Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

The goal of this cross-cultural study was to analyze and compare the cybervictimization and cyberaggression scores, and the problematic Internet use between Spain, Colombia and Uruguay. Despite cultural similarities between the Spanish and the South American contexts, there are few empirical studies that have comparatively examined this issue. The study sample consisted of 2,653 subjects aged 10-18 years. Data was collected through the cyberbullying questionnaire and the Spanish version of the “Revised generalized and problematic Internet use scale”. Results showed a higher prevalence of minor cyberbullying behavior in Spain between 10-14 years. In the three countries compared, there was a higher prevalence of two types of bystanders: the defender of the victim and the outsider, although in Colombia there were more profiles of assistant to the bully. Regarding the problematic use of the Internet, there were not differences between the three countries. We provide evidence on the relationship between cybervictimization and cyberaggression and problematic use of the Internet. The dimensions of compulsive use and regulation of mood are the best predictors of cyberbullying. We discuss our results in relation to the possible normalization of violence and its lack of recognition as such.

1. Introduction

In the last decades, advances in technology and Internet tools have transformed the way we access information, communicate, express ourselves, and interact. However, despite its advantages, the Internet also involves some risks. Many of the psychosocial problems occurring in virtual life replicate the problems found in “real” life (e.g., peer abuse or gender-based abuse). Additionally, new problems have arisen as a result of the misuse of the Internet and/or digital media. The psychosocial problems associated with new technologies are addressed by “cyberpsychology”. This branch of psychology focuses on the relationship between human beings and the use of technology in daily life.

One of the problems linked to the misuse of new technologies is cyberbullying, defined as any behavior performed through electronic or digital media –prevailingly cell phones and the Internet– by individuals or groups that repeatedly communicate hostile or aggressive messages intended to inflict harm or discomfort on others (Tokunaga, 2010). The most common behaviors include flaming, denigration (insults and humiliation), threatening and offensive calls or messages, impersonation, exclusion, and outing (Kowalski, Limber, & Agatston, 2012). Cyberbullying can occur anywhere at any time of the day, which aggravates uncertainty in the cybervictim and dramatically extends the potential audience. The identity of the perpetrator can be known or not (Tokunaga, 2010). This imbalance of power has a dramatic impact on the social and emotional well-being of the victim. Thus, cyberbullying affects the personality, self-esteem, social skills and ability of the victim to resolve conflicts (Zych, Ortega, & Del Rey, 2015). Notably, the role of cyberbystander is increasingly gaining relevance, and a range of preventive interventions focused on this role have been developed (e.g., the KIVA bullying prevention program; Salmivalli, Kärnä, & Poskiparta, 2011). Salmivalli (1999) studied in detail the role of bystanders in traditional bullying. The author noted that the role of bystanders in the prevention of perpetuation of bullying is crucial. The author identified five bystander sub-roles, namely: reinforcer of the bully, assistant of the bully, outsider, pro-victim, and defender of the victim, the latter being the most prevalent. Given the relevance of these sub-roles, understanding and identifying them is crucial. Little research has been conducted on this aspect so far.

Cyberbullying is a social problem for which prevalence and incidence have increased dramatically around the world in recent years (Aboujaoude, Savage, Starcevic, & Salame, 2015). Intensive research has been conducted on cyberbullying in the USA and Europe. In contrast, few efforts are being made in Latin America, where cyberbullying has been studied using different methodologies. In Spain, recent data reveal that cyberbullying occurs in all regions, with a mean prevalence of 26,65% (mean SD: 23,23%) for cybervictimization (CBV) and 24,64% for cyberaggression (CBA) (mean SD: 24,35%) (Zych, Ortega-Ruiz, & Marin-López, 2016). The prevalence of cyberbullying is considerably higher in Latin America. In Colombia, its prevalence ranges from 30% (Redondo & Luzardo, 2016; Redondo, Luzardo, García-Lizarazo, & Ingles, 2017) to 60% (Mura & Diamantini, 2013). In Argentina and Mexico, rates reach 49% (Laplacette, Becher, Fernández, Gómez, Lanzillotti, & Lara, 2011; Lucio & González, 2012). Conversely, other studies have shown a prevalence of CBV below 15% in Mexico (Castro & Varela, 2013; García-Maldonado, Joffre, Martínez, & Llanes, 2011), Uruguay (Lozano & al., 2011) and Chile (Varela, Pérez, Schwaderer, Astudillo, & Lecannelier, 2014). These inconsistencies across countries are surprising, given the common ties of language and culture between Spain and Latin America that make comparative studies relevant. However, little research has been conducted to elucidate the causes of such differences. Romera, Herrera-López, Casas, Ortega-Ruiz, and Gómez-Ortiz (2017) recently performed a study to examine the influence of interpersonal variables (perceived social self-efficacy and social motivation) in cyberbullying. The author established a homogeneous model for the Spanish and Colombian populations.

In relation to the use of the Internet, it is worth mentioning that the DSM-V (American Psychiatric Association, 2014) does not recognize addiction to or the intensive use of the Internet as an addictive disorder or as a “behavioral addiction”. However, this does not mean that it is not harmful. One of the most widely used and accepted terms is “problematic Internet use” (Caplan, 2010). This approach places emphasis on the potential dysfunctions and interferences that some use patterns can cause in relation to an individuals’ family, social and academic life. A large number of studies conducted in Spain (Gámez-Guadix, Orue, & Calvete, 2013), in Mexico (Gámez-Guadix, Villa-George, & Calvete, 2012), and in the European context (Blinka, Škarupová, Ševcíková, Wölfling, Müller, & Dreier, 2015) support the adoption of a cognitive-behavioral model to explain patterns of Internet misuse. These characteristics include a preference for online social interaction or compulsive use of the Internet, yet, little evidence has been published on the relationship between this construct and the different roles in cyberbullying, not to mention the scarcity of comparative data in different countries.

For this reason, the main goal of this study was to analyze and compare scores for CBA and CBV in Spain, Colombia, and Uruguay. Other secondary objectives include: (1) Analyzing the factorial structure of the questionnaires used for the samples of Colombia and Uruguay; 2) Describing and comparing the profile of cyberbystanders in the three countries; 3) Analyzing and comparing patterns of problematic Internet use in the three countries; and 4) Examining the relationship between a problematic Internet use and cyberbullying.

Based on the results of previous studies, our hypotheses were: (1) Higher scores for CBV and CBA would be obtained for the Colombian population; (2) The factorial structure of the questionnaires employed would be valid for the Colombian and Uruguayan sample; (3) The most common cyberbystander sub-role would be that of defender of the victim, with a homogeneous distribution across the three countries; (4) No differences would be observed in patterns of problematic Internet use across countries; (5) A correlation exists between problematic Internet use and CBV and CBA .

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample

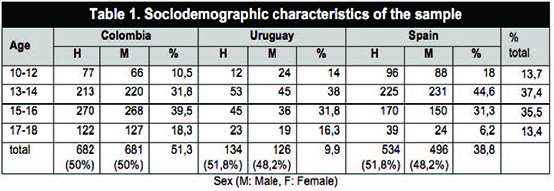

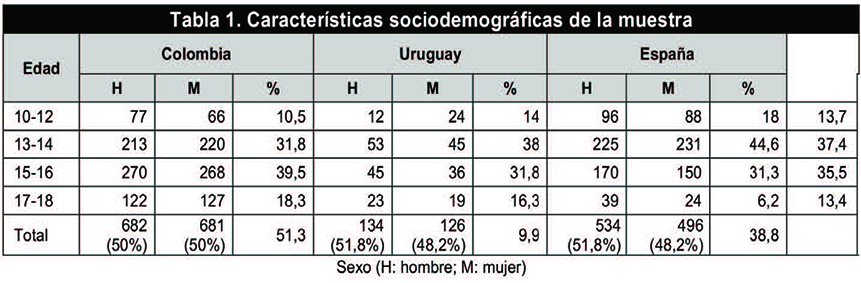

A cross-sectional, descriptive, analytical study was performed between March 2016 and July 2017. The sample was composed of 2.653 subjects 10 to 18 years of age (M=14,48; SD=1,66) from Colombia (51,3%), Uruguay (9,9%) and Spain (38,8%), of whom 50,8% were male (N=1,350) and 49,1% were female (N=1,303). Non-probabilistic incidental sampling was performed. Students were recruited from schools from north to south and from east to west of each country. A total of 12 schools were ultimately included. All centers were located in urban areas with a population of low-medium socioeconomic status. The Colombian sample was recruited from five public and three private schools located in Belen, Neiva, Bogota and Cali (n=1,363; mean age 14,82; SD=1,68). The sample from Uruguay was recruited from a private school in Melo (n=260, mean age: 14,48; SD=1,72). The Spanish sample was obtained from two public schools in Valencia and Asturias, and a semi-private school in Seville (n=1.030; mean age: 14,01; SD=1,49). Age and sex distribution by country are shown in Table 1.

2.2. Assessment instruments

Sociodemographic data included sex (male/female), age (categorized into four age groups: 10-12; 13-14; 15-16 and 17-18 years) and country (Colombia; Uruguay; Spain).

“Cuestionario de Ciberacoso” (CBQ; Calvete, Orue, Estévez, Villardón, & Padilla, 2010; Estévez, Villardón, Calvete, Padilla, & Orue, 2010; Gámez-Guadix, Villa-George, & Calvete, 2014). It contains a 17-item CBA scale and an 11-item CBV scale that evaluate behaviors associated with cyberbullying. Answers were scored on a 4-point Likert scale (0=never; 1=once or twice; 2= three or four times; 3=five or more times). Based on norm scores, three profiles, as follows: no problem (total score=0-1); minor cybervictim/cyberbully (scores =85th percentile and <95th; c) severe cybervictim/cyberbully (scores =95th percentile). The validation study in the Spanish population showed adequate reliability and validity. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the CBV and CBA dimensions were a=.86 and a=.82, respectively. Some terms and expressions were adapted for the Colombian and Uruguayan version of the questionnaire (e.g. “móvil” [mobile] was replaced with “celular”; “ordenador” [computer] with “computadora”; “agresor” [aggressor] with “matón”, and “acoso” [bullying] with “matoneo”, to name a few).

Participants were asked to define their role as cyberbystanders. Dimensions were established according to those described in the literature for traditional bullying (Salmivalli, 1999; Salmivalli Lagerspetz, Bjorkqvist, Osterman, & al., 1996), namely: a) assistant of the bully (never starts aggression, but occasionally supports the aggressor); b) reinforcer of the bully (supports the aggressor, but never joins him/her); c) outsider (never supports the aggressor or the victim); d) pro-victim (supports the victim but does nothing to stop the aggression); e) defender (often defends the victim).

Spanish version of the “Revised Generalized and Problematic Internet Use Scale” (GPIUS2, Gámez-Guadix & al., 2013). This 15-item questionnaire assesses problematic Internet use by five subscales: (1) preference for online social interaction; (2) mood modulated by the Internet; (3) negative effects; (4) cognitive concern; (5) compulsive use. Responses were measured on a 6-point Likert’s scale (1=absolutely disagree; 6= agree). Scores were coded based on four categories: a) no problem (score =1<2); b) isolated problems (=2<4); c) potentially problematic use (score =4<5); d) problematic use =5=6). The scale yielded adequate levels of reliability and validity for the Spanish sample. Cochrane’s coefficient for this study was a=.93. Again, the Colombian and Uruguayan versions were adapted.

2.3. Procedures

Centers were first contacted by e-mail and, when they agreed to participate, they were contacted by phone for submission of the documents required to participate in the study. The battery of questionnaires was distributed in the classroom by a collaborator and school staff (generally, the class tutor or school counselor). Respondents were encouraged to give truthful answers, not spending too much time to answer a specific question and note down any doubt on the last page. The time required by students to complete the questionnaires ranged from 25 to 40 minutes. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and no compensation was provided. By completing the questionnaires, the students tacitly agreed to participate in the study. Previous consent was obtained from parents and school management. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Asturias, Spain (Ref 11/15).

3. Analysis and results

Prior to data analysis, structural equation models were created for the CBQ using weighted least squares estimates (WLS) based on the Colombian and Uruguayan samples altogether. Confirmatory factor analysis of GPIUS2 was performed using the robust method of maximum likelihood (including Satorra-Bentler’s scaled ?2 index). The goodness of fit of the estimated models was assessed using the non-normative fit index (NNFI), and comparative fit index (CFI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). NNFI and CFI values above .90 indicate an acceptable goodness of fit, whereas values >.95 indicate good goodness of fit. RMSEA near .05 reveals excellent goodness of fit whereas values ranging from .05 to .08 indicate acceptable goodness of fit (Byrne, 2006; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Other analyses included: 1) verification of the normal distribution of the sample (Shapiro-Wilks test) and homogeneity of variance (Levene test); 2) analysis of frequencies and measures of central tendency and dispersion of means; 3) estimation of the standard score for the variables found to be correlated; 4) ?2 for post-hoc comparison of proportions; 5) partial correlations after adjustment for age; 6) analysis of variance using Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons; 7) stepwise multiple linear regression using F probability for an input value of .15 and an output of .20 to determine the GPIUS2 dimension that best predicted CBV and CBA scores in each country. When statistically significant differences were found, Cohen’s d was calculated to estimate the effect size of the difference. A p value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, 23 and Lisrel 8.5.

3.1. Validity and reliability of CBQ and GPIUS2 for the

samples from Colom-bia and Uruguay

The hypothesized model was composed of two correlated factors, one for CBA and another for CBV (following Gámez-Guadix & al., 2014). The solution obtained was satisfactory, with the adequate goodness of fit: ?2(234, N=1.620)=341; p<.001; RMSEA=.059 (95% CI: .053-.066); NNFI=.98; CFI=.98. The CBV dimension obtained a Cronbach’s alpha of .82 whereas CBA yielded .86.

As for GPIUS2, we used the five-item model described elsewhere (Caplan, 2010; Gámez-Guadix & al., 2013). Acceptable results were obtained: S-B ?2(84)=401; p<.001; RMSEA=.070 (IC 95%: .063-.079; NNFI=.98; CFI=.98). Cronbach’s alpha was .90.

3.2. Prevalence of cybervictimization and cyberaggression

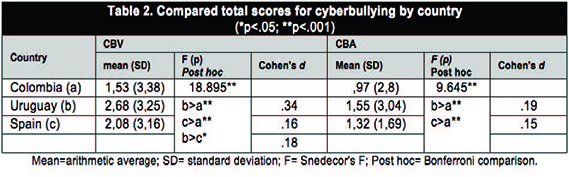

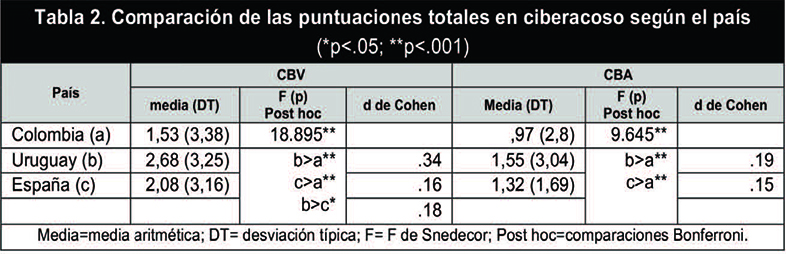

Table 2 shows differences across countries in total scores for CBV and CBA.

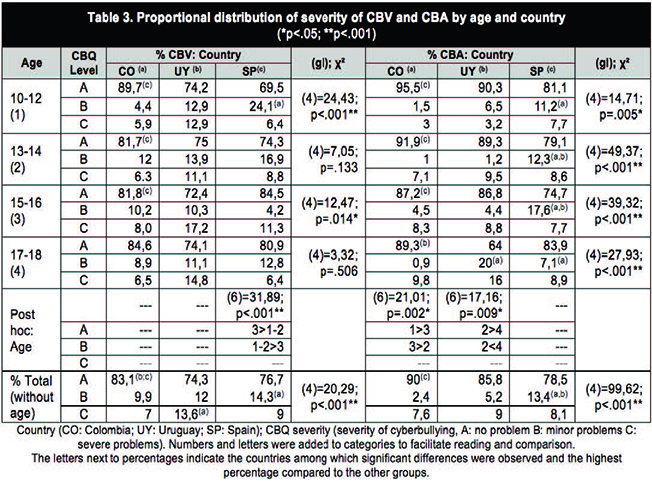

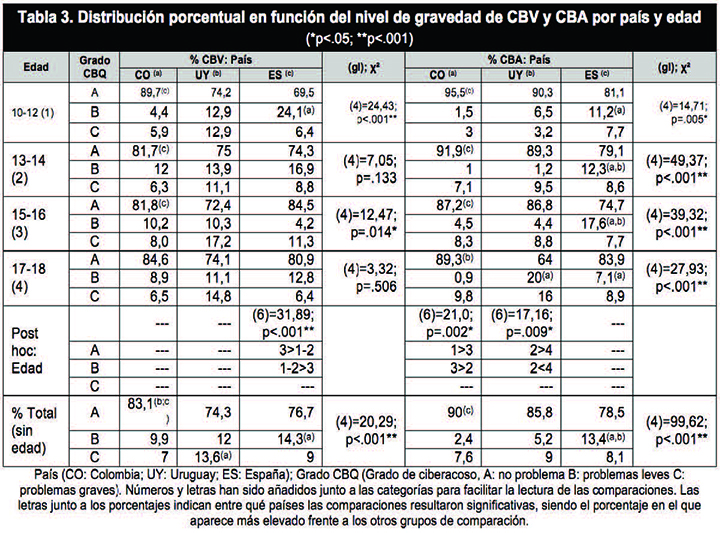

Differences in the proportional distribution of severity of cyberbullying are shown in Table 3 by age and country. The percentage of participants with no problems was higher in Colombia. In contrast, Spain showed a higher number of participants with minor problems (especially within the 10-14 age range). No significant differences were observed regarding severe cyberbullying.

Differences based on age and sex were observed in severe CBV in Colombia (10-12 year-old, male: 1,3%; female: 11,7%), ?²(2, N=8)=6,67; p<.05), and minor CBV ( 15-16 year old, male: 4,3%; female: 16,2%), ?²(2, N=37)=17,82; p<.001), with a higher percentage for female students. Differences were also observed in Spain in the category of minor CBV, but with a higher percentage for males (13-14 years, male: 25%; female: 7%), ?²(2, N=28)=18,13; p<.001. No gender- or sex-based differences were found in relation to CBA.

3.3. Profile of cyberbystander

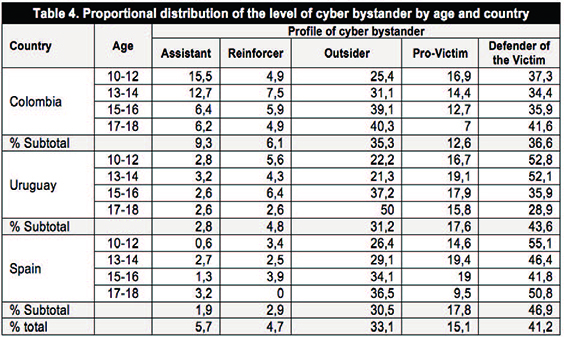

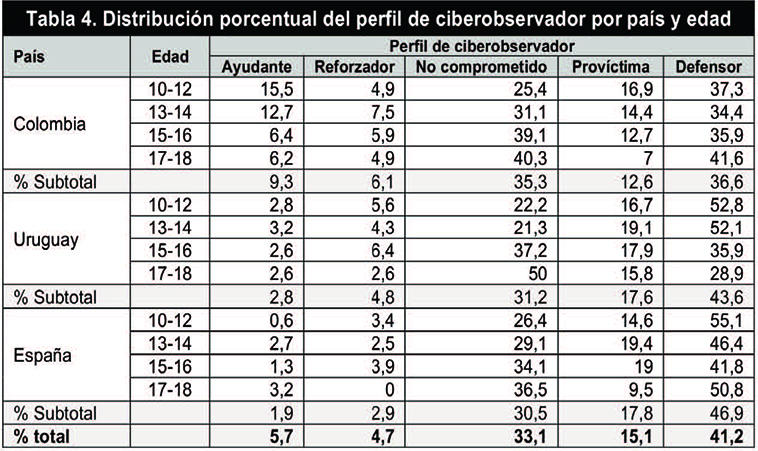

Based on the total scores shown in Table 4, most respondents reported playing the sub-role of defender of the victim, followed by that of the outsider. Thus, gender-based differences were observed, being male students more likely to play the role of outsider (34,9% vs. 31,2%), ?²(1, N=856)=4,21; p=.04, whereas female students were more likely to adopt a role of defenders of the victim (male: 38,2%; female: 44,3%; ?²(1, N=1.067)=3,96; p=.047).

Age-based differences were only observed in Colombia, ?²(12, N=1.339)=42,21; p<.001, being the role of assistant of the cyberbully prevalent among 10-12-year-old students as compared to 15-18-year-old students.

Statistically significant differences were observed between Colombia and Spain in the sub-roles of assistant ?²(2, N=151)=167,57; p<.001; reinforcer, ?²(2, N=123)=65,02; p<.001; and outsider, ?²(2, N=857)=275,26; p<.001. In contrast, the sub-roles of pro-victim, ?²(2, N=392)=86,61; p<.001, and defender of the victim, ?²(2, N=1.069)=258,07; p<.001, were significantly more prevalent in Spain than in Colombia.

3.4. Problematic Internet use

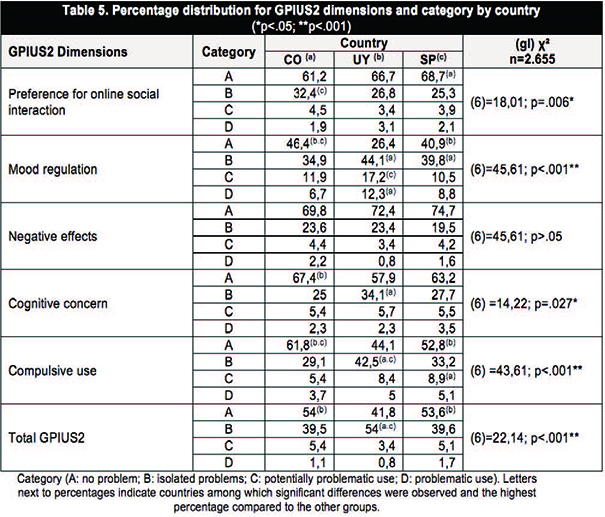

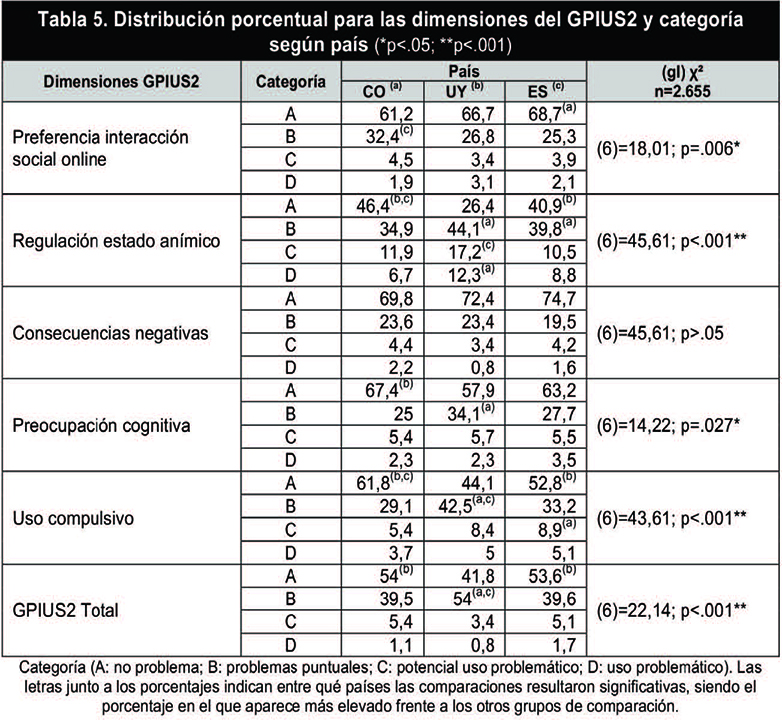

Differences in overall scores on GPIUS2 were only observed between Colombia and Uruguay (F2,5653=4.052; p=0.018; d=.20) (Colombia: M=2,14, SD= 1,05; Uruguay: M=2,34, SD=,94; Spain: M=2,20, SD=1,08). No gender- or age-based differences were found. By category, differences among countries were prevailingly found in isolated problems (Table 5).

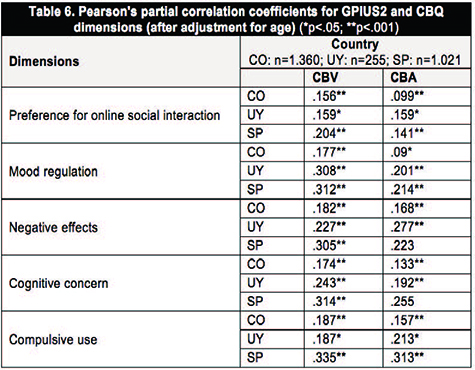

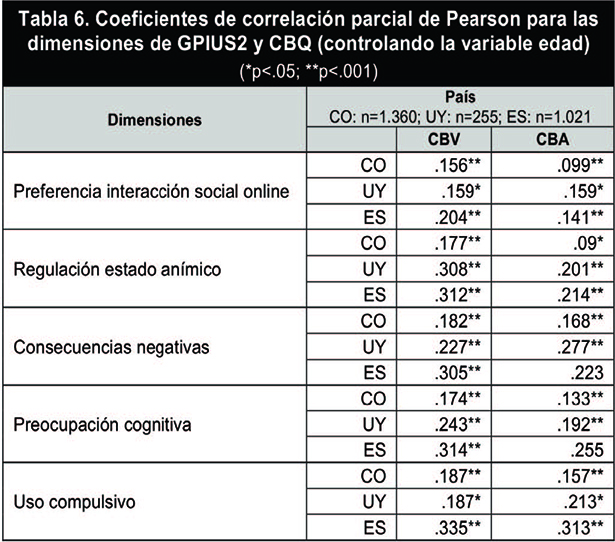

All GPIUS2 dimensions were positively and significantly correlated with overall scores for CBV and CBA, although differences –especially between Colombia and Uruguay– were low to moderate (Table 6).

Multiple linear regressions were performed to identify the GPIUS2 dimension that best predicted total scores for CBV and CBA. For Colombia, CBV was predicted by compulsive use (ß=.332 [.174-.490]; p<.001) and mood regulation (ß=.263 [.124-.403]; p<.001) [r2=.049]; whereas CBA was best predicted by negative effects (ß=.406 [.282-.530]; p<.001) [r2= .030]. For Uruguay, the best predictors were mood regulation (for CBV: ß= .680 [.382-.977]; p<.001; for CBA: ß=.303 [.060-.546]; p<.015) [r2=.103] and negative effects (for CBV: ß= .566 [.128-1.005]; p=.012) [r2=.124]; for CBA: ß=.716 [.358-1.075]; p<.001). In Spain, compulsive use (ß=.296 [.140-.452]; p<.001), mood regulation (ß=.286 [.167-.404]; p<.001) and negative effects (ß=.271 [.095-.448]; p=.003) [r2=.143] were predictors of CBV. CBA was predicted by compulsive use (ß=.377 [.308-.446]; p<.001) [r2=.100].

4. Discussion and conclusions

This study contributes to the understanding of the prevalence of cyberbullying and the problematic use of the Internet from a comparative approach. In addition, evidence of correlations between the two phenomena is provided.

Few cross-cultural studies have been conducted in relation to cyberbullying. Comparative studies of Spain and Latin America are scarce. The main objective of this study was to analyze and compare the characteristics of cyberbullying in Colombia, Uruguay, and Spain. The results obtained show that minor-CBV is more frequent in Spain than in Colombia, as is CBA in Spain with respect to Colombia and Uruguay. CBV was more frequent in Uruguay than in Colombia. These data do not confirm our first hypothesis that scores for cyberbullying would be higher in Colombia as reported in previous studies. This inconsistency may be due to respondents’ inability to recognize that their cyberbullying related behaviors are problematic or a form of cyber abuse. The fact that peer cyberbullying has become commonplace among youngsters may be the result of the social and cultural changes caused by the generalization of violence experienced in the last years (Castro & Varela, 2013). Thus, individuals tend to justify violence and adopt an individualistic perspective by which people have to solve their own problems (Cruz, 2014).

Comparative studies of the prevalence of cyberbullying in Europe and Latin America are hindered by methodological differences, yet the prevalence rates obtained in this study are consistent with those reported in previous studies conducted in Colombia (Herrera-López, Romera, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2017). However, lower prevalence rates have been documented in other Latin American studies (Castro & Varela, 2013; del-Río-Pérez, Bringue, Sádaba, & González, 2009), and the only study performed in Uruguay (Lozano & al., 2011). The prevalence rates reported in these studies range from 6% to 12%, which is consistent with the results obtained in this study. Also, these rates are similar to those obtained in other studies reporting a prevalence of severe cyberbullying ranging between 2% and 7% (Castro & Varela, 2013; Garaigordobil, 2011; García-Fernández, Romera-Félix, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2016; Herrera-López & al., 2017).

Regarding age, the frequency of cyberbullying has consistently been reported to decrease as age increases (Aranzales & al., 2014) peaking at 12-14 years (Tokunaga, 2010) and 14-15 years (Herrera-López & al., 2017; Zych & al., 2015). This is supported by the results of this study, as prevalence rates were higher in the 13-14 and 15-16 age groups. In relation to gender, the prevalence of CBV was higher among female students, as described in previous studies (Garaigordobil & Aliri, 2013). In contrast, gender-based differences were not observed in relation to CBA.

The role of cyberbystander has been scarcely studied (Jones, Mitchell, & Turner, 2015) and only in English-speaking countries. Nevertheless, the results of this study confirm our third hypothesis, which supports the results obtained for traditional bullying (Salmivalli, 1999; Salmivalli & al.,1996). Thus, prevalent sub-roles include defender of the victim and outsider. Data showed a homogeneous distribution across countries, except for the roles of supporter and reinforcer of the bully. The prevalence of these roles was considerably high in the 10-to-14-year range in the Colombian sample, where support to the victim was lower.

There is growing evidence that problematic Internet use among adolescents has a negative impact on their quality of life, as it causes changes in health habits (sleep, diet, physical activity, among others) and interferes with their family, social and academic life (Cerniglia, Zoratto, Cimino, Laviola, Ammaniti, & Adriani, 2017; Muñoz-Rivas, Fernández-González, & Gámez-Guadix, 2010). Epidemiologic studies have confirmed the clinical and social relevance of problematic Internet use. The meta-analysis conducted by Cheng and Li (2014) with data from 31 countries revealed prevalence rates ranging from 2,6% to 10,9% depending on the country. The prevalence of problematic Internet use documented in this study was lower than the ones reported in previous studies (<2%) but is consistent when potentially problematic Internet use is included in estimations (reaching 7%). The results obtained also confirm our fourth hypothesis: no significant differences exist among countries. However, no studies had been previously conducted to compare cyberbullying in Uruguay, Colombia and Spain.

Evidence on the correlation between problematic Internet use and cyberbullying is also limited. Our fifth hypothesis was also confirmed, as a positive correlation was observed between the GPIUS2 dimensions studied and CBV and CBA. The dimensions that seem to predict best cyberbullying were mood regulation (for CBV), negative effects (for CBA) and compulsive use (for CBV and CBA).

Finally, the results obtained showed that the instruments used have an adequate factorial validity and reliability for the Colombian and Uruguayan population. Validation was performed as described elsewhere (Gámez-Guadix & al., 2013; 2014), which confirms the null hypothesis.

The diversity of methods employed by which questionnaires and scales were homogenized allows for future comparative studies among different countries. This study may serve as a reference for future cross-cultural studies.

This study had some limitations. First, the results obtained were based on self-reports, with the potential risk of bias. This could be solved in the future by the administration of questionnaires to parents, teachers and peers. Another limitation is that the design of the study is cross-sectional, convenience sampling was performed, and the Uruguayan sample was small with regard to the Spanish and Colombian samples. In addition, the sample only includes students from urban areas with a low/middle socioeconomic status. Third, although evidence of the internal validity of the instruments was obtained for the Colombian and Uruguayan sample altogether, confirmatory factor analysis could not be performed for the Uruguayan sample due to the small size of the sample. Predictive validity and test-retest reliability could also have been assessed. In general terms, the external validity of the results obtained is limited. This study should be understood as a first approach to compare cyberbullying in these three countries. Future longitudinal studies should be conducted to replicate the results obtained in populations from other regions and countries.

In conclusion, this cross-cultural study provides empirical evidence on cyberbullying in two Latin American countries (Colombia and Uruguay) and Spain. Also, this study contributes to the body of knowledge on the prevalence of cyberbullying and identifies it as a problem that affects all cultures and regions. This is the first study to analyze the problematic Internet use from a comparative approach.

Funding Agency

This study received financial support from the International University of La Rioja (UNIR) under the Research Support Strategy 3 [2015-2017], Research Group “Analysis and prevention of cyberbullying” (CB-OUT), and the Research Support Strategy 4 [2017-2019], Research Group “Cyberpsychology: Psychosocial analysis of online interaction” (Cyberpsychology).

References

Aboujaoude, E., Savage, M.W., Starcevic, V., & Salame, W.O. (2015). Cyberbullying: Review of an old problem gone viral. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(1), 10-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.011

Aranzales, Y.D., Castaño, J.J., Figueroa, R.A., Jaramillo, S., Landazuri, J.N., Forero, R.A, … Valencia, K. (2014). Frecuencia de acoso y ciber-acoso, y sus formas de presentación en estudiantes de secundaria de colegios públicos de la ciudad de Manizales, 2013. Archivos de Medicina, 14(1), 65-82. https://goo.gl/LwfbPz

Asociacion Americana de Psiquiatría (Ed.) (2014). Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales (DSM-5). Barcelona: Elsevier.

Blinka L., Škarupová K., Ševcíková A., Wölfling K., Müller K.W., & Dreier, M. (2015). Excessive Internet use in European adolescents: What determines differences in severity? International Journal of Public Health, 60, 249-256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-014-0635-x

Byrne, B.M. (2006). Structural equation modeling with EQS. Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Calvete, E., Orue, I., Estevez, A., Villardon, L., & Padilla, P. (2010). Cyberbullying in adolescents: modalities and aggressors’ profile. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 1128-1135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.017

Caplan, S. (2010). Theory and measurement of generalized problematic Internet use: A two-step approach. Computers in Human Behaviour, 26(5), 1089-1097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.012

Castro, A., & Varela, J. (2013). Depredador escolar, bullying y cyberbullying, salud mental y violencia. Buenos Aires: Bonum.

Cerniglia, L. Zoratto, F., Cimino, S. Laviola, G., Ammaniti, M., & Adriani, W. (2017). Internet addiction in adolescence: Neurobiological, psychosocial and clinical issues. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 76(Part A), 174-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.024

Cheng, C., & Li, A.Y.L. (2014). Internet addiction prevalence and quality of (real) life: A meta-analysis of 31 nations across seven world regions. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17, 755-760. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0317

Cruz, E. (2014). Hipótesis sobre el matoneo escolar o bullying: A propósito del caso colombiano. Intersticios, 8(1), 149-156. https://goo.gl/X92MGw

Del-Rio-Perez, J., Bringue, X., Sadaba, C., & Gonzalez, D. (2009, mayo). Cyberbullying: Un análisis comparativo en estudiantes de argentina, Brasil, Chile, Colombia, México, Perú y Venezuela. V Congrés Internacional Comunicació i Realitat. Generació digital: oportunitats i riscos dels públics. La transformació dels usos comunicatius. Barcelona: Universidad Ramón Llull. https://goo.gl/oCFTQS

Estevez, A., Villardon, L., Calvete, E., Padilla, P., & Orue, I. (2010). Adolescentes víctimas de cyberbullying: Prevalencia y características. Psicología Conductual, 18(1), 73-89. https://goo.gl/FkPsTo

Gamez-Guadix, M., Orue, I., & Calvete, E. (2013). Evaluation of the cognitive-behavioral model of generalized and problematic Internet use in Spanish adolescents. Psycothema, 25(3), 299-306. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2012.274

Gamez-Guadix, M., Villa-George, F., & Calvete, E. (2012). Measurement and analysis of the cognitive-behavioral model of generalized problematic Internet use among Mexican adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 35(6), 1581-1591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.06.005

Gamez-Guadix, M., Villa-George, F., & Calvete, E. (2014). Psychometric properties of the Cyberbullying Questionnaire (CBQ) among Mexican adolescents. Violence and Victims, 29(2), 232-247. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00163R1

Garaigordobil, M. (2011). Prevalencia y consecuencias del cyberbullying: una revisión. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 11(2), 233-254. https://goo.gl/3w3Ge7

Garaigordobil, M., & Aliri, J. (2013). Ciberacoso (cyberbullying) en el País Vasco: Diferencias de sexo en víctimas, agresores y observadores. Psicología Conductual, 21(3), 461-474. https://goo.gl/8hJScy

Garcia-Fernandez, C.M., Romera-Felix, E.M., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2016). Relaciones entre el bullying y el cyberbullying: prevalencia y coocurrencia. Pensamiento Psicológico, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.11144/Javerianacali.PPSI14-1.rbcp

Garcia-Maldonado, G., Joffre, V., Martinez, G., & Llanes, A. (2011). Cyberbullying: forma virtual de intimidación escolar. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 40(1), 115-130. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-7450(14)60108-6

Herrera-Lopez, M., Romera. E., & Ortega-Ruiz. R. (2017). Bullying y cyberbullying en Colombia: coocurrencia en adolescentes escolarizados. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 49(3), 163-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rlp.2016.08.001

Hu, L., & Bentler, P.M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jones, L.M., Mitchell, K.J., & Turner, H.A. (2015). Victim reports of bystander reactions to in-person and online peer harassment: A national survey of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(12), 2308-2320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0342-9

Kowalski, R.M., Limber, S.P., & Agatston, P.W. (2012). Cyberbullying: Bullying in the digital age. Second Edition. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

Laplacette, J.A., Becher, C., Fernandez, S., Gomez, L., Lanzillotti, A., & Lara, L. (2011). Cyberbullying en la adolescencia: análisis de un fenómeno tan virtual como real. III Congreso Internacional de Investigación y Práctica Profesional en Psicología. XVIII Jornadas de Investigación Séptimo Encuentro de Investigadores en Psicología del MERCOSUR. Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina. https://goo.gl/LjWd9G

Lozano, F., Gimenez, A., Cabrera, J.M., Fernandez, A., Lewy, E., Salas, F., Cid, A., Hackembruch, C., & Olivera, V. (2011). Violencia: Caracterización de la población adolescente de instituciones educativas de la región oeste de Montevideo-Uruguay en relación a la situación de violencia en que viven. Revista Biomédica, Medicina Familiar y Comunitaria, 6(1), 18-40. https://goo.gl/Mea5Mc

Lucio, L.A., & Gonzalez, J.H. (2012). El teléfono móvil como instrumento de violencia entre estudiantes de bachillerato en México. IV Congreso Internacional Latina de Comunicación Social. Universidad de la Laguna, Tenerife, España. https://goo.gl/yeu2fY

Muñoz-Rivas, M.J., Fernandez-Gonzalez, L., & Gamez-Guadix, M. (2010). Analysis of the indicators of pathological Internet use in Spanish university students. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13(2), 697-707 https://doi.org/10.1017/S1138741600002365

Mura, G., & Diamantini, D. (2013). Cyberbullying among Colombian students: An exploratory investigation. European Journal of investigation in health, Psychology and Education, 3(3), 249-256. https://goo.gl/aYGvqc

Redondo, J., & Luzardo, M. (2016, junio). Cyberbullying y género en una muestra de adolescentes colombianos. In J.L. Castejon-Costa (Coord.), Psicología y educación: Presente y futuro. Alicante: VIII Congreso de Psicología y Educación (CIPE2016), pp. 1847-1857.

Redondo, J., Luzardo, M., Garcia-Lizarazo, K.L., & Ingles, C.J. (2017). Impacto psicológico del cyberbullying en estudiantes universitarios: un estudio exploratorio. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Sociales, 8(2), 458-478. https://doi.org/10.21501/22161201.2061

Romera, E., Herrera-Lopez, M., Casas, J., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Gomez-Ortiz, O. (2017). Multidimensional social competence, motivation, and cyberbullying: A cultural approach with Colombian and Spanish Adolescents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(8), 1183-1197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022116687854

Salmivalli, C. (1999). Participant role approach to school bullying: Implications for interventions. Journal of Adolescence, 22(4), 453-459. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1999.0239

Salmivalli, C., Karna, A., & Poskiparta, E. (2011). Counteracting bullying in Finland: The KiVa program and its effects on different forms of being bullied. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(5), 405-411. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025411407457

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Bjorkqvist, K., Osterman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:1%3C1::AID-AB1%3E3.0.CO;2-T

Tokunaga, R.S. (2010). Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on Cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(3), 277-287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.014

Varela, J., Perez, J, C., Schwaderer, H., Astudillo, J., & Lecannelier, F. (2014). Caracterización de cyberbullying en el gran Santiago de Chile, en 2010. Revista Quadrimestral da Associação Brasileira de Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 18(2), 347-354. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-3539/2014/0182794

Zych, I., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Del Rey, R. (2015). Scientific research on bullying and cyberbullying: Where have we been and where are we going. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 24, 188-198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.015

Zych, I., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Marin-Lopez, I. (2016). Cyberbullying: A systematic review of research, its prevalence and assessment issues in Spanish studies. Psicología Educativa, 22(1), 5-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pse.2016.03.002

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El objetivo de este estudio transcultural ha sido analizar y comparar las puntuaciones de cibervictimización y ciberagresión, y el uso problemático de Internet en adolescentes de España, Colombia y Uruguay, ya que pese a las semejanzas culturales existentes entre el contexto latinoamericano y español son escasos los estudios empíricos que los han comparado previamente. La muestra estuvo formada por 2.653 participantes de 10 a 18 años. Se recogieron datos a través del cuestionario de ciberacoso y de la versión en castellano del «Revised generalized and problematic Internet use scale». Los resultados ponen de manifiesto una mayor prevalencia de conductas de ciberacoso leve en España entre los 10-14 años. En los tres países, destacan dos roles de ciberobservador: defensor de la víctima y no comprometido ante la agresión, aunque con más perfiles de apoyo al agresor en Colombia. No se observan diferencias en un uso problemático de Internet entre los tres países. Se proporcionan evidencias sobre la relación de la cibervictimización y ciberagresión con el uso problemático de Internet. Las dimensiones de uso compulsivo y regulación del estado anímico son las que mejor predicen el ciberacoso. Los resultados son discutidos con relación a la posible normalización de la violencia y su falta de reconocimiento como tal.

1. Introducción

En las últimas décadas, los avances en la tecnología y las herramientas que ofrece Internet han transformado la forma de acceder a la información y, consecuentemente, de expresarse, comunicarse e interactuar con otros. Sin embargo, a pesar de las ventajas asociadas, la sociedad digital también entraña riesgos, de este modo muchos de los problemas psicosociales que existen en la sociedad offline (por ejemplo, la violencia entre iguales o en el mundo de la pareja) han encontrado su equivalente en Internet, y al mismo tiempo han aparecido nuevas problemáticas asociadas a un inadecuado uso de estas tecnologías y/o dispositivos digitales. Todo ello comienza a ser abordado en el marco de la «ciberpsicología», una rama que estudia la relación entre el ser humano y la utilización de la tecnología en la vida cotidiana.

Uno de estos problemas es el ciberacoso, definido como cualquier comportamiento de un individuo o grupo realizado con la intención de causar daño o incomodidad a otros mediante la difusión repetida de mensajes hostiles o agresivos a través de medios digitales, particularmente teléfonos móviles o Internet (Tokunaga, 2010). Las conductas más habituales son denigración (insultos y humillaciones), mensajes o llamadas ofensivas y amenazantes, suplantación de identidad, exclusión y revelación (Kowalski, Limber, & Agatston, 2012). Las experiencias de ciberacoso pueden ocurrir en cualquier momento del día y en cualquier contexto lo que incide en la incertidumbre que vive el ciberacosado y en la gran difusión de la intimidación. Añadir que la identidad del acosador puede o no ser conocida (Tokunaga, 2010). Este desequilibro de poder tiene un grave impacto socioemocional en la víctima, quién puede ver afectado, entre otros, el desarrollo de su personalidad, autoestima, habilidades sociales y capacidad de resolución de conflictos (Zych, Ortega, & De Rey, 2015). En esta realidad, un rol que día a día cobra más importancia es el de ciberobservador, ya que sobre él recaen distintas iniciativas de intervención (véase como ejemplo el programa de prevención de la violencia, KIVA; Salmivalli, Kärnä, & Poskiparta, 2011). Este rol ha sido abordado con profundidad para el acoso tradicional por Salmivalli (1999), quién reconoció la importancia de la actuación de los observadores en la prevención o en la perpetuación de las agresiones. Para reforzar esta idea, estableció cinco sub-roles: ayudante y reforzador del agresor, no comprometido, províctima y defensor de la víctima (siendo este último el más habitual). Por las repercusiones que conlleva, conocer y saber identificar estos sub-roles es de gran importancia, sin embargo, no es una práctica habitual en el contexto de investigación.

El ciberacoso es un problema social cuya prevalencia y estabilidad, independientemente del país o cultura, se ha incrementado considerablemente en los últimos años (Aboujaoude, Savage, Starcevic, & Salame, 2015). Estados Unidos y Europa cuentan con gran cantidad de estudios, no así Latinoamérica, donde además se aprecia gran variedad metodológica. Datos actuales en España apuntan hacia una prevalencia media de 26,65% (desviación típica media del 23,23%) para la cibervictimización (CBV) y de 24,64% (desviación típica media del 24,35%) para la ciberagresión (CBA) (Zych, Ortega-Ruiz, & Marin-López, 2016). Si se atiende a contextos latinoamericanos, las prevalencias ascienden de forma notable, por ejemplo, en Colombia entre un 30% (Redondo & Luzardo, 2016; Redondo, Luzardo, García-Lizarazo, & Ingles, 2017) y un 60% (Mura & Diamantini, 2013). En Argentina o México la prevalencia ronda también el 49% (Laplacette, Becher, Fernández, Gómez, Lanzillotti, & Lara, 2011; Lucio & González, 2012). Como contraste, otras investigaciones señalan que en México (Castro & Varela, 2013; García-Maldonado, Joffre, Martínez, & Llanes, 2011), Uruguay (Lozano & al., 2011) o Chile (Varela, Pérez, Schwaderer, Astudillo, & Lecannelier, 2014) la CBV no superaría el 15%. Sobre estas diferencias transculturales, cabe decir, sin embargo, que pese al idioma y base cultural común que hace relevante la comparación entre países latinoamericanos y España, las investigaciones son aún insuficientes. Una excepción es el reciente estudio de Romera, Herrera-López, Casas, Ortega-Ruiz y Gómez-Ortiz (2017) donde se examinó la influencia de variables interpersonales (autoeficacia social percibida y motivación social) en situaciones de ciberacoso, estableciendo un modelo homogéneo entre la población española y colombiana.

En relación con el uso de Internet, es necesario puntualizar que el DSM-V (Asociación Americana de Psiquiatría, 2014) no incluye la adicción a Internet ni su uso intensivo como trastorno adictivo ni como «adicción conductual», pero eso no significa que este no sea negativo, y por ello, uno de los términos más aceptados en la actualidad es «uso problemático de Internet» (Caplan, 2010). Desde este enfoque se hace hincapié en las posibles disfuncionalidades e interferencias con la vida familiar, social y académica que puede suponer un patrón de consumo determinado. Estudios realizados en España (Gámez-Guadix, Orue, & Calvete, 2013), en México (Gámez-Guadix, Villa-George, & Calvete, 2012) y en el contexto europeo (Blinka, Škarupová, Ševcíková, Wölfling, Müller, & Dreier, 2015) respaldan un modelo cognitivo-conductual sobre las características asociadas a una práctica inadecuada, entre las que se encuentran, por ejemplo, una preferencia por la interacción social online o un uso compulsivo. No obstante, no ha sido común establecer relaciones entre este constructo y los roles implicados en el ciberacoso, aún menos compararlo entre países.

Por esta razón, en este estudio el objetivo principal es analizar y comparar las puntuaciones de CBV y CBA entre España, Colombia y Uruguay. Adicionalmente, otros objetivos son: 1) analizar la estructura factorial de los instrumentos utilizados para las muestras de Colombia y Uruguay; 2) describir y comparar el perfil de ciberobservador en los tres países; 3) analizar y comparar las características asociadas a un uso problemático de Internet en los tres países; 4) examinar la relación entre un uso problemático de Internet y la prevalencia de ciberacoso.

Atendiendo a resultados de investigaciones previas las hipótesis son: 1) las mayores puntuaciones de CBV y CBA corresponderán al contexto colombiano; 2) la estructura factorial de las herramientas utilizadas será adecuada en la muestra colombiana y uruguaya; 3) el sub-rol de ciberobservador más frecuente será el defensor de la víctima, distribuyéndose homogéneamente entre los tres países; 4) no habrá diferencias en el uso problemático de Internet entre los tres países; 5) habrá una correlación positiva entre las dimensiones del uso problemático de Internet y CBV y CBA.

2. Material y métodos

2.1. Muestra

Se llevó a cabo un estudio transversal, descriptivo y analítico entre marzo de 2016 y julio de 2017. La muestra estuvo formada por 2.653 participantes de 10 a 18 años (M=14,48; DT=1,66) procedentes de Colombia (51,3%), Uruguay (9,9%) y España (38,8%), siendo el 50,8% hombres (N=1.350) y el 49,1% mujeres (N=1.303). Se realizó un muestreo no probabilístico de tipo incidental. La elección se realizó siguiendo un criterio geográfico intentando conseguir centros del norte-sur y este-oeste de cada país, lo que resultó en un total de 12 centros. Todos fueron seleccionados en núcleos urbanos y zonas de nivel económico medio-bajo. Concretamente, la muestra colombiana fue obtenida de cinco centros públicos y tres privados ubicados en Belén, Neiva, Bogotá y Cali (n= 1.363; edad media=14,82; DT=1,68). La muestra de Uruguay provino de un centro privado de Melo (n=260; edad media 14,48; DT=1.72). La muestra española se obtuvo de dos centros públicos de Valencia y Asturias y un centro concertado de Sevilla (n=1.030; edad media=14,01; DT=1,49). La distribución de participantes por edad y género puede observarse en la Tabla 1.

2.2. Instrumentos de evaluación

Se recabaron datos sobre las variables sociodemográficas: sexo (hombre; mujer), edad (recodificada en cuatro grupos: 10-12; 13-14; 15-16 y 17-18 años) y país (Colombia; Uruguay; España).

«Cuestionario de Ciberacoso» (CBQ; Calvete, Orue, Estévez, Villardón, & Padilla, 2010; Estévez, Villardón, Calvete, Padilla, & Orue, 2010; Gámez-Guadix, Villa-George, & Calvete, 2014). Incluye una escala de CBA con 17 ítems y una escala de CBV con 11 ítems que recogen las conductas asociadas al ciberacoso. Las respuestas se indican en escala Likert de 4 puntos (0=nunca; 1=una o dos veces; 2=tres o cuatro veces; 3=cinco o más). Mediante la baremación de las puntuaciones obtenidas se han establecido 3 perfiles: sin problema (puntuación total=0-1); cibervíctima/ciberagresor leve (puntuaciones iguales o superiores al percentil 85 e inferiores del 95) y, cibervíctima/ciberagresor grave (puntuaciones iguales o superiores al percentil 95). El estudio de validación con muestra española presenta adecuados indicadores de fiabilidad y validez. Este estudio presenta para la dimensión de CBV un a=.86 y para CBA un a=.82. La versión colombiana y uruguaya se adaptó lingüísticamente (por ejemplo, sustituyendo móvil por celular, ordenador por computadora, agresor por matón, acoso por matoneo, etc.).

Adicionalmente, se preguntó a los participantes por su rol como ciberobservador, estableciendo las dimensiones descritas para el acoso tradicional (Salmivalli, 1999; Salmivalli, Lagerspetz, Bjorkqvist, Osterman, & al., 1996): ayudante del agresor/a (no inicia la agresión nunca, pero a veces participa apoyando al agresor/a); reforzador/a del agresor/a (simpatiza con el agresor/a, pero nunca participa directamente); no comprometido/a (se mantiene ajeno); províctima (a favor de la víctima, pero no hace nada por evitar la agresión) y, defensor/a (suele defender activamente a la víctima).

La versión española de la «Revised Generalized and Problematic Internet Use Scale» (GPIUS2, Gámez-Guadix & al., 2013) evalúa el uso problemático de Internet mediante 15 ítems distribuidos en 5 subescalas: 1) preferencia por la interacción social online; 2) regulación del estado anímico a través de Internet; 3) consecuencias negativas; 4) preocupación cognitiva; 5) uso compulsivo. Las respuestas se indican en escala Likert de 6 puntos (1=totalmente en desacuerdo; 6=totalmente de acuerdo). Las puntuaciones fueron codificadas en cuatro categorías: a) no problema (entre =1<2); b) problemas puntuales (entre =2<4); c) potencial uso problemático (entre =4<5); d) uso problemático (entre =5=6). La escala presenta adecuados índices de fiabilidad y validez para la muestra española. En este estudio el valor alfa fue a=.93. Nuevamente, las versiones colombiana y uruguaya se adaptaron lingüísticamente.

2.3. Procedimiento

El primer contacto con los centros se realizó por correo electrónico. Tras una respuesta afirmativa para colaborar, hubo una comunicación telefónica y se facilitó la documentación necesaria para participar en el estudio. La batería de cuestionarios fue aplicada en las aulas por un colaborador y por personal de los propios centros (normalmente el tutor de curso o el responsable de orientación escolar). Se hizo hincapié en que se debía contestar verazmente, no detenerse mucho tiempo en las preguntas, y anotar cualquier duda en la última hoja. El tiempo para cumplimentar la batería osciló entre 25 y 40 minutos. La colaboración fue voluntaria, anónima y desinteresada. El estudio se llevó a cabo con la autorización tácita de todos los participantes en la investigación al rellenar el cuestionario, y con el permiso del centro y los progenitores. Este proyecto tiene el refrendo del Comité de Ética de la Investigación del Principado de Asturias (Ref 11/15).

3. Análisis y resultados

Previo a los análisis, para el CBQ se realizaron modelos de ecuaciones estructurales usando estimaciones ponderadas de mínimos cuadrados con la muestra colombiana y uruguaya conjuntamente. En el caso del GPIUS2 se llevó a cabo un análisis factorial confirmatorio mediante el método robusto de máxima verosimilitud (incluyendo el índice Satorra-Bentler scaled ?2). Además, para estudiar la adecuación de los modelos estimados se utilizó el índice no normativo de ajuste (NNFI), el índice de ajuste comparativo (CFI) y el error cuadrático medio de aproximación (RMSEA). Para el NNFI y del CFI, los valores superiores a .90 indican un ajuste aceptable y los superiores a .95 un buen ajuste. En el caso del RMSEA un valor cercano a .05 revela un excelente ajuste y entre .05 y .08 un ajuste aceptable (Byrne, 2006; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

El resto de análisis realizados fueron: 1) comprobación de la distribución normal de la muestra (estadístico de Shapiro-Wilks) y la homogeneidad de las varianzas (prueba de Levene); 2) análisis de frecuencias y de medidas de tendencia central y dispersión de la medida; 3) cálculo de las puntuaciones tipificadas para las variables donde se establecieron relaciones; 4) estadístico ?2 para el contraste de proporciones con comparaciones post-hoc; 5) correlaciones parciales controlando por edad; 6) análisis de la varianza con comparaciones post-hoc de Bonferroni; 7) regresiones lineales múltiples por «pasos sucesivos» usando la probabilidad de F para un valor de entrada de .15 y de salida de .20 para analizar qué dimensión del GPIUS2 predecía mejor las puntuaciones de CBV y CBA en cada país. En los casos donde se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas se calculó la d de Cohen para proporcionar una estimación del tamaño del efecto de la diferencia. Se consideró significativo un valor de p<.05. Los análisis estadísticos se llevaron a cabo mediante SPSS, 23.0 y Lisrel 8.5.

3.1. Validez y fiabilidad de los cuestionarios CBQ y GPIUS2 en las muestras colombiana y uruguaya

El modelo hipotetizado ha consistido en dos factores correlacionados, uno para CBA y otro para CBV (tal y como realizaron Gámez-Guadix & al., 2014). La solución obtenida fue satisfactoria con índices de ajuste adecuados: ?2(234, N=1.620)=341; p<.001; RMSEA=.059 (IC 95%: .053-.066); NNFI=.98; CFI=.98. La dimensión de CBV obtuvo un alfa de Cronbach de .82 y la de CBA de .86.

En el caso del GPIUS2, se ha hipotetizado el mismo modelo de cinco componentes expuesto anteriormente (Caplan, 2010; Gámez-Guadix & al., 2013). Se han obtenido resultados aceptables: S-B ?2(84)=401; p<.001; RMSEA=.070 (IC 95%: .063-.079; NNFI=.98; CFI=.98). El alfa de Cronbach fue de .90.

3.2. Prevalencia de cibervictimización y ciberagresión

La Tabla 2 muestra las diferencias entre países en la puntuación total en CBV y CBA.

En la Tabla 3 se muestran, según país y edad, las diferencias en la distribución porcentual de cada nivel de gravedad de ciberacoso. Colombia tuvo mayor porcentaje de participantes que no mostraron problemas. En cuanto a problemas leves, España presentó más casos (especialmente entre los 10-14 años). En los casos de mayor gravedad no hubo diferencias significativas entre países.

En relación con las variables sexo y edad, en Colombia se apreciaron diferencias en CBV-Grave (en 10-12 años, hombres: 1,3%; mujeres: 11,7%), ?²(2, N=8)=6,67; p<.05), y CBV-Leve (en 15-16 años, hombres: 4,3%; mujeres: 16,2%), ?²(2, N=37)=17,82; p<.001), con mayor porcentaje de mujeres. Estas diferencias también se observaron en España en CBV-Leve pero en este caso hubo un mayor porcentaje de hombres implicados (en 13-14 años, hombres: 25%; mujeres: 7%), ?²(2, N=28)=18,13; p<.001. No existieron diferencias según estas variables en CBA.

3.3. Perfil de ciberobservador

Según los porcentajes totales expuestos en la Tabla 4, la mayor parte de la muestra se posicionó en el sub-rol de defensor de la víctima, seguido del no comprometido. Se hallaron diferencias en dicha distribución asociadas a la variable sexo, siendo el porcentaje de hombres (34,9%) mayor que el de mujeres (31,2%) en el sub-rol no comprometido, ?²(1, N=856)=4,21; p=.04, pero con un patrón contrario en defensor de la víctima (hombres: 38,2%; mujeres: 44,3%; ?²(1, N=1.067)=3,96; p=.047).

Solo en Colombia se observaron diferencias entre los perfiles según la edad, ?²(12, N=1.339)=42,21; p<.001, siendo mayor en el sub-rol de ayudante del agresor el porcentaje de participantes de 10-12 años que de 15-18 años.

Si se atiende al contraste entre países, se constatan porcentajes significativamente mayores en Colombia con respecto a España en los sub-roles: ayudante, ?²(2, N=151)=167,57; p<.001; reforzador, ?²(2, N=123)=65,02; p<.001 y no comprometido, ?²(2, N=857)=275,26; p<.001. Por el contrario, España tuvo mayor porcentaje de participantes que Colombia en províctimas, ?²(2, N=392)=86,61; p<.001, y defensores, ?²(2, N= 1.069)=258,07; p<.001.

3.4. Uso problemático de Internet

Al comparar la puntuación total del GPIUS2 se encontraron diferencias entre Colombia y Uruguay (F2,2653=4.052; p=0.018; d=.20) (Colombia: M=2,14, DT= 1,05; Uruguay: M=2,34, DT=,94; España: M=2,20, DT=1,08). No hubo diferencias asociadas a las variables sexo y edad. Al separar por categorías, las diferencias entre países se obtuvieron principalmente en los problemas puntuales (Tabla 5).

Por otra parte, todas las dimensiones del GPIUS2 correlacionaron positiva y significativamente con las puntuales globales de CBV y CBA, aunque de manera baja-moderada, especialmente en Colombia y Uruguay (Tabla 6).

Por último, se realizaron regresiones lineales múltiples con el fin de predecir qué dimensión del GPIUS2 en cada país predecía mejor las puntuaciones totales de CBV y CBA. Para Colombia, la CBV fue predicha por el uso compulsivo (ß=.332 [.174-.490]; p<.001) y la regulación del estado anímico (ß=.263 [.124-.403]; p<.001) [r2=.049]; mientras que la CBA lo fue por las consecuencias negativas (ß=.406 [.282-.530]; p<.001) [r2=.030]. Para Uruguay, las dimensiones que mejor predijeron fueron regulación del estado anímico (en CBV: ß=.680 [.382-.977]; p<.001; en CBA: ß=.303 [.060-.546]; p<.015) [r2=.103] y consecuencias negativas (en CBV: ß=.566 [.128-1.005]; p=.012) [r2=.124]; en CBA: ß=.716 [.358-1.075]; p<.001). En España, la CBV fue predicha por el uso compulsivo (ß=.296 [.140-.452]; p<.001), la regulación del estado anímico (ß=.286 [.167-.404]; p<.001) y las consecuencias negativas (ß=.271 [.095-.448]; p=.003) [r2=.143]. La CBA se predijo por el uso compulsivo (ß=.377 [.308-.446]; p<.001) [r2=.100].

4. Discusión y conclusiones

El presente estudio contribuye al conocimiento de la prevalencia del ciberacoso y el uso problemático de Internet desde una perspectiva comparada, además de proveer evidencias de la relación entre ambas problemáticas.

Son pocos los estudios transculturales sobre esta temática y menos aun los que incluyen los contextos latinoamericano y español. Por lo que el objetivo principal ha sido analizar y comparar esta situación en Colombia, Uruguay y España. Los resultados hallados evidencian que España presenta más situaciones de CBV-Leve que Colombia, así como de CBA respecto a Colombia y Uruguay. Uruguay revela más casos de CBV-Grave que Colombia. Estos datos no permiten corroborar la primera hipótesis según la cual, y de acuerdo con estudios previos, Colombia presentaría mayores puntuaciones en ciberacoso. Esta posible discrepancia podría deberse a la falta de reconocimiento de las conductas asociadas al ciberacoso como problemáticas o incluso como formas de ciberviolencia. Esta normalización en la relación entre iguales sería resultado de los cambios sociales y culturales producidos por la violencia vivida en los últimos años (Castro & Varela, 2013) en los que se tiende hacia su justificación y hacia una perspectiva individualizada en la que cada uno debe arreglar sus problemas (Cruz, 2014).

La variabilidad metodológica existente entre estudios europeos y latinoamericanos dificulta la comparación de las prevalencias, cabe señalar que la obtenida en este estudio se asemeja a otros resultados previos obtenidos en Colombia (Herrera-López, Romera, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2017), pero sobrepasa la de estudios llevados a cabo exclusivamente en Latinoamérica (Castro & Varela, 2013; del-Rio-Pérez, Bringue, Sádaba, & González, 2009) y al único estudio que ofrece datos de Uruguay (Lozano & al., 2011). Los mismos señalan entre un 6% y 12% de situaciones de ciberacoso, lo que hace estos resultados convergentes con los encontrados por los autores, y a su vez consistentes con estudios que estipulan una prevalencia de ciberacoso severo de entre un 2% y 7% (Castro & Varela, 2013; Garaigordobil, 2011; García-Fernández, Romera-Félix, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2016; Herrera-López & al., 2017).

En relación con la edad, la tendencia en anteriores investigaciones sugiere que a medida que ésta aumenta, disminuye la frecuencia de ciberacoso (Aranzales & al., 2014), situando el pico máximo entre los 12-14 años (Tokunaga, 2010) y los 14-15 años (Herrera-López & al., 2017; Zych & al., 2015). Los resultados en este estudio apoyan esta evidencia, ya que las horquillas de 13-14 y 15-16 en los tres países evaluados presentaron la mayor prevalencia del problema. Con relación a la variable sexo, las chicas presentaron mayor prevalencia de CBV, tal y como se describe en la literatura (Garaigordobil & Aliri, 2013), aunque no hubo diferencias para CBA.

Los trabajos que han abordado el análisis del rol de ciberobservador son escasos (Jones, Mitchell, & Turner, 2015) y se han realizado únicamente en el contexto anglosajón. No obstante, los resultados de este estudio confirman la tercera hipótesis, corroborando los resultados para acoso tradicional (Salmivalli, 1999; Salmivalli & al.,1996), en los que prevalecen los sub-roles de defensor de la víctima y no comprometido. Los datos muestran una distribución homogénea entre los tres países, salvo en las fórmulas que apoyan al agresor (ayudante y reforzador), especialmente altas para la muestra colombiana en el rango de 10-14 años y donde el apoyo a la víctima es menor.

Por otro lado, cada vez hay más evidencias sobre cómo el uso problemático de Internet que hacen algunos adolescentes tiene un impacto negativo en su calidad de vida, por ejemplo, con cambios en los hábitos de salud (sueño, alimentación, actividad física, etc.) e interferencia en la vida familiar, social y académica (Cerniglia, Zoratto, Cimino, Laviola, Ammaniti, & Adriani, 2017; Muñoz-Rivas, Fernández-González, & Gámez-Guadix, 2010). Estudios epidemiológicos evidencian la relevancia clínica y social de esta problemática. En este sentido, el metaanálisis realizado por Cheng y Li (2014) con datos de 31 países, encontró prevalencias que oscilaron entre el 2,6% y el 10,9% dependiendo del país. En este estudio, los datos de un uso problemático son inferiores a los constatados en la literatura (no llegan el 2%), pero son convergentes si se suma a estos el potencial uso problemático (alcanzando un 7%). Tal y como se sugirió en la cuarta hipótesis, no se encontraron diferencias entre países. Sin embargo, no existen resultados previos contrastando estos países.

También son escasos los estudios que relacionan un uso problemático de Internet con ciberacoso. En los datos obtenidos, y confirmando la quinta hipótesis, se han observado correlaciones positivas entre las dimensiones evaluadas en el GPIUS2 y las conductas de CBV y CBA. Además, las dimensiones que, de forma general, parecen predecir mejor el ciberacoso han sido la regulación del estado de ánimo (para CBV), las consecuencias negativas (para CBA) y el uso compulsivo (para ambas).

Asimismo, se ha comprobado una adecuada validez factorial y fiabilidad para la muestra colombiana y uruguaya de las herramientas utilizadas. Los procesos de validación seguidos fueron los indicados en los trabajos originales (Gámez-Guadix & al., 2013; 2014), confirmando también la hipótesis inicial de investigación.

Debido a la diversidad metodológica, este estudio permite como aplicación práctica realizar comparaciones entre diferentes contextos culturales al homogenizar cuestionarios y baremos, pudiendo ser un ejemplo para otros estudios transculturales.

No obstante, cuenta asimismo con una serie de limitaciones. En primer lugar, los resultados se basan en autoinformes, siendo posibles los sesgos de respuesta. Ello podría mejorarse triangulando medidas complementarias (padres, profesores e iguales). En segundo lugar, el estudio es transversal y el muestreo ha sido incidental, siendo la muestra uruguaya baja en relación con Colombia y España. Respecto a otras características de la muestra, se cuenta únicamente con una clase social media-baja de contextos urbanos. En tercer lugar, aunque se han proporcionado evidencias de validez interna de los instrumentos para la muestra colombiana y uruguaya conjuntamente, debido al bajo n muestral de Uruguay no fue posible realizar el análisis factorial confirmatorio. Hubiera sido deseable añadir aspectos de validez predictiva y de test-retest. De forma general, se debe ser cauteloso al extrapolar estos resultados, entendiéndose como una primera aproximación al análisis comparado entre estos países. Estudios futuros deberían replicar estos hallazgos con muestras adicionales en otras regiones y países y plantear estudios longitudinales.

En conclusión, cabe destacar la aportación de evidencia empírica sobre el ciberacoso en un contexto transcultural entre dos países latinoamericanos (Colombia y Uruguay) y España. Estos resultados suman una contribución a los estudios sobre prevalencia del ciberacoso y su constatación como problema, con independencia de la cultura o región geográfica, y contribuyen al conocimiento del uso problemático de Internet desde una perspectiva comparada y única hasta el momento entre estos países.

Apoyos

Este estudio ha sido financiado por la Universidad Internacional de La Rioja (UNIR), dentro del Plan Propio de Investigación 3 [2015-2017], Grupo de Investigación «Análisis y prevención del ciberacoso» (CB-OUT) y del Plan de investigación 4 [2017-2019], Grupo de Investigación «Ciberpsicología: análisis psicosocial de los contextos online» (Cyberpsychology).

Referencias

Aboujaoude, E., Savage, M.W., Starcevic, V., & Salame, W.O. (2015). Cyberbullying: Review of an old problem gone viral. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(1), 10-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.011

Aranzales, Y.D., Castaño, J.J., Figueroa, R.A., Jaramillo, S., Landazuri, J.N., Forero, R.A, … Valencia, K. (2014). Frecuencia de acoso y ciber-acoso, y sus formas de presentación en estudiantes de secundaria de colegios públicos de la ciudad de Manizales, 2013. Archivos de Medicina, 14(1), 65-82. https://goo.gl/LwfbPz

Asociacion Americana de Psiquiatría (Ed.) (2014). Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales (DSM-5). Barcelona: Elsevier.

Blinka L., Škarupová K., Ševcíková A., Wölfling K., Müller K.W., & Dreier, M. (2015). Excessive Internet use in European adolescents: What determines differences in severity? International Journal of Public Health, 60, 249-256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-014-0635-x

Byrne, B.M. (2006). Structural equation modeling with EQS. Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Calvete, E., Orue, I., Estevez, A., Villardon, L., & Padilla, P. (2010). Cyberbullying in adolescents: modalities and aggressors’ profile. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 1128-1135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.017

Caplan, S. (2010). Theory and measurement of generalized problematic Internet use: A two-step approach. Computers in Human Behaviour, 26(5), 1089-1097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.012

Castro, A., & Varela, J. (2013). Depredador escolar, bullying y cyberbullying, salud mental y violencia. Buenos Aires: Bonum.

Cerniglia, L. Zoratto, F., Cimino, S. Laviola, G., Ammaniti, M., & Adriani, W. (2017). Internet addiction in adolescence: Neurobiological, psychosocial and clinical issues. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 76(Part A), 174-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.024

Cheng, C., & Li, A.Y.L. (2014). Internet addiction prevalence and quality of (real) life: A meta-analysis of 31 nations across seven world regions. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17, 755-760. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0317

Cruz, E. (2014). Hipótesis sobre el matoneo escolar o bullying: A propósito del caso colombiano. Intersticios, 8(1), 149-156. https://goo.gl/X92MGw

Del-Rio-Perez, J., Bringue, X., Sadaba, C., & Gonzalez, D. (2009, mayo). Cyberbullying: Un análisis comparativo en estudiantes de argentina, Brasil, Chile, Colombia, México, Perú y Venezuela. V Congrés Internacional Comunicació i Realitat. Generació digital: oportunitats i riscos dels públics. La transformació dels usos comunicatius. Barcelona: Universidad Ramón Llull. https://goo.gl/oCFTQS

Estevez, A., Villardon, L., Calvete, E., Padilla, P., & Orue, I. (2010). Adolescentes víctimas de cyberbullying: Prevalencia y características. Psicología Conductual, 18(1), 73-89. https://goo.gl/FkPsTo

Gamez-Guadix, M., Orue, I., & Calvete, E. (2013). Evaluation of the cognitive-behavioral model of generalized and problematic Internet use in Spanish adolescents. Psycothema, 25(3), 299-306. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2012.274

Gamez-Guadix, M., Villa-George, F., & Calvete, E. (2012). Measurement and analysis of the cognitive-behavioral model of generalized problematic Internet use among Mexican adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 35(6), 1581-1591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.06.005

Gamez-Guadix, M., Villa-George, F., & Calvete, E. (2014). Psychometric properties of the Cyberbullying Questionnaire (CBQ) among Mexican adolescents. Violence and Victims, 29(2), 232-247. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-12-00163R1

Garaigordobil, M. (2011). Prevalencia y consecuencias del cyberbullying: una revisión. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 11(2), 233-254. https://goo.gl/3w3Ge7

Garaigordobil, M., & Aliri, J. (2013). Ciberacoso (cyberbullying) en el País Vasco: Diferencias de sexo en víctimas, agresores y observadores. Psicología Conductual, 21(3), 461-474. https://goo.gl/8hJScy

Garcia-Fernandez, C.M., Romera-Felix, E.M., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2016). Relaciones entre el bullying y el cyberbullying: prevalencia y coocurrencia. Pensamiento Psicológico, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.11144/Javerianacali.PPSI14-1.rbcp

Garcia-Maldonado, G., Joffre, V., Martinez, G., & Llanes, A. (2011). Cyberbullying: forma virtual de intimidación escolar. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 40(1), 115-130. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-7450(14)60108-6

Herrera-Lopez, M., Romera. E., & Ortega-Ruiz. R. (2017). Bullying y cyberbullying en Colombia: coocurrencia en adolescentes escolarizados. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 49(3), 163-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rlp.2016.08.001

Hu, L., & Bentler, P.M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jones, L.M., Mitchell, K.J., & Turner, H.A. (2015). Victim reports of bystander reactions to in-person and online peer harassment: A national survey of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(12), 2308-2320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0342-9

Kowalski, R.M., Limber, S.P., & Agatston, P.W. (2012). Cyberbullying: Bullying in the digital age. Second Edition. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

Laplacette, J.A., Becher, C., Fernandez, S., Gomez, L., Lanzillotti, A., & Lara, L. (2011). Cyberbullying en la adolescencia: análisis de un fenómeno tan virtual como real. III Congreso Internacional de Investigación y Práctica Profesional en Psicología. XVIII Jornadas de Investigación Séptimo Encuentro de Investigadores en Psicología del MERCOSUR. Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina. https://goo.gl/LjWd9G

Lozano, F., Gimenez, A., Cabrera, J.M., Fernandez, A., Lewy, E., Salas, F., Cid, A., Hackembruch, C., & Olivera, V. (2011). Violencia: Caracterización de la población adolescente de instituciones educativas de la región oeste de Montevideo-Uruguay en relación a la situación de violencia en que viven. Revista Biomédica, Medicina Familiar y Comunitaria, 6(1), 18-40. https://goo.gl/Mea5Mc

Lucio, L.A., & Gonzalez, J.H. (2012). El teléfono móvil como instrumento de violencia entre estudiantes de bachillerato en México. IV Congreso Internacional Latina de Comunicación Social. Universidad de la Laguna, Tenerife, España. https://goo.gl/yeu2fY

Muñoz-Rivas, M.J., Fernandez-Gonzalez, L., & Gamez-Guadix, M. (2010). Analysis of the indicators of pathological Internet use in Spanish university students. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13(2), 697-707 https://doi.org/10.1017/S1138741600002365

Mura, G., & Diamantini, D. (2013). Cyberbullying among Colombian students: An exploratory investigation. European Journal of investigation in health, Psychology and Education, 3(3), 249-256. https://goo.gl/aYGvqc

Redondo, J., & Luzardo, M. (2016, junio). Cyberbullying y género en una muestra de adolescentes colombianos. In J.L. Castejon-Costa (Coord.), Psicología y educación: Presente y futuro. Alicante: VIII Congreso de Psicología y Educación (CIPE2016), pp. 1847-1857.

Redondo, J., Luzardo, M., Garcia-Lizarazo, K.L., & Ingles, C.J. (2017). Impacto psicológico del cyberbullying en estudiantes universitarios: un estudio exploratorio. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Sociales, 8(2), 458-478. https://doi.org/10.21501/22161201.2061

Romera, E., Herrera-Lopez, M., Casas, J., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Gomez-Ortiz, O. (2017). Multidimensional social competence, motivation, and cyberbullying: A cultural approach with Colombian and Spanish Adolescents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(8), 1183-1197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022116687854

Salmivalli, C. (1999). Participant role approach to school bullying: Implications for interventions. Journal of Adolescence, 22(4), 453-459. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1999.0239

Salmivalli, C., Karna, A., & Poskiparta, E. (2011). Counteracting bullying in Finland: The KiVa program and its effects on different forms of being bullied. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(5), 405-411. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025411407457

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Bjorkqvist, K., Osterman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:1%3C1::AID-AB1%3E3.0.CO;2-T

Tokunaga, R.S. (2010). Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on Cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(3), 277-287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.014

Varela, J., Perez, J, C., Schwaderer, H., Astudillo, J., & Lecannelier, F. (2014). Caracterización de cyberbullying en el gran Santiago de Chile, en 2010. Revista Quadrimestral da Associação Brasileira de Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 18(2), 347-354. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-3539/2014/0182794

Zych, I., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Del Rey, R. (2015). Scientific research on bullying and cyberbullying: Where have we been and where are we going. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 24, 188-198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.015

Zych, I., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Marin-Lopez, I. (2016). Cyberbullying: A systematic review of research, its prevalence and assessment issues in Spanish studies. Psicología Educativa, 22(1), 5-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pse.2016.03.002

Document information

Published on 30/06/18

Accepted on 30/06/18

Submitted on 30/06/18

Volume 26, Issue 2, 2018

DOI: 10.3916/C56-2018-05

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?