Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

New technologies have transformed higher education whose application has implied changes at all levels. These changes have been assimilated by the university community in various ways. Subtle differences among university students have emerged; these differences determine that the resources the network offers have been used in different ways, thus creating gaps in the university population. This study seeks to determine the level of incidence of the variable of university students’ incomes on the uses and intensity of use of the Internet tools and resources. Students were classified using factor analysis complemented through cluster analysis in order to obtain user profiles; these profiles were verified by means of discriminant analysis. Finally, chi-square was applied to determine the relationship between income level and user profiles. As a result, three profiles were identified with different levels of use and intensity of use of the Internet tools and resources, and statistically the incidence of income in the creation of those profiles was proved. To conclude, we can say that the income level falls mainly on the variables that define the access possibilities; gender has a special behavior; however, since the profile of the highest level has a double proportion for men, though women have better performance in general terms.

1. Introduction

In spite of the widespread use of Internet, there are groups that are unable to take full advantage of the benefits that the Web provides. There are many reasons why the social and economic structure provides unequal access to knowledge and information. This assertion falls within the theory of knowledge gaps (Tichenor, Donohue & Olien, 1970) which states that the highest social-economic strata tend to have more rapid access to media-generated information than the lower strata. This theory was formulated with television and newspaper media in mind; however, traditional media are being absorbed by cybermedia and the Internet in general (Cebrián-Herreros, 2009) which leads to differences in how information is used, the tools deployed, and intensity of use, among other factors that constitute this so-called digital inequality.

DiMaggio, Hargittai, Rusell & Robinson (2001) point to differences in the NTIA1 reports of 1995-2000 which indicate that the highest social-economic strata had greater access to Internet; studies on the digital divide find different variables that are determinants of the usage of Internet tools, which support the knowledge gap theory and the implications for the digital divide.

DiMaggio, Hargittai, Celeste & Shafer (2004) suggest that those who have Internet access use the Web in different ways; these researchers go beyond the focus on the possibilities of Internet connection to offer an analysis from a broader, more theoretical context that searches out differences in the effects of Internet use on people and society. The digital divide is not only about conditions of access to technology and connection; certain other aspects also come into play in determining good use of that technology and its resources. This new approach to what is known as the «digital divide» is also called «digital inequality» by some authors.

A review of the current literature on the subject shows that in general terms there are two approaches to digital inequality. In the first, the authors’ analysis covers dimensions such as access, user competence, main uses and intensity of use (Castaño, 2010; Van Dijk, 2005; Warschauer, 2003). The second approach centres more on demographic variables that include income, education, race, gender, job, age and family structure among others (Castells, 2001; DiMaggio & al., 2004; Wilson, 2006). Beyond the segmentation of these dimensions of analysis, we find that the first approaches adapt to a relationship that depends on the second2; that is, access, user competence, main uses and intensity of use are variables that depend on income, education, age, gender, among other demographic variables. Of these variables, income and education are the uppermost when determining the extent of digital inequality (Van Dijk, 2005) and of user behaviour with technologies once access limitations are controlled (Keil, 2008)3.

There is a direct relation between family income and levels of Internet use (Taylor, Zhu, Dekkers & Marshall, 2003), proving that digital inequality is an extension of social inequality and that its effects go beyond the dichotomy of being connected or not. The differences can affect digital natives. Livingstone & Helsper (2007) found differences in the take-up levels of the opportunities and resources available on-line in middle-class and working-class children, meaning that the incidence of factors such as the availability of an Internet connection at home and the time spent on-line, among others, can affect the level of Internet usage; in the case of university students, the socio-economic level affects Internet use which in turn influences student academic performance (Castaño, 2010). At the macro-economic level, there is also a direct relation between gross domestic product (GDP) and a country’s digitalization rate (Iske, Klein & Kutscher, 2005), and although this is not the only reason, it is the most important in terms of analysing the dynamic of the digital divide (Keil, 2008).

There are significant differences that are determined by level of education. Users with a higher level of education make better use of their time on-line and Internet tools and resources (Graham, 2010; Van Dijk, 2006). The level of education is the variable that most affects Internet use for searching for information and communication (Iske & al., 2005; Graham, 2010), and differentiates the uses made of information, possibilities and resources by each user.

The digital divide depends on social and economic factors that reveal differences among internauts. These differences form a heterogeneous set with regard to their composition and the use they make of the Net. This paper analyses the differences in Internet use among university students in Ecuador; the relation between the income of the student’s family and Internet use. We aim to verify if there is a difference between students from low- and high-income families when utilizing Web resources, as well as their habits and levels of intensity of Internet use.

2. Method

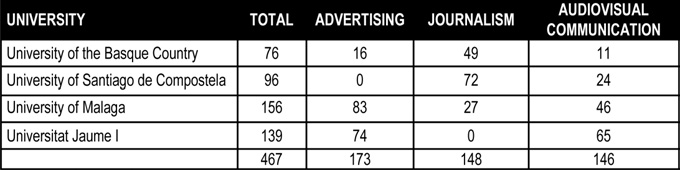

Forty universities in Ecuador were surveyed for information on technological infrastructure, institutional policy and the level of use of on-line tools in student education. The five universities with the highest values were selected and a significant sample was taken of each; a total of 4,897 students answered the questionnaire. The survey managed to maintain a gender balance in accordance with the total number of students enrolled in each institution and specialism in order to obtain a broader sample representation as possible, the final spread being 50.5% men and 49.5% women.

The variables and instruments for data gathering were based on those used in the Proyecto Internet Cataluña4, and adapted to Latin American needs. This investigation worked with 31 variables divided into the following groups: student family income, knowledge of and access to Internet, academic and social use of Internet, and student perceptions of the usefulness of the Internet. The variables are documented in Table 2. Income level was calculated using a scale that included the country’s quintile income values, as developed by the National Census and Statistics Institute (INEC5); the other variables were classified on a scale of 1 to 5.

The information was collected and the students classified according to their uses of and intensity of use of the Internet. Factor analysis was used to reduce the number of variables to 8 factors covering the 62% variance. These were then used as initial data for the cluster analysis that produced classifications for three, four and five groups. Finally, the composition of the clusters was contrasted by a discriminant analysis of each classification. The aim of this analysis was to make the classification more accurate; the dependent variable was the cluster number to which the student belonged, and the independent variables were the remainder that was used in the factor analysis.

The relation between income and the use of Internet profile (cluster) was verified by the chi-square test that enables two quantitative variables to be related via a null hypothesis in which there is no relation between variables.

3. Results

3.1. Level of student family income

The student distribution according to level of income is shown in the following table. The levels correspond to each quintile of the student’s family income.

3.2. Profile of Internet use

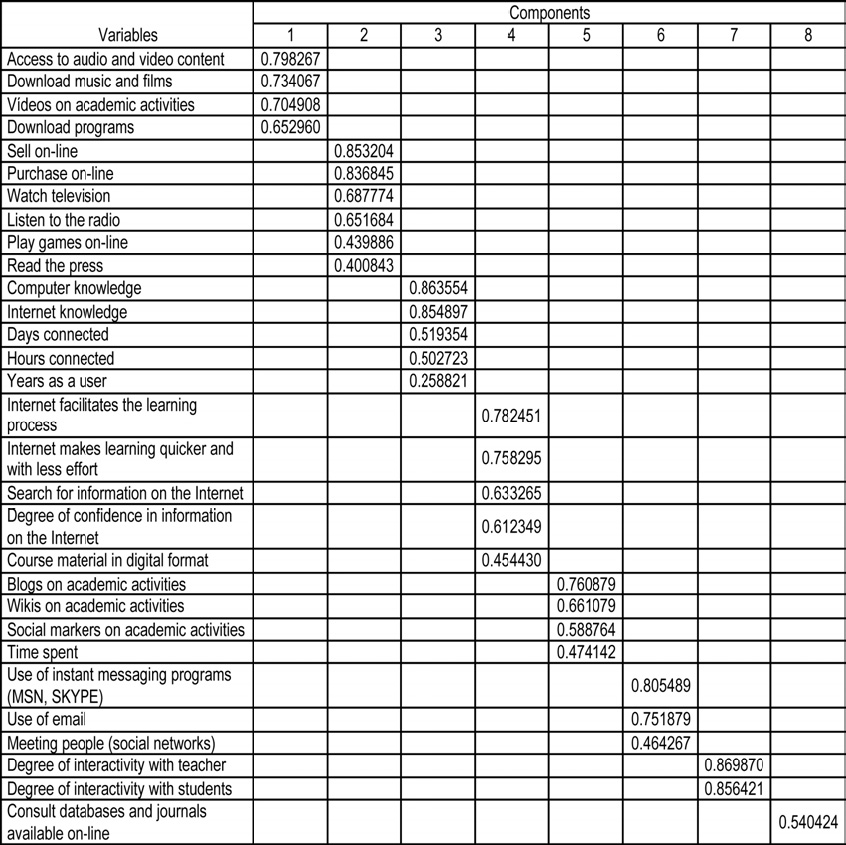

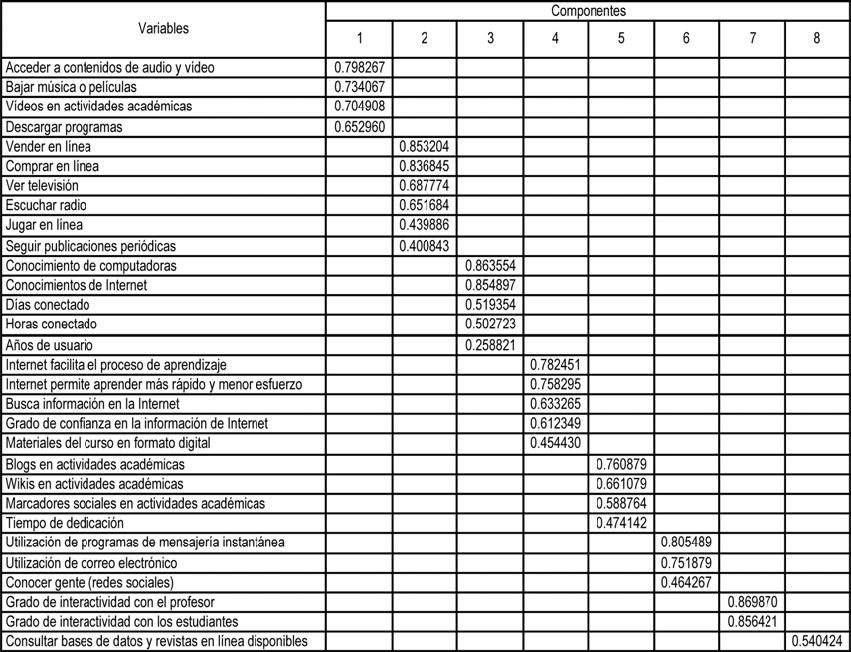

The factor analysis produced 8 factors (components) that justify the 62% variance, details of which appear in the table below.

The resulting components are described by the student characteristics, and are clearly differentiated:

- Component 1: Downloads. This component describes those students who download videos, programs and general software from the Web.

- Component 2: Transactions-leisure. This groups features buying and selling on the Internet, watching television, listening to the radio, playing on-line games and reading the press.

- Component 3: Knowledge. This covers characteristics that describe the user’s level of knowledge and experience.

- Component 4: Usefulness. Referring to student perceptions on the usefulness of the Internet in academic activities.

- Component 5: Social tools. This groups those characteristics of the use of tools and social resources in academic activities.

- Component 6: Social networks. These variables refer to the use of live chat, email and social networks.

- Component 7: Interactivity. Describes the degree of student interactivity with the teacher and other students.

- Component 8: Databases. This refers to a single variable that describes the intensity of use of scientific databases and / or on-line journals.

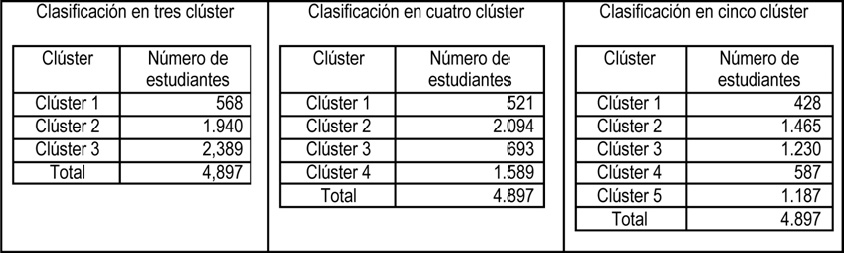

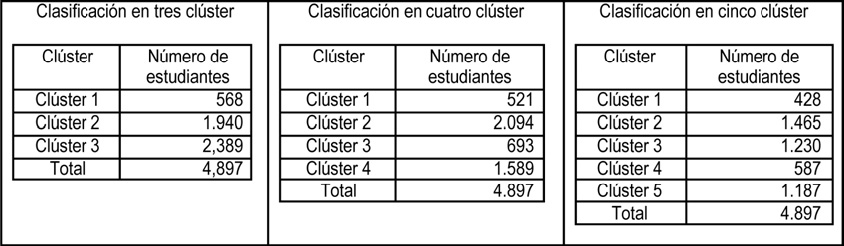

A cluster analysis was applied to all these components, and classifications were obtained for three, four and five groups. The classifications are:

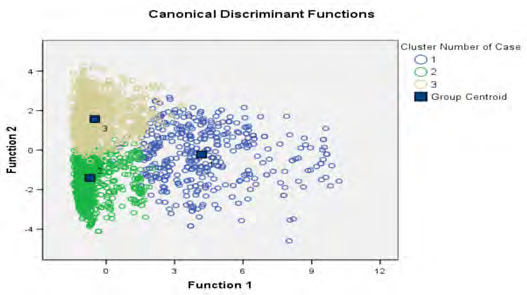

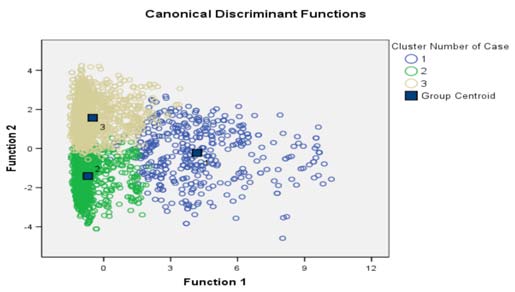

A discriminant analysis was applied to each classification to verify the validity of the clusters. The result of each case indicates that the element percentage is classified correctly; so, in the three-group classification 96.5% of the sample elements are correctly classified; 92.4% of the sample elements are correctly classified in the four-group classification, and 90.3% of the sample elements are correctly classified in the five-group classification. The results show that the classification with the lowest number of groups is the most accurate.

The decision to work with three groups was based on this analysis.

The names assigned to the profiles forms part of a context in which the research is carried out, such that their names cannot be compared to other realities.

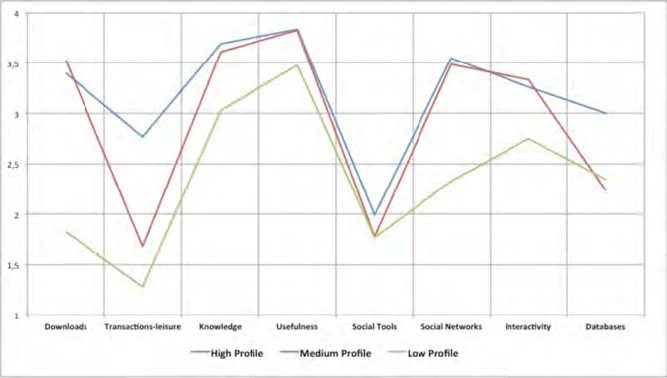

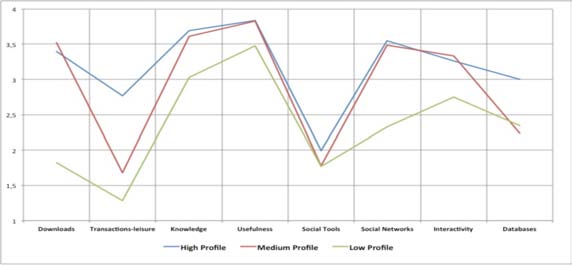

- High profile: Cluster 1 represents 11.6% of the students, with an average level of downloading of videos, programs and general software: they have the most experience and the broadest knowledge in terms of computer and Internet use; they see Web tools as useful for learning; they are the ones who most use social networks and interaction tools; and they use library databases with greater intensity than the other groups.

- Medium profile: Cluster 2 accounts for 48.8% of students; the members of this group have similar characteristics to those in Cluster 1. All Cluster 2 components present inferior values except for downloads; the perception of usefulness and level of interactivity are practically the same. The biggest differences between the two are found in the components that cover transactions, use of social tools in academic activities and use of databases. Here the values presented by the first group are palpably superior.

- Low profile: This group’s values are less intense for the use of the various Internet instruments and it accounts for 39.6% of the students. The main characteristics of this group are that they have an average level of knowledge and experience in Internet use; perception that the use of Internet tools could be useful for their education is low, and they interact infrequently with their teachers and fellow students. This group downloads very little and hardly ever uses the Internet for transactions or gaming, and their use of social tools, social networks and interactivity is minimal.

3.3. Verification of relations between variables

The chi-square test was used to verify the null hypothesis, the critical value for the given parameters being 20.09. The chi-square value was calculated at 418.63, significantly higher than the critical value and which enables us to reject the null hypothesis.

To complete the analysis, we calculated the correlation indices between the level of income and the proportion of students on each level of the scale used to extract the information. The variables considered were: level of Internet knowledge, number of hours and days per week spent on the Internet and the number of years as an Internet user. There was a significant correlation between all the variables. The exceptions were the level of computer and Internet knowledge variables where there were two levels on the scale with no significant correlation, and the number of days connected to the Internet variable which showed no significant correlation. The same occurred in live chat, video and program downloads and the use of social networks.

4. Discussion of the results

The chi-square test result rejected the null hypothesis, demonstrating that level of income influenced the students’ Internet use profiles; and there is further evidence to support this finding. The analysis of income distribution levels in each profile revealed that students with better economic prospects gathered mainly in the high profile while those with lower income congregated around the low profile. This fits in with the differences found by DiMaggio & al. (2004) for Internet use and low income levels.

The coefficient correlation between income levels and the variables of the knowledge components6 are significant. However, it can be deduced that the higher the student’s family income level, the greater the possibility of computer use and Internet connection; and the greater the number of years’ experience as an Internet user, the broader the knowledge and the longer the number of days and hours spent connected to the Internet. Yet when the correlation is ordered for income level, we find that income level has greatest influence on the user’s years of experience followed by the number of hours connected per session, the days per week spent on the Internet and level of Internet knowledge and computer knowledge.

Turning to gender, we find that the proportion of men is twice that of women (66.5% to 33.5% respectively) in the high profile, which generally coincides with the findings of Chen & Tsai (2007). However, these shares differ in the medium and low profiles; in the former, accounting for 48.8% of the sample total, women are in a majority7; in the latter, representing 39.6% of the sample total, women are in a minority. In other words, it is women rather than men who tend to make more use of Internet tools. This enables us to picture a scenario that favours women, which is a significant finding in the investigation that shows a reduced female presence in the high profile, with its broader and more intense Internet performance, but a greater presence in the medium and lower levels. Further investigation is needed to acquire more precise information on the true incidence of gender in the uses and intensity of use of the Internet among university students.

Differences appear in the intensity of use of the various Internet tools. The profiles show low intensity use of Internet in 40% of the student total; 49% register an average intensity and only 11% classify their use as high intensity. This leads us to think that an adequate infrastructure and appropriate incentives would significantly increase student use of the Internet and the range of tools and resources, particularly for academic work.

The profiles present differences and similarities between them, with the biggest differences occurring in these components: transactions-leisure, knowledge, downloads and social networks. The transactions-leisure component consists of variables that measure sales and purchases via Internet, watching television and on-line gaming, among others. The differences found in this component coincide with the user’s ability to access Internet and reveal a certain uniformity in relation to the profile; the knowledge component shows differences that are minimal and uniform while the higher the profile, the greater the number of years’ experience, the time spent on-line and the level of knowledge, all of which is directly related to the level of income; the download and social network components behave in such a way that the high and medium profiles have similar values while they differ significantly in the low profile.

The similarities found were contained in these components: usefulness, social tools, interactivity and databases. The first two have similar values in each of the profiles, the difference between them being that the usefulness component registers higher values than the social tools component, meaning that Internet is deemed useful for learning; yet the social tools are hardly used. The social tools component refers to the use of blogs, wikis and social markers in academic activities; the use of these tools is at a low level of intensity across the three profiles demonstrating that the culture of the use of resources and social tools could be better developed; something similar, although to a lesser degree, occurs with the interactivity and database access components whose intensity of use is low across the three profiles.

The low profile reveals several differences when compared to the other two profiles, which are limited to the download, transactions-leisure, knowledge and social network components. However, these limited differences do not necessarily mean that students can get better academic results from the time they spend on the Internet. The components that should best be developed for improving academic performance are: the use of social tools and resources, interactivity and access to databases. One particular characteristic of the low profile is the level of database use, which is higher than those of downloads, transactions and social use of tools and resources. This reveals a profile of students who prefer to use the time and information resources available to them to do academic work; yet this could also be due to the lack of knowledge and experience as internauts so typical of this profile.

An analysis of the profile graphs shows that they are all similar in form; the differences and similarities relate to the level of intensity assigned to the variables of each component; this enables us to determine the potential areas in which Internet use can be better exploited, and it would be very interesting to research which particular areas would benefit students’ academic performance the most.

Conclusions

The level of the student’s family income influences the use and intensity of use of Internet tools, so there is a difference or a digital divide that corresponds to socio-economic reality. The biggest differences between users appear in the variables that measure buying and selling on the Internet, gaming on-line, watching television and listening to music. These variables reveal the differences that exist between users, and are in line with the number of years of user experience, the number of hours and days spent on the Internet per week and knowledge level; gender is ambiguous in that only a third of women in the high profile use Internet tools but they are in a majority in the medium profile and in a minority in the low profile; this reveals that women generally make better use of the Internet than men.

An analysis of the profiles shows that low profile Internet users spend most of their time and resources on academic work when on-line; this changes in the medium and high profiles, and is attributable to the level of knowledge of these users, and the fact that they have more time to indulge in other on-line activities. The distribution of users into profiles that measure Internet use works against high level users who only account for 10% of the sample total. Yet far from being a drawback, this is an opportunity to foment technologies among university students and by extension to the entire educational system.

Notes

1 National Telecomunications and Information Administration.

2 Van Dijk (2005) considers that physical access is motivational, dependent on age, gender, race, intelligence among other factors.

3 Keil (2008) experimented with users of different socio-economic strata who were given access to Internet, and the behavioural differences were later examined.

4 www.uoc.edu/in3/pic/cat/index.html.

5 www.inec.gob.ec.

6 Consisting of these variables: Internet knowledge, computer knowledge, number of days and hours connected to the Internet and the number of years as a user.

7 Of the medium profile total, 58% are women.

Support

This research was financed by Ecuador’s Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (UTPL).

References

Castaño-Muñoz, J. (2010). La desigualdad digital entre los alumnos universitarios de los países desarrollados y su relación con el rendimiento académico. Revista de la Universidad y la Sociedad del Conocimiento 1; 43-52 (http://rusc.uoc.edu/ojs/index.php/rusc/article/view/v7n1_castano) (13-02-2011).

Castells, M. (2001). La Galaxia Internet: Reflexiones sobre Internet, empresa y sociedad. Barcelona: Areté.

Cebrián-Herreros, M. (2009). Nuevas formas de comunicación: cibermedios y medios móviles. Comunicar, 33; 10-13.

Chen, R. & Tsai, C. (2007). Gender Differences in Taiwan University Students Attitudes toward Web-based Learning. Cyberpsychology & Behavior: the Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 5; 645-54.

DiMaggio, P.; Hargittai, E. & al. (2001). Social Implications of the Internet. Annual Review of Sociology, 27; 307-336.

DiMaggio, P.; Hargittai, E. & al. (2004). Digital Inequality: from Unequal Access to Differentiated Use. In Neckerman, K. (Ed). Social Inequality. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 355-400.

Graham, R. (2010). The Stylization of Internet life? Predictors of Internet Leisure Patterns Using Digital Inequality and Status Group Perspectives. Sociological Research On-line, 5; (www.socresonline.org.uk/13/5/5.html) (10-03-2011).

Iske, S. & Klein, A. (2005). Differences in Internet Usage - Social Inequality and Informal Education. Social Work & Society, 2; 215-223.

Keil, M. (2008). Understanding Digital Inequality: Comparing Continued Use Behavioral Models of the Socio-economically Advantaged. MIS Quarterly, 1; 97-126.

Livingstone, S. & Helsper, E. (2007). Gradations in digital Inclusion: Children, Young People and the Digital Divide. New Media & Society, 4; 671-696.

Taylor, W.J.; Zhu, G.X. & al. (2003). Socio-economic Factors Affecting Home Internet Usage Patterns in Central Queensland. Informing Science Journal, 6; 233-246.

Tichenor, P.J. & Donohue, G.A. (1970). Mass Media Flow and Differential Growth in Knowledge. Public Opi-nion Quarterly, 2; 150-170.

Van Dijk, J. (2005). The Deepening Divide: Inequality in the Information Society. London: Sage.

Van Dijk, J. (2006). Digital Divide Research, Achievements and Shortcomings. Poetics, 4-5; 221-235.

Warschauer, M. (2003). Technology and Social Inclusion: Rethinking the Digital Divide. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wilson, E. (2006). The Information Revolution and Developing Countries. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Las tecnologías han transformado la educación superior impulsando cambios que han sido asimilados por la comunidad universitaria de distintas maneras. Como consecuencia, los estudiantes han presentado diversas formas y niveles de aprovechamiento de los recursos que nos ofrece Internet, delineándose brechas sutiles en la población universitaria. En este estudio se puntualizan algunas características de estas brechas; concretamente se analiza la incidencia de la variable ingresos del estudiante sobre los usos e intensidad de uso de las herramientas y recursos de Internet. Para lograrlo se clasificó a los estudiantes aplicando análisis factorial, complementado por análisis clúster para obtener perfiles de usuarios; estos perfiles se contrastaron con análisis discriminante y, finalmente, se aplicó chicuadrado para verificar la relación entre el nivel de ingresos y los perfiles de usuarios. Se determinaron tres perfiles con distintos niveles de las herramientas y recursos de Internet; y se comprobó estadísticamente la incidencia del nivel de ingresos en la conformación de estos perfiles. Se concluye que el nivel de ingreso incide mayormente en las variables que definen las posibilidades de acceso; el género tiene un comportamiento especial, puesto que, si bien el perfil más alto tiene el doble de proporción de hombres, las mujeres tienen un mejor desempeño en general.

1. Introducción

A pesar de la generalización del uso de Internet en todos los ámbitos, existen conglomerados que no pueden explotar de forma eficiente las ventajas que éste ofrece. Son varias las causas que ocasionan que la estructura social y económica aproveche de forma desigual la información y el conocimiento. Esta aseveración se enmarca en la teoría de brechas de conocimiento (Tichenor, Donohue & Olien, 1970) en la que al referirse a la información que generan los medios de comunicación, señalan que los estratos socio-económicos altos tienden a adquirir la información a un ritmo más acelerado que los estratos socio-económicos bajos. Esta teoría fue formulada considerando a la televisión y a los diarios como medios de comunicación; sin embargo, los medios de comunicación tradicionales tienden a ser absorbidos por los cibermedios y por Internet en general (Cebrián-Herreros, 2009), generando diferencias en los usos dados a la información, las herramientas que se utilizan, el nivel de intensidad, entre otros factores que configuran la denominada desigualdad digital.

DiMaggio, Hargittai, Rusell y Robinson (2001) señalan las diferencias encontradas en los informes de la NTIA1 en los años 1995-2000, en los cuales se ven favorecidos en el acceso a Internet quienes pertenecen a estratos socio-económicos más altos; estudios sobre brecha digital encuentran distintas variables como determinantes de los usos que se dan a las herramientas de Internet, lo que sustenta una relación entre la teoría de brechas de conocimiento y las implicaciones de la brecha digital.

DiMaggio, Hargittai, Celeste & Shafer (2004) plantean que quienes cuentan con acceso presentan diferencias en cuanto al uso que hacen de Internet, y van más allá del enfoque de las posibilidades de conexión, situando su análisis desde un contexto teórico más amplio que busca diferencias en los efectos del uso de Internet en las personas y en la sociedad. La brecha digital no viene dada solamente por condiciones de acceso a la tecnología y conexión; influyen también aspectos que determinan un buen uso de esa tecnología y de sus recursos. A este nuevo enfoque dado al término «brecha digital», algunos autores han coincidido en llamarlo «desigualdad digital».

Una revisión de la bibliografía existente muestra que la desigualdad digital generalmente es abordada desde dos enfoques. En el primero, los autores coinciden en analizarla desde las siguientes dimensiones: acceso, habilidades de uso, principales usos e intensidad de uso (Castaño, 2010; Van Dijk, 2005; Warschauer, 2003). El segundo enfoque se centra más en variables demográficas, entre las que predominan los ingresos, educación, raza, género, ocupación, edad, estructura familiar, entre otras (Castells, 2001; DiMaggio & al., 2004; Wilson, 2006). Al ir más allá de la segmentación en las dimensiones de análisis que se han mencionado, se puede notar que las primeras se adaptan a una relación de dependencia de las segundas2; es decir, el acceso, habilidades de uso, principales usos e intensidad de uso son variables dependientes de los ingresos, educación, edad, género, entre otras variables demográficas. De estas variables, los ingresos y la educación son los principales determinantes del nivel de desigualdad digital (Van Dijk, 2005) y del comportamiento del usuario frente a las tecnologías, cuando las limitaciones de acceso están controladas (Keil, 2008)3.

Existe una relación directa entre los niveles de ingreso de las familias y los niveles de uso de Internet (Taylor, Zhu, Dekkers & Marshall, 2003), lo que determina que la desigualdad digital sea una extensión de la desigualdad social y sus efectos vayan más allá de la dicotomía de estar o no conectado. Las diferencias pueden alcanzar a los nativos digitales. Se ha encontrado variación en los niveles de aprovechamiento de oportunidades y recursos en línea entre niños de clase media y niños de la clase trabajadora (Livingstone & Helsper, 2007). Esto implica que la incidencia de factores como la disponibilidad de una conexión en el hogar, el tiempo de conexión, entre otros pueden afectar el nivel de aprovechamiento; en el caso universitario, el nivel socioeconómico incide en los usos de Internet y estos en el rendimiento académico del estudiante (Castaño, 2010). A nivel macroeconómico también existe una relación directa entre el producto interno bruto (PIB) y la tasa de digitalización de los países (Iske, Klein & Kutscher, 2005). Si bien éste no es el único determinante es el más importante a la hora de analizar la dinámica de la brecha digital (Keil, 2008).

Existen diferencias notables determinadas por el nivel de educación. Los usuarios de mayor nivel educativo, generalmente hacen mejor uso del tiempo de conexión y de las herramientas y recursos de Internet (Graham, 2010; Van Dijk, 2006). El nivel educativo se constituye en la variable que tiene mayor efecto en el uso de Internet para actividades de búsqueda de información y comunicación (Iske & al., 2005; Graham, 2010) y determina que las necesidades de información, posibilidades y recursos sean distintos en cada usuario.

La brecha digital depende de factores sociales y económicos que delinean diferencias entre internautas. Estas diferencias configuran un conglomerado heterogéneo en cuanto a su conformación y al uso que hacen de la red. En este trabajo se analizan las diferencias en el uso de Internet en la universidad ecuatoriana; la relación que existe entre los ingresos en el núcleo familiar del estudiante y el uso de Internet. Se busca determinar si los niveles de ingreso más bajos difieren de los más altos en cuanto al nivel de aprovechamiento de recursos, hábitos de uso de Internet y niveles de intensidad.

2. Método

Fueron encuestadas 40 universidades ecuatorianas a las que se les solicitó información sobre: infraestructura tecnológica, política institucional y nivel de uso de herramientas virtuales en la formación. Se seleccionaron las cinco instituciones que obtuvieron los valores más altos y en cada una se levantó una muestra significativa, llegando a un total de 4.897 estudiantes encuestados. En cada institución y especialidad se mantuvo las proporciones de género en función del total de estudiantes matriculados a fin de preservar la mayor representatividad posible, quedando la distribución final con 50,5% de hombres y 49,5% de mujeres.

Las variables e instrumentos de recogida de información utilizados están basados en los empleados en el Proyecto Internet Cataluña4, adaptados a la realidad de América Latina. En esta investigación se trabajó con 31 variables divididas en los siguientes grupos: ingresos del núcleo familiar del estudiante, conocimiento y acceso a Internet, los usos académicos, los usos sociales y las percepciones del estudiante respecto a la utilidad de Internet. Las variables se pueden apreciar en la primera columna de la tabla 2. El nivel de ingresos se recogió a través de una escala que contiene los valores de los quintiles de ingreso del país, desarrollada por el Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos INEC5; las restantes variables se recogieron a través de una escala con niveles de 1 a 5.

Con la información recogida se procedió a clasificar a los estudiantes en función de los usos e intensidad de uso de Internet. Para ello se utilizó el análisis factorial para reducir la cantidad de variables a ocho factores que explicaron el 62% de la varianza. Estos se utilizaron como dato de entrada del análisis clúster, con el que se generó clasificaciones para tres, cuatro y cinco grupos. Finalmente se contrastó la constitución de los clúster aplicando análisis discriminante a cada clasificación. Este análisis tenía por objetivo determinar la clasificación más precisa, la variable dependiente fue el número de clúster al que pertenece el estudiante y las variables independientes fueron las restantes utilizadas en el análisis factorial.

La verificación de la relación entre los ingresos y el perfil de uso de Internet (clúster) se realizó utilizando la técnica chi-cuadrado que permite relacionar dos variables cuantitativas, a través de una hipótesis nula en la que se afirma que no hay relación entre las variables.

3. Resultados

3.1. Nivel de ingresos del núcleo familiar del estudiante

La distribución de estudiantes según el nivel de ingresos se la puede observar en la siguiente tabla. En ésta, los niveles corresponden a cada uno de los quintiles de ingreso de las familias de los estudiantes.

3.2. Perfiles de uso de Internet

El resultado de aplicar el análisis factorial entregó ocho factores (componentes) que explican el 62% de la varianza. El detalle de los mismos se puede apreciar en la siguiente tabla:

Los componentes resultantes se explican en función de las características de los estudiantes y se pueden diferenciar claramente entre ellos:

- Componente 1: Descargas. Caracteriza a los estudiantes que descargan de la red vídeos, programas y software en general.

- Componente 2: Transacciones-Ocio. Agrupa las características de compra y venta por Internet, ver televisión, escuchar radio, jugar en línea y seguir publicaciones periódicas.

- Componente 3: Conocimiento. Abarca las características que describen el nivel de conocimiento y experiencia del usuario.

- Componente 4: Utilidad. Se refiere a las percepciones del estudiante respecto a la utilidad de Internet en las actividades académicas.

- Componente 5: Herramientas sociales. Agrupa las características que refieren el uso de herramientas y recursos sociales en las actividades académicas.

- Componente 6: Redes sociales. Agrupa las variables referentes al uso de chat, correo electrónico y redes sociales.

- Componente 7: Interactividad. Se refiere al grado de interactividad que el estudiante mantiene con el profesor y con los estudiantes.

- Componente 8: Bases de datos. Únicamente abarca la variable que describe la intensidad de uso de bases de datos científicas y/o revistas en línea.

A los componentes descritos se les aplicó el análisis clúster y se obtuvo clasificaciones para 3, 4 y 5 grupos. Estas clasificaciones son:

Para verificar la validez de los clúster se aplicó análisis discriminante a cada clasificación. El resultado en cada caso nos indicó el porcentaje de elementos correctamente clasificados; así, en la clasificación de tres grupos, el 96,5% de los elementos de la muestra se encuentra correctamente clasificado; en la clasificación de cuatro grupos, el 92,4% de los elementos está correctamente clasificado; y, finalmente, en la clasificación de cinco grupos, el 90,3% de los elementos de la muestra se encuentra correctamente clasificado. Los resultados determinan que la clasificación con el menor número de grupos es la más precisa. De este análisis se desprende la decisión de trabajar con tres grupos.

En la siguiente figura se presenta la clasificación resultante del análisis discriminante.

Los nombres asignados a los perfiles se enmarcan en el contexto en el que se realiza la investigación, por lo que sus nombres no son comparables con otras realidades.

- Perfil alto: El clúster número uno representa al 11,6% de estudiantes, quienes tienen un nivel medio de descarga de vídeos, programas y en general de software: son los más experimentados y con más conocimiento en el uso de computadoras e Internet; perciben las herramientas de la red como útiles para el aprendizaje; son quienes más utilizan las redes sociales y herramientas de interacción; y utilizan las bases de datos de la biblioteca con mayor intensidad que los otros grupos.

- Perfil medio: El clúster dos abarca al 48,8% de estudiantes; los miembros de este grupo tienen semejanzas con los del primero. En todos los componentes tienen valores inferiores excepto en el nivel de descargas; la percepción de utilidad y el nivel de interactividad en donde son prácticamente iguales. Las mayores diferencias entre este grupo y el primero están en los componentes: transacciones, uso de herramientas sociales en las actividades académicas y uso de bases de datos, en donde los valores del primer grupo son visiblemente mayores.

- Perfil bajo: Este grupo es el que tiene la menor intensidad en el uso de las distintas herramientas, abarca al 39,6% de los estudiantes y, entre sus características principales que se considera, tienen un nivel medio de conocimiento y experiencia de uso de Internet; su percepción de que el uso de las herramientas de Internet pueden ser útiles para su formación, es bajo, e interactúan poco ya sea con profesores o con estudiantes. Este grupo realiza muy pocas descargas, prácticamente no realizan transacciones u ocio en línea, y el uso de herramientas sociales, redes sociales e interactividad es mínimo.

3.3. Verificación de las relaciones entre variables

La verificación de la hipótesis nula se realizó aplicando la técnica chi-cuadrado, el valor crítico para los parámetros dados es 20,09. El valor calculado de chi-cuadrado es 418,63 el mismo que es ampliamente mayor que el valor crítico y por tanto se rechaza la hipótesis nula.

Para complementar el análisis se calcularon los índices de correlación entre el nivel de ingresos y la proporción de estudiantes ubicados en cada nivel de la escala utilizada para levantar la información. Las variables consideradas fueron: nivel de conocimiento de computadoras, nivel de conocimiento de Internet, días de conexión a las semana, horas de conexión y años de experiencia como usuario. Se encontró correlación significativa en todas las variables. En el caso de las variables nivel de conocimiento de computadoras e Internet, fueron dos los niveles de la escala que no presentaron correlación significativa y en el caso de la variable días de conexión, fue solo el nivel 4 el que no presentó correlación significativa. El mismo fenómeno se puede apreciar en las actividades de chat, descargas de vídeos y programas y en el uso de redes sociales.

4. Discusión de resultados

El resultado de aplicar chi-cuadrado para verificar la hipótesis nula determinó el rechazo de la misma, por tanto se concluye que el nivel de ingresos incide en los perfiles de uso de Internet de los estudiantes. Sin embargo, hay más evidencia que corrobora este hallazgo. Al analizar la distribución de los niveles de ingreso en cada perfil, encontramos que los estudiantes con mayores posibilidades económicas se encuentran en mayor proporción en el perfil alto; por el contrario, quienes cuentan con menores ingresos tienen mayor presencia en el perfil bajo. Esto concuerda con las diferencias encontradas por DiMaggio y otros (2004) en cuanto al uso de Internet y niveles de ingreso.

Los coeficientes de correlación entre el nivel de ingresos y las variables del componente conocimientos6 son significativos. Sin embargo, es deducible que, mientras mayor sea el nivel de ingresos de una familia, mayor es la posibilidad de contar con un computador y una conexión a Internet; y mientras más años de experiencia tiene un usuario, mayor será su conocimiento, días y horas de conexión. A pesar de ello, al ordenar la correlación de mayor a menor, encontramos que el nivel de ingresos incide mayormente en los años de experiencia como usuario, seguido de horas de conexión por cada sesión, días de conexión a la semana, nivel de conocimientos de Internet y nivel de conocimientos de computadoras.

En cuanto a la incidencia del género, se encontró que en el perfil alto, la proporción de hombres es el doble que de mujeres (66,5% y 33,5% respectivamente); esto de manera general coincide con los hallazgos de Chen y Tsai (2007). Por otro lado, en los perfiles medio y bajo las proporciones no mantienen la misma distribución; en el perfil medio que representa el 48,8% del total de la muestra, las mujeres son mayoría7; en el perfil bajo que representa el 39.6% del total de la muestra, las mujeres son minoría; dicho de otro modo, quienes más utilizan o aprovechan las herramientas de Internet, son en su mayoría mujeres. Esto permite delinear un panorama en el que la mujer se ve favorecida, representando un hallazgo significativo en el contexto de la investigación que se resume con una presencia muy desfavorable en el nivel con mejor desempeño e intensidad, y, con ventaja en los niveles medio y bajo. Es necesario profundizar aquí la investigación para contar con información más precisa respecto a la real incidencia del género en los usos y niveles de uso de Internet en los estudiantes universitarios.

La diferenciación obtenida se basa en la intensidad de uso de las distintas herramientas. En los perfiles se puede notar que cerca del 40% del total de estudiantes utiliza Internet con una intensidad baja; el 49% tiene una intensidad media; y solo el 11% tiene una intensidad de uso alta. Esto deja abierta la posibilidad de que con la infraestructura e incentivos adecuados, la población universitaria pueda crecer significativamente en los niveles de uso y en diversidad de herramientas y recursos especialmente con fines académicos.

Los perfiles resultantes tienen diferencias y semejanzas entre sí. Las mayores diferencias están constituidas por los componentes: transacciones-ocio, conocimiento, descargas y redes sociales. El componente transacciones-ocio está conformado por las variables que miden la compra y venta por Internet, ver televisión, jugar en línea, entre otras; las diferencias encontradas en este componente concuerdan con las posibilidades de acceso de los usuarios y presentan cierta uniformidad en relación con el perfil; el componente conocimiento presenta diferencias mínimas y uniformes, mientras mayor es el perfil, mayores son los años de experiencia, el tiempo de conexión y el nivel de conocimientos, lo que guarda relación directa con el nivel de ingresos; los componentes descargas y redes sociales presentan un comportamiento en el que los perfiles medio y alto tienen valores similares y difieren significativamente del perfil bajo.

Las semejanzas encontradas abarcan los componentes: utilidad, herramientas sociales, interactividad y bases de datos. Los dos primeros tienen valores semejantes en cada uno de los perfiles, la diferencia entre ellos radica en que el componente utilidad presenta valores mayores que el de herramientas sociales, esto significa que Internet se considera útil para el aprendizaje; sin embargo, las herramientas sociales se utilizan muy poco. El componente herramientas sociales se refiere al uso de blogs, wikis y marcadores sociales en actividades académicas; el uso de estas herramientas presenta una intensidad baja en los tres perfiles, lo que demuestra que la cultura de uso de recursos y herramientas sociales es un área susceptible de mayor explotación; algo similar, aunque en menor magnitud, ocurre con los componentes interactividad y acceso a bases de datos en donde los niveles son bajos en los tres perfiles.

El perfil bajo presenta diferencias con los perfiles restantes, los componentes en los que estas diferencias pueden reducirse son: descargas, transacciones-ocio, conocimientos y redes sociales. Sin embargo, la reducción de estas diferencias no necesariamente significa que el estudiante pueda obtener mayores beneficios académicos del uso que le dé a su tiempo conectado. Los componentes que deberían recibir mayor fomento en busca de mejoras académicas son: el uso de herramientas y recursos sociales, la interactividad y el acceso a bases de datos. Hay un hecho especial que caracteriza al perfil bajo, el nivel de uso de bases de datos es mayor que los niveles de descargas, transacciones, y uso de herramientas y recursos sociales. Esto delinea un perfil de estudiante que prefiere aprovechar en actividades académicas, los recursos de información y tiempo de los que dispone; sin embargo, también podría estar alentado por la falta de conocimiento y experiencia como internauta que se le atribuye a este perfil.

Al analizar las gráficas de los perfiles podemos notar que todas tienen una forma similar; las diferencias y semejanzas pasan por el nivel de intensidad asignado a las variables de cada componente, lo que nos permite determinar áreas potenciales en las que el uso de Internet puede explotarse más, y sería de gran interés investigativo determinar qué áreas son especialmente beneficiosas en el aspecto académico de los estudiantes.

Conclusiones

El nivel de ingresos del núcleo familiar del estudiante incide en los usos e intensidad de uso de las herramientas de Internet, por tanto existe una diferenciación o brecha que se ajusta a la realidad socioeconómica. Las mayores diferencias entre usuarios están dadas por las variables que miden la compra y venta por Internet, jugar en línea, ver televisión y escuchar música. Estas variables diferencian plenamente a los usuarios y concuerdan con los años de experiencia como usuario, el número de días y horas de conexión a la semana y el nivel de conocimientos; el género presenta un comportamiento ambiguo; el perfil alto cuenta con solo un tercio de mujeres, sin embargo, éstas son mayoría en el perfil medio y minoría en el perfil bajo; esto equivale a que en general su desempeño y aprovechamiento sea mejor que el de los hombres.

Al analizar los perfiles resultantes se encuentra que los usuarios del perfil bajo utilizan la mayor parte del tiempo y recursos en actividades académicas; esto cambia en los perfiles medio y alto y se debe al nivel de conocimiento que presentan estos usuarios, que se pueden dedicar también a otras actividades. La distribución de usuarios por perfil de uso no es favorable con los usuarios del nivel más alto, quienes alcanzan únicamente alrededor de la décima parte del total. Esto, más allá de verse como desventaja, representa una oportunidad para fomentar las tecnologías en la población universitaria, y por ende en el ámbito educativo.

Notas

1 National Telecomunications and Information Administration.

2 Van Dijk (2005) considera al acceso físico, motivacional como dependiente de la edad, género, raza, inteligencia, entre otros factores.

3 Keil (2008) experimentó con usuarios de distintos estratos socioeconómicos a quienes se dotó de acceso a Internet y se examinaron las diferencias luego de un período de tiempo.

4 Véase: www.uoc.edu/in3/pic/cat/index.html.

5 Véase: www.inec.gob.ec.

6 Conformado por las variables: conocimiento de Internet, conocimiento de computadoras, días de conexión, horas de conexión y años como usuario.

7 Del total de usuarios que pertenecen al perfil medio, el 58% son mujeres.

Apoyos

Esta investigación ha sido financiada por la Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (UTPL) de Ecuador.

Referencias

Castaño-Muñoz, J. (2010). La desigualdad digital entre los alumnos universitarios de los países desarrollados y su relación con el rendimiento académico. Revista de la Universidad y la Sociedad del Conocimiento 1; 43-52 (http://rusc.uoc.edu/ojs/index.php/rusc/article/view/v7n1_castano) (13-02-2011).

Castells, M. (2001). La Galaxia Internet: Reflexiones sobre Internet, empresa y sociedad. Barcelona: Areté.

Cebrián-Herreros, M. (2009). Nuevas formas de comunicación: cibermedios y medios móviles. Comunicar, 33; 10-13.

Chen, R. & Tsai, C. (2007). Gender Differences in Taiwan University Students Attitudes toward Web-based Learning. Cyberpsychology & Behavior: the Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 5; 645-54.

DiMaggio, P.; Hargittai, E. & al. (2001). Social Implications of the Internet. Annual Review of Sociology, 27; 307-336.

DiMaggio, P.; Hargittai, E. & al. (2004). Digital Inequality: from Unequal Access to Differentiated Use. In Neckerman, K. (Ed). Social Inequality. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 355-400.

Graham, R. (2010). The Stylization of Internet life? Predictors of Internet Leisure Patterns Using Digital Inequality and Status Group Perspectives. Sociological Research On-line, 5; (www.socresonline.org.uk/13/5/5.html) (10-03-2011).

Iske, S. & Klein, A. (2005). Differences in Internet Usage - Social Inequality and Informal Education. Social Work & Society, 2; 215-223.

Keil, M. (2008). Understanding Digital Inequality: Comparing Continued Use Behavioral Models of the Socio-economically Advantaged. MIS Quarterly, 1; 97-126.

Livingstone, S. & Helsper, E. (2007). Gradations in digital Inclusion: Children, Young People and the Digital Divide. New Media & Society, 4; 671-696.

Taylor, W.J.; Zhu, G.X. & al. (2003). Socio-economic Factors Affecting Home Internet Usage Patterns in Central Queensland. Informing Science Journal, 6; 233-246.

Tichenor, P.J. & Donohue, G.A. (1970). Mass Media Flow and Differential Growth in Knowledge. Public Opi-nion Quarterly, 2; 150-170.

Van Dijk, J. (2005). The Deepening Divide: Inequality in the Information Society. London: Sage.

Van Dijk, J. (2006). Digital Divide Research, Achievements and Shortcomings. Poetics, 4-5; 221-235.

Warschauer, M. (2003). Technology and Social Inclusion: Rethinking the Digital Divide. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wilson, E. (2006). The Information Revolution and Developing Countries. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Document information

Published on 30/09/11

Accepted on 30/09/11

Submitted on 30/09/11

Volume 19, Issue 2, 2011

DOI: 10.3916/C37-2011-02-08

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?