Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

The music that children are exposed to in their everyday lives plays an important role in shaping the way they interpret the world around them, and television soundtracks are, together with their direct experience of reality, one of the most significant sources of such input. This work is part of a broader research project that looks at what kind of music children listen to in a sample of Latin American and Spanish TV programmes. More specifically, this study focuses on children’s programmes in Spain, and was addressed using a semiotic theoretical framework with a quantitative and musical approach. The programme «Los Lunnis» was chosen as the subject of a preliminary study, which consisted in applying 90 templates and then analysing them in terms of the musical content. The results show that the programme uses music both as the leading figure and as a background element. The most common texture is the accompanied monody and the use of voice, and there is a predominance of electronic instrumental sounds, binary stress and major modes with modulations. Musical pieces are sometimes truncated and rhythmically the music is quite poor; the style used is predominantly that of foreign popular music, with a few allusions to the classical style and to incidental music. The data reveal the presence of music in cultural and patrimonial aspects, as well as in cognitive construction, which were not taken into account in studies on the influence of TV in Spain. Such aspects do emerge, however, when they are reviewed from the perspective of semiotics, musical representation, formal analysis and restructuring theories.

1. Introduction

In the twentieth century, music emerged as a powerful new force that was to reshape the borders of a number of areas including aesthetics, expression and communication. This redefinition of course also had significant effects on the field of education. Additionally, this new sonic space, widely used by the avant-garde artistic movements of the twentieth century, has been a key element for the mass media such as the radio, cinema and, more especially the one dealt with here, namely television. Yet, despite its importance and repercussions, it has received very little attention from education as a discipline. Some of the most important works found in a review of the Spanish literature on children’s television include those by Vallejo-Nágera (1987), De Moragas (1991), Ferrés (1994), Orozco (1996), Pablo de Río (1997), Aguaded (2005), Pintado (2005) and Reig (2005). Of the studies that were consulted, the «White Book: education in the audiovisual setting» (CAC, 2003) and «The Pigmalión Report» (Del Río, Álvarez & Del Río, 2004) contain a great deal of information about Spain, as well as some proposals for action. The first of these two works studies the context of the mass media, together with their industry, contents, consumption and relation with education. In its conclusions, the Pigmalión Report recommends using global views that allow cultural proposals and the needs of childhood development to be integrated. To achieve this, researchers are asked to describe, explain and propose reliable alternatives involving new designs based on the evaluation of TV programmes (Del Río, Álvarez and Del Río, 2004). In the international domain, Cohen (2005) recommended a method for gaining a better understanding of the overall content of television and its local diffusion. This proposal consisted in examining three variables: 1) who selects the contents and for whom; 2) the proportion of local material to be included within the foreign content; and 3) how the latter is adapted to local viewing (Cohen, 2005). All the reports speak of an excessive exposure to television and poorly defined criteria for selecting and processing its contents. The object of our study is the music that appears in the «television diet», which is affected by the issues outlined above and requires specific forms of analysis to be able to study it because music speaks using its own particular language (Porta, 2005: 285). A soundtrack consists of music, sound and noises, with which it produces effects on the audible thoughts and on the characteristics of listening (Schaeffer, 1966; Schafer, 1977; Delalande, 2004; Sloboda, 2005). One of the elements to be taken into account from the perspective of education is sound. This element of expression, which became liberated in the twentieth century, as shown by the Theory of Art (Cage, 1961; Hauser, 1963), is crucial in the production of TV programmes. The second element to be borne in mind owing to its presence and repercussions in everyday life is how sound is recorded and published on a material support (Delalande, 2004: 19). The third element is the nature of the actual medium, in our case, television. With regard to the generation of paradigms, Stiegler (1989: 235) spoke about the effect produced by «memory technologies», such as television, because they construct the coherence of their discourse from a combination of techniques, social practices and sound shapes. When we speak of children’s sonic environment, a review of the international literature shows that most of the studies are conducted as laboratory experiments that cover artificial realities in groups determined by their learning characteristics or the fact that they are a risk population in schools (Ward-Steinman, 2006; Burnard, 2008) or by their eating habits and health (Ostbyeit, 1993). Music has also been linked to reading skills (Register, 2004) or violence (Peterson, 2000), among other things. Some of the most important works on television music include those by Beckers (1993) in Germany, Bixler (2000) in England or Magdanz (2001) in Canada. Others include those carried out on the programme «Sesame Street», and more especially the study entitled «Musical Analysis of Sesame Street» conducted by McGuire (2001). With respect to the influence of the soundtrack as music from the everyday environment and its relationships with identity, Brown (2008) reviewed the need to integrate fields of research taking into account the production of consumption, the production of culture and the cultures resulting from this process of hybridisation. The same author also underlined the need to integrate this designer popular music within research. Finally, one important contribution on the subject of the globalisation of music that should be highlighted is the work by Aguilar (2001), which deals with preserving cultural products in changes and migrations that, according to the author, offer challenges for musicians and educators alike. She sees the effects of the media production on cultural phenomena as being selective, incomplete and inaccurate, and recommends the use of music that presents a valid image of itself. Likewise, she also urges musical and educational communities to offer a representation of musical culture that includes its roots and transformations. In Spain, although there are very few lines of research in this direction, some of them are followed by our research group, such as the work by Ocaña and Reyes (2010) on the programmes shown on Canal Sur. Nevertheless, music on television is more commonly reviewed as an educational tool to help learning (Eufonia 12, 1998; Comunicar 23, 2004).

From the psychological approaches, some of the most significant contributions have been those made by Cognitive Psychology concerning information processing and the Restructuring Theories, both of which are clearly based on «anti-associationist» concepts defended by authors like Piaget, Vygotsky or the Gestalt School. The key difference between the two lies in the unit of analysis that they use: while the first is elementarist, the cognitive approach is based on molar units (Pozo, 1989: 166). One important point to be highlighted in this second approach is Vygotsky's socio-historic theory, which has been reinterpreted and adapted so that it can be applied to audiovisual comprehension (Korac, 1988). In his works on the use of television in education, De Pablos (1986) studied the Russian author and underlined some relevant elements of his work: 1) Mental processes can be explained by the instruments and signs that act as mediators; he therefore defends the study of the communicative nature of signs as holders of meaning. 2) From a semiotic point of view, internalisation is a process of gaining command over the different forms of external signs (codes). 3) Today, the semiotic offer has expanded to an unbelievable extent, so that, in addition to speech, it has also become important to be able to use other codes. Children perceive the world through the senses, speech and other codes in a process that goes from social speech (the mother tongue) to inner speech by way of egocentric speech. Hence, it could be said that television music follows this same trajectory and forms a semiotic instrument that the subject incorporates within his or her repertoire of inner dialogue for interpreting reality. Finally, and to end this brief review of music and television, it should be noted that there are no empirical indicators that ensure a good knowledge of the field of study.

1.1. Presentation of the problem

The music used every day on television provides children with cognitive, social, emotional and patrimonial elements. It is therefore important for both academics and researchers to understand it so as to be able to:

1) Match curricula to these modes, media and musical contents.

2) Take on the educational commitment to be familiar with the music offered on television.

3) Lay down guidelines that allow high-quality television programmes to be produced.

4) Offer alternatives in both the educational domain and in terms of musical and audiovisual production.

1.2. Purpose and aims of the study

This work studies the soundtrack of the children's television programme with the largest audience in Spain, i.e. «Los Lunnis», which is produced by Televisión Española (TVE) and is broadcast every day from 7:30 to 9:30 am, the episodes from each week being shown again on Saturday mornings. Our intention is to find out what music is used on the most important public free-to-air television channel in Spain. «Los Lunnis» is the only children's programme offered by TVE and it is broadcast on its second channel and is financed by public funding. In order to analyse it we developed a system for coding and categorising musical material and the findings were to be used in a later (still to be initiated) phase involving the search for alternatives. In our study, the aim is to determine what music the viewers of TVE listen to and what it is like.

1.2.1. What is listened to?

This first approach will provide us with the traits that allow the soundtrack to be classified according to an objective pattern of measurement. Our questions are: What musical sounds are used and what types and families do they belong to? What tempo and metre are used? How do the pieces of music begin? What pace and intensity do they have? What genres and styles do they display? What keys are most frequently used? How do the pieces of music end? How prominent is the soundtrack in the programme?

1.2.2. What is the music like?

The second approach has to do with the internal elements of the music in the television landscape (Atienza, 2008). In order to understand their musical and discursive meaning, we divided the programme into three sections, namely in-house (locally produced) material, advertising and cartoons. Our research questions were: How is the soundtrack constructed in the three sections? What are its musical characteristics? What are the songs about? How is the music related with the dramatic action, the scenes and the synchrony between them?

2. Material and methods

This work is part of a broader research project aimed at determining what children listen to in a sample of Hispanic TV programmes. Umberto Eco's (1978) model was used as the semiotic framework of reference. Gómez-Ariza's (2000) model was specifically utilised in the construction of the listening template and, lastly, Zamacois’ (1968) analysis of Musical Form was also employed.

2.1. Sample

The programming block that was selected, «Los Lunnis», consists of three sections with different proportions: 25% in-house programme material, 63% cartoons and 12% advertising. The sample is made up of the ten hours of the programme that were broadcast during one week (18 to 22 February 2008) in which no special events took place. The potential range of viewers’ ages was relatively wide. The sample comprised Spanish and US cartoons, advertising (commercials advertising food/sweets and toys) and lastly the in-house programmes, which included the opening and closing sequences, bumpers, dramatisations, reports, songs, news and interviews.

2.2. Design, instruments and data collection

To conduct this research a listening analysis tool was developed ad hoc and validated before applying it in the study (Porta & Ferrández, 2009). Sampling was performed by means of the expert choice procedure to ensure that musical elements from all three sections of the programme that were relevant to the first analysis were all included. Furthermore, the sample was complemented with 10 excerpts in order to establish the target musical material used in the programme. Three different instruments were used in the research, the first two being included within the same template. These were: 1) Data from the sample; 2) Musical categories; and 3) The musical analysis itself.

The first instrument gathered data about the rater, data record, country, programme, section, date, duration and the musical elements of the programme (opening sequence, signature tune, closing sequence, bumpers, songs, dramatisations, scenes, reports and excerpts). The second instrument consisted of 14 categories divided into 59 codes, which had «yes/no» or «undetermined» (ND) as possible answers. This tool divided the variables into different categories that could be measured in a dichotomous way, depending on whether they appeared in the selected unit or not (Porta & Ferrández, 2009). In the Latin American study that this work is part of, a joint validation session was held so that programmes, countries and contents that were common to the whole research study could be reviewed by a panel of experts. A double interrater validation was also carried out, the results showing a mean percentage of agreement above 80%, which was considered to indicate a very high level of reliability of the instrument in general.

- Approach 1. What do they listen to? The template was applied to the programme «Los Lunnis» by means of 90 units of analysis and a full examination of the form of 23 pieces of music.

- Approach 2. What is the music like? Since not everything can be answered dichotomously, a new approach was developed to search for the molar elements (Pozo, 1989: 166-167) and their meaning, that is to say, the characteristics of the music, in: 1) The in-house programmes: study of the opening theme music, closing themes, bumpers and songs; 2) Cartoons: the series «Berni», «Clifort» and «Pocoyó»; and 3) Advertising: commercials for toys and food/sweets. Finally, in order to study the intentional musical options from the programme, five diegetic songs were selected (that is, songs performed by the leading characters in the programme).

From these two approaches we sought to determine the options and musical elements used in children’s television programmes, that is, the place that music speaks from (Porta, 2007: 22). This will be the first step towards discovering the unexplored educational space of music and its communicative presence as a discourse that conveys meaning (Talens, 1994).

3. Results

3.1. What is listened to? The musical categories

The 14 indicators were applied to the five programmes broadcast during the week by means of 90 templates. The percentages indicate the measure of the dichotomous feature «yes/no» and «undetermined» that reflected factors involving mainly brevity and inaudibility. The most notable results were: Musical sound/non-musical sound. The programme often uses musical sound as well as a high percentage of non-musical sound consisting of noises and sound effects. Type of sound. The music studied is 70% electronic, 15.5% acoustic and 10,5% combinations. Groups of instruments from all the families can be heard, although there is a predominance of stringed instruments and electronic imitative sound. Voice and instruments. It was observed that 42% of the music was instrumental and the rest was vocal, mainly in groups (38.9%) with a prevalence of male voices (10%) over female voices (2.2%). Metre and rhythm. With regard to the type of stress, the results were binary in 88% of cases versus 1.4% of ternary, with occasional cases of blends. Type of beginning. The pieces of music had anacrusic beginnings in 57% of cases versus 37.8% thetic beginnings and very few cases of acephalous beginnings. Dynamics. The use of intensity was mostly flat (81%), with variations in 18.9% of the melodies that were listened to. Agogic. As far as variations in pace are concerned, the music in this programme was again seen to opt for no variations in tempo in 88.9% of cases versus 3.3% of cases in which it speeds up and a slightly higher percentage that uses ritardando. Genre and style. Of all the different genres and styles that were listened to, the most common was popular music (77.8%), which included pop, rock and blues, together with other popular subgenres and styles from the twentieth century. Within traditional music, 13.3% comes from other cultures while only 1.1% is from the local one. Sound organisation. In the sample, the major key predominated over the minor key (88.9% vs. 6.7%, respectively). Cadences. Resolutions, regardless of the section of the programme in which they appear, were mostly conclusive (56.7%), while 25.6% were suspensive and 10% truncated melodies. This last type occurred in segments from advertising or in adjustments made to the continuity of the programme that cuts its melodies short in order to move on to the next programme. Sound texture. The texture in the sample was the accompanied monody (64.4%), in contrast to singing voices, which can be either homophonic (4.4%) or polyphonic (12.9%). Sound plane. The music often played a leading role in the programme, only appearing as the background to scenes and dramatisations in just 25.6% of the cases in the sample.

3.2. What is the music like? The musical contents

In order to study what the music in the programmes is like, the template was applied to 23 pieces of music from the three sections, bearing in mind the length of the work and its musical form. Thus, in the long pieces of music, the first and last phrases, two intermediate excerpts and an assessment of the whole piece were studied for the five days of the week.

3.2.1. In-house programmes

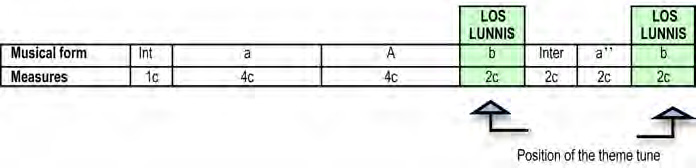

The results of the analysis of the in-house material (opening themes, closing music, bumpers and songs), cartoons and advertising were as follows: the opening theme music of the programme, which was repeated on each of the five days of the week, was studied using 15 templates, three for each day. It is a short tune lasting 34”, with an anacrusic beginning, in G Major, and a tempo of 144 beats per minute. It is sung by an adult soloist and groups of vocalists accompanied by instruments (Figure 1). This tune is heard in links, the presentation of dramatisations, subsections, bumpers and closing themes, and in each case different versions are used (instrumental, vocal, semi-spoken) and could be complete, fractioned or played as a repeating loop.

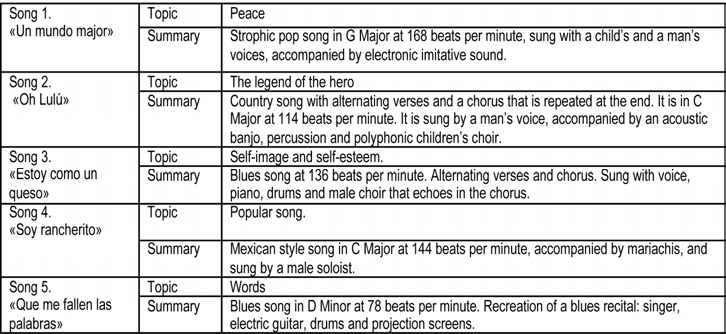

In the closing themes, the programme uses different parts of the tune from the opening theme, while maintaining the motif from the signature tune, and they vary in length: 4”, 36” and 1’33”. This last closing theme, for example, is repeated in a loop while the last dramatic action in the programme is finishing, and ends with the signature tune shifting from the background to the foreground. On two of the five days, it was truncated and replaced by the next programme, which was already being announced, or by the «unrelenting commercials» (González Requena, 1988). Eight of the bumpers lasted 7” and, again, took up the identifying elements of the opening theme tune and modified them with different arrangements and effects. There were many different songs and melodies in the programme. In this section we have selected the leading songs performed by the characters in different settings such as little theatres, pubs, television studios or virtual sets. These songs represent the different options that exist in television as regards form, genre and style, as well as their connection with the scene, the choice of subject matters and the synchrony between text and images. The five diegetic songs from the week (Table 1) were studied using 25 templates – five for each song: one for the first and last musical phrases, two intermediate excerpts and one assessment of the whole piece.

3.2.2. Advertising

Advertising was studied using a single template for each commercial or two when there was a notable change in the music. The common features were: average length 20”; tempo of about 123 beats per minute; instrumental, electronic imitative sound; binary; no variation in the dynamics or in the rhythm; pop and film genre; in a major key; and the music was background music that sometimes became the leading, foreground figure. In the case of «I’m pocket» two templates were applied due to the significant change that takes place between Excerpt 1 (from 1” to 18”) and Excerpt 2 (from 18” to 20”), where there is a change in the music to highlight the theme tune.

3.2.3. Cartoons

Lastly, the cartoons were studied by taking an excerpt every 45” until the whole episode was covered. The following is a summary of «Berni» and «Pocoyó»:

- «Berni» is a cartoon series from 2006 without dialogues, produced by BRB Internacional S.A., which is about sports and features «Berni», a polar bear. It is made up of 3’ episodes that are strung together to fill the whole broadcast. The study was conducted by means of six templates. The episode included both everyday noises and sounds and electronic imitative sound. The music was a combination of short sequences in the Classical style with others more closely related to the incidental music used in films. It was written in a major key and was instrumental, with no variation in the rhythm or in the dynamics, and both conclusive and suspensive cadences were employed. There were some modulations to other tones, the sound texture was the accompanied monody and the music appeared as background music, except for just one occasion on which it progressed from the background to the leading figure.

- «Pocoyo». This is a Spanish cartoon series from 2005 produced by Zinkia Entertainment which features Pocoyo, a little boy whose adventures involve discovering and interacting with the world around him. Each episode lasts 6’45” and the narrative action in this episode was about discovering one's own fingerprints and those of others. The episode made use of both non-musical and musical sound from the pop environment with traces of incidental music from the film world. The music was electronic, instrumental, binary and thetic, with variations in the dynamics and the rhythm. The tempo was linked with the characters as they appeared in the scenes: «Pocoyo» at 156 beats per minute, «Elly» (the elephant) at 90 and «Pato» at 114. Major and minor keys were both used, with different cadences and modulations. The sound texture was the accompanied monody, and there were also rhythmic ostinatos and sound effects. The music was present in the background and also as the leading figure, and the musical motifs were the leitmotif of the characters.

4. Discussion

In answer to the aims and research questions of this study, we can say that: What is listened to? The programme «Los Lunnis» has a soundtrack that utilises musical sound (preferably electronic) that is divided into fairly equal proportions of instrumental and vocal music sung by groups of voices. Its music is binary, popular, anacrusic, with flat dynamics, no variations in the pace and the texture is the accompanied monody. It uses the major key with modulations to other keys, it resolves by means of conclusive cadences, and the music is predominantly the leading figure. There is a high percentage of non-musical sound consisting of noises and sound effects.

What is the music like? A preliminary evaluation of the musical analysis reveals that the diegetic music of the in-house material (25% of the programme) is made up of strophic songs with phrases eight bars long. They are listened to as whole pieces and resolve in a highly conclusive manner with all the closing elements available, sometimes using both polyphonic and homophonic polyphony. There is a certain lack of rhythmic richness, with a strong presence of binary stress. The intensity has no nuances and is controlled using a mixing desk, with shifts from the background towards the leading figure usually carried out by means of non-musical narrative strategies. The synchrony between the music and images in the programme is good and the instruments and sound objects are coherent with its soundtrack and stage spaces. Its tempos range from 78 to 168 beats per minute, with no variations in the rhythm and it uses the keys of CMaj, GMaj, DMaj and Dminor, which sometimes modulate to other keys. With regard to style and how it is linked with identity, the programme opts for foreign popular music. Its timbral composition is predominantly electronic with some acoustic elements of the popular music in question. This is also reflected in its harmonic and melodic structures, which are often accompanied by choreographic arrangements and an appropriate wardrobe and set design. Advertising, which takes up 12% of the total time, has a soundtrack with an average pace of 123 beats per minute. It is predominantly instrumental, with electronic imitative sounds, and is binary and thetic with no variations in the dynamics or in the rhythm. It has no defined style, sometimes using the film genre and non-musical noises and sounds, and appears in the major key in the form of background music. Cartoons, which account for 63% of the programme, use both music and non-musical sounds and noises to reinforce the dramatic action with the aid of changes in key and tempo, as well as the use of suspensive effects and small leitmotifs to define characters. A study of the melodies used in the programme shows that the most common one is that of the actual signature tune, which appears as the introduction and at the end of each section, dramatisation and episode. Truncated pieces of music are also heard, especially in commercials and at the end of episodes. Another point to be highlighted, due to its specific weight in cartoons, is the preponderance of non-diegetic music and a wide variety of both musical and non-musical sounds.

Selection of genres and styles. Music from before the twentieth century is scarce, with a few exceptions in cartoons and parodies of the programme itself, in which there are some allusions to the classical style. Instead, the style chosen for the programme is popular music, the leading songs of the week being a ranchera, a country song, two blues and a pop song. In the sample that was studied, the music is always someone else's and never one’s own work. Children’s television programmes require proximity contents (De Moragas, 1991), yet what is offered is a multicultural space that has been filled with exotic material and no longer contains any local elements. From an educational point of view, this option questions identity because music speaks about oneself, about others and to others (Porta, 2004: 112). Valuing diversity means recognising what is one's own at an early age, because this egocentric speech (Vygotsky, 1981: 162) will eventually give rise to inner speech, and music is part of the cognitive construction.

Incidental music. Music is linked to the action in all the different sections of the programme in the form of tiny fragments of music that remind the child of the world of films. This is the case of the parody of «Lunicienta» or that of «Psycho», or the repeated references to one of the last American heroes: «Indiana Jones». In «Pocoyo» there are leitmotivs associated to its characters, tonal and non-tonal music, modulations, variations in the dynamics and rhythm, as well as shifts from leading figure to background, and vice versa. And all this takes place within an expressive and aesthetic dialogue in space and time that has in mind a small, intelligent child who interacts with the television media through music.

Soundtracks of films and television programmes have an influence in education and also a social responsibility as part of the construction of children’s consciousness because they make an important contribution to the development of their cognitive, social, expressive, aesthetic and, later, critical capabilities. This article outlines some of the aspects that have received little attention from researchers in studies on the music used on television and its influence in childhood, but which become more apparent when they are studied from the perspective of semiotics, musical representation, formal analysis and restructuring theories. The conclusions point to the following as lines of action that should be followed: value must be given to the social, cultural and patrimonial functions of music on television because music speaks about others and to others. And it does so by means of representation: i.e. what is listened to; by means of edition: i.e. how the continuity of what is seen and heard is produced, articulated and created; and also from the position of the speaker: i.e. the television production, its meaning and influence. Television as a medium can favour the reconstruction of musical contents and their understanding, as well as the development of taste and the enhancement of the immaterial heritage. Thus, in future studies broader units of analysis will have to be defined, as proposed by cognitive psychology and the musical tendencies of the twentieth century. This study has responded to some of them, which refer to cultural heritage, identity and otherness, that is, interpretations of diversity and relationships with the environment in which music is far more than just an audiovisual medium – it is a vehicle, a means and a content of expression, representation and dialogue with the world.

Notes

1 The indicators, definitions and review of the results were discussed and agreed on at the II Encuentro investigador sobre la banda sonora de la television infantil y juvenil en el ámbito latinoamericano. Variables, impacto e influencia en el patrimonio sonoro» held at the University of LANUS, Buenos Aires from 14th to 18th May 2008. The conference was attended by representatives from three Spanish (UV, UG and UJI) and five Latin American universities (U LANUS, UT, UNIRIO, US, UNE).

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible thanks to funding through projects: 1) R&D (2007/2010) «Las bandas sonoras de la televisión infantil 2007 y 2008 en España. Canal 9. Televisión Valenciana y TVE (P1 1A2007-17); and 2) The Programme for Inter-university Cooperation and Scientific Research between Spain and Latin America project entitled «La música y la escucha de la TV infantil en el ámbito iberoamericano. Análisis cuantitativo de variables y estudio comparado» (A/018075/08).

References

Aguaded, J.I. (2004). Música y Comunicación. Comunicar, 23; 9-22.

Atienza, R. (2007). Paisajes sonoros. Ambientes sonoros urbanos. Encuentro Iberoamericano sobre Paisajes Sonoros. Madrid: Auditorio Nacional.

Beckers, R. (1993). Walkman, Fernsehen, Lieblingsmusik: Merkmale musikalischer Frühsozialisation, Mu-sikpädagogische Forschung, 14; 11.

Bixler, B. (2000). Let's Make Music School Library Journal, 46; 11; 72.

Brown, A.R. (2008). Popular Music Cultures, Media and Youth Consumption: Towards an Integration of Structure, Culture and Agency. Sociology Compass, 2 (2); 388-408.

Burnard, P.; Dillon, S. & al. (2008). Inclusive Pedagogies in Music Education: A Comparative Study of Music Teachers' Perspectives from four Countries. International Journal of Music Education, 26(2); 109-126.

CAC, (2003). Libro Blanco: La educación en el entorno audiovisual. Consejo Audiovisual de Cataluña.

Cage, J. (1961). Silence. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Cohen, J. (2005). Global and Local Viewing Experiences in the Age of Multichannel Television: The Israeli Experience. Communication Theory, 15 (4); 437-455.

De Moragas, M. (1991). Teorías de la comunicación. Barcelona: Gustavo Gilli.

De Pablos, J. (1986). Cine y enseñanza. Madrid: CIDE (MEC).

Del Carmen, M. (2001). Heritage: The Survival of Cultural Traditions in a Changing World. International Journal of Music Education, 37 (1); 67-71.

Del Río, P. (1997). Creciendo con la televisión. Cultura y Educación, 5; 23-95.

Del Río, P.& Alvarez, A. & Del Río, M. (2004). Pigmalión. Informe sobre el impacto de la televisión en la infancia. Madrid: Fundación Infancia Aprendizaje.

Delalande, F. (2004). La enseñanza de la música en la era de las nuevas tecnologías. Comunicar, 23; 20-24.

Eco, U. & Cantarell, F. (1978). La estructura ausente: Introducción a la semiótica. Madrid: Lumen.

Ferres, J. (1994): Televisión y educación, Madrid: Paidós.

Gómez-Ariza, C. (2000). Determinants of Musical Representation. Cognitiva, 12, 1; 89-110.

Hauser, A. (1963). Historia social de la literatura y el arte. Madrid: Guadarrama.

Korac, N. (1988). Los medios de comunicación visual y el desarrollo cognoscitivo, Universidad de Belgrado.

Magdanz, T. (2001). Classical Music: Is anyone listening? A Listener-based Approach to the Soundtrack of Ber-trand Blier's Too Beautiful for You, Discourses in music, 3, 1.

Mcguire, K.M. (2001). The Use of Music on Barney & Friends: Implications for Music Therapy

Medrano, C. (2008). La dieta televisiva y los valores: un estudio realizado con adolescentes en la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 239; 65-84.

Ocaña, A. & Reyes, M.L. (2010). El imaginario sonoro de la población infantil andaluza: análisis musical de «La Banda». Comunicar, 35; 193-200.

Orozco, G. (1996). Miradas latinoamericanas a la televisión. México: Universidad Iberoamericana.

Ostbye, T.; Pomerleau, J. & al. (1993). Food and Nutrition in Canadian Prime-time Television Commercials. Canadian Journal of Public Health-Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique, 84(6); 370-374.

Peterson, J.L. & Newman, R. (2000). Helping to curb youth violence: The APA-MTV «warning signs» initiative. Professional Psychology-Research and Practice, 31(5); 509-514.

Pintado, J, (2005). Lo ideal y lo real en TV: calidad, formatos y representación. Comunicar, 25; 101-108.

Porta, A. & Ferrández, R. (2009). Elaboración de un instrumento para conocer las características de la banda sonora de la programación infantil de televisión. Relieve, 15, 2. (www.uv.es/relieve/v15n2/relie¬vev15n2_¬6.htm) (25-11-2009).

Porta, A. (2004). Musical Expression as an Exercise in Freedom, ISME 26. International Society for Music Edu-cation. World Conference. Tenerife.

Porta, A. (2005). La escucha de un espectador de fondo. El niño ante la televisión. Comunicar,

Porta, A. (2007). Músicas públicas, escuchas privadas. Hacia una lectura de la música popular contemporánea. Aldea Global. Barcelona: UAB.

Pozo, J.I. (1989). Teorías cognitivas del aprendizaje. Madrid: Morata.

Register, D. (2004). The Effects of Live Music Groups Versus an Educational Children's television program on the emergent literacy of young children. Journal of Music Therapy, 41(1); 2-27.

Reig, R. (2005). Televisión de calidad y autorregulación de los mensajes para niños y jóvenes.

Schaeffer, P. (1966). Traté des objets musicaux. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

Schafer, M. (1977). The Tuning of the World, Toronto: McClelland and Steward.

Shuck, L.; Salerno, K. & al. (2010). Music Interferes with Learning from Television during Infancy. Infant and Child Development, 19(3); 313-331.

Sloboda, J. (2005). Exploring the Musical Mind: Cognition, Emotion, Ability, Function. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press.

Stiegler, B. (1989). La lutherie électronique et la main du pianiste, Mots/Images/Sons, Cahiers du Cirem: Rouen.

Talens, J. (1994). Escritura como simulacro: El lugar de la literatura en la era electrónica. Valencia: Eutop-ías/Epiteme.

Vallejo Nágera, A. (1987). Mi hijo ya no juega, solo ve la televisión. Madrid: Temas de hoy.

Varios (1998). Monográfico Música moderna. Eufonía, 12; 7-98.

Vygotsky, L. (1981). The Instrumental Method in Psychology. In Wertsch, J. (Ed.). The Concept of Activity in Soviet Psychology. New York: Sharpe; 134-143.

Ward-Steinman, P.M. (2006). The Development of an After-school Music Program for at-risk Children: Student Musical Preferences and Pre-service Teacher Reflections. International Journal of Music Education, 24 (1); 85-96.

Zamacois, J. (1986). Curso de formas musicales. Barcelona: Labor.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

La música de la vida cotidiana del niño tiene uno de sus referentes, junto a su experiencia real, en la banda sonora de la televisión, configurando una parte de su interpretación de la realidad. Este trabajo forma parte de una investigación más amplia sobre la escucha televisiva infantil en una muestra iberoamericana. El objetivo, conocer qué escuchan los niños en la programación infantil de «Televisión Española», ha sido estudiado desde un marco teórico semiótico con un enfoque cuantitativo y musical. El artículo presenta un resumen de los resultados obtenidos en un primer análisis del programa «Los Lunnis» mediante la aplicación de noventa plantillas y sus análisis musicales correspondientes. Estos resultados indican que el programa utiliza la música como fondo y figura, textura de monodía acompañada y utilización de la voz, predominio del sonido electrónico instrumental, acento binario y modo mayor con modulaciones. Aparecen piezas musicales cortadas y cierta pobreza rítmica, su opción estilística es la música popular no propia, con algunos guiños al estilo clásico y a la música incidental. Los datos muestran la presencia de la música en aspectos culturales, patrimoniales y de construcción cognitiva no considerados en los estudios sobre la influencia de la TV en España, pero que emergen cuando son revisados desde la semiótica, la representación musical, el análisis formal y las teorías de la reestructuración.

1. Introducción

La música ha irrumpido en el siglo XX con fuerza en el campo estético, expresivo y comunicativo modificando sus fronteras, y esta redefinición del territorio interpela a la educación. Este nuevo espacio sonoro, muy utilizado por las vanguardias artísticas del siglo XX, ha sido también el elemento de toque de los grandes medios de comunicación como la radio, el cine y, de forma destacada en el tema que nos ocupa, la televisión. Sin embargo, pese a su importancia y repercusiones, hemos reflexionado muy poco sobre ello en materia educativa. En la revisión de la literatura española sobre la televisión infantil destacan los estudios de (Vallejo-Nágera, 1987; Ferrés, 1994; Orozco, 1996; Pablo de Río, 1997; Aguaded, 2005; De Moragas, 1991; Reig, 2005; Pintado, 2005). De los trabajos consultados, «El Libro Blanco: La educación en el entorno audiovisual» (CAC, 2003) y «El Informe Pigmalión» (Del Río, Álvarez & del Río, 2004) aportan gran información sobre la televisión en España y también algunas propuestas de acción. El primero de ellos estudia el contexto mediático, su industria, contenidos, consumo y relación con la educación. En cuanto al segundo, el informe Pigmalión, en sus conclusiones recomienda utilizar visiones globales que permitan integrar las propuestas culturales y las necesidades del desarrollo del niño, por ello propone a los investigadores describir, explicar y proponer alternativas fiables basadas en el diseño y evaluación de sus programaciones (Del Río, Álvarez & del Río, 2004). En el campo internacional, Cohen (2005) recomienda una mejor comprensión del contenido global de la televisión y su difusión local examinando tres variables: 1) quién selecciona el contenido y para quién, 2) la proporción de lo local en el contenido extranjero, y finalmente 3) cómo éste último se adapta a la visión local. Todos los informes hablan de exceso de exposición televisiva y criterios poco definidos en la selección y tratamiento de sus contenidos. Nuestro objeto de estudio es la música de la dieta televisiva que participa de la problemática descrita y requiere, además, para su estudio de formas de análisis específicas porque habla desde su propio lenguaje (Porta, 2005: 285). La banda sonora se compone de música, sonido y ruidos, con los cuales produce significados, efectos en el pensamiento sonoro y también en las características de la escucha (Schafer, 1977; Schaeffer, 1966; Sloboda, 2005; Delalande, 2004). Uno de los elementos a considerar desde la educación es el sonido. Este elemento expresivo, que se libera en el siglo XX tal como nos muestra la teoría del arte (Cage, 1961; Hauser, 1963), es determinante en la producción televisiva. El segundo elemento a considerar por su presencia y repercusiones en la vida cotidiana, es la fijación y edición del sonido sobre un soporte (Delalande, 2004: 19). El tercer elemento es la naturaleza del propio soporte, en nuestro caso, la televisión. Stiegler (1989: 235) habla, a propósito de la generación de paradigmas, del efecto que producen las tecnologías de la memoria como es la televisión, porque construyen la coherencia de su discurso a partir de técnicas, prácticas sociales y formas sonoras. Cuando hablamos del entorno sonoro del niño, la revisión internacional de la literatura muestra, en su mayoría, experiencias de laboratorio que acotan realidades artificiales por rasgos de aprendizaje o población escolar de riesgo (Burnard, 2008; Ward-Steinman, 2006), hábitos alimentarios y de salud (Ostbyeit, 1993), relación de la música con habilidades de lectura (Register, 2004), con la violencia (Peterson, 2000) y otros. Sobre la música de la televisión, son de destacar los trabajos de Beckers (1993) en Alemania, Bixler (2000) en Inglaterra, Magdanz (2001) en Canadá, o los desarrollados sobre el programa «Sesame Street», destacando «Musical Analysis of Sesame Street» realizado por Mcguire (2001). Sobre la influencia de la banda sonora como música del entorno cotidiano y sus relaciones con la identidad, Brown (2008) revisa la necesidad de integración de campos de investigación contemplando la producción del consumo, de la cultura y las culturas resultantes de esta hibridación, y manifiesta la necesidad de integrar estas músicas populares de diseño en las investigaciones. Finalmente señalamos sobre el discurso de la globalización en música, la aportación de Aguilar (2001) sobre la preservación de productos culturales en cambios y migraciones que, según la autora, presentan desafíos a músicos y educadores. Observa los efectos de la producción mediática sobre fenómenos culturales, concluyendo que son selectivos, incompletos e inexactos, aconseja la utilización de músicas que proporcionen una imagen válida del yo, e insta a las comunidades musicales y educativas a ofrecer una representación de la cultura musical, que incluya sus raíces y transformaciones. En España, las líneas investigadoras son mucho más escasas, encontramos algunas de nuestro grupo investigador como las de Ocaña y Reyes (2010) sobre la programación de Canal Sur, siendo más frecuentes las revisiones de la música en la televisión como herramienta educativa de ayuda al aprendizaje (Comunicar 23, 2004; Eufonía 12, 1998).

Desde las corrientes psicológicas destacamos las aportaciones de la psicología cognitiva sobre el procesamiento de la información y las teorías de la reestructuración, ambas con una clara concepción «antiasociacionista», con autores como Piaget, Vygotsky o la Escuela de la Gestalt, y cuya diferencia clave radica en la unidad de análisis que utilizan, mientras la primera es elementarista el enfoque cognitivo parte de unidades molares (Pozo, 1989: 166). De esta última destacamos la teoría socio histórica de Vygotsky, sometida a un proceso de reinterpretación y posible aplicación a la comprensión audiovisual (Korac, 1988). De Pablos (1986) en sus trabajos sobre la televisión en la enseñanza estudia al autor ruso y destaca algunos elementos de su obra: 1) Los procesos mentales se explican por los instrumentos y signos que actúan de mediadores, para lo cual se apoya en la naturaleza comunicativa de los signos como poseedores de significado; 2) Desde una perspectiva semiótica, la interiorización es un proceso de dominio sobre las distintas formas de signos externos (códigos); 3) Actualmente la oferta semiótica se ha ampliado extraordinariamente, de manera que además del habla, ha cobrado importancia el manejo de otros códigos. El niño percibe el mundo mediante los sentidos, el habla y otros códigos, pasando del habla social (lengua materna) al habla interna por medio del habla egocéntrica. Por todo ello, podemos decir que la música de la televisión realiza este mismo recorrido, constituyéndose en un instrumento semiótico que se incorpora al repertorio del diálogo interior para interpretar la realidad. Como resumen de esta breve revisión sobre música y televisión, podemos decir que no se dispone de indicadores empíricos que aseguren un buen conocimiento del campo de estudio.

1.1. Presentación del problema

La música cotidiana de la televisión proporciona al niño elementos cognitivos, sociales, emocionales y patrimoniales, por ello, es necesario conocerla desde el entorno académico e investigador para:

1) Adecuar el currículum, también, a estos modos, soportes y contenidos musicales.

2) Asumir el compromiso educativo de conocer la música que la televisión propone.

3) Crear las vías para producir una televisión de calidad.

4) Ofrecer alternativas tanto educativas como de la producción musical y audiovisual.

1.2. Propósito del estudio y objetivos

Este trabajo estudia la banda sonora del programa infantil de mayor cobertura en España: «Los Lunnis», producido por «Televisión Española», con una emisión diaria de 7:30 a 9:30h y episodios que se repiten los sábados. Nuestra intención ha sido conocer la oferta musical del canal público de mayor audiencia de las televisiones españolas que emiten en abierto. El programa «Los Lunnis» constituye la programación infantil de «TVE», se emite por su segundo canal y está financiado con fondos públicos. Para conocerlo hemos establecido un sistema de codificación y categorización musical para, en una fase posterior todavía no iniciada, buscar alternativas. En nuestro estudio queremos saber qué y cómo es la música que ofrece «TVE» para la escucha.

1.2.1. ¿Qué se escucha?

Esta primera aproximación nos proporcionará los rasgos para clasificarla según un patrón de medida objetivo. Nuestras preguntas son: ¿Qué sonido musical utiliza y a qué tipos y familias pertenece?, ¿Qué tempo y métrica emplea? ¿Cómo son los comienzos de las piezas musicales? ¿Cuál es su velocidad e intensidad? ¿Qué géneros y estilos muestra? ¿Cuáles son sus tonalidades más frecuentes? ¿Cómo terminan las piezas musicales? ¿Qué presencia tiene la banda sonora en el programa?

1.2.2. ¿Cómo es la música?

La segunda aproximación se acerca a los elementos internos de la música en el paisaje televisivo (Atienza, 2008). Para conocer su significación musical y discursiva hemos dividido el programa en sus tres secciones: producción propia, publicidad y dibujos animados. Nuestras preguntas de investigación son: ¿Cómo está construida la banda sonora en las tres secciones? ¿Cuáles son sus características musicales? ¿De qué hablan las canciones? ¿Qué relación guarda la música con la acción dramática, la escena y su sincronía?

2. Material y métodos

Este trabajo forma parte de una investigación más amplia que tiene como objetivo conocer los contenidos musicales de la dieta televisiva en una muestra iberoamericana. El marco semiótico de referencia, utiliza el modelo de Umberto Eco (1978), como específico para la construcción de la plantilla de la escucha, el propuesto por Gómez-Ariza (2000), y por último, el análisis de la Forma Musical de Zamacois (1968).

2.1. Muestra

El programa contenedor, «Los Lunnis», consta de tres secciones con proporciones diferentes: programación propia 25 %, dibujos animados 63 % y publicidad 12 %. La muestra se compone de las 10 horas de emisión de una semana en la que no hubo acontecimientos especiales, del 18 al 22 de febrero de 2008. Su franja de edades potenciales de audiencia es relativamente amplia. Está formado en la muestra analizada, por dibujos animados españoles y de Estados Unidos, publicidad -anuncios de comida/golosina y juguetes- y por último, la programación propia -cabeceras, cierres, cortinillas, dramatizaciones, reportajes, canciones, noticias y entrevistas.

2.2. Diseño, instrumentos y recogida de datos

Para realizar este estudio se utilizó la herramienta de análisis de la escucha realizada ad hoc para esta investigación y ya validada (Porta & Ferrández, 2009). Se realizó un muestreo mediante el procedimiento de elección experta, de manera que se incluyeran los elementos de la música relevantes para un primer análisis y presentes en las tres secciones. Asimismo, se complementó con 10 cortes periódicos para conocer la oferta musical objetiva del programa. En la investigación se han utilizado tres instrumentos, los dos primeros en la misma plantilla. Se trata de: 1) Datos de la muestra; 2) Categorías musicales; 3) Análisis musical propiamente dicho.

El primero recoge los datos referidos al evaluador, ficha, país, programa, sección, fecha, duración y elementos musicales del programa (cabecera, sintonía, cierre, cortinilla, canción, dramatizaciones, escenas, reportajes y cortes periódicos). El segundo instrumento está formado por 14 categorías divididas en 59 códigos cuya respuesta es sí/no/no se puede determinar. Esta herramienta dividía las variables consideradas en categorías susceptibles de ser medidas de manera dicotómica, según aparecieran o no en la unidad seleccionada (Porta & Ferrández, 2009). En el estudio iberoamericano, del que este trabajo forma parte, se realizó una sesión de validación conjunta para la revisión de programas, países y contenidos comunes a toda la investigación por juicio de expertos y se llevó a cabo una doble validación interjueces que presentó un porcentaje de acuerdo medio superior al 80%, lo que se consideró un indicador de muy elevada fiabilidad del instrumento en general.

- Aproximación 1. ¿Qué escuchan? Quien suscribe aplicó la plantilla al programa «Los Lunnis» por medio de 90 unidades de análisis y un examen formal completo de 23 piezas musicales.

- Aproximación 2. ¿Cómo es aquello que se escucha? Sin embargo, no todo puede contestarse de forma dicotómica, por ello empleamos una nueva aproximación para encontrar los elementos molares (Pozo, 1989: 166 167), y su significado, es decir las características de la música en: 1) La programación propia: estudio de cabeceras, cierres, cortinillas y canciones; 2) Los dibujos animados: series «Berni», «Clifort» y «Pocoyó»; 3) La publicidad: anuncios de juguetes y comida/golosinas. Finalmente, para conocer las opciones musicales intencionadas del programa, seleccionamos cinco canciones diegéticas, es decir, interpretadas por los personajes en posición protagonista.

Desde estas dos aproximaciones hemos querido conocer las opciones y elementos musicales de la programación infantil de televisión, es decir, el lugar desde donde habla la música (Porta, 2007: 22). Será el primer paso para acercarnos al inexplorado espacio educativo de la música y su presencia comunicativa como discurso portador de sentido (Talens, 1994).

3. Resultados

3.1. ¿Qué se escucha? Las categorías musicales

Los 14 indicadores se aplicaron por medio de 90 plantillas a los 5 programas de la semana. Los porcentajes indican la medida de la característica dicotómica, si/no, y no se puede determinar (NPD) que recogió, principalmente, factores de brevedad e inaudibilidad. Los resultados más destacados son: Sonido musical/ sonido no musical. El programa utiliza mucho el sonido musical y un porcentaje elevado de sonido no musical por medio de ruidos y efectos sonoros. Tipo de sonido. La música estudiada es electrónica en un 70% frente a un 15,5% de acústica y un 10% de combinaciones. Se escuchan agrupaciones instrumentales de todas las familias con predominio de los instrumentos de cuerda y el sonido electrónico de imitación. La voz y los instrumentos. El 42% era instrumental y el resto vocal, preferentemente por grupos de voces 38,9% con un 10% de voz de hombre y 2,2% de mujer. Métrica y rítmica. En cuanto al tipo de acentuación, los resultados han sido binarios en un 88% frente a un 1,4 de ternario y algunos casos puntuales de amalgama. Tipo de comienzo. Las piezas musicales tienen un comienzo anacrúsico con un 57% frente al 37,8% de tético y una muy escasa representación de los comienzos acéfalos. Dinámica. La utilización de la intensidad ha sido mayoritariamente plana 81% y variaciones en el 18,9% de las melodías. Agógica. En cuanto a las variaciones de la velocidad, podemos decir que el programa ha optado, de nuevo, por tempos sin variaciones en el 88,9% frente al 3,3% de acelerando y un porcentaje levemente mayor de rittardando. Género y estilo. De todos los géneros y estilos escuchados, los más frecuentes son los populares con un 77,8% de pop, rock, blues así como otros subgéneros y estilos populares del siglo XX. Dentro de la música tradicional destacamos la presencia de músicas de otras culturas con un 13,3% frente al 1,1,% de la propia. Organización sonora. En la muestra ha predominado el modo mayor 88,9% frente al menor 6,7%. Cadencias. Las resoluciones, independientemente de la sección de la programación en que se encuentren, son mayoritariamente conclusivas con un 56,7% frente al 25,6% de suspensivas y un 10% de melodías cortadas. Estas últimas han correspondido a segmentos de publicidad, o bien a ajustes de continuidad de la programación que quiebra sus melodías para pasar al siguiente programa, siempre en espera de emisión y audiencia. Textura sonora. La muestra tiene textura de monodía acompañada en un 64,4% frente al canto a voces, tanto en su forma homofónica 4,4% como polifónica 12,9%. Plano sonoro. La música como protagonista ha tenido un amplio eco en el programa, apareciendo como fondo de escenas y dramatizaciones en el 25,6% de los casos de la muestra estudiada.

3.2. ¿Cómo es aquello que se escucha? Los contenidos musicales

Para estudiar cómo es la música del programa, se partió de la aplicación de la plantilla a 23 piezas musicales de las tres secciones, teniendo en cuenta la duración de la obra y su forma musical. Así, se estudiaron en las obras largas, la primera última frase, dos cortes intermedios y una valoración de la pieza musical completa durante los cinco días de la semana.

3.2.1. Programación propia

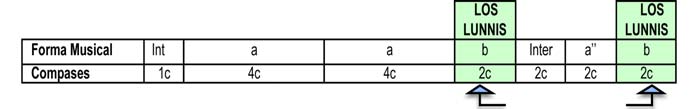

Los resultados obtenidos en la programación propia (cabecera, cierres, cortinillas y canciones), dibujos animados y publicidad han sido los siguientes: la cabecera del programa, repetida los 5 días de la semana, se ha estudiado por medio de 15 plantillas, 3 para cada día. Se trata de una pequeña melodía de 34’’, comienzo anacrúsico, tonalidad de Sol Mayor, a 144 negras por minuto, cantada por voces adultas solistas y grupos vocales con acompañamiento instrumental (figura 1). Esta melodía se escucha en enlaces, presentación de dramatizaciones, subsecciones, cortinillas y cierres, a las que se adapta con distintas versiones: instrumental, vocal, semi-hablada, completa, fraccionada o como bucle de repeticiones:

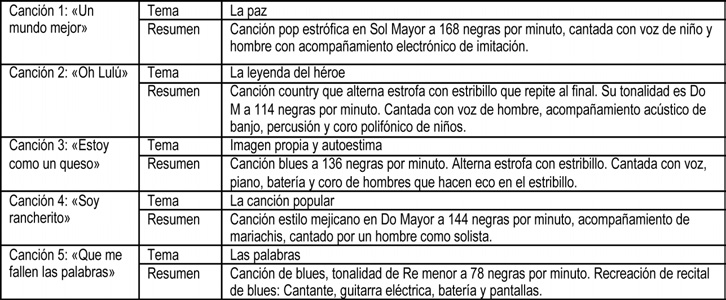

En los cierres, el programa utilizó diferentes partes de la melodía de la cabecera pero conservando el motivo de la sintonía. Su duración varía: 4’’, 36” y 1’33’’, este último cierre, por ejemplo, se repite en bucle mientras termina la última acción dramática del programa, y concluye con la sintonía que pasa de fondo a figura. En 2 de los 5 días se ofrece cortado y sustituido por el programa siguiente que ya se anuncia, o por la publicidad que no espera (González Requena, 1988). Las cortinillas, hasta un total de 8 tienen una duración de 7’’, toman los elementos de marca de la cabecera que modifican con diferentes instrumentaciones y efectos. En cuanto a las canciones y melodías, existen muchas en el programa. En este apartado hemos seleccionado las canciones protagonistas interpretadas por los personajes en diferentes escenarios como teatrillos, pubs, platós de televisión o decorados virtuales, que muestran las opciones televisivas formales, de género y estilo así como vinculación con la escena, selección de temáticas y sincronía entre texto e imagen. Se han estudiado las 5 canciones diegéticas de la semana (Tabla 1) por medio de 25 plantillas, 5 para cada una, correspondientes a la primera y última frase musical, 2 cortes intermedios y una valoración de la pieza completa:

3.2.2. Publicidad

Los anuncios se estudiaron con una sola plantilla, o dos cuando había un cambio musical destacado. Sus características comunes han sido: duración media de 20’’, tempo aproximado de 123 negras por minuto, instrumental, sonido electrónico de imitación, binario, sin variación en la dinámica ni en la agógica, género pop y cinematográfico, modo mayor y música como fondo que en ocasiones pasa a figura. En el caso de «I’m «pocket», se aplicaron dos plantillas por el cambio significativo: Corte 1:1’’ a 18’’. Corte 2: de 18’’ a 20’’ en el que se produce un cambio musical para destacar el eslogan.

3.2.3. Dibujos animados

Por último, el estudio de los dibujos animados, se realizó con un corte cada 45’’ hasta cubrir el episodio completo. Resumimos «Berni» y «Pocoyo»:

- «Berni» es una serie de dibujos animados de 2006, producida por «BRB Internacional S.A.», sin diálogos, sobre temática deportiva y protagonizada por «Berni», un oso polar. Se compone de episodios de 3’ enlazados hasta la duración total emitida. El estudio fue realizado por medio de 6 plantillas. En el episodio se observaron tanto ruidos y sonidos cotidianos como sonido musical electrónico de imitación. La música combinaba el estilo Clásico en breves secuencias, con otros cinematográficos de carácter incidental, modo mayor, instrumental, sin variación en la agógica ni en la dinámica, cadencias tanto conclusivas como suspensivas, modulaciones a otras tonalidades, textura sonora de monodía acompañada y música como fondo, excepto en una ocasión que realizó el recorrido, como progresión, de fondo a figura.

- «Pocoyo». Serie de dibujos animados españoles de 2005 de Zinkia Entertainment, el protagonista es «Pocoyó», un niño pequeño, en su aventura de descubrimiento y relación con el entorno. Duración 6’45’’. La acción narrativa del episodio era el hallazgo de las propias huellas y las de los otros. El episodio utilizó tanto el sonido no musical como el musical perteneciente al entorno del pop con pinceladas cinematográficas de corte incidental. La música era electrónica, instrumental, binaria y tética con variaciones en la dinámica y la agógica. La utilización del tempo estaba asociada al paso de los personajes en la escena: «Pocoyo» a 156 negras por minuto, «Elefante» a 90 y «Pato» a 114. Usó tanto el modo mayor como menor, diferentes cadencias, modulaciones, textura sonora de monodía acompañada, obstinatos rítmicos y efectos sonoros. La música tenía presencia como fondo y también como figura, los motivos musicales constituían el «leitmotiv» de los personajes.

4. Discusión

Como respuesta a los objetivos y preguntas de investigación podemos decir: ¿Qué se escucha? La banda sonora del programa «Los Lunnis» utiliza el sonido musical, preferentemente electrónico, con un reparto similar entre instrumental y vocal por grupos de voces. Su música es binaria, popular, anacrúsica, de dinámica plana, sin variaciones en la velocidad y textura de monodía acompañada. Utiliza el modo mayor con modulaciones a otras tonalidades, resolución por cadencia conclusiva y predominancia de la música como figura. Existe un porcentaje elevado de sonido no musical, formado por ruidos y efectos sonoros.

¿Cómo es la música? El análisis musical revela, en una primera valoración, que la programación propia, 25% del programa, está formada en su selección diegética, por canciones estróficas con frases de 8 compases que se escuchan completas y resuelven de forma altamente conclusiva con todos los elementos de cierre disponibles, utilizando en ocasiones polifonía tanto homofónica como polifónica. Se observa cierta pobreza rítmica, con una presencia alta del acento binario. La intensidad no tiene matices y es manejada por mesa de mezclas, que pasa de fondo a figura, normalmente, por estrategias narrativas no musicales. El programa muestra una buena sincronía entre música e imagen, los instrumentos y objetos sonoros son coherentes con su banda sonora y espacios escenográficos. Sus tempos oscilan entre 78 y 168 negras por minuto sin variaciones en la agógica, utiliza las tonalidades de Do M, Sol M, Re M y Re m que modulan a otras tonalidades en ocasiones. Desde el punto de vista estilístico y su vinculación con la identidad, el programa opta por músicas populares extranjeras, su tímbrica es predominantemente electrónica con elementos acústicos de la música popular de que se trata, estructuras armónicas y melódicas que la reflejan y acompañan muchas veces de movimientos coreográficos con una ambientación musical coherente en vestuario y escenografía. La publicidad, con una presencia del 12% del total, tiene una banda sonora con una velocidad media de 123 negras por minuto, predominantemente instrumental, con sonido electrónico de imitación, binaria, tética, sin variación en la dinámica ni en la agógica, sin estilo definido, uso en ocasiones del género cinematográfico, ruidos y sonidos no musicales, modo mayor y música como fondo. Los dibujos animados, 63% del programa, utilizan música, sonidos no musicales y ruidos sirviendo a la acción dramática, reforzándola, por medio de cambios de tonalidad y de tempo, así como efectos suspensivos y pequeños «leitmotiv» para definición de personajes. El estudio melódico indica que la melodía más escuchada es la sintonía, apareciendo como presentación y final de secciones, dramatizaciones y episodios. Se escuchan piezas musicales cortadas, especialmente en la publicidad y en los finales de episodios. De igual modo podemos señalar la presencia mayoritaria de música no diegética, y una gran variedad de sonidos musicales y no musicales, debido, principalmente, al peso en la programación de los dibujos animados.

Selección de géneros y estilos. La música anterior al siglo XX es escasa, con algunas excepciones en los dibujos animados y parodias de la programación propia en que aparecen algunos guiños al estilo Clásico. La opción estilística del programa es la popular, siendo las canciones protagonistas de la semana una ranchera, una canción country, dos blues y una canción pop. En la muestra estudiada, se escucha siempre la música de otros y nunca la propia. La programación infantil de televisión requiere contenidos de la proximidad (De Moragas, 1991), sin embargo lo que se ofrece es un espacio multicultural que ha perdido lo propio para llenarlo sólo con lo exótico. Desde una mirada educativa esta opción cuestiona la identidad porque la música habla de uno mismo, de los otros y con los otros (Porta, 2004: 112). Valorar la diversidad supone el reconocimiento de lo propio en edades tempranas, porque este habla egocéntrica (Vygotsky, 1981: 162) dará lugar en su recorrido, al habla interna, y la música está en el camino.

Música incidental. La música vinculada a la acción está presente, apareciendo en todas sus secciones, minúsculas músicas programáticas que recuerdan al niño el mundo del cine. Este es el caso de la parodia de «Lunicienta», al igual que la de «Psicosis», o las repetidas referencias a uno de los últimos héroes americanos: «Indiana Jones». En «Pocoyo», encontramos ««leitmotiv»» asociados a sus personajes, música tonal y no tonal, modulaciones, variaciones en la dinámica, agógica, paso de música de figura a fondo y viceversa. Todo ello en un diálogo espacio temporal, expresivo y estético que piensa en un niño pequeño e inteligente, que interactúa con el medio televisivo a través de la música.

La banda sonora del cine y la televisión tiene influencia educativa y responsabilidad social como una parte de la construcción de la conciencia del niño porque contribuye a su construcción cognitiva, social, expresiva, estética y en un futuro crítica. En este texto hemos mostrado algunos aspectos poco analizados en los estudios musicales de la televisión y su influencia en la infancia, pero que emergen cuando son estudiados desde la semiótica, la representación musical, el análisis formal y las teorías de la reestructuración. Las conclusiones indican como líneas de acción, dar valor a las funciones sociales, culturales y patrimoniales de la oferta musical televisiva, porque la música habla de los otros y con los otros. Y lo hace mediante la representación: qué se escucha; mediante la edición: cómo se produce, se articula y crea la continuidad de aquello que se ve y se escucha; y también desde la posición del que habla: la producción televisiva, su significado e influencia. El medio televisivo puede favorecer la reconstrucción de los contenidos musicales y su comprensión, el desarrollo del gusto y la puesta en valor del patrimonio inmaterial. Por todo ello se hace necesario en estudios futuros ampliar la definición de unidades de análisis, tal como se propone desde la psicología cognitiva y las corrientes musicales del siglo XX. Este estudio ha dado respuesta a algunas de ellas que hablan de patrimonio cultural, identidad y alteridad, lecturas de la diversidad y relaciones con el entorno, que tienen en la música mucho más que un soporte audiovisual, tienen en ella un vehículo, medio y contenido de expresión así como de representación y diálogo con el mundo.

Notas

1 Los indicadores, definiciones y revisión de los resultados fueron debatidos en el II Encuentro «La banda sonora de la televisión infantil y juvenil en el ámbito latinoamericano. Variables, impacto e influencia en el patrimonio sonoro», en Universidad Lanús (Buenos Aires) del 14 y 18 de Mayo de 2008. Participando tres universidades españolas (UV, UG, UJI) y cinco iberoamericanas (ULANUS, UT, UNIRIO; US, UNE).

Apoyos

Este trabajo ha sido subvencionado por los proyectos:1) I+D (2007/ 2010) «Las bandas sonoras de la televisión infantil 2007/08 en España. Canal 9. Televisión Valenciana y TVE (P1 1A2007-17); 2) Cooperación Interuniversitaria e Investigación Científica entre España e Iberoamérica «La música y la escucha de la TV infantil en el ámbito iberoamericano. Análisis cuantitativo de variables y estudio comparado» (A/018075/08).

Referencias

Aguaded, J.I. (2004). Música y Comunicación. Comunicar, 23; 9-22.

Atienza, R. (2007). Paisajes sonoros. Ambientes sonoros urbanos. Encuentro Iberoamericano sobre Paisajes Sonoros. Madrid: Auditorio Nacional.

Beckers, R. (1993). Walkman, Fernsehen, Lieblingsmusik: Merkmale musikalischer Frühsozialisation, Mu-sikpädagogische Forschung, 14; 11.

Bixler, B. (2000). Let's Make Music School Library Journal, 46; 11; 72.

Brown, A.R. (2008). Popular Music Cultures, Media and Youth Consumption: Towards an Integration of Structure, Culture and Agency. Sociology Compass, 2 (2); 388-408.

Burnard, P.; Dillon, S. & al. (2008). Inclusive Pedagogies in Music Education: A Comparative Study of Music Teachers' Perspectives from four Countries. International Journal of Music Education, 26(2); 109-126.

CAC, (2003). Libro Blanco: La educación en el entorno audiovisual. Consejo Audiovisual de Cataluña.

Cage, J. (1961). Silence. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Cohen, J. (2005). Global and Local Viewing Experiences in the Age of Multichannel Television: The Israeli Experience. Communication Theory, 15 (4); 437-455.

De Moragas, M. (1991). Teorías de la comunicación. Barcelona: Gustavo Gilli.

De Pablos, J. (1986). Cine y enseñanza. Madrid: CIDE (MEC).

Del Carmen, M. (2001). Heritage: The Survival of Cultural Traditions in a Changing World. International Journal of Music Education, 37 (1); 67-71.

Del Río, P. (1997). Creciendo con la televisión. Cultura y Educación, 5; 23-95.

Del Río, P.& Alvarez, A. & Del Río, M. (2004). Pigmalión. Informe sobre el impacto de la televisión en la infancia. Madrid: Fundación Infancia Aprendizaje.

Delalande, F. (2004). La enseñanza de la música en la era de las nuevas tecnologías. Comunicar, 23; 20-24.

Eco, U. & Cantarell, F. (1978). La estructura ausente: Introducción a la semiótica. Madrid: Lumen.

Ferres, J. (1994): Televisión y educación, Madrid: Paidós.

Gómez-Ariza, C. (2000). Determinants of Musical Representation. Cognitiva, 12, 1; 89-110.

Hauser, A. (1963). Historia social de la literatura y el arte. Madrid: Guadarrama.

Korac, N. (1988). Los medios de comunicación visual y el desarrollo cognoscitivo, Universidad de Belgrado.

Magdanz, T. (2001). Classical Music: Is anyone listening? A Listener-based Approach to the Soundtrack of Ber-trand Blier's Too Beautiful for You, Discourses in music, 3, 1.

Mcguire, K.M. (2001). The Use of Music on Barney & Friends: Implications for Music Therapy

Medrano, C. (2008). La dieta televisiva y los valores: un estudio realizado con adolescentes en la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 239; 65-84.

Ocaña, A. & Reyes, M.L. (2010). El imaginario sonoro de la población infantil andaluza: análisis musical de «La Banda». Comunicar, 35; 193-200.

Orozco, G. (1996). Miradas latinoamericanas a la televisión. México: Universidad Iberoamericana.

Ostbye, T.; Pomerleau, J. & al. (1993). Food and Nutrition in Canadian Prime-time Television Commercials. Canadian Journal of Public Health-Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique, 84(6); 370-374.

Peterson, J.L. & Newman, R. (2000). Helping to curb youth violence: The APA-MTV «warning signs» initiative. Professional Psychology-Research and Practice, 31(5); 509-514.

Pintado, J, (2005). Lo ideal y lo real en TV: calidad, formatos y representación. Comunicar, 25; 101-108.

Porta, A. & Ferrández, R. (2009). Elaboración de un instrumento para conocer las características de la banda sonora de la programación infantil de televisión. Relieve, 15, 2. (www.uv.es/relieve/v15n2/relie¬vev15n2_¬6.htm) (25-11-2009).

Porta, A. (2004). Musical Expression as an Exercise in Freedom, ISME 26. International Society for Music Edu-cation. World Conference. Tenerife.

Porta, A. (2005). La escucha de un espectador de fondo. El niño ante la televisión. Comunicar,

Porta, A. (2007). Músicas públicas, escuchas privadas. Hacia una lectura de la música popular contemporánea. Aldea Global. Barcelona: UAB.

Pozo, J.I. (1989). Teorías cognitivas del aprendizaje. Madrid: Morata.

Register, D. (2004). The Effects of Live Music Groups Versus an Educational Children's television program on the emergent literacy of young children. Journal of Music Therapy, 41(1); 2-27.

Reig, R. (2005). Televisión de calidad y autorregulación de los mensajes para niños y jóvenes.

Schaeffer, P. (1966). Traté des objets musicaux. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

Schafer, M. (1977). The Tuning of the World, Toronto: McClelland and Steward.

Shuck, L.; Salerno, K. & al. (2010). Music Interferes with Learning from Television during Infancy. Infant and Child Development, 19(3); 313-331.

Sloboda, J. (2005). Exploring the Musical Mind: Cognition, Emotion, Ability, Function. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press.

Stiegler, B. (1989). La lutherie électronique et la main du pianiste, Mots/Images/Sons, Cahiers du Cirem: Rouen.

Talens, J. (1994). Escritura como simulacro: El lugar de la literatura en la era electrónica. Valencia: Eutop-ías/Epiteme.

Vallejo Nágera, A. (1987). Mi hijo ya no juega, solo ve la televisión. Madrid: Temas de hoy.

Varios (1998). Monográfico Música moderna. Eufonía, 12; 7-98.

Vygotsky, L. (1981). The Instrumental Method in Psychology. In Wertsch, J. (Ed.). The Concept of Activity in Soviet Psychology. New York: Sharpe; 134-143.

Ward-Steinman, P.M. (2006). The Development of an After-school Music Program for at-risk Children: Student Musical Preferences and Pre-service Teacher Reflections. International Journal of Music Education, 24 (1); 85-96.

Zamacois, J. (1986). Curso de formas musicales. Barcelona: Labor.

Document information

Published on 30/09/11

Accepted on 30/09/11

Submitted on 30/09/11

Volume 19, Issue 2, 2011

DOI: 10.3916/C37-2011-03-10

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?