Summary

Background

Pilonidal sinus disease is an inflammatory disease seen in the intergluteal region, which is a commonly encountered problem in surgical practice that mostly affects young people. The aim of this study is to assess the effectiveness of the modified Limberg flap technique with eyedrop excision in the treatment of pilonidal sinus disease.

Patients

The study population consisted of 91 patients with pilonidal disease in the sacrococcygeal region who underwent operation between June 2010 and December 2012. All cases underwent eyedrop-shaped excision and modified Limberg flap reconstruction.

Results

The mean operative time was 41.2 ± 6.7 minutes. All patients were followed up for >8 months, and the mean follow-up period was 13.1 ± 3.7 months. There were three wound dehiscences because of fecal contamination and riding cycle on postoperative Day 5. Seroma and flap echimosis were observed in two and four cases, respectively. Five patients experienced recurrence in this series (4.5%).

Conclusion

The results of the present study suggest that use of the eyedrop-shaped modified Limberg flap is associated with a lower maceration and recurrence rate when compared with the available data on the use of the Limberg flap. Flap necrosis and wound healing was better, and the routine use of drains did not affect the wound-related complications and recurrence rates.

Keywords

Limberg flap;modified Limberg;pilonidal sinus

1. Introduction

Pilonidal sinus disease (PSD) is a common painful inflammatory disease seen in the intergluteal region. This disease is largely seen in young people between the ages of 15 years and 35 years, and males are affected about three to four times more often than females.1 The incidence of the disease is 26/100,000 in the general population.2 Although its etiology remains controversial, the most generally accepted theory is the penetration of free hair into the skin at the site of the entrance (maceration, scar, humidity) and the depth,1 and is associated with a foreign body reaction. PSD is accepted as an acquired pathology that has not been changed by traditional surgical or nonsurgical intervention in recent years.3 Although the disease has been reported in different parts of the body,4 ; 5 the most common site is the intergluteal cleft.

Although many surgical and nonsurgical methods have been proposed, no clear consensus on the optimal treatment has been reported so far in the literature. Medical treatment modalities such as phenol, silver nitrate, and electrocauterization of the cavity are used to treat PSD. Many techniques have been advocated for the surgical treatment of chronic pilonidal disease since its first description by Anderson in 1847.6 There are also surgical options after excising the cavity, such as primary closure, leaving it to secondary healing, and sophisticated procedures such as Z-plasty, split-skin grafting, advancement flap rotation, or Karydakis flap.7

The ideal method should be simple, inflict minimal postoperative pain, require short a hospitalization and minimal wound care, allow a rapid return to normal activity, and have a low recurrence rate. The main problem after PSD surgery is recurrence, and recurrence rates have been reported in the literature to range from 3% to 46%, depending on the technique used.8 The lowest recurrence rates have been reported with local flap reconstructions including the Limberg flap. Modifying the natal cleft and lateralizing the scar from the midline are the most important factors to eliminate the essential causative factors of PSD.7 The Limberg flap technique has several drawbacks including undesirable cosmetic results, necrosis at the vertex of flap, and incision site skin maceration.

Although we had achieved advantages with the modified Limberg flap (MLF) technique, the aim of this study was to present the clinical results of the eyedrop-shaped Limberg flap technique performed in 91 patients with PSD, an approach that allows surgeons to overcome the flap complications of the rhomboid narrow angle flap.

2. Materials and methods

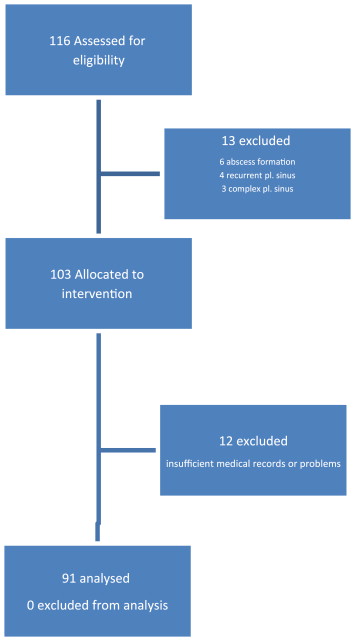

Ninety-one patients who had been operated on for PSD between June 2010 and December 2012 were analyzed at the Samsun Military Hospital in Samsun, Elbistan State Hospital in Kahramanmaras, and Suleyman Demirel University in Isparta, Turkey. Patients with concurrent abscess formation (n = 6), recurrent pilonidal sinus (n = 4), a more complex pilonidal sinus (orifices of the sinus extending laterally or near the anus; n = 3), and insufficient medical records or problems (n = 12) were excluded. Thus, 91 patients with PSD were enrolled for analysis in this prospective study ( Fig. 1).

|

|

|

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the patients. |

The patients with PSD underwent the procedure, wherein eyedrop excision and MLF technique were used without any specific selection criteria. Infected sinuses were treated with antibiotics prior to the surgery, and abscesses were managed with surgical drainage combined with antibiotic therapy. After the details of the surgical procedure were explained to the participants, the operations were performed by the same surgeon.

The patients age, sex, duration of preoperative symptoms, operation time, mean hospital stay, postoperative wound complications, maceration rate and recurrence rate, and hypoesthesia in the gluteal region were recorded during follow-up or at the last interview. Clinical assessments were performed postoperatively on the 1st day, 3rd day, 5th day, and 10th day and by telephone on the 1st month, 3rd month, 6th month, and 12th month.

2.1. Operative technique

The patients were hospitalized, and the site of the operation (gluteal and sacral region) was shaved on the day of the surgery. Patients were operated on under spinal anesthesia. Ampicillin-sulbactam (1 g) was administered to all patients as prophylaxis 30–60 minutes. prior to the surgery. The patients received no bowel preparation. An adhesive tape was used to part the buttocks. The patients were placed in the jackknife position.

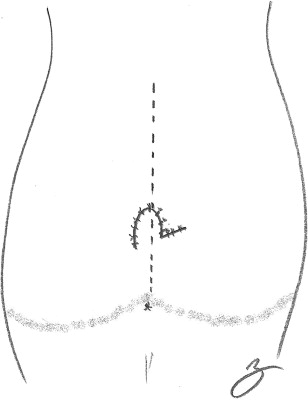

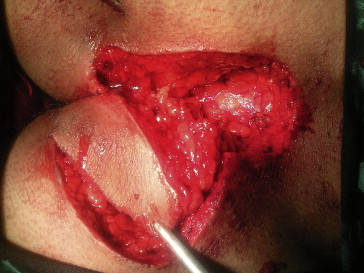

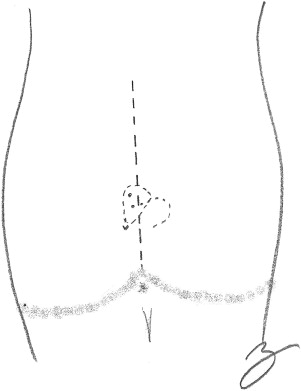

Neither methylene blue or H2O2 was injected. All sinus tracts were resected en bloc with an eyedrop-shaped excision without vertex, using a surgical blade ( Figure 2, Figure 3 ; Figure 4). The inferior apex of the excision was placed about 1–2 cm lateral to the midline. A Limberg flap, including skin, subcutaneous tissue, and fascia of the gluteal muscle, was prepared ( Figure 5 ; Figure 6) with meticulous hemostasis, and no drain was used. The Limberg flap was sutured with deep and interrupted 2–0 Vicryl sutures to the edges of the defect. The skin was closed with 3–0 polypropylene sutures (Fig. 7).

|

|

|

Figure 2. Marking of excision. |

|

|

|

Figure 3. Excision of sinüs and marking of flap. |

|

|

|

Figure 4. Drawing of excision. |

|

|

|

Figure 5. Prepared flap. |

|

|

|

Figure 6. Drawing of flap. |

|

|

|

Figure 7. Flap is shown immediately after surgery. |

The patients were followed up by physical examination on the 1st day, 3rd day, and 5th day after the operation, and the sutures were removed on postoperative Day 10. All patients were contacted monthly by telephone to inquire about any relevant symptoms in the first 6 months, and at the end of 12 months at each of the follow-up visits. The patients were reminded to keep the perineal and gluteal region clean and dry at every visit (Fig. 8).

|

|

|

Figure 8. Flap is shown 1 month after the operation. |

2.2. Postoperative follow-up

The patients were asked to return to the clinic on postoperative Day 3, Day 5, and Day 10. The skin sutures were removed on the 10th postoperative day. The long-term follow-up (1st month, 3rd month, 6th month, and 12th month) was performed via telephone interview.

Patients who have no complaint(s) were also recalled, and physical examination was performed. Maceration was described as the softening and breaking down of skin resulting from prolonged exposure to moisture.9 Wound dehiscence was described as the separation of the layers of the surgical wound after opening the sutures. The term “recurrence” was used when symptoms of the disease recurred after an interval following complete wound healing.

3. Results

There were 82 male and nine female patients. Eleven patients had been treated for infected pilonidal sinus. All of these patients were free of infection at the time of the operation. The mean operation time was 41.2 ± 6.7 (range, 35–62) minutes. The mean hospital stay was 3 days. Tenoxicam (40 mg/d) was sufficient for pain control in all patients. There were no major complications nor mortality.

All patients were followed up for >8 months, and the mean follow-up period was 13.1 ± 3.7 (range, 8–15) months. Wound dehiscence was observed in three patients, and no flap necrosis was detected. Drains were used in only seven patients. The general characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

| Mean | |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 25.8 (16–45) |

| Sex (M/F) | 82/9 |

| Duration of symptoms (mo) | 16.4 (9–22) |

| Operating time (min) | 41.2 (35–62) |

Two patients who were found to have a seroma were managed with simple drainage. Four cases of flap ecchymosis were observed. Surgical drainage was not applied, and all patients were treated only with oral antibiotics. Wound dehiscence was detected in three patients; one had ridden on a motorcycle on the 5th day postoperatively and fecal contamination was observed in the other patients on the 5th postoperative day and 10th postoperative day despite the recommendations given for local hygiene. Maceration was detected in three patients, located at the lower part of the incision near the anal region. Owing to a flattening of the natal cleft and preventing the flap from folding in our flap technique, these patients were successfully treated conservatively. There were five cases (4.5%) of recurrence during follow-up, which were treated with a marsupialization technique (Table 2). The median time of recurrences is 6 (range, 3–11) months. We did not detect any case of flap necrosis.

| Wound complication | |

|---|---|

| Hypoesthesia | 5 |

| Hematoma | 0 |

| Seroma | 2 |

| Wound dehiscence | 3 |

| Maceration | 3 |

| Length of hospital stay (d) | 3.3 (2–5) |

| Recurrence | 5 |

4. Discussion

PSD, as first described by Hodges,10 is a chronic inflammatory disease with intractable symptoms located on the intergluteal region and seen mostly in the younger population. If left untreated, the patients quality of life is seriously affected.7

The etiopathogenesis of PSD is still under debate. Although hypotheses for the occurrence of a pilonidal sinus have been based on an embryologic origin, the disease has largely been accepted to be caused by an accumulation of hair penetrating the skin and to be an acquired condition.3 ; 7 The depth of the intergluteal sulcus, the number of loose hair, and the stiffness of the hair play important roles in the etiology. Lacerations in the skin due to trauma and erosions due to moisture and friction, large pores, and the weakness of the skin at the midline can facilitate entrance of the hair.11 The reason for the wide acceptance of the acquired theory may be the high recurrence rates of up to 30% even after the most radical local excisions of pilonidal disease, which suggests that a pilonidal sinus is an acquired new disease rather than the persistence of some existing sinuses.7 ; 12 Moreover, Karydakis7 suggested three factors related to the development of this disease: loose hair as the invader, a force that causes hair insertion, and the vulnerability of the skin to hair insertion at the depth of the natal cleft—all of which are strong lines of evidence supporting the acquired theory.

Harlak et al11 demonstrated that maintaining good hygiene in the intergluteal sulcus is important in preventing the disease. Some studies have shown that, in addition to a good surgical technique, elimination of preventable risk factors such as hygiene at the intergluteal sulcus is important to prevent recurrence. Therefore, patients in this study were advised regarding the importance of local hygiene.13 ; 14 Recurrence was detected in five patients who were unable to maintain good hygiene in the intergluteal and perianal regions.

There are many treatment methods, surgical or nonsurgical, for PSD in the sacrococcygeal region. Conservative methods such as phenol injection, laser epilation, and shaving are used in the early stages of PSD with varying rates of success.15 ; 16 Surgical methods including excision and primary closure, lay-open technique, marsupialization, various flap techniques such as the Limberg flap, and cleft closure17 ; 18 have also been performed for treating PSD, and many authors have claimed that flap techniques are superior to primary closure and lay-open techniques.19 However, no optimal treatment approach with low complication and recurrence rates has been achieved as yet.12 The ideal surgical approach for PSD has been described as follows, “it should be simple, necessitate a short hospital stay, and have a low recurrence rate.”19

Primary closure of the wound after excision of the pilonidal sinus is associated with a high recurrence rate. In the literature, the recurrence rate after primary closure has ranged from 4% to 25%.14 Natal clefts do not flatten, thanks to simple excision and primary closure or open wound healing, and cannot prevent the penetration tendency of hair to the skin at depths of the natal cleft and may lead to more discomfort, and thereby longer hospitalization.7 ; 12 Karydakis7 described his own method, which involves removing the deep sulcus and leaving no scar tissue at the midline, and reported a complication rate of 8.5% (infection and fluid accumulation) and a recurrence rate of <1%.4; 5; 8 ; 20

Wide excision of the sinus and reconstruction of the defect by different flaps has become more widespread in recent years. Flap techniques shorten the duration of hospital stay and are associated with early healing of the wound. The theoretical aim of a flap technique is to flatten and lateralize the natal cleft, which should eliminate predisposing etiopathogenetic factors for the PSD and avoid median recurrences.7 ; 12 Limberg flap transposition (LFT) has become one of the most popular flap techniques in the treatment of sacrococcygeal PSD21 since it was first described by Azab et al,22 who reported its excellent results in 1984. It changes the anatomy of the gluteal region by flattening the intergluteal cleft. In contrast to primary closure, the Limberg flap after excision of the pilonidal sinus has been associated with a recurrence rate of LFT varying from 0% to 8.5%, and it was close to 3% in a large series.22 ; 23

However, when the patient has an asymmetric and long PSD, the surgeon has to prepare the extended flap, by decreasing the flap tip angle to 30° like the Webster and Dufourmentel flaps. However, this modification may probably disrupt the blood supply to the flap edge. Our flap shape has an obtuse angle, which prevents complications due to blood supply such as flap ischemia and wound dehiscence. Hence, owing to lateralization of the inferior apex and flattening of the natal cleft in the modified technique, we were able to overcome flap complications and recurrences, because all macerations and the majority of recurrences were detected at the lower part of the flap in a large classic Limberg flap series.

In a study comparing primary closure and Limberg flap, as reported by Akca et al,24 the Limberg group was superior to the primary closure group in terms of recurrence rate, postoperative pain, early mobilization, time of return to work, and postoperative complications. Can et al25 reported that modification of the Limberg procedure may reduce the early complication rate compared with that of the Karydakis procedure. In addition, primary closure has several other drawbacks such as wound dehiscence, infection, longer sitting time on the toilet, and late return to work.

In the literature, the rate of wound-related complications (e.g., infection, seroma, hematoma, dehiscence, or necrosis) after LFT varies from 4.7% to 15.9%.23 The complication rates have been reported to reach 15.9% in a small series and fall to as low as 4.7% in a large series.23 In our series, two cases of seroma and four cases of flap echimosis were observed (Fig. 9). Maceration of the surgical incision site was detected in three patients. We detected no flap necrosis in our cases.

|

|

|

Figure 9. View of echimosis in flap. |

One of the major problems of the Limberg flap technique is the relatively poor wound healing, particularly at the lower pole of the flap near the anal canal where serious maceration and wound dehiscence can be seen (Fig. 10). Kırkıl et al26 showed that all except one of the recurrences were observed in the lower corner of the rhombic excision. This observation supports the conclusions of Cihan et al,27 who realized that the inferior midline after LFT was frequently macerated, healed slowly, and might even be a source of recurrences. This problem has been overcome owing to the lateralization of the inferior apex. Mentes et al28 and Tekin29 have stated a need for modifying the Limberg flap procedure. The Limberg flap technique was modified by performing the rhomboid excision asymmetrically to place the lower end of the flap about 1–2 cm lateral to the intergluteal cleft. They reported that the site of recurrence, which was located at the lower flap pole, stayed within the intergluteal sulcus and indicated that this site was the weakest point of the Limberg flap. In light of this information, we have developed an eyedrop excision with modified rhomboid excision that has been lateralized (thus avoiding forming an acute angle) to avoid complications in the flap especially the suture line. In our series, the recurrence and flap complication rates are superior to those of the conventional Limberg flap techniques in the literature. Some large series28 show that the maceration and recurrence rates were lower in the MLF technique, and all macerations were detected in the lower part of the flap tailored on the intergluteal sulcus in the classical Limberg flap. Our flap technique is more effective in flattening the natal cleft, including the most inferior part, and we detected maceration in only three cases.

|

|

|

Figure 10. View of classical rhomboid flap. |

In some reports, the use of drains is strongly recommended in pilonidal sinus operations, especially after flap procedures. Nevertheless, we do not use drains routinely. However, it should be noted that a controlled study showed that wound problems, length of hospital stay, morbidity, and recurrence rates did not increase in the absence of postoperative draining of the cavity. Another study also demonstrated that drain placement after rhomboid excision and LFT might negatively affect the postoperative complication rate, although the mean operation time was significantly longer in the nondrained group.5; 20 ; 28 We used drains in only seven patients who had a large tissue defect and insufficient hemostasis.

The recurrence rate in the current study is 4.5%, and the median time of recurrence is 6 (range, 3–11) months. Maceration rates were comparable to those of previous MLF studies.5 Most patients with maceration problems and recurrences were observed to have poor personal hygiene (e.g., fecal contamination). A common complaint after flap surgery was hypoesthesia on the flap, which occurred in five patients in the current study. We think that the cause is the large pedicle and the round shape of our flap.

5. Conclusion

The results of the current study showed that the eyedrop shape MLF technique without the use of a drain should be used instead of the rhomboid excision and the Limberg flap for the treatment of uncomplicated PSD because of lower recurrence and wound site complication rates, shorter operation time, and shorter length of hospital stay. Moreover, eyedrop excision has lower flap wound complication and hypoesthesia rates particularly at the upper pole of the flap.

References

- 1 I. McCallum, P.M. King, J. Bruce; Healing by primary versus secondary intention after surgical treatment for pilonidal sinus; Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 17 (2007), p. CD006213

- 2 K. Soendenaa, E. Andersen, I. Nesvik, J.A. Søreide; Patient characteristics and symptoms in chronic pilonidal sinus disease; Int J Colorectal Dis, 10 (1995), pp. 39–42

- 3 J.A. Surrell; Pilonidal disease; Surg Clin N Am, 74 (1994), pp. 1309–1315

- 4 S. Chintapatla, N. Safarani, S. Kumar, N. Haboubi; Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus: historical review, pathological insight and surgical options; Tech Coloproctol, 7 (2003), pp. 3–8

- 5 O. Mentes, M. Bagci, T. Bilgin, O. Ozgul, M. Ozdemir; Limberg flap procedure for pilonidal sinus disease: results of 353 patients; Langenbecks Arch Surg, 393 (2008), pp. 185–189

- 6 P.R. Kitchen; Pilonidal sinus: excision and primary closure with a lateralised wound the Karydakis operation; Aust NZ J Surg, 52 (1982), pp. 302–305

- 7 G.E. Karydakis; Easy and successful treatment of pilonidal sinus after explanation of its causative processes; Aust NZ J Surg, 62 (1992), pp. 385–389

- 8 A. Shafik; Electrocauterization in the treatment of pilonidal sinus; Int Surg, 81 (1996), pp. 83–84

- 9 K.F. Cutting; The causes and prevention of maceration of the skin; J Wound Care, 8 (1999), pp. 200–201

- 10 R.M. Hodges; Pilonidal sinus; Boston Med Surg J, 103 (1880), pp. 485–486

- 11 A. Harlak, Ö. Mentes, S. Kilic, et al.; Sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease: analysis of previously proposed risk factors; Clinics (Sao Paulo), 65 (2010), pp. 125–131

- 12 S. Petersen, R. Koch, S. Stelzner, et al.; Primary closure techniques in chronic pilonidal sinus: a survey of the result of different surgical approaches; Dis Colon Rectum, 45 (2002), pp. 1458–1462

- 13 F.J. Conroy, N. Kandamany, P.J. Mahaffey; Laser depilation and hygiene: preventing recurrent pilonidal sinus disease; J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg, 61 (2008), pp. 1069–1072

- 14 J. Odili, D. Gault; Laser depilation of the natal cleft: an aid to healing the pilonidal sinus; Ann R Coll Surg Engl, 84 (2002), pp. 29–32

- 15 N. Kaymakcioglu, G. Yagci, A. Simsek, et al.; Treatment of pilonidal sinus by phenol application and factors affecting the recurrence; Tech Coloproctol, 9 (2005), pp. 21–24

- 16 J.R. Lukish, T. Kindelan, L.M. Marmon, M. Pennington, C. Norwood; Laser epilation is a safe and effective therapy for teenagers with pilonidal disease; J Pediatr Surg, 44 (2009), pp. 282–285

- 17 S.N. Gilani, H. Furlong, K. Reichardt, A.O. Nasr, G. Theophilou, T.N. Walsh; Excision and primary closure of pilonidal sinus disease: worthwhile option with an acceptable recurrence rate; Ir J Med Sci, 180 (2011), pp. 173–176

- 18 M.A. Abbas, T. Tejerian; Unroofing and marsupialization should be the first procedure of choice for most pilonidal disease; Dis Colon Rectum, 49 (2006), p. 1242

- 19 T. Mahdy; Surgical treatment of the pilonidal disease: primary closure or flap reconstruction after excision; Dis Colon Rectum, 51 (2008), pp. 1816–1822

- 20 T. Colak, O. Turkmenoglu, A. Dag, T. Akca, S. Aydin; A randomized clinical study evaluating the need for drainage after Limberg flap for pilonidal sinus; J Surg Res, 158 (2010), pp. 127–131

- 21 A. Gurer, I. Gomceli, M. Ozdogan, N. Ozlem, S. Sozen, R. Aydin; Is routine cavity drainage necessary in Karydakis flap operation? A prospective, randomized trial; Dis Colon Rectum, 48 (2005), pp. 1797–1799

- 22 A.S. Azab, M.S. Kamal, R.A. Saad, A.L. Abou, K.A. Atta, N.A. Ali; Radical cure of pilonidal sinus by a transposition rhomboid flap; Br J Surg, 71 (1984), pp. 154–155

- 23 O.F. Ersoy, S. Karaca, H.A. Kayaoglu, N. Ozkan, A. Celik, T. Ozum; Comparison of different surgical options in the treatment of pilonidal disease: retrospective analysis of 175 patients; Kaohsiung J Med Sci, 23 (2007), pp. 67–70

- 24 T. Akca, T. Colak, B. Ustunsoy, et al.; Randomized clinical trial comparing primary closure with the Limberg flap in the treatment of the primary sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease; Br J Surg, 92 (2005), pp. 1081–1084

- 25 M.F. Can, M.M. Sevinc, O. Hancerliogullari, et al.; Multicenter prospective randomized trial comparing modified Limberg flap transposition and Karydakis flap reconstruction in patients with sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease; Am J Surg, 200 (2010), pp. 318–327

- 26 C. Kırkıl, A. Boyuk, N. Bulbuller, E. Aygen, K. Karabulut, S. Coskun; The effects of drainage on the rates of early wound complications and recurrences after Limberg flap reconstruction in patients with pilonidal disease; Tech Coloproctol, 15 (2011), pp. 425–429

- 27 A. Cihan, B.H. Ucan, M. Comert, A. Cesur, G.K. Cakmak, O. Tascilar; Superiority of symmetric modified Limberg flap for surgical treatment of pilonidal disease; Dis Colon Rectum, 49 (2006), pp. 244–249

- 28 B.B. Mentes, S. Leventoglu, A. Cihan, et al.; Modified Limberg transposition flap for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus; Surg Today, 34 (2004), pp. 419–423

- 29 A. Tekin; A simple modification with the Limberg flap for chronic pilonidal disease; Surgery, 138 (2005), pp. 951–953

Document information

Published on 26/05/17

Submitted on 26/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?