be needed to also enhance informal and mobile learning.

When comparing the experiences of the participants from Spain and the U.S., the U.S. context appeared to be one in which the greater presence of chats and hashtags created more opportunities for Twitter interactions that were attractive to the participants. VanDijck (2011) noted that Twitter can be used in a variety of ways; while chats in the U.S. may have allowed participants to use Twitter more as a twoway communication tool, the less prevalent chat and hashtag use by the Spanish participants may have defined Twitter for them as more of an information and resource sharing tool. Although such sharing can be worthwhile, it may be a less compelling reason for trainee teachers to utilize Twitter if they are already accustomed to accessing more traditional media for information acquisition. Rather than identifying differences in the general, monolithic U.S. and Spanish cultures that affected the participants’ perceptions of Twitter, our findings thus appear to suggest that differences in online practices associated with how technologies are employed in different countries or regions may influence users’ perceptions and uses of technology. Although offline cultures likely influence online behaviors in many cases, there may not always be solely a oneway causal relationship (Qiu, Lin, & Leung, 2013).

Future implementations of educational activities with Twitter should explore the possibilities of two challenging lines of research. First of all, international collaboration among students could be an interesting new iteration since there is evidence that an interactive use of the Internet is related to higher academic achievement (TorresDíaz, Duart, GómezAlvarado, MarínGutiérrez, & SegarraFaggioni, 2016). Secondly, how educational applications of Twitter can contribute to the development of high level thinking skills appears to be an area worthy of exploration.

This study is limited by convenience sampling, which resulted in different group sizes from the two different countries. However, our findings offer a beginning step in research in which the challenging and promising focus is the learning impact that Twitter can have in different academic contexts. Before future research can compare the learning context in greater depth, some previous knowledge on general usage and perception was needed. Thus, from now on, further comparative studies can explore the nuances of the impact of Twitter observed in this study. Future work is needed to promote the educational usage of social media for high level cognitive skills, such as reflection, critical thinking skills, and selfregulated learning, as suggested by recent research (Herro, 2014; Matzat & Vrieling, 2015), and explore the possible differences in terms of age and gender. Finally, since cultural factors could impact social media usage (Carpenter, Tur, & Marín, 2016) new research could address Twitter usage in terms of cultural differences in two main ways: on the one hand, for example, addressing how cultural differences in social norms and anxiety (Heinrichs, & al ,2006) could influence students’ behavior in Twitter; on the other hand, focusing on the educational system, how cultural differences in teaching and learning processes –see for example the model of the four dimensions (Hofstede, 1986)– could influence usages and perceptions of Twitter and social media in general. Likewise, since a process of Americanization of the Spanish Higher Education system has been reported (Lalueza & Collell, 2013), it would be challenging to explore how Twitter is contributing to this phenomenon.

References

Adnan, M., Leak, A., & Longleya, P. (2014). A Geocomputational Analysis of Twitter Activity around Different World Cities. Geo-spatial Information Science, 17(3), 145-152. https://doi.org/10.1080/10095020.2014.941316

Amichai-Hamburger, Y., & Hayat, Z. (2011). The Impact of the Internet on the Social Lives of Users: A Representative Sample from 13 Countries. Computers in Human Behavior, 27, 585-589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.10.009

Area, M., Alonso, C., Correa, J.M., del-Moral, M.E., de-Pablos, J., Paredes, J., Peirats, J., Sanabri, A.L., San-Martín, A., & Valverde, J. (2014). Las políticas educativas TIC en Espan~a después del Programa Escuela 2.0: Las tendencias que emergen. Relatec, 13(2), 11-33. https://doi.org/10.17398/1695-288X.13.2.11

Basilotta, V., & Herrada, G. (2013). Aprendizaje a través de proyectos colaborativos con TIC. Análisis de dos experiencias en el contexto educativo. Edutec, 44. (https://goo.gl/CwdssM) (2016-10-10).

Carpenter, J.P. (2014). Twitter's Capacity to Support Collaborative Learning. International Journal of Social Media and Interactive Learning Environments, 2(2), 103-118. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSMILE.2014.063384

Carpenter, J.P., & Krutka, D.G. (2014a). How and Why Educators Use Twitter: A Survey of the Field. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 46(4), 414-434. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2014.925701

Carpenter, J.P., & Krutka, D.G. (2014b). Chat it Up: Everything you Wanted to Know about Twitter Chats but Were Afraid to Ask. Learning and Leading with Technology, 41(5), 10-15. (https://goo.gl/zptefV) (2016-10-10).

Carpenter, J.P., & Krutka, D.G. (2015). Engagement through Microblogging: Educator Professional Development via Twitter. Professional Development in Education, 41(4), 707-728. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2014.939294

Carpenter, J.P., Tur, G., & Marín, V.I. (2016). What do USA and Spanish Pre-service Teachers Think about Educational and Professional use of Twitter? A Comparative Study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 131-143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.08.011

Castañeda, L., Costa, C., & Torres-Kompen, R. (2011). The Madhouse of Ideas: Stories about Networking and Learning with Twitter. Conference 2011, Southampton, UK. (https://goo.gl/BWtO5L) (2016-10-10).

Correa, J., Losada, D., & Fernández, L. (2012). Polí´ticas educativas y prácticas escolares de integracio´n de las tecnologías en las escuelas del País Vasco: Voces y cuestiones emergentes. Campus Virtuales, 1(1), 21-30. (https://goo.gl/szxG2K) (2016-10-10).

Davis, K. (2015). Teachers’ Perceptions of Twitter for Professional Development. Disability and Rehabilitation, 37(17), 1551-1558. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1052576

De-Paoli, S., & Larooy, A. (2015). Teaching with Twitter: Reflections on Practices, Opportunities and Problems. Paper in EUNIS 2015, Dundee, Scotland (UK), 10-12 June. (https://goo.gl/tqxx0h) (2016-10-10).

Domenech, M. (2015). Completamente quijotizados. La rebotica de literlengua. [Web log post]. (https://goo.gl/J8BTjt) (2016-10-10).

Ertmer, P.A., & Ottenbreit-Letwich, A. (2013). Removing Obstacles to the Pedagogical Changes Required by Jonassen’s Vision of Authentic-enabled Learning. Computers & Education, 64, 175-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.008

Heinrichs, N., Rapee, R.M., Alden, L.A., Bögels, S., Hofmann, S.G., Oh, K.J., & Sakano, Y. (2006). Cultural Differences in Perceived Social Norms and Social Anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(8), 1187-1197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.09.006

Hermans, R., Tondeur, J., Van-Braak, J., & Valcke, M. (2008). The Impact of Primary School Teachers’ Educational Beliefs on the Classroom Use of Computers. Computers & Education, 51, 1499-1509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2008.02.001

Herro, D. (2014). Techno Savvy: A Web 2.0 Curriculum Encouraging Critical Thinking. Educational Media International, 51(4), 259-277. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2014.977069

Hofstede, G. (1986). Cultural Differences in Teaching and Learning. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 10(3), 301-320. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(86)90015-5

Hunter, J.D., & Caraway, H.J. (2014). Urban Youth Use Twitter to Transform Learning and Engagement. The English Journal, 103(4), 76-82. (https://goo.gl/xFZA9h) (2016-10-10).

Jackson, L., & Wang, J.L. (2013). Cultural Differences in Social Networking Site Use: A Comparative Study of China and the United States. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 910-921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.024

Junco, R., Elavsky, M.C., & Heiberger, G. (2013). Putting Twitter to the Test: Assessing Outcomes for Student Collaboration, Engagement and Success. British Journal of Education Technology, 44(2), 273-287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467- 8535.2012.01284.x

Junco, R., Heiberger, G., & Loken, E. (2011). The Effect of Twitter on College Student Engagement and Grades. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 27(2), 119-132. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2729.2010.00387.x

Kassens-Noor, E. (2012). Twitter as a Teaching Practice to Enhance Active and Informal Learning in Higher Education: The Case of Sustainable Tweets. Active Learning in Higher Education, 13(1), 9-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787411429190

Ku, Y.C., Chen, R., & Zhang, H. (2013). Why do Users Continue Using Social Networking Sites? An Exploratory Study of Members in the United States and Taiwan. Information & Management, 50, 571-581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2013.07.011

Kurtz, J. (2009). Twittering about learning: Using Twitter in an Elementary School Classroom. Horace, 25(1), 1-4. (https://goo.gl/QhALU2) (2016-10-10).

Lalueza, F., & Collell, M.R. (2013). Globalization or Americanization of Spanish Higher Education? A Comparative Case Study of Required Skills in the Higher Education Systems of the United States and Spain. Razón y Palabra, 17(4-85). (https://goo.gl/2A54Df) (2016-10-10).

Lu, A. (2011). Twitter Seen Evolving into Professional Development Tool. Education Week, 30(36), 20. (https://goo.gl/jA70Ho) (2016-10-10).

Luckin, R., Clark., W., Graber, R., Logan, K., Mee, A., & Oliver, M. (2009). Do Web 2.0 Tools really Open the Door to Learning? Practices, Perceptions and Profiles of 11-16 year-old Students. Learning, Media and Technology, 34(2), 87-104. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439880902921949

Marín, V.I., & Tur, G. (2014). Student Teachers’ Attitude towards Twitter for Educational Aims. Open Praxis, 6(3), 275-285. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.6.3.125

Marín, V.I., Negre, F., & Pérez-Garcias, A. (2014). Entornos y redes personales de aprendizaje (PLEPLN) para el aprendizaje colaborativo [Construction of the Foundations of the PLE and PLN for Collaborative Learning]. Comunicar, 42, 35-43. https://doi.org/10.3916/C42-2014-03

Matzat, U., & Vrieling, E.M. (2015). Self-regulated Learning and Social Media - A ‘Natural Alliance’? Evidence on Students’ Self-regulation of Learning, Social Media Use, and Student-teacher Relationship. Learning, Media and Technology, 41(1), 73-99. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2015.1064953

Mercier, E., Rattray, J., & Lavery, J. (2015). Twitter in the Collaborative Classroom: Micro-blogging for In-class Collaborative Discussions. International Journal of Social Media and Interactive Learning Environments, 3(2), 83-99. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSMILE.2015.070764

Molina, A. (2011). El Lazarillo de Tormes en Twitter. Plataforma Educa. [Web log post]. (https://goo.gl/Zn9QB4) (2016-10-10).

Muñoz, F. (2012). Experiencias didácticas con Twitter. Educa con TIC. [Blogpost]. (https://goo.gl/UPgyVk) (2016-10-10).

Nowell, S.D. (2014). Using Disruptive Technologies to make Digital Connections: Stories of Media Use and Digital Literacy in Secondary Classrooms. Educational Media International, 51(2), 109-123. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2014.924661

Salinas, J. (2013). Enseñanza flexible y aprendizaje abierto, fundamentos clave de los PLEs. In L. Castañeda, & J. Adell (Eds.), Entornos personales de aprendizaje: Claves para el ecosistema educativo en Red (pp. 53-70). Alcoy: Marfil.

Shah, N.A.K., Shabgahi, S.L., & Cox, A.M. (2015). Uses and Risks of Microblogging in Organisational and Educational Settings. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(6), 1168-1182. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12296

Shirky, C. (2011). Political Power of SocialMedia : Technology, the Public Sphere, and Political Change. Foreign Affairs, 90(1), 28-41. (https://goo.gl/1Th2FL) (2016-10-10).

Teo, T. (2009). Modelling Technology Acceptance in Education: A Study of Pre-service Teachers. Computers & Education, 52(2), 302-312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2008.08.006

Theocharis, Y., Lowe., W., Van-Deth, J.W., & García-Albacete, G. (2015). Using Twitter to Mobilize Protest Action: Online Mobilization Patterns and Action Repertoires in the Occupy Wall Street, Indignados, and Aganaktismenoi movements. Information, Communication & Society, 18(2), 202-220. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/1369118X.2014.948035

Tirado-Morueta, R., & Aguaded, I. (2014). Influencias de las creencias del profesorado sobre el uso de la tecnología en el aula. Revista de Educación, 363, 230-255. https://doi.org/10-4438/1988-592X-RE-2012-363-179

Torres-Díaz, J.C, Duart, J.M., Gómez-Alvarado, H.F., Marín-Gutiérrez, I., & Segarra-Faggioni, V. (2016). Internet Use and Academic Success in University Students. [Usos de Internet y éxito académico en estudiantes universitarios]. Comunicar, 48(24), 61-70. https://doi.org/10.3916/C48-2016-06

Tur, G., & Marín, V.I. (2015). Enhancing Learning with the SocialMedia : Student Teachers’ Perceptions on Twitter in a Debate Activity. New Approaches in Educational Research, 4(1), 46-53. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2015.1.102

Van-Dijck, J. (2011). Tracing Twitter: The Rise of a Microblogging Platform. International Journal of Media and Cultural Politics, 7(3), 333-348. https://doi.org/10.1386/macp.7.3.333_1

Wesely, P.M. (2013). Investigating the Community of Practice of World Language Educators on Twitter. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(4), 305-318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487113489032

West, B., Moore, H., & Barry, B. (2015). Beyond the Tweet: Using Twitter to Enhance Engagement, Learning, and Success among First-year Students. Journal of Marketing Education, 37(3), 160-170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475315586061

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El presente artículo examina los usos y las percepciones de estudiantes y profesores en relación a Twitter a partir de una investigación comparada con metodologías mixtas. Los participantes (n=153) fueron alumnos de educación de dos universidades en España y EEUU que usaron Twitter como parte de una actividad del curso. El marco teórico abarca la investigación internacional sobre Twitter así como un breve repaso a la introducción de la tecnología en los dos sistemas educativos nacionales. Los datos cuantitativos se recogieron con un cuestionario mientras que los datos cualitativos se obtuvieron a través de los textos reflexivos escritos de los estudiantes. La mayoría de los participantes de los dos contextos percibieron los beneficios educativos de Twitter. Sin embargo, su uso de Twitter y la naturaleza de sus percepciones en relación a su valor educativo, difirió de maneras importantes. Los participantes de EEUU usaron Twitter por más tiempo y de manera más frecuente a la vez que demostraron creencias más positivas en relación a la relevancia educativa de Twitter. Mientras que los participantes españoles valoraron el uso de Twitter para encontrar y compartir información, los estudiantes americanos destacaron los usos para la interacción y la colaboración. El estudio destapa algunos retos del formato breve de Twitter para el aprendizaje. En las conclusiones discutimos las implicaciones para la enseñanza aprendizaje en la era de la ubicuidad de los medios sociales.

1. Introducción

Este artículo aborda las creencias y experiencias de los futuros maestros respecto a los usos educativos del servicio de microblogging Twitter. Estudios previos sugieren que la implementación exitosa de las TIC está relacionada no solo con el hardware y las habilidades digitales de los profesores, sino también con sus creencias y actitudes (Ertmer & OttenbreitLeftwich, 2013). Además, se ha puesto de manifiesto también que las actitudes de los profesores respecto a la tecnología se ven influidas por sus propias experiencias de aprendizaje con tecnología como estudiantes (Hermans, Tondeur, vanBraak, & Valcke, 2008). Por lo tanto, se debe prestar atención a las creencias y actitudes de los maestros como un factor necesario para la integración con éxito de las TIC en los sistemas educativos (Teo, 2009; TiradoMorueta & Aguaded, 2014).

Mientras que Twitter se utiliza en muchos países y ha recibido gran atención en el campo educativo (Junco, Heiberger, & Loken, 2011; Carpenter & Krutka, 2014a), es relativamente poco común la aplicación de estudios comparativos de esta tecnología. Los estudios comparativos de redes sociales diferentes a Twitter se han centrado generalmente en explorar los perfiles de los usuarios y sus hábitos y rutinas (Adnan, Leak, & Longleya, 2014; AmichaiHamburger & Hayat, 2011; Ku, Chen, & Zhang, 2013; Jackson & Wang 2013). Sin embargo, pocos estudios comparativos previos sobre redes sociales han tratado sus aplicaciones educativas. Aunque algunos de los estudios sobre redes sociales en educación han incluido muestras internacionales (Wesely, 2013), falta todavía un enfoque comparativo que analice las diferencias entre participantes de varios países o contextos.

El presente estudio se basa en el uso obligatorio de Twitter en una asignatura por parte de estudiantes universitarios del campo educativo, orientado principalmente a fortalecer la implicación de los participantes en el contenido del curso y trabajar sus habilidades digitales. También se planteaba como una experiencia temprana para influir en las actitudes y creencias de los participantes en cuanto al uso de las redes sociales para el aprendizaje y la enseñanza en sus carreras profesionales futuras. En una etapa previa de la investigación (Carpenter, Tur, & Marín, 2016), se exploraron las percepciones de los estudiantes del Grado de Educación respecto a Twitter para su aprendizaje y futuras carreras profesionales. Sin embargo, se desprendieron de ese estudio algunas preguntas: ¿se pueden influir en esas percepciones a partir del uso real de los estudiantes? ¿Hay diferencias en la manera en que los estudiantes utilizan Twitter con fines educativos? Además, mientras que el impacto en el aprendizaje de los estudiantes de algunas características de Twitter ya se ha estudiado, se requiere más información, y el formato de Twitter se ha explorado adicionalmente en esta nueva fase. Por tanto, este artículo indaga en aspectos relativamente poco investigados del impacto de las TIC y las redes sociales en los sistemas educativos de los Estados Unidos (EE.UU.) y España desde una perspectiva comparativa. A través del análisis de los comportamientos y percepciones indicados por los alumnos, este trabajo explora los puntos en común y las diferencias en el impacto de las redes sociales, y Twitter en particular, sobre las experiencias educativas en estos dos países.

2. Marco teórico

2.1. Twitter en educación

Hay un creciente interés por Twitter en muchas áreas de investigación. En educación, estudios anteriores se han centrado en el empleo de las plataformas de microblogging con el objetivo del aprendizaje y su posible apoyo a prácticas docentes innovadoras. Twitter ha sido empleado en diversas prácticas docentes desde poco después de su lanzamiento en 2006 (Carpenter & Krutka, 2014a; Castañeda, Costa, & TorresKompen, 2011). Shah, Shabgahi y Cox (2015) sugirieron cuatro usos de Twitter para el aprendizaje: la creación de comunidades de aprendizaje formal e informal, el aprendizaje colaborativo, el aprendizaje móvil y el pensamiento reflexivo. Varios estudios, como los de Carpenter (2014), KassensNoor (2012), Marín y Tur (2014), Mercier, Rattray y Lavery (2015), y Tur y Marín (2015) han explorado la mejora del aprendizaje informal y colaborativo con Twitter. Algunas investigaciones han sugerido que esta colaboración puede alcanzar el nivel de Comunidad de Práctica (DePaoli & Larooy, 2015; Wesely, 2013).

Otros estudios también han demostrado el impacto de Twitter en el aprendizaje y la implicación de los estudiantes (Junco, Heiberger, & Loken, 2011; Junco, Elavsky, & Heiberger, 2013) y en particular para superar los obstáculos de la participación en el contexto de aulas grandes (West, Moore, & Barry, 2015). Twitter ha sido explorado como una herramienta para apoyar el desarrollo profesional de los docentes (Carpenter & Krutka, 2014a, 2015). La literatura existente también ha identificado los retos asociados con los usos educativos de Twitter, como que el flujo de información sea potencialmente abrumador para algunos usuarios (Davis, 2015).

2.2. TIC y medios sociales en los sistemas educativos de Estados Unidos y España

La investigación de Nowell (2014) informó que el uso de los medios sociales con estudiantes estadounidenses puede mejorar las relaciones entre estos y sus profesores, y ampliar el aprendizaje más allá del aula. En el caso de Twitter, su uso por educadores de EE.UU. parece haber ido en aumento en los últimos años (Lu, 2011; Universidad de Phoenix, 2014). Kurtz (2009: 2) describió cómo Twitter proporcionó a los padres y familias de la Escuela Primaria «ventanas a los días de sus hijos», mientras que Hunter y Caraway (2014) reportaron que Twitter impactó positivamente en la implicación y la motivación de los estudiantes de Secundaria. Twitter, por lo tanto, parece ofrecer un verdadero potencial educativo. Queda por ver, sin embargo, hasta qué grado ese potencial se realizará.

Actualmente en España es aceptada la necesidad de desarrollar las competencias digitales de los alumnos (Area & al., 2014). El programa Escuela 2.0, basado en las características de la Web 2.0 y las herramientas de los medios sociales, postula que cada individuo puede generar y compartir conocimientos (Correa, Losada, & Fernández, 2012). El mayor uso de las herramientas de la Web 2.0 para fines educativos probablemente esté relacionado con el incremento en el uso de las redes sociales y el desarrollo de la Sociedad del Conocimiento en España. Basilotta y Herrada (2013) han documentado el uso innovador de los medios sociales para apoyar la colaboración y el aprendizaje de los estudiantes de Secundaria. Los blogs de los estudiantes de Primaria y Secundaria son bastante comunes, como lo demuestran los premios anuales «Espiral Edublogs» que se dan a los blogs estudiantiles en todos los niveles desde 2007 (https://goo.gl/8RMxbO). Las actividades educativas con Twitter, sin embargo, no son todavía tan comunes. Muñoz (2012) informó de algún uso de Twitter en los contextos de Educación Primaria y Secundaria en asignaturas como historia, filosofía, idiomas y actividades de «storytelling». También se han documentado actividades de clases de literatura basadas en obras maestras españolas, como «El Lazarillo de Tormes» (Molina, 2011) o «Don Quijote» (Domenech, 2015).

3. Investigación

3.1. Contexto

Este estudio se realizó en dos instituciones de Educación Superior diferentes. La muestra era de conveniencia; los investigadores, como empleados de estas instituciones, sabían que los alumnos del Grado de Educación usaban Twitter en trabajos requeridos en cada universidad. La Universidad de las Islas Baleares en España es la única universidad pública de esta Comunidad y tiene diferentes sedes en las islas de Mallorca, Menorca e Ibiza. La universidad tiene aproximadamente 11.000 estudiantes de pregrado y 2.000 de posgrado. Elon University es una universidad privada en el sureste de EE.UU. que matricula aproximadamente 6.000 estudiantes.

3.2. Participantes

Los participantes de la Universidad de las Islas Baleares procedían de los campus de Mallorca e Ibiza. Todos eran estudiantes que se preparaban para ser profesores, la mayoría de grado (n=85) y algunos de postgrado en Ibiza (n=15). En el caso de Mallorca, los participantes eran estudiantes en el tercer año de sus estudios preparándose para ser maestros de primaria. En Ibiza, los maestros de primaria estaban en su primer año y los otros estudiantes estaban haciendo un programa de Máster para la docencia. Los participantes (n=53) de la Universidad de Elon eran todos estudiantes de pregrado en su segundo, tercer o cuarto año de estudios y se preparaban para ser maestros en una variedad de materias de Educación Primaria y Secundaria.

3.3. Actividad con Twitter

Los participantes de ambos países usaron Twitter como parte de un trabajo obligatorio. Las tareas variaron de acuerdo a los diferentes cursos en los que los participantes estaban matriculados. En ambos contextos, los estudiantes tenían que tener una cuenta pública de Twitter. Tuvieron que «seguir» las cuentas de Twitter de sus compañeros y otros educadores u organizaciones educativas más allá de sus compañeros de clase. También debían enviar un número mínimo de tuits que incluyeran un hashtag de grupo y que se relacionara con el contenido del curso. En EE.UU., los participantes tuvieron que participar en chats de Twitter, que son discusiones de Twitter sincrónicas de una hora de duración centradas en un tema en particular (Carpenter & Krutka, 2014b). Al final del semestre, los estudiantes en ambos sitios realizaron reflexiones escritas sobre su uso de Twitter.

3.4. Preguntas de Investigación

Este trabajo tuvo como objetivo explorar las diferencias en usos y creencias con respecto a los medios sociales, en particular a Twitter, entre estudiantes de EE.UU. y España. Así, este estudio abordó las siguientes preguntas de investigación:

• ¿Hay diferencias en la forma en que los estudiantes de EE.UU. y España usan Twitter?

• ¿Existen diferencias en la forma en que los estudiantes estadounidenses y españoles perciben el uso educativo de Twitter?

• ¿Hay diferencias en la forma en que los estudiantes de EE.UU. y España perciben el formato corto de Twitter y su impacto en el aprendizaje?

3.5. Metodología

Con el objetivo de realizar un estudio comparativo, colaboramos para diseñar un cuestionario en línea anónimo para ser implementado en ambos contextos. Este instrumento, diseñado en español e inglés para ser adaptado a cada universidad, recopiló datos cuantitativos sobre las experiencias de los estudiantes y sus percepciones de Twitter y otras redes sociales. Al final del semestre, pedimos a los participantes que escribieran una reflexión sobre su experiencia personal con el uso de Twitter con el fin de reunir datos cualitativos que proporcionaran una rica descripción y ejemplos para complementar los resultados cuantitativos.

3.6. Instrumento

La encuesta utilizada en la investigación de Carpenter y Krutka (2014a; 2015) sobre el uso de Twitter por educadores fue el punto de partida para la creación del instrumento para este estudio. Las propias experiencias de los autores y la literatura existente sobre el uso de medios sociales en la educación fueron la base para un primer borrador del instrumento en inglés. Se consideraron las diferencias culturales para intentar diseñar una encuesta que permitiera a los participantes de ambos países describir sus experiencias y percepciones. Esta fue traducida al español, y revisada por un colega para asegurarse de que los elementos quedaran claros para los participantes. El instrumento recogió estadísticas descriptivas de los participantes, y también incluyó preguntas cerradas. Las preguntas cerradas se midieron en escalas ordinarias de Likert nominales o de cinco puntos.

4. Resultados

El cuestionario fue contestado por 153 participantes: 100 de los estudios de formación docente inicial de España (65,4%) y 53 de EE.UU. (34,6%).

a) Pregunta de investigación 1: ¿Hay diferencias en la forma en que los estudiantes de EE.UU. y España usan Twitter? Se preguntó a los participantes si utilizaban Twitter por razones académicas y/o personales (Tabla 1). En ambos contextos, la mayoría reportó un uso para propósitos académicos y personales. Debido a que los participantes estaban obligados a utilizar Twitter en al menos uno de sus cursos, solo hubo algunos encuestados que indicaron objetivos exclusivamente personales. La prueba chicuadrado de asociación indicó que no había una asociación estadísticamente significativa entre la nacionalidad y el equilibrio de uso académico y personal, ?2(2)=1.503, p=.472.

También se preguntó a los participantes sobre los siguientes comportamientos en Twitter. La encuesta permitía elegir entre una lista de tipos de usuarios de Twitter e indicar un porcentaje de seguimiento de cada tipología. La media de los porcentajes se muestra en la Tabla 2. Mientras que entre los estudiantes estadounidenses, los compañeros (29%), las organizaciones educativas (19,6%) y los amigos (17%) eran los más populares, los estudiantes de España destacaron a otros educadores –que no eran docentes de aula– ( 20,2%), compañeros de clase (19,2%), organizaciones educativas (17,7%) y maestros en activo (17%). A causa de los valores atípicos y la distribución no normal de los datos, se determinó que las pruebas t de muestras independientes eran inapropiadas para analizar estos datos, y en su lugar se realizaron pruebas U de Mann Whitney. Las puntuaciones medias de los estudiantes de EE.UU. y de España no fueron significativamente diferentes en el seguimiento de los profesores en activo (U=2266.5, z=–1.480, p=.139), organizaciones educativas (U=2318, z=–1.287, p=.198), amigos (U=2631, z=.070, p=.944) y celebridades (U=2494, z=.628, p=.530). Sin embargo, las puntuaciones medias de los participantes de EE.UU. y de España fueron estadísticamente significativas en el seguimiento de compañeros (U=1631.5, z=–3.934, p<.001) y otros educadores que no fueran docentes de aula (U=1688.5, z=3.718, p<.001). Los encuestados también fueron preguntados por su seguimiento de hashtags que no fueran los del curso (Tabla 3). Los estudiantes de EE.UU. siguieron significativamente otros hashtags adicionales (?2(1)= 15.832, p<.001).

b) Pregunta de investigación 2: ¿Existen diferencias en la forma en que los estudiantes estadounidenses y españoles perciben el uso educativo de Twitter? En cuanto a los usos de Twitter que fueron más relevantes para el aprendizaje de los estudiantes en el curso, los participantes de ambas universidades destacaron compartir recursos, reflexionar y comunicarse con sus compañeros de clase (Tabla 4). Sin embargo, las opiniones sobre la relevancia de muchos otros usos de Twitter difieren entre los dos países. Por ejemplo, para los participantes de España encontrar información actualizada (69%) también fue importante; mientras que para los encuestados estadounidenses que participaron en chats de Twitter (79,3%), colaborar con el profesorado y otros educadores (60,4%) y participar en discusiones (60,4%) fue más relevante. Los participantes estadounidenses también tendieron a percibir una mayor variedad de aplicaciones de aprendizaje relevantes de Twitter, seleccionando en promedio 5.86 usos diferentes en contraste con 4.02 usos relevantes seleccionados por los participantes españoles. Estas diferencias de relevancia pueden en parte ser explicadas por algunas de las variaciones en lo que se les pidió a los estudiantes que hicieran en los cursos en los dos países. El hecho de que los estudiantes de EE.UU. hubieran estado usando Twitter por más tiempo para fines académicos también podría haber contribuido a percibir una variedad más amplia de usos de aprendizaje relevantes.

Los comentarios extraídos de las reflexiones de los participantes proporcionaron visiones más detalladas de sus percepciones del uso educativo de Twitter. Por ejemplo, una estudiante española aseguró que Twitter la había ayudado a integrar ideas del curso: «Creo que lo hemos usado más para transmitir la información que encontramos por nuestra cuenta y compartirla, una verdadera labor cooperativa. Me ha sido útil poner en práctica parte de los conceptos con los que estábamos trabajando en clase». Un estudiante estadounidense apreció la naturaleza multifacética de Twitter y cómo los participantes pueden adaptar su uso para satisfacer sus propias necesidades: «Tuve la capacidad de seguir y conectar con mucha gente en Twitter este semestre. He leído artículos que no habría encontrado si no hubiera sido por Twitter. Participé en chats de Twitter y conocí a profesores que me apoyaron y me dieron grandes ideas para el futuro. Realmente aprendí que se puede utilizar a diferentes niveles y para diferentes propósitos. Puedes utilizar Twitter como mejor satisfaga tus necesidades y esto hace que pueda ser diferente para cada persona. Aprendí de mi profesor, compañeros, y otras personas relacionadas con el mundo de la educación».

c) Pregunta de Investigación 3: ¿Hay diferencias en la forma en que los estudiantes de EE.UU. y España perciben el formato corto de Twitter y su impacto en el aprendizaje?

Aunque muchos encuestados indicaron que percibían múltiples usos relevantes de Twitter para apoyar su aprendizaje en sus cursos, había una aparente ambivalencia con respecto al formato de Twitter. Un ítem de la encuesta abordó explícitamente una posible limitación del aprendizaje asociada con Twitter, pidiendo a los estudiantes su nivel de acuerdo con la declaración «El formato corto de Twitter no me ha permitido expresar mis ideas». En este ítem, las opiniones resultaron bastante dividas (Tabla 5). Se realizó una prueba U de MannWhitney para determinar si había diferencias estadísticamente significativas en las creencias acerca de las limitaciones del formato corto de Twitter entre los encuestados españoles y estadounidenses. Las distribuciones de las puntuaciones Likert para estudiantes españoles y estadounidenses fueron ampliamente similares, según la evaluación mediante inspección visual. Las puntuaciones de Likert para los participantes estadounidenses no fueron estadísticamente significativas en comparación con sus pares españoles, U=2273, z=–1.496, p=.135.

Varios estudiantes de España y EE.UU., en sus documentos de reflexión, comentaron los momentos en que sintieron que Twitter no les había permitido comunicar sus ideas de la manera que ellos preferían. Por ejemplo, un participante estadounidense comentó: «Demasiado a menudo tuve que editar mis tuits para ser más cortos de lo que había pensado originalmente, lo cual era frustrante, ya que a menudo no podía decir exactamente lo que quería debido al límite de palabras». Y un estudiante español explica, «soy demasiado introspectivo para hacer contribuciones rápidas como [Twitter] necesita; pienso demasiado en las cosas antes de hacerlas. Para escribir un tuit tengo que creer que lo que escribo o retuiteo es lo suficientemente interesante. Esto significa leer bien lo que vas a escribir, verificar la fiabilidad de lo que dices y la fuente que usas, y buscar las ideas que ofrecen diferentes puntos de vista... todo esto es imposible [en Twitter], porque no sería tan inmediato como se supone que es».

A pesar de tales críticas sobre las limitaciones asociadas con el formato corto de Twitter, la mayoría de los estudiantes de ambos países indicaron estar totalmente de acuerdo o bastante de acuerdo con la afirmación «El formato corto de Twitter me ha ayudado a resumir las ideas principales» (Tabla 5). Se realizó una prueba U de MannWhitney para determinar si había diferencias estadísticamente significativas en las creencias acerca de este beneficio particular del formato corto de Twitter entre los participantes españoles y estadounidenses. Las distribuciones de las puntuaciones Likert para estudiantes españoles y estadounidenses no fueron similares, según se evaluó mediante inspección visual. Las puntuaciones de Likert para los encuestados de EE.UU. fueron estadísticamente más bajas, indicando un acuerdo más fuerte que para los pares españoles, U=1918, z=–2.979, p=.003.

5. Discusión y conclusión

Twitter es a veces descartado por considerarse de la esfera frívola de los adolescentes que comparten los detalles de su vida, las celebridades superficiales, y los que se autopromocionan incansablemente, pero en realidad estos medios de comunicación impactan en una amplia gama de fenómenos importantes como el periodismo, las campañas políticas, los movimientos de protesta, el marketing y las organizaciones benéficas (Shirky, 2011; Theocharis, Lowe, VanDeth, & GarcíaAlbacete, 2015). Nuestros resultados sugieren que los estudiantes de dos países diferentes percibieron que Twitter también puede tener un impacto significativo en la esfera educativa. Los estudiantes de ambos contextos indicaron que siguieron a compañeros de clase y otros usuarios profesionales o instituciones más que a amigos o celebridades, lo que sugiere que a pesar de su reputación, Twitter puede ser una herramienta adecuada para fines educativos y profesionales.

El potencial para el aprendizaje flexible y abierto asociado con la introducción de los medios sociales en la educación (Salinas, 2013; Marín, Negre, & PérezGarcías, 2014; Marín & Tur, 2014), junto con las políticas de EE.UU. y España que han promovido la integración de las TIC en los centros educativos, indican que los programas de formación de maestros deberían considerar la forma de preparar futuros profesores para los desafíos de los nuevos entornos de aprendizaje. Además, si las actitudes y creencias de los educadores acerca de la enseñanza y el aprendizaje con la tecnología se forman en las primeras etapas, incluso cuando ellos mismos son estudiantes (Hermans, Tondeur, vanBraak, & Valcke, 2008), y si las creencias pueden convertirse en las barreras más importantes para su futura adopción (Ertmer & OttenbreitLeftwich, 2013), parece que los programas de formación de profesores deben atender a las creencias y percepciones de sus estudiantes con respecto a los usos educativos de la tecnología.

El actual trabajo está en línea con investigaciones recientes que se centraron en las actitudes y creencias para la integración exitosa de las TIC en las instituciones educativas (Teo, 2009; TiradoMorueta & Aguaded, 2014). Además, este trabajo es un paso adelante en la investigación, ya que considera los usos educativos, las posibilidades y los inconvenientes desde una perspectiva comparativa.

En el caso de nuestros participantes, muchos en España y algunos en EE.UU. revelaron que no habían utilizado previamente Twitter con fines educativos, y bastantes expresaron su sorpresa al realizar dichas aplicaciones para esta red social. Este hecho refuerza la necesidad de proporcionar a los supuestos estudiantes «nativos digitales» orientación sobre las aplicaciones educativas de las tecnologías. Los jóvenes inevitablemente no reconocen y/o se implican con las posibilidades para el aprendizaje de las tecnologías (Luckin & al., 2009). El andamiaje de experiencias educativas con medios sociales podría ayudar a cambiar actitudes y creencias hacia posiciones más favorables. Sin embargo, a pesar de que la mayoría de estudiantes en ambos contextos indican que vieron el potencial educativo en Twitter, todavía había algunos que se mantuvieron escépticos. En nuestra muestra, los datos mostraron que los estudiantes en España usaron principalmente Twitter para propósitos académicos por primera vez durante el semestre de nuestra investigación, mientras que más participantes estadounidenses habían participado anteriormente en usos académicos de Twitter.

Nuestra investigación se alinea con estudios previos que han sugerido la capacidad de Twitter para impactar en el aprendizaje de los estudiantes, especialmente en términos de habilidades para la colaboración, participación, la implicación y resultados del aprendizaje (Carpenter, 2014; Junco, Heiberger, & Loken, 2011; Junco, Elavsky, & Heiberger, 2013; KassensNoor, 2012; West, Moore, & Barry, 2015). Con el objetivo de explorar aspectos particulares de este impacto, esta investigación actual ha observado que Twitter ha involucrado principalmente a los estudiantes en compartir y encontrar recursos, debatiendo, comunicando y reflexionando. Los datos cualitativos confirman este impacto, con muchos de los estudiantes haciendo notar su sorpresa con respecto al valor educativo de estas actividades. Es más, los pocos comentarios en España acerca del seguimiento de hashtags externos son coherentes con el bajo porcentaje alcanzado por temas relacionados con discusiones externas. Además, las reflexiones escritas por los estudiantes en ambos países señalan el impacto potencialmente abrumador del acceso a tanta información, lo cual coincide con las conclusiones de Davis (2015). Teniendo en cuenta los principales usos educativos de Twitter definidos en la investigación anterior (Shah, Shabgahi, & Cox, 2015), parece que los estudiantes han observado el impacto de Twitter para el aprendizaje formal y colaborativo y la reflexión, y se necesitaría trabajar más para mejorar también el aprendizaje informal y móvil.

Al comparar las experiencias de los participantes de España y los EE.UU., el contexto americano parecía ser en el que mayor presencia de chats y hashtags crearon más oportunidades para las interacciones con Twitter que eran atractivas para los participantes. VanDijck (2011) señaló que Twitter se puede utilizar en una variedad de maneras; mientras que los chats en EE.UU. pueden haber permitido a los participantes usar Twitter más como una herramienta de comunicación bidireccional, el uso menos frecuente de chats y hashtag por los participantes españoles puede haber definido a Twitter como una herramienta de intercambio de información y recursos. Aunque tal participación puede valer la pena, puede ser una razón menos convincente para que los futuros maestros utilicen Twitter si ya están acostumbrados a acceder a medios más tradicionales para la adquisición de información. En lugar de identificar diferencias en general de las culturas monolíticas de EE.UU. y España que afectaron la percepción de Twitter por parte de los participantes, nuestros hallazgos parecen sugerir que las diferencias en la práctica en línea asociada a como las tecnologías se emplean en diferentes países o regiones pueden influir en las percepciones y usos de la tecnología. Aunque las culturas fuera de línea probablemente influyen en los comportamientos en línea en muchos casos, puede que no siempre exista una relación causal unidireccional.

Las implementaciones futuras de actividades educativas con Twitter deberían explorar las posibilidades de dos estimulantes líneas de investigación. En primer lugar, la colaboración internacional entre los estudiantes podría ser una interesante nueva interacción, ya que existe evidencia de que el uso interactivo de Internet está relacionado con un superior logro académico (TorresDíaz, Duart, GómezAlvarado, MarínGutiérrez, & SegarraFaggioni, 2016). En segundo lugar, cómo las aplicaciones educativas de Twitter pueden contribuir al desarrollo de habilidades de pensamiento de alto nivel cognitivo parece ser un área digna de exploración.

Este estudio está limitado por el muestreo de conveniencia, que dio lugar a diferentes tamaños de grupo en dos países diferentes. Sin embargo, nuestros hallazgos ofrecen un primer paso en la investigación en la que el desafiante y prometedor enfoque es el impacto en el aprendizaje que Twitter puede tener en diferentes contextos académicos. Antes de que la investigación futura pueda comparar el contexto de aprendizaje en mayor profundidad, se necesitaba algún conocimiento previo sobre el uso general y percepciones. Así, a partir de ahora, otros estudios comparativos pueden explorar los matices del impacto de Twitter observado en este estudio. Se necesitan trabajos futuros para promover el uso educativo de los medios sociales para las habilidades cognitivas de alto nivel, como la reflexión, las habilidades de pensamiento crítico y el aprendizaje autorregulado, como sugieren investigaciones recientes (Herro, 2014; Matzat & Vrieling, 2015) y explorar las posibles diferencias en términos de edad y género. Por último, dado que los factores culturales pueden afectar el uso de los medios sociales (Carpenter, Tur, & Marín, 2016), las nuevas investigaciones podrían abordar el uso de Twitter en términos de diferencias culturales de dos maneras principales: por un lado, las normas sociales y la ansiedad (Heinrichs & al., 2006) podrían influir en el comportamiento de los estudiantes en Twitter; por otro lado, centrándose en el sistema educativo, cómo las diferencias culturales en los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje –ver, por ejemplo, el modelo de las cuatro dimensiones (Hofstede, 1986)– podrían influir en los usos y percepciones de Twitter y de los medios sociales en general. Del mismo modo, dado que se ha constatado un proceso de americanización del sistema educativo español (Lalueza & Collell, 2013), sería interesante explorar cómo Twitter está contribuyendo a este fenómeno.

Referencias

Adnan, M., Leak, A., & Longleya, P. (2014). A Geocomputational Analysis of Twitter Activity around Different World Cities. Geo-spatial Information Science, 17(3), 145-152. https://doi.org/10.1080/10095020.2014.941316

Amichai-Hamburger, Y., & Hayat, Z. (2011). The Impact of the Internet on the Social Lives of Users: A Representative Sample from 13 Countries. Computers in Human Behavior, 27, 585-589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.10.009

Area, M., Alonso, C., Correa, J.M., del-Moral, M.E., de-Pablos, J., Paredes, J., Peirats, J., Sanabri, A.L., San-Martín, A., & Valverde, J. (2014). Las políticas educativas TIC en Espan~a después del Programa Escuela 2.0: Las tendencias que emergen. Relatec, 13(2), 11-33. https://doi.org/10.17398/1695-288X.13.2.11

Basilotta, V., & Herrada, G. (2013). Aprendizaje a través de proyectos colaborativos con TIC. Análisis de dos experiencias en el contexto educativo. Edutec, 44. (https://goo.gl/CwdssM) (2016-10-10).

Carpenter, J.P. (2014). Twitter's Capacity to Support Collaborative Learning. International Journal of Social Media and Interactive Learning Environments, 2(2), 103-118. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSMILE.2014.063384

Carpenter, J.P., & Krutka, D.G. (2014a). How and Why Educators Use Twitter: A Survey of the Field. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 46(4), 414-434. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2014.925701

Carpenter, J.P., & Krutka, D.G. (2014b). Chat it Up: Everything you Wanted to Know about Twitter Chats but Were Afraid to Ask. Learning and Leading with Technology, 41(5), 10-15. (https://goo.gl/zptefV) (2016-10-10).

Carpenter, J.P., & Krutka, D.G. (2015). Engagement through Microblogging: Educator Professional Development via Twitter. Professional Development in Education, 41(4), 707-728. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2014.939294

Carpenter, J.P., Tur, G., & Marín, V.I. (2016). What do USA and Spanish Pre-service Teachers Think about Educational and Professional use of Twitter? A Comparative Study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 131-143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.08.011

Castañeda, L., Costa, C., & Torres-Kompen, R. (2011). The Madhouse of Ideas: Stories about Networking and Learning with Twitter. Conference 2011, Southampton, UK. (https://goo.gl/BWtO5L) (2016-10-10).

Correa, J., Losada, D., & Fernández, L. (2012). Polí´ticas educativas y prácticas escolares de integracio´n de las tecnologías en las escuelas del País Vasco: Voces y cuestiones emergentes. Campus Virtuales, 1(1), 21-30. (https://goo.gl/szxG2K) (2016-10-10).

Davis, K. (2015). Teachers’ Perceptions of Twitter for Professional Development. Disability and Rehabilitation, 37(17), 1551-1558. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1052576

De-Paoli, S., & Larooy, A. (2015). Teaching with Twitter: Reflections on Practices, Opportunities and Problems. Paper in EUNIS 2015, Dundee, Scotland (UK), 10-12 June. (https://goo.gl/tqxx0h) (2016-10-10).

Domenech, M. (2015). Completamente quijotizados. La rebotica de literlengua. [Web log post]. (https://goo.gl/J8BTjt) (2016-10-10).

Ertmer, P.A., & Ottenbreit-Letwich, A. (2013). Removing Obstacles to the Pedagogical Changes Required by Jonassen’s Vision of Authentic-enabled Learning. Computers & Education, 64, 175-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.008

Heinrichs, N., Rapee, R.M., Alden, L.A., Bögels, S., Hofmann, S.G., Oh, K.J., & Sakano, Y. (2006). Cultural Differences in Perceived Social Norms and Social Anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(8), 1187-1197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.09.006

Hermans, R., Tondeur, J., Van-Braak, J., & Valcke, M. (2008). The Impact of Primary School Teachers’ Educational Beliefs on the Classroom Use of Computers. Computers & Education, 51, 1499-1509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2008.02.001

Herro, D. (2014). Techno Savvy: A Web 2.0 Curriculum Encouraging Critical Thinking. Educational Media International, 51(4), 259-277. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2014.977069

Hofstede, G. (1986). Cultural Differences in Teaching and Learning. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 10(3), 301-320. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(86)90015-5

Hunter, J.D., & Caraway, H.J. (2014). Urban Youth Use Twitter to Transform Learning and Engagement. The English Journal, 103(4), 76-82. (https://goo.gl/xFZA9h) (2016-10-10).

Jackson, L., & Wang, J.L. (2013). Cultural Differences in Social Networking Site Use: A Comparative Study of China and the United States. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 910-921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.024

Junco, R., Elavsky, M.C., & Heiberger, G. (2013). Putting Twitter to the Test: Assessing Outcomes for Student Collaboration, Engagement and Success. British Journal of Education Technology, 44(2), 273-287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467- 8535.2012.01284.x

Junco, R., Heiberger, G., & Loken, E. (2011). The Effect of Twitter on College Student Engagement and Grades. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 27(2), 119-132. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2729.2010.00387.x

Kassens-Noor, E. (2012). Twitter as a Teaching Practice to Enhance Active and Informal Learning in Higher Education: The Case of Sustainable Tweets. Active Learning in Higher Education, 13(1), 9-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787411429190

Ku, Y.C., Chen, R., & Zhang, H. (2013). Why do Users Continue Using Social Networking Sites? An Exploratory Study of Members in the United States and Taiwan. Information & Management, 50, 571-581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2013.07.011

Kurtz, J. (2009). Twittering about learning: Using Twitter in an Elementary School Classroom. Horace, 25(1), 1-4. (https://goo.gl/QhALU2) (2016-10-10).

Lalueza, F., & Collell, M.R. (2013). Globalization or Americanization of Spanish Higher Education? A Comparative Case Study of Required Skills in the Higher Education Systems of the United States and Spain. Razón y Palabra, 17(4-85). (https://goo.gl/2A54Df) (2016-10-10).

Lu, A. (2011). Twitter Seen Evolving into Professional Development Tool. Education Week, 30(36), 20. (https://goo.gl/jA70Ho) (2016-10-10).

Luckin, R., Clark., W., Graber, R., Logan, K., Mee, A., & Oliver, M. (2009). Do Web 2.0 Tools really Open the Door to Learning? Practices, Perceptions and Profiles of 11-16 year-old Students. Learning, Media and Technology, 34(2), 87-104. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439880902921949

Marín, V.I., & Tur, G. (2014). Student Teachers’ Attitude towards Twitter for Educational Aims. Open Praxis, 6(3), 275-285. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.6.3.125

Marín, V.I., Negre, F., & Pérez-Garcias, A. (2014). Entornos y redes personales de aprendizaje (PLEPLN) para el aprendizaje colaborativo [Construction of the Foundations of the PLE and PLN for Collaborative Learning]. Comunicar, 42, 35-43. https://doi.org/10.3916/C42-2014-03

Matzat, U., & Vrieling, E.M. (2015). Self-regulated Learning and Social Media - A ‘Natural Alliance’? Evidence on Students’ Self-regulation of Learning, Social Media Use, and Student-teacher Relationship. Learning, Media and Technology, 41(1), 73-99. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2015.1064953

Mercier, E., Rattray, J., & Lavery, J. (2015). Twitter in the Collaborative Classroom: Micro-blogging for In-class Collaborative Discussions. International Journal of Social Media and Interactive Learning Environments, 3(2), 83-99. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSMILE.2015.070764

Molina, A. (2011). El Lazarillo de Tormes en Twitter. Plataforma Educa. [Web log post]. (https://goo.gl/Zn9QB4) (2016-10-10).

Muñoz, F. (2012). Experiencias didácticas con Twitter. Educa con TIC. [Blogpost]. (https://goo.gl/UPgyVk) (2016-10-10).

Nowell, S.D. (2014). Using Disruptive Technologies to make Digital Connections: Stories of Media Use and Digital Literacy in Secondary Classrooms. Educational Media International, 51(2), 109-123. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2014.924661

Salinas, J. (2013). Enseñanza flexible y aprendizaje abierto, fundamentos clave de los PLEs. In L. Castañeda, & J. Adell (Eds.), Entornos personales de aprendizaje: Claves para el ecosistema educativo en Red (pp. 53-70). Alcoy: Marfil.

Shah, N.A.K., Shabgahi, S.L., & Cox, A.M. (2015). Uses and Risks of Microblogging in Organisational and Educational Settings. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(6), 1168-1182. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12296

Shirky, C. (2011). Political Power of SocialMedia : Technology, the Public Sphere, and Political Change. Foreign Affairs, 90(1), 28-41. (https://goo.gl/1Th2FL) (2016-10-10).

Teo, T. (2009). Modelling Technology Acceptance in Education: A Study of Pre-service Teachers. Computers & Education, 52(2), 302-312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2008.08.006

Theocharis, Y., Lowe., W., Van-Deth, J.W., & García-Albacete, G. (2015). Using Twitter to Mobilize Protest Action: Online Mobilization Patterns and Action Repertoires in the Occupy Wall Street, Indignados, and Aganaktismenoi movements. Information, Communication & Society, 18(2), 202-220. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/1369118X.2014.948035

Tirado-Morueta, R., & Aguaded, I. (2014). Influencias de las creencias del profesorado sobre el uso de la tecnología en el aula. Revista de Educación, 363, 230-255. https://doi.org/10-4438/1988-592X-RE-2012-363-179

Torres-Díaz, J.C, Duart, J.M., Gómez-Alvarado, H.F., Marín-Gutiérrez, I., & Segarra-Faggioni, V. (2016). Internet Use and Academic Success in University Students. [Usos de Internet y éxito académico en estudiantes universitarios]. Comunicar, 48(24), 61-70. https://doi.org/10.3916/C48-2016-06

Tur, G., & Marín, V.I. (2015). Enhancing Learning with the SocialMedia : Student Teachers’ Perceptions on Twitter in a Debate Activity. New Approaches in Educational Research, 4(1), 46-53. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2015.1.102

Van-Dijck, J. (2011). Tracing Twitter: The Rise of a Microblogging Platform. International Journal of Media and Cultural Politics, 7(3), 333-348. https://doi.org/10.1386/macp.7.3.333_1

Wesely, P.M. (2013). Investigating the Community of Practice of World Language Educators on Twitter. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(4), 305-318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487113489032

West, B., Moore, H., & Barry, B. (2015). Beyond the Tweet: Using Twitter to Enhance Engagement, Learning, and Success among First-year Students. Journal of Marketing Education, 37(3), 160-170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475315586061

Document information