Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Social networks have become areas of social interaction among young people where they create a profile to relate with others. The way this population uses social networks has an impact on their socialization as well as the emotional and affective aspects of their development. The purpose of this investigation was to analyze how Facebook is used by young people to communicate among themselves and the experiences they gain from it. On the one hand, while teenagers claim to know the risks, they admit to accepting strangers as friends and to sharing large amounts of true data about their private lives. For this reason, it is necessary to understand the media and digital phenomenon that the youth are living through. Although they are legally prohibited from using Facebook until they are 13, the number of underage users of this social network is growing, without any restraint from parents or schools. This investigation compares the use of Facebook by youth in Colombia and Spain by using the content analysis and interview techniques. In Colombia 100 Facebook profiles were analyzed and 20 interviews carried out with students between 12- and 15-years-old attending the Institución Educativa Distrital Técnico Internacional school in Bogotá. In Spain, 100 Facebook profiles were analyzed and 20 interviews held with students of the same age group attending various secondary schools in Andalusia.

1. Introduction

Since their creation, social networks such as Facebook, MySpace, Cyworld, Bebo or Twitter have attracted millions of users (Foon-Hew, 2011), many of whom have integrated these websites in their daily activities (Boyd, 2007; Piscitelli, 2010). Schwarz (2011) suggests that the youth are moving away from the dominance of telephones and face-to-face interaction and prefer communication based on text, especially messaging, as a method of instant communication. Social networks offer a new way to communicate, to build relationships and create communities (Varas-Rojas, 2009).

Haythrnthwaite (2005) argues that what makes social networks different is not that they allow young people to meet strangers but that they enable users to articulate their social networks and make them visible thus leading to connections between individuals (Timmis, 2012).

1.1. Research background on social networks

Most research on social networks has focused on how individuals present themselves and create friendships through the online networks, their structure and privacy.

• Studies on how individuals present themselves and develop friendships through the online networks: as in other online contexts in which individuals are able to consciously construct a representation of themselves, social networks constitute an important research context for studies of the management processes of self-presentation and the development of friendships, as studied by Junco (2012), McAndrew & Jeong (2012), Ross, Orr & al. (2009) and Moore & McElroy (2012). Although, most sites invite users to create exact representations of themselves, participants usually do so at different stages (Marwick, 2005; Ong, Ang & al. 2011). Marwick found that users of social networks handle complex strategies when negotiating their real or «genuine» identities.

• Studies on the structure of social networks: researchers of social networks have also been interested in the structure of friendship networks. Skog (2005) argued that members of social networks are not passive but participate in the social evolution of the social network. Likewise, studies have been developed around the motivations for joining certain communities (Backstrom, Hottenlocher & al., 2006). Liu, Maes & Davenport (2006) stated that connections between friends are not the only network worthy of research. They examine how people’s interests (music, books, movies, etc.) constitute an alternative network structure to what they call the «likes networks». And Soep (2012: 98) points out that «the youth have developed new codes of behavior and created models to support production beyond publication», and Gonzales & Hancock (2011) study the effects of Facebook use.

• Studies related to privacy: The coverage of mass social media in social networks has focused on issues of privacy, particularly on the safety of younger users (Flores, 2009: 80), cyberbullying and other possible risks (Calvete, Oru & al., 2010; Law, Shapka & Olson, 2010; Hinduja & Patchin, 2008; McBride, 2011).

In one of the first academic studies on privacy and social networking sites, Gross & Acquisti (2005) analyzed 4,000 Facebook profiles and described the potential threats to privacy arising from the personal information contained on the site.

Stutzman (2006), in his study of surveys of Facebook users, described the «privacy paradox» that occurs when teenagers are not aware of the public nature of the Internet. Jagatic, Johnson & al. (2007) used data from open-access profiles of Facebook to develop an «identity theft». Data from this study provide a more optimistic perspective and suggest that teenagers are aware of the potential threats to privacy online. The research also concludes that of the teenagers with open profiles46% admitted to including at least some false data about themselves (Jagatic, Johnson & al., 2007: 97).

Privacy is also an issue in users’ ability to control and manage their identities. Social networks are not a panacea. Preibusch, Hoser & al. (2007) argued that privacy options offered by social networks do not provide users with the flexibility they need.

In addition to these issues, a growing number of studies address aspects such as race and ethnicity (Byrne 2007), religion (Nyland & Near, 2007), how sexuality is affected by social networks (Hjorth & Kim, 2005) and the use that certain segments of the population make of social networks, as in the case of children (Valcke, De-Wever & al., 2011), teenagers (Pumper & Moreno, 2012; Moreau, Roustit & al., Chauchaud & Chabrol, 2012; Aydm & Volkan-San, 2011; Bernicot, Volckaert-Legrier & al., 2012; Mazur & Richards, 2011) and digital natives (Ng, 2012).

2. Materials and methods

This research used a mixed methodology with qualitative (in-depth interviews) and quantitative (content analysis) techniques. It is a comparative study of teenagers in Colombia and Spain comprising 100 Facebook profiles and 20 in-depth interviews of 12- to 15-years-olds in Colombia and Spain. In Colombia, the study centered on teenagers at the «Institución Educativa Distrito Técnico Internacional», school in Bogotá. In Spain, the survey focus was boys and girls at various schools in Andalusia (Los Olivos, Torre Atalaya, El Palmeral, El Jaroso and Rey Alabez). The selection of schools was random. We analyzed the Facebook profile of those teenagers who had agreed to participate in our research, and from among these we randomly selected students for the in-depth interviews.

A template was used for content analysis of the Facebook profiles containing research variables and items such as the frequency of sign-ups, the language used, the number of pictures and their descriptions, and the number of friends and type of personal data (hobbies, likes, relationships, etc.). In relation to the in-depth interviews, the topics covered were the uses of and gratification gained from social networks and the explanation of specific aspects relating to their profiles. The period of analysis was from May 2011 to May 2012. The study examples do not include names or pictures because all participants are minors.

3. Analysis and results

3.1. The case of Colombian teenagers

a) How do they present themselves on Facebook?

For those teenagers studied for this research, having a Facebook a profile means managing his/her personality. Creating a Facebook profile and assigning content to certain fields already pre-established in the interface is the act of creation of a being who moves in a digital environment. Although it is about presenting themselves as they are, there is also room to present themselves as the wanted to be seen. Teenagers have a clear notion of how they want to present themselves on social networks which depends on something very important at this stage of life: their socialization, both real and virtual.

In this regard, our study demonstrated how teenagers adopt a name other than their own on Facebook to describe attributes of their identity. Of the 100 profiles studied, 45 teenagers assumed a name that had little or no relation to their real names. For these teenagers, the resonance of their name is very important. One Colombian boy interviewed explains that «my name is…because it looks cool…also because I listen to Ska and Punk»; similarly another youngster justifies altering his name «on Facebook by always writing it with the C and not the E to make it different. And the name Tanz means that I belong to a group of 6 friends from my school but we also have that name on Facebook».

b) Profile pictures: makeup and changes in pixels

Teenagers spend more time working on pictures of themselves to post on the social network than anything else; they think about their image, design it, create it, produce it, edit it... and send it. However, in their images they stand alone. The «Profile photos» of the 100 Facebook profiles studied show the teenagers appearing by themselves, and the photograph is normally taken using a mirror.

A teenager explains how she built most of her profile pictures in which she usually appears alone: «Taking pictures in front of the mirror is not a fad, it is just easier because you know how they are going to look… for this reason I take many pictures of myself in the bathroom. There are photos that I do not like and so I do not upload them… Besides I almost always modify the photos I post… A lot of boys like my pictures… I think that is why I get so many friend requests».

The number of «Profile pictures» in the 100 Facebook profiles studied amounts to 2,612, an average of 26 per teenager, with 1 photo published in each profile. It is also interesting to note how teenage girls tend to have more pictures in their «Profile pictures» albums than boys.

c) Profile information

The «information» link in a Facebook profile contains an «About me» field. An analysis of the 100 profiles found that 33 had published personal information via this link, but even more interesting was that although the interface only allows users to include information as text, several of the teenagers had deployed their keyboard skills to copy and paste to create images.

They publish their dates of birth, though not entirely truthfully (they tend to backdate), add their home addresses and the schools where they study, their favorite music, movies, television programs and activities and interests. However, they do not disclose their religious beliefs, political affiliations or name their favorite sports or books.

So, as in friendship, love is now mediated by technology. For these teenagers, a relationship presented on Facebook is a true reflection of a relationship that exists in real life. Of the 100 Facebook profiles studied, 22 posted information related to sentimental relationships with other users. In 6 cases, the teenagers described themselves as married which is certainly not true.

d) How do they interact?

For teenagers, having friends on Facebook means more than having a contact list; it is the management of friendships in another scenario where the image is the main link. This is confirmed, for example, by one Colombian youngsters interviewed, aged 13, who explains that «for me to add someone as my friend is because he has a nice picture, must be good looking or cute… (laughs) and has friends in common with me, because I know that if any of my friends know him, he is not dangerous. However, if someone asks me to add him as a friend and we do not have friends in common, I look very closely at the pictures and if he is cute I add him».

For these young people, having a friend on Facebook does not necessarily mean meeting face to face. Several of the teenagers interviewed talked to «Facebook friends» who they had never seen. The number of friends on the 100 Facebook profiles studied totals 34,730. But, how do they get to have so many friends in their profiles? They use two criteria to add unknowns as friends: in their pictures they must be «good looking or cute» and must have friends in common. However, the former may be sufficient to accept a request to be a friend.

The decision whether to accept or reject a request to be a friend on Facebook is taken very quickly. These teenagers did not take longer than 20 seconds to accept a request to be a friend and rejected very few. Unlike the real world, in which teens interact with adults such as their teachers, parents, authority figures, etc., adults are forbidden entry to their Facebook profiles, in fact only 5 teenagers had added their parents or other relatives as friends; 2 had even added their teachers but most say they do not want their parents to find out what is in their profiles.

The conversations of teenagers on Facebook center on their image. There are few posts that have anything to do with subjects other than image. Pictures are the starting point of conversations and relationships. Most of the texts relating to images were very short compared to the large numbers of photographs. The reasons are explained by one of the girls interviewed who says that «when I post a picture and nobody comments on it, I delete it: why leave something there that nobody cares about! For instance, the pictures with most comments are the latest ones I have uploaded, so I am more and less discovering what my friends like to see… well, I think they are the sexy ones». The number of photos in the 100 Facebook profiles is11,426, an average of 114 per user, with 26 published in each profile.

The image has also become a way to express affection: take a picture and modify it, upload it to Facebook and share it. They call this action a «zing», derived from the English «sign», as a signature added to a photo uploaded to Facebook, with a message sent to a friend.

Teenagers communicate on Facebook using new codes of writing that ignore conventional grammar and spelling rules, yet they type quickly and adopt the digital aesthetic. Their way of writing seems to be capricious; new ways of writing emerge in the form of «text-images» created from the keyboard, in which the letters become part of the image that means something entirely different from the linguistic meaning.

e) Facebook groups: new ways of belonging

For Colombian teenagers, belonging to a Facebook group is not just feeling that they are part of something, it is having a shared image that shelters and protects its members, allowing them to act as an «I» group. Being part of a group is belonging to a real community.

3.2. Spanish teenagers

a) How do they present themselves on Facebook?

The vast majority (95%) of the Spanish youngsters sampled used their real names in their Facebook profiles. However, when interviewed about this, half of them agreed that it was dangerous to use the real name, and one of them said: «My mother always tells me that I should not give any true data, because anyone with bad intentions could find me». Therefore, the theory holds but they forget to put it into practice.

Most teenagers in our sample have all their profile content and wall open to whoever wants to read it, and only a small group limits access. When asked about this in interviews, most responded that they were unaware of the privacy option they had activated. In this sense, one of the girls stated that «nothing happens from sharing on Facebook. All of my friends do it. Because we are so many, someone is going to be interested in what I do or say». Therefore, the fact that it is common among her colleagues to share is interpreted by this girl as meaning an absence of danger.

On the other hand, when stating their age they are not so honest. Almost none gives their true age. Facebook has established a minimum age of 13 to open an account on this social network, but teenagers simply get around this by declaring they were born a few years before their actual birth date. Most teenagers analyzed use the wall to share links, pictures and to post and receive comments on photos of friends. However, with one exception, wall activity is not very common, with an average of only three or four posts per month. This was proved during profile analysis and also in interviews with these teenagers who said they posting less than five comments per month, and usually from home.

b) Teenagers’ profile picture and photos on the social network

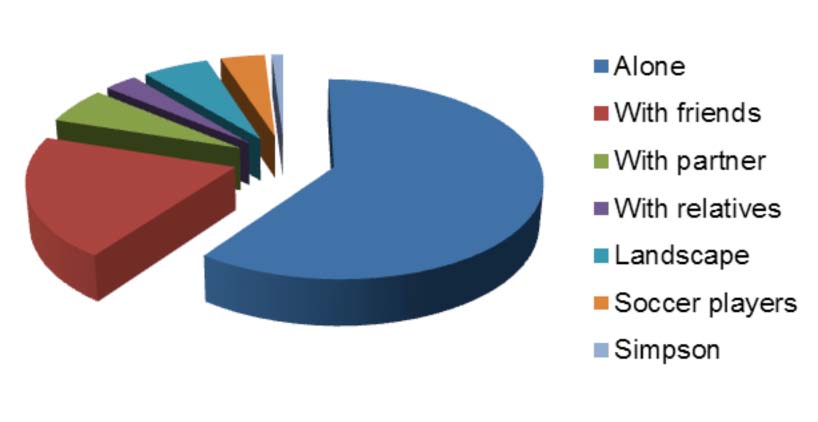

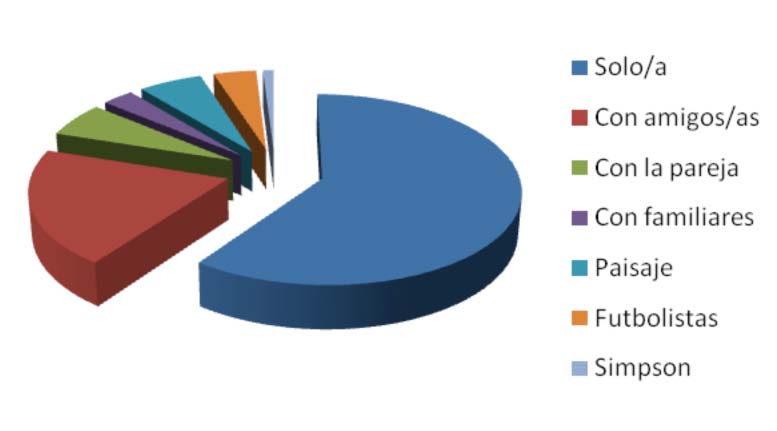

The Spanish teenagers, like their Colombian counterparts, make great use of photographs in their profiles. Of these 78% upload pictures without modification, 13% design photos, 6% use retouched photos and only 3% have no profile picture. The profile photos usually show the protagonist alone (60%), or with friends (20%). The remaining 20% is divided between photos with a partner (6%), with relatives (3%), of landscapes (6%), famous personalities like soccer players (4%) or fictional characters like The Simpsons (1%).

The pictures that teenagers upload to their profiles usually have them posing (sometimes very unnaturally). The feeling is that they are imitating their TV or media idols, and retouched or designed pictures seem to further highlight this desire to emulate their media leaders. One of the Spanish teenagers interviewed recognized that there is some competition between friends to see who can upload the most appealing, controversial or original photo.

The number of pictures per profile («Profile Pictures») ranges from one to 251. The average number of pictures per profile is 23. Curiously, as also happens in Colombia, girls have more photos in their profiles than boys.

The average number of photos in each case is considerably higher: 168. Two teenage girls have 1,116 and 1,184 photos respectively. Something similar happens with the number of albums, ranging from none to 32, with the average being 5.4.

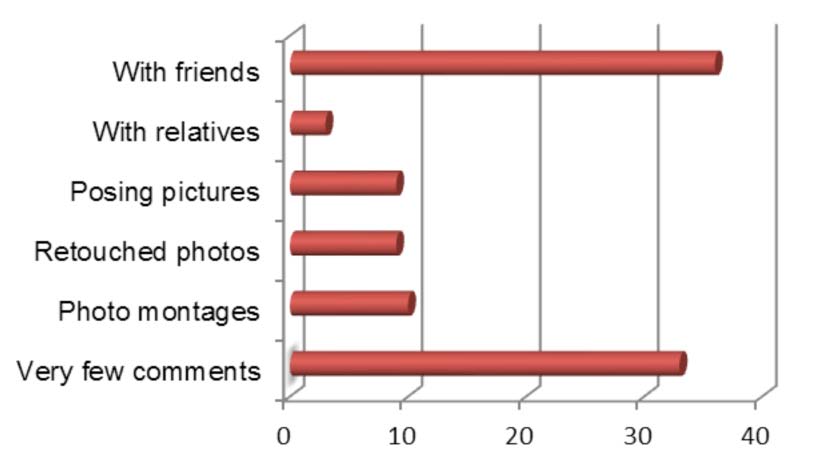

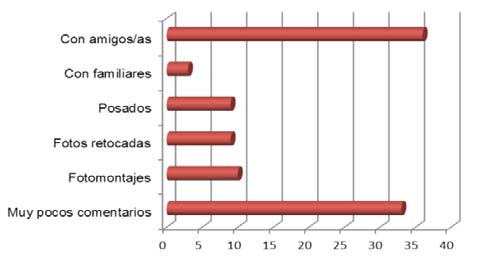

The average for photo sharing is also high. One teenager shared up to 817 pictures, while the average is 120 photos shared per teenager. Of these pictures, the most widely discussed are those taken with friends (36%), far ahead of photo-montages (10%), posed and retouched photos (both 9%), and those taken with relatives (3%). Therefore, friends of the teenager often comment on pictures in which they appear or on pictures of people they know. Photos that have been retouched or come in montage form also seem to arouse their interest.

c) Profile information

We observed that 84% of teenagers in the sample did not indicate in their profile which languages they speak. Curiously, those who did so speak more than one language: 9% declared that they speak Spanish, English and French, 6% speak Spanish and English and 1% English, French, Spanish and Latin.

Philosophy, religion and politics are of no particular interest to teenagers. In the case of philosophy and religion, only 12% said they were Catholic, and 7% posted sayings by philosophers or famous people in their profiles. Only 2% named a political party with which they sympathize. Teenagers do not tend to include a description of themselves in their profile («About me») and those that do add phrases like «I like going out with my friends», «I am a shy guy, but charming», or incorporate famous sayings or express the greatest joy because they feel understood by their partner. Texts are written in the abbreviated style that usually omits vowels (spelling rules ignored). In no case did we find «text-images» similar to those produced by the teenagers in Colombia.

Three quarters of the boys and girls sampled failed to mention their sentimental status. Of those that did, 12% said they were single, 9% said they were in a relationship, 3% «engaged» and 1% said they were married (obviously not true). One the teenager interviewed justified why he never provides true data: «I say that I live in another place, I make up my data… even my name.» He says that having a false identity is not a problem because «I use a name my friends know so they know right away who I am». Nearly all the teenagers (98%) decline to give a contact phone number on Facebook while 80% give an email address which in most cases is via Hotmail.

d) How do they interact?

Teenagers do not use Facebook frequently or on a daily basis. They usually post three or four times per month. Similarly the average number of friends is quite low, at 202. In the Spanish sample one boy had as many as 559 friends, while another boy had only 3. Therefore, it can be deduced that these teens are only just beginning to interact with social networks and still restrict themselves to their closest circles of friends.

e) Groups and applications

Spanish teenagers do not usually participate in groups. Over 80% are not members of a group and those who do, participate on average 3.8 times per month. However, they make greater use of applications, with each teenager using an average of 2 applications, mainly games such as «Aquarium», «Pet Shop City», «Sims Social» and «Dragon City».

f) Teenagers’ likes

Teenagers do not generally justify their likes although soccer registered highly (54% of profiles listed soccer as their favorite sport); 39% of teenagers do not specify a favorite sport. In cases in which they mentioned sports, soccer, tennis, volleyball, swimming, basketball, paintball, paddle tennis and ballet are among the favorites. The music that teenagers like includes Lady Gaga, Justin Bieiber, David Guetta, Shakira, Jennifer Lopez, the Jonas Brothers, Michael Jackson, Beyonce and Selena Gomez. Favorite films are «Toy Story», «Tres metros sobre el cielo», «Twilight», «High School Musical», «Avatar» and «Harry Potter». The television programs named among their likes are usually comedies or «top trending» series such as «Tonterías las justas», «El intermedio», «El hormiguero» or «El club de la comedia»; and contests like «Tú sí que vales» or «Fama»; and series such as «El barco», «El internado» or «Friends».

4. Discussion and conclusions

Both in Colombia and Spain, the majority of teenagers between 12- and 15-years-old use Facebook to interact with their friends. Facebook has become a socialization medium as important, if not more so, than the other social networks.

In both countries, teenagers reveal their need to belong to a network and to present themselves on it in the most original way possible (or, at least, in a way they deem to be original). One such way is to adopt a personalized language in their communications that defies conventional spelling rules. Furthermore in Colombia, the use of «text-images» (images created from text) was common. This manifestation of supposed originality is also evident in their photographs. The teenagers sampled in Spain and Colombia competed with each other to upload pictures that would attract their partner’s attention: posing or making suggestive gestures, retouching images, montages.

Most teenagers are over-exposed on the social networks, as shown by averages of114.6 pictures per person of the studied sample in Colombia and 168 photos per person in Spain. In the individual «Profile pictures» the average is 26.1 photos in Colombia and 23 in Spain.

But this over-exposure goes beyond pictures. Ninety-five per cent of Spanish teenagers use their real names in their Facebook profiles, while only 55% do so in Colombia. Hardly anyone expresses affiliation to a political party or religion, but a substantial group has no problem in declaring their sentimental status. Interestingly, both in Colombia and Spain some teenagers said they were «married» when this was obviously not true.

Another example of overexposure is found in the contact information. The most common indicator is an email address. However, in Spain, two teenagers gave their mobile phone numbers. But what could be even more dangerous is the fact that teenagers admit that they accept unknowns as «friends», and although they know it is dangerous they still do so. In Colombia, the teenagers acknowledged that they added unknowns to their list of friends, while in Spain most teenagers declared that they only accept people they know, yet this was proved to be untrue. In this sense, it is necessary to extend this research to other national and cultural backgrounds to make a transnational comparison.

References

Aydm, B. & Volkan San, S. (2011). Internet Addiction among Adolescents: The Role of Self-esteem. Procedia-Social and Behavior Sciences, 15, 3500-3505. (DOI: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.325).

Backstrom, L., Huttenlocher, D. & al. (2006). Group Formation in Large Social Networks: Membership, Growth, and Evolution. In Proceedings of 12th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery in Data Mining (pp. 44-54). New York: ACM Press.

Bernicot, J., Volckaert-Legrier, O. & al. (2012). Forms and Functions of SMS Messages: A Study of Variations in a Corpus Written by Adolescents. Journal of Pragmatics, 44 (12), 1701-1715. (DOI: 10.1016/j.pragma.2012.07.009).

Boyd, D. & Ellison, N. (2007). Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13, 210-230.

Byrne, D. (2007). The Future of (the) Race: Identity, Discourse and the Rise of Computer Mediated Public spheres. In A. Everett (Ed.), MacArthur Foundation Book Series on Digital Learning: Race and Ethnicity (pp. 15-38). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Calvete, E., Orue, I. & al. (2010). Cyberbullying in Adolescents: Modalities and Aggressor Profile. Computers in Human Behavior, 26 (5), 1128-1135. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.017).

Flores, J.M. (2009). Nuevos modelos de comunicación, perfiles y tendencias en las redes sociales. Comunicar, 33, 73-81. (DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/c33-2009-02-007).

Foon-Hew, K. (2011). Students and Teachers Use of Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 27 (2), 662-676. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.11.020).

Gonzales, A.L. & Hancock, J.T. (2011). Mirror, Mirror on my Facebook Wall: Effects of Exposure to Facebook on Self-esteem. Cyberpsychology Behavior Social Networking, 14(1-2), 79-83. (DOI: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0411).

Gross, R. & Acquisti, A. (2005). Information Revelation and Privacy in Online Social Networks. In Proceedings of WPES’05 (pp. 71-80). Alexandria, VA: ACM.

Haythornthwaite, C. (2005). Social Networks and Internet Connectivity Effects. Information. Communication and Society, 8, 125-147. (DOI: 10.1080/13691180500146185).

Hinduja, S. & Patchin, J.W. (2008). Personal Information of Adolescents on the Internet: A Quantitative Content Analysis of MySpace. Journal of Adolescence, 31 (1), 125-146. (DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.05.004).

Hjorth, L. & Kim, H. (2005). Being There and Being Here: Gendered Customising of Mobile 3G Practices through a Case Study in Seoul. Convergence, 11 (2), 49-55. (DOI: 10.1177/1354856507084421).

Jagatic, T., Johnson, N.A. & al. (2007). Social Phishing. Communications of the ACM, 5 (10), 94-100. (DOI:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x).

Junco, R. (2012). The Relationship between Frequency of Facebook Use, Participation in Facebook Activities, and Student Engagement. Computers and Education, 58 (1), 162-171. (DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.004).

Law, D.M., Shapka, J.D. & Olson, B.F. (2010). To Control or not Control? Parenting Behaviours and Adolescent Online Aggression. Computers in Human Behavior, 26 (6), 1651-1656. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.013).

Liu, H., Maes, P. & Davenport, G. (2006). Unraveling the Taste Fabric of Social Networks. International Journal on Semantic Web and Information Systems, 2 (1), 42-71. (DOI: 10.4018/jswis.2006010102).

Marwick, A. (2005). I’m a lot More Interesting than a Friendster Profile: Identity Presentation, Authenticity, and Power in Social Networking Services. Congress Internet Research 6.0. Chicago, IL, october 1. (http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1884356) (30/09/2012).

Mazur, E. & Richards, L. (2011). Adolescents and Emerging Adults Social Networking Online: Homophily or Diversity? Journal of Applied Development Psychology, 32 (4), 180-188. (DOI:10.1016/j.appdev.2011.03.001).

McAndrew, F. & Jeong, H.S. (2012). Who does What on Facebook? Age, Sex, and Relationship Status as Predictors of Facebook Use. Computers in Human Behavior, 28 (6), 2359-2365. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.007).

McBride, D.L. (2011). Risks and Benefits of Social Media for Children and adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 26 (5), 498-499. (DOI: 10.1016/j.pedn.2011.05.001).

Moore, K. & McElroy, J. (2012). The Influence of Personality on Facebook Usage, Wall Postings, and Regret. Computers in Human Behavior, 28 (1), 267-274. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2011.09.009).

Moreau, A. Roustit, O. & al. (2012). L’usage de Facebook et les enjeux de l’adolescence: une étude qualitative. Neuropsychiatire de L´Enfance et de l’Adolescence, 60 (6), 429-434. (DOI: 10.1016/j.neurenf.2012.05.530).

Ng, W. (2012). Can We Teach Digital Natives Digital Literacy? Computers and Education, 59 (3), 1065-1078. (DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.04.016).

Nyland, R. & Near, C. (2007). Jesus is my Friend: Religiosity as a Mediating Factor in Internet Social Networking use. AEJMC Midwinter Conference, February 23-24, Reno, NV.

Ong, E., Ang, R. & al. (2011). Narcissism, Extraversion and Adolescents’ Self-presentation on Facebook, Personality and Individual Differences, 50 (2), 180-185. (DOI: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.022).

Piscitelli, A. (2010). El proyecto Facebook y la posuniversidad. Sistemas operativos sociales y entornos abiertos de aprendizaje. Barcelona: Ariel.

Preibusch, S., Hoser, B. & al. (2007). Ubiquitous Social Networks. Opportunities and Challenges for Privacy-aware User Modelling. Proceedings of Workshop on Data Mining for User Modeling. Corfu, Greece.

Pumper, M. & Moreno, M. (2012). Perception, Influence, and Social Anxiety among Adolescent Facebook Users. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50 (2), S52-S53. (DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.142).

Ross, C. & Orr, E. (2009). Personality and Motivations Associated with Facebook Use. Computers and Human Behavior, 25 (2), 578-586. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.12.024).

Schwarz, O. (2011). Who Moved my Conversation? Instant Messaging, Intertextuality and New Regimes of Intimacy and Truth. Media Culture Society, 33 (1), 71–87. (DOI: 10.1177/0163443710385501).

Skog, D. (2005). Social Interaction in Virtual Communities: The Significance of Technology. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 1 (4), 464-474. (DOI: 10.1504/IJWBC.2005.008111).

Soep, E. (2012). Generación y recreación de contenidos digitales por los jóvenes: implicaciones para la alfabetización mediática. Comunicar, 38, 93-100. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C38-2012-02-10).

Stutzman, F. (2006). An Evaluation of Identity-sharing Behavior in Social Network Communities. Journal of the International Digital Media and Arts Association, 3 (1), 10-18.

Timmis, S. (2012). Constant Companions: Instant Messaging Conversations as Sustainable Supportive Study Structures Amongst Undergraduate Peers. Computers and Education, 59 (1), 3-18. (DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.09.026).

Valcke, M., De Wever, B. & al. (2011). Long-term Study of Safe Internet Use of Young Children. Computers and Education, 57(1), 1.292-1.305. (DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.01.010).

Varas-Rojas, L.E. (2009). Imaginarios sociales que van naciendo en comunidades virtuales: Facebook, crisis analógica, futuro digital. IV Congreso Online del Observatorio para la Cibersociedad, november 12-29. (www.cibersociedad.net/congres2009/actes/html/com_imaginarios-sociales-que-van-naciendo-en-comunidades-virtuales-facebook_709.html) (30-10-2012).

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Las redes sociales se han convertido en ámbitos de interacción social entre los jóvenes, que crean un perfil para relacionarse con los demás. La exposición pública en el caso de los adolescentes puede generar problemas sobre aspectos sociales, emotivos y afectivos. Esta investigación analiza cómo se usa Facebook por parte de los jóvenes y qué experiencia obtienen de ello. Aunque dicen conocer los riesgos, admiten que aceptan a desconocidos como amigos y ofrecen datos reales sobre su vida. Ante esta situación, se hace más evidente la necesidad de la alfabetización mediática y digital de estos jóvenes que, aunque no deberían estar en Facebook hasta los 13 años, cuentan con un perfil de manera mayoritaria. Para ello se ha utilizado una metodología basada en el análisis de contenido y las entrevistas en profundidad. Se trata de un estudio comparativo entre Colombia y España. En Colombia se han realizado 100 análisis de perfiles y 20 entrevistas en profundidad. La muestra ha sido de adolescentes de 12 a 15 años, de la Institución Educativa Distrital Técnico Internacional de Bogotá. En España se han analizado 100 perfiles y se han realizado 20 entrevistas a chicos de 12 a 15 años, de Institutos (IES) de Andalucía.

1. Introducción

Desde su aparición, las redes sociales, tales como Facebook, MySpace, Cyworld, Linkedin, Bebo o Twitter, entre otras, han atraído a millones de usuarios (Foon-Hew, 2011). Muchos de ellos han integrado estos sitios web en sus prácticas diarias (Boyd, 2007; Piscitelli, 2010). Schwarz (2011) sugiere que los jóvenes se están alejando de la primacía del teléfono o de la interacción cara a cara a la comunicación basada en texto, especialmente mensajería, como método preferido de comunicación instantánea. Las redes sociales permiten una nueva forma de comunicarse, de relacionarse y de crear comunidades (Varas Rojas, 2009).

Haythornthwaite (2005) señala que lo que diferencia a las redes sociales no es que permiten a los individuos conocer a desconocidos, sino que permiten a los usuarios articular y hacer visibles sus redes sociales. Esto puede dar lugar a las conexiones entre los individuos (Timmis, 2012), que de otra manera no podrían conocerse.

1.1. Antecedentes de investigación sobre redes sociales

La mayor parte de la investigación sobre redes sociales se ha centrado en: a) la representación de sí mismo y desarrollo de la amistad en red; b) la estructura; c) la privacidad.

• Estudios sobre representación de sí mismo y desarrollo de la amistad en red: Al igual que otros contextos en línea en los que los individuos son conscientemente capaces de construir una representación de sí mismos, las redes sociales constituyen un contexto de investigación importante para los estudios de los procesos de gestión de la auto-presentación y el desarrollo de la amistad, tal como han estudiado Junco (2012), McAndrew & Jeong (2012), Ross, Orr & al. (2009) y Moore & McElroy (2012). Aunque la mayoría de los sitios invitan a los usuarios a construir representaciones exactas de sí mismos, los participantes suelen hacerlo en diversos grados (Marwick, 2005; Ong, Ang & al. (2011). Marwick, encontró que los usuarios de sitios de redes sociales manejan complejas estrategias para la negociación de su «auténtica» identidad.

• Estudios sobre estructuras de los sitios de redes sociales: Investigadores de redes sociales también se han interesado por la estructura de la redes de amistad. Skog (2005) sostuvo que los miembros de las redes sociales no son pasivos, sino que participan en la evolución social de la Red. Asimismo, se han desarrollado estudios sobre las motivaciones de las personas para unirse a determinadas comunidades (Backstrom, Hottenlocher & al., 2006). Liu, Maes y Davenport (2006) argumentaron que las conexiones de los amigos no son la única estructura de la Red que vale la pena investigar. Ellos examinaron las formas en que los gustos (música, libros, películas, etc.) constituyen una estructura de red alternativa, a la que ellos llaman «redes por gustos». Finalmente, Soep (2012: 98) señala que «los jóvenes están desarrollando nuevos códigos de conducta y creando modelos para apoyar la producción más allá de la publicación» y Gonzales y Hancock (2011) estudian los efectos de la utilización de Facebook.

• Estudios relacionados con la privacidad: La cobertura de los medios de comunicación de masas sobre las redes sociales se ha centrado en los posibles problemas de privacidad, sobre todo en la seguridad de los usuarios más jóvenes (Flores, 2009: 80), cyberbullying y otros posibles riesgos (Calvete, Orue & al., 2010; Law, Shapka & Olson, 2010; Hinduja & Patchin, 2008; McBride, 2011).

En uno de los primeros estudios académicos acerca de la intimidad y los sitios de redes sociales, Gross y Acquisti (2005) analizaron 4.000 perfiles de Facebook y describieron las amenazas potenciales para la privacidad originadas en la información de carácter personal incluida en el sitio.

Stutzman (2006), en su estudio a partir de encuestas a los usuarios de Facebook en el 2006, describe la «paradoja de la privacidad» que ocurre cuando los adolescentes no son conscientes de la naturaleza pública de Internet. Jagatic, Johnson y otros (2007) utilizaron los datos de perfiles de libre acceso de Facebook para elaborar una «suplantación de identidad». Los datos de este estudio ofrecen una perspectiva más optimista y sugiere que los adolescentes son conscientes de las amenazas potenciales de privacidad en línea. También la investigación concluye que de los adolescentes con perfiles completamente abiertos, el 46% reportó que incluye al menos algunos datos falsos de la información que publica (Jagatic, Johnson & al., 2007: 97).

La privacidad también está implicada en la capacidad de los usuarios para controlar y gestionar su identidad. Las redes sociales no son la panacea. Preibusch, Hoser y otros (2007) argumentaron que las opciones de privacidad que ofrecen las redes sociales no proporcionan a los usuarios la flexibilidad que necesitan.

Además de los temas mencionados anteriormente, un creciente número de estudios se dirige a otros aspectos. Por ejemplo, estudios que abordan la raza y la etnicidad (Byrne, 2007), la religión (Nyland & Near, 2007), cómo se ve afectada la sexualidad por la redes sociales (Hjorth & Kim, 2005) y estudios sobre el uso que determinados segmentos de la población hacen de las redes sociales, como es el caso de los niños (Valcke, De-Wever & al., 2011), los adolescentes (Pumper & Moreno, 2012; Moreau, Roustit & al., 2012; Chauchaud & Chabrol, 2012; Aydm & Volkan-San, 2011; Bernicot, Volckaert-Legrier & al., 2012; Mazur & Richards, 2011) o los nativos digitales (Ng, 2012).

2. Materiales y métodos

Para la investigación se ha utilizado una metodología mixta con técnica cualitativa (entrevistas en profundidad) y cuantitativa (análisis de contenido). Es un estudio comparativo entre Colombia y España entre adolescentes de ambos países. La investigación se llevó a cabo mediante la observación de 100 perfiles de Facebook y 20 entrevistas en profundidad a adolescentes de 12 a 15 años de Colombia y de 100 perfiles de Facebook y 20 entrevistas en profundidad en España. En Colombia el estudio se ha realizado a adolescentes de la Institución Educativa Distrito Técnico Internacional de Bogotá. En España se ha estudiado a chicas y chicos de diferentes institutos de Andalucía (Los Olivos, Torre Atalaya, Alyanub, El Palmeral, El Jaroso y Rey Alabez). La selección de los centros educativos se hizo de forma aleatoria. Se analizó el perfil en Facebook de los adolescentes que aceptaron participar en la investigación. Entre ellos, también de forma aleatoria, se seleccionó a las personas a las que se les realizó entrevistas en profundidad.

Para el análisis de contenido de los perfiles en Facebook se elaboró una plantilla de análisis en la que se contemplaban las variables e ítems de la investigación, que contenía aspectos tales como la frecuencia de las entradas, el lenguaje utilizado en las mismas, el número de fotografías y descripción de ellas, el número de amigos y los datos personales (aficiones, gustos, relaciones de pareja, etc.). Por lo que respecta a las entrevistas en profundidad, los temas tratados eran los usos y las gratificaciones de las redes sociales y los porqués de aspectos concretos que aparecían en sus perfiles. El periodo de análisis se inició en mayo de 2011 y finalizó en mayo de 2012. En los ejemplos del estudio no se incluyen ni nombres ni fotos porque todos son menores.

3. Análisis y resultados

3.1. El caso de los adolescentes colombianos

a) Cómo se representan en Facebook

Para los adolescentes estudiados tener un perfil en Facebook significa administrar su personalidad. Crear un perfil en Facebook y asignar un contenido a los campos que la interfaz tiene preestablecidos es un acto de creación de un ser en un entorno digital. Aunque se trata de presentarse como ellos son, también hay lugar a presentarse como ellos quisieran ser. Los adolescentes tienen claro que de la presentación que ellos hagan de sí mismos en la red social, depende algo muy importante en esta etapa de la vida: su socialización, tanto real como virtual.

En este sentido, comprobamos cómo el nombre que deciden adoptar los adolescentes en Facebook, describe atributos de su identidad. De los 100 perfiles estudiados, 45 adolescentes asumen otros nombres que guardan poca o ninguna coherencia con el nombre de su identidad real. Para ellos es muy importante la escritura de su nombre, su apariencia. Uno de los chicos colombianos entrevistados explica que «mi nombre es así porque se ve chévere… además porque yo escucho Ska y Punk» o, en la misma línea, otra joven argumenta su cambio de nombre: «siempre que en Facebook escribo la C no escribo la e. Es para que se vea diferente. Y Tanz lo que significa es que pertenezco a un grupo de seis amigas del colegio pero además tenemos un grupo con ese nombre en Facebook».

b) Su imagen de perfil: maquillaje y perfumado de pixeles

La imagen que los adolescentes publican para ser identificados en la red social es uno de los elementos a los que dedican mayor tiempo: piensan su imagen, la diseñan, la crean, la producen, la editan… la reeditan. Sin embargo, ellos construyen su imagen en soledad. Al observar las «Fotos de perfil» de los 100 perfiles de Facebook estudiados, nos encontramos que la mayoría aparecen solos. Además, la fotografía ha sido hecha por ellos mismos mediante un espejo.

Una adolescente nos explica cómo ha construido la mayoría de fotos de su perfil en las que generalmente aparece sola: «Tomarse fotos frente al espejo no es una moda, solo que es más sencillo, porque uno ve cómo va quedando… por eso muchas fotos me las tomo en el baño. Hay fotos que no me gustan, por eso no las subo… Además las fotos que subo casi siempre las arreglo. Casi a todos los chicos les gustan mis fotos… yo creo que por eso me llegan tantas solicitudes de amistad». Si sumamos la cantidad de «Fotos de perfil» de los 100 perfiles de Facebook estudiados, suman 2.612 fotografías, en promedio 26,1 publicadas en cada perfil. Además, es interesante observar cómo los adolescentes que tienen un número mayor de fotografías en el álbum «Fotos de perfil» son mujeres.

c) La información del perfil

Dentro del vinculo «Información» de un perfil de Facebook, aparece un campo que se llama «Acerca de mí». Al observar los 100 perfiles analizados, nos encontramos que 33 perfiles publican información de sí mismos en este vinculo, pero lo más interesante es que a pesar de que la interfaz está dispuesta para que los usuarios incluyan información únicamente como texto, encontramos que varios de los adolescentes utilizan las posibilidades del teclado y la lógica de copiar y pegar para generar imágenes.

Publican su fecha de nacimiento, aunque no sea del todo verdadera (tienden a aumentarla), publican su lugar de residencia, su lugar de estudio, su música favorita, sus películas favoritas, sus programas de televisión preferidos y sus actividades e intereses. Sin embargo, no publican de sí mismos, sus creencias religiosas, ni su filiación política, ni sus deportes favoritos ni sus libros favoritos.

Así como la amistad, enamorarse empieza a estar mediado por la tecnología. Para los adolescentes entrevistados, ver publicada una relación en Facebook es tener la certeza de que esa relación sentimental existe en la vida real. De los 100 perfiles de Facebook estudiados, 22 publican información relacionada con las relaciones sentimentales que tienen sus usuarios. En seis casos encontramos que los adolescentes mencionan que están casados, sin ser eso cierto.

d) Cómo se relacionan

Para los adolescentes, tener amigos en Facebook es más que tener una lista de contactos. Significa más bien gestionar las relaciones de amistad en otro escenario donde la imagen es el principal vínculo. Así lo confirma, por ejemplo, una de las jóvenes colombianas entrevistadas. A sus 13 años explica que «para que yo agregue a alguien como mi amigo tiene que tener una foto bonita, tiene que ser pinta o estar lindo… (risas) y tener amigos en común, porque sé que si alguno de mis amigos lo conoce, no es tan peligroso. Sin embargo, si me solicita que lo agregue como amigo alguien con quien no tenga amigos en común, le miro bien las fotos y si es lindo, lo agrego».

Para estos jóvenes, tener un amigo en Facebook no significa necesariamente conocerse cara a cara. Varios de los adolescentes entrevistados aceptan que conversan con «amigos de Facebook» que nunca han visto.

Si sumamos el número de amigos de los 100 perfiles de Facebook estudiados, suman 34.730. ¿Pero cómo llegan a tener este número de amigos en sus perfiles? Agregan como amigos a personas que no conocen siguiendo dos criterios: en sus fotografías deben aparecer «lindas o guapos» y deben tener amigos en común. Sin embargo, el primer criterio puede ser suficiente para aceptar una solicitud de amistad. Decidir aceptar o rechazar una solicitud de amistad en Facebook es una decisión que los adolescentes toman muy rápidamente. Los adolescentes entrevistados no tardan más de 20 segundos en aceptar la solicitud de amistad de alguien y no suelen rechazar muchas solicitudes de amistad.

A diferencia del mundo real, en el que los adolescentes entablan relaciones con adultos como sus profesores, padres, autoridades, etc., en sus perfiles de Facebook los adultos son vedados, solo cinco han agregado como amigos a sus padres o tíos, dos han agregado a su profesores y la mayoría de ellos dice que no le gustaría que sus padres se enteraran de lo que hay en sus perfiles.

Las conversaciones de los adolescentes en Facebook giran en torno a su imagen. Hay muy pocos mensajes que tengan que ver con algo distinto a la imagen sobre sí. Las imágenes son las que comienzan conversaciones y relaciones. La mayoría de los textos que encontramos son muy cortos. En cambio, encontramos muchas fotografías. Los motivos nos los explica una de las jóvenes que entrevistamos. Argumenta que «cuando yo publico alguna foto y nadie la comenta, la borro, para qué dejar algo que a nadie le interesa. Por ejemplo, las fotos más comentadas son las últimas que he subido, más o menos voy descubriendo que le gusta ver a mis amigos… bueno creo que son las fotos más sexy». Si sumamos las fotos publicadas en los 100 perfiles de Facebook estudiados se obtiene 11.426, en promedio 114,26 publicadas en cada perfil.

La imagen se ha convertido, además, en la manera de expresar afecto. Hacer una foto para otro, subirla a Facebook y compartirla es la manera de expresar afecto. A esto ellos le llaman un «zing», derivado del inglés «sign», que es una firma que se agrega en una fotografía para subir a Facebook, con un mensaje para algún amigo/a.

Los adolescentes, para comunicarse en Facebook, han generado una serie de códigos nuevos de escritura, que no tienen en cuenta la gramática y las reglas ortográficas, sino que obedecen a otras condiciones como la velocidad de escritura y especialmente las estéticas digitales. Vemos cómo la escritura se ve afectada por normas caprichosas, emergen nuevas maneras de escribir como lo que denominamos «textos-imagen»: creados a partir de signos del teclado, en los que las letras se convierten en partes de imágenes que significan algo totalmente distinto a su significado lingüístico.

e) Grupos en Facebook: nuevas maneras de pertenecer

Para los adolescentes colombianos, pertenecer a un grupo de Facebook no es únicamente una manera de sentirse parte de algo, es tener una imagen común que cobija a los miembros, que los protege, que les permite actuar como un «yo» colectivo. Ser parte de un grupo es pertenecer a una comunidad real.

3.2. El caso de los adolescentes españoles

a) Cómo se representan en Facebook

La inmensa mayoría (95%) de los jóvenes de la muestra española utiliza su nombre real en su perfil de Facebook. Sin embargo, cuando se les pregunta en las entrevistas por este aspecto, la mitad de los entrevistados manifiesta que es peligroso utilizar el nombre real y reconoce alguna joven que «mi madre siempre me ha explicado que no debo indicar ningún dato real, porque cualquiera con malas intenciones me podría localizar». Es decir, parece que dominan la teoría, pero se olvidan al llevarla a la práctica.

La mayoría de los adolescentes analizados ofrece todos los contenidos de su perfil y muro a quien quiera leerlos. Únicamente un grupo reducido tiene limitado el acceso. Al preguntarles por este tema en las entrevistas, la mayoría respondía que ni sabía qué opción de privacidad tenía activada. En este sentido, una de las personas entrevistadas, nos indicaba que «no pasa nada por compartir en Facebook. Todos mis amigos lo hacen. Como somos muchos nadie se va a interesar por lo que yo haga o diga». Es decir, el hecho de que lo habitual entre sus colegas sea compartir, se interpreta por esta joven como una ausencia de peligro.

Con la edad no son tan honestos. Casi ninguno dice la verdad. Facebook tiene establecido que se debe tener un mínimo de 13 años para abrirse un perfil en esta red social. Los adolescentes quieren estar en la Red antes de esta edad y solucionan el problema diciendo que nacieron unos años antes de la fecha real. La mayoría de los jóvenes analizados utilizan el muro para compartir enlaces, fotografías, comentar fotografías de compañeros y recibir comentarios. Sin embargo, salvo alguna excepción, la actividad en estos muros no es muy frecuente. La media es tres o cuatro publicaciones al mes. Lo hemos podido comprobar al hacer el análisis de sus perfiles, pero también nos lo han confirmado los entrevistados, quienes mayoritariamente han confesado que suelen hacer menos de cinco publicaciones al mes. Estas publicaciones se suelen hacer desde casa, tal como manifiestan.

b) Su imagen de perfil y fotografías incluidas

Como sucede con los adolescentes colombianos, los españoles también hacen un gran uso de la fotografía en su perfil. El 78% cuelga fotos en su perfil sin retocar, un 6% utiliza fotos retocadas, un 13% fotografías de diseño y únicamente un 3% no tiene foto de perfil. Generalmente, en el perfil se van a mostrar fotos del protagonista o de la protagonista solo/a (en el 60% de los casos), seguido de fotos con amigos (un 20% de los casos). El 20% restante se divide entre fotos con la pareja (6%), con familiares (3%), fotos de paisajes (6%) o de personajes conocidos, reales como los futbolistas (4%) o irreales como los Simpson (1%).

Las fotos que ponen los adolescentes en su perfil suelen ser posados (algunos muy poco naturales). La sensación que se tiene al verles es que están imitando a sus líderes televisivos o mediáticos. En el caso de las fotos retocadas o de diseño, se incrementa aún más esta voluntad de emular a sus líderes mediáticos. Uno de los jóvenes españoles entrevistados nos reconocía que existe cierta competencia entre sus amigos para ver quién cuelga la foto más llamativa, más polémica u original.

El número de fotos en el perfil («Fotos de perfil») oscila entre las 251 que tiene una joven y la única foto que tienen varios de los perfiles analizados. La media de fotos por perfil es de 23. Curiosamente, como también sucede en Colombia, son mujeres quienes más fotos tienen en su perfil.

La media de fotos incorporadas en cada caso es bastante superior: 168. Dos de los adolescentes (de las adolescentes, pues son mujeres en ambos casos) analizados tienen más de 1.100 fotos, concretamente 1.116 y 1.184. Algo semejante sucede con el número de álbumes, que oscila entre los 32 y ninguno. La media de álbumes en los adolescentes es de 5,4.

Por su parte, la media de fotos compartidas, también es elevada. Hasta 817 fotos comparte uno de los adolescentes analizados y la media es de 120 fotografías compartidas por joven. De estas fotos compartidas, las más comentadas son las fotografías con amigos y amigas (36%), seguidas de lejos por foto-montajes (10%), fotos de posados (9%), retocadas (9%) y fotos con familiares (3%). Es decir, los amigos y amigas de estos adolescentes suelen comentar fotografías en las que salen ellos mismos o personas conocidas. Si la fotografía ha sido retocada o se trata de un montaje, parece que también despierta el interés de los adolescentes.

c) La información del perfil

El 84% de los jóvenes de la muestra no indican en sus perfiles de Facebook los idiomas que hablan. Curiosamente, quienes sí lo indican hablan más de un idioma: el 9% dice hablar español, inglés y francés, el 6% habla español e inglés y un 1% dice que habla inglés, francés, español y latín.

Ni la filosofía, ni la religión, ni el partido político por el que se siente simpatía suelen ser temas por los que se interesen los adolescentes. En el caso de la filosofía y la religión, únicamente un 12% se manifiesta católico y un 7% incluye en su perfil frases pronunciadas por conocidos personajes o frases filosóficas. Y, en el caso de los partidos políticos, únicamente un 2% indica en su perfil el partido con el que simpatiza. Tampoco suelen incluir una descripción de sí mismos en su perfil («Acerca de mí») y, quienes lo hacen, escriben frases como «Me gusta salir con mis amigas», «Soy un chico tímido, pero con encanto», incorporan frases hechas o expresan la mayor de las alegrías porque se sienten comprendidos por sus parejas. Los textos pueden estar escritos con palabras acortadas en las que suelen faltar las vocales (sin respetar nomas gramaticales ni ortográficas). En ningún caso se han encontrado «textos-imágenes» semejantes a los descubiertos en Colombia.

Las tres cuartas partes de los chicos y chicas que conforman la muestra no precisan su situación sentimental. Un 12% dice que está soltero/a, un 9% asegura tener una relación, un 3% está «prometido» y un 1% dice que está casado (evidentemente, no es verdad). En este sentido, uno de los jóvenes entrevistados explica que él nunca facilita sus datos reales: «digo que vivo en otro lugar, me invento mis datos… hasta mi nombre». Asegura que tener una falsa identidad no le supone ningún problema, pues «utilizo un nombre que mis amigos conocen y saben quién soy enseguida». El 98% de los adolescentes no indica ningún teléfono en Facebook como forma de contacto. Sin embargo, el 2% restante facilita su número de móvil. El 80% indica una dirección de correo electrónico, en la mayoría de los casos, terminado en hotmail.com.

d) Cómo se relacionan

Los adolescentes no hacen un uso ni continuado ni diario de Facebook. Lo habitual es que hagan tres o cuatro publicaciones al mes. Algo semejante sucede con el número de amigos. El joven con más amigos de la muestra española es un chico con 559 amigos, pero también hay otro caso en el que únicamente se tienen 3 amigos. De hecho, la media de amigos es de 202, una cifra moderadamente baja. Por ello, podemos deducir que esos adolescentes están comenzando a relacionarse en redes sociales y aún se mueven en sus círculos más próximos.

e) Grupos y aplicaciones

Los adolescentes españoles no suelen participar en grupos. Más del 80% no tiene grupos y, quienes lo hacen, participan en una media de 3,8. Sí que hacen un uso mayor de las aplicaciones. Cada uno de los jóvenes de la muestra, participa en 2 aplicaciones como media. La mayoría de las veces, estos jóvenes van a participar en juegos. «Aquarim», «Pet Shop City», «Sims Social» y «Dragon City» se encuentran entre los favoritos.

f) Los gustos de los adolescentes

En general, los adolescentes suelen no dar demasiadas explicaciones de sus gustos. Aunque hemos podido comprobar que el deporte favorito es el fútbol (un 54% de los perfiles analizados indican el fútbol como deporte favorito), en un 39% de los casos no se indica ningún deporte preferido. En los casos en los que sí se mencionan deportes, fútbol, tenis, voleibol, natación, baloncesto, paintball, pádel y ballet están entre los preferidos. La música que gusta a los adolescentes es la de Lady Gaga, Justin Beiber, David Guetta, Shakira, Jennifer López, Jonas Brothers, Michael Jackson, Beyoncé y Selena Gómez. Las películas preferidas son «Toy Story», «Tres metros sobre el cielo», «Crepúsculo», «High School Musical», «Avatar» y «Harry Potter». Los programas de televisión que más gustan a la muestra suelen ser programas de actualidad y humor, como «Tonterías las justas», «El intermedio», «El hormiguero» o «El club de la comedia»; concursos como «Tú sí que vales» o «Fama»; y series como «El barco», «El internado» o «Friends».

4. Discusión y conclusiones

Tanto en Colombia como en España, la mayoría de los jóvenes de 12 a 15 años utiliza Facebook para relacionarse con sus amigos y amigas. Es un medio más de socialización, tan importante o más que otros.

En ambos países los jóvenes tienen necesidad de «estar» en la Red y de mostrarse en ella de la forma más original posible (o, por lo menos, de lo que entienden por originalidad). Por ello, se manifiestan con un lenguaje propio, ajeno a las normas ortográficas y gramaticales al uso. Tanto en Colombia como en España utilizan esta peculiar forma de comunicarse. En el caso de Colombia, además, es habitual ofrecer lo que hemos venido llamando «texto-imagen», es decir, esas imágenes creadas a partir de texto. Esta manifestación de supuesta originalidad también queda patente en las fotografías. Tanto en España como en Colombia, los chicos y chicas compiten por subir fotos llamativas para sus compañeros/as: posados, fotos con gestos sugerentes, imágenes retocadas, montajes.

La mayoría se sobre-expone en las redes sociales. Muestra de ello son las 114,6 fotos por persona (de la muestra estudiada) en Colombia y las 168 fotos de cada miembro de la muestra española. Únicamente en las «Fotos de perfil», se alcanza la media de 26,1 fotografías por perfil en Colombia y de 23 en España. Cifras muy similares tanto en Colombia como en España.

Pero esta sobre-exposición va más allá de las fotografías. Un 95% de los chicos y chicas españoles utilizan su nombre real en su perfil de Facebook, mientras que en Colombia lo hace el 55%. O, mientras apenas indican cuál es su filiación política o religión, un grupo considerable no tiene ningún inconveniente en decir cuál es su relación sentimental. Curiosamente, tanto en Colombia como en España encontramos adolescentes que confiesan estar «casados», cuando evidentemente no es cierto.

Otro ejemplo de sobre-exposición lo encontramos con los datos de contacto que sobre sí mismos se ofrece. Lo más habitual es que los adolescentes indiquen una dirección de correo electrónico. Sin embargo, en el caso español, encontramos dos casos en los que se facilita el número del teléfono móvil. O, lo que puede ser también peligroso, los jóvenes admiten que aceptan como «amigos» a personas que no conocen. Saben que es peligroso, pero lo hacen. En el caso de Colombia, los adolescentes reconocen que así lo hacen, mientras que en España la mayoría dice que únicamente aceptan a personas conocidas, pero hemos comprobado que no es así, que aceptan también a desconocidos. En este sentido, sería necesario ampliar esta investigación a otros entornos culturales y nacionales para realizar comparativas entre los diferentes países.

Referencias

Aydm, B. & Volkan San, S. (2011). Internet Addiction among Adolescents: The Role of Self-esteem. Procedia-Social and Behavior Sciences, 15, 3500-3505. (DOI: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.325).

Backstrom, L., Huttenlocher, D. & al. (2006). Group Formation in Large Social Networks: Membership, Growth, and Evolution. In Proceedings of 12th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery in Data Mining (pp. 44-54). New York: ACM Press.

Bernicot, J., Volckaert-Legrier, O. & al. (2012). Forms and Functions of SMS Messages: A Study of Variations in a Corpus Written by Adolescents. Journal of Pragmatics, 44 (12), 1701-1715. (DOI: 10.1016/j.pragma.2012.07.009).

Boyd, D. & Ellison, N. (2007). Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13, 210-230.

Byrne, D. (2007). The Future of (the) Race: Identity, Discourse and the Rise of Computer Mediated Public spheres. In A. Everett (Ed.), MacArthur Foundation Book Series on Digital Learning: Race and Ethnicity (pp. 15-38). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Calvete, E., Orue, I. & al. (2010). Cyberbullying in Adolescents: Modalities and Aggressor Profile. Computers in Human Behavior, 26 (5), 1128-1135. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.017).

Flores, J.M. (2009). Nuevos modelos de comunicación, perfiles y tendencias en las redes sociales. Comunicar, 33, 73-81. (DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/c33-2009-02-007).

Foon-Hew, K. (2011). Students and Teachers Use of Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 27 (2), 662-676. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.11.020).

Gonzales, A.L. & Hancock, J.T. (2011). Mirror, Mirror on my Facebook Wall: Effects of Exposure to Facebook on Self-esteem. Cyberpsychology Behavior Social Networking, 14(1-2), 79-83. (DOI: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0411).

Gross, R. & Acquisti, A. (2005). Information Revelation and Privacy in Online Social Networks. In Proceedings of WPES’05 (pp. 71-80). Alexandria, VA: ACM.

Haythornthwaite, C. (2005). Social Networks and Internet Connectivity Effects. Information. Communication and Society, 8, 125-147. (DOI: 10.1080/13691180500146185).

Hinduja, S. & Patchin, J.W. (2008). Personal Information of Adolescents on the Internet: A Quantitative Content Analysis of MySpace. Journal of Adolescence, 31 (1), 125-146. (DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.05.004).

Hjorth, L. & Kim, H. (2005). Being There and Being Here: Gendered Customising of Mobile 3G Practices through a Case Study in Seoul. Convergence, 11 (2), 49-55. (DOI: 10.1177/1354856507084421).

Jagatic, T., Johnson, N.A. & al. (2007). Social Phishing. Communications of the ACM, 5 (10), 94-100. (DOI:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x).

Junco, R. (2012). The Relationship between Frequency of Facebook Use, Participation in Facebook Activities, and Student Engagement. Computers and Education, 58 (1), 162-171. (DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.004).

Law, D.M., Shapka, J.D. & Olson, B.F. (2010). To Control or not Control? Parenting Behaviours and Adolescent Online Aggression. Computers in Human Behavior, 26 (6), 1651-1656. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.013).

Liu, H., Maes, P. & Davenport, G. (2006). Unraveling the Taste Fabric of Social Networks. International Journal on Semantic Web and Information Systems, 2 (1), 42-71. (DOI: 10.4018/jswis.2006010102).

Marwick, A. (2005). I’m a lot More Interesting than a Friendster Profile: Identity Presentation, Authenticity, and Power in Social Networking Services. Congress Internet Research 6.0. Chicago, IL, october 1. (http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1884356) (30/09/2012).

Mazur, E. & Richards, L. (2011). Adolescents and Emerging Adults Social Networking Online: Homophily or Diversity? Journal of Applied Development Psychology, 32 (4), 180-188. (DOI:10.1016/j.appdev.2011.03.001).

McAndrew, F. & Jeong, H.S. (2012). Who does What on Facebook? Age, Sex, and Relationship Status as Predictors of Facebook Use. Computers in Human Behavior, 28 (6), 2359-2365. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.007).

McBride, D.L. (2011). Risks and Benefits of Social Media for Children and adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 26 (5), 498-499. (DOI: 10.1016/j.pedn.2011.05.001).

Moore, K. & McElroy, J. (2012). The Influence of Personality on Facebook Usage, Wall Postings, and Regret. Computers in Human Behavior, 28 (1), 267-274. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2011.09.009).

Moreau, A. Roustit, O. & al. (2012). L’usage de Facebook et les enjeux de l’adolescence: une étude qualitative. Neuropsychiatire de L´Enfance et de l’Adolescence, 60 (6), 429-434. (DOI: 10.1016/j.neurenf.2012.05.530).

Ng, W. (2012). Can We Teach Digital Natives Digital Literacy? Computers and Education, 59 (3), 1065-1078. (DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.04.016).

Nyland, R. & Near, C. (2007). Jesus is my Friend: Religiosity as a Mediating Factor in Internet Social Networking use. AEJMC Midwinter Conference, February 23-24, Reno, NV.

Ong, E., Ang, R. & al. (2011). Narcissism, Extraversion and Adolescents’ Self-presentation on Facebook, Personality and Individual Differences, 50 (2), 180-185. (DOI: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.022).

Piscitelli, A. (2010). El proyecto Facebook y la posuniversidad. Sistemas operativos sociales y entornos abiertos de aprendizaje. Barcelona: Ariel.

Preibusch, S., Hoser, B. & al. (2007). Ubiquitous Social Networks. Opportunities and Challenges for Privacy-aware User Modelling. Proceedings of Workshop on Data Mining for User Modeling. Corfu, Greece.

Pumper, M. & Moreno, M. (2012). Perception, Influence, and Social Anxiety among Adolescent Facebook Users. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50 (2), S52-S53. (DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.142).

Ross, C. & Orr, E. (2009). Personality and Motivations Associated with Facebook Use. Computers and Human Behavior, 25 (2), 578-586. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.12.024).

Schwarz, O. (2011). Who Moved my Conversation? Instant Messaging, Intertextuality and New Regimes of Intimacy and Truth. Media Culture Society, 33 (1), 71–87. (DOI: 10.1177/0163443710385501).

Skog, D. (2005). Social Interaction in Virtual Communities: The Significance of Technology. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 1 (4), 464-474. (DOI: 10.1504/IJWBC.2005.008111).

Soep, E. (2012). Generación y recreación de contenidos digitales por los jóvenes: implicaciones para la alfabetización mediática. Comunicar, 38, 93-100. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C38-2012-02-10).

Stutzman, F. (2006). An Evaluation of Identity-sharing Behavior in Social Network Communities. Journal of the International Digital Media and Arts Association, 3 (1), 10-18.

Timmis, S. (2012). Constant Companions: Instant Messaging Conversations as Sustainable Supportive Study Structures Amongst Undergraduate Peers. Computers and Education, 59 (1), 3-18. (DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.09.026).

Valcke, M., De Wever, B. & al. (2011). Long-term Study of Safe Internet Use of Young Children. Computers and Education, 57(1), 1.292-1.305. (DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.01.010).

Varas-Rojas, L.E. (2009). Imaginarios sociales que van naciendo en comunidades virtuales: Facebook, crisis analógica, futuro digital. IV Congreso Online del Observatorio para la Cibersociedad, november 12-29. (www.cibersociedad.net/congres2009/actes/html/com_imaginarios-sociales-que-van-naciendo-en-comunidades-virtuales-facebook_709.html) (30-10-2012).

Document information

Published on 28/02/13

Accepted on 28/02/13

Submitted on 28/02/13

Volume 21, Issue 1, 2013

DOI: 10.3916/C40-2013-03-03

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?