Despite media, investors and economists mostly talking about Technology or Tech Companies when addressing digitalization, we will try - and hopefully prove - in this paper that digital means much more and far outreaches technology. We want to argue that making a clear difference between Technology and Digital goes beyond semantics and offers a decisive edge towards getting to grips with the ground-shaking impacts of the fast-paced emerging or yet to emerge digitalization trends.

We start with a bit of history, first describing how the information technology (IT) era blossomed in the eighties and nineties, and how best to characterize the “Tech” era.

We look at how Apple actually pivoted at breakneck speed to become a digital company.

We make the point that the Internet giants that have emerged in the 21st century are all digital, which explains why they have grown so fast.

We try to pinpoint the precise date of the shift from Technology to Digital; 2007, the year of the launch of the iPhone, comes as a strong #1 suspect.

We describe how the sectorial definition of stock markets is about to evolve – the announcement has been made -, now making a clean distinction between Technology and Digital, in order to stay relevant.

Once stated the structural difference between technology and digital, we focus on two economic impacts: the so-called productivity paradox and the rising societal issues the digital era fuels.

We indifferently talk of Technology, Tech, Information Technology or IT. There are other industries with a strong technology content, notably BioTechnology, but we believe that whenever people talk of Tech, they refer to IT, unless stated otherwise. On the opposite, we believe that AdTech, AgTech, CarTech, FinTech, InsurTech, and RegTech are nothing but vertical instantiations of the digital era.

A brief history of IT

Information Technology (IT) in its modern sense first appeared as such in a 1958 article published in the Harvard Business Review by Harold J. Leavitt and Thomas L. Whisler.

IT would simply not exist without the formidable technological revolution the semiconductor industry underwent, often referred to as Moore’s Law. What was initially an empirical observation made in 1965 by Gordon Moore, co-founder of Fairchild Semiconductor and Intel, in a paper dated 1965 - that the number of transistors in a dense integrated circuit doubles approximately every two years - has proved to be amazingly prescient: the Moore’s Law still remains valid nowadays. For those who have trouble making sense of exponentials, let’s remind that a number doubling every two years on a 53-year period (1965 to 2018) ends up being multiplied by a whopping factor of 95 million. If a car were to follow the Moore’s Law, its weight would have shrunk to… 0.02g, the weight of one single grain rice. There is historically very few - if any - comparable technological breakthrough of such magnitude.

Fueled by the Moore’s Law, computers became ever faster, smaller, and cheaper. Different eras of computer hardware disruptions occurred over time: mainframes in the 60’s, minicomputers in the 70’s, workstations in the 80’s, PCs in the 90’s, and smartphones in 2007. The next step is likely to be billions of smart connected sensors forming what is often referred to as Internet of Things (IoT).

One level up in the food chain is software. Ever more processor power enables increasingly sophisticated software. In a quest to enlarge the addressable market, software engineers were able to progressively make the access to IT ever closer to the way humans interact naturally. This is how we evolved from the punch cards of the first mainframes, to terminals for minicomputers, mouse- and keyboard-based graphical user interfaces for the PC, and touch-based for smartphone users. The next step is likely to be voice-activated interaction as voice is the way we humans interact the most naturally. Recent progress in machine learning means that voice interaction is ready to be deployed to the masses1. One day, we may even be able to connect directly our brain to computers through what is called brain computer interfaces2. No need to talk anymore, just think about what you want to do or to know...

Yet another way up the food chain we meet business software that helps organizations run better and faster: productivity software (namely Microsoft’s Office); software for managing the life cycle of products (PLM); accounting, financial reporting and budgeting; managing manufacturing and optimizing supply chain, point-of-sales purchasing…

Each era brought new corporate champions. Some are still around as they have been able to reinvent themselves throughout the different inflection points; a lot are gone. Few remember the names of the losers. Competing against IBM were Univac, Control Data, NCR, Honeywell. Compaq, IBM, Toshiba, and Gateway were market leaders in the PC market. Minicomputer championship Digital Equipment Corporation name only remains present in IT history books. Sun Microsystems literally owned the workstation market; it’s gone, acquired by Oracle. Those trying to confront Microsoft, such as Hardware Graphics or Lotus are long gone. EMC used to be the name of the game for storage systems; it was acquired by Dell... In short, the adage, history only remembers the winners, applies very well to a very Darwinian IT industry. A few made it through. The surviving hardware champions are IBM, HP, Lenovo, and Dell. For the software eras, these are SAP, Microsoft, Oracle, Adobe. We should also mention networking giants such as Cisco Systems and Ericsson; and semiconductor and semi equipment vendors such as Intel, TSMC, Texas Instruments, Samsung Electronics, Applied Materials. The sheer size of these technology champions, a combined annual revenue of 778 billion US dollars, is a testament to the economic power the IT industry has gained over time.

Despite a quite bumpy history, the fundamental mission of IT has never changed. It is about helping organizations to improve productivity, time-to-market, and agility. IT is a formidable tool to automate low productivity jobs. SAP-like business software has proved to be a very powerful way to align internal processes across subsidiaries. Global companies would simply not exist without it. Not only global companies are more productive; they are also much more reactive, able to adapt to changing economic environments incredibly faster than in the past. Inventory and supply chain management are greatly improved, which translates into much better cash flow. IT is essentially a major contributor to productivity, profitability, agility and cash flow generation. Productivity grew strongly and steadily indeed in the heydays of IT.

The IT stack, hardware, networking, storage, system software, and business software can be compared to a DIY3 Ikea piece of furniture: one must assemble it himself. This is the mission of the IT department: picking the right suppliers, assembling different components, testing, running the system and supporting internal users, a full-time job. The very notion of having an IT department is something actively pushed in the early days of IT by IBM, in need of a dedicated professional counterpart to talk to, and to sell more to. Because of the constant evolving nature of IT, organizations can't handle that all by themselves. In free market economies, demand is always met by supply. So, over time, independent service providers grew to service organizations. IT service offerings range from consulting, training, software development, business software tuning to specific business needs, running or hosting systems on behalf of clients... In some cases, service companies run the whole process, not just the underlying system: this is what Business Process Outsourcing is about. Today, service accounts for about a third of the total IT industry. Accenture, Cap Gemini or IBM are among the top service players.

Well-run organization always run their financials through a budgeting process. A budget is set for every department or business unit early in the year, adjusted up or down during the year depending on how the organization is doing or how the external environment has evolved. For this reason, departments spend cautiously until they are sure, at the end of the year, that their budget will not be revised down. At that point, they can spend the remaining budget. Being a department, IT follows the same rules. Most of the time, IT spending is reported as “General & Administrative” (G&A) spending (the other two main operating reporting categories are “Sales & Marketing” and “R &D”).

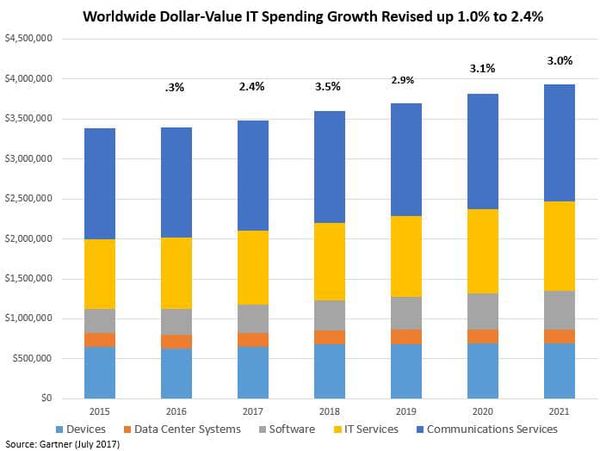

We can now infer that the addressable market for IT closely follows G&A spending. As public companies are constantly pushed to improve their productivity, G&A, being “indirect spending”, is often pressured down from top management. IT therefore is somewhat torn apart between ever growing needs and a constant race to push costs down. Let’s remember that, as a rule, G&A represents only a few percentage of total revenues. Simply put, the addressable market for IT is finite, limited by the G&A threshold. For the past few years, IT corporate spending has grown roughly like GDP, according to Gartner Group.

At the end of the nineties, the IT ecosystem branched out to consumers. This move was made possible by the decreasing price of PCs, printers, networking devices and, later in the early 2000s, broadband Internet access. This market remains limited in scope: indeed, very few people want to spend their leisure time running Excel or PowerPoint…

Years before PCs became affordable enough to the average household, consumers were already attracted by two true digital consumer product categories: gaming and mobile devices.

Gaming console market kicked off in the early 80’s thanks to Nintendo and Sega. Portable game consoles followed soon with the announcement of the Nintendo’s Game Boy in 1989. Of all initial game console vendors, only Nintendo and Sony thrived, and Sega survived. Microsoft believed for years a PC was the ultimate gaming console, resisted for years until it reversed course and launched the Xbox in 2001. Very powerful and profitable gaming companies emerged in the process: Electronics Arts, Activision/Blizzard, Sony, Nintendo, Microsoft, NetEase, Tencent to name but a few.

In the early 90’s, the first generation of digital mobile phone systems emerged. The killer application was the ability to make phone calls on the go. Their price and weight plummeted swiftly. Over time, handsets became more data-capable: the smartphone era began, fostered by the popularity of Blackberry devices in the late 90s. Eventually, the smartphone as we know it was invented by Apple in 2007. The vendors who made it so far are Samsung, Apple, Xiaomi, Oppo4… and of course Google, under the cloak of Android, the dominant smartphone operating system. The bottom line is that the consumer market has an entire distinct profile from corporate IT: buyers are different, the go-to-market strategy is different, branding is different, and unsurprisingly, vendors are different. As such, the consumer market can indeed not be considered as a part of the IT market.

All that said, we can characterize IT according to the following criteria: IT companies sell technology components; the revenues of the IT industry are closely correlated to global corporate G&A spending; productivity is a relevant metric to measure the outcome of IT spending.

2007, the year Apple Computer became Apple

Apple Computer was indisputably the first to successfully market personal computers. Its inspiration came from the PARC, the research arm of Xerox at that time, but Apple greatly improved the graphical user interface and made it extremely fast, easy to use and intuitive. Despite being first-to-market, the irruption of Microsoft’s Windows proved to be a very tough challenge. Microsoft licensed Windows to every PC manufacturer bar Apple, who stuck to its proprietary business model). IT departments always seek to standardize on a platform to make their life easier; the standard was Windows. In the mid-nineties, with Microsoft's Windows 95 flying off the shelves, Apple’s Macintosh was banned from most organizations. This brought Apple on the brink of bankruptcy… until Steve Jobs came back in 1997.

During the following years, with Steve Jobs at the helm, Apple Computer’s DNA underwent a progressive yet radical mutation. First came iMacs, envisioned as the ultimate multimedia personal computers, thanks to new applications wrote by Apple itself: iTunes, iMovie, GarageBand, Photos, Keynote. Then, the idea of a portable light-weight intuitive music player came up; the iPod was born in 2001 and sales started to skyrocket in 2005. As it appeared that music players and mobile phones were poised to merge, putting Apple in a defensive mode, the company managed a tour-de-force and released the iPhone, with its revolutionary touch-based user interface, in 2007. It went on to invent the tablet with the iPad announced in 2010. With each incremental step, Apple moved further away from IT territories into Consumer Goods. In January 2007, Steve Jobs announced the Apple TV and, “one more thing “, the iPhone. With three consumer products (iPod, iPhone, Apple TV) out of a total of four (the fourth being the iMac), Steve Jobs announced that Apple Computer would become Apple, turning 2007 into an historical milestone for the company: Apple no longer considered itself a technology company.

Innovation at Apple would no longer be funneled to make better technology products. Instead, technology would be a lever to reinvent an industry. Indeed, the iPod revolutionized the music industry, creating a whole new digital music market Apple would dominate, and badly damaging the music industry5. Music majors did not see it coming but Apple had a pretty good vision of what they wanted to achieve; the result was probably beyond their biggest dream.

Apple went on with the iPhone. In 2007, Nokia dominated the handset market with a 40%+ market share and a market cap of €109 billion as of October 29, 2007. Six years later, Nokia "stood on a burning platform6" and had no choice but to sell its Devices and Services unit to Microsoft, for a mere €5.5 billion. Two years after, Microsoft wrote-off the entire business and decided to quit the smartphone market. It is estimated that the iPhone has replaced no less than 23 products as shown below7.

Meanwhile, Apple’s market capitalization grew by a factor of nearly 12X, from $74 billion to nearly $852 billion8 to become the largest company worldwide as far as market value is concerned. The economist Joseph Schumpeter would have certainly agreed to consider this as one of the best illustration of creative destruction…

With the iPod and the iPhone, Apple did not try to sell or license technology to Nokia or Sony, but instead went directly after the huge consumer goods market, a much broader addressable market than IT. It did so by inventing new markets: portable digital music players, smartphones, tablets, smartwatches…

For companies such as Apple, revenue growth depends on their capacity to attract, some would even say to convert consumers, following a typical S-Curve pattern: in 2007, the penetration of smartphones in the sales of new mobile devices was nil; in 2018, it is about 90%. The beauty of a S-Curve is that revenue growth only depends on the ability of a company to navigate along the curve, outsmarting competitors in the execution phases. Digitalization becomes the main growth driver, hence insulating these companies from global economic cyclical downturns.

We call such companies Digital and no longer Tech because we can see that a digital company has nothing to do with a technology company. However outstanding as it may seem, Apple is only one among many digital winners.

From Technology to Digital, a new era

Very few technology companies did what Apple pulled out. Most technology companies do not change course. Doing so is a huge challenge for an established company; only a visionary, undisputed leaders such as Steve Jobs could envision it, embody it, galvanize his team to make it happen and turn it into a smashing success.

The following generation of entrepreneurs did not even bother to start as a technology company; they jumpstarted directly with a digital business model. Let’s review a few examples.

In 1995, Frenchman Pierre Omidyar founded eBay with the basic idea that Internet was a great medium to help buyers and sellers around the world trade a wide variety of goods and services. The website would be free for buyers, and sellers would be charged fees for listing items. Hence, eBay’s revenues are directly related to the volume in dollars of transactions on its web site. derived from a commission taken on every sale on eBay’s web site. eBay went public in September 1998. It is valued today9 $42 billion. In July of 2015, eBay spun off PayPal as an independent company. PayPal is a digital payment processor, taking a cut out of each payment transaction it handles. PayPal is valued $102 billion10.

In 1994, Jeff Bezos left his employment as vice-president of a Wall Street firm, and moved to Seattle, Washington. He began to work on a business planfor what would eventually become Amazon.com. Bezos named his company "Amazon" because it was a place that was "exotic and different", just what he wanted his Internet venture to be. The Amazon River, he noted, was the biggest river in the world, and he planned to make his store the biggest bookstore in the world10. Amazon, excluding Amazon Web Services (AWS, created in 2006, still accounts for less than 10% of total revenue), is a retailer, selling products and services to consumers. The company went public in 1997. Its current10 market value is $700 billion.

In 1998, two graduate students from Stanford University, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, had the vision that the web site ranking algorithm they had designed while working on their thesis was a good business opportunity to disrupt Internet information access. At that time, the categorization of the web was done manually by Yahoo! (“Yet Another Hierarchical Officious Oracle”). Brin and Page extrapolated that, given how fast the web was developing, automating information access was the only way forward. Doing so, they literally invented what is now referred to as “search”. Yahoo!, the former star of Internet, badly disrupted by Google, never recovered. It ended being acquired by Verizon for $4.5 billion in 2017, most of the value coming from Yahoo’s participation in China-based Alibaba. Google offers useful intuitive and addictive services to consumers for free and sells its captive audience to advertisers, a typical media business model. Google, now Alphabet, is valued10 $817 billion

Mark Zuckerberg partnered with fellow Harvard College students and roomates to launch The Facebook website in 2004. He had the vision that the desire to share and communicate was a huge need for people and nobody was addressing this need through the internet. The business model is like Google’s. Facebook is now10 valued $545 billion.

We could go on and on, with the business cases of Tencent and Alibaba in China, Expedia and Priceline.com in the travel industry, Uber in the transportation market, Airbnb in the accommodation market, Spotify, the company which invented music streaming as a business… Airbnb, Spotify, and Uber are rumored to plan their IPO in 2018 or 2019.

These companies share with Apple the same business model: to leverage technology to reinvent or to disrupt a market; to go after a huge addressable market with reinvented rules; to build a platform, an ecosystem to preempt future competition; to go fast and adapt or even change business model whenever needed (to rotate in the start-up jargon), to think big and out of the box.

It is because they are digital companies that they grew so fast and became so big.

Technology companies meanwhile, with the notable exception of Apple, kept on their course. Some are in trouble, some are doing fine. In the investable “Digital Universe” carved out by Finaltis, an asset management company with a leading digital investment practice, there are only three technology companies (Microsoft #3, Samsung Electronics #8, Intel#10) in the top 10 market caps. The IBMs, Ciscos, Oracles and Dells of the world, have been pushed out of the top 10 and many have seen their relative weight decrease in the MSCI World index. To put it another way, the bulk of value creation of the last ten years has come from digital companies, not from technology companies. To illustrate that, we compared IBM (the champion of the mainframe technology era), “Wintel” (Intel and Microsoft, the two champions of the PC technology era) and the “GAFA” (the four digital champions; Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon). Each IT wave is bigger than the former one, which explains that the Wintel group eventually outgrew IBM in revenue. Yet the speed at which the GAFA group overcame both IBM and Wintel is unheard of, clearly showing that these companies play in a totally different league, the “digital league”.

2007, the tipping point for the Digital era

We saw that 2007 was the year when Apple officially declared itself a digital company and dropped “Computer” alongside its name.

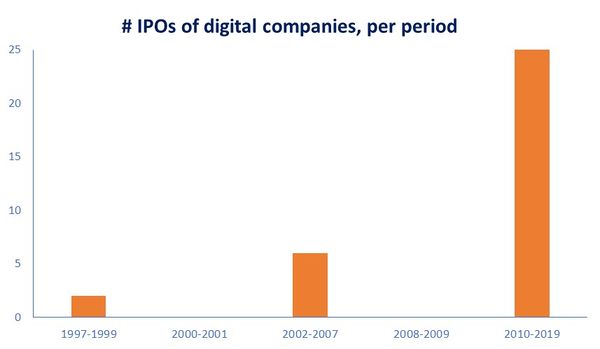

We looked at a basket of the most emblematic digital companies11 in the U.S., Europe, and Asia, and noted the date of their IPO (estimated for those already mentioned but not yet listed), retaining only those that have not been acquired. We assume that the date of an IPO is a good indication of a company achieving some maturity level and that viable companies ought to still be listed. The IPO opportunity window was for obvious reasons closed during the 2000-2001 and 2008-2009 periods. The graph below shows that 2007 indeed appears as a reasonable date to time the start of the digital era.

Retrospectively, 2007 is everything but a statistical coincidence. Back in the nineties, investor quickly realized to what extent Internet and the Web were a step change, huge uncharted business opportunities emerging. The Internet storm kept gaining power until it became a hurricane, a bubble in other words, which peaked in March 2000. With technology-based economic disruptions, it is often said that people are too optimistic with the timing and too pessimistic about the ultimate size of the disruption. This adage proved true for the Internet. At the end of the nineties, broadband Internet access and smartphones were still years away; only Silicon Valley folks enjoyed the luxury of several PCs at home and a broadband connection to Internet. A lot of entrepreneurs naively thought that the standard of living of average people was like theirs. It was not. What made the wildest dreams of the nineties a reality is a combination of (i) cheap broadband fixed access (ADSL for the most part), (ii) data-ready mobile networks (3G and 4G) economically available for the masses, (iii) affordable Internet-centric smartphones (the ultimate anytime-anywhere personal device). The combination of those three factors only became a reality on a large scale around 2008.

2018, stock markets finally stop classifying digital companies as “Tech”

In 1999, MSCI and S&P Dow Jones Indices, dominant providers of global indices for equity and bond markets, had just finally released for the first time an industry taxonomy, the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS). GICS consists of 11 sectors (Level 1), 24 industry groups (Level 2), 68 industries (Level 3) and 157 sub-industries (Level 4) into which S&P has categorized all major public companies. The Information Technology industry was acknowledged as important enough to deserve its own Level 1 sector.

When, in the back half of the nineties, “Internet companies” popped up from everywhere, there was no time to really think about what they truly were. As it was widely believed that Internet was a new industry, the choice by default was to categorize them as IT.

Many years later, it became widely accepted that Internet was a medium, a means to an end, not an industry, with the GICS classification in need of profound reshuffling. In November 2017, S&P Dow Jones and MSCI officially announced12 that most digital companies, previously classified as “Information Technology”, would be recategorize on the basis of their business model. Simply put, what is considered as “digital media” (Google, Facebook, Yelp, Tencent) shifts out of IT into a new sector, Communication Services, a blend of the old Telecom sector and Media (digital media and traditional media). Gaming is considered as another media, all media players competing for consumer leisure time; hence, it moves out of Consumer Discretionary into Communication Services. E-commerce market places, such as eBay or Alibaba, are to be considered as full e-commerce participants; hence, they go side by side with Amazon or Rakuten, into Consumer Discretionary. Why Apple is not planned to move into Consumer Discretionary or Visa and Mastercard into the Financials sector remains an open question: for now, all remain in the IT sector.

Even if a lot of smart investors are savvy enough to bet on future winners, whatever the GICS classification, one should not dismiss the formidable power of sectorial indices, which gave birth to sectorial trackers (low-cost funds tracking an index) and sectorial funds. Investors buying a “macro story” (as opposed to an “equity story”) invest in sectorial trackers or funds, which in turn invest in the constituents of the sectorial indices. These stocks rise, attracting even more inflows, more media attention, building up what is called a positive feedback loop. In that respect, GICS now differentiating digital and technology companies is a key factor not to be underestimated.

Technology and digital are different words because they are different worlds. As such, their economic impacts are different; likewise, analytical grids to be applied should differ as well. Let’s address two subjects we find quite telling to illustrate these differences: productivity as an analytical tool and societal issues to measure impact.

Where has productivity gone?

In her April 3, 2017 introductory speech at American Enterprise Institute, Christine Lagarde, IMF13 Managing Director, summarized what many consider an unexplained paradox. On the one hand, innovation seems to be moving “faster than ever, from driverless cars to robot lawyers to 3D-printed human organs”. On the other hand, “we can see technological breakthroughs everywhere except in the productivity statistics”14.

As she puts it: “Over the past decade, there have been sharp slowdowns in measured output per worker and total factor productivity, a well-accepted measure of innovation. In advanced economies, for example, productivity growth has dropped to 0.3 percent, down from a pre-crisis average of about 1 percent. This trend has also affected many emerging and developing countries, including China.”

We are not economists; we are investors. As such, we have been closely following technology innovation for several decades now, so we will try to bring our modest contribution to the debate. Instead of a macro top down approach, we retain bottom-up observation of the economic impact of the new digital giants and how it does or does not relate to productivity.

First, the often-repeated mantra that “technology is moving faster than ever” remains - at best - an assumption or a perception. As far as we can tell, not only is there no public research supporting this thesis, but the spectrum of diverging opinions on this issue is very wide. The innovation-skeptic camp is well illustrated by the famous book by Robert Gordon, “The Rise and Fall of American Growth”, in which it is argued that the 1850-1970 formidable period is a one-time event unlikely to repeat itself anytime soon. Can we really compare the impact of Internet and smartphones to the nearly doubling of life expectancy at birth (from less than 40 years in 1850 to more than 70 in 197015), the irruption of electricity, trains and cars, and the generalization of running water and electricity? The most enthusiastic, like Erik Brynjolfsson & Andrew McAfee, MIT economists and authors of the widely-quoted “The Second Machine Age”, think that everything accelerates. In the same vein, some say that we are at the very beginning of what they call the 4th Industrial Revolution (Steam Engine, Electricity, Computer making the first three). Others talk of “Technological Singularity”, a mythical tipping point when machines become more “intelligent” than humans and claim command, either reining in humans, as humans did with animals, or even “terminate” humans in the worst scenario.

Whenever “artificial intelligence” is said to make a breakthrough, it seems to crystallize our worst fears. I remember vividly, as a post-graduate visiting scientist at Carnegie Mellon University in the eighties, how people got both excited and fearful about artificial intelligence. The biggest fear at that time was that, the US being perceived as a declining power, Japan would take over the world. In 1982, when Japan's Ministry of International Trade and Industry announced its Fifth Generation Computer Systems initiative aimed at creating an "epoch-making computer with supercomputer-like performance and to provide a platform for future developments in artificial intelligence”, everybody overreacted. Alas, the project failed miserably. In the mid-eighties, the enthusiasm for AI ebbed away, at which point we entered in the so-called “AI Winter” period which ended only a few years ago. Today, among our worst fears, are inequality, digital divide and unemployment. Unsurprisingly, a lot of self-proclaimed AI gurus and futurologists forecast a society with millions of robots, taking over most human jobs and driving our cars and trucks, triggering a massive underemployment era.

As investors specialized in technology and digital investments, our experience taught us the need to remain simultaneously at the forefront of technology or technology-led disruptions, trying to figure out what a new technology can or can’t do, and to look deeply into business models as much as technology, and last but definitely not least, to be extremely picky with timing.

We are very impressed by the progress of machine learning, which is the part of “artificial intelligence” where a disruption has indeed occurred, and fascinated to see that machine learning usage is spreading very fast, to the point we may at some point stop talking about machine learning to call it “advanced software”. In a sense, machine learning is nothing but advanced analytics. This is about helping decision makers with predictive analytics: what could happen or what people should do rather than given a nice-looking description of what has already happened. Established software vendors have a significant edge as they can get leverage from the tons of data they control, whereas a startup needs to start from scratch. This could by and large explain why we do not – yet? - see a startup disrupting the software landscape, an exact opposite of the cloud disruption that gave birth to Salesforce, Workday inter alii. The same observation applies to Internet where Google, Facebook, Amazon, Tencent, Alibaba are all in a rush to leverage machine learning; with no real impact on their respective market shares, so far. This calls for something evolutionary, not disruptive.

Ultimately, machine learning will give machines the ability to analyze their environment through cameras and radars, to move among humans harmlessly, opening a whole range of new markets such as autonomous cars or trucks or planes, smart drones, … That said, we think that a wide deployment of robots, drones and autonomous cars in our homes, in the streets and in the air will take much longer than the most enthusiasts think, for many reasons.

The second point we would like to make is that, as we explained, most of the innovation goes into the creation of digital, not technology companies. The ambition, the energy and the enthusiasm of entrepreneurs is channeled into reinventing or disrupting industries, competing against established companies, not working with them, through productivity increases for example. The friendly supplier-to-customer relationship (Dell, IBM or SAP never compete against their customers) is being replaced by a more confrontational one. With nearly 118 million subscribers, Netflix plans to invest some $8 billion in 2018 to create or to buy its own content, competing against media giants such as Disney, Sony, Time Warner, Vivendi. The first thing Amazon did when it acquired Kiva, an advanced robot company for automating consumer package preparation, in 2012 was to cut out competitors from Kiva’s technology. It worked great. As there was no equivalent on the market to replace Kiva, retailers scrambled to find an alternative; and Amazon strengthened again its lead.

Digital transformation is all about improving customer experience, being more transparent and letting consumers be in full control anytime, anywhere. The pendulum has gone from back office productivity-driven investments to front-office sales-driven ones. This is not about being more productive, this is about being more competitive and serving customers better. Winning millennials is the goal: they make up the most demanding population in terms of digital customer experience; and their share of markets can only get bigger, the older and the more affluent they get. For many companies, digital transformation means that consumers now spend a much larger portion of their buying process time surfing through the web, scouting social networks, getting pieces of advices from their “digital friends” or peers through forums and blogs. In the end, customers are more willing to share, and become more informed, savvier consumers. Productivity does not measure that kind of change.

With Internet, advertising has shifted from press and radio to digital, a space dominated by Google and Facebook in developed countries. The total market of corporate advertising has not grown in the process, but the way marketing budgets are spent has changed. Is advertising spending more productive in the digital era? That remains to be seen.

The Internet era translated into a slew of new digital intermediaries, e.g. Zillow in the US. real estate market, Priceline.com, Expedia for travel, eBay or auboncoin.com for consumer-to-consumer trade, BlaBlaCar for carpooling, Just Eat or Deliveroo for restaurant take-out delivery… If consumers value these new services, it also means that restaurants must now deal with new distribution channels.

To put it more bluntly, the productivity metric has mostly become irrelevant in the digital age. The “productivity paradox” is immediately explained - there is no paradox, simply a wrong question - once one reckons we are in a digital era, not a new technology one. Innovation and value creation need to be measured differently, possibly by looking at the degree of economic disruption, the speed of emergence of new digital invaders in a given industry and how the information gathering process from the buyers changed the buying process as a whole.

The second dimension we suggest we look into is the impact of digital within and upon our society.

Digital Inc. vs Country Inc.

Digital companies, led by the FANG group (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google), have reached a huge scale at a tremendous pace. Yet the fascination and admiration about their amazing success has progressively morphed into fear and mistrust. Societal issues have emerged and there are a lot of them.

Should social networks be held liable for the content posted on their sites? How to define and who should decide what is considered appropriate or offensive content? To what extent should digital companies be allowed to accumulate data on Internet users? What is digital privacy, how should it be protected? What about the right to be forgotten? Why should non-US countries let the NSA siphon out their own data without warning? Who is liable in case of a cybersecurity hack? How will autonomous cars “decide” who to save first if an accident is deemed impossible to avoid and sacrifices are unavoidable? Should European countries let digital companies pay lower or no tax at all because their work relies on intellectual property to be paid for under a different jurisdiction? To what extent foreign states or interest groups can build “fake news” and trick the algorithms that decide which information will be presented on our screens? How do anti-trust authorities can adapt to the new digital landscape? Have some digital companies become monopolies that should be closely watched, more regulated or maybe even dismantled? All are legitimate issues and the pressure on governments to do something is rising.

One core issue is that regulation, which has evolved over time to rule the pre-digital era, has often been made obsolete in the digital age. Regulation changes rarely follow a smooth path but most frequently leapfrog as the interests are alternatively taken into consideration by regulatory bodies; this is even more so when disruptive new entrants enter the game and trigger reactions to their innovative approaches.

Difference of speed is another issue. Digital start-ups move as fast as possible in a land-grab strategy. Technology is not a barrier to entry, the “platform” is: the more subscribers, the higher the value of the platform; the larger the platform, the more attractive it is to new subscribers, in a perfect virtuous cycle. Uber has not invented any new technology; it was just faster than its competition. Uber game plan is nothing but building leading platforms in all the countries where it operates so that it can crush its slower competitors. When it fails, like in China where Didi won the battle, Uber exits the market. On the other side, regulators move at their own – slower - speed.

Lack of knowledge about the other side is another issue. Regulators often know little about digital transformation. Digital entrepreneurs know little about regulation. The latter somehow assume that the problem will be solved afterwards. They prioritize as follows: (i) build a community with a minimum viable product, (ii) iterate in a data-centric approach to improve the product until the community has become big enough, (iii) build a business plan, (iv) monetize, (v) scale up. At some point, the two worlds need to synchronize. It is far from easy, nor it is natural to do so, and it often turns quickly to a confrontational tone.

Sometimes, the confrontation gets nasty, with Uber being indisputably one of the most abrasive in that respect. Until recently, Uber had preferred confrontation to discussion, as it was engraved in its DNA by its co-founder and CEO Travis Kralanick. Over time, the board came to realize that a systematic confrontational approach with everybody, not just regulators but also Uber’s own drivers, was counterproductive and triggered a change of top management. The pressure from early private equity investors, in need of an exit, was also rising: Uber needed to go public but it was nothing near IPO-ready. Travis Kralanick was eventually pushed out and the former CEO of Expedia, Dara Khosrowshahi was called in. He is known as both a “doer”, a “listener” and a good negotiator. His first new corporate rule was “We do the right thing. Period.” We can already see a humbler, more “human” Uber through different initiatives set by Dara Khosrowshahi.

Sometimes, the confrontation evaporates because the interests of the digital invader have changed, as is often the case for corporate tax-related issues.

For many years, local U.S. states have been engaged in a legal fight to make Amazon pay taxes like all traditional retailers do - i.e. based on their local presence - even if Amazon had no local warehouses. Amazon’s strategy to let legal cases drag for ages thanks to “legal filibustering” techniques, proved to be pretty successful. The pressure built up for sure. However, more importantly, it became Amazon’s interest to densify considerably its warehouse network to keep its ultimate promise: one-hour deliveries in the largest U.S. cities. One-hour delivery is a formidable barrier to entry for its competition; what’s more, it increases the available addressable market. One-hour delivery smashes the main reason to go to a brick-and-mortar outlet away. The same applies to Europe. At this juncture, Amazon started to change its stance on tax issues and made peace with local U.S. states one by one and increasingly with European countries.

Airbnb faces a similar situation: there is a strong backlash against its fast development. At first, Airbnb is welcome. It brings more tourists, especially those who cannot afford hotels. It increases the purchasing power of owners who can share their home on a part-time basis making money in the process. Yet too much Airbnb supply, too fast, turns Airbnb in a business per se, no longer a sharing activity. When it translates into unwanted real estate inflation, related social issues appear. Municipalities push harder and harder to make Airbnb pay local taxes and to level the playing field between Airbnb and hotels. Some cities have gone as far as making Airbnb illegal, even if such a measure is hardly enforceable.

Airbnb’s answer mimics Amazon’s: they wait and see until the pressure is too high to be ignored. It seems Airbnb changed its stance recently, negotiating, city by city, trading taxes against full legal recognition, usually with a message which goes like this: “please, update your rules and let us operate legally in your city, and we will agree to pay relevant taxes”.

There is yet another unspoken factor, of strategic nature: the regulatory and anti-trust threat. Peter Thiel, the founder of PayPal, and president of Clarium Capital Management (a $3 billion hedge fund), a board member and early investor in Facebook, describes this in "Zero To One", his book about highly disruptive ambitious companies, that seek to reinvent the world, not just improve a process or a technology. These companies target very large addressable markets they can dominate to extract most of the value. The Silicon Valley often refers to these companies as “platform companies”, which is nothing but a politically-correct word for “monopolies”. Peter Thiel rightfully reminds us that monopolistic companies "lie" to dodge unsolicited attention on the part of regulatory and anti-trust authorities; companies facing strong competitive pressures also “lie” to minimize the impact on their business. As an example, Peter Thiel explains why Google prefers to describe itself as a technology company, one among many others, rather than one reaping the benefits of a 90%+ market share in Europe, dominating the sensitive search engine market. Doing so, Google successfully managed to postpone anti-trust threats in Europe by several years, and used the respite to become bigger and to, build ever higher barriers to entry, rushing towards what they hope would be a point of no return before potential serious anti-trust backlashes. Google’s dodge-and-run strategy is far from being unique: think about Android and its 85% worldwide market share in smartphones IOSs…

Facebook does the same. Facebook’s mantra, “Bringing the world closer together”, stayed relevant for a long time: Facebook users could share anything they cared about and their “friends” would be notified. Facing a “massive threat” from Twitter back in 2012, Facebook actively courted journalists and adjusted its News Feed channel to fully incorporate news. By the end of 2013, Facebook had doubled its share of traffic to news sites, actively pushing Twitter towards decline. By mid- 2015, Facebook had surpassed Google in referring readers to publisher sites and was now referring 13 times as many readers to news publishers as Twitter16. That year, Facebook launched Instant Articles, offering publishers the opportunity to publish directly on the platform. The issue is that, by doing so, Facebook implicitly switched on the media side, precisely what it has always wanted to avoid…

Algorithms take care of filtering and selecting the contents a subscriber is deemed likely to be interested in based on past tastes and biases. Rapidly, it appeared that the system worked as a “filter bubble”: the algorithms not only gave the user what (s)he wanted to read, but also tended to favor a reflexive loop leading to the most extreme opinions. The inner workings of such algorithms combined with badly intentioned people, for example during the 2016 U.S. presidential elections, end up with troublesome “fake news”. It is all too plausible that Russians, with a limited budget, were in a position to lean on the ballot. All of a sudden, the formidable weight of Facebook seems to put democracy at risk: the voices of those requesting Facebook to be regulated like a media company become stronger and stronger in the US. One can easily understand why Facebook always preferred to be called a technology company…

Extraterritoriality of law enforcement of electronic data is another serious issue. The 1986 Stored Communication Act (SCA) is a law that compels “Internet Service Providers” to disclose content at the request of the U.S. government, whatever the location of data centers. From a European standpoint, in a digital age where all Internet giants are US-based, the SCA introduced an information asymmetry between Europe and the U.S., and clearly violates the sovereignty of European countries. European authorities have yet to elaborate an adequate response. A positive outcome may originate from U.S. “Internet Service Providers” themselves; they rightly view this as a threat to their non-US business operations. In 2013, Microsoft took the front seat among Internet providers and challenged a warrant issued by law enforcement to turn over emails from a target account stored in Ireland: Microsoft made the point that an American company could not be compelled to produce data stored in servers outside the U.S. The case went all the way through the US legal system, up to the Supreme Court, whose decision is pending.

The platform effect we talked about yields oligopolies, if not monopolies. Investors love it because it means high barriers to entry and fat margins. Google Search’s market share was estimated at 75% on a global basis17. If we leave Chinese Baidu and Russian Yandex search engines aside, the combined competitors’ market shares (Microsoft’s Bing, Yahoo!, Ask, DuckDuckGo, Dogpile, AOL) stand at 14%. If we focus on mobile only, Google reaches 93%, leaving a mere 4% to the above-mentioned group of so-called competitors... Russia, to some extent, and China alone have managed to withstand Google.

In developed markets, Google and Facebook suck up most of Internet traffic thanks to their multiple brands: Search, Gmail and YouTube for Google, Facebook, Messenger, Instagram and WhatsApp for Facebook. As a result, the two companies are estimated to command 84% of all online advertising spent in 2017 (ex-China)18.

If Netflix’s growth continues unabated, Netflix will end up controlling the media market.

Depending on data sources, Amazon is estimated to own between 34% and 42% of the U.S e-commerce market in 2017. Fortune forecasts that Amazon could make up to 50% of all U.S. e-commerce by 202119. Bar Walmart, standing up against such a behemoth in a scale-driven business will be no easy task.

If the trend continues – and why should it not? - anti-trust actions are likely to multiply. In June 2017, the European Commission fined Google €2.42 billion for “abusing dominance as search engine giving illegal advantage to own comparison shopping service”. Google obviously appealed, starting a legal marathon. The European Commission is also investigating other dimensions of Google’s businesses, including whether Google unduly imposes the installation of its own apps on Android devices.

The bottom line is that the confrontation between digital companies and regulatory & political authorities has just begun, turning in some cases to a direct power struggle. Only time will tell who wins. Each “contender” will need to learn how to deal with its counterpart.

In conclusion

Digital transformation is a deep and structural transformation of business and organizational activities on a global basis to fully leverage the changes and opportunities digital technologies enable. Not only will it shape the way our society functions in the future, but its full impact has yet to be fully analyzed and understood.

With so much at stake, it is important to move beyond the usual clichés about technology to understand what the true agents of change are. Having closely tracked the space for many years as investors, we came to realize to what extent the right use of Technology and Digital is essential to correctly analyze what digital transformation is about.

Words do matter indeed. We believe that making a clear difference between Technology and Digital goes beyond semantics and offers a decisive edge towards getting to grips with the ground-shaking impacts of the fast-paced emerging or yet to emerge digitalization trends. Once done so, a lot of issues or so-called paradoxes related to digital transformation become easier to solve and a different analysis framework emerges.

Benoît Flamant

Head of Digital Investments

Finaltis

(1) The amazing success of Amazon’s “intelligent speaker” Echo is an excellent illustration of new usage enabled by a voice-based user interface

(2) Elon Musk, always at the forefront of innovation, has recently formed Neuralink in that field; source: https://www.theverge.com/2017/3/27/15077864/elon-musk-neuralink-brain-computer-interface-ai-cyborgs

(3) Do It Yourself

(4) As of Q4 2017, source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/271496/global-market-share-held-by-smartphone-vendors-since-4th-quarter-2009/

(5) Before seeing a return to growth in 2015, the global recording industry lost nearly 40% in revenues from 1999 to 2014, source: IFPI Global Music Report 2017

(6) Internal memo from Stephen Elop, then CEO of Nokia, source: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/blog/2011/feb/09/nokia-burning-platform-memo-elop

(7) Source: https://www.devost.net/2009/06/18/23-devices-my-iphone-has-replaced/

(8) As of January 31, 2018, source: Bloomberg

(9) As of January 31, 2018, source: Bloomberg

(10) Source: Wikipedia

(11) Airbnb, Alibaba, Alphabet, Amadeus, Amazon, Baidu, Criteo, Ctrip, Expedia, Facebook, GrubHub, Just Eat, Mercadolibre, Pandora Media, PayPal, Priceline, Rocket Internet, Rovio, Sabre, Sina, Snap, Spotifiy, Tencent, Tesla, Tripadvisor, Trivago, Uber, Weibo, Worldline, Yelp, Zalando, Zillo, Zynga (33 companies)

(12) Source: https://www.msci.com/documents/10199/d56e739d-4455-4bc1-afdd-d738c2ce5a05

(13) International Monetary Fund

(14) Source: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2017/04/03/sp040317-reinvigorating-productivity-growth

(15) Source: https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy

(16) Source: https://www.wired.com/story/inside-facebook-mark-zuckerberg-2-years-of-hell/amp

(17) Source: www.netmarketshare.com

(18) Source: https://www.groupm.com/news/groupm-global-ad-investment-will-grow-43-in-2018-six-countries-to-drive-68-of-incremental-investment

(19) Source: http://fortune.com/2017/04/10/amazon-retail/