(Created page with "<span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_es"></span>Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)</span> ==== Abstract ==== This...") |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 11:44, 28 March 2019

Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This research aims to analyze the level of use of technology by university teachers. We are interested by the frequency of their use in designing the teaching-learning process. The research questions were: what types of learning activities which include are designed by university teachers? What types of technologies do teachers use in the design of their instruction? What is the level of use of digital technologies in the learning designs? To respond to these issues, we designed an inventory of activities of learning technologies at the university which was completed by 941 Andalusian teachers. We have identified the type and frequency of use of technology by university lecturers in their different fields at the same time as studying learning activities that predominate in their learning designs. The results, first of all, reveal a poor integration of ICT in the teaching-learning processes which are, essentially, the teacher-centered learning activities. Secondly, we have identified four profiles which differentiate between d teachers depending on their level of use of ICT. The profile comprising an increased number of teachers makes making reference to the rare use of technology. There are teachers who use technology sparingly, and this is a very small range.

1. Introduction and state of the question

Universities in Spain have gone through a complex process to redesign standards and curricula, mandatory with the implementation of the European Higher Education Area (Guerra, González & García, 2010; Krücken, 2014). Changes introduced in European universities have revealed the need to prioritize a teaching model that is oriented to the students’ learning, in which the incorporation of digital technology is ever more important as a support to facilitate the motivation process and students’ independent learning. As such, a number of reports and recommendations from the European Union have indicated the need to promote empowerment and digital skills among students (Ferrari, Punie & Brecko, 2013).

However, the successful integration of technologies in the teaching-learning process arises when teachers focus their attention less on the technological resources, and more on the actual leaning experience they design using acceptable technology. In recent years, there has been increased concern about studying learning design (Laurillard, 2012). When we talk about learning design, we are referring to the planning exercise carried out by teachers (Dobozy, 2011). There has been extensive research into this topic; some have focused upon clarifying exactly which knowledge and skills are necessary for good design practice (MacLean & Scott, 2011). Others have centered on what cognitive resources are activated when teachers design their teaching (Goodyear & Markauskaite, 2009; Kali, Goodyear & Markauskaite, 2011).

Teachers are continually designing. It is part of their daily tasks. Sometimes, this learning design is explicit while on other occasions, it is implicit. Teachers are expected to incorporate digital technology, not only in their teaching design process, but also in the development of this design when in contact with their students (Jump, 2011).

The results of previous research reveal that there is no evidence that would lead us to the conclusion that in universities classrooms have successfully integrated a wide range of technologies to support the teaching-learning process (Hue & Jalil, 2013; Ng’ambi, 2013). Thus, Shelton (2014) differentiates between «core» and «marginal» technologies; in other words, frequently used technologies (such as PowerPoint) and hardly used technologies (including blogs, podcasts, e-portfolios, wikis or social networks). Kirkwood & Price (2014) analyzed how technology had been incorporated into the teaching practice within the university context after reviewing a wide range of scientific articles, published between 2005 and 2010. They found that in at least 50% of cases, technology had been used without changing the teaching method. For example, it was simply a matter of opening a new channel for the transmission of information. According to Hue & Jalil (2013), the frequency with which technology is used in the teaching-learning process is associated with attitudes regarding the integration of ICTs in the curriculum to improve teaching.

According to Hue & Jalil (2013), the frequency with which technology is used in the teaching-learning process is associated with the attitudes of teachers towards the integration of ICTs in the curriculum to improve teaching. It is all a matter of being able to explain why teachers decide to use or not to use technology; so we have taken into consideration the practical knowledge and beliefs that teachers develop.

To explain why lecturers decide to use technology, we must take into consideration their own practical knowledge and the beliefs that they develop. One relevant framework to understand lecturer knowledge was developed by Shulman (1986); it was later modified by Grossman (1990) among others. According to Shulman, a teacher’s knowledge base is composed of his/her knowledge about the material (content knowledge or CK), knowledge of teaching strategies and classroom management (pedagogical knowledge or PK) and pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) which represents a combination of the first two. Based on the work of Shulman, Mishra & Koehler (2006) proposed a model to integrate technological knowledge as a new type of knowledge to be incorporated into those already mentioned. Thus, the knowledge types proposed by these authors are: technological knowledge (TK), techno-pedagogical knowledge (TPK), technological content knowledge (TCK) and techno-pedagogic content knowledge (TPACK). Based on this model, other authors such as Cox & Graham (2009) moved forward with the conceptualization of each construct and the limits of each. Doering, Veletsianos & Scharber (2009) and Hechter, Phyfe & Vermette (2012), on the other hand, helped us understand that TPACK may appear in a variety of ways, in various contextual conditions, given that there are fluctuations in the relevance of each type of knowledge throughout the teaching-learning process. Yeh, Hsu, Wu, Hwang & Lin (2014), believing that a model still needed to be developed that considers both knowledge and teaching practice, offer a representation (practical-TPACK) that focuses on the TPACK that professors apply practically when they understand the content of the material, design their study plans, teach or assess their students’ progress.

However, although technological knowledge is necessary, it is not enough if teachers fail to consider themselves confident when using it (Ertmer & Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010). It is evident that lecturers’ general beliefs as well as their pedagogical beliefs and attitudes greatly influence their use of ITCs in the classroom (Tejedor, Garcia-Valcarcel & Prada, 2009).

2. Material and method

This research analyzes how the various digital technologies are integrated into university classrooms in Andalusia (Southern Spain). We are interested in learning more about understanding the technological usage level, not as an isolated item, but how it is incorporated into the learning sequences which use it. The research problems in this work are: What type of learning activities using technology do university lecturers design? What technologies do lecturers use in their teaching design? What is the digital technology usage level in the learning designs of university lecturers?

2.1. The Inventory of Learning Activities with Technologies at the University

To respond to these questions, we have designed an Inventory of Learning Activities with Technologies at the University. Other researchers analyzing TPACK have developed various instruments. Abbitt (2011) provides an extensive review of the instruments and methods being used to assess TPACK. To date, the instruments developed generally focus upon analyzing TPACK elements, thus leaving the didactic aspect, which represents the design of learning activities enriched with technologies, to one side.

The Inventory we designed includes initial questions to collect demographic information such as: sex, age, university, field of knowledge and professional category. Another 38 items are also included in the Inventory. Each of these items refers to a specific learning activity and various types: Assimilative, Information management, communicative, productive, experiential and evaluative (Conole, 2007; Marcelo, Yot & al., 2014). These activities may or may not appear in the classroom context; likewise, these may or may not require students’ active participation, but in all cases, digital technologies are involved. Moreover, the items represent learning activities with varying levels of complexity (Aubusson, Burke, Schuck, Kearney & Frischknecht, 2014).

Each of the items had to score from 1 to 6 on a double Likert scale. One refers to the frequency with which it is used (usage level) while the other refers to the degree to which the teacher feels confident when using the activity (confidence level).

The inventory was subject to a validation process by experts. Sixteen university lecturers from various universities and fields of knowledge reviewed the inventory, expressing their level of agreement with each statement, and provided suggestions that should be considered. Regarding their answers, we calculated the Fleiss’ kappa coefficient to learn the concordance among the expert assessors. In that analysis, Z obtained a value of 0.00667341 which corresponded to the value p=0.74250178 (greater than an alpha of 0.05). From there, we can state, with a confidence level of 95%, that there was statistically significant concordance among the values assigned to the various items by the 16 judges.

Once the final version was ready, the inventory was launched on the online survey service (http://goo.gl/ukpTme). It was distributed by email to practically all instructors at the various universities located in Andalusia. To measure the reliability of the inventory, the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was calculated. The coefficient for the scale measuring the usage level of each item was 0.905.

2.2. Sample

The research population is university lecturers from ten universities in the Andalusian region of Spain: nine public and one private. The International University of Andalusia (Universidad Internacional de Andalucía) was excluded due to its specific characteristics. Based on a recent report regarding the 2011-2012 academic year, Andalusian universities had a population of 17,637 lecturers. From this population, which could have undergone slight modifications, the sample was constituted with the 941 university instructors who responded to the inventory. This represents approximately 5.4% of the entire population. Of these, 52.5% were men and 47.5% were women. 42.6% of the subjects were between 41 and 50 years of age, 28% were between 51 and 60 years of age, and 21% between 31 and 40. Lecturers under thirty accounted for 2.7% of the total while 5.8% of the teaching staff was over the age of 61. The percentage of women was greater in the age range under forty, while above that age, most of the respondents were men; this fact this disparity was greater in the over 61 year old group where 65.5% were men.

These university teachers were from various fields of knowledge: 38.4% were from social sciences, 21.4% were from science, 16.5% engineering and 11.6% health sciences while 11.2% were in the field of humanities. Regarding the professional category of these professors, 43.5% were tenured lecturers, 16.2% were contracted PhDs and 12.5% were tenured professors. Pre-doctorate interns, associate professors and substitute professors accounted for 14.4%. Lastly, regarding the universities where the various faculty members responding to the inventory worked, 27.3% were from the University of Seville, 24.9% from the Universidad of Granada, 9.6% from the University of Cadiz, 7.5% from the University of Huelva, 7.2% from the Universidad of Jaen, 6.9% from the University of Almeria and 6.8% from the University of Cordoba. Lesser percentages corresponded to those at the Pablo de Olavide University with 4.4%, the University of Malaga with 3.8% and 1.7% at the University of Loyola.

3. Results

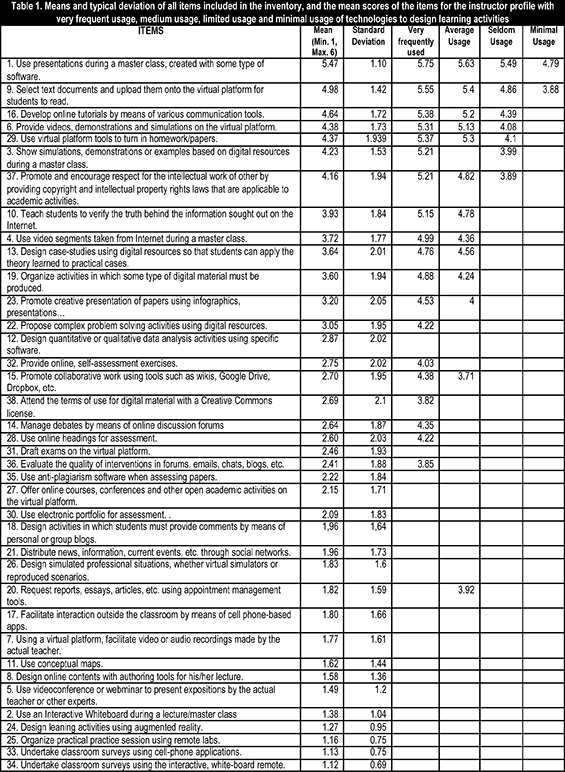

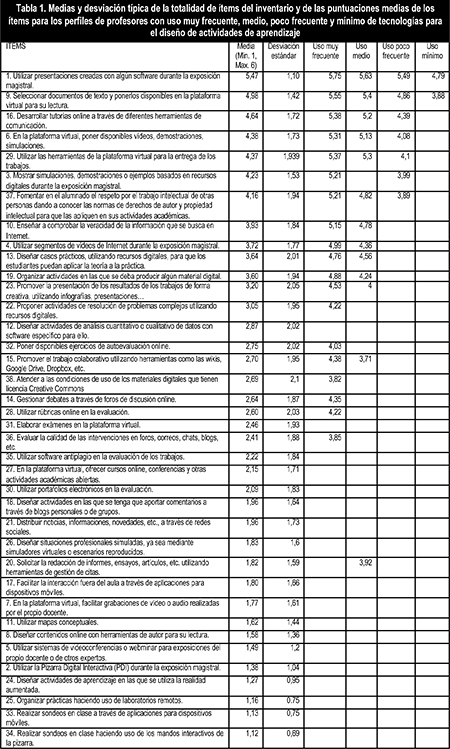

The means obtained for each of the items in the inventory, as shown on Table 1, offer a usage profile of learning with technologies by Andalusian university lecturers, which could be catalogued as «teaching with limited integration of ICTs». The highest values, in mean terms, are those that hardly alternate their «traditional» teaching with technologies, those in which technologies are used for learning activities focusing on the instructor or those that allow limited student participation. Moreover, these are items that are implemented because they offer a basic level of difficulty. On the other hand, items with a very low mean value refer to activities in which the technology used is very advanced and specific; for sample, augmented reality or remote laboratories.

To analyze the various usage levels of the learning activities with technologies, we proceeded to calculate a mean of the general usage per participant according to the scores given for each of the various items of the inventory. Then we sought ranges using the visual grouping option provided by SPSS software. We established the grouping option using midpoint cutoffs and standard deviation +-1, based on the cases explored. With this, four groups were obtained, which allowed us to classify the instructors according the frequency that they used technology in learning activities.

The first of these groups includes lecturers who surpass the 3.694 points for mean general usage; in other words, these made very frequent use of technology in their learning activities. Table 1 shows the items that reached a greater mean level of usage in this group of lecturers.

16.7% of the respondents to the inventory were included in the elevated usage of technology group; this corresponded to 157 participants. These were either men (50.3%) or women (49.7%); most of these (105 people or 66.8%) were between the ages of 31 and 50. Furthermore, higher usage was seen among professors of Education (31.6%), followed by those in the field of Science (14.8%).

It is noteworthy that on the list of learning activities for which these instructors used technology, there were a variety of possibilities. Although the so called assimilative activities (technology as support for the lecturer’s presentation) were used more frequently, we also found learning activities based on communication, information management, application as well as evaluative and productive. It could therefore be said that lecturers who used digital technology intensively, did so for a variety of learning activities for their students.

The second group of lecturers was those whose mean of general use of activities with technologies was between 3.694 and 2.805 points; these were titled average usage. This group constitutes 25.3% of the professors, 238 participants). Of these, 52.5% were men and 46.6% were women. 45% were between 41 and 50 years of age and 26.5% between 51 and 60 years of age. The average use of activities with technologies is especially outstanding among engineering lecturers (20.2%). These instructors, as shown on Table 1, frequently used technology in almost all learning activities we identified with regards to the previous group. However, there is one noteworthy difference with the previous group: limited use of technologies to develop evaluative learning activities.

Thirdly, we found that 44% of the lecturers fell within a range titled as seldom use technology as a teaching support. This category included the largest number of lecturers, with 418 respondents, of which 50.7% were and 49.3% women. 73.4% were between 41 and 60 years of age.

This group of instructors only rarely uses technology, and the type that they use –as shown on table 1– is even more limited. These include multimedia presentations to support master class expositions, email and other communication tools to attend students and a virtual platform to provide texts, videos and other support resources. Students could also access learning tasks using these same resources.

Lecturers whose average scores for general usage was lower than 1.916 made up the fourth group. These corresponded to minimal usage of technology in the teaching-learning process and grouped together 13.6% of the respondents. For the most part, this profile appeared among science lecturers (31%). In this case, the instructors only used two types of leaning activities with technology more frequently: they used presentations created with some type of software during a master’s class and selected text documents and made them available on the virtual platform for reading.

Of these lecturers, 59.8% were men and 69.5% fell within the 41-60 year age group. Lastly, if the four usage profiles were reduced to two, these would be medium-high and low. We found that lecturers from the field of law, labor science and science in general, tended to fall within the lowest profile identified, with 73.6% and 69%, respectively.

4. Discussion and conclusions

The results presented contribute to the debate between stability and change in teachers’ beliefs, attitudes towards and knowledge of technology and its uses in the classroom. Research that has been undertaken to date about the process of change among teachers (with or without technologies) draws attention to the need to learn implicit theories and practical knowledge which teachers have when it comes to explaining why some changes are accepted with ease while others are not. Processes of change in teachers, motivated by technology, show that instructors are oriented toward change within stability. That is to say, they introduce those technologies that are coherent with their teaching methodology, specifically with those activities they usually carry out. This principle of coherence is backed by the results of this research. We found that instructors intensively use those technologies that support teaching and learning strategies in which the main player is the content and its transmission using various media (audio, video, documents and demonstrations).

This result confirms the idea that among lecturers, change does not take place by simply placing them in contact with technology. In other words, technology alone does not change the learning environment. It requires a more intense intervention in which technology accompanies teaching and learning strategies that not only prioritize the acquisition of knowledge based on digital resources, but that are based on the appropriation processing of this knowledge by students through productive, experiential or communicative learning activities (Marcelo, Yot & Mayor, 2011).

Thus, the predominance of assimilative learning activities is commonplace among all instructors, independent of their age or technological usage level. Only with those lecturers who use technology frequently or very frequently do we see learning activities that favor the implementation of what students have learned by solving problems or cases, peer collaboration for team tasks or a more authentic assessment with self-evaluation exercises or headings. Nevertheless, even in the teaching-learning practice of these instructors, there is limited presence of learning activities based on 2.0 technology (Hamid, Chang & Kurnia, 2009) even when students are willing to use them (Roblyer, McDaniel, Webb, Herman & Witty, 2010), and at the same time, other technologies, mentioned in the Horizon report, as in the case of emerging resources such as cell phone applications (Cochrane & Bateman, 2009) or more experiential technologies such as augmented reality, also remain unused.

In this research, we found that there were various groups of instructors with regards to the digital technology usage level in the design of their teaching. The fact remains that there is a significant group (16.7%) of lecturers who have been able to integrate technology as a support to develop a more ample variety of learning activities for their students. Lecturers have promoted changes in their teaching practice and no doubt, in their knowledge and beliefs. More specific studies would require a more detailed analysis of these instructors to learn how these processes have taken place and what measures have influenced the intrinsic (motivation, perception of self-efficiency) or extrinsic variables. Likewise, it would also require an in depth study about why we failed to find –as it would have been expected– a more intensive usage of digital technologies amongst younger lecturers. There seems to be a difference in the usage of technology for personal communication and learning and the use of these same resources in the professional and teaching sphere.

Acknowledgements

This research has been financed by the Andalusian Regional Ministry of Innovation, Science, Business and Employment (Consejería de Innovación, Ciencia, Empresa y Empleo de la Junta de Andalucía). Project for Excellence: P10-HUM-6677.

References

Abbitt, J.T. (2011). Measuring Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Preservice Teacher Education: A Review of Current Methods and Instruments. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 43(4), 281-300. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2010.10782551

Aubussson, P., Burke, P., Schuck, S., Kearney, M., & Frischknecht, B. (2014). Teacher Choosing Rich Tasks: the Moderating Impact of Technology on Student Learning, Enjoyment and Preparation. Educational Researcher, 43(5), 219-229. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X14537115

Cochrane, T., & Bateman, R. (2009). Smartphones Give You Wings: Pedagogical Affordances of Mobile Web 2.0. The Ascilite, Auckland.

Conole, G. (2007). Describing Learning Activities. Tools and Resources to Guide Practice. In H. Beetham, & R. Sharpe (Eds.), Rethinking Pedagogy for a Digital Age: Designing and Delivering E-learning. (pp. 81-91). Oxon: Routledge.

Cox, S., & Graham, C.R. (2009). Diagramming TPACK in Practice: Using an Elaborated Model of the TPACK Framework to Analyze and Depict Teacher Knowledge. TechTrends, 53(5), 60-69. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11528-009-0327-1

Dobozy, E. (2011). Typologies of Learning Design and the Introduction of a ‘LD-Type 2’ Case Example. eLearning Papers, 27(27).

Doering, A., Veletsianos, G., & Scharber, C. (2009). Using the Technological, Pedagogical and Content Knowledge Framework in Professional Development. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (AERA), San Diego.

Ertmer, P.A., & Ottenbreit Leftwich, A.T. (2010). Teacher Technology Change: How Knowledge, Confidence, Beliefs, and Culture Intersect. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 42(3), 255-284. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2010.10782551

Ferrari, A., Punie, Y., & Brecko, B. (2013). DIGCOMP a Framework for Developing and Understanding Digital Competence in Europe. Joint Research Centre & Institute for Prospective Technological Studies. (http://goo.gl/neGyk8) (23-01-2015).

Goodyear, P., & Markauskaite, L. (2009). Teachers’ Design Knowledge, Epistemic Fluency and Reflections on Students’ Experiences. 32nd HERDSA Annual Conference, Darwin.

Grossman, P. (1990). The Making of a Teacher. Teacher Knowledge and Teacher Education. Chicago: Teacher College Press.

Hamid, S., Chang, S., & Kurnia, S. (2009). Identifying the Use of On-line Social Networking in Higher Education. The Ascilite, Auckland.

Hechter, R.P., Phyfe, L.D., & Vermette, L.A. (2012). Integrating Technology in Education: Moving the TPCK Framework towards Practical Applications. Education Research and Perspectives, 39(1), 136-152.

Hue, L.T., & Jalil, H.A. (2013). Attitudes towards ICT Integration into Curriculum and Usage among University Lecturers in Vietnam. International Journal of Instruction, 6(2), 53-66.

Jump, L. (2011). Why University Lecturers Enhance their Teaching through the Use of Technology: A Systematic Review. Learning, Media and Technology, 36(1), 55-68. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2010.521509

Kali, Y., Goodyear, P., & Markauskaite, L. (2011). Researching Design Practices and Design Cognition: Contexts, Experiences and Pedagogical Knowledge-in-pieces. Learning, Media and Technology, 36(2), 129-149. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2011.553621

Kirkwood, A., & Price, L. (2014). Technology-enhanced Learning and Teaching in Higher education: what is ‘enhanced’ and how do we know? A Critical Literature Review. Learning, Media and Technology, 39(1), 6-36. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2013.770404

Krücken, G. (2014). Higher Education Reforms and Unintended Consequences: A Research Agenda. Studies in Higher Education, 39(8), 1439-1450. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.949539

Laurillard, D. (2012). Teaching as a Design Science. Building Pedagogical Patterns for Learning and Technology. London: Routledge.

MacLean, P., & Scott, B. (2011). Competencies for Learning Design: A Review of the Literature and a Proposed Framework. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(4), 557-572. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01090.x

Marcelo, C., Yot, C., & Mayor, C. (2011). Alacena, an Open Learning Design Repository for University Teaching. Comunicar, 37(XIX), 37-44. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C37-2011-02-03

Marcelo, C., Yot, C., Mayor, C., Sánchez, M., Murillo, P., Sánchez, J., & Pardo, A. (2014). Las actividades de aprendizaje en la enseñanza universitaria: ¿Hacia un aprendizaje autónomo de los alumnos? Revista de Educación, 363, 334-359. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2012-363-191

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. (2006). Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017-1054.

Ng’ambi, D. (2013). Effective and Ineffective Uses of Emerging Technologies: Towards a Transformative Pedagogical Model. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(4), 652-661. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12053

Roblyer, M.D., Mcdaniel, M., Webb, M., Herman, J., & Witty, J.V. (2010). Findings on Facebook in Higher Education: A Comparison of College Faculty and Student Uses and Perceptions of Social Networking Sites. Internet and Higher Education, 13(3), 134-140. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.03.002

Shelton, C. (2014). Virtually Mandatory: A Survey of How Discipline and Institutional Commitment Shape University Lecturers’ Perceptions of Technology. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(4), 748-759. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12051

Shulman, L. (1986). Those who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4-14.

Tejedor, F.J., García-Valcárcel, A., & Prada, S. (2009). Medida de actitudes del profesorado universitario hacia la integración de las TIC. Comunicar, 33, 115-124. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/c33-2009-03-002

Yeh, Y.F., Hsu, Y.S., Wu, H.K., Hwang, F.K., & Lin, T.C. (2014). Developing and Validating Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge-practical (TPACK-practical) through the Delphi Survey Technique. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(4), 707-722. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12078

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Esta investigación tiene por objetivo analizar el nivel de uso que de las tecnologías hace el profesorado universitario, interesándose tanto por la frecuencia de uso de ellas, como por el tipo de actividades de aprendizaje en las que se utilizan. Los problemas de investigación se centraron en: ¿qué tipos de actividades de aprendizaje con tecnologías diseñan los docentes universitarios?, ¿qué tipo de tecnologías utilizan los docentes en el diseño de su enseñanza?, ¿cuál es el nivel de uso de las tecnologías digitales en los diseños del aprendizaje del profesorado universitario? Hemos diseñado el Inventario de Actividades de Aprendizaje con Tecnologías en la Universidad que fue respondido por 941 docentes andaluces. A través de él hemos identificado el tipo y frecuencia de uso que de la tecnología hace el profesorado universitario en sus materias al tiempo que hemos estudiado las actividades de aprendizaje que predominan en sus diseños del aprendizaje. Los resultados revelan una pobre integración de tecnologías en los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje los cuales se constituyen, esencialmente, de actividades de aprendizaje centradas en el docente. Hemos identificado cuatro perfiles diferenciados de docentes en función del nivel de uso que hacen de las TIC. De los cuatro, el perfil que mayor número de docentes agrupa es el que hace referencia a un uso poco frecuente de la tecnología; son docentes que emplean escasamente la tecnología y esta es de una gama muy reducida.

1. Introducción y estado de la cuestión

Las universidades europeas han pasado por un complejo proceso de rediseño normativo y de los planes de estudio, impuesto por la implantación del Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior (Krücken, 2014). Los cambios introducidos en las universidades europeas han puesto de manifiesto la necesidad de priorizar un modelo de enseñanza orientada hacia el aprendizaje de los alumnos, en el que adquiere cada vez más importancia la incorporación de la tecnología digital como soporte para facilitar los procesos de motivación y aprendizaje autónomo del alumnado. Así, diferentes informes y recomendaciones de la Unión Europea han puesto de manifiesto la necesidad de promover la autonomía de los individuos y su competencia digital (Ferrari, Punie & Brecko, 2013).

Pero la integración exitosa de las tecnologías en los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje se produce cuando el profesorado centra su atención no tanto en los recursos tecnológicos, sino en las experiencias de aprendizaje que diseñan y para las que las tecnologías resultan adecuadas. En los últimos años, la preocupación por el estudio del diseño del aprendizaje se ha incrementado notablemente (Laurillard, 2012). Por diseño del aprendizaje nos estamos refiriendo al ejercicio de planificación en que todo docente se implica (Dobozy, 2011) y en torno al cual se ha producido un amplio número de investigaciones: unas centradas en desvelar qué conocimientos y competencias son necesarias para una buena práctica de diseño (MacLean & Scott, 2011), y otras en qué recursos cognitivos se activan cuando los docentes diseñan su enseñanza (Goodyear & Markauskaite, 2009; Kali, Goodyear & Markauskaite, 2011).

Los docentes están continuamente diseñando. Forma parte de su trabajo cotidiano. Este diseño del aprendizaje a veces es explícito y otras implícito. Y se espera de los docentes que incorporen tecnologías digitales no solo en el propio proceso de diseño de su enseñanza sino en el desarrollo de este diseño en contacto con los alumnos (Jump, 2011).

Los resultados de investigaciones previas nos desvelan que no hay evidencias que nos lleven a pensar que en las aulas universitarias se ha integrado de manera exitosa una amplia gama de tecnologías para apoyar el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje (Hue & Jalil, 2013; Ng’ambi, 2013). Así, Shelton (2014) diferencia entre «core» y «marginal» tecnologías, esto es, tecnologías frecuentemente utilizadas (como Powerpoint) y tecnologías escasamente usadas (como los blogs, podcasts, e-portfolios, wikis o redes sociales). Kirkwood y Price (2014) analizaron cómo la tecnología había sido incorporada a la práctica de enseñanza en el contexto universitario a partir de la revisión de una gama de artículos científicos que habían sido publicados en el periodo de 2005 a 2010 y encontraron que en, al menos, el cincuenta por ciento de ellos la tecnología había sido empleada sin modificarse el método de enseñanza, por ejemplo, simplemente abriendo un nuevo canal de transmisión de información.

Según Hue y Jalil (2013), la frecuencia de uso de la tecnología en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje se asocia a las actitudes que se tengan hacia la integración de las TIC en el currículo para mejorar la enseñanza. Lo cierto es que para poder explicarnos por qué los profesores deciden utilizar o no las tecnologías hemos de tener en cuenta el propio conocimiento práctico y creencias que los docentes desarrollan.

Uno de los modelos que conserva vigencia para comprender el conocimiento de los profesores es el desarrollado por Shulman (1986), después modificado, entre otros, por Grossman (1990). De acuerdo con Shulman, el conocimiento base de un docente está compuesto por el conocimiento de la materia que posee (conocimiento del contenido, CK), el conocimiento de las estrategias de enseñanza y gestión del aula (conocimiento pedagógico, PK) y el conocimiento pedagógico del contenido (PCK) el cual representa la mezcla de los dos primeros. Partiendo de la base de los trabajos de Shulman, Mishra y Koehler (2006) propusieron un modelo para integrar el conocimiento tecnológico como un nuevo tipo de conocimiento que viene a incorporarse a los tipos de conocimiento que ya hemos enunciado. De esta forma los tipos de conocimiento propuestos por estos autores son: conocimiento tecnológico (TK), conocimiento tecno-pedagógico (TPK), conocimiento tecnológico del contenido (TCK) y conocimiento tecno-pedagógico del contenido (TPACK). A partir de este modelo otros autores como Cox y Graham (2009) han avanzado con la conceptualización de cada constructo y las delimitaciones entre ellos. Doering, Veletsianos y Scharber (2009) y Hechter, Phyfe y Vermette (2012), por su parte, nos ayudaron a comprender que el TPACK puede manifestarse de distinta forma en diferentes condiciones contextuales, puesto que existe oscilación en la relevancia de cada tipo de conocimiento a lo largo del proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje. Yeh, Hsu, Wu, Hwang y Lin (2014), al creer que todavía faltaba por desarrollarse un modelo que considerara al mismo tiempo el conocimiento y la práctica docente, ofrecen una representación (el TPACK-práctico) que se centra en el TPACK que los profesores aplican de forma práctica cuando comprenden el contenido de la materia, diseñan un plan de estudios, enseñan o evalúan el progreso de los estudiantes.

Sin embargo, aunque el conocimiento de la tecnología sea necesario, no es suficiente si los docentes no se autoperciben competentes en su uso (Ertmer & Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010). Se ha puesto en evidencia el hecho de que las creencias generales de los docentes, así como sus creencias pedagógicas, y sus actitudes influyen de manera determinante en la utilización de las TIC en el aula (Tejedor, García-Valcárcel & Prada, 2009).

2. Material y método

En esta investigación analizamos cómo se integran las diferentes tecnologías digitales en las aulas de las universidades andaluzas. Nos interesa avanzar en la comprensión del nivel de uso que se hace de las tecnologías pero no de forma aislada sino abordando cómo se incorporan en las secuencias de aprendizaje que se implementan. Los problemas de investigación que nos planteamos en esta investigación son los siguientes: ¿qué tipos de actividades de aprendizaje con tecnologías diseñan los docentes universitarios?, ¿qué tipo de tecnologías utilizan los docentes en el diseño de su enseñanza?, ¿cuál es el nivel de uso de las tecnologías digitales en los diseños del aprendizaje del profesorado universitario?

2.1. El inventario de actividades de aprendizaje con tecnologías en la Universidad

Para dar respuesta a estas preguntas hemos diseñado el Inventario de Actividades de Aprendizaje con Tecnologías en la Universidad. Otras investigaciones que han abordado el análisis del TPACK han desarrollado diferentes instrumentos. Abbitt (2011) nos proporciona una amplia revisión de los instrumentos y métodos que se vienen empleando para la evaluación del TPACK. Los instrumentos desarrollados hasta ahora se centran principalmente en el análisis de los elementos del TPACK, dejando de lado el aspecto didáctico que representa el diseño de actividades de aprendizaje enriquecidas con tecnologías.

El inventario que diseñamos consta de preguntas iniciales para recabar información demográfica como: sexo, edad, universidad, rama de conocimiento y categoría profesional que se ostenta. El resto del inventario está formado por 38 ítems. Cada uno de estos ítems hace referencia a una actividad de aprendizaje concreta y de diferente tipo: asimilativas, gestión de información, comunicativas, productivas, experienciales y evaluativas (Conole, 2007; Marcelo, Yot & al., 2014). Estas actividades pueden darse en el contexto del aula o no, así como pueden requerir la participación activa del alumnado o no, pero sí en todas hay presencia de tecnologías digitales. Además los ítems representan actividades de aprendizaje con diferente nivel de complejidad (Aubusson, Burke, Schuck, Kearney & Frischknecht, 2014).

Cada uno de los ítems debía de ser valorado del 1 al 6 sobre una doble escala tipo Likert: una referida a la frecuencia con la que se llevan a cabo (nivel de uso) y otra al grado en que el docente se siente seguro/a cuando implementa la actividad (nivel de confianza).

El inventario fue sometido a un proceso de validación de expertos. En total 16 docentes universitarios de distintas universidades y áreas del conocimiento revisaron el inventario, expresando su grado de acuerdo con cada afirmación y aportando sugerencias que debían de ser consideradas. Sobre sus respuestas calculamos el coeficiente de Kappa de Fleiss para conocer la concordancia entre los evaluadores expertos. En ese análisis, Z obtuvo un valor de 0,00667341 y le correspondió un valor p=0,74250178 (superior a un alfa de 0,05). A partir de ahí afirmamos, con un nivel de confianza del 95%, que existió concordancia estadísticamente significativa entre las valoraciones asignadas por los 16 jueces a los distintos ítems. Una vez que dispusimos de su versión final, el inventario fue implementado en el servicio online e-encuestas (http://goo.gl/X9x4yY) y fue distribuido a través del correo electrónico a la práctica totalidad de los docentes de las distintas universidades con sede en Andalucía.

Para medir la fiabilidad del inventario se calculó el coeficiente Alfa de Cronbach. El coeficiente para la escala que mide el nivel de uso de cada uno de los ítems es de 0,905.

2.2. Muestra

La población de esta investigación son los profesores universitarios de 10 universidades andaluzas: 9 públicas y 1 privada. Excluimos a la Universidad Internacional de Andalucía por sus características específicas. El número total de docentes en el conjunto de las universidades de Andalucía, según el informe más reciente del curso 2011-12, fue de 17.637. A partir de esta población, que puede haber tenido alguna pequeña modificación, la muestra quedó constituida por los 941 docentes universitarios que respondieron el inventario, lo que representa aproximadamente el 5,4% de la población. De ellos, el 52,5% eran hombres y el 47,5% eran mujeres. El 42,6% de los sujetos tenían edades comprendidas entre los 41 y 50 años, el 28% entre los 51 y 60 años y el 21% entre los 31 y 40 años. Los docentes con edades menores de los 30 años eran el 2,7% del total y los mayores de 61 años sumaron el 5,8% de los docentes. El porcentaje de mujeres fue mayor al de hombres en los tramos de edad inferiores a los 40 años mientras que a partir de esta edad hubo mayor proporción de hombres, que se acentúa en los mayores de 61 años donde el 65,5% son varones.

Los docentes universitarios pertenecen a las diferentes áreas del conocimiento: el 38,4% pertenecía al área de ciencias sociales, el 21,4% eran del área de ciencias, el 16,5% del de ingeniería, el 11,6% de ciencias de la salud y el 11,2% de humanidades. En relación con la categoría profesional de los docentes, el 43,5% eran profesores titulares de universidad, el 16,2 % contratados doctores y el 12,5% catedráticos de universidad. Los becarios pre-doctorales, los profesores asociados y los profesores sustitutos interinos sumaron el 14,4%. Por último, respecto de las universidades a las que pertenecían los profesores que respondieron el inventario, el 27,3% de los profesores pertenecía a la Universidad de Sevilla y el 24,9% a la Universidad de Granada. El 9,6% eran docentes de la Universidad de Cádiz, el 7,5% de la Universidad de Huelva, el 7,2% de la Universidad de Jaén, el 6,9% de la Universidad de Almería y el 6,8% de la Universidad de Córdoba. En menor porcentaje, el 4,4% estaban afiliados a la Universidad Pablo de Olavide, el 3,8% a la Universidad de Málaga y el 1,7% a la Universidad de Loyola.

3. Resultados

Las medias obtenidas por cada uno de los ítems del inventario, como puede observarse en la Tabla 1, nos presentan un perfil de uso de las actividades de aprendizaje con tecnologías, por parte del profesorado universitario andaluz, que podríamos catalogar como «enseñanza con pobre integración de tecnologías digitales». Los ítems mejor valorados en término medio son aquellos que alteran escasamente la práctica de enseñanza «tradicional», aquellos en que las tecnologías se ponen al servicio de actividades de aprendizaje centradas en el docente o en las que se concede poco margen de participación al alumnado. Además estos son ítems de un nivel de dificultad básico para su implementación. Por su parte, los ítems con valoración media más baja son los referidos a actividades en que las tecnologías que se emplean son muy avanzadas y específicas, por ejemplo, la realidad aumentada o los laboratorios remotos.

Para analizar los diferentes niveles de uso de actividades de aprendizaje con tecnologías, hemos procedido a calcular una media de uso general por sujeto según las puntuaciones dadas por cada uno de ellos a los diferentes ítems del inventario. Seguidamente, buscamos rangos utilizando la opción de agrupación visual que nos proporciona el software SPSS. Establecimos la opción de agrupamiento mediante puntos de corte en media y desviación estándar +-1, basados en los casos explorados. De esta forma hemos obtenido cuatro grupos que nos permiten clasificar a los docentes según la frecuencia con la que emplean actividades de aprendizaje con tecnologías.

El primero de ellos agrupa a los docentes que superan los 3,694 puntos de media de uso general, por tanto, hacen un uso muy frecuente de actividades de aprendizaje con tecnologías. En la tabla 1 podemos ver los ítems que en este grupo de profesores han alcanzado mayor nivel medio de uso.

El grupo de profesores que representa este nivel de uso elevado de tecnologías corresponde a un 16,7% del total de profesores que respondieron el inventario, o lo que es lo mismo a 157 sujetos. Estos indistintamente son hombres (50,3%) o mujeres (49,7%), ahora bien, la mayoría de ellos (105 personas, 66,8%) tiene edades comprendidas entre los 31-50 años. Asimismo, el nivel de uso alto destaca entre el profesorado de Educación (31,6%) y en segundo lugar de Ciencias (14,8%).

Hay que destacar que en el listado de actividades de aprendizaje para las que estos profesores utilizan las tecnologías, encontramos una variedad de posibilidades. Así, aunque las que con mayor frecuencia se utilizan son las denominadas asimilativas (las tecnologías como apoyo a la exposición del profesor), también encontramos actividades de aprendizaje basadas en la comunicación, la gestión de información, la aplicación, así como evaluativas y productivas. Podríamos decir, por tanto, que los profesores con un uso intensivo de las tecnologías digitales las utilizan para una variedad de actividades de aprendizaje de los alumnos.

Un segundo grupo de docentes, cuya media de uso general de actividades con tecnologías se encuentra entre los 3,694 puntos y los 2,805 puntos, lo denominamos como de uso medio. Este grupo lo constituye el 25,3% del profesorado (238 sujetos). De ellos, el 52,5% son hombres y el 46,6% son mujeres. El 45% tiene edades comprendidas entre los 41-50 años y el 26,5% entre los 51-60 años. El uso medio de actividades con tecnologías destaca especialmente entre el profesorado de Ingeniería (20,2%). Este profesorado, como se observa en la tabla 1, utiliza de forma frecuente la práctica totalidad de las actividades de aprendizaje que hemos identificado en relación con el grupo anterior. Sin embargo, es de destacar una diferencia respecto del grupo anterior: la escasez de uso de las tecnologías para el desarrollo de actividades de aprendizaje evaluativas.

En tercer lugar encontramos que el 44% del profesorado se encuentra en el rango que podríamos denominar uso poco frecuente de tecnologías para el apoyo a la enseñanza. Es el nivel que mayor número de docentes incluye, en total 418 personas siendo el 50,7% hombres y el 49,3% mujeres. El 73,4% tiene edades comprendidas entre los 41-60 años.

Este profesorado no solo usa con poca frecuencia las tecnologías sino que el tipo de tecnologías que utiliza es, como puede verse en la tabla 1, de una gama muy reducida: presentaciones multimedia que apoyan sus exposiciones magistrales, correo electrónico y otras herramientas de comunicación para atender al alumnado y plataforma virtual en la que ponen disponibles textos, vídeos y demás recursos de ayuda al estudio y a través de la cual los alumnos entregan las tareas de aprendizaje.

En cuarto lugar, encontramos a los docentes cuyas puntuaciones medias de uso general son menores a 1,916 formando el cuarto de los niveles. Este se corresponde con un uso mínimo de las tecnologías en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje y agrupa al 13,6% de los profesores que respondieron el inventario. Este perfil se da principalmente entre el profesorado de Ciencias (31%). En este caso, los profesores solo utilizan con frecuencia dos tipos de actividades de aprendizaje con tecnologías: utilizar presentaciones creadas con algún software durante la exposición magistral, y seleccionar documentos de texto y ponerlos disponibles en la plataforma virtual para su lectura.

De estos profesores, el 59,8% son hombres y el 69,5% tienen edades comprendidas entre los 41 y 60 años.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

Los resultados que hemos presentado contribuyen al debate entre estabilidad y cambio en las creencias, actitudes y conocimiento del profesorado hacia las tecnologías y su uso en la enseñanza. Las investigaciones que previamente se han venido desarrollando sobre los procesos de cambio en los docentes (con y sin tecnologías) llaman la atención a la necesidad de atender las teorías implícitas y conocimientos prácticos que los docentes poseen a la hora de explicar por qué algunos cambios se asumen con facilidad y otros no. Los procesos de cambio en los docentes, motivados por las tecnologías, muestran que los profesores se orientan al cambio dentro de la estabilidad. Es decir, introducen aquellas tecnologías que son coherentes con sus prácticas docentes, específicamente con las actividades de aprendizaje que habitualmente desarrollan. Este principio de coherencia viene avalado por los resultados de esta investigación. Encontramos que los docentes hacen un uso intensivo de aquellas tecnologías que apoyan estrategias de enseñanza y aprendizaje en las que el contenido y su transmisión a través de diferentes medios (audio, vídeo, documentos, demostraciones) es el principal protagonista.

Este resultado viene a corroborar la idea de que el cambio en los docentes no se produce solo por poner a los profesores en contacto con las tecnologías. O lo que es lo mismo, las tecnologías por sí solas no cambian los ambientes de aprendizaje. Se requiere de intervenciones más intensas en las que las tecnologías acompañen a estrategias de enseñanza y de aprendizaje que no solo prioricen la adquisición de conocimientos basados en recursos digitales sino que apoyen un proceso de apropiación de estos conocimientos por parte del alumnado a través de actividades de aprendizaje productivas, experienciales o comunicativas (Marcelo, Yot & Mayor, 2011).

Así, el predominio de las actividades de aprendizaje de tipo asimilativa es común en todos los docentes indistintamente de cual sea su edad o su nivel de uso de la tecnología. Solo en los docentes que utilizan las tecnologías de manera frecuente o muy frecuente se presencian actividades de aprendizaje que favorecen la puesta en práctica de lo aprendido por parte del alumnado a través de la resolución de problemas o casos, la colaboración entre iguales en tareas de equipo o una evaluación más auténtica con el uso de ejercicios de autoevaluación o las rúbricas. No obstante, incluso en las prácticas de enseñanza-aprendizaje de estos docentes hay escasa presencia de actividades de aprendizaje apoyadas en tecnologías 2.0 (Hamid, Chang & Kurnia, 2009) aun cuando el alumnado estaría predispuesto a utilizarlas (Roblyer, McDaniel, Webb, Herman & Witty, 2010), al tiempo que quedan excluidas otras tecnologías citadas en los informes Horizon como recursos de pronta irrupción como las aplicaciones móviles (Cochrane & Bateman, 2009) o tecnologías más experienciales como la realidad aumentada.

En esta investigación encontramos además que existen diferentes grupos de docentes en relación con el nivel de uso de las tecnologías digitales en el diseño de su enseñanza. Que existe un grupo no desdeñable (16,7%) de profesores que han sido capaces de integrar las tecnologías como apoyo para el desarrollo de una amplia variedad de actividades de aprendizaje de los alumnos. Docentes que han promovido cambios en sus prácticas y seguramente en sus conocimientos y creencias. Estudios más específicos requerirán analizar en mayor detalle a estos docentes para aprender cómo se han producido estos procesos y en qué medida han influido las variables intrínsecas (motivación, percepción de autoeficacia) o las extrínsecas. De la misma forma se requerirá estudiar por qué no encontramos –como hubiera sido razonable esperar– un uso más intensivo de las tecnologías digitales por parte de los profesores más jóvenes. Pareciera que existe una diferencia de uso entre las tecnologías para la comunicación y aprendizaje personal y el uso de estas tecnologías en un ámbito profesional y docente.

Apoyos y agradecimientos

Esta investigación ha sido financiada por la Consejería de Innovación, Ciencia, Empresa y Empleo de la Junta de Andalucía. Proyecto de Excelencia: P10-HUM-6677.

Referencias

Abbitt, J.T. (2011). Measuring Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Preservice Teacher Education: A Review of Current Methods and Instruments. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 43(4), 281-300. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2010.10782551

Aubussson, P., Burke, P., Schuck, S., Kearney, M., & Frischknecht, B. (2014). Teacher Choosing Rich Tasks: the Moderating Impact of Technology on Student Learning, Enjoyment and Preparation. Educational Researcher, 43(5), 219-229. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X14537115

Cochrane, T., & Bateman, R. (2009). Smartphones Give You Wings: Pedagogical Affordances of Mobile Web 2.0. The Ascilite, Auckland.

Conole, G. (2007). Describing Learning Activities. Tools and Resources to Guide Practice. In H. Beetham, & R. Sharpe (Eds.), Rethinking Pedagogy for a Digital Age: Designing and Delivering E-learning. (pp. 81-91). Oxon: Routledge.

Cox, S., & Graham, C.R. (2009). Diagramming TPACK in Practice: Using an Elaborated Model of the TPACK Framework to Analyze and Depict Teacher Knowledge. TechTrends, 53(5), 60-69. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11528-009-0327-1

Dobozy, E. (2011). Typologies of Learning Design and the Introduction of a ‘LD-Type 2’ Case Example. eLearning Papers, 27(27).

Doering, A., Veletsianos, G., & Scharber, C. (2009). Using the Technological, Pedagogical and Content Knowledge Framework in Professional Development. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (AERA), San Diego.

Ertmer, P.A., & Ottenbreit Leftwich, A.T. (2010). Teacher Technology Change: How Knowledge, Confidence, Beliefs, and Culture Intersect. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 42(3), 255-284. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2010.10782551

Ferrari, A., Punie, Y., & Brecko, B. (2013). DIGCOMP a Framework for Developing and Understanding Digital Competence in Europe. Joint Research Centre & Institute for Prospective Technological Studies. (http://goo.gl/neGyk8) (23-01-2015).

Goodyear, P., & Markauskaite, L. (2009). Teachers’ Design Knowledge, Epistemic Fluency and Reflections on Students’ Experiences. 32nd HERDSA Annual Conference, Darwin.

Grossman, P. (1990). The Making of a Teacher. Teacher Knowledge and Teacher Education. Chicago: Teacher College Press.

Hamid, S., Chang, S., & Kurnia, S. (2009). Identifying the Use of On-line Social Networking in Higher Education. The Ascilite, Auckland.

Hechter, R.P., Phyfe, L.D., & Vermette, L.A. (2012). Integrating Technology in Education: Moving the TPCK Framework towards Practical Applications. Education Research and Perspectives, 39(1), 136-152.

Hue, L.T., & Jalil, H.A. (2013). Attitudes towards ICT Integration into Curriculum and Usage among University Lecturers in Vietnam. International Journal of Instruction, 6(2), 53-66.

Jump, L. (2011). Why University Lecturers Enhance their Teaching through the Use of Technology: A Systematic Review. Learning, Media and Technology, 36(1), 55-68. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2010.521509

Kali, Y., Goodyear, P., & Markauskaite, L. (2011). Researching Design Practices and Design Cognition: Contexts, Experiences and Pedagogical Knowledge-in-pieces. Learning, Media and Technology, 36(2), 129-149. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2011.553621

Kirkwood, A., & Price, L. (2014). Technology-enhanced Learning and Teaching in Higher education: what is ‘enhanced’ and how do we know? A Critical Literature Review. Learning, Media and Technology, 39(1), 6-36. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2013.770404

Krücken, G. (2014). Higher Education Reforms and Unintended Consequences: A Research Agenda. Studies in Higher Education, 39(8), 1439-1450. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.949539

Laurillard, D. (2012). Teaching as a Design Science. Building Pedagogical Patterns for Learning and Technology. London: Routledge.

MacLean, P., & Scott, B. (2011). Competencies for Learning Design: A Review of the Literature and a Proposed Framework. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(4), 557-572. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01090.x

Marcelo, C., Yot, C., & Mayor, C. (2011). Alacena, an Open Learning Design Repository for University Teaching. Comunicar, 37(XIX), 37-44. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C37-2011-02-03

Marcelo, C., Yot, C., Mayor, C., Sánchez, M., Murillo, P., Sánchez, J., & Pardo, A. (2014). Las actividades de aprendizaje en la enseñanza universitaria: ¿Hacia un aprendizaje autónomo de los alumnos? Revista de Educación, 363, 334-359. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2012-363-191

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. (2006). Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017-1054.

Ng’ambi, D. (2013). Effective and Ineffective Uses of Emerging Technologies: Towards a Transformative Pedagogical Model. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(4), 652-661. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12053

Roblyer, M.D., Mcdaniel, M., Webb, M., Herman, J., & Witty, J.V. (2010). Findings on Facebook in Higher Education: A Comparison of College Faculty and Student Uses and Perceptions of Social Networking Sites. Internet and Higher Education, 13(3), 134-140. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.03.002

Shelton, C. (2014). Virtually Mandatory: A Survey of How Discipline and Institutional Commitment Shape University Lecturers’ Perceptions of Technology. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(4), 748-759. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12051

Shulman, L. (1986). Those who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4-14.

Tejedor, F.J., García-Valcárcel, A., & Prada, S. (2009). Medida de actitudes del profesorado universitario hacia la integración de las TIC. Comunicar, 33, 115-124. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/c33-2009-03-002

Yeh, Y.F., Hsu, Y.S., Wu, H.K., Hwang, F.K., & Lin, T.C. (2014). Developing and Validating Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge-practical (TPACK-practical) through the Delphi Survey Technique. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(4), 707-722. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12078

Document information

Published on 30/06/15

Accepted on 30/06/15

Submitted on 30/06/15

Volume 23, Issue 2, 2015

DOI: 10.3916/C45-2015-12

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?