Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Elucidating personal factors that may protect against the adverse psychological outcomes of cyberbullying victimisation might help guide more effective screening and school intervention. No studies have yet examined the role of emotional intelligence (EI) and gender in adolescent victims of cyberbullying and how these dimensions might interact in explaining cybervictimisation experiences. The main aim of this study was to examine the relationship between EI and cybervictimisation, and the interactive link involving EI skills and gender as predictors of cyberbullying victimisation in a sample of 1,645 Spanish adolescents (50.6% female), aged between 12 and 18 years. Regarding the prevalence of cybervictimisation, our results indicated that over 83.95% of the sample were considered non-cyber victims, while 16.05% experienced occasional or severe cyber victimisation. Additionally, findings indicated that deficits in EI and its dimensions were positively associated with cyber victimisation in both genders, but were stronger in females. Besides, a significant emotion regulation x gender association was found in explaining cyber victimisation experiences. While no interaction was found for males, for females the deficits of emotion regulation were significantly associated with greater victimisation. Our findings provide empirical support for theoretical work connecting EI skills, gender and cyber victimisation, suggesting emotion regulation skills might be considered as valuable resources, as well as the inclusion in new gender-tailored cyberation victimisation prevention programmes.

1. Introduction

School bullying is recognised as a serious psychosocial problem commonly seen during adolescence in school settings worldwide (Book, Volk, & Hosker, 2012; Casas, Del Rey, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2013). Resulting from the growing use of new technologies and social media, cyberbullying has emerged as a new kind of abuse in cyberspace, which is related to school bullying (Kowalski, Giumetti, Schroeder, & Lattanner, 2014). Cyberbullying, also known as digital bullying, is defined as repeated aggressive and hostile messages sent through the use of electronic media against a victim who cannot easily defend him- or herself (Hinduja & Patchin, 2009). According to a recent meta-analysis, prevalence rates of cyberbullying and victimisation vary depending on the definitions of the phenomenon. In general, most of the studies that have addressed cyberbullying show prevalence rates of between 10 and 40% of adolescents involved, finding incidences of 15% for adolescent cybervictimisation (Zych, Ortega-Ruiz, & Del Rey, 2015). In contrast to traditional bullying, the use of electronic devices provides new challenges for intervention due to unique features such as anonymity, rapid social dissemination and increased access to the victims (Alvarez-Garcia, Nuñez, Dobarro, & Rodriguez, 2015; Tokunaga, 2010). Thus, cyberbullying experiences are consistently associated with a wide range of negative outcomes. For instance, youths who encounter cyberbullying report significantly higher levels of psychosomatic problems than non-involved youths (Beckman, Hagquist, & Hellström, 2012), higher levels of depressive symptoms (Nixon, 2014), greater levels of anxiety symptoms (Sontag, Clemans, Graber, & Lyndon, 2011), lower self- esteem (O’Brien & Moules, 2013) and even higher rates of suicide ideation and attempts (Gini & Espelage, 2014). Furthermore, being the victim of cyberbullying negatively affects the victims’ emotional and social adjustment (Elipe, Mora-Merchan, Ortega-Ruiz, & Casas, 2015). In particular, cybervictimisation has been linked with negative feelings such as anger, upset, sadness, helplessness, fear, shame, guilt or loneliness (Elipe & al., 2015; Ortega & al., 2012).

When peer victimisation is not handled appropriately, it can have a huge influence on the development of internal and external problems that lead to reduced levels of well-being (Zych & al., 2015). However, all cybervictims do not develop the same negative outcomes or to the same grade of intensity (Dredge, Gleeson, & Garcia, 2014; Elipe & al., 2015). Certain risk and protective factors are considered contributors to important aspects of cognitive and emotional adjustment (Gini, Pozzoli, & Hymel, 2014; Kowalski & al., 2014). Research suggests that certain cognitive and socio-emotional variables might determine the impact of cybervictimisation on mental health such as social abilities, empathy or personality traits, among others (Perren & al., 2012; Ttofi, Farrington, & Lösel, 2014). Over the last two decades, one variable that has shown growing evidence regarding its potential role as a buffer against negative effects of cyberbullying is emotional intelligence (EI) (Baroncelli & Ciucci, 2014; Elipe & al., 2015; Extremera, Quintana-Orts, Mérida-López, & Rey, 2018).

The literature has shown that the way in which people process the emotionally relevant information during stressful events is relevant for healthy functioning and positive relationships (Rey & Extremera, 2014). From an ability model, EI is conceptualised as a group of abilities to perceive emotions, to access emotions, to enhance thoughts, to understand emotions and emotional knowledge, and to regulate emotions to promote emotional and intellectual growth (Mayer & Salovey, 1997). Several studies have revealed that adolescents with EI are able to use and regulate their emotions and others’ negative emotions for improving happiness and psychological well-being, and preventing psychological maladjustment (Fernandez-Berrocal & Extremera, 2016; Hill, Heffernan, & Allemand, 2015; Tucker, Bitman, Wade, & Cornish, 2015).

Previous research, in both traditional bullying and cybervictimisation, has pointed out that students with higher levels of EI are less peer victimised and even experience more positive social behaviors (Elipe & al. 2015; Garaigordobil & Oñederra, 2010; Lomas, Stough, Hansen, & Downey, 2012). Recently, Elipe and al. (2015) found that high levels of emotional clarity but low levels of emotional repair in cybervictims contribute to manifestations of negative emotional impact, while high levels of attention together with high repair ability tend to reduce anger and depression among undergraduate students. These results suggest the crucial role of the EI variable in cyberbullying, specifically in the emotion regulation dimension.

Gender differences are key variables related to cyberbullying and EI, which have demonstrated a relevant impact on health outcomes and social adaptation. Despite the mixed nature of the results of studies on the prevalence of cybervictimisation (Del Rey, Elipe, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2012), most have found that females are more victimised than males (Kowalski & al., 2014; Li, 2006; Palermiti, Servidio, Bartolo, & Costabile, 2017). Besides, focusing on emotions, cybervictims have a higher ability to attend emotions and a lower ability to understand and regulate emotions (Elipe & al., 2015; Ortega & al., 2012).

However, few studies have paid attention to examining the gender differences in EI skills in the context of cyberbullying in a Spanish high school sample. The aim of this study is to make progress in this direction, specifically, by examining the interplay between EI and cybervictimisation experiences and the potential role of gender in moderating this relationship in a large sample of Spanish adolescents.

Taking into account the above considerations, the objective of this study was threefold: on the one hand, to analyse the role of EI related to the gender differences of the victims of cyberbullying among Spanish adolescents. Thus, we examine the predictive validity of EI dimensions in relation to cybervictimisation. Finally, we sought to examine whether there was a significant interactive model involving EI and gender as concurrent predictors of cybervictimisation beyond what is accounted for by direct effects of socio-demographic variables and EI. Consistent with the literature, we hypothesise differences between males and females and we expected to find evidence for an EI x gender interaction for explaining cybervictimisation.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

The sample comprises a total of 1 645 adolescents (50.6% female), aged between 12 and 18 years (M=14.08; SD=1.53) from six public schools in Málaga province (Spain). The sample of schools was selected according to their availability for participating in the study, and there was a similar percentage of adolescents from the different educational centers. Regarding the level taught, 29.1% attended classes of the first course of compulsory secondary education; 27.7% attended second course; 21.8% third course and 12.6% the final course of compulsory secondary education. The remainder of the sample attended classes at A level (8.8%).

2.2. Measures

Cybervictimisation. Cybervictimisation was measured with the cybervictimisation dimension of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire (ECIPQ) (Brighi, Guarini, Melotti, Galli, & Genta, 2012; Del Rey & al., 2015). It consists of 11 Likert type items (i.e., Someone posted embarrassing videos or pictures of me online) with five response options for frequency of behaviors towards them during the last two months, (from 0=None to 4=More than once a week). This subscale has shown good psychometric properties (Casas & al., 2013; Ortega-Ruiz, Del Rey, & Casas, 2012). In the present sample, the Cronbach’s Alpha was adequate (a=0.86). Following the criteria used by Elipe, De-la-Oliva and Del Rey (2017), we considered ‘non-cybervictims’ as those adolescents who marked option ‘none’ or the‘once or twice’ option in all items; ‘occasional cybervictims’ as those students who indicated that at least one of the behaviours had happened to them with a frequency of ‘once or twice a month’; and ‘severe cybervictims’ as those who indicated that at least one of the behaviours had happened ‘about once a week or more’.

Emotional intelligence. EI was evaluated using the ‘Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale’ (WLEIS) (Law, Wong, & Song, 2004), a questionnaire composed of four dimensions: self-emotion appraisal (SEA), other-emotion appraisal (OEA), use of emotion (UOE) and regulation of emotion (ROE). The scale comprises a total of 16 Likert type items with seven options ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). This scale has shown satisfactory reliability in Spanish samples (Rey, Extremera, & Pena, 2016). In this study, Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.88 for the overall scale, 0.75 for SEA, 0.72 for OEA, 0.77 for UOE and 0.80 for ROE.

2.3. Procedure

This study was part of a larger project that examined the relationship between strengths and health correlates of adolescents. Prior to data collection, head teachers and principals of the different schools selected randomly received an explanation about the research and a request for their collaboration accompanied by consent letters. The study respected the ethical values required in research with human beings having been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Málaga, Spain (62-2016-H). The questionnaires were completed by adolescents during the second trimester of the 2016/2017 academic year during a tutorial lesson. A teacher from the school with a research assistant was presented in class to assist with any questions. The adolescents were also informed of the study’s objectives and its voluntary and confidential nature. They had one hour to answer all questionnaires.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive analyses

Descriptive statistics (Table 1) and prevalence analyses were conducted to examine all variables included in the study and the percentage of cybervictimisation presented in our sample. Regarding the prevalence of cybervictimisation, 16.05% of participants reported that at least one of the behaviors in the survey had happened to them ‘once or twice a month’ or ‘once or twice a week or more frequently’ (7.78% occasional and 8.27% severe, respectively).

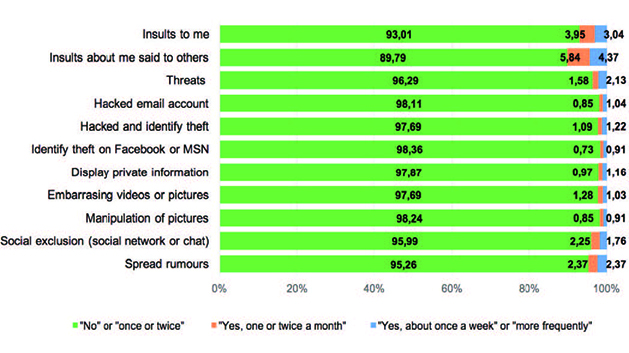

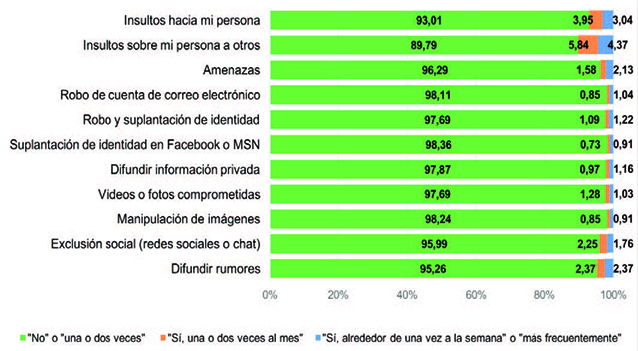

As it can be seen in Figure 1, the most frequently experienced types of cybervictimisation were ‘insults about me said to others via the Internet or SMS messages’ (10.21%), followed by ‘direct personal insults via email or SMS messages’ (6.99%). On the contrary, only 1.64% said that ‘somebody had created a fake account to pretend to steal their identity.’ Finally, in the cases of ‘receiving threats through texts or online messages,’ this happened about once a week or more frequently (2.13%).

3.2. Gender differences in relation to EI and cybervictimisation

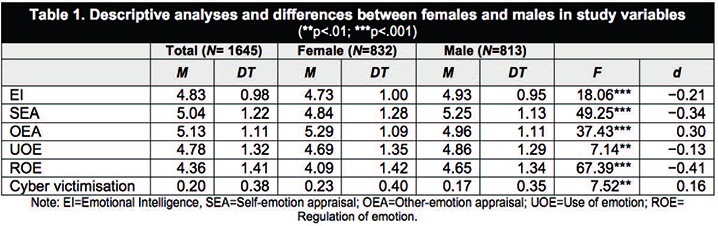

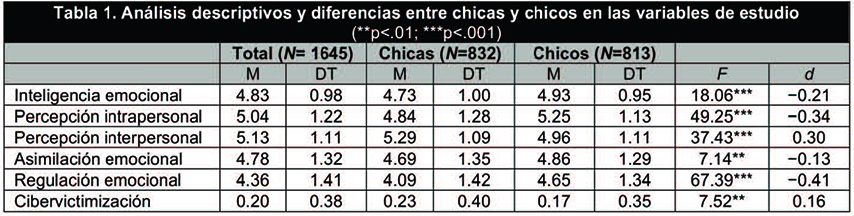

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine gender differences. We followed Cohen’s convention (1988) to estimate the effect size of differences by gender. The results are shown in Table 1. We found that males scored higher in self-emotion appraisal, use of emotion, regulation of emotion and total EI, whereas females reported higher scores in other-emotion appraisal and cybervictimisation.

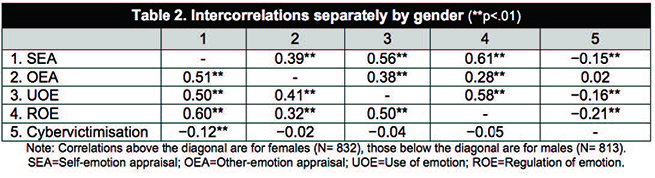

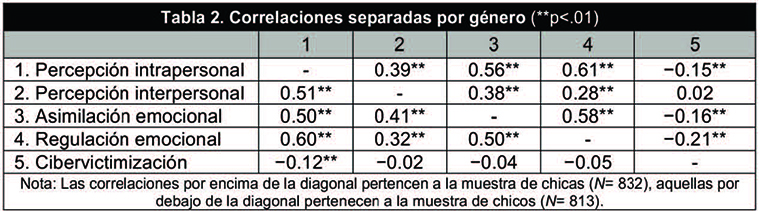

Pearson correlations were conducted to examine the associations between EI dimensions and cybervictimisation separately for females and males. As seen in Table 2, self-emotion appraisal was negatively related to cybervictimisation for both females and males. More interestingly, the use of emotion and regulation of emotion were negatively related to cybervictimisation only for females. According to Cohen’s convention (1988), the effect sizes of the correlations were small.

3.3. Predictive value of EI dimensions in cybervictimisation

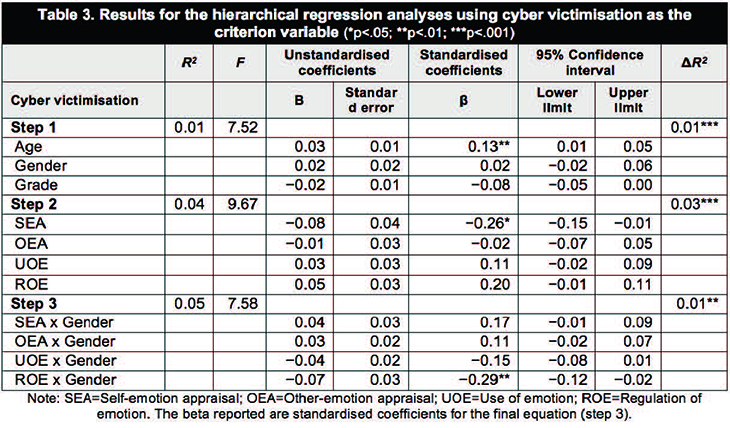

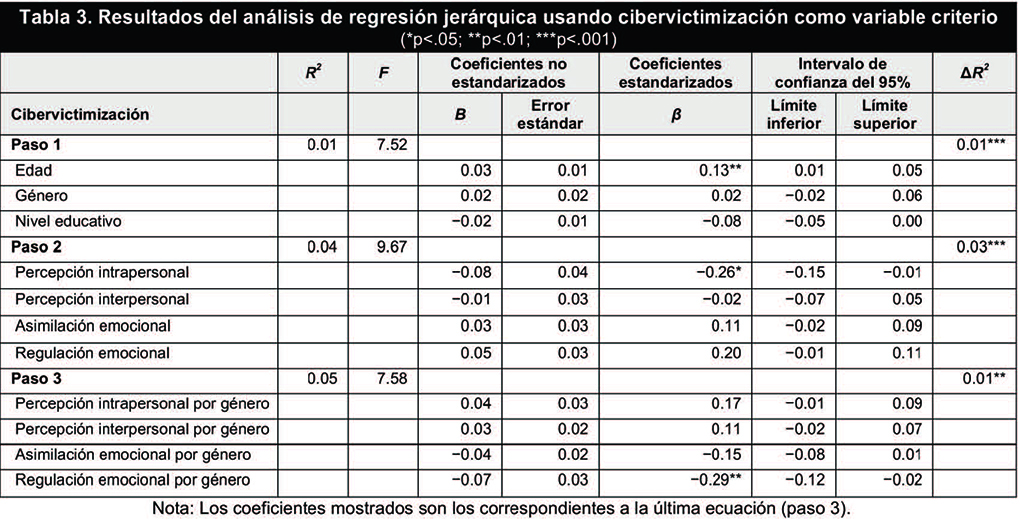

We tested the predictive validity of EI dimensions in predicting cybervictimisation scores along with the potential moderating role of gender in these relationships. We conducted hierarchical regression analyses in which we took cybervictimisation as the dependent variable. In the first step, age, gender, and grade were entered as covariates. EI dimension scores were entered in the second step. The EI dimensions x gender interactions were included in the third step. All continuous predictors were centered in order to reduce potential problems of multicollinearity (Aiken & West, 1991). The main results of these analyses are displayed in Table 3.

For predicting cybervictimisation, a total of 5% of the variance was explained by the final model. First, we found that age was positively related to cybervictimisation scores and significantly contributed to the prediction of this variable. Second, we found that self-emotion appraisal was the only dimension that accounted for a significant amount of the variance in cybervictimisation, even after controlling the variance attributable to our covariates. Finally, we found that the regulation of the emotion x gender interaction was significant in the prediction of cybervictimisation scores beyond the main effects of the covariates and EI dimensions.

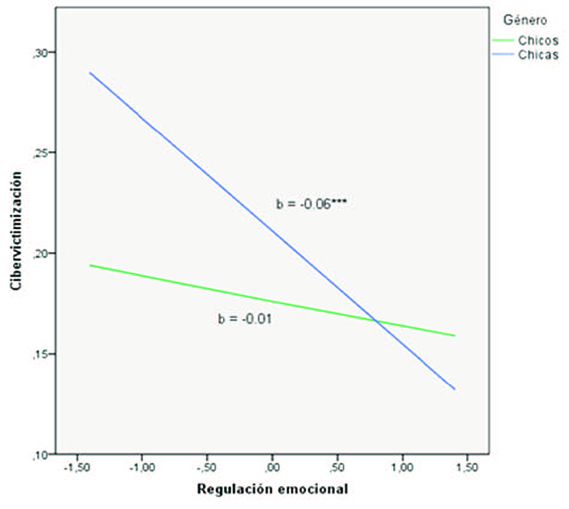

As a final point, we used Process to graphically represent the moderating effects. Following standard procedures, we used a bootstrapping procedure based on 5,000 bootstrapped resamples and a 95% confidence interval. Figure 2 shows the relationship between regulation of emotion and cybervictimisation scores by gender. We found a negative association between regulation of emotion and cybervictimisation for females (b=–0.06, t(832)=–6.11, p<0.001). In particular, it was at the low emotion regulation level where female adolescents showed higher cybervictimisation. On the contrary, we did not find interaction effects between regulation of emotion and cybervictimisation in males (b=–0.012, t(813)=–1.27).

4. Discussion and conclusion

The current study was designed to examine how EI dimensions and cybervictimisation are related in high school students and to analyse the moderating role of gender in this association. Our study replicated previous EI findings (Elipe & al., 2015), confirming the positive role of these emotional skills on the levels of cybervictimisation in a large sample of Spanish adolescents. Besides, our findings extend those of earlier studies by finding evidence that gender might be an underlying mechanism that could moderate the relationship between certain EI dimensions and cybervictimisation experiences.

Regarding the prevalence of cybervictimisation, our results show similar percentages to those reported by a recent systematic review (Zych & al., 2015). Following the criteria used by Elipe and al. (2017), over 83.95% of the sample was considered as non-cybervictims. Inversely, 16.05% were considered occasional or severe cybervictims. The most frequent forms of cyberbullying in this study were ‘insults about me said to others via the Internet or SMS messages,’ similar to results of previous studies carried out with adolescents (Katzer, Fetchenhauer, & Belschack, 2009).

Consistent with previous research regarding both traditional victimisation and cybervictimisation (Elipe & al., 2015; Lomas & al., 2012), our study found that higher levels of total EI were significantly and negatively associated with lower scores in cybervictimisation both in males and females. Our findings are in line with the approach suggesting that the propensity of being cybervictimised by peers is, to some extent, related to the victim´s emotional abilities. Interestingly, compared to male victims, the relationship between total and specific emotional abilities and cybervictimisation experiences of female victims was stronger. In short, all subscales except one (interpersonal perception) showed small but still negative and significant associations with cybervictimisation for females. On the contrary, only global EI and intrapersonal perception showed a significant and negative association with cybervictimisation for males.

With respect to examining the gender differences in EI skills and cybervictimisation experiences, gender analyses showed that males reported higher self-reported global EI along with higher intrapersonal perception, assimilation and emotional regulation than females. Some authors have found that males tend to report higher ability to regulate own emotions compared with female adolescents (Extremera, Duran, & Rey, 2007). Since the male gender role is to be more agentic and active, it is possible that male adolescents might use more frequent problem-solving strategies and positive reappraisal in attempts to change the negative daily experiences that hey believe are driving their mood states (Tamres, Janicki, & Helgeson, 2002). These are in line with literature findings that male adolescents typically reported less psychological symptoms than female ones (Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2009). On the other hand, another potential reason is that male adolescents typically tend to overestimate their emotional skills compared to females when using self-report measures (Brackett, Rivers, Shiffman, Lerner, & Salovey, 2006), therefore, depending on the EI measures used, gender difference results might be different. Further research should examine this issue carefully, using EI ability measures to generalise our findings. Regarding female adolescents, some researchers have shown that women typically report a greater tendency to be attentive to moods and regulate emotions compared with men, both in adult and adolescent populations (Fernandez-Berrocal & Extremera, 2008; Salguero, Fernandez-Berrocal, Balluerka, & Aritzeta, 2010; Thayer, Rossy, Ruiz-Padial, & Johnsen, 2003). Furthermore, women tend to be more vulnerable to the impact of stressful life events (Kessler & McLeod, 1984). It may be that differences in the emotional regulation process between men and women might form the basis of the higher prevalence rate in women of emotional maladjustment and the use of maladaptive coping strategies (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003; Thayer et al., 2003). Finally, the analysis indicated that, compared to male adolescents, female students were more likely to be victims of cyberbullying (Kowalski & al., 2014). While this gender difference in cybervictimisation demands further research, one plausible explanation is that female adolescents tend to be more likely to experience indirect forms of bullying than their male counterparts, and the negative impact of these experiences is stronger in females (Carbone-Lopez, Esbensen, & Brick, 2010).

Moreover, we found that emotion regulation interacted differently as a function of gender, extending previous literature regarding gender differences on the influence of EI in other areas of psychology such as interpersonal relationships (Brackett & al., 2006) or psychological adjustment (Merida-Lopez, Extremera, & Rey, 2017). Expanding on previous research, our study revealed an interesting finding substantiating evidence for the moderating effect of gender with deficits in emotion regulation as a risk factor for cybervictimisation experiences. In this research, mood regulation was the only EI ability which interacted significantly with gender in predicting cybervictimisation experiences in line with similar studies (Lomas & al., 2012; Schokman & al., 2014). In short, we found significant differences in the associations between emotion regulation and cybervictimisation for females, but not for males. While no interaction effect was found for males between mood regulation and cybervictimisation, in female adolescents the relationship with cybervictimisation was more negative at higher levels of emotion regulation. In line with our correlational findings, it is tentative to assume that emotion regulation skills may be more associated with cybervictimisation for female adolescents. By contrast, it might be that, for males, these regulation abilities may not be so important or may imply different socio-educational or psychological factors associated with men other than emotion regulation to explain cybervictimisation. Further research should examine this issue.

Therefore, the future implementation of anti-bullying programmes aimed at reducing cybervictimisation might take into account these gender differences in mood regulation to develop more effective training by specifically focusing on the emotional deficits/strengths characteristically present in females and males. Several authors have underlined that specific prevention and intervention strategies need to be developed tailored to the special needs of each gender (Kowalski & al., 2014). In addition, our findings raise questions about the role of gender in strategies used in cybervictimisation experiences and asks for further exploration to examine the specific mechanisms that link differences in EI and cybervictimisation between males and females.

Even though the present study makes a novel contribution to the existing literature, there are several limitations that should be addressed by further research. First, although our data provide preliminary evidence for a moderating role of gender in predicting cybervictimisation experiences, the cross-sectional nature of our design makes it impossible to determine the directionality of any causal relationships. Further prospective follow-up studies or a longitudinal design would help to untangle the causal direction. In addition, it is important to underline that the adolescent sample is based on a convenience sample, so the results of this study cannot be generalised. Future work should apply a random design or use adolescent samples with clinically diagnosed psychiatric problems associated with cybervictimisation experiences, which would increase the degree of generalisation of the findings. Another potential limitation was the use of self-report measures which might be subject to social desirability. Future studies should replicate our findings using a wider array of assessment approaches with multiple sources (i.e., parents, school practitioners, peers), as well as other measures of cybervictimisation (e.g., the Cybervictimization questionnaire (CBV) by Alvarez, Dobarro, & Nuñez, 2015). Besides, we used an EI self-report measure. Although tools of this type are widely used in the scientific literature, their combined use with newer ability-based measures based on performance criteria would increase our knowledge beyond what the WLEIS data allows, not only about the independent and interactive effect of perceived and actual EI but also about insights into the design of professionally guided interventions focusing on emotional knowledge, emotional self-efficacy, and EI abilities aimed at reducing the negative consequences of cybervictimisation. Finally, the inclusion of measures of personality (i.e., big five) and social abilities would provide a comprehensive perspective and would generate some new insights into the interactive role that EI, personality traits, and social skills play in reducing the negative symptoms associated to cybervictimisation.

Despite these limitations, our study has provided some empirical evidence that EI is associated with cybervictimisation experiences in life. As practical implications, given that extensive evidence has shown that the emotional skills grouped into the EI construct can be learned and are susceptible to being developed through school programmes in children and adolescents (Ruiz-Aranda, & al., 2013), the present findings might serve as a good starting point for inclusion of training in EI skills as an additional intervention strategy to complement current anti-bullying approaches to reduce cybervictimisation experiences in adolescents at risk. If these findings can be replicated, psychological service providers should include EI abilities while working with adolescent females to prevent cyberbullying since our findings suggest that a deficiency in mood regulation in female adolescents has a combined effect in increasing cybervictimisation experiences. Additionally, other implications for school officials and counselors are that evaluating the interactive association between EI and gender in explaining cybervictimisation might be fundamental as these variables may potentially be used as a screening assessment to identify potential high school students who might be at risk of cybervictimisation after experiencing cyberbullying behaviors. Also, as Lomas and al. (2012) have argued, detection and identification of risk factors related to victims of cyberbullying would help to change the role of school practitioners, moving from a ‘policing’ role to inhibit disruptive behaviours and securely engage cyber behaviours of bullies, to a more active role in developing emotional skills and mood regulation strategies of cyberbullies and their victims. Nevertheless, since prevention and intervention programmes aimed at increasing EI skills have only been implemented in a normal sample of high school students, further research should specifically examine the efficacy of these EI prevention programmes for adolescents at risk of peer cybervictimisation. Some preliminary work has shown the effectiveness of EI interventions in Spanish high school settings to reduce physical/verbal aggression and hostility and increase empathy and mental health (Castillo, Salguero, Fernandez-Berrocal, & Balluerka, 2013). It is tentative to assume that similar intervention programmes might be used to reduce psychological distress and negative symptoms in those adolescents who are at a greater risk of being subjected to peer cybervictimisation.

In conclusion, our findings shed some light on the importance of considering EI skills for the preventative design of anti-bullying programmes and provide preliminary evidence for using a gender-tailored cybervictimisation approach as a potentially efficient way of coping with the associated distress caused by cyberbullying experiences.

Funding Agency

This research has been carried out within the framework of the Research Project «Forgiveness as a protective factor against suicide and psychological maladjustment among bullied adolescents» (PPIT.UMA.B1.2017/23) supported by the University of Málaga.

References

Aiken, L.S., & West, S.G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Alvarez-Garcia, D., Dobarro, A., & Nuñez, J.C. (2015). Validez y fiabilidad del cuestionario de cibervictimización en estudiantes de Secundaria. Aula Abierta, 43(1), 32-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aula.2014.11.001

Alvarez-Garcia, D., Nuñez, J.C., Dobarro, A., & Rodriguez, C. (2015). Risk factors associated with cybervictimization in adolescence. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 15(3), 226-235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2015.03.002

Baroncelli, A., & Ciucci, E. (2014). Unique effects of different components of trait emotional intelligence in traditional bullying and cyberbullying. Journal of Adolescence, 37(6), 807- 815. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.05.009

Beckman, L., Hagquist, C., & Hellström, L. (2012). Does the association with psychosomatic health problems differ between cyberbullying and traditional bullying? Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 17, 421-434. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2012.704228

Book, A.S., Volk, A.A., & Hosker, A. (2012). Adolescent bullying and personality: An adaptive approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 218-223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.028

Brackett, M.A., Rivers, S.E., Shiffman, S., Lerner, N., & Salovey, P. (2006). Relating emotional abilities to social functioning: A comparison of self-report and performance measures of Emotional Intelligence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(4), 780-795. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.780

Brighi, A., Guarini, A., Melotti, G., Galli, S., & Genta, M.L. (2012). Predictors of victimisation across direct bullying, indirect bullying and cyberbullying. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 17(3-4), 375-388.

Carbone-Lopez, K., Esbensen, F., & Brick, B.T. (2010). Correlates and consequences of peer victimization: Gender differences in direct and indirect forms of bullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 8, 332-350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204010362954

Casas, J.A., Del Rey, R., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2013). Bullying and cyberbullying: Convergent and divergent predictor variables. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 580-587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.015

Castillo, R., Salguero, J.M., Fernandez-Berrocal, P., & Balluerka, N. (2013). Effects of an emotional intelligence intervention on aggression and empathy among adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 883-892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.07.001

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd Ed.). Hilldsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Del Rey, R., Casas, J.A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Smith, P., … Plichta, P. (2015). Structural validation and cross-cultural robustness of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 141-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.065

Del Rey, R., Elipe, P., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2012). Bullying and cyberbullying: Overlapping and predictive value of the co-occurrence. Psicothema, 24, 608-613.

Dredge, R., Gleeson, J., & Garcia, X.P. (2014). Cyberbullying in social networking sites: an adolescent victim’s perspective. Computer and Human Behaviour, 36, 13-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.026

Elipe, P., De-la-Oliva, M., & Del Rey, R. (2017). Homophobicbullying and cyberbullying: Study of a silenced problem. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(5), 672-686. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2017.1333809

Elipe, P., Mora-Merchan, J.A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Casas, J.A. (2015). Perceived emotional intelligence as a moderator variable between cybervictimization and its emotional impact. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 486. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00486

Extremera, N., Duran, A., & Rey, L. (2007). Perceived emotional intelligence and dispositional optimism-pessimism: Analyzing their role in predicting psychological adjustment among adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 1069-1079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.014

Extremera, N., Quintana-Orts, C., Mérida-López, S., & Rey, L. (2018). Cyberbullying victimization, self-esteem and suicidal ideation in adolescence: Does emotional intelligence play a buffering role? Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 367. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00367

Fernandez-Berrocal, P., & Extremera, N. (2008). A review of trait meta-mood research. In M.A. Columbus (Ed.), Advances in Psychology Research (pp.17-45). San Francisco: Nova Science.

Fernandez-Berrocal, P., & Extremera, N. (2016). Ability Emotional Intelligence, Depression, and Well-Being. Emotion Review, 8(4), 311-315. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073916650494

Garaibordobil, M., & Oñederra, J.A. (2010). Inteligencia emocional en las víctimas de acoso escolar y en los agresores [Emotional intelligence in victims of school bullying and in aggressors]. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 3(2), 243-256.

Gini, G., & Espelage, D.L. (2014). Peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide risk in children and adolescents. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 312, 545-546. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.3212

Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Hymel, S. (2014). Moral disengagement among children and youth: A meta-analytic review of links to aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 40, 56-68. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21502

Hill, P.L., Heffernan, M.E., & Allemand, M. (2015). Forgiveness and Subjective Well-Being: Discussing Mechanisms, Contexts, and Rationales. In L.L. Toussaint (Ed.). Forgiveness and Health (pp. 155-169). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9993-5_11

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J.W. (2009). Bullying beyond the schoolyard: Preventing and responding to cyberbullying. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Katzer, C., Fetchenhauer, D., & Belschack, F. (2009). Cyberbullying: who are the victims? A comparison of victimization in Internet chatrooms and victimization in school. Journal of Media Psychology, 21(1), 25-36. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105.21.1.25

Kessler R.C., & McLeod J.D. (1984). Sex differences in vulnerability to undesirable life events. American Sociological Review, 49, 620-631. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095420

Kowalski, R.M., Giumetti, G.W., Schroeder, A.N., & Lattanner, M.R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1073-1137. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035618

Law, K.S., Wong, C.S., & Song, L.J. (2004). The construct and criterion validity of emotional intelligence and its potential utility for management studies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 483-496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.483

Li, Q. (2006). Cyberbullying in schools: A research on gender differences. School Psychology International, 27, 157-170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034306064547

Lomas, J., Stough, C., Hansen, K., & Downey, L.A. (2012). Brief report: Emotional intelligence, victimization and bullying in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 207-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.03.002

Mayer, J.D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey, & D. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implication (pp. 3-31). New York: Basic Books.

Merida-Lopez, S., Extremera, N., & Rey, L. (2017). En busca del ajuste psicológico a traves de la inteligencia emocional ¿es relevante el género de los docentes? Behavioral Psychology/Psicología Conductual, 25, 581-597.

Nixon, C.L. (2014). Current perspectives: The impact of cyberbullying on adolescent health. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 5, 143-158. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S36456

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2003). The response styles theory. In C. Papageorgiou & A. Wells (Eds.), Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment of negative thinking in depression (pp. 107- 123). New York: Wiley.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Hilt, L.M. (2009). Gender differences in depression. In I.H. Gotlib & C.L. Hammen (Eds.), Handbook of Depression (pp. 386-404). New York: Guilford.

Ortega, R., Elipe, P., Mora-Merchan, J.A., Genta, M.L., Brighi, A., Guarini, A., … Tippett, N. (2012). The emotional impact of bullying and cyberbullying on victims: a European cross-national study. Aggressive Behavior, 38, 342-356. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21440

Ortega-Ruiz, R., Del Rey, R., & Casas, J.A. (2012). Knowing, building and living together on internet and social networks: The ConRed cyberbullying prevention program. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 6(2), 302-312. https://doi.org/10.4119/UNIBI/ijcv.250

O’Brien, N., & Moules, T. (2013). Not sticks and stones but tweets and texts: Findings from a national cyberbullying project. Pastoral Care in Education: International Journal of Psychology in Education, 31, 53-65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2012.747553

Palermiti, A.L., Servidio, R., Bartolo, M.G., & Costabile, A. (2017). Cyberbullying and self-esteem: An Italian study. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 136-141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.026

Perren, S., Corcoran, L., Cowie, H., Dehue, F., Garcia, D.J., McGuckin, C., … Völlink, T. (2012). Tackling cyberbullying: Review of empirical evidence regarding successful responses by students, parents, and schools. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 6, 283-292.

Rey, L., & Extremera, N. (2014). Positive psychological characteristics and interpersonal forgiveness: Identifying the unique contribution of emotional intelligence abilities, Big Five traits, gratitude and optimism. Personality and Individual Differences, 68, 199-204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.04.030

Rey, L., Extremera, N., & Pena, M. (2016). Emotional competence relating to perceived stress and burnout in Spanish teachers: a mediator model. PeerJ, 4:e2087. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2087

Ruiz-Aranda, D., Cabello, R., Salguero, J.M., Palomera, R., Extremera, N., & Fernandez-Berrocal, P. (2013). Guía para mejorar la inteligencia emocional de los adolescentes. Programa INTEMO. Madrid: Piramide.

Salguero, J.M., Fernandez-Berrocal, P., Balluerka, N., & Aritzeta, A. (2010). Measuring perceived emotional intelligence in the adolescent population: psychometric properties of the Trait Meta-Mood scale. Social Behavior and Personality, 38(9), 1197-1210. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2010.38.9.1197

Schokman, C., Downey, L.A., Lomas, J., Wellham, D., Wheaton, A., Simmons, N., & Stough, C. (2014). Emotional intelligence, victimisation, bullying behaviours and attitudes. Learning and Individual Differences, 36, 194-200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.10.013

Sontag, L.M., Clemans, K.H., Graber, J.A., & Lyndon, S.T. (2011). Traditional and cyber aggressors and victims: a comparison of psychosocial characteristics. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 392-404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9575-9

Tamres, L.K., Janicki, D., & Helgeson, V.S. (2002). Sex differences in coping behavior: a meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6, 2-30. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0601_1

Thayer, J.F., Rossy, L. A., Ruiz-Padial, E., & Johnsen, B.H. (2003). Gender differences in the relationship between emotional regulation and depressive symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 349-364. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023922618287

Tokunaga, R.S. (2010). Following you home from school: A critical reviewand synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 277-287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.014

Ttofi, M.M., Farrington, D.P., & Lösel, F. (2014). Interrupting the continuity from school bullying to later internalizing and externalizing problems: findings from cross-national comparative studies. Journal of School Violence, 13, 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2013.857346

Tucker, J.R., Bitman, R.L., Wade, N.G., & Cornish, M.A. (2015). Defining forgiveness: Historical roots, contemporary research, and key considerations for health outcomes. In L. Toussaint, E. Worthington, & D. Williams (Eds.), Forgiveness and HealthScientific Evidence and Theories Relating Forgiveness to Better Health (pp. 13-28). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9993-5_2

Zych, I., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Del Rey, R. (2015). Systematic review of theoretical studies on bullying and cyberbullying: Facts, knowledge, prevention, and intervention. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23, 121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.10.001

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Dilucidar los factores personales que protegen contra las consecuencias psicológicas de la cibervictimización podría ayudar a una detección e intervención escolar más eficaz. Ningún estudio ha examinado el papel de la inteligencia emocional (IE) y el género en adolescentes víctimas de ciberacoso y cómo estas dimensiones interactuan para explicar la cibervictimización. El objetivo de este estudio fue examinar la relación entre IE y cibervictimización, y el papel moderador de las habilidades de IE y el género como predictores de la cibervictimización en una muestra de 1.645 adolescentes españoles (50,6% mujeres) de edades entre 12 y 18 años. Con respecto a la prevalencia, nuestros resultados indicaron que el 83,95% de la muestra no eran cibervíctimas mientras un 16,05% eran cibervíctimas ocasionales o severas. Los resultados mostraron que los déficits en IE y sus dimensiones se asociaron positivamente con la cibervictimización en ambos géneros, pero más en mujeres. Además, se encontró una interacción significativa entre regulación emocional y género explicando las experiencias de cibervictimización. Aunque no hubo interacción para los hombres, para las mujeres el déficit en regulación emocional se asoció significativamente a mayor cibervictimización. Nuestros hallazgos proporcionan apoyo empírico para el corpus teórico que conecta las habilidades de IE, el género y la cibervictimización, sugiriendo que la regulación emocional puede ser considerada un recurso valioso, así como de inclusión en futuros programas de prevención de cibervictimización ajustados por géneros.

1. Introducción

El acoso escolar es considerado un problema psicosocial grave que tiene lugar durante la adolescencia en centros escolares de todo el mundo (Book, Volk, & Hosker, 2012; Casas, Del Rey, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2013). Como resultado del creciente uso de las redes sociales y las nuevas tecnologías, el ciberacoso ha surgido como un tipo de abuso en el ciberespacio que está relacionado con el acoso escolar (Kowalski, Giumetti, Schroeder, & Lattanner, 2014). El ciberacoso, también conocido como acoso digital, es definido como el conjunto de mensajes hostiles y agresivos repetitivos que son enviados a través de medios electrónicos contra una víctima que no puede defenderse fácilmente (Hinduja & Patchin, 2009). De acuerdo a un reciente metaanálisis, los índices de prevalencia del ciberacoso y la victimización varían de acuerdo a las definiciones del fenómeno. En general, la mayoría de los estudios sobre ciberacoso muestran unos índices de prevalencias de entre un 10 y un 40% de adolescentes implicados, encontrando un 15% de incidencia para la cibervictimización (Zych, Ortega-Ruiz, & Del Rey, 2015). En comparación con el acoso escolar tradicional, el uso de medios electrónicos proporciona nuevos retos a la intervención debido a características como el anonimato, la rápida diseminación social y el fácil acceso a las víctimas (Alvarez-Garcia, Nuñez, Dobarro, & Rodriguez, 2015; Tokunaga, 2010). Así, las experiencias de ciberacoso están consistentemente asociadas con un amplio rango de consecuencias. Por ejemplo, los jóvenes que se enfrentan al ciberacoso informan de mayores niveles de problemas psicosomáticos que aquellos no implicados en estas situaciones (Beckman, Hagquist, & Hellström, 2012), así como de mayores niveles de síntomas depresivos (Nixon, 2014), mayores niveles de síntomas de ansiedad (Sontag, Clemans, Graber, & Lyndon, 2011), menor autoestima (O’Brien & Moules, 2013) e incluso mayores niveles de intentos e ideaciones suicidas (Gini & Espelage, 2014). Además, ser víctima de ciberacoso afecta negativamente al ajuste social y emocional de las víctimas (Elipe, Mora-Merchan, Ortega-Ruiz, & Casas, 2015). Concretamente, la cibervictimización se ha asociado con sentimientos negativos como la ira, el enfado, la tristeza, la desesperanza, el miedo, la vergüenza, la culpa o la soledad (Elipe & al., 2015; Ortega, Del Rey, & Casas, 2012).

Cuando la victimización entre iguales no se maneja apropiadamente puede tener una gran influencia en el desarrollo de problemas internalizados y externalizados que implican un deterioro del bienestar (Zych & al., 2015). Sin embargo, todas las cibervíctimas no desarrollan las mismas consecuencias negativas o con el mismo grado de intensidad (Dredge, Gleeson, & Garcia, 2014; Elipe & al., 2015). Se considera que determinados factores de riesgo y de protección contribuyen a importantes aspectos del ajuste cognitivo y socio-emocional (Gini, Pozzoli, & Hymel, 2014; Kowalski & al., 2014). La investigación sugiere que ciertas variables cognitivas y sociales pueden determinar el impacto que la cibervictimización tiene sobre la salud mental, tales como las habilidades sociales, la empatía o los rasgos de personalidad, entre otros (Perren & al., 2012; Ttofi, Farrington, & Lösel, 2014). Durante las dos últimas décadas, una variable que ha mostrado evidencias de su potencial papel como amortiguador ante los efectos negativos del ciberacoso es la inteligencia emocional (IE) (Baroncelli & Ciucci, 2014; Elipe & al., 2015; Extremera, Quintana-Orts, Mérida-López, & Rey, 2018).

La literatura sobre IE ha mostrado que el modo en que las personas procesan la información emocional durante los eventos estresantes es relevante para un funcionamiento saludable y unas relaciones positivas (Rey & Extremera, 2014). Desde el denominado modelo de habilidad, la IE es conceptualizada como un conjunto de habilidades para percibir, acceder, comprender y regular las emociones para promover el crecimiento emocional e intelectual (Mayer & Salovey, 1997). Diferentes estudios han revelado que los adolescentes con IE son capaces de usar y regular sus emociones y las de los demás para mejorar su felicidad y su bienestar y prevenir el desajuste psicológico (Fernandez-Berrocal & Extremera, 2016; Hill, Heffernan, & Allemand, 2015; Tucker, Bitman, Wade, & Cornish, 2015). Investigaciones previas en relación al acoso escolar tradicional y la cibervictimización han señalado que los estudiantes con mayores niveles de IE son menos victimizados por sus iguales e incluso experimentan más comportamientos sociales positivos (Elipe & al. 2015; Garaigordobil & Oñederra, 2010; Lomas, Stough, Hansen, & Downey, 2012). Recientemente, Elipe y otros (2015) encontraron que altos niveles de claridad emocional pero bajos niveles de reparación en las cibervíctimas contribuye a un impacto emocional negativo, mientras que altos niveles de atención junto con altos niveles de reparación tienden a reducir la ira y la depresión entre estudiantes universitarios. Estos resultados sugieren el papel crucial de la IE en el ciberacoso, especialmente de la dimensión de regulación emocional.

Las diferencias de género son un factor clave en relación con el ciberacoso y la IE, al demostrar un impacto relevante sobre la salud y la adaptación social. A pesar de los resultados contradictorios de los estudios sobre la prevalencia de la cibervictimización (Del Rey, Elipe, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2012), la mayoría de ellos han encontrado que las mujeres son más victimizadas que los hombres (Kowalski & al., 2014; Li, 2006; Palermiti, Servidio, Bartolo, & Costabile, 2017). Además, centrándonos en las emociones, las cibervíctimas tienen una mayor habilidad para atender a sus emociones y una menor habilidad para comprenderlas y regularlas (Elipe & al., 2015; Ortega & al., 2012). Sin embargo, pocos estudios se han centrado en examinar las diferencias de género en las habilidades de IE en el contexto del ciberacoso en una muestra española de estudiantes de educación secundaria. El objetivo de este estudio es aportar evidencias en esta dirección, concretamente, examinar la interacción entre la IE y las experiencias de cibervictimización y el papel potencial del género para moderar esta relación en una amplia muestra de adolescentes españoles.

Teniendo en cuenta estas consideraciones, los objetivos de este estudio fueron tres: por un lado, analizar el papel de la IE en relación a las diferencias de género de las víctimas de ciberacoso entre adolescentes españoles. Por otro, examinar la validez predictiva de las dimensiones de IE en relación a la cibervictimización. Finalmente, examinar si existe una interacción significativa entre IE y género como predictores concurrentes de la cibervictimización más allá de los efectos directos de las variables socio-demográficas y la IE. De acuerdo con la literatura, se hipotetizan diferencias entre hombres y mujeres y se esperan encontrar evidencias de una interacción significativa entre IE y género para explicar la cibervictimización.

2. Materiales y metodología

2.1. Participantes

La muestra estaba formada por 1.645 adolescentes (50,6% chicas), con edades comprendidas entre los 12 y 18 años (M=14,08; DT=1,53) procedentes de seis centros públicos de la provincia de Málaga (España). La selección de centros se realizó de acuerdo a su disponibilidad para participar en el estudio, con un porcentaje similar de adolescentes perteneciente a los diferentes centros educativos. En relación al nivel educativo, el 29,1% asistía a clases del primer curso de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria; el 27,7% estaba en segundo curso; el 21,8% era de tercer curso y el 12,6% era de último curso de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. El resto de los participantes asistían a Bachillerato y Formación Profesional (8,8%).

2.2. Medidas

• Cibervictimización. Esta variable se midió con la dimensión de cibervictimización del Cuestionario del Proyecto Europeo de Intervención de Ciberbullying (ECIPQ; Brighi, Guarini, Melotti, Galli, & Genta, 2012; Del Rey & al., 2015). Se compone de 11 ítems evaluados a través de una escala tipo Likert (ejemplo: alguien ha colgado vídeos o fotos mías comprometidas en Internet) con cinco opciones de respuesta, que evalúa la frecuencia de comportamientos experimentados durante los últimos dos meses, (desde 0=No hasta 4=Más de una vez a la semana). Esta subescala ha mostrado adecuadas propiedades psicométricas (Casas & al., 2013; Ortega-Ruiz & al., 2012). En la presente muestra, el coeficiente alpha de Cronbach fue adecuado (0,86). Siguiendo los criterios utilizados por Elipe, De-la-Oliva y Del Rey (2017), consideramos «no-cibervíctimas» a los estudiantes que marcaron la opción de «no» o la opción de «una o dos veces» en todos los ítems; «cibervíctimas ocasionales» a los estudiantes que indicaron que al menos uno de los comportamientos les había ocurrido con una frecuencia de «una o dos veces al mes»; y «cibervíctimas severas» a los estudiantes que indicaron que al menos uno de los comportamientos les había ocurrido «más de una vez a la semana o más».

• Inteligencia emocional. Se evaluó usando la escala de IE de Wong y Law (WLEIS; Law, Wong, & Song, 2004), un cuestionario compuesto por cuatro dimensiones: evaluación de las propias emociones o percepción intrapersonal, evaluación de las emociones de los demás o percepción interpersonal, uso de las emociones o asimilación emocional y regulación de las emociones o regulación emocional. La escala consta de un total de 16 ítems con una escala tipo Likert con siete opciones de respuesta desde 1 (totalmente en desacuerdo) hasta 7 (totalmente de acuerdo). Esta escala ha mostrado buenos índices de fiabilidad en muestras españolas (Rey, Extremera, & Pena, 2016). En este estudio, el coeficiente alpha de Cronbach fue 0,88 para la puntuación total, 0,75 para percepción intrapersonal, 0,72 para percepción interpersonal, 0,77 para asimilación emocional y 0,80 para regulación emocional.

2.3. Procedimiento

Este estudio fue parte de un Proyecto más amplio que examinó la relación entre fortalezas e indicadores de salud en adolescentes. Previo a la recogida de datos, los miembros del equipo directivo de los diferentes centros seleccionados aleatoriamente recibieron una breve explicación sobre la investigación y una petición para su colaboración acompañada de documentos de consentimiento informado. El estudio sigue los valores éticos requeridos en investigación con personas y ha sido aprobado por el Comité Ético de la Universidad de Málaga, España (62-2016-H). Los cuestionarios se completaron durante el segundo trimestre del curso académico 2016/2017 durante clases de tutoría. Un profesor del centro y un investigador asistente estuvieron presentes en clase para prestar ayuda con cualquier pregunta. A los adolescentes se les informó de los objetivos del estudio y su naturaleza voluntaria y confidencial. Los participantes tuvieron una hora para responder a la batería de preguntas.

3. Resultados

3.1. Análisis descriptivos

Los estadísticos descriptivos (Tabla 1) y los análisis de prevalencia se realizaron con intención de examinar todas las variables incluidas y el porcentaje de cibervictimización informado por la muestra. En relación a la prevalencia de cibervictimización, el 16,05% de los participantes informaron que al menos uno de los comportamientos de la escala les había ocurrido «una o dos veces al mes» o «una o dos veces a la semana o más frecuentemente» (7,78% víctimas ocasionales y 8,27% severas, respecti-vamente). Como se muestra en la Figura 1, los tipos de cibervictimización experimentados más frecuentemente fueron «insultos sobre mi persona a otros a través de Internet o mensajes SMS» (10,21%), seguidos por «insultos directos a través de correo electrónico o mensajes SMS» (6,99%). Por el contrario, solo un 1,64% informó que «alguien había creado una cuenta falsa para intentar suplantar su identidad». Finalmente, un 2,13% recibió «amenazas a través de mensajes de texto u online» con una frecuencia de una vez a la semana o más.

3.2. Diferencias de género en relación a IE y cibervictimización

Se realizó un análisis de la varianza ANOVA de un factor para examinar las diferencias de género. Se siguieron los criterios de Cohen (1988) para estimar el tamaño del efecto de las diferencias por género. Los resultados se muestran en la Tabla 1. Encontramos que los chicos puntuaron más alto en percepción intrapersonal, asimilación emocional, regulación emocional e IE total, mientras que las chicas informaron de mayores puntuaciones en percepción interpersonal y cibervictimización. Se realizó un análisis de correlación de Pearson para examinar las asociaciones entre las dimensiones de IE y cibervictimización de manera diferencial para chicas y chicos. Como se muestra en la Tabla 2, la dimensión de percepción intrapersonal se relacionó negativamente con los niveles de cibervictimización para chicas y para chicos. De manera destacada, asimilación emocional y regulación emocional se relacionaron negativamente con cibervictimización solo para las chicas. De acuerdo a los criterios de Cohen (1988), los tamaños del efecto de las correlaciones fueron generalmente pequeños.

3.3. Valor predictivo de las dimensiones de IE sobre cibervictimización

Se examinó la validez predictiva de las dimensiones de IE para explicar las puntuaciones de cibervictimización junto con el potencial rol moderador del género en estas relaciones. Se realizaron análisis de regresión jerárquica en los cuales se incluyó la cibervictimización como variable dependiente. En el primer paso, edad, género y nivel educativo fueron introducidos como covariables. Las puntuaciones en las dimensiones de IE fueron introducidas en el segundo paso. Las interacciones de las dimensiones de IE por género fueron incluidas en el tercer paso. Todas las variables predictoras continuas fueron centradas para reducir posibles problemas de multicolinealidad (Aiken & West, 1991). Los principales resultados de estos análisis se muestran en la Tabla 3.

En cuanto a la cibervictimización, un 5% de la varianza fue explicada por el modelo final. En primer lugar, encontramos que la edad se relacionó positivamente con las puntuaciones en cibervictimización y contribuyó significativamente a la predicción de esta variable. En segundo lugar, encontramos que la percepción intrapersonal fue la única dimensión que explicó un porcentaje significativo de varianza de las puntuaciones de cibervictimización, incluso después de controlar la varianza atribuible a las covariables. Finalmente, encontramos que la interacción de regulación emocional por género fue significativa para predecir las puntuaciones de cibervictimización más allá de los efectos principales de las covariables y las dimensiones de IE. Además, se utilizó Process para representar gráficamente los efectos de moderación. Siguiendo los procedimientos habituales, se establecieron 5.000 remuestreos y un intervalo de confianza del 95%. La Figura 2 muestra la relación entre regulación emocional y las puntuaciones en cibervictimización por género. Encontramos una asociación negativa entre la regulación emocional y la cibervictimización para las chicas (b=–0.06, t(832)=–6.11, p<0.001). En particular, en el caso de niveles bajos de regulación emocional las chicas informaron de mayor cibervictimización. Por el contrario, no encontramos efectos de interacción entre la regulación emocional y la cibervictimización para los chicos (b=–0.012, t(813)=–1.27).

4. Discusión y conclusión

El presente estudio se diseñó para examinar cómo se relacionaban las dimensiones de IE y cibervictimización en estudiantes de secundaria y para analizar el papel moderador del género en esta asociación. Nuestro estudio coincide con hallazgos previos en IE (Elipe & al., 2015), confirmando la influencia positiva de las habilidades emocionales en los niveles de cibervictimización en una muestra amplia de adolescentes españoles. Además, nuestros datos extienden resultados de estudios anteriores presentando evidencias de que el género podría ser un mecanismo subyacente que modera la relación entre ciertas dimensiones de IE y experiencias de cibervictimización.

Respecto a la prevalencia de cibervictimización, nuestros resultados muestran porcentajes similares a los obtenidos en una reciente revisión sistemática (Zych & al., 2015). De acuerdo a los criterios utilizados por Elipe y otros (2017), un 83,95% de la muestra se identificó como no cibervíctima. Por el contrario, un 16,05% se consideró cibervíctima ocasional o severa. Las formas más frecuentes de ciberacoso en este estudio fueron «insultos sobre mi persona a otros a través de Internet o mensajes SMS», coincidiendo con estudios previos realizados con muestras adolescentes (Katzer, Fetchenhauer, & Belschack, 2009).

En línea con investigaciones previas sobre victimización tradicional y cibervictimización (Elipe & al., 2015; Lomas & al., 2012), nuestro estudio reveló que altos niveles en IE total estaban relacionados de manera negativa y significativa con menores puntuaciones en cibervictimización tanto en chicos como en chicas. Nuestros resultados avalan la perspectiva que sugiere que la tendencia a ser cibervictimizado por compañeros está, hasta cierto punto, relacionado con las habilidades emocionales de las víctimas. De manera destacada, comparado con los chicos, en las chicas la relación entre las puntuaciones totales y específicas de habilidades emocionales y las experiencias de cibervictimización fue más intensa. En resumen, todas las subescalas excepto una (percepción interpersonal) mostraron relaciones pequeñas pero, a su vez, negativas y significativas con cibervictimización para las chicas. Por el contrario, solo las puntuaciones en IE total y en percepción intrapersonal mostraron asociaciones significativas y negativas con cibervictimización para los chicos.

Con respecto a las diferencias de género en las habilidades de IE y las experiencias de cibervictimización, los análisis mostraron que los chicos informaban de mayores puntuaciones totales auto-informadas en IE, así como mayores puntuaciones en percepción intrapersonal, asimilación y regulación emocional que las chicas. Algunos autores han encontrado que los chicos tienden a informar de mayores habilidades de regulación emocional comparados con las chicas adolescentes (Extremera, Duran, & Rey, 2007). Dado que el rol de género masculino se caracteriza por atributos más activos y resolutivos, es posible que los chicos adolescentes puedan utilizar con mayor frecuencia estrategias centradas en el problema y reevaluaciones positivas para tratar de cambiar las experiencias negativas diarias que ellos creen que les provocan ciertos estados emocionales (Tamres, Janicki, & Helgeson, 2002), lo que estaría en línea con la literatura existente de que los chicos informan normalmente de menores síntomas psicológicos que las chicas (Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2009). Por otro lado, otra posible explicación es la tendencia que presentan normalmente los chicos a sobreestimar sus habilidades emocionales comparados con las chicas cuando se utilizan medidas auto-informadas (Brackett, Rivers, Shiffman, Lerner, & Salovey, 2006), por lo que, dependiendo de la medida de IE utilizada, los resultados de diferencias de género podrían ser distintos. Futuros estudios deberán examinar detenidamente este fenómeno utilizando medidas de habilidad de IE para la generalización de nuestros resultados. Con respecto a las chicas, algunos autores han mostrado que las mujeres informan normalmente de una mayor tendencia a la atención y la regulación emocional en comparación con los hombres, tanto en poblaciones adultas como adolescentes (Fernandez-Berrocal & Extremera, 2008; Salguero, Fernandez-Berrocal, Balluerka & Aritzeta, 2010; Thayer, Rossy, Ruiz-Padial, & Johnsen, 2003). Además, las mujeres tienden a ser más vulnerables al impacto de los eventos vitales estresantes (Kessler & McLeod, 1984). Parece que estas diferencias en los procesos de regulación emocional entre hombres y mujeres podrían constituir la base de mayores índices de prevalencia en el desajuste psicológico de las mujeres y en el uso de estrategias de afrontamiento desadaptativas (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003; Thayer & al., 2003). Finalmente, los análisis indicaron que, en comparación con los chicos adolescentes, las chicas presentaban más probabilidades de ser víctimas de ciberacoso (Kowalski & al., 2014). Pese a que son necesarios más estudios sobre estas diferencias de género en cibervictimización, una posible explicación es que las chicas adolescentes tienden a experimentar con mayor probabilidad formas indirectas de acoso en comparación con sus iguales del sexo masculino, siendo el impacto negativo de estas experiencias más fuerte en las chicas (Carbone-Lopez, Esbensen, & Brick, 2010).

Además, encontramos que la regulación emocional interactuaba de forma diferencial en función del género, ampliando la literatura existente con respecto a las diferencias de género en la influencia de la IE en otras áreas de la psicología como las relaciones interpersonales (Brackett & al., 2006) o el ajuste psicológico (Merida-Lopez, Extremera, & Rey, 2017). Extendiendo investigaciones previas, nuestro estudio revela un interesante hallazgo aportando evidencias del efecto moderador del género junto con déficits en regulación emocional como factores de riesgo para las experiencias de cibervictimización. En esta investigación, la regulación emocional fue la única habilidad de IE que interactuaba significativamente con el género para predecir las experiencias de cibervictimización, en línea con estudios similares (Lomas & al., 2012; Schokman & al., 2014). En resumen, encontramos diferencias significativas en las asociaciones entre regulación emocional y cibervictimización en chicas, pero no en chicos. Así, mientras que no se encontraron efectos de interacción entre regulación emocional y cibervictimización en los chicos, en las chicas adolescentes esta relación con cibervictimización fue más negativa a medida que se mostraban mayores niveles de regulación emocional. En línea con nuestros resultados correlacionales, se podría asumir que las habilidades de regulación emocional podrían estar más asociadas con la cibervictimización en chicas adolescentes. Por el contrario, para los chicos, estas habilidades de regulación podrían no ser tan importantes o en la explicación de la cibervictimización podrían estar implicados diferentes factores socio-educativos o psicológicos. Futuras investigaciones deberán examinar este fenómeno.

Por tanto, los programas anti-acoso escolar futuros con intención de reducir la cibervictimización deberían tener en cuenta estas diferencias en regulación emocional, con objeto de desarrollar entrenamientos más efectivos y específicamente centrados en los déficits y fortalezas característicos de chicos y chicas. Varios autores han subrayado que las estrategias preventivas y de intervención en este ámbito necesitan desarrollarse con un ajuste especial a las necesidades de cada género (Kowalski & al., 2014). Además, nuestros hallazgos plantean cuestiones sobre el papel diferencial del género en las estrategias empleadas durante la experiencia de cibervictimización, siendo necesarios próximos trabajos que examinen los mecanismos específicos que difieren en la relación entre IE y cibervictimización entre chicos y chicas.

A pesar de que el presente estudio realiza una contribución novedosa a la literatura actual, existen varias limitaciones que deberían abordarse en futuras investigaciones. Primero, aunque nuestros datos proporcionan evidencia preliminar sobre el papel moderador del género para predecir la experiencia de cibervictimización, la naturaleza transversal de nuestro diseño hace imposible determinar la dirección de causalidad en las relaciones. Próximos trabajos prospectivos o de diseño longitudinal ayudarían a dilucidar dicha causalidad. Además, es importante subrayar que la población adolescente evaluada está basada en una muestra de conveniencia, lo que dificultaría la generalización de los resultados de este estudio. En posteriores investigaciones debería emplearse un diseño aleatorio o incluir muestras adolescentes con problemas psicológicos clínicamente asociados a la experiencia de cibervictimización, lo cual incrementaría el grado de generalización de nuestros hallazgos. Otra posible limitación ha sido el uso de medidas auto-informadas, las cuales pueden ser objeto de deseabilidad social. En futuras investigaciones se deberían replicar estos hallazgos utilizando una mayor amplitud de acercamientos evaluativos, empleando múltiples fuentes de medición (p. ej.: padres, educadores, compañeros), así como otras medidas de cibervictimización (p. ej.: el cuestionario de cibervictimización (CBV) (Alvarez, Dobarro, & Nuñez, 2015); además, en nuestro estudio empleamos una medida de auto-informe de IE. A pesar de que estos instrumentos son ampliamente usados en la literatura científica, el uso combinado con las nuevas medidas de IE de habilidad basadas en criterios de ejecución incrementaría nuestro conocimiento, más allá de lo que permite el instrumento WLEIS, no solo para entender el efecto independiente o de interacción entre la IE percibida y la IE como habilidad, sino permitiendo proporcionar información para próximas intervenciones profesionales centradas en cómo el conocimiento emocional, la auto-eficacia emocional y las habilidades emocionales ayudan a reducir las consecuencias negativas de la cibervictimización. Finalmente, la inclusión, tanto de medidas de personalidad (p. ej.: los cinco grandes) como de habilidades sociales, proporcionaría una perspectiva más amplia y facilitaría nueva información sobre el papel interactivo que la IE, los rasgos de personalidad y las habilidades sociales podrían tender en reducir los síntomas negativos asociados a la cibervictimización.

A pesar de estas limitaciones, nuestro estudio ha proporcionado evidencia empírica de que la IE está asociada con la experiencia de cibervictimización. En cuanto a las implicaciones prácticas, dado que la literatura ha mostrado que las habilidades emocionales agrupadas en el constructo de IE pueden ser aprendidas y son susceptibles de ser desarrolladas en programas educativos en niños y adolescentes (Ruiz-Aranda, & al., 2013), los hallazgos encontrados podrían servir como punto de partida para el desarrollo de formación en habilidades de IE como una estrategia de intervención que pudiese complementar los programas anti-acoso escolar actuales dirigidos a reducir la experiencia de cibervictimización en adolescentes en riesgo. Si estos hallazgos se replican, los servicios de atención psicológica deberían incluir las habilidades de IE al trabajar con chicas adolescentes para prevenir el ciberacoso, ya que nuestros hallazgos sugieren que una deficiencia en regulación emocional en las adolescentes tiene un efecto combinado para incrementar la experiencia de cibervictimización. Además, otra implicación fundamental para los asesores y orientadores escolares es que la relación interactiva entre IE y género podría ser usada de forma potencial para evaluaciones de cribado con la intención de identificar a estudiantes potenciales que, después de experimentar comportamientos de ciberacoso, podrían estar en riesgo de cibervictimización. También, como Lomas y otros (2002) argumentan, la detección e identificación de factores de riesgos relacionados con las víctimas de ciberacoso escolar ayudaría a cambiar el papel de los profesionales de la enseñanza, moviéndose desde un papel más «policial», dirigido a inhibir comportamientos disruptivos y evitando la aparición de comportamientos de ciberacoso escolar, a un papel más activo, dirigido a desarrollar habilidades emocionales y estrategias de regulación emocional tanto de los acosadores como de sus victimas. Sin embargo, dado que hasta la fecha los programas preventivos y de intervención, dirigidos a incrementar las habilidades de IE se han implementado en muestras de adolescentes sin problemática de acoso, las futuras investigaciones deberían examinar de forma específica la eficacia de estos programas de mejora de IE en adolescentes en riesgo de cibervictimización. Algunos trabajos preliminares han mostrado la efectividad de las intervenciones en IE en adolescentes españoles para reducir sus niveles de agresiones físicas y verbales o la hostilidad, así como incrementar sus niveles de empatía y salud mental (Castillo, Salguero, Fernandez-Berrocal, & Balluerka, 2013). Por tanto, es tentativo pensar que programas de intervención similares pueden ser empleados para reducir el distrés psicológico y los síntomas negativos de aquellos adolescentes en riesgo de cibervictimización entre sus iguales.

En conclusión, nuestros hallazgos arrojan luz sobre la importancia de considerar las habilidades de IE para el diseño preventivo de programas anti-acoso escolar a la vez que proporcionan evidencia preliminar para el uso futuro de enfoques adaptados por géneros para trabajar la cibervictimización, siendo potencialmente una manera más efectiva de afrontar el estrés causado por los comportamientos de cibervictimización.

Apoyos

Esta investigación fue realizada en el marco del Proyecto de Investigación «El perdón como elemento protector ante el suicidio y el desajuste psicológico en adolescentes víctimas de acoso escolar» financiado por la Universidad de Málaga (PPIT.UMA.B1.2017/23).

Referencias

Aiken, L.S., & West, S.G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Alvarez-Garcia, D., Dobarro, A., & Nuñez, J.C. (2015). Validez y fiabilidad del cuestionario de cibervictimización en estudiantes de Secundaria. Aula Abierta, 43(1), 32-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aula.2014.11.001

Alvarez-Garcia, D., Nuñez, J.C., Dobarro, A., & Rodriguez, C. (2015). Risk factors associated with cybervictimization in adolescence. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 15(3), 226-235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2015.03.002

Baroncelli, A., & Ciucci, E. (2014). Unique effects of different components of trait emotional intelligence in traditional bullying and cyberbullying. Journal of Adolescence, 37(6), 807- 815. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.05.009

Beckman, L., Hagquist, C., & Hellström, L. (2012). Does the association with psychosomatic health problems differ between cyberbullying and traditional bullying? Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 17, 421-434. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2012.704228

Book, A.S., Volk, A.A., & Hosker, A. (2012). Adolescent bullying and personality: An adaptive approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 218-223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.028

Brackett, M.A., Rivers, S.E., Shiffman, S., Lerner, N., & Salovey, P. (2006). Relating emotional abilities to social functioning: A comparison of self-report and performance measures of Emotional Intelligence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(4), 780-795. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.780

Brighi, A., Guarini, A., Melotti, G., Galli, S., & Genta, M.L. (2012). Predictors of victimisation across direct bullying, indirect bullying and cyberbullying. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 17(3-4), 375-388.

Carbone-Lopez, K., Esbensen, F., & Brick, B.T. (2010). Correlates and consequences of peer victimization: Gender differences in direct and indirect forms of bullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 8, 332-350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204010362954

Casas, J.A., Del Rey, R., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2013). Bullying and cyberbullying: Convergent and divergent predictor variables. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 580-587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.015

Castillo, R., Salguero, J.M., Fernandez-Berrocal, P., & Balluerka, N. (2013). Effects of an emotional intelligence intervention on aggression and empathy among adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 883-892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.07.001

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd Ed.). Hilldsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Del Rey, R., Casas, J.A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Smith, P., … Plichta, P. (2015). Structural validation and cross-cultural robustness of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 141-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.065

Del Rey, R., Elipe, P., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2012). Bullying and cyberbullying: Overlapping and predictive value of the co-occurrence. Psicothema, 24, 608-613.

Dredge, R., Gleeson, J., & Garcia, X.P. (2014). Cyberbullying in social networking sites: an adolescent victim’s perspective. Computer and Human Behaviour, 36, 13-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.026

Elipe, P., De-la-Oliva, M., & Del Rey, R. (2017). Homophobicbullying and cyberbullying: Study of a silenced problem. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(5), 672-686. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2017.1333809

Elipe, P., Mora-Merchan, J.A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Casas, J.A. (2015). Perceived emotional intelligence as a moderator variable between cybervictimization and its emotional impact. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 486. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00486

Extremera, N., Duran, A., & Rey, L. (2007). Perceived emotional intelligence and dispositional optimism-pessimism: Analyzing their role in predicting psychological adjustment among adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 1069-1079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.014

Extremera, N., Quintana-Orts, C., Mérida-López, S., & Rey, L. (2018). Cyberbullying victimization, self-esteem and suicidal ideation in adolescence: Does emotional intelligence play a buffering role? Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 367. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00367

Fernandez-Berrocal, P., & Extremera, N. (2008). A review of trait meta-mood research. In M.A. Columbus (Ed.), Advances in Psychology Research (pp.17-45). San Francisco: Nova Science.

Fernandez-Berrocal, P., & Extremera, N. (2016). Ability Emotional Intelligence, Depression, and Well-Being. Emotion Review, 8(4), 311-315. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073916650494

Garaibordobil, M., & Oñederra, J.A. (2010). Inteligencia emocional en las víctimas de acoso escolar y en los agresores [Emotional intelligence in victims of school bullying and in aggressors]. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 3(2), 243-256.

Gini, G., & Espelage, D.L. (2014). Peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide risk in children and adolescents. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 312, 545-546. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.3212

Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Hymel, S. (2014). Moral disengagement among children and youth: A meta-analytic review of links to aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 40, 56-68. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21502

Hill, P.L., Heffernan, M.E., & Allemand, M. (2015). Forgiveness and Subjective Well-Being: Discussing Mechanisms, Contexts, and Rationales. In L.L. Toussaint (Ed.). Forgiveness and Health (pp. 155-169). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9993-5_11

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J.W. (2009). Bullying beyond the schoolyard: Preventing and responding to cyberbullying. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Katzer, C., Fetchenhauer, D., & Belschack, F. (2009). Cyberbullying: who are the victims? A comparison of victimization in Internet chatrooms and victimization in school. Journal of Media Psychology, 21(1), 25-36. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105.21.1.25

Kessler R.C., & McLeod J.D. (1984). Sex differences in vulnerability to undesirable life events. American Sociological Review, 49, 620-631. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095420

Kowalski, R.M., Giumetti, G.W., Schroeder, A.N., & Lattanner, M.R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1073-1137. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035618

Law, K.S., Wong, C.S., & Song, L.J. (2004). The construct and criterion validity of emotional intelligence and its potential utility for management studies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 483-496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.483

Li, Q. (2006). Cyberbullying in schools: A research on gender differences. School Psychology International, 27, 157-170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034306064547

Lomas, J., Stough, C., Hansen, K., & Downey, L.A. (2012). Brief report: Emotional intelligence, victimization and bullying in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 207-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.03.002