Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

The growing popularity of social network sites (SNS) is causing concerns about privacy and security, especially with teenagers since they show various forms of unsafe behavior on SNS. Media literacy emerges as a priority, and researchers, teachers, parents and teenagers all point towards the responsibility of the school to educate teens about risks on SNS and to teach youngsters how to use SNS safely. However, existing educational materials are not theoretically grounded, do not tackle all the specific risks that teens might encounter on SNS and lack rigorous outcome evaluations. Additionally, general media education research indicates that although changes in knowledge are often obtained, changes in attitudes and behavior are much more difficult to achieve. Therefore, new educational packages were developed –taking into account instructional guidelines- and a quasi-experimental intervention study was set up to find out whether these materials are effective in changing the awareness, attitudes or the behavior of teenagers on SNS. It was found that all three courses obtained their goal in raising the awareness about the risks tackled in this course. However, no impact was found on attitudes towards the risks, and only a limited impact was found on teenagers’ behavior concerning these risks. Implications are discussed.

1. Introduction

Almost everywhere around the world, teenagers form one of the main user groups of social network sites (SNS). For instance, in July 2012, about one third of the Facebook users in the US, Australia, Brazil and Belgium were under 24 years old (checkfacebook.com). The new generation of participatory network technologies provides individuals with a platform for sophisticated online interaction. Active participation of media audiences has become a core characteristic of the 21st century and therefore the meaning of media literacy has evolved. While it traditionally referred to the ability to analyze and appreciate literature, the focus has been enlarged, and is now this includes interactive exploration of the internet and the critical use of social media and social network sites is shortened everywhere else. Livingstone (2004a) therefore describes media literacy in terms of four skills, as the ability to access, analyse, evaluate and create messages across a variety of contexts. It has been found that while children are good at accessing and finding things on the internet, they are not as good in avoiding some of the risks posed to them by the internet (Livingstone, 2004b).

1.1. Risks on SNS

The categories of risks teenagers face on a SNS, are broadly the same as those they face on the internet in general, summarized by De Moor and colleagues (2008). There are three different categories of risks. The first one describes the content risks. A typical example of provocative content teenagers might come across on SNS are hate-messages. These messages can be quite direct, like in an aggressive status-update or post on someone’s wall, but they can also be indirect, e.g. by joining hate groups. Teenagers also need to develop critical skills, to judge the reliability of information. The wrong information that might appear on SNS can be intentional, such as gossip posted by other users, or unintentional. The latter can happen when someone posts a joke that can be misunderstood as real information. Typical examples are articles out of satirical journals, posted on a social network site wall.

The second category of risks includes contact risks, that is risks that find their source in the fact that SNS can be used to communicate and have contact with others (Lange, 2007). Next to instant messaging, SNS are the most popular media used for cyberbullying (Livingstone, Haddon, Görzig & Olafsson, 2011), by using the chat-function, by posting hurtful messages on ones profile or by starting hateful group pages. Additionally, they can also be used for sexual solicitation, as is seen in the process of grooming, where an adult with sexual intentions manages to establish a relationship with a minor by using the internet (Choo, 2009). Moreover, users face privacy risks, since they post a lot of personal information online (Almansa, Fonseca & Castillo, 2013; Livingstone & al., 2011). Additionally, 29% of the teens sustain a public profile or do not know about their privacy settings and 28% opt for partially private settings so that friends-of-friends can see their page (Livingstone & al., 2011).

The third category of risks contains the commercial risks. These include the commercial misuse of personal data. Information can be shared with third companies via applications, and user behavior can be tracked in order to provide targeted advertisements and social advertisement (Debatin, Lovejoy, Horn & Hughes, 2009).

All these risks form a threat, since research indicates that exposure to online risks causes harm and negative experiences in a significant amount of cases (Livingstone e.a., 2011; Mcgivern & Noret, 2011). Internet harassment is seen as a significant public health issue, with aggressors facing multiple psychosocial challenges including poor parent-child relationships, substance use, and delinquency (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2004). Furthermore, some theories predict that young teenagers are less likely to recognize the risks and future consequences of their decisions (Lewis, 1981). Additionally, it was found that they have a harder time controlling their impulses and have higher thrill seeking and disinhibition scores than adults (Cauffman & Steinberg, 2000). This could increase risk taking by teens (Gruber, 2001), especially since posting pictures and interests helps in building and revealing one’s identity (Hum & al., 2011; Lange, 2007; Liu, 2007).

1.2. The role of school education

Many authors emphasized the role of school education in raising awareness about these online risks (Patchin & Hinduja, 2010; Tejedor & Pulido, 2012). Schools appear to be ideally placed for online safety education, since they reach almost all the teenagers at the same time (Safer Internet Programme, 2009), making positive peer influences possible (Christofides, Muise & Desmarais, 2012). However, while the topic of online safety has been formally included in school curricula, the implementation is inconsistent (Safer Internet Programme, 2009) and although a variety of educational packages about safety on SNS has been developed (e.g., Insafe, 2014), most of the packages focus on Internet safety in general, and therefore lack focus on some of the specific risks that accompany the use of SNS (e.g., social advertising, impact of hate-messages and selling of personal data to third companies). The packages that focus on risks on SNS, do not tackle all of the above mentioned categories of risks, but often focus on privacy risks, cyberbullying or ‘wrong information’ (Del Rey, Casas & Ortega, 2012; Vanderhoven, Schellens & Valcke, 2014). Additionally, there often is no theoretical base for the materials, nor any outcome evaluation (Mishna, Cook, Saini, Wu & MacFadden, 2010; Vanderhoven & al., 2014). Indeed, very few studies are set up to evaluate the impact of online safety programs, making use of a control group and a quantitative data collection approach (Del Rey, Casas & Ortega, 2012).

It should be noted that quantitative intervention studies in the field of general media literacy education typically only find that interventions increase knowledge about the specific topic of the course (Martens, 2010; Mishna & al., 2010), while media literacy programs often aim to change attitudes and behavior as well. Nevertheless, attitudes and behavior are commonly not measured and if measured, changes are often not found (Cantor & Wilson, 2003; Duran e.a., 2008; Mishna & al., 2010).

Still, when it comes to education about the risks on SNS, one should look beyond mere cognitive learning. Raising awareness about the risks on SNS is a first goal, but it would be most desirable to obtain a decrease of risky behavior as well. The transtheoretical model of behavior change (Prochaska, DiClemente & Norcross, 1992) states in this context that there are five stages in behavioral change. The first stage is the precontemplation stage, where individuals are unaware or underaware of the problem. A second stage is a contemplation stage, in which people recognize that a problem exists. The third stage is a preparation phase, in which action (stage four) is prepared. Finally, when the action is maintained, people arrive in the fifth and last stage. Considering this model, if we want to change the behavior of teenagers whose online behavior is unsafe, we first need to make sure that they are in a contemplation stage (i.e., that they recognize the problem). We might state that this ‘recognition’ contains a logic-based aspect (awareness of the problem) and an emotional-based aspect (care about the problem). Therefore, educational materials with regard to teenagers safety on SNS actually are aiming at raising awareness about risks on SNS, raising care about the risks on SNS and finally on making their behavior safer on SNS.

1.3. Purpose of the current study

As mentioned in section 1.2, the existing materials about online safety do not tackle all the categories of risks as described in section 1.1. Moreover, they do not focus on specific risks that are typical for the use of SNS. Therefore, new packages were developed covering all categories of risks and taking into account some instructional guidelines. The goal of these packages was not only that teenagers would be more aware of the risks, but also that they would care about them and that they would behave more carefully on SNS after following the course.

To verify whether these goals were obtained, a quasi-experimental study was set up in which these packages were implemented and evaluated in authentic classroom settings. In contrast to some previous intervention research where researchers were actively involved in the intervention (Del Rey & al., 2012), teachers were responsible for guiding the intervention to assure external validity. The following research question was put forth: does an intervention about content, contact or commercial risks have an impact on the awareness, attitudes and/or behavior of teenagers with regard to these risks?

2. Material and methods

2.1. The design of educational packages

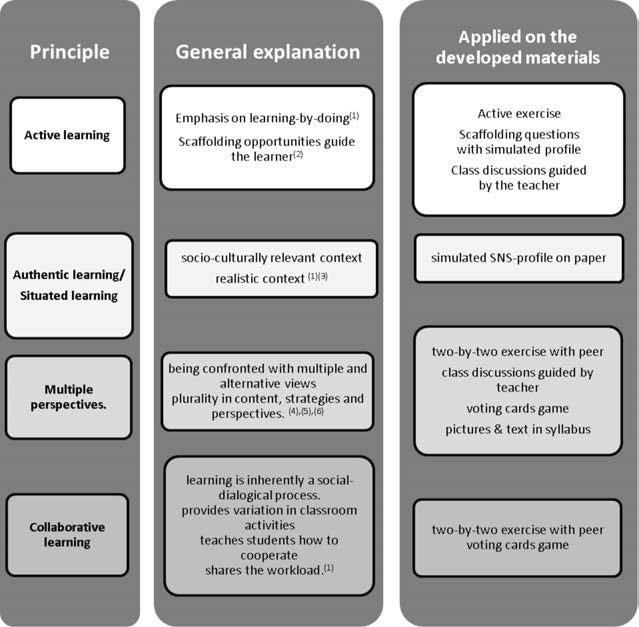

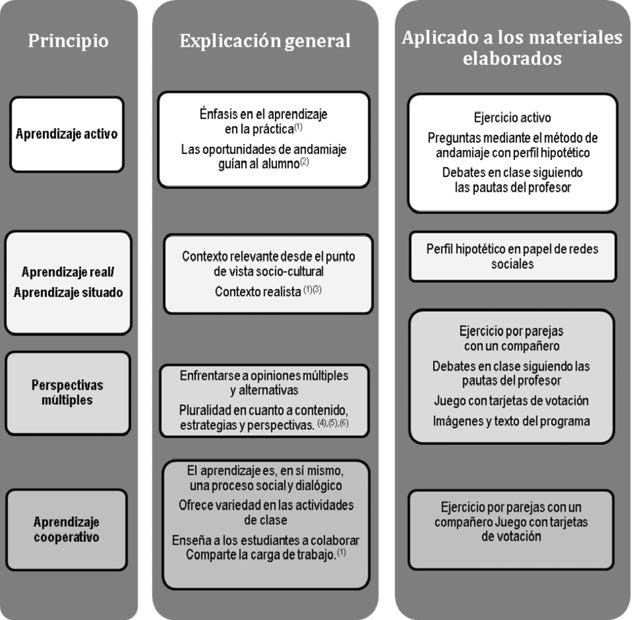

Three packages were developed: one about content risks, one about contact risks and one about commercial risks. The exercises in the courses are a selection of exercises used in existing materials (Insafe, 2014), narrowing the course to one hour to satisfy the need of teachers to limit the duration of the lessons and the work load (Vanderhoven & al., 2014). Some exercises were adjusted through small changes to assure complete coverage of the different risks and to satisfy some instructional guidelines drawn from constructivism, which is currently the leading theory in the field of learning sciences (Duffy & Cunningham, 1996). Figure 1 shows how these principles are integrated in the course.

Every package consisted of a syllabus for the pupils and a manual for the teacher. This manual contained background information and described in detail the learning goals and the steps of the course:

1) Introduction. The subject is introduced to the pupils by the teacher, using the summary of risks (De Moor & al., 2008).

2) Two-by-two exercise. Students receive a simulated ‘worst-case scenario’ SNS-profile on paper and have to fill in questions about the profile together with a peer. The questions were different for the three different packages, scaffolding the pupils towards the different existing risks on the profile. As an example, the course about contact risks contained a question «Do you see any signs of bullying, offensive comments or hurtful information? Where?». Different aspects of the profile could be mentioned as an answer to this question, such as the fact that the person joined a group «I hate my math-teacher and there is a status-update stating ‘Haha, Caroline made a fool out of herself today, again. She’s such a loser’».

3) Class discussion. Answers of the exercise are discussed, guided by the teacher.

4) Voting cards. Different statements with regard to the specific content of the course are given, such as «Companies cannot gather my personal information using my profile on a SNS» in the course about commercial risks. Students agree or disagree using green and red cards. Answers are discussed guided by the teacher.

5) Theory. Some real-life examples are discussed. All the necessary information is summarized.

2.2. A quasi-experimental evaluation study2.2.1. Design and Participants

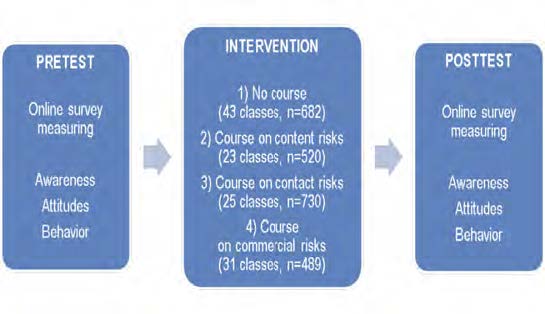

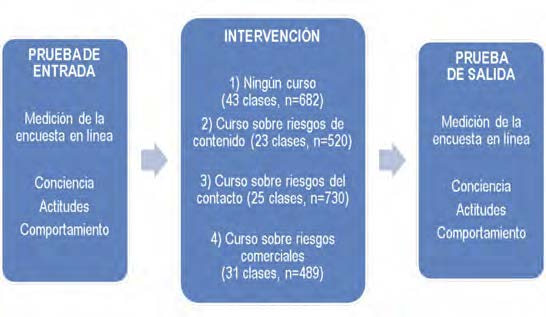

A pretest – posttest design was used, with one control condition and three experimental conditions, as depicted in figure 2. A total of 123 classes participated in the study, involving 2071 pupils between 11 and 19 years old (M=15.06, SD=1.87).

2.2.2. Procedure

To assure external validity, an authentic class situation with the regular teacher giving the lesson - using the detailed instructions in the manual for teachers and the syllabus for students- was necessary. Therefore, only after teachers agreed to cooperate in the research were students given the link to the online pretest. Approximately one week after they filled in the first survey, the course was given in the experimental conditions. Every class participated in one course about one subject. After they followed the course, pupils received the link to the posttest. Pupils in the control condition did not follow any course, but they received the link to the posttest at the same time as the pupils in the experimental conditions.

2.2.3. Measures

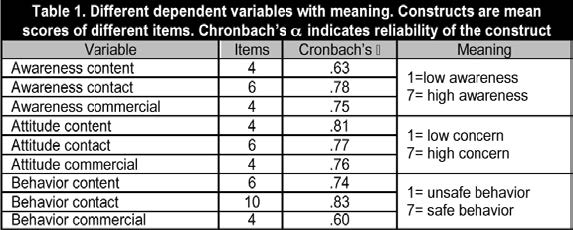

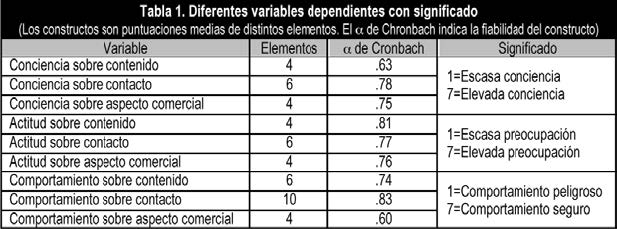

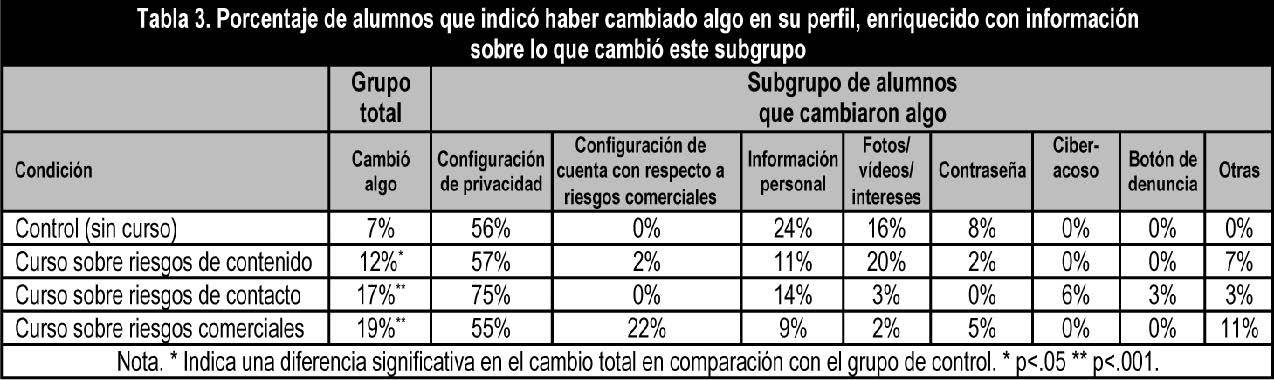

The pre- and posttest survey measured nine dependent variables: awareness, attitudes and behavior towards content, contact and commercial risks. These scales were conceptually based on the summary of risks as described by De Moor and colleagues (2008). If available, operationalizations of different risks were based on existing surveys (Hoy & Milne, 2010; Vanderhoven, Schellens & Valcke, 2013). In table 1 all variables are shown with their meaning and Cronbach’s alpha indicating the reliability of the scale. Additionally, a direct binary measure of behavioral change was conducted by the question «Did you change anything on your profile since the previous questionnaire?». If answered affirmatively, an open question about what they changed exactly gave us more qualitative insight into the type of behavioral change.

2.2.4. Analysis

Since our data has a hierarchical structure, Multilevel Modeling (MLM) with a two-level structure was used: pupils (level 1) are nested within classes (level 2). MLM also allows us to differentiate between the variance in posttest scores on classroom-level (caused by specific classroom characteristics, such as teaching style) and on individual level (independent of classroom differences). This is important given the implementation in authentic classroom settings, with the regular teacher giving the course.

Because a multiple testing correction was appropriate in this MLM (Bender & Lange, 2001) a Bonferroni-correction was applied to the significance level ?=0.05, resulting in a conservative significance of effects at the level ?=0.006.

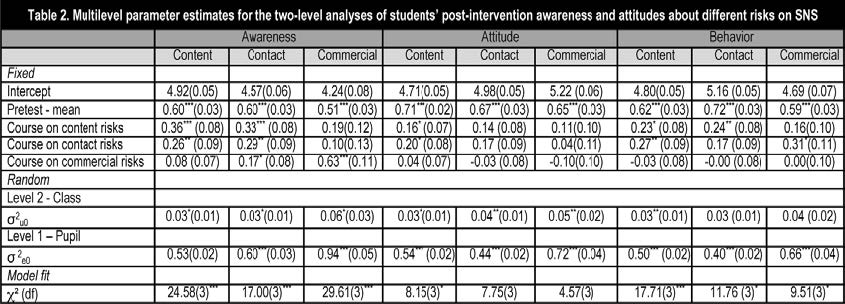

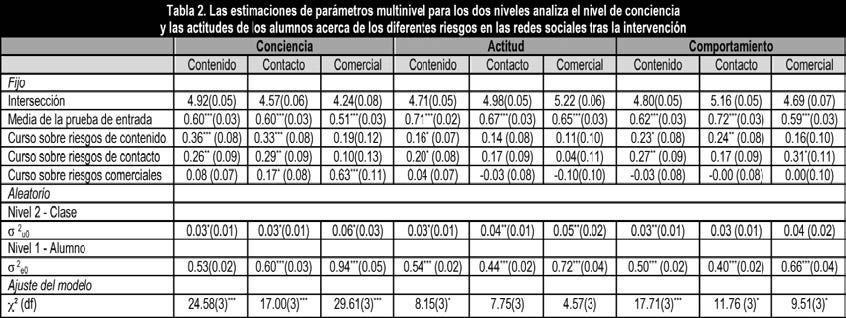

For every dependent variable, we tested a model with pretest scores as a covariate and the intervention as a predictor (with the control condition as a reference category). Therefore, estimates of the courses (as represented in table 2) give the difference in posttest-score on the dependent variable for pupils who followed this specific course compared to those who did not follow a course, when controlled for pretest scores. ?²-tests indicate whether the model is significantly better than a model without predictor.

3. Results

3.1. Awareness

A significant between-class variance could be observed for all three awareness variables on the posttest scores (?2u0, on average 13% of the total variance), indicating that the multilevel approach is needed.

Second, the results show that the intervention is a significant predictor of all three awareness-variables. Indeed, a positive impact of the given courses on awareness can be observed: a course on content risks or contact risks has positive effects on the awareness of both those risks and a course on commercial risks has a strong positive influence on the awareness of commercial risks. Moreover, no significant between-class variance is left, indicating that the initial between-class variance can be fully explained by the condition that classes were assigned to. This also implies that there are no important other predictors left of the posttest scores on class-level, such as teaching style, or differences in what has been said during class discussions.

The cross-effects between the course on content risks and the course on contact risks on the awareness about contact and content risks respectively, can be explained by the overlap in the courses and the risks. For example, cyberbullying and sexual solicitation can be seen as ‘shocking’, and therefore be categorized under contact as well as under content risks. However, commercial risks are totally different from the other two categories, and therefore knowledge about these risks can only be influenced by teaching about these risks in particular, as is reflected in our results.

3.2. Attitudes

Considering the measured attitudes, again a between-class variance was observed on the three different posttest scores (on average 16% of the total variance), indicating the need for a multilevel approach. Yet, there seems to be no impact of the courses on pupils’ attitudes whatsoever (non significant model tests). However, the mean scores over conditions, when controlling for pretest-scores, are moderate (ranging from 4.79 to 5.23 on a 7-point Likert scale). This indicates that teenagers do care about the risks at least to some extent, independently of the courses, so that a change in behavior might still be possible.

3.3. Behavior

Once again, significant between-class variance on all three behavioral variables (on average 12% of the total variance) shows that there were important differences between classes, and that a multi-level approach is required. With regard to pupils’ behavior, the course on contact risks has a positive impact on teenagers’ behavior concerning content risks and the course on content risks has a positive impact on teenagers’ behavior concerning contact risks. Although there is a lack of significant direct effects, it should be noted that the direct effect of the course on content risks on behavior with regard to content risks is marginally significant (p=.007). Furthermore, as stated in section 3.1, the overlap between the courses on content and contact risks can result in cross-content effects on the different risks.

There seems to be no impact of the courses on pupils’ behavior with regard to commercial risks. These results indicate that the given courses do not fully obtain the goal of changing behavior.

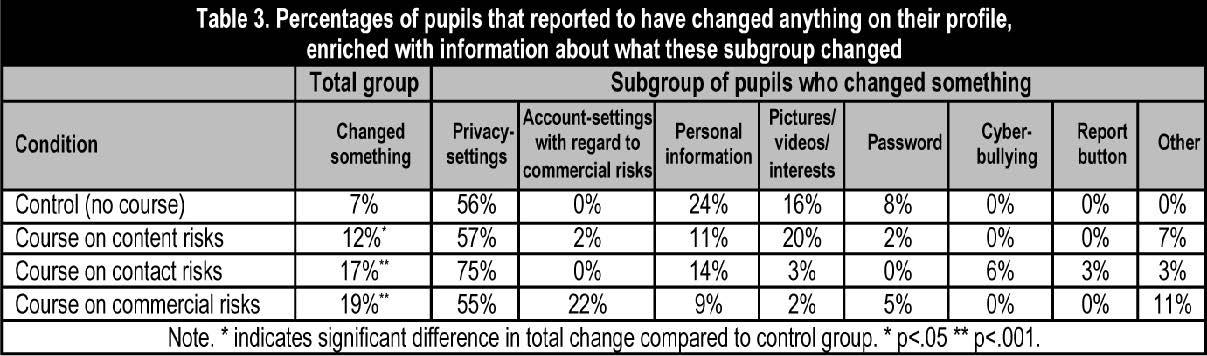

Still, if we analyze the answers to the question whether they changed anything on their profile (a more direct but also more specific measure of behavior), we do find some differences. In the control group, 7% of the pupils indicated having changed something on their profile, implying that even a survey encouraged some teenagers to check and change their profile. However, of those who followed a course, significantly more pupils changed something (16%, ?²=18.30, p<.001). Answers to the open question of what exactly they changed give us more insight in this information. The results of the content-analysis of these open questions can be found in table 3. As can be expected, when pupils had a course on content risks, they mainly change privacy-settings and the content of their profile (pictures, interests, personal information). When they followed a course on contact risks, they mostly change their privacy-settings and their personal information (including contact information). Participants of the course on commercial risks mostly changed their privacy-settings and their account-settings, protecting themselves against commercial risks. These results indicate that all courses – including the course on commercial risks- had an impact on the behavior of a significant amount of teenagers. Still, it should be noted that a lot of teenagers who did receive a course, reported that they did not change anything.

4. Discussion and conclusion

It was found that all three newly developed courses obtained their goal in raising awareness about the risks tackled in this course. However, no impact was found on attitudes towards the risks, and only a limited impact was found on teenagers’ behavior concerning these risks.

The lack of consistent impact on attitudes and behavior is an observation regularly found in general media education (Duran & al., 2008). In this particular case, there are several possible explanations. First of all, the given courses were short-term interventions, in the form of a one-hour class. The courses were organized this way to limit the workload of teachers, who reported not having a lot of time to spend on the topic (Vanderhoven & al., 2014). Although it was found that even short-term interventions can change online behavior with adolescents of 18 to 20 years old (Moreno & al., 2009), a more long term intervention might be needed to observe behavior changes with younger teenagers. Indeed, research in the field of prevention shows that campaigns need to be appropriately weighted to be effective (Nation & al., 2003). Therefore, additional lessons might be needed to observe a stronger change in behavior.

Second, it might be possible that attitudes and behavior need more time to change, independently of the duration of the course. In this case, it is not that raising awareness is not enough to change behavior, but that this process takes a longer time to be observed. The posttest was conducted approximately one week after the course. Maybe changes in attitudes and behavior could only be revealed later in time. Further research including retention tests should point this out.

Third, it is interesting to look at different theories about behavior, such as the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Following this theory, behavior is predicted by the attitudes towards this behavior, the social norm and perceived behavior control. One of the predictions of this theory is that the opinion of significant others has an important impact on one’s behavior. Because of peer pressure, important instructional strategies to increase knowledge such as collaborative learning might be counterproductive in changing behavior. The same reasoning might be applicable on the other instructional guidelines that were taken into account when developing the materials. These guidelines might only lead to better knowledge-construction, which is often the most important outcome of classroom teaching, and might not be adequate to change behavior. Despite the lack of impact on attitudes, and the limited impact on behavior, our findings show that education about the risks on SNS is not pointless. The materials developed can be used in practice to raise the awareness about the risks among teenagers in secondary schools. Considering the transtheoretical model of behavior change (Prochaska & al., 1992) described in section 1.2, this is a first step to behavioral change, by helping to get out of the precontemplation phase, into a contemplation phase, in which people recognize that a problem exists.

However, our findings also reveal the importance of evaluation, as it is found that there was no impact of our materials on attitudes and only a limited impact on behavior just yet. Outcome evaluation has been pointed out to be an important factor in effective prevention strategies (Nation & al., 2003), but is also lacking in most educational packages about online safety (Mishna & al., 2010; Vanderhoven & al., 2014). Therefore, it is not clear whether these packages have an impact, and if this impact extents to attitudes and behavior.

With regard to the risks on SNS, more research is needed to find the critical factors to change unsafe behavior and to develop materials that can obtain all the goals that were set out. Ideally, this research will follow a design-based approach, that is starting from the practical problems observed (e.g. unsafe behavior), and using iterative cycles of testing of solutions in practice (Phillips, McNaught & Kennedy, 2012). Through the refinement of problems, solutions and methods, design principles can be developed that can guarantee that on top of a knowledge gain, behavior will be safer as well.

Despite the invaluable contribution of this impact evaluation study, some limitations need to be taken into account. First of all, there was a lack of valid and reliable research instruments to measure media learning outcomes (Martens, 2010), and especially the outcome variables we were interested in. Therefore, a questionnaire was constructed based on the categories of risks described by De Moor & al. (2008) and the obtained goals of our developed materials (change in awareness, attitudes and behavior). Although reliability scales were satisfactory, it is difficult to ensure internal validity. Moreover, all questionnaires are susceptible to social desirability, especially in a pretest–posttest design (Phillips & Clancy, 1972). However, since we found differences in some variables but not in others, there is no reason to believe that social desirability had an important influence on the reliability of our responses. Still, more specific research about reliable and valid instruments in this field should be conducted.

Finally, this study only focused on an immediate, and thus short-term impact. This is in line with previous media literacy research, but it has important consequences for the interpretation of the results. Given the raising importance of sustainable learning, future research using a longitudinal approach might be interesting not only because, as stated above, it might reveal stronger effects on attitudes and behavior, but also to ensure that the impact on awareness is persistent over time.

As a conclusion we can state that the newly developed educational packages are effective in raising awareness about risks on SNS, but more research is needed to find out the critical factors to change attitudes and behavior. Since this is a desirable goal of teaching children how to act on SNS, our results are a clear indication of the importance of empirical research to evaluate educational materials.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T).

Almansa, A., Fonseca, O. & Castillo, A. (2013). Social Networks and Young People. Comparative Study of Facebook between Colombia and Spain. Comunicar, (40), 127-134. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-03-03).

Bender, R. & Lange, S. (2001). Adjusting for Multiple Testing - when and how? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(4), 343-349. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00314-0).

Cantor, J. & Wilson, B. J. (2003). Media and Violence: Intervention Strategies for Reducing Aggression. Media Psychology, 5(4), 363-403. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0504_03).

Cauffman, E. & Steinberg, L. (2000). (Im)maturity of Judgment in Adolescence: Why Adolescents May Be Less Culpable than Adults*. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 18(6), 741-760. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bsl.416).

Choo, K-K.R. (2009). Online Child Grooming: A Literature Review on the Misuse of Social Networking Sites for Grooming Children for Sexual Offences. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

Christofides, E., Muise, A. & Desmarais, S. (2012). Risky Disclosures on Facebook. The Effect of Having a Bad Experience on Online Behavior. Journal of Adolescent Research, 27 (6), 714-731. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0743558411432635).

De-Moor, S., Dock, M., Gallez, S., Lenaerts, S., Scholler, C. & Vleugels, C. (2008). Teens and ICT: Risks and Opportunities. Belgium: TIRO. (http://goo.gl/vvNl2z) (05-07-2013).

Debatin, B., Lovejoy, J.P., Horn, A.-K. & Hughes, B.N. (2009). Facebook and Online Privacy: Attitudes, Behaviors, and Unintended Consequences. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 15(1), 83-108. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01494.x).

Del-Rey, R., Casas, J.A. & Ortega, R. (2012). The ConRed Program, an Evidence-based Practice. Comunicar, (39), 129-137. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C39-2012-03-03).

Duffy, T. & Cunningham, D. (1996). Constructivism: Implications for the Design and Delivery of Instruction. In D. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 170-198). New York: Simon and Schuster.

Duran, R.L., Yousman, B., Walsh, K.M. & Longshore, M.A. (2008). Holistic Media Education: An Assessment of the Effectiveness of a College Course in Media Literacy. Communication Quarterly, 56(1), 49-68. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01463370701839198).

Gruber, J. (2001). Risky Behavior among Youths: An Economic Analysis. NBER. (http://goo.gl/hdvFA5) (05-07-2013).

Hoy, M.G. & Milne, G. (2010). Gender Differences in Privacy-related Measures for Young Adult Facebook users. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 10(2), 28-45. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2010.10722168)

Hum, N.J., Chamberlin, P.E., Hambright, B.L., Portwood, A.C., Schat, A. C. & Bevan, J.L. (2011). A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words: A Content Analysis of Facebook Profile Photographs. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(5), 1828-1833. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.04.003).

Insafe. (2014). Educational Resources for Teachers. (http://goo.gl/Q2BJyH).

Kafai, Y.B. & Resnick, M. (Eds.). (1996). Constructionism in Practice: Designing, Thinking, and Learning in A Digital World (1st ed.). Routledge.

Lange, P.G. (2007). Publicly Private and Privately Public: Social Networking on YouTube. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 361-380. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00400.x).

Lewis, C. C. (1981). How Adolescents Approach Decisions: Changes over Grades Seven to Twelve and Policy Implications. Child Development, 52(2), 538. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1129172).

Liu, H. (2007). Social Network Profiles as Taste Performances. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 252-275. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00395.x).

Livingstone, S. (2004a). Media Literacy and the Challenge of New Information and Communication Technologies. The Communication Review, 7(1), 3-14. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10714420490280152).

Livingstone, S. (2004b). What is Media Literacy? Intermedia, 32(3), 18-20.

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A. & Olafsson, K. (2011). Risks and Safety on the Internet: The Perspective of European Children. Full Findings. London: LSE: EU Kids Online.

Martens, H. (2010). Evaluating Media Literacy Education: Concepts, Theories and Future Directions. The Journal of Media Literacy Education, 2(1), 1-22.

Mayer, R. & Anderson, R. (1992). The Instructive Animation: Helping Students Build Connections Between Words and Pictures in Multimedia Learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(4), 444-452. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.84.4.444).

Mcgivern, P. & Noret, N. (2011). Online Social Networking and E-Safety: Analysis of Risk-taking Behaviours and Negative Online Experiences among Adolescents. British Conference of Undergraduate Research 2011 Special Issue. (http://goo.gl/oFLPA4) (05-07-2013).

Mishna, F., Cook, C., Saini, M., Wu, M.-J. & MacFadden, R. (2010). Interventions to Prevent and Reduce Cyber Abuse of Youth: A Systematic Review. Research on Social Work Practice, 21(1), 5-14. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1049731509351988).

Moreno, M.A., Vanderstoep, A., Parks, M.R., Zimmerman, F.J., Kurth, A. & Christakis, D.A. (2009). Reducing at-risk Adolescents’ Display of Risk Behavior on a Social Networking Web site: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Intervention Trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163(1), 35-41. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.502).

Nation, M., Crusto, C., Wandersman, A., Kumpfer, K.L., Seybolt, D., Morrissey-Kane, E. & Davino, K. (2003). What Works in Prevention. Principles of Effective Prevention Programs. The American Psychologist, 58(6-7), 449-456. (DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.449).

Patchin, J.W. & Hinduja, S. (2010). Changes in Adolescent Online Social Networking Behaviors from 2006 to 2009. Computer Human Behavior, 26(6), 1818-1821. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.009).

Phillips, D.L. & Clancy, K.J. (1972). Some Effects of «Social Desirability» in Survey Studies. American Journal of Sociology, 77(5), 921-940. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/225231).

Phillips, R., McNaught, C. & Kennedy, G. (2012). Evaluating e-Learning: Guiding Research and Practice. Connecting with e-Learning. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Prochaska, J.O., DiClemente, C.C. & Norcross, J.C. (1992). In Search of How People Change. Applications to Addictive Behaviors. The American Psychologist, 47(9), 1102-1114. (DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.47.9.1102).

Rittle-Johnson, B. & Koedinger, K.R. (2002). Comparing Instructional Strategies for Integrating Conceptual and Procedural Knowledge. Columbus: ERIC/CSMEE Publications.

Safer Internet Programme. (2009). Assessment Report on the Status of Online Safety Education in Schools across Europe. (http://goo.gl/kWdwZw) (05-07-2013).

Snowman, J., McCown, R. & Biehler, R. (2008). Psychology Applied to Teaching (12th ed.). Wadsworth Publishing.

Tejedor, S. & Pulido, C. (2012). Challenges and Risks of Internet Use by Children. How to Empower Minors? Comunicar, (39), 65-72. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C39-2012-02-06).

Vanderhoven, E., Schellens, T. & Valcke, M. (2013). Exploring the Usefulness of School Education About Risks on Social Network Sites: A Survey Study. The Journal of Media Literacy Education, 5(1), 285-294.

Vanderhoven, E., Schellens, T. & Valcke, M. (2014). Educational Packages about the Risks on Social Network Sites: State of the Art. Procedia. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 112, 603-612. (DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.1207).

Wood, D., Bruner, J.S. & Ross, G. (1976). The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89-100. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x).

Ybarra, M.L. & Mitchell, K.J. (2004). Youth Engaging in Online Harassment: Associations with Caregiver-Child Relationships, Internet Use, and Personal Characteristics. Journal of Adolescence, 27(3), 319-336. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.03.007).

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

La creciente popularidad de las redes sociales (RS) está causando preocupación por la privacidad y la seguridad de los usuarios, particularmente de los adolescentes que muestran diversas formas de conductas de riesgo en las redes sociales. En este contexto, la alfabetización mediática emerge como una prioridad e investigadores, profesores, padres y adolescentes enfatizan la responsabilidad de la escuela de enseñar a los adolescentes acerca de los riesgos en RS y cómo utilizarlas sin peligro. Sin embargo, los materiales educativos existentes no están teóricamente fundamentados, no abordan todos los riesgos específicos que los adolescentes pueden encontrar en las redes y carecen de evaluaciones de resultados. Además, estudios acerca de la educación mediática indican que, mientras los cambios a nivel de conocimientos suelen obtenerse fácilmente cambios en las actitudes y el comportamiento son mucho más difíciles de lograr. Por este motivo, nuevos paquetes educativos han sido desarrollados teniendo en cuenta directrices educativas. Posteriormente se llevó a cabo un estudio de intervención cuasi-experimental a fin de verificar si estos materiales son eficaces para cambiar el conocimiento, las actitudes y el comportamiento de los adolescentes en las redes sociales. El estudio constató que los cursos obtienen su objetivo en la sensibilización de los riesgos tratados. Sin embargo, no se observó ningún impacto en las actitudes hacia el riesgo, y el impacto en el comportamiento de los adolescentes en relación con estos riesgos fue limitado. Las implicaciones de este estudio son discutidas.

1. Introducción

Prácticamente en todo el mundo, los adolescentes constituyen uno de los principales grupos de usuarios de las redes sociales. Por ejemplo, en julio de 2012, aproximadamente un tercio de los usuarios de Facebook en Estados Unidos, Australia, Brasil y Bélgica eran menores de 24 años (checkfacebook.com). La nueva generación de tecnologías de redes de participación proporciona a los individuos una plataforma de sofisticada interacción en línea. La participación activa de audiencias mediáticas se convirtió en una característica fundamental del siglo XXI, y de ahí que el significado de alfabetización mediática haya evolucionado. Mientras que tradicionalmente hacía referencia a la capacidad de analizar y apreciar la literatura, se ha ampliado su ámbito, y ahora también incluye la exploración interactiva de Internet y el uso crítico de los medios y redes sociales. Livingstone (2004a), por lo tanto, describe la alfabetización mediática en términos de cuatro habilidades, como la capacidad de acceder, analizar, evaluar y crear mensajes en una variedad de contextos. Se ha constatado que, si bien a los niños les resulta fácil acceder y encontrar cosas en Internet, no tienen tanta habilidad para evitar algunos de los riesgos a los que se ven expuestos por la red (Livingstone, 2004b).

1.1. Riesgos en las redes sociales

Las categorías de riesgos a los que los adolescentes se enfrentan en las redes sociales son básicamente las mismas a las que hacen frente en general en Internet, resumidos por De Moor y colaboradores (2008). Hay tres categorías diferentes de riesgos. La primera describe los riesgos de contenido. Un ejemplo típico de contenido provocador que pueden encontrar los adolescentes en las redes sociales son los mensajes de odio. Estos mensajes pueden ser bastante directos, como actualizaciones de estado o publicaciones de carácter agresivo en el muro de alguien, pero también pueden ser indirectos, por ejemplo, uniéndose a grupos de odio. Los adolescentes necesitan igualmente desarrollar habilidades críticas para juzgar la fiabilidad de la información. La información errónea que podría aparecer en las redes puede ser intencionada, por ejemplo un cotilleo publicado por otros usuarios, o involuntaria. Esta última puede darse cuando alguien publica una broma que puede ser mal interpretada como información veraz. Entre los ejemplos típicos encontramos artículos de revistas satíricas publicadas en el muro de una red social.

La segunda categoría de riesgos incluye los riesgos de contacto, que son aquellos que tienen su origen en el hecho de que las redes sociales puedan utilizarse como herramienta para comunicarse y establecer contacto con otros (Lange, 2007). Junto a la mensajería instantánea, las redes son los medios más populares utilizados para el ciberacoso (Livingstone, Haddon, Görzig & Olafsson, 2011), ya sea a través de chat, mediante la publicación de mensajes ofensivos o creando páginas de grupos de odio. Además, también se pueden utilizar para solicitar servicios sexuales, como se observa en el proceso de captación de menores, donde un adulto con intenciones sexuales logra establecer una relación con un menor a través de Internet (Choo, 2009). Por otra parte, los usuarios se enfrentan a los riesgos de privacidad dada la gran cantidad de información personal que publican en línea (Almansa, Fonseca & Castillo, 2013; Livingstone & al., 2011). Asimismo, el 29% de los adolescentes mantiene un perfil público o ignora la configuración de su privacidad, y el 28% opta por una configuración parcialmente privada para que los amigos de sus amigos pueden ver su perfil (Livingstone & al., 2011).

La tercera categoría de riesgos contiene los riesgos comerciales. Estos incluyen el uso indebido de datos personales. La información se puede compartir con terceras empresas mediante aplicaciones, del mismo modo que se puede realizar un seguimiento al comportamiento del usuario para ofrecerle anuncios publicitarios y publicidad social orientados a su perfil (Debatin, Lovejoy, Horn & Hughes, 2009).

Todos estos riesgos constituyen una amenaza, ya que hay estudios que indican que la exposición a los riesgos en línea provoca daños y experiencias negativas en un número importante de casos (Livingstone & al., 2011; Mcgivern & Noret, 2011). El acoso en Internet es visto como un importante problema de salud pública, con los agresores haciendo frente a múltiples problemas, entre ellos una mediocre relación padres-hijo, consumo de drogas y delincuencia (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2004). Además, algunas teorías predicen que los adolescentes son menos propensos a reconocer los riesgos y las futuras consecuencias de sus decisiones (Lewis, 1981). Igualmente, se constató que tienen más dificultad para controlar sus impulsos y poseen niveles más altos de búsqueda de emociones y desinhibición que los adultos (Cauffman & Steinberg, 2000). Esto podría aumentar el riesgo que asumen los adolescentes (Gruber, 2001), sobre todo porque publicar fotos e intereses ayuda a crear y revelar la identidad del individuo (Hum & al., 2011; Lange, 2007; Liu, 2007).

1.2. El papel de la educación escolar

Muchos autores destacaron el papel de la educación escolar en el proceso de crear conciencia sobre estos riesgos on-line (Patchin & Hinduja, 2010; Tejedor & Pulido, 2012). Parece que las escuelas se encuentran en una posición ideal para promover la educación sobre la seguridad en línea, ya que llegan a casi todos los adolescentes al mismo tiempo (Safer Internet Programme, 2009), haciendo posible las influencias positivas entre compañeros (Christofides, Muise & Desmarais, 2012). Sin embargo, si bien el tema de seguridad on-line se ha incluido formalmente en los programas escolares, su aplicación es contradictoria (Safer Internet Programme, 2009) y, aunque se han desarrollado diferentes paquetes educativos sobre la seguridad de las redes (por ejemplo, Insafe, 2014), la mayoría de los paquetes se centran en la seguridad en Internet en general, y por consiguiente, carecen de algunos de los riesgos específicos que acompañan al empleo de las redes (por ejemplo, publicidad social, el impacto de los mensajes de odio y la venta de datos personales a terceras empresas). Los paquetes que se centran en los riesgos de las redes no abordan todas las categorías de riesgos mencionadas anteriormente, sino que con frecuencia se centran en los riesgos de privacidad, el ciberacoso o la «información errónea» (Del-Rey, Casas & Ortega, 2012; Vanderhoven, Schellens & Valcke, 2014). Además, a menudo no hay ninguna base teórica para los materiales, ni se produce una evaluación de los resultados (Mishna, Cook, Saini, Wu & MacFadden, 2010; Vanderhoven & al., 2014). De hecho, solo se han elaborado unos pocos estudios para evaluar el impacto de los programas de seguridad en línea, incluyendo un grupo de control y el uso de un enfoque de recopilación de datos cuantitativos (Del-Rey, Casas & Ortega, 2012).

Cabe señalar que los estudios cuantitativos de intervención en el campo de la alfabetización mediática general normalmente solo constatan que las intervenciones aumentan los conocimientos sobre el tema específico del curso (Martens, 2010; Mishna & al., 2010), mientras que los programas de alfabetización mediática a menudo pretenden cambiar las actitudes y al comportamiento. Sin embargo, las actitudes y los comportamientos no se miden frecuentemente, y si se hace, muchas veces no se hallan cambios (Cantor & Wilson, 2003; Duran & al., 2008; Mishna & al., 2010).

Aún así, cuando se trata de educación sobre los riesgos de las redes, uno debe mirar más allá del mero aprendizaje cognitivo. Crear conciencia en cuanto a los riesgos de las redes es un primer objetivo, pero sería más conveniente conseguir una reducción de los comportamientos de riesgo. El modelo transteorético del cambio de comportamiento (Prochaska, DiClemente & Norcross, 1992) establece en este contexto que existen cinco etapas en el cambio de conducta. La primera etapa es la etapa de precontemplación, donde las personas no son conscientes o ignoran el problema. Una segunda etapa corresponde a la contemplación, en la que reconocen que existe un problema. La tercera fase es una fase de preparación, en la que se organiza el plan de acción (cuarta etapa). Por último, cuando la acción se mantiene, las personas llegan a la quinta y última etapa. Teniendo en cuenta este modelo, si queremos cambiar el comportamiento de los adolescentes que actúan sin seguridad en línea, lo primero que hay que hacer es asegurarnos de que se encuentran en la etapa de contemplación (es decir, que reconocen el problema). Es evidente que este «reconocimiento» contiene un aspecto basado en la lógica (toma de conciencia del problema) y un aspecto de base emocional (preocupación por el problema). Por lo tanto, los materiales educativos relacionados con la seguridad de los adolescentes en las redes sociales en realidad están encaminados a crear conciencia acerca de los riesgos de las redes, a aumentar la atención sobre los riesgos de éstas y, finalmente, a conseguir que su comportamiento en las mismas sea más seguro.

1.3. Propósito del presente estudio

Tal como se menciona en la sección 1.2, los materiales existentes sobre seguridad en línea no abordan todas las categorías de riesgos, como se describe en la sección 1.1. Por otra parte, no se centran en los riesgos específicos que son típicos de la utilización de las redes sociales. Por estos motivos se elaboraron nuevos paquetes que incluyen todas las categorías de riesgos y tienen en cuenta algunas pautas educativas. El objetivo de estos paquetes no es solo que los adolescentes sean más conscientes de los riesgos, sino también que les den importancia y se comporten de una forma más segura en las redes después de realizar el curso.

Para comprobar si se lograron estos objetivos, se estableció un estudio cuasi-experimental en el que se utilizaron y evaluaron estos paquetes en un entorno escolar real. A diferencia de lo que ocurrió en algunas investigaciones de intervención previas donde los investigadores participaron activamente (Del-Rey & al., 2012), en este caso fueron los profesores los responsables de dirigir la intervención para asegurar su validez externa. Se planteó la siguiente pregunta clave en la investigación: ¿influiría una intervención sobre riesgos de contenido, contacto o comerciales en la conciencia, la actitud y/o el comportamiento de los adolescentes con respecto a estos riesgos?

2. Material y métodos

2.1. El diseño de paquetes educativos

Se elaboraron tres paquetes: uno sobre riesgos de contenido, otro sobre riesgos de contacto y un tercero sobre riesgos comerciales. El curso se compone de una serie de ejercicios ya utilizados en materiales existentes (Insafe, 2014), reduciéndolo a una hora para satisfacer la necesidad de los docentes de limitar la duración de las clases y la carga de trabajo (Vanderhoven & al., 2014). Algunos de estos ejercicios se ajustaron mediante pequeños cambios para asegurar la exhaustividad con respecto a los diferentes riesgos, y para satisfacer algunas pautas determinadas de constructivismo, que es actualmente la principal teoría en el campo de las ciencias del aprendizaje (Duffy & Cunningham, 1996). El gráfico 1 muestra cómo están integrados estos principios en el curso.

Cada paquete consta de un programa para los alumnos y un manual para el profesor. Este manual contiene información teórica y describe al detalle los objetivos de aprendizaje y las fases del curso:

1) Introducción. El profesor introduce el tema a los alumnos utilizando el resumen de riesgos (De Moor & al., 2008).

2) Ejercicio por parejas. Los estudiantes reciben un ejemplo de perfil de red social hipotética de alto riesgo sobre papel y tienen que contestar las preguntas sobre este perfil junto con un compañero. Las preguntas eran distintas para los tres diferentes paquetes, guiando a los alumnos (andamiaje) hacia los diferentes riesgos existentes en el perfil. Como ejemplo, el curso sobre riesgos de contacto contiene la pregunta: «¿Observas algún signo de acoso, ataques verbales o información hiriente?, ¿dónde?». Como respuesta a esta pregunta, se pudieron mencionar diferentes aspectos del perfil, como el hecho de que la persona se uniese al grupo «Odio a mi profesor de matemáticas», y se actualizase el estado con la frase: «jaja, Caroline hizo el ridículo hoy, una vez más. Es una perdedora».

3) Debate en clase. Se discute sobre las respuestas del ejercicio, siguiendo las pautas del profesor.

4) Tarjetas de votación. Se proporcionan diferentes frases con principios relacionados con el contenido específico del curso, tales como «Las empresas no pueden recopilar mi información personal a través de mi perfil en la red social» en el curso sobre riesgos comerciales. Los estudiantes muestran su acuerdo o desacuerdo con las tarjetas verdes y rojas. Se analizan las respuestas siguiendo las pautas del profesor.

5) Teoría. Se tratan algunos ejemplos de la vida real. Se resume toda la información necesaria.

2.2. Un estudio de evaluación cuasi-experimental2.2.1. Diseño y participantes

Se utilizó un diseño de prueba de entrada y de salida, con un grupo de control y tres grupos experimentales, como se muestra en el gráfico 2. En el estudio participaron un total de 123 clases, con 2.071 alumnos de entre 11 y 19 años (M=15,06; DT= 1,87).

2.2.2. Procedimiento

Para garantizar la validez externa, era necesario utilizar una situación de clase real con un profesor de verdad impartiendo la clase, siguiendo las instrucciones detalladas en el manual para profesores y el programa para alumnos. Por lo tanto, a los estudiantes solo se les proporcionó el enlace para acceder a la prueba de entrada en línea una vez que los profesores aceptaron cooperar en la investigación. Aproximadamente una semana después de rellenar la primera encuesta, se impartió el curso a los grupos experimentales. Cada clase participó en un curso sobre uno de los temas. Después de haber seguido el curso, los alumnos recibieron el enlace a la prueba de salida. Los alumnos del grupo de control no siguieron ningún curso, pero recibieron el enlace a la prueba salida al mismo tiempo que los alumnos de los grupos experimentales.

2.2.3. Medidas

La encuesta de las pruebas de entrada y de salida midió nueve variables dependientes: conciencia, actitudes hacia los riesgos de contenido, de contactos y comerciales. Estas escalas se basaron conceptualmente en el resumen de riesgos que describió De-Moor y colaboradores (2008). Si estaban disponibles, las aplicaciones de los diferentes riesgos se basaron en encuestas existentes (Hoy & Milne, 2010; Vanderhoven, Schellens & Valcke, 2013). En la tabla 1 se muestran las variables con su significado y el alfa de Cronbach indicando la fiabilidad de la escala. Además, se llevó a cabo una medición binaria directa de la modificación del comportamiento mediante la pregunta: «¿Cambiaste algo de tu perfil desde el cuestionario anterior?». Si la respuesta era afirmativa, una pregunta abierta sobre cuáles fueron exactamente esos cambios nos dio más datos cualitativos acerca del tipo de cambio en el comportamiento.

2.2.4. Análisis

Dado que nuestros datos tienen una estructura jerárquica, se utilizó un modelo multinivel, con una estructura de dos niveles: alumnos (nivel 1) anidados en clases (nivel 2). El MLM también nos permite diferenciar entre la varianza en las puntuaciones de la prueba de salida a nivel de las clases (causadas por las características específica del aula, como el estilo de enseñanza) y a nivel individual (independiente de las diferencias de las clases). Este punto es importante puesto que se aplicó en un entorno de clase real, con un profesor de verdad impartiendo el curso.

Dado que era apropiado realizar una corrección de pruebas múltiples en este MLM (Bender & Lange, 2001), se aplicó una corrección Bonferroni al nivel de significancia ?= 0,05, que resultó en una significancia de efectos conservadora al nivel de ?=0,006.

Para cada variable dependiente, probamos un modelo con puntuaciones de la prueba de entrada como covariable y la intervención como predictor (con el grupo de control como categoría de referencia). Por lo tanto, las estimaciones de los cursos (tabla 2) proporcionan la diferencia de puntuación de la prueba de salida en la variable dependiente de alumnos que siguieron este curso específico en comparación con aquellos que no siguieron ningún curso, cuando se controlan las puntuaciones de la prueba de entrada. Las pruebas ?² indican si el modelo es significativamente mejor que un modelo sin predictor.

3. Resultados

3.1. Toma de conciencia

Se puede observar una varianza significativa entre clases para las tres variables de la toma de conciencia en las puntuaciones de la prueba de salida (?2u0, una media del 13% de la varianza total), lo que indica que el enfoque multinivel es necesario.

En segundo lugar, los resultados muestran que la intervención es un predictor importante de las tres variables de conciencia. De hecho, se puede observar un impacto positivo sobre la toma de conciencia de los cursos impartidos: un curso sobre riesgos de contenido o riesgos de contacto tiene efectos positivos sobre la conciencia relativa a ambos riesgos y un curso sobre riesgos comerciales tiene una fuerte influencia positiva en la toma de conciencia de los riesgos comerciales. Por otra parte, no queda ninguna varianza significativa entre las clases, lo que indica que la varianza inicial entre clases puede explicarse totalmente por el grupo al que fueron asignadas dichas clases. Esto también implica que no quede ningún otro predictor importante de las puntuaciones de la prueba de salida en el nivel de las clases, como el estilo de enseñanza, o diferencias en lo que se ha dicho durante los debates en clase.

Los efectos cruzados entre el curso sobre riesgos de contenido y el curso sobre riesgos del contacto en cuanto a conciencia sobre los riesgos de contacto y de contenido, respectivamente, se pueden explicar por la superposición de los cursos y los riesgos. Por ejemplo, el ciberacoso y la solicitación de servicios sexuales pueden ser vistos como «escandalosos» y, por lo tanto, clasificarse dentro de los riesgos de contacto, así como de los riesgos de contenido. Sin embargo, los riesgos comerciales son totalmente diferentes de las otras dos categorías, y por lo tanto los conocimientos sobre estos riesgos solo pueden verse influenciados mediante la enseñanza acerca de estos riesgos en particular, como se refleja en los resultados.

3.2. Actitudes

Teniendo en cuenta las actitudes medidas, se observó una vez más una varianza entre clases en las tres diferentes puntuaciones de la prueba de salida (un promedio del 16% de la varianza total), lo que indica la necesidad de un enfoque multinivel. Sin embargo, parece ser que no hay repercusión alguna de los cursos en la actitud de los alumnos (pruebas de modelos no significativas). No obstante, las puntuaciones medias sobre las condiciones, cuando se controlan las puntuaciones de la prueba de salida, son moderadas (van desde 4,79 a 5,23 en una escala tipo Likert de 7 puntos). Esto indica que los adolescentes se preocupan por los riesgos por lo menos hasta cierto punto, al margen de los cursos, de manera que un cambio en el comportamiento podría ser posible.

3.3. Comportamiento

Una vez más, la varianza significativa entre clases en las tres variables de comportamiento (en promedio el 12% de la varianza total) muestra que existen diferencias importantes entre las clases, y que es necesario seguir un enfoque multinivel. Con respecto al comportamiento del alumno, el curso sobre riesgos de contacto tiene un impacto positivo en el comportamiento de los adolescentes en cuanto a riesgos de contenido, y el curso sobre riesgos de contenido tiene un impacto positivo en el comportamiento de los adolescentes en cuanto a riesgos de contacto. A pesar de la escasez de efectos directos significativos, cabe señalar que el curso de contenido de riesgo tiene un efecto marginalmente significativo (p=0,007) sobre el comportamiento de los adolescentes con respecto a los riesgos de contenido. Por otra parte, como ya se ha indicado en la sección 3.1, la superposición entre los cursos sobre riesgos de contenido y de contacto puede resultar en efectos de contenido cruzado sobre los diferentes riesgos.

Parece ser que los cursos no afectan al comportamiento del alumno con respecto a los riesgos comerciales. Estos resultados indican que los cursos impartidos no logran totalmente el objetivo de obtener un cambio en el comportamiento.

Sin embargo, si analizamos las respuestas a las preguntas sobre si han cambiado algo en su perfil (una forma de medir el comportamiento más directa, pero también más específica), encontramos algunas diferencias. En el grupo de control, el 7% de los alumnos indicaron que habían cambiado algo en su perfil, lo que implica que incluso una mera encuesta sirve para alentar a algunos adolescentes a comprobar y modificar su perfil. Sin embargo, de aquellos que siguieron un curso, hubo un número más significativo de alumnos que cambió algo (16%, ?²=18.30, p<.001). Las respuestas a la pregunta abierta sobre qué cambiaron exactamente nos proporciona más datos sobre esta información. Los resultados del análisis del contenido de estas preguntas abiertas se pueden encontrar en la tabla 3. Como era de esperar, cuando los alumnos asistieron al curso sobre riesgos de contenido, principalmente cambiaron la configuración de privacidad y el contenido de su perfil (fotos, intereses, información personal). Cuando siguieron el curso sobre riesgos de contacto, cambiaron en su mayoría su configuración de privacidad y su información personal (incluyendo la información de contacto). Cuando participaron en el curso sobre riesgos comerciales, cambiaron principalmente la configuración de privacidad y de la cuenta, protegiéndose de los riesgos comerciales. Estos resultados indican que todos los cursos –incluyendo el curso sobre riesgos comerciales– tuvieron un impacto en el comportamiento de un número importante de adolescentes. No obstante, hay que subrayar que una gran cantidad de los adolescentes que asistieron a algún curso no realizó ningún cambio.

4. Debate y conclusión

Se comprobó que los tres cursos elaborados recientemente lograron su objetivo en cuanto a ayudar a concienciar sobre los riesgos abordados en dichos cursos. Sin embargo, no se constató impacto alguno en las actitudes hacia los riesgos, y se confirmó tan solo un impacto limitado en el comportamiento de los adolescentes en lo que respecta a estos riesgos.

La carencia de un impacto coherente sobre las actitudes y el comportamiento es una observación que se encuentra normalmente en la educación mediática en general (Duran & al., 2008). En este caso en particular, hay varias explicaciones posibles. En primer lugar, los cursos fueron intervenciones a corto plazo, con una duración de tan solo una hora de clase. Se organizaron de esta manera para limitar la carga de trabajo de los profesores, que indicaron que no disponían de mucho tiempo para dedicar al tema (Vanderhoven & al., 2014). A pesar de que se constató que incluso las intervenciones a corto plazo pueden cambiar el comportamiento en línea de los adolescentes de 18 a 20 años (Moreno & al., 2009), es posible que haga falta una intervención a más largo plazo para observar cambios en el comportamiento de los más jóvenes. De hecho, la investigación en el campo de la prevención muestra que las campañas deben estar lo suficientemente dosificadas para ser eficaces (Nation & al., 2003). Por lo tanto, puede que se necesiten clases adicionales para observar un mayor cambio en el comportamiento.

En segundo lugar, es posible que se requiera más tiempo para modificar las actitudes y el comportamiento, independientemente de la duración del curso. En este caso, no es que no sea suficiente con crear conciencia para modificar el comportamiento, sino que es un proceso en el que los resultados tardan más tiempo en poder observarse. La prueba de salida se llevó a cabo aproximadamente una semana después del curso. Es posible que los cambios en las actitudes y el comportamiento únicamente puedan observarse más adelante en el tiempo. Esto debería puntualizarse con una investigación más a fondo que incluya pruebas de retención.

En tercer lugar, es interesante observar las diversas teorías sobre el comportamiento, como la teoría del comportamiento planificado (Ajzen, 1991). Siguiendo esta teoría, el comportamiento se predice por las actitudes hacia este comportamiento, la norma social y el control del comportamiento percibido. Una de las predicciones de esta teoría es que la opinión de personas allegadas tiene un impacto importante en el comportamiento. Debido a la presión de grupo, unas estrategias educativas importantes que aumenten el conocimiento, tales como el aprendizaje cooperativo, podrían ser contraproducentes para cambiar el comportamiento. El mismo razonamiento podría servir para las otras pautas educativas que se tuvieron en cuenta al elaborar los materiales. Estas pautas podrían únicamente dar lugar a una mejor construcción del conocimiento, que a menudo es el resultado más importante de la enseñanza en el aula, y posiblemente no sean adecuadas para cambiar el comportamiento. A pesar del escaso efecto sobre las actitudes, y el limitado impacto sobre el comportamiento, los resultados indican que la educación acerca de los riesgos de la redes no es del todo ineficaz. Los materiales elaborados se pueden utilizar en la práctica para aumentar la conciencia sobre los riesgos a los que están expuestos los adolescentes de las escuelas secundarias. Teniendo en cuenta el modelo transteorético de cambio en el comportamiento (Prochaska & al., 1992) descrito en la sección 1.2, este es un primer paso hacia el cambio de comportamiento, ayudando a salir de la fase de contemplación, en la que la gente reconoce que existe un problema.

Sin embargo, nuestros hallazgos también revelan la importancia de la evaluación, ya que se sabe que nuestros materiales no lograron aún ningún efecto sobre las actitudes y tan solo un impacto limitado en el comportamiento. Los resultados de la evaluación han señalado que se trata de un factor importante en las estrategias efectivas de prevención (Nation & al., 2003), pero que también la mayoría de paquetes educativos sobre seguridad en línea carecen de ella (Mishna & al., 2010; Vanderhoven & al., 2014). Por lo tanto, no está claro si estos paquetes influyen, y si esta influencia se extiende a las actitudes y al comportamiento.

Con respecto a los riesgos de las redes sociales, son necesarias más investigaciones para determinar los factores críticos que cambian las conductas de riesgo así como desarrollar materiales que puedan lograr todos los objetivos que se propusieron. Idealmente, esta investigación seguirá un enfoque basado en el diseño, que comienza a partir de los problemas prácticos observados (por ejemplo, conductas de riesgo), y utiliza ciclos iterativos de pruebas de soluciones en la práctica (Phillips, McNaught & Kennedy, 2012). Mediante el perfeccionamiento de los problemas, las soluciones y los métodos, se pueden desarrollar principios de diseño que puedan garantizar que junto a la adquisición de conocimientos, el comportamiento también será más seguro.

A pesar de la valiosa contribución de este estudio de evaluación de impacto, deben tenerse en cuenta algunas limitaciones. En primer lugar, existe una carencia de instrumentos de investigación válidos y fiables para medir los resultados del aprendizaje mediático (Martens, 2010), y sobre todo las variables de resultado en las que estábamos interesados. Por lo tanto, se creó un cuestionario basado en las categorías de riesgos descritas por De-Moor y colaboradores (2008) y los objetivos logrados de nuestros materiales desarrollados (cambio en la conciencia, las actitudes y el comportamiento). Aunque las escalas de fiabilidad fueron satisfactorias, es difícil asegurar la validez interna. Además, todos los cuestionarios - especialmente en un diseño de pruebas de entrada y salida- son susceptibles a la aceptación social (Phillips & Clancy, 1972). Sin embargo, dado que hallamos diferencias en algunas variables, pero no en otras, no hay ninguna razón para creer que la aceptación social tuviese una influencia importante en la fiabilidad de nuestras respuestas. Sin embargo, dentro de este campo deben llevarse a cabo estudios más específicos sobre instrumentos fiables y válidos.

Por último, este estudio se centró exclusivamente en un impacto inmediato, y, por tanto, a corto plazo. Esto está en consonancia con investigaciones previas sobre alfabetización mediática, pero tiene consecuencias importantes para la interpretación de los resultados. Habida cuenta de la importancia de un aprendizaje sostenible, puede resultar interesante realizar una investigación futura a través de un enfoque longitudinal, no solo porque, como se ha dicho anteriormente, podría revelar unos efectos más sólidos en las actitudes y el comportamiento, sino también para asegurar que el impacto en la conciencia es constante en el transcurso del tiempo.

Como conclusión podemos afirmar que los recientemente elaborados paquetes educativos son eficaces en cuanto al aumento de la conciencia sobre los riesgos de las redes sociales, pero es necesario investigar más para determinar los factores críticos que influyen en el cambio de actitudes y de comportamiento. Dado que se trata de un objetivo deseable para enseñar a los niños cómo actuar en las redes, nuestros resultados son una clara indicación de la importancia de los estudios empíricos para evaluar materiales educativos.

Referencias

Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T).

Almansa, A., Fonseca, O. & Castillo, A. (2013). Social Networks and Young People. Comparative Study of Facebook between Colombia and Spain. Comunicar, (40), 127-134. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-03-03).

Bender, R. & Lange, S. (2001). Adjusting for Multiple Testing - when and how? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(4), 343-349. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00314-0).

Cantor, J. & Wilson, B. J. (2003). Media and Violence: Intervention Strategies for Reducing Aggression. Media Psychology, 5(4), 363-403. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0504_03).

Cauffman, E. & Steinberg, L. (2000). (Im)maturity of Judgment in Adolescence: Why Adolescents May Be Less Culpable than Adults*. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 18(6), 741-760. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bsl.416).

Choo, K-K.R. (2009). Online Child Grooming: A Literature Review on the Misuse of Social Networking Sites for Grooming Children for Sexual Offences. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

Christofides, E., Muise, A. & Desmarais, S. (2012). Risky Disclosures on Facebook. The Effect of Having a Bad Experience on Online Behavior. Journal of Adolescent Research, 27 (6), 714-731. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0743558411432635).

De-Moor, S., Dock, M., Gallez, S., Lenaerts, S., Scholler, C. & Vleugels, C. (2008). Teens and ICT: Risks and Opportunities. Belgium: TIRO. (http://goo.gl/vvNl2z) (05-07-2013).

Debatin, B., Lovejoy, J.P., Horn, A.-K. & Hughes, B.N. (2009). Facebook and Online Privacy: Attitudes, Behaviors, and Unintended Consequences. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 15(1), 83-108. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01494.x).

Del-Rey, R., Casas, J.A. & Ortega, R. (2012). The ConRed Program, an Evidence-based Practice. Comunicar, (39), 129-137. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C39-2012-03-03).

Duffy, T. & Cunningham, D. (1996). Constructivism: Implications for the Design and Delivery of Instruction. In D. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 170-198). New York: Simon and Schuster.

Duran, R.L., Yousman, B., Walsh, K.M. & Longshore, M.A. (2008). Holistic Media Education: An Assessment of the Effectiveness of a College Course in Media Literacy. Communication Quarterly, 56(1), 49-68. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01463370701839198).

Gruber, J. (2001). Risky Behavior among Youths: An Economic Analysis. NBER. (http://goo.gl/hdvFA5) (05-07-2013).

Hoy, M.G. & Milne, G. (2010). Gender Differences in Privacy-related Measures for Young Adult Facebook users. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 10(2), 28-45. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2010.10722168)

Hum, N.J., Chamberlin, P.E., Hambright, B.L., Portwood, A.C., Schat, A. C. & Bevan, J.L. (2011). A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words: A Content Analysis of Facebook Profile Photographs. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(5), 1828-1833. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.04.003).

Insafe. (2014). Educational Resources for Teachers. (http://goo.gl/Q2BJyH).

Kafai, Y.B. & Resnick, M. (Eds.). (1996). Constructionism in Practice: Designing, Thinking, and Learning in A Digital World (1st ed.). Routledge.

Lange, P.G. (2007). Publicly Private and Privately Public: Social Networking on YouTube. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 361-380. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00400.x).

Lewis, C. C. (1981). How Adolescents Approach Decisions: Changes over Grades Seven to Twelve and Policy Implications. Child Development, 52(2), 538. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1129172).

Liu, H. (2007). Social Network Profiles as Taste Performances. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 252-275. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00395.x).

Livingstone, S. (2004a). Media Literacy and the Challenge of New Information and Communication Technologies. The Communication Review, 7(1), 3-14. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10714420490280152).

Livingstone, S. (2004b). What is Media Literacy? Intermedia, 32(3), 18-20.

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A. & Olafsson, K. (2011). Risks and Safety on the Internet: The Perspective of European Children. Full Findings. London: LSE: EU Kids Online.

Martens, H. (2010). Evaluating Media Literacy Education: Concepts, Theories and Future Directions. The Journal of Media Literacy Education, 2(1), 1-22.

Mayer, R. & Anderson, R. (1992). The Instructive Animation: Helping Students Build Connections Between Words and Pictures in Multimedia Learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(4), 444-452. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.84.4.444).

Mcgivern, P. & Noret, N. (2011). Online Social Networking and E-Safety: Analysis of Risk-taking Behaviours and Negative Online Experiences among Adolescents. British Conference of Undergraduate Research 2011 Special Issue. (http://goo.gl/oFLPA4) (05-07-2013).

Mishna, F., Cook, C., Saini, M., Wu, M.-J. & MacFadden, R. (2010). Interventions to Prevent and Reduce Cyber Abuse of Youth: A Systematic Review. Research on Social Work Practice, 21(1), 5-14. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1049731509351988).

Moreno, M.A., Vanderstoep, A., Parks, M.R., Zimmerman, F.J., Kurth, A. & Christakis, D.A. (2009). Reducing at-risk Adolescents’ Display of Risk Behavior on a Social Networking Web site: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Intervention Trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163(1), 35-41. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.502).

Nation, M., Crusto, C., Wandersman, A., Kumpfer, K.L., Seybolt, D., Morrissey-Kane, E. & Davino, K. (2003). What Works in Prevention. Principles of Effective Prevention Programs. The American Psychologist, 58(6-7), 449-456. (DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.449).

Patchin, J.W. & Hinduja, S. (2010). Changes in Adolescent Online Social Networking Behaviors from 2006 to 2009. Computer Human Behavior, 26(6), 1818-1821. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.009).

Phillips, D.L. & Clancy, K.J. (1972). Some Effects of «Social Desirability» in Survey Studies. American Journal of Sociology, 77(5), 921-940. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/225231).

Phillips, R., McNaught, C. & Kennedy, G. (2012). Evaluating e-Learning: Guiding Research and Practice. Connecting with e-Learning. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Prochaska, J.O., DiClemente, C.C. & Norcross, J.C. (1992). In Search of How People Change. Applications to Addictive Behaviors. The American Psychologist, 47(9), 1102-1114. (DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.47.9.1102).

Rittle-Johnson, B. & Koedinger, K.R. (2002). Comparing Instructional Strategies for Integrating Conceptual and Procedural Knowledge. Columbus: ERIC/CSMEE Publications.

Safer Internet Programme. (2009). Assessment Report on the Status of Online Safety Education in Schools across Europe. (http://goo.gl/kWdwZw) (05-07-2013).

Snowman, J., McCown, R. & Biehler, R. (2008). Psychology Applied to Teaching (12th ed.). Wadsworth Publishing.

Tejedor, S. & Pulido, C. (2012). Challenges and Risks of Internet Use by Children. How to Empower Minors? Comunicar, (39), 65-72. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C39-2012-02-06).

Vanderhoven, E., Schellens, T. & Valcke, M. (2013). Exploring the Usefulness of School Education About Risks on Social Network Sites: A Survey Study. The Journal of Media Literacy Education, 5(1), 285-294.

Vanderhoven, E., Schellens, T. & Valcke, M. (2014). Educational Packages about the Risks on Social Network Sites: State of the Art. Procedia. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 112, 603-612. (DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.1207).

Wood, D., Bruner, J.S. & Ross, G. (1976). The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89-100. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x).

Ybarra, M.L. & Mitchell, K.J. (2004). Youth Engaging in Online Harassment: Associations with Caregiver-Child Relationships, Internet Use, and Personal Characteristics. Journal of Adolescence, 27(3), 319-336. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.03.007).

Document information

Published on 30/06/14

Accepted on 30/06/14

Submitted on 30/06/14

Volume 22, Issue 2, 2014

DOI: 10.3916/C43-2014-12

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?