Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Minors are daily confronted with advertisements, which are occasionally controversial. In order to promote adolescents’ moral advertising literacy, this intervention study explores how to stimulate secondary education students’ knowledge on advertising law and their moral judgement of advertisements. Because a lot of new ?especially online? advertising formats have arisen during the last years, 191 students from 12 classes were randomly assigned to either a no tablet condition or a tablet condition (to raise authenticity of learning material). The results show that students who use tablet devices perform less well on a post-test about advertising law. Regarding adolescents’ moral judgement of advertisements, thematic analyses reveal that especially the use of nudity and feminine beauty are labelled as contentious in both conditions, because of, inter alia, the negative effects for adolescent girls’ self-image and the desire to lose weight. After the intervention, the tablet condition has proven to be more effective in promoting critical thinking about nudity/feminine beauty in advertisements. However, none of the conditions did provide evidence that a critical attitude towards alcohol advertising is encouraged. In this regard, implications for future research in the context of advertising literacy education are discussed.

1. Introduction

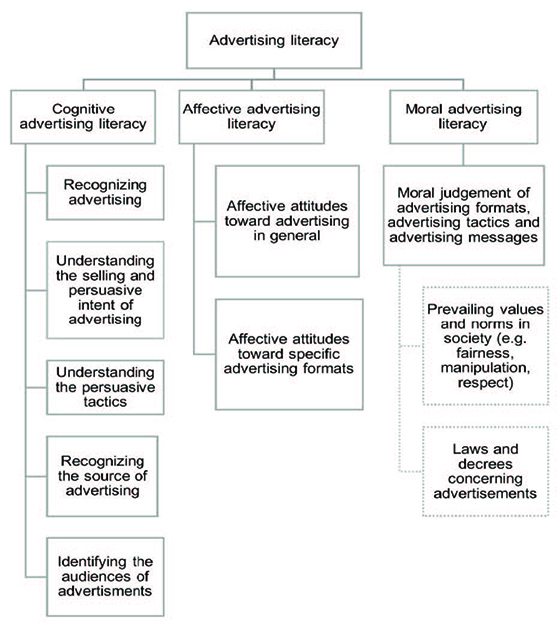

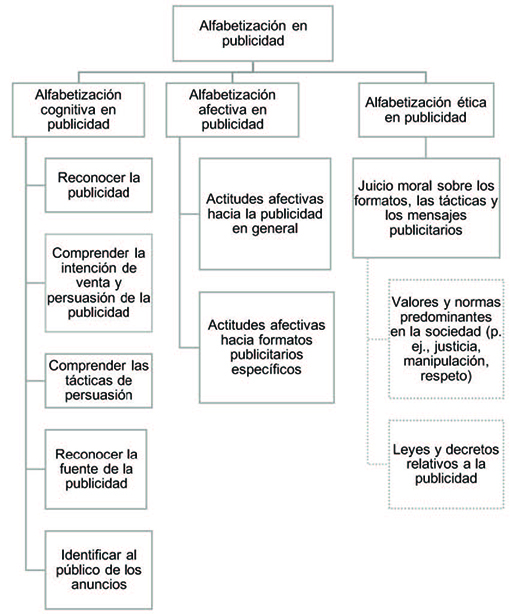

These days, children and youngsters are exposed to countless advertisements through various media (Hudders & al., 2015). Due to technological developments, a lot of new (mainly online) advertising formats have been established, such as social media advertising (e.g., brand pages on Facebook) (Daems & De-Pelsmacker, 2015). Because of these changes in the advertising landscape, the importance of promoting minors' advertising literacy increases (Hudders & al., 2015). The confrontation with new forms of media requires a new set of skills to access, analyse and evaluate images, sound and text (Aguaded, 2013). In general, advertising literacy can therefore be defined as 'the skills of analysing, evaluating, and creating persuasive messages across a variety of contexts and media' (Livingstone & Helsper, 2006: 562). More concretely, as depicted in Figure 1, three dimensions of advertising literacy can be distinguished.

As Aguaded (2011: 7) stated, 'The citizenship should take part in associations and organizations with the aim to build a responsible and critic society in which the power of the media is increasingly pervasive'. For this reason, the role of education has been repeatedly stressed to instil minors' advertising literacy (Calvert, 2008; Livingstone & Helsper, 2006). Although some advertising literacy programmes have already been developed during the past decades (e.g., Media Smart), Rozendaal, Lapierre, Van-Reijmersdal and Buijzen (2011) advocate for reformulating their focus since especially the cognitive dimension is emphasized in the past (Figure 1). Yet, there is a lack of evidence that cognitive advertising literacy is sufficient to decrease minors' susceptibility to advertising effects (Rozendaal & al., 2011).

1.1. Moral advertising literacy: law versus ethics?

As shown in Figure 1, it is expected that the regulatory framework of a country 'including standards for advertisers' implicitly impact one's perceptions about the appropriateness of advertising (Hudders & al., 2015; Martinson, 2001). In Flanders, a Media Decree with both general and product-specific (e.g., alcohol or medicinal products) requirements concerning advertising (towards minors) has been drawn up (Flemish Regulator for the Media, 2009; Verdoodt, Lievens, & Hellemans, 2015). In addition to law-related knowledge, 'in ethics, the question isn't whether one can do something or whether the law allows one to do it. Ethics assumes that, within the individual, there is a potential capacity for judging right from wrong' (Martinson, 2001: 132). A challenge for education is to alert students about the importance of ethics in their everyday life since it affects our behaviour and attitudes (Martinson, 2001). As De-Pelsmacker (2016) specified, there are several categories regarding ethical concerns in advertising. Next to insult and deception, another example is the use of sexist stereotypes. For instance, the contemporary norm of feminine beauty (i.e., tall, moderately breasted, and extremely thin) is fostered by the ideal bodies of ad models (Lavine, Sweeney, & Wagner, 1999). Not only advertisements spread via traditional channels as television and magazines contain gender-stereotypic images (Lavine & al., 1999), but this trend is perpetuated in Internet advertising, even on websites for adolescents (Slater, Tiggemann, Hawkins, & Werchon, 2012). Consequently, as adolescents copy ad models in their pictures on social networking sites, Tortajada, Araüna and Martinez (2013) refer to the internalization of socially constructed representations of femininity. Moreover, previous research (Grabe, Ward, & Hyde, 2008; Levine & Murnen, 2009) uncovered that stereotypical images in advertisements are correlated with drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction and disordered eating patterns in adolescent girls. Furthermore, the importance of advertising literacy education is demonstrated by McLean, Paxton and Wertheim (2016), who found that adolescents with low critical thinking skills are more negatively affected by viewing a feminine beauty ideal in advertisements.

Besides, there are ethical issues about product-specific advertisements, such as alcohol advertising (Anderson, de-Bruijn, Angus, Gordon, & Hastings, 2009; Ellickson, Collins, Hambarsoomians, & McCaffrey, 2005). Anderson and colleagues (2009) revealed that confrontation with alcohol advertising is associated with both the onset of adolescents' alcohol consumption and increased levels of drinking among adolescents who already drunk alcohol. Additionally, because of alcohol advertising, adolescents perceive alcohol-drinking peers as more favourably and consider alcohol use as more normative (Martino, Kovalchik, Collins, Becker, Shadel, & D'Amico, 2016). About this matter, advertising literacy education is also recommended because critical thinking and alcohol advertising deconstruction skills decrease not only adolescents' intention to drink alcohol, but also their susceptibility to the persuasive appeals of alcohol advertising (Ellickson & al., 2005; Scull, Kupersmidt, Parker, Elmore, & Benson, 2010).

In recent years, ethical questions arise over new advertising formats which increasingly expect active involvement of consumers (e.g., a Facebook like Button on brand pages) and often integrate commercial content into media content. The latter is noticeable in advertising formats as product placement, i.e., the integration of brands in films, television series, etc. (De-Pelsmacker, 2016). These characteristics of new advertising formats make it more difficult for children and youngsters to detect commercial messages (Hudders & al., 2015).

1.2. Constructivism as basis

To enhance adolescents' moral advertising literacy, learning material is developed in the context of this study. For this, constructivism 'a learning theory that became well-known in the last decades' was taken as a starting point. The rationale behind constructivism is that meaningful learning can be seen as an active process of constructing knowledge. It is assumed that knowledge is the result of personal interpretations, influenced by learners' gender, age, prior knowledge, ethnic background, etc. By sharing multiple perspectives, individuals can adapt their personal views (Duffy & Cunningham, 1996; Karagiorgi & Symeou, 2005). In this intervention, attention is paid to constructivist principles as collaborative learning, authentic learning and active learning. According to the first principle, the learning material includes opportunities to discuss multiple perspectives about controversial advertisements. Additionally, the principles of active learning and authentic learning assume that students receive meaningful learning activities in a realistic context allowing them to think about what they are doing, instead of passively receiving information from their teacher. To ensure authenticity, technology is used in this intervention because of the growing number of new (online) advertising formats.

1.3. Purpose of the current study

Until now, advertising literacy education primarily focuses on cognitive advertising literacy (Rozendaal & al., 2011) and traditional advertising formats (Meeus, Walrave, Van-Ouytsel, & Driesen, 2014). Therefore, the purpose of this explorative study is determining how adolescents' moral advertising literacy (i.e., moral judgement of advertising formats, advertising tactics and advertising messages) can be enhanced, which is becoming more important due to the growing number of new advertising formats.

The present study has two main research objectives. Firstly, we want to determine if advertising literacy education leads to better knowledge about advertising law. Secondly, this study provides an opportunity to advance knowledge of adolescents' moral judgement of controversial advertisements. Therefore, the second research objective is twofold, namely (1) revealing which advertisements are labelled as contentious by adolescents; (2) determining whether there is a difference between students' moral judgement about nudity/feminine beauty in advertisements and alcohol advertising on Facebook after an educational intervention.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study participants

An intervention study was set up in 12 classes (n=191) belonging to grades 9 and 10 of the Flemish education system. More concretely, the participating classes were part of general secondary education. This track was chosen based on an analysis of the curriculum standards (Adams, Schellens, & Valcke, 2015).

The students were between 14 and 18 years old (M=15.42; SD=0.67), and were primarily girls (81%). Although 12 classes were involved, only nine teachers participated because three of them were responsible for the lesson in two classes of the same school. Informed consent was obtained from all teachers. Moreover, a letter 'which included both information about the study and the option to refuse participation' was distributed to the adolescents' parents.

2.2. Design and procedure

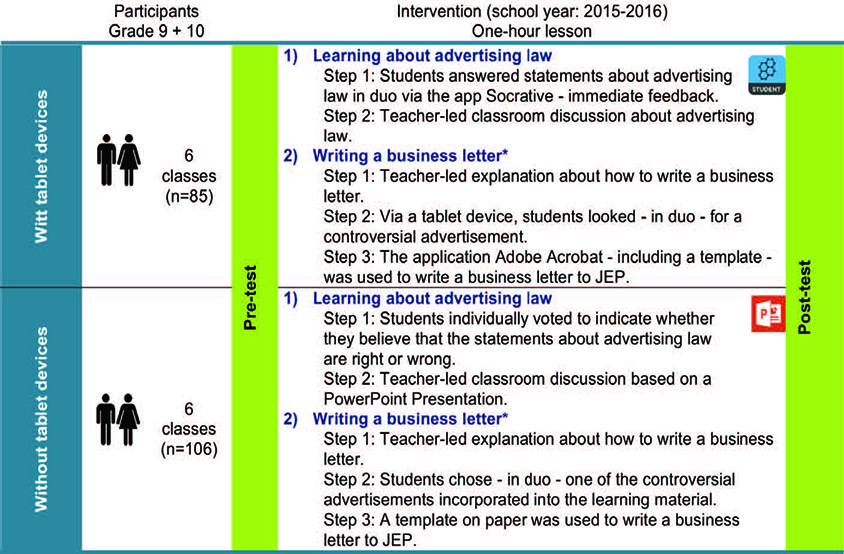

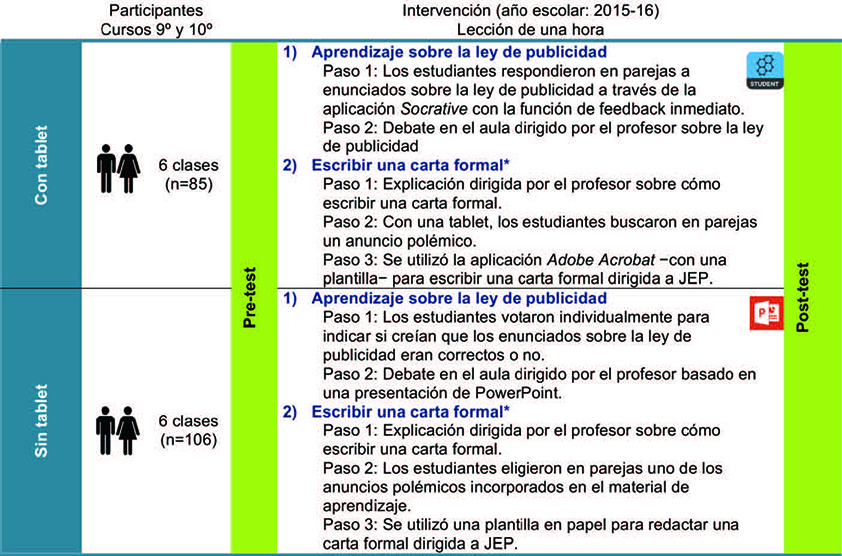

Participating classes were randomly divided into two conditions, one with and one without the use of tablet devices. Figure 2 shows a detailed overview of the learning material used in the tablet (TC) and no tablet condition (NTC).

As Vanderhoven and colleagues (2014) show that a one-hour media literacy course could be effective, we consciously chose for a short-term intervention. To assure external validity, the intervention took place in an authentic classroom setting. Since the regular teacher gave the lesson, a manual was developed, including background information about advertising and detailed step-by-step instructions about how to teach the lesson. The first author of this paper verified if the lesson was taught as prescribed.

2.3. Measurements and analyses

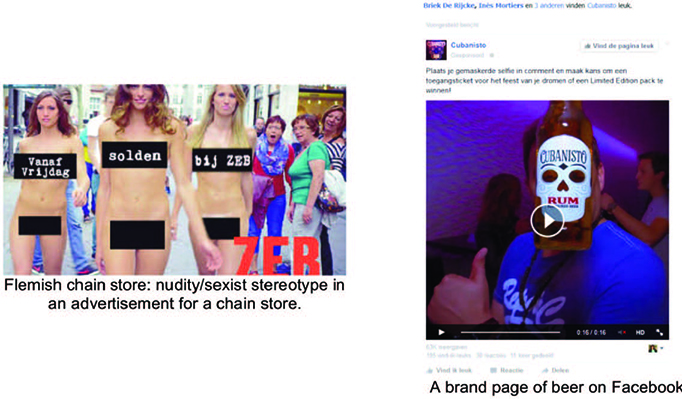

As depicted in Figure 2, a pre- and post-test were used to reveal effects of advertising literacy education on both students' knowledge about advertising law and their moral judgement of contentious advertisements. The pre- and post-test were given to the students a few days before and immediately after the intervention respectively, via an online link that they need to fill in at home. On the one hand, these tests included five true/false statements (Table 1) about law-related topics that were tackled during the lesson. On the other hand, students were confronted with two controversial advertisements to explore whether students' critical thinking can change through advertising literacy education (Figure 3).

The first image is a television advertisement of a Flemish chain store that was labelled as provocative in 2013, because of the naked/feminine beauty models. The second image was an alcohol advertisement of a new beer type on Facebook. In this message it is suggested to make a selfie that resembles the depicted image in order to win a ticket for 'the party of your dreams' or a 'Limited Edition pack' of this beer. Because there are strict rules concerning alcohol advertisements directed to minors in Flanders (Flemish Regulator for the Media, 2009), ethical questions arise regarding alcohol advertisements on Facebook, which is still the most widely used social networking site by Flemish adolescents (Apestaartjaren, 2016). Students' opinions were measured through the Inference of Manipulative Intent (IMI) Scale (Campbell, 1995) and an open-ended question. The IMI-scale originally consists of six items (Cronbach's alpha=0.93), which were 'because of linguistic reasons' reduced to four in this study. For instance, one of the IMI-items is: 'The advertiser tried to manipulate the audience in ways that I don't like'. The items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 completely disagree; 6 completely agree). Reliability analysis generated acceptable Cronbach alpha's (Nuditypre=0.85; Nuditypost=0.81; Alcoholpre=0.82; Alcoholpost=0.79). Quantitative data obtained by the pre- and post-test were analysed using the statistical software program SPSS. The data of the open question (i.e., 'Why is this advertisement (not) acceptable for you?') were processed through thematic analysis (see below). In the post-test, students also received questions related to their perceptions of the lesson (e.g., 'I learned more in the lessons about advertisements than in other lessons because of the use of tablet devices'). Unfortunately, although several reminders were sent to the students, 148 students fully completed both pre- and post-test (TC: n=66; NTC: n=82). In other words, the dropout rate was 22.5% of the students (n=43).

As presented in Figure 2, students were expected to write a business letter to JEP during the lesson. In the context of the second research objective, these letters were used as measurement instrument. Therefore, the process of writing the business letters is made as standardized as possible. Students were, namely, given instructions about how to write a business letter (Figure 2). Additionally, templates were developed for both conditions, as a consequence the structure of the letters was fixed making them comparable. Regarding the content, there were three requirements: (1) indicate which advertisement is seen as contentious; (2) give some underpinned arguments; and (3) give advice to JEP about prohibiting or modifying the advertisement. In total, 133 business letters were written (TC: n=54; NTC: n=79). Because of time constraints in some classes, students started with reflecting on ethical advertising issues as a duo task in classroom, but had to fulfil individually their letter at home. When the letters of students belonging to one group were quite different, we analysed them separately. Thematic analysis was used to identify categories in both controversial advertisements and main arguments. First, to become familiar with the data, the letters were read and reread by the first author. The process of rereading the business letters allows to determine preliminary themes. Next, important text passages were highlighted and initial codes were assigned to these units of analysis. Through this iterative and bottom-up process, more general themes and sub-themes were gradually unveiled by grouping the different codes (Howitt, 2010).

3. Results

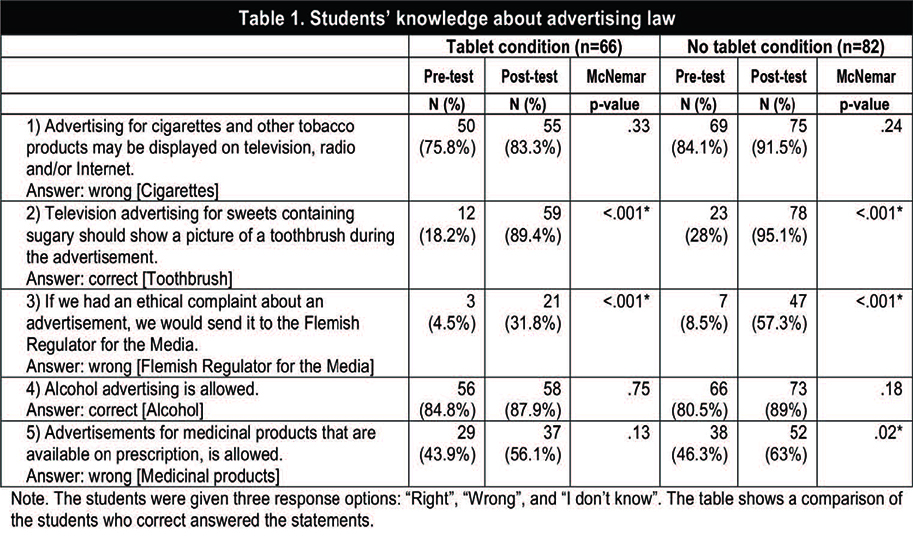

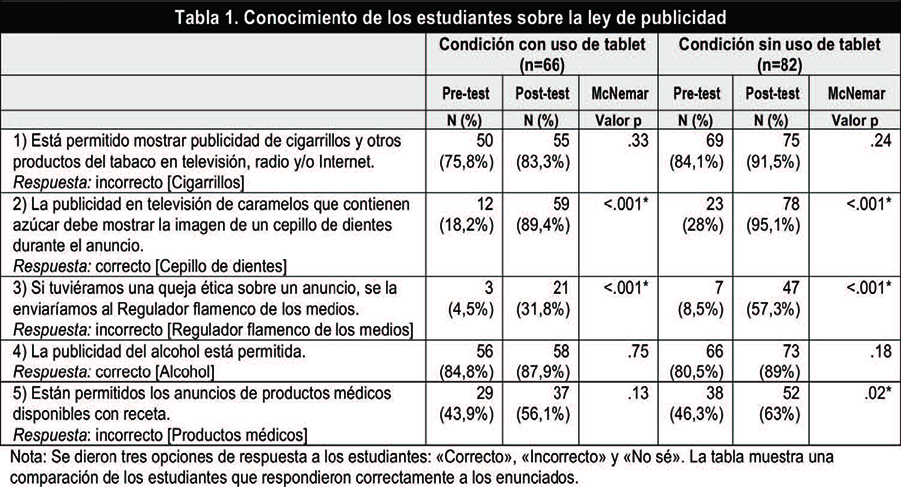

3.1. Does advertising literacy education lead to better knowledge about advertising law?

To determine whether the knowledge of students about Flemish advertising law increase after the intervention, students had to respond on five statements. For both conditions, the results obtained from the pre- and post-test were compared in Table 1. In the pretest, the majority of the students already knew some basic rules about advertisements on cigarettes and alcohol. However, descriptive data shows that all five statements were answered more correctly after the lesson. Nevertheless, students in the no tablet condition, who individually reflected on law-related topics before the class discussion, perform better in the post-test compared with students in the tablet condition who examined the subject matter in duo. McNemar's tests, moreover, revealed significant differences for two [toothbrush, Flemish Regulator for the Media] and three statements [toothbrush, Flemish Regulator for the Media, medicinal products] for the tablet and no tablet condition respectively.

From the data on students' perceptions about the use of tablets, we can see that many students (89.4%) did not have any experience with tablet devices in an educational context. Although most students in the tablet condition (83.4%) argued that the lessons about advertising were better than other lessons due to the tablet devices, 60.6% of the students admitted that they have not learned as much as in other lessons.

3.2. Which advertisements were judged as controversial by adolescents?3.2.1. Which advertisements are seen as controversial in the business letters of both conditions?

In the tablet condition, students actively searched for a contentious advertisement on the Internet. The chosen advertisements can be divided into five main themes, namely (1) sexist images (e.g., nudity) (n=26), (2) sexual stereotypes (e.g., the stereotypical ideal of feminine beauty) (n=23), (3) discrimination (e.g., with respect to well-rounded persons, immigrants, etc.) (n=18), (4) violent (e.g., gunman) (n=5), and (5) unhealthy food (e.g., soft drinks) (n=8). An important remark is that 18 of the 54 letters belonged to more than one theme. The most common combination is 'sexually oriented ' beauty ideal' (n=14).

In the no tablet condition, eight controversial advertisements 'about which JEP or similar foreign organisations recently received complaints' were integrated into the learning material. Students generally considered the first advertisement of Appendix 1 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.4789189) 'including a beauty ideal and nudity' as most controversial (n=24). In addition, 21 and 11 letters were respectively written about an advertisement of a Flemish clothing chain that promotes plastic surgery (Advertisement 2, Appendix 1) and an advertisement of a clothing brand in which an appeal is made to a very skinny model (Advertisement 4, Appendix 1). Both advertisements referred to beauty ideals. To a lesser extent, the remaining five advertisements were seen as contentious by students: Alcohol advertisement on Facebook (n=3), the use of Photoshop (n=6), deception in advertisements for smartphones (n=3), an unsafe situation - namely a model on a railway (n=7), and a sexually oriented advertisement of a perfume brand (n=4). Nevertheless, we surmise that students of the no tablet condition did not always find the advertisement they had in mind. Of the 82 students, 52 reported that the option to search for an advertisement via Internet would be interesting, instead of choosing one integrated in the learning material.

Across both conditions, as shown in Appendix 2 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.4789405), there are a number of recurrent arguments given for different advertisements. First, the argument that an advertisement is not suitable for children or youngsters was found in several business letters. Regarding a violent advertisement for an amusement park at Halloween time, a student group wrote down: 'I find it too scary, certainly for an amusement park where children come. If children see this on television, they probably cannot sleep at night' (BL_Q1_TC). Closely related, in various letters, students stated that a bad role model was shown: 'It is unjustifiable that a 14-year-old sits on a railway in a mournful mood. This is a bad example for other young people' (BL_W3_Advertisement 5, Appendix 1). In addition, students frequently referred to the consequences of advertisements. Because the use of stereotypical beauty ideals in advertisements was often seen as controversial, students repeatedly pointed to their possible effects on the self-image of especially adolescent girls or the desire to lose weight possibly resulting in eating disorders: 'They use in this advertisement the quote 'perfect body', however, there are not many people who can have such a body. [&] and therefore want to diet more and more, and will develop an eating disorder and receive health problems' (BL_M2_TC).

Thirdly, the reason that there is no link between the product and the advertisement was mentioned by the students. Neither do students tolerate too much nudity in advertisements. Both arguments are combined in the following quote: 'Naked women really have nothing to do with sport shoes' (BL_C4_ Advertisement 1, Appendix 1). Finally, the argument 'insult' is frequently given by students in the tablet condition (TC: 31.5%; NTC: 10.1%), and the argument 'deception' is more found in letters of student groups in the no tablet condition (TC: 1.5%; NTC: 22%). In only one business letter of the tablet condition (category: unhealthy food), the argument 'deception' is mentioned: 'These hamburgers look delicious and large at the picture, until you see them in real' (BL_K2_TC).

3.2.2. What are students' opinions about nudity in advertisements and alcohol advertising before and after the lesson?

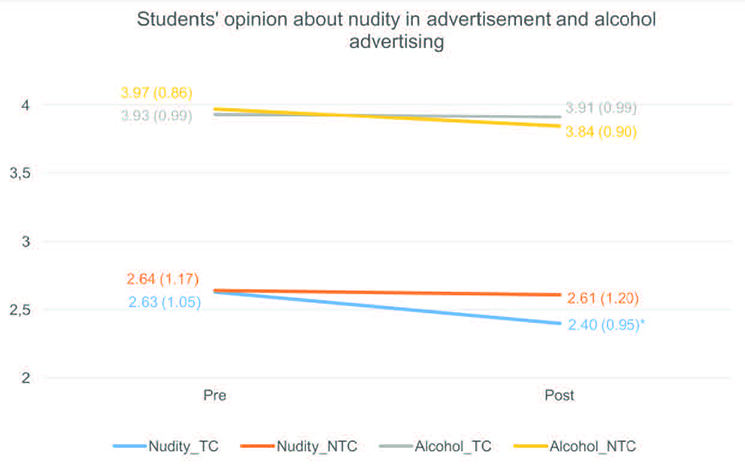

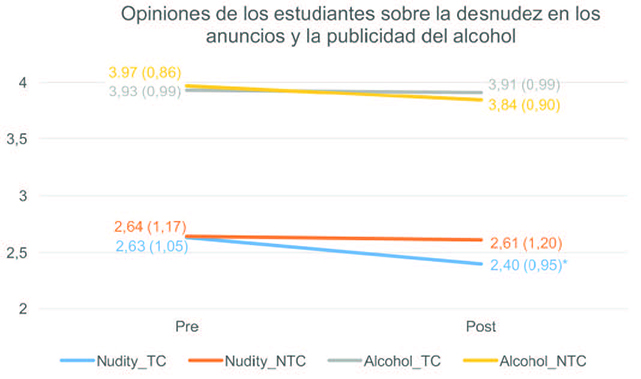

To explore whether students' critical thinking can change through advertising literacy education, two controversial advertisements (Figure 3) were integrated into the pre- and post-test. In general, as presented in Figure 4, students are more critical about nudity in advertisements than alcohol advertising on Facebook.

Regarding students' answers on the IMI-scale for the advertisement that includes naked models, the paired sample t-test showed a significant difference between the pre- and post-test results of students in the tablet condition [t(65)=2.36, p=.02, Cohen's d=0.29], and not for the no tablet condition [t(81)=0.34, p=.73]. To explain this significant effect, students' reactions on the open question of the post-test 'Why is this advertisement (not) acceptable for you?' were analysed. On average, it is remarkable that students in the no tablet condition wrote down more arguments (M=1.26; SD=0.66) compared to students in the tablet condition (M=1.18; SD=0.58). However, whereas students in the no tablet condition gave more general answers as 'too naked' (TC=36.4%; NTC=40.2%), the arguments of students in the tablet condition were more underpinned. They labelled the advertisement more as unacceptable for reasons as 'no link between the advertisement and clothing store' (TC=25.8%; NTC=19.5%), 'not suitable for children and youngsters' (TC=16.7%; NTC=13.4%), and 'models with an ideal female body' (TC=15.2%; NTC=9.8%). Furthermore, more students in the no tablet condition agreed with this advertisement, predominantly because the main parts are shielded through black cubes (TC=4.5%; NTC=13.4%).

As illustrated in Figure 4, most students accepted the Facebook advertisement about alcohol. Although descriptive data uncovered, especially for the no tablet condition, a more critical attitude towards this specific advertisement after the lesson, the paired sample t-test did not show significant differences between the pre- and post-test results of students in the tablet condition [t(65)=0.16, p=.87] and no tablet condition [t(81)=1.59, p=.12]. In the post-test, proponents often generally answered the open question with reactions as 'I find this advertisement acceptable, there is nothing wrong shown' (TC=33.3%; NTC: 31.7%). In addition, the argument that it is a humorous and smart idea of advertisers to integrate a competitive element was regularly given (TC=22.7%; NTC= 23.2%). Nevertheless, the latter was also seen as negative by opponents (TC=3%; NTC=9.8%): 'I find this advertisement a form of blackmail because they can only win if they buy the drink' (Student 17_NTC). Other arguments of students who find the advertisement unacceptable are: (1) encouragement to drink alcohol (TC=21.2%; NTC= 17.1%); (2) not suitable for children and youngsters (TC=13.6%; NTC=14.6%), including one explicit reference to the display of this advertisement on Facebook that is frequently used by youngsters, and (3) disagreement with alcohol advertising (TC=7.6%; NTC=11%). Besides, students learned during the lesson that alcohol advertising is only allowed under strict conditions. For example, neither a direct address to minors nor a link between using alcohol and improved performances or a calming effect is permissible. Despite the integration of this subject matter, only four students (TC: n=2; NTC: n=2) explicitly referred to law aspects in the post-test. A clarifying quote: 'Only adults take part in this commercial and nobody drives with a car. I think it is an appropriate advertisement' (Student 92_TC).

4. Discussion and conclusion

Nowadays, enhancing minors' advertising literacy is becoming more important due to the growing number of new advertising formats (Daems & De-Pelsmacker, 2015). During the past decades, advertising literacy programmes have already been developed (Meeus & al., 2014). However, Rozendaal and colleagues (2011) indicated that existing educational programmes mainly emphasize the cognitive dimension (i.e., recognizing several advertising formats, understanding persuasive tactics, etc.). In the context of this study, learning material aimed at enhancing adolescents' moral advertising literacy (i.e., moral judgement of advertising formats, tactics and messages) is developed. In line with research of Martinson (2001), who refers to the difference between advertising law and ethical issues in advertisements, this learning material is divided into two parts. The first part is about Flemish advertising law (Flemish Regulator for the Media, 2009), from the perspective that its (implicitly) influencing one's perceptions about the appropriateness of advertising (Hudders & al., 2015; Martinson, 2001). In the second part, attention is paid to ethical advertising concerns (De-Pelsmacker, 2016).

An initial objective of this intervention study is identifying whether advertising literacy education leads to better knowledge about advertising law. The results show that students know more about advertising law after the lesson. Nevertheless, students in the no tablet condition, who individually reflected on law-related topics before the class discussion led by the teacher, seem to learn more than students in the tablet condition who processed the learning content in duo via a tablet application. A possible explanation is found in data about students' perceptions on using tablet devices in education. Although most students in the tablet condition perceived the advertising lesson more enjoyable than other lessons, they realize that it had a negative effect on their learning performances. This result is in accord with a study of Montrieux and colleagues (2015) indicating that students, aside from recognizing the added value of using tablet devices in an educational setting, also admit that their learning capacity has not increased as well as that tablet devices cause distractions.

The second research objective is twofold, namely (a) revealing which advertisements are labelled as contentious by adolescents, and (b) uncovering adolescents' moral judgement of nudity/feminine beauty in advertisements and alcohol advertisements before and after the course. Regarding the first part (RO2a), we analysed students' fictive business letters to the Jury for Ethical Practices in Advertising (JEP) about a self-chosen controversial advertisement. In both conditions, advertisements containing sexual stereotypes and nudity are especially selected. Because of a significant effect, we can assume that students of the tablet condition have a more critical attitude towards feminine beauty/nudity in advertisements after the intervention (RO2b). The significant effect could be attributed to the way students choose a controversial advertisement. As observed in classrooms, the student groups in this condition immediately talked about nudity and feminine beauty in advertisements after hearing the task (i.e. collaborative learning). They actively looked for such advertisements, confronting them probably with a number of examples and (newspaper) articles including arguments against such advertisements (i.e. active and authentic learning). Next to feminine beauty and nudity in advertisements, students of the tablet condition do not tolerate discrimination and violent as well as advertisements about unhealthy food. In the no tablet condition, elements as using Photoshop and depicting an unsafe situation are also seen as contentious. Notwithstanding, we can surmise that students in the no tablet condition did not always find the advertisement they had in mind, because most of them reported that the option to search for an advertisement via Internet would be interesting.

Across the various controversial advertisements, students in both conditions justify their choice with similar arguments in their business letters. To start with, there is repeatedly referred to consequences of advertisements. In case of sexual stereotypes in advertisements, students often refer to the possible negative effects for adolescent girls' self-image and the desire to lose weight. Consequently, adolescents are aware of these effects which are also confirmed by prior studies (e.g., Grabe, Ward, & Hyde, 2008; Levine & Murnen, 2009). More than once, students also refer to the following arguments: (1) not suitable for children or youngsters, (2) no link between the product and the advertisement, (3) nudity, and (4) insult and deception. Insult is more mentioned by students in the tablet condition, especially in business letters written about discriminatory advertisements. Deception is particularly raised in the no tablet condition, probably because more examples of misleading advertisements were provided in the learning material of this condition. Hence, students select misleading advertisements when it is offered, but they are not consciously looking for it. Therefore, an important issue for future research is providing different categories of controversial advertisements and their consequences, allowing students to get acquainted with and to think critically about a variety of ethical matters in advertisements. For example, it is advisable to pay more attention to alcohol advertising. As indicated by Martino and colleagues (2016), adolescents seem to be accustomed to the presence of alcohol advertisements. Despite the incorporation of learning content about this matter, students in both conditions scarcely refer to alcohol advertising in their business letters (RO2a). Based on pre- and post-test findings (RO2b), this study does not show any significant increase in adolescents' critical attitudes towards alcohol advertising. Since previous research (Ellickson & al., 2005; Scull & al., 2010) demonstrated that a critical attitude and alcohol advertising deconstruction skills decrease negative effects of such advertisements, further research is required to explore educational interventions that can anticipate on this. The same applies to critical thinking about new hidden and interactive advertising formats. In other words, in contrast to judging an advertisement because of the format, students chose advertisements based on substantive issues.

A note of caution is necessary, because of the gender bias of the sample. Since the participating classes predominantly include female students, future research needs to be conducted in gender-balanced classes to discover whether the same advertisements were seen as contentious and whether the same underpinned arguments were provided. In addition, the findings of this study may be somewhat limited by measuring students' opinion through both business letters and a pre- and post-test. Unfortunately, some student responses are rather superficial. For that reason, it can be suggested that additional in-depth interviews with students would be a good alternative to get more insight into their moral judgement of unethical advertisements before and after the lessons.

As a conclusion, it can be stated that the lesson aimed at enhancing youngsters' moral advertising literacy is effective in raising knowledge about advertising law. In addition, students were challenged to think critically about contentious advertisements, and to provide underpinned arguments for these advertisements. Nevertheless, this study shows that more research is needed to reveal appropriate class exercises to encourage students' moral judgement of various unethical themes in advertisements.

References

Adams, B., Schellens, T., & Valcke, M. (2015). Een analyse van het Vlaamse onderwijscurriculum anno 2015. In welke mate is reclamewijsheid aanwezig in het curriculum? [An Analysis of the Flemish Curriculum Anno 2015. To What Extent is Advertising Literacy Present in the Curriculum?]. (https://goo.gl/L8EmjJ) (2016-04-28).

Aguaded, I. (2011). Media Education: An International Unstoppable Phenomenon UN, Europe and Spain Support for Edu-communication [La educación mediática, un movimiento internacional imparable. La ONU, Europa y España apuestan por la educomunicación]. Comunicar, 37, 7-8. https://doi.org/10.3916/C37-2011-01-01

Aguaded, I. (2013). Media Programme (UE) - International Support for Media Education. [El Programa «Media» de la Comisión Europea, apoyo internacional a la educación en medios]. Comunicar, 40, 07-08. https://doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-01-01

Anderson, P., de-Bruijn, A., Angus, K., Gordon, R., & Hastings, G. (2009). Impact of Alcohol Advertising and Media Exposure on Adolescent Alcohol Use: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Alcohol & Alcoholism, 44(3), 229-243. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agn115

Apestaartjaren (2016). Onderzoeksrapport Apestaartjaren 6 [Research report Apestaartjaren 6]. (https://goo.gl/GOIx4U) (2016-10-03).

Calvert, S.L. (2008). Children as Consumers: Advertising and Marketing. The Future of Children, 18(1), 205-234. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.0.0001

Daems, K., & De-Pelsmacker, P. (2015). Marketing Communication Techniques Aimed at Children and Teenagers. (https://goo.gl/L8EmjJ) (2016-04-28).

De-Pelsmacker, P. (2016). Ethiek in reclame [Ethics in Advertising] [PowerPoint Slides]. (https://goo.gl/Zu6vWo) (2016-11-20).

Duffy, T.M., & Cunningham, D.J. (1996). Constructivism: Implications for the Design and Delivery of Instruction. In D.J. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research for Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 170-198). New York: Macmillan Library Reference.

Ellickson, P.H., Collins, R.L., Hambarsoomians, K., & McCaffrey, D.F. (2005). Does Alcohol Advertising Promote Adolescent Drinking? Results from a longitudinal assessment. Addiction, 100(2), 235-246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00974.x

Howitt, D. (2010). Thematic Analysis. In G. Van-Hove, & L. Claes (Eds.), Qualitative Research and Educational Sciences: A Reader about Useful Strategies and Tools (pp. 179-202). Essex: Pearson.

Hudders, L, Cauberghe, V., Panic, K., Adams, B., Daems, K., De-Pauw, P., &, Zarouali, B. (2015, February). Children's Advertising Literacy in a New Media Environment: An Introduction to the AdLit Research Project. Paper presented at the Etmaal van de Communicatiewetenschap. (https://goo.gl/JLEvuc) (2016-04-28).

Karagiorgi, Y, & Symeou, L. (2005). Translating Constructivism into Instructional Design: Potential and Limitations. Educational Technology & Society, 8(1), 17-27.

Lavine, H., Sweeney, D., & Wagner, S.H. (1999). Depicting Women as Sex Objects in Television Advertising: Effects on Body Dissatisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(8), 1049-1058. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672992511012

Levine, M.P., & Murnen, S.K. (2009). Everybody Knows that Mass Media Are/Are Not [pick one] a Cause of Eating Disorders: A Critical Review of Evidence for a Causal Link between Media, Negative Body Image, and Disordered Eating in Females. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28(1), 9-42. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2009.28.1.9

Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E.J. (2006). Does Advertising Literacy Mediate the Effects of Advertising on Children? A Critical Examination of Two Linked Research Literatures in Relation to Obesity and Food choice. Journal of Communication, 56(3), 560-584. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00301.x

Martino, S.C., Kovalchik, S.A., Collins, R.L., Becker, K.M., Shadel, W.G., & D'Amico, E.J. (2016). Ecological Momentary Assessment of the Association between exposure to Alcohol Advertising and Early Adolescents' Beliefs about Alcohol. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(1), 85-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.08.010

Martinson, D.L. (2001). Using Commercial Advertising to Build an Understanding of Ethical Behaviour. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 74(3), 131-135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098650109599178

McLean, S.A., Paxton, S.J., & Wertheim, E.H. (2016). Does Media Literacy Mitigate Risk for Reduced Body Satisfaction Following Exposure to Thin-ideal Media? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 1678-1695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0440-3

Meeus, W., Walrave, M., Van-Ouytsel, J., & Driesen, A. (2014). Advertising Literacy in Schools: Evaluating Free Online Educational Resources for Advertising Literacy. Journal of Media Education, 5(2), 5-12.

Montrieux, H., Vanderlinde, R., Schellens, T., & De-Marez, L. (2015). Teaching and Learning with Mobile Technology: A Qualitative Explorative Study about the Introduction of Tablet Devices in Secondary Education. PLoS ONE, 10(12), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144008

Rozendaal, E., Lapierre, M.A., Van-Reijmersdal, E.A., & Buijzen, M. (2011). Reconsidering Advertising Literacy as a Defense against Advertising Effects. Media Psychology, 14(4), 333-354. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2011.620540

Scull, T. M., Kupersmidt, J.B., Parker, A.E., Elmore, K.C., & Benson, J.W. (2010). Adolescents' Media-Related Cognitions and Substance Use in the Context of Parental and Peer Influences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(9), 981-998. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9455-3

Slater, A., Tiggemann, M., Hawkins, K., & Werchon, D. (2012). Just One Click: A Content Analysis of Advertisements on Teen Web Sites. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(4), 339-345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.08.003

Tortajada, I., Araüna, N., & Martínez, I.J. (2013). Advertising Stereotypes and Gender Representation in Social Networking Sites. [Estereotipos publicitarios y representaciones de género en las redes sociales]. Comunicar, 41(XXI), 177-186. https://doi.org/10.3916/C41-2013-17

Vanderhoven, E. (2014). Raising Risk Awareness and Changing Unsafe Behavior on Social Network Sites: A Design-based Research in Secondary Education (Doctoral Dissertation). Ghent: Ghent University.

Verdoodt, V., Lievens, E., & Hellemans, L. (2015). Mapping and Analysis of the Current Legal Framework of Advertising Aimed at Minors. (https://goo.gl/L8EmjJ) (2015-09-13).

Vlaamse Regulator voor de Media [Flemish Regulator for the Media]. (2009). Decreet betreffende radio-omroep en televisie. [Decree on Radio and Television Broadcasting]. (https://goo.gl/FqMdFU) (2015-09-13).

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Los menores de edad se enfrentan diariamente a anuncios que pueden resultar polémicos. Con el fin de promover la alfabetización ética en publicidad en los adolescentes, este estudio explora cómo estimular el conocimiento de los estudiantes de Educación Secundaria acerca de la ley de publicidad y su juicio moral hacia los anuncios. A raíz de los formatos de publicidad ?especialmente online– que han surgido en los últimos años, 191 estudiantes de 12 clases fueron asignados aleatoriamente a una de estas condiciones: uso o no uso de tablets (para aumentar la autenticidad del material de aprendizaje). Los resultados muestran que el desempeño en el post-test sobre la ley de publicidad de los estudiantes que usaron tablet es peor. En cuanto al juicio moral de los adolescentes sobre los anuncios, el análisis temático revela que especialmente el uso de la desnudez y la belleza femenina resultan polémicos en ambas condiciones, debido, entre otros motivos, a los efectos negativos para la autoestima de las adolescentes y al deseo de perder peso. Tras la intervención, el uso de tablets ha demostrado ser más eficaz para promover el pensamiento crítico hacia la desnudez y la belleza femenina en los anuncios. Sin embargo, no se hallaron evidencias de que alguna de las dos condiciones favorezca el desarrollo de una actitud crítica hacia la publicidad del alcohol. En este sentido, se plantean futuras líneas de investigación en el contexto de la alfabetización publicitaria.

1. Introducción

Actualmente, los niños y los jóvenes están expuestos a innumerables anuncios a través de diferentes medios (Hudders & al., 2015). A raíz de los avances tecnológicos, se han creado muchos nuevos formatos publicitarios (principalmente online), como la publicidad en las redes sociales, por ejemplo, páginas de marca en Facebook (Daems & De-Pelsmacker, 2015). Debido a estos cambios en el panorama de la publicidad, aumenta la importancia de promover la alfabetización en publicidad de los menores de edad (Hudders & al., 2015). La confrontación con nuevas formas de medios requiere un nuevo conjunto de habilidades para acceder a las imágenes, el sonido y el texto, así como para analizarlos y evaluarlos (Aguaded, 2013). Por consiguiente, en general es posible definir la alfabetización en publicidad como «las habilidades de analizar, evaluar y crear mensajes persuasivos en una diversidad de contextos y medios» (Livingstone & Helsper, 2006: 562). Más en concreto, como se ilustra en la Figura 1, pueden distinguirse tres dimensiones de la alfabetización en publicidad.

Como afirmó Aguaded (2011: 7): «la ciudadanía [...] ha de organizarse cada vez más en asociaciones, colectivos y grupos para vertebrar una ciudadanía responsable, crítica y constructora de un futuro donde los medios tienen presencia omnipresente y casi omnipotente». Por este motivo, se ha subrayado en repetidas ocasiones el papel de la educación para desarrollar la alfabetización en publicidad de los menores (Calvert, 2008; Livingstone & Helsper, 2006). Si bien ya se han desarrollado algunos programas de alfabetización en publicidad durante las últimas décadas, como Media Smart, Rozendaal, Lapierre, Van-Reijmersdal y Buijzden (2011) abogan por reformular su enfoque, ya que, en el pasado, se hacía hincapié sobre todo en la dimensión cognitiva (Figura 1). No obstante, falta evidencia de que la alfabetización cognitiva en publicidad sea suficiente para disminuir la susceptibilidad de los menores a los efectos de los anuncios (Rozendaal & al., 2011).

1.1. Alfabetización ética en publicidad: ¿ley frente a ética?

Como se muestra en la Figura 1, se espera que el marco normativo de un país –incluidas las normas para los anunciantes– repercuta implícitamente en las percepciones que se tienen sobre la adecuación de la publicidad (Hudders & al., 2015; Martinson, 2001). En Flandes se ha elaborado un Decreto sobre los Medios (Vlaamse Regulator voor de Media [Regulador flamenco de los medios], 2009; Verdoodt, Lievens, & Hellemans, 2015) con requisitos tanto generales como específicos de algunos productos, como el alcohol o los productos médicos, en relación con la publicidad (dirigida a menores). Además del conocimiento relativo a la legislación, «en la ética, la cuestión no es si uno puede hacer algo o si la ley le permite hacerlo. La ética asume que, dentro del individuo, existe una capacidad potencial de discernir entre lo correcto y lo que no lo es» (Martinson, 2001: 132). La educación se enfrenta al desafío de alertar a los estudiantes de la importancia de la ética en su vida diaria, puesto que afecta a nuestro comportamiento y actitudes (Martinson, 2001). Como señaló De-Pelsmacker (2016), existen varias categorías relativas a las preocupaciones éticas en la publicidad. Junto al insulto y el engaño, otro ejemplo es el empleo de estereotipos sexistas. Por ejemplo, la norma contemporánea de belleza femenina (a saber, alta, tamaño de pecho moderado y extremadamente delgada) es fomentada por los cuerpos ideales de las modelos de los anuncios (Lavine, Sweeney, & Wagner, 1999). No solo los anuncios difundidos a través de los canales tradicionales, como la televisión y las revistas, contienen imágenes estereotipadas de género (Lavine & al., 1999), sino que esta tendencia se perpetúa en la publicidad en Internet, incluso en los sitios web para adolescentes (Slater, Tiggemann, Hawkins, & Werchon, 2012). En consecuencia, dado que los adolescentes copian a los modelos de los anuncios en sus fotos en las redes sociales, Tortajada, Araüna y Martínez (2013) hacen referencia a la interiorización de las representaciones socialmente construidas de la feminidad. Además, investigaciones anteriores (Grabe, Ward & Hyde, 2008; Levine & Murnen, 2009) revelaron que las imágenes estereotipadas en los anuncios se corresponden con el ansia de delgadez, la insatisfacción corporal y los patrones de trastornos alimentarios de las chicas adolescentes. Asimismo, la importancia de la alfabetización publicitaria es demostrada por McLean, Paxton y Wertheim (2016), las cuales observaron que las adolescentes con habilidades de pensamiento crítico reducidas sufren un efecto más negativo al ver un ideal de belleza femenina en los anuncios.

También existen cuestiones éticas en relación con anuncios de algunos productos en concreto, como la publicidad del alcohol (Anderson, de-Bruijn, Angus, Gordon, & Hastings, 2009; Ellickson, Collins, Hambarsoomians, & McCaffrey, 2005). Anderson y colaboradores (2009) pusieron de manifiesto que la confrontación con la publicidad del alcohol se relaciona con el inicio del consumo de alcohol por parte de los adolescentes y con un mayor nivel de consumo entre los adolescentes que ya tomaban alcohol. Adicionalmente, debido a la publicidad del alcohol, los adolescentes perciben más favorablemente a los pares que toman alcohol y consideran el consumo de alcohol más conforme a la norma (Martino, Kovalchik, Collins, Becker, Shadel, & D’Amico, 2016). A este respecto, la alfabetización publicitaria también se recomienda porque las habilidades de pensamiento crítico y de deconstrucción de la publicidad del alcohol disminuyen no solo la intención de los adolescentes de consumir alcohol, sino también su susceptibilidad a la atracción persuasiva de esta publicidad (Ellickson & al., 2005; Scull, Kupersmidt, Parker, Elmore, & Benson, 2010).

En los últimos años, han surgido cuestiones éticas sobre los nuevos formatos publicitarios que esperan cada vez más una participación activa por parte de los consumidores, como el botón «Me gusta» de Facebook en las páginas de marca, y a menudo integran contenido comercial en contenido de comunicación. Esto último se observa en formatos publicitarios como el emplazamiento de producto o «product placement», es decir, la integración de marcas en películas, series de televisión, etc. (De-Pelsmacker, 2016). Estas características de los nuevos formatos publicitarios dificultan más que los niños y los jóvenes detecten los mensajes comerciales (Hudders & al., 2015).

1.2. El constructivismo como base

Para mejorar la alfabetización ética en publicidad de los adolescentes, se ha desarrollado material de aprendizaje en el contexto de este estudio. Para este fin se tomó el constructivismo –una teoría de aprendizaje que se dio a conocer ampliamente en las últimas décadas– como punto de partida. El planteamiento del constructivismo se basa en que el aprendizaje significativo puede considerarse un proceso activo de construcción de conocimiento. Se asume que el conocimiento es el resultado de las interpretaciones personales, influidas por el género, la edad, el conocimiento anterior, el origen étnico, etc., del alumno. Al compartir múltiples perspectivas, los individuos pueden adaptar sus opiniones personales (Duffy & Cunningham, 1996; Karagiorgi & Symeou, 2005). En esta intervención, se presta atención a principios constructivistas tales como el aprendizaje colaborativo, el aprendizaje auténtico y el aprendizaje activo. Según el primer principio, el material de aprendizaje incluye oportunidades para debatir múltiples perspectivas sobre anuncios polémicos. Adicionalmente, los principios de aprendizaje activo y aprendizaje auténtico asumen que los estudiantes reciben actividades de aprendizaje significativo en un contexto realista que les permite reflexionar sobre qué hacen, en lugar de recibir información pasivamente del profesor. Para asegurar la autenticidad, en esta intervención se utilizó tecnología debido a la cantidad creciente de nuevos formatos publicitarios online.

1.3. Finalidad del estudio

Hasta la fecha, la alfabetización publicitaria se ha centrado principalmente en la alfabetización cognitiva en publicidad (Rozendaal & al., 2011) y en los formatos publicitarios tradicionales (Meeus, Walrave, Van-Ouytsel, & Driesen, 2014). Por lo tanto, la finalidad del presente estudio de exploración consiste en determinar cómo se puede mejorar la alfabetización ética en publicidad de los adolescentes –es decir, el juicio moral sobre los formatos, las tácticas y los mensajes publicitarios–, lo cual está adquiriendo mayor importancia debido al aumento de nuevos formatos publicitarios.

El presente estudio tiene dos objetivos de investigación principales. En primer lugar, queremos determinar si la alfabetización publicitaria conduce a un mejor conocimiento de la ley de publicidad. En segundo lugar, este estudio proporciona la oportunidad de aumentar el conocimiento respecto al juicio moral de los adolescentes sobre los anuncios polémicos. Por consiguiente, el segundo objetivo de investigación es doble: 1) descubrir qué anuncios son calificados como polémicos por los adolescentes; 2) determinar si existe una diferencia entre el juicio moral de los estudiantes sobre la desnudez y la belleza femenina en los anuncios y sobre la publicidad del alcohol en Facebook tras una intervención educativa.

2. Metodología

2.1. Participantes

Se estableció un estudio de intervención en 12 clases (n=191) de los cursos 9º y 10º del sistema educativo flamenco. En concreto, las clases participantes formaban parte de la educación secundaria general. Se escogió este grupo sobre la base de un análisis de los estándares sobre los planes de estudio (Adams, Schellens, & Valcke, 2015).

Los estudiantes tenían edades comprendidas entre los 14 y los 18 años (M=15,42; SD=0,67), y eran principalmente chicas (81%). A pesar de que intervinieron 12 clases, solo participaron nueve profesores porque tres de ellos eran responsables de la asignatura en dos clases del mismo colegio. Se obtuvo el consentimiento informado de todos los profesores. Además, se hizo llegar a los padres de los adolescentes una carta que incluía información sobre el estudio y la opción de negarse a participar.

2.2. Diseño y procedimiento

Las clases participantes se dividieron aleatoriamente en dos condiciones: una con uso y otra sin uso de tablets. La Figura 2 muestra una descripción detallada del material de aprendizaje utilizado en la condición con tablet (TC) y en la condición sin tablet (NTC).

Dado que Vanderhoven y colaboradores (2014) muestran que un curso de alfabetización en medios de una hora podría ser eficaz, optamos conscientemente por una intervención de corta duración. Para asegurar la validez externa, la intervención se llevó a cabo en un entorno de aula real. Dado que el profesor habitual impartía la clase, se desarrolló un manual con información general sobre la publicidad e instrucciones detalladas sobre cómo impartir la lección. La primera autora de este artículo verificó que la lección se impartiese según lo establecido.

2.3. Mediciones y análisis

Tal como se muestra en la Figura 2, se utilizaron un pre-test y un post-test para descubrir los efectos de la alfabetización publicitaria en el conocimiento de los estudiantes sobre la ley de publicidad y en su juicio moral sobre anuncios polémicos. Los estudiantes recibieron el pre-test y el post-test unos días antes de la intervención e inmediatamente después, respectivamente, a través de un enlace online que tenían que rellenar en casa. Por un lado, estos test incluían cinco enunciados verdadero/falso (véase la tabla 1) sobre temas relacionados con la ley que se habían tratado durante la lección. Por otro lado, se mostraron dos anuncios polémicos a los estudiantes para explorar si su pensamiento crítico puede cambiar mediante la alfabetización publicitaria (Figura 3).

La primera imagen es un anuncio de televisión de una cadena de tiendas flamenca que fue calificado como provocador en 2013 debido a los modelos de belleza femenina y a la desnudez. La segunda imagen correspondía a un anuncio de alcohol de un nuevo tipo de cerveza en Facebook. En este mensaje se proponía hacerse un selfie que se pareciese a la imagen representada para ganar una entrada a «la fiesta de tus sueños» o un «pack Edición Limitada» de esta cerveza. Debido a las estrictas normas que existen en Flandes sobre los anuncios de alcohol dirigidos a menores (Vlaamse Regulator voor de Media [Regulador flamenco de los medios], 2009), se plantean cuestiones éticas en relación con los anuncios de alcohol en Facebook, que sigue siendo la red social más utilizada por los adolescentes flamencos (Apestaartjaren, 2016). Las opiniones de los estudiantes se midieron mediante la Escala de inferencia de intención manipuladora (IMI) (Campbell, 1995) y una pregunta abierta. Originalmente, la escala IMI se compone de seis ítems (alfa de Cronbach=0,93), que en este estudio se redujeron a cuatro por motivos lingüísticos. Por ejemplo, uno de los ítems de la IMI es: «El anunciante intentó manipular al público con formas que no me gustan». Los elementos se calificaron según una escala de Likert de 6 puntos (1 totalmente en desacuerdo; 6 totalmente de acuerdo). El análisis de fiabilidad generó un alfa de Cronbach aceptable (Desnudezpre=0,85; Desnudezpost=0,81; Alcoholpre=0,82; Alcoholpost=0,79). Los datos cuantitativos obtenidos en el pre-test y el post-test se analizaron utilizando el software de análisis estadístico SPSS. Los datos de la pregunta abierta («¿Por qué (no) es aceptable este anuncio para ti?») se procesaron mediante análisis temático (véase más abajo). En el post-test, los estudiantes también recibieron preguntas relacionadas con sus percepciones de la lección, como por ejemplo, «Aprendí más en las lecciones sobre anuncios que en otras lecciones gracias al uso de la tablet». Desgraciadamente, aunque se enviaron varios recordatorios a los estudiantes, 148 rellenaron completamente tanto el pre-test como el post-test (TC: n=66; NTC: n=82). La tasa de abandono, por lo tanto, ascendió a un 22,5% de los estudiantes (n=43).

Según se muestra en la Figura 2, los estudiantes debían escribir una carta formal dirigida a JEP durante la sesión de clase. En el contexto del segundo objetivo de investigación, estas cartas se utilizaron como instrumento de medición. Por lo tanto, el proceso de redactar las cartas formales se llevó a cabo de la forma más estandarizada posible. Para ello, los estudiantes recibieron instrucciones sobre cómo escribir una carta formal (Figura 2). Adicionalmente, se desarrollaron plantillas para las dos condiciones; por lo tanto, la estructura de las cartas era fija y permitía compararlas. En cuanto al contenido, los requisitos eran tres: 1) indicar qué anuncio se considera polémico; 2) aportar algunos argumentos fundamentados; y 3) aconsejar a JEP sobre la prohibición o la modificación del anuncio. En total, se escribieron 133 cartas (TC: n=54; NTC: n=79). A consecuencia de las limitaciones de tiempo en algunas clases, los estudiantes empezaron a reflexionar en parejas sobre cuestiones éticas de la publicidad en el aula, pero tuvieron que escribir la carta individualmente en casa. En los casos en los que las cartas de los estudiantes de un grupo eran muy distintas, las analizamos por separado. Se utilizó el análisis temático para identificar categorías tanto en los anuncios polémicos con en los argumentos principales. En primer lugar, a fin de familiarizarse con los datos, la primera autora leyó y releyó las cartas. El proceso de releer las cartas permitió determinar temas preliminares. A continuación, se subrayaron fragmentos importantes y se asignaron códigos iniciales a estas unidades de análisis. Mediante este proceso iterativo y ascendente, se fueron descubriendo paulatinamente temas más generales y subtemas al agrupar los diferentes códigos (Howitt, 2010).

3. Resultados

3.1. ¿Conduce la alfabetización publicitaria a un mejor conocimiento de la ley de publicidad?

Para determinar si el conocimiento de los estudiantes sobre la ley de publicidad flamenca había aumentado tras la intervención, los estudiantes tuvieron que responder a cinco enunciados. Los resultados obtenidos en el pre-test y el post-test por las dos condiciones se comparan en la tabla 1. En el pre-test, la mayoría de los estudiantes ya conocían algunas normas básicas sobre anuncios de cigarrillos y alcohol. Sin embargo, los datos descriptivos muestran que los cinco enunciados se respondieron más correctamente tras la lección. No obstante, los estudiantes que no usaron tablet y que reflexionaron individualmente sobre temas relacionados con la ley antes del debate en clase, obtuvieron mejores resultados en el post-test que los estudiantes que usaron tablet y examinaron el tema en parejas. Además, las pruebas de McNemar constataron diferencias significativas para dos [cepillo de dientes, Regulador flamenco de los medios] y tres enunciados [cepillo de dientes, Regulador flamenco de los medios, productos médicos] para la condición con uso de tablet y la condición sin uso de tablet, respectivamente.

A partir de los datos acerca de las percepciones de los estudiantes sobre el uso de tablets, podemos ver que muchos estudiantes (89,4%) no tenían experiencia con el uso de tablets en un contexto educativo. Aunque la mayoría de los estudiantes pertenecientes a la condición con uso de tablet (83,4%) sostuvieron que las lecciones sobre publicidad habían sido mejores que otras lecciones debido a las tablets, el 60,6% de los estudiantes admitieron que no habían aprendido tanto como en otras lecciones.

3.2. ¿Qué anuncios juzgaron como polémicos los adolescentes?3.2.1. ¿Qué anuncios se consideran polémicos en las cartas formales de las dos condiciones?

En la condición con uso de tablet, los estudiantes buscaron activamente un anuncio polémico en Internet. Los anuncios elegidos pueden dividirse en cinco temas principales: 1) Imágenes sexistas, por ejemplo: desnudez: n=26; 2) Estereotipos sexuales, por ejemplo: la idea estereotipada de belleza femenina: n=23; 3) Discriminación, por ejemplo: respecto a personas de formas redondeadas, inmigrantes, etc.: n=18; 4) Violentos, por ejemplo: pistolero: n=5; 5) Comida no saludable, por ejemplo: refrescos: n=8. Cabe señalar que 18 de las 54 cartas pertenecían a más de un tema. La combinación más común es ‘orientado sexualmente / ideal de belleza’: n=14.

En la condición sin uso de tablet, se integraron ocho anuncios polémicos –sobre los que JEP u organismos extranjeros similares habían recibido quejas recientemente– en el material de aprendizaje. En general, los estudiantes consideraron que el primer anuncio del Anexo 1 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.4789189), que incluía un ideal de belleza y desnudez, era el más polémico (n=24). Además, se redactaron 21 y 11 cartas, respectivamente, sobre un anuncio de una cadena de ropa flamenca que promueve la cirugía plástica (Anuncio 2, Anexo 1) y un anuncio de una marca de ropa que utiliza una modelo muy delgada (Anuncio 4, Anexo 1). En los dos anuncios se hizo referencia a los ideales de belleza. Los estudiantes consideraron polémicos los cinco anuncios restantes en menor grado: el anuncio de alcohol en Facebook (n=3); el uso de Photoshop (n=6); el engaño en los anuncios de smartphones (n=3); una situación insegura, concretamente, una modelo en una vía de tren (n=7); y un anuncio de una marca de perfume orientado sexualmente (n=4). No obstante, presumimos que los estudiantes que no usaron tablet no siempre encontraron el anuncio que tenían en mente. De los 82 estudiantes, 52 refirieron que sería interesante la opción de buscar un anuncio en Internet, en lugar de elegir uno integrado en el material de aprendizaje.

En las dos condiciones, tal como se muestra en el Anexo 2 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.4789405), aparece una serie de argumentos recurrentes aportados para anuncios distintos. En primer lugar, el argumento de que un anuncio no es adecuado para niños o jóvenes se encontró en varias cartas. En relación con un anuncio violento de un parque de atracciones en Halloween, un grupo de estudiantes escribió: «En mi opinión da demasiado miedo, sobre todo tratándose de un parque de atracciones a donde van niños. Si los niños ven esto en la televisión, probablemente no puedan dormir de noche» (BL_Q1_TC). En una línea estrechamente relacionada, en diversas cartas los estudiantes afirmaron que se mostraba un mal ejemplo: «Es injustificable que una persona de 14 años esté sentada en una vía con aire triste. Es un mal ejemplo para otra gente joven» (BL_W3_Anuncio 5, Anexo 1). Además, los estudiantes mencionaron con frecuencia las consecuencias de los anuncios. Dado que el empleo de ideales de belleza estereotipados en los anuncios se consideró polémico a menudo, los estudiantes señalaron reiteradamente sus posibles efectos en la propia imagen, sobre todo de las adolescentes, o en el deseo de perder peso, que puede desembocar en trastornos alimentarios: «En este anuncio utilizan la frase “cuerpo perfecto”, sin embargo, no hay muchas personas que puedan tener ese cuerpo. [...] y, por lo tanto, quieren adelgazar cada vez más, y desarrollarán un trastorno alimentario y tendrán problemas de salud» (BL_M2_TC).

En tercer lugar, los estudiantes citaron el motivo de que no hay relación entre el producto y el anuncio. Los estudiantes tampoco toleran demasiada desnudez en los anuncios. Estos dos argumentos se combinan en la frase siguiente: «Las mujeres desnudas en realidad no tienen nada que ver con las zapatillas deportivas»·(BL_C4_ Anuncio 1, Anexo 1). Por último, los estudiantes que usaron tablet dieron con frecuencia el argumento «insulto» (TC: 31,5%; NTC: 10,1%), mientras que el argumento «engaño» se encuentra más en las cartas de los grupos de estudiantes que no usaron tablet (TC: 1,5%; NTC: 22%). Solo en una carta de la condición con uso de tablet (categoría: comida no saludable) se menciona el argumento «engaño»: «Estas hamburguesas parecen deliciosas y grandes en la imagen, hasta que las ves en la realidad» (BL_K2_TC).

3.2.2. ¿Cuáles son las opiniones de los estudiantes sobre la desnudez en los anuncios y sobre la publicidad del alcohol antes y después de la lección?

A fin de explorar si el pensamiento crítico de los estudiantes puede cambiar mediante la alfabetización publicitaria, se integraron dos anuncios polémicos (Figura 3) en el pre-test y el post-test. En general, como se ilustra en la Figura 4, los estudiantes son más críticos respecto a la desnudez en los anuncios que a la publicidad del alcohol en Facebook.

En lo que respecta a las respuestas de los estudiantes en la escala de IMI sobre el anuncio que incluye modelos desnudas, la prueba t para muestras relacionadas arrojó una diferencia significativa entre los resultados pre-test y post-test de los estudiantes que usaron tablet [t(65)=2,36, p=.02, d de Cohen=0,29] y los que no usaron tablet [t(81)=0,34, p=.73]. Para explicar este efecto significativo, se analizaron las reacciones de los estudiantes a la pregunta abierta del post-test: «¿Por qué (no) es aceptable este anuncio para ti?». Por término medio, cabe destacar que los estudiantes que no usaron tablet anotaron más argumentos (M=1,26; SD=0,66) que los estudiantes que usaron tablet (M=1,18; SD=0,58). No obstante, mientras que los estudiantes que no usaron tablet dieron respuestas más generales, como «demasiado desnuda» (TC=36,4%; NTC=40,2%), los argumentos de los estudiantes que usaron tablet estaban más fundamentados. Calificaron el anuncio como inaceptable más por motivos como «ninguna relación entre el anuncio y la tienda de ropa» (TC=25,8%; NTC=19,5%), «inadecuado para niños y jóvenes» (TC=16,7%; NTC=13,4%), y «modelos con un cuerpo femenino ideal» (TC=15,2%; NTC=9,8%). Además, más estudiantes de la condición sin uso de tablet se mostraron de acuerdo con este anuncio, sobre todo porque las partes principales están cubiertas por recuadros negros (TC=4,5%; NTC=13,4%). Tal como se ilustra en la Figura 4, la mayoría de los estudiantes aceptaron el anuncio de Facebook sobre el alcohol. Si bien los datos descriptivos revelaron, sobre todo en la condición sin uso de tablet, una actitud más crítica hacia este anuncio en concreto tras la lección, la prueba t para muestras relacionadas no arrojó diferencias significativas entre los resultados del pre-test y el post-test de los estudiantes que usaron tablet [t(65)=0,16, p=.87] y los que no [t(81)=1,59, p=.12].

En el post-test, los partidarios por lo general respondieron a la pregunta abierta con reacciones como «Este anuncio me parece aceptable, no hay nada malo en lo que muestra» (TC=33,3%; NTC: 31,7%). Además, se mencionó regularmente el argumento de que es una idea divertida e inteligente de los anunciantes integrar un elemento competitivo (TC=22,7%; NTC=23,2%). No obstante, esto último también era considerado negativo por los detractores (TC=3%; NTC=9,8%): «Este anuncio me parece una forma de chantaje porque solo pueden ganar si compran la bebida» (Estudiante 17_NTC). Otros argumentos de los estudiantes que consideran el anuncio inaceptable son: 1) Fomento del consumo de alcohol (TC=21,2%; NTC=17,1%); 2) Inadecuado para niños y jóvenes (TC=13,6%; NTC=14,6%), incluida una referencia explícita a mostrar este anuncio en Facebook, que es utilizado con frecuencia por los jóvenes;?3) Desacuerdo con la publicidad del alcohol (TC=7,6%; NTC=11%). Además, durante la lección los estudiantes aprendieron que la publicidad del alcohol solo está permitida en condiciones estrictas. Por ejemplo, no está permitido dirigirse directamente a los menores ni establecer una relación entre el consumo de alcohol y la mejora del rendimiento o un efecto tranquilizante. A pesar de la integración de este tema, solo cuatro estudiantes (TC: n=2; NTC: n=2) se refirieron explícitamente a aspectos legales en el post-test. Una frase esclarecedora: «En este anuncio solo participan adultos y nadie conduce un coche. Creo que es un anuncio adecuado» (Estudiante 92_TC).

4. Discusión y conclusiones

Hoy en día, mejorar la alfabetización en publicidad de los menores de edad cobra cada vez mayor importancia debido al aumento de nuevos formatos publicitarios (Daems & De-Pelsmacker, 2015). Durante las últimas décadas, ya se han desarrollado programas de alfabetización en publicidad (Meeus & al., 2014). No obstante, Rozendaal y colaboradores (2011) indicaron que los programas educativos existentes hacen hincapié principalmente en la dimensión cognitiva (reconocer varios formatos publicitarios, comprender tácticas de persuasión, etc.). En el contexto de este estudio, se desarrolló material de aprendizaje dirigido a mejorar la alfabetización ética en publicidad de los adolescentes (es decir, el juicio moral sobre los formatos, las tácticas y los mensajes publicitarios). En consonancia con las investigaciones de Martinson (2001), que cita la diferencia entre la ley de publicidad y las cuestiones éticas en los anuncios, este material de aprendizaje se dividió en dos partes. La primera parte versa sobre la ley de publicidad flamenca (Vlaamse Regulator voor de Media [Regulador flamenco de los medios], 2009) desde la perspectiva de que influye (implícitamente) en las percepciones personales sobre la adecuación de la publicidad (Hudders & al., 2015; Martinson, 2001). En la segunda parte, se presta atención a las preocupaciones éticas de la publicidad (De-Pelsmacker, 2016).

Un objetivo inicial de este estudio de intervención era identificar si la alfabetización publicitaria conduce a un mejor conocimiento de la ley de publicidad. Los resultados muestran que los estudiantes saben más acerca de la ley de publicidad después de la lección. No obstante, los estudiantes que no usaron tablet y que reflexionaron individualmente sobre temas relacionados con la ley antes del debate en clase dirigido por el profesor, parecen aprender más que los estudiantes que usaron tablet y que procesaron el contenido de aprendizaje en parejas a través de una aplicación para tablet. Una posible explicación se halla en los datos relativos a las percepciones de los estudiantes sobre el uso de tablets en la educación. Aunque la mayoría de los estudiantes que usaron tablet percibieron la lección sobre publicidad como más divertida que otras lecciones, fueron conscientes de que tuvo un efecto negativo en su rendimiento de aprendizaje. Este resultado se halla en consonancia con un estudio de Montrieux y colaboradores (2015) que indica que los estudiantes, aparte de reconocer el valor añadido de usar tablets en un entorno educativo, también admiten que su capacidad de aprendizaje no ha aumentado igual de bien porque las tablets causan distracciones.

El segundo objetivo de la investigación era doble: a) descubrir qué anuncios son calificados como polémicos por los adolescentes, y b) revelar el juicio moral de los estudiantes sobre la desnudez y la belleza femenina en los anuncios y sobre la publicidad del alcohol antes y después del curso. En lo que se refiere a la primera parte (RO2a), analizamos las cartas ficticias de los estudiantes, dirigidas al Tribunal para prácticas éticas en publicidad (JEP) sobre un anuncio polémico elegido por ellos mismos. En las dos condiciones, se seleccionaron en particular los anuncios que contenían estereotipos sexuales y desnudez. Debido a un efecto significativo, podemos asumir que los estudiantes que usaron tablet tienen una actitud más crítica hacia la belleza femenina y la desnudez en los anuncios tras la intervención (RO2b). El efecto significativo podría atribuirse a la forma en que los estudiantes eligieron un anuncio polémico. Según se observó en el aula, los grupos de estudiantes de esta condición hablaban inmediatamente de la desnudez y la belleza femenina en los anuncios después de escuchar la tarea (aprendizaje colaborativo). Buscaron activamente este tipo de anuncios y probablemente se enfrentaron a una serie de ejemplos y de artículos (de prensa) que incluían argumentos contra esos anuncios (aprendizaje activo y auténtico). Aparte de la belleza femenina y la desnudez en los anuncios, los estudiantes que usaron tablet no toleraron la discriminación y la violencia, ni los anuncios de comida no saludable. En la condición sin uso de tablet, también se consideraron polémicos elementos como utilizar Photoshop y representar una situación insegura. No obstante, podemos presumir que los estudiantes que no usaron tablet no siempre encontraron el anuncio que tenían en mente, ya que la mayoría de ellos refirieron que sería interesante la opción de buscar un anuncio en Internet.

En los diversos anuncios polémicos, los estudiantes de las dos condiciones justifican su elección con argumentos similares en sus cartas formales. Para empezar, se hace referencia reiteradamente a las consecuencias de los anuncios. En el caso de estereotipos sexuales en los anuncios, los estudiantes se refieren a menudo a los posibles efectos negativos para la imagen propia de las adolescentes y al deseo de perder peso. Por consiguiente, los adolescentes son conscientes de estos efectos, que también confirman estudios anteriores (Grabe, Ward, & Hyde, 2008; Levine & Murnen, 2009). Los estudiantes también citan los argumentos siguientes en más de una ocasión: 1) Inadecuado para niños o jóvenes; 2) Ninguna relación entre el anuncio y el producto; 3) Desnudez; 4) Insulto y engaño. El insulto lo mencionan más los estudiantes que usaron tablet, sobre todo en las cartas formales sobre los anuncios discriminatorios. El engaño se destaca en particular en la condición sin uso de tablet, probablemente debido a que en el material de aprendizaje de esta condición se facilitaron más ejemplos de publicidad engañosa. Por lo tanto, los estudiantes seleccionan los anuncios engañosos cuando estos se ofrecen, pero no los buscan conscientemente. En consecuencia, una cuestión importante para investigaciones futuras es facilitar diferentes categorías de anuncios polémicos y sus consecuencias, permitiendo a los estudiantes que se familiaricen con diversos temas éticos de los anuncios y que reflexionen críticamente sobre estos. Por ejemplo, es aconsejable prestar mayor atención a la publicidad del alcohol. Como han señalado Martino y colaboradores (2016), los adolescentes parecen estar acostumbrados a la presencia de anuncios de alcohol. A pesar de la incorporación de contenido de aprendizaje relativo a este tema, los estudiantes de las dos condiciones apenas se refieren a la publicidad del alcohol en sus cartas formales (RO2a). Sobre la base de los hallazgos obtenidos en los pre-test y los post-test (RO2b), este estudio no muestra un aumento significativo en las actitudes críticas de los adolescentes hacia la publicidad del alcohol. Investigaciones anteriores (Ellickson & al., 2005; Scull & al., 2010) han puesto de manifiesto que una actitud crítica y las habilidades de deconstrucción de la publicidad del alcohol disminuyen los efectos negativos de estos anuncios, de modo que se requieren más investigaciones para explorar intervenciones educativas que puedan anticipar esto. Lo mismo se aplica al pensamiento crítico sobre nuevos formatos publicitarios ocultos e interactivos. Dicho de otro modo, en lugar de juzgar un anuncio por el formato, los estudiantes eligieron los anuncios basándose en cuestiones sustantivas.

Cabe poner una nota de cautela debido al sesgo de género de la muestra. Dado que las clases participantes estaban formadas principalmente por alumnas, es necesario que las investigaciones futuras se lleven a cabo en clases con equilibrio de género a fin de descubrir si se consideran polémicos los mismos anuncios y si se aportan los mismos argumentos fundamentados. Además, los hallazgos de este estudio pueden tener una cierta limitación al medir la opinión de los estudiantes mediante cartas formales y un pre-test y post-test. Desgraciadamente, algunas respuestas de los estudiantes son más bien superficiales. Por este motivo, puede sugerirse que sería una buena alternativa realizar también entrevistas en profundidad con los estudiantes a fin de conocer mejor su juicio moral sobre anuncios poco éticos antes y después de las lecciones.

A modo de conclusión, puede afirmarse que la lección destinada a mejorar la alfabetización ética en publicidad de los jóvenes resulta eficaz para aumentar el conocimiento de estos sobre la ley de publicidad. Asimismo, se desafió a los estudiantes a pensar críticamente sobre anuncios polémicos y a proporcionar argumentos fundamentados respecto a estos anuncios. No obstante, este estudio muestra que se requieren más investigaciones para encontrar ejercicios de clase adecuados que fomenten el juicio moral de los estudiantes respecto a diversos temas poco éticos presentes en los anuncios.

Referencias

Adams, B., Schellens, T., & Valcke, M. (2015). Een analyse van het Vlaamse onderwijscurriculum anno 2015. In welke mate is reclamewijsheid aanwezig in het curriculum? [An Analysis of the Flemish Curriculum Anno 2015. To What Extent is Advertising Literacy Present in the Curriculum?]. (https://goo.gl/L8EmjJ) (2016-04-28).

Aguaded, I. (2011). Media Education: An International Unstoppable Phenomenon UN, Europe and Spain Support for Edu-communication [La educación mediática, un movimiento internacional imparable. La ONU, Europa y España apuestan por la educomunicación]. Comunicar, 37, 7-8. https://doi.org/10.3916/C37-2011-01-01

Aguaded, I. (2013). Media Programme (UE) - International Support for Media Education. [El Programa «Media» de la Comisión Europea, apoyo internacional a la educación en medios]. Comunicar, 40, 07-08. https://doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-01-01

Anderson, P., de-Bruijn, A., Angus, K., Gordon, R., & Hastings, G. (2009). Impact of Alcohol Advertising and Media Exposure on Adolescent Alcohol Use: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Alcohol & Alcoholism, 44(3), 229-243. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agn115

Apestaartjaren (2016). Onderzoeksrapport Apestaartjaren 6 [Research report Apestaartjaren 6]. (https://goo.gl/GOIx4U) (2016-10-03).

Calvert, S.L. (2008). Children as Consumers: Advertising and Marketing. The Future of Children, 18(1), 205-234. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.0.0001

Daems, K., & De-Pelsmacker, P. (2015). Marketing Communication Techniques Aimed at Children and Teenagers. (https://goo.gl/L8EmjJ) (2016-04-28).

De-Pelsmacker, P. (2016). Ethiek in reclame [Ethics in Advertising] [PowerPoint Slides]. (https://goo.gl/Zu6vWo) (2016-11-20).

Duffy, T.M., & Cunningham, D.J. (1996). Constructivism: Implications for the Design and Delivery of Instruction. In D.J. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research for Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 170-198). New York: Macmillan Library Reference.

Ellickson, P.H., Collins, R.L., Hambarsoomians, K., & McCaffrey, D.F. (2005). Does Alcohol Advertising Promote Adolescent Drinking? Results from a longitudinal assessment. Addiction, 100(2), 235-246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00974.x

Howitt, D. (2010). Thematic Analysis. In G. Van-Hove, & L. Claes (Eds.), Qualitative Research and Educational Sciences: A Reader about Useful Strategies and Tools (pp. 179-202). Essex: Pearson.

Hudders, L, Cauberghe, V., Panic, K., Adams, B., Daems, K., De-Pauw, P., …, Zarouali, B. (2015, February). Children’s Advertising Literacy in a New Media Environment: An Introduction to the AdLit Research Project. Paper presented at the Etmaal van de Communicatiewetenschap. (https://goo.gl/JLEvuc) (2016-04-28).

Karagiorgi, Y, & Symeou, L. (2005). Translating Constructivism into Instructional Design: Potential and Limitations. Educational Technology & Society, 8(1), 17-27.

Lavine, H., Sweeney, D., & Wagner, S.H. (1999). Depicting Women as Sex Objects in Television Advertising: Effects on Body Dissatisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(8), 1049-1058. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672992511012