Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

The incredible force with which ITCs have arrived in society and the consequent risks to children when dealing with the Internet and social networks make it necessary for the domain of virtual environments to be included in the school curriculum. However, the initiatives in this direction are limited and there is a lack of rigorously evaluated programs that might act as a basis for designing educational lines of action. The ConRed Program is based on the theory of normative social behavior and aims to reduce problems such as cyber-bullying and addiction to the Internet and refocus the misadjusted perception of information control in the social networks in order to promote their use in a more beneficial way. The ConRed Program has been evaluated using a quasi-experimental methodology, with an experimental group (N=595) and a quasi-control group (N=298) consisting of 893 students (45.9% girls) with an average age of 13.80 years (SD=1.47). The reduction of problems in the experimental group and the lack of change in the control group is evidence of the program’s validity, and show that by working and collaborating with the whole educational community it is possible to improve the quality of the virtual and, therefore, the real life of adolescents.

1. Introduction

1.1. Internet and social networks: a new social environment

The increasing use of information and communications technologies (ICTs) in everyday life has brought about considerable changes in many areas. One such area is that of interpersonal relationships, which are now no longer exclusively direct but also indirect and conducted by means of digital devices. We now live in what Azuma (1997) calls «augmented reality»: our activities tend to combine physical reality with virtual elements capable of supporting and improving them. Internet, and in particular social networks, plays a major role in this augmented reality, especially among young people, a group which uses these resources to an increasingly greater extent. Latest figures in Spain show that 55% of regular Internet users access social networks, rising to 84% among young people aged between 10 and 18 (Garmendia, Garitaonandia, Martínez & Casado, 2011), an age group in which nine out of 10 boys and girls have a social network profile.

Social networks represent the most important facet of Internet’s social dimension. They are essentially web services that are used for regular communication and sharing information, in which users make up an online community where they can interact with other people who share some or all of their interests (Boyd & Ellison, 2007). The key to the potential of social networks as a unique, attractive environment for interpersonal relationships lies in this element of self-selection. It has been claimed, perhaps with some exaggeration that the social situation of a person who lacks friends or contacts in a social network differs from that of a person with real friends and online contacts (Christakis & Fowler, 2010). Life is now lived in both physical and virtual environments. In terms of cultivating interpersonal relationships these virtual environments offer new opportunities, creating what Azuma (1997) calls «augmented reality» in which the interdependence of the physical and virtual worlds is taken for granted and the differences between the two are passed over. Virtual resources offer several social advantages: they make it easier to establish interpersonal relationships, they contribute to diversity in the types of social relationships cultivated, they facilitate ubiquity and they increase the amount of information available in real time (Winocur, 2006). But these advantages can become disadvantages if they are used incorrectly. Belonging to a social network means making decisions about our own intimacy (Liu, 2007), and those decisions are not always made consciously or sensibly (Stuzman, 2006). In other words, virtual life involves certain identity-related issues that people need to learn to deal with (Reig & Fretes, 2011).

1.2. Risks posed by Internet and social networks

The use of Internet and social networks involves certain risks which are particularly serious among children and young people (Dinev & Hart, 2004; Echeburúa & Corral, 2009; 2010; Graner, Beranuy-Fargues, Sánchez-Carbonell, Chamarro & Castellana, 2007; Ortega, Calmaestra & Mora-Merchán, 2008). They include: a) loss of control over personal information accessible on Internet; b) addiction to this type of technology and the consequent absence or decline of activities or relationships necessary for healthy development; and c) cyber-harassment, as an indirect form of the age-old problem of school bullying.

Lack of control over information can be exploited by others to ridicule, intimidate or blackmail (Dinev & Hart, 2004; Dinev, Xu & Smith, 2009). The information uploaded by a person, or by others, constitutes the basis for the virtual identity that is being created for that person. Although it may not affect the person’s everyday life (Turkle, 1997), manipulation of that information by others or lack of control over it by the person in question may place that person in a position of vulnerability by removing their intimacy (Nosko, Wood & Molema, 2010) thereby damaging their social relationships. One example of this is «sexting» (McLaughlin, 2010; Stone, 2011), a practice which is becoming increasingly widespread among Spanish teenagers (Agustina, 2010) and which involves posting half-naked pictures in virtual environments. This is inevitably harmful for minors, who believe that their conduct in those virtual environments is in no way connected to their real lives (Menjívar, 2010).

Internet activity can create addiction. Boys and girls who spend a lot of time in front of a computer screen, neglecting their duties and their own leisure time and basing their relationships with others on technological interaction, may begin to show signs of unease when they are not using a computer or a cell phone. ICTs abuse is a risk which may negatively affect quality of life for teenagers in a hyper-technological world, reducing their freedom and possibly creating addiction (Echeburúa & Corral, 2009; 2010).

Cyberbullying is another risk posed by the virtual world for teenagers and young people. For bullies this virtual environment offers a space less invigilated by adults and by the authorities (Tejerina & Flores, 2008). Cyber-harassment can be divided into two main types: «grooming» and «cyberbullying». Grooming, also known as «child-grooming» in legal parlance, refers to the procedure by which an adult establishes a relationship with a minor in order to achieve some kind of sexual satisfaction (Monge, 2010). Cyberbullying is defined as aggressive intentional acts carried out by a group or individual, using electronic forms of contact, repeatedly and over time against a victim who cannot easily defend him or herself (Smith, Mahdavi, Carvalho & Tippett 2006). Many researchers consider it an indirect form of traditional bullying (Ortega & Mora Merchán, 2008; Smith & al., 2006), characterized by a series of specific features which include: a) the channels of communication are always open, and aggression can therefore take place at any time and in any place; b) attacks can be witnessed an indefinite number of times by large numbers of spectators and c) victims may never know who their attackers are because the channels used allow a high degree of anonymity.

These risks have increased because it is precisely teenagers and young people who have become computer literate much faster and to a much broader extent than the adult population, thus giving rise to what is known as the digital gap (Piscitelli, 2006, Marín and González-Piñal, 2011). Significantly, 80% of young Spaniards say they learned to use Internet without the help of an adult (Bringué & Sádaba 2011).

1.3. School: a key area for encouraging cyber-socialization

Schools play a crucial role in developing children’s technology skills (OECD, 2005). Such skills should not be seen merely as familiarity with tools and devices, but should be addressed jointly with other capabilities, such as those of citizenship and personal autonomy (Ricoy, Sevillano & Feliz, 2011). In the new skills-based approach to syllabus design, the functional, healthy mastery of ICTs constitutes a basic building block for the development of personal autonomy, learning-to-learn skills and a cosmopolitan sense of citizenship (Ortega, Del Rey & Sánchez, 2011). The need to take action and help the whole education community is also a priority issue in new psychosocial models based on scientific evidence (Del Rey & Ortega, 2011). Schools should be seen as learning communities in which interaction between the players involved can be analyzed in terms of their mutual support as complementary elements within the task of educating. Schools are places of convivencia (harmonious interaction) and development in which young people should play a major role as learners: in the field of digital literacy, they are often ahead of their own responsible adults. This may upset the teaching-learning pattern and make it necessary to rethink conventional approaches. Teenagers and young people, considered digital natives (Prensky, 2001), may be quicker and more efficient in the use of digital devices but they nevertheless need support and supervision in the psychosocial processes which take place when socializing is conducted via digital activity. The generation gap mentioned above needs to be narrowed so that it can be the corresponding adults –teachers and families– who educate minors in the new facet of life represented by Internet.

But the same thing has happened here as so often happens in education. The need to take action has arisen before the scientific community and, above all, the public authorities, have the information necessary to be able to establish suitable procedures. Although in Spain a series of good practices do exist with this objective in mind (Luengo Latorre, 2011; Del Rey & al., 2010; Mercadal, 2009, and others), no empirically proven practices, procedures or evidence –based programs are yet available (Navarro, Giribet & Aguinaga, 1999; Sackett, Richardson, Rosenberg & Haynes, 1997). Nevertheless, any decision regarding a plan of action to be implemented at school should ideally first be corroborated scientifically (Davies, 1999; Granero, Doménech, Bonillo & Ezpeleta, 2001; Hunsley & Johnston, 2000; Lindqvist & Skipworth, 2000; Stoiber & Kratochwill, 2001). Scientific research is therefore necessary to determine whether a given program or procedure is effective, by analyzing the significant changes brought about by a program and comparing the outcome to what would have happened if that program had not been implemented.

ConRed (Discover, Construct and Live in Harmony on Internet and in Social Networks), the action program presented here, is designed to encourage the correct use of Internet and Social Networks. It was developed in line with the tenets of «Evidence Based Practice» (EBP), taking into account scientific evidence presented in different research papers describing programs which successfully molded or modified behavior in cases where technology was being used incorrectly or as a vehicle for inappropriate conduct (Borsari & Carey, 2003; Haines & Spear, 1996; Wechsler & Kuo, 2000).

1.4. The ConRed program

The ConRed program adheres to the tenets of the «theory of normative social behavior» (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005; Rimal & Real, 2005; Rimal, Lapinski, Cook & Real, 2005), which argues that human behavior is heavily influenced by perceived social norms and their interpretation as an indication of social consensus. In other words, a close relationship is identified between the behavior and actions of the majority and what that majority perceives as being socially acceptable, normal or legally justifiable. In some action programs based on this theory and aimed at addressing teen problems such as alcohol consumption, links have been found between the belief that consuming alcohol is good for establishing social relationships or belonging to a peer group and increased alcohol consumption (Borsari & Carey, 2003).

According to the theory of normative social behavior, beliefs can be measured in terms of the three aspects which constitute what are known as normative mechanisms Rimal & Real, 2003): a) injunctive norms; b) expectations and c) group identity. Injunctive norms are rules subject to sanctions or social punishment. In the case of action taken to reduce alcohol abuse, for example, laws exist which penalize drunken driving and there is a clear social rejection of people guilty of this type of conduct. Expectations are what each individual, depending on his/her beliefs, hopes to gain from engaging in a given type of conduct (Bandura, 1977; 1986). Going back to the example of alcohol consumption, evidence that drinking alcohol reduces behavioral inhibitions reinforces the belief that alcohol will aid social communication. Finally, group identity refers to the motivational urge to belong to social groups sharing the same collective sense of identity, and the belief that conduct or attitudes shared with other members of the group are legitimate and justifiable insofar that they reinforce that group identity. To modify or change a given type of conduct, a program based on this theory must therefore have an impact on these three aspects, and this was the approach adopted when designing the ConRed action plan.

The program’s three key overall objectives are: 1) to show the legal implications and the damage that can be caused through bad conduct in virtual environments; 2) to highlight specific actions which are closely linked to Internet’s risks but very far removed from Internet’s benefits and 3) to reveal how certain forms of conduct do not reflect specific social groups or make a person more acceptable as a member of such groups. Taking these three considerations as a point of departure, the ConRed program is designed to aid and sensitize the education community in the safe, positive, beneficial use of Internet and social networks.

To attain these goals, the following specific objectives were established: a) to stress the importance of familiarity with safety and personal information protection mechanisms on Internet and in social networks, to avoid the bad use of the same; b) to learn to use Internet safely and healthily, fully aware of its potential benefits; c) to find out how widespread cyber-harassment and other risks are in secondary education; d) to prevent involvement in acts of aggression, harassment, denigration, etc., either as victims or perpetrators, in social networks; e) to help and encourage an attitude of resilience in people affected by violent or harmful conduct on Internet; f) to find out how users perceive the degree of control they exert over the information they share on social networks and e) to prevent ICTs abuse and show the consequences of technology addiction.

The ConRed action program was aimed at the whole education community: training sessions were held with teachers and the families of schoolchildren, with the schoolchildren themselves forming the principal target group.

The work done with each group revolved around three areas: a) Internet and social networks; b) benefits of Internet use and instrumental skills and c) risks and advice on usage.

The sequence followed, both for the training and the measures implemented, started with a brainstorming session to explore the children’s/teachers’/ parents’ prior knowledge about technology use, functions and Internet. Content was then introduced to look at the opportunities offered by social networks. Particular attention was paid to the importance of privacy and identity and the negative consequences of not having them. The themes of pro-social behavior and solidarity in social networking were examined, with special attention to the main risks posed by social networks and the consequences of using them inappropriately. Last but not least, the main strategies for dealing with social networking problems were described, together with the most important tips on how to use ICTs properly.

Taking school as a place of social interaction and convivencia, ConRed launched an awareness-raising campaign using materials like leaflets, posters, stickers, bookmarks, etc. to keep the initiative going over a period of time.

The starting hypothesis was that the implementation of the ConRed program would alleviate and reduce problems such as cyberbullying, Internet addiction and erroneous perceptions regarding the degree of control exerted over information in social networks.

2. Materials and methods

The program was evaluated with a quasi-experimental, ex post facto, longitudinal design, with pre- and post- measurements, covering two groups, one of which was a quasi-control group (Montero & León 2007). The target population comprised adolescents between the ages of 11 and 19. The program was carried out directly in the classroom.

• The sample group. The sample group was made up of 893 students –595 in the experimental group and 298 in the control group – from 3 secondary schools in the city of Cordoba, Spain. 45.9% of the group were girls, and the students’ ages ranged from 11 to 19 years (M=13.80; DT=1.47).

• Instruments. Three instruments were used, relating to cyberbullying, the addictive use of Internet and perceived control over information. They were: the European Cyberbullying Questionnaire (Del Rey, Casas & Ortega, 2011), comprising 24 Likert items with five frequency options ranging from never to several times a week and with adequate internal consistency: a total=0.87, a victimization=0.80 and a aggression=0.88; a version of the CERI (Internet-related Experiences Questionnaire) adapted by Beranuy, Chamarro, Graner and Carbonell-Sánchez (2009) and comprising 10 Likert items with four options (not at all, little, somewhat and a lot), with acceptable internal consistency: a total =0.781, a intrapersonal= 0.719 and a interpersonal=0.631; and the Perceived Information Control scale (Dinev, Xu & Smith 2009), a 4-item Likert-type scale with seven answer options reflecting the degree of agreement (from not at all to very much) and a good level of internal consistency: a=0.896.

• Procedure. The ConRed program was implemented over a period of 3 months during the 2010/11 school year, with schools timetabling and providing facilities for several work sessions. Two groups were created: the measures prescribed in the program were adopted in one of them (the experimental group) and not in the other (the control group). Data was collected on two occasions: once before program implementation (pre-measurements) and once after (post-measurements).

• Analysis. Data was analyzed using SPSS statistical software, Version 18.0, in Spanish. The mean factors obtained were compared using a Student’s T-test to compare the significance of the difference in the mean scores obtained for individuals in the experimental and control groups on the two occasions when measurements were taken.

3. Results

Possible differences between the experimental and control groups prior to the implementation of the ConRed program were first analyzed using a Student’s T-test for independent samples. No significant starting differences were found in the variables: cyberbullying (t=-1.421; p>0.05), cyberbullying aggression (t=-1.858; p>0.05), cyberbullying victimization (t=0.567; p>0.05), addiction to Internet (t=0.560; p>0.05), interpersonal addiction (t=0.527; p>0.05), intrapersonal addiction (t=0.323; p>0.05) and control over information (t=1.754; p>0.05).

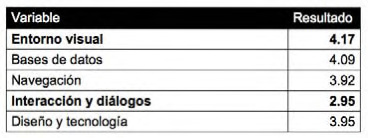

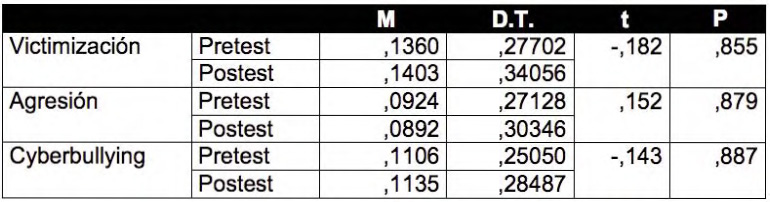

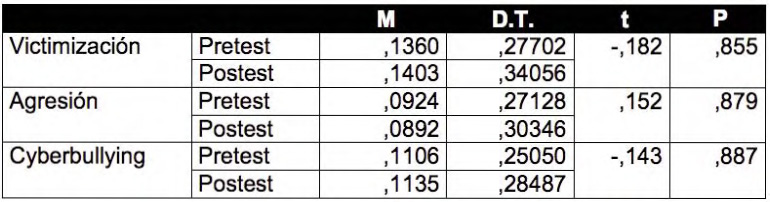

Differences between the experimental and control groups and between pre-test and post-test measurements were then analyzed using a Student’s T-test for related samples. With regard to cyberbullying, no differences were found in the control group between pre-test and post-test values: Cyberbullying (t=-0.143; p>0.05), Cyberbullying aggression (t=0.152; p>0.05), Cyberbullying victimization (t =-0.182; p>0.05) (see table 1).

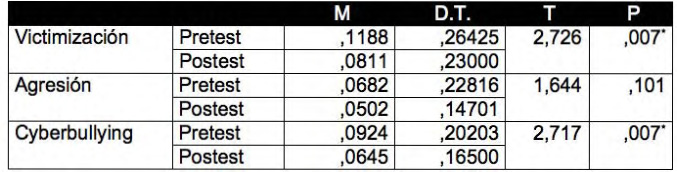

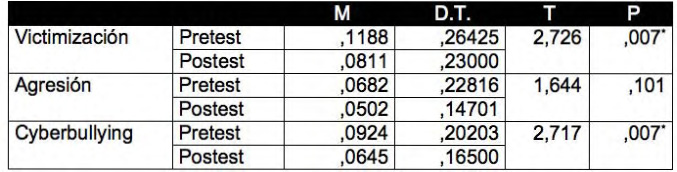

Differences were, however, found in the experimental group: Cyberbullying (t=-2.726; p>0.05*), Cyberbullying aggression (t=1.644; p>0.05), Cyberbullying victimization (t =-2.726; p> 0.05*). Here, values were lower after program implementation (see table 2).

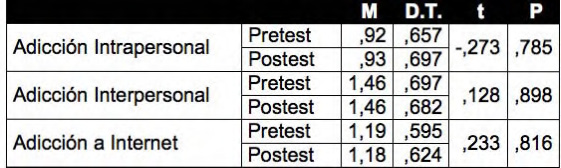

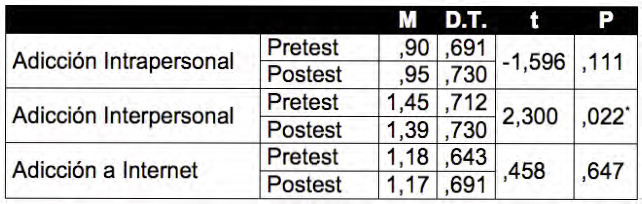

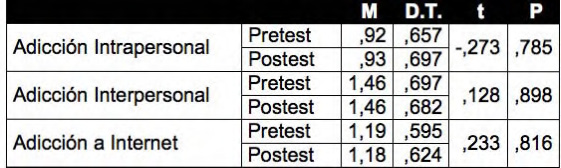

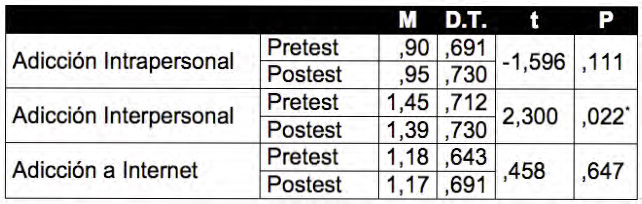

Likewise, in the control group no significant differences were found between the pre-test and post-test values with regard to the abusive use of/addiction to Internet (see Table 3): Addiction to Internet (t=0.233; p>0.05), Interpersonal addiction (t=0.128; p>0.05), Intrapersonal addiction (t=-0.273; p>0.05). But differences were found in the experimental group: Addiction to Internet (t=.458; p>0.05), Interpersonal addiction (t=2.300; p<0.05*), Intrapersonal addiction (t=-1.596; p>0.05) (see Table 4).

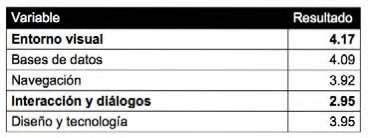

Finally, with regard to perceived control over information, the results for the control group were similar (t=-0.692; p>0.05) whereas analysis of the results for the experimental group revealed significant differences between pre-test and post-test measurements (t=3.762; p< 0.01*) (see Table 5).

4. Discussion

The ConRed program produced positive results with regard to the three main objectives proposed: a) to reduce students’ involvement in cases of cyberbullying; b) to reduce the excessive use of Internet and the risk of addiction; and c) to alter students’ perception of the amount of control they had over personal information uploaded to social networks. The results obtained reflected significant changes in the impact of these three proposed training objectives. The experimental group obtained better results after the program’s implementation than the control group, in which some types of conduct and attitudes (for example, perceived control over information) even increased. This would seem to support the starting hypothesis that implementation of the ConRed program would lead to a decrease in certain undesirable forms of adolescent behavior.

Among the students who took part directly in the ConRed program there was a general decrease in involvement in cyberbullying, in the abusive use of Internet and in the false perception of control over information; this latter result suggests a greater awareness of the students’ own lack of information about how to control their own data, their subsequent vulnerability and the usefulness of learning and using strategies to augment their control and keep the personal information they upload to Internet private.

Previous scientific literature contains no consolidated groundwork regarding the implementation of action programs to combat cyberbullying in schools, although work has been done on traditional school bullying and specific programs have been proposed to prevent harassment and violence among schoolchildren. Such programs have produced positive results, demonstrating that sustained, controlled, whole policy action can improve interpersonal harmony and prevent school violence and bullying. One example is the SAVE project (Seville Anti School Violence), an action approach based on scientific evidence (Ortega, 1997; Ortega & Del Rey, 2001). ConRed adopted the same parameters (working with students, teachers and families to improve knowledge and raise awareness about how information can be controlled) and produced comparable results (Ttofi & Farrington, 2009). We believe that cyber-harassment is an indirect form of traditional bullying –i.e., indirect bullying (Smith & al., 2008)– ; and that whole policy preventive models are therefore still valid. This is fully coherent with the importance now being attached to the school as the place where this type of problem can best be dealt with (Luengo Latorre, 2011). The results of this study support the idea that whole policy measures are an effective means of reducing high risk behavior. We have shown how by raising risk awareness and training teachers and parents to guide young people’s behavior it is possible to reduce high risk conduct, increase the taking of precautionary measures and induce protective attitudes in online activity, without creating undue alarm among schoolchildren. From our point of view this is one of the key results because help given to victims, and their awareness that they have someone there to help them and advise them, reinforces their confidence and dispels the sense of weakness and isolation which prevents them from facing up to these kinds of problems (Hunter & Boyle, 2004).

ConRed itself illustrates the need to curb the potentially excessive use of Internet and to reduce the risk of addiction to online activity by raising students’ capacity to deal with the online challenges they may face. It should be remembered that addiction is one of the great risks to development during adolescence (Echeburúa & Corral, 2009; 2010). However, addiction to Internet is best addressed through action on a very personal level, more comparable to that which might be taken by a clinical psychologist (Griffiths, 2005). Studies into the importance of the interpersonal aspect of addiction have shown that it is necessary to educate students in Internet use and encourage healthy attitudes and conduct in online activity (Machargo, Lujan, León, López & Martín, 2003).

The pretest showed that young people generally have very little idea about the business dimension of the online platforms to which they belong. ConRed demonstrated how a specific educational program can effectively contribute to redressing this potentially dangerous lack of information about social network usage, and we feel this is one of the program’s most positive achievements. Our results reveal how important it is that risk prevention on Internet and in social networks should form part of the school syllabus: They also show that this training does not necessarily have to be carried out in a virtual environment. The action taken should be seen as part of the job of educating the young; part of the students’ learning process and just another subject teachers are required to impart as part of the syllabus. Teachers should receive ongoing training in this field, thereby narrowing the digital gap which separates them from their students and enabling them to provide help and guidance. In the same vein, families should know about their children’s online social environment in order to be able to help and support them. To conclude, ConRed has shown how, by working in collaboration with the whole education community, it is possible to improve the quality of adolescents’ lives, both virtual and real.

The ConRed program is the beginning of a series of evidence-based practices aimed at improving the society in which we live through education. Nevertheless, this study inevitably has certain limitations and further research yet needs to be carried out. For example, our data was collected from only three schools and the research team played a very active role in the action taken with the students. In the future, more schools should be included in the research and responsibility for the program should be passed on to each school’s teaching staff, providing them with the autonomy they should ideally enjoy when implementing programs of this type.

Despite its limitations, the study allows us to conclude that projects implemented today to encourage harmonious interpersonal relationships (convivencia) in schools should at least be supported by short term initiatives addressing social relationships in virtual environments. We know that by involving students, teachers and families it is possible to improve young people’s knowledge of and control over social networks, narrow the generation gap which exists between digital natives and immigrants and alleviate the problems associated with the inappropriate use of ICTs. And that is how cyberbullying, and especially cyber-victimization, can be reduced. In view of all this, at least four things should be taken into consideration by the education authorities: the vital importance of awareness-raising campaigns in the education community; the main line of action should be teacher training and the boosting of teachers’ confidence in their ability; this should ideally be articulated through the introduction of new education legislation; and financial support is needed to make it possible.

Support

This program was funded by the European Project: Cyberbullying in adolescence: investigation and intervention in six European Countries» (Code: JLS/2008/CFP1DAP12008-1; European Union, DAPHNE III Program) and by the University of Cordoba.

References

Agustina, J.R. (2010). ¿Menores infractores o víctimas de pornografía infantil? Respuestas legales e hipótesis criminológicas ante el Sexting. Revista Electrónica de Ciencia Penal y Criminología, 12, (11), 1-44.

Azuma, R. (1997). A Survey of Augmented Reality. Presence: Tele operators and Virtual Environments. 6, (4), 355-385.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliff, NJ. Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Englewood Cliff, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Beranuy, M., Chamarro, A., Graner C. & Sánchez-Carbonell, X. (2009). Validación de dos escalas breves para evaluar la adicción a Internet. Psicothema 3, 480-485.

Borsari, B. & Carey, K.B. (2003). Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64, 331-341.

Boyd, D.M. & Ellison, N.B. (2007). Social Network Sites: De fi nition, History, and Scholarship. Journal of Computer-Media ted Com munication, 13 (1), 210-230.

Bringué, X. & Sádaba, C. (2011). Menores y redes sociales. Ma drid: Colección Foro Generaciones Interactivas/Fundación-Tele fónica. (www.generacionesinteractivas.org/?page_id=1678).

Christakis, N. & Fowler, J. (2010). Conectados. Madrid: Tau rus.

Davies, P. (1999). What is Evidence-based Education? British Journal of Educational Studies, 47, 108-121.

Del Rey, R. & Ortega, R. (2011). An Educative Program to Cope with Cyberbullying in Spain: CONRED. In Conference Evidence-based Prevention of Bullying and Youth Violence: European Inno va tion and eEperience. Cambridge, UK, 5-6 July 2011.

Del Rey, R., Casas, J.A. & Ortega, R. (under review). Spanish Validation of the European Cyberbullying Questionnaire from Daphne Project.

Del Rey, R., Flores, J., Garmendia, M. & al. (2010). Protocolo de actuación escolar ante el cyberbullying. Bilbao: Gobierno Vasco.

Dinev T. & Hart, P. (2004). Internet Privacy Concerns and Their Antecedents, Measurement Validity and a Regression Model. Beha viour & Information Technology 23 (6), 413-422.

Dinev, T., Xu, H. & Smith, H.J. (2009). Information Privacy and Correlates: An Attempt to Navigate in the Misty Conceptual Wa ters. Proceedings of 69th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Ma na gement (AOM 2009). Chicago: Illinois.

Echeburúa, E. & Corral, P. (2009). Las adicciones con o sin droga: una patología de la libertad. In E. Echeburúa, F.J. Labrador & E. Becoña (Eds.). Adicción a las nuevas tecnologías en adolescentes y jóvenes (pp. 29-44). Madrid: Pirámide.

Echeburúa, E. & Corral, P. (2010). Adicción a las nuevas tecnologías y a las redes sociales en jóvenes: un nuevo reto. Adicciones, 22 (2), 91-96.

Garmendia, M., Garitaonandia, C., Martínez, G. & Casado, M.A. (2011). Riesgos y seguridad en internet: Los menores españoles en el contexto europeo. Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal He rriko Unibertsitatea, Bilbao: EU Kids Online.

Graner, P., Beranuy-Fargues, M., Sánchez-Carbonell, C. & al. (2007). ¿Qué uso hacen los jóvenes y adolescentes de Internet y del móvil? In L. Álvarez-Pousa & J. E. Pim (Eds.), Congreso Comunicación e Xuventude: Actas do Foro Internacional, 71-90.

Granero, R., Doménech, J.M., Bonillo, A. & Ezpeleta, L. (2001). Psicología basada en la evidencia: Un nuevo enfoque para me jorar la toma de decisiones. Madrid: VII Congreso de Metodología de las Ciencias Sociales y de la Salud.

Griffiths, M.D. (2005). Internet Abuse in the Workplace, Issues and Concerns for Employers and Employment Counselors. Journal of Employment Counseling, 40, 87-96.

Haines, M. & Spear, S.F. (1996). Changing the Perception of the Norm: A Strategy to Decrease Binge Drinking Among College Students. Journal of American College Health, 45, 134-140.

Hunsley, J. & Johnston, C. (2000). The Role of Empirically Supported Treatments in Evidence-Based Psychological Practice: A Canadian Perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 7, 269-272.

Hunter, S. & Boyle, J. (2004). Appraisal and Coping Strategy Use in Victims of School Bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 83-107.

Lapinski, M.K. & Rimal, R.N. (2005). An Explication of Social Norm. Communication Theory, 5 (2), 127-147

Lindqvist, P. & Skipworth, J. (2000). Evidence-Based Reha bi li tation in Forensic Psychiatry. British Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 320-323.

Liu, H. (2007) Social Network Profiles as Taste Performances. Jour nal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13 (1), 252-275.

Luengo-Latorre, J.A. (2011). Cyberbullying, guía de recursos para centros educativos. La intervención en los centros educativos: Materiales para equipos directivos y acción tutorial. Madrid: De fensor del Menor.

Machargo, J., Luján, I., León, M.E., López, P. & Martín, M.A. (2003). Videojuegos por los adolescentes. Anuario de Filosofía, Psicología y Sociología, 6, 159-172.

Marín, I. & González-Piñal, R. (2011). Relaciones sociales en la sociedad de la Información. Prisma Social, 6, 119-137.

McLaughlin, J.H. (2010). Crime and Punishment: Teen Sexting in Context. (http://works.bepress.com/julia_mclaughlin) (02-02-2012).

Menjivar, M. (2010). El sexting y l@s nativ@s neo-tecnológic@s: Apuntes para una contextualización al inicio del siglo XXI. Actua lidades Investigativas en Educación, 10 (2), 1-23.

Mercadal, R. (2009). Pantallas amigas. Comunicación y Peda go gía, 239, 55-57.

Monge, A. (2010). De los abusos y agresiones sexuales a menores de trece años tras la reforma penal de 2010. Revista de Derecho y Ciencias Penales, 15, 85-103.

Montero, I. & León, O.G. (2007). Guía para nombrar los estudios de investigación en Psicología. International Journal of Clini cal and Health Psychology, 7, 847-862.

Navarro, F., Giribet, C. & Aguinaga, E. (1999). Psiquiatría basada en la evidencia: Ventajas y limitaciones. Psiquiatría Biológica, 6, 77-85.

Nosko, A., Wood, E. & Molema, S. (2010). All about Me: Dis clo sure in Online Social Networking profiles: The Case of Face book. Computers in Human Behavior. 26 (3), 406-418.

OECD (Ed.) (2005). Policy Coherence for Development. Pro moting Institutional Good Practice. The Development Dimension Series. Paris: OECD.

Ortega, R. & Del Rey, R. (2001). Aciertos y desaciertos del proyecto Sevilla Anti-violencia Escolar (SAVE). Revista de Educación. 324, 253-270.

Ortega, R. & Mora-Merchán, J.A. (2008). Las redes de iguales y el fenómeno del acoso escolar: explorando el esquema dominio-sumisión. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 31 (4), 515-528.

Ortega, R. (1997). El proyecto Sevilla Anti-violencia Escolar. Un modelo de intervención preventiva contra los malos tratos entre iguales. Revista de Educación, 313, 143-158.

Ortega, R., Calmaestra, J. & Mora-Merchán, J. (2008). Cy ber bullying. International Journal of Psychology and Psycho lo gical Therapy, 8(2), 183-192.

Ortega, R., Del Rey, R. & Sánchez, V. (2011). Nuevas dimensiones de la convivencia escolar y juvenil. Ciberconducta y relaciones en la Red: Ciberconvivencia. Madrid: Observatorio Estatal de la Convivencia Escolar. Informe interno.

Piscitelli, A. (2006). Nativos e inmigrantes digitales, ¿Brecha generacional, brecha cognitiva, o las dos juntas y más aún? Revista Me xi cana de Investigación Educativa, 11 (28), 179-185.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon, 9, 1-6.

Reig, D. & Fretes, G. (2011). Identidades digitales: límites poco claros. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, 418, 58-59.

Ricoy, M.C., Sevillano, M.L. & Feliz, T. (2011). Competencias necesarias para la utilización de las principales herramientas de Internet en la educación. Revista de Educación, 356, 483-507.

Rimal, R., Lapinski, M., Cook, R. & Real, K. (2005). Moving Toward a Theory of Normative In?uences: How Perceived Bene?ts and Similarity Moderate the Impact of Descriptive Norms on Behaviors. Journal of Health Communication, 10, 433-50.

Rimal, R.N. & Real, K. (2003). Understanding the Influence of Perceived Norms on Behaviors. Communication Theory, 13, 184-203.

Rimal, R.N. & Real, K. (2005). How Behaviors are Influenced by Perceived Norms: A Test of the Theory of Normative Social Be havior. Communication Research, 32, 389-414.

Sackett, D.L., Richardson, W.S., Rosenberg, W. & Haynes, R.B. (1997). Medicina basada en la evidencia: Cómo ejercer y enseñar la MBE. Churchill Livingston.

Smith, P.K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, C. & Tippett, N. (2006). An Investigation into Cyberbullying, its Forms, Awareness and Impact, and the Relationship between Age and Gender in Cy ber bullying. Research Brief RBX03-06. London: DfES. (www.antibullyingalliance.org.uk/downloads/pdf/cyberbullyingreportfinal230106_000.pdf) (10-06-2007).

Smith, P.K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S. & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: its Nature and Impact in Se condary School Pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psy chiatry, 49, 376-385.

Stoiber, K.C. & Kratochwill, T.R. (2001). Evidence-based Inter vention Programs: Rethinking, Refining, and Renaming the New Standing Section of School Psychology Quarterly. School Psy chology Quarterly, 16, 1-8.

Stone, N. (2011). The ‘Sexting’ Quagmire: Criminal Justice Res ponses to Adolescents’ Electronic Transmission of Indecent Images in the UK and the USA. Youth Justice, 11, 3, 266-281.

Stutzman, F. (2006). An Evaluation of Identity-sharing Behavior in Social Network Communities. Journal of the International Digital Media and Arts Association, 3 (1), 10-18.

Tejerina, O. & Flores, J. (2008). E-legales. Bilbao: Edex.

Ttofi, M.M. & Farrington, D.P. (2009). School-based Programs to Reduce Bullying and Victimization. Campbell Systematic Re views. Oslo: Campbell Collaboration.

Turkle, S. (1997). La vida en la pantalla. Barcelona: Paidós

Wechsler, H. & Kuo, M. (2000). College Students Define Binge Drinking and Estimate its Prevalence: Results of a National Survey. Journal of American College Health, 49, 57-64.

Winocur, R. (2006). Internet en la vida cotidiana de los jóvenes. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 68 (3), 551-580.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

La vertiginosa incorporación de las TIC a la sociedad y los consecuentes riesgos a los que los menores se enfrentan en Internet y las redes sociales han dejado en evidencia la necesidad de incorporar en el currículum escolar el dominio de los entornos virtuales. En cambio, son escasas las iniciativas en esta dirección y más aún programas rigurosamente evaluados, de modo que sirvan de fundamento para el diseño de las líneas de acción educativa. El programa ConRed está basado en la teoría del comportamiento social normativo y persigue los objetivos de mejorar y reducir problemas como el cyberbullying, la dependencia a Internet y la desajustada percepción del control de la información en las redes sociales, para así potenciar el uso beneficioso de éstas. La evaluación del ConRed se ha desarrollado mediante una metodología cuasi experimental, con un grupo experimental (N=595) y uno cuasi-control (N=298). Del total de los 893 estudiantes, el 45,9% eran chicas y la edad media 13,80 años (DT=1,47). Los resultados positivos de reducción de problemas en el grupo experimental y la ausencia de cambio en el grupo control son muestra de su validez y demuestran que trabajando con toda la comunidad educativa y en colaboración con ella es posible mejorar la calidad de la vida virtual y, por tanto, real de los adolescentes.

1. Introducción

1.1. Internet y redes sociales: nuevo contexto de socialización

Las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC) se han incorporado a nuestras vidas potenciando cambios sustanciales en múltiples aspectos entre los que destacan las relaciones interpersonales que ahora, además de directas, resultan ser indirectas y mediadas por los dispositivos digitales. Hoy vivimos en lo que Azuma (1997) denomina «realidad aumentada», ya que las actividades que realizamos tienden a combinar realidad física con elementos virtuales, mejorando y apoyando así dichas actividades. Realidad aumentada en la que Internet, y especialmente las redes sociales, tienen un especial protagonismo, particularmente entre los jóvenes donde su uso no deja de aumentar. Las últimas cifras de las que se dispone señalan que, en España, hay un 55% de usuarios habituales de Internet, cifra que se eleva al 84% en edades comprendidas entre los diez y dieciocho años (Garmendia, Garitaonandia, Martínez & Casado, 2011). Grupo de edad en el que además nueve de cada diez chicos y chicas poseen un perfil en una red social.

Las redes sociales son el máximo exponente de la dimensión social de Internet y se caracterizan como servicios web utilizados para comunicarse o compartir información regularmente en las que los usuarios forman una comunidad online donde pueden interactuar con otras personas sobre la base de una serie de intereses comunes (Boyd & Ellison, 2007). Es la auto-elección lo que proporciona a las redes sociales su potencialidad de ser un contexto singular y atractivo de relaciones interpersonales. Se ha asegurado, quizás de forma algo exagerada, que la socialización de una persona que carece de amistades o contactos en la red social difiere de otra que cuenta con amigos reales y contactos en su red social (Christakis & Fowler, 2010). La vida se desarrolla tanto en contextos físicos como virtuales que están dotando de nuevas oportunidades a las relaciones interpersonales que se desarrollan ahora, utilizando la aportación de Azuma (1997), en una «sociedad aumentada» en la que en lugar de apostar por la divergencia entre ambos entornos, se asume su interdependencia. La convivencia se está enriqueciendo de las ventajas de los recursos virtuales como la mayor apertura en el establecimiento de relaciones interpersonales, la diversidad en las relaciones sociales, la ubicuidad, la disponibilidad de información al instante, etc. (Winocur, 2006). Ventajas que pueden transformarse en desventajas si se hace un uso inadecuado de ellas. Pertenecer a una red social supone ir tomando decisiones sobre nuestra propia intimidad (Liu, 2007). Opciones que no siempre se eligen de forma consciente y consecuente (Stuzman, 2006). Es decir, la vida virtual tiene ciertas peculiaridades relativas a la identidad que conviene aprender a gestionar (Reig & Fretes, 2011).

1.2. Riesgos de Internet y las redes sociales

Internet y el uso de redes sociales conlleva ciertos riesgos que se amplifican para la población juvenil (Dinev & Hart, 2004; Echeburúa & Corral, 2009; 2010; Graner, Beranuy-Fargues, Sánchez-Carbonell, Chamarro & Castellana, 2007; Ortega, Calmaestra & Mora-Merchán, 2008). Destacaremos entre otros: a) la pérdida de control de la información personal en la Red; b) la dependencia de estas tecnologías y la consiguiente carencia o deterioro en actividades y relaciones necesarias para el desarrollo y c) el ciberacoso, como forma indirecta del viejo problema interpersonal del acoso escolar.

La ausencia de control sobre la información puede ser aprovechada por otros para ponerlo en evidencia, coaccionarlo o chantajearle (Dinev & Hart, 2004; Dinev, Xu & Smith, 2009). La información que uno mismo u otros publican en red es la que soporta la propia identidad virtual que se va construyendo y que, aunque en ocasiones puede no afectar a la vida diaria (Turkle, 1997), puede situar al individuo en situación de indefensión por la pérdida de intimidad (Nosko, Wood & Molema, 2010) y por el consecuente deterioro de sus relaciones sociales si esa información es manipulada por otros o descontrolada por el propio individuo. Un ejemplo es el llamado «sexting» (McLaughlin, 2010; Stone, 2011), práctica cada vez más extendida entre los adolescentes españoles (Agustina, 2010) y que consiste en difundir en entornos virtuales imágenes semidesnudas con el daño que ello puede suponer a los menores, quienes creen que sus actividades en los entornos virtuales no pertenecen a su vida real (Menjívar, 2010).

La actividad en Internet puede llegar a crear hábitos de adicción. Chicos y chicas que pasan mucho tiempo frente a la pantalla, dejando de lado sus obligaciones y tiempo de ocio, que empiezan a mostrar síntomas de malestar cuando no están frente al ordenador o el móvil y que basan sus relaciones con los demás en una interrelación tecnológica. El abuso de las TIC es un riesgo que puede paliar la calidad de vida de los adolescentes en un mundo hipertecnológico, restando libertad y quizás generando dependencia (Echeburúa & Corral, 2009; 2010).

El ciberacoso es otro de los riesgos del mundo virtual para los adolescentes y jóvenes ya que los acosadores han encontrado en este entorno menor control y supervisión de las autoridades y de la población adulta (Tejerina & Flores, 2008). Así, se pueden diferenciar dos grandes tipos de ciberacoso: el «grooming» y el «cyberbullying». El grooming o también denominado «child-grooming» en el ámbito jurídico hace referencia a las acciones de un adulto con intención de establecer relaciones con un menor para conseguir un disfrute sexual personal (Monge, 2010). El cyberbullying se define como una agresión intencional repetida en el tiempo usando formas electrónicas de contacto, por parte de un grupo o un individuo, a una víctima que no puede defenderse fácilmente por sí misma (Smith, Mahdavi, Carvalho & Tippett, 2006). Es considerado por muchos investigadores como una forma de bullying tradicional indirecto (Ortega & Mora Merchán, 2008; Smith & al., 2006) que presenta una serie de características propias tales como: a) la agresión puede suceder en cualquier momento y en cualquier lugar, ya que los canales de comunicación siempre están abiertos; b) la agresión puede ser observada por una gran cantidad de espectadores y espectadoras, un número indefinido de veces y c) las víctimas pueden no llegar nunca a conocer a sus agresores o agresoras debido al anonimato que permiten los medios que éstos utiliza.

Estos riesgos se ven acentuados dado que es la población adolescente y juvenil la que más rápida y ampliamente se ha digitalizado en sus hábitos frente a la población adulta, hablándose de la llamada brecha digital (Piscitelli, 2006; Marín & González-Piñal, 2011). Consecuencia de ello puede ser considerado el hecho de que el 80% de los jóvenes afirmen haber aprendido a usar Internet sin la ayuda de un adulto (Bringué y Sádaba, 2011).

1.3. La escuela: protagonista en la promoción de la cibersocialización

La institución educativa juega un papel esencial en la formación de los menores en materia de competencia tecnológica (OECD, 2005), competencia tecnológica que no debe ser entendida como mera instrumentalización, sino que debe desarrollarse conjuntamente a otras competencias como la ciudadana y la autonomía personal (Ricoy, Sevillano & Feliz, 2011). En la nueva orientación de desarrollo curricular articulada por competencias básicas, la competencia para la autonomía personal, la capacidad de aprender a aprender y la construcción de una mentalidad ciudadana y cosmopolita encuentra en el dominio operativo y saludable de las TIC su aliado básico (Ortega, Del Rey & Sánchez, 2011). Por otro lado, la necesidad de intervenir y ayudar a toda la comunidad educativa es una exigencia de los nuevos modelos psicosociales basados en la evidencia científica (Del Rey & Ortega, 2011). Los centros escolares han de visualizarse como comunidades de aprendizaje en las cuales la interacción de los protagonistas sea analizada en lo que tienen de mutuo apoyo al servicio de las tareas educativas. Los centros escolares son contextos de convivencia y desarrollo en los que los jóvenes deben tener un papel protagonista como aprendices y, en el caso de las metas de competencia digital, con frecuencia pueden ir por delante de sus propios adultos responsables. Esto puede producir una fractura en el esquema de enseñanza-aprendizaje ante la que hay que estar preparado para solventar. Los adolescentes y jóvenes, considerados nativos digitales (Prensky, 2001), pueden ser más rápidos y eficaces en el manejo de los dispositivos digitales, pero necesitan soporte y control en los procesos psicosociales que se activan en la socialización que se despliega a través de la actividad digital. Es necesario aminorar la brecha generacional mencionada para que sean los adultos relevantes, profesorado y familias, quienes eduquen a los menores en esta nueva faceta de la vida que es Internet.

En este ámbito ha sucedido como en muchas ocasiones acontece en educación. La necesidad de intervenir en esta materia ha surgido antes de que la comunidad científica y, en especial, las autoridades públicas dispusieran de claves fundamentales para establecer las líneas de acción. Así, existen algunas buenas prácticas en España para contribuir a este objetivo (Luengo Latorre, 2011; Del Rey & al., 2010; Mercadal, 2009, entre otros), pero no se dispone hasta el momento de unas prácticas empíricamente contrastadas, o programas basados en la evidencia (Navarro, Giribet & Aguinaga, 1999; Sackett, Richardson, Rosenberg & Haynes, 1997). Es decir, es necesario que cuando se decida una forma de intervenir en la escuela, ésta esté avalada por la evidencia científica (Davies, 1999; Granero, Doménech, Bonillo & Ezpeleta, 2001; Hunsley & Johnston, 2000; Lindqvist & Skipworth, 2000; Stoiber & Kratochwill, 2001). Por ello, es preciso que a través de la investigación científica se contraste si un determinado programa o forma de proceder es efectivo, analizando la existencia de cambios sustantivos al desarrollar el programa frente al hecho de no desarrollarlo.

El programa de intervención para el buen uso de Internet y las redes sociales denominado: ConRed, «Conocer, construir y convivir en Internet y las redes sociales», que aquí se presenta, se ha contextualizado dentro de las prácticas basadas en la evidencia «Evidence Based Practice» (EPB), teniendo en cuenta los testimonios científicos señalados en diferentes investigaciones que describen programas exitosos en su objetivo de educar o modificar la conducta en el mal uso de instrumentos o de acciones (Borsari & Carey, 2003; Haines & Spear, 1996; Wechsler & Kuo, 2000).

1.4. El programa ConRed

El programa ConRed se enmarca en la denominada teoría del comportamiento social normativo «theory of normative social behavior» (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005; Rimal & Real, 2005; Rimal, Lapinski, Cook & Real, 2005) que defiende que la conducta humana está fuertemente influenciada por las normas sociales que percibimos y que nos describen el consenso social a nuestro alrededor. Es decir, se reconoce que el comportamiento y las acciones de la mayoría de personas están fuertemente relacionados con lo que éstas perciben socialmente aceptado, como normal o legal. En el caso de algunos de los programas de intervención que se han desarrollado en base a esta teoría destinados a reducir problemas entre adolescentes, por ejemplo, el consumo de alcohol, se desvela que la creencia sobre que tomar alcohol es beneficioso para mejorar las relaciones sociales y para la pertenencia al grupo de iguales estaba relacionada con el mayor consumo de alcohol (Borsari & Carey, 2003).

Según la teoría del comportamiento social normativo, las creencias están mediadas por tres aspectos que componen los llamados mecanismos normativos (Rimal & Real, 2003): a) las normas legales reconocidas; b) las expectativas y c) la identidad de grupo. Las normas legales reconocidas «injunctive norms» son aquellas que conllevan sanciones o castigo social. Retomando el ejemplo de la intervención contra el abuso del alcohol, existen leyes que condenan actuaciones bajo el efecto de la embriaguez y existe un claro rechazo social hacia las personas que abusan de esta sustancia. Las expectativas se refieren a lo que cada persona, dependiendo de sus creencias, espera encontrar en términos de beneficios, de la realización de una conducta (Bandura, 1977; 1986). Volviendo al ejemplo del consumo de alcohol: la evidencia de que la ingestión alcohólica provoca una desinhibición de la conducta, refuerza la creencia de que el alcohol facilitará la comunicación social. Por último, la identidad de grupo se refiere a la fuerza motivacional que tiene la necesidad de formar parte de grupos sociales participando de una suerte de identidad colectiva o identidad de grupo. La creencia sobre que un comportamiento o actitud compartida con otros miembros del grupo justifica su actuación debido a que refuerza la identidad grupal y legitima dicho comportamiento. Por tanto, un programa basado en esta teoría implica que para modificar o cambiar un determinado tipo de comportamiento se ha de incidir en estos tres aspectos. El ConRed ha utilizado esta aproximación teórica en su diseño de intervención.

Consecuentemente, las tres claves que sustentan el programa ConRed son: 1) mostrar la legalidad y las acciones perjudiciales del mal comportamiento en entornos virtuales; 2) conocer la existencia de determinadas acciones muy ligadas a los riesgos de la Red y lejanas a sus beneficios y 3) exponer cómo ciertas conductas no reflejan a un grupo determinado, ni hacen que se produzca una mayor aceptación. A partir de dichas claves, el programa ConRed está diseñado para potenciar y sensibilizar a la comunidad educativa en un uso seguro, positivo y beneficioso de Internet y las redes sociales.

El ConRed ha establecido los siguientes objetivos específicos: a) mostrar la importancia de un buen conocimiento de los mecanismos de seguridad y protección de los datos personales en Internet y las redes sociales para que no exista un mal uso de ellos; b) aprender a realizar un uso seguro y saludable de la Red conociendo los beneficios que nos puede aportar; c) conocer la prevalencia del fenómeno del ciberacoso y otros riesgos en la educación secundaria; d) prevenir la implicación como víctimas o agresores del alumnado en acciones de agresión, acoso, difamación, etc. en las redes sociales; e) fomentar una actitud de afrontamiento y de ayuda hacia las personas involucradas en episodios violentos o nocivos en Internet; f) descubrir cuál es la percepción del control que poseen sobre la información que comparten en las redes sociales y e) prevenir el abuso de las TIC y mostrar las consecuencias de una dependencia tecnológica.

La población objeto de la intervención ConRed ha sido toda la comunidad educativa desarrollándose sesiones formativas con el profesorado y las familias de los escolares, siendo el grupo principal (target) los escolares.

El trabajo con los tres colectivos gira en torno a tres ámbitos: a) Internet y las redes sociales; b) beneficios de su uso y competencia instrumental y c) riesgos y consejos de utilización.

La secuencia formativa y de intervención comienza con la exploración de las ideas y conocimientos previos que los escolares/profesorado/padres poseen sobre manejo, funcionamiento y uso de Internet. Seguidamente, se abordan contenidos referidos a las oportunidades que nos ofrece la participación en redes sociales y a la privacidad y la identidad en las redes sociales, indagando en la importancia y consecuencias negativas que puede conllevar no poseerlas. Asimismo, se trabajan la prosocialidad y solidaridad en el uso de las redes sociales y se hace especial hincapié en los principales riesgos que albergan estas redes y las consecuencias de realizar un uso inadecuado. Por último, pero no menos importante, se muestran las principales estrategias de afrontamiento sobre problemas en estos medios y los principales consejos para el buen uso de las TIC.

Tomada la escuela como una comunidad de convivencia, el ConRed despliega una campaña de sensibilización con materiales como trípticos, pósteres, adhesivos, marcadores de páginas, etc. que apoyan la continuidad de las acciones.

La hipótesis de partida es que desarrollando el programa ConRed se puede mejorar y reducir problemas como el cyberbullying, la dependencia a Internet y una ajustada percepción sobre el control de la información en las redes sociales.

2. Material y métodos

El estudio se ha realizado mediante un diseño longitudinal, «ex post facto», cuasi experimental, pre-post de dos grupos, uno cuasi-control (Montero y León, 2007). La población objetivo son los adolescentes con edades comprendidas entre los 11 y los 19 años. Se ha desarrollado mediante una intervención directa en las aulas.

• Participantes. En el estudio han participado un total de 893 estudiantes, 595 en el grupo experimental y 298 en el grupo de control, procedentes de 3 centros de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria (ESO) de la ciudad de Córdoba. El 45,9% eran chicas y las edades de los sujetos estaban comprendidas entre 11 y 19 años (M=13,80; DT=1,47).

• Instrumentos. Se han utilizado tres instrumentos relativos a cyberbullying, uso adictivo de Internet y percepción del control de la información. Concretamente, el European Cyberbullying Questionnaire (Del Rey, Casas & Ortega, 2011) que consta de 24 ítems con escala Likert de cinco opciones en función de la frecuencia, desde no hasta varias veces a la semana cuya consistencia interna es adecuada: a total=0.87, a victimización=0.80 y a agresión=0.88. Una adaptación del Cuestionario de Experiencias relacionadas con Internet (CERI) de Beranuy, Chamarro, Graner y Carbonell-Sánchez (2009) que consta de 10 ítems de escala Likert con cuatro opciones de respuesta (nada, poco, algo y bastante) cuya consistencia interna también es aceptable: a total =0.781, a intrapersonal =,719 y a interpersonal=,631. Y la escala Perceived Information Control (Dinev, Xu & Smith, 2009) de 4 ítems tipo Likert de siete opciones de respuesta en el grado de acuerdo (desde nada hasta muy de acuerdo) de buen nivel de consistencia interna, a=0.896.

• Procedimiento. El proyecto ConRed se ha desarrollado durante el curso académico 2010/2011. Los centros cedieron su tiempo e instalaciones para que el proyecto fuera desarrollado en varias sesiones durante el periodo de tres meses. Se crearon dos grupos, uno que ha recibido la intervención (grupo experimental) y otro que no la ha recibido (grupo control). Han existido dos momentos de recogida de datos, los datos pre intervención y los post intervención.

• Análisis. El análisis de datos se ha realizado con el paquete estadístico SPSS versión 18.0 en español. Se ha realizado una comparativa de medias de los factores obtenidos mediante una prueba T de Student para comparar la significatividad de la diferencia de las medias de la puntuación obtenida por los sujetos de los grupos experimental y control en los dos momentos de la aplicación de los instrumentos.

3. Resultados

En primer lugar se analizaron las posibles diferencias entre los grupos experimental y control antes del desarrollo del programa ConRed mediante una T de Student para muestras independientes, no encontrando diferencias significativas de partida en las variables: cyberbullying (t=-1,421; p>0,05), agresión cyberbullying (t=-1,858; p>0,05), victimización cyberbullying (t=0,567; p>0,05), adicción a Internet (t=0,560; p> 0.05), adicción interpersonal (t=0,527; p>0.05), adicción intrapersonal (t=0,323; p>0.05) y control de la información (t=1,754; p>0.05).

Posteriormente, las diferencias entre los grupos control y experimental y entre pretest y postest se han analizado mediante una T de Student para muestras relacionadas. Así, respecto a Cyberbullying, en el grupo control no existen diferencias entre el pretest y el postest: Cyberbullying (t=-0,143; p>0,05), Agresión Cyberbullying (t=0,152; p>0,05), Victimización Cyberbullying (t =-0,182; p>0,05) (ver tabla 1).

En cambio, en el grupo experimental sí las hay: Cyberbullying (t= 2,726; p<0,05*), Agresión Cyberbullying (t=1,644; p>0,05), Victimización Cyberbullying (t=2,726; p<0,05*), encontrando un descenso tras la intervención (ver tabla 2).

Respecto al uso abusivo o adicción a Internet, tampoco existen diferencias significativas entre el pretest y el postest en el grupo control (ver tabla 3): Adicción a Internet (t=0,233; p>0.05), Adicción Interpersonal (t=0,128; p>0.05), Adicción Intrapersonal (t=-0,273; p>0.05). Y sí, en el grupo experimental: Adicción a Internet (t=,0458; p>0.05), Adicción Interpersonal (t=2,300; p<0.05*), Adicción Intrapersonal (t=-1,596; p>0.05) (ver tabla 4).

Finalmente, en cuanto al control percibido sobre la información, el grupo control se comporta del mismo modo (t=-0,692; p>0.05) y, en el grupo experimental, el análisis revela que sí existen diferencias sienificativas en la medida pretest y postest (t=3,762; p<0.01*) (ver tabla 5).

4. Discusión

La evaluación del programa ConRed arroja resultados positivos respecto a los principales objetivos que se proponía que eran: a) La reducción de la implicación en el fenómeno del cyberbullying; b) La disminución del uso excesivo o riesgo de adicción; c) El ajuste en la percepción sobre el control de la información personal vertida en las redes sociales. Afirmación sustentada en los resultados encontrados que muestran cambios significativos respecto del dominio de los tres objetivos formativos que el ConRed se propuso. El grupo experimental obtuvo mejores resultados tras la intervención que el grupo control, en el que incluso aumentaron ciertas conductas o acciones (como, por ejemplo, la percepción del control de la información), apoyando así la hipótesis de partida relativa a que el desarrollo del programa ConRed conllevaría descenso de ciertos comportamientos no deseables de los adolescentes.

Entre el alumnado que ha participado directamente en el programa ConRed, se observa un descenso de prevalencia general de implicación en cyberbullying y en la realización de un uso abusivo de Internet; así como un descenso en la percepción del falso control de la información; mostrando evidencias de una mayor concienciación de los vacíos de información relevante para el control y de la vulnerabilidad que ello significa, así como de la utilidad de dominar y ejercer estrategias para aumentar el control y lograr la privacidad de la información personal que se coloca en la Red.

La intervención en los centros educativos con respecto al fenómeno del cyberbullying no tiene antecedentes consolidados en la literatura científica, al contrario que sucede en el caso del acoso escolar o «bullying», donde se conocen programas específicos de prevención del acoso entre escolares y la violencia escolar y juvenil. Ejemplos como el proyecto Sevilla Antiviolencia Escolar (SAVE) que se realizó ya desde una perspectiva de intervención basada en la evidencia científica (Ortega, 1997; Ortega & Del Rey, 2001) y en el que se obtuvieron resultados positivos, pusieron de manifiesto que la intervención sostenida y controlada de carácter ecológico, mejora la convivencia y previene la violencia escolar y el bullying. El ConRed ha actuado bajo los mismos parámetros (trabajando con alumnado, profesorado y familias en la mejora del conocimiento y la conciencia de control sobre el mismo) siendo sus resultados homologables (Ttofi & Farrington, 2009). En nuestra opinión, el ciberacoso es una forma indirecta del bullying tradicional, un bullying indirecto (Smith & al., 2008); por lo que siguen siendo válidos los modelos ecológicos o de «whole policy» para su prevención. Ello es coherente con la atención que en esta materia se le está otorgando al centro como unidad de tratamiento (Luengo Latorre, 2011). Los resultados del presente estudio respaldan la idea de la eficacia de la intervención ecológica para la disminución de las conductas de riesgo. Hemos mostrado cómo, elevando la toma de conciencia sobre los riesgos, sin alarmar en demasía a los escolares y capacitando a los docentes y padres para que ejerzan su rol de orientadores de la conducta juvenil, disminuyen las conductas de riesgo y aumenta la toma de precauciones y actitudes de protección ante el mismo. Desde nuestra perspectiva, éste es un resultado clave, puesto que la ayuda a las víctimas, el conocimiento de asesoramiento y ayuda, refuerza el apoyo y reduce la sensación de debilidad o soledad que logra impedir a las víctimas afrontar estos episodios (Hunter & Boyle, 2004).

El ConRed pone asimismo evidencia de la necesidad de disminuir el posible uso excesivo de la actividad en Internet y el riesgo de dependencia de estas conductas, mediante el aumento de la autonomía del alumnado para afrontar los desafíos ante los que los chicos y chicas se pueden enfrentar. Recuérdese que la dependencia es uno de los grandes riesgos para el desarrollo de los adolescentes (Echeburúa & Corral, 2009; 2010). Sin embargo, no se debe obviar que la adicción o dependencia de Internet debe ser objeto de una intervención personalizada, más ligada a la psicología clínica (Griffiths, 2005). Los estudios que muestran la importancia del factor interpersonal en problemas de adicción nos indican la necesidad de trabajar educativamente el uso, las actitudes y el comportamiento cibernético (Machargo, Lujan, León, López & Martín, 2003).

Los jóvenes desconocen en gran medida el funcionamiento empresarial de las plataformas a las que pertenecen, tal y como se observó en el pre-test. El ConRed ha puesto de manifiesto que efectivamente un programa educativo específico permite la mejora de esa vulnerabilidad de la información juvenil en el uso de las redes sociales, lo que es considerado un logro positivo del programa. Estos resultados nos muestran la importancia que tiene la inclusión en el currículum escolar de la prevención de riesgos en Internet y las redes sociales y que no es imprescindible que ésta sea desarrollada en el entorno virtual. La intervención debe ser entendida como parte de la tarea educativa, es decir, como parte del aprendizaje del alumnado y de la enseñanza que el profesorado está obligado a impartir, abordando el currículum. Es necesario reciclar a los docentes en esta materia y reducir así la brecha que les separa de los jóvenes para ayudar y asesorar y, del mismo modo, las familias deben conocer el contexto en el que se desarrollan sus hijos e hijas para poder supervisar y mostrar su apoyo. En definitiva, el ConRed ha mostrado que trabajando con toda la comunidad educativa y en colaboración con ella es posible mejorar la calidad de la vida virtual y, por tanto, real de los adolescentes.

El programa ConRed es el comienzo de unas prácticas basadas en la evidencia destinadas a mejorar la sociedad en la que vivimos, desde la educación. Sin embargo, sigue siendo necesaria mayor investigación en esta materia, debido a que el presente estudio presenta ciertas limitaciones. Entre ellas, destacar que la evaluación se ha realizado en tres centros y que la intervención con el alumnado se ha realizado con un protagonismo del equipo de investigación. Sería necesario seguir avanzando incorporando a más centros educativos a la investigación y traspasando el protagonismo de la acción a los equipos docentes de forma que éstos sean, como deben ser, autónomos en la acción.

A pesar de dichas limitaciones, el presente trabajo nos permite concluir que hoy en día los proyectos de convivencia de los centros educativos deberían ser completados, al menos, con intervenciones a corto plazo dedicadas a las relaciones en los entornos virtuales. Sabemos que implicando a alumnado, profesorado y familias es posible mejorar el conocimiento y dominio de las redes sociales, estrechar la brecha generacional existente entre nativos e inmigrantes digitales y disminuir los problemas que de su mal uso se pueden derivar. De esta forma, descenderá el ciberbullying, particularmente la cibervictimización. Por todo ello, al menos cuatro consideraciones se deberían tener en cuenta desde las autoridades educativas: es primordial la sensibilización de la comunidad educativa, a través de campañas de sensibilización; el eje central de actuación debe ser la formación del profesorado y su sentimiento de competencia; es recomendable un desarrollo legislativo educativo que lo impulse y es necesario un apoyo financiero que lo posibilite.

Apoyos

Este programa ha sido subvencionado por el proyecto europeo «Cyberbullying in adolescence: investigation and intervention in six European countries» (Código: JLS/2008/CFP1DAP12008-1; Unión Europea, Programa DAPHNE III) y por la Universidad de Córdoba.

Referencias

Agustina, J.R. (2010). ¿Menores infractores o víctimas de pornografía infantil? Respuestas legales e hipótesis criminológicas ante el Sexting. Revista Electrónica de Ciencia Penal y Criminología, 12, (11), 1-44.

Azuma, R. (1997). A Survey of Augmented Reality. Presence: Tele operators and Virtual Environments. 6, (4), 355-385.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliff, NJ. Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Englewood Cliff, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Beranuy, M., Chamarro, A., Graner C. & Sánchez-Carbonell, X. (2009). Validación de dos escalas breves para evaluar la adicción a Internet. Psicothema 3, 480-485.

Borsari, B. & Carey, K.B. (2003). Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64, 331-341.

Boyd, D.M. & Ellison, N.B. (2007). Social Network Sites: De fi nition, History, and Scholarship. Journal of Computer-Media ted Com munication, 13 (1), 210-230.

Bringué, X. & Sádaba, C. (2011). Menores y redes sociales. Ma drid: Colección Foro Generaciones Interactivas/Fundación-Tele fónica. (www.generacionesinteractivas.org/?page_id=1678).

Christakis, N. & Fowler, J. (2010). Conectados. Madrid: Tau rus.

Davies, P. (1999). What is Evidence-based Education? British Journal of Educational Studies, 47, 108-121.

Del Rey, R. & Ortega, R. (2011). An Educative Program to Cope with Cyberbullying in Spain: CONRED. In Conference Evidence-based Prevention of Bullying and Youth Violence: European Inno va tion and eEperience. Cambridge, UK, 5-6 July 2011.

Del Rey, R., Casas, J.A. & Ortega, R. (under review). Spanish Validation of the European Cyberbullying Questionnaire from Daphne Project.

Del Rey, R., Flores, J., Garmendia, M. & al. (2010). Protocolo de actuación escolar ante el cyberbullying. Bilbao: Gobierno Vasco.

Dinev T. & Hart, P. (2004). Internet Privacy Concerns and Their Antecedents, Measurement Validity and a Regression Model. Beha viour & Information Technology 23 (6), 413-422.

Dinev, T., Xu, H. & Smith, H.J. (2009). Information Privacy and Correlates: An Attempt to Navigate in the Misty Conceptual Wa ters. Proceedings of 69th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Ma na gement (AOM 2009). Chicago: Illinois.

Echeburúa, E. & Corral, P. (2009). Las adicciones con o sin droga: una patología de la libertad. In E. Echeburúa, F.J. Labrador & E. Becoña (Eds.). Adicción a las nuevas tecnologías en adolescentes y jóvenes (pp. 29-44). Madrid: Pirámide.

Echeburúa, E. & Corral, P. (2010). Adicción a las nuevas tecnologías y a las redes sociales en jóvenes: un nuevo reto. Adicciones, 22 (2), 91-96.

Garmendia, M., Garitaonandia, C., Martínez, G. & Casado, M.A. (2011). Riesgos y seguridad en internet: Los menores españoles en el contexto europeo. Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal He rriko Unibertsitatea, Bilbao: EU Kids Online.

Graner, P., Beranuy-Fargues, M., Sánchez-Carbonell, C. & al. (2007). ¿Qué uso hacen los jóvenes y adolescentes de Internet y del móvil? In L. Álvarez-Pousa & J. E. Pim (Eds.), Congreso Comunicación e Xuventude: Actas do Foro Internacional, 71-90.

Granero, R., Doménech, J.M., Bonillo, A. & Ezpeleta, L. (2001). Psicología basada en la evidencia: Un nuevo enfoque para me jorar la toma de decisiones. Madrid: VII Congreso de Metodología de las Ciencias Sociales y de la Salud.

Griffiths, M.D. (2005). Internet Abuse in the Workplace, Issues and Concerns for Employers and Employment Counselors. Journal of Employment Counseling, 40, 87-96.

Haines, M. & Spear, S.F. (1996). Changing the Perception of the Norm: A Strategy to Decrease Binge Drinking Among College Students. Journal of American College Health, 45, 134-140.

Hunsley, J. & Johnston, C. (2000). The Role of Empirically Supported Treatments in Evidence-Based Psychological Practice: A Canadian Perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 7, 269-272.

Hunter, S. & Boyle, J. (2004). Appraisal and Coping Strategy Use in Victims of School Bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 83-107.

Lapinski, M.K. & Rimal, R.N. (2005). An Explication of Social Norm. Communication Theory, 5 (2), 127-147

Lindqvist, P. & Skipworth, J. (2000). Evidence-Based Reha bi li tation in Forensic Psychiatry. British Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 320-323.

Liu, H. (2007) Social Network Profiles as Taste Performances. Jour nal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13 (1), 252-275.

Luengo-Latorre, J.A. (2011). Cyberbullying, guía de recursos para centros educativos. La intervención en los centros educativos: Materiales para equipos directivos y acción tutorial. Madrid: De fensor del Menor.

Machargo, J., Luján, I., León, M.E., López, P. & Martín, M.A. (2003). Videojuegos por los adolescentes. Anuario de Filosofía, Psicología y Sociología, 6, 159-172.

Marín, I. & González-Piñal, R. (2011). Relaciones sociales en la sociedad de la Información. Prisma Social, 6, 119-137.

McLaughlin, J.H. (2010). Crime and Punishment: Teen Sexting in Context. (http://works.bepress.com/julia_mclaughlin) (02-02-2012).

Menjivar, M. (2010). El sexting y l@s nativ@s neo-tecnológic@s: Apuntes para una contextualización al inicio del siglo XXI. Actua lidades Investigativas en Educación, 10 (2), 1-23.

Mercadal, R. (2009). Pantallas amigas. Comunicación y Peda go gía, 239, 55-57.

Monge, A. (2010). De los abusos y agresiones sexuales a menores de trece años tras la reforma penal de 2010. Revista de Derecho y Ciencias Penales, 15, 85-103.

Montero, I. & León, O.G. (2007). Guía para nombrar los estudios de investigación en Psicología. International Journal of Clini cal and Health Psychology, 7, 847-862.

Navarro, F., Giribet, C. & Aguinaga, E. (1999). Psiquiatría basada en la evidencia: Ventajas y limitaciones. Psiquiatría Biológica, 6, 77-85.

Nosko, A., Wood, E. & Molema, S. (2010). All about Me: Dis clo sure in Online Social Networking profiles: The Case of Face book. Computers in Human Behavior. 26 (3), 406-418.

OECD (Ed.) (2005). Policy Coherence for Development. Pro moting Institutional Good Practice. The Development Dimension Series. Paris: OECD.

Ortega, R. & Del Rey, R. (2001). Aciertos y desaciertos del proyecto Sevilla Anti-violencia Escolar (SAVE). Revista de Educación. 324, 253-270.

Ortega, R. & Mora-Merchán, J.A. (2008). Las redes de iguales y el fenómeno del acoso escolar: explorando el esquema dominio-sumisión. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 31 (4), 515-528.

Ortega, R. (1997). El proyecto Sevilla Anti-violencia Escolar. Un modelo de intervención preventiva contra los malos tratos entre iguales. Revista de Educación, 313, 143-158.

Ortega, R., Calmaestra, J. & Mora-Merchán, J. (2008). Cy ber bullying. International Journal of Psychology and Psycho lo gical Therapy, 8(2), 183-192.

Ortega, R., Del Rey, R. & Sánchez, V. (2011). Nuevas dimensiones de la convivencia escolar y juvenil. Ciberconducta y relaciones en la Red: Ciberconvivencia. Madrid: Observatorio Estatal de la Convivencia Escolar. Informe interno.

Piscitelli, A. (2006). Nativos e inmigrantes digitales, ¿Brecha generacional, brecha cognitiva, o las dos juntas y más aún? Revista Me xi cana de Investigación Educativa, 11 (28), 179-185.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon, 9, 1-6.

Reig, D. & Fretes, G. (2011). Identidades digitales: límites poco claros. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, 418, 58-59.

Ricoy, M.C., Sevillano, M.L. & Feliz, T. (2011). Competencias necesarias para la utilización de las principales herramientas de Internet en la educación. Revista de Educación, 356, 483-507.

Rimal, R., Lapinski, M., Cook, R. & Real, K. (2005). Moving Toward a Theory of Normative In?uences: How Perceived Bene?ts and Similarity Moderate the Impact of Descriptive Norms on Behaviors. Journal of Health Communication, 10, 433-50.

Rimal, R.N. & Real, K. (2003). Understanding the Influence of Perceived Norms on Behaviors. Communication Theory, 13, 184-203.

Rimal, R.N. & Real, K. (2005). How Behaviors are Influenced by Perceived Norms: A Test of the Theory of Normative Social Be havior. Communication Research, 32, 389-414.

Sackett, D.L., Richardson, W.S., Rosenberg, W. & Haynes, R.B. (1997). Medicina basada en la evidencia: Cómo ejercer y enseñar la MBE. Churchill Livingston.

Smith, P.K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, C. & Tippett, N. (2006). An Investigation into Cyberbullying, its Forms, Awareness and Impact, and the Relationship between Age and Gender in Cy ber bullying. Research Brief RBX03-06. London: DfES. (www.antibullyingalliance.org.uk/downloads/pdf/cyberbullyingreportfinal230106_000.pdf) (10-06-2007).

Smith, P.K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S. & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: its Nature and Impact in Se condary School Pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psy chiatry, 49, 376-385.

Stoiber, K.C. & Kratochwill, T.R. (2001). Evidence-based Inter vention Programs: Rethinking, Refining, and Renaming the New Standing Section of School Psychology Quarterly. School Psy chology Quarterly, 16, 1-8.

Stone, N. (2011). The ‘Sexting’ Quagmire: Criminal Justice Res ponses to Adolescents’ Electronic Transmission of Indecent Images in the UK and the USA. Youth Justice, 11, 3, 266-281.

Stutzman, F. (2006). An Evaluation of Identity-sharing Behavior in Social Network Communities. Journal of the International Digital Media and Arts Association, 3 (1), 10-18.

Tejerina, O. & Flores, J. (2008). E-legales. Bilbao: Edex.

Ttofi, M.M. & Farrington, D.P. (2009). School-based Programs to Reduce Bullying and Victimization. Campbell Systematic Re views. Oslo: Campbell Collaboration.

Turkle, S. (1997). La vida en la pantalla. Barcelona: Paidós

Wechsler, H. & Kuo, M. (2000). College Students Define Binge Drinking and Estimate its Prevalence: Results of a National Survey. Journal of American College Health, 49, 57-64.

Winocur, R. (2006). Internet en la vida cotidiana de los jóvenes. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 68 (3), 551-580.

Document information