Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Resumen

The use of technologies and the Internet poses problems and risks related to digital security. This article presents the results of a study on the evaluation of the digital competence of future teachers in the DigCompEdu European framework. 317 undergraduate students from Spain and Portugal answered a questionnaire with 59 items, validated by experts, in order to assess the level and predominant competence profile in initial training (including knowledge, uses and interactions and attitudinal patterns). The results show that 47% of the participants belong to the profile of teachers at medium digital risk, evidencing habitual practices that involve risks such as sharing information and digital content inappropriately, not using strong passwords, and ignoring concepts such as identity, digital “footprint” and digital reputation. The average valuations of each item in the seven categories show that future teachers have an average competence in the area of digital security. They have good attitudes toward security but less knowledge and fewer skills and practices related to the safe and responsible use of the Internet. Future lines of work are proposed, aimed at responding to the demand for a better prepared and more digitally competent citizenry. The demand for education in security, privacy and digital identity is becoming increasingly important, and these elements form an essential part of initial training.

Resumen

El uso de las tecnologías e Internet plantea problemas y riesgos relacionados con la seguridad digital. Este artículo presenta los resultados de un estudio sobre la evaluación de la competencia digital de futuros docentes en el marco europeo DigCompEdu. Participan 317 estudiantes de Grado de España y Portugal. Se aplica un cuestionario con 59 ítems validado por expertos con el objeto de conocer el nivel y perfil competencial predominante en la formación inicial (incluyendo conocimientos, usos e interacciones y patrones actitudinales). Los resultados muestran que el 47% de los participantes pertenecen al perfil de docentes en riesgo digital medio, evidenciando prácticas habituales que conllevan riesgos tales como compartir información y contenidos digitales de forma inapropiada, no utilizar contraseñas seguras, y desconocer conceptos como identidad, huella o reputación digital. Las valoraciones medias de cada ítem en las siete categorías evidencian que los futuros docentes poseen una competencia media en el área de seguridad digital. Tienen buenas actitudes hacia la seguridad, pero menos conocimientos, habilidades y prácticas relacionadas con el uso seguro y responsable de Internet. Se plantean futuras líneas de trabajo enfocadas a dar respuesta a la exigencia de una ciudadanía mejor preparada y más competente digitalmente. La demanda de formación en seguridad, privacidad e identidad digital está siendo cada vez más importante, reconociéndose que es muy necesaria en la formación inicial.

Keywords

Digital competence, teacher education, privacy, cyber security, Internet, teachers, university, initial training

Keywords

Competencia digital, formación del profesorado, privacidad, seguridad cibernética, Internet, docentes, universidad, formación inicial

Introduction

Digital competence takes the form of cognitive, attitudinal, and technical skills that help to mitigate numerous problems and challenges in the knowledge society. Dynamic and transversal, digital competence is considered as a key competence in developing a digital citizenry and as a crucial element in lifelong learning processes (Janssen, Stoyanov, Ferrari, Punie, Pannekeet, & Sloep, 2013).

Digital competence is the ability to use technologies critically and safely for work, leisure, and communication. It involves using them to recover, evaluate, store, produce, present, and exchange information, as well as to communicate and participate in collaboration networks through Internet (Parliament & European Council, 2006). Digital competence includes issues related to technology, information, multimedia, and communication that encourage critical, responsible, creative use of technology—issues fundamental to learning processes and participation in the 21st century (Esteve, Gisbert, & Lázaro, 2016; Napal, Peñalva-Vélez, & Mendióroz, 2018).

The framework for development of digital competence in Europe (DigComp) provides the structure for understanding and evaluating digital competence. This framework is consolidated and disseminated internationally through the European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu) (Redecker, 2017). In Portugal and Spain, it is used to evaluate users’ digital competence using different levels: basic (level A), intermediate or independent (level B), and advanced or competent (level C), based on the user’s knowledge, abilities, and skills.

In Latin America, it is adopted to search for, choose, and process information critically; communicate using various formats; act responsibly; and take advantage of technology to learn and to solve problems (Lueg, 2014). Digital teaching competence (DTC) is the comprehensive set of personal characteristics, knowledge, abilities, and attitudes required to act effectively in various teaching contexts (Tigelaar, Dolmans, Wolfhagen, & Van-der-Vleuten, 2004). It mobilizes abilities and skills related to use of ICT to generate knowledge (Flores-Lueng & Roig, 2016), stimulating more conscious and positive use of these media in education (Pedro & Chacon, 2017).

DTC involves knowing how to use technologies to teach and learn with didactic and pedagogical criteria and moral and ethical sense (Krumsvik, 2009). It is crucial to understand DTC from a holistic perspective—that is, both to integrate ICT properly into the curriculum and classroom and to ensure development of the student’s digital competence (Álvarez & Gisbert, 2015; Fernández-Cruz & Fernández-Díaz, 2016; Prendes, Castañeda, & Gutiérrez, 2010).

Safety in DTC

Safety in DTC involves protection of users’ information and communication against the problems generated by ICT use (Barrow & Heywood-Everett, 2006). It is related to the privacy, integrity, and efficiency of Internet technology and information (Anderson, 2003). Safety refers to teachers’ knowledge, abilities, and attitudes to design and develop learning experiences that promote, model, and train students as digitally responsible citizens.

People who teach play a special leading role in fostering acquisition of digital competence, since the teacher is a model and guide who cares for, orients, and trains others about responsible use of navigation, communication, and collaboration, as well as sharing information through Internet. This role can cause problems, however, due to a mistaken conception, that teachers teach about safety as if students only understood and had a single concept of Internet (Edwards & al., 2018).

DigComp (2016) and DigCompEdu (2017) have provided the foundation for developing a framework for digital competence of educators (MCCDD, 2017). They include competences concerning digital safety, such as protection of personal data and privacy, protection of health, and proper management of digital identity. The framework stresses responsible use, respect for the principles of online privacy that apply to oneself and others, and care for the environment.

In the area of safety, the competent user can “review the safety configuration of systems and applications, react if his/her computer equipment is infected with a virus, configure and/or modify the firewall and safety parameters of his/her electronic devices, encrypt emails and archives, and apply filters to avoid email spam” (http://bit.ly/30qMppL).

Research on digital safety (e-safety, digital safety, Internet safety, or Internet safety) is undertaken in different disciplines, such as Psychology, Education, and Law, and research has proliferated in the past decade (Jones, Mitchell, & Finkelhor, 2013; Shin, 2015; Šimandl & Vanícek, 2017; Chou & Peng, 2011; Napal, Peñalva-Vélez, & Mendióroz, 2018). Yet both in- and preservice teachers show low mastery of topics related to digital safety (De-Waal & Grösser, 2014).

Various reports, studies, and strategic plans attempt to help construct a climate of trust to mitigate or prevent the effects safety -related problems, especially in vulnerable groups, through actions such as incorporation of content on safety and responsible Internet use; design of itineraries to prevent, sensitize, raise awareness of, and improve trust and communication in Internet use; and foster the digital competence of parents and teachers, stressing social and emotional abilities to support and understand children’s use of ICT and the problems that can be avoided, among other issues.

Training of preservice teachers in digital safety

Education systems recognize the importance of training teachers in mastery of ICT, particularly concerning safety, but initial training teacher programs usually treat digital competence transversely (Napal, Peñalva-Vélez, & Mendióroz, 2018).

Initial training with a coherent approach is necessary, where safety should be taught as a matter of high priority in the educational field, especially in training programs within a common digital competence framework.

Study programs show a clear dispersion of required subjects on educational technologies, with differing presence across universities, polytechnics, and other institutions of higher education. There is no doubt that the preservice teacher needs knowledge (pedagogical and content-related), abilities (social and technical), and attitudes concerning digital safety and how to teach it. We expect teachers to assume responsibilities in teaching digital safety and orient their students to the rules for Internet behavior, but teachers often lack sufficient preparation to understand risks and unethical behavior (Chou & Peng, 2011). The educator can serve as a model to help improve students’ behavior when using technology, have conversations about risks and damage, and influence students significantly through his/her action (Chou & Chou, 2016; Šimandl, 2015; Shin, 2015).

In sum, initial training should be responsive to society’s current needs so that professionals adapt to innovation processes and can compete in and for use of technology on the labor market (Tejada & Pozos, 2018). Our new digital culture demands teachers who are useful, practical, and oriented to training critical, responsible citizens. Various studies indicate the pressing need for educational institutions centers to adopt coherent focus that guarantees training to promote safety as a high-priority question in education, especially in teacher training programs (Barrow & Heywood-Everett, 2006; Woollard, Wickens, Powell, & Rusell, 2009; Chou & Peng, 2011; Engen, Giæver, & Mifsud, 2015; Shin, 2015).

Work is being done internationally to improve safety in Asian and European organisms through education and training. In Taiwan, the TAIS program (2006-2010) identified four aspects for the training of competent teachers: safety and protection of communications, suitability of information, online safety and own use of technological devices.

In the EU, organisms such as the British Educational Communications and Technology Agency (BECTA) and various studies in Nordic countries and the Czech Republic stress training teachers and conclude that prior experiences, knowledge, practices, opinions, and perceptions determine how teachers should teach, resolve, and attend to digital safety problems (Engen, Giæver, & Mifsud, 2015; Šimandl & Vanícek, 2017). At global level, UNICEF proposes the importance of consolidating actions and educational measures for and from educational institutions, the shared responsibility of parents and teachers, and the need to dedicate educational resources to education and prevention programs that help to avoid threats and protect against the dangers of the digital world (United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), 2017).

The goals of our study are:

1) To identify preservice teachers’ level of digital competence in safety.

2) To describe the competence profile of preservice teachers in different areas of safety (interaction through technologies, sharing of digital information and contents, protection of personal data, protection of health, netiquette, digital identity, and cyberbullying on social networks and Internet).

3) To explore differences by sex, gender, and age at which one begins using social networks in each of the different areas in order to determine training needs to improve preservice teachers’ digital competence in safety.

4) To provide pedagogical activities in safety appropriate to preservice teachers’ strengths and weaknesses.

Material and methods

We perform a descriptive, transversal study of 317 undergraduates 18-43 years old (M=22.2; DT=4.8). The students are from four Spanish and one Portuguese university; 248 (78.2%) are women and 69 (21.8%) men.

|

|

The survey instrument is an ad hoc questionnaire for preservice teachers designed based on areas of safety from DigComp 2.0, DigCompEdu, the common framework for DTC (INTEF, 2017), the NETS*S project (ISTE, 2007), and a tool for self-diagnosis of digital competences from the Andalusian Regional Government (http://bit.ly/2YnNixx).

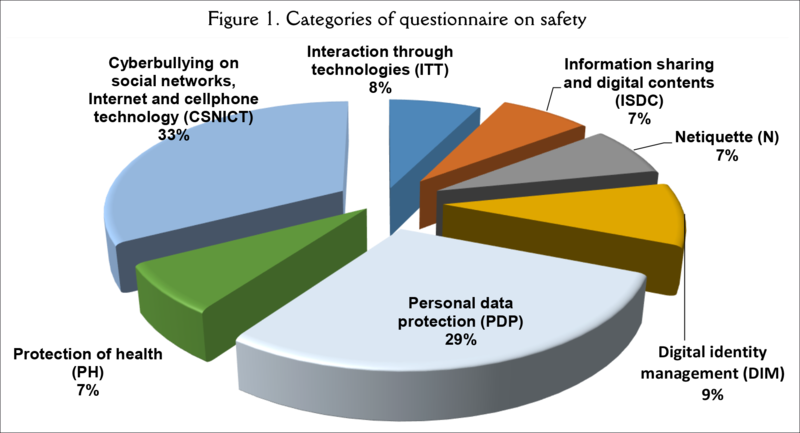

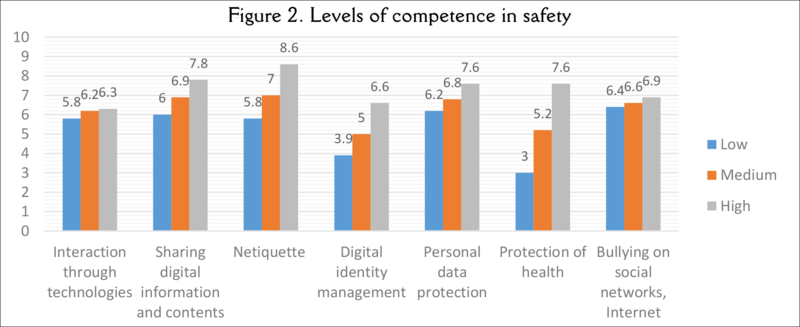

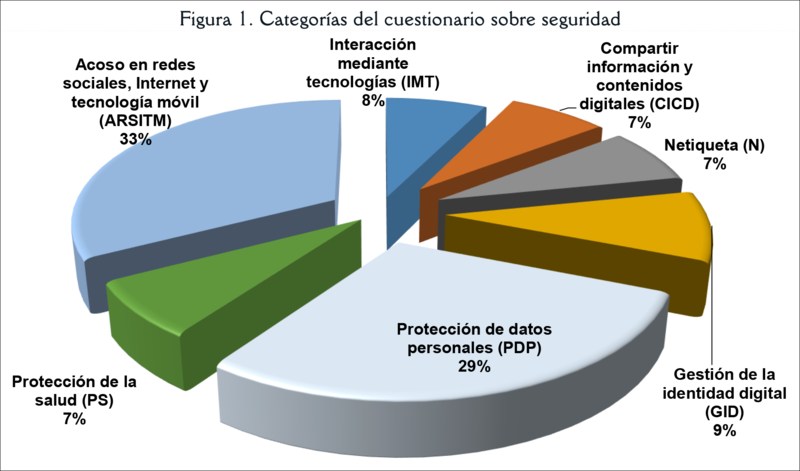

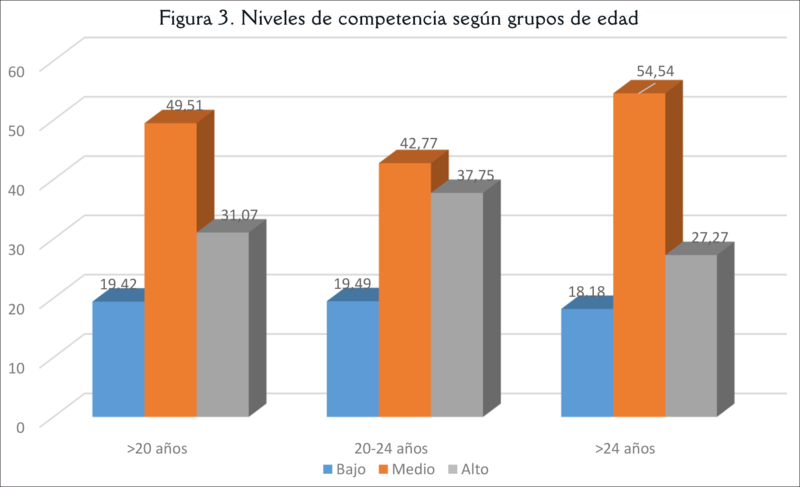

The questionnaire has 59 items divided into seven categories (Figure 1) and was validated by eight experts from Spanish and Portuguese universities with teaching and research experience in educational technologies. We obtain an Alpha Cronbach of α=.923, as well as values for the criteria of clarity (.916), relevance (.914), and importance (.946). The items are divided into knowledge (K=24 items), abilities and practices (A&P=23 items), and attitudes (A=10 items). Table 1 groups the items under these dimensions. The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 24.0. Using a two-stage cluster procedure, we classified the participants according to competence levels, with a three-category solution (significance level 5%). We also performed univariate descriptive analysis, calculating the mean and confidence interval at 95%, as well as the standard deviation. For the qualitative variables, we calculated frequency and percentage, and analyzed the relationship among them using the Chi-square test. With the nonparametric Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient, we analyzed the association among the numerical variables. To study the relationship between numerical and dichotomous variables, we applied the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test, calculating the effect size. The relationship between the categorical and numerical variables was analyzed using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test. For the tests with statistically significant results, we used the Mann-Whitney test to compare the categories by pairs.

|

|

Results

Levels of competence in digital safety

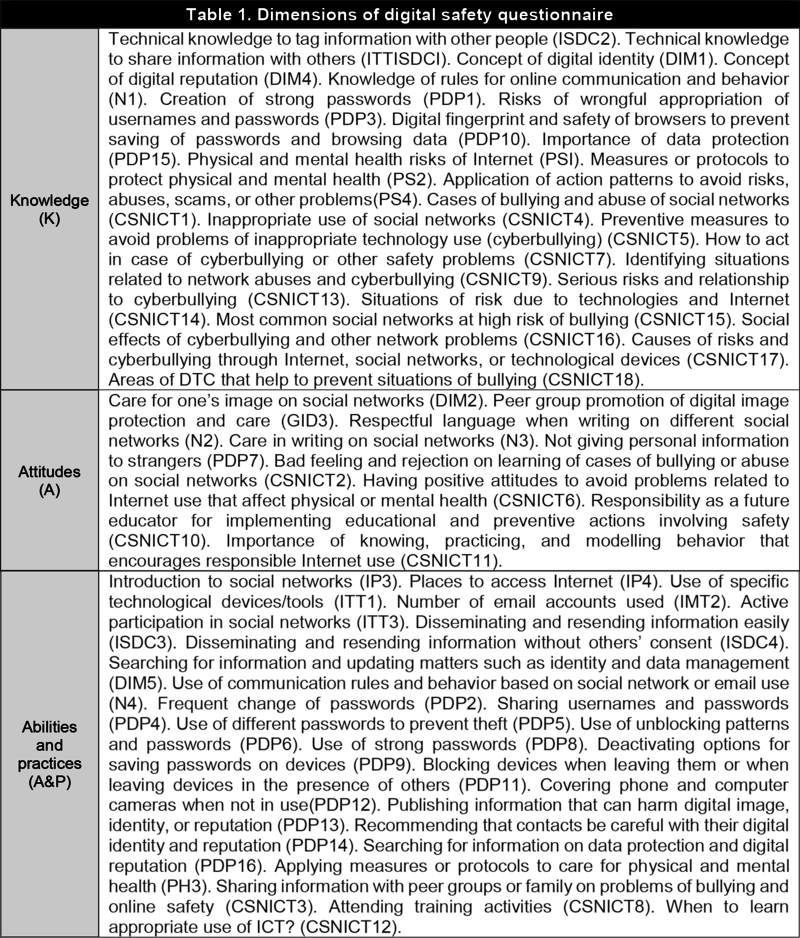

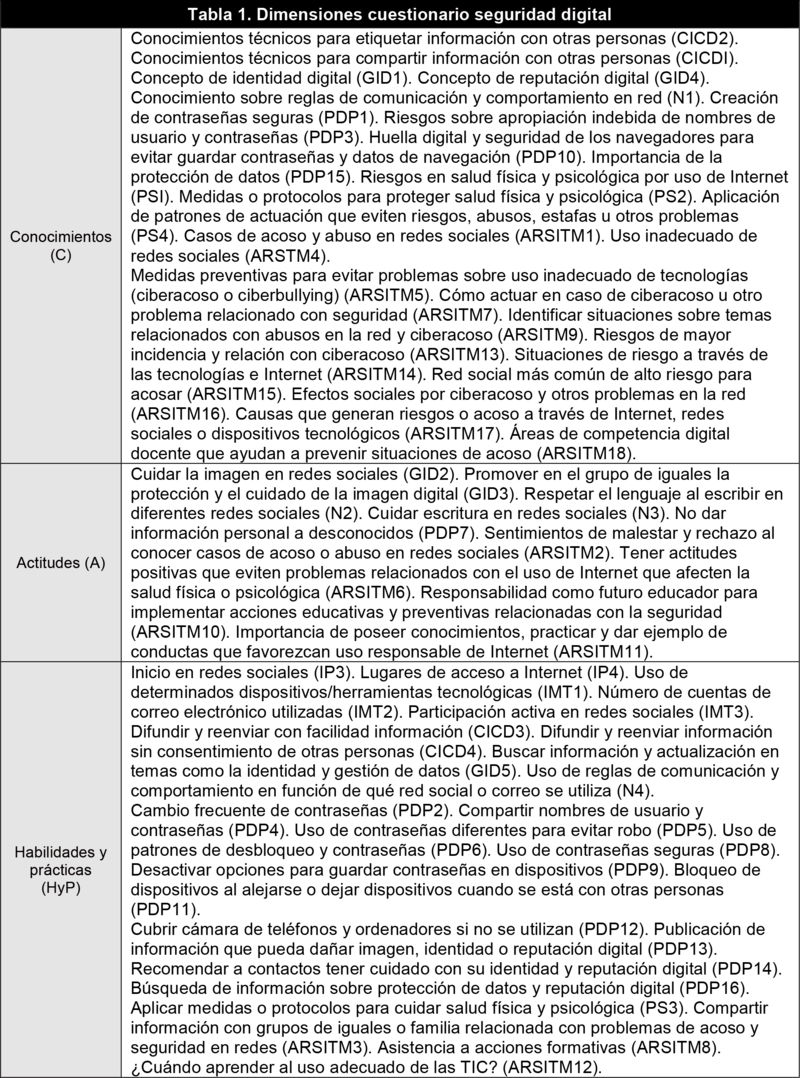

The analysis performed enabled us to identify three groups of digital competences in safety, with high, medium, and low levels, respectively. We compare the mean values for each category on the questionnaire (Figure 2).

In 34% of cases, we find “digitally secure teachers”. These participants use few technological devices, email accounts, and social networks (ITT); share information with the consent of third persons (ISDC); and know, apply, and respect the rules of communication and behavior (N). As to digital identity and reputation, they avoid publishing personal information that could affect their digital image (DIM), and use different passwords, which they change often. They know and use blocking patterns on their devices, avoid having their passwords recorded on devices that are not their own (PDP), and are aware of the importance of not letting Internet abuse affect their health (PH).

The medium level, “teachers at medium digital risk”, accounts for 47% of the cases. These participants are able to upload and share information on social networks (ISDC), know communication rules but do not always follow them (N), and care fortheir image on social networks. They may, however, have some personal data on Internet that does not correspond to reality (DIM). They avoid sharing their passwords and personal information on social networks and have information about account protection (PDP). They also have information about the risks Internet or excessive use that social networks pose to physical and mental health and know measures and protocols for protection, although they do not always follow these protocols (PH).

|

|

Among the preservice teachers,18% showed a low level and are thus considered as “teachers at digital risk”. These participants are always connected to Internet, have more than five devices, and use different email accounts and more than five social networks (ITT). They are able to upload and share photos and generally do not have difficulty managing social networks (ISDC). They do not know, and thus do not follow, rules for communication and behavior (N). Independently of the group to which they belong, only 7% of survey respondents had participated in some training activity on topics related to digital safety.

Profiles of competence in safety by age, gender, age at which one began social network use, and places of access to Internet

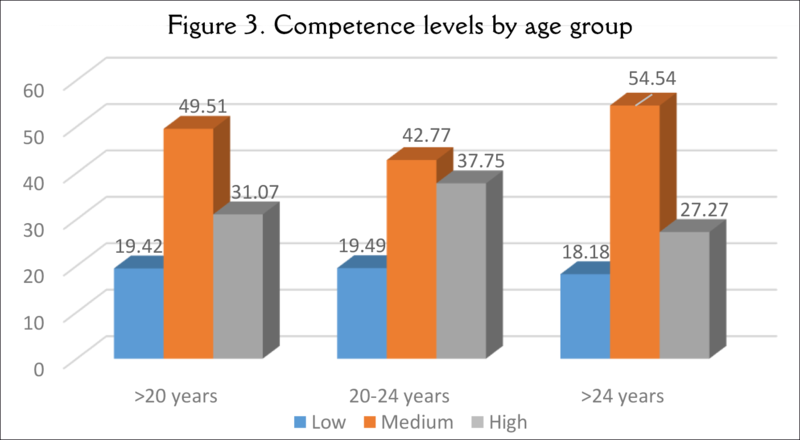

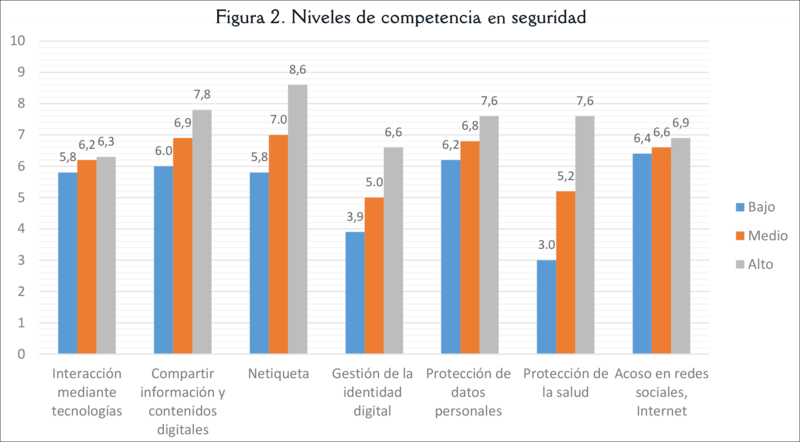

The age group 20-24 years old constitutes the largest number of participants (50%) in all three levels of safety competence. Students over 24 represent 17%. We can identify “digitally secure preservice teachers”, who show greater competence in netiquette (8.62), sharing digital information and content (7.76), personal data protection (7.64), and protection of health (7.64). This group shows lower values for bullying on social networks, Internet, and cellphones (6.87); digital identity management (6.59); and interaction through technologies (6.27).

Figure 3 illustrates this trend. The “preservice teachers at medium digital risk” show high values in the same categories, although the averages are lower: netiquette (6.97); sharing digital information and content (6.88); personal data protection and protection of health (6.76); bullying on social networks, Internet, and cellphones (6.64); and interaction through technologies (6.20). The categories for protection of health (5.24) and digital identity management (4.99) are even lower. The “preservice teachers at digital risk” show greater competence concerning bullying on social networks, Internet, and cellphones (6.40); personal data protection (6.20); sharing digital information and content (5.94); and netiquette (5.79). They show lower levels of competence, however, in digital identity management (3.93) and protection of health (3.04).

|

|

By gender, for all three competence groups, the highest percentage of women show medium-level competence (38% of cases), followed by those with a high level (23%) and a low level (15%). Of the total sample, 9% of men show a high level of competence, 8.5% a medium, and 4.4% a low level. For age at which respondents began to use social networks, individuals who started to use these networks before the age of 12 are significantly related to medium and high levels of competence. Those who started use between 12 and 14 years of age also show medium-level competence. The relationship between level of overall competence and low level of the three groups according to starting age is less significant. Competence level is significantly related to place(s) of access. Most individuals with a low competence level are always connected; groups with intermediate and high competence are connected a smaller percentage of the time. In the group with medium competence, nearly half of participants are connected from one specific place, while a similar percentage is always connected. Participants with high competence are connected more frequently from one place, although nearly half are always connected.

Differences in knowledge, attitude, ability, and practice

The results differ according to the dimensions of the questionnaire. First, knowledge (K) of digital safety had 24 items, with values ranging from 10 (CSNICT14 and 18) to 1.9 (CSNICT17), and an average of 6.7 (Table 2). The participants had the most knowledge on topics on preventing risky situations, personal data protection, and technical knowledge on sharing information with others. They had less knowledge of the rules of online communication and behavior, the effects of cyberbullying, measures or protocols for protection of physical and mental health, and concepts such as digital identity or digital reputation. The average point-values for the dimension attitudes (A) of the preservice teachers toward problems and risks associated with safety range from 10 (CSNICT10) to 6.24 (CSNICT6), with an average of 8.77. These items include the responsibility the teachers perceive when implementing educational and preventive measures related to safety; the need to acquire knowledge, practice, and model behavior that encourages responsible use; and feelings of discomfort and rejection when they learn of cases of abuse on social networks or other problems. Other attitudes involve not giving personal information to strangers, peer group promotion of protecting and caring for one’s virtual image, and having positive attitudes to avoid problems related to Internet use that affect physical or mental health.

On the dimension of secure Abilities and Practices (A&P), with 23 items, the averages ranged from 10 (CSNICT1 and CSNICT8) to 2.2 (CSNICT8), with the lowest average as 6.03. These items evaluate secure practices, including care in publishing information that can harm digital image, identity, or reputation; not sharing usernames and passwords; and using different passwords to avoid theft and blocking devices. Among the least secure practices were applying measures or protocols to care for physical and mental health, using technological devices and tools, disseminating and resending information easily, changing passwords infrequently, applying safety protocols in browsing and personal data protection, and participating in training activities related to safety.

Correlations among study variables

Table 2 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8150516) displays the nonparametric correlations among the numerical variables in the study. We see that age is positively related to the age at which one began to use social networks and interaction through technologies. These last two variables are also positively related to each other. Interaction through technological is negatively associated with digital identity management and protection of health, and positively associated with overall competence. Sharing digital information and content is positively associated with netiquette; digital identity management; personal data protection; protection of health; bullying on social networks, Internet, and cellphones; and overall competence. Netiquette is positively associated with digital identity management; personal data protection; protection of health; bullying on social networks, Internet, and cellphones; and overall competence. Digital identity management is positively related to personal data protection; protection of health; bullying on social networks, Internet, and cellphones; and overall competence. Personal data protection is also positively associated with protection of health and overall competence. Protection of heath is directly associated with bullying on social networks, Internet, and cellphones; and overall competence. These last two variables are also related to each other.

Analysis of the relationship of sex to age, age at which one began to use social networks, and competence in social networks shows that men start using social networks earlier than women (13.46 years vs. 13.76 years old). Competence in sharing digital information and content is greater among women (7.10) than among men (6.59). Competence in managing digital identity is greater in men (5.72) than in women (5.21). Finally, competence in protecting health is also greater in men (6.27) than in women (5.45). Participants’ age is only related to the age at which they began using social networks. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney tests indicate that starting age is lowest in the group under 20 years of age, followed by the group ages 20-24, and finally by those over 24. The age at which one began using social networks is significantly related to interaction through technologies. Participants who began before age 12 have less competence in this dimension than those who started at age 12-14 or later.

Discussion and conclusions

This study attempts to identify the levels and profiles of preservice teachers in digital safety in order to detect educational needs and propose activities for initial training at the university. To achieve this goal, we designed an instrument to demonstrate content validity and reliability, with a high Alpha Cronbach (Panayides, 2013).

Goal 1: To identify preservice teachers’ level of digital competence in safety, we performed a cluster analysis that enabled us to identify three levels of competence, corresponding to the categories of digital safety in the questionnaire. In evaluating the level of digital competence, 36.85% of the preservice teachers scored at medium level, a result similar to that obtained by Fernández-Cruz & Fernández-Díaz (2016) with preservice teachers from so-called “Generation Z” and Napal, Peñalva-Vélez, & Mendióroz (2018) with secondary school preservice teachers.

Goal 2: We describe the competence profile of preservice teachers by differentiating between “digitally secure teachers” (high level), “teachers at medium digital risk” (medium level), and “teachers at digital risk” (low level). In general, women 20-24 years old form the majority and share the common characteristic that 93% have received no training in this area, even if they attempt to use secure practices. Self-taught learning about safety was acquired outside formal education, but we find evidence of the need for formal training (Engen, Giæver, & Mifsud, 2015). The results show little difference by gender on the questionnaire categories (6.49 for men and 6.42 for women), although men have a slightly higher average in ISDC, N, PDP, and CSNCT. As to age, those under 20 are more competent in ISDC and PDP. The high-risk behavior profile is that of the individual who is always connected to Internet (Yan, 2009; Fernández-Montalvo, Peñalva, & Irazabal, 2015). The results by dimensions of knowledge (6.7), attitude (8.7), and abilities and practices (6.03) indicate greater willingness toward safety but less knowledge and practice related to secure, responsible use of Internet.

Goal 3: Exploring differences enables us to see the need to improve digital competence in safety (in the form of training activities) and prevention and education programs for secure, responsible Internet use (Chou & Peng, 2011; Fernández-Montalvo, Peñalva, & Irazabal, 2015). Such activities can enable the establishment of guidelines to improve secure, healthy abilities, and behavior through the network (Chou & Chou, 2016) —one of the dimensions that still presents considerable difficulties when evaluating digital competence (Napal, Peñalva-Vélez, & Mendióroz, 2018).

Why safety training? Although a significant body of research on digital competence focuses on evaluating technology or information literacy, hardly any studies focus specifically on areas of safety at university or on preservice teachers. We thus agree with Yan (2009) and Shin (2015) that preservice teachers do not receive sufficient training in this area. Our results show minimal training on questions of Internet safety.

Goal 4: This study proposes that safety is a determining factor in the acquisition of digital competence. Guaranteeing responsible, appropriate use of technology is the responsibility of courses in the area of Educational Technology for initial teacher training. Although institutions such as UNESCO, UNICEF, and the OECD, well as DigCompEdu in Europe, INTEF in Spain, and INCoDe.2030 in Portugal recognize digital safety in all areas as a difficult challenge, we understand both its importance in professionalizing educators to be digitally competent, secure, and responsible (Tejada & Pozos, 2018) and the value of information on the daily impact of technology on consumption and the environment for digital citizenship. This study has methodological limitations. The preservice teachers were drawn only from the fields of early childhood and primary education, and their participation in completing the online questionnaire was voluntary. The first of these conditions prevents generalizing the results to other levels of education. The second influenced the sample size.

What topics are crucial for training the future professional? The results of this study enable us to propose the following topics: rules for online communication and behavior (netiquette), measures and protocols to prevent risks on Internet and to care for physical and mental health, concepts related to digital safety (reputation, identity, digital divide and fingerprint), personal data protection in the field of education, and secure protection of devices and password creation.

Despite the limitation that there are few studies specifically on digital safety, we provide empirical evidence of the importance of initial training. This study shows the need for in-depth research on teaching digital safety, as well as for the promotion and inclusion of content on safety in university curricula − a measure already in place in other stages of education, along the lines of the PIES model (Šimandl & Vanícek, 2017), the CIPA program (Yan, 2009), and the TAIS project (Chou & Peng, 2011). Among future lines of research, we propose developing deeper knowledge of curricular inequalities across different university study programs (not only those that train teachers); researching the impact of training on matters of safety for external practices, initial training, and professional practice; and establishing how to teach and evaluate this area of competence beyond the preservice teacher’s mere self-perception. Evaluation can be advanced through interdisciplinary studies in Education, Psychology, Medicine, Economics, Law, and Engineering − areas with a close relationship to subcompetences related to safety.

References

- ÁlvarezJ., GisbertM., . 2015.literacy grade of secondary school teachers in Spain - Beliefs and self-perceptions. [Grado de alfabetización informacional del profesorado de secundaria en España: Creencias y autopercepciones&author=Álvarez&publication_year= Information literacy grade of secondary school teachers in Spain - Beliefs and self-perceptions. [Grado de alfabetización informacional del profesorado de secundaria en España: Creencias y autopercepciones]]Comunicar 45:187-194

- AndersonJ.M., . 2003.Why we need a new definition of information security.Computers & Security 22(4):308-313

- BarrowC., Heywood-EverettG., . 2006.The experience of English educational establishments: Summary and recommendations [online. British Educational Communications and Technology Agency (BECTA)]

- ChouC., PengH., . 2011.awareness of Internet safety in Taiwan in-service teacher education: A ten-year experience&author=Chou&publication_year= Promoting awareness of Internet safety in Taiwan in-service teacher education: A ten-year experience.The Internet and Higher Education 14(1):44-53

- ChouH.L., ChouC., . 2016.analysis of multiple factors relating to teachers' problematic information security behavior&author=Chou&publication_year= An analysis of multiple factors relating to teachers' problematic information security behavior.Computers in Human Behavior 65:334-345

- De-WaalE., GrösserM., . 2014.safety and security in education: Pedagogical needs and fundamental rights of learners&author=De-Waal&publication_year= On safety and security in education: Pedagogical needs and fundamental rights of learners.Educar 50(2):339-361

- EdwardsS., NolanA., HendersonM., MantillaA., PlowmanL., SkouterisH., . 2018.children's everyday concepts of the internet: A platform for cyber‐safety education in the early years&author=Edwards&publication_year= Young children's everyday concepts of the internet: A platform for cyber‐safety education in the early years.British Journal of Educational Technology 49(1):45-55

- EngenB.K., GiæverT.H., MifsudL., . 2015.Guidelines and regulations for teaching digital competence In schools and teacher education: a weak link?Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 10:172-186

- EsteveF.M., GisbertM., LázaroJ.L., . 2016.competencia digital de los futuros docentes: ¿Cómo se ven los actuales estudiantes de educación?&author=Esteve&publication_year= La competencia digital de los futuros docentes: ¿Cómo se ven los actuales estudiantes de educación?Perspectiva Educacional 55(2):38-54

- Fernández-CruzF.J., Fernández-DíazM.J., . 2016.Z's teachers and their digital skills. [Los docentes de la Generación Z y sus competencias digitales&author=Fernández-Cruz&publication_year= Generation Z's teachers and their digital skills. [Los docentes de la Generación Z y sus competencias digitales]]Comunicar 46:97-105

- Fernández-MontalvoJ., PeñalvaA., IrazabalI., . 2015.de uso y conductas de riesgo en Internet en la preadolescencia. [Internet use habits and risk behaviours in preadolescence&author=Fernández-Montalvo&publication_year= Hábitos de uso y conductas de riesgo en Internet en la preadolescencia. [Internet use habits and risk behaviours in preadolescence]]Comunicar 44:113-121

- Flores-LuegC., Roig-VilaR., . 2016.de estudiantes de Pedagogía sobre el desarrollo de su competencia digital a lo largo de su proceso formativo&author=Flores-Lueg&publication_year= Percepción de estudiantes de Pedagogía sobre el desarrollo de su competencia digital a lo largo de su proceso formativo.Estudios Pedagógicos 42(3):129-148

- Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia (Ed.). 2017.Niños en un mundo digital. Estado mundial de la Infancia 2017.

- Instituto Nacional de Tecnologías Educativas y Formación del Profesorado (Ed.). 2017. , ed. digital competence framework for teachers&author=&publication_year= Common digital competence framework for teachers. Madrid: INTEF.

- JanssenJ., StoyanovS., FerrariA., PunieY., PannekeetK., SloepP., . 2013.views on digital competence: Commonalities and differences&author=Janssen&publication_year= Experts' views on digital competence: Commonalities and differences.Computers & Education 68:473-481

- JonesL.M., MitchellK.J., FinkelhorD., . 2013.harassment in context: Trends from three youth internet safety surveys&author=Jones&publication_year= Online harassment in context: Trends from three youth internet safety surveys.Psychology of Violence 3(1):53-69

- KrumsvikR., . 2009.learning in the network society and the digitised school&author=Krumsvik&publication_year= Situated learning in the network society and the digitised school.European Journal of Teacher Education 32(2):167-185

- LuegC., . 2014.Competencia digital docente: Desempeños didácticos en la formación inicial del profesorado.Hachetetepé 9:55-70

- M.Napal,, A.Peñalva-Vélez,, A.Mendióroz,, . 2018.of digital competence in secondary education teachers’ training&author=M.&publication_year= Development of digital competence in secondary education teachers’ training.Education Sciences 8:104

- PanayidesP., . 2013.Alpha: Interpret with caution&author=Panayides&publication_year= Coefficient Alpha: Interpret with caution.Europe’s Journal of Psychology 9(4):687-696

- Parlamento y Consejo Europeo (Ed.). 2006.Recomendación 2006/962/CE, de 18 de diciembre de 2006, sobre las competencias clave para el aprendizaje permanente. Diario Oficial L 394 de 30 de diciembre de 2006.

- PedroK.M., ChaconM.C.M., . 2017.na internet: Uma análise das competências digitais de estudantes precoces e/ou com comportamento dotado&author=Pedro&publication_year= Pesquisas na internet: Uma análise das competências digitais de estudantes precoces e/ou com comportamento dotado.Educar em Revista 33(66):227-240

- PrendesM.P., CastañedaL., GutiérrezI., . 2010.para el uso de TIC de los futuros maestros. [ICT competences of future teachers&author=Prendes&publication_year= Competencias para el uso de TIC de los futuros maestros. [ICT competences of future teachers]]Comunicar 35:175-182

- RedeckerC., . 2017.European framework for the digital competence of educators: DigCompEdu. In: PunieY., ed. office of the European Union&author=Punie&publication_year= Publications office of the European Union.

- ShinS.K., . 2015.critical, ethical, and safe use of ICT in pre-service teacher education&author=Shin&publication_year= Teaching critical, ethical, and safe use of ICT in pre-service teacher education.Language Learning & Technology 19(1):181-197

- SimandlV., . 2015.teachers and technical e-safety: Knowledge and routines&author=Simandl&publication_year= ICT teachers and technical e-safety: Knowledge and routines.International Journal of Information and Communication Technologies in Education 4(2):50-65

- SimandlV., VaníčekJ., . 2017.on ICT teachers’ knowledge and routines in a technical e-safety context&author=Simandl&publication_year= Influences on ICT teachers’ knowledge and routines in a technical e-safety context.Telematics and Informatics 34(8):1488-1502

- TejadaJ., PozosK.V., . 2018.Nuevos escenarios y competencias digitales docentes: Hacia la profesionalización docente con TIC.Profesorado 22(1):41-67

- TigelaarD.E., DolmansD.H., WolfhagenI.H., Van-Der-VleutenC.P., . 2004.development and validation of a framework for teaching competencies in higher education&author=Tigelaar&publication_year= The development and validation of a framework for teaching competencies in higher education.Higher Education 48(2):253-268

- WoollardJ., WickensC., PowellK., RussellT., . 2009.of e‐safety materials for initial teacher training: Can ‘Jenny’s Story’make a difference?&author=Woollard&publication_year= Evaluation of e‐safety materials for initial teacher training: Can ‘Jenny’s Story’make a difference?Technology, Pedagogy and Education 18(2):187-200

- YanZ., . 2009.in high school and college students' basic knowledge and perceived education of Internet safety: Do high school students really benefit from the Children's Internet Protection Act?&author=Yan&publication_year= Differences in high school and college students' basic knowledge and perceived education of Internet safety: Do high school students really benefit from the Children's Internet Protection Act?Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 30(3):209-217

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El uso de las tecnologías e Internet plantea problemas y riesgos relacionados con la seguridad digital. Este artículo presenta los resultados de un estudio sobre la evaluación de la competencia digital de futuros docentes en el marco europeo DigCompEdu. Participan 317 estudiantes de Grado de España y Portugal. Se aplica un cuestionario con 59 ítems validado por expertos con el objeto de conocer el nivel y perfil competencial predominante en la formación inicial (incluyendo conocimientos, usos e interacciones y patrones actitudinales). Los resultados muestran que el 47% de los participantes pertenecen al perfil de docentes en riesgo digital medio, evidenciando prácticas habituales que conllevan riesgos tales como compartir información y contenidos digitales de forma inapropiada, no utilizar contraseñas seguras, y desconocer conceptos como identidad, huella o reputación digital. Las valoraciones medias de cada ítem en las siete categorías evidencian que los futuros docentes poseen una competencia media en el área de seguridad digital. Tienen buenas actitudes hacia la seguridad, pero menos conocimientos, habilidades y prácticas relacionadas con el uso seguro y responsable de Internet. Se plantean futuras líneas de trabajo enfocadas a dar respuesta a la exigencia de una ciudadanía mejor preparada y más competente digitalmente. La demanda de formación en seguridad, privacidad e identidad digital está siendo cada vez más importante, reconociéndose que es muy necesaria en la formación inicial.

ABSTRACT

The use of technologies and the Internet poses problems and risks related to digital security. This article presents the results of a study on the evaluation of the digital competence of future teachers in the DigCompEdu European framework. 317 undergraduate students from Spain and Portugal answered a questionnaire with 59 items, validated by experts, in order to assess the level and predominant competence profile in initial training (including knowledge, uses and interactions and attitudinal patterns). The results show that 47% of the participants belong to the profile of teachers at medium digital risk, evidencing habitual practices that involve risks such as sharing information and digital content inappropriately, not using strong passwords, and ignoring concepts such as identity, digital “footprint” and digital reputation. The average valuations of each item in the seven categories show that future teachers have an average competence in the area of digital security. They have good attitudes toward security but less knowledge and fewer skills and practices related to the safe and responsible use of the Internet. Future lines of work are proposed, aimed at responding to the demand for a better prepared and more digitally competent citizenry. The demand for education in security, privacy and digital identity is becoming increasingly important, and these elements form an essential part of initial training.

Keywords

Competencia digital, formación del profesorado, privacidad, seguridad cibernética, Internet, docentes, universidad, formación inicial

Keywords

Digital competence, teacher education, privacy, cyber security, Internet, teachers, university, initial training

Introducción

Con la competencia digital se evidencian destrezas cognitivas, actitudinales y técnicas que pueden ayudar a mitigar numerosos problemas y retos de la sociedad del conocimiento. Su naturaleza es dinámica y transversal, y se considera competencia clave en el desarrollo de la ciudadanía digital y fundamental en los procesos de aprendizaje para toda la vida (Janssen, Stoyanov, Ferrari, Punie, Pannekeet, & Sloep, 2013). Ser competente digitalmente es hacer un uso crítico y seguro de las tecnologías para el trabajo, el ocio y la comunicación e implica usarlas para recuperar, evaluar, almacenar, producir, presentar e intercambiar informaciones, así como para comunicar y participar en redes de colaboración a través de Internet (Parlamento & Consejo Europeo, 2006). Incluye aspectos tecnológicos, informacionales, multimedia y comunicativos que favorecen el uso crítico, responsable y creativo de la tecnología, fundamentales en los procesos de aprendizaje y participación de la sociedad del siglo XXI (Esteve, Gisbert, & Lázaro, 2016; Napal, Peñalva-Vélez, & Mendióroz, 2018).

El marco para el desarrollo de la competencia digital en Europa (DigComp) proporciona la estructura para su comprensión y valoración, y se consolida y expande internacionalmente con el marco europeo para la competencia digital de los educadores (DigCompEdu) (Redecker, 2017). En Portugal y España se emplea para evaluar la competencia digital del usuario, con diferentes niveles competenciales, básico (nivel A), medio o independiente (nivel B) y avanzado o competente (nivel C), en función de los conocimientos, habilidades y destrezas que este posee. En Iberoamérica se adopta para buscar, seleccionar y procesar críticamente información, comunicar usando diversos soportes, actuar con responsabilidad y aprovechar la tecnología para aprender y resolver problemas (Lueg, 2014).

La competencia digital docente (CDD) es el conjunto integrado de características personales, conocimientos, habilidades y actitudes necesarios para la actuación eficaz en diversos contextos docentes (Tigelaar, Dolmans, Wolfhagen, & Van-der-Vleuten, 2004). Moviliza habilidades y destrezas relacionadas con el uso de las TIC para generar conocimiento (Flores-Lueng & Roig, 2016) potenciando una utilización más consciente y positiva de los medios en educación (Pedro & Chacon, 2017). Conlleva saber usar las tecnologías para enseñar y aprender con criterios didácticos y pedagógicos y con sentido moral y ético (Krumsvik, 2009). Resulta fundamental entenderla desde una perspectiva holística, es decir, tanto para integrar las TIC adecuadamente en el currículo y en el aula, como para asegurar el desarrollo de la competencia digital del alumnado (Álvarez & Gisbert, 2015; Fernández-Cruz & Fernández-Díaz, 2016; Prendes, Castañeda, & Gutiérrez, 2010).

El área de seguridad en la Competencia Digital Docente

La seguridad adquiere un significado de protección de la información y comunicación de los usuarios contra los problemas generados por el uso de las TIC (Barrow & Heywood-Everett, 2006). Está relacionada con la privacidad, la integridad y la eficiencia de la tecnología e información de Internet (Anderson, 2003). Se refiere a los conocimientos, habilidades y actitudes del profesorado para diseñar y desarrollar experiencias de aprendizaje para promover, modelar y formar al alumnado como ciudadanos digitalmente responsables. Para adquirir esta competencia, el papel de quien enseña alcanza especial protagonismo, porque su figura es modelo y guía que cuida, orienta y forma sobre el uso responsable en la navegación, comunicación y colaboración y compartir información a través de Internet. Sin embargo, puede ser un problema debido a una concepción errónea por la que los docentes enseñan sobre la seguridad pretendiendo que el alumnado solo entienda o tenga un concepto sobre Internet (Edwards & al., 2018). DigComp (2016) y DigCompEdu (2017) han sido base para elaborar el marco de referencia de la competencia digital docente (MCCDD, 2017). Incluyen competencias sobre seguridad digital, como la protección de datos personales y el respeto a la privacidad, la protección de la salud, y la adecuada gestión de la identidad digital. Destacan el uso responsable, el respeto a los principios de privacidad en línea aplicables a sí mismo y a otros y el cuidado del medio ambiente. En el área de seguridad, el usuario competente es capaz de revisar la configuración de seguridad de los sistemas y las aplicaciones; reaccionar si su equipo informático se infecta con un virus, y configurar, modificar el cortafuegos y los parámetros de seguridad de sus dispositivos electrónicos; encriptar correos y archivos; aplicar filtros para evitar el spam del correo (http://bit.ly/30qMppL).

Las investigaciones sobre seguridad digital (e-safety, digital security, Internet safety o Internet security) se abordan desde diferentes disciplinas como Psicología, Educación y Derecho, y su producción aumenta en la última década (Jones, Mitchell, & Finkelhor, 2013; Shin, 2015; Šimandl & Vanícek, 2017; Chou & Peng, 2011; Napal, Peñalva-Vélez, & Mendióroz, 2018). Tanto el profesorado en servicio como los futuros docentes muestran bajo dominio en temas relacionados con la seguridad digital (De-Waal & Grösser, 2014).

Distintos informes, estudios y planes estratégicos buscan ayudar a construir un clima de confianza para mitigar o prevenir los efectos de los problemas relacionados con la seguridad, especialmente en colectivos vulnerables, mediante acciones como la incorporación de contenidos sobre seguridad y uso responsable de Internet; el diseño de itinerarios para la prevención, sensibilización, concienciación y mejora de la confianza y comunicación en el uso de Internet; el fomento de la competencia digital de padres y profesorado enfatizando habilidades sociales y emocionales para apoyar y entender el uso que hacen los menores de las TIC y los problemas que se pueden evitar, entre otros.

Formación de futuros docentes en seguridad digital

Los sistemas educativos reconocen la importancia de la formación del profesorado para el dominio de las TIC y en particular sobre la seguridad, aunque en los programas de formación inicial del profesorado el tratamiento de la competencia digital suele ser transversal (Napal, Peñalva-Vélez, & Mendióroz, 2018).

Es necesaria una formación inicial con un enfoque coherente donde se enseñe la seguridad como una cuestión de alta prioridad en el ámbito educativo, en especial en programas de formación en un marco común de competencia digital.

En los planes de estudio se observa una clara dispersión de las asignaturas obligatorias de tecnologías en la educación, y su presencia es distinta en universidades, institutos politécnicos u otros centros de Educación Superior. Indudablemente, el futuro docente necesita conocimientos (pedagógicos y de contenido), habilidades (sociales y técnicas) y actitudes vinculadas a la seguridad digital y cómo enseñarla.

Se espera que los docentes asuman responsabilidad en la enseñanza de la seguridad digital y orienten a los estudiantes sobre las normas de comportamiento en Internet, aunque es frecuente carecer de una preparación adecuada para entender los riesgos y los comportamientos poco éticos (Chou & Peng, 2011). El educador puede servir de modelo, ayudar a mejorar los comportamientos de los estudiantes cuando utilizan la tecnología, dialogar sobre riesgos y daños, e influir significativamente a través de su propia actuación (Chou & Chou, 2016; Šimandl, 2015; Shin, 2015).

En suma, la formación inicial debería responder a las necesidades actuales de la sociedad a fin de que los profesionales se adapten a los procesos de innovación y sean capaces de competir en y para el uso de la tecnología en el mercado laboral (Tejada & Pozos, 2018). Se reclama una nueva cultura digital para el docente útil, práctica y orientada a la formación de ciudadanos críticos y responsables.

Diversos estudios señalan la necesidad apremiante de que los centros de formación adopten un enfoque coherente que garantice la formación para promover la seguridad como una cuestión de alta prioridad en el ámbito educativo y en especial en programas de formación docente (Barrow & Heywood-Everett, 2006; Woollard, Wickens, Powell, & Rusell, 2009; Chou & Peng, 2011; Engen, Giæver, & Mifsud, 2015; Shin, 2015).

Se trabaja internacionalmente para mejorar la seguridad en organismos asiáticos y europeos a través de la educación y la formación. En Taiwán el programa TAIS (2006-2010) identificó cuatro aspectos para formar docentes competentes: la seguridad y protección de comunicaciones, la idoneidad de la información, la seguridad en línea y la propia del uso de dispositivos tecnológicos.

En la UE, organismos como British Educational Communications and Technology Agency (BECTA) y distintos estudios en países nórdicos y República Checa enfatizan la formación del profesorado, concluyendo que experiencias previas, conocimientos, prácticas, opiniones y percepciones determinarán cómo deberán los docentes enseñar, resolver y atender la problemática sobre seguridad digital (Engen, Giæver, & Mifsud, 2015; Šimandl & Vanícek, 2017). A nivel mundial, UNICEF plantea la importancia de la consolidación de acciones y medidas educativas para y desde los centros educativos, la responsabilidad compartida de padres y profesorado y la necesidad de destinar recursos educativos a programas educativos y preventivos que ayuden a evitar amenazas y a proteger contra los peligros del mundo digital (UNICEF, 2017).

Los objetivos del estudio son:

1) Identificar el nivel de competencia digital en el área de seguridad de los futuros docentes.

2) Describir el perfil competencial que tienen los futuros docentes en los diferentes ámbitos de la seguridad (interacción con tecnologías, compartir información y contenidos digitales, protección de datos personales, protección de la salud, netiqueta, identidad digital y acoso en redes sociales e Internet).

3) Explorar diferencias según sexo, género y edad de inicio en redes sociales en cada uno de los diferentes ámbitos, a fin de detectar necesidades formativas para mejorar su competencia digital en el área de seguridad.

4) Proponer acciones pedagógicas en el área de seguridad, apropiadas a las fortalezas y debilidades evidenciadas por los futuros docentes.

Material y métodos

Se realiza un estudio descriptivo y transversal en el que participaron 317 estudiantes de Grado entre 18 y 43 años de edad (M=22,2; DT=4,8), procedentes de cuatro universidades españolas y una portuguesa, de los cuales 248 (78,2%) son mujeres y 69 (21,8%) son hombres.

|

|

El instrumento es un cuestionario elaborado ad hoc para futuros docentes, diseñado a partir de las áreas de seguridad de DigComp 2.0, DigCompEdu, del marco común de competencia digital docente (INTEF, 2017), del proyecto NETS*S (ISTE, 2007), así como de la herramienta de autodiagnóstico de las competencias digitales de la Junta de Andalucía (http://bit.ly/2YnNixx).

El cuestionario, con 59 ítems distribuidos en siete categorías (Figura 1), ha sido validado por ocho expertos de universidades de España y Portugal con experiencia docente e investigadora en tecnologías en educación. Obtiene un Alfa de Cronbach α=.923, y en los criterios de claridad (.916), pertinencia (.914) e importancia (.946) respectivamente. Los ítems se distribuyen en conocimientos (C=24 ítems), habilidades y prácticas (HyP=23 ítems) y actitudes (A=10 ítems), agrupándose en las dimensiones de la Tabla 1.

|

|

El análisis estadístico se realiza con SPSS 24.0. Mediante un procedimiento clúster bietápico, se realiza la clasificación de los participantes en niveles de competencia, con una solución de tres categorías (nivel de significación 5%).

También se realiza un análisis descriptivo univariante, calculando la media e intervalo de confianza al 95%, así como la desviación típica. Para las variables cualitativas se ha calculado la frecuencia y porcentaje. La relación entre ellas se analiza mediante el test chi-cuadrado. Mediante el coeficiente de correlación no paramétrica Rho de Spearman se analiza la asociación entre las variables numéricas. Para estudiar la relación de las variables numéricas y las dicotómicas aplicamos la prueba no paramétrica de Mann-Whitney, calculando el tamaño del efecto.

La relación entre las variables categóricas y numéricas se analiza a través de la prueba no paramétrica de Kruskal-Wallis. En las pruebas que resultan estadísticamente significativas se ha utilizado el test de Mann-Whitney para comparar las categorías por pares.

Resultados

Niveles de competencia en seguridad digital

El análisis realizado permite identificar tres grupos de competencia digital en el área de seguridad con niveles alto, medio y bajo, respectivamente. Se comparan las valoraciones medias para cada una de las categorías del cuestionario (Figura 2).

|

|

El 34% de los casos son «docentes digitalmente seguros». Se caracterizan por usar pocos dispositivos tecnológicos, cuentas de correo electrónico y redes sociales (IMT); compartir información con el consentimiento de terceras personas (CICD); y conocer, aplicar y respetar normas de comunicación y comportamiento (N). En cuanto a la identidad y reputación digital, evitan publicar información personal que pueda afectar a su imagen digital (GID). Utilizan diferentes contraseñas que procuran cambiar frecuentemente. Saben y practican patrones de bloqueo en sus dispositivos y cómo evitar que sus contraseñas se queden grabadas en equipos ajenos (PDP) y son conscientes de la importancia de evitar que el abuso de Internet afecte su salud (PS).

El nivel medio, «docentes en riesgo digital medio», constituye el 47% de los casos. Se consideran con capacidad de subir y compartir información en redes sociales (CICD), conocen normas en la comunicación, aunque en ocasiones no las usan (N) y cuidan su imagen en redes sociales, pero pueden tener algún dato personal en Internet que no se corresponde con la realidad (GID). Evitan compartir sus contraseñas e información personal en redes sociales, y poseen información acerca de la protección de cuentas (PDP). Tienen información sobre los riesgos que Internet o el uso excesivo que las redes sociales tienen para la salud física y psicológica y conocen medidas y protocolos de protección aun cuando no siempre las aplican (PS). El 18% de los casos se ubica en el nivel bajo, «docentes en riesgo digital». Todo el tiempo están conectados, manejan más de cinco dispositivos, usan diferentes cuentas de correo y más de cinco redes sociales (IMT). Se consideran capaces de subir y compartir fotos y por lo general no encuentran dificultades en el manejo de las redes sociales (CICD). Desconocen y, por tanto, no suelen aplicar normas de comunicación y comportamiento (N). Con independencia del grupo al que pertenecen, solo el 7% ha participado en alguna acción formativa sobre temas relacionados con la seguridad digital.

Perfiles de competencia en seguridad

Teniendo en cuenta la edad, en el grupo 20-24 años se concentra el mayor número de participantes (50%) en los tres niveles de competencia en seguridad. Los mayores de 24 años representan el 17%. Se distinguen los «futuros docentes digitalmente seguros», que muestran una mayor competencia en netiqueta (8,62), en compartir información y contenidos digitales (7,76), protección de datos personales (7,64) y protección de la salud (7,64), aunque con menor puntuación en acoso en redes sociales, Internet y teléfonos móviles (6,87), gestión de la identidad digital (6,59) e interacción mediante tecnologías (6,27).

|

|

En la Figura 3 se aprecia esta tendencia. Los «futuros docentes en riesgo digital medio» obtienen valoraciones altas en las mismas categorías, aunque con medias menores: netiqueta (6,97), compartir información y contenidos digitales (6,88), protección de datos personales y protección de la salud (6,76), acoso en redes sociales, Internet y teléfonos móviles (6,64) e interacción mediante tecnologías (6,20). Aún son más bajas en las categorías protección de la salud (5,24) y gestión de la identidad digital (4,99). Los «futuros docentes en riesgo digital» muestran mayor competencia en acoso en redes sociales, Internet y teléfonos móviles (6,40), protección de datos personales (6,20), compartir información y contenidos digitales (5,94) y netiqueta (5,79). Muestran menor nivel competencial en los ámbitos de gestión de la identidad digital (3,93) y protección de la salud (3,04).

Según el género, en los tres grupos de competencia hay más mujeres, con un nivel medio de competencia el 38% de los casos, nivel alto el 23% y bajo el 15%. El grupo de hombres con un nivel alto representa el 9% del total, y tienen niveles medio y bajo el 8,5% y 4,4% respectivamente. De acuerdo a la edad de inicio en redes sociales, el nivel de competencia medio y alto tiene una relación significativa con quienes comenzaron a usarlas antes de los 12 años. También se observa en el nivel medio de quienes comenzaron entre 12-14 años. La relación entre nivel de competencia total y nivel bajo de los tres grupos de edad de inicio en redes sociales es menos significativa.

El nivel de competencia se relaciona significativamente con los lugares de acceso. La mayor parte de quienes tienen un nivel de competencia bajo están permanentemente conectados. El porcentaje es menor en los grupos con competencia media y alta. En el grupo con competencia media, casi la mitad se conectan desde un lugar determinado, mientras que un porcentaje similar se conecta permanentemente. Los participantes con competencia alta se conectan con más frecuencia desde un lugar, aunque casi la mitad lo hace con conexión permanente.

Diferencias en conocimientos, actitudes, habilidades y prácticas

Se evidencian diferencias en los resultados según las dimensiones del cuestionario. En la primera, conocimientos (C) sobre la seguridad digital, se han tenido en cuenta 24 ítems, cuyas valoraciones oscilan entre 10 (ARSITM14 y 18) y 1,9 (ARSITM17), obteniendo una media de 6,7. Las temáticas en las que los participantes poseen en mayor medida conocimientos son aquellas que ayudan a prevenir situaciones de riesgo, protección de datos personales y conocimientos técnicos para compartir información con otros. Menos conocimiento tienen sobre las reglas de comunicación y comportamiento en la red, los efectos sociales del ciberacoso, medidas o protocolos para proteger la salud física y psicológica y conceptos como identidad digital o reputación digital.

Las puntuaciones medias en la dimensión actitudes (A) de los futuros docentes sobre problemas y riesgos asociados con la seguridad varían entre 10 (ARSITM10) y 6,24 (ARSITM6), con una media de 8,77. Se considera la responsabilidad que perciben para implementar acciones educativas y preventivas relacionadas con la seguridad, la necesidad de adquirir conocimientos, practicar y dar ejemplo de conductas que favorezcan el uso responsable y sentimientos de malestar y rechazo cuando conocen casos de abuso en redes sociales u otros problemas. Otras actitudes implican no dar información personal a desconocidos, promover en el grupo de iguales la protección y el cuidado de la imagen virtual, tener actitudes positivas para evitar problemas relacionados con el uso de Internet que afecten la salud física o psicológica.

En la dimensión Habilidades y Prácticas seguras (HyP), con 23 ítems, las medias varían entre 10 (ARSITM1 y ARSITM8) y 2,2 (ARSITM8), y tiene el promedio más bajo (6,03). En ellos se valoran las prácticas seguras entre las que se encuentran el cuidado en la publicación de información que puede dañar imagen, identidad o reputación digital, evitar compartir nombres de usuario y contraseñas, uso de contraseñas diferentes para evitar robo y bloqueo de dispositivos. Y entre las prácticas menos seguras la aplicación de medidas o protocolos para cuidar la salud física y psicológica, uso de dispositivos y herramientas tecnológicas, difundir y reenviar información con facilidad, cambio de contraseñas poco frecuente, aplicación de protocolos de seguridad en navegación y de protección de datos personales y participación en acciones formativas relacionadas con seguridad.

Correlaciones entre variables del estudio

La Tabla 2 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8150516.v1) recoge las correlaciones no paramétricas entre las variables numéricas del estudio. Se observa que la edad está positivamente relacionada con la edad de inicio en redes sociales y la interacción mediante tecnologías. Estas dos últimas variables están positivamente relacionadas entre sí. La interacción mediante tecnologías se asocia negativamente con la gestión de la identidad digital y protección de la salud y positivamente con la competencia total. Compartir información y contenidos digitales está positivamente asociada con la netiqueta, la gestión de la identidad digital, la protección de datos personales, la protección de la salud, el acoso en redes sociales, Internet y móviles y la competencia total. La netiqueta se asocia positivamente con: la gestión de la identidad digital, la protección de datos personales, la protección de la salud, el acoso en redes sociales, Internet y móviles y competencia total. La gestión de la identidad digital se relaciona positivamente con: la protección de datos personales, la protección de la salud, el acoso en redes sociales, Internet y móviles y la competencia total. Protección de datos personales está además positivamente asociada a la protección de la salud y la competencia total. La protección de la salud se asocia directamente con el acoso en redes sociales, Internet y teléfonos móviles, así como con la competencia total. Estas dos últimas variables están también relacionadas entre sí.

En el análisis de la relación del sexo con la edad, edad de inicio en redes sociales y competencia en redes sociales se observa que los hombres se inician antes que las mujeres en las redes sociales (13,46 años Vs 13,76 años). La competencia de compartir información y contenidos digitales es mayor en mujeres (7,10) que en hombres (6,59). La competencia en gestión de la identidad digital es superior en hombres (5,72) que en mujeres (5,21). Por último, la competencia en protección de la salud es mayor también en hombres (6,27) que en mujeres (5,45).

La edad de los participantes únicamente está relacionada con la edad de inicio en redes sociales. Las pruebas no paramétricas de Mann-Whitney indican que la edad de inicio es menor en el grupo de menos de 20 años, seguido de los de 20-24 años, y por último los que tienen más de 24 años. La edad de inicio en redes sociales está significativamente relacionada con la interacción mediante tecnologías. Los participantes que se han iniciado antes de 12 años tienen menos competencia en esta dimensión que los que se han iniciado entre 12 y 14 y posteriormente.

Discusión y conclusiones

Con este estudio se trata de identificar los niveles y perfiles de futuros docentes en el área de seguridad digital, para detectar necesidades formativas que permitan plantear acciones en la formación inicial universitaria. Para ello se diseña un instrumento que muestra evidencias de validez de contenido y de fiabilidad, con una estimación alta del Alfa de Cronbach (Panayides, 2013).

Objetivo 1: Para identificar el nivel de competencia digital en el área de seguridad de los futuros docentes se realiza un análisis de clústers, que permite identificar tres niveles competenciales teniendo en cuenta las categorías de la seguridad digital del cuestionario. Al evaluar el nivel de competencia digital, el 36,85% de los futuros docentes obtienen un nivel medio, resultado similar al obtenido por Fernández-Cruz y Fernández-Díaz (2016) con futuros docentes de la denominada «Generación Z» y Napal, Peñalva-Vélez y Mendióroz (2018) con profesorado en formación de secundaria.

Objetivo 2: Se describe el perfil competencial que tienen los futuros docentes según la diferenciación entre «docentes digitalmente seguros» (nivel alto), «docentes en riesgo medio» (nivel medio) y «docentes en riesgo digital» (nivel bajo). En general predominan las mujeres de 20-24 años, que comparten como característica común que un 93% no se ha formado en esta área, aun cuando intentan realizar prácticas seguras. El aprendizaje autodidacta sobre la seguridad se ha adquirido fuera de la educación formal, pero se evidencia la necesidad de formación (Engen, Giæver, & Mifsud, 2015). En cuanto al género en relación con las categorías del cuestionario existe escasa diferencia (6,49 en hombres y 6,42 en mujeres), si bien los primeros tienen un promedio ligeramente superior en CICD, N, PDP y ARSITM. En cuanto a la edad, los menores de 20 años se muestran más competentes en CICD y PDP. El perfil con un comportamiento de alto riesgo para la seguridad se observa asociado al uso de Internet permanentemente (Yan, 2009; Fernández-Montalvo, Peñalva, & Irazabal, 2015). Los resultados según las dimensiones conocimientos (6,7), actitudes (8,7) y habilidades y prácticas (6,03) muestran que tienen mejor disposición hacia la seguridad, pero menos conocimientos y prácticas relacionadas con el uso seguro y responsable de Internet.

Objetivo 3: La exploración de diferencias permite apreciar la necesidad de mejorar la competencia digital en el área de seguridad, en forma de acciones formativas, programas de prevención y educativos para el uso seguro y responsable de Internet (Chou & Peng, 2011; Fernández-Montalvo, Peñalva, & Irazabal, 2015), que permitan establecer pautas para mejorar las habilidades y comportamientos seguros y saludables a través de la red (Chou & Chou, 2016), dado que es una de las dimensiones que, cuando se evalúa la competencia digital, aún muestra notables dificultades (Napal, Peñalva-Vélez, & Mendióroz, 2018).

¿Por qué formar en seguridad? Un importante cuerpo de estudios sobre competencia digital centra sus objetivos en evaluar el área de alfabetización tecnológica o informacional, pero apenas existen estudios que aborden específicamente el área de seguridad en el ámbito universitario o en futuros docentes. En ese sentido, coincidimos con Yan (2009) y Shin (2015) en que los futuros docentes no reciben suficiente formación en esta área y en este estudio hay resultados que muestran una mínima formación sobre cuestiones de seguridad en Internet.

Objetivo 4: Este estudio plantea que la seguridad constituye un factor determinante en la adquisición de la competencia digital. Garantizar un uso responsable y apropiado de la tecnología es compromiso de las asignaturas del área de Tecnología Educativa en la formación inicial. Aunque la seguridad digital en todos sus ámbitos se considera un desafío difícil por instituciones como la UNESCO, UNICEF u OCDE y por DigCompEdu en Europa, INTEF en España o INCoDe.2030 en Portugal, entendemos la importancia que tiene en la profesionalización de los educadores para ser digitalmente competentes, seguros y responsables (Tejada & Pozos, 2018) así como el valor de la información sobre el impacto diario de la tecnología en el consumo y el medio ambiente para la ciudadanía digital.

En esta investigación se reconocen limitaciones metodológicas, como que los futuros docentes se circunscriben a Educación Infantil y Primaria y también el carácter voluntario para cumplimentar online el cuestionario. La primera no posibilita la generalización a otros niveles educativos. En cuanto a la segunda, ese carácter influye en el propio tamaño de la muestra.

¿Qué temáticas son fundamentales para la formación del futuro profesional? Los resultados de este estudio permiten plantear las siguientes temáticas: reglas de comunicación y comportamiento en la Red (netiqueta), medidas y protocolos para prevenir riesgos en Internet y para cuidar la salud física y psicológica, conceptos relacionados con la seguridad digital (reputación, identidad, brecha, huella digital), protección de datos personales en el ámbito educativo, y protección de la seguridad en dispositivos y en creación de contraseñas. A pesar de la limitación que supone la escasez de referentes que tratan específicamente la seguridad digital, se ofrecen evidencias empíricas de la importancia que puede llegar a tener en la formación inicial. De este trabajo surge la necesidad de profundizar en la investigación sobre seguridad digital docente, así como promover e incluir en los currículos universitarios contenidos sobre seguridad como ya se hace en otras etapas educativas, en la línea del modelo PIES (Šimandl & Vanícek, 2017), del programa CIPA (Yan, 2009) o del proyecto TAIS (Chou & Peng, 2011).

Se plantean como futuras líneas de investigación: profundizar en las desigualdades curriculares existentes en planes de estudio universitarios diferentes y no solo en aquellos que forman profesorado, indagar sobre el impacto que puede tener la formación en materia de seguridad para las prácticas externas, en la formación inicial y en el ejercicio profesional, y cómo se puede enseñar y evaluar esta área competencial más allá de la mera autopercepción del futuro maestro mediante estudios interdisciplinares de educación, psicología, medicina, economía, derecho e ingeniería (áreas con una estrecha relación en subcompetencias relacionadas con el área de seguridad).

References

- ÁlvarezJ., GisbertM., . 2015.literacy grade of secondary school teachers in Spain - Beliefs and self-perceptions. [Grado de alfabetización informacional del profesorado de secundaria en España: Creencias y autopercepciones&author=Álvarez&publication_year= Information literacy grade of secondary school teachers in Spain - Beliefs and self-perceptions. [Grado de alfabetización informacional del profesorado de secundaria en España: Creencias y autopercepciones]]Comunicar 45:187-194

- AndersonJ.M., . 2003.Why we need a new definition of information security.Computers & Security 22(4):308-313

- BarrowC., Heywood-EverettG., . 2006.E-safety: The experience of English educational establishments: Summary and recommendations. British Educational Communications and Technology Agency (BECTA)

- ChouC., PengH., . 2011.awareness of Internet safety in Taiwan in-service teacher education: A ten-year experience&author=Chou&publication_year= Promoting awareness of Internet safety in Taiwan in-service teacher education: A ten-year experience.The Internet and Higher Education 14(1):44-53

- ChouH.L., ChouC., . 2016.analysis of multiple factors relating to teachers' problematic information security behavior&author=Chou&publication_year= An analysis of multiple factors relating to teachers' problematic information security behavior.Computers in Human Behavior 65:334-345

- De-WaalE., GrösserM., . 2014.safety and security in education: Pedagogical needs and fundamental rights of learners&author=De-Waal&publication_year= On safety and security in education: Pedagogical needs and fundamental rights of learners.Educar 50(2):339-361

- EdwardsS., NolanA., HendersonM., MantillaA., PlowmanL., SkouterisH., . 2018.children's everyday concepts of the internet: A platform for cyber‐safety education in the early years&author=Edwards&publication_year= Young children's everyday concepts of the internet: A platform for cyber‐safety education in the early years.British Journal of Educational Technology 49(1):45-55

- EngenB.K., GiæverT.H., MifsudL., . 2015.Guidelines and regulations for teaching digital competence In schools and teacher education: a weak link?Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 10:172-186

- EsteveF.M., GisbertM., LázaroJ.L., . 2016.competencia digital de los futuros docentes: ¿Cómo se ven los actuales estudiantes de educación?&author=Esteve&publication_year= La competencia digital de los futuros docentes: ¿Cómo se ven los actuales estudiantes de educación?Perspectiva Educacional 55(2):38-54

- Fernández-CruzF.J., Fernández-DíazM.J., . 2016.Z's teachers and their digital skills. [Los docentes de la Generación Z y sus competencias digitales&author=Fernández-Cruz&publication_year= Generation Z's teachers and their digital skills. [Los docentes de la Generación Z y sus competencias digitales]]Comunicar 46:97-105

- Fernández-MontalvoJ., PeñalvaA., IrazabalI., . 2015.de uso y conductas de riesgo en Internet en la preadolescencia. [Internet use habits and risk behaviours in preadolescence&author=Fernández-Montalvo&publication_year= Hábitos de uso y conductas de riesgo en Internet en la preadolescencia. [Internet use habits and risk behaviours in preadolescence]]Comunicar 44:113-121

- Flores-LuegC., Roig-VilaR., . 2016.de estudiantes de Pedagogía sobre el desarrollo de su competencia digital a lo largo de su proceso formativo&author=Flores-Lueg&publication_year= Percepción de estudiantes de Pedagogía sobre el desarrollo de su competencia digital a lo largo de su proceso formativo.Estudios Pedagógicos 42(3):129-148

- Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia (Ed.) . 2017.Niños en un mundo digital. Estado mundial de la Infancia 2017. UNICEF.

- Instituto Nacional de Tecnologías Educativas y Formación del Profesorado (Ed.). 2017.Common digital competence framework for teachers.

- JanssenJ., StoyanovS., FerrariA., PunieY., PannekeetK., SloepP., . 2013.views on digital competence: Commonalities and differences&author=Janssen&publication_year= Experts' views on digital competence: Commonalities and differences.Computers & Education 68:473-481

- JonesL.M., MitchellK.J., FinkelhorD., . 2013.harassment in context: Trends from three youth internet safety surveys&author=Jones&publication_year= Online harassment in context: Trends from three youth internet safety surveys.Psychology of Violence 3(1):53-69

- KrumsvikR., . 2009.learning in the network society and the digitised school&author=Krumsvik&publication_year= Situated learning in the network society and the digitised school.European Journal of Teacher Education 32(2):167-185

- LuegC., . 2014.Competencia digital docente: Desempeños didácticos en la formación inicial del profesorado.Hachetetepé 9:55-70

- M.Napal,, A.Peñalva-Vélez,, A.Mendióroz,, . 2018.Development of digital competence in secondary education teachers’ training.Education Sciences 8:104

- PanayidesP., . 2013.Alpha: Interpret with caution&author=Panayides&publication_year= Coefficient Alpha: Interpret with caution.Europe’s Journal of Psychology 9(4):687-696

- Parlamento y Consejo Europeo (Ed.). 2006.18 de diciembre de 2006, sobre las competencias clave para el aprendizaje permanente. Diario Oficial L 394 de 30 de diciembre de.

- PedroK.M., ChaconM.C.M., . 2017.na internet: Uma análise das competências digitais de estudantes precoces e/ou com comportamento dotado&author=Pedro&publication_year= Pesquisas na internet: Uma análise das competências digitais de estudantes precoces e/ou com comportamento dotado.Educar em Revista 33(66):227-240

- PrendesM.P., CastañedaL., GutiérrezI., . 2010.para el uso de TIC de los futuros maestros. [ICT competences of future teachers&author=Prendes&publication_year= Competencias para el uso de TIC de los futuros maestros. [ICT competences of future teachers]]Comunicar 35:175-182

- RedeckerC., . 2017.European framework for the digital competence of educators: DigCompEdu. In: PunieY., ed. office of the European Union&author=Punie&publication_year= Publications office of the European Union. Luxembourg: Joint Research Centre.

- ShinS.K., . 2015.critical, ethical, and safe use of ICT in pre-service teacher education&author=Shin&publication_year= Teaching critical, ethical, and safe use of ICT in pre-service teacher education.Language Learning & Technology 19(1):181-197

- SimandlV., . 2015.teachers and technical e-safety: Knowledge and routines&author=Simandl&publication_year= ICT teachers and technical e-safety: Knowledge and routines.International Journal of Information and Communication Technologies in Education 4(2):50-65

- V.Simandl,, J.Vaníček,, . 2017.on ICT teachers’ knowledge and routines in a technical e-safety context&author=V.&publication_year= Influences on ICT teachers’ knowledge and routines in a technical e-safety context.Telematics and Informatics 34(8):1488-1502

- TejadaJ., PozosK.V., . 2018.Nuevos escenarios y competencias digitales docentes: Hacia la profesionalización docente con TIC.Profesorado 22(1):41-67

- TigelaarD.E., DolmansD.H., WolfhagenI.H., Van-Der-VleutenC.P., . 2004.development and validation of a framework for teaching competencies in higher education&author=Tigelaar&publication_year= The development and validation of a framework for teaching competencies in higher education.Higher Education 48(2):253-268