m (Cinmemj moved page Draft Samper 987121664 to Iaconeta et al 2020a) |

|||

| (116 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | < | + | ''"Non quia difficilia sunt non audemus, sed quia non audemus difficilia sunt."''<br /> |

| + | Seneca (CIV,26) | ||

| + | =Acknowledgement= | ||

| − | + | It has been a long and challenging way, but, fortunately, during these years I have met many people, who encouraged me to go ahead and taught me not to give up. I am very grateful for this. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | I would like to thank my advisor, Prof. Eugenio Oñate, for giving me the opportunity to study in CIMNE. During the years spent at this research center, I could find many sources of knowledge and inspiration, that I will take with me wherever I will be in the future. A special thanks goes to my co-advisor, Prof. Antonia Larese, for introducing me to the field of computational mechanics and for supporting me in the most important moments of this experience. I would like to thank those colleagues of CIMNE, who with great patience, helped me dedicating part of their time, Riccardo, Stefano, Charlie, Pablo, Lorenzo, Jordi and Alessandro. | |

| − | + | I would like to thank Prof. Massimiliano Cremonesi for his supervision and kind welcome during my visit at the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, at Politecnico di Milano. I want to express my gratitude to Dr. Fausto Di Muzio for his kindness and warming welcome during my brief stay at Nestlé. This experience allowed me to look at the research world from a different perspective and to recognize how important is to conjugate fundamental research with more practical applied aspects. In this respect, I would like to thank Dr. Julien Dupas for his collaboration and support in providing some experimental data. | |

| − | + | I have been enough fortunate to be part of the European project T-MAPPP, which greatly contributed not only to the development of my technical knowledge, but also of my soft skills. I would like to thank all the researchers involved in the project. In particular, Prof. Stefan Luding and Prof. Vanessa Magnanimo, for the valuable discussions and the interest shown in my work; Yousef, Kostas, Kianoosh, Behzad, Somik, Sasha and Niki, because without them it would have not been the same. | |

| − | + | A special thank you goes to all the people who made my day with a smile and let me see the positive side in any situation. Thank you Josie, Manu, Edu, Vicente, Nanno, Giulia, Eugenia and Alessandra. | |

| − | + | Last but not least, all my gratitude goes to my family: Marta, Gianni and Claudia, for their wholehearted support and love. | |

| − | + | The research was supported by the Research Executive Agency through the T-MAPPP project (FP7 PEOPLE 2013 ITN-G.A.n607453). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | == | + | =Resumen= |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | El manejo, el transporte y el procesamiento de materiales granulares y en polvo son operaciones fundamentales en una amplia gama de procesos industriales y de fenómenos geofísicos. Los materiales particulados, que pueden encontrarse en la naturaleza, generalmente están caracterizados por un tamaño de grano, que puede variar entre varios órdenes de magnitud: desde el nanómetro hasta el orden de los metros. En función de las condiciones de fracción volumétrica y de deformación de cortante, los materiales granulares pueden tener un comportamiento diferente y a menudo pueden convertirse en un nuevo estado de materia con propiedades de sólidos, de líquidos y de gases. Como consecuencia, tanto el análisis experimental como la simulación numérica de medios granulares es aún una tarea compleja y la predicción de su comportamiento dinámico representa aun hoy día un desafío muy importante. El principal objetivo de esta monografía es el desarrollo de una estrategia numérica con la finalidad de estudiar el comportamiento macroscópico de los flujos de medios granulares secos en régimen cuasiestático y en régimen dinámico. El problema está definido en el contexto de la mecánica de medios continuos y las leyes de gobierno están resueltas mediante un formalismo Lagrangiano. El Metodo de los Puntos Materiales (MPM), método basado en el concepto de discretización del cuerpo en partículas, se ha elegido por sus características que lo convierten en una técnica apropiada para resolver problemas en grandes deformaciones donde se tienen que utilizar complejas leyes constitutivas. En el marco del MPM se ha implementado una formulación irreducible que usa una ley constitutiva de Mohr-Coulomb y que tiene en cuenta no-linealidades geométricas. La estrategia numérica está verificada y validada con respecto a tests de referencia a resultados experimentales disponibles en la literatura. También, se ha implementado una formulación mixta para resolver los casos de flujo granular en condiciones no drenadas. Por último, la estrategia MPM desarrollada se ha utilizado y evaluado con respecto a un estudio experimental realizado para caracterizar la fluidez de diferentes tipologías de azúcar. Finalmente se presentan unas observaciones y una discusión sobre las capacidades y las limitaciones de esta herramienta numérica y se describen las bases para una investigación futura. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | == | + | =Abstract= |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Bulk handling, transport and processing of granular materials and powders are fundamental operations in a wide range of industrial processes and geophysical phenomena. Particulate materials, which can be found in nature, are usually characterized by a grain size which can range across several scales: from nanometre to the order of metre. Depending on the volume fraction and on the shear strain conditions, granular materials can have different behaviours and often can be expressed as a new state of matter with properties of solids, liquids and gases. For the above reasons, both the experimental and the numerical analysis of granular media is still a difficult task and the prediction of their dynamic behaviour still represents, nowadays, an important challenge. The main goal of the current monograph is the development of a numerical strategy with the objective of studying the macroscopic behaviour of dry granular flows in quasi-static and dense flow regime. The problem is defined in a continuum mechanics framework and the balance laws, which govern the behaviour of a solid body, are solved by using a Lagrangian formalism. The Material Point Method (MPM), a particle-based method, is chosen due to its features which make it very suitable for the solution of large deformation problems involving complex history-dependent constitutive laws. An irreducible formulation using a Mohr-Coulomb constitutive law, which takes into account geometric non-linearities, is implemented within the MPM framework. The numerical strategy is verified and validated against several benchmark tests and experimental results, available in the literature. Further, a mixed formulation is implemented for the solution of granular flows that undergo undrained conditions. Finally, the developed MPM strategy is used and tested against the experimental study performed for the characterization of the flowability of several types of sucrose. The capabilities and limitations of this numerical strategy are observed and discussed and the bases for future research are outlined. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | == | + | =List of Symbols= |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | {| class="floating_tableSCP" style="text-align: left; margin: 1em auto;border-top: 2px solid;border-bottom: 2px solid;min-width:50%;" |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | | <math display="inline">t</math>: | |

| − | + | | time; | |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | | <math display="inline">\phi </math>: | |

| − | + | | internal friction angle; | |

| − | == | + | |- |

| − | + | | <math display="inline">d </math>: | |

| − | + | | particle diameter; | |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | | <math display="inline">\rho _p</math>: | |

| − | * | + | | particle density; |

| − | * | + | |- |

| + | | <math display="inline">\dot{\boldsymbol{\gamma }}</math>: | ||

| + | | shear rate; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\Omega ^0</math>: | ||

| + | | undeformed configuration; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\varphi \left(\Omega \right)^n</math> or <math display="inline">\varphi _n</math>: | ||

| + | | deformed configuration at time <math display="inline">t^n</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\varphi \left(\Omega \right)^{n+1}</math> or <math display="inline">\varphi _{n+1}</math>: | ||

| + | | deformed configuration at time <math display="inline">t^{n+1}</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\chi _p</math>: | ||

| + | | characteristic function in the Generalized Interpolation Material Point Method; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">V_p </math>: | ||

| + | | particle volume; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\Omega _p</math>: | ||

| + | | current particle domain; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\Omega </math>: | ||

| + | | current domain occupied by the continuum; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> N_I(\boldsymbol{x})</math>: | ||

| + | | shape function relative to node <math display="inline">I</math> evaluated at position at position <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{x}</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\nabla N_I(\boldsymbol{x})</math>: | ||

| + | | gradient shape function relative to node <math display="inline">I</math> evaluated at position at position <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{x}</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\widehat{\nabla N_I}(\boldsymbol{x})</math>: | ||

| + | | gradient shape function from node-based calculation; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\overline{\nabla N_I}(\boldsymbol{x})</math>: | ||

| + | | gradient shape function evaluated in Dual Domain Material Point Method; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)_p</math>: | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)</math> relative to the material point <math display="inline">p</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)_I</math>: | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)</math> relative to the node <math display="inline">I</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)_I^n</math>: | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)</math> relative to the node <math display="inline">I</math> at time <math display="inline">t^n</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">^{it}\left(\cdot \right)_I^n</math>: | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)</math> relative to the node <math display="inline">I</math> at time <math display="inline">t^n</math> and iteration <math display="inline">it</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{u}</math>: | ||

| + | | displacement vector; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\Delta \boldsymbol{u}</math>: | ||

| + | | increment displacement vector; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{v}</math>: | ||

| + | | velocity vector; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{a}</math>: | ||

| + | | acceleration vector; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">p</math>: | ||

| + | | pressure; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{q}</math>: | ||

| + | | momentum vector; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{f}</math>: | ||

| + | | inertia vector; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">m</math>: | ||

| + | | mass; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\lambda , \zeta \right)</math>: | ||

| + | | stability parameters of Bossak method; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\delta \boldsymbol{u}</math>: | ||

| + | | vector of unknown incremental displacement; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \mathbf{K}^{tan} </math>: | ||

| + | | tangent matrix of the linearised system of equation; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \mathbf{R}</math>: | ||

| + | | residual vector of the linearised system of equation; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\xi _p, \eta _p\right)</math>: | ||

| + | | local coordinates relative to a material point; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\beta </math>: | ||

| + | | on-negative locality coefficient in Local Maximum Entropy technique; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">h</math>: | ||

| + | | measure of nodal spacing in Local Maximum Entropy technique; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\gamma </math>: | ||

| + | | dimensionless parameter in Local Maximum Entropy technique; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{F}</math>: | ||

| + | | total deformation gradient; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">J</math>: | ||

| + | | determinant of the total deformation gradient; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{f}</math>: | ||

| + | | incremental deformation gradient; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{P}</math>: | ||

| + | | First Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{S}</math>: | ||

| + | | Second Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{\tau }</math>: | ||

| + | | Kirchhoff stress tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{\sigma }</math>: | ||

| + | | Cauchy stress tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\Psi </math>: | ||

| + | | specific strain energy function; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{Q}</math>: | ||

| + | | rotation tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{R}</math>: | ||

| + | | rotation tensor from polar decomposition of <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{F}</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{U}</math>: | ||

| + | | right stretch tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{V}</math>: | ||

| + | | left stretch tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{C}</math>: | ||

| + | | right Cauchy-Green tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{I_C}</math>: | ||

| + | | first principal invariant of <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{C}</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{I_C^*}</math>: | ||

| + | | first invariant of <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{C}</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{b}</math>: | ||

| + | | left Cauchy-Green tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\lambda , \mu \right)</math>: | ||

| + | | Lame constant; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">K</math>: | ||

| + | | bulk modulus; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">G</math>: | ||

| + | | shear modulus; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathrm{C}^{CE}</math>: | ||

| + | | material incremental constitutive tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathrm{C}^{\tau }</math>: | ||

| + | | spatial incremental constitutive tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{I}</math>: | ||

| + | | symmetric second order unit; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathrm{I}</math>: | ||

| + | | fourth order identity tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathrm{I}_s</math>: | ||

| + | | fourth order symmetric identity tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathrm{I}_d</math>: | ||

| + | | fourth order deviatoric projector tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{d}</math>: | ||

| + | | symmetrical spatial velocity gradient; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{D}</math>: | ||

| + | | rate of deformation tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{W}</math>: | ||

| + | | spin tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{L}</math>: | ||

| + | | velocity gradient tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)_{vol}</math>: | ||

| + | | volumetric part of <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)_{dev}</math>: | ||

| + | | deviatoric part of <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">dev\left(\cdot \right)</math>: | ||

| + | | deviatoric part of <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)^e</math>: | ||

| + | | elastic part of <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)^p</math>: | ||

| + | | plastic part of <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\overline{\cdot }\right)</math>: | ||

| + | | volume preserving part of <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\sigma _Y</math>: | ||

| + | | flow stress; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">H</math>: | ||

| + | | isotropic hardening; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\alpha </math>: | ||

| + | | hardening parameter; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\gamma </math>: | ||

| + | | plastic multiplier; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{n}</math>: | ||

| + | | unit vector of <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{\tau }_{dev}</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)^{trial}</math>: | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)</math> in trial state; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">tr\left(\cdot \right)</math>: | ||

| + | | trace of <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathrm{g}</math>: | ||

| + | | metric tensor in current configuration; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathrm{C}^{ep}</math>: | ||

| + | | spatial algorithmic elastoplastic moduli; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">c</math>: | ||

| + | | cohesion; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\psi </math>: | ||

| + | | dilation angle; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{\sigma }_n</math>: | ||

| + | | normal stress; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{\epsilon }^e</math>: | ||

| + | | principal Hencky strain; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathrm{a}</math>: | ||

| + | | Hencky elastic constitutive tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathrm{a}^{ep}</math>: | ||

| + | | elasto-plastic fourth order constitutive tensor; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathrm{C}^{cep}</math>: | ||

| + | | consistent elasto-plastic tangent; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{\lambda }</math>: | ||

| + | | eigenvalues vector of <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{b}</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{n}</math>: | ||

| + | | eigenvector vector of <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{b}</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{m}</math>: | ||

| + | | eigenbases vector of <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{b}</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{N}</math>: | ||

| + | | eigenvector vector of <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{C}</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{M}</math>: | ||

| + | | eigenbases vector of <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{C}</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \mathcal{B} </math>: | ||

| + | | body; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \mathcal{E} </math>: | ||

| + | | 3D Euclidean space; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathcal{R}^3 </math>: | ||

| + | | real coordinate space in 3D; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\rho </math>: | ||

| + | | mass density; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\rho _0</math>: | ||

| + | | mass density in underformed configuration; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{b}</math>: | ||

| + | | body force; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">g</math>: | ||

| + | | gravity; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\varphi (\partial \Omega _N)</math>: | ||

| + | | Neumann boundary in deformed configuration; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\varphi (\partial \Omega _D)</math>: | ||

| + | | Dirichlet boundary in deformed configuration; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \boldsymbol{\overline{t}} </math>: | ||

| + | | prescribed normal tension on Neumann boundary; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \boldsymbol{\overline{u}} </math>: | ||

| + | | prescribed displacement on Dirichlet boundary; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{w}</math>: | ||

| + | | displacement weight function; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">q</math>: | ||

| + | | pressure weight function; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathcal{V}</math>: | ||

| + | | displacement space; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathcal{V}_{h}</math>: | ||

| + | | displacement finite element space; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)_h</math>: | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)</math> in the finite element space; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathcal{B}_h</math>: | ||

| + | | geometrical representation of <math display="inline">\mathcal{B}</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \Omega _p </math>: | ||

| + | | finite volume assigned to a material point; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathbf{\mathbf{H}}^{1}(\mathcal{B})</math>: | ||

| + | | Hilbert space; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">dv</math>: | ||

| + | | differential volume in deformed configuration; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">da</math>: | ||

| + | | differential boundary surface in deformed configuration; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">dV</math>: | ||

| + | | differential volume in undeformed configuration; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\nabla _X\left(\cdot \right)</math>: | ||

| + | | material gradient operator; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\nabla _x\left(\cdot \right)</math>: | ||

| + | | spatial gradient operator; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\nabla \left(\cdot \right)^s</math>: | ||

| + | | symmatric part of <math display="inline">\left(\cdot \right)</math> gradient; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \mathbb{C} </math>: | ||

| + | | fourth order incremental constitutive tensor relative to <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{S}</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \widehat{\mathbb{C}} </math>: | ||

| + | | fourth order incremental constitutive tensor relative to <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{\tau }</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \overline{\widehat{\mathbb{C}}} </math>: | ||

| + | | fourth order incremental constitutive tensor relative to <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{\sigma }</math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathbf{D}</math>: | ||

| + | | matrix form of <math display="inline"> \overline{\widehat{\mathbb{C}}} </math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \mathbf{B}</math>: | ||

| + | | deformation matrix; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \mathbf{K}^{G} </math>: | ||

| + | | geometric stiffness matrix; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \mathbf{K}^{M} </math>: | ||

| + | | material stiffness matrix; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \mathbf{K}^{static} </math>: | ||

| + | | static part of <math display="inline"> \mathbf{K}^{tan} </math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \mathbf{K}^{dynamic} </math>: | ||

| + | | dynamic part of <math display="inline"> \mathbf{K}^{tan} </math>; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \mathcal{Q} </math>: | ||

| + | | pressure space; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\delta p</math>: | ||

| + | | vector of unknown pressure; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> ^m\mathbf{K}^{G} </math>: | ||

| + | | geometric stiffness matrix in mixed formulation; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> ^m\mathbf{K}^{M} </math>: | ||

| + | | material stiffness matrix in mixed formulation; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \boldsymbol{R}_{\boldsymbol{u}} </math>: | ||

| + | | residual vector relative to the momentum balance equation; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \boldsymbol{R}_p </math>: | ||

| + | | residual vector relative to the pressure continuity equation; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \boldsymbol{R}_p^{\mathrm{stab}} </math>: | ||

| + | | residual vector relative to the stabilization term; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \mathbf{M} </math>: | ||

| + | | mass matrix; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> \mathbf{M}^{\mathrm{stab}} </math>: | ||

| + | | mass matrix relative to the stabilization term; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline"> R_p^{\mathrm{stab}} </math>: | ||

| + | | residual vector relative to the stabilization term; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\alpha </math>: | ||

| + | | stabilization parameter; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\left(\mathbf{B},\mathbf{B}^* \right)</math>: | ||

| + | | mixed terms in the mixed formulation | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">d_{10}</math>: | ||

| + | | diameter at which 10% of the sample's mass is comprised of particles with a diameter less than this value; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">d_{50}</math>: | ||

| + | | diameter at which 50% of the sample's mass is comprised of particles with a diameter less than this value; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">d_{90}</math>: | ||

| + | | diameter at which 90% of the sample's mass is comprised of particles with a diameter less than this value; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathbf{D}^A</math>: | ||

| + | | matrix form of <math display="inline"> \overline{\widehat{\mathbb{C}}} </math> in axisymmetric case; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathbf{K}^{A, tan}</math>: | ||

| + | | tangent stiffness matrix in axisymmetric case; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathbf{K}^{A, G}</math>: | ||

| + | | geometric stiffness matrix in axisymmetric case; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math display="inline">\mathbf{K}^{A, M}</math>: | ||

| + | | material stiffness matrix in axisymmetric case; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

=1 Introduction= | =1 Introduction= | ||

| − | + | Bulk handling, transport and processing of particulate materials, such as, granular materials and powders, are fundamental operations in a wide range of industrial processes <span id='citeF-1'></span>[[#cite-1|[1]]] or geophysical phenomena and hazards, such as, landslides, debris flows, etc. <span id='citeF-2'></span>[[#cite-2|[2]]]. Particulate systems are difficult to handle and they can show an unpredictable behaviour, representing a great challenge in the industrial production, concerning both design and functionality of unit operations in plants, but also in the research community of Powders and Grains <span id='citeF-3'></span><span id='citeF-4'></span>[[#cite-3|[3,4]]]. Granular materials and powders consist of discrete particles such as, e.g., separate sand-grains, agglomerates (made of several primary particles), natural solid materials like sandstone, ceramics, metals or polymers sintered during additive manufacturing. The primary particles can be as small as nano-metres, micro-metres, or millimetres <span id='citeF-5'></span>[[#cite-5|[5]]] covering multiple scales in size and a variety of mechanical and other interaction mechanisms, such as, friction and cohesion <span id='citeF-6'></span>[[#cite-6|[6]]], which become more and more important the smaller the particles are. All those particle systems have a particulate, usually disordered, possibly inhomogeneous and often anisotropic micro-structure; nowadays, the research community is working actively in order to have a deeper understanding and aware knowledge of bulk behaviour affected by micro-scale parameters. Indeed, particle systems as bulk show a completely different behaviour as one would expect from the individual particles. Collectively, particles either flow like a fluid or rest static like a solid. In the former case, for rapid flows, granular materials are collisional, inertia dominated and compressible similar to a gas. In the latter case, particle aggregates are solid-like and, thus, can form, e.g., sand piles or slopes that do not move for long time. Between these two extremes, there is a third flow regime, dense and slow, characterized by the transitions (i) from static to flowing (failure, yield) or vice-versa (ii) from fluid to solid (jamming). At the particle and contact scale, the most important property of particle systems is their dissipative, frictional, and possibly cohesive nature. In this context, dissipation shall be understood as kinetic energy, at the particle scale, which converts into heat, for instance, due to plastic deformations. The transition from fluid to solid can be caused by dissipation alone, which tends to slow down motion. The transition from solid to fluid (start of flow) is due to failure and instability when dissipation is not strong enough and the solid yields and transits to a flowing regime. | |

| − | + | In this Chapter, the granular flow theory is presented more in detail and the main attempts, available in the literature, for the modelling of granular matter behaviour in the different regimes are discussed. Afterwards, objectives and layout of the current monograph are presented. | |

| − | + | ==1.1 The granular flows== | |

| − | + | The heavy involvement of particle materials in many different industrial processes makes the granular matter, nowadays, a remarkable object of study. Particulate materials exist in large quantity in nature and it is established that most of the industrial processes, such as, pharmaceutical, agricultural, chemical, just to cite a few, deal with materials that are particulate in structure. In the industrial field, dealing with processes at large scales and huge quantities of raw material, any issue, encountered in the production line, may cause losses in terms of productivity, and, thus, of money. During the last decades, it has been documented that also in processes of granular matters, a lack of knowledge implies non-optimal production quality. In older industrial surveys, Merrow <span id='citeF-7'></span>[[#cite-7|[7]]] found that the main factor causing long start-up delays in chemical plants is represented by the processing granular materials, especially due to the lack of reliable predictive models and simulations, while Ennis et al. <span id='citeF-8'></span>[[#cite-8|[8]]] reported that 40<math display="inline">%</math> of the capacity of industrial plants is wasted because of granular solid phenomena. More recently, Feise <span id='citeF-9'></span>[[#cite-9|[9]]] analysed the changes in chemical industry and predicted an increase in particulate solids usage along with new challenges due to new concepts like versatile multi-purpose plants, and fields like nano and bio-technology. For these reasons, it is clear that it is fundamental to have a better understanding of particulate materials behaviour under different conditions and to be able to improve the production quality through experimental campaigns and numerical modelling works. However, due to the wide variety of intrinsic properties of particulate materials a unified constitutive description, under any condition, has not been established yet. | |

| − | < | + | With granular flow, we refer to motions where the particle-particle interactions play an important role in determining the flow properties and the flow patterns which are quite different from those of conventional fluids. The most evident differences between granular systems and simple fluids affecting the macroscopic properties of the flow, as pointed out in <span id='citeF-10'></span>[[#cite-10|[10]]], are: |

| − | {| class=" | + | |

| + | * The ''size of grains'' is typically approximately <math display="inline">10^{18}</math> more massive and voluminous than a water molecule. As both fluid and particle motions can be studied according to the laws of classical mechanics, this is not a fundamental difference, but could represent an important factor while evaluating the applicability of continuum hypothesis, as explained below; | ||

| + | * In granular systems, when granules collide, a loss of ''kinetic energy converted in true heat'' is observed. This difference determines the main feature which deeply distinguishes the granular flows modelling from the fluid flows one; | ||

| + | * In nature, ''grains are not identical'': particle shape, particle roughness and solid density are only some of the particle properties which characterize a grain from the other. As real particles are not exactly spherical and typically the surface is rough, in grain-grain interactions frictional forces and torque are created and grains rotate during the collision. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The above comparison is useful to emphasise that the main assumptions on the basis of fluid flow modelling can not coincide with those of granular flow modelling. Further, this comparison can also be useful to set the bounds of the continuum assumptions enforceability. Three length scales have to be considered for the definition of these hypotheses. The first one is related to the particle size. Typically the value of density in grain systems is much smaller than in molecular fluids; this means that, for instance, in a cubic mm of fluids the number of molecules is much higher than the number of grains. If a macroscopic quantity changes significantly over a 1 mm of length, the variation over the molecules is small, but in the granular materials, if the number of particles in a 1 mm is low, a bigger variation is registered falling out of the continuum assumptions. The second length is related to the container confining the system and the third one to the inelasticity in grain-grain collisions. The latter can be defined as the radius of the pulse, related to a degradation of factor <math display="inline">e^-</math> of the total kinetic energy in a system of grains after a localized input of energy. If the inelasticity is not small this length covers just a few particles. This implies substantial changes in macroscopic quantities over distances measured over a small number of grain diameters, which do not allow to respect the continuum assumptions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | When one wants to study the flow of granular materials has to bear in mind that the bulk in motion is represented by an assembly of discrete solid particles interacting with each other. Depending on the intrinsic properties of the grains and the macroscopic characteristic of the system (i.e. geometry, density, velocity gradient), the internal forces can be transmitted in different ways within the granular material. Depending on this, three main flow patterns can be observed experimentally and numerically <span id='citeF-11'></span>[[#cite-11|[11]]]. At large solids concentration and low shear rate, the stresses are not evenly distributed, but are concentrated along networks of particles, called ''force chains''. The force chains are dynamic structures, which rotate, become unstable and, finally, collapse as a result of the shear motion. When granular material fails it is observed that the failure occurs along narrow planes, within the material, which have not infinitesimal thickness, but are zones of the order of ten particles across called ''shear bands''. Within the shear bands, the stresses <math display="inline">\boldsymbol{\tau }</math> are still distributed along the force chains and the shear <math display="inline"> \tau _{xy} </math> and normal stresses <math display="inline"> \tau _{yy} </math> are related in non-cohesive material as | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span id="eq-1.1"></span> | ||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | |

| − | | | + | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" |

| − | | | + | |- |

| + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\frac{\tau _{xy}}{\tau _{yy}} = \mathrm{tan}\phi </math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (1.1) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | where <math display="inline">\phi </math> is the internal friction angle. Observing Equation [[#eq-1.1|1.1]], it is noted that <math display="inline">\mathrm{tan}\phi </math> depends on the geometry of the force chains; thus, the friction-like response of the bulk is a result of the internal structure of force chains, as well. | |

| − | + | This flow pattern takes the name of ''Quasi-static regime'' because the rate of formation of the force chain divided by their lifetime is independent on the shear rate <math display="inline">\dot{\boldsymbol{\gamma }}</math> and with this also the generated stresses. If on one hand, the shear rate does not affect the response of the system, on the other hand, it is worth highlighting that the inter-particle stiffness ''k'' plays an important role, as the stresses within the force chains show a linear dependence with ''k''. The inter-particle stiffness, in turn, can be expressed as a linear function of the Young modulus ''E'' of the material and also depends on the local radius of curvature, thus, on the geometry of the contact. Bathurst and Rothenburg <span id='citeF-12'></span>[[#cite-12|[12]]] have derived an expression for the bulk elastic modulus ''K'', which linearly depends on the stiffness and can be used in the definition of the sound speed in a static granular material. As shown in the data of Goddard <span id='citeF-13'></span>[[#cite-13|[13]]] and Duffy <math display="inline">\& </math> Mindlin <span id='citeF-14'></span>[[#cite-14|[14]]], the wave velocity is dependent on the pressure applied to the bulk assembly. Thus, increasing the confining pressure, the elastic bulk modulus increases along with the inter-particle stiffness ''k'' and the ''force chains'' lifetime. | |

| − | The | + | Until the shear rates <math display="inline">\dot{\boldsymbol{\gamma }}</math> are kept low, the inertia effects are small and force chains are the only mechanism available to balance the applied load. Increasing the shear rate, the particles are still locked in force chains, but the forces generated have to take into account the inertia introduced in the system. Further increasing <math display="inline">\dot{\boldsymbol{\gamma }}</math>, the inertial component of the internal forces linearly increases with the shear rate and when these are comparable with the static forces the flow transition to the ''Inertial regime'' takes place. The ''Inertial regime'' encompasses flows where force chains cannot form and the momentum is transported largely by particle inertia. In this regime, the shear stresses are independent of the stiffness, but dependent on the second power of the shear rate, as expressed in the Bagnold scaling <math display="inline">\tau _{xy}/\rho d^2\dot{\boldsymbol{\gamma }}^2</math> <span id='citeF-15'></span>[[#cite-15|[15]]], where <math display="inline">d</math> and <math display="inline">\rho </math> are the particle diameter and particle density, respectively. Even if force chains are not present, multiple simultaneous contacts between the particles still coexist allowing longer contact period <math display="inline">t_c</math>. By defining with <math display="inline">T_{bc}</math> the binary contact time, i.e., the duration of a contact between two freely colliding particles, the ratio <math display="inline">t_c/T_{bc} > 1</math>. If this ratio has the value of 1, the dominant particle collisions are binary and instantaneous and the flow is defined with the name of ''Rapid Granular Flow'' <span id='citeF-16'></span>[[#cite-16|[16]]], which can be considered as an asymptotic case of the ''Inertial Regime''. This flow path is controlled by the property of granular temperature, which represents a measure of the unsteady components of velocity. The granular temperature is generated by the shear work and it drives the transport rate in two principal modes of internal (momentum) transport: a collisional and a streaming mode. In the first case, the granular temperature provides the relative velocity that drives particle to collide; while, in the second case, it generates a random velocity that makes the particles move relatively to the velocity gradient. In the ''Rapid Granular Flow'' the coexistence of contact and streaming stresses can be observed; obviously, the collisional mode dominates at high concentrations, while the streaming mode at low concentrations. It is generally assumed that, at small shear rates, a flow behaves quasi-statically, and that by increasing the shear rate, one will eventually end up in the ''Rapid Flow regime''. As pointed out by Campbell <span id='citeF-11'></span>[[#cite-11|[11]]], the transition through the regimes is regulated by the volume fraction and the shear rate. However, by fixing the first or the second field, the transition may take place in a different way. |

| − | + | ==1.2 Granular flow modelling== | |

| − | + | Despite the prevalence of granular materials in most of the industrial applications, there is still a large discrepancy between results predicted by analytical or numerical solutions and their real behaviour <span id='citeF-17'></span>[[#cite-17|[17]]]. Thus, structures and facilities for dealing with particulate material handling are not functioning efficiently and there is always a probability of structural failure and an unexpected arrest of the production line. Due to the intrinsic nature of granular materials, the prediction of their dynamic behaviour represents nowadays an important challenge for two main reasons. Firstly, the characteristic grain size has an excessively wide span: from nanoscale powders (such as colloids with a typical size of nanometre) to large blocks of coal extracted from mines. This feature gives rise to some difficulties in defining a unique model able to properly work across many scales. Secondly, although these materials are solid in nature, they behave differently in various circumstances and often changes in a new state of matter with properties of solids, liquids and gases <span id='citeF-17'></span>[[#cite-17|[17]]]. Indeed, as with solids, they can withstand deformation and form heap; as with liquids, they can flow; as with gases, they can exhibit compressibility. This second aspect makes the modelling of granular matter even more difficult to define, as the macroscopic behaviour is affected by a set of microscopic parameters which often are not directly measurable from laboratory tests. Nevertheless, these challenges encouraged the research community to work actively in the particle technology field, developing and improving several numerical and experimental techniques for the characterization of granular materials. | |

| − | + | As explained in Section [[#1.1 The granular flows|1.1]], a granular flow can undergo three main regimes in different domains of volume fraction and shear rate. When the grains have very little kinetic energy, the assembly of the particle is dense, and if the structure is dominated by the force chains the response of the bulk is independent on the shear rate. In this case, the flow pattern is known as ''Quasi-static regime'' and the behaviour is well described by classical models used in soil mechanics <span id='citeF-18'></span>[[#cite-18|[18]]]. On the other hand, if a lot of energy is brought to the grains, the system is dilute, granular materials are collisional, inertia-dominated and compressible similar to a gas. In this case, the stresses vary as the square of the shear rate <math display="inline">\dot{\boldsymbol{\gamma }}</math> <span id='citeF-15'></span>[[#cite-15|[15]]] and the flow falls under the ''Rapid granular flow'' theory. The principal approach, provided in the literature, for modelling granular flow under these conditions is represented by the Kinetic Theory of granular gases <span id='citeF-16'></span>[[#cite-16|[16]]]. In the definition of such a model, the formalism of gas kinetic theory is used with the constraint to consider the particles perfectly rigid and the kinetic theory formalism leads to a set of Navier-Stokes equations. Between these two regimes, we can find the dense and slow flow regime, characterized by the presence of multiple particles contact, but also by the absence of force chains. For the modelling of granular flows under this regime, in <span id='citeF-19'></span>[[#cite-19|[19]]] the constitutive relation of a viscoplastic fluid is proposed, commonly known with the name of <math display="inline">\mu (I)</math> rheology. The idea comes from the analogy observed with Bingham fluids, characterized by a yield criterion and a complex dependence on the shear rate. By assuming the particles perfectly rigid and a homogeneous and steady flow, a set of Navier-Stokes equations is provided. Despite it has been demonstrated that the model can successfully reproduce the results of some experimental tests <span id='citeF-19'></span>[[#cite-19|[19]]], the model can only qualitatively predict the basic features of granular flows. In fact, some phenomena, such as, the formation of shear bands, flow intermittence and hysteresis in the transition solid to fluid and vice-versa, cannot be modelled through the <math display="inline">\mu (I)</math> law. | |

| − | + | Even if there are models able to predict the flow behaviour in single regimes, a comprehensive rheology, able to gather together all three regimes, is still missing in the literature. Many attempts have been done during the last years. To cite a few of them, it is worth mentioning the contribution of Vescovi and Luding <span id='citeF-20'></span>[[#cite-20|[20]]] where a homogeneous steady shear flow of soft frictionless particles is investigated; both fluid and solid regimes are considered and merged into a continuous and differentiable phenomenological constitutive relation, with a focus on the volume fraction close to the jamming value. Also Chialvo and coworkers <span id='citeF-21'></span>[[#cite-21|[21]]] turn the attention to the interface between the quasi-static and the inertial regime in the context of a jamming transition, still neglecting any time dependency (under the assumption of steady-state flow), but considering soft friction particles. Other proposals are based on the relaxation of some hypotheses at the base of the <math display="inline">\mu (I)</math> rheology, such as, for instance, the constitutive laws provided by Kamrin et al. <span id='citeF-22'></span>[[#cite-22|[22]]] where the non-local effects are considered and by Singh et al. <span id='citeF-23'></span>[[#cite-23|[23]]] where the particle stiffness influence is included in the model. | |

| − | In | + | In order to perform a numerical investigation of the granular flow problem, one has to keep in mind that not only a constitutive model is needed for its accomplishment, but also a numerical technique used to solve the system of algebraic equations which govern the problem. Numerical methods can be distinguished according to the kinematic description adopted and to the spatial and time scales that balance laws are based on. As previously observed, particulate materials can be studied at different scales and depending on this the selection of the numerical technique may change. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Granular materials have a discrete nature and it is of paramount importance to have a clear description at the microscale for a deep understanding of the physics behind the bulk behaviour. In recent decades, the most common and used numerical tool for such investigation is represented by the Discrete Element Method (DEM) <span id='citeF-24'></span>[[#cite-24|[24]]], which considers a finite number of discrete interacting particles, whose displacement is described by the Newton's equations related to translational and rotational motions. | |

| − | + | In the research community, granular materials are studied by using a continuum approach, as well. For instance, all the aforementioned constitutive models, proposed under the condition which range between the ''Quasi-static regime'' and ''Rapid granular flow'', are based on a continuous description of the granular matter behaviour. On one hand these approaches, obviously, do not allow to predict the material response on the point, where two particles collide, i.e., at the microscale, but are able to provide a mesoscale response, constant on a representative elemental volume (REV), where the continuum assumptions are still valid <span id='citeF-10'></span>[[#cite-10|[10]]]. | |

| − | + | Other methods, available in the literature, are used to scale-up from the micro-level. In this regard, it is worth mentioning the Population Balance Method (PBM) <span id='citeF-25'></span>[[#cite-25|[25]]], able to describe the evolution of a population of particles from the analysis of single particle in local conditions. For instance, PBM is widely used to track the change of particle size distribution during processes where agglomeration or breakage of particles are involved, by using information, such as, impact velocity distribution, provided by DEM analysis <span id='citeF-26'></span><span id='citeF-27'></span>[[#cite-26|[26,27]]]. | |

| − | + | ==1.3 Objectives== | |

| − | = | + | In the present work, we focus on the macroscale analysis of granular flows. More specifically, the current monograph aims at providing a verified and validated numerical model able to predict the behaviour of highly deforming bulk of granular materials in their real scale systems. Some examples, objects of this study, are represented by hopper flows, the collapse of granular columns and measurement of bearing capacity of a soil undergoing the movement of a rigid strip footing. These tests are characterized by some common features which are essential for the definition of the numerical tool to be developed. All the examples of granular flow mentioned above are densely packed with solid concentrations well above 50% of the volume and they can be considered dense granular flow where forces are largely generated by inter-particle contacts. This implies that a collisional state of the matter, where the principal mechanism of momentum transport is based on binary particle contacts, will never be reached. Moreover, in all cases an elastic/quasi-static regime usually coexists with a plastic/flowing regime. In order to be able to model the quasi-static and the flowing behaviours simultaneously in different parts of the material domain, a constitutive law which accounts for both the elastic and plastic regime is needed. The use of viscous fluid materials, as those described by the <math display="inline">\mu (I)</math> rheology and its different versions, can predict the granular flow behaviour under the inertial regime. However, the good reliability of these models is still limited to the steady case and to volume fractions whose values never exceed the jamming point. Further, if a viscous material is chosen, some difficulties might be encountered in the evaluation of internal forces where a zero strain rate is present. With the picture described above, the numerical model is conceived in a continuum mechanics framework in order to optimize the high, not to say prohibitive, computational cost which might be induced by the high value of density in the grain system, if a discrete technique is, then, selected. Moreover, the transition between the solid-like and fluid-like behaviour induces large displacement and huge deformation of the continuum which, from the numerical viewpoint, is well established to be tough to handle with standard techniques, such as the well-known Finite Element Method (FEM). Last but not least, not only geometric, but also material non-linearities should be considered. To address to this concern, the choice falls on those elasto-plastic laws, defined within the solid mechanics framework, whose stress response depends on the total strain history and historical parameters characteristic of the material model. The numerical model to adopt has to be based not only on a continuum mechanics framework, but also has to be able to track with high accuracy the huge deformation of the medium and the spatial and time evolution of its own material properties. After a search focused on the numerical model which closest fits with the features outlined above, it is found that the Material Point Method (MPM) <span id='citeF-28'></span>[[#cite-28|[28]]], a continuum-based particle method, might be a good candidate in solving granular flows problems under multi-regime conditions and an optimal platform for the numerical implementation of new constitutive laws which attempt to include a bridge between different scales (from the particle-particle contact (micro) to the bulk (macro) scale). In the current work, an implicit MPM is developed by the author in the multi-disciplinary Finite Element codes framework ''Kratos Multiphysics'' <span id='citeF-29'></span><span id='citeF-30'></span><span id='citeF-31'></span>[[#cite-29|[29,30,31]]]. Unlike most MPM codes, which make use of explicit time integration, in this monograph it is decided to adopt an implicit integration scheme. The choice is made with the aim of analysing cases characterized by a low-frequency motion and providing results with a higher stability and better convergence properties. Two formulations are implemented within the MPM framework by taking into account the geometric non-linearity, which allows to treat problems of finite deformation, usually not considered in many MPM codes that one can find in the literature. Firstly, an irreducible formulation and a Mohr-Coulomb constitutive law are developed. Further, a mixed formulation is proposed for the analysis of granular flows under undrained conditions, which represents, to the knowledge of the author, an original solution in the context of the MPM technique. The MPM strategy, with both the formulations, is validated by using experimental results or solutions of other studies, available in the literature. Last but not least, as final objective of this monograph, the developed MPM numerical tool is successfully tested in an industrial framework, in the context of a collaboration with Nestlé. A comparison is performed against an unpublished experimental study conducted for the characterization of flowability of several types of sucrose. Advantages and limitations of the numerical strategy provided are observed and discussed. |

| − | + | ==1.4 T-MAPPP project== | |

| − | The | + | The current work has been funded by the T-MAPPP (Training in Multiscale Analysis of MultiPhase Particulate Processes and Systems, FP7 PEOPLE 2013 ITN-G.A. n60) project. This project has been conceived in order to bring together European organizations leading in their respective fields of production, handling and use of particulate systems. T-MAPPP is an Initial Training Network funded by FP7 Marie Curie Actions with 10 full partners and 6 associate partners. The role of the network is to train the next generation of researchers who can support and develop the emerging inter- and supra-disciplinary community of Multiscale Analysis (MA) of multi Phase Particulate Processes. The goal is to develop skills to progress the field in both academia and industry, by devising new multiscale technologies, improving existing designs and optimising dry, wet, or multiphase operating conditions. One aim of the project is to train researchers who can transform multiscale analysis and modelling from an exciting scientific tool into a widely adopted industrial method; in other words, the establishment of an avenue able to increasingly link academic to real world challenges. |

| − | + | ==1.5 Layout of the monograph== | |

| − | + | The layout of the document is as follows: in '''Chapter 2''', after a brief review of the state of the art in particle methods, the focus is put on those methods which are more consistently used for the prediction of granular flows behaviour, such as, the Discrete Element Method (DEM), the Particle Finite Element Method (PFEM), the Galerkin Meshless Methods (GMM) and the Material Point Method (MPM). The latter is the chosen approach, used and developed in this monograph. The choice is discussed and the details of the proposed formulations are provided. In '''Chapter 3''' the theory of constitutive laws used in the current work is presented with their implementations under the assumption of finite strains. In '''Chapter 4''' and '''Chapter 5''' an irreducible and a mixed stabilized formulation, respectively, are presented and verified with solid mechanics benchmark examples. Then, in '''Chapter 6''' the numerical model of MPM, presented in the previous chapters, is applied and validated (with experimental and numerical results available in the literature) against granular flow examples, such as, the granular column collapse and the rigid strip footing test. In '''Chapter 7''' the MPM strategy is applied in an industrial framework. The numerical results are compared against experimental measurements performed for the assessment of the flowability performance of different types of sucrose. Finally, in '''Chapter 8''' some conclusions are drawn, where observations and limitations of the numerical strategy are provided, and the bases for future research are outlined. | |

| − | + | =2 Particle Methods= | |

| − | + | Computer modelling and simulation are now an indispensable tool for resolving a multitude of scientific and challenging problems in science and engineering. During the last decades the importance of computer-based science has exponentially grown in the engineering field and, nowadays, it is widely adopted in the study of different processes because of its advantages of ''low cost'', ''safety'' and ''efficiency'' over the experimental modelling. The numerical simulation of solid mechanics problems involving history-dependent materials and large deformations has historically represented one of the most important topics in computational mechanics. Depending on the way deformation and motion are described, existing spatial discretisation methods can be classified into Lagrangian, Eulerian and hybrid ones. Both Lagrangian and Eulerian methods have been widely used to tackle different examples characterized by extreme deformations. In this chapter, firstly, the most common numerical techniques used in the modelling of granular flows are presented. Then, the focus is put on the Material Point Method, which is the object of the present study. | |

| − | + | ==2.1 Lagrangian and Eulerian approaches== | |

| − | + | In continuum mechanics two fundamental descriptions of the kinematic and the material properties of the body, under analysis, are possible. The first one is represented by the Lagrangian approach. In this case the description is made as ''the observer'' were attached to a material point forming part of the continuum. Lagrangian algorithms, traditionally employed in structural mechanics, make use of a moving deforming mesh dependent on the motion of the body and are distinguished by the ease with which the material interfaces can be tracked and the boundary conditions can be imposed. According to <span id='citeF-32'></span>[[#cite-32|[32]]] three Lagrangian formulations can be defined: | |

| − | + | * the ''Total Lagrangian'' formulation, where all the variables are written with reference to the undeformed configuration <math display="inline">\Omega ^0</math> at the initial time <math display="inline">t_0</math> | |

| + | * the ''Updated Lagrangian'' formulation, where all the variables are written with reference to the deformed configuration <math display="inline">\varphi \left(\Omega \right)^n</math> at the previous time <math display="inline">t_n</math> | ||

| + | * the ''Updated Lagrangian'' formulation, where all the variables are written with reference to the deformed configuration <math display="inline">\varphi \left(\Omega \right)^{n+1}</math> at the current time <math display="inline">t_{n+1}</math> | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | Moreover, history-dependent constitutive laws can be readily implemented and, since there is not advection between the grid and the material, no advection term appears in the governing equations. In this regard, Lagrangian methods are more simple and more efficient than Eulerian methods. The greatest drawback of this approach is represented by the high distortion of the mesh and element entanglement when the material undergoes really large deformation, which makes more difficult to obtain a stable solution with an explicit integration scheme. The second approach lies on an Eulerian description, i.e., ''the observer'' is located at a fixed spatial point. Thus, Eulerian techniques, mostly employed in fluid mechanics, are characterized by the use of a fixed grid and no mesh distortion or element entanglement are observed neither in the case of very large deformation. On the other hand, due to its intrinsic nature, it is difficult to identify the material interfaces and the definition of history-dependent behaviour is computationally intensive if compared with Lagrangian methods. As can be seen, each of the two approaches has advantages and drawbacks; thus, depending on the problem to solve, one technique is preferable over the second one. |

| + | |||

| + | In the framework of granular flow modelling the Lagrangian viewpoint presents, in this context, a rather obliged choice, since the adoption of such a framework greatly simplifies the constitutive modelling and the tracking of the entire deformation process. In the case of mesh-based methods, the natural limitation of the Lagrangian approach is related to the deformation of the underlying discretisation, which tends to get tangled as the deformation increases. Massive remeshing procedures have proved to be capable of further extending the realm of applicability of Lagrangian approaches, effectively extending the limits of the approach well beyond its original boundaries. Nevertheless, while, on one hand, it is possible to alleviate the distortion of the mesh, on the other hand, additional numerical errors arise from the remeshing and the mapping of state variables from the old to the new mesh. In this regard, the Arbitrary Lagrangian–Eulerian method (ALE) <span id='citeF-32'></span>[[#cite-32|[32]]], a generalization of the two approaches described earlier, has been developed in the attempt to overcome the limitation of the Total Lagrangian (TL) and Updated Lagrangian (UL) techniques when severe mesh distortion occurs by making the mesh independent of the material, so that the mesh distortion can be minimized. However, for very large deformation severe computational errors are introduced by the distorted mesh. Furthermore, the convective transport effects can lead to spurious oscillations that need to be stabilized by artificial diffusion or by other stabilization techniques. Such disadvantages make the ALE methods less suitable than other techniques which can be found in the literature. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the current work, the Lagrangian framework is considered, but the focus is on the so-called ''particle methods'', a series of techniques which represent a natural choice for the solution of granular flow problems involving large displacement, large deformation and history-dependent materials. The next section introduces a brief state of the art of the most common particle methods with their distinguished features and fields of application. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==2.2 Particle methods. A review of the state of the art== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Particle methods are techniques which have in common the discretisation of the continuum by only a set of nodal points or particles. According to <span id='citeF-33'></span>[[#cite-33|[33]]], they can be classified based on two different criteria: physical principles or computational formulations. For those methods classified according to physical principles a further distinction is made if the model is deterministic or probabilistic; while according to the computational formulations, the particle methods can be distinguished in two subcategories, those serving as approximations of the strong forms of the governing partial differential equations (PDEs), and those serving as approximations of their weak forms. In Tables [[#table-2.1|2.1]] and [[#table-2.2|2.2]] the classification is graphically shown with a list of the main approaches which fall under each category. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="floating_tableSCP wikitable" style="text-align: left; margin: 1em auto;min-width:50%;" | ||

| + | |+ style="font-size: 75%;" |<span id='table-2.1'></span>Table. 2.1 Physical principles based particle methods. | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| + | | colspan='2' style="text-align: center;" | ''Physical principles'' | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | | colspan='1' style="text-align: center;" | Deterministic models | ||

| + | | colspan='1' style="text-align: center;" | Probabilistic models | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| + | | Discrete Element Method (DEM) | ||

| + | | Molecular Dynamics | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | Monte Carlo methods | |

| − | | | + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" |

| − | | | + | | |

| + | | Lattice Boltzmann Equation method | ||

| + | |||

|} | |} | ||

| − | | style="width: | + | |

| + | |||

| + | {| class="floating_tableSCP wikitable" style="text-align: left; margin: 1em auto;min-width:50%;" | ||

| + | |+ style="font-size: 75%;" |<span id='table-2.2'></span>Table. 2.2 Computational formulations based particle methods. | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| + | | colspan='2' style="text-align: center;" | ''Computational formulations'' | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| + | | colspan='1' style="text-align: center;" | Approximations of the strong form | ||

| + | | colspan='1' style="text-align: center;" | Approximations of the weak form | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| + | | Smooth Particle Hydrodynamics | ||

| + | | Meshfree Galerkin Method: | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| + | | Vortex Method | ||

| + | | - ''Diffusive Element Method'' | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| + | | Generalized finite Difference Method | ||

| + | | - ''Element Free Galerkin Method'' | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| + | | Finite Volume PIC | ||

| + | | - ''Reproducing Kernel Method'' | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | - ''h-p Cloud Method'' | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | - ''Partition of Unity Method'' | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | - ''Meshless Local Petrov-Galerkin Method'' | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | - ''Free Mesh Method'' | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | Mesh-based Galerkin Method | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | - ''Material Point Method'' | ||

| + | |-style="font-size: 85%;" | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | - ''Particle Finite Element Method'' | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | <span id=" | + | In the following sections, a bibliographic review of the most common and widely used particle methods in granular flow modelling is presented. The first method to be presented is the Discrete Element Method. Then, the Smooth Particle Hydrodynamics, the Meshfree Galerkin Method, the Particle Finite Element Method and the Particle Finite Element Method 2 are briefly introduced. For each of those advantages and disadvantages are discussed. Finally, the Material Point Method and a meshless variation of it and their algorithms are extensively described. |

| − | {| class=" | + | |

| + | ===2.2.1 The Discrete Element Method (DEM)=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The numerical approach which considers the problem domain as a conglomeration of independent units is known as Discrete Element Method (DEM), developed by Cundall and Strack in 1979 <span id='citeF-24'></span>[[#cite-24|[24]]]. DEM was initially used for studying of rock mechanics problems using deformable polygonal-shaped blocks. Later, it has been widely utilized to study geomechanics, powder technology and fluid mechanics problems. Each particle is identified separately having its own mass, velocity and contact properties and, during the calculation, it is possible to track the displacement of particles and evaluate the magnitude and direction of forces acting on them. The main distinction between DEM and continuum approaches is the assumption on material representation; in DEM every particles represents a physical entity, e.g., the single grains in the granular system, while in a continuum method particles take the place of material points, which have instead just a numerical purpose in the computation of the solution. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to <span id='citeF-24'></span>[[#cite-24|[24]]] the time step must be chosen in a way that disturbances from an individual particle cannot propagate further than their neighbours. Usually, in order to avoid significant instability in the granular system the time step should be smaller than a critical time step, called the Rayleigh time step. | ||

| + | |||

| + | DEM is a good example of numerical technique that treats the bulk solid as a system of distinct interacting bodies. Thus, with DEM it is possible to simulate interaction at the particle level (at a spatial scale which ranges from <math display="inline">10^{-6}m</math> to <math display="inline">10^{-1}m</math>, depending on the size of the grains) and, at the same time, to obtain an insight into overall response, bulk properties such as stresses and mean velocities <span id='citeF-34'></span>[[#cite-34|[34]]]. Therefore, it can provide a clear explanation on particle-scale behaviour of granular solids to characterize bulk mechanical responses, as it is done in several contributions <span id='citeF-35'></span><span id='citeF-5'></span>[[#cite-35|[35,5]]]. Moreover, this technique is really useful and interesting in the research field of granular matter since DEM can be seen as a tool for performing numerical experiments that allow contact-less measurements of microscopic quantities that are usually impossible to quantify using physical experiments. Discrete element modelling has been also used extensively to analyse various handling and processing systems that deals with multiple bulk solids <span id='citeF-36'></span><span id='citeF-37'></span><span id='citeF-38'></span>[[#cite-36|[36,37,38]]]. However, the extremely high computational cost, proportional to the number of particles, leads to the limitation of considering relatively small system sizes and idealized geometries. | ||

| + | |||

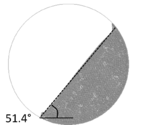

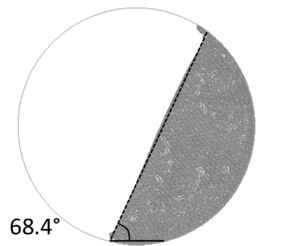

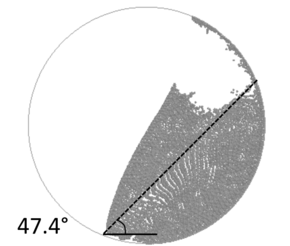

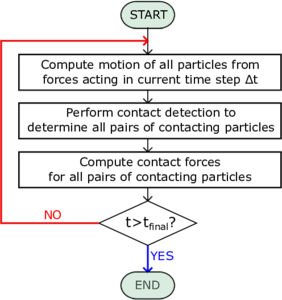

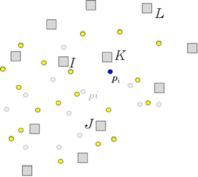

| + | The schematic flowchart, which has to be followed in order to execute a DEM calculation <span id='citeF-39'></span>[[#cite-39|[39]]] at each time step, is displayed in Figure [[#img-2.1a|2.1a]]. Even if the algorithm looks to be straightforward to run and easy to implement, the computational cost is proportional to the number of discrete elements and to their shapes. Thus, simplified assumptions have been made in the mathematical models in order to reduce the computational efforts. The primary idealized factor in DEM simulations is the shape of particles which is considered as spheres to simplify the contact detection process, which is the most time consuming step in DEM simulations. Among diverse physical properties of individual particles in particulate materials, the shape and morphology play important roles in shear strength and flowability of the bulk. In order to improve this aspect several approaches have been utilized in DEM, such as, clumped spheres <span id='citeF-40'></span>[[#cite-40|[40]]], polyhedral shapes <span id='citeF-41'></span>[[#cite-41|[41]]], super-quadric function <span id='citeF-42'></span>[[#cite-42|[42]]]. However, in order to obtain accurate results the computational cost may arise significantly. Another important step in DEM is to realistically simulate the physical impact between particles. This is usually approximated by defining spring and dashpots between contacting surfaces, as it is done in the linear-spring dash-pot models <span id='citeF-43'></span>[[#cite-43|[43]]] or the Hertzian visco-elastic models. In the literature other contact models can be found, such as meso-scale models <span id='citeF-35'></span><span id='citeF-44'></span><span id='citeF-45'></span>[[#cite-35|[35,44,45]]] or realistic contact models <span id='citeF-46'></span><span id='citeF-47'></span><span id='citeF-48'></span>[[#cite-46|[46,47,48]]], which can provide a high accuracy both at the particle and bulk level, but valid only for the limited class of materials they are particularly designed for. | ||

| + | |||

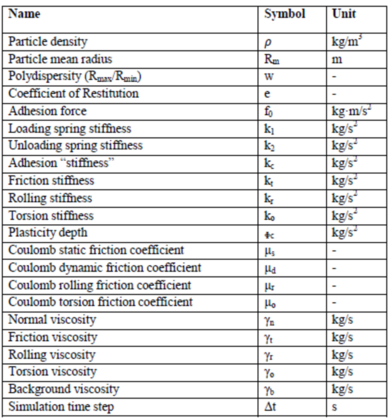

| + | Moreover, for a proper understanding of a process and to study realistic behaviour through DEM simulations, the input parameters, listed in Figure [[#img-2.1b|2.1b]], play a vital role. The input parameters are often assumed without careful assessment or calibration which often leads to unrealistic behaviours and erroneous results. Designing of equipment or of a process route with an un-calibrated DEM model may lead to serious handling and processing operations such as segregations, unexpected wear, irregular density of products, flow blockages and etc. Thus, a correct definition of the input parameters by experimental characterization and/or calibration, using particle-level tests, directly affect the reliability of the final response at the bulk level. However, this might result in an extremely time and cost consuming procedure, that not always it is possible to perform for a lack of time and/or money. | ||