Abstract

This article explains the challenges and evolution of climate change governance by linking governance and diplomacy. The challenges of climate change involve not only international competition for new energy but also related adjustments of global governance in this area. To be specific, the carbon emission reductions are still problematic, and negotiations surrounding financing mechanisms between developed and developing countries hang in doubt. Furthermore, the attitude of the two sides toward CBDRs (common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capacities) and INDCs (intended nationally determined contributions) is disparate. Finally, this article outlines some diplomatic policies for Chinas future developmental trend.

Keywords

Climate change ; Challenge ; Diplomacy ; Governance

1. Introduction

Climate change, a major and potentially devastating challenge, leads to environmental degradation, scarcity, and a radical reform of the energy mix among industrial countries, in addition to other non-traditional security concerns. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon has claimed climate change is altering the geopolitical landscape, as is manifest in increased competition over Arctic resources, increased intrastate and interstate migration, and rising sea levels (FNS, 2009 ). From the 1992 Rio Summit to the Kyoto Conference, the Bali Roadmap and Durban Platform to the 2015 Paris UNFCCC COP21, a generation has passed since the worlds governments began to seriously consider the problems associated with climate change. It is now patently clear that the world must work to combat the climate disaster. However, there are two questions that we ought not to confuse: the first, why has global climate governance been so difficult (Annan, 2013 ), and the second, what factors hamper the effectiveness and fairness of international cooperation. This article provides an explanation of the challenges and evolution of climate change governance by linking governance and diplomacy.

2. Two logics for climate change games

In this analysis of the two logics of the international struggle against climate change, there are two focal points. The first concerns how to limit carbon emissions in different countries on the basis of global collective action theory (Olson, 1965 ). The second concerns the competitive advantage of nations resulting from energy know-how (Porter, 1990 ).

2.1. Logic of collective action in international environmental cooperation

The future of the international struggle against global warming depends on collective action and shared responsibilities (Risse-Kappen, 1995 ). The international regime for averting climate change has sought to overcome this problem since the early 1990s. However, the international effort against global warming has produced mixed results. The explanations of both liberals and constructivists appear powerful in articulating an ideal condition or performance for collective action but somewhat insufficient in explaining the effectiveness of the collective action that has been undertaken. The effectiveness of collective action involves two overlapping ideas: first, which members of the regime abide by its norms and rules, and second, whether the regime achieves its objectives or fulfills certain purposes (Hasenclever et al., 1996 ). Apparently, the effectiveness of the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol is very low. These divergences affect the effectiveness of the UNFCCC so much that they justify the need for a new theoretical analysis beyond constructivism and neoliberalism. Under Mancur Olsons collective action theory (Olson, 1965 ), three variables, selective inducement, optimal group structure or institution building, and major power, determine the effectiveness of collective action. Major power interactions determine the rules and legitimacy of collective action. Selective inducements shape the payoff structure of collective action. Institution building helps to maintain structure stability in collective action. Among these three variables, major power plays the most significant role. First, selective inducements depend on the preference structure and group scale. Second, the flexibility and payoff structure of the Kyoto Protocol affect the effectiveness of collective action against climate change. Third, when an established power abandons global collective action in some areas, some emerging powers will replace its role and push the collective action agenda forward.

Reducing carbon emissions is at the core of collective action against climate change and has impacts on the material and physical foundations needed for the survival of a state. Because no country is able to substantially influence the climate system on its own according to the principle of summation (Kaul et al., 1999 ), all states in the world should make efforts to limit carbon emissions. The key concern is the payoff structure for carbon emission reductions among different signatory countries. Homer-Dixon (1999) has argued that climate change problems may soon increase the level of conflict between poor and rich countries. Some Western scholars have termed developing countries' climate policy the maxi–mini principle, one based on the maximization of rights and minimization of responsibilities. According to this view, some developing states are only interested in free rides and in gaining access to technical expertise, foreign aid, and information to further their goal of economic development (Kim, 1992 ). Stone (1993) used the construct of free-rider behaviors among poor countries responding to climate change to suggest that there is strong evidence to support carbon emission limitations in poor countries.

2.2. International competition for new energy

Energy is fundamental to the prosperity and security of nations. Next-generation energy will determine not only the future of the international economic system but also the transition of power. On the basis of innovation, competition in the energy chain will determine the result of the power struggle and influence power transitions in the international system. The new energy is not only an important constituent of the next-generation energy system but will also change future configurations of international power. As Yergin (2006) of the American oil hegemony and Kennedy (1968) of the British coal hegemony indicated, the prerequisite for significant structural changes in the international system is an energy power revolution based on the emergence of next-generation energy-led countries. Technological innovation is of key importance in the energy power structure. Modelskis long-cycle theory (Modelski, 1987 ) confirmed the historical contribution of the technological revolution and institutional innovation to the rise and fall of great international powers. All have emphasized the effect of a great technological breakthrough on the world economic cycle, indicating that the cycle owes its rise to the technological breakthroughs in energy areas such as the electric steam engine and the internal combustion engine. Porter (1990) explained why nations should make an innovation-based model of comparative advantages a priority in developing their competitive advantage.

With the heated debate on collective action against climate change, Western countries have monopolized the future energy system on the basis of new and alternative energy. Evans (1979) once pointed out that every major power that dominated the international system had some know-how advantages. For now, it seems that a low-carbon economy and clean energy will ultimately determine the future of energy power transition. Golub (1998) recognized that the EUs environmental policy, geared toward boosting the blocs competitiveness and promoting climate negotiations, might also boost its creativity and competitive advantage. In 2007, Stern (2006) confirmed that the EU promoted climate negotiations not only because it was a forerunner in a low-carbon economy but also wanted to achieve dominance in global governance and lay a firm foundation for the future economy. U.S. senior officers Paula Dobriansky, Richard Lee Armitage, and Joseph Nye once proposed that U.S. involvement in climate negotiations could enhance the nations smart power and the competitiveness of its industry (FRC, 2010 ).

Western countries often take the fast-growing carbon emissions in new emerging economies to be a strong contender for explaining global warming. National competitive advantages are associated with carbon emission reductions. Those who advocate in favor of climate diplomacy think of environmental capacity as one important part of a states comprehensive national power. Homer-Dixon (1999) supports the idea of limiting developing countries' environmental capacity and economic growth. Rosenau and Czempiel (1992) used the concept of a balance of payments instead of a balance of power in global environmental governance and argued that developing countries should share the costs and responsibilities for global environmental protection.

3. The current of climate change governance

The fight against global warming can be described in terms of common goods. Developed and developing countries share a common interest in protecting the Earths climate system while maintaining differences with respect to development and obligations. Prompted by international efforts, there has been positive impetus for negotiations prior to the 2015 Paris Climate Conference. With the exception of the Lima Conference, three rounds of negotiation conferences were organized by the 2014 Convention Secretariat. The Durban Platform for Enhanced Action finally entered the consultation phase of contact group, achieving closer access to the substantive content. In September 2014, the UN Climate Summit in New York succeeded in improving political consensus among UN member states, attracting financing and responding comprehensively to the global warming crisis. In October 2014, the Europe Council passed the 2030 Framework for Climate and Energy Policies as the first one to formally announce climate change policies and quantify an emission reduction target of greenhouse gases (GHG) among the major economies. In November 2014, the U.S.–China Joint Announcement on Climate Change was signed to declare actions and goals for coping with climate change after 2020. Following this, the U.S. and India also reached a consensus on fluorinated gas reduction. The positive actions of the major economies became the driving force for negotiations. In December, the Lima Conference passed the Lima Accord, under which all countries should submit plans to a UN website to be made available to the public. The most important achievement of the 2014 climate negotiations is the 4-page Lima Accord. The document upholds the principles of the 2015 Paris Climate Conference, the definitive timetable to submit INDCs and associated information, as well as arrangements to improve the levels of emission reductions before 2020. Above all, the Lima Accord and previous climate negotiations made the 2015 Paris Climate Conference tougher; therefore, it is necessary for every country to make preparation to fight and compromise.

There are three issues to focus on the 2015 Paris Climate Conference: The first concerns INDCs, which have and will continue to be the top priority for global climate change governance. The INDCs will serve as a basis for achieving the goals of UNFCCC based on a bottom-up approach for achieving a low-carbon growth path. The INDCs can also help to build a reference on how great an effort individual countries need to make in reducing carbon emissions, based on their national circumstances, thereby narrowing the gap between developed and developing countries. For those concerned about climate change, dividing responsibilities for reducing emissions by the required amount between developed and developing country is a crucial concern. In the 2015 Paris Climate Conference, there are no longer two categories of carbon emitters as per the Kyoto Protocol of 1997, otherwise developed countries would need to cut emissions and developing countries would need to make intended contributions. INDCs will make every country show its emission reduction responsibilities to the international community (Table 1 ). Under the INDCs, every country will provide mitigation actions and those willing to do so may also provide adaptation actions. In 2015, international community must work hard to guarantee the signatories to submit the spectrum and information of INDCs, and to make the INDCs fair and ambitious. The second issue concerning the 2015 Paris Climate Conference is to ensure every element and basic text of the 2015 Agreement, especially adaptation capacity building, climate finance, technology transfer, and private sector participation. The third is to ensure that the work plan succeeds in strengthening the promise of emission reductions. In addition, it draws growing attention in the legal forms of the 2015 Paris Climate Conference outcome.

| Country | INDCs content |

|---|---|

| Mexico | Unconditional: 25% reduction below BAU (business-as-usual) for the year 2030 |

| Conditional: 40% reduction below BAU for the year 2030 concrete adaptation actions | |

| Russia | Limiting emissions to 70%–75% of 1990 level |

| U.S. | 26%–28% reduction below 2005 level by 2025 |

| Norway | At least 40% domestic reduction compared to 1990 by 2030 |

| EU | At least 40% domestic reduction compared to 1990 by 2030 |

| Switzerland | 50% reduction relative to 1990 level by 2030 |

Considering the above progress in climate change governance, there are three key challenges, outlined as follows.

First of all, carbon emission reductions, the core problem of climate change, remain a dilatory and slow process. Ian Fry, the envoy for the small island nations climate group argued that climate negotiation process was too slow to support rapidly reducing emissions (Harvey, 2014 ). Climate change negotiations have always concentrated on the goal of cutting carbon emissions, and the central issue under the UN platform is whether we can urge developed countries or all countries to develop large-scale quantified emission reduction goals. Although the plans of countries to start INDCs have passed, some key issues which reflect justice and differentiation are still in doubt. Furthermore, the decision appears to push global negotiations of emission reductions into a slack pattern. As many non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have said, however, considering the dynamics of the self-interpretation of INDCs in light of different national circumstances (instead of principles of the convention) and the process without any assessment, will lead the 2015 Agreement to complete a from bottom to top pattern, widen the gap of emission reductions inevitably, and make the target reduction of 2 °C amount to nothing.

Secondly, negotiations about financing mechanism have and will continue to fall into disputes and disappointment; rich countries have shown no intention of fulfilling long-term financial aid requirements. Launched at the 2011 UN Climate Change Conference and designed to finance sustainable development, the Green Climate Fund was held in the 2012 Durban Climate Conference. During 2012 Doha negotiations developed countries promised to put $100 billion per year into it by 2020. Over the past 3 years, a handful of developed and developing countries have pledged contributions to the Green Climate Fund. However, up until now, there has been very little progress toward the $100 billion goal over climate finance. As Goldenberg (2014) states that developed countries cannot fulfill their earlier promises of mobilizing billions to help developing countries fight climate change. The Green Climate Fund aims to raise $160 million in 2014 and 2015, but has received only the German pledge so far. Currently, the funding scale of the Green Climate Fund is up to $10.2 billion. About half is from the EU and its members, with 30% from U.S. and 15% from Japan. Additionally, the countries not included in Annex I (Annex I countries include the group of countries specified in the annex to the UNFCCC, and is essentially composed of industrialized countries, plus most of Eastern Europe and the countries of the former Soviet Union), like Peru, Chile and even the Republic of Mongolia, are also funding, an action that has been widely praised by developed countries and international society. But to the long-term fund, $100 billion a year before 2020, developed countries refused to offer the scheme and rejected reflecting anything in the 2015 Agreement. The funding of the Green Climate is just a little more than the shell, and the long-term climate funds are still vague.

Third, developing countries believe that the range of INDCs should never concentrate on mitigation, and instead should include adaptation, funds, technology, capacity building, and so on. In contrast, developed countries insist that INDCs should be centered on slowing down and other elements should take overall accounts in the 2015 Agreement. The UNFCCC Executive Secretary Christiana Figures has highlighted several breakthroughs, including the recognition that adaptation is as important as mitigation in INDCs (Harvey, 2014 ). All countries should consider offering relevant content on adaptation as part of providing the relevant information. However, when it involves the correspondence of specific information, it has something to do with slowing down, such as with the base year, time, assumptions, and methodology. The least developed countries and small island states ask to submit qualitative climate adaptation information such as low-carbon development plans and strategies. Because the information offered by the signatories is not strongly requested and the content is not uniform, it is hard to guarantee the comparability of future information, which increases the difficulty of integrating information received. In addition, the UN continues to ask developed countries and international institutes to assist the countries that need help in preparing their information. Satisfying the appeal of some developing countries to hardwire the action to support is difficult.

Fourth, the efficiency of global climate change negotiation has decreased. The biggest obstacle lies in the divisions between developed countries and India, China, and African countries over fundamental issues (TBM, 2014 ). A serious lack of political will and mutual trust between developing and developed countries has accounted for a prolonged slack on UNFCCC, and excessive attentions to wording. Though the negotiation did not collapse, its efficiency of the negotiation caused concern and deterioration. In a short-term and narrow position, this deadlock is conducive to maintaining the institutional arrangements that are favorable for one self, whereas from the long-term and global view, the continued decrease of UNFCCC efficiency will further damage its significant role as the primary channel, which means outer UNFCCC mechanisms will seize additional chances. The World Wildlife Fund and other NGOs have criticized the current negotiation for having far less global carbon emissions against global warming, stating that the current international collective actions cannot make the global emission peak before 2020, and by the meantime, the globe is very hard to achieve clean energy structure (Goldenberg, 2014 ).

Finally, the CBDR continues to be revised for the new interpretation. The CBDR principle demands that developed countries reduce CO2 emissions and that developing countries and underdeveloped countries reduce carbon emissions voluntarily. It leaves developing countries without the responsibilities of emission reductions, which is laid as a broad basis for developing countries and their cooperation. Having said this, developing counties hope to continue with the principle of CBDR just like the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol. Developing countries insist on the convention framework and the basic principle of CBDR, while developed countries object to the dichotomy of the original signatories, advocating that it is supposed to interpret the convention principles in accordance with the advancement of time. The LMDC (Likely Minded Developing Countries) bloc has spoken firmly on respect for the core principle in these CBDR negotiations: in this case, the developed countries need to act first because they have done the most to create the problem of climate change. The G77, EU and the LMDC have come together in a coordinated strategic move. The Verb has learned that the Philippines, who led the newly formed LMDC group, was primarily responsible for tonights events (Roberts and Edwards, 2012 ). This is the red line without mutual concession of the two groups. Ultimately, the Lima outcome reiterates in its forewords that the Durban Platform will be under the convention, instructed by the principles of the convention, and that the 2015 Agreement emphasized in the text should reflect the CBDR principle in the light of different national circumstances. Thus the CBDR principle will be reinforced with some new interpretations in 2015 negotiations, as the negotiations text insists on the importance of “(their) commitment to reaching an ambitious agreement in 2015 that reflects the principle of CBDR and respective capabilities, in the light of different national circumstances”.

4. The change of global climate change governance

First of all, the UN is the platform for global governance decision-making, but it is not the driver of domestic decisions for carbon emission reductions. Domestic interests for developed or developing countries are the only strong driver force for global climate change governance. The alliance of global climate change negotiation is becoming lenient. Management mechanisms of climate change with UNFCCC as the core have been questioned. Cooperation mechanism patterns are characterized by the Concert of Powers, e.g., the G20 and the major economic forums; market resources are patterned from bottom to top, and systems like these continually grow between developed and developing powers. The U.S. has initiated processes about energy security and climate change issues for the main economic bodies since 2007. The processes which aim diminishing GHG emissions have members including 17 of the most powerful economic bodies in the world, and the relations between UN climate mechanisms and these processes can be described, in part, using the word ambiguous or conflicting. There are growing numbers of new alliances within the environmental field, and the majority of these are formed between developed and developing countries. There has been a Cartagena Dialog for Progressive Actions under the EU background (Clark, 2012 ). The enhancement of the developing countries' discourse rights in the varieties of international cooperation is the direct reflection of their soaring economic power. The rise of the BRICS, namely Brazil, Russia, India, South Africa, and China, the Next Eleven (Philippines, Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, South Korea, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Turkey, and Vietnam) and the VISTA (Vietnam, Indonesia, South Africa, Turkey, and Argentina) all show the improvement of the developing countries' position in world politics and economics.

Second, the existing CBDR principle in climate change will face further dilution. Historical responsibilities and distinctions between the South and North were both important points during all climate negotiations (AFP, 2013 ). The U.S. climate negotiator argued that the firewall between developed and developing countries enshrined in previous agreements must be removed. The developed countries have and continue to demand that the UN revise or redefine the principle of CBDR, i.e., in “Efforts to breach the firewall between developed and developing countries enshrined in the Kyoto Protocol by referring to major economies as distinct from other developing countries” (Kumar, 2015 ). With the foundations such as CBDR that were fixed in the 1990s and the Kyoto Protocol, the South and North Arrangement on global climate governance has been established. Developing countries account for only 32% of global CO2 emissions; China accounts for 11%, whereas developed countries are in the absolute dominant position about emission reductions potential as well as the amount of emissions and other aspects. Thus there has been a common view that developed countries ought to undertake reduction responsibility first and offer developing countries financial and technical supports. After more than 20 years of development, things such as capacity, potentialities, and economic power have changed tremendously between negotiators. The major developing countries' potentialities on emission reductions are gradually increasing. From 2000 to 2030, two-thirds or three-quarters of growth on carbon emissions based on energy usage may come from developing countries.

The success of climate governance lies in the carbon emission reductions ambitions of the developed countries; however, Western countries take China to be the worlds largest emitter and disagree with it having the largest developing country status and avoiding the burden for emissions cuts. As an large emitter, India is also considered to be a developing country under the Kyoto Protocol. Developing countries believe that the rich countries have not shouldered a fair share of the burden and should lead by example, in cutting emissions and also providing financial support to poorer nations. Interpretations of this point can vary. The 2014 U.S.–China Joint Announcement on Climate Change has been the vital impetus for the new interpretation of the CBDR. It reflects the good image of China as it not only safeguards the rights and interests of this developing nation, but also takes on the responsibility. The new understanding of CBDR will include historical responsibility, respective capacities and capabilities of countries, and national circumstances, and will argue that the 2015 Paris negotiations should be dedicated to putting numbers on the table, which means that each countrys action must reflect its historical contributions to raising cumulative levels of GHG, and also its wealth (FA, 2014 ). From the interpretation of Figures, the Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC Secretariat argued that the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities has changed by intergrading historical responsibility, respective capabilities and different national circumstances.

Third, the main competitions in traditional UN climate negotiations occur primarily among China, the U.S., and the EU, whereas other forces have attached themselves to these major powers and formed distinct groups that affect the overall balance. However, there is a downgrade in UN negotiation capacity; consequently, regional groups begin to emerge and gradually become significant powers in negotiations. These groups express different demands; gradually, differences of interest occur, especially within developing countries. Small island states have scattered geographic locations but their common geographic environment has equipped them to be an important force during negotiations about climate. Common topics gradually increase between African groups as the representative of less developed areas and the LDC (Less Developed Country) group. Besides the consistent demands to developed countries about emission reductions and support offering, a trend that demands newly emerging nations to undertake responsibilities related to emission diminishment and offering support has already occurred. Many countries in the League of Arab States themselves depend on fossil fuel exportation for economic reasons and therefore have a consistently negative attitude toward the rigorous arrangements on global emission reductions. Columbia and some of the Latin American countries have intimate relationships with the U.S., both in politics and in economics; they have made positive responses to the U.S. proposal in climate negotiations. Concurrently, other newly emerging Latin American countries such as Brazil and Argentina have formed alliances such as LMDC (Likely Minded Developing Countries) and the BASIC group (Braila, South Africa, India and China) with trans-regional countries (China, India, countries in Southeast Asia, etc.) to avoid the over-rigorous emission reductions tasks and maintain their high speed development in the future. There are also Latin American countries such as Venezuela, which struggle with developed countries (headed by the U.S.) under the background of international politics and economy; they have brought this trend into climate negotiations. The differences in interests within developing countries have gradually pushed them into a disadvantageous position during negotiations with rich countries. The patterns of the EU plus the Small Island states, the Umbrella Group plus the IALAC (Independent Association of Latin America and the Caribbean) are breaking the developing countries' unity as the pattern G77 plus China.

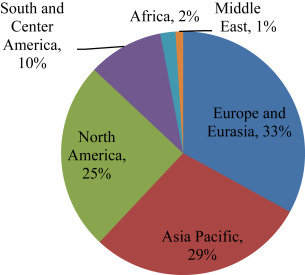

In particular, every country is currently facing the four energy challenges in order to protect a reliable and affordable energy supply and to achieve the rapid transformation of a low-carbon, efficient and environmentally friendly energy supply system, according to Stern (2006) . The global low-carbon future and the emergence of low-carbon technology will enhance the energy industry worldwide and the strategic position of the equipment manufacturing industry. Say that the success of dealing with these four factors of energy security will determine the future prosperity of human society is no exaggeration. There is an evident correlation between energy competition driven by climate change and the international political and economic environment, know-how, and ability and possession of resources. The interaction of these factors constitutes the driving force for renewable energy development in the world (Fig. 1 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Global renewable energy consumption in 2014 (BP, 2015 ). |

Every country now takes low-carbon and clean energy to be an economic powerhouse (Figures, 2012 ); by 2012, 118 countries had climate change legislation or renewable energy targets, more than double the number in 2005. There are increasing local, voluntary efforts to reduce deforestation and emissions not covered by the UN framework. In 2010, renewables accounted for 20.3 percent of worldwide electricity, as compared with 3.4 percent in 2006. The solar photovoltaic, solar water heaters, and wind energy capacity of China is near the top of the scale. Their solar photovoltaic capacity is more than 10 million kW and wind energy capacity is more than 25 million kW annually. Chinas solar power production is predicted to surpass that of Germany in 2015. Moreover, Chinas renewable energy will lead the world. In 2013, U.S. president Obama said that the U.S. should prepare for the renewable energy competition from China and Germany, and the U.S. will encourage private sectors for more investment on clean energy (DJNS, 2013 ).

In fact, the deficit in global climate governance is growing. Keohane (1984) once argued that if there is not an international regime, prospects for cooperation are bleak indeed, and dilemmas of collective action are likely to be severe. The 2015 Paris negotiations call for questions surrounding the seriousness, legitimacy and effectiveness of the convention. For the globe, however, it has been scientifically proven that it is increasing the deficit between the risk of global climate change and global governance due to the slowness of the international climate negotiation progress. On the one hand, historical responsibility clearly gives way to national circumstances justifying themselves at will, which means that seriousness and legitimacy are challenged. On the other hand, enhancing emission reductions appears increasingly unrealistic, as does providing long-term adequate funds. As most countries are satisfied with the status quo that “as long as I do not take on more responsibility, I do not care about the others”, the climate leaders are rare, the countries are worldly-wise and play safe, and the climate cooperation under the framework of the convention will become increasingly loose and powerless. The deficit of climate change governance also shows the negotiations and the policy-decision ways to be driven by signatories, making the text more cumbersome. Consequently, it has to be finally given up or left as the hopeless mess for following negotiations, so that the outside established text must then be the choice. With the uncontrolled democracy, the convention will become an ineffective institute, which would lead to doubt about its effectiveness.

5. Future development trends

In the 1990s, the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol replaced the ideological confrontation in the cold war with the antagonism between the developing countries and the developed countries, while they in turn have made the climate change issues not just scientific topics but political and developmental ones, making negotiations increasingly tough. At present, the developed countries not only want the Durban Action Enhancement Platform to reduce historical responsibility and transfer emissions responsibility through competition on the platform, but also expect the Durban Platform to postpone the rise and development of China as well as maintain international political and economic orders dominated by Western countries. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon hopes to keep the international community on track for a comprehensive, legally binding agreement on the climate change issue (Ban, 2012 ). The international community will definitely take time to reach consensus on global climate change actions, for the following reasons.

Firstly, the structure of global climate change negotiation is moving back to great power politics. Different countries face different effects due to climate change, and distinct national interests have formed. Consequently, during negotiations, many groups that focus on climate can now be found, such as the EU, the Umbrella Group, the G77 plus China, AOSIS (Alliance of Small Island Stated), OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries), etc. There are two main lines running through the process of climate change negotiation: one is the inconsistency among members of the Umbrella Group, for example the differences between the EU and the U.S., and the other is disagreement between developing countries and developed countries. In addition, both of these lines have become more obvious following the conference in Doha. Although the traditional pattern of two main groups still exists, some kind of change has already happened in the situation caused by tripartite powers (EU, U.S., and developing countries). In order to persuade the U.S. to join the 2015 Agreement and pull the firewall down together, the EU has temporarily abandoned the claim on global treaty with a legal framework, and supported U.S. with all their strength. Developing countries have maintained a unity in politics. These countries, together with other members of LMDC (Lagos Multi-Door Courthouse), have exerted abilities when countered with the West. Although claims from AOSIS, LDC, and AILAC (Independent Association of Latin American and Caribbean) remain intense, these claims have gradually exceeded their abilities now that the scenario has turned back to great power politics. However, when examining the matter from different angles, the underestimation and damage on AOSIS and LDC interests may also compromise the whole unity within developing countries, given that it is already divided.

Second, the newly emerging developing countries will continue to be seen as the focus of negotiation. Developed countries have tried to persuade the newly emerging developing countries to accept climate obligations. In 2015 climate negotiations, the emerging market countries received so much pressure from developed countries that they accepted the proposal to implement qualified emissions after the year 2020. For those emerging market countries that are staying at an economic rapid growth period, the industrialization speed may thereby suffer a tremendously negative influence. Meanwhile, this also shows that the developing countries' vulnerable position still gains no fundamental change during their contest with developed countries. In 1992, the Kyoto Protocol was created to bring GHG seven percent below the levels that existed in 1990. Fifty-five industrialized nations have to sign the protocol to lower GHG emissions by 55%. This unprecedented treaty committed industrialized nations to make legally binding reductions. However, in recent years, as the tendency of distribution on international powers goes toward balance along with the acceleration on political multi-polarization and globalization of the world economy, the international system is in profound transformation, and this has resulted in the international climate negotiations reaching a turning point. Under the period of bi-adjustment and bi-transformation of the structure of world politics, the economy, as well as climate change negotiations, has had negotiating processes about climate that parallel the pattern of global politics as well as the economy, which can be described as promotion on East, demotion on West. Since the 2008 financial crisis, newly emerging developing countries represented by Brazil, South Africa, Russia, India, and China have had high speed economic developments, whereas developed entities such as U.S., Japan, and Europe have faced severe crashes, and their position in the global economic structure has also experienced relative degradation. Since the 2008 financial crisis, the BRIC countries' contribution to global economic growth was in excess of 50%, and the share of Non-Annex I Parties in global economic output has grown from 17.9% in 1990 to 30.9% in 2012. In 2012, global primary energy consumption grew by 1.8% with a contribution of 90% in China and India.

The rise of the emerging countries and their position in the international economy certainly represents the general trend. Meanwhile, developed countries' capacity to dominate the world economic order is restrained more and more by developing countries, especially emerging market countries. After more than 20 year development from the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, things like capacity, potentialities, economic power, etc., have changed tremendously among negotiators, with the core of global emission structures gradually shifting to chief developing countries. The U.S. and EU have turned the point toward China and India, claiming that these countries should show their cards (McDonald, 2013 ), and emphasizing that entities with high speed economic growth should participate in emission reductions, using China as an example (Paul, 2013 ). The EU has urged China and U.S. to play positive roles. During the process, responsibilities and positions within developing countries change continuously. Conflicts between developed countries and developing countries have been transformed into conflicts between high-emission countries and low-emission countries. The distinction between high-emission and low-emission countries was suggested by U.S., and supported by the EU and some other countries. This kind of partition depended upon practical emissions and potentialities of emission reductions. Global CO2 emissions in 2011 hit a new record of 34 billion tons, one-third of which was constituted by the total emissions of China and India, well-matched with OECD countries. The emissions per capita in China are 7.2 tons, only 0.3 ton less than the level in EU (JRC, 2012 ).

Finally, a difficulty in global governance in climate changes concerns how to coordinate relations among China, the EU and the U.S., as well as how to consistently protect the institution construction of the Durban Platform in the framework of UN. First of all, it has to admit that climate change has already stimulated changes in geo-economy and geo-politics, so that the traditional top-down governance of the UN has hardly controlled the carbon emissions of each country under the endurable capacity of the Earth. Moreover, it is true that the competition is also the impetus for climate change negotiations. Competition among great powers like China, the U.S. and the EU do not just exist in the sum-up relations of the Westphalia power system, as the competition of low-carbon and new energy could facilitate the entirety and interdependence of global development in new resources, as well as improve the virtual course power and advocacy rights of the emerging powers in new resources. Nowadays, China, the EU, the U.S., and other powers with renewable resources will play a leading role in climate change governance, while the countries adequate in renewable resources like Brazil and those in North Europe will play an increasingly prominent position.

6. Recommendations for China: climate diplomacy

As one of the worlds leading developing countries, China is central to regional and global efforts to fight global warming and climate change. Any successful international effort to mitigate threats to human and national security posed by climate change must inevitably include China. Chinas population has reached 1.3 billion, and its economy is one of the worlds largest and fastest growing economies. Consequently, China is experiencing widespread climate challenges with severe local, national and regional consequences. After the 2009 Copenhagen Conference, any conference of the parties is intended to make a difference, if it is in favor with the general public and is irresistible. The protracted negotiations of the convention foster various actions from outside, which is a tendency. China must adapt to this. At present, the fund for South–South has been established and will be increased in the future, which is a good start. In the One Belt and One Road strategy, content should include climate change cooperation and the ideas of mitigation, adaptation and low-carbon development. This could enrich the connotations associated with Maritime Silk Road and the Silk Road Economic Zone, promoting the concepts internationally, developing new areas and new patterns of international cooperation in climate change for China, and making a contribution to create a favorable international environment for low-carbon development. With regard to the climate change crisis, the complicated and pressing negotiation is the key challenge facing China, especially considering the increasing influence of its energy consumption and carbon emissions on global climate changes. With respect to this, emerging economies have become key stakeholders in the Bali Roadmap and Post-Kyoto negotiations. Considering such a crisis as climate change is being discussed and negotiated all over the world, solutions with all-round knowledge-based efforts will build the future for international society. It has frequently been argued that China should clarify their climate diplomatic position in order to pursue greater understanding and support from the developed world and the international community. China seeks to act as a responsible stakeholder in the international system while pursuing a Scientific Outlook on Development. While mitigation (emission reductions) is important with reference to practical measures for global warming, adaptation to climate change-induced impacts is equally important for China. At the strategic level, China has now changed its policy orientation defined by an over-emphasis on energy security and a relative neglect of climate change and environmental issues. Climate security and diplomatic issues have been incorporated into the national strategy and long-term development framework, to promote comprehensive management of the emerging national strategy. For China, in accordance with the present interests in the short run, a mediocre result is better, as any achievement could set China back from its relatively favorable position at present. Current climate negotiation is relatively favorable to China. Though the principles of the convention raise the risk of explicit interpretation again and respectively, the principle of National Autonomy made during the Warsaw Conference could make China ease temporarily; in particular, this will temporarily relieve pressure on China associated with the INDCs not posing the risk of formal assessment.

Firstly, China should promote the negotiation back to great power politics or great power governance, as well as improving the efficiency of the convention. It is imperative to interpret the principles of the convention with the times. At present, it is impossible for the new recognition to be accepted widely, however, it is the best choice for emerging powers like China. With the bottom line of determining-on-ones-own, the pressure of negotiation has been mitigated instead of increasing. Based on this, China should continue to uphold a positive attitude in signing the Sino–U.S. agreements, promoting negotiation back to great power governance, paying attention to deal with relations between the U.S., the EU and the BASIC group, instead of arguing over issues like the range of INDCs, loss and disaster, and slowing down the connection between action and funds with developing countries, which are important to China. According to the UN report, the U.S.–China announcement hinted at a fundamental shift putting developed and developing countries on a more equal footing (Revkin, 2014 ). Particularly, the U.S. takes China–U.S. cooperation to be the foundation of the 2015 Paris Climate Conference. President Obama has said that the U.S. will seek the climate change partnership with China, India and other large polluters before the 2015 Paris Climate Conference, and the U.S. will show its leadership in climate change regime building (Goodell, 2014 ). China should be positive in devoting itself to mitigation, promoting the negotiation progress, improving efficiency, and working to maintain and improve the effectiveness of the convention.

Secondly, China could be flexible in assessment and legal forms of the INDCs, contributing to recover the seriousness of the convention. In addition, many developed Western countries tend to exaggerate the development speed of developing countries and advocate varieties of the so-called Threat Theory, which aim to restrain the developing countries' development speed, continue to maintain their dominant position and guarantee their own benefits. For instance, Western countries have always exaggerated the China environment-threat theory. This apparently only underlines the fact that Chinas environment problem will or already threatens other countries' benefits and that developed countries hope to bring China into the global environmental governance system dominated by them, which will force China to bear a larger responsibility. However, on a deeper level, it refers to each countrys competing energy innovation and future development space. As for the expansion of the environment problem, the developed countries portray China as world polluted big power, environment crisis maker, and mercantilist lacking global environment responsibility, etc., forcing China bears responsibilities and obligations beyond its ability (Sanders, 2002 ). Therefore, developed countries will never hand over their dominant right easily, only due to developing countries' rapid development. There is still a long way to go before an establishment of fair international economy order and an equal dialogue with the developed countries arises. It is unwise to lessen the strength of the emission reductions to developed countries before 2020, in order not to assess INDCs temporarily. According to the latest scientific understanding, it is a natural process to assess the gap between the comprehensive effects from every countrys target and the 2 °C target, which is also reflective of the seriousness of the convention. Although there is no temporary and present assessment, this can hardly be avoided after 2015. Although there is no formal assessment inside the convention, the assessment outside the convention will be active. Additionally, the bottom-up institution in international climate change should not be totally loose. The legal form of the targets determined on ones own could be forceful; that is, there exist unified and strict regulations in inspection and obedience, which is vital to maintain the seriousness and the main-channel position of the convention. From this point of view, China should be flexible and support the choices in the new protocol with a relatively strong binding force of law.

Thirdly, China should adjust the negotiation strategy, maintain two kinds of interests, development space and national image, and consider the strategy of protecting the strategic sustenance of developing countries, with discretion. With relative mitigation of pressure, Chinas negotiation strategy should be adjusted and focus on balancing national image and strategic sustentation. In short, it is a priority to improve image after guaranteeing emission space. National image is a specific reflection of national power, a kind of externalization of ethnic culture and spirit, as well as of the soft power of a country. In complicated cooperation and competition, there is an important significance for the national image. China should correctly identify its core interests. China is a developing country and just stepped into relatively comfortable life society. After reform and openness, China experienced a rapid economic development and rise in living standards, including living energy use having improved a lot. In spite of the gap compared with developed countries, Chinese living quality improvement shall never become like the extravagant ways of the developed countries. Until now, China has insisted on their core interests, which including striving for development space, maintaining the strategic sustaining of developing countries and establishing the image of responsible power. Compared to striving for development space without doubt, the latter two are somewhat controversial. The Small Island Countries, the least developed countries and part of the Latin countries of the developing countries demand that the major economies and the major emission powers play a leading role, and also ask that China further reduce emissions more as well as offer funds and technology assistance to other developing countries. However, many developing countries treat China as the leader among the developing countries. China is expected to take more responsibility in emission reductions to stimulate the domino effect, making other emerging developing countries like India speed up their attempts to take responsibility. As a result, China will face a dilemma among developing countries and hesitate in negotiations. This will lead to a defensive posture in negotiations, limitations in flexibility and damage in establishing the image of responsible power. Therefore, it is necessary to review the proposal and strategy of maintaining the strategic sustenance of developing countries.

Fourth, China should develop a norm such that it becomes the great power and the host in climate change governance. China could, and we argue should, show moral leadership on climate change, something that has been lacking among developed countries. Alas, bearing in mind what we have said, it seems unlikely that China will undertake such a pro-environment leadership role in the Asia Pacific region or among developing countries more broadly. There are clearly many Chinese scientists and concerned officials who would like China to do much more. But there are also vested economic interests, exacerbated by Chinas infatuation with rapid economic growth and wealth creation, which overwhelm the environmentalists. There is a burgeoning car culture, the same mistake as that made in the West, with a rapacious appetite for petroleum. More broadly, there is an effort to emulate the Wests development and Western peoples lifestyles, but with this comes an emulation of their terrible history of pollution. This is unfortunate because a concerted transition to an economy that produces fewer carbon emissions is possible, especially with financial and technical aid from the developed world. However, such aid would have to come with clear restrictions that the Chinese government has shown an unwillingness to accept. The upshot is that, in the future, there will be some improvements that will limit the increases in Chinas carbon emissions compared with what they might otherwise be. China should consider positively what international climate institute it needs and what public goods it could offer after 2020. China has the second largest economy in the world, the double of which means it is expected to be closer to the lowest level of the high income countries around 2020. It is China that seems to have made a crucial transition from developing to developed in the perception of the others, especially the U.S. (China and the U.S. being the biggest emitters of GHG). For this reason, China has to be brought to the negotiating table with the rich countries. This is a pressure that it is good at dodging; holding on to its developing country status. The U.S. is equally resistant to anything that looks like a treaty or a legal commitment (Sethi, 2012 ). At that time, no matter how actively or passively, China could hardly avoid becoming one of the main governors in the world and one of the objective hosts, such that it would become necessary to focus on the efficiency of global governance when China really becomes the principal global governor. However, China should prevent thinking opportunistically, such as in terms of whether it is good or not to have a negotiation result, and whether it is good or not to have a negotiation result earlier so as to promote duly reaching a conclusion. Moreover, China should review proposals and negotiating position of the developed countries in Europe and America, in order to have a plain, tolerant and unconventional attitude toward the positions and proposals from developed countries. An important principle is to distinguish the public elements and private elements in their suggestions. For instance, it is from the private elements that the developed countries reduce responsibility of emission reductions in the new global climate negotiation and reduce efforts to assist with funding and technology. Hence, China should insist on its principles instead of making a concession too easily. In contrast, public elements include the developed countries having opinions aimed at improving the efficiency of international climate institutes, including completely coverage, legal responsibility and negotiation efficiency improvement. To some extent, this is reasonable. With the changes in Chinas identity, we increasingly discover that some proposals from Western countries are somewhat reasonable. China has made great efforts in enhancing the South–South cooperation, which has injected new vitality into cooperation of this kind. According to the UNEP, UNEP and China are seriously involved in South–South and triangular cooperation projects, which allow them to bring together the best expertise and thereby particularly allow South–South cooperation to take a much higher priority.

Fifth, China should deeply understand the divisions between developing countries and strengthen cooperation between new emerging developing countries. It is difficult to avoid the fragmentation of negotiating powers, particularly among developing countries. However, new emerging developing countries should be wary of an alternative G77 and China hosted by developed countries. In addition, new emerging economies have to face the pressure of the vast number of developing countries, especially the least developed countries and small island states. The emerging developing powers have the same appeal and stay in a similarly pressured environment in international climate cooperation negotiation. Consequently, in talks about bearing international emission reductions, China shall continue to strengthen the coordination of emerging developing big powers and strive for its deserved position and discourse rights in climate energy cooperation. It is a significant pivot point of emerging big powers in a variety of international games that strengthening communication and developing good cooperation with Small Island Countries and the least developed countries is useful. Therefore, emerging powers should support the vast number of developing countries (especially the tropical zone, rainforest and Small Island Countries) by requesting that the developed countries implement their fund assistance promise as soon as possible and their other assistance promises. At the same time, the emerging powers themselves shall also provide these countries or regions with assistance on improving their ability to adjust to climate change, which includes providing a variety of advanced energy conservation and climate emission technologies. The new energy conservation enterprises could also expand the market and accelerate development. In addition, the climate problem has mainly been caused by historical emissions from developed countries, thus the developed countries have an obligation to help developing countries with climate problems. However, the developed countries didn't fulfill their duty to help developing countries. Therefore, emerging powers should unite with Small Island Countries and the least developed countries, and request that the developed countries fulfill their responsibility by providing developing countries with corresponding funding and technology.

Finally, the low-carbonizing of the social economic model is the current trend of global development. Once a country has grasped the idea of advanced low-carbon technology, the country will take a strategic highland in international political and economic cooperation. The progress of low-carbon technology, especially the low-carbon technology development of the energy industry, and its equipment manufacturing industry, will become a crucial aid in improving their economic competition with countries worldwide. China is now confronting the huge pressure for CO2 emission reductions, and meanwhile is also facing an opportunity for a great leap forward in development. Chinas social and economic development strategy not only needs to fully consider energy supply security, but also needs to bring climate security and ecological security into the structure of national security and long-term development strategy, and bring energy and climate change into national strategic structure at the same time. The government needs to positively strengthen the construction of the laws and regulations relating to climate change. Management institutions need to be set up and completed, which might help to provide Chinas low-carbon development with a good institutional environment, policy environment and market environment. Promoting Chinas low-carbon technology development, expanding research and the spread of energy conservation and emission reductions, and bringing in clean production and new technologies bring that appropriately grasp low-carbon core technology as early as possible are also required. It is an effective measure to promote the work of energy conservation and emission reductions that develop the emission index deal by making use of market institutions. Chinas carbon emission deal institution is still imperfect and the market scale still needs to be expanded. The carbon emission deal needs to be integrated with the international market as soon as possible, through which promoting energy structure adjustment and clean energy development will be possible. The low-carbon concept will not only revolutionize the economic development model, but also take the low-carbon consumption to be a social moral, which will then lead to the transformation of the national living and consumption model. Technology is the most important long-term strategy to deal with climate change. At the technical level, Chinese science and technology have provided some good tools to address climate change. China should vigorously develop energy-saving and energy-efficient technologies, renewable energy and new energy technologies, and clean coal. Other technologies China should explore and utilize include advanced nuclear energy, carbon capture and storage, bio-sequestration and carbon sequestration.

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by the project of research on key technologies for synthesis problems during climate negotiations under 12FYP organized by Ministry of Science and technology (2012BAC20B02 ).

References

- AFP, 2013 AFP (Agence France-Presse); UN Talks Approve Climate Pact Principles; (2013) http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/afp/131123/un-talks-approve-climate-pact-principles-1

- Annan, 2013 K. Annan; Climate crisis: who will act?; N. Y. Times (2013), p. 25

- Ban, 2012 K. Ban; Secretary-general Ban Ki-moons Remarks on the “Momentum for Change”; (2012) http://www.un.org/climatechange/blog/2012/12/secretary-general-ban-ki-moons-remarks-on-the-momentum-for-change/

- BP, 2015 BP (British Petroleum); BP Stattical Review of World Energy 2015; (2015) http://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/about-bp/energy-economics/statistical-review-of-world-energy.html

- Clark, 2012 D. Clark; Revealed: how fossil fuel reserves match UN climate negotiating positions; The Guardian (2012) http://www.theguardian.com/environment/blog/2012/feb/16/fossil-fuel-reserves-un-climate-negotiating?newsfeed=true

- DJNS, 2013 DJNS (Dow Jones News Service); Full Transcript of Obamas Remarks on Duncan Clark; (2013)

- Evans, 1979 P. Evans; Dependent Development: the Alliance of Multinational, State, and Local Capital; Princeton University Press, Princeton (1979), pp. 54–56

- FA, 2014 FA (Foreign Affairs); Lima Call for Climate Action Lays Foundation for 2015 Agreement in Par; (2014)

- Figures, 2012 C. Figures; A universal climate change agreement is necessary and possible; Inter Press Service (2012) http://www.ipsnews.net/

- FNS, 2009 FNS (Federal News Service); Remarks by United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon to the World Climate Conference; (2009) Geneva, Switzerland

- FRC, 2010 FRC (Foreign Relations Council); National Security Consequences of U.S. Oil Dependency; (2010) http://www.cfr.org/publication/11683/

- Goldenberg, 2014 S. Goldenberg; Lima climate deal hailed as key first step, but big issues stay unresolved: talks yield proposal for all nations to cut emissions campaigners say plan is too weak to peg warming; The Guardian (2014)

- Golub, 1998 J. Golub; Global Competition and EU Environmental Policy; Routledge, New York (1998)

- Goodell, 2014 J. Goodell; Obamas climate challenge; Rolling Stone (2014), pp. 41–45

- Harvey, 2014 F. Harvey; Climate talks end with partial emissions deal; The Guardian (2014) 25 November

- Hasenclever et al., 1996 A. Hasenclever, P. Mayer, V. Rittberger; Interest, power, knowledge: the study of international regimes; Mershon Int. Stud. Rev., 40 (1996), pp. 177–228

- Homer-Dixon, 1999 T. Homer-Dixon; Environment, Scarcity, and Violence; Princeton University Press, Princeton (1999)

- JRC, 2012 JRC (Joint Research Center); Trends in Global CO2 Emsion: 2012 Report ; PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (2012) http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/PBL_2012_Trends_in_global_CO2_emissions.pdf

- Kaul et al., 1999 I. Kaul, I. Grunberg, M.A. Stern; Global Public Goods: International Cooperation in the 21st Century. New York; (1999), pp. 48–56

- Kennedy, 1968 P. Kennedy; The Re and Fall of the Great Powers; Vintage (1968), pp. 9–12

- Keohane, 1984 R.O. Keohane; After Hegemony; Princeton University Press, Princeton (1984)

- Kim, 1992 S.S. Kim; International organizations in Chinese foreign policy; Annals (1992)

- Kumar, 2015 S. Kumar; Gloomy climate at Doha; Bus. Line Hindu (2015)

- McDonald, 2013 F. McDonald; Climate deal reached in Warsaw but critics say it is too weak in face of crisis; Ir. Times (2013) December 15

- Modelski, 1987 K.G. Modelski; Long Cycles in World Politics; University of Washington Press, Seattle (1987)

- Olson, 1965 M. Olson; The Logic of Collective Action; Harvard University Press, Cambridge (1965)

- Paul, 2013 B. Paul; Last-Minute Deal at UN Climate Talks; FARS News Agency (2013), p. 23

- Porter, 1990 M. Porter; The Competitive Advantage of Nations; Free Press, New York (1990)

- Revkin, 2014 A.C. Revkin; In climate talks, soft is the new hard – and thats a good thing; Ir. Times (2014) December 14

- Risse-Kappen, 1995 T. Risse-Kappen; Bringing Transnational relations back; Non-state Actors, Domestic Structures and International Institutions, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1995)

- Roberts and Edwards, 2012 T. Roberts, G. Edwards; A New Latin American Climate Negotiating Group: the Greenest Shoots in the Doha Desert; Brookings (2012) http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/up-front/posts/2012/12/12-latin-america-climate-roberts

- Rosenau and Czempiel, 1992 J.N. Rosenau, E.O. Czempiel; Governance without Government: Order and Change in World; Cambridge University Press, New York (1992)

- Sanders, 2002 R. Sanders; Prospect for Sustainable Development in the Chinese Countryside: the Political Economy of Chinese, Ecological Agriculture; Ashaate Publishing Limited, England (2002)

- Sethi, 2012 N. Sethi; India worried over consensus being buried in climate talks; Times India Pune Ed. (2012)

- Stern, 2006 N. Stern; Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change; (2006) http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/independent_reviews/stern_review_economics_climate_change/sternreview_index.cfm

- Stone, 1993 C.D. Stone; Defending the global commons; Philippe Sands (Ed.), Greening International Law, Earthscan Ltd (1993), p. 36

- TBM, 2014 TBM (The Border Mail); Last-Minute Deal Avoids a Daster; (2014)

- UNFCCC, 2014 UNFCCC; INDCs as Communicated by Parties; (2014) http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/indc/Submission%20Pages/submissions.aspx

- Yergin, 2006 D. Yergin; Ensuring energy security; Foreign Aff. (2006), pp. 69–77

Document information

Published on 15/05/17

Submitted on 15/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?