Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This paper has two purposes: one conceptual and the other practical. On a conceptual level, it outlines a model for understanding how TV operates as a social mediator in the event of natural disasters, and at the practical level, it recommends measures that can be used to optimize the role of TV and its ideal social function in contexts of crisis. This model views TV intervention as both «self-centered», that is, driven by its reproduction as a media consumption company; and «socially-centered», designed to respond swiftly and accurately to the social requirements that emerge in crisis situations. The suggested model is to be contrasted with the results of a research study conducted by the National TV Council of Chile that explored the role of TV broadcasting after the earthquake in February 2010. According to the results of the study, audiences value the amount of information broadcasted by TV networks but perceive that the predominance of its «self-centered» function creates a problem: the logic of the 'spectacle' is prevalent and exacerbates the audience’s emotions. The primary purpose of this paper is to develop a strategy to recommend how TV and its associate services can respond to a crisis situation while respecting the tragedy of natural disasters.

1. Introduction

On February 27, 2010, Chile suffered an 8.8-magnitude earthquake – considered the fifth largest of its kind – and a subsequent tsunami, which together left nearly eight hundred people dead, five hundred thousand homes destroyed or severely damaged, and around two million people homeless.

Free to air TV played an important role, but the way in which it covered this event has been the subject of much public debate. Although it excelled in its role of providing information about what was happening and the decisions made by the authorities at different moments throughout the tragedy and in its support in searching for missing people, it has also been questioned because of its supposed emphasis on the most tragic and violent consequences of the earthquake.

The debate has been tied to three fundamental issues: the role of TV in face of a natural disaster; journalistic ethics regarding the coverage of natural disasters; and the effects of TV broadcasting on the opinion of the audience. In response to these circumstances, the National TV Council of Chile (CNTV) carried out a study aimed at understanding the role assumed by TV during this catastrophe (National TV Council of Chile, 2010).

Within this context –and based on the results of this study– the purpose of this paper is to present the basis of a model that allows us, on the one hand, to understand the intervention of TV in disaster scenarios and, on the other, to see which elements are needed to make this intervention more planned, systematic and pertinent.

Based on a dynamic concept of reality (that attempts to overcome the more passive and static focus of perception analysis), in this model we conceive the TV broadcastings as a kind of intervention in different scenarios caused by the earthquake.

This interventional component of TV is widely recognized by organizations such as the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), which have come up with protocols aimed at regulating this intervention and directing it towards minimizing the psychological impact of crisis, respecting the dignity and self-esteem of the people and communities affected, and promoting solidarity and social cohesion, among others (Pan American Health Organization, 2006).

The logic behind TV intervention unfurls a double function. On the one hand, it plays a self-centered function, and on the other, a socially-centered one. Both functions are closely united within the logic of intervention.

Under its self-centered function, TV as a company reproduces itself fundamentally through the construction of audiences. Under its socially-centered function, TV responds to the multiple and urgent requirements posed by the different scenarios caused by the crisis.

From this perspective, TV has the ability to act on its audiences, turning them into relevant actors in the construction of the chaotic social response generated by the earthquake. This interventionist capacity is based on its extensive and intensive power. TV is present in 92.4% of Chilean homes (Census, 2002) with an average of 2.4 TV sets and average consumption of 2.5 hours a day (National TV Council of Chile, 2008), which explains its extensive power: omnipresent in the daily lives of Chileans, it intervenes in the dynamics of coexistence. From its intensive power, TV acts on the identities, emotions, self-esteem, and the symbolic integration of people.

Under its socially-centered function, which is of primary interest to us in this text, TV can intervene in at least two ways. First, by providing people with important elements to construct their own actions in their immediate surroundings in time of crisis, and second, in the configuration of accustomed ways to react to these situations; -this is extremely important for future crisis scenarios that are fairly frequent in Chile-.

From this «dynamic-active» perspective, we pose the following questions: How does TV intervention contribute to the construction of «adaptive» actions of the people and the development of coexistence in each of the situational scenarios generated by the crisis (affected areas, partly affected, and non-affected areas)? How do citizens react to this intervention? What were the positive aspects perceived in the intervention and what were the most questioned? What kind of intervention is expected of TV? The following data and reports help answer these questions, and therefore will gradually construct and validate the proposed model, which will be drawn from the results of the mentioned study carried out by the CNTV, whose design we will describe below.

2. Methodology

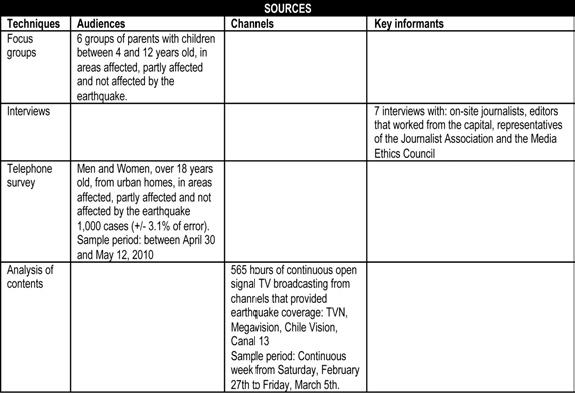

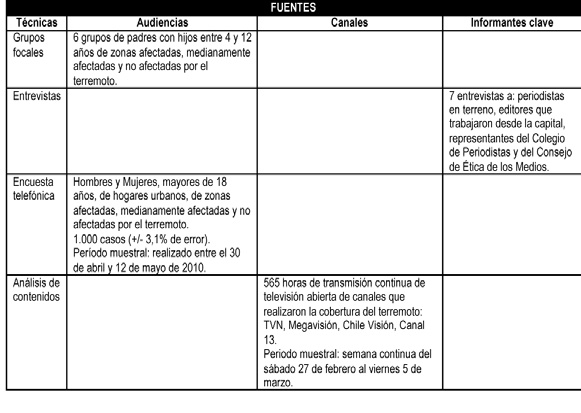

At first, we will systematize the main results of the study in order to then go deeper in their interpretation, taking from them some basic guidelines for the elaboration of the desired model. The main objective of the study was to understand and describe the role assumed by TV in this catastrophe. To do this, a double triangulation method was used: on the one hand, between quantitative (telephone survey, analysis of screen contents) and qualitative techniques (focus groups and interviews); and on the other hand, between different sources (people in affected areas, partly affected areas and areas not affected by the earthquake; screen contents, and key informants).

Table 1. Study Methodology

3. Results

The results will be presented based on two categories: the way in which TV constructed its intervention and the reactions of audiences.

3.1. Intervention

During the week immediately following the earthquake, 98% of all broadcasting was concentrated and continuously dedicated to the catastrophe and its consequences. The remaining time was used for movies and TV series. Based on the screen analysis, in this section, we will be referring to the most used format for coverage, the main issues discussed, the main participants and their evolution of appearance, and finally the TV resources that generated the most emotional impact for the audiences.

The most used format in TV broadcasting from February 27th to March 5th was «developing news» (76.8%), where the story was accompanied by images and active sources (reporting, commentary, interviews, home videos and others), followed at a great distance by the «interview» (7.9%). The majority of broadcasting included on-site reporting, but the highest percentage of images transmitted were pre-recorded (65.9%), which, according to the study, shows that there was time to decide what information would be presented on-screen. The prerecorded news stories were concentrated primarily on March 1st, (recapitulation of broadcast news), and on March 3rd (previews of the aid campaigns). What were the main issues covered?

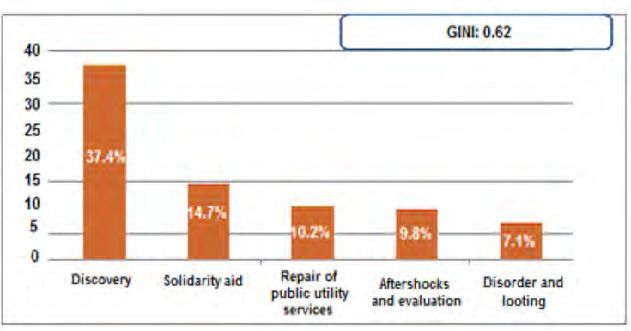

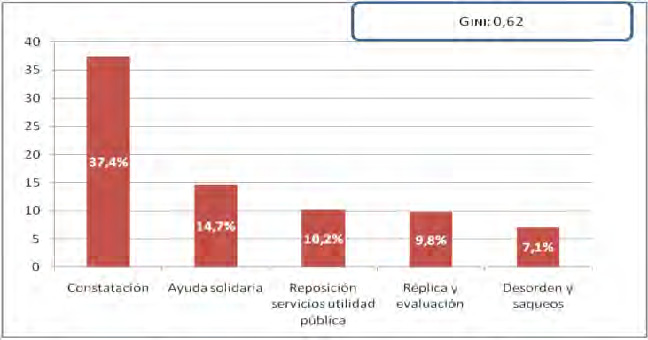

Graph 1. Main topics discussed on-screen

As is shown in Graph 1, of the five most covered topics during the week of the earthquake (nearly 80% of all issues discussed on screen), the most frequent one was the «discovery and verification of material and human damage». For this dimension, the Gini coefficient is calculated at 0.62, confirming a significant concentration of topics. How did the presence of these topics evolve during the first week?

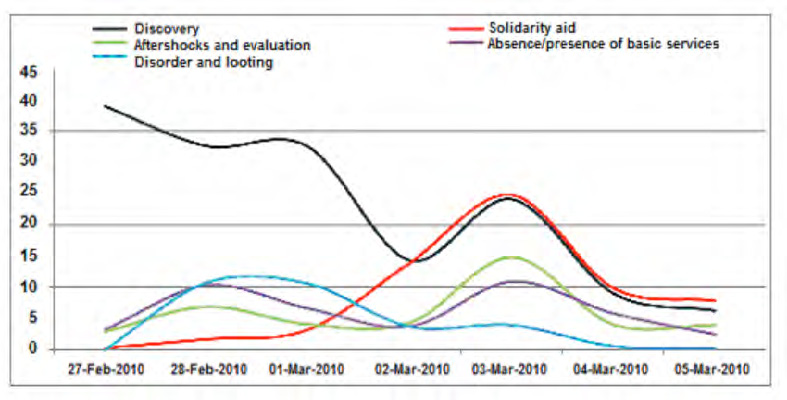

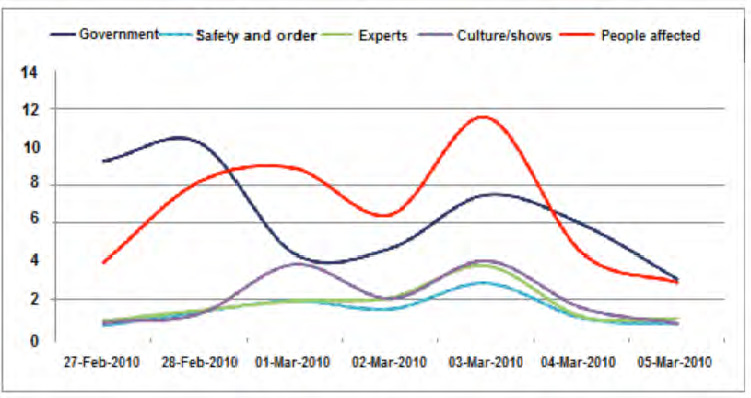

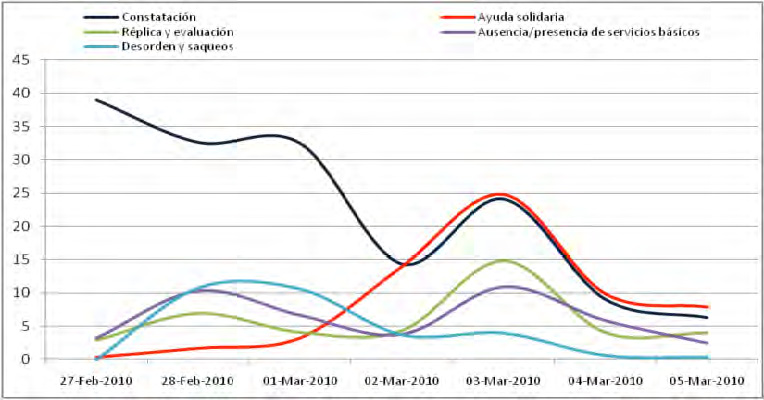

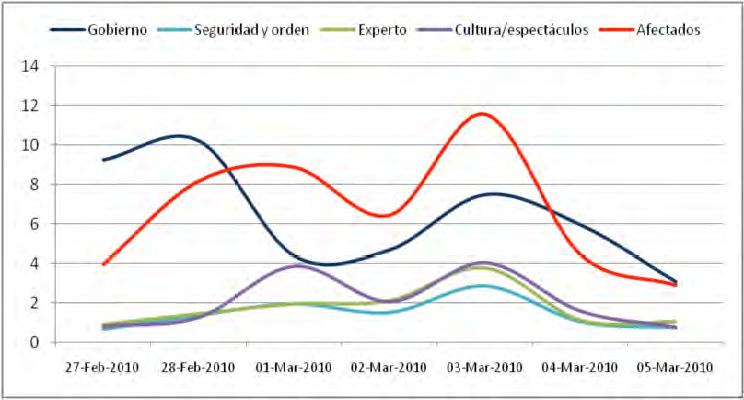

Graph 2. Evolution of topics discussed on-screen

Graph 2 shows a pronounced and sustained decrease in the topic of discovery and verification of material and human damage, and a gradual increase in the topic of solidarity aid. Both topics decreased towards the end of the week.

The issue of the absence/presence of basic services is seen to have two high points: on February 28th and on March 3rd. The first refers primarily to the absence of services, while the second informs the repair of services such as drinking water, supermarkets and electricity. The topic of disorder and looting obtained its highest point during the first few days, decreasing considerably later on in the week, when the most important topics were the evaluation of damages and repair of services. Who were the actors that participated in the discussion of these issues and how much time were they present on-screen?

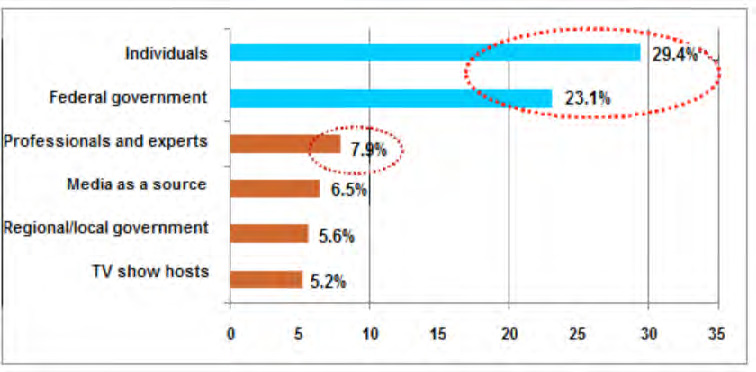

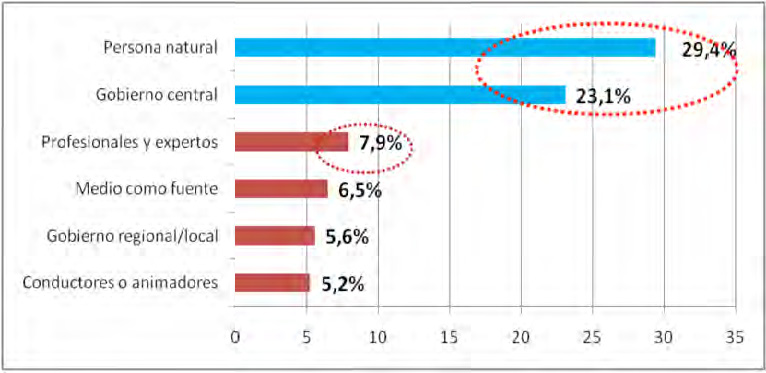

Graph 3. Actors most present in earthquake coverage during the week

As seen in the graph, individuals and Federal government sources account for more than half of the time dedicated to information sources (52.5%). This concentration (Gini coefficient: 0.65) is proof of how journalistic news is constructed based on testimonies and opinions of people affected, and the emotional sources of the victims, more than expert information of the local authorities.

How did the participation of these actors evolve on-screen during the first week of the earthquake?

Graph 4. Evolution of presence of actors on-screen

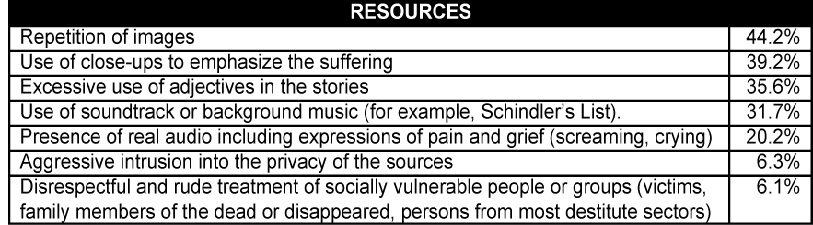

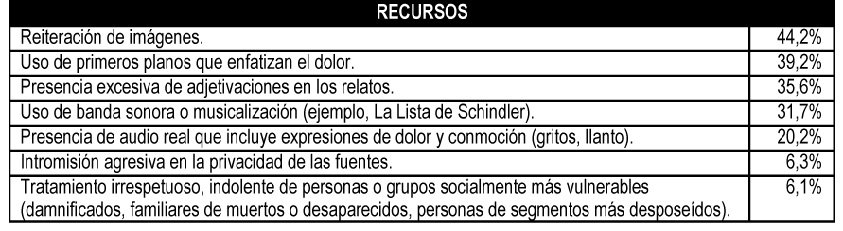

The graph shows a sharp change in the presence of institutional actors (central, regional and local government) in relation to the affected people, as a source of information. While the former were the most predominant actors in TV content during the first two days, the affected people increased their presence throughout the week, reaching a high point on March 3rd. On several occasions, the communications media teams arrived on-site even before the authorities and rescue teams from Santiago, becoming the object of urgent demands for aid from the affected people, demands that these teams, on the one hand, were not prepared to meet, and on the other, had not contemplated in their work. An important aspect of the TV intervention is seen in the impact that it had on the emotions of the audiences. According to screen analysis, the resources used by TV that generated the most emotional impact were the following:

Table 2. Resources that generated the most emotional impact

The systematic use of these resources shows an emphasis on the dramatic construction of the news.

3.2. How did audiences react to this intervention?

Taking the survey and focus groups as a reference, in this section we will look at both, the most criticized aspects of TV intervention, that is, the emotional impact on children, the coverage of looting, sensationalism1, the invasion of privacy and lack of explanatory information, and the most valued aspects. Of those surveyed, 56% watched more TV than usual. Only 18% stated having watched less TV during the days following the earthquake. According to the survey, the images of destruction and general devastation (40%), coastal devastation (39%), suffering of the people affected (8%) and looting (5%) were those that most impacted the audiences. On the other hand, during the qualitative part of the study, it was the TV coverage of looting that most left an impression with those interviewed, independent of their socioeconomic status or where they live. What emotional reactions did these images activate?

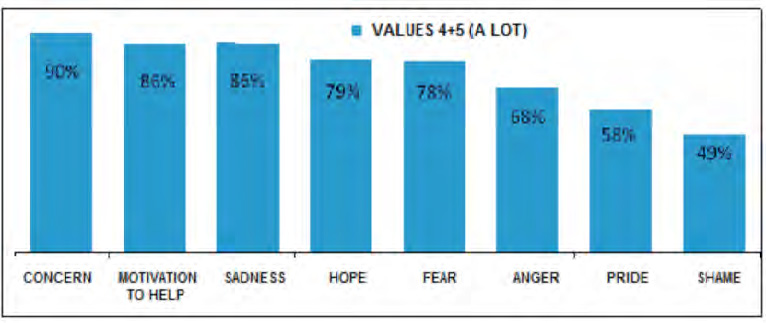

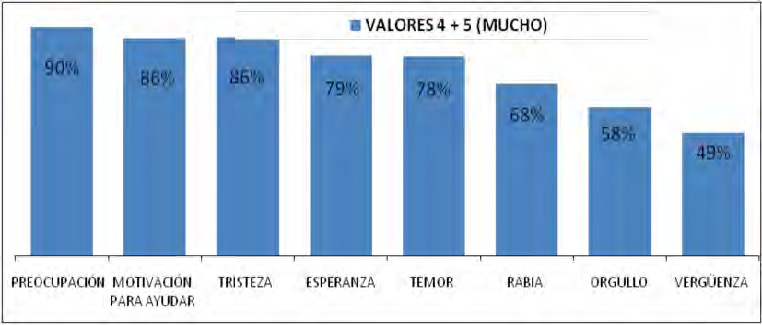

Graph 5: Emotions activated by TV

According to Graph 5, the emotional reactions activated went from concern (90%) to shame (49%), also including motivation to help (86%), sadness (86%), hope (79%), fear (78%), anger (68%) and pride (58%). It is on this level that TV intervention is most questioned, especially when it has to do with children, 68% of whom, according to the survey, followed the TV coverage of the catastrophe.

According to the qualitative part, the child population experienced recurring reactions of anguish, insecurity, nightmares, fear of being alone, insomnia and fear of visiting places such as the beach in the case of Iquique (a coastal city in an area of the country not affected by the earthquake). It seems that here there was an emotional saturation that caused parents to regulate their children’s consumption of TV and led to a strong criticism of the TV channels because of the explicit content broadcast during viewing times dedicated to all audiences and the absence of more relaxing programs that would have benefited children and their families.

The images of looting fundamentally triggered reactions of surprise and shame. The surprise was associated with the unexpected (not only delinquents were involved) and their incomprehensible nature, from a moral standpoint, of these actions. The shame was associated with the country’s loss of symbolic capital, a breakdown in self-esteem and a significant loss of community cohesion.

Criticism of sensationalism, where the dramatic construction of the news surpassed its informative component, was a recurrent theme for those interviewed, who believe that there was «exaggeration», «excess» and «manipulation» aimed to obtain higher ratings than the other channels that were covering the catastrophe. The excessive repetition of explicit and highly emotional images was one of the resources of TV construction that was most visible for the audiences (mentioned by 81% of the people consulted). This criticism by the audiences of «sensationalism» has been repeated over and over again with notable regularity (59%) in the tri-annual survey carried out by CNTV (National TV Council of Chile, 2008).

Likewise, TV viewers experienced the uncomfortable feeling that by including people from show-business2 in the TV coverage of the earthquake entailed downplaying the seriousness of the situation and the tragic meaning of the events, and an attack against the dignity and respect of people who were experiencing the harsh reality of the catastrophe. Once more, this practice was associated with an (unscrupulous) attempt to obtain higher ratings.

Another form of TV intervention that was questioned was the invasion of intimacy with the repeated use of emotional sources motivated by an artificial search for news stories, without respecting the rhythm of the interviewees, their dignity or their right to privacy.

According to journalists consulted, one of the weaknesses shown by TV intervention was the predominance of a primarily descriptive discourse about the events, with detriment to «explanatory information»: journalists must be didactic. From this point of view, this weakness is particularly criticized in a context in which the people tend towards «pure emotions» and require elements to help them face the situation with a certain level of rationality.

What was most valued by TV viewers? The most valued aspect by the audiences was the information provided that allowed them to create a very complete view of what had happened and, depending upon the different scenarios and locations of the informants, to form an idea of concrete ways to take action during this situation. In general, the people consulted considered that TV did a good job in its informative coverage of aspects related to the catastrophe, providing useful information for the situation.

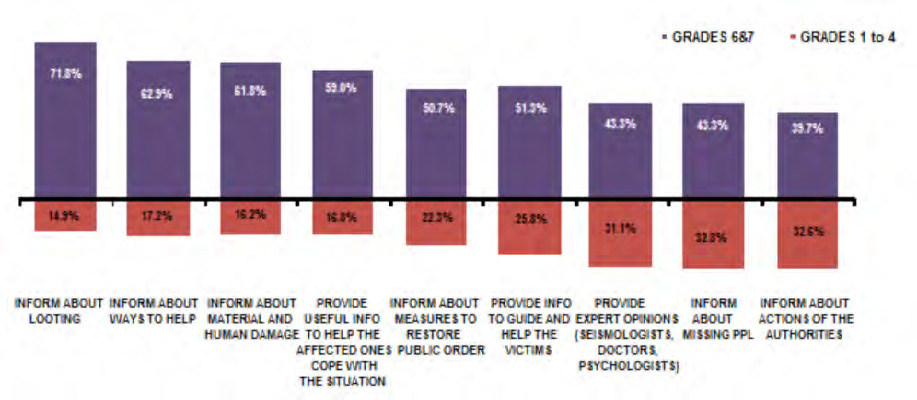

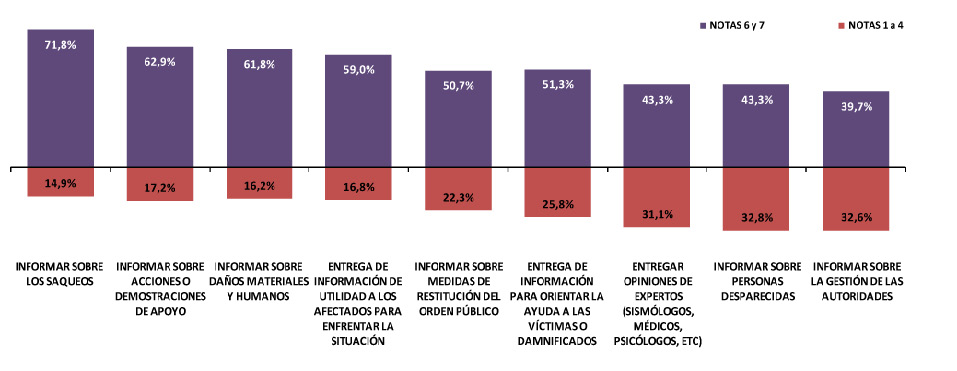

Graph 6. Evaluation of the informative role of TV

At the same time, TV was considered more effective when presenting testimonies of the victims (62.7%), giving hope (51.4%) and calming people (43.7%). TV intervention can then be seen as having a calming and supportive effect, often meeting the function of companionship and facilitation of coexistence.

What did audiences expect from TV? For audiences, especially those located in areas of crisis, TV did not adequately respond to the more situational and urgent needs generated at the scene of the catastrophe. In fact, they complained that TV should serve a role of public service: personalized support, instrumental help and practical guidance. Its intervention was perceived as more informative than giving guidance, more universal than local, more distant than close and many times catering to other priorities and interests rather than to those of the people, in contrast to the radio stations that provided practical and effective services, showing itself to be a much more situational media that is close to the local dynamics, of easy access to the immediate demands of the people and communities affected. Finally, TV is assigned a relevant role in the reconstruction (according to 95% of those interviewed) that includes other activities such as «supervising the completion of reconstruction programs» (40%), «organizing, supporting and promoting aid campaigns» (29%), and «showing the accomplishments and progress of reconstruction» (24%).

4. Discussion

The main thesis of the proposed model conceives the role of TV as an intervention that goes beyond the merely informative to have a real impact on people. TV intervenes, so to speak, «on-site» at the scene of the catastrophe: although it acts individually on people, TV intervenes in what they have in common, in their coexistence, in their framework of action, in their shared emotions, in their support structures, in their symbolic capital, in the collective understanding of the situation, in their feelings of belonging and the psychological meaning of community.

TV intervenes on-site from a double-function, one self-centered and the other socially-centered. Both functions are inseparable components in the same intervention process. However, this double function is perceived as problematic by the actors consulted in the study. Where TV, in a self-centered logic, gives priority to its own interests in the construction of its audience, this intervention generates problems for TV viewers. But where TV is a socially-centered logic and directs its intervention straight towards vital and urgent needs of the people and communities affected, its presence becomes essential for the configuration of adaptive actions and the management of coexistence at the scene of crisis.

From the language of Zubiri (2004: 197-207) we hypothesize that TV proposes for its viewers a perceptive field of the catastrophe organized mainly from the «logic of spectacularity», from one that fixes its horizon, close-ups, background and surroundings. The earthquake generated a spectacular scenario, with buildings that collapsed, the ocean invading the coastal towns, boats transported to the town square, fatalities, people in the state of profound suffering and emotional activation. The spectacular nature of these images, associated with a degree of high uncertainty, became an opportunity that TV could not miss out on: it had before itself a «real reality show», at zero cost, that it really knew how to take advantage of effectively.

Within this context, one of the most «spectacular» events was the looting. What was spectacular here was the loss of community, the falling apart of social cohesion, the abrupt break with the routine course of life that, like all things that go against the norm, intensively moves the emotions (Tetu, 2004: 16). This TV strategy had the effect of spreading community distrust, increasingly confining communities that were already closed off, giving them aggressive, violent and threatening closure. Paradoxically, TV produced social cohesion in its audiences precisely because of the breakdown in community social cohesion during the earthquake, exploiting here –from a more Hobbesian vision– the ghost of community loss, of man against both man and the supermarkets, of man’s secret fear of insecurity and disorder, of man as a werewolf (Homo Homini Lupus) (Esposito, 2007: 55-58).

In the coverage of these «spectacular» events, journalists many times tend to be confused with TV hosts, and audiences cannot manage to differentiate collective solidarity from the promotion of the media brand’s image. In this spectacular position of the world (in which the earthquake was confused with a stage production, journalists with TV hosts, and information with entertainment) the TV viewer becomes a mere spectator and information a mere spectacle (Mathien, 1993).

TV viewers clearly identify the strategy of emotional activation used by TV to meet its objective of constructing its audiences. This activation, fundamentally in a negative tone, operates upon a psycho-emotional surface that has already become hyperactive because of the real events of the earthquake, in this way generating a risk of emotional saturation, especially among children.

The live transmission, being both on-site and in real-time – a modality preferred by TV to show catastrophic events – contributed greatly to this over-activation. This type of broadcasting has generally been highly criticized because it offers a minimum distance in relation to the broadcast event. It is precisely this characteristic that makes live broadcasting an opportune area for intense emotional activation, since it gives a lot of room to the unexpected, presenting the reality of an event open to multiple and dramatic outcomes that will be resolved in real time and before the viewers’ eyes. According to Tetu, this way of presenting an event hands over to the TV viewer the role and responsibility of interpreting the action taking place before their own eyes (Tetu, 2004). From the perspective of Mathein, «in a logic of media exploitation of real events, the scenario of live broadcasting from the site of the catastrophe is practically no different from the transmission of a spectacle or show» (Mathien, 1993: 67).

But at the same time, the strong impact generated by the images of destruction and desolation, together with the impossibility of the TV viewer to act immediately in the area of the catastrophe and the unbearable emotion of remaining impassive to the suffering of others, activates different types of gestures of solidarity from the viewers, in this way contributing to the implementation of multiple forms of help (Tetu, 2004:13).

The study shows a critical and proactive TV viewer, with the ability to recognize the logic of TV intervention, anticipating and recognizing its objectives, and, in their own fields of action and control, to generate practices of self-regulation aimed to protect the mental health of their children, in order to prevent a stage of negatively-charged emotions. This new kind of viewer has shows a relatively autonomous confrontation with TV intervention, which can be highly relevant for a media education policy in this area.

TV intervenes, but its intervention is not planned. The results of this study allow us to see some operative elements for the design of a planned, systematic and pertinent intervention of TV in this type of catastrophe. During catastrophes, TV must maintain a predominant approach directed towards its socially-centered function, in this way giving secondary priority to its self-centered function.

On a more operative level, it must integrate itself into the local and national crisis intervention plan that coordinates and provides instructions for institutions, social organizations and communities under the following general guidelines:

- Respect for the dignity and rights of people affected.

- Constructive help and support for the development of adaptive actions: a central aspect of TV interaction is maintaining the population informed about what has happened (showing the material and human damage produced) and the evolution of events. This makes it possible for people to make the best possible decisions with regards to what actions they will take.

- In association with the above guideline, TV must contribute to the emotional containment of the people affected and the development of a sense of security, self-confidence and tranquility to lessen the psychological impact of the crisis, making it possible for people to act from a more stable emotional state. This implies avoiding working from the logic of spectacularity, a shift towards sensationalism, the emotional over-activation and the systematic use of emotional sources of news.

- TV must contribute at all times to adequate institutional-community (re)coordination at the scene of the crisis, avoiding unnecessary tensions and strengthening the community’s trust in the institutions and organizations providing aid.

- The intervention must stimulate and strengthen community support as a source of security, aid, stability and belonging for the people, so as to contribute to the strengthening of the psychological sense of community.

- TV must play a crucial role in the reconstitution of national symbolic capital and the recuperation of social cohesion.

- It must also take on the functions of a public service channel, facilitating aid campaigns and searches for missing people, providing information about the functioning of basic services and specialized information from experts in order to better understand the phenomenon.

- This all implies that we need to include within the formation and preparation of communications professionals contents related to media education, models of crisis intervention and networking with institutional and community organizations.

- The main idea is that TV must break away from its form of crisis intervention that is predominantly self-centered, which can bring with it the risks analyzed in this paper, and take on an effective form of crisis intervention that plays a socially-centered role, placing its constructive potential at the service of the community.

Notes

1 Trend of communications media to exacerbate or abuse emotions with the objective of impacting the audience.

2 Refers to the Spanish term «farándula», which are programs with or about celebrities.

References

Consejo Nacional de Televisión de Chile (2008). VI Encuesta Nacional de Televisión (www.cntv.cl). (www.cntv.cl/medios/Publicaciones/2009/VI_Encuesta_Nacional_TV.pdf) (09-09-2010).

Consejo Nacional de Televisión de Chile (2010). Cobertura televisiva del terremoto. La catástrofe vista a través de la pantalla, la audiencia y la industria. Santiago de Chile. (www.cntv.cl/medios/Publicaciones/TerremotoInformeCoberturaTelevisiva.pdf) (09-09-2010).

Espósito, R. (2007). Communitas. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

Mathien, M. (1993). De la raison d'être du journaliste. Communication et Langages, 8 (1); 62-75 (www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/colan_0336-1500_1993_num_98_1) (09-09-2010).

Organización Panamericana de la Salud (2006). Guía práctica de salud mental en situaciones de desastres. Washington: Organización Panamericana de la Salud.

Tétu, J.F. (2004). L’émotion dans les médias: dispositifs,formes et figures. Obtenido de Mots. Les langages du politique (http://mots.revues.org/index2843.html) (09-09-2010).

Zubiri, X. (2004). Inteligencia sentiente. Madrid: Tecnos.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Este trabajo contempla a la vez un propósito conceptual y otro de orden práctico. En lo conceptual se propone un modelo para comprender el funcionamiento de la televisión en escenarios de catástrofe y consecutivamente se sugiere, desde este modelo, un conjunto de derivaciones prácticas destinadas a optimizar la funcionalidad de la televisión en estos escenarios. El modelo propuesto concibe la intervención televisiva con una doble funcionalidad, una de carácter «autocéntrico» focalizada en su reproducción como empresa y otra de carácter «sociocéntrico» orientada a responder a los requerimientos surgidos en el escenario de la crisis. Este modelo será contrastado con los resultados de un estudio del Consejo Nacional de Televisión de Chile que indagó sobre el rol que asumió la televisión en el terremoto acaecido en Chile el año 2010. Según este estudio, si bien se valora el rol informativo y orientador de la televisión, la doble funcionalidad de su intervención fue percibida como problemática, con predominio de la funcionalidad autocéntrica que, desde una lógica de la espectacularidad, buscó construir audiencias, empleando una estrategia basada en la hiperactivación emocional. Finalmente, se concluye con una propuesta para conducir la televisión desde una intervención en la crisis hacia una efectiva intervención en crisis optimizando su funcionalidad sociocéntrica.

1. Introducción

El 27 de febrero de 2010 tuvo lugar en Chile un terremoto y maremoto grado 8,8 en escala Richter –considerado como el quinto más importante en este tipo de evento– el cual dejó cerca de 800 víctimas fatales, 500 mil viviendas destruidas o con daño severo y alrededor de 2 millones de damnificados.

La televisión abierta jugó un rol de primera importancia, pero la forma en que cubrió este evento ha sido objeto de un fuerte debate en la opinión pública. Si bien se destacó su labor en términos de información sobre los hechos ocurridos, sobre las decisiones de las autoridades en los distintos momentos de la tragedia y su apoyo en la búsqueda de personas, ha sido a su vez cuestionada por el supuesto énfasis en los episodios más trágicos y violentos del terremoto.

El debate se vinculó a tres tópicos fundamentales: rol de la televisión ante una catástrofe natural; ética periodística respecto de la cobertura de catástrofes naturales; y efectos de recepción de las transmisiones televisivas en la opinión pública. Atendiendo a estas circunstancias, el Consejo Nacional de Televisión de Chile (en adelante CNTV) realizó un estudio destinado a conocer el rol que asume la televisión en esta catástrofe (Consejo Nacional de Televisión de Chile, 2010).

En este contexto –y a partir de los resultados de este estudio– el propósito de este trabajo es presentar las bases de un modelo que permita por un lado, comprender la intervención de la televisión en escenarios de terremoto, y por otro, derivar elementos para que esta intervención sea más planificada, sistemática y pertinente.

Basados en una concepción dinámica de la realidad (que intenta superar el enfoque más pasivo y estático del análisis de percepciones) en este modelo conceptualizamos el accionar de la televisión como una intervención en los distintos escenarios configurados por el terremoto.

Este componente interventivo de la televisión está ampliamente reconocido desde organismos como la OPS que han elaborado protocolos destinados a regular esta intervención y orientarla a la aminoración del impacto psicológico de la crisis, al respeto de la dignidad y autoestima de las personas y comunidades afectadas, a la promoción de la solidaridad y la cohesión social, entre otros (Organización Panamericana de la Salud, 2006).

La lógica de intervención de la televisión despliega una doble funcionalidad. Por un lado, la funcionalidad que denominaremos autocéntrica, y por otro, la funcionalidad sociocéntrica. Ambas funcionalidades se presentan asociadas en estrecha unidad en la lógica de intervención.

En su funcionalidad autocéntrica la televisión, como empresa, se reproduce a si misma fundamentalmente a través de la construcción de audiencias. En su funcionalidad sociocéntrica, la televisión está respondiendo a los múltiples y urgentes requerimientos planteados por los diferentes escenarios configurados por la crisis.

Desde esta perspectiva, la televisión tiene la capacidad de actuar sobre sus audiencias, constituyéndose en un actor relevante en la configuración de la convulsionada convivencia generada por el terremoto. Esta capacidad de intervención está basada en su poder extensivo e intensivo. La televisión está presente en el 92,4 % de los hogares de los chilenos (Censo, 2002) con un promedio de 2,4 aparatos y un promedio de consumo de 2,5 horas diarias (Consejo Nacional de Televisión de Chile, 2008); de ahí su poder extensivo: omnipresente en el mundo de la vida de las personas interviene sobre las dinámicas propias de la convivencia. Desde su poder intensivo, la televisión actúa sobre las identidades, las emociones, la autoestima, la integración simbólica de las personas.

En su funcionalidad sociocéntrica –que es la que nos interesará prioritariamente en este texto– la televisión puede intervenir por lo menos de dos maneras. En primer lugar, aportando elementos importantes a las personas en la construcción de sus acciones en el campo inmediato y en el tiempo real de la crisis y en segundo lugar, en la configuración de sus modos habituales de reaccionar frente a estas situaciones, lo que resulta de gran importancia para los futuros escenarios de crisis que son bastante frecuentes en Chile.

Desde esta perspectiva «dinámico-accional» nos planteamos las siguientes preguntas: ¿Cómo la intervención televisiva contribuye a la construcción de las acciones «adaptativas» de las personas y al desarrollo de la convivencia en cada uno de los escenarios situacionales generados por la crisis (zona afectada, medianamente afectada, no afectada)? ¿Cómo reacciona la ciudadanía frente a esta intervención? ¿Cuáles fueron los aspectos positivos percibidos en la intervención y cuáles fueron los más cuestionados? ¿Qué intervención se esperaba de la televisión? Los datos y relatos para responder a estas interrogantes y, por tanto, para ir gradualmente construyendo y validando el modelo propuesto, serán tomados de los resultados del mencionado estudio realizado por el CNTV, cuyo diseño describiremos a continuación.

2. Metodología

En un primer momento realizaremos una sistematización de los principales resultados del estudio, para luego profundizar en su interpretación y derivar, desde allí, algunos lineamientos básicos para la elaboración del modelo buscado. El objetivo principal del estudio realizado fue conocer y describir el rol que asumió la televisión en esta catástrofe. Para ello empleó una metodología basada en una doble triangulación. Por un lado, entre técnicas cuantitativas (encuesta telefónica, análisis de contenidos de pantalla) y cualitativas (grupos focales y entrevistas); y por otro, entre fuentes diversas (personas de zonas afectadas, medianamente afectadas y no afectadas por el terremoto; contenidos de la pantalla, informantes clave).

Tabla Metodología del estudio

3. Resultados

Los resultados serán presentados en función de dos categorías, a saber, la forma en que la televisión construyó su intervención y las reacciones de las audiencias.

3.1. La intervención

En la semana inmediatamente posterior al terremoto el 98% de la transmisión –en forma concentrada y continua– fue dedicada a tratar la catástrofe y sus consecuencias. El tiempo restante fue ocupado por películas y series. Basándonos en el análisis de pantalla, en esta sección, nos referiremos al formato más empleado en la cobertura, a los principales temas abordados y a su flujo, a los principales actores participantes y su flujo de aparición, y finalmente a los recursos televisivos que generaron mayor impacto emocional en las audiencias.

El formato más empleado en la transmisión televisiva del 27 de febrero al 5 de marzo fue el «informativo con desarrollo» (76,8%), donde el relato va acompañado de imágenes y el empleo de fuentes activas (reportajes, comentarios, entrevistas, vídeo aficionado y otros), seguido a mucha distancia por la «entrevista» (7,9%). La mayor parte de la transmisión fue con despliegue en terreno, pero el mayor porcentaje de imágenes transmitidas fue en diferido (65,9%); lo que de acuerdo al estudio denota que existió tiempo para decidir sobre la información que se presentó en pantalla. Las notas en diferido se concentraron el 1º de marzo, (recapitulación de las noticias emitidas), y el 3 de marzo (avances de las campañas de ayuda). ¿Cuáles fueron los principales temas tratados?

Gráfico. Principales temas abordados en pantalla

Como se aprecia en el gráfico, de los cinco temas más cubiertos durante la semana del terremoto (casi el 80% del tiempo total de los temas en pantalla), el de mayor frecuencia fue la «constatación de daños materiales y humanos». Para esta dimensión el coeficiente Gini calculado es de 0,62, confirmando una significativa concentración de temas. ¿Cómo evolucionó la presencia de estos temas durante la primera semana?

Gráfico. Evolución de los temas en la pantalla

En el gráfico se observa una disminución pronunciada y sostenida del tema constatación de daños materiales y humanos y un incremento gradual del tema ayuda solidaria. Ambos temas disminuyen hacia el final de la semana.

El tema de ausencia/presencia de servicios básicos se observa con dos puntos altos: durante el 28 de febrero y el 3 de marzo. El primero se refiere principalmente a la ausencia de servicios, mientras que el segundo informa sobre la reposición de servicios como agua potable, supermercados y electricidad. El tema desorden y saqueos obtuvo su punto más alto los primeros días, bajando considerablemente en los días posteriores donde se posicionan temas como evaluación de daños y reposición de servicios. ¿Cuáles fueron los actores que participaron en el tratamiento de estos temas y cuál fue su tiempo de presencia en la pantalla?

Gráfico. Actores más presentes en la cobertura distribuidos durante la semana

Como se observa en el gráfico, las personas naturales y las fuentes del Gobierno central abarcan más de la mitad del tiempo destinado a fuentes de información (52.5%). Esta concentración (coeficiente de Gini 0,65) evidencia una forma de construcción de las notas periodísticas centrada en los testimonios y opiniones de las personas afectadas –las fuentes emocionales– más que en la información experta y de las autoridades de organismos locales.

¿Cómo evolucionó el flujo de la participación de los actores en la pantalla durante la primera semana del terremoto?

Gráfico. Evolución de la presencia de actores en la pantalla

La gráfica muestra un fuerte cambio en la presencia de los actores institucionales (gobierno central, regional y local) en relación con los afectados, como fuente de información. Mientras que los primeros marcan los contenidos de la televisión durante los primeros dos días, los afectados suben su presencia en el transcurso de la semana, logrando su punto más alto el 3 de marzo. En varias ocasiones los equipos de los medios de comunicación llegaron al campo mismo de los hechos antes que las autoridades y los equipos de rescate de la capital, siendo objeto de demandas urgentes de ayuda de parte de las personas afectadas, demandas para las cuales estos equipos, por un lado, no estaban preparados, y por otro, no estaban contempladas en sus tareas. Un aspecto importante de la intervención televisiva está referido al impacto que tuvo sobre la emocionalidad de las audiencias. Según el análisis de pantalla, los recursos empleados por la televisión que generaron mayor impacto emocional fueron los siguientes:

Tabla. Recursos que generan impacto emocional

El uso sistemático de estos recursos denota un énfasis en la construcción dramática de la noticia.

3.2. ¿Cómo reaccionaron las audiencias a la intervención?

Tomando como referencia la encuesta y los grupos focales, en esta sección abordaremos por un lado, los aspectos más críticos de la intervención televisiva, a saber, el impacto emocional sobre los niños(as), el modo de abordar los saqueos, el sensacionalismo1, la lógica invasiva de la privacidad y la falta de información explicativa y, por otro, los aspectos más valorados de la misma. El 56% de las personas vio más televisión que lo habitual. Sólo un 18% declara haber visto menos televisión en los días posteriores al terremoto. Según la encuesta, las imágenes de destrucción y devastación general (40%), devastación costera (39%), sufrimiento de las personas afectadas (8%) y de saqueo (6%) fueron las que más impactaron a las audiencias. En cambio, en la pieza cualitativa del estudio fueron las imágenes de saqueo las que más impresionaron a los entrevistados, independientemente del grupo socioeconómico y la ciudad en la que se habita. ¿Qué reacciones emocionales activaron estas imágenes?

Gráfico: emociones activadas por la televisión

Según el gráfico, las reacciones emocionales activadas se situaron desde la preocupación (90%) hasta la vergüenza (49%), pasando por la motivación para ayudar (86%), la tristeza (86%), la esperanza (79%), el temor (78%), la rabia (68%) y el orgullo(58%). Es en este plano donde se cuestiona más intensamente la intervención televisiva, especialmente cuando se trata de los niños que –según la encuesta– en un 68% de los casos siguieron la cobertura televisiva de la catástrofe.

Según la pieza cualitativa, la población infantil habría experimentado reacciones recurrentes de angustia, inseguridad, pesadillas, miedo a estar solo, reducción del sueño y temor a visitar algunos lugares, como la playa en el caso de Iquique (ciudad costera en zona no afectada del país). Se habría configurado una situación de saturación emocional frente a la cual los padres regularon el consumo de televisión de sus hijos y desplegaron una fuerte crítica a los canales por los fuertes contenidos transmitidos en horarios de todo espectador y la ausencia en la programación de géneros que permitieran la distensión de los niños y de las mismas familias.

Las imágenes de saqueo gatillaron fundamentalmente reacciones de sorpresa y vergüenza. La sorpresa se asoció al carácter imprevisto (no son sólo delincuentes quienes actúan) e incomprensible –desde una perspectiva moral– de estas acciones. La vergüenza quedó asociada a la pérdida de capital simbólico del país, a un quiebre de la autoestima y a una pérdida significativa de la cohesión comunitaria.

La crítica al sensacionalismo –donde predomina la construcción dramática de la noticia por sobre su componente informativo– fue un tema transversal en el discurso de los entrevistados, que estiman que aquí hubo «exageración», «exceso» y «manipulación» destinados a obtener un mayor «rating» en el contexto de competencia entre los distintos canales que cubrieron la catástrofe. La reiteración excesiva de imágenes fuertes y de gran intensidad emocional fue uno de los recursos de la construcción televisiva que tuvo mayor visibilidad para las audiencias (81% de las personas consultadas lo señalan). Esta crítica de las audiencias al «sensacionalismo» se viene repitiendo con una notable regularidad (59%) en la encuesta trianual que realiza el CNTV (Consejo Nacional de Televisión de Chile, 2008).

En el mismo registro, los televidentes experimentan la incómoda sensación de que introducir personajes de la farándula2 en la cobertura televisiva del terremoto implicó por un lado, desmerecer la gravedad de la situación y el sentido trágico de los sucesos, y por otro, atentar contra la dignidad y el respeto de las personas que están viviendo en sus propios cuerpos y pertenencias la dura realidad de la catástrofe. Una vez más, se asocia esta práctica a una búsqueda (inescrupulosa) del «rating».

Otro de los aspectos cuestionados en la intervención televisiva fue la lógica invasiva de la intimidad con el uso reiterado de las fuentes emocionales de la noticia motivada por una búsqueda artificiosa de noticia, sin respeto a los ritmos del entrevistado, a su dignidad y a su derecho a la privacidad

Para los periodistas consultados una debilidad manifiesta en la intervención televisiva fue el predominio de un discurso prioritariamente descriptivo de los hechos en detrimento de la «información explicativa»: el periodismo debe ser didáctico. Desde su perspectiva, esta debilidad es particularmente crítica en un contexto en que las personas tienden a ser «emocionalidad pura» y requieren de elementos que les ayuden a enfrentar la situación con una cierta racionalidad.

¿Qué fue lo más valorado por los televidentes? El aspecto más valorado por las audiencias fue la información entregada que les permitió conformarse una visión muy completa de lo acaecido y –dependiendo de los distintos escenarios y distancias en que se encontraban– elaborar con elementos más concretos las acciones a desplegar en la situación. Las personas consultadas consideran que, en general, la televisión lo hizo bien en su cobertura informativa sobre los aspectos relevantes de la catástrofe, entregando información de utilidad en la situación.

Gráfico. Evaluación del rol informativo de la televisión

Se considera a su vez que la televisión fue más bien eficaz en presentar testimonios de las víctimas (62,7%), en dar esperanza (51,4%) y tranquilizar a las personas (43,7%). La intervención televisiva habría tenido, además, un efecto tranquilizar y esperanzador, cumpliendo, no pocas veces, funciones de compañía y de facilitación de la convivencia.

¿Qué se esperaba de la televisión? Para las audiencias –especialmente aquéllas situadas en el escenario mismo de la crisis– la televisión no respondió adecuadamente a las necesidades más situacionales y urgentes generadas en el escenario de la catástrofe. De hecho, se reclamaba de la televisión un rol propio de un servicio de utilidad pública: apoyo personalizado, ayuda instrumental, orientaciones prácticas. Su intervención fue percibida más informativa que orientadora, más universalista que local, más distante que cercana y obedeciendo, en muchas ocasiones, a otros intereses prioritarios que los de la ciudadanía, a diferencia de las radios que prestaron servicios de utilidad práctica efectiva, constituyéndose en un medio mucho más situacional y cercano a las dinámicas locales, de fácil acceso a las demandas inmediatas de las personas y comunidades afectadas. Finalmente, se asigna a la televisión un rol relevante en la reconstrucción (según el 95% de los entrevistados) que involucra entre otras actividades «fiscalizar el cumplimiento de los programas de reconstrucción» (40%), «organizar, apoyar o difundir campañas de ayuda» (29%) y «mostrar logros y avances de la reconstrucción» (24%).

4. Discusión

La tesis principal del modelo propuesto concibe el rol de la televisión como una intervención que, yendo más allá de lo meramente informativo, tiene un impacto real sobre las personas. La televisión interviene, por decirlo así, «campalmente» en el escenario de la catástrofe; si bien actúa individualmente sobre las personas, interviene en lo que tienen en común, en su convivencia, en su entramado accional, en su emocionalidad compartida, en sus estructuras de apoyo, en su capital simbólico, en la comprensión colectiva de la situación, en sus sentimientos de pertenencia y sentido psicológico de comunidad.

La televisión interviene campalmente desde una doble funcionalidad, una de orden autocéntrico y otra de orden sociocéntrico. Ambas funcionalidades constituyen momentos indisociables de un mismo proceso interventivo. Ahora bien, esta doble funcionalidad es percibida como problemática por los actores consultados en el estudio. Allí donde la televisión –en una lógica autocéntrica– antepone sus propios fines relacionados con la construcción de audiencias, su intervención genera problemas para los televidentes. Pero allí donde ella –en una lógica sociocéntrica– orienta prioritariamente su intervención en función de las necesidades vitales y urgentes de las personas y comunidades afectadas, su presencia se torna imprescindible para la configuración de las acciones adaptativas y la gestión de la convivencia en ese escenario.

Desde el lenguaje de Zubiri (2004: 197-207) postulamos que la televisión propone a sus televidentes un campo perceptivo de la catástrofe organizado principalmente a partir de la «lógica de la espectacularidad», desde la que configura su horizonte, los primeros planos, el trasfondo y su periferia. El terremoto generó un escenario espectacular, con edificios que se desplomaban, el mar invadiendo las ciudades costeras, barcos transportados a la plaza central de los pueblos, víctimas fatales, personas en estado de profundo sufrimiento y activación emocional. Esta espectacularidad –asociada a una trama de alta incertidumbre– constituyó una ocasión imperdible para la televisión: tenía ante sí un «reality real» de costo cero que, de hecho, supo aprovechar eficazmente.

Dentro de este contexto, uno de los sucesos más «espectaculares» fueron los saqueos. Lo espectacular aquí es la pérdida de comunidad, el desplome de la cohesión social, la ruptura abrupta del curso habitual de la vida, que como todo aquello que bloquea la norma moviliza intensamente los afectos (Tétu, 2004: 16). Esta estrategia televisiva habría tenido como efecto fomentar la desconfianza comunitaria, confinando aún más comunidades que ya estaban cerradas, dándole una clausura agresiva, violenta y amenazante. Paradójicamente, la televisión habría producido cohesión social en sus audiencias, precisamente, en torno a la falla en la cohesión social comunitaria durante el terremoto, explotando aquí –desde una visión muy hobbesiana– el fantasma de la pérdida de comunidad, del hombre lanzado contra el hombre y los supermercados, del terror arcano del hombre a la inseguridad y el desorden, del hombre como lobo del hombre (Homo homini lupus) (Espósito, 2007: 55-58).

En la cobertura de estos sucesos «espectaculares» el periodista tiende muchas veces a confundirse con el animador, y las audiencias no logran diferenciar lo que es solidaridad colectiva de la promoción de la imagen de marca del medio. En esta puesta espectacular del mundo –en que el terremoto se confunde con la puesta en escena, el periodista con el animador y la información con la entretención– el televidente pasa a ser un mero espectador y la información un puro espectáculo (Mathien, 1993).

Los televidentes identifican con mucha claridad la estrategia de movilización emocional utilizada por la televisión para sus fines de construcción de audiencias. Esta movilización –fundamentalmente de tonalidad negativa– operó sobre una superficie psicoemocional ya hiperactivada por los sucesos reales del terremoto generando así riesgo de saturación emocional, especialmente en la población infantil.

La transmisión en directo desde el lugar y en tiempo real –modalidad preferida de la televisión para mostrar eventos catastróficos– contribuyó en gran medida a esta hiperactivación. Esta modalidad de transmisión ha sido en general muy criticada, entre otras cosas, porque ofrece una distancia mínima en relación al suceso transmitido. Es precisamente esta característica que hace de la transmisión en directo un campo propicio para la movilización emocional intensa, puesto que deja un gran espacio a lo imprevisto, presentando la realidad del suceso abierta a múltiples y dramáticos desenlaces que van a resolverse en tiempo real a la vista de los televidentes. Según Tétu, esta modalidad de presentación de un suceso transfiere al televidente la tarea y la responsabilidad de interpretar la acción que se está desarrollando frente a sus ojos (Tétu, 2004). Desde la perspectiva de Mathein, «en una lógica de explotación mediática de sucesos reales, el escenario de los directos en el lugar mismo de una catástrofe no difiere prácticamente en nada en su forma de la transmisión de un espectáculo» (Mathien, 1993: 67).

Pero, a su vez, el fuerte impacto generado por las imágenes de destrucción y desolación –unidos a la imposibilidad para el televidente de actuar inmediatamente en el espacio mismo de la catástrofe y a la emoción insoportable de quedar impasible frente al dolor ajeno– activan gestos solidarios de todo tipo en los telespectadores, contribuyendo así a la instalación de múltiples dispositivos de ayuda (Tétu, 2004:13).

El estudio perfila un televidente crítico y proactivo, con capacidad para visibilizar la lógica de la intervención televisiva, anticipando y reconociendo los objetivos perseguidos por ella, y que, en sus campos propios de acción y control, generan prácticas de autorregulación, destinadas a la protección de la salud mental de sus hijos, previniendo así la emergencia de emociones de intensa carga negativa. Se configura así un modo de enfrentamiento de relativa autonomía frente a la intervención televisiva, lo que puede ser muy relevante para una política de educación de medios en este ámbito.

La televisión interviene, pero su intervención no es planificada. Los resultados de este estudio permiten derivar algunos elementos operativos para el diseño de una intervención planificada, sistemática y pertinente de la televisión en este tipo de catástrofe. Durante la catástrofe, la televisión debiera mantener como eje dominante de su intervención la funcionalidad sociocéntrica a la que, por tanto, quedaría supeditada la funcionalidad autocéntrica.

En un plano más operativo debiera integrarse a un plan local y nacional de intervención en crisis que coordine y articule instituciones, organizaciones sociales y comunidades en torno a las siguientes líneas generales:

- Respeto a la dignidad y derechos de las personas afectadas.

- Apoyo constructivo al desarrollo de acciones adaptativas: un aspecto central de la intervención hecha por la televisión es mantener a la población informada acerca de lo ocurrido (constatando los daños materiales y humanos producidos) y de la evolución de los hechos. Esto posibilita a las personas tomar las mejores decisiones posibles en la elaboración de sus acciones.

- Muy asociado a lo anterior la televisión debe contribuir a la contención emocional de las personas afectadas y al desarrollo de sentimientos de seguridad, autoconfianza y tranquilidad que aminoren el impacto psicológico de la crisis, posibilitando a las personas actuar desde un capital emocional más sólido. Todo ello implica evitar el funcionamiento según la lógica de la espectacularidad, el deslizamiento hacia el sensacionalismo, la hiperactivación emocional y el uso sistemático de las fuentes emocionales de la noticia.

- La televisión debe contribuir en todo momento a una adecuada (re)articulación institucional-comunitaria en el escenario de la crisis, evitando las tensiones innecesarias y fortaleciendo la confianza de la comunidad en las instituciones y organismos que prestan apoyo.

- La intervención debe estimular y fortalecer el soporte comunitario como fuente de seguridad, apoyo, estabilidad y pertenencia para las personas, contribuyendo así al fortalecimiento del sentido psicológico de comunidad.

- La televisión debe jugar un rol crucial en la reconstitución del capital simbólico nacional y en la recuperación de la cohesión social.

- Debiera cumplir a su vez funciones propias de un canal de servicio público facilitando las campañas de ayuda y de búsqueda de personas, la información sobre el funcionamiento de los servicios básicos y la entrega de información especializada, a cargo de expertos para una mejor comprensión del fenómeno.

- Todo lo anterior implica incluir en la formación y preparación de profesionales de la comunicación contenidos relativos a la educación de medios, modelos de intervención en crisis y trabajo en red con organismos institucionales y comunitarios.

- La idea clave es que la televisión pase de una intervención en la crisis con dominancia de la funcionalidad autocéntrica –que puede conllevar los riesgos analizados en este trabajo– a una efectiva intervención en crisis con dominancia de la funcionalidad sociocéntrica que ponga al servicio de la comunidad todo su potencial constructivo.

Notas

1 Tendencia de los medios de comunicación a la exacerbación o abuso de la emoción con el objetivo de impactar a la audiencia.

2 Se denomina «farándula» a los programas con o sobre los «famosos».

Referencias

Consejo Nacional de Televisión de Chile (2008). VI Encuesta Nacional de Televisión (www.cntv.cl). (www.cntv.cl/medios/Publicaciones/2009/VI_Encuesta_Nacional_TV.pdf) (09-09-2010).

Consejo Nacional de Televisión de Chile (2010). Cobertura televisiva del terremoto. La catástrofe vista a través de la pantalla, la audiencia y la industria. Santiago de Chile. (www.cntv.cl/medios/Publicaciones/TerremotoInformeCoberturaTelevisiva.pdf) (09-09-2010).

Espósito, R. (2007). Communitas. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

Mathien, M. (1993). De la raison d'être du journaliste. Communication et Langages, 8 (1); 62-75 (www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/colan_0336-1500_1993_num_98_1) (09-09-2010).

Organización Panamericana de la Salud (2006). Guía práctica de salud mental en situaciones de desastres. Washington: Organización Panamericana de la Salud.

Tétu, J.F. (2004). L’émotion dans les médias: dispositifs,formes et figures. Obtenido de Mots. Les langages du politique (http://mots.revues.org/index2843.html) (09-09-2010).

Zubiri, X. (2004). Inteligencia sentiente. Madrid: Tecnos.

Document information

Published on 28/02/11

Accepted on 28/02/11

Submitted on 28/02/11

Volume 19, Issue 1, 2011

DOI: 10.3916/C36-2011-02-07

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?