Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

The new training context in higher education is moving toward a new model of massive, open and free education through a methodology based on video simulation and students’ collaborative work. Using a descriptive methodology, we analyze the formats and Web content presentation of 72 journals indexed in the Journal Citation Reports® (2013) in the field of communication, and their presence in the development of massive open online courses (MOOCs) at the leading global platform, «Coursera». The findings show that the vast majority of scientific journals in the field of communication offer few disclosure formats and are difficult to embed in new massive, ubiquitous and collaborative movements which use the selfcreated «audiovisual pill». Therefore, the integration of articles of international scientific journals in MOOCs is almost nonexistent. Journals are not taking advantage of the great potential of these courses for scientific divulgation, probably because its unique disclosure format is written text. Thus, we propose a new model for scientific publication which shares writing text format with the video article, social media outreach and new formats supported by mobile digital devices to foster greater international visibility of scientific development and social progress in an everyday, more interconnected and visual society.

1. Introduction

The current training scenarios in higher education are moving toward a new format that combines three basic principles: free-of-charge, massive and ubiquity (Cormier & Siemens, 2010; Berman, 2012; Boxall, 2012). These three principles are materializing with the acronym MOOCs (massive open online courses). The development of these courses, extended worldwide by their philosophy, opens a new concept of education and training and also a giant door to the scientific world (Anderson & Dron, 2011; Rodríguez, 2012; Regalado, 2012). This new type of formative macro-scenario stems from the philosophy of «open learning movement» which is based on four fundamental principles: redistribute, rework, revise and reuse (Cafolla, 2006; OECD, 2007; Bates & Sangra, 2011; Dezuanni & Monroy, 2012).

The presence of international refereed journals indexed in the most prestigious databases, such as Journal Citation Reports, Scopus or ERIH, perform a kind of academic scientific divulgation, exclusively in writing format, and this hinders its appearance in MOOCs, based on a video-simulation methodology with the format of «audiovisual pill» (Kukulska-Hulme & Traxler, 2007; Özdamar & Metcalf, 2011). From these new social, training and educational parameters, scientific disclosure should be positioned in a free movement to integrate new access formats and content creation to allow an effective divulgation of their contributions in the new training scenarios. This new scientific divulgation should be characterized by audiovisual and social content presentation, which opens massive international dissemination opportunities for authors and journals. For the development of these proposals, the scientific journal should advance on their reporting processes to combine traditional methods based on written format with interactive presentation in the form of video article and integrating within it the major contributions presented and developed in the written article. In this paper, we present a descriptive study in which we analyze the content presentation format, Web pages, and platform capabilities of the 72 journals in the field of communication indexed in the Journal Citation Reports and their presence in MOOCs offered by the most important global platform today, «Coursera». As a result of the study, we also discuss possible new forms of social and scientific divulgation grounded in the new mobile digital devices.

1.1. MOOC characteristics and their implications for the scientific journal

The MOOCs based on network distributed learning are based on connectivism theory and on its learning model. The MOOCs have been rated as «Direct to Student» by the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (Eaton, 2012; Boxall, 2012; Berman, 2012) and considered the most significant educational innovation in 2012 (Khan, 2012). The main reason for this consideration has been produced by the break in the hierarchical system of higher education. Instead of offering an elite education to a few college students (Harvard, Stanford, etc.), this new training system offers massive free training from two principles: ubiquity and collaboration among students. What really distinguishes these new training scenarios is the opportunity to access a free training and be taught, in many cases, by renowned professors (Fombona & al., 2011; Young, 2012; Vázquez, 2012). The germ that sparked this new idea was born in Stanford University with an initiative called «Stanford’s Al Course» which resulted in three methodological approaches in the open education movement based on networks, tasks and content (Traxler, 2009; Ynoue, 2010).

The MOOCs based on network distributed learning are based on connectivism theory and on its learning model (Siemens, 2005; Ravenscroft, 2011). In these courses, the content is minimal, and the fundamental principle is network learning in an adequate context –from learner autonomy– to seek, create, and share information with the rest in a «node» of shared learning (Sevillano & Quicios, 2012). One theory is currently being questioned, but it serves to establish a starting point of learning from distributed nodes using the principles of autonomy, connectivity, diversity, collaboration, and openness (Downes, 2012). A model where traditional evaluation becomes very hard and learning focuses primarily on the acquisition of skills developed through social network conversations and contributions made by its members.

The MOOCs based on tasks are founded on students’ skills in solving certain types of work (Winters, 2007; Cormier & Siemens, 2010). The learning is distributed in different formats, but there are a number of tasks that is compulsory to solve. Some tasks are able to be solved by many ways, but the student has to pass them to acquire new skills and be promoted to other modules. What really matters is student progress through different jobs (or projects). Such MOOCs are developed from a mixture of instruction and constructivism (Laurillard, 2007; Bell, 2011).

The content-based MOOCs present a series of automated tests and have great media coverage (Rodríguez, 2012). They are based on content acquisition system with an assessment model very similar to traditional classes (standardized tests and self-assessed). Their appeal comes from the participation of universities’ renowned professors. The major problem with this type of MOOCs is the massive student treatment (without any individualization) and the teaching assessment based on a trial-and-error system already overcome.

These three types of MOOCs are grouped into two classifications: cMOOCs and xMOOCs (Downes, 2012). The first ones are based on network learning and tasks, and the second ones, based on content. The most widely developed –xMOOCs– promote a teaching methodology focused on video-simulation, autonomous learning, and collaborative and (self-) evaluation. Their key features are as follows.

• Free access with no limit on the number of participants.

• No free certification for participants.

• Instructional design based on the audiovisual content with support of written text.

• Collaborative and participatory methodology with minimal teacher intervention.

Current research considers that this new type of format still requires a more elaborate pedagogical architecture to actively promote self-organization, connectivity, diversity, and decentralized control processes of teaching and learning (deWaard & al., 2011; Baggaley, 2011). Therefore, these emerging training systems must overcome many shortcomings for a sustainable future construction, such as the economic management of the participating institutions, the accreditation of the education, monitoring of training, and authentication of students (Eaton, 2012; Hill, 2012). Alongside these deficiencies, they also have to face imminently a number of challenges:

• The content, conversations, and interaction dispersion; a dispersion is part of the essence of the MOOC, but it is needed to be organized and facilitated to the participants. The MOOC needs «content curators» (one who seeks, collects, and shares information continuously), automating and optimizing resources but keeping in mind that it is the students who must also filter, aggregate, and enrich the course with their participation.

• The lack of certification in some of them, which should lead to more innovative and flexible accreditation models of knowledge and adapted to the needs of a constantly evolving labor market. In this sense, the «badges» (representation of a skill or accomplishment, as an iconographic identification) can be an interesting item to test.

• The design of activities should face reflection on their own practice and instruction for the acquisition of new skills, rather than memorization of theoretical contents.

• Learning in a MOOC requires not only a certain level of participants’ digital competence but also a high level of autonomy in learning, which is not always present in all the students.

• The integration of higher quality audiovisual content with reference in the scientific world, where video article would have greater penetration.

Everyone is aware that the mass movement objectives are not only based on altruism. Performing MOOCs enables free, quality, and global training, but accreditation is not always guaranteed (Eaton, 2012). The business is established in that accreditation, which requires a parallel evaluation to the free one. The overcoming of this assessment and the corresponding payment –n most cases– certifies the training. In this business model, the scientific journal, whose financial difficulties are well known to the international scientific community, has an opportunity for funding with its participation in the accreditation of courses in which they participate with their content. In turn, the MOOC organizers and course developers save their own production and give higher quality to the content provided on their platform as they come backed by the quality of the journal, its position in international databases, and the blind peer review process that ensures anonymity and quality of the scientific contributions. However, to materialize this process, the journal should move toward new disclosure formats more suited to the digital society and the principles of portability and ubiquity of these digital training environments (Aguaded, 2012; Area & Ribeiro, 2012). We can talk about a new era of knowledge: the «visual thinking» (Pérez-Rodríguez, Fandos & Aguaded, 2009).

2. Method

The method used in this research is descriptive of censal and quantitative character. The research aims to analyze two objectives:

• To test out digital formats of disclosure and interactive possibilities offered by the Web pages of JCR journals in the field of communication using a rubric of analysis.

• To analyze quantitatively the learning resources of 67 «Coursera» MOOCs related to the fields of communication, education, and humanities. The analysis aims to quantify the frequency of articles presented in these courses corresponding to communication journals indexed in the Journal Citation Reports.

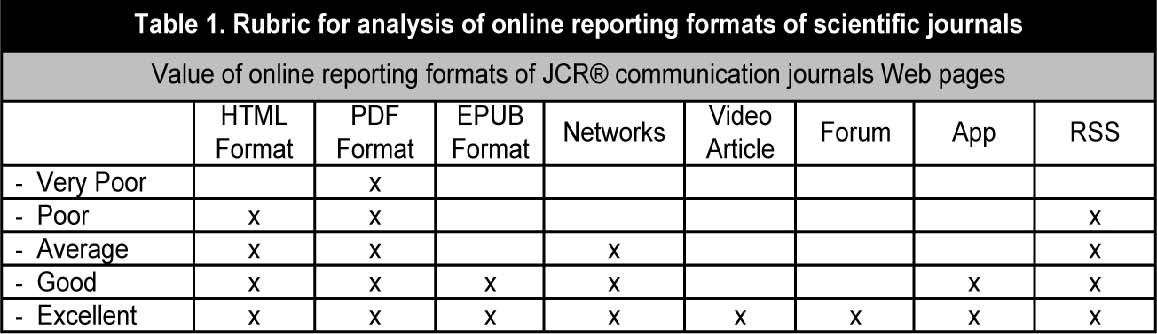

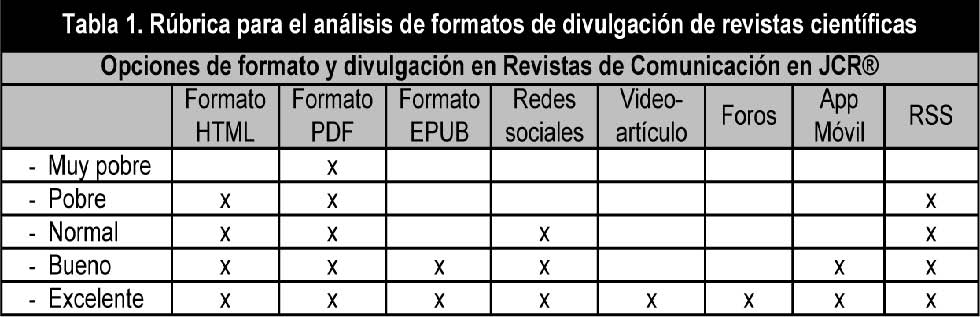

For the first dimension, we developed and used the rubric of analysis (table 1) to analyze the Web pages of scientific journals with five quality levels (1: Very Poor, 2: Poor, 3: Average, 4: Good, and 5: Excellent) depending on formats, capabilities, and interactive possibilities offered. This classification was based on the results of the research project I+D+I (Ministry of Education: Research+Development+ Innovation Project with public funding), in which researchers have been rated the value of online reporting formats of Web pages to promote ubiquity and interactivity.

For the second dimension, we conducted a descriptive study of largest globally MOOC platform, «Coursera». The platform was founded by Daphne Koller and Andrew Ng, professors at Stanford University and obtained a funding of more than $25 million, and 37 universities worldwide are involved, offering over 200 courses grouped into 20 branches of knowledge. Today, there have been conducting courses for more than three million students, representing twice Spanish university students enrolled in 2012. For this study, we selected the four branches of knowledge offered in «Coursera» more related to the field of communication. We proceeded to pre-enroll in 67 courses to analyze the characteristics and materials (mandatory and optional) in the development of each course. We perform a quantitative study to show the frequency of occurrence of different reporting formats used in its development.

3. Results & analysis

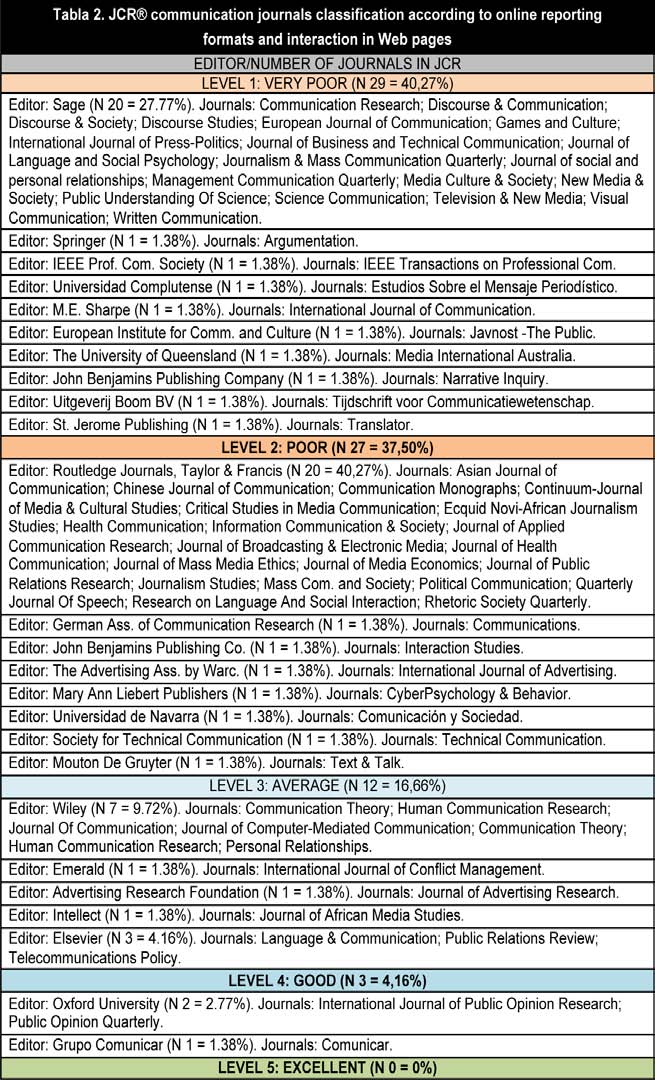

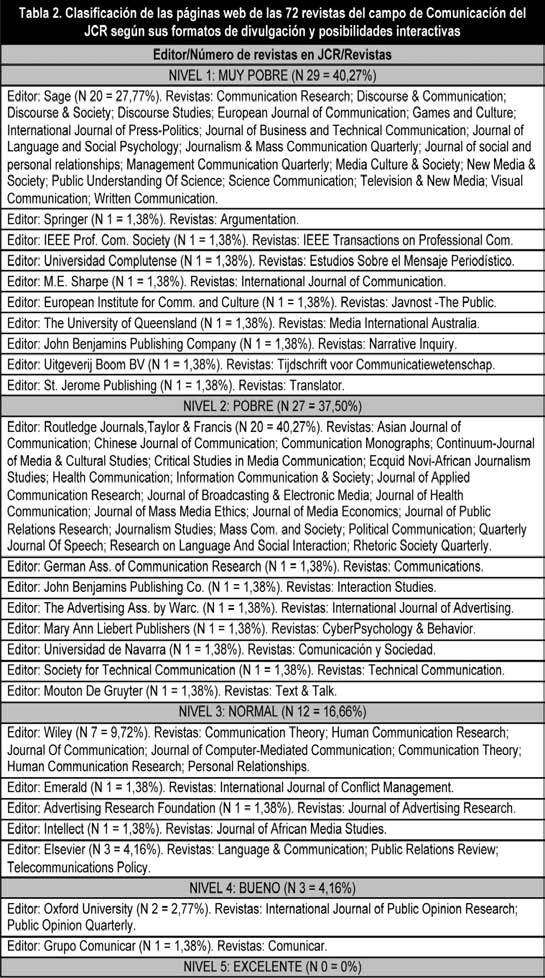

The application of the rubric of analysis to analyze Web sites and reporting formats are shown in table 2 according to the standards established in the project. For its development, we proceeded to identify the editor and journal name by the partial percentage they represent of the total indexed JCR journals in the field of communication.

The results most notable of this classification can be specified in the following items:

• The percentage of journals that are qualified with low levels 1 and 2 is very high (N 57 = 77.77%), with few formats available and with little interactivity in social networks.

• It is noteworthy that one of the editors with the highest percentage of journals in the JCR «Sage» (20 journals in communication area) allows only the articles in HTML and PDF format and tracking numbers using RSS Feeds.

• The number of journals that can be considered as «good» are only three, which represents a small percentage of 4.16%. These journals are the ones that provide more interactive possibilities: «Comunicar» published by Group Comunicar, whose Editor-in-Chief is José Ignacio Aguaded, professor at the University of Huelva, that offers on its Web site different reading format for mobile digital devices (Epub) and complementary audiovisual material, and the journals «International Journal of Public Opinion Research» and «Public Opinion Quarterly» published by Oxford journals and whose editors-in-chief are Claes de Vreese (University of Amsterdam), James N. Druckman (Northwestern University), and Nancy A. Mathiowetz (University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee) that provide the possibility to display digital format in mobile devices (smartphone, tablet, etc.).

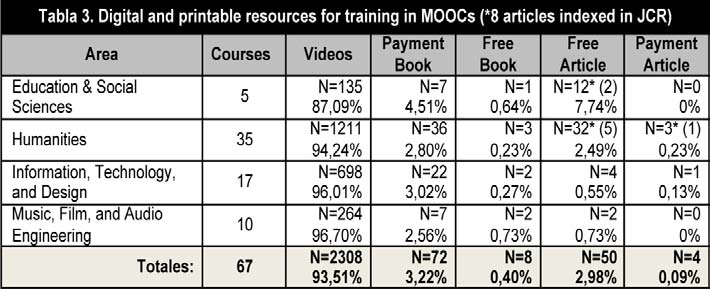

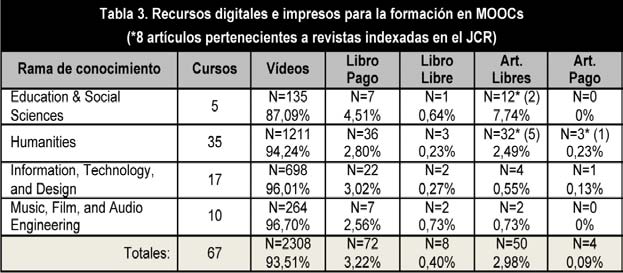

The results of the second dimension «Presence of the Communication journals in MOOCs» can be viewed in table 3, where we can find reporting formats employed and classified by type: videos, payment books, free books, free, and payment articles (we identified with symbol * articles indexed in JCR journals).

We can infer a number of considerations from the analysis of the data presented in table 3, among which, we highlight the following:

• The audiovisual pill between 5 and 15 minutes in video format is the most widely used learning resource in MOOCs (N 2308 = 93,51%).

• The percentage of both free and payment article is very low, and it does not represent more than 3.5% of total resources used in MOOCs.

• The percentage of articles belonging to journals indexed in the JCR is only 0.32%.

• The payment book (primarily offered online at Amazon Library) is the second most used resource but in a much lower percentage to the videos.

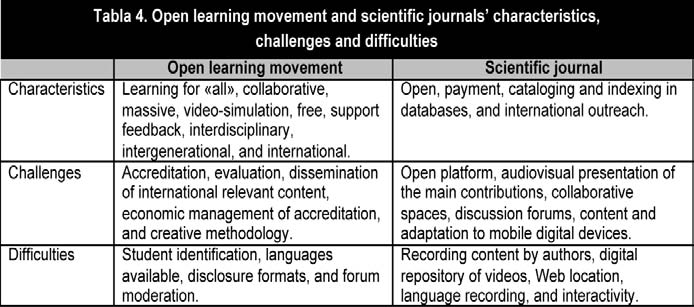

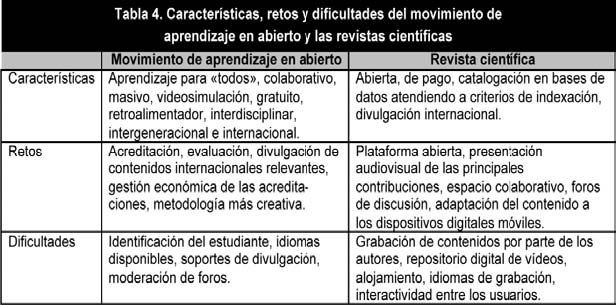

We believe that these new learning contexts can serve as a starting point for many scientific journals to redefine its international position and open up new disclosure formats and obtain new financial opportunities. Scientific journals, offering open and payment article, should take advantage of this new scenario to reorganize its communication processes, facing new forms of scientific divulgation. In this scenario, the videoarticle constitutes one of the formats with highest potential, but today, no journal in the field of communication offers it on their pages or Web platforms. In table 4, we summarize the characteristics, challenges, and difficulties of the journal within the new macro scenario of open learning movement.

4. Toward new disclosure forms in scientific journals

The international scientific journals with high impact factors and indexed in renowned databases have an opportunity to redefine their processes of scientific disclosure and incorporate new media formats that can be projected on several devices from the principles of ubiquity and portability. To do this, the platforms and Web sites that offer journals’ content should be rearranged to make them learning digital platforms and not just repositories of published articles. Our proposal consists of a journal platform that integrates, among other possibilities, the following features:

• Videoarticle: video presentation and explanation of the articles by the authors. A «videopill» from 5-15 minutes. Free access with license «creative commons» even in journals with format «pay per view».

• Academic forum: a discussion of the findings and methods used in each article by other researchers would be a new form of scientific reflection.

• Scientific chat: open to ideas and dissemination of registered researchers.

• Audiovisual monographs: the creation of audiovisual monographs could be associated to MOOCs, and in future, to the development of thematic courses.

• Youtube channel: a journal channel with their own themes and videos.

• Mobile APP: journals need to be adapted to mobile paging, e-reader, smartphone, and tablet. Thus, the journal and its production are fully visible and with quality in any digital device, which promotes the portability and ubiquity.

• Accessing video articles in scientific or general social networks and creating a specific account on Twitter for wider dissemination of scientific activity.

These platforms would represent a qualitative step of great importance to scientific journals. The video article finds in them the main disclosure format in conjunction with the written format. For its development, it should take into account some basic performance criteria (Ynoue, 2010; del-Casar & Herradon, 2011):

1) Duration of no more than 10-15 minutes. It is believed that this time is a good compromise that allows to develop the main parts of a scientific paper: introduction, theoretical framework, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusions.

2) High-intermediate level of technical content. The video article is a complement to the written format, containing all technical information, especially the research methodology. The video article must find a balance between lively exposure and scientific rigor in every idea, that it may be useful to the largest possible interested audience. A superficial treatment would provide very little educational value, and a very deep development could hinder its following in the training process.

3) Enhance the visual aspects as opposed to formal ones. This means that the process of developing ideas, even taking a deep mathematical support, will be projected through pictures appoggiatura (both real and animations), introducing the mathematical formulation only when it is absolutely necessary.

4) Use of digital speech by speech synthesis. There are two basic reasons that justify the adoption of this standard. The first one is practical, it is easier to adjust the length of the text to the evolution of the images than if it is done by a more conventional analogical system. Furthermore, if necessary, it is simpler to reedit and modify a text fragment and incorporate to the video again using this technology (it can be done in few minutes) than perform a real face recording with a microphone (trying to maintain the same voice, reading speed, etc.) and then incorporate it again with the exact duration and at the precise point of the video matrix. The last option also requires more infrastructure and editing time. Fortunately, the state of digital voice synthesis allows a voice with an acceptable expression and practically no «robotic» effect. It also allows a language conversion very functional to enhance international dissemination of articles and possible integration into MOOCs in different languages.

5) Dissemination via YouTube® platform. We have chosen this site as the Web location more adequate to spread and share the material created. Although other alternatives can be proposed (Moodle Web site of the journal, social networks, etc.), we consider that by capacity, image quality (up to 1920 × 1080 pixels maximum), and audio offered (AAC encoding with two channels at 44.1 kHz), global impact and capacity for online edition (to generate dynamic links among related videos) are the most appropriate channel for divulgation of video articles and their possible integration into MOOC educational experience.

5. Conclusions

The new MOOCs are meaning a new global way of training and a great opportunity to disseminate worldwide scientific production. In this paper, we have analyzed the incidence of written format (books and articles) in the development of MOOCs related to the communication field. The descriptive analysis shows how books or articles in written format have a very low incidence in these courses. Instead, video is the preferred reporting format because it uses a more dynamic, fun, and visual format. We have also analyzed and classified disclosure formats, features, and interactive capabilities of the platforms and Web sites of the 72 journals in the field of communication indexed in the Journal Citation Reports to analyze their compatibility with the new media and ways to access the information. The study concludes that the vast majority of journals related to the field of communication offer few disclosure formats and opportunities for interaction, making it difficult to position them in the digital world. Thus, the classification of the 72 journals in the field of communication indexed in JCR journals shows only three (4.16%): «Comunicar» (edited by Group Comunicar in Spain), «International Journal of Public Opinion Research» and «Public Opinion Quarterly» (edited by Oxford Journals) are positioned in appropriate quality criteria to meet a scientific divulgation in line with current technological principles. This should provoke a reflection about a change in scientific publication toward formats that enhance the classic written article with other media formats that encourage interactivity, ubiquity, portability, and integration into the new formats of higher education training.

These scenarios dominated by visual methods require resources like video article that converted into a « scientific pill», and also, an «educational pill» has many possibilities for disclosure in open courses, in university educational platforms, as part of curriculum of different subjects and also can be a powerful claim for the international divulgation of the journal. Furthermore, if scientific journal advances in formats and resources adapted to the new digital mobile devices (smartphones, tablets, etc.) and incorporates new forms of collaboration and interaction in social networks, promoting the development of new audiovisual channels, it will adopt a role partner and modifier of scientific thinking in the information society, and the informative dimension of scientific thought will acquire greater international relevance.

6. Prospective

The field of MOOCs is a new area of development that is constantly evolving, and it is beginning to generate new areas of research. The Erasmus consortium is designing a large multilingual portal from over 4000 member institutions to disseminate massive courses, and it is scheduled to start by 2014. The aim is not only to offer courses but interconnect knowledge, research, and transfer of results between universities and where the ubiquitous and mobile audiovisual format will be a priority.

Notes

1 Web sites JCR journals Rubric of analysis has been developed and evaluated by the researchers that make up the project I+D+I outlined in the section of «acknowledgments».

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the Spanish Ministry of Education and it is part of a research, development and innovation project entitled: Ubiquitous Learning with mobile devices: design and development of a map of higher education responsibilities. EDU2010-17420-Sub EDUC.

References

Aguaded, J.I. (2012). Apuesta de la ONU por una educación y alfabetización mediáticas. Comunicar, 38, 7-8. (DOI:10.3916/C38-2012-01-01).

Anderson, T. & Dron, J. (2011). Three Generations of Distance Education Pedagogy. The International Review in Open & Distance Learning, 12 (3).

Area, M. & Ribeiro, M.T. (2012). De lo sólido a lo líquido: Las nuevas alfabetizaciones ante los cambios culturales de la Web 2.0. Comunicar, 38, 13-20. (DOI: 10.3916/C38-2012-02-01).

Baggaley, J. (2011). Harmonising Global Education: from Genghis Khan to Facebook. London and New York, Routledge.

Bates, A.W. & Sangrá, A. (2011). Managing Technology in Higher Education: Strategies for Transforming Teaching and Learning. Somerset: Wiley.

Bell, F. (2011). Connectivism: Its Place in Theory-informed Research and Innovation in Technology-enabled Learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12 (3).

Berman, D. (2012). In the Future, Who Will Need Teachers? The Wall Street Journal, October 23.

Boxall, M. (2012). MOOCs: A Massive Opportunity for Higher Education, or Digital Hype? The Guardian Higher Education Network, August 8.

Cafolla, R. (2006). Project Merlot: Bringing Peer Review to Web-Based Educational Resources. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 14 (1), 313-323.

Cormier, D. & Siemens, G. (2010). Through the Open Door: Open Courses as Research, Learning & Engagement. Educause Review, 45 (4), 30-39.

Del Casar, M.A. & Herradón, R. (2011). El vídeo didáctico como soporte para un b-learning sostenible. Arbor Ciencia, Pensamiento y Cultura, 187 (3), 237-242.

Dewaard, I. & al. (2011). Using mLearning and MOOCs to Understand Chaos, Emergence, and Complexity in Education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12 (7).

Dezuanni, M. & Monroy, A. (2012). Prosumidores interculturales: la creación de medios digitales globales entre los jóvenes. Comunicar, 38, 59-66. (DOI:10.3916/C38-2012-02-06).

Downes, S. (2012). The rise of MOOCs. (www.downes.ca/post/57911) (01-01-2013).

Eaton, J. (2012). MOOCs and Accreditation: Focus on the Quality of «Direct-to-Students». Education Council for Higher Education Accreditation, 9 (1).

Fombona, J., Pascual M.A., Iribarren, J.F. & Pando, P. (2011). Transparent Institutions. The Journal of Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics (JSCI), 9, (2), 13-16.

Hill, P. (2012). Four Barriers that MOOCs must Overcome to Build a Sustainable Model. E-Literate. (http://mfeldstein.com/four-barriers-that-moocs-must-overcome-to-become-sustainable-model/) (01/12/2012)

Khan, S. (2012). One World Schoolhouse: Education Reimagined. New York: Twelve Publishing.

Kukulska-Hulme, A. & Traxler, J. (2007). Designing for Mobile and Wireless Learning. In H. Beetham & R. Sharpe (Eds.), Rethinking Pedagogy for a Digital Age (pp. 183-192). New York: Routledge.

Laurillard, D. (2007). Pedagogical forms for Mobile Learning. In N. Pachler (Ed.), Mobile Learning: Towards a Research Agenda (pp. 153-175). London: WLE Centre, IoE.

OECD-Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (2007). Giving Knowledge for Free: The Emergence of Open Educational Resources. SourceOECD Education & Skills, 3.

Pérez-Rodríguez, M.A., Fandos, M. & Aguaded, J.I. (2009). ¿Tiene sentido la educación en medios en un mundo globalizado? Cuestiones Pedagógicas, 19, 301-317.

Ravenscroft, A. (2011). Dialogue and connectivism: A New Approach to Understanding and Promoting Dialogue-rich Networked Learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12 (3).

Regalado, A. (2012). The Most Important Education Technology in 200 Years. MIT Technology Review, November 2012.

Rodríguez, C.O. (2012). MOOCs and the AI-Stanford like Courses: Two Successful and Distinct Course Formats for Massive Open Online Courses. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 1.

Sevillano, M.L. & Quicios, M.P. (2012). Indicadores del uso de competencias in-formáticas entre estudiantes universitarios. Implicaciones formativas y sociales. Teoría de la Educación. 24, 1; 151-182.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age. Interna-tional Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2 (1).

Traxler, J. (2009). The evolution of mobile learning. In R. Guy (Ed.), The Evolution of Mobile Teaching and Learning (pp. 1-14). Santa Rosa, CA: Informing Science Press.

Vázquez, E. (2012). Mobile Learning with Twitter to Improve Linguistic Competence at Secondary Schools. The New Educational Review, 29 (3), 134-147.

Winters, N. (2007). What is Mobile Learning? In M. Sharples (Ed.), Big Issues in Mobile Learning (pp. 7-11). Nottingham, UK: LSRI, University of Nottingham.

Ynoue, Y. (2010). Cases on Online and Blended Learning Technologies in Higher Education-Concepts and Practices. New York: Editorial Information Science Ref-erence.

Young, J. (2012). Inside the Coursera Contract: How an Upstart Company Might Profit from Free Courses. The Chronicle of Higher Education. July 19.

Özdamar, N., & Metcalf, D. (2011). The Current Perspectives, Theories and Practices of Mobile Learning. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 10, 2, 202-208.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Los nuevos escenarios formativos en la educación superior se están orientando hacia un nuevo modelo de formación masiva, abierta y gratuita por medio de una metodología basada en la videosimulación y el trabajo colaborativo del estudiante. En este artículo analizamos a través de un estudio descriptivo los formatos de divulgación y presentación de contenidos de las 72 revistas indexadas del campo de la Comunicación en el Journal Citation Reports® (2013) y su presencia en el desarrollo de cursos online masivos en abierto (MOOCs) en la principal plataforma mundial «Coursera». Las conclusiones muestran que la gran mayoría de revistas científicas del campo de la Comunicación ofrecen pocos formatos de divulgación y poco integrables en los nuevos movimientos masivos, ubicuos y colaborativos que utiliza como recurso principal, la «píldora audiovisual» de creación propia. El posicionamiento de las revistas de reconocido prestigio internacional es casi nulo y no se está aprovechando el gran potencial que estos cursos suponen para la divulgación científica; probablemente debido a que su único formato de divulgación es el texto escrito. Como consecuencia de esta situación, proponemos un nuevo modelo de divulgación científica que comparta el soporte escrito con el videoartículo, la divulgación en redes sociales y la difusión en formatos soportados por dispositivos digitales móviles que favorezcan una mayor visibilidad internacional del avance científico y social de manera más integrada en la sociedad interconectada y visual en la que vivimos.

1. Introducción

Los escenarios formativos actuales en la educación superior se están orientando hacia un nuevo formato que aúna tres principios básicos: gratuidad, masividad y ubicuidad (Cormier & Siemens, 2010; Berman, 2012; Boxall, 2012). Estos tres principios se están materializando en los denominados con la sigla inglesa MOOCs (Cursos Online Masivos en Abierto, en español: COMA). El desarrollo de estos cursos –que por su filosofía se extienden a nivel mundial– abre un nuevo concepto de educación y formación, pero también una puerta gigante a la divulgación científica mundial (Anderson & Dron, 2011; Rodríguez, 2012; Regalado, 2012). Este tipo de nuevo macroescenario formativo parte de la filosofía del «open learning movement» que se fundamenta en cuatro principios fundamentales: redistribuir, reelaborar, revisar y reutilizar (Cafolla, 2006; OECD, 2007; Bates & Sangra, 2011; Dezuanni & Monroy, 2012).

La presencia de revistas de referencia internacional indexadas en las más prestigiosas bases de datos como Journal Citation Reports, Scopus o ERIH realizan un tipo de divulgación científica más academicista en formato exclusivamente escrito, y esto, dificulta su aparición en cursos MOOCs desarrollados en base a una metodología de la videosimulación y en el formato de «píldora audiovisual» (Kukulska-Hulme & Traxler, 2007; Özdamar & Metcalf, 2011). Desde estos nuevos parámetros sociales, formativos y educacionales, la divulgación científica debe posicionarse en un movimiento en abierto que integre los nuevos formatos de acceso y creación de contenido de forma que permita una divulgación efectiva de sus contribuciones en los nuevos escenarios formativos. Esta nueva divulgación científica debe caracterizarse por formatos de presentación audiovisual y social de los contenidos que abran oportunidades de divulgación masiva para las revistas y autores en el ámbito internacional. Para el desarrollo de estas propuestas, la revista científica debe avanzar en sus procesos de divulgación para conjugar los tradicionales métodos de divulgación en formato escrito con la presentación audiovisual en formato de videoartículo de las principales contribuciones presentadas y desarrolladas en el soporte escrito. En este artículo presentamos un estudio descriptivo en el que analizamos el formato de presentación de contenidos y las funcionalidades de las plataformas y páginas web de las 72 revistas del campo de la Comunicación indexadas en el Journal Citation Reports y su presencia en los cursos MOOCs ofrecidos por la plataforma mundial más importante en la actualidad: «Coursera». Como consecuencia del estudio, también analizamos posibles nuevos formatos de divulgación científica y social fundamentados en los nuevos soportes digitales móviles.

1.1. Características de los MOOCs y repercusiones para la revista científica

Los MOOCs han sido calificados como «Direct to Student» por el Council for Higher Education Acreditation (Eaton, 2012; Boxall, 2012; Berman, 2012) y considerados la innovación educativa más significativa del año 2012 (Khan, 2012). La principal razón de esta consideración ha sido la ruptura que han causado en el sistema jerárquico de la enseñanza superior. En lugar de ofrecer una educación de élite a unos pocos estudiantes universitarios (Harvard, Stanford, etc.) este nuevo sistema de formación ofrece formación gratuita masiva desde dos principios: ubicuidad y colaboración entre estudiantes. Lo que realmente caracteriza a estos nuevos escenarios formativos es el atractivo de poder acceder a una formación continua de forma gratuita e impartida por profesores universitarios de reconocido prestigio, en muchos de los casos (Fombona & al., 2011; Young, 2012; Vázquez, 2012). El germen que suscitó esta nueva idea parte de la Universidad de Stanford con la iniciativa denominada «Stanford´s Al Course» que dio lugar a tres enfoques metodológicos del movimiento de educación en abierto basados en: redes, tareas y contenidos (Traxler, 2009; Ynoue, 2010).

Los MOOCs basados en el aprendizaje distribuido en red se fundamentan en la teoría conectivista y en su modelo de aprendizaje (Siemens, 2005; Ravenscroft, 2011). En estos cursos, el contenido es mínimo y el principio fundamental de actuación es el aprendizaje en red en un contexto propicio para que –desde la autonomía del estudiante– se busque información, se cree y se comparta con el resto en un «nodo» de aprendizaje compartido (Sevillano & Quicios, 2012). Una teoría que actualmente se está cuestionando, pero que sirve para establecer un punto de partida del aprendizaje distribuido mediante nodos desde los principios de autonomía, conectividad, diversidad, colaboración y apertura (Downes, 2012). Un modelo donde la evaluación tradicional se hace muy difícil y el aprendizaje fundamentalmente se centra en la adquisición de habilidades adquiridas mediante la red social de conversaciones y aportaciones realizadas por sus integrantes.

Los MOOCs basados en tareas tienen su fundamento en las habilidades del alumnado en la resolución de determinados tipos de trabajo (Winters, 2007; Cormier & Siemens, 2010). El aprendizaje se halla distribuido en diferentes formatos pero hay un cierto número de tareas que son obligatorias realizar para poder seguir avanzando. Unas tareas que tienen la posibilidad de resolverse por muchas vías pero, cuyo carácter obligatorio, impide pasar a nuevos aprendizajes hasta haber adquirido las habilidades previas. Lo realmente importante es el avance del estudiante mediante diferentes trabajos (o proyectos). Este tipo de MOOCs se desarrollan desde una mezcla de instrucción y constructivismo (Laurillard, 2007; Bell, 2011).

Los MOOCs basados en contenidos presentan una serie de pruebas automatizadas y poseen una gran difusión mediática (Rodríguez, 2012). Están basados en la adquisición de contenidos y se fundamentan en un modelo de evaluación muy parecido a las clases tradicionales (con unas pruebas más estandarizadas, autoevaluadas y concretas). Normalmente son llevados a cabo por profesores de universidades de reconocido prestigio; lo que genera su mayor atractivo. El gran problema de este tipo de MOOCs es el tratamiento del alumno de forma masiva (sin ningún tipo de individualización) y el formato metodológico ya superado del ensayo-error en las pruebas de evaluación.

Estos tres tipos de MOOCs se agrupan en dos clasificaciones: cMOOCs y xMOOCs (Downes, 2012). Los primeros con base en el aprendizaje en red y en tareas; y los segundos, basados en contenidos. Los más extendidos –xMOOCs– promueven una metodología docente enfocada hacia la videosimulación, el aprendizaje autónomo, colaborativo y (auto)evaluado. Sus características fundamentales son:

• Gratuidad de acceso sin límite en el número de participantes.

• Ausencia de certificación para los participantes libres.

• Diseño instruccional basado en lo audiovisual con apoyo de texto escrito.

• Metodología colaborativa y participativa del estudiante con mínima intervención del profesorado.

La investigación actual considera que este nuevo tipo de formato todavía precisa de una arquitectura pedagógica más elaborada que promueva activamente la auto-organización, la conectividad, la diversidad y el control descentralizado de los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje (deWaard & al., 2011; Baggaley, 2011). Por lo tanto, estos sistemas incipientes de formación deben superar muchas deficiencias para una construcción futura sostenible, entre las que destacan: la gestión económica de las instituciones participantes, la acreditación de los estudios ofrecidos, el seguimiento de la formación y la autentificación de los estudiantes (Eaton, 2012; Hill, 2012). Junto a estas deficiencias, también deben afrontar de forma inminente una serie de retos:

• La dispersión de contenidos, conversaciones e interacciones, una dispersión que forma parte de la esencia de los MOOCs, pero que es preciso organizar y facilitar a los participantes. Los MOOCs necesitan «content curators» (alguien que busca, agrupa y comparte la información de forma continua), automatizando y optimizando los recursos pero sin olvidar que es el estudiante el que debe también filtrar, agregar y enriquecer con su participación el curso.

• La ausencia de certificación en algunos de ellos, lo que debería conducir a modelos de acreditación de los conocimientos más innovadores, flexibles y adaptados a las necesidades de un mercado laboral en constante evolución y crecimiento. En este sentido, los «badges» (representación de una habilidad o de un logro, a modo de identificación iconográfica) pueden ser una apuesta interesante sobre la que avanzar.

• El diseño de actividades debe estar orientado hacia la reflexión sobre la propia práctica y la instrucción para la adquisición de nuevas competencias, más que a la divulgación y memorización de contenidos.

• El aprendizaje en un MOOCs requiere de los participantes no solo cierto nivel de competencia digital sino también un alto nivel de autonomía en el aprendizaje, que no siempre tiene el estudiante que se acerca a este tipo de cursos.

• La integración de contenidos audiovisuales de mayor calidad y de referencia en el mundo científico, en donde el videoartículo tendría una mayor penetración.

A nadie se le escapa que detrás de un movimiento masivo de formación no todo participa de un deseado altruismo institucional. La realización de cursos MOOCs posibilita una formación gratuita, de calidad y mundial pero no garantiza una acreditación gratuita en su gran mayoría (Eaton, 2012). El negocio se establece en esa acreditación que precisa de una evaluación paralela a la gratuita y cuya superación proporciona, mediante pago (en la mayoría de los casos) la expedición de un título que certifica la formación recibida. En este modelo de negocio la revista científica, cuyas dificultades de financiación son bien conocidas por la comunidad científica internacional, también tienen una oportunidad de financiación al poder participar por sus derechos de autor en la acreditación de los cursos impartidos en los que haya participado con su contenido. A su vez, el organizador y desarrollador de cursos MOOCs se ahorra la producción propia y da mayor calidad a los contenidos proporcionados en su plataforma ya que vienen avalados por la calidad de la revista, su posicionamiento en bases de datos internacionales y el proceso ciego de revisión por pares que garantiza el anonimato y calidad de las contribuciones científicas. Pero para que este proceso se pueda materializar, la revista científica debe dar un paso hacia nuevos formatos de divulgación más acordes con la sociedad digital y los principios de portabilidad y ubicuidad de estos entornos mediales y formativos (Aguaded, 2012; Area & Ribeiro, 2012). Podemos hablar de una nueva era de conocimiento: el «pensamiento visual» (Pérez-Rodríguez, Fandos & Aguaded, 2009).

2. Método

El método empleado en esta investigación es descriptivo-censal y cuantitativo. La investigación pretende un doble objetivo:

• Comprobar cuáles son los formatos digitales de divulgación y las posibilidades interactivas que ofrecen las páginas web de las revistas indexadas en JCR del campo de la Comunicación mediante una rúbrica de análisis.

• Analizar de forma cuantitativa los recursos de aprendizaje de 67 cursos MOOCs de la plataforma «Coursera» relacionados con el área de la Comunicación, la Educación y las Humanidades. El análisis pretende cuantificar la frecuencia de artículos pertenecientes a revistas del campo de la Comunicación indexadas en el Journal Citation Reports presentes en estos cursos.

Para la primera dimensión, presentamos la tabla 1 con la rúbrica de análisis1 desarrollada y empleada para analizar las páginas web de revistas científicas con cinco niveles de calidad (1-Muy Pobre, 2-Pobre, 3-Normal, 4-Bueno y 5-Excelente) dependiendo de los formatos, funcionalidades y posibilidades interactivas ofrecidos. Esta clasificación se ha realizado en base a los resultados de investigación del Proyecto I+D +I en el que se ha clasificado el valor de los formatos de divulgación en línea para el fomento de la ubicuidad e interactividad.

Para la segunda dimensión, realizamos un estudio descriptivo de la plataforma de cursos MOOCs más grande a nivel mundial: «Coursera». La plataforma fue fundada por Daphne Koller y Andrew Ng, profesores de la Universidad de Stanford cuenta con una financiación superior a los 25 millones de dólares, participan en ella 37 universidades de todo el mundo y ofrece más de 200 cursos agrupados en 20 ramas de conocimiento. En la actualidad, se han registrado para la realización de cursos más de tres millones de estudiantes, lo que supone el doble de alumnos universitarios españoles matriculados en 2012. Para este estudio, seleccionamos las 4 ramas de conocimiento ofrecidas en «Coursera» más relacionadas con el campo de la Comunicación. Procedimos a preinscribirnos en los 67 cursos para analizar la ficha de cada curso y los materiales empleados en su desarrollo (obligatorios y opcionales). Para ello, realizamos un estudio cuantitativo para mostrar la frecuencia de aparición de los diferentes formatos de divulgación empleados en su desarrollo.

3. Resultados y análisis

La aplicación de la rúbrica de análisis de las páginas web y sus formatos de divulgación se muestra en la tabla 2 según los niveles de calidad establecidos en la rúbrica de análisis. Para su desarrollo, hemos procedido a identificar el Editor y el nombre de la revista junto al porcentaje parcial que supone sobre el total de las revistas indexadas en JCR en el campo de la Comunicación.

Los datos más reseñables de esta clasificación se pueden concretar en los siguientes puntos:

El porcentaje de revistas que aparecen calificadas con niveles bajos 1 y 2 es muy alto (N 57 = 77,77%) con pocos formatos disponibles y con poca interactividad en redes sociales.

Llama la atención que uno de los editores con mayor porcentaje de revistas en el JCR «Sage» (20 revistas en el campo de la Comunicación) solo permite consultar los artículos en formato HTML y PDF y realizar el seguimiento de los números mediante subscripción RSS.

El número de revistas que pueden ser consideradas como «buenas» son solo tres, lo que representa un escaso porcentaje del 4,16%. Estas revistas son las únicas que ofrecen más posibilidades interactivas: «Comunicar» editada por el Grupo Comunicar, cuyo director es el Catedrático de la Universidad de Huelva, J. Ignacio Aguaded, y que ofrece en su página web el formato para lectura en dispositivos digitales móviles (EPUB) y material audiovisual complementario; y las revistas «International Journal of Public Opinion Research» y «Public Opinion Quarterly» editada por Oxford Journals y dirigidas respectivamente por Claes de Vreese (University of Amsterdam) y James N. Druckman (Northwestern University) y Nancy A. Mathiowetz (University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee) que ofrecen la posibilidad de visualización en formato de dispositivo digital móvil (smartphone, tablet, etc.).

Los resultados de la segunda dimensión «Presencia de la revista científica de Comunicación en MOOCs» se pueden visualizar en la tabla 3, donde podemos encontrar los formatos de divulgación empleados clasificados según su tipología en: vídeos, libros de pago, libros libres, artículos libres y artículos de pago (identificamos con el símbolo * los artículos indexados en revistas JCR).

Del análisis de los datos ofrecidos en la tabla 3, se derivan una serie de consideraciones, entre las que destacamos las siguientes:

• La píldora audiovisual en formato de vídeo de entre 5 y 15 minutos es el recurso formativo más empleado en los MOOCs (N: 2.308= 93,51%).

• El porcentaje de artículo tanto libre como de pago es muy bajo y no representa más de 3,5% del total de recursos utilizados en los MOOCs.

El porcentaje de artículos pertenecientes a revistas indexadas en el JCR es tan solo del 0,32%.

El libro de pago (principalmente ofrecido en línea en la Biblioteca Amazon) es el segundo recurso más utilizado, pero en un porcentaje muy inferior a los vídeos.

Creemos que estos nuevos contextos formativos pueden servir de punto de partida para que muchas revistas científicas redefinan su posicionamiento internacional y abran nuevos campos de divulgación y financiación. Las revistas científicas, que ofrecen artículos en sistema abierto y de pago, deberían aprovechar este nuevo escenario para reorganizar sus procesos de comunicación, afrontando nuevos formatos de divulgación científica. En este escenario el videoartículo constituiría uno de los formatos con mayor potencialidad divulgativa y que ninguna revista del campo de la Comunicación ofrece en sus páginas o plataformas web en la actualidad. En la tabla 4, resumimos las características, retos y dificultades de la revista científica ante el nuevo macroescenario del movimiento de aprendizaje en abierto.

4. Hacia nuevos formatos de divulgación en revistas científicas

Las revistas científicas internacionales con altos índices de impacto e indexadas en prestigiosas bases de datos tienen una oportunidad de redefinir sus procesos de divulgación científica e incorporar nuevos formatos audiovisuales que puedan ser proyectados en varios dispositivos y que participen de los principios de ubicuidad y portabilidad. Para ello, las plataformas y páginas web que ofrecen el contenido de las revistas se deberían reorganizar para convertirlas en plataformas digitales de conocimiento y divulgación científica y no solo en repositorios de los artículos que se editan. La propuesta que realizamos está integrada por una plataforma de revista que integre, entre otras posibles, las siguientes funcionalidades:

• Videoartículo: Presentación y explicación en vídeo de los artículos por parte de los autores. Una «píldora» de vídeo entre 5-15 minutos. Accesible de forma gratuita mediante licencia «Creative Commons» incluso en revistas con formato de «pago por visión».

• Foro académico: La discusión sobre las conclusiones y métodos utilizados en cada artículo por parte de otros investigadores sería una nueva forma de reflexión científica.

• Chat científico: abierto a la participación y difusión de ideas de investigadores registrados.

• Monográfico audiovisual: la elaboración de monográficos audiovisuales podrían asociarse a MOOCs y a la elaboración futura de cursos temáticos.

Canal YouTube: un propio canal de divulgación científica de la revista con sus propias temáticas y vídeos.

• APP móvil: es necesario que las revistas puedan visualizarse en formato de paginación móvil, e-reader, smartphone y tablet. De esta manera, la revista y su producción es plenamente visible y con calidad en cualquier soporte digital, lo que promueve la portabilidad y ubicuidad.

• Visualización de los videoartículos en redes sociales científicas o generales y creación de una cuenta específica en Twitter para una mayor divulgación de la actividad científica.

Estas plataformas supondrían un paso cualitativo de gran importancia para las revistas científicas. El videoartículo encontraría en ellas el principal formato de difusión en conjunción con el formato escrito. Para su desarrollo, habría que tener en cuenta unos criterios de realización básicos (Ynoue, 2010; del-Casar & Herradon, 2011):

1) Duración no superior a 10-15 minutos. Se considera que este tiempo constituye un buen compromiso que permite desarrollar los elementos fundamentales de un artículo científico: introducción, marco teórico, metodología, resultados, discusión y conclusiones.

2) Nivel intermedio-alto de contenido técnico. El videoartículo es un complemento al soporte escrito que contiene toda la información técnica, especialmente de la metodología de la investigación. El videoartículo debe buscar un equilibrio entre amenidad de exposición y rigor científico en cada idea expuesta, al objeto de que pueda resultar útil al mayor público interesado posible. Un tratamiento superficial aportaría muy poco valor pedagógico y un desarrollo muy profundo podría dificultar su seguimiento en el proceso formativo.

3) Potenciar los aspectos visuales frente a los formales. Esto quiere decir que las ideas a transmitir, aun teniendo un profundo soporte matemático, se expondrán mediante el apoyo de imágenes (tanto reales como animaciones) en tanto sea posible, introduciendo solo la formulación matemática cuando sea imprescindible.

4) Utilización de locución mediante síntesis digital de voz. Hay dos razones básicas que justifican la adopción de este criterio. La primera es de naturaleza práctica y técnica, y estriba en que es inconmensurablemente más sencillo adaptar la duración del texto a la evolución de las imágenes que si se hiciese por un sistema analógico más convencional. Además, si fuera necesario resulta más sencillo reeditar y modificar un fragmento de texto e incorporarlo de nuevo al vídeo de partida utilizando esta tecnología (se realiza en cuestión de escasos minutos), que realizar una grabación real frente a un micrófono (intentando mantener el mismo tono de voz, velocidad de lectura, etc.) y después incorporarlo otra vez con la duración exacta y en el punto preciso del vídeo matriz. Esta última opción requiere además mayor infraestructura y tiempo de edición. Afortunadamente el estado del arte en la síntesis digital de voz ha permitido una locución con una aceptable expresividad y prácticamente nulo efecto «robotizado». Además, posibilita una conversión en idiomas muy funcional y económica para potenciar la divulgación internacional de los artículos y su posible integración en cursos MOOCs en diferentes idiomas.

5) Difusión por medio de la plataforma YouTube. Se ha elegido este sitio web como la ubicación más propicia para difundir y compartir el material creado. Aunque se pueden sopesar otras alternativas (Moodle, página web de la propia revista, redes sociales, etc.) se estima que por la capacidad de alojamiento, calidad de imagen (hasta 1920 × 1080 pixeles máximo) y de audio ofrecidos (codificación AAC con dos canales a 44,1 KHz), nivel mundial de difusión y capacidad de edición on-line (para generar enlaces dinámicos entre vídeos relacionados), resulta el medio más idóneo para la divulgación del videoartículo y su posible integración en la experiencia educativa de los MOOCs.

5. Conclusiones

Los nuevos MOOCs están suponiendo una nueva forma de formación de incidencia mundial y una gran oportunidad para divulgar la producción científica mundial. En este artículo hemos analizado la incidencia del soporte escrito (libros y artículos) en el desarrollo de los MOOCs relacionados con el campo de la Comunicación. El análisis descriptivo ha demostrado cómo el formato de libro o artículo en formato escrito tiene una representación muy baja en estos cursos. Por el contrario, el vídeo es el formato de divulgación preferido debido a su carácter más dinámico, ameno y visual. Asimismo, hemos analizado y clasificado los formatos de presentación, funcionalidades y posibilidades interactivas de las plataformas y páginas web de las 72 revistas del campo de la Comunicación indexadas en el Journal Citation Reports para valorar su compatibilidad con los nuevos soportes y formas de acceder a la información. El estudio concluye que la gran mayoría de las revistas relacionadas con el campo de la Comunicación ofrecen muy pocas posibilidades de interacción y de formatos; lo que dificulta su posicionamiento en el mundo digital. Así, la clasificación de las 72 revistas científicas del campo de la Comunicación indexadas en JCR muestra que únicamente tres revistas (4,16%): «Comunicar» (editada por el Grupo Comunicar en España), «International Journal of Public Opinion Research» y «Public Opinion Quarterly» (editadas por Oxford Journals) se encuentran posicionadas en criterios de calidad adecuados para afrontar una divulgación acorde con los principios tecnológicos actuales. Esto debe suscitar una reflexión hacia un cambio en los formatos de divulgación científica que enriquezcan el clásico artículo escrito con otros formatos audiovisuales que fomenten la interactividad, ubicuidad, portabilidad e inserción en los nuevos formatos de formación de la educación superior.

Estos escenarios dominados por la metodología audiovisual precisan de unos recursos como el videoartículo que convertido en «píldora científica» y también «píldora educativa» tiene multitud de posibilidades de divulgación en este tipo de cursos en abierto, en plataformas educativas de universidades como parte integrante del currículo de las diferentes asignaturas y, también, puede convertirse en un poderoso reclamo para la difusión internacional de la revista. Si además la revista científica avanza en los formatos y recursos disponibles adaptados a los nuevos dispositivos digitales móviles (smartphones, tablets, etc.) e incorpora nuevas formas de colaboración e interacción en redes sociales, fomentando el desarrollo de nuevos canales audiovisuales, adoptará un papel de interlocutor y modificador del pensamiento científico en la sociedad de la información y la dimensión divulgativa del pensamiento científico adquirirá una mayor relevancia internacional.

6. Prospectiva

El campo de los MOOCs es un área incipiente de desarrollo que no para de evolucionar y que está empezando a generar nuevas áreas de investigación. El propio consorcio Erasmus está diseñando un gran portal multilingüe entre las más de 4.000 instituciones que lo integran para la difusión de cursos masivos y que tiene previsto su inicio hacia el año 2014. El objetivo no es ofrecer solo cursos sino interconectar el conocimiento, la investigación y la transferencia de resultados entre las universidades y donde el formato audiovisual ubicuo y móvil será uno de los prioritarios.

Notas

1 La rúbrica de análisis de páginas web de las revistas JCR ha sido elaborada y validada por el grupo de investigadores que componen el Proyecto I+D+I reseñado en la sección de «apoyos».

Apoyos

Este trabajo se enmarca en el Proyecto de la Dirección General de Investigación y Gestión del Plan Nacional I+D+I (Aprendizaje ubicuo con dispositivos móviles: elaboración y desarrollo de un mapa de competencias en educación superior) EDU2010-17420-Subprograma EDUC.

Referencias

Aguaded, J.I. (2012). Apuesta de la ONU por una educación y alfabetización mediáticas. Comunicar, 38, 7-8. (DOI:10.3916/C38-2012-01-01).

Anderson, T. & Dron, J. (2011). Three Generations of Distance Education Pedagogy. The International Review in Open & Distance Learning, 12 (3).

Area, M. & Ribeiro, M.T. (2012). De lo sólido a lo líquido: Las nuevas alfabetizaciones ante los cambios culturales de la Web 2.0. Comunicar, 38, 13-20. (DOI: 10.3916/C38-2012-02-01).

Baggaley, J. (2011). Harmonising Global Education: from Genghis Khan to Facebook. London and New York, Routledge.

Bates, A.W. & Sangrá, A. (2011). Managing Technology in Higher Education: Strategies for Transforming Teaching and Learning. Somerset: Wiley.

Bell, F. (2011). Connectivism: Its Place in Theory-informed Research and Innovation in Technology-enabled Learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12 (3).

Berman, D. (2012). In the Future, Who Will Need Teachers? The Wall Street Journal, October 23.

Boxall, M. (2012). MOOCs: A Massive Opportunity for Higher Education, or Digital Hype? The Guardian Higher Education Network, August 8.

Cafolla, R. (2006). Project Merlot: Bringing Peer Review to Web-Based Educational Resources. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 14 (1), 313-323.

Cormier, D. & Siemens, G. (2010). Through the Open Door: Open Courses as Research, Learning & Engagement. Educause Review, 45 (4), 30-39.

Del Casar, M.A. & Herradón, R. (2011). El vídeo didáctico como soporte para un b-learning sostenible. Arbor Ciencia, Pensamiento y Cultura, 187 (3), 237-242.

Dewaard, I. & al. (2011). Using mLearning and MOOCs to Understand Chaos, Emergence, and Complexity in Education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12 (7).

Dezuanni, M. & Monroy, A. (2012). Prosumidores interculturales: la creación de medios digitales globales entre los jóvenes. Comunicar, 38, 59-66. (DOI:10.3916/C38-2012-02-06).

Downes, S. (2012). The rise of MOOCs. (www.downes.ca/post/57911) (01-01-2013).

Eaton, J. (2012). MOOCs and Accreditation: Focus on the Quality of «Direct-to-Students». Education Council for Higher Education Accreditation, 9 (1).

Fombona, J., Pascual M.A., Iribarren, J.F. & Pando, P. (2011). Transparent Institutions. The Journal of Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics (JSCI), 9, (2), 13-16.

Hill, P. (2012). Four Barriers that MOOCs must Overcome to Build a Sustainable Model. E-Literate. (http://mfeldstein.com/four-barriers-that-moocs-must-overcome-to-become-sustainable-model/) (01/12/2012)

Khan, S. (2012). One World Schoolhouse: Education Reimagined. New York: Twelve Publishing.

Kukulska-Hulme, A. & Traxler, J. (2007). Designing for Mobile and Wireless Learning. In H. Beetham & R. Sharpe (Eds.), Rethinking Pedagogy for a Digital Age (pp. 183-192). New York: Routledge.

Laurillard, D. (2007). Pedagogical forms for Mobile Learning. In N. Pachler (Ed.), Mobile Learning: Towards a Research Agenda (pp. 153-175). London: WLE Centre, IoE.

OECD-Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (2007). Giving Knowledge for Free: The Emergence of Open Educational Resources. SourceOECD Education & Skills, 3.

Pérez-Rodríguez, M.A., Fandos, M. & Aguaded, J.I. (2009). ¿Tiene sentido la educación en medios en un mundo globalizado? Cuestiones Pedagógicas, 19, 301-317.

Ravenscroft, A. (2011). Dialogue and connectivism: A New Approach to Understanding and Promoting Dialogue-rich Networked Learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12 (3).

Regalado, A. (2012). The Most Important Education Technology in 200 Years. MIT Technology Review, November 2012.

Rodríguez, C.O. (2012). MOOCs and the AI-Stanford like Courses: Two Successful and Distinct Course Formats for Massive Open Online Courses. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 1.

Sevillano, M.L. & Quicios, M.P. (2012). Indicadores del uso de competencias in-formáticas entre estudiantes universitarios. Implicaciones formativas y sociales. Teoría de la Educación. 24, 1; 151-182.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age. Interna-tional Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2 (1).

Traxler, J. (2009). The evolution of mobile learning. In R. Guy (Ed.), The Evolution of Mobile Teaching and Learning (pp. 1-14). Santa Rosa, CA: Informing Science Press.

Vázquez, E. (2012). Mobile Learning with Twitter to Improve Linguistic Competence at Secondary Schools. The New Educational Review, 29 (3), 134-147.

Winters, N. (2007). What is Mobile Learning? In M. Sharples (Ed.), Big Issues in Mobile Learning (pp. 7-11). Nottingham, UK: LSRI, University of Nottingham.

Ynoue, Y. (2010). Cases on Online and Blended Learning Technologies in Higher Education-Concepts and Practices. New York: Editorial Information Science Ref-erence.

Young, J. (2012). Inside the Coursera Contract: How an Upstart Company Might Profit from Free Courses. The Chronicle of Higher Education. July 19.

Özdamar, N., & Metcalf, D. (2011). The Current Perspectives, Theories and Practices of Mobile Learning. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 10, 2, 202-208.

Document information

Published on 31/05/13

Accepted on 31/05/13

Submitted on 31/05/13

Volume 21, Issue 1, 2013

DOI: 10.3916/C41-2013-08

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?