Cynthiazhang (talk | contribs) m (Tag: Visual edit) |

Cynthiazhang (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

== Methods == | == Methods == | ||

| − | ==== Species Occurrence Data and | + | ==== Species Occurrence Data and Group ==== |

| − | + | [[File:Draft_Zhang_249907814_7551_fig 1 (1).png]] | |

| − | + | ||

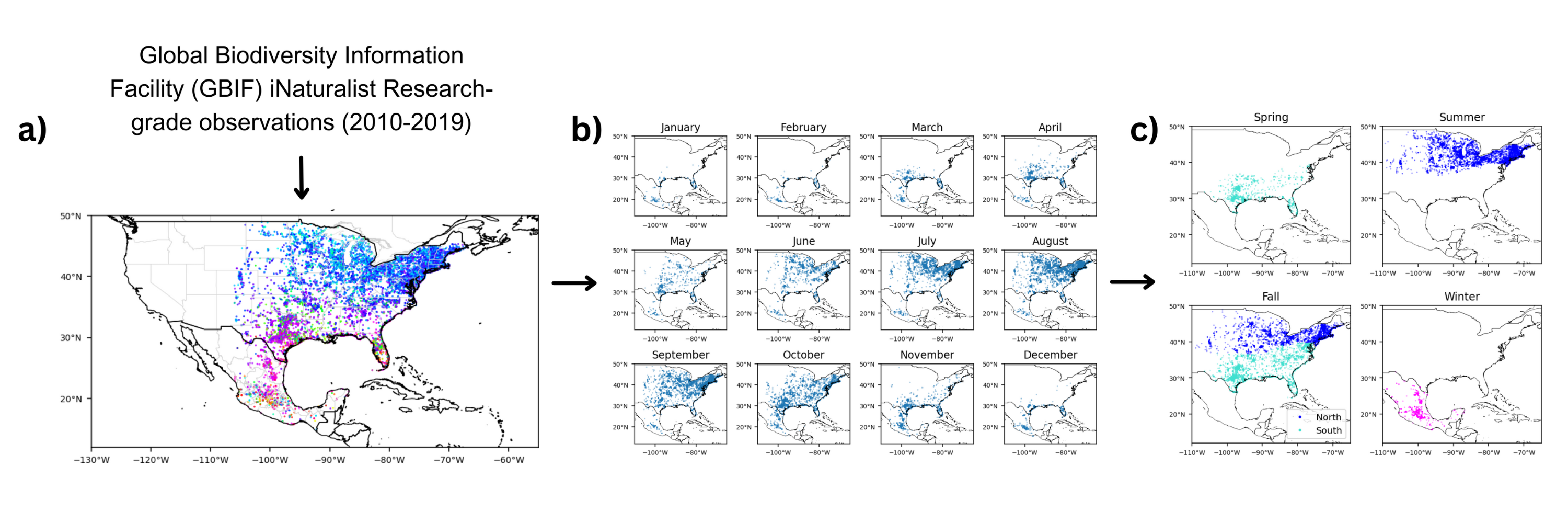

'''''Figure 3. (a) Annual monarch butterfly distribution''''' ''from GBIF iNaturalist Research-grade observations (2010-2019) was grouped by '''(b) monthly distribution''' (Spring: Mar-May, Summer: May-Aug, Fall: Sep-Nov, Winter: Nov-Mar), then categorized into '''(c) five groups''' based on season, region, and grouping patterns from previous studies (11, 15). Figure generated by student author.'' | '''''Figure 3. (a) Annual monarch butterfly distribution''''' ''from GBIF iNaturalist Research-grade observations (2010-2019) was grouped by '''(b) monthly distribution''' (Spring: Mar-May, Summer: May-Aug, Fall: Sep-Nov, Winter: Nov-Mar), then categorized into '''(c) five groups''' based on season, region, and grouping patterns from previous studies (11, 15). Figure generated by student author.'' | ||

| Line 33: | Line 32: | ||

==== Convolutional Neural Network Species Distribution Models ==== | ==== Convolutional Neural Network Species Distribution Models ==== | ||

| + | [[File:Draft_Zhang_249907814_7310_fig 2.png]] | ||

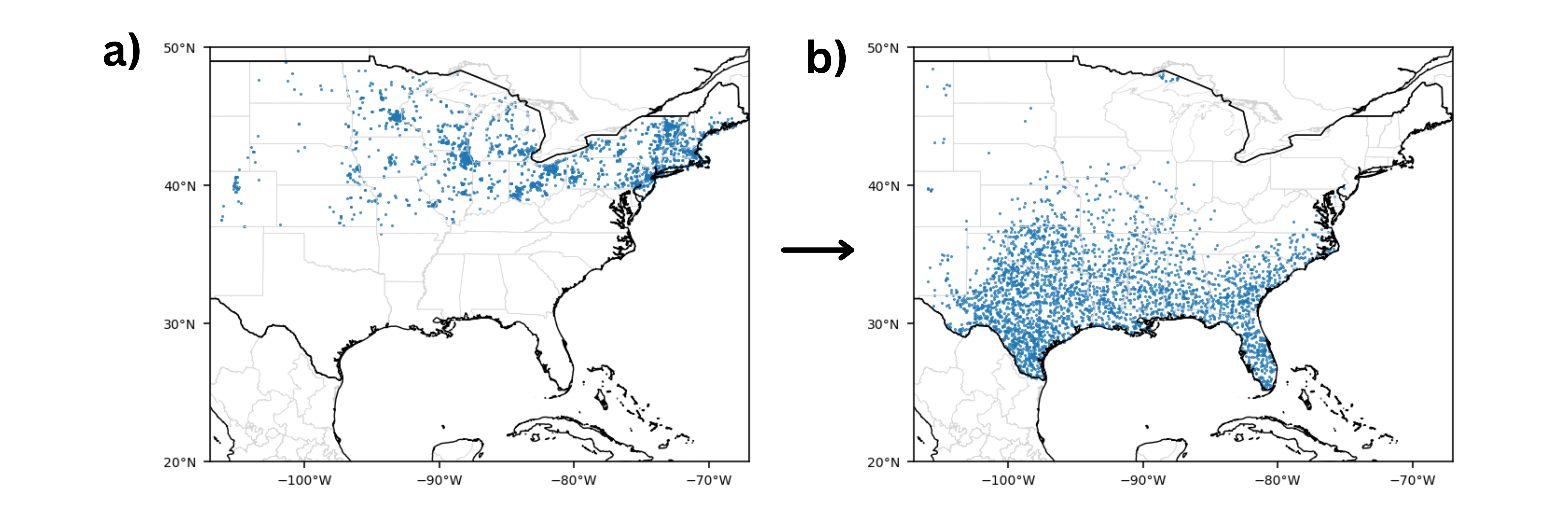

| + | Figure 4. Examples of (a) presences during the summer season (2010-2019) and corresponding (b) pseudo-absences generated. Figure generated by author. | ||

| + | |||

For each of the five groups, pseudo-absence points were generated using a modified Surface Range Envelope (SRE) method at a 1:1 ratio with presence points, which was shown by Barbet-Massin et al. (2012) as the optimal method to maximize specificity or the true negative rate required for species conservation and reserve planning (24). Typically the SRE method randomly selects points outside of an envelope representing the species’ suitable range, where the envelope is defined by the maximum and minimum values of the environmental variables recorded at all species presence locations. However, this study uses environmental rasters around occurrence points, so pseudo-absence points were instead randomly selected from points with average environmental raster values falling outside the maximum and minimum values of those recorded at all species presences. The area of pseudo-absence selection was the contiguous United States west of the 106°W boundary for the Spring, Summer, Fall-North, and Fall-South groups; and Mexico for the Winter group. | For each of the five groups, pseudo-absence points were generated using a modified Surface Range Envelope (SRE) method at a 1:1 ratio with presence points, which was shown by Barbet-Massin et al. (2012) as the optimal method to maximize specificity or the true negative rate required for species conservation and reserve planning (24). Typically the SRE method randomly selects points outside of an envelope representing the species’ suitable range, where the envelope is defined by the maximum and minimum values of the environmental variables recorded at all species presence locations. However, this study uses environmental rasters around occurrence points, so pseudo-absence points were instead randomly selected from points with average environmental raster values falling outside the maximum and minimum values of those recorded at all species presences. The area of pseudo-absence selection was the contiguous United States west of the 106°W boundary for the Spring, Summer, Fall-North, and Fall-South groups; and Mexico for the Winter group. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Draft_Zhang_249907814_6411_fig 3.png]] | ||

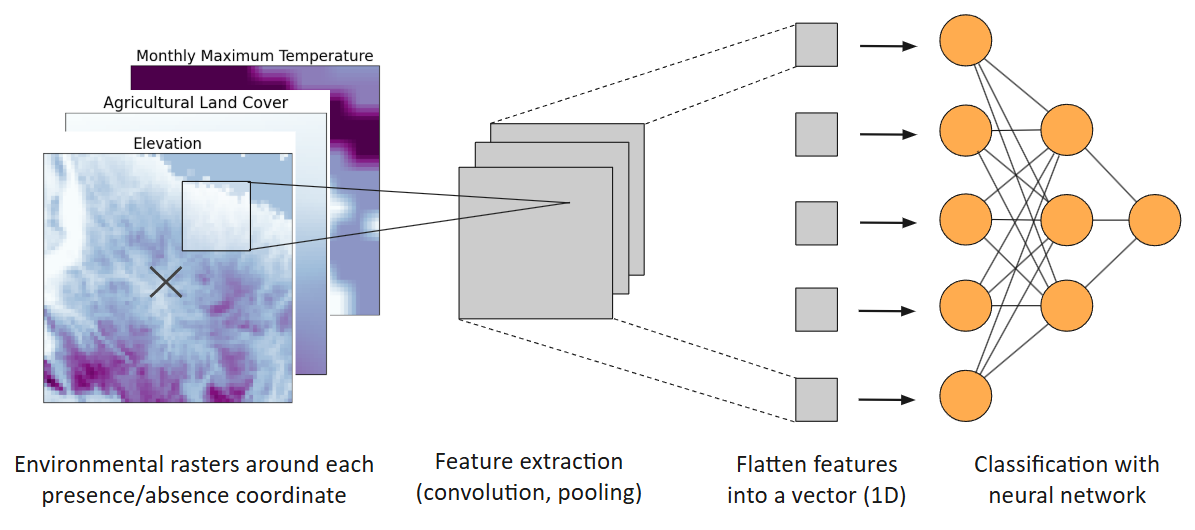

| + | Figure 5. Diagram of convolutional neural network species distribution model. Figure generated by student author. | ||

Presence and pseudo-absence points were split into training (90%) and test (10%) sets. For each occurrence (presence or absence) point, its surrounding 64 x 64 pixel environmental neighborhood was extracted, with each pixel representing 1 km of data. For each occurrence, the input environmental tensor has a size of 64 x 64 x 8 pixels, containing a layer for each of the 8 environmental raster variables (19), where glyphosate use served as a predictor in only the United States groups (Spring, Summer, Fall-North, Fall-South), while forested land cover served as a predictor in only the Winter group. These 3-dimensional tensors underwent transformations, including convolution and pooling, to detect key features of the environmental rasters, creating 2-dimensional feature maps of lower dimensionality (19). The resulting 2-dimensional feature maps were further flattened into 1-dimensional feature vectors, which are fitted into dense neural networks with the binary cross-entropy loss function (Fig. 1). The ReLU and sigmoid activation functions were used for hidden layers and the output layer, respectively. The number of nodes and hidden layers for dense neural networks will be adjusted to decrease the loss of the training and test set and to maximize the CNN-SDMs’ true skill statistic (TSS) and area under curve of the receiver operating characteristic (AUC ROC) scores, which use sensitivity, or true positive rate, and specificity, or true negative rate, to indicate the ability of a binary classification model to correctly distinguish between positive and negative classes. | Presence and pseudo-absence points were split into training (90%) and test (10%) sets. For each occurrence (presence or absence) point, its surrounding 64 x 64 pixel environmental neighborhood was extracted, with each pixel representing 1 km of data. For each occurrence, the input environmental tensor has a size of 64 x 64 x 8 pixels, containing a layer for each of the 8 environmental raster variables (19), where glyphosate use served as a predictor in only the United States groups (Spring, Summer, Fall-North, Fall-South), while forested land cover served as a predictor in only the Winter group. These 3-dimensional tensors underwent transformations, including convolution and pooling, to detect key features of the environmental rasters, creating 2-dimensional feature maps of lower dimensionality (19). The resulting 2-dimensional feature maps were further flattened into 1-dimensional feature vectors, which are fitted into dense neural networks with the binary cross-entropy loss function (Fig. 1). The ReLU and sigmoid activation functions were used for hidden layers and the output layer, respectively. The number of nodes and hidden layers for dense neural networks will be adjusted to decrease the loss of the training and test set and to maximize the CNN-SDMs’ true skill statistic (TSS) and area under curve of the receiver operating characteristic (AUC ROC) scores, which use sensitivity, or true positive rate, and specificity, or true negative rate, to indicate the ability of a binary classification model to correctly distinguish between positive and negative classes. | ||

Revision as of 20:50, 7 July 2025

Abstract

Eastern migratory monarch butterflies have declined by over 80% since the 1990s and have a 56–74% chance of extinction by 2080, which has been attributed to climate change and habitat loss. As a native migratory insect widely distributed across North America, the monarch butterfly serves as a valuable bioindicator for environmental change and conservation needs. However, there is still a lack of understanding of the spatiotemporal nature, relative importance, and future risks of individual threats due to the monarch’s multi-generational and vast annual cycle. Given the monarch's distinct ecological niche and sensitivity to environment conditions for migration, this study used convolutional neural network species distribution models (CNN-SDMs), which enhance occurrence predictions by capturing the surrounding environmental neighborhood, to analyze suitability predictors of monarch butterflies and explain their contributions at each step of the migratory route. The models were projected onto future climate and land cover scenarios in 2061–2080. Monthly maximum and minimum temperature ranked highest in feature importance across the migratory cycle, while vegetative land cover became ranked high in importance for the overwintering monarch population and future breeding habitat forecasted to shift northward. This niche-switching suggests that conservation efforts to facilitate the northward expansion of suitable habitat and the cultivation of nectar sources near hibernating colonies will be critical with growing climate impact and emissions. This study was the first to establish a CNN-based predictive spatiotemporal model of monarch butterflies and incorporate a comprehensive set of environmental predictors to evaluate potential threats to the monarch decline.

Introduction

Biodiversity across the globe is declining at an alarming rate, with wildlife populations having declined 73% between 1970 and 2020 and one million species currently at risk of extinction (1, 2). Migratory species are particularly vulnerable due to their reliance on and interactions with multiple habitats throughout their seasonal movements, and over one-fifth are now threatened with extinction (3). Because of their wide dispersal, migratory species provide vital ecosystem services across and also serve as valuable bioindicators for environmental change, including habitat degradation and climatic shifts (4). Thus, effective conservation for migratory species also indirectly benefits countless other species and ecosystems falling in the migratory range (4, 5).

One of the most culturally and ecologically significant migratory species in North America is the eastern migratory monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus). As a native species across Canada, the United States, and Mexico, monarch butterflies play a crucial role in pollination, the food web, and biodiversity preservation (6). However, the monarch butterfly population has plummeted by over 80% since the 1990s, from 18.19 hectares of occupied overwintering habitat in 1996 to less than two hectares in recent years (7). Due to their persistent decline, migratory monarch butterflies have been listed as endangered and vulnerable in the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species in 2022 and 2023, respectively (8). Although climate change and habitat loss have been identified as the primary drivers of the decline, a comprehensive understanding of the spatiotemporal nature, relative importance, and future risks of these threats remains uncertain due to the monarch’s vast geographic distribution and multi-generational annual cycle as highlighted in the systematic review of 115 peer-reviewed literature on the threats to monarch butterfly reproduction and survival from Wilcox et al. (2019) (9).

The eastern monarch butterfly undergoes a biannual migration between overwintering forests in Mexico and breeding habitat in the United States and Canada through multiple reproduction cycles. Starting in the central highland forests in the States of Michoacán and Mexico, one overwintering generation of monarch butterflies hibernate from early November to late March in a reproductive diapause and a low metabolic state (10). In spring, monarch butterflies begin to migrate northward and enter the southern United States to produce the first breeding generation (11). In summer, this generation reaches the Northeast and Midwest of the United States and parts of southern Canada, producing a second, third, and potentially fourth generation before migrating back to the South in autumn, with a potential fifth generation before cycling back to Mexico before winter (11).

Different climate- and habitat-related threats have been proposed to negatively affect monarch butterflies along their migratory route including (a) weather extremes and severe winter storms, which have led to large-scale mortality events with death rates as high as 70-80% (10); (b) habitat loss of overwintering grounds in Mexico due to deforestation with large portions of core areas in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve (MBBR)—44% between 1971 and 1999 and 10% between 2001 and 2009—have already been degraded or eliminated (12, 13); (c) lack of availability of milkweed in breeding areas due to the use of the herbicide glyphosate, also known as Roundup, which has contributed to a 31% decline in non-agricultural milkweed and an 81% decline in agricultural milkweed between 1999 and 2010, or a loss of more than 1 billion milkweed plants (14, 15).

Thus, capturing the monarch’s seasonal migration patterns and corresponding impacts of climate and habitat factors is critical to understanding ecological requirements throughout their annual cycle. To model species distribution for each step of the migration, past studies have used ecological niche models or species distribution models (SDMs), which finds relationships between environmental raster data—values of environmental variables that are stored in gridded pixels each linked to a specific geographical coordinate—and species observation data—presence or absence at a geographic coordinate (16, 17, 18, 15). Recently, a new type of SDMs using convolutional neural networks (CNN-SDMs) has been introduced, which was shown to improve SDM performance compared to other machine learning techniques (19, 20). Since CNNs are typically used for image recognition by extracting features from images, its application to SDMs can help take into account the environmental neighborhood, surpassing the predictive accuracy of deep neural networks, boosted trees, and random forests when predicting the occurrence probabilities of 4,520 plant species in France, with significant gains for rare species (19). Furthermore, CNN-SDMs overcome the constraints of MaxEnt, one of the most popular SDM methods, particularly its limited ability to predict occurrences at finer resolutions and along bodies of water (20). Therefore, given the monarch's distinct ecological niche and sensitivity to environment conditions for migration, CNN-SDMs may enhance occurrence predictions by capturing the local environmental context.

In this study, CNN-SDMs for monarch butterflies were developed for five stages of the migration cycle to investigate the spatiotemporal impact of climate and habitat factors on the monarch decline and evaluate their relative importances. The models were subsequently projected onto future climate and land cover conditions for the years 2061–2080 to assess future risks.

Methods

Species Occurrence Data and Group

Figure 3. (a) Annual monarch butterfly distribution from GBIF iNaturalist Research-grade observations (2010-2019) was grouped by (b) monthly distribution (Spring: Mar-May, Summer: May-Aug, Fall: Sep-Nov, Winter: Nov-Mar), then categorized into (c) five groups based on season, region, and grouping patterns from previous studies (11, 15). Figure generated by student author.

Figure 3. (a) Annual monarch butterfly distribution from GBIF iNaturalist Research-grade observations (2010-2019) was grouped by (b) monthly distribution (Spring: Mar-May, Summer: May-Aug, Fall: Sep-Nov, Winter: Nov-Mar), then categorized into (c) five groups based on season, region, and grouping patterns from previous studies (11, 15). Figure generated by student author.

Presence-only monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) occurrence data in the United States and Mexico from January 2010 to December 2019 was obtained from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) with their corresponding observation dates and latitude and longitude coordinates (GBIF.org (21 November 2024) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.ybejfm). The dataset includes 46,588 occurrences from iNaturalist Research-grade Observations, which were selected and used for this study. Data points west of 106°W were dropped to eliminate potential presences of the western migratory monarch butterfly population that mostly resides west of the Rocky Mountains and overwinters along the coast of California.

The resulting presences were plotted by month, then divided according to season, region, and grouping patterns from previous studies (11, 15) to form five spatiotemporal groups that indicate distinct steps of the monarch annual cycle: Spring (March–May, southern United States), Summer (May–August, northern United States), Fall-North (September–November, northern United States), Fall-South (September–November, southern United States), and Winter (November–March, Mexico) (Fig. 1). The southern United States represents West Virginia, Kentucky, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and the states south of them. The northern United States represents the remaining states east of 106°W.

Environmental Raster Data

Elevation and historical monthly weather data for minimum temperature, maximum temperature, and total precipitation were obtained from the WorldClim database at a 10 arc-min resolution for the period 2010–2019. County-level annual glyphosate use for the period 2010–2019 was acquired from United States Geological Survey (USGS) National Water-Quality Assessment (NAWQA) Pesticide National Synthesis Project EPest-high estimates, where unreported pesticide use was treated as missing data and filled with pesticide-by-crop use rates from neighboring or regional Crop Reporting Districts (CRDs). Land cover percentages for a 0.25° spatial resolution for total forested land (forested primary land, potentially forested secondary land), total non-forested land (non-forested primary land, potentially non-forested secondary land), agricultural land (managed pasture, rangeland, C3 annual crops, C3 perennial crops), and urban land were acquired from the Land-Use Harmonization 2 (LUH2) v2h Release for the period 2010–2015. Land cover data for 2015 were used for the years 2016–2019.

Undefined values, like sea pixels, were assigned distinct numerical values under the minimum value of the valid data to avoid potential errors (19). The spatial resolution of each environmental raster data product was standardized to 1 km.

Convolutional Neural Network Species Distribution Models

Figure 4. Examples of (a) presences during the summer season (2010-2019) and corresponding (b) pseudo-absences generated. Figure generated by author.

Figure 4. Examples of (a) presences during the summer season (2010-2019) and corresponding (b) pseudo-absences generated. Figure generated by author.

For each of the five groups, pseudo-absence points were generated using a modified Surface Range Envelope (SRE) method at a 1:1 ratio with presence points, which was shown by Barbet-Massin et al. (2012) as the optimal method to maximize specificity or the true negative rate required for species conservation and reserve planning (24). Typically the SRE method randomly selects points outside of an envelope representing the species’ suitable range, where the envelope is defined by the maximum and minimum values of the environmental variables recorded at all species presence locations. However, this study uses environmental rasters around occurrence points, so pseudo-absence points were instead randomly selected from points with average environmental raster values falling outside the maximum and minimum values of those recorded at all species presences. The area of pseudo-absence selection was the contiguous United States west of the 106°W boundary for the Spring, Summer, Fall-North, and Fall-South groups; and Mexico for the Winter group.

Figure 5. Diagram of convolutional neural network species distribution model. Figure generated by student author.

Figure 5. Diagram of convolutional neural network species distribution model. Figure generated by student author.

Presence and pseudo-absence points were split into training (90%) and test (10%) sets. For each occurrence (presence or absence) point, its surrounding 64 x 64 pixel environmental neighborhood was extracted, with each pixel representing 1 km of data. For each occurrence, the input environmental tensor has a size of 64 x 64 x 8 pixels, containing a layer for each of the 8 environmental raster variables (19), where glyphosate use served as a predictor in only the United States groups (Spring, Summer, Fall-North, Fall-South), while forested land cover served as a predictor in only the Winter group. These 3-dimensional tensors underwent transformations, including convolution and pooling, to detect key features of the environmental rasters, creating 2-dimensional feature maps of lower dimensionality (19). The resulting 2-dimensional feature maps were further flattened into 1-dimensional feature vectors, which are fitted into dense neural networks with the binary cross-entropy loss function (Fig. 1). The ReLU and sigmoid activation functions were used for hidden layers and the output layer, respectively. The number of nodes and hidden layers for dense neural networks will be adjusted to decrease the loss of the training and test set and to maximize the CNN-SDMs’ true skill statistic (TSS) and area under curve of the receiver operating characteristic (AUC ROC) scores, which use sensitivity, or true positive rate, and specificity, or true negative rate, to indicate the ability of a binary classification model to correctly distinguish between positive and negative classes.

To analyze the threats to monarch butterflies systematically across their annual cycle, a monarch butterfly CNN-SDM, as described above, was created for each of the five groups. To explain the ecological niche for each CNN-SDM, permutation importances were calculated for each environmental raster variable by randomly shuffling feature values and measuring the resulting decrease in accuracy score. Additionally, Shapley Additive Explanation (SHAP) values were calculated to assess each feature’s contribution on the model output for high and low feature values. Since the output is the probability of monarchs being present, the SHAP values will be a decimal from 0 to 1. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) tests and the Holm-Bonferroni post-hoc test were performed to assess significance in permutation importance between groups for each variable.

3 Bibliography

4 Acknowledgments

5 References

Document information

Published on 22/09/25

Submitted on 07/07/25

Volume 7, 2025

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?