Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Collaborative learning has a strong presence in technology-supported education and, as a result, practices being developed in the form of Computer Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL) are more and more common. Planning seems to be one of the critical issues when elaborating CSCL proposals, which necessarily take into account technological resources, methodology and group configuration as a means to boost exchange and learning in the community. The purpose of this study is to analyze the relevance of the CSCL planning phase and weigh up the significance of its key design components as well as examining group agreement typology and its usefulness in team building and performance. To do so, research was carried out using a non-experimental quantitative methodology consisting of a questionnaire answered by 106 undergraduate students from 5 different CSCL-based subjects. Results prove the usefulness of the planning components and the drafting of group agreements and their influence on group building and interaction. In order to ensure the quality of learning, it is essential to plan CSCL initiatives properly and understand that organizational, pedagogical and technological decisions should converge around a single goal which is to sustain the cognitive and social aspects that configure individual and group learning.

1. Introduction

It is evident that human beings join communities in an attempt to reach certain goals or ideals. The relationships that make the group stay together are esta blished to a large extent by the interaction required to pursue common goals; in the case of learning communities, it is to achieve the learning objectives.

In a review of the literature we find considerable evidence that social interaction contributes to effective learning (Hiltz & al., 2001). Rodríguez-Illera (2001) points to several psychological and anthropological approaches covering this non-individualistic conception of learning: situated, shared or distributed cognition, social constructivism, activity theory or the sociocultural approach (Vygotski, 2000). Even so, it is necessary to differentiate between the traditional conception of group work and the ongoing collaborative work perspective, where the emphasis is on the idea of «built knowledge» (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 1994), which refers to the interaction and reflection process that allows the group to configure meanings together (Guitert, 2011; Harasim & al., 2000; Johnson & John son, 1999).

The advantages of collaborative work for learning at different stages, such as academic, psychological and social benefits, are broadly covered in many studies (Johnson, Johnson & Holubec, 1993; Roberts, 2005; Slavin, 1985). Collaborative work also improves transversal competences in team work (Guitert, 2011; Hernández-Sellés & Muñoz-Carril, 2012), and au thors note the twin effect of «collaborating to learn and learning to collaborate» (Rodríguez-Illera, 2001: 64).

Collaboration is perceived as one of the distinctive characteristics that are necessary for learning in virtual environments (Garrison, 2006; Harasim & al., 2000; Kirschner, 2002; Palloff & Pratt, 1999; Román, 2002). Dillenbourg (2003) even states that collaborative work is one of the dominant features in technology-supported education, hence the relevance of CSCL-based practical work.

However, initiatives for group work do not guarantee good collaborative work (Brush, 1998; Dillenbourg, 2002). Stahl, Koschmann and Suthers (2006) refer to the risk of assuming that students know how to work in groups and that they will collaborate spontaneously. Technology itself, no matter how so phisticated, is not enough since the tools themselves do not propose a model or promote a particular dynamic (Onrubia & Engel, 2012). Therefore, any proposal for online collaborative learning requires technological as well as pedagogical and social aspects to be taken into consideration.

That is why an efficient CSCL design needs careful planning as well as curricular and pedagogical implementation. Both aspects should take advantage of technologies and at the same time foster exchange and learning in the community (Guitert & al., 2003; Medi na & Suthers, 2008; Oakley & al., 2004; Rubia, 2010). Exley and Dennick (2007) state that preparation is essential in education. Guitert (2011) remarks on the need to plan asynchronous collaborative work since otherwise there is a risk of considerable time wasting that could damage the academic activity. Indeed, students whose collaborative work is planned and monitored appear to be more satisfied with their learning process (Felder & Brent, 2001). The review of some of the major studies regarding effective CSCL design and planning has enabled us to identify the following relevant aspects:

a) It is necessary to begin with an initial reflection on competences and objectives before deciding on methodology (Rubia, 2010). Therefore, there is a need to identify the CSCL contribution regarding generic, transversal and subject competences and to establish the relationship between method and objectives. On the other hand, a good system aligns both teaching and assessment methods with the learning activities included in the objectives, and so each element in the system supports student learning.

b) Methodology and task type need to be coherent. As for task type, Escofet & Marimon (2012) relate procedural, analytical and problem-solving tasks to collaborative learning, pointing out that learning is significant when it entails the resolution of a complex task that requires various actions and decisions. Gros & Adrián (2004) also relate collaborative work to problem resolution, project deveopment or discussion interactions, emphasizing the need to assign group roles and the tutor’s role as a guide who guarantees collaboration.

c) It is necessary to generate resources with information that will communicate the collaborative model to the students, together with its phases and pedagogical objectives. Recently, authors such as Dillenbourg and Hong (2008), Haake and Pfister (2010), Onrubia and Engel (2012) and Sobreira and Tchounikine (2012) have studied the idea of producing collaboration scripts that guide students to form groups, interact and collaborate in order to solve the task or problem. These scripts are also used as a means to establish a commitment between students and teacher, as well as to support task organization. On the other hand, Strijbos, Martens and Jochems (2004) suggest the need to systematize a model to communicate to students the type of interaction that is expected of them, and clarify the relation between task result and group interaction.

d) It is necessary to decide group characteristics and define the group-building process, taking into consideration the drafting of the group agreement. It seems that the group-building process is decisive in fostering collaborative work and guaranteeing learning (Dillenbourg, 2002; Exley & Dennick, 2007; Guitert, 2011; Guitert & al., 2003; Isotani & al., 2009; Pujolàs, 2008). It is also necessary to estimate grouping endurance since stability in the group enhances the maturation process(Barberá & Badía, 2004; Guitert & al., 2003; Exley & Dennick, 2007) as well as the development of team work competences, particularly if there is effective guidance from the teacher (Her nández-Sellés, 2012).

In the case of teacher-formed groups, Muehlenbrock (2006) points out that the perspective of grouping by characteristics is broadened in virtual environments due to the ubiquity of remote work. This is why it is necessary to take aspects such as location, time and availability into account. Webber & Webber (2012) determine that grouping through automatic mechanisms does not have a negative effect on collaborative work. In higher education, spontaneous grouping seems to imply greater commitment in task performance (Guitert & al., 2003).

Several authors point out that heterogeneous grouping seems to lead to a deeper learning as a consequence of the contrast of different points of view and diverse leels of comprehension (Barberá & Badía, 2004; Felder & Brent, 2001; Guitert & al., 2003; Exley & Dennick, 2007; Pujolàs, 2008). Both students with a higher comprehension level as well as those less gifted benefit from collaboration. Different perspec tives and points of view also support learning.

As far as group size, authors seem to agree on five members since more can limit some member’s contributions and less than five students might diminish in teraction variety.

Exley & Dennick (2007) refer to the relevance of manifesting the fundamental goals of collaborative work and emphasize establishing some basic rules and defining an attitudinal and rational framework for colla boration; they also refer to the need to explain and clarify task and schedule distribution. Indeed, these au thors relate malfunctioning groups to inconsistent initial planning. Guitert (2011) and Guitert & al. (2003) refer to the importance of drafting group agreements in order to support the group consolidation phase. These agreements are useful for grounding an exchange system and for setting frequency of contact to guarantee that the intragroup contrasts relevant to the task are given a hearing. Regarding this matter, Pujolàs (2008) cites the team notebook which includes the group and members’ names, their roles and functions, rules, group planning, session diary and regular team re views. This author considers that each group member should have an assigned role and recommends role spinning. Gros & Adrián (2004) emphasize the need to assign group roles and highlight teacher guidance as a means to guarantee collaborative activity. As already stated the literature on collaborative scripts insists on the establishment of bases for internal organization, including group-building criteria, work planning and contact modality in order to stabilize efficient group interaction.

2. Material and methods

This study analyzes university students’ assessments on the elements that support the organization and management of collaborative learning within a virtual environment. These are the specific objectives:

a) To assess the relevance of the planning phase within collaborative work in a virtual environment.

b) To estimate the scope of the key components of collaborative work design.

c) To analyze the relevance of some previous organizational aspects and their influence on collaborative work.

d) To identify the elements to be considered in the configuration of group agreements and assess their usefulness in group building and functioning.

And the following hypotheses have been formulated:

• Genre reveals significant differences regarding perception of collaborative work planning and the usefulness of group agreements.

• The degree course studied and the year in which students are enrolled reveal significant differences regarding perception of collaborative work planning and the usefulness of group agreements.

• Previous experience in face-to-face collaborative work reveals significant differences regarding perception of collaborative work planning and the usefulness of group agreements.

• Previous experience in virtual learning shows significant differences regarding perception of collaborative work planning and the usefulness of group agreements.

The research context entails a group of five subjects; two on the primary education Teaching degree course and three on the infant education Teaching degree course. They correspond to first-, second- and third-year courses and are taught in a blended modality at the CSEU La Salle (Madrid). The sample collected was of 106 questionnaires, representing 83.46% of the student population.

All of these subjects implemented the same collaborative work design in coordination. This design was grounded in planning which included: 1) a statement that communicated the task in a guide to collaboration that contained its description, a justification of the collaborative work, description of milestones, tools, a proposal for drafting a written group agreement and a description of the foundations for the collaborative work with a framework outlining attitudes and team work skills; 2) Spontaneous student group building; 3) group agreement writing; 4) teacher review and feedback on group agreements prior to group interaction.

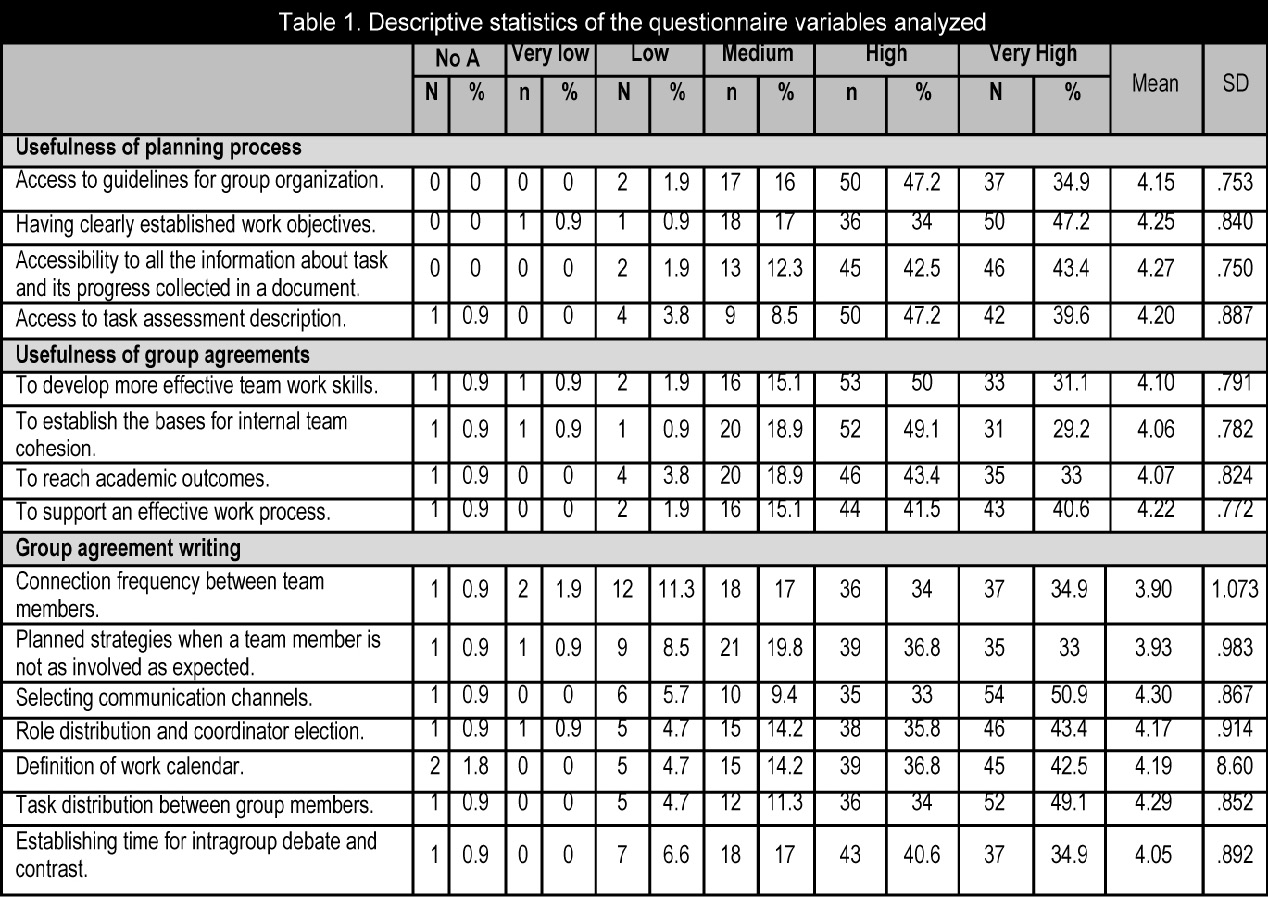

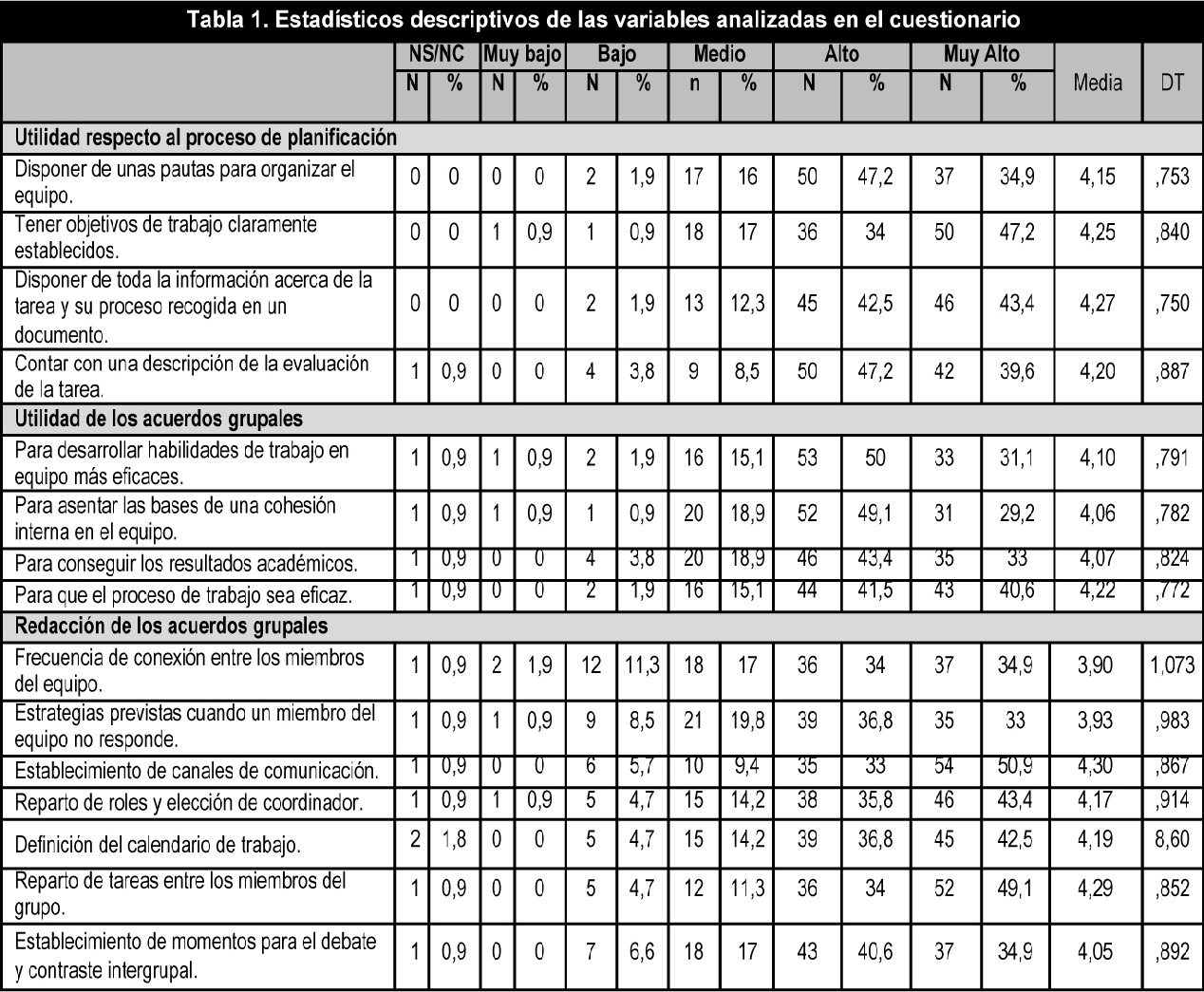

In order to pursue the exploratory and descriptive intentionality of the study, the methodology selected was non-experimental and quantitative, in the form of a survey (Buendía, Colás & Hernández, 1997; Cohen & Manion, 1990; McMillan & Schumacher, 2005). A Likert scale questionnaire was designed for the purpose of data collection with a five-answer level scale. The results appear in Section II under the titlen «Organi zation and management of team work prior to task performance». This section includes three categories that appear in Table 1: «Usefulness regarding the planning process» (including 4 items); Usefulness of group agreements» (4 items) and «Group agreement writing» (7 items). The questionnaire was answered in a face-to-face class just before the end of the course. A non-probabilistic, accidental or convenience sampling technique was used (Cohen & Manion, 1990; McMillan & Schumacher, 2005) to count the informants according to their availability or accessibility. Statistical analyses were undertaken with the SPSS 19 program.

In order to guarantee validity, the first version of the questionnaire went through a subject-matter expert content validation and was subjected to a pilot study. As for reliability, Cronbach’s alpha intern reliability index was used in all the three categories within the section. The coefficients obtained were a=0.859 for «Usefulness regarding the planning process», a=0.894 for «Usefulness of group agreements» and a=0.867 for «Group agreement writing».

3. Results

In order to address the research objectives and hypotheses, several statistical analyses were undertaken. Table 1 collects the descriptive analyses of the different items, including frequencies and percentages, as well as measurements of central tendency (mean) and dispersion (standard deviation). Non-parametric statistical tests were carried out later in order to contrast the significant differences between the variables analyzed.

As far as the descriptive analyses are concerned, it appears that students consider every aspect of collaborative work planning and group agreement writing to be very useful. Indeed, the means are all above 4 (in a 5-point scale), except for «Connection frequency between team members» (3.90 mean) and «Planned strategies when a team member is not as involved as expected» (3.93 mean). The item that presents greatest variability is: «Connection frequency between team members», with a 1.073 standard deviation.

For the contrast tests, taking into account that the variables considered are not normally distributed, non-parametric statistics were used: Mann-Whitney for two independent samples and Kruskal-Wallis for k independent samples.

There are significant differences according to gender (at an asymptotic level) between male and female students. The former consider the following variables to be more useful in the planning process: «Access to guidelines for group organization» (p-value=.005); «Having clearly established work objectives» (p-value=. 002); «Accessibility to all the information about task and its progress collected in a document» (p-value=.000).

On the other hand, there are significant differences regarding those elements considered to be particularly useful in writing the group agreement, since male students find some variables to be more useful than others, such as: «Planned strategies when a team member is not as involved as expected» (p-value= .024); «Selecting communication channels» (p-value= .001); «Role distribution and coordinator election» (p-value=.000); «Definition of work calendar» (p-value=.014) and «Task distribution between group members» (p-value=.047).

Focusing on the «degree» and «year» variables, there appear to be no significant differences except for the item: «Access to guidelines for group organization» (p-value=0.20). Students on the Infant Education degree course as well as those in the first year rated this item higher.

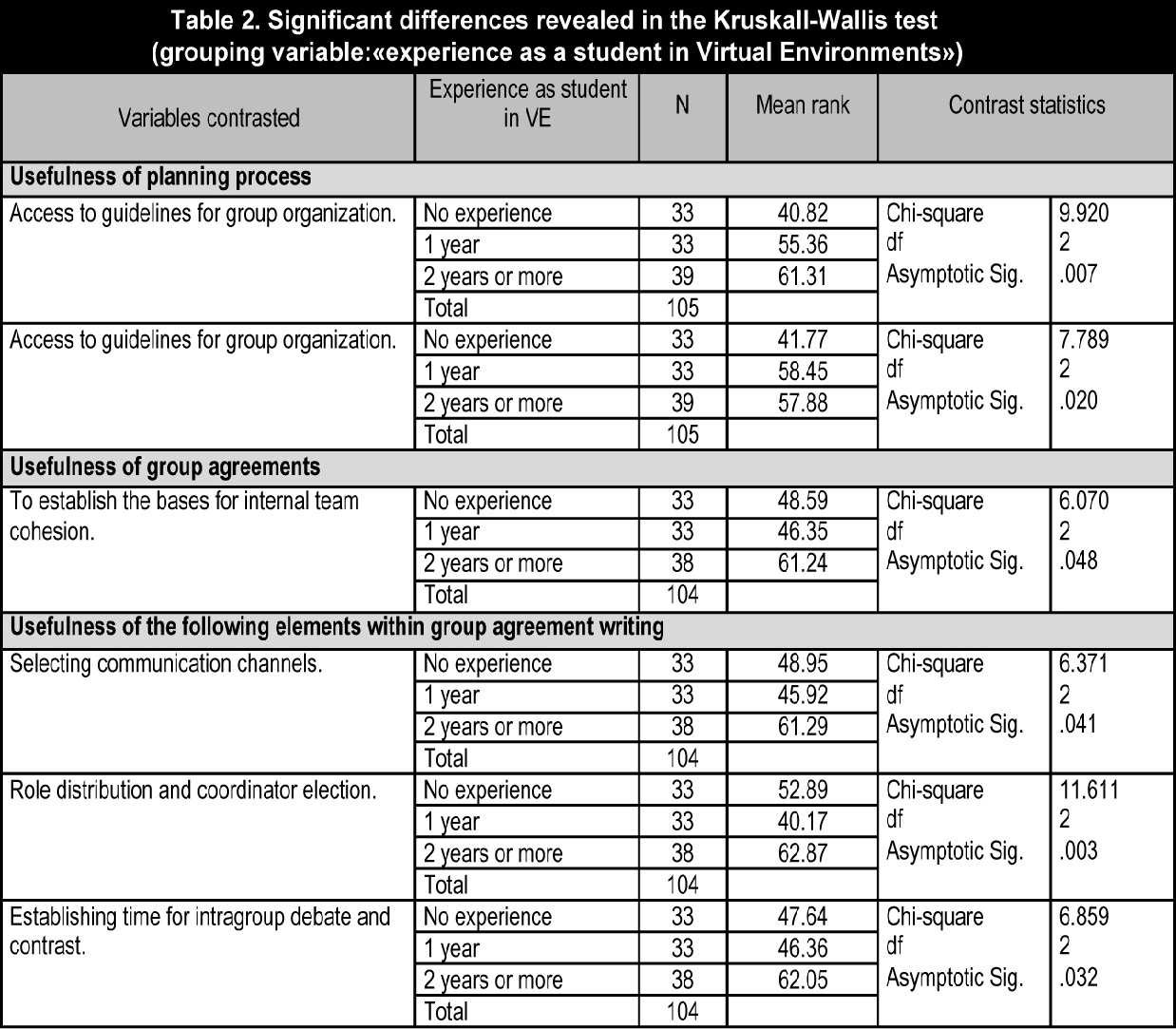

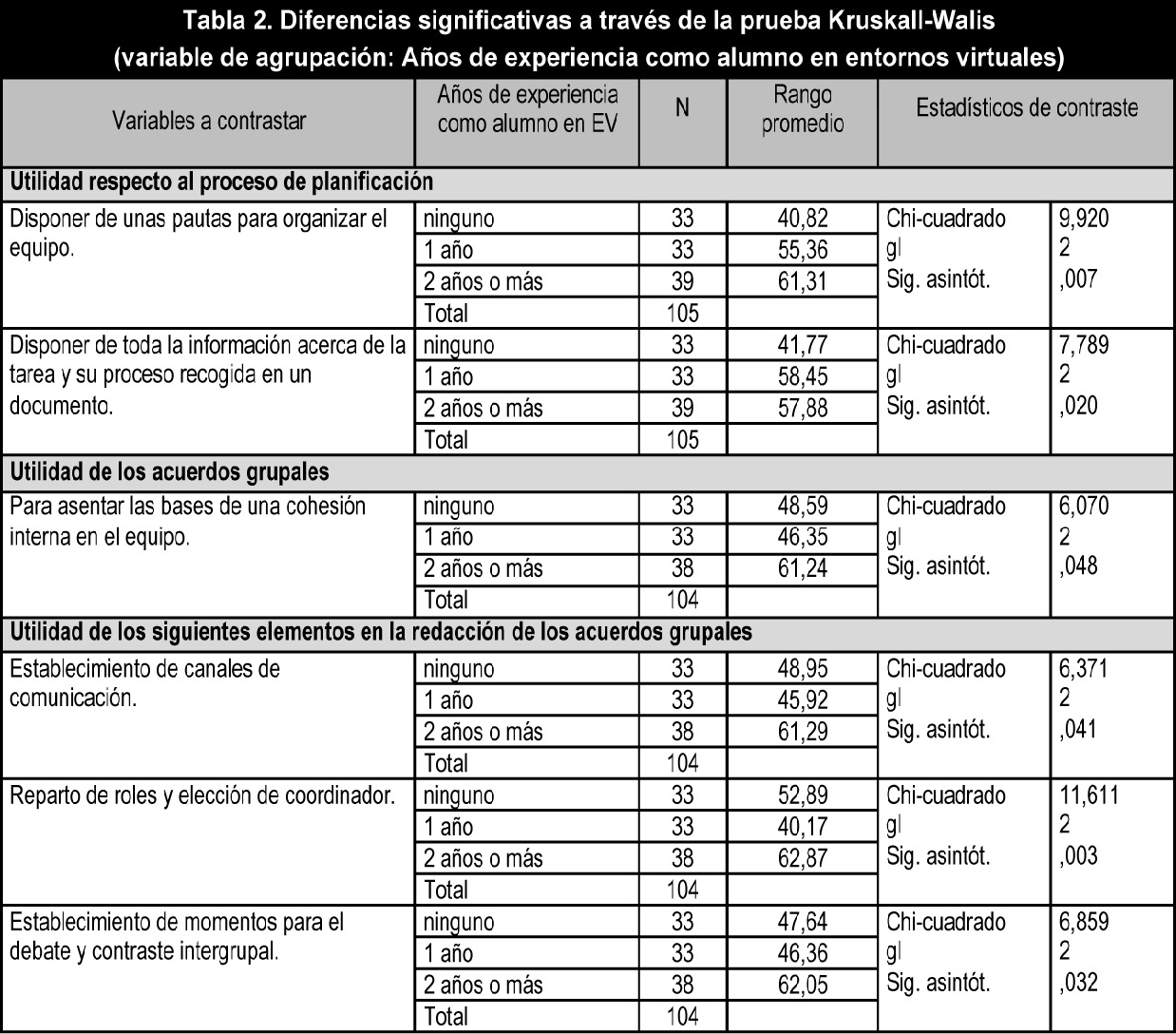

As for the experience as a student in virtual environments (online or blended), Table 2 shows how mean rankings are higher, in general, when students have experienced learning in virtual environments for two or more years. It is curious that these same students find the different elements related to planning collaborative work to be more useful.

It is also worth commenting that contrast statistics following the Mann-Whitney U reveal that those students with previous experiences in face-to-face collaborative work processes consider the planning process to be more useful than those who had never experienced collaborative work methodologies. As for «Useful ness of group agreements», the only variable where there have been significant differences is «To support an effective work process» (p<.005).

4. Discussion and conclusions

It is a very valuable exercise to collect the opinions of those students who have experienced a collaborative work methodology in a virtual environment, both to analyze the opportunities and challenges offered by CSCL as well as to see where future research can lead in terms of the weaknesses that emerge which have to be dealt with, and to identify those elements that need further exploration.

Considering the design of CSCL, the results show the usefulness of the diverse components of planning, and it is worth pointing out that those students who place more emphasis on the design phase were those who had previous experience in face-to-face collaborative work and a broader exprience of online learning. In this sense, the drafting of the group agreement is considered very useful. Another important aspect is that «Connection frequency between team members» and «Planned strategies when a team member is not as involved as expected» are considered less useful in the group agreement writing phase, maybe due to the fact that they refer to a personal commitment and imply a possible penalty. This may be awkward to include in the document that will form the basis of future group relationships. In any case, these are aspects worth exploring in detail in the future.

The answer of those students who had recently experienced collaborative learning confirm other au thor’s reflections –already cited– which claim that collaboration can lead to learning. This means the appropriate planning of collaborative work in such a way to build common bases within groups (grounding) for understanding, and to overcome obstacles such as low rates of participation and involvement (Kirschner, 2002).

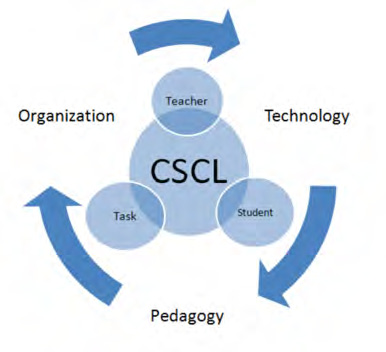

The collaboration-learning binomial cÇreates interesting opportunities –on a personal, group and social level–, but at the same time they have profound implications that entail a reconsideration of the pedagogical, organizational and technological elements configuring a virtual learning environment. These reflections should be made on an institutional level (Bates & Sangrà, 2011) as well as within subject design and curricular development. Online learning processes occur on two decision levels. On the one hand, they are linked to the curricular frame in which the topic is involved, and therefore relate to established organizational conditions as well as to pedagogical guidelines or a selected pedagogical model, and to the technology available in the institution. On the other hand, at the micro level in the classroom they are linked to the role of teacher and students and the specific activities promoted. The interrelations of all these factors inevitably condition the potential to teach and learn and, furthermore, that teaching and learning are possible through cooperation. Figure 1 aims to highlight the complexity of these interrelations.

As Sangrà (2010) states, the big investment in technologies made by higher education institutions should support innovation and promote improvement in learning by overcoming traditional models. One of the means to encourage innovation processes in higher education, connecting technology, pedagogy and organization, is by making the diverse possibilities of collaborative work in online education come true.

At a micro level, in every classroom situation, CSCL involves a change in the role that teachers and students have traditionally adopted. Teachers need to broaden their role as expert to incorporate others such as: planner, technologist and facilitator (Muñoz-Carril, González-Sanmamed & Hernández-Sellés, 2013). Students need to abandon their passive and receptive role so common in teacher-centered models, and take on a type of work that requires them to take responsibility for collaborating in unstructured tasks with multiple possible responses (Escofet & Marimon, 2012; Gros & Adrián, 2004). It is essential to design these tasks and particularly to elaborate detailed scripts including responsibilities, written documents on process and group agreements to support the group’s correct functioning and to guarantee the adequacy, effectiveness and sustainability of CSCL proposals. This will not only support academic learning but promote the social dimension and the sense of community. There fore, pedagogy, organization and technology also need to support the generation of an appropriate learning environment where it is possible to cultivate feelings of connection, to facilitate the so-called social presence and boost relations that humanize the virtual environment (Chapman, Ramondt & Smiley, 2005; Garrison, 2006; Picciano, 2002). Caring for the social aspects in collaborative learning and analyzing how it is possible for the two decision levels mentioned to support them constitute a key element in CSCL configuration and a challenge for research in the field (Pérez-Mateo & Guitert, 2012).

References

Barberà, E. & Badia, A. (2004). Educar con aulas virtuales. Madrid: Antonio Machado Libros.

Bates, A. & Sangrà, A. (2011). Managing Technology in Higher Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Brush, T. (1998). Embedding Cooperative Learning into the Design of Integrated Learning Systems: Rationale and Guidelines. Educational Technology Research and Development. 46 (3), 5-18.

Buendía, L., Colás, M. & Hernández, F. (1997). Métodos de investigación en Psicopedagogía. Madrid: McGraw-Hill.

Chapman, C., Ramondt, L. & Smiley, G. (2005). Strong Community, Deep learning: Exploring the Link. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 42 (3), 217-230. (DOI:10.1080/01587910500167910).

Cohen, L. & Manion, L. (1990). Métodos de investigación educativa. Madrid: La Muralla.

Dillenbourg, P. & Hong, F. (2008). The Mechanics of CSCL Macro Scripts. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 3(1), 5-23.

Dillenbourg, P. (2002). Over-scripting CSCL: The Risks of Blending Collaborative Learning with Instructional Design. In P.A. Kirschner (Ed.), Inaugural Address, three Worlds of CSCL. Can We Support CSCL? (pp. 61-91). Heerlen: Open Universiteit Nederland.

Dillenbourg, P. (2003). Preface. In J. Andriessen, M. Baker & D. Suthers, (Eds.), Arguing to Learn: Confronting Cognitions in Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning Environments (pp. 7-9). Kluwer: Dordrecht.

Escofet, A. & Marimon, M. (2012). Indicadores de análisis de procesos de aprendizaje colaborativo en entornos virtuales de formación universitaria. Enseñanza & Teaching, 30 (1), 85-114.

Exley, K. & Dennick, R. (2007). Enseñanza en pequeños grupos en educación superior. Tutorías, seminarios y otros agrupamientos. Madrid: Narcea.

Felder, R. & Brent, R. (2001). FAQs-3. Groupwork in Distance Learning. Chemical Engineering Education, 35 (2), 102-103.

Garrison, D.R. (2006). Online Collaboration Principles. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 10(1), 25-34.

Gros, B. & Adrián, M. (2004). Estudio sobre el uso de los foros virtuales para favorecer las actividades colaborativas en la enseñanza superior. Teoría de la Educación, 5. (http://campus.usal.es/~teoriaeducacion/rev_numero_05/n5_art_gros_adrian.htm) (02-04-2013).

Guitert, M. (2011). Time Management in Virtual Collaborative Learning: The Case of the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC). eLC Research Paper Series, 2, 5-16.

Guitert, M., Giménez, F. & al. (2003). El procés de treball i d’aprenentatge en equip en un entorn virtual a partir de l’anàlisi d’experiències de la UOC. (Document de projecte en línia. IN3, UOC. Treballs de doctorat, DP03-001). (www.uoc.edu/in3/dt/20299/20299.pdf) (02-04-2013).

Haake, J. & Pfister, H. (2010). Scripting a Distance-learning University Course: Do Students Benefit from Net-based Scripted Collaboration? International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 5 (2), 191-210.

Harasim, L., Hiltz, S., Turoff, M. & Teles, L. (2000). Redes de aprendizaje. Guía para la enseñanza y el aprendizaje en red. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Hernández-Sellés, N. & Muñoz-Carril, P.C. (2012). Trabajo colaborativo en entornos e-learning y desarrollo de competencias transversales de trabajo en equipo: Análisis del caso del Máster en gestión de Proyectos en Cooperación Internacional, CSEU La Salle. REDU, 10 (2). (http://red-u.net/redu/index.php/REDU/article/view/422) (05-04-2013).

Hernández-Sellés, N. (2012). Mediación del tutor en el diseño de trabajo colaborativo en Red: resultados de aprendizaje, vínculos en la comunidad virtual y desarrollo de competencias transversales de trabajo en equipo. Indivisa, 13, 171-190.

Hiltz, S., Coppola, N., Rotter, N., Turoff, M. & Benbunan-Fich, R. (2001). Measuring the Importance of Collaborative Learning for the Effectiveness of ALN: A Multi-measure, Multi-method Approach. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Network, 4, 103-125.

Isotani, S., Inaba, A., Ikeda, M. & Mizoguchi, R. (2009). An Ontology Engineering Approach to the Realization of Theory-driven Group Formation. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 4 (4), 445-478. (DOI:10.1007/s11412-009-9072-x).

Johnson, D. & Johnson, R. (1999). Aprender juntos y solos. Aprendizaje cooperativo, competitivo e individualista. Buenos Aires: Aique.

Johnson, D., Johnson, R. & Holubec, E. (1993). El aprendizaje cooperativo en el aula. Barcelona: Paidós.

Kirschner, P.A. (2002). Three Worlds of CSCL. Can We Support CSCL. Heerlen: Open University of the Netherlands.

Lebrun, M. (2004). Quality Towards an Expected Harmony: Pedagogy and Innovation Speaking Together about Technology. Networked Learning Conference. Université Catholique de Louvain. (www.networkedlearningconference.org.uk/past/nlc2004/proceedings/symposia/symposium5/lebrun.htm) (05-04-2013).

McMillan, J. & Schumacher, S. (2005). Investigación educativa. Madrid: Pearson Addison Wesley.

Medina, R. & Suthers, D. (2008). Bringing Representational Practice from Log to Light. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference for the Learning Sciences, 59-66.

Muehlenbrock, M. (2006). Learning Group Formation Based on Learner Profile and Context. International Journal on E-Learning, 5(1), 19-24.

Muñoz-Carril, P.C., González-Sanmamed, M. & Hernández-Sellés, N. (2013): Ped-agogical Roles and Competencies of University Teachers Practicing in the E-learning Environment. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 14(3), 462-487. (www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1477/2586) (12-04-2013).

Oakley, B. Felder, B., Brent, R. & Elhajj, I. (2004). Turning Student Groups into Effective Teams. J. Student Centered Learning, 2(1), 9-34.

Onrubia, J. & Engel, A. (2012). The Role of Teacher Assistance on the Effects of a Macro-script in Collaborative Writing Tasks. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 7(1), 161-186. (DOI:10.1007/s11412-011-9125-9).

Palloff, R. & Pratt, K. (1999). Building Learning Communities in Cyberspace: Effective Strategies for the Online Classroom. San Francisco: Joseey-Bass.

Pérez-Mateo, M. & Guitert, M. (2012). Which Social Elements are Visible in Virtual Groups? Addressing the Categorization of Social Expressions. Computers & Education, 58, 1.234-1.246. (DOI:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.12.014).

Picciano, A. (2002). Beyond Student Perceptions: Issues of Interaction, Presence, and Performance in an Online Course. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 6(1), 21-40.

Pujolàs, P. (2008). Nueve ideas clave. El aprendizaje cooperativo. Barcelona. Graó.

Roberts, T. (2005). Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning in Higher Education: An introduction. In T. S. Roberts (Ed.), Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning in Higher Education. (pp. 1-18). Hershey: Idean Group Publishing.

Rodríguez Illera, J.L. (2001). Aprendizaje colaborativo en entornos virtuales. Anuario de Psicología, 32(2), 63-75.

Román, P. (2002). El trabajo colaborativo mediante redes. In J.I. Aguaded & J. Cabero (Eds.), Educar en Red. Internet como recurso para la educación. (pp. 113-134). Málaga: Aljibe.

Rubia, B. (2010). La implicación de las nuevas tecnologías en el aprendizaje colaborativo. Tendencias Pedagógicas, 16, 89-106.

Sangrá, A. (2010) (Coord.). Competencias para la docencia en línea: evaluación de la oferta formativa para profesorado universitario en el marco del EEES. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Programa Estudios y Análisis (EA2010/0059). (http://138.4.83.162/mec/ayudas/CasaVer.asp?P=29~~443) (16-04-2013).

Scardamalia, M. & Bereiter, C. (1994). Computer Support for Knowledge-building Communities. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 3 (3), 265-283.

Slavin, R. (1985). Learning to Cooperate, Cooperating to Learn. Nueva York: Plenum Press.

Sobreira, P. & Tchounikine, P. (2012). A Model for Flexibly Editing CSCL Scripts. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 7(4), 567-592. (DOI:10.1007/s11412-012-9157-9).

Stahl, G., Koschmann, T. & Suthers, D. (2006). Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning: An historical Perspective. In R.K. Sawyer (Ed.), Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences. (pp. 409-426). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Strijbos, J., Martens, R. & Jochems, W. (2004). Designing for Interaction: Six Steps to Designing Computer-Supported Group-based Learning. Computers & Education, 42, 403-424. (DOI:10.1016/j.compedu.2003.10.004).

Vygotski, L. (2000). Historia del desarrollo de las funciones psíquicas superiores. Barcelona: Crítica.

Webber, C. & Webber, M. (2012). Evaluating Automatic Group Formation Mechanisms to Promote Collaborative Learning. A Case Study. International Journal of Learning Technology, 7(3), 261-276. (DOI:10.1504/IJLT.2012.049193).

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El trabajo colaborativo es una de las presencias dominantes en la formación apoyada en tecnologías, de ahí la importancia de las prácticas que se están desarrollando bajo las siglas CSCL (Computer Supported Collaborative Learning). Entre los aspectos que parecen ser determinantes para elaborar propuestas de CSCL se encuentra la planificación, que debe contemplar tanto los recursos tecnológicos como la metodología y la propia configuración de los grupos de trabajo con el fin de favorecer los intercambios y el aprendizaje en comunidad. El propósito de este estudio es analizar la importancia de la fase de planificación del CSCL, estimando el alcance de los componentes clave de su diseño, y examinando la tipología y utilidad de los acuerdos grupales en la creación y funcionamiento de los equipos. Para ello se llevó a cabo una investigación con una metodología cuantitativa de carácter no experimental de tipo encuesta en la que participaron 106 estudiantes de grado de cinco asignaturas que implementaron CSCL. Los resultados ponen de manifiesto la utilidad de los componentes de la planificación, así como la importancia de la redacción de acuerdos grupales y su incidencia en la creación y funcionamiento del grupo. Resulta esencial planificar adecuadamente el CSCL para garantizar el aprendizaje y entender que las decisiones organizativas, pedagógicas y tecnológicas deberían confluir en el objetivo de sustentar tanto los aspectos cognitivos como sociales que configuran el aprendizaje individual y grupal.

1. Introducción

Parece probado que los seres humanos nos agrupamos en comunidades para tratar de alcanzar ciertas metas o ideales. A través de la interacción que requiere el perseguir unos fines comunes, se establecen relaciones que, en gran medida, mantienen unida a la colectividad en torno a determinados propósitos: en el caso de las comunidades de aprendizaje, para el logro de los objetivos de aprendizaje.

Revisando la literatura encontramos numerosas evidencias de que la interacción social contribuye al aprendizaje eficaz (Hiltz & al., 2001). Tal y como reseña Rodríguez Illera (2001), son varios los enfoques psicológicos y antropológicos que dan cobertura a esta concepción no individualista del aprendizaje: la cognición situada, compartida o distribuida, el constructivismo social, la teoría de la actividad o el enfoque sociocultural (Vygotski, 2000). Conviene advertir, sin embargo, la diferencia entre la visión tradicional de trabajo en grupo frente a la perspectiva actual del trabajo colaborativo en el que se pone el énfasis en la idea de «conocimiento construido» (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 1994) como fruto de un proceso de interacción y reflexión que permite al grupo ir configurando significados de forma conjunta (Guitert, 2011; Harasim & al., 2000; Johnson & Johnson, 1999).

Las ventajas del trabajo colaborativo para el aprendizaje, tanto a nivel académico, psicológico como social, están ampliamente recogidas en multitud de estudios (Johnson, Johnson & Holubec, 1993; Roberts, 2005; Slavin, 1985). Sus beneficios repercuten también en la mejora de las competencias transversales del trabajo en equipo (Guitert, 2011; Hernández-Sellés & Muñoz-Carril, 2012), remarcando su doble efecto: «colaborar para aprender y aprender a colaborar» (Rodríguez-Illera, 2001:64).

La colaboración se contempla como una de las características distintivas y necesarias en el aprendizaje en entornos virtuales (Garrison, 2006; Harasim & al., 2000; Kirschner, 2002; Palloff & Pratt, 1999; Román, 2002). Dillenbourg (2003) incluso llega a afirmar que el trabajo colaborativo es una de las presencias dominantes en la formación apoyada en tecnologías y de ahí la importancia de las prácticas que se están desarrollando bajo las siglas CSCL (Computer Supported Collaborative Learning). En cualquier caso, la propuesta de actividades de carácter grupal no garantiza que se produzca un trabajo colaborativo (Brush, 1998; Dillenbourg, 2002). Stahl, Koschmann y Suthers (2006) se refieren al riesgo de asumir que los alumnos conocen por sí mismos el modo de trabajar en grupos y de dejarles colaborar de forma espontánea. La tecnología, por sofisticada que sea, tampoco es suficiente ya que, tal y como resaltan Onrubia y Engel (2012), las herramientas por sí solas no proponen ningún modelo ni potencian dinámicas determinadas. Por lo tanto, para elaborar una propuesta de enseñanza colaborativa en línea se requiere considerar aspectos tanto tecnológicos como pedagógicos y sociales.

Así pues, para garantizar un diseño eficaz en CSCL es necesario contar con una planificación cuidada y una implementación curricular y pedagógica que aproveche el uso de las tecnologías y favorezca los intercambios y el aprendizaje en comunidad (Guitert & al., 2003; Medina & Suthers, 2008; Oakley & al., 2004; Rubia, 2010). Tal y como indican Exley y Dennick (2007): «la enseñanza, la preparación lo es todo». Guitert (2011) señala la necesidad de planificar el trabajo colaborativo asíncrono, indicando que una mala planificación provocará una pérdida de tiempo para los alumnos y el detrimento de la actividad académica. De hecho, los estudiantes cuyo trabajo colaborativo es planificado y monitorizado se muestran más satisfechos con su proceso de aprendizaje (Felder & Brent, 2001).

La revisión de algunos de los estudios más relevantes en torno al diseño y planificación eficaz en CSCL, nos ha llevado a identificar la importancia de los siguientes aspectos:

a) Tomar como punto de partida la reflexión inicial en torno a competencias y objetivos para, a partir de ahí, afrontar las decisiones metodológicas (Rubia, 2010). De este modo se debe identificar qué se aporta en cuanto a competencias genéricas, transversales y propias de la asignatura y establecer una relación entre el método –en el marco del trabajo colaborativo– y los objetivos establecidos. Por otro lado, como indica Lebrun (2004), un buen sistema alinea el método de enseñanza y evaluación con las actividades de aprendizaje incluidas en los objetivos, de modo que todos los aspectos del sistema apoyen el aprendizaje de los alumnos.

b) Seleccionar con coherencia la metodología y tipo de tarea. En cuanto al tipo de tarea, Escofet y Marimon (2012) relacionan las de tipo procedimental, de análisis y resolución de problemas con el aprendizaje colaborativo, resaltando que éste es significativo cuando conlleva la resolución de una actividad compleja que requiere de diferentes acciones y decisiones. Gros y Adrián (2004) también concretan el trabajo colaborativo en la resolución de problemas, elaboración de proyectos o interacción en discusiones, incidiendo en la necesidad de asignar roles en el grupo y destacando el papel del tutor como guía que garantiza la actividad colaborativa.

c) Generar los recursos adecuados para comunicar a los alumnos el modelo de colaboración, sus fases de trabajo y sus objetivos pedagógicos. Recientemente, autores como Dillenbourg y Hong (2008), Haake y Pfister (2010), Onrubia y Engel (2012), y Sobreira y Tchounikine (2012) estudian la necesidad de generar guiones de colaboración que faciliten directrices a los alumnos acerca de la formación, interacción y colaboración del grupo en torno a la tarea o problema. Se utilizan también como un medio para establecer un compromiso entre los estudiantes y el profesor, además de apoyar el objetivo de organizar el trabajo. Por otro lado, Strijbos, Martens y Jochems (2004) proponen que se sistematice un modelo que comunique a los alumnos el tipo de interacción esperada, y que clarifique la relación entre el resultado de la tarea y la interacción grupal.

d) Decidir acerca de las características de los grupos de trabajo y definir el proceso de formación de los grupos, contemplando la redacción de unos acuerdos grupales. El proceso de formación de los grupos resulta decisivo para desarrollar el trabajo colaborativo y garantizar el aprendizaje (Dillenbourg, 2002; Exley & Dennick, 2007; Guitert, 2011; Guitert & al., 2003; Isotani & al., 2009; Pujolàs, 2008). Es necesario tener en cuenta la duración estimada de la agrupación: la estabilidad del grupo favorece un proceso de maduración (Barberá & Badía, 2004; Guitert & al., 2003; Exley & Dennick, 2007) y el desarrollo de competencias de trabajo en equipo, sobre todo, si hay un acompañamiento efectivo del profesor (Hernández-Sellés, 2012).

En el caso de grupos formados por el profesor, Muehlenbrock (2006) señala que la perspectiva de agrupación por características de los alumnos se amplía en los entornos virtuales, dada la ubicuidad del trabajo en remoto, y por ello es necesario tener en cuenta aspectos como la localización, el tiempo y la disponibilidad. Webber y Webber (2012) concluyeron que los agrupamientos a través de mecanismos automáticos no inciden negativamente en la efectividad del trabajo colaborativo. En el ámbito de la educación superior la formación espontánea parece conducir a un mayor grado de compromiso en torno a la tarea (Guitert & al., 2003).

Diversos autores coinciden en señalar que los grupos heterogéneos parecen conducir a un aprendizaje mayor debido al contraste de puntos de vista y grados de comprensión derivados de la diversidad (Barberá & Badía, 2004; Felder & Brent, 2001; Guitert & al., 2003; Exley & Dennick, 2007; Pujolàs, 2008). Tanto los que poseen un mayor grado de comprensión como los menos dotados se benefician de la colaboración. Los puntos de vista y experiencias distintas también apoyan al aprendizaje.

En cuanto al tamaño del grupo, los autores parecen coincidir en un número en torno a cinco. Un número mayor puede limitar las aportaciones de algunos miembros y un número más reducido disminuye la variedad de las interacciones.

Exley y Dennick (2007) señalan la importancia de manifestar los objetivos fundamentales del trabajo colaborativo e inciden en establecer unas reglas básicas y definir un marco actitudinal y racional para todo el trabajo del grupo, así como la necesidad de que la distribución de tareas y fechas se haga explícita y sea clara. De hecho, estos autores relacionan los equipos disfuncionales con una mala organización inicial. Guitert (2011) y Guitert y otros (2003) señalan que para que se produzca la fase de consolidación del grupo se deben redactar unos acuerdos grupales que ayuden a establecer un sistema de intercambio y una frecuencia de contacto que garantice el contraste intergrupal en torno a la tarea. Pujolàs (2008) se refiere en este sentido al cuaderno de equipo en el que se registrarán el nombre del grupo, miembros, cargos y funciones, normas de funcionamiento, planes del equipo, diario de sesiones y revisiones periódicas del equipo. Este autor considera positivo que cada miembro del equipo ejerza un cargo y que éstos sean rotativos. Gros y Adrián (2004) inciden en la necesidad de asignar roles en el grupo y destacan el papel del tutor como guía que garantiza la actividad colaborativa. Como ya apuntábamos anteriormente, en la literatura en torno a los guiones de colaboración se insiste en la conveniencia de establecer unas bases de organización interna, incluyendo los criterios de composición del grupo, la planificación del trabajo y el modo de contacto, para asentar las bases de la interacción eficaz del grupo.

2. Material y métodos

En este estudio se recogen las valoraciones de un grupo de alumnos universitarios, con experiencia en el desarrollo del trabajo colaborativo en un entorno virtual, acerca de los elementos que sustentan la organización y gestión del aprendizaje colaborativo. Concretamente, se han planteado los siguientes objetivos:

a) Valorar la importancia de la fase de planificación del trabajo colaborativo en un entorno virtual.

b) Estimar el alcance de los componentes clave del diseño del trabajo colaborativo.

c) Analizar el valor de algunos de los aspectos organizativos previos y su incidencia en el desarrollo del trabajo colaborativo.

d) Identificar los elementos a tener en cuenta en la configuración de los acuerdos grupales y examinar su utilidad en la creación y funcionamiento de los equipos de trabajo colaborativo.

Específicamente, se han formulado las siguientes hipótesis de investigación:

• El género suscita diferencias significativas en la valoración de la planificación del trabajo colaborativo y en la utilidad de los acuerdos grupales.

• La titulación y el curso en el que están matriculados los estudiantes genera diferencias significativas en la valoración de la planificación del trabajo colaborativo y en la utilidad de los acuerdos grupales.

• La experiencia previa de trabajo colaborativo presencial genera diferencias significativas en la valoración de la planificación del trabajo colaborativo y en la utilidad de los acuerdos grupales.

• La experiencia previa en la formación en entornos virtuales genera diferencias significativas en la valoración de la planificación del trabajo colaborativo y en la utilidad de los acuerdos grupales.

El escenario en el que se desarrolla la investigación comporta un grupo de cinco asignaturas de primer, segundo y tercer curso (dos de ellas pertenecientes al Grado de Maestro en Educación Primaria y tres al Grado de Infantil), cursadas en el CSEU La Salle (Madrid) e impartidas en modalidad semipresencial. La muestra recogida fue de 106 cuestionarios, que representan el 83,46% de la población.

Todas estas asignaturas implementaron coordinadamente un diseño de trabajo colaborativo sustentado en una planificación que implicaba: 1) Comunicar la tarea desde una guía de colaboración que incluía su descripción, justificación del trabajo colaborativo, principales hitos, descripción de herramientas, propuesta de redacción de acuerdos grupales y descripción de los cimientos del trabajo colaborativo, incluyendo un marco de actitudes y habilidades de trabajo en equipo; 2) Formación espontánea de grupos por parte de los alumnos; 3) Redacción de acuerdos grupales; 4) Revisión de los acuerdos y respuesta del docente, previa al inicio de la interacción.

Para dar respuesta a la intencionalidad exploratoria y descriptiva de este estudio, se ha utilizado una metodología cuantitativa de carácter no experimental de tipo encuesta (Buendía, Colás & Hernández, 1997; Cohen & Manion, 1990; McMillan & Schumacher, 2005). Para la recogida de datos se elaboró un cuestionario con una escala tipo Likert con cinco niveles de respuesta. En este artículo presentaremos los resultados alcanzados en el Bloque II, referido a la «Organización y gestión del trabajo en equipo previo al desarrollo de la tarea». Este bloque comprendía tres apartados, los cuales se reflejan en la tabla 1, a saber: «Utilidad respecto al proceso de planificación» (compuesto por cuatro ítems); «Utilidad de los acuerdos grupales» (formado por 4 ítems) y «Redacción de los acuerdos grupales» (estructurado en siete ítems). Dicho cuestionario se aplicó en una sesión presencial el penúltimo día de curso. Se utilizó un muestreo no probabilístico denominado «muestreo por conveniencia» (Cohen & Manion, 1990; McMillan & Schumacher, 2005), consistente en recurrir a los informantes en base a su disponibilidad o facilidad de acceso. Los análisis estadísticos se realizaron con el programa SPSS 19.

Para asegurar las condiciones de validez, la primera versión del cuestionario fue sometida a juicio de expertos y a un estudio piloto. En cuanto a la fiabilidad, se ha procedido al análisis del Alpha de Cronbach para cada uno de los tres apartados del bloque II, obteniéndose un a = 0,859 para el apartado de planificación; un a = 0,894 en la utilidad de los acuerdos grupales y un a = 0,867 para el último apartado sobre la utilidad de los aspectos a incluir en los acuerdos grupales.

3. Resultados

Para abordar los objetivos e hipótesis planteados en la investigación se procedió a la realización de diversos análisis estadísticos. Por una parte, en la tabla 1, se recogen los análisis descriptivos de los diferentes ítems analizados, incluyendo las frecuencias y porcentajes obtenidos, así como medidas de tendencia central (media) y de dispersión (desviación típica). Posteriormente, se han realizado pruebas estadísticas no paramétricas para el contraste de medias a fin de identificar diferencias significativas entre las variables analizadas.

En lo que respecta a los análisis descriptivos, se puede observar que el alumnado considera de gran utilidad todos aquellos elementos referidos a la planificación del trabajo colaborativo y, concretamente, la elaboración de acuerdos grupales. De hecho, las medias obtenidas son superiores en todos los casos a 4 puntos (sobre 5), a excepción de «frecuencia de conexión de los miembros del equipo» (media de 3,90) y «estrategias previstas cuando un miembro del equipo no responde» (media de 3,93). Cabe indicar, además, que el ítem que muestra mayor variabilidad de respuesta es: «frecuencia de conexión entre los miembros del equipo», con una desviación típica de 1,073.

Para las pruebas de contraste, teniendo en cuenta la ausencia de distribución normal de las variables consideradas, se utilizaron estadísticos no paramétricos: Mann-Whitney para dos muestras independientes y Kruskal-Wallis para k muestras independientes.

Según el género, se han hallado diferencias significativas (a nivel asintótico) entre los alumnos y las alumnas, siendo los primeros los que otorgan mayor utilidad, dentro del proceso de planificación, a las siguientes variables: «disponer de unas pautas para organizar el equipo» (p-valor=.005); «tener objetivos de trabajo claramente establecidos» (p-valor=.002); «disponer de toda la información acerca de la tarea y su proceso recogida en un documento» (p-valor=.000).

Por otra parte, en lo que respecta a aquellos elementos que son especialmente útiles en la redacción de los acuerdos grupales, se han encontrado diferencias que indican que son los alumnos los que confieren mayor utilidad a variables como: «estrategias previstas cuando un miembro del equipo no responde» (p-valor=.024); «establecimiento de canales de comunicación» (p-valor=.001); «reparto de roles y elección del coordinador» (p-valor=.000); «definición del calendario de trabajo» (p-valor=.014) y «reparto de tareas entre los miembros del grupo» (p-valor=.047).

Centrándonos en las variables «titulación» y «curso», hay que señalar que no se han encontrado diferencias significativas a excepción del ítem «disponer de unas pautas para organizar el equipo» (p-valor=0.20), siendo los alumnos del Grado de Infantil y los de primer curso los que en mayor medida valoran este aspecto.

Respecto a los años de experiencia como alumno/a en entornos virtuales (online o semipresenciales), se puede observar en la tabla 2, cómo los rangos promedio, en general, son mayores en aquellos alumnos que afirman tener dos o más años de experiencia desarrollando actividades de aprendizaje bajo entornos virtuales. Curiosamente, estos alumnos son los que otorgan mayor grado de utilidad a los diversos elementos de la planificación del trabajo colaborativo.

Otro aspecto que merece la pena ser comentado es que los estadísticos de contraste resultantes tras la aplicación de la prueba U de Mann-Whitney revelan que aquellos alumnos que sí han tenido experiencias previas desarrollando procesos de trabajo colaborativo en el ámbito presencial, manifiestan mayores niveles de utilidad respecto al proceso de planificación que aquellos otros estudiantes que nunca habían desarrollado metodologías de trabajo colaborativo. En lo que se refiere a la «utilidad de los acuerdos grupales», tan sólo se han identificado diferencias significativas en la variable «para que el proceso de trabajo sea eficaz» (p<.005).

4. Discusión y conclusiones

Recoger las voces de los estudiantes que han seguido una metodología de trabajo colaborativo en un entorno virtual resulta muy valioso, tanto para analizar las potencialidades y dificultades de los CSCL como para vislumbrar futuras líneas de investigación en torno a los aspectos que emergen como debilidades que hay que remediar o elementos aún poco conocidos que se deben explorar.

En cuanto al desarrollo de los CSCL, los resultados ponen de manifiesto la utilidad de los diversos componentes de la planificación. Sobre todo, cabe destacar, que han sido los alumnos con experiencia previa de trabajo colaborativo en el ámbito presencial y los que tienen una trayectoria de formación online los que más valoran la fase de diseño. Y, en este sentido, se considera de gran utilidad la redacción de acuerdos grupales. Llama la atención que «Frecuencia de conexión entre los miembros del equipo» y «Estrategias previstas cuando un miembro del equipo no responde» sean considerados los aspectos menos útiles a incluir en la redacción de dichos acuerdos grupales, quizás porque aluden a un compromiso más personal y llevarían implícito un cierto trasfondo sancionador que resultaría incómodo de plasmar en un documento de intenciones que será tomado como hoja de ruta en un momento de inicio de la relación grupal. En cualquier caso, éstos serían aspectos a indagar en mayor detalle.

Las respuestas de los estudiantes que han vivido una experiencia reciente de aprendizaje colaborativo confirman las reflexiones vertidas por otros autores -ya citados anteriormente- que postulan que la colaboración puede conducir al aprendizaje, pero para ello es necesario planificar adecuadamente el trabajo colaborativo de forma que en el marco del grupo se constituya una base común (grounding) para el entendimiento y se puedan superar diversos obstáculos como los bajos índices de participación e implicación (Kirschner, 2002).

El binomio colaboración-aprendizaje, al tiempo que puede suscitar interesantes oportunidades –a nivel personal, grupal y social–, también genera repercusiones profundas que reclaman una reconsideración de los elementos pedagógicos, organizativos y tecnológicos que configuran un entorno virtual de aprendizaje tanto a nivel institucional (Bates & Sangrà, 2011) como en el ámbito del diseño y desarrollo curricular de una materia. Los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje en línea acontecen en la confluencia de dos niveles decisionales. Por un lado, son deudores del marco curricular en el que se inserta la materia y, por tanto, de las condiciones organizativas establecidas, de las líneas pedagógicas o del modelo educativo elegido, y de la tecnología disponible en una determinada institución. Pero también, a nivel micro de cada aula, de los roles que va a desarrollar tanto el docente como los discentes y de las actividades específicas que se proponen. Las interrelaciones entre todos estos factores condicionan irremediablemente las posibilidades de enseñar y aprender y, más aún, de que esto sea posible a través de la colaboración. En el gráfico 1, se intenta plasmar la complejidad de estas interrelaciones.

Como evidencia Sangrà (2010), la fuerte inversión en tecnología que están realizando las instituciones de educación superior debería servir para apoyar la innovación y propiciar la mejora de los aprendizajes superando los modelos transmisivos tradicionales. Una de las formas de impulsar los procesos de innovación en la educación superior vinculando la tecnología, la pedagogía y la organización es haciendo posible las diversas opciones de trabajo colaborativo que permiten la formación en línea.

A nivel micro, en cada situación de aula, el CSCL implica un cambio en los roles que tradicionalmente han adoptado el profesorado y el alumnado. El docente necesariamente debe ampliar su papel de experto para incorporar funciones como: planificador, tecnólogo y facilitador (Muñoz-Carril, González-Sanmamed & Hernández-Sellés, 2013). Los alumnos tienen que abandonar el rol más pasivo y receptivo que impera en los modelos centrados en el profesor, y hacer frente a un trabajo cuya responsabilidad recae fundamentalmente en sus habilidades para colaborar con un grupo en tareas no muy estructuradas y con múltiples respuestas posibles (Escofet & Marimon, 2012; Gros & Adrián, 2004). El diseño de dichas tareas y, en particular, la elaboración de guiones detallados de las responsabilidades y el proceso a seguir, junto a la redacción de acuerdos consensuados, resultan claves para el buen funcionamiento del equipo, y para garantizar la adecuación, efectividad y sustentabilidad de las propuestas de CSCL, no sólo para generar aprendizajes académicos valiosos sino también en la línea de favorecer la dimensión social y el sentimiento de comunidad. De esta forma, la pedagogía, la organización y la tecnología, también deben ayudar a crear un clima apropiado de trabajo en el que se desarrollen sentimientos de conexión, se facilite la denominada presencia social y se favorezca la construcción de relaciones que humanicen el entorno virtual (Chapman, Ramondt & Smiley, 2005; Garrison, 2006; Picciano, 2002). Atender a los aspectos sociales del aprendizaje colaborativo y analizar cómo pueden sustentarse desde los dos niveles decisionales apuntados anteriormente constituye un elemento clave en configuración del CSCL y un desafío para la investigación en este ámbito (Pérez-Mateo & Guitert, 2012).

Referencias

Barberà, E. & Badia, A. (2004). Educar con aulas virtuales. Madrid: Antonio Machado Libros.

Bates, A. & Sangrà, A. (2011). Managing Technology in Higher Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Brush, T. (1998). Embedding Cooperative Learning into the Design of Integrated Learning Systems: Rationale and Guidelines. Educational Technology Research and Development. 46 (3), 5-18.

Buendía, L., Colás, M. & Hernández, F. (1997). Métodos de investigación en Psicopedagogía. Madrid: McGraw-Hill.

Chapman, C., Ramondt, L. & Smiley, G. (2005). Strong Community, Deep learning: Exploring the Link. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 42 (3), 217-230. (DOI:10.1080/01587910500167910).

Cohen, L. & Manion, L. (1990). Métodos de investigación educativa. Madrid: La Muralla.

Dillenbourg, P. & Hong, F. (2008). The Mechanics of CSCL Macro Scripts. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 3(1), 5-23.

Dillenbourg, P. (2002). Over-scripting CSCL: The Risks of Blending Collaborative Learning with Instructional Design. In P.A. Kirschner (Ed.), Inaugural Address, three Worlds of CSCL. Can We Support CSCL? (pp. 61-91). Heerlen: Open Universiteit Nederland.

Dillenbourg, P. (2003). Preface. In J. Andriessen, M. Baker & D. Suthers, (Eds.), Arguing to Learn: Confronting Cognitions in Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning Environments (pp. 7-9). Kluwer: Dordrecht.

Escofet, A. & Marimon, M. (2012). Indicadores de análisis de procesos de aprendizaje colaborativo en entornos virtuales de formación universitaria. Enseñanza & Teaching, 30 (1), 85-114.

Exley, K. & Dennick, R. (2007). Enseñanza en pequeños grupos en educación superior. Tutorías, seminarios y otros agrupamientos. Madrid: Narcea.

Felder, R. & Brent, R. (2001). FAQs-3. Groupwork in Distance Learning. Chemical Engineering Education, 35 (2), 102-103.

Garrison, D.R. (2006). Online Collaboration Principles. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 10(1), 25-34.

Gros, B. & Adrián, M. (2004). Estudio sobre el uso de los foros virtuales para favorecer las actividades colaborativas en la enseñanza superior. Teoría de la Educación, 5. (http://campus.usal.es/~teoriaeducacion/rev_numero_05/n5_art_gros_adrian.htm) (02-04-2013).

Guitert, M. (2011). Time Management in Virtual Collaborative Learning: The Case of the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC). eLC Research Paper Series, 2, 5-16.

Guitert, M., Giménez, F. & al. (2003). El procés de treball i d’aprenentatge en equip en un entorn virtual a partir de l’anàlisi d’experiències de la UOC. (Document de projecte en línia. IN3, UOC. Treballs de doctorat, DP03-001). (www.uoc.edu/in3/dt/20299/20299.pdf) (02-04-2013).

Haake, J. & Pfister, H. (2010). Scripting a Distance-learning University Course: Do Students Benefit from Net-based Scripted Collaboration? International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 5 (2), 191-210.

Harasim, L., Hiltz, S., Turoff, M. & Teles, L. (2000). Redes de aprendizaje. Guía para la enseñanza y el aprendizaje en red. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Hernández-Sellés, N. & Muñoz-Carril, P.C. (2012). Trabajo colaborativo en entornos e-learning y desarrollo de competencias transversales de trabajo en equipo: Análisis del caso del Máster en gestión de Proyectos en Cooperación Internacional, CSEU La Salle. REDU, 10 (2). (http://red-u.net/redu/index.php/REDU/article/view/422) (05-04-2013).

Hernández-Sellés, N. (2012). Mediación del tutor en el diseño de trabajo colaborativo en Red: resultados de aprendizaje, vínculos en la comunidad virtual y desarrollo de competencias transversales de trabajo en equipo. Indivisa, 13, 171-190.

Hiltz, S., Coppola, N., Rotter, N., Turoff, M. & Benbunan-Fich, R. (2001). Measuring the Importance of Collaborative Learning for the Effectiveness of ALN: A Multi-measure, Multi-method Approach. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Network, 4, 103-125.

Isotani, S., Inaba, A., Ikeda, M. & Mizoguchi, R. (2009). An Ontology Engineering Approach to the Realization of Theory-driven Group Formation. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 4 (4), 445-478. (DOI:10.1007/s11412-009-9072-x).

Johnson, D. & Johnson, R. (1999). Aprender juntos y solos. Aprendizaje cooperativo, competitivo e individualista. Buenos Aires: Aique.

Johnson, D., Johnson, R. & Holubec, E. (1993). El aprendizaje cooperativo en el aula. Barcelona: Paidós.

Kirschner, P.A. (2002). Three Worlds of CSCL. Can We Support CSCL. Heerlen: Open University of the Netherlands.

Lebrun, M. (2004). Quality Towards an Expected Harmony: Pedagogy and Innovation Speaking Together about Technology. Networked Learning Conference. Université Catholique de Louvain. (www.networkedlearningconference.org.uk/past/nlc2004/proceedings/symposia/symposium5/lebrun.htm) (05-04-2013).

McMillan, J. & Schumacher, S. (2005). Investigación educativa. Madrid: Pearson Addison Wesley.

Medina, R. & Suthers, D. (2008). Bringing Representational Practice from Log to Light. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference for the Learning Sciences, 59-66.

Muehlenbrock, M. (2006). Learning Group Formation Based on Learner Profile and Context. International Journal on E-Learning, 5(1), 19-24.

Muñoz-Carril, P.C., González-Sanmamed, M. & Hernández-Sellés, N. (2013): Ped-agogical Roles and Competencies of University Teachers Practicing in the E-learning Environment. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 14(3), 462-487. (www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1477/2586) (12-04-2013).

Oakley, B. Felder, B., Brent, R. & Elhajj, I. (2004). Turning Student Groups into Effective Teams. J. Student Centered Learning, 2(1), 9-34.

Onrubia, J. & Engel, A. (2012). The Role of Teacher Assistance on the Effects of a Macro-script in Collaborative Writing Tasks. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 7(1), 161-186. (DOI:10.1007/s11412-011-9125-9).

Palloff, R. & Pratt, K. (1999). Building Learning Communities in Cyberspace: Effective Strategies for the Online Classroom. San Francisco: Joseey-Bass.

Pérez-Mateo, M. & Guitert, M. (2012). Which Social Elements are Visible in Virtual Groups? Addressing the Categorization of Social Expressions. Computers & Education, 58, 1.234-1.246. (DOI:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.12.014).

Picciano, A. (2002). Beyond Student Perceptions: Issues of Interaction, Presence, and Performance in an Online Course. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 6(1), 21-40.

Pujolàs, P. (2008). Nueve ideas clave. El aprendizaje cooperativo. Barcelona. Graó.

Roberts, T. (2005). Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning in Higher Education: An introduction. In T. S. Roberts (Ed.), Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning in Higher Education. (pp. 1-18). Hershey: Idean Group Publishing.

Rodríguez Illera, J.L. (2001). Aprendizaje colaborativo en entornos virtuales. Anuario de Psicología, 32(2), 63-75.

Román, P. (2002). El trabajo colaborativo mediante redes. In J.I. Aguaded & J. Cabero (Eds.), Educar en Red. Internet como recurso para la educación. (pp. 113-134). Málaga: Aljibe.

Rubia, B. (2010). La implicación de las nuevas tecnologías en el aprendizaje colaborativo. Tendencias Pedagógicas, 16, 89-106.

Sangrá, A. (2010) (Coord.). Competencias para la docencia en línea: evaluación de la oferta formativa para profesorado universitario en el marco del EEES. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Programa Estudios y Análisis (EA2010/0059). (http://138.4.83.162/mec/ayudas/CasaVer.asp?P=29~~443) (16-04-2013).

Scardamalia, M. & Bereiter, C. (1994). Computer Support for Knowledge-building Communities. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 3 (3), 265-283.

Slavin, R. (1985). Learning to Cooperate, Cooperating to Learn. Nueva York: Plenum Press.

Sobreira, P. & Tchounikine, P. (2012). A Model for Flexibly Editing CSCL Scripts. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 7(4), 567-592. (DOI:10.1007/s11412-012-9157-9).

Stahl, G., Koschmann, T. & Suthers, D. (2006). Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning: An historical Perspective. In R.K. Sawyer (Ed.), Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences. (pp. 409-426). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Strijbos, J., Martens, R. & Jochems, W. (2004). Designing for Interaction: Six Steps to Designing Computer-Supported Group-based Learning. Computers & Education, 42, 403-424. (DOI:10.1016/j.compedu.2003.10.004).

Vygotski, L. (2000). Historia del desarrollo de las funciones psíquicas superiores. Barcelona: Crítica.

Webber, C. & Webber, M. (2012). Evaluating Automatic Group Formation Mechanisms to Promote Collaborative Learning. A Case Study. International Journal of Learning Technology, 7(3), 261-276. (DOI:10.1504/IJLT.2012.049193).

Document information

Published on 31/12/13

Accepted on 31/12/13

Submitted on 31/12/13

Volume 22, Issue 1, 2014

DOI: 10.3916/C42-2014-02

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?