Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Resumen

This paper presents an exploratory study to examine the practices of outstanding primary school teachers in their professional development for ICT integration in teaching and learning, as a means of understanding how their learning ecologies develop and function. Outstanding teachers in the context of this study are teachers who innovate pedagogically and who are influential in the community, having successfully developed their learning ecology. Using a qualitative approach, we explore the concept of learning ecologies as a driver for innovation in the professional development of teachers, using a carefully selected sample of nine outstanding teachers. Drawing from in-depth interviews, specific coding and NVIVO analysis, our results show that these teachers develop organized systems for activities, relationships and resource usage and production, which can be characterized as the components of their professional learning ecology, to continuously keep up to date. We also identified some characteristics of teachers that perform outstandingly and factors that potentially facilitate or hinder their learning ecology development. Further research in the field will enable an improved understanding of the professional learning ecologies of school teachers and support future interventions and recommendations for professional development through the cultivation of emerging professional learning ecologies.

Resumen

Este artículo presenta un estudio exploratorio que examina prácticas de docentes referentes de Educación Primaria en su desarrollo profesional sobre la integración de las TIC en la docencia y el aprendizaje como medio para comprender el desarrollo y operación de sus ecologías de aprendizaje. Un docente referente en el contexto de este estudio es aquel que innova pedagógicamente y que influye en la comunidad, habiendo desarrollado con éxito su ecología de aprendizaje. Mediante un enfoque cualitativo, se explora el concepto de ecologías de aprendizaje como motor de la innovación en el desarrollo profesional de los docentes, utilizando una muestra cuidadosamente seleccionada de nueve profesores de Educación Primaria. A partir de entrevistas en profundidad, codificación específica y análisis con NVivo, los resultados muestran que estos docentes desarrollan sistemas organizados de actividades, relaciones y recursos, que pueden ser caracterizados como componentes de sus ecologías de aprendizaje para mantenerse permanentemente actualizados. Se identifican algunas de las características y factores que potencialmente facilitan u obstaculizan el desarrollo de su ecología de aprendizaje. Futuras investigaciones en esta línea permitirán mejorar nuestra comprensión de las ecologías de aprendizaje profesional de los docentes, apoyando nuevas futuras intervenciones y recomendaciones para el desarrollo profesional.

Keywords

Learning ecologies, teachers’ professional development, primary school education, outstanding teachers, ICT, case studies, influencing factors, training

Palabras clave

Ecologías de aprendizaje, desarrollo profesional docente, educación primaria, docentes referentes, TIC, casos de estudio, factores influyentes, formación

Introduction

Teachers play a key role in the integration and effective use of technology in education (Uluyol & Şahin, 2016), and while most primary school teachers recognize the potential of digital technologies and the internet (Admiraal & al., 2017; Correa & Martínez, 2010; De-Jesús & Lebres, 2013; Potter & Rockinson-Szapkiw, 2012), implementation remains limited (Correa & Martínez, 2010; De-Jesús & Lebres, 2013) and technology at school unused (Potter & Rockinson-Szapkiw, 2012).

A survey of adult skills (OECD, 2016), reveals that 87% of teachers (pre-primary, primary and secondary) consider that they have the computer skills needed in their job. The difficulty, then, lies in the lack of skills to use technologies for educational purposes (De-Jesús & Lebres, 2013). The well-known Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) theory considers pedagogical and disciplinary knowledge applied to technology to be fundamental, and points to the many ways in which techno-pedagogical knowledge can be developed. This theory arose precisely from research into the difficulties encountered by teachers in applying technology to education (Harris, Mishra, & Koehler, 2009; Koehler & Mishra, 2009). The same difficulties led to the development of the Digital Competence for Educators (DigCompEdu) framework (Redecker & Punie, 2017), which attempts to support technology integration in pedagogical practices and in so doing develop the digital competence of students.

Teachers may face difficulties related to insufficient training, the lack of suitable equipment or a lack of flexibility in the curriculum (Nikolopoulou & Gialamas, 2015; Panagiotis & al., 2011; Unal & Ozturk, 2012). Teachers’ attitudes towards technology are conditioned by the resources available to them, the support that they receive and the existence of a motivational school culture (Agyei & Voogt, 2014; Uluyol & Şahin, 2016).

One of the most important challenges in techno-pedagogical uptake by teachers is promoting effective professional development strategies. The literature suggests that most continuing professional development currently focuses on administrative and institutional aspects, leaving teachers feeling powerless in their own professional development (Jiménez, 2007). A proposed alternative is the empowerment of teachers through a more consensual definition of their professional development (Livingston & Robertson, 2010) and the incorporation of collaborative practices (Kennedy, 2011) and peer-group mentoring (Geeraerts & al., 2015). Another successful innovation is collegial practice transfers, consisting of more experienced teachers instructing less experienced teachers (Lakkala & Ilomäki, 2015). Mentoring has, in fact, been identified as a key factor in the success of in-service teacher training (Dorner & Kárpáti, 2010), as peers can provide both practical and emotional support.

In spite of advances, teachers’ professional training is essentially based on (more or less innovative) approaches that are frequently kept separate and that tend to focus on the trainer/coach/coordinator’s perspective of learning achievements (Bradshaw, Walsh, & Twining, 2011; Laurillard, 2014; Twining, Raffaghelli, Albion, & Knezek, 2013). However, a more integrated learner-centred perspective is crucial to nurturing teachers’ confidence in their own capacity to integrate ICT innovations into teaching (Tondeur, Forkosh-Baruch, Prestridge, Albion, & Edirisinghe, 2016). Below we describe the concept of learning ecologies (LE) as a driver of innovation in the professional development of teachers.

Since the 1990s, ecological approaches to teaching and learning in the digital age have yielded a range of terms and conceptual definitions that have come to be widely used (Sangrà, Raffaghelli, & Guitert, 2019). The term LE has been used in many fields of education, including technologies and gender (Barron, 2004), ICT skills development (Barron, 2006), collaborative learning (Hodgson & Spours, 2009), designs for learning with technologies (Luckin, 2010), learning resources for homeless populations (Strohmayer, Comber, & Balaam, 2015), teachers’ professional development (Sangrà, González-Sanmamed & Guitert, 2013; Van-den Beemt & Diepstraten, 2016) as well as personalized learning and lifelong learning (Maina & García, 2016).

Jackson (2011) has further explored the construct of LE, introducing the useful concept of lifewide learning, given that LE embrace many different spaces and types of learning. The concept of LE, therefore, emphasizes a learner-centred and self-determined perspective, which is particularly important for professional development and is particularly applicable to the professional development of teachers. Van-Den-Beemt & Diepstraten (2016) studied the LE of teachers starting to use ICTs, particularly their assumptions and expectations, and the contexts and key people that encouraged their learning conceived as a horizontal process among a plurality of spaces (Akkerman & Van-Eijck, 2013).

The advent of digital environments has generated another important dimension of analysis for the learning ecology concept, namely, the selection of, and engagement with, more or less digital or analogue/physical learning contexts. While this aspect was envisaged in foundational work by Barron (2004), it emerged sharply in Delphi studies as a lens to characterize LE (González-Sanmamed, Muñoz-Carril, & Santos-Caamaño, 2019).

The above considerations are relevant in recognizing that, while most learning ecology studies attempt to analyse ongoing experiences and practices, few support strategies for professional development (Sangrà, Raffaghelli, & Guitert, 2019). Therefore, and considering the ongoing debate on the need to improve the effectiveness in teachers’ professional development, it seemed particularly appropriate to research lifelong LE in primary teachers in an endeavour to support future research, strategies, interventions and recommendations for professional development based on cultivating professional LE.

Methodology

Qualitative methods allow deep exploration of emergent discourses and practices. They therefore attempt to grasp the complexity of experiential knowledge, while avoiding the limitations and synthesis required of quantitative methods. Although qualitative methods do not allow the study of causality or the generalization of research results, they do encompass very rich descriptions where emerging new patterns can support further exploration (Ingleby, 2012).

This study aimed to explore outstanding practices in self-directed professional development for ICT integration in teaching and learning, as a means to understanding how successful LE develop and function. In this context, outstanding teachers are understood as those that pioneer pedagogical innovations and are usually influential to others, effectively organizing their self-directed professional development. We conducted an in-depth analysis of a sample of primary school teachers, as a follow-up to an initial phase of expert consultation by means of a Delphi study (Romero, Guàrdia, Guitert, & Sangrà, 2014). The research questions addressed in this study were as follows:

- RQ1: What components shape the professional LE of outstanding primary school teachers?

- RQ2: What other factors influence the development and the maintenance of these teachers’ LE?

Data collection: Case selection and interview structure

The outstanding teachers were teachers who demonstrated on-going technology uptake regarding both their classrooms and their own professional development.

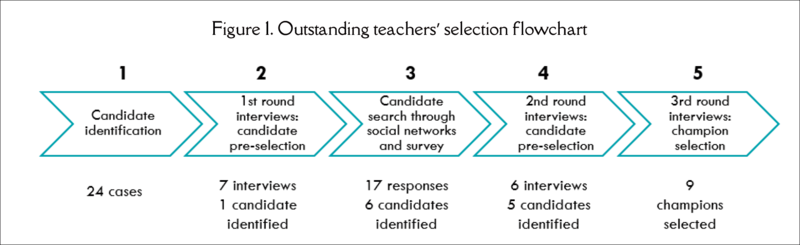

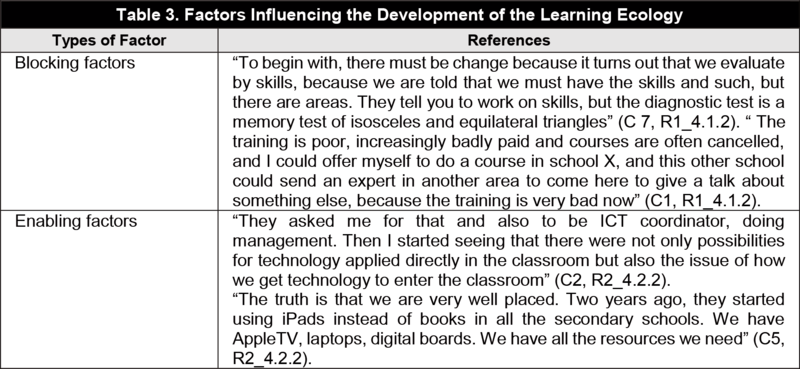

Nine teachers were ultimately selected from an initial sample of 24 candidates, in the five-phase process illustrated in Figure 1.

|

|

The sample was drawn from in-service primary school teachers in Catalonia (Spain). The initial criterion for inclusion was varied professional experience. The remaining broad inclusion criteria for outstanding participants were as follows:

1) They use a set of reliable relationships and resources that enable them to update continuously.

2) They use ICTs to develop their own LE for professional development.

3) They have developed a learning ecology that positively impacts their professional practice.

Those broad criteria were further refined to establish more specific characteristics for these teachers, as follows:

a) They are active in social networks, i.e., they: Participate in two or three social networks; articipate in distribution lists; Make frequent use of both networks and lists.

b) They are interested in innovation, i.e., they: have co-authored a publication: Have received an award; Have participated in an innovation project.

c) They use ICTs in the classroom, i.e., they: Use ICTs as a support or as a complement; Prepare teaching materials or resources using (reusing) materials found in the Internet.

Of the nine selected teachers, three had been teaching for less than 10 years, three between 11 and 20 years, and the last three for more than 20 years.

Three data collection methods were combined: interviews, materials and other products related to the teachers’ activities. Our qualitative approach to the analysis of the case studies was based on in-depth interviews as the data collection instrument, using NVIVO software for specific coding and analysis.

Coding and analysis

Observations of internet and social media practices were triangulated with data collected from interviews, with the resulting textual data constituting our corpus for analysis.

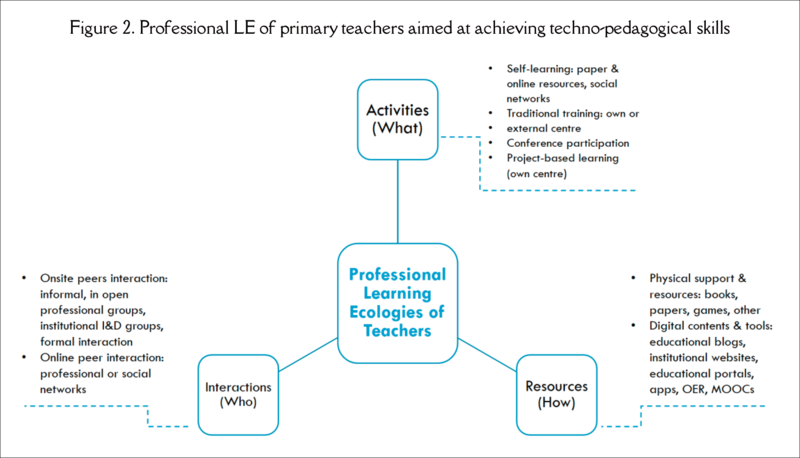

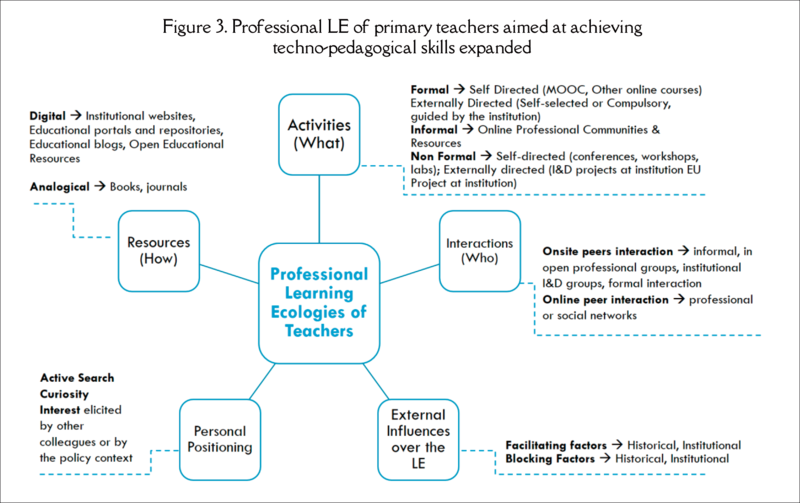

The qualitative analysis was done using NVIVO. The interviews with the nine teachers were coded on the basis of a thematic analysis, with categories and codes theoretically driven by the Delphi study- as shown in the conceptual map depicted in Figure 2: Undertaken in the previous research phase (Romero, Guàrdia, Guitert, & Sangrà, 2014). In this follow-up study we attempted to further elaborate on this map by identifying specific components explaining the drivers motivating teachers to undertake certain activities, strengthen certain interactions and use certain resources in their personal and professional learning contexts.

|

|

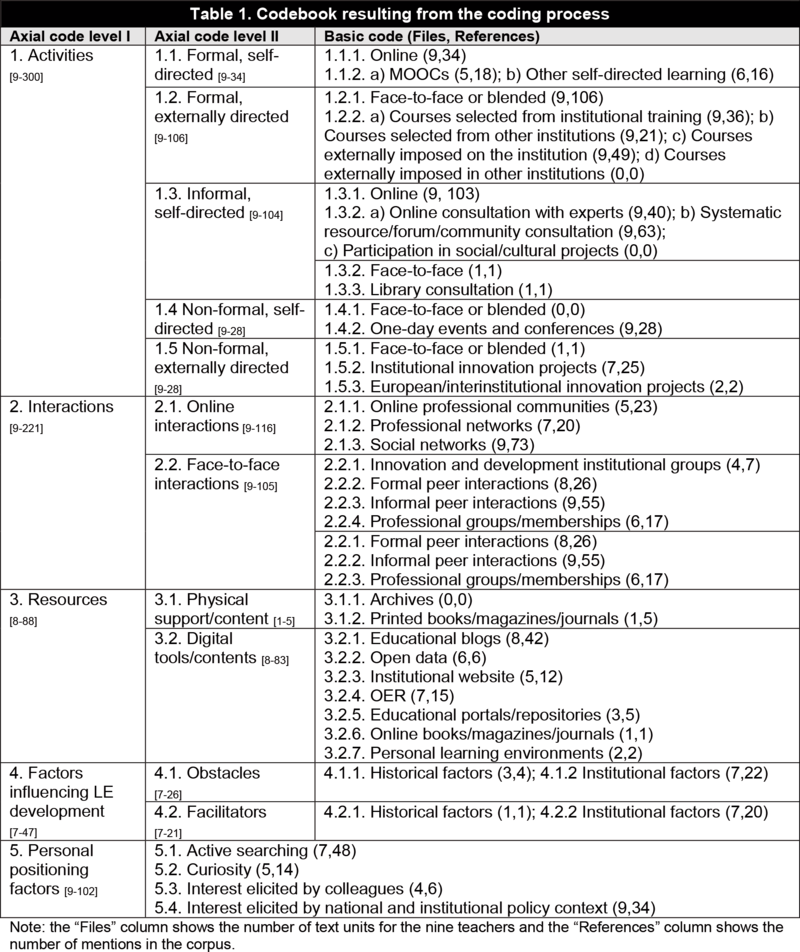

To obtain a final codebook of axial and basic codes from the inductive research (Table 1), four researchers agreed on the coding strategy and two researchers coded the corpus. The percentage of interrater agreement was 99% for all the codes, for a kappa coefficient of 0.68 (considered an acceptable level of agreement). During the coding process, as well as the three main learning ecology components of activities, interactions and resources, we detected relevant emerging factors related to drivers behind learning ecology growth and maintenance, which we labelled personal positioning and factors influencing learning ecology development.

|

|

Results and analysis

Our results are described considering the three main learning ecology components, namely, activities, interactions and resources, and also considering the two additional factors that emerged during the coding process: personal positioning and factors influencing learning ecology development.

Characterizing the LE of outstanding teachers

A great diversity of approaches was found throughout the nine cases. As shown on Table 1, there was a great concentration of specific elements across teachers. For example, while all nine teachers participate in formal activities online and face-to-face, only six participate in self-directed activities, and only five have taken massive open online courses (MOOCs). In general, following an established pattern, more diversity is observed for self-directed activities than for externally directed activities proposed at the national or institutional level.

Activities

Regarding which activities the teachers carry out, great discursive density is observed in relation to participation in courses (106 of 302 corpus references), which also offer the opportunity to establish professional networks. The dynamics usually coincide: from face-to-face or online interactions, teachers become followers or friends in social networks. The courses taken vary greatly, from those offered by the centre, MOOCs, etc., but uptake is greater for external and face-to-face courses.

Many teachers opt for formal education, mostly university-based face-to-face or online courses: “I’ve been looking into TDH courses. And we were looking there the other day and said we should do one. They are courses offered by the centre... We’re beginning to get around to it, since we have to start doing this kind of face-to-face thing” (C5, R1_1.2.1b). “One of the reasons for doing the master’s in educational innovation was to do that, to learn about and enter the world of people who train and learn how to build training” (C2, R2_1.2.1b).

However, others show a preference for informal and more practical channels: “One of the things I also like to do is to easily access people that I consider referents, without bothering them. I do not have to ask them anything. They are generous in that, once a week or month, they offer their opinions, and I like to hear them, without having to go to where these people give talks” (C1, R1-2_1.3.1a).

Regarding face-to-face activities, it is important to note the attendance to one-day events and conferences as well as informal interactions with colleagues and interns in schools, considered important channels for knowledge updates. Outstanding teachers seem to prefer face-to-face activities, whether formal or informal, that take place in their centre: “Last year together with two other people we presented an innovation project on ideas as to how we could introduce tablets in infants’ school, and that took a year, spending just a few hours at a time” (C2, R1-2_1.5.2).

However, specific consideration needs to be given to their participation in informal and self-directed activities. As mentioned above, teachers typically begin with formal activities, and then continue along an informal route that is no longer directed externally but which is managed by the teacher in a process of questioning, demonstrating or sharing professional practices: “That gives you the chance to go to a conference or a talk. Then, of course, you meet people. Through JA, for instance, I found AR, and I had the opportunity to listen to him, he’s just something else. And DR came to give us a talk at the school” (C3, R1_1.4.1a).

Interactions

In regard to the personal and professional relationships established by the outstanding teachers, their online interactions focus on seeking information and comparing ideas, knowledge, etc. Social network use is noteworthy, either active (participation) or passive (consultation), and visits to blogs maintained by referents: “I am not into social networks that much, I mean, I’m not very active in social networks, I use them for instance to ask questions, you know? That side I haven’t exploited much, I have been more of a passive participant” (C1, R1_2.1.3).

Regarding social networks, Twitter is the most used, for a variety of reasons: to be up-to-date with information from colleagues and referents, to seek specific information, to search, consult and obtain information on a daily basis, to follow referents and colleagues from one’s own and other centres, to share resources, information and personal reflections, to draw attention to published works, to request help, information, etc., and to generally keep up to date with both face-to-face and online courses.

Nonetheless, while all the teachers have a Twitter account, they tend to be moderate users in that they do not post or they only post sporadically. Their use of Twitter is often just for convenience sake and they do not consider themselves to be referents: “Twitter, maybe not, but it’s a great source. If you become a fan of people who are good, for instance, PPL, then many alerts come to you on things that probably you would never have known. Twitter, I think is very handy, you take a look and you say ‘ah, look at that’, and then you search in depth” (C5, R3_2.1.3).

Regarding Facebook, far less popular among these teachers, use is fundamentally personal; typically, the account was initially established for either personal or professional use and, in the latter case, the teacher progressively began to make it more personal and to share information or reflections with and by colleagues: “What happens is that with Facebook I have come to use it in a way that is more personal whereas I’ve used Twitter more professionally. There was a time when I was a ‘100% professional of Facebook’. What happened? Well, of course, there I have friends and, in the end, they give up on you... they get tired. I understand that and I have also stopped to tell myself ‘let me organize my social life’” (C3, R2-3_2.1.3).

Another network that is used sporadically, is LinkedIn (C7, C3), a professional network, for the purpose of posting career resumés online and establishing professional contacts. Less frequently, SlideShare, Keynote and Prezi are adopted to access referents’ presentations (C4, C9) or to share presentations. While these tools are for public use, in some cases the teachers share presentations internally with colleagues (C9), e.g., Ning to monitor forums, Evernote to store information in an orderly way for consultation and analysis, and Pinterest to manage projects and to seek new ideas.

In sum, interactions are distributed homogeneously between face-to-face interactions and online interactions (106 of 302 and 116 of 300 corpus references, respectively). Face-to-face interaction is used for dialogue and collaboration during educational intervention projects or routine practice, whereas online interactions have the advantage of synchrony. All in all, forms of knowledge exchange are established, that allow these teachers to complete, integrate and build their repertoire of professional teaching strategies. Teachers, in this sense, are both receivers and senders, investing, in both cases, cognitive efforts to complete their knowledge through vicarious learning (what others do) and reflective practice (what the teachers themselves do).

Resources

The outstanding teachers are featured by intense online activity, rarely using physical or printed media. Blogs maintained by educational influencers and for educational outreach purposes are the most frequently consulted resource (42 of 82 corpus references). These teachers access these blogs either through Twitter or by subscribing via an RSS feed, in this way, combining social network interactions with access to specific resources: “My usual routine is tracking blogs and Twitter. I have to admit that I did not understand how Twitter worked until a year ago. I’m much more one for blogs” (C1, R1_3.2.1).

However, they are not just passive receivers; some of them are bloggers themselves, whether of a personal blog, group blog or their centre blog. They post and share resources that reinforce specific aspects of educational practice, etc. In these cases, blog post frequency is typically weekly or fortnightly.

There is great variability in the type of resources used in addition to educational blogs, including, specifically, more obvious ones like the institutional website (12 of 83 corpus references), and open educational resources (OER) and open data (which together account for 21 of 83 corpus references).

Finally, in the performance of activities, in interactions and in accessing resources, these teachers mainly use smartphones, tablets and computers. Smartphones and tablets are generally used daily for consultations and for keeping up to date, while computers are reserved for tasks requiring greater interactivity, i.e., reading, research, writing, etc. Most outstanding teachers use commercial software, although some use open software for both their teaching and professional maintenance.

Factors influencing outstanding teachers’ development of LE

The interviews revealed a number of factors that intervene in how primary teachers configure and update their professional LE in terms of resources, activities and interactions. Two new factors, relating the prior Delphi study (Romero et al., 2014) were identified: personal positioning factors and factors influencing the learning ecology development, reflecting historical individual development and the institutional context.

Personal positioning factors

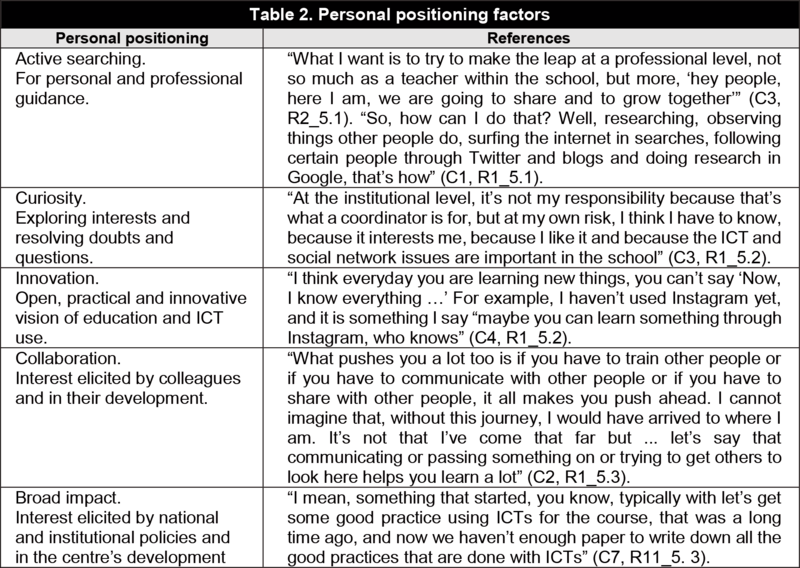

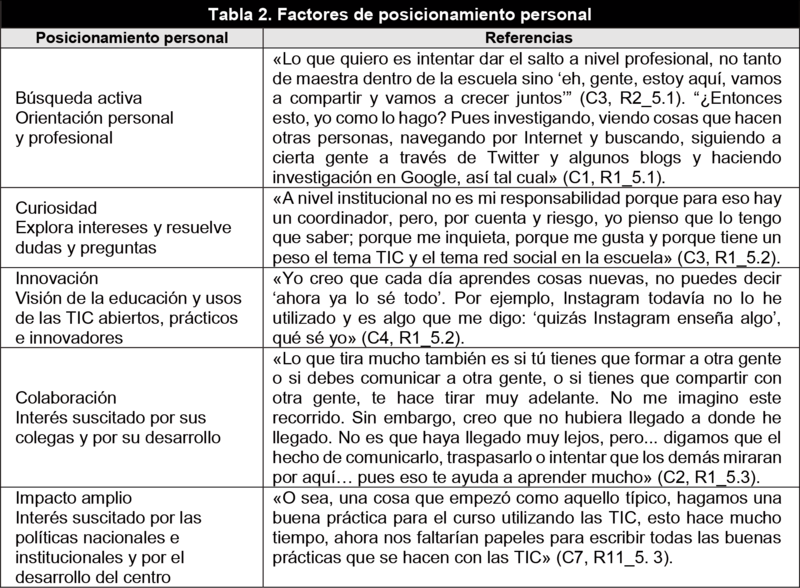

The personal positioning of outstanding teachers characterizes their productivity and success in applying technologies in the classroom, reflecting rapid and effective professional learning. Table 2 reproduces some of the comments of the interviewees regarding their personal positioning.

|

|

Evidently personal positioning reflects strong internal motivation to seek resources and establish personal and professional relationships that lead to formal, non-formal and informal learning. In particular, the semantic density in all the nine outstanding teachers’ discourse (34 of 102 corpus references) reveals their passion and curiosity, but also their high motivation to search for micro-contexts in their institution that allow the configuration of advanced practices.

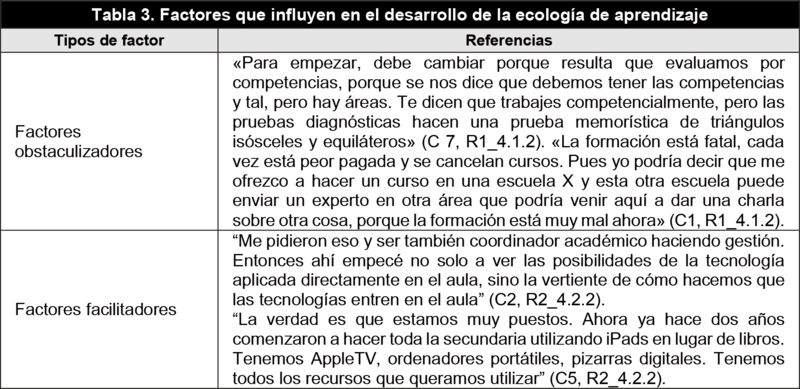

Factors influencing learning ecology development

The educational centres act as contexts where negative and positive historical and current aspects become facilitators or obstacles to the development of the learning ecology. Our analysis revealed the existence of training needs that go beyond institutional offerings, which explains why outstanding teachers tend to diversify their own training channels and activities.

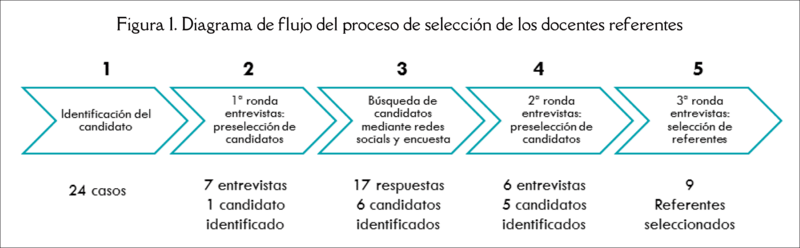

The semantic density in relation to this topic would suggest that all the participating outstanding teachers have similar perceptions regarding facilitators and obstacles (20 and 22 of 47 corpus references to facilitating and blocking factors, respectively). Although they mention historical factors, these are less frequent than current, contextual facilitators and obstacles. Negative aspects are generally more related to the national regulatory context than to specific centres, whereas, in relation to positive factors, the concrete actions that centres have set in motion to facilitate the autonomy of their outstanding teachers are noteworthy. Table 3 reproduces some of the comments of the interviewees on this topic.

|

|

Thus, despite strong historical and contextual constraints, these outstanding teachers generally find support in their centres for their autonomy, in the activation of courses requested by them, time off for training, the facilitation of regular meetings and of ICT projects, the establishment of minimum bases for ICT use, assignment of roles as experts (bring-your-own-device, robotics, programming skills), etc.

In sum, there is a continuous synergy between the characteristics of these teachers and their contexts that stimulate, support and promote their positive and proactive attitudes towards the integration of ICTs in the classroom. Cross-fertilization between teachers of ICTs and other project types (e.g., interdisciplinary approaches, empowered scientific and socio-cultural activities in the community, etc.) generates rich ecosystems in which the specific professional learning ecology finds fertile ground.

Discussion

Our results paint a rich picture of the potential LE of teachers within the specific domain of educational technologies in primary schools. However, a number of factors that support the development and maintenance of LE emerged in our analysis that represent a step further in the understanding of professional learning.

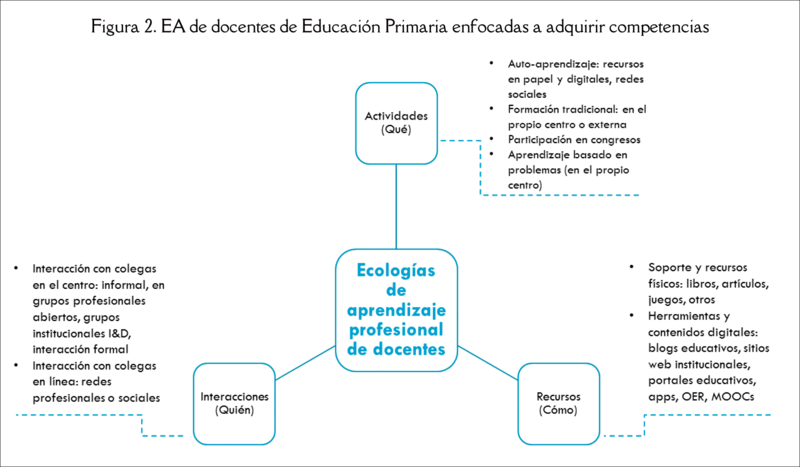

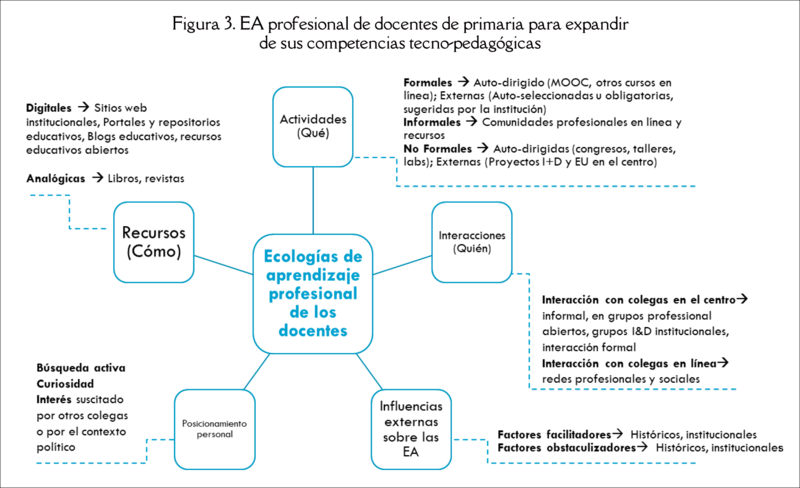

Previous learning ecology concepts have emphasized structure (activities, interactions and resources). Emerging from our interviews, however, were two additional factors without which LE could not be sustained: personal positioning factors and the historical and contextual factors influencing learning ecology development. In the first part of our analysis, we observed that professional learning tends to stem from formal activities and is mostly driven throughout on-site relationships with colleagues and participation in institutional projects. External factors, however, evidently function as motivational cues for outstanding teachers to pursue as a pathway to developing their professional skills, for instance, engagement with digital resources and informal online communications as a means for ensuring relationship continuity through social networks. There is an evident inner motivation in these teachers that leads them to connect the external world with an internal ideal picture of how their professional practice should unfold. This hypothesis is further supported by personal positioning factors as supportive of the learning ecology architecture of activities, interactions and resources. If this inner motivation -reflecting the personality and lived experiences of the learner- are in place, then the teacher builds on a spirit of curiosity and passion for innovation, the active search for connections and reflexive practice. Not only do they consult the work of others to shape their own practice, they also have a developmental vision of their own practice context that, in time, implies taking on board national and institutional policies and guidelines. The outline of their LE is represented in Figure 3, where the initial conceptual map (Fig.2) was reorganized and expanded based on the coded discourse of our nine teachers.

|

|

Conclusions

Our study may advance the re-conceptualization of the constituting components of LE. The qualitative approach through in-depth interviews purported an enriched picture of LE by reorganizing and expanding the semantic nodes within the initial conceptual map obtained through the Delphi study (Romero & al., 2014).

In addition, a further discussion, which sets the stage for future research, outlines the profiling of outstanding teachers. According to our exploration, these teachers are people who:

- Actively seek training opportunities, taking more “traditional” courses as formal face-to-face activities, proposed by the institution, but also following a number of informal, online activities;

- They continue to expand their opportunities to learn through informal interactions in professional communities, where they might play a crucial role as resource developers or curators;

- Not surprisingly, they are active blog readers, with blogs emerging as the main resources selected by them. This aligns with the idea of seeking influential people, whose ideas bring new light to everyday practice.

- As for the new LE components identified in our research, we observed the importance of personal positioning against the context, with teachers that actively engage in innovations, triggered by a high sense of curiosity. Moreover, they understand which facilitating factors exist in their contexts of practice and use them as springboards for their practice, against the deep understanding of reluctant forces in the field of professional practice.

A further inquiry of these outstanding profiles may shed light on micro-factors in the contexts of professional learning (external) or on the personal features which could be mirrored by others in search for positive technological uptake within pedagogical practices.

Our findings have implications for both innovations in professional development and applied research. They suggest the need to identify other potential outstanding teachers in order to explore their creativity as an expression of their personal positioning towards institutional development. The process of discovery and support may be time-consuming, but ultimately, the identification of these teachers could lead to a creative domino process whereby other teachers that are less effective in addressing innovation draw on outstanding teachers’ best practices. This approach could be explored through applied research into school management strategies, so that a common picture of the learning ecology structure could be generated through participatory meetings and raise awareness of the main components in model LE. Personal positioning and related factors could also be explored since, as has been emphasized in the professional self-regulated learning literature (Littlejohn, Milligan, & Margaryan, 2012), this type of self-awareness could also be the trigger for on-going development of individual professional learning approaches, with each teacher motivated to cultivate and enrich their own professional learning ecology. As for research, analyses of LE could progress to more systematic confirmatory studies using representative samples. Additional research could polish the model further and obtain some predictive insights into the factors influencing the development and configuration of LE. Moreover, design-based research could lead to the development of self-diagnostic tools to raise learners’ awareness of how to configure their own LE.

Our study has a number of limitations, the most important of which is that, despite a rigorous snowball sampling procedure, nine teachers represent a small universe of practice. Our configuration of LE could reflect elements that are not representative of primary school teachers. Nonetheless, the findings that characterize our outstanding teachers may help boost changes in their professional development. Therefore, our research, aimed at improving primary teachers’ professional development strategies and overall professional learning, can be considered exploratory, contributing to further understanding of lifelong LE.

References

- AdmiraalW, LouwsM, LockhorstD, PaasT, BuynstersM, CvikoA, KesterL, . 2017.in school-based technology innovations: A typology of their beliefs on teaching and technology&author=Admiraal&publication_year= Teachers in school-based technology innovations: A typology of their beliefs on teaching and technology.Computers & Education 114:57-68

- AgyeiD D, VoogtJ, . 2014.factors affecting beginning teachers’ transfer of learning of ICT-enhanced learning activities in their teaching practice&author=Agyei&publication_year= Examining factors affecting beginning teachers’ transfer of learning of ICT-enhanced learning activities in their teaching practice.Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 30(1):92-105

- AkkermanS F, Van-EijckM, . 2013.the student dialogically across and between boundaries of multiple communities&author=Akkerman&publication_year= Re-theorising the student dialogically across and between boundaries of multiple communities.British Educational Research Journal 39(1):60-72

- AttardM, ShanksR, . 2017.importance of environment for teacher professional learning in Malta and Scotland&author=Attard&publication_year= The importance of environment for teacher professional learning in Malta and Scotland.European Journal of Teacher Education 40(1):91-109

- BarronB, . 2004.ecologies for technological fluency: Gender and experience differences&author=Barron&publication_year= Learning ecologies for technological fluency: Gender and experience differences.Journal of Educational Computing Research 31(1):1-36

- BarronB, . 2006.and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: A learning ecology perspective&author=Barron&publication_year= Interest and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: A learning ecology perspective.Human Development 49(4):193-224

- BradshawP, WalshC, TwiningP, . 2011.Vital Programme: Transforming ICT professional development&author=Bradshaw&publication_year= The Vital Programme: Transforming ICT professional development.American Journal of Distance Education 26(2):74-85

- CorreaJ M, MartínezA, . 2010.¿Qué hacen las escuelas innovadoras con la tecnología?: Las TIC al servicio de la escuela y la comunidad en el Colegio Amara Berri.Teoría de la Educación 11(1):230-261

- De-JesúsR, LebresM L, . 2013.Colaboración online, formación del profesorado y TIC en el aula: Estudio de caso.Teoría de la Educación 14(3):277-301

- DornerH, KárpátiA, . 2010.for innovation: Key factors affecting participant satisfaction in the process of collaborative knowledge construction in teacher training&author=Dorner&publication_year= Mentoring for innovation: Key factors affecting participant satisfaction in the process of collaborative knowledge construction in teacher training.Online Learning 14:63-77

- GeeraertsK, TynjäläP, HeikkinenH L T, MarkkanenI, PennanenM, GijbelsD, . 2015.mentoring as a tool for teacher development&author=Geeraerts&publication_year= Peer-group mentoring as a tool for teacher development.European Journal of Teacher Education 38(3):358-377

- González-SanmamedM, Muñoz-CarrilP C, Santos-CaamañoF, . 2019.components of learning ecologies: A Delphi assessment&author=González-Sanmamed&publication_year= Key components of learning ecologies: A Delphi assessment.British Journal of Educational Technology 50(4):1639-1655

- HarrisJ, MishraP, KoehlerM, . 2009.technological pedagogical content knowledge and learning activity types: Curriculum-based technology integration reframed&author=Harris&publication_year= Teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge and learning activity types: Curriculum-based technology integration reframed.Journal of Research on Technology in Education 41(4):393-416

- HodgsonA, SpoursK, . 2015.ecological analysis of the dynamics of localities: A 14+ low opportunity progression equilibrium in action&author=Hodgson&publication_year= An ecological analysis of the dynamics of localities: A 14+ low opportunity progression equilibrium in action.Journal of Education and Work 28(1):24-43

- InglebyE, . 2012.methods in education&author=Ingleby&publication_year= Research methods in education.Professional Development in Education 38(3):507-509

- JacksonN, . 2011.for a complex world: A lifewide concept of learning, education and personal development&author=&publication_year= Learning for a complex world: A lifewide concept of learning, education and personal development. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse Publishing.

- JiménezB, . 2007.formación permanente que se realiza en los centros de apoyo al profesorado&author=Jiménez&publication_year= La formación permanente que se realiza en los centros de apoyo al profesorado.Educación XX1 10:159-178

- KennedyA, . 2011.continuing professional development (CPD) for teachers in Scotland: Aspirations, opportunities and barriers&author=Kennedy&publication_year= Collaborative continuing professional development (CPD) for teachers in Scotland: Aspirations, opportunities and barriers.European Journal of Teacher Education 34(1):25-41

- KoehlerM, MishraP, . 2009.What is technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)?Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education 9:60-70

- LakkalaM, IlomäkiL, . 2015.case study of developing ICT-supported pedagogy through a collegial practice transfer process&author=Lakkala&publication_year= A case study of developing ICT-supported pedagogy through a collegial practice transfer process.Computers & Education 90(1):1-12

- LaurillardD, . 2014. , ed. of a MOOC for Teacher CPD (UCL IOE)&author=&publication_year= Anatomy of a MOOC for Teacher CPD (UCL IOE).London: Institute of Education.

- LittlejohnA, MilliganC, MargaryanA, . 2012.collective knowledge: Supporting self-regulated learning in the workplace&author=Littlejohn&publication_year= Charting collective knowledge: Supporting self-regulated learning in the workplace.Journal of Workplace Learning 24(3):226-238

- LivingstonK, RobertsonJ, . 2001.coherent system and the empowered individual: Continuing professional development for teachers in Scotland&author=Livingston&publication_year= The coherent system and the empowered individual: Continuing professional development for teachers in Scotland.European Journal of Teacher Education 24(2):183-194

- LuckinR, . 2010. , ed. learning contexts: Technology-rich, learner-centred ecologies&author=&publication_year= Re-designing learning contexts: Technology-rich, learner-centred ecologies.London: Routledge.

- MainaM F, GonzálezI G, . 2016.personal pedagogies through learning ecologies&author=Maina&publication_year= Articulating personal pedagogies through learning ecologies.The future of ubiquitous learning.

- NikolopoulouK, GialamasV, . 2015.to the integration of computers in early childhood settings: Teacher’s perceptions&author=Nikolopoulou&publication_year= Barriers to the integration of computers in early childhood settings: Teacher’s perceptions.Education and Information Technologies 20(2):285-301

- OECD (Ed.). 2016.The survey of adult skills: Reader's companion.

- PanagiotisG, AdamantiosP, EfthymiosV, AdamosA, . 2011.and communication technologies (ICT) and in-service teachers’ training&author=Panagiotis&publication_year= Informatics and communication technologies (ICT) and in-service teachers’ training.Review of European Studies 3(1):2-12

- PotterS L, Rockinson-SzapkiwA J, . 2012.integration for instructional improvement: The impact of professional development&author=Potter&publication_year= Technology integration for instructional improvement: The impact of professional development.Performance Improvement 51(2):22-27

- RedeckerC, PunieY, . 2017.European framework for the digital. DigCompEdu. Joint Research Centre (JRC) Science for Policy report.

- RomeroM, GuàrdiaL, GuitertM, SangràA, . 2014.Teachers’ professional development through Learning Ecologies: What are the experts’ views. In: TeixeiraA., SzucsA. , eds. for research into open & digital learning: Doing things better-doing better things. EDEN 2014 Research Workshop Conference Proceedings&author=Teixeira&publication_year= Challenges for research into open & digital learning: Doing things better-doing better things. EDEN 2014 Research Workshop Conference Proceedings.Oxford: European Distance and E-learning Network. 27-36

- SangràA, RaffaghelliJ, GuitertM, . 2019.ecologies through a lens: Ontological, methodological and applicative issues. A systematic review of the literature&author=Sangrà&publication_year= Learning ecologies through a lens: Ontological, methodological and applicative issues. A systematic review of the literature.British Journal of Educational Technology 50(4):1619-1638

- SangràA, González-SanmamedM, GuitertM, . 2013.ecologies: Informal professional development opportunities for teachers&author=Sangrà&publication_year= Learning ecologies: Informal professional development opportunities for teachers. In: , ed. IEEE 63rd Annual Conference International Council for Education Media (ICEM)&author=&publication_year= 2013 IEEE 63rd Annual Conference International Council for Education Media (ICEM).1-2

- StrohmayerA, ComberR, BalaamM, . 2015.learning ecologies among people experiencing homelessness&author=Strohmayer&publication_year= Exploring learning ecologies among people experiencing homelessness. In: , ed. of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems&author=&publication_year= Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.2275-2284

- TondeurJ, Forkosh-BaruchA, PrestridgeS, AlbionP, EdirisingheS, . 2016.Responding to challenges in teacher professional development for ICT integration in education.Educational Technology and Society 19(3):110-120

- TwiningP, RaffaghelliJ, AlbionP, KnezekD, . 2013.education into the digital age: The contribution of teachers’ professional development&author=Twining&publication_year= Moving education into the digital age: The contribution of teachers’ professional development.Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 9(5):399-486

- UluyolC, SahinS, . 2016.school teachers’ ICT use in the classroom and their motivators for using ICT&author=Uluyol&publication_year= Elementary school teachers’ ICT use in the classroom and their motivators for using ICT.British Journal of Educational Technology 47(1):65-75

- UnalS, OzturkI H, . 2012.to ITC integration into teachers’ classroom practices: Lessons from a case study on social studies teachers in Turkey&author=Unal&publication_year= Barriers to ITC integration into teachers’ classroom practices: Lessons from a case study on social studies teachers in Turkey.World Applied Sciences Journal 18(7):939-944

- Van-Den-BeemtA, DiepstratenI, . 2016.perspectives on ICT: A learning ecology approach&author=Van-Den-Beemt&publication_year= Teacher perspectives on ICT: A learning ecology approach.Computers & Education 92-93:161-170

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Este artículo presenta un estudio exploratorio que examina prácticas de docentes referentes de Educación Primaria en su desarrollo profesional para la integración de las TIC en la docencia y el aprendizaje como medio de comprensión operacional de las ecologías de aprendizaje. Un docente referente en el contexto de este estudio es aquel que innova pedagógicamente y que influye en la comunidad, habiendo desarrollado con éxito su ecología de aprendizaje. Mediante un enfoque cualitativo, se explora el concepto de ecologías de aprendizaje como motor de la innovación en el desarrollo profesional de los docentes, utilizando una muestra cuidadosamente seleccionada de nueve profesores de Educación Primaria. A partir de entrevistas en profundidad, codificación específica y análisis con NVivo, los resultados muestran que estos docentes despliegan sistemas organizados de actividades, relaciones y recursos, que pueden ser caracterizados como componentes de sus ecologías de aprendizaje para mantenerse permanentemente actualizados. Se identifican algunas de las características y factores que potencialmente facilitan u obstaculizan el desarrollo de su ecología de aprendizaje. Futuras investigaciones en esta línea permitirán mejorar la comprensión de las ecologías de aprendizaje profesional de los docentes, apoyando nuevas intervenciones y recomendaciones para el desarrollo profesional.

ABSTRACT

This paper presents an exploratory study to examine the practices of outstanding primary school teachers in their professional development for ICT integration in teaching and learning, as a means of understanding how their learning ecologies develop and function. Outstanding teachers in the context of this study are teachers who innovate pedagogically and who are influential in the community, having successfully developed their learning ecology. Using a qualitative approach, we explore the concept of learning ecologies as a driver for innovation in the professional development of teachers, using a carefully selected sample of nine outstanding teachers. Drawing from in-depth interviews, specific coding and NVIVO analysis, our results show that these teachers develop organized systems for activities, relationships and resource usage and production, which can be characterized as the components of their professional learning ecology, to continuously keep up to date. We also identified some characteristics of teachers that perform outstandingly and factors that potentially facilitate or hinder their learning ecology development. Further research in the field will enable an improved understanding of the professional learning ecologies of school teachers and support future interventions and recommendations for professional development through the cultivation of emerging professional learning ecologies.

Palabras clave

Ecologías de aprendizaje, desarrollo profesional docente, educación primaria, docentes referentes, TIC, caso de estudio, factores influyentes, metodología cualitativa

Keywords

Learning ecologies, teachers’ professional development, primary school education, outstanding teachers, ICT, case studies, influencing factors, qualitative methodology

Introducción

Los docentes juegan un papel fundamental en la integración y uso efectivo de la tecnología en educación (Uluyol & Şahin, 2016). Mientras la mayoría de docentes de Educación Primaria reconoce el potencial de las TIC e Internet (Admiraal & al., 2017; Correa & Martínez, 2010; Potter & Rockinson-Szapkiw, 2012), su implementación continúa siendo limitada (Correa & Martínez, 2010; De-Jesús & Lebres, 2013) y en la escuela, infrautilizadas (Potter & Rockinson-Szapkiw, 2012).

Un cuestionario sobre competencias de adultos (OECD, 2016) revela que el 87% de docentes (Infantil, Primaria y Secundaria) consideran disponer de todas aquellas necesarias en su trabajo. La dificultad radica en la carencia de competencias para usar las TIC con finalidades educativas (De-Jesús & Lebres, 2013). La reconocida teoría del Conocimiento Técnico Pedagógico del Contenido (TPACK) surgió investigando sobre las dificultades que encontraban los docentes para aplicar la tecnología en la educación (Koehler & Mishra, 2009), y considera que el conocimiento pedagógico y disciplinario aplicado a la tecnología resulta fundamental, señalando distintas maneras en que este conocimiento puede desarrollarse. Esas dificultades llevaron al desarrollo del marco de la Competencia Digital Docente (DigCompEdu), que apoya la integración de la tecnología en las prácticas pedagógicas y desarrolla la competencia digital de los estudiantes (Redecker & Punie, 2017).

Los docentes se enfrentan a dificultades como la insuficiente formación, la falta de equipamiento adecuado o la falta de flexibilidad en el currículum (Nikolopoulou & Gialamas, 2015; Panagiotis & al., 2011; Unal & Ozturk, 2012). Sus actitudes hacia la tecnología están condicionadas por los recursos disponibles, el apoyo que reciben y la existencia de una cultura escolar motivadora (Agyei & Voogt, 2014; Uluyol & Şahin, 2016).

Un importante reto en su adopción tecno-pedagógica es promover estrategias efectivas de desarrollo profesional. La literatura sugiere que la mayoría del desarrollo profesional permanente se centra actualmente en aspectos administrativos e institucionales, provocando entre los docentes una sensación de impotencia respecto a su propio desarrollo (Jiménez, 2007). Como alternativa, se propone su empoderamiento mediante una definición más consensuada (Livingston & Robertson, 2010), la incorporación de prácticas colaborativas (Kennedy, 2011) y tutorías grupales (Geeraerts & al., 2015). Otra innovación de éxito son las transferencias de prácticas colegiales, consistentes en el acompañamiento de docentes inexpertos por parte de otros más experimentados (Lakkala & Ilomäki, 2015). La tutoría se identifica como un factor clave en el éxito de la formación docente en ejercicio (Dorner & Kárpáti, 2010), ya que los compañeros pueden proporcionar tanto apoyo práctico como emocional.

A pesar de sus avances, la formación profesional docente se basa esencialmente en enfoques innovadores que suelen mantenerse separados, centrándose en la perspectiva que el formador/asesor/coordinador tiene sobre los logros de aprendizaje a alcanzar (Bradshaw, Walsh, & Twining, 2011; Laurillard, 2014; Twining, Raffaghelli, Albion, & Knezek, 2013). Una perspectiva más integrada y centrada en quien aprende es crucial para fomentar su confianza en sus propias capacidades para integrar las innovaciones con TIC en su docencia (Tondeur, Forkosh-Baruch, Prestridge, Albion, & Edirisinghe, 2016). En epígrafes posteriores se describe el concepto de ecologías de aprendizaje (EA) como motor de innovación en el desarrollo profesional docente.

Desde los 90, los enfoques ecológicos para la educación en la era digital han dado paso a una gran variedad de términos y definiciones que se han utilizado ampliamente (Sangrà, Raffaghelli, & Guitert, 2019). El término EA se ha utilizado en muchos campos educativos como tecnologías y género (Barron, 2004), desarrollo de habilidades TIC (Barron, 2006), aprendizaje colaborativo (Hodgson & Spours, 2009), diseños de aprendizaje con tecnologías (Luckin, 2010), recursos de aprendizaje para personas sin hogar (Strohmayer, Comber, & Balaam, 2015), desarrollo profesional de docentes (Sangrà, González-Sanmamed, & Guitert, 2013), y aprendizaje personalizado a lo largo de la vida (Maina & García, 2016). Jackson (2011) ha explorado el constructo de EA, incorporando el concepto de aprendizaje a lo ancho de la vida, muy útil en tanto que las EA abarcan espacios y tipos de aprendizaje diferentes. El concepto de EA enfatiza una perspectiva centrada y auto-determinada en el aprendiz, lo cual es fundamentalmente importante para el desarrollo profesional en general, y para el docente en particular. Van-Den-Beemt y Diepstraten (2016) estudiaron las EA de docentes que empezaban a utilizar las TIC, en especial sus supuestos, expectativas, contextos y personas clave que alentaron su aprendizaje, concebido como un proceso horizontal entre una pluralidad de espacios (Akkerman & Van-Eijck, 2013).

La llegada de los entornos digitales ha generado otra dimensión de análisis para el concepto de EA: la selección y compromiso con contextos de aprendizaje digitales o analógicos/físicos. Si bien este aspecto ya se contempló en el trabajo seminal de Barron (2004), ha generado mediante estudios Delphi una nueva mirada para caracterizar las EA (González-Sanmamed, Muñoz-Carril, & Santos-Caamaño, 2019).

Estas consideraciones son relevantes para reconocer que, mientras muchos estudios sobre EA intentan analizar experiencias y prácticas en curso, pocos dan apoyo a estrategias para el desarrollo profesional (Sangrà, Raffaghelli, & Guitert, 2019). Considerando el actual debate sobre la necesidad de mejorar la efectividad del desarrollo profesional docente, parecía particularmente apropiado investigar las EA a lo largo de la vida en docentes de Primaria, en un esfuerzo por apoyar futuras investigaciones, estrategias, intervenciones y recomendaciones para el desarrollo profesional basado en el cultivo de EA.

Metodología

Los métodos cualitativos permiten la exploración profunda de discursos y prácticas emergentes. Intentan comprender la complejidad del conocimiento experimental, mientras evitan algunas limitaciones y síntesis que requieren los métodos cuantitativos. Aunque no permiten el estudio de la causalidad o la generalización de los resultados de la investigación, sí abarcan descripciones muy ricas en las que los nuevos patrones emergentes pueden respaldar una exploración adicional (Ingleby, 2012). Este estudio se planteó como objetivo explorar prácticas de referencia en el desarrollo profesional auto-dirigido para la integración de las TIC en la enseñanza, como medio para comprender cómo se desarrollan y funcionan las EA de éxito.

En este contexto, por docentes referentes nos referimos a aquellos que han sido pioneros en la creación y aplicación de innovaciones pedagógicas, organizando de manera efectiva su desarrollo profesional auto-dirigido, con el que habitualmente influyen a otros docentes. Analizamos en profundidad una muestra de docentes de Educación Primaria como seguimiento de una fase inicial de consulta de expertos (Romero, Guàrdia, Guitert, & Sangrà, 2014). Estas fueron las preguntas planteadas:

- P1. ¿Qué componentes conforman las EA profesionales de los docentes referentes de Educación Primaria?

- P2. ¿Qué otros factores influencian en el desarrollo y el mantenimiento de las EA de estos docentes?

Recogida de datos: selección de casos y estructura de la entrevista

Los referentes fueron docentes que han demostrado una apropiación continuada de la tecnología con respecto tanto a su docencia en clase como a su propio desarrollo profesional.

A partir de una muestra inicial de 24 candidatos, mediante un proceso de cinco fases (tal como se ilustra en la Figura 1), se seleccionaron nueve docentes.

|

|

La muestra fue extraída de entre los docentes de Educación Primaria en ejercicio en Cataluña (España). El criterio inicial para la inclusión fue disponer de experiencia profesional variada. Estos son los criterios de inclusión restantes:

1) Utilizan un conjunto de relaciones y recursos confiables que les permite actualizarse continuamente.

2) Utilizan las TIC para extender su propia EA para su desarrollo profesional.

3) Han desarrollado una EA que impacta positivamente en su práctica profesional.

Estos criterios generales se refinaron más para establecer unas características más específicas:

a) Son activos en las redes sociales: participan en dos o tres redes sociales; participan en listas de distribución; hacen un uso frecuente de ambas.

b) Están interesados en la innovación: son coautores de una publicación; han recibido un premio; han participado en un proyecto de innovación.

c) Usan las TIC en el aula: las usan como apoyo o como complemento; preparan materiales docentes o recursos usando (reusando) materiales que encuentran en Internet.

De los nueve docentes seleccionados, tres ejercen la docencia desde hace menos de 10 años, tres hace entre 10 y 20 años, y otros tres hace más de 20 años.

Se combinaron tres métodos de recogida de datos: entrevistas, materiales y otros productos de las actividades docentes. Nuestro enfoque para el análisis de los estudios de caso se basó en entrevistas en profundidad como instrumento de recogida de datos, una codificación específica y un análisis utilizando el software NVivo.

Codificación y análisis

Las observaciones sobre las prácticas en Internet y los medios sociales se triangularon con los datos recogidos en las entrevistas, constituyendo los datos textuales resultantes del corpus de análisis.

El análisis cualitativo se realizó mediante el uso de NVivo. Las entrevistas con los nueve docentes se codificaron a partir de un análisis temático con las categorías y códigos generados conceptualmente por el estudio Delphi (ver mapa conceptual en la Figura 2), realizado en la fase de investigación previa (Romero & al., 2014). El estudio actual profundiza en el mapa mediante la identificación de componentes específicos que motivan a los docentes a emprender actividades de fortalecimiento de ciertas interacciones, y a usar determinados recursos en sus contextos de aprendizaje personal y profesional.

|

|

Para obtener el libro final de códigos axiales y básicos de la investigación inductiva (Tabla 1 disponible en https://bit.ly/2kIjXjj), cuatro investigadores acordaron la estrategia de codificación y dos investigadores codificaron el corpus de datos. El porcentaje de acuerdo entre evaluadores fue del 99% para todos los códigos, con un coeficiente kappa de 0,68 (nivel aceptable de acuerdo). Durante el proceso de codificación, además de los tres componentes de la EA (actividades, interacciones y recursos), detectamos algunos factores emergentes relevantes relacionados con el impulso del crecimiento y mantenimiento de la EA, a los cuales denominamos posicionamiento personal y factores influyentes en el desarrollo de la EA.

Resultados y análisis

Describimos nuestros resultados considerando los tres principales componentes de las EA (actividades, interacciones y recursos) y los dos factores adicionales surgidos del proceso de codificación: posicionamiento personal y factores que influyen en el desarrollo de la EA.

Caracterizando las EA de los docentes referentes

En los nueve casos se encontraron una gran variedad de enfoques. Tal como se muestra en la Tabla 1, hubo una gran concentración de elementos específicos entre los docentes. Por ejemplo, mientras los nueve docentes participan en actividades formales, en línea y presenciales, solo seis participan en actividades auto-dirigidas, y únicamente cinco han seguido MOOCs. En general, siguiendo una pauta establecida, se observa más diversidad en las actividades auto-dirigidas que en las actividades dirigidas externamente propuestas en los niveles nacionales o institucionales.

Actividades

Respecto a las actividades, observamos una gran densidad discursiva en relación con la participación en cursos (106 de 302 referencias), que ofrecen la oportunidad de establecer redes profesionales. Las dinámicas usualmente coinciden: a partir de interacciones presenciales o en línea, los docentes devienen seguidores o amigos en redes sociales. Los cursos varían mucho: los que ofrece el centro, MOOCs, etc., aunque hay una mayor tendencia hacia los presenciales y externos.

Muchos docentes optan por la educación formal, presencial o en línea, mayoritariamente ofrecida por universidades: «he estado mirando los cursos de TDH. Nos los estábamos mirando el otro día y decíamos que deberíamos apuntarnos a alguno. Son cursos del propio centro… Nos estamos empezando a poner con ello, ya que tenemos que empezar a hacer cosas presenciales en este sentido» (C5, R1_1.2.1b). «Una de las razones de hacer el Máster de innovación educativa era ir por ahí, poder conocer y adentrarse en el mundo de la gente que se forme y cómo montar las formaciones» (C2, R2_1.2.1b).

Otros muestran preferencia por canales informales y más prácticos: «una de las cosas que también me gusta es poder acceder a personas que considero referentes fácilmente sin molestarles. Yo no he de ir a preguntarles nada. Ellos son tan amables que una vez por semana o mes explican sus opiniones, las cuales me gusta oír, sin tenerme que desplazar a lugares donde esta gente da charlas» (C1, R1-2_1.3.1a).

En relación a las actividades presenciales, es notable la asistencia a actos y conferencias de un solo día e interacciones informales con compañeros y estudiantes en prácticas en las escuelas, que representan un canal importante de actualización. Los docentes referentes tienden a preferir actividades presenciales en su centro, sean formales o informales: «el año pasado presentamos, junto con dos personas más, un proyecto de innovación que pretendía dar pistas de cómo podíamos introducir las tabletas en Infantil y entonces esto llevaba un año, con una dedicación muy pequeña de horas presupuestadas» (C2, R1-2_1.5.2).

Especial consideración merece la participación en actividades informales y auto-dirigidas. Como ya hemos mencionado, los docentes empiezan habitualmente con actividades formales, y continúan a lo largo de un recorrido informal que es gestionado por el propio docente en un proceso de cuestionamiento, demostración o intercambio de prácticas profesionales: «eso te da pie a poder ir a algunas conferencias o algunas charlas. Entonces, claro, conoces gente. J.A., por ejemplo, me hizo descubrir a A.R., y tuve la oportunidad de poder escucharle, este hombre es ‘chapeau’. A.R. nos vino a dar una charla en la escuela» (C3, R1_1.4.1a).

Interacciones

Sus interacciones en línea se centran en buscar información y comparar ideas y conocimiento, estableciendo así relaciones personales y profesionales. Su uso de redes sociales es notable, ya sea activa (participación) o pasivamente (consulta), igual que sus visitas a blogs de referencia: «yo no soy muy de redes sociales, o sea, no soy una persona muy activa dentro de las redes sociales, las utilizo por ejemplo para hacer preguntas, ¿de acuerdo? Esta vertiente yo no la he explotado mucho, he sido más un participante pasivo» (C1, R1_2.1.3).

Twitter es la red social más utilizada por varias razones: mantenerse al día con información de colegas y referentes; buscar información específica; consultar y obtener información diariamente; seguir a referentes y colegas del propio centro y de otros; compartir recursos, información y reflexiones personales; advertir sobre trabajos publicados; solicitar ayuda, información, etc.; y, en general, para actualizarse con cursos presenciales o en línea.

Aunque todos tienen cuenta en Twitter, tienden a ser usuarios moderados, ya que no publican o solo lo hacen esporádicamente. Su uso suele ser por conveniencia y no se consideran a sí mismos referentes: «Twitter parece que no, pero es una gran fuente. Si te haces fan de gente que es buena, es decir, por ejemplo, de la PPL, pues te llegan muchas alertas que probablemente no lo hubieras sabido nunca aquello. Entonces a través del Twitter me va genial porque echas un vistazo y de lo que dices, ‘ah, mira tal’, y entonces la búsqueda en profundidad» (C5, R3_2.1.3).

Facebook es bastante menos popular entre estos docentes. Empezaron a utilizarlo de forma más personal y, progresivamente, fueron compartiendo información o reflexiones con y de otros colegas: «lo que pasa es que el Facebook ha llegado un momento que lo uso como algo más personal y entonces el Twitter lo he utilizado más a nivel profesional. Hubo un momento en que era ‘profesional 100% del Facebook’. ¿Qué me pasa? Pues que, claro, aquí tengo compañeros y al final decían... paso de ti... cansas. También lo entiendo y también me he dado una pausa de decir ‘organizo mi vida social’» (C3, R2-3_2.1.3).

LinkedIn es otra red utilizada esporádicamente (C7, C3), con el propósito de publicar currículums en línea y establecer contactos profesionales. Menos frecuentemente, adoptan SlideShare, Keynote y Prezzi para acceder a presentaciones de referentes (C4, C9) o compartir presentaciones. Estas herramientas son de uso público, pero en algunos casos los docentes comparten presentaciones internamente con sus colegas (C9); por ejemplo: Ning para monitorear foros, Evernote para almacenar información para consulta y análisis ordenadamente, y Pinterest para gestionar proyectos y encontrar nuevas ideas.

En resumen, las interacciones se distribuyen homogéneamente entre presenciales y en línea (106 de 302 y 116 de 300 referencias, respectivamente). Utilizan las presenciales para el diálogo y la colaboración durante proyectos de intervención educativa o prácticas rutinarias, mientras que aquellas en línea tienen la ventaja de la sincronía/asincronía. Así, establecen formas de intercambio de conocimiento que permiten completar, integrar y construir su repertorio profesional de estrategias docentes. Los docentes, pues, son simultáneamente receptores y emisores, invirtiendo, en ambos casos, esfuerzos cognitivos para completar su conocimiento mediante aprendizaje vicario (lo que otros hacen) y práctica reflexiva (lo que hacen ellos mismos).

Recursos

Estos docentes se caracterizan por una intensa actividad en línea usando en pocas ocasiones medios físicos e impresos. Los blogs administrados por educadores influyentes y con fines de divulgación educativa son los recursos más frecuentemente consultados (42 de 82 referencias). Acceden a estos blogs mediante Twitter o subscripciones vía RSS, combinando así interacciones en redes sociales con acceso a recursos específicos: «la rutina habitual es el seguimiento de blogs y Twitter. De hecho, he de reconocer que no he entendido cómo funciona Twitter hasta hace un año. En cambio, yo soy muy de blog, mucho» (C1, R1_3.2.1).

No son solo receptores pasivos. Algunos son también blogueros, sea mediante blog personal, de grupo o de centro. Publican y comparten recursos que refuerzan específicamente aspectos de la práctica educativa. En estos casos, la frecuencia de publicación es normalmente semanal o quincenal. Existe gran variabilidad en el tipo de recursos usados, además de los blogs educativos, entre los que se incluyen sitios web institucionales (12 de 83 referencias), recursos educativos y datos abiertos (que suman 21 de 83 referencias).

Finalmente, en el desempeño de estas acciones, utilizan principalmente teléfonos inteligentes, tabletas y ordenadores. Los teléfonos inteligentes y las tabletas se utilizan generalmente cada día para consultas y para mantenerse actualizados, mientras que los ordenadores se reservan para tareas que requieren mayor interactividad, como, por ejemplo: leer, investigar, escribir, etc. La mayoría de estos docentes utilizan software comercial, aunque algunos utilizan software abierto tanto para la enseñanza como para su actualización profesional.

Factores que influyen en el desarrollo de las EA de los docentes referentes

Las entrevistas revelan varios factores que intervienen en cómo los docentes de Primaria configuran y actualizan sus EA profesionales en cuanto a recursos, actividades e interacciones. Respecto al estudio previo (Romero & al., 2014), se identificaron dos nuevos tipos de factores: los de posicionamiento personal y los que influyen en el desarrollo de la EA, reflejando el desarrollo histórico individual y el contexto institucional.

Factores de posicionamiento personal

El posicionamiento personal de los docentes referentes caracteriza su productividad y éxito en la aplicación de tecnologías en el aula, reflejando un aprendizaje profesional rápido y efectivo. La Tabla 2 reproduce algunos de los comentarios de los entrevistados.

|

|

Evidentemente, el posicionamiento personal refleja una fuerte motivación interna para buscar recursos y establecer relaciones que conduzcan a aprendizajes formales, no formales e informales. La densidad semántica en el discurso de los nueve docentes (34 de 102 referencias) revela su pasión y curiosidad, pero también su elevada motivación para encontrar en su centro micro-contextos que les permitan la configuración de experiencias innovadoras.

Factores que influencian el desarrollo de la EA

El centro educativo actúa como contexto en el que tanto los aspectos positivos y negativos, actuales o históricos, se convierten en facilitadores u obstaculizadores del desarrollo de la EA. Nuestro análisis revela la existencia de necesidades de formación que van más allá de la oferta institucional, lo que explica por qué los docentes referentes tienden a diversificar sus canales y actividades de formación.

La densidad semántica en relación a este tema sugiere que los docentes referentes tienen percepciones similares respecto a los facilitadores y los obstáculos (20 y 22 de 47 referencias, respectivamente). Los factores históricos son menos frecuentes que los contextuales. Los aspectos negativos generalmente se refieren más al contexto regulatorio nacional que a los centros en particular, mientras que, entre los positivos, vale la pena destacar las acciones concretas que los centros han impulsado para facilitar la autonomía de sus docentes referentes. La Tabla 3 reproduce algunos de los comentarios de los entrevistados.

|

|

A pesar de las fuertes limitaciones históricas y contextuales, estos docentes generalmente encuentran en sus centros apoyo a su autonomía con la activación de los cursos que solicitan, y en tiempo libre para su formación, reuniones regulares y proyectos con tecnología, con el establecimiento de bases mínimas para el uso de las TIC y la asignación de roles como expertos (trae tu propio dispositivo, robótica, habilidades de programación), etc.

En resumen, hay una sinergia continuada entre las características de estos docentes y sus contextos, que estimula, apoya y promueve sus actitudes positivas y proactivas a la transformación digital en el aula. La fertilización cruzada entre estos docentes y distintos tipos de proyectos (por ejemplo, enfoques interdisciplinares, actividades de empoderamiento científico y socio-cultural en la comunidad, etc.) genera ecosistemas ricos en los cuales la EA profesional encuentra un terreno abonado.

Discusión

Nuestros resultados dibujan una rica imagen de las EA potenciales de los docentes en el dominio específico de las TIC en las escuelas de Educación Primaria. Sin embargo, han emergido varios factores que apoyan el desarrollo y mantenimiento de EA, y que representan un paso más en la compresión del aprendizaje profesional.

Los conceptos anteriores de EA han enfatizado su estructura (actividades, interacciones y recursos). No obstante, a partir de nuestras entrevistas aparecieron dos tipos de factores sin los cuales las EA no se podrían sostener: los ligados al posicionamiento personal y los contextuales e históricos que influyen en el desarrollo de la EA.

En la primera parte del análisis, observamos que el aprendizaje profesional tiende a derivarse de las actividades formales y se basa principalmente en relaciones con los colegas en el propio centro y la participación en proyectos institucionales. Los factores externos, sin embargo, funcionan como indicadores motivacionales para que los docentes referentes los sigan como referencia en el desarrollo de sus competencias profesionales; como el compromiso con los recursos digitales y las comunicaciones informales en línea como medio para garantizar la continuidad de la relación en las redes sociales.

Existe una motivación interna en estos docentes que los lleva a conectar con el mundo exterior desde una imagen interna ideal de cómo debería desenvolverse su práctica profesional. Esta hipótesis se sostiene, además, por los factores de posicionamiento personal como soportes de la arquitectura de actividades, interacciones y recursos de la EA. Si esta motivación interna (que refleja la personalidad y las experiencias vividas por quien aprende) se pone en juego, entonces el docente construye su EA sobre un espíritu de curiosidad y pasión por la innovación, la búsqueda activa de conexiones y la práctica reflexiva. No solo consultan con otros el trabajo que hacen para modelar su propia práctica, sino que también disponen de una visión del desarrollo de su propio contexto, lo que implica asumir orientaciones y políticas nacionales e institucionales. El esquema de su EA se representa en la Figura 3, en la que el mapa conceptual inicial (Figura 2) se reorganizó y amplió a partir de la codificación del discurso de los nueve docentes.

|

|

Conclusiones

Nuestro estudio contribuye a la reconceptualización de los componentes que constituyen las EA. El enfoque cualitativo mediante entrevistas en profundidad ha supuesto un enriquecimiento de la imagen de las EA, expandiendo los nodos semánticos a partir del mapa conceptual inicial. Además, añade un debate que describe el perfil de los docentes referentes, y pone las bases para futuras investigaciones. Estos docentes son personas que:

- Buscan oportunidades de formación activamente siguiendo cursos más «tradicionales», como las actividades presenciales propuestas por la institución, pero también actividades informales en línea.

- Continúan expandiendo sus oportunidades de aprendizaje mediante interacciones informales en comunidades profesionales, donde juegan un papel crucial como creadores o seleccionadores de recursos.

- No resulta sorprendente que sean activos seguidores de blogs, siendo estos los principales recursos que seleccionan. Esto se alinea con la idea de buscar personas influyentes, cuyas ideas aporten nueva luz a la práctica diaria.

- Destaca la importancia de su posicionamiento personal frente al contexto, sintiéndose activamente comprometidos en innovaciones, impulsados por una gran curiosidad. Comprenden cuáles son los factores facilitadores en sus contextos profesionales y los utilizan como medios para su práctica con una profunda comprensión de las fuerzas reactivas en su campo de práctica profesional.

- Futuras investigaciones sobre los perfiles de estos referentes pueden aportar información sobre micro-factores en los contextos de aprendizaje profesional (externo) o sobre las características personales en las que otros pueden inspirarse cuando intenten una apropiación tecnología positiva en sus prácticas pedagógicas.

Nuestros resultados tienen implicaciones tanto para la innovación en el desarrollo profesional como para la investigación aplicada. Sugieren la necesidad de identificar otros docentes referentes potenciales para explorar su creatividad como expresión de su posicionamiento personal hacia el desarrollo institucional. El proceso de descubrimiento y apoyo puede exigir mucha dedicación, pero, al final, la identificación de estos docentes podría llevar a un efecto dominó creativo en el que otros docentes menos efectivos en generar innovación la construyesen a partir de las buenas prácticas de sus referentes. La investigación aplicada en estrategias de gestión escolar permitiría la exploración de este enfoque, de modo que la imagen común de la estructura de las EA podría generarse a través de reuniones participativas para crear conciencia de los principales componentes de un modelo de EA.

El posicionamiento personal y sus factores relacionados podrían, asimismo, explorarse como ya se ha enfatizado en la literatura sobre aprendizaje profesional auto-regulado (Littlejohn, Milligan, & Margaryan, 2012). Este tipo de auto-conciencia podría ser el desencadenante para un desarrollo continuado de los enfoques de aprendizaje profesional individual con cada uno de los docentes motivado por cultivar y enriquecer su propia EA profesional.

En el campo de la investigación, los análisis de las EA podrían avanzar hacia estudios sistemáticos confirmatorios utilizando muestras representativas. Estudios posteriores podrían perfeccionar el modelo y obtener algunos indicadores de carácter predictivo respecto a los factores que influencian el desarrollo y la configuración de las EA. Además, la metodología de investigación basada en el diseño podría permitir el desarrollo de herramientas de auto-diagnóstico que incrementasen la conciencia de quien aprende sobre cómo configurar su propia EA.

Nuestro estudio tiene varias limitaciones. La más importante es que, a pesar del riguroso proceso de selección tipo «bola de nieve», nueve docentes representan un universo de práctica reducido. No obstante, los hallazgos respecto a nuestros docentes referentes pueden ayudar a impulsar cambios en su desarrollo profesional. Podemos considerar nuestra investigación enfocada a mejorar las estrategias de aprendizaje profesional de docentes de Educación Primaria, exploratoria y contribuyente a una mayor comprensión de las EA a lo largo de la vida.

References

- AdmiraalW, LouwsM, LockhorstD, PaasT, …kesterL, . 2017.in school-based technology innovations: A typology of their beliefs on teaching and technology&author=Admiraal&publication_year= Teachers in school-based technology innovations: A typology of their beliefs on teaching and technology.Computers & Education 114:57-68

- AgyeiD D, VoogtJ, . 2014.factors affecting beginning teachers’ transfer of learning of ICT-enhanced learning activities in their teaching practice&author=Agyei&publication_year= Examining factors affecting beginning teachers’ transfer of learning of ICT-enhanced learning activities in their teaching practice.Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 30(1):92-105

- AkkermanS F, Van-EijckM, . 2013.the student dialogically across and between boundaries of multiple communities&author=Akkerman&publication_year= Re-theorising the student dialogically across and between boundaries of multiple communities.British Educational Research Journal 39(1):60-72

- AttardM, ShanksR, . 2017.importance of environment for teacher professional learning in Malta and Scotland&author=Attard&publication_year= The importance of environment for teacher professional learning in Malta and Scotland.European Journal of Teacher Education 40(1):91-109

- BarronB, . 2004.ecologies for technological fluency: Gender and experience differences&author=Barron&publication_year= Learning ecologies for technological fluency: Gender and experience differences.Journal of Educational Computing Research 31(1):1-36

- BarronB, . 2006.and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: A learning ecology perspective&author=Barron&publication_year= Interest and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: A learning ecology perspective.Human Development 49(4):193-224

- BradshawP, WalshC, TwiningP, . 2011.Vital Programme: Transforming ICT professional development&author=Bradshaw&publication_year= The Vital Programme: Transforming ICT professional development.American Journal of Distance Education 26(2):74-85