Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Modern technology offers many facilities, but elderly people are often unable to enjoy them fully because they feel discouraged or intimidated by modern devices, and hus become progressively isolated in a society where Internet communication and ICT knowledge are essential. In this paper we present a study performed during the Nacodeal Project, which aims to offer a technological solution that may improve elderly people's every day autonomy and life quality through the integration of ICTs. In order to achieve this goal, state-of-art Augmented Reality technology was developed along with carefully designed Internet services and interfaces for mobile devices. Such technology only requires the infrastructure which already exists in most residences and health-care centres. We present the design of a prototypical system consisting of a tablet and a wearable AR system, and the evaluation of its impact on the social interaction of its users as well its acceptance and usability. This evaluation was performed, through focus groups and individual pilot tests, on 48 participants that included elderly people, caregivers and experts. Their feedback leads us to the conclusion that there are significant benefits to be gained and much interest among the elderly in assistive AR-based ICTs, particularly in relation to the communication and autonomy that they may provide.

1. Introduction

Today, everybody agrees that we live in a society which is constantly evolving and which has become increasingly dependent on the use of new technologies to fuel this change. Such constant changes affect the members of society since there is an implied cost of adapting to all new habits and practices (time, effort etc.). In many ways, both the growing pace and the amplitude of this change has led to a widening of the gap between members of society who adapt and those who have difficulties adapting. Citizens aged 65 or over the elderly suffer from the added limitations that come with the aging process. Moreover, the stereotypical view relating age to resistance to change and inability to learn new approaches is detrimental to their integration and living quality in an increasingly digital society. This poses a serious social problem, pronounced by a marketing tendency towards a young audience or a focus on users with technical expertise (Prensky, 2001), and is further aggravated by the increased degree of social isolation that comes with age.

According to the Eurostat report of 2014 (European Commision, 2014), the number of elderly citizens in the European Union already constitutes 18.2% of the population, and is expected to increase to 31.3% within 20 years. Italy, in particular, is the European country most affected by these issues: approximately 250,000 Italians are affected by Alzheimer´s disease and a comparable amount with dementia (Chiatti, 2013), underlining the need for continuous assistance by carers and ICT devices.

Contrary to some common beliefs, elderly people are aware of the importance and benefits of ICTs, regardless of gender or degree of studies, as evidenced by studies by Agudo, Fombona and Pascual (2013: 131142). It was observed that ICTs are mostly used for social and entertainment purposes such as contacting friends and family members, or creatingmedia content (Agudo, Fombona & Pascual, 2012). Moreover, elders show a good acceptance of multimedia applications such as videoconference/calls and online video to complement their daily activities.

A novel form of delivery of media content and interaction towards assistive technologies is Augmented Reality (AR).This approach consists of the superimposition of some animation or image in a realistic way, over an image captured by a digital camera. This technology has been recognized by educational researchers as a powerful interactive tool (Wu, Lee, Chang & Liang, 2013) for tasks such as visualization of complex structures (Arvanitis & al., 2009), educational games (Rosenbaum, Klopfer & Perry, 2007), and designbased learning (Bower, Howe, McCredie, Robinson & Grover, 2014), resulting in increased student motivation. Usually, this content is delivered through computers, tablets or mobile phones, and such functionality has been incorporated into some assisted living systems (Avilés, Villanueva, GarciaMacias & Palafox, 2009). Still, the acceptance of such technology, as pointed out by HernándezEncuentra, Pousada and GómezZuñiga (2009: 226245), is not a mere matter of usability or design: the technology shouldn’t only be a tool to replace what had been lost, but rather a tool for personal development.

One important observation of their work is: «It can be concluded that the adaptation of ICTs to elderly users is necessary, but that in itself does not mean that they will use the technology. The device must be customized, modulated and scaled specifically for an older population in which the interindividual variability is increasing». This flexibility towards the individual necessities of the elderly is an essential part of the design of new technologies.

Computers and tablets require constant interaction and manipulation, which can make them unsuitable as a medium of content delivery for the elderly (Kurz, Fedosov & al., 2014; Almeida, Orduña, Castillejo, LópezdeIpiña & Sacristán, 2011; LópezdeIpiña, Klein & PerezVelasco, 2013). The Sixty Sense project (Mistry & Maes, 2009) showed that realistic visual cues can be added into a user’s surroundings by using AR together with a portable camera and a pico projector, and this can provide a promising approximation towards interaction with the user. Progress in AR and Simultaneous Localisation and Mapping (SLAM) methods (Henry, Krainin, Herbst, Ren & Fox, 2012; Engel, Schöps & Cremers, 2014) has removed the need for the introduction of AR markers and the adaptation of the environment for their usage.

The rationale behind the Nacodeal (Natural Communication Device for Assisted Living) project is the development of a new type of Assisted Living system for elderly people with an aim to increasing their social integration through ICTs. A guidance and communication service is provided by using two devices. The first is a tablet incorporating software developed for the end user’s needs and requirements, customizable and accessible to different user categories. The second is a new kind of Augmented Reality technology (Saracchini & Ortega, 2014): a wearable device with an embedded pico projector and camera which locate the user position and orientation by using a 3D map of the environment, projecting information realistically (figure 1).

Using this technology, it is possible to create friendly guides so that its users will be capable of performing their daily activities and accessing online services which are relevant to them. In order to satisfy these conditions, the following requirements were established:

• The system has to determine the user location and the AR device orientation in realtime, exhibiting content autonomously.

• It must be viable for healthcare centres or residences without relying on a complex infrastructure or expensive equipment.

• The end user should interact with the system through a mobile interface (tablet), tailored to his/her cognitive levels.

• It must act as a bridging tool between ICTs, the end user and his/her family, and caregivers without changing the user’s routine or reducing mobility.

• It should produce minimal changes in the environment, and not require elements such as AR markers.

These requirements should not be attained by WiFi or RFID triangulation, since they do not provide precise positioning and orientation of a portable device, and also tend to require a complex and expensive infrastructure.

• Visual SLAM/AR approaches can fulfil these requirements using offtheshelf components such as Webcams and computers.

In order to assess the efficacy of the proposed system, a study was made with elderly volunteers, caregivers and specialists from Italian healthcare centres, aiming to determine the benefits in their social interactions, as well any desirable characteristics regarding content, functionality and usability. The next section will offer an overview of the Assisted Living system and details of the validation process.

2. Design and validation methodology

2.1. The assisted living system

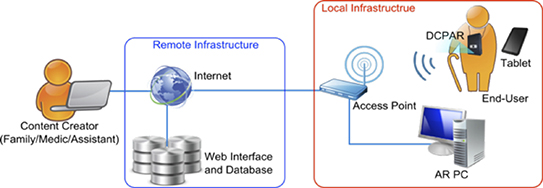

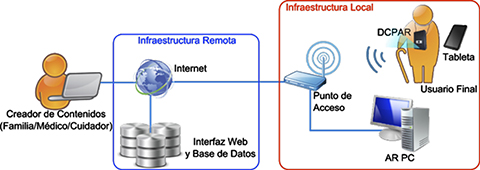

The assisted living system was designed to use a resource available in most residences and public spaces: a wireless Internet access point. Its components are separated in two main groups: the remote infrastructure, a Webbased service that manages the content to be exhibited by the system and the local infrastructure, which is the hardware installed in the healthcare centre or residence, and the interfacing devices which interact with the enduser (figure 2).

The system has been designed taking into account two main factors: the content creator and the end user. The content creator is responsible for creating and programming the multimedia content to be displayed by the assisted living system. This person (or group of people) can be a caregiver, doctor, relative or behavioural specialist, interacting with the system through a Webinterface accessible through a computer or smartphone. The end user is the elderly person, to whom this content will be delivered through the tablet and the wearable AR device, denominated DCPAR (Device with Pico Projector for Augmented Reality) (figure 3).

A core concept of this design is that neither actor requires more than the knowledge necessary to use common house appliances. The content creator needs to know how to navigate a standard Webpage, create or edit digital pictures, presentations and movies, or at least submit already created content. The end user is required to have only basic knowledge of how to use the tablet features and no technical knowledge in order to receive AR content. Due to the wireless capabilities of the devices, the end user is not obligated to stay in a single place as he/she would if using a personal computer. This enables him/her to conduct his/her daily routine with as little interference as possible.

• Webinterface and Database. The main purpose of the WebInterface is to enable authorized content creators to upload media content and determine where and in what context AR content should be displayed. This data will be stored in a remote database, which will be accessed by the components of the local infrastructure. Some potential services to be delivered are personal agendas and calendar, messaging, VoIP calls and online chats, newspapers, magazines, memory exercises and information about personal therapy, educational videos about subjects of interest (culinary, handcraft work, etc.), maps with advice about potential hazards, and content produced by relatives such as videos, pictures or music.

The content creators can personalise the services according to the user’s needs and habits. Furthermore, each area, with the related services offered, has been designed based on user requirements collected thanks to a specific analysis of the contents (DeBeni, 2009; DeBeni & Carretti, 2010).

• AR PC. The Augmented Reality PC is a dedicated computer connected to a wireless access point. It acts as the system processing centre, not limited by the weight, energy consumption or ergonomic constraints of typical mobile devices. The AR PC automatically distributes video and audio content to be transmitted to the tablet and the DCPAR devices in realtime, monitoring the database at determined intervals in order to retrieve changes in programmed schedules. It is also responsible for the execution of algorithms for Augmented Reality, environment recognition and determination of DCPAR orientation by processing the data transmitted by its camera. Other services, such as facial recognition or behaviour analysis, can be added through software updates, avoiding hardware replacement. This component is designed to be highly automated, and initializes the entire content exhibition just after being turned on like a common house appliance. In environments with multiple endusers, such as a healthcare centre, the system is managed by an operator such as a nurse or gerontologist.

• Tablet. This is a consumer tablet containing intuitive software with an orientation support system constructed according to the criteria of ROT (Reality Orientation Therapy), aimed at supporting people with cognitive problems. This therapy allows stimulating the users throughout the day, through continuous information relating to their personal data, space and time. It facilitates the construction of coherent cognitive representations, allowing better understanding of the context that surrounds the user and the role that he/she has. The software interface aims to simplify the user’s navigation inside the services and applications and to continuously stimulate their memory. The tablet holds four main applications: Calendar, Talk, Games and Entertainment. Each field represents a dedicated service, promoting the elderly person’s brain activity during its use and helping him/her to remember appointments and daily activities.

• DCPAR. The DCPAR prototype is a wearable device containing an embedded camera, a pico projector and a wireless transmitter housed in a 10x14x3 cm casing with straps which go round the neck. Although it is specialized hardware, low cost components have been used in order to achieve affordability. The device acts as an inputoutput video stream device, transmitting the environment visualised by the camera, which is processed by the AR PC, thus allowing the generation of an image. This allows the automatic exhibition of media advice associated with each given location. For instance, when the user approaches a stove, it projects a warning about the potential hazard. More interactive content can be programmed, for example a guiding arrow adjusted in real time, dependingon user location.

• Installation. The wireless access point and AR PC use the network available at the place of installation and are positioned where there is good wireless coverage. To ensure that the Augmented Reality, recognition and localization algorithms function properly, a 3D map of the environment has to be prepared in advance. This step is done using a specialized software (Saracchini & Ortega, 2014) run through a laptop connected with a depth sensor such as the Microsoft Kinect, which scans places of interest. A 3D map is then generated and stored in the database, where the content creator can configure the AR programming according the user needs. The scanning procedure takes no longer than one or two hours, depending on the size of the scanned area. Once completed, the Assisted Living system is ready to use. Significant changes in the environment, such as if the walls are repainted, or if furniture is moved or replaced may require rescanning, since the localization system is based on visual cues.

2.2. Validation with users

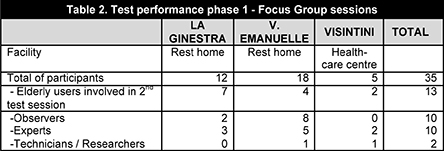

In order to effectively assess the proposed design, it is necessary to analyse its usage with elderly users, determining points of failure and inadequacies to their necessities in order to establish any concrete benefits brought to their routine. One of the key contributions to be analysed is the reduction of social isolation, and the improvement in socialisation, integration and interaction with elders affected by temporary memory loss. Taking this factor in consideration, our tests had been carried out in group sessions and individual pilots in rest homes and healthcare centres located in the province of Ancona, Italy. The user validation phase of the system has been structured in 2 steps: a focus group that involved elderly users, caregivers and experts (test performance phase 1) and individual pilot sessions in real scenarios (test performance phase 2).

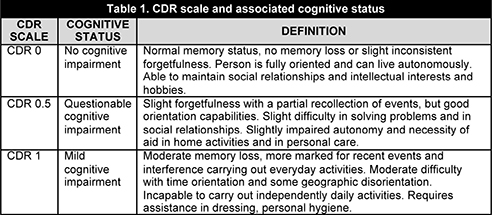

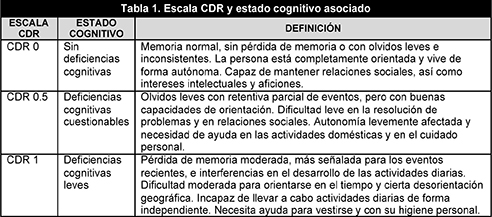

The first part of the test –the group session– was aimed at comprehending the point of view of elderly people concerning the two components of the Assisted Living system, using one focus group for each facility in order to support the subjects approximation to this new technology and make it easier for them to understand the services and applications installed. The functions and features of the devices were explained during the sessions, and some initial feedback was retrieved. A group of experts was invited to evaluate the devices and interaction with the elderly users. As a nonmedical preventive tool, the system does not target patients who suffer from serious cognitive trouble, and the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale (Herndon, 2006) was used as reference base during the selection process of participants. The tests targeted people from the scale CDR 0 to CDR 1 (table 1).

In the focus groups, the experts evaluated how the devices influenced social interaction and how each individual application of the device was able to offer autonomy, wellbeing and happiness. They also performed an assessment of which kind of application was preferred by the end users, and to what extent the use of social media produced new interest in the elderly. Other aspects such as the usability of the tablet and desired functionalities for the DCPAR were also evaluated.

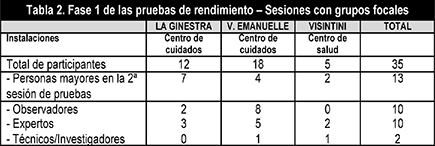

The first focus group was in Chiaravalle, in the La Ginestra rest home, with a total of 12 participants among elderly, caregivers and experts. Seven volunteers participated as pilots, and two as observers. The expert team was composed of the coordinator of the residence, an expert in Alzheimer’s disease and an operator responsible for recreational activities.

The second focus group was in Jesi, at the Victor Emanuele II residence. This group was composed of a greater number of participants, although most of them were simple observers (4 pilots and 8 observers). The devices and their usage were evaluated by the rest home coordinator, a member of Alzheimer Marche Association, a socialhealth operator, 2 operators responsible for recreational activities and a relative of one of the elders.

The third focus group was situated at Falconara Marittima in the Visintini residence, dedicated to patients suffering from Alzheimer’s and senile dementia problems. This focus group was intended to evaluate the interaction of elders with more severe cognition issues, and was significant smaller than the others. The focus group was supported by the daily centre coordinator; a psychologist specialized in cognitive impairments and one volunteer from the centre.

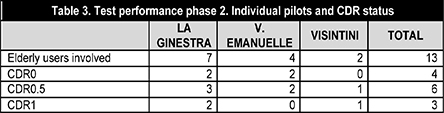

The second session involved13 pilots: 10 women and 3 men with an average age of 80.3 years. Their physical and cognitive profile was also varied: six of them used wheelchairs due physical pain or infirmity, two had mild cognitive issues (CDR 0.5 and 1), and five had good physical and mental conditions. All participants resided on the tested facilities, except 3 of them: one resides in his own home and 2 others spend the day in the daily centre but return to a relative’s home at night (tables 2 and 3).

3. Results

3.1. Enduser feedback

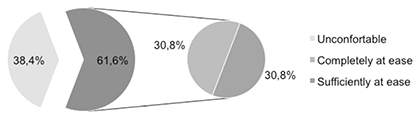

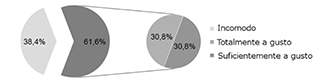

Of the elderly users involved in the individual pilots, 30.8% felt completely at ease during the tests and 30.8% sufficiently at ease, thus providing 61.6% positive feedback. The remainder of the population (38.4%) felt uncomfortable, although no one rejected the devices completely. This reaction was considered quite normal with this kind of target due their unfamiliarity and certain degree of resistance towards their usage. See graph 1.

The feedback collected after the testing with the tablet was mostly positive and almost all of the elderly interviewed felt an initial embarrassment and insecurity followed by a feeling of curiosity and excitement. The elderly considered the tablet «a good tool to stay in contact with family and friends» with «easy access» and the ability to promote their «wellbeing and the sense of not feeling alone…». Many of them, after an initial resistance and fear toward the «new», learned to handle the tablet and DCPAR with familiarity. After understanding their functionality, they demonstrated enthusiasm and the will to learn much more about their functions. This progressive involvement was followed by a positive collaboration, but it also produced two critical issues: the problem of dependence on the devices and the management of the negative reactions and disappointment by the elderly at the end of the tests. The experts confirmed that the issue of «addiction» is typical in this kind of target, who are often lonely with few possibilities of social interaction or who live a monotonous life with low cognitive stimulation. Every form of involvement that enhances their memories is appreciated.

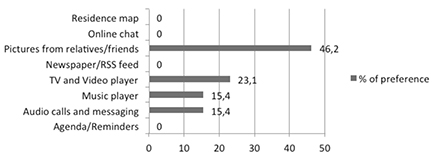

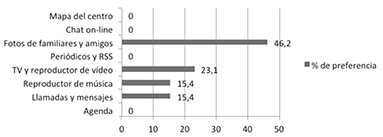

• Tablet. From the result of the survey, the elders evaluated their favourite service as the photo library (46.2%), followed by TV and video streaming (23.1%). A similar percentage (15.4%) was obtained for video calling and messaging functions and audio player. The participants showed little interest in the other applications. Their focus was in fact, directed on the content related to their relatives and friends. The agenda, especially, was considered too difficult to use by the participants with cognitive issues.

The participants desired to improve the photo album and music applications, especially regarding the audio volume (hearing impairment) and image size (eyesight problems). They also manifested a wish for more multimedia content from their time, as well a more intuitive interface. See graph 2.

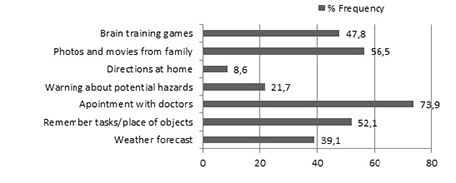

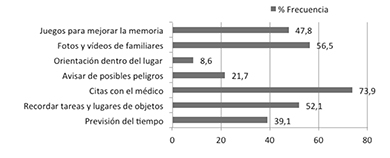

• DCPAR. In general, they felt the DCPAR bulky and heavy, sometimes having difficulties to understand its usage properly. However, most of them managed to use the tablet and AR functionalities with a high degree of autonomy. Regarding the device’s functionality, the users were very pleased with its capacity to project images and movies from relatives or subjects of interest such as sport or religion. The device responsiveness was deemed suitable, adapting the projected image to the geometry of the environment properly. The most desired functionalities of the DCPAR were the active visualisation of content produced by their relatives and its use as agenda device, contrasting with the difficulties present in the tablet (graph 3).

A significant issue appeared regarding the device ergonomics: due the user’s posture and pico projector inclination, the image projection was inferior to that expected. Also, it was deemed uncomfortable since it is worn around the neck, potentially increasing issues caused by arthrosis, common in people of advanced age.

3.2. Carer feedback

The carers considered the Assisted Living system a useful tool, but overly complicated for independent use by an elderly person, especially if the user has cognitive or physical problems. This was reinforced by the testers and their families, whom suggested improvements in some details of the graphic interface, such as the «keyboard size» and a full involvement of the caregivers, «who must play a central role during the elderly people’s introduction to and training with the new technology». They also suggested adding exercises to promote the association between places and images, in order to stimulate the spatial perception within the environments –facility or private home– and introduce the possibility to make video calls with relatives and friends.

According to the carers, the use of the proposed system may change based on the environment where it is used. In an elderly person’s home it is useful for the memorization of appointments and events, as an alarm system for domestic dangers and obstacles, as a reminder to take medicines properly, as a phone system to communicate with their own social network, and as a stimulus to increase short term memory and personal interests. In a nursing home the system can improve the relationships among users as an entertainment device, it can help users remember their daily activities, and it can make it easier to identify objects present in the space through the association of the name made visible by the AR projections.

They observed how the DCPAR images were appreciated by the users wearing it and by the surrounding elders. It was also considered a stimulating tool for the mobility of the elderly. The testers felt compelled to investigate more, walking a lot during the pilots. As weak points, they identified its unsuitability for people with physical problems (e.g. elderly using wheelchairs) due to the viewing angle, and the difficulty of carrying it around for prolonged times. Furthermore they suggested the support of carers or family members in managing user appointments and user personal profiles on the online database.

Finally the carers believed that the best way to encourage seniors in the use of the ICT devices was through an initial gradual approach process with the constant support of a «trainer» (e.g. a carer or relative). The approach that new technology needs involves people who have close contact with the users, since the users are much more collaborative with them than with strangers. Another interesting method to introduce seniors to the system could be through a more entertaining approach such as using educational games.

The experts who participated in the system validation consider the elderly people’s involvement starting from the first phases to be fundamental in order to avoid their isolation tendency. It could also be an excellent tool for elderly with dementia diseases to support traditional nonpharmacological therapy, although in this case the users would need support from an operator.

4. Conclusions

The userneed analysis and the grade of acceptance of the proposed technology solution has highlighted how important it is for the elderly to stay constantly in contact with other people in order to positively stimulate their cognitive functions and prevent social isolation. The relational component has been carefully considered during the validation phase of the prototype in order to understand the real value of the tested technology and its ability to effectively influence the market.

The results showed that most of the elders want to be involved in the digital process, but with specific attention to their previous knowledge and experience that means a deep respect of their learning times. Most difficulties that arose were related to interface design and usability due to their specific cognitive requirements, and not to the level of interest or understanding of the elders regarding the ICT involved. This reinforces the notion that «these generations of the elderly need and want to learn, and see this moment in their lives as the right time to approach ICT (Agudo & al., 2012).

Augmented Reality plays an important role in the Assisted Living system, as it offers automatic context detection and the realistic introduction of information into the environment. In contrast to the tablet, the system is capable of interacting with users autonomously, adopting the role of «personal assistant», helping them achieve goals instead of deviating them from their usual routine. This improves their potential mobility, and the information provided for the elderly that suffer from temporary memory loss becomes an added –or «augmented»– value that is expressed through the most accessible channel to this target group: the association between experience and images. The matching between images and written/audio messages, according to experts in cognitive neuropsychology, promotes and stimulates the brain’s activities and helps older people to maintain their memory in good health for as long as possible (Essay UK, 2006; Mazzucchi, 2008). The analysis made in this study produced valuable information towards designing a suitable AR device for elderly users. As pointed out by the users and experts involved, the prototype was too bulky and cumbersome. The device should incorporate a better ergonomic design and provide a simpler way of projecting an image in the field of view if there is to be continuous use and constant integration into the users’ lives. In order to achieve this goal, further research in miniaturisation and ergonomics of portable computing devices should be carried out.

Further testing is needed on elderly people who live alone. Their necessities and points of view may differ considerably from those who have constant contact with caregivers, and our survey didn’t cover this aspect. Currently, we are performing studies on volunteers under such conditions in order to measure the degree of impact that the proposed system may have on them.

It can be concluded that the proposed technological solution presents an advance towards the introduction of ICTs to the elderly, with potential beneficial impacts on their lives. The tablet and the DCPAR have the potential to promote social interaction and virtually stimulate the cognitive process in the elderly, thus enhancing their selfsufficiency and quality of life. The system avoids being a mere tool to compensate losses or delegate functions, a factor that elderly people identified as being a negative effect of ICTs (HernándezEncuentra & al., 2009). Instead, this technology has the potential to complement the process of personal growth at this stage of life by giving access to educational and entertainment content and by enabling seniors to overcome social isolation effects by keeping in touch with relatives, friends and society. In future research, improvements in this technology will be investigated with the following goals in mind:

• To provide the elderly who live alone the possibility to stay in contact with relatives and friends.

• To promote autonomy among the elderly through assistive and educational content.

• To increase the users’ sense of safety and serenity through the possibility of implementing a call centre that can provide them with quick assistance.

By «augmenting» elderly people, there is increasing expectation that integrated AR technology in mobile devices will make their contact with ICTs and digital facilities a pleasant and natural experience. Progress in visualization and portable technology, such as the recently developed Google Glasses, and smartwatches supports the notion that ICTs have the potential to reach most members of society, regardless of age or gender.

Acknowledgments

The study presented in this paper was funded by the Ambient Assisted Living Joint Programme (AAL), and is part of the NACODEAL Project (ref. AAL20103116).

References

Arvanitis, T., Petrou, A., & al. (2009). Human Factors and Qualitative pedagogical evaluation of a Mobile Augmented Reality System for Science Education Used by Learners with Physical Disabilities. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 13(3), 243-250. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00779-007-0187-7

Avilés, E., Villanueva, I., García-Macías, J., & Palafox, L. (2009). Taking Care of Our Elders Through Augmented Spaces. Proceedings of Latin American Web Congress, 16-21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/LA-WEB.2009.30

Bower, M., Howe, C., McCredie, N., Robinson, A., & Grover, D. (2014). Augmented Reality in Education – Cases, Places and Potentials. Educational Media International, 51(1), 1-15. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2014.889400

Chiatti, C. (2013). The UP-TECH Project, an Intervention to Support Caregivers of Alzheimer’s Disease Patients in Italy: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials, 14(1), 155. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-14-155

Cutler, S.J. (2007). Ageism and Technology. Generations. Journal of the American Society on Aging, 29(3), 67-72.

De-Beni, R. (2009). Psicologia dell’invecchiamento. Bologna: il Mulino.

De-Beni, R., & Carretti, B. (2010). Come migliorare la memoria nell’invecchiamento. Padova (Italy): Psicologia Contemporanea.

Engel, J., Schöps, T., & Cremers, D. (2014). LSD-SLAM: Large-Scale Direct Monocular SLAM. European Conference on Computer Vision-ECCV 2014. (pp. 834-849). Springer International Publishing. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10605-2_54

Essay UK. (2006). The Benefits of Therapies Activies such as Reality Orientation. Essay UK web-page. (http://goo.gl/qTH3kU) (10-09-2014).

European Commision. (2014). Eurostat. Population Structure and Ageing. Eurostat Web-page (http://goo.gl/4gyNuI) (10-09-2014).

Henry, P., Krainin, M., & al. (2012). Rgb-D Mapping: Using Kinect-style Depth Cameras for Denser 3D Modelling of Indoor Environments. The International Journal of Robotics Research, 31(5), 647-663. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0278364911434148

Hernández-Encuentra, E., Pousada, M., & Gómez-Zuñiga, B. (2009). ICT and Older People: Beyond Usability. Educational Gerontology, 35(3), 226-245. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03601270802466934

Herndon, R.M. (2006). Handbook of Neurologic Rating Scales. New York, MA: Demos Medical Publishing.

Kurz, D., Fedosov, A., & al. (2014). [Poster] Towards Mobile Augmented Reality for the Elderly. Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality, 275-276. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ISMAR.2014.6948447

López-de-Ipi-a, D., Klein, B., & Perez-Velasco, J. (2013). Towards Ambient Assisted Cities and Citizens. Proceedings of 27th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications Workshops (WAINA),1343-1348. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/WAINA.2013.203

Mazzucchi, A. (2008). La riabilitazione neuropsicologica. Premesse teoriche e applicazioni cliniche. Masson (Italy): Elsevier.

Mistry, P., & Maes, P. (2009). SixthSense: A Wearable Gestural Interface. In ACM SIGGRAPH (Eds.), Asia Sketches. (p. 11). ACM. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1667146.1667160

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants part 1. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1-6 (http://goo.gl/0jT63R) (07-09-2014).

Rosenbaum, E., Klopfer, E., & Perry, J. (2007). On Location Learning: Authentic Applied Science with Networked Augmented Realities. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 16(1), 31-45. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10956-006-9036-0

Saracchini, R., & Ortega, C.C. (2014). An Easy to Use Mobile Augmented Reality Platform for Assisted Living Using Pico-projectors. (S.I. Publishing, Ed.), Computer Vision and Graphics - Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 8671, 552-561. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-11331-9_66

Wu, H., Lee, S.W., Chang, H., & Liang, J. (2013). Current Status, Opportunities and Challenges of Augmented Reality in Education. Computers & Education, 62(0), 41-49. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.024

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Las posibilidades que ofrecen las tecnologías son muchas, sin embargo, las personas mayores son a menudo incapaces de disfrutar de ellas plenamente, sintiéndose desanimadas o intimidadas por estos nuevos dispositivos. Esto les lleva a un progresivo aislamiento en una sociedad donde es esencial conocer las distintas formas de comunicación a través de Internet y las TIC. En este trabajo presentamos un estudio realizado durante el proyecto Nacodeal, cuyo objetivo es ofrecer una solución tecnológica para proporcionar autonomía y una mejor calidad de vida para las personas mayores durante sus actividades diarias mediante la integración de las TIC. Para lograr este objetivo se ha desarrollado tecnología puntera en realidad aumentada (RA), así como servicios de Internet e interfaces para dispositivos móviles especialmente diseñados para personas mayores. Estas tecnologías emplean la infraestructura presente en la mayoría de casas y centros de cuidados de mayores. Presentamos un prototipo de sistema compuesto por una tableta y un dispositivo de RA portátil, así como el análisis del impacto social en la interacción con usuarios y la valoración de la aceptación y usabilidad. Esta evaluación se llevó a cabo a través de grupos focales y pruebas piloto individuales con 48 participantes: ancianos, cuidadores y expertos. Sus comentarios concluyen que existen fuertes beneficios e intereses por parte de las personas mayores en las TIC asistenciales basadas en RA, especialmente en los aspectos relacionados con la comunicación y autonomía.

1. Introducción

Hoy en día, todo el mundo está de acuerdo en que vivimos en una sociedad que está en constante evolución y que, de forma incremental, se ha vuelto dependiente del uso de las nuevas tecnologías para alimentar dicho cambio. Este constante cambio afecta a los miembros de la sociedad, dado que implica un coste de adaptación a todos estos nuevos hábitos y prácticas (tiempo, esfuerzo, etc.). De muchas formas, tanto el ritmo de crecimiento, como la amplitud de este cambio, han dado lugar a un aumento en la brecha entre los miembros de la sociedad con dificultades para adaptarse. Los ciudadanos de 65 años o más, las personas mayores, sufren debido a las limitaciones añadidas dadas por el proceso del envejecimiento. La visión estereotipada relacionando la edad con la resistencia al cambio y a la incapacidad para aprender nuevas estrategias va en detrimento de su integración y calidad de vida en una creciente sociedad digital. Esto plantea un serio problema social, que se intensifica por la tendencia del marketing a una audiencia joven (Cutler, 2007) o que se enfoca en usuarios con experiencia técnica (Prensky, 2001), y se agrava más por el incremento del aislamiento social que viene dado por la edad.

De acuerdo con el informe de 2014 de Eurostat (European Commision, 2014) el número de personas mayores en la Unión Europea ya constituye el 18,2% de la población actual, y se espera que se incremente al 31,3% en 20 años. Particularmente, Italia es el país europeo más afectado por este asunto: aproximadamente 250.000 italianos están afectados por la enfermedad del Alzheimer y una cantidad comparable con demencia (Chiatti, 2013), lo que remarca la necesidad de asistencia continuada por los cuidadores y por dispositivos TIC con este tipo de pacientes.

En contra de algunas creencias comunes, las personas mayores son conscientes de la importancia y de los beneficios de las TIC, independientemente de su género, o de su nivel de estudios, como lo demuestran los estudios de Agudo, Fombona y Pascual (2013: 131142). Se observó que las TIC se utilizan principalmente con el fin de socializar y como entretenimiento tales como contactar con amigos y miembros de la familia, o para crear contenidos multimedia (Agudo, Pascual & Fombona, 2012). Particularmente, las personas mayores tienen una buena aceptación hacia las aplicaciones multimedia, tales como videoconferencias y vídeos online para complementar sus actividades diarias.

Una forma novedosa de proporcionar contenidos multimedia e interactivos de tecnología asistencial es la realidad aumentada (RA). Esta aproximación consiste en la superposición de animaciones o imágenes de una forma realista, sobre una imagen capturada por una cámara digital. Esta tecnología ha sido reconocida por investigadores educativos como una herramienta interactiva muy potente (Wu, Lee, Chang & Liang, 2013) para tareas como la visualización de estructuras complejas (Arvanitis, Petrou & al., 2009), juegos educacionales (Rosenbaum, Klopfer & Perry, 2007), y aprendizaje basado en el diseño (Bower, Howe, McCredie, Robinson & Grover, 2014), produciendo un incremento en la motivación de los estudiantes. Normalmente, este contenido se proporciona a través de ordenadores, tabletas o teléfonos móviles, y esta funcionalidad fue incorporada en algunos sistemas de asistencia (Avilés, Villanueva, GarcíaMacías & Palafox, 2009). Todavía, la aceptación de estas tecnologías, tal y como indican HernándezEncuentra, Pousada y GómezZuñiga (2009: 226245), no es un simple asunto de usabilidad o diseño: estas no deben ser solo herramientas para reemplazar lo que se ha perdido, más bien deben ser herramientas para el desarrollo personal.

Una importante observación de su trabajo es: «Se llega a la conclusión de que la adaptación de las TIC a las personas mayores puede ser necesaria, pero eso no significa que sea una condición suficiente que asegure que ellos vayan a utilizar la tecnología. El dispositivo tiene que ser personalizable, modular y escalable, especialmente para la población de personas mayores en la cual la variación entre los individuos se incrementa». Por consiguiente, esta flexibilidad hacia las necesidades individuales en las personas mayores es una parte esencial del diseño de las nuevas tecnologías.

Los ordenadores y tabletas requieren de la constante interacción y manipulación, lo cual puede ser inadecuado en lo que se refiere a proporcionar contenido a personas mayores (Kurz, Fedosov & al., 2014; Almeida, Orduña, & al., 2013). El proyecto SixtySense (Mistry & Maes, 2009) muestra que las pistas visuales realistas pueden ser añadidas en el entorno del usuario utilizando RA y un conjunto de cámara y picopoyector portátil, siendo prometedora esta aproximación para interactuar con el usuario. Los avances en RA y en los métodos de mapeado y localización simultánea (SLAM) (Henry, Krainin & al., 2012; Engel, Schöps & Cremers, 2014) eliminan la necesidad de introducir marcadores de RA y de adaptar el entorno para su uso.

La razón de ser del proyecto «Nacodeal» (Natural Communication Device for Assisted Living) es la de desarrollar un nuevo tipo de sistema asistencial para personas mayores, que pretende incrementar la integración social a través de las TIC. Se proporciona un servicio de guiado y comunicación usando dos dispositivos. El primero es una tableta que incorpora un software especialmente desarrollado para las necesidades y requisitos de los usuarios finales, personalizable y accesible para diferentes categorías de usuarios. La segunda es un nuevo tipo de tecnología de realidad aumentada (Saracchini & Ortega, 2014): un dispositivo portátil con picoproyector y cámara incorporada que localiza la posición y orientación del usuario utilizando un mapa 3D del entorno, proyectando información de forma realista (figura 1).

Usando esta tecnología, es posible crear guías amigables, de modo que sus usuarios sean capaces de realizar sus actividades diarias y acceder a servicios en línea que son relevantes para ellos. Para satisfacer estas condiciones se han establecido los siguientes requisitos:

• El sistema tiene que determinar en tiempo real la localización del usuario y la orientación del dispositivo de RA, mostrando contenido de forma autónoma.

• Debe ser viable para centros de cuidado y residencias sin necesitar de complejas infraestructuras ni costosos equipos.

• El usuario interactuará con el sistema a través de un interfaz móvil (tableta), adaptada para su nivel cognitivo.

• Debe ser una herramienta puente entre las TIC, el usuario final y sus familiares y cuidadores sin cambiar su rutina ni reducir su movilidad.

• Debe introducir los menos cambios posibles en el entorno, no requiriendo elementos como marcadores de RA.

Estos requisitos no pueden obtenerse mediante triangulación con wifi o RFID, puesto que estos no proporcionan una posición y orientación precisa a un dispositivo portátil, además la infraestructura requerida en este caso es compleja y costosa para la mayoría de la gente.

• La aproximación de Visual SLAM/RA puede cubrir estos requisitos utilizando componentes como cámaras web y ordenadores.

Para poder evaluar la eficacia del sistema propuesto, se ha realizado un estudio con personas mayores voluntarias, cuidadores y especialistas de centros de cuidado de Italia, con el objetivo de determinar los beneficios en las interacciones sociales, así como las características deseables en cuanto a contenido, funcionalidad y usabilidad. La siguiente sección ofrecerá una visión general del sistema de asistencia y de sus detalles en el proceso de validación.

2. Diseño y metodología de validación

2.1. El sistema de asistencia

El sistema de asistencia se diseñó de forma que utilice los recursos disponibles en la mayoría de hogares y espacios públicos: un punto de acceso a Internet inalámbrico. Sus componentes se separan en dos grupos principales: la infraestructura remota, que es un servicio basado en web que gestiona el contenido que muestra el sistema, y la infraestructura local, que es el equipamiento instalado en el centro de salud o en el hogar, junto con los dispositivos de interfaz que interactúan con el usuario final (figura 2).

El diseño del sistema tiene en consideración a dos actores principales: el creador de contenidos y el usuario final. El creador de contenidos es responsable de la creación y programación del contenido multimedia que debe ser mostrado por el sistema de asistencia. Esta persona (o grupo de personas) puede ser un cuidador, médico, familiar o especialista en comportamiento, e interactúa con el sistema mediante una interfaz web accesible a través de un ordenador o teléfono inteligente. El usuario final es la persona mayor, a la que se le proporciona el contenido a través de la tableta y del dispositivo portátil de RA, denominado DCPAR (dispositivo con picoproyector para realidad aumentada) (figura 3).

Un concepto clave de este diseño es que ninguno de los dos actores necesita más conocimientos que los que requiere el uso de otros aparatos comúnmente presentes en el hogar. El creador de contenido debe saber cómo navegar en una página web normal, cómo crear o editar fotografías digitales, presentaciones y películas, o al menos, cómo reproducir contenido ya existente. El usuario final sólo necesita tener conocimientos básicos sobre cómo utilizar las características de una tableta y no se le exigen conocimientos técnicos para ser capaz de recibir contenido mediante RA. Además, debido a las capacidades inalámbricas de los dispositivos, el usuario no debe permanecer en un lugar fijo como requeriría un ordenador de sobremesa. Esto le permite llevar a cabo su rutina diaria con una mínima interferencia.

• Interfaz web y base de datos. El objetivo principal de la interfaz web es facilitar a los creadores de contenidos autorizados la inclusión de contenido multimedia, así como determinar dónde y bajo qué condiciones debería mostrarse contenido de RA. Esta información se guardará en una base de datos remota, a la que accederán los componentes de la infraestructura local. Algunos posibles servicios que se pueden ofrecer son: agenda personal y calendario; mensajería, llamadas de voz sobre IP y conversaciones en línea; prensa y revistas; ejercicios de memoria e información sobre terapias; vídeos educativos relacionados con temas de interés (cocina, manualidades, etc.); mapas, con advertencias de posibles peligros; contenido generado por familiares: vídeos, fotografías o música.

Los creadores de contenidos pueden personalizar los servicios según las necesidades y hábitos del usuario. Además, cada área, con los servicios relacionados que ofrece, ha sido diseñada en base a los requisitos de usuarios recogidos de un análisis específico de los contenidos (DeBeni, 2009; DeBeni & Carretti, 2010).

• PC de RA. El PC de realidad aumentada es un servidor dedicado, conectado a un punto de conexión inalámbrica. Actúa como el centro de procesado del sistema, y no está limitado por el peso, el consumo energético o la ergonomía que afecta a los dispositivos portátiles. El PC de RA distribuye de forma automática contenido de vídeo y audio que se transmite en tiempo real a la tableta y al DCPAR, monitorizando la base de datos a intervalos de tiempo determinados para recoger los cambios en la planificación programada. También es responsable de la ejecución de los algoritmos de realidad aumentada, reconocimiento del entorno y determinación de la orientación del DCPAR mediante el procesado de los datos transmitidos por su cámara. Otros servicios como reconocimiento facial o análisis de comportamiento pueden incluirse como actualizaciones del software, evitando así cambios en el hardware. Este componente está diseñado para que funcione de forma altamente automatizada, y comienza a mostrar contenido tras ser encendido igual que cualquier otro electrodoméstico. En entornos con múltiples usuarios finales, como centros de cuidado, el sistema debe ser gestionado por un operador, como un enfermero o gerontólogo.

• Tableta. Se trata de una tableta comercial en la que se ha instalado software intuitivo con un sistema de asistencia a la orientación, construido siguiendo los criterios de terapia de orientación en la realidad, con el fin de ayudar a personas con problemas cognitivos. La terapia permite la estimulación de los usuarios a lo largo del día mediante un flujo continuo de información relacionada con sus datos personales, tiempo y espacio. Facilita la construcción de representaciones cognitivas coherentes a los mayores, permitiendo una mejor comprensión del contexto que les rodea y el papel que tienen en él (Essay UK, 2006). La interfaz del software trata de simplificar la navegación del usuario dentro de los servicios y aplicaciones, así como estimular de manera continua su memoria. La tableta contiene cuatro aplicaciones principales: calendario, conversación, juegos y entretenimiento. Cada campo representa un servicio dedicado, que promueve la actividad cerebral de la persona durante su uso y ayuda a recordar citas y tareas pendientes del día a día.

• DCPAR. El prototipo es un dispositivo portátil que contiene una cámara integrada, un picoproyector y un transmisor, contenidos en una carcasa de 10x 14x3 cm, con una cinta que se coloca alrededor del cuello. Aunque se trata de un hardware especializado, se utilizaron componentes de bajo coste con el objetivo de hacerlo asequible. Actúa como un dispositivo de entrada y salida de vídeo, transmitiendo el entorno que visualiza la cámara, que procesa el PC de AR, y proyectando la imagen que genera este. Esto permite que se muestren avisos multimedia asociados a un lugar, de forma automática. Por ejemplo, cuando el usuario se acerca a un fogón, proyecta un aviso acerca del riesgo potencial. Se puede programar un contenido más interactivo, por ejemplo una flecha a modo de guía que se ajusta en tiempo real dependiendo de la posición del usuario.

• Instalación. El punto de acceso inalámbrico y el PC de AR utilizan la red disponible en el lugar de instalación, y se colocan en una posición con buena cobertura inalámbrica. Para que los algoritmos de reconocimiento y localización de realidad aumentada funcionen correctamente, se debe preparar previamente un mapa 3D del entorno. Este paso se lleva a cabo utilizando un software especializado (Saracchini & Ortega, 2014) que se ejecuta en un ordenador portátil conectado a un sensor de profundidad, como Microsoft Kinect, que escanea los puntos de interés. El mapa 3D generado se guarda en la base de datos, donde el creador de contenido puede configurar la programación de RA de acuerdo a las necesidades del usuario. El procedimiento de escaneado se realiza en no más de dos horas, dependiendo del tamaño de la zona escaneada. Una vez completado, el sistema de asistencia está preparado para ser utilizado. Cualquier cambio significativo en el entorno, como pintar las paredes, mover o cambiar muebles, puede requerir un nuevo escaneado, ya que el sistema de localización se basa en referencias visuales.

2.2. Validación con usuarios

Con el fin de evaluar adecuadamente el diseño propuesto es necesario analizar su utilización con personas mayores, determinando los fallos y las deficiencias con respecto a sus necesidades, y estableciendo los beneficios concretos que aporta a su rutina. Sobre todo, en este contexto, una de las contribuciones clave que debe ser analizada es la reducción del aislamiento social, así como las mejoras en socialización, integración e interacción con personas mayores afectadas por pérdidas temporales de memoria. Teniendo en cuenta estos factores, las pruebas se han llevado a cabo en sesiones de grupo y con individuos piloto, en casas de cuidado de mayores y centros de salud localizados en la provincia de Ancona (Italia).

La fase de validación del sistema con usuarios se ha dividido en dos fases: un grupo focal que incluye personas mayores, cuidadores y expertos (fase 1 de las pruebas de rendimiento) y sesiones con individuos piloto en escenarios reales (fase 2 de las pruebas de rendimiento).

La primera parte de las pruebas –sesiones de grupo– trata de entender el punto de vista de las personas mayores acerca de los dos componentes del sistema de asistencia a través de un grupo focal en cada una de las instalaciones, con el objetivo de ayudar a los mayores a acercarse a esta nueva tecnología, y de facilitar su comprensión de los servicios y aplicaciones que incluye. Las sesiones permiten explicar las funciones y características de los dispositivos y recoger una primera opinión. Se invitó a un grupo de expertos para que evaluaran los dispositivos y su interacción con las personas mayores. Como herramienta preventiva no médica, el sistema no está destinado a pacientes que padecen problemas cognitivos serios, es más, la escala Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) (Herndon, 2006) se utilizó como referencia durante el proceso de selección de los participantes. Las pruebas estaban destinadas a personas de escala CDR 0 a CDR1 (tabla 1).

Junto con los grupos focales, los expertos evaluaron el impacto de los dispositivos en la interacción social, y de qué manera ofrecía autonomía, bienestar y felicidad cada una de las aplicaciones individuales del sistema. También valoraron cuál de las aplicaciones era la preferida por los usuarios finales, y cómo el uso de las redes sociales genera nuevos intereses en personas mayores. Finalmente, se valoraron otros aspectos, como la usabilidad de la tableta y las funcionalidades deseables a incluir en el DCPAR. El primer grupo focal se estableció en Chiaravalle, en la residencia de ancianos «La Ginestra», con un total de 12 participantes entre personas mayores, cuidadores y expertos. Siete voluntarios participaron como pilotos y dos como observadores. El equipo de expertos estaba compuesto por el coordinador del asilo, un experto en Alzheimer y un operador responsable de actividades recreativas.

El segundo grupo estaba en Jesi, en la residencia de ancianos «Victor Emanuele II». Este grupo estaba compuesto por un grupo mayor de participantes, aunque la mayoría de ellos eran simples observadores (cuatro pilotos y ocho observadores). Los dispositivos y su uso fueron evaluados por el coordinador del asilo, un miembro de la Asociación Alzheimer Marche, un operador social de salud, dos operadores responsables de actividades recreativas, y un familiar de una de las personas mayores.

El tercer grupo focal estaba situado en Falconara Marittima en el centro de cuidados «Visintini», dedicado a pacientes que sufren de Alzheimer y demencia senil. Este grupo estaba enfocado a evaluar la interacción de personas mayores con problemas cognitivos más severos, y era significativamente menor que los grupos previos. El grupo recibía el soporte del coordinador del centro de día, un psicólogo especializado en deficiencias cognitivas, y un voluntario del centro.

La segunda sesión de pruebas involucró a 13 pilotos: diez mujeres y tres hombres con una media de edad de 80,3 años. Su perfil físico y cognitivo era variado: seis de ellos en sillas de ruedas debido al dolor físico o a enfermedades; dos con problemas cognitivos leves (CDR 0,5 y 1), y cinco en buen estado de salud física y mental. Todos los participantes vivían en las instalaciones de las pruebas excepto tres de ellos: uno vivía en su propia casa y dos pasaban el día en el centro pero volvían por la noche a la casa de sus familiares (tablas 2 y 3).

3. Resultados

3.1. Reacción de los usuarios finales

De las personas mayores involucradas en los pilotos individuales, el 30,8% se encontraron completamente a gusto durante las pruebas, y el 30,8% suficientemente a gusto, lo que supone un 61,6% de opiniones positivas. El resto de la población (30,4%) se sentía incómoda, aunque ninguno rechazó completamente el dispositivo. Esta reacción se consideró normal para este grupo objetivo dada su falta de familiaridad y cierto grado de resistencia hacia su utilización (gráfico 1).

Las opiniones recogidas después de las pruebas con la tableta fueron mayoritariamente positivas y casi todos los mayores entrevistados experimentaron inicialmente vergüenza e inseguridad, seguido de un sentimiento de curiosidad y entusiasmo. Los mayores consideraron que la tableta es «una buena herramienta para mantenerse en contacto con la familia y los amigos» con un «acceso sencillo» capaz de promover su «bienestar y la idea de no sentirse solo…». Muchos de ellos, tras la resistencia inicial y el miedo a la novedad, aprendieron a manejar la tableta y el DCPAR con soltura. Una vez entendidas sus funcionalidades, mostraron entusiasmo y voluntad de aprender mucho más acerca de las funciones incluidas. Esta participación progresiva dio paso a una colaboración positiva, pero también produjo dos problemas críticos: el problema de la dependencia del dispositivo y el manejo de las reacciones negativas de los mayores y la decepción después de finalizar las pruebas. Los expertos confirmaron que el problema de la «adicción» es normal en este grupo objetivo, gente normalmente solitaria con pocas posibilidades de interacción social, o que vive una vida monótona con pocos estímulos cognitivos, por lo que aprecian cualquier forma de implicación que ejercite su memoria.

•Tableta. Según los resultados de la encuesta, los mayores escogieron como servicios favoritos la galería de fotos (46,2%), seguido del vídeo y TV (23,1%). Se obtuvo un porcentaje similar (15,4%) para las llamadas y mensajería, así como el reproductor de música. Los participantes mostraron poco interés por otras aplicaciones. En realidad, se centraban sobre todo en el contenido relacionado con familiares y amigos. Concretamente, los participantes con problemas cognitivos consideraban que la agenda es demasiado difícil de utilizar.

Los participantes querían mejorar el álbum de fotos y las aplicaciones de música, especialmente en lo referente al volumen de la música (problemas de oído) y el tamaño de la imagen (problemas de visión). También manifestaron el deseo de disponer de más contenido multimedia de su época, así como de una interfaz más intuitiva (gráfico 2).

• DCPAR. En general, sentían que el DCPAR es voluminoso y pesado, y a veces tenían dificultades para comprender adecuadamente su utilización. Aun así, la mayoría de ellos fueron capaces de utilizar la tableta y las funcionalidades de RA con un alto grado de autonomía. En cuanto a su funcionalidad, los usuarios se mostraron muy satisfechos con la capacidad de proyectar imágenes y películas de parientes, o de temas de interés como deportes o religión. La capacidad de respuesta del aparato se consideró adecuada, adaptando adecuadamente la imagen proyectada a la geometría del entorno. Las funcionalidades que más esperaban del DCPAR son la visualización activa de contenido producido por familiares y su uso como agenda, en contraste con las dificultades encontradas en la tableta (gráfico 3).

Se encontró un problema significativo relativo a la ergonomía del aparato: debido a la postura del usuario y la inclinación del picoproyector, la calidad de la proyección de la imagen era inferior a la esperada. Además, se consideraba incómodo debido a que se lleva alrededor del cuello, pudiendo aumentar los problemas causados por la artrosis, comúnmente presente en personas de avanzada edad.

3.2. Reacción de los cuidadores

Los cuidadores consideran que el sistema de asistencia es una buena herramienta de apoyo, pero aún es demasiado complicada para ser utilizada de forma independiente por una persona mayor, especialmente si esa persona tiene algún problema físico o cognitivo. Esta opinión se vio reforzada por los sujetos de prueba y sus familias, que sugirieron mejoras en ciertos detalles de la interfaz de usuario, como el «tamaño del teclado» y una participación completa de los cuidadores, «quienes deben realizar un papel central durante el acercamiento de los mayores y su entrenamiento con la nueva tecnología». También indicaron la adición de ejercicios que promuevan la asociación entre lugares e imágenes como medio para estimular la percepción espacial dentro de los entornos –instalaciones o en el hogar– e introducir la posibilidad de realizar videollamadas con amigos y familiares.

En opinión de los cuidadores, el uso del sistema propuesto puede cambiar dependiendo del entorno en el que se utiliza. En la casa de la persona mayor es útil para memorizar citas y eventos, como sistema de alerta contra obstáculos, como recordatorio para la adecuada toma de medicamentos, como sistema telefónico con su propia red social, y como medio para estimular la memoria a corto plazo y los intereses del usuario. En un centro de cuidado el sistema es importante para mejorar la relación entre usuarios al usarlo como dispositivo de entretenimiento, para recordar la planificación diaria con la hora y las actividades, y también puede facilitar la identificación de los objetos que se encuentran en el lugar mediante la asociación del nombre proyectado mediante RA.

Los cuidadores observaron cómo los usuarios y las personas mayores cercanas aprecian las imágenes del DCPAR. También se planteó su uso como herramienta para estimular la movilidad de los mayores: los sujetos de pruebas se sentían empujados a investigar las habitaciones del lugar, caminando mucho durante las pruebas piloto. Su dificultad de uso para personas con problemas físicos (por ejemplo, mayores en silla de ruedas) debido al ángulo de visión, y la dificultad de llevarlo durante tiempo prolongado se identificaron como puntos débiles del sistema. Además se sugirió recurrir a la ayuda de los cuidadores o familiares para gestionar las citas y los datos personales del usuario en la base de datos en línea.

Finalmente, los cuidadores identificaron que la mejor forma de fomentar el uso de los aparatos TIC es a través de un acercamiento gradual con ayuda constante de un «entrenador» (por ejemplo, un cuidador o familiar) durante los primeros pasos. Este acercamiento a una nueva tecnología requiere de la participación de personas del círculo próximo al usuario, ya que son mucho más cooperativos con ellos que con extraños. Otra forma de poner a los mayores en contacto con el sistema podría ser a través de acciones recreativas, como un juego educativo.

Los expertos que participaron en la validación del sistema consideran fundamental que los mayores estén involucrados desde las primeras fases, con el objetivo de evitar su tendencia a aislarse. Puede representar una herramienta excelente para los mayores con casos de demencia, ayudando a la terapia no farmacológica, aunque en este caso el usuario necesitará el apoyo de un operador.

4. Conclusiones

El análisis de las necesidades de los usuarios y su grado de aceptación de la solución tecnológica propuesta han puesto de manifiesto lo importante que es para las personas mayores mantenerse en contacto con otras personas, con el objetivo de estimular positivamente sus funciones cognitivas y evitar el aislamiento social. El componente relacional se ha tenido en cuenta cuidadosamente durante la fase de validación del prototipo a fin de comprender el valor real de la tecnología probada y su capacidad para influenciar el mercado de forma efectiva.

Los resultados muestran que la mayoría de las personas mayores quieren participar en el proceso digital, pero con atención especial a sus conocimientos previos y experiencia, lo que requiere un profundo respeto hacia sus tiempos de aprendizaje. La mayoría de las dificultades encontradas están relacionadas con el diseño de la interfaz y el nivel de usabilidad con respecto a sus capacidades cognitivas específicas, no con el nivel de interés o de comprensión de las personas mayores hacia el TIC. Esto refuerza la noción de que «estas generaciones de mayores tienen necesidad y anhelo de aprender y ven este momento de su vida, el adecuado para hacerlo acercándose a las TIC» (Agudo & al., 2012).

La realidad aumentada juega un papel importante en el sistema de asistencia, ya que ofrece detección automática del contexto y una introducción realista de información en el entorno. En contraste con la tableta, el sistema es capaz de interactuar con el usuario de manera autónoma, ofreciendo el concepto de «asistente personal», que acompaña al usuario ayudándolo en sus tareas en lugar de desviarlo de su rutina normal cuando quiere disfrutar de los beneficios de las TIC. Esta característica mejora potencialmente su movilidad, y la información que se pone al servicio de los mayores que sufren de pérdidas temporales de memoria se convierte en un valor añadido –o mejor, «aumentado»– que se expresa en el canal más accesible para el grupo objetivo: la asociación entre experiencia e imagen. El emparejamiento de imágenes y mensajes auditivos o escritos, de acuerdo a expertos en neuropsicología cognitiva, promueve y estimula la actividad cerebral y ayuda a las personas mayores a mantener en buen estado su memoria, durante tanto tiempo como sea posible (Essay UK, 2006; Mazzucchi, 2008). El análisis realizado en este estudio ha producido información que resulta valiosa de cara al diseño de un aparato de RA para personas mayores. Como se recoge de los usuarios y expertos involucrados, el prototipo era demasiado voluminoso y pesado. El aparato debería utilizar un diseño más ergonómico, y debería presentar dificultades mínimas para proyectar una imagen en el campo de visión, si se espera que se utilice de forma continua e integrada de forma constante en la vida del usuario. Para conseguir esta meta debería realizarse una investigación más a fondo sobre la miniaturización y ergonomía enfocada a dispositivos electrónicos portátiles.

Se necesitan más pruebas con personas mayores que vivan solas. Sus necesidades y puntos de vista podrían diferir considerablemente de las de otros mayores que están en constante contacto con cuidadores, y nuestro sondeo no cubre este aspecto. En este momento estamos realizando estudios con voluntarios en esas condiciones, con el fin de medir el grado de impacto que puede suponer el sistema propuesto.

Se puede concluir que la solución tecnológica propuesta supone un avance hacia la introducción de personas mayores a las TIC, con un impacto potencialmente beneficioso en sus vidas. La tableta y el DCPAR tienen potencial para promover la interacción social y estimular de forma virtual el proceso cognitivo, mejorando su autosuficiencia y calidad de vida. El sistema rechaza convertirse en una simple herramienta para compensar carencias o delegar funciones, un efecto de las TIC que las personas mayores consideran como no deseado (HernándezEncuentra & al., 2009). En cambio, esta tecnología tiene el potencial de complementar el proceso de crecimiento personal en esta etapa de la vida, proporcionando acceso a contenido educativo y recreativo y permitiendo que los mayores eviten los efectos del aislamiento social al mantenerlos en contacto con familiares, amigos y la sociedad. En investigaciones futuras se estudiarán mejoras a esta tecnología, con el objetivo de conseguir los siguientes fines:

• Garantizar a personas mayores que viven solas la posibilidad de mantenerse en contacto con sus amigos y familia.

• Promover la autonomía de los mayores a través de contenidos educativos y asistencia.

• Aumentar la sensación de seguridad y serenidad mediante la posibilidad de implementar en el sistema un centro de atención dedicado que pueda proporcionar asistencia rápida.

Con las personas mayores «aumentadas» se ha generado la expectativa de que las tecnologías de RA integradas en dispositivos móviles convertirán su contacto con TIC y herramientas digitales en una experiencia más natural y placentera. El progreso en tecnologías de visualización y dispositivos portátiles, como las Google Glass recientemente desarrolladas y los relojes inteligentes, potencian la idea de que las TIC tienen el potencial de llegar a todos los miembros de la sociedad sin importar su edad o género.

Agradecimientos

El estudio presentado en este artículo ha sido financiado por el Ambient Assisted Living Joint Programme (AAL), y es parte del proyecto Nacodeal (ref. AAL20103116).

Referencias

Arvanitis, T., Petrou, A., & al. (2009). Human Factors and Qualitative pedagogical evaluation of a Mobile Augmented Reality System for Science Education Used by Learners with Physical Disabilities. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 13(3), 243-250. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00779-007-0187-7

Avilés, E., Villanueva, I., García-Macías, J., & Palafox, L. (2009). Taking Care of Our Elders Through Augmented Spaces. Proceedings of Latin American Web Congress, 16-21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/LA-WEB.2009.30

Bower, M., Howe, C., McCredie, N., Robinson, A., & Grover, D. (2014). Augmented Reality in Education – Cases, Places and Potentials. Educational Media International, 51(1), 1-15. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2014.889400

Chiatti, C. (2013). The UP-TECH Project, an Intervention to Support Caregivers of Alzheimer’s Disease Patients in Italy: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials, 14(1), 155. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-14-155

Cutler, S.J. (2007). Ageism and Technology. Generations. Journal of the American Society on Aging, 29(3), 67-72.

De-Beni, R. (2009). Psicologia dell’invecchiamento. Bologna: il Mulino.

De-Beni, R., & Carretti, B. (2010). Come migliorare la memoria nell’invecchiamento. Padova (Italy): Psicologia Contemporanea.

Engel, J., Schöps, T., & Cremers, D. (2014). LSD-SLAM: Large-Scale Direct Monocular SLAM. European Conference on Computer Vision-ECCV 2014. (pp. 834-849). Springer International Publishing. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10605-2_54

Essay UK. (2006). The Benefits of Therapies Activies such as Reality Orientation. Essay UK web-page. (http://goo.gl/qTH3kU) (10-09-2014).

European Commision. (2014). Eurostat. Population Structure and Ageing. Eurostat Web-page (http://goo.gl/4gyNuI) (10-09-2014).

Henry, P., Krainin, M., & al. (2012). Rgb-D Mapping: Using Kinect-style Depth Cameras for Denser 3D Modelling of Indoor Environments. The International Journal of Robotics Research, 31(5), 647-663. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0278364911434148

Hernández-Encuentra, E., Pousada, M., & Gómez-Zuñiga, B. (2009). ICT and Older People: Beyond Usability. Educational Gerontology, 35(3), 226-245. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03601270802466934

Herndon, R.M. (2006). Handbook of Neurologic Rating Scales. New York, MA: Demos Medical Publishing.

Kurz, D., Fedosov, A., & al. (2014). [Poster] Towards Mobile Augmented Reality for the Elderly. Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality, 275-276. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ISMAR.2014.6948447

López-de-Ipi-a, D., Klein, B., & Perez-Velasco, J. (2013). Towards Ambient Assisted Cities and Citizens. Proceedings of 27th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications Workshops (WAINA),1343-1348. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/WAINA.2013.203

Mazzucchi, A. (2008). La riabilitazione neuropsicologica. Premesse teoriche e applicazioni cliniche. Masson (Italy): Elsevier.

Mistry, P., & Maes, P. (2009). SixthSense: A Wearable Gestural Interface. In ACM SIGGRAPH (Eds.), Asia Sketches. (p. 11). ACM. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1667146.1667160

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants part 1. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1-6 (http://goo.gl/0jT63R) (07-09-2014).

Rosenbaum, E., Klopfer, E., & Perry, J. (2007). On Location Learning: Authentic Applied Science with Networked Augmented Realities. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 16(1), 31-45. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10956-006-9036-0

Saracchini, R., & Ortega, C.C. (2014). An Easy to Use Mobile Augmented Reality Platform for Assisted Living Using Pico-projectors. (S.I. Publishing, Ed.), Computer Vision and Graphics - Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 8671, 552-561. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-11331-9_66

Wu, H., Lee, S.W., Chang, H., & Liang, J. (2013). Current Status, Opportunities and Challenges of Augmented Reality in Education. Computers & Education, 62(0), 41-49. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.024

Document information

Published on 30/06/15

Accepted on 30/06/15

Submitted on 30/06/15

Volume 23, Issue 2, 2015

DOI: 10.3916/C45-2015-07

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?