Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This article gathers together the results of a quantitative and qualitative piece of research conducted between 2007 and 2010 by the HGH «Hedabideak, Gizartea eta Hezkuntza» (Media, Society and Education) research team at the University of the Basque Country. The main aim of the research was to examine the situation of Media Literacy in the Basque Country’s school community. One of the newest aspects of this research was the study of the school community as a whole, at a specific moment and in a specific field; in other words, the students, teachers and parents of the same community. The results of the quantitative study have been taken from a survey done among 598 young people between 14 and 18 years old enrolled in Secondary or Further Education, or in Vocational Training courses. The qualitative study took into account the information extracted from ten focus groups and six in-depth interviews. Young people between the ages of 14 and 18, parents between 40 and 55, and eight experts of different ages took part in the discussions. Through the in-depth interviews the research team observed the opinions of eight educators who teach Education in Media. According to the results, the education system should include media education among its priorities.

1. Introduction

This piece of work has been produced by the research team known as the HGH (Mass media, Society and Education) set up in 2003. It is a multidisciplinary team that groups together lecturers belonging to different knowledge areas –media communication, journalism and art education– who work in various faculties of the University of the Basque Country.

The conclusions presented here are the result of the second research project carried out by this group. The work started at the end of 2007 and was completed during the first semester of 2010. The main aim was to research the current degree of media literacy of the Basque school community as a whole –pupils, teachers and parents or guardians– by applying sufficiently proven quantitative and qualitative methods which are dealt with in further detail below.

Over the last 40 years many authors have made valuable contributions to this subject (Media Literacy). In the Anglo-Saxon sphere the ones that stand out in particular owing to their global perspective are those produced by Mastermann (1979, 1980, 1985, 1993), Luckham (1975), Firth (1976), Golay (1973), Gerbner (1983), Jones (1984) and Duncan (1996). More recent are the contributions of Nathanson (2002, 2004), Buckingham (2005), Stein & Prewett (2009), Larson (2009), Livingstone & Brake (2010) and Gainer (2010). Some of the contributions in Spanish worthy of mention are Kaplun (1998), Aparici (1994), García Matilla (1996, 2004), Aguaded (1998, 2000), Orozco (1999) and Ferrés (2007).

Other authors have thrown themselves into applied research taken to the classrooms. This is the case of pieces of work by teachers like Hall & Whannel (1964), Galtung & Ruge (1965), Berger (1972), Cohen & Young (1973), Hall (1977) and Bonney & Wilson (1983). It would be unforgivable to omit from this list the French authority Celestin Freinet, the true father of popular pedagogy and pioneer of the introduction of the newspaper into the school. It would also be an indescribable oversight to ignore the work carried out over the last 25 years by the journal Comunicar in the Latin American sphere. In the last decade alone this journal has published many pieces of research on media literacy from a range of viewpoints. So worth highlighting are the theoretical pieces of work on media competences published by Ferrés (2007) or on digital literacy by Moreno (2008). Also relevant have been the contributions on Educommunication made by Barranquero (2007), Cortes de Cervantes (2006), Tucho (2006), Ambrós (2006) and Percebal & Tejedor (2008). We end this list by citing the research which, like our own, has focussed its analysis on the media literacy of youngsters in the area of Argentina (Fleitas & Zamponi, 2002), Brazil (Esperón 2005) or Spain (Marí, 2006).

The data obtained in all these pieces of work have served to illustrate our working hypothesis better by focussing it specifically on Basque society, a community with its own identity, bilingualism and with a high degree of technological development.

A central hypothesis was an apparently obvious starting point for us but it needed the certification of the data: the failure to address the subject of communication in a mainstream way is leading to serious gaps in the media literacy of the Basque school community as a whole. This hypothesis necessarily entails a series of RQ Research Questions that the current research aims to shed light on. They are as follows:

RQ1: How do teachers who have worked on this subject at high schools rate their own work?

RQ2: What is the degree of media literacy of Basque youngsters between 14 and 18? Are they capable of interpreting the keys of media language?

RQ3: Is it possible to achieve an acceptable level of media literacy without doing specific media studies?

RQ4: In the family environment is there any kind of filter or criterion imposed by parents or guardians when it comes to consuming mass media?

RQ5: How have guardians been experiencing the technology revolution in recent years?

2. Material and methods.

The results of this piece of research are based on methods for quantitative and qualitative analysis applied to the school community as a whole in its different strata: pupils, teachers and parents or guardians. The combination of the two techniques has been fundamental when correctly evaluating the global nature of the study, and this has allowed us to put the piece of data within the framework of its natural context without straying one inch from the accuracy of the number.

Let us start by detailing the qualitative methodology. The group used two widely recognised techniques of qualitative analysis. We are referring to the focus groups or discussion groups (a total of ten were carried out; eight among pupils between 14 and 18 and another two with parents) and in-depth semi-structured interviews.

2.1. Variables used.

The composition of the eight focus groups conducted among the youngsters was structured bearing in mind two independent variables:

- The age and academic levels of the participants. On the one hand, students in the 3rd and 4th years in Statutory Secondary Education (14-16 years) were chosen, and on the other, youngsters in the first and second years of the Sixth form (16-18 years).

- The syllabus. The groups were structured on the basis of the presence or absence of some kind of subject related to educommunication.

The dependent variable used in the three strata researched has been the state of media literacy itself.

2.2. Procedure.

- The opinions of the pupils were gathered in eight groups belonging to as many schools1. Four of them comprised students doing sixth form studies specialising in arts or having disciplines directly linked to educommunication included in their syllabuses. This variable did not appear in the remaining four. In all the cases the debate was initiated by the viewing of the opening sequence2 of the film «The Lion King» (Walt Disney, 1994).

- To find out the views of the teachers, five in-depth interviews were carried out and seven educators participated in them3, (in one of them the people taking part numbered three).

- To find out the opinion of the parents or guardians, two focus groups were held. The first took place in Gasteiz (Vitoria); the second in Bilbao. In the first, the group was made up of a random selection, while the second was formed by the executive committee of the EHIGE, the organisation coordinating Parents in the Basque Country and which brings together 240 associations. In addition, a person in a position of authority in this association with broad experience in the subject gave an in-depth interview. I

The quantitative data were extracted from a survey carried out between November 2009 and February 2010 by the company Aztiker. The universe of the survey was made up of 107,467 young school pupils in the Basque Country between the ages of 14 and 18, from high schools and vocational training centres. A representative sample made up of the 598 youngsters was selected from this broad universe4. The field work was carried out by means of the «simultaneous group application» method (Wimmer & Dominick, 1996: 136). This means that the information is gathered on the basis of a self-applied questionnaire. Each person surveyed fills in his/her own questionnaire. The team conducting the survey went to the schools, to the pupils' normal classrooms. Groups of 15 to 20 youngsters were formed. Prior to this, a person conducting the survey from the above-mentioned company explained to them in detail the mechanics of the questionnaire, and projected the audiovisual material on which some of the questions were based.

3. Results. The main results of our research are summarised as follows.

3.1. Qualitative research

We will be starting with the qualitative research. We have structured these reflections on the basis of the three strata analysed: teachers, pupils and parents or guardians.

3.1.1. Experiences of the teachers

The interviews carried out revealed a very broad teacher profile. In all the cases ITCs were determining factors, but their proximity to the educommunication sphere had sprung from various concerns: the world of the videoclip, cinema, the photograph, the Internet or computing, for example. All the teachers interviewed were self-taught; they had trained themselves after many hours spent accumulating and contrasting multiple experiences.

Among the testimonies gathered some were particularly illustrative, like for example the experience of the Amara Berri public school in Donostia-San Sebastian. This school, founded in 1979, has come up with its own method of educommunication called the «Amara Berri Sistema». It is a benchmark in the Basque Country’s school community to the point where it has been adopted by another 18-20 schools in the area. The main players are students in primary education. The pupils do not follow an ordinary text book for studying mathematics, for example; they learn the metric system as people in charge of an imaginary shop, or what a mortgage is when they have to repay a loan to the bank which is run by another classmate. Nor do they have ordinary language classes. Instead, they produce a newspaper every day, edit radio and television programmes, interact through their «txikiweb» website and even offer talks with those who have overcome their fear of speaking in public. The process is very co-operative and is always supervised by the teachers. Since 1990 when the Basque Government recognised the innovative nature of the school, the Amara Berri System has been perfected from year to year.

All the teachers interviewed have coincided when demanding greater commitment from people in charge of Education. In the view of these teachers, educommunication cannot be a mere technological discipline, but an instrument capable of training free, 21st century citizens. This need becomes more acute if one takes into consideration the background with which the students arrive in the classrooms. The teacher MPY reflected on this in the following terms: «This is a generation with a vast accumulation of technical knowledge: they have been glued to the telly, they obtain and swap materials, photos and masses of things over the Internet, they know how to look for new things on it. They have accumulated a vast background even though they don’t often realise it. And when they get the chance, they surpass you immediately. The teacher has to be humble; he or she has to give them the bases and then let them flourish».

3.1.2. Interpretative competences of the youngsters

The main aim of the focus groups among the youngsters was not only to delve into their interpretative competences, but also to find out if significant differences really exist in the degree of media literacy among those who have or have not done subjects linked to educommunication.

We would start off by saying that differences do exist. The adolescents trained in educommunication display an interpretative maturity greater than that of the ones who have not done these kinds of subjects. That is particularly clear when it comes to differentiating between denotation and connotation, when a determined shot is designated or when they interpret the communicative function of a specific frame. Nevertheless, it is equally true that for other youngsters without training in educommunication, the mere accumulation of cultural text throughout their lives has generated for them the necessary intellectual springboard to develop certain interpretative capacities. Even in the groups in which no one was capable of citing a «grammatical» film norm (frame, lighting), there were youngsters capable of making interesting reflections on another level.

In our research, the method of the focus groups itself turned out to be revealing. As the discussion progressed, many participants modified totally naturally and spontaneously their initial points of view and adopted those of their fellow group members. It is clear that leadership and inertias resulting from dominant opinions come into play during the group discussion. Nevertheless, group communication emerges as a very interesting method for social analysis.

Cultural maturity emerges as a determining factor in interpretative competences. The consideration of the low cognitive development of children is overcome as they get older. The new knowledge acquired with the passing of time can generate autonomous, critical thought. This was the reasoning in one of the interventions of a student of Secondary School with training in educommunication: «I saw the film when I was small and I didn’t realise about these things; but now, when you watch it with your little sister, you say… crikey (…) They’re trying to get an idea into your head, but then, when you start to think for yourself, you can change that idea, and that is what usually happens, isn’t it?».

In the focus groups, Disney emerged as a megacorporation illustrating the symbolic, children’s universe. We reproduce below a reflection in a group of Secondary School with educommunication training: «It’s a typical Disney film. As it’s made for kids, it has to respond to their capacity for understanding (…). That’s why they use animals, because it’s a film for kids. If people were presented it would be very strange talking about these things with people; with animals it’s easier to get the kids hooked (…) I don’t think it’s right to fill your heads with these ideas from childhood».

The reflection displays a capacity to criticise Disney’s communicative strategy. It is probably the result of the greater media training of this group. For the rest of the groups, Disney is something «parents trust».

3.1.3. Parents’ concerns

Concern. this is perhaps the sensation that best defines the state that overwhelms parents when faced with these questions. It is a concern linked to a certain confusion caused by the lack of knowledge towards the new technologies that many confess to. The opinions collected through the focus groups were complemented by the information coming out of the in-depth interview given by one representative of the parents (AE) a person with decades of experience in the association and well-versed in the subject being studied.

However, it would be as well when addressing the phenomenon to point out that among the parents or guardians there are appreciable differences. As the aforementioned AE reveals, the digital gap is also present within this group: «Nowadays, there are considerable differences between people. The attitude towards the new technologies of a person of 35 is very different from that of a person of 55. In twenty years things have changed an awful lot, and you notice that when you speak to parents».

In general, parents accept the arrival of the new technologies. They believe that they are a reflection of the society and see in them more positive aspects (new forms of communication, interactivity, etc.) than negative ones. However, they do not conceal a feeling of uncertainty, especially when they find that their own children are way ahead of them.

Nostalgia could be another of the keys. Nostalgia for the co-operative street games that parents enjoyed as children and for certain habits that are being lost, like going to libraries. That nostalgia is also linked to the hope of a better future. AE insists on linking the technological perspective and a critical attitude together: «The current panorama is going to change radically in ten years’ time. Schools will be totally different. 40% of the teachers are set to retire. In the family environment more than half the parents will not be aware of hardly anything, but they going to have to adapt to the new times, thanks to the influence of their offspring. They will hang on to their values, their ideas, but it will be adaptation; not change».

3.2. Quantitative research

Below we reproduce the main results extracted from the survey conducted among 598 Basque youngsters between 14 and 18. The data are grouped into seven broad sections: media language (maximum 20 points), technological language (max. 15 points), production (12), critical reception (13), values and ideology (25) and aesthetics (15). This produced a grading system from 0 to 100 points which indicated to us the degree of media literacy of each person surveyed. The following graphs summarize the principle findings of our research.

3.2.1. Media language

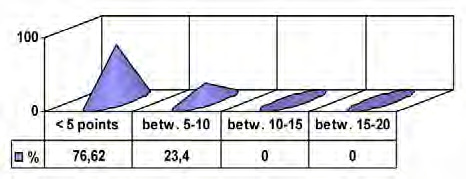

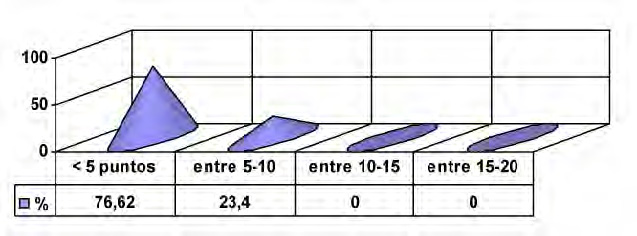

According to the responses gathered, we saw that school adolescents and youngsters were not very well trained in media language. Only a quarter of them were close to passing. The remaining three quarters failed miserably (graph 1).

Graph 1: Degree of knowledge of media language. Range: 0-20 points

Source: Aztiker Survey In-house production

3.2.2. Technology

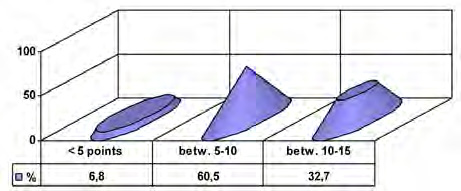

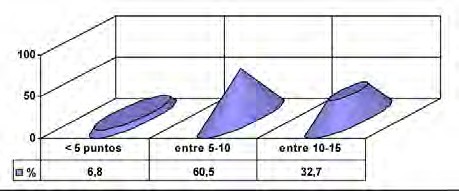

This is the section in which our team found the highest number of correct answers. In general, it can be said that Basque youngsters have a good idea about how audiovisual equipment works. The data show that nine out of ten are capable of using communicative technologies effectively as far as receivers are concerned. They are autonomous in this respect (graph 2).

Graph 2: Degree of knowledge and use of audiovisual equipment.

Range: 0-20 points

Source: Aztiker Survey

3.3.3. Production

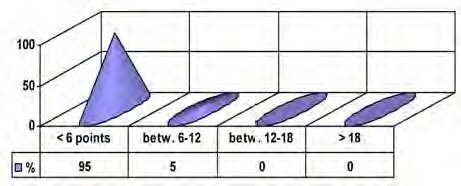

This section was designed to verify the degree of knowledge the youngsters had about the creation process of a media product. The questions aimed to find out if those surveyed were capable of: a) describing the jobs of the professionals (for example, of the producers, stage managers, etc.) responsible for the work to produce media materials, and b) to produce a list of the tasks necessary to make a product.

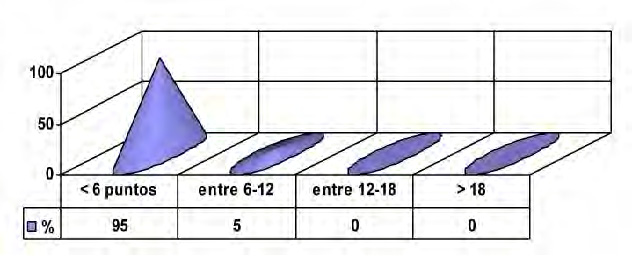

According to the data gathered, it can be said that the level of knowledge about production is very limited among these youngsters (see graph 3).

Graph 3: Degree of knowledge about the process to create an audiovisual product. Range: 0-12 points.

Source: Aztiker Survey Made by the research group

When it came to describing the world of production, two variables –age and gender– produced considerable statistical differences. As age increases, it is possible to appreciate a greater level of knowledge about the production system. As regards gender, the girls –in this section, too– were more capable than the boys.

3.2.4. Ideology and values

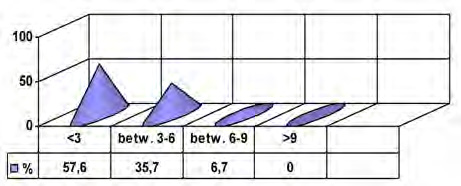

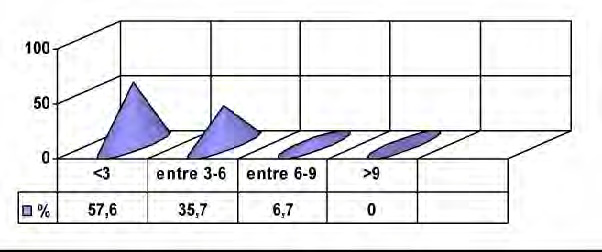

This aspect was developed on the basis of five questions. One of them was on the reflections prompted by one of the advertisements subjected to examination, and another two on whether they found a piece of news more credible if it was accompanied by an image. Those surveyed where not particularly skilful when it came to detecting the underlying ideology and values in the media texts subjected to examination (see graph 5).

Graph 4: Capacity for interpreting the ideology and values of media products correctly. Range: 0-25 points

Source: Aztiker Survey Made by the research group

In the evaluation of ideological competences we verified that the youngsters used very simple, weak reasoning when it came to grasping and describing the ideological veneer of a media product. Out of a maximum of 25 points allowed by this section no one managed to score even half.

3.2.5. Global Assessment

The summation of all the responses offers an alarming assessment. According to thus survey, no Basque schoolboy or girl would today be media literate since none of them scored more than 50 out of the possible total of 100 points. Only three out of ten came slightly closer to passing without managing to do so (see graph 7). These data call for serious reflection.

4. Discussion

The results harvested in this piece of research reveal considerable interest on the part of the Basque school community in media literacy. This interest turns into an urgent need in the light of the quantitative results arising from the survey among the youngsters.

The research exposes a Basque education system that is incapable of making the school population media literate. The youngsters are ignorant of the basics of media language. They lack structured discourse to explain in a reasoned way what they have in front of their eyes. They find both the grammar and the rhetoric of media language foreign. Logically, the educational authorities should be taking note of the data compiled here and be including educommunication among their curricular priorities. Only that way could they take effective steps forwards towards a common goal: the training of citizens who are free, media educated, capable of surviving autonomously in the self-called information society.

Notwithstanding the undoubted interest in the experiences that have been analysed in the area of educommunication in this piece of research, the curricular isolation surrounding them is palpable. The very teachers involved complain about the lack of continuity and absence of global approaches. The technicist perspective takes priority over the critical one. A fascination for technology reigns, and it can even go as far as blinding and, consequently, hampering the capacity for critical reflection.

The profile of the teachers involved in these experiences is multidisciplinary. The mastery of the new technologies has been a determining factor, but each one has reached the world of educommunication along different roads. They detect gaps in their own experiences and put them down to the lack of mainstream training in these subjects. Although these teachers largely display a really commendable dose of enthusiasm, it is also true that in some of them one can sense a certain intellectual fatigue, which is partly the result of the passing of the years. Teacher motivation is crucial in this subject (as it is in all subjects). It has been extensively shown that if the educator is capable of linking the pedagogical aims with the pupils' social and emotional context, the goals can be achieved more easily. In this respect, the new technologies open up huge possibilities as long as specific content and aims that can be easily identified by the students are added to them.

The youngsters educated in Basque schools where specific experiences in educommunication have been developed display better media literacy. It would be as well to point out that the evolving maturity itself of the youngsters –linked to their age– facilitates greater capacity for interpretation.

The very methodology used in the qualitative research –the focus groups– has emerged as an effective tool in the implementation of the objective to be achieved: media literacy.

The technological revolution occupies and worries parents. They feel overwhelmed and lacking in criteria when faced with a reality which in many cases is beyond them. They even feel incapable of setting limits on the media consumption of their children. Despite this, they see more positive aspects than negative ones in the new technologies. They are demanding a more critical use of these tools.

The results of the survey gathered here should prompt a deep cause for concern among those responsible for education and society in general, particularly if one takes into consideration that the degree of media literacy of the population as a whole will not –presumably– be greater than that demonstrated by the youngsters. The scores achieved are very poor. They point to a youth that is illiterate from the media point of view. They have advanced equipment at their disposal. They are capable in terms of their mechanical skills, but they are ignorant of the basic questions relating to media culture, the production or detection of ethical and aesthetic values underlying the media text.

Both the qualitative and quantitative results gathered here confirm the central hypothesis that gave rise to this research: the failure to address the subject of communication in a mainstream way is leading to serious gaps in the media literacy in the Basque school community as a whole. This community is set to undergo radical changes in a brief period of time. Within a decade teachers that are considerably younger than the present ones will be teaching a generation of students that is more skilled in digital strategies than the present one. The profile of the parents will evolve likewise towards more technological parameters. The research team understands that the Basque school community is facing a golden opportunity, an unbeatable opportunity to devote serious attention to a debate that affects the very backbone of the current education system: the media literacy of its citizens.

Supports

1 This research was financed by funds of the University of the Basque Country, and thanks to grants from the Departments of the Presidency and Education of the Basque Autonomous Community Government. The field work was made possible thanks to the services of the company Aztiker SL.

2 Apart from the authors of this article, the following people are members of our research group: Juan Vicente Idoyaga Arrospide, professor of Audiovisual Communication in the Department of the same name in the Faculty of Social and Communication Sciences in the University of the Basque Country and Amaia Andrieu Sanz, lecturer in the Department of the Didactics of Musical, Plastic and Body Expression at the Teacher’s University School (UPV).

Notes

1 The focus groups among the youngsters took place during the 2008-2009 academic year. Four groups were selected from the schools which had developed some kind of media studies. They were the Manteo Zubiri high school in Donostia-San Sebastian, the public high schools of Eibar and Sopela and the Mendizabala high school in Vitoria-Gasteiz. We were interested in contrasting the degree of media literacy of the pupils at the schools which did not teach these kinds of disciplines. That is why the following schools were approached: the Koldo Mitxelena in Vitoria-Gasteiz, the private Ikastola (Basque-medium school) of San Fermin in Iruñea-Pamplona and the Txurdinaga Behekoa and Gabriel Aresti public high schools in Bilbao.

2 The sequence referred to is about the public presentation of Simba, the lion cub who had just been born and who becomes the king of his community.

3 The people interviewed were: MPY, Ph.D. holder in media communication and graduate in English Philology. She taught until the 2008-2009 academic year when she retired. During her long career this interviewee carried out various experiences in media literacy at the public high schools in Sopela and Sestao in Bizkaia. The interview took place on 3 October 2008; IO, teacher at the Zubiri Manteo public high school in Donostia-San Sebastian and responsible for the European programme European Cinema and Young People within the Comenius 3 programme. The meeting took place on 7 November 2008 at the school itself; EL, teacher of Basque and person in charge of the media workshop at the Txurdinaga Beheko high school in Bilbao. The meeting took place on 16 February 2009 at the school itself; TE teacher at the San Nikolas private Ikastola (Basque-medium school) in Getxo and head of the «Globalab» experience run at the school itself. The meeting took place on 12 March, 2009; EMG, AM and AP, director and heads of the media section and the laboratory, respectively, at the Amara Berri public school in Donostia-San Sebastian. They coordinate the «Amara Berri sistema», a pioneering programme in media literacy that works with primary school children. The interview took place on 3 April, 2009 at the school itself.

4 The field work was carried out between November 2009 and February 2010. The youngsters responded to the questions in line with the education model used in the classroom (in Basque, French or Spanish). The calculation of the margin of error (attributable to completely random samples) is +/-4.1% for the whole universe with a level of dependability of 95.5%, where p=q%50.0 for the most contrary hypothesis. In total, the questionnaire was filled in at 33 schools in Alaba, Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa, Navarre and Lapurdi (Labourd), of which 15 were private and 18 public. To build the sample, the sex of the pupils, level of studies and their experience with respect to media activities were taken into account.

References

Aguaded, J. I. (2009). El Parlamento Europeo apuesta por la alfabetización mediática. Comunicar, 32.

Aguaded, J.I. (1998). Descubriendo la caja mágica. Aprendemos a ver la tele. Huelva: Grupo Comunicar.

Aguaded, J.I. (2000). La educación en medios de comunicación. Huelva: Grupo Comunicar.

Aguaded, J.I. (2009). Miopía en los nuevos planes de formación de maestros en España: ¿docentes analógicos o digitales? Comunicar 33; 7-8.

Ambrós, A. (2006). La educación en comunicación en Cataluña. Comunicar, 27; 205-210

Aparici, R. (1994). Los medios audiovisuales en la educación infantil, la educación primaria y la educación secundaria. Madrid: Uned.

Barranquero, A. (2007). Concepto, instrumentos y desafíos de la edu-comunicación para el cambio social. Comunicar 29; 115-120.

Berger, J. (1972). From Today Art is Dead in Times Educational Supplement, 1972 ko abenduaren 1.

Bonney, B. & Wilson, H. (1983). Australia’s Comercial Media. Melbourne: MacMillan.

Buckingham, D. (2005). Educación en medios. Alfabetización, aprendizaje y cultura contemporánea. Barcelona: Paidós.

Cohen, S. & Young, J. (1973). The Manufacture of News. London: Constable. CORTÉS de CERVANTES, P. (2006). Educación para los medios y las TIC: reflexiones desde América Latina. Comunicar, 26; 89-92.

Duncan, B. et al. (1996). Mass Media and Popular Culture. Toronto, Harcourt-Brace.

Esperon, T.M. (2005). Adolescentes e comunicação: espaços de aprendizagem e comunicação. Comunicar, 24; 133-141.

Ferrés, J. (2006). La competència en comunicació audiovisual: proposta articulada de dimensions i indicadors. Quaderns del CAC, monografikoa L’educació en comunicació audiovisual, 25; 9-17.

Ferrés, J. (2007). La competencia en comunicación audiovisual: dimensiones e indicadores. Comunicar, 29; 100-107.

Fiske, S.T. & Taylor, S.E. (1991). Social Cognition. Nueva Cork: McGraw-Hill.

Fleitas, A.M. & Zamponi, R.S. (2002). Actitud de los jóvenes ante los medios de comunicación. Comunicar, 19; 162-169.

Gainer, S. (2010). Critical Media Literacy in Middle School: Exploring the Politics of Representation. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53 (5); 364-373.

Galtung, J. & Ruge, M. (1965). The Structure of the Foreign News. Journal of International Peace Research, 2, 64-91.

Garcia Matilla, A. & al. (1996). La televisión educativa en España, Madrid: MEC.

Garcia Matilla, A. & al. (2004). (Ed.). Convergencia multimedia y alfabetización digital. Madrid: UCM.

Gerbner, G. (1983). Ferment in the field: 36 Communications Scholars Address Critical Issues and Research Tasks of the Discipline. Philadelphia: Annenberg School Press.

Golay, J.P. (1973). Introduction to the Language of Image and Sound. London: British Film Institute.

Hall, S. & Whankel, P. (1964). The Popular Arts. New York: Pantheon.

Hall, S. (1977). Culture, the Media and Ideological Effect in CURRAN J. & al. (Eds.). Mass Communication and Society. London: Edward Arnold.

Jones, M. (1984). Mass Media Education, Education for Communication and Mass Communication Research. Paris: Unesco.

Kaplun, M. (1998). Una pedagogía de la comunicación. Madrid: De la Torre.

Larson, L.C. (2009). E-Reading and e-Responding: New Tools for the next Generation of Readers. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53 (3); 255-258.

Livingstone, S. & Brake, D.R. (2010). On the Rapid Rise of Social Networking Sites: New Findings and Policy Implications. Children & Society, 24 (1); 75-83.

Lomas, C. (2004). Leer y escribir para entender el mundo. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, 331; 86-90.

Marí-Sáez, V.M. (2006). Jóvenes, tecnologías y el lenguaje de los vínculos. Comunicar, 27; 113-116.

Masterman, L. (1979). Television Studies: Tour approaches. London: British Film Institute.

Masterman, L. (1980). Teaching about Television. Basingstoke Hampshire: MacMillan.

Masterman, L. (1985). Teaching the Media. London: Methuen.

Masterman, L. (1993). La enseñanza de los medios de comunicación. Madrid: De la Torre.

Moreno-Rodríguez, M.D. (2008). Alfabetización digital: el pleno dominio del lápiz y el ratón. Comunicar, 30; 137-146.

Nathanson, A.I. (2002). The Unintended Effects of Parental Mediation of Television on Adolescents. Media Psychology, 4 (3); 207-230.

Nathanson, A.I. (2004). Factual and Evaluative Approaches to Modifying Children's Responses to Violent Television. Journal of Communication, 54 (2); 321-336.

Orozco, G. (1999). La televisión entra al aula. México: Fundación SNTE.

Perceval, J.M. & Tejedor, S. (2008). Los cinco grados de la comunicación en educación. Comunicar, 30; 155-163.

Stein, L. & Prewett, A. (2009). Media Literacy Education in the Social Studies: Teacher Perceptions and Curricular Challenges. Teacher Education Quarterly, 36 (1); 131-148.

Tucho, F. (2006). La educación en comunicación como eje de una educación para la ciudadanía. Comunicar, 26; 83-88.

Wimmer, R. & Dominick, J.R. (1996). La investigación científica de los medios de comunicación. Una introducción a sus métodos. Barcelona: Bosch.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El presente artículo recoge los principales resultados de una investigación cuantitativa y cualitativa llevada a cabo durante el período 2007-10 por el equipo de investigación HGH (Medios de Difusión, Sociedad y Educación) de la Universidad del País Vasco. El principal objetivo de la misma ha sido analizar el estado de la alfabetización audiovisual (Media Literacy) en el entorno de la comunidad escolar del País Vasco. Una de las principales novedades del presente trabajo radica en que se ha analizado el conjunto de la comunidad escolar en un momento y entorno concreto; es decir, teniendo en cuenta la opinión tanto de alumnado, como de profesorado y padres. Los resultados de la investigación cuantitativa se han extraído de una encuesta realizada a 598 jóvenes vascos de entre 14 y 18 años escolarizados tanto en institutos de Secundaria y Bachillerato como en centros de Formación Profesional. La investigación cualitativa se ha fundamentado en la información recogida a través de diez grupos de discusión y seis entrevistas en profundidad. En los grupos han participado jóvenes de la misma edad (entre 14 y 18 años) por una parte y padres y madres de entre 40 y 55 años por otro. En las entrevistas en profundidad, se ha testado la opinión de ocho profesores que imparten docencia en materias relacionadas con la educación en comunicación (educomunicación). A tenor de los resultados, el sistema educativo debería introducir la educomunicación entre sus prioridades.

1. Introducción

El presente trabajo ha sido elaborado por el equipo de investigación denominado HGH (Medios de comunicación, sociedad y educación) creado en 2003. Se trata de un equipo multidisciplinar que agrupa a profesores/as pertenecientes a diferentes áreas de conocimiento –comunicación audiovisual, periodismo y didáctica del arte– que trabajan en distintas facultades de la Universidad del País Vasco.

Las conclusiones que aquí se presentan son fruto del segundo proyecto de investigación realizado por este grupo. El trabajo se inició a finales de 2007 y concluyó en el primer semestre de 2010. El objetivo fundamental ha sido investigar el actual grado de alfabetización audiovisual del conjunto de la comunidad escolar vasca –alumnado, profesorado y padres/madres o tutores/as– aplicando para ello métodos cuantitativos y cualitativos suficientemente contrastados que se exponen con detalle más adelante.

Durante los últimos 40 años numerosos autores han realizado valiosas aportaciones a propósito de esta materia (Media Literacy). En el ámbito anglosajón son especialmente destacables, por su perspectiva global, los trabajos realizados por Mastermann (1979; 1980; 1985; 1993), Firth (1976), Golay (1973), Gerbner (1983), Jones (1984) y Duncan (1996). Más recientes son las aportaciones de Nathanson (2002, 2004), Buckingham (2005), Stein & Prewett (2009), Larson (2009), Livingstone & Brake (2010) y Gainer (2010). En lengua castellana merecen citarse, entre otras, las aportaciones de Kaplun (1998), Aparici (1994), García Matilla (1996, 2004), Aguaded (1998, 2000), Orozco (1999) y Ferrés (2007).

Otros autores se han volcado en investigaciones aplicadas llevadas a las aulas. Tal es el caso de los trabajos de profesores como Hall & Whannel (1964), Galtung & Ruge (1965), Berger (1972), Cohen & Young (1973), Hall (1977) y Bonney & Wilson (1983). Sería imperdonable dejar fuera de esta lista al maestro francés Freinet, auténtico padre de la pedagogía popular y precursor de la introducción del periódico en la escuela. Igualmente incalificable sería pasar por alto el trabajo que está realizando durante los últimos 25 años la revista «Comunicar» en el ámbito iberoamericano. Solamente en la última década la citada revista ha publicado numerosas investigaciones relacionadas con la alfabetización audiovisual desde diferentes puntos de vista. Así, merecen destacarse los trabajos teóricos sobre competencias audiovisuales publicados por Ferres (2007) o sobre alfabetización digital elaborado por Moreno (2008). Asimismo relevantes han sido las aportaciones que sobre Educomunicación han realizado Barranquero (2007), Cortes de Cervantes (2006), Tucho (2006), Ambrós (2006) y Percebal & Tejedor (2008). Finalizamos esta relación citando las investigaciones que –al igual que la nuestra– han centrado sus análisis en la alfabetización audiovisual de los jóvenes ya sea en el ámbito argentino (Fleitas y Zamponi, 2002), brasileño (Esperón 2005) o español (Marí, 2006).

Los datos obtenidos en todos estos trabajos han servido para ilustrar mejor nuestra hipótesis de trabajo centrándola específicamente en la sociedad vasca, una comunidad con identidad propia, bilingüe y con un elevado grado de desarrollo tecnológico.

Partimos de una hipótesis central, aparentemente evidente, pero que precisa la certificación del dato: la ausencia de forma reglada de una educación en materia de comunicación provoca serias lagunas en la alfabetización audiovisual del conjunto de la comunidad escolar vasca. Dicha hipótesis conlleva necesariamente una serie de interrogantes o RQ «Research Questions» que pretende desvelar la presente investigación. Son las siguientes:

RQ1: ¿Qué valoración hacen de su propio trabajo los educadores/as que han abordado esta materia en los institutos de secundaria?;

RQ2: ¿Cuál es el grado de alfabetización audiovisual de los jóvenes vascos de entre 14 y 18 años? ¿Son capaces de interpretar las claves del lenguaje audiovisual?;

RQ3: ¿Puede alcanzarse un aceptable grado de alfabetización audiovisual sin cursar estudios específicos relacionados con la materia?;

RQ4: ¿Existe en el entorno familiar algún tipo de filtro o criterio por parte de los padres/madres o tutores/as a la hora de consumir los medios de comunicación?

RQ5: ¿Cómo viven los tutores la revolución tecnológica de los últimos años?

2. Material y métodos.

Los resultados de la presente investigación se basan en métodos de análisis cuantitativo y cualitativo aplicados al conjunto de la comunidad escolar en sus diferentes estamentos: alumnado, profesorado y padres/madres o tutores. La combinación de ambas técnicas ha resultado fundamental a la hora de evaluar correctamente la globalidad del estudio, permitiéndonos enmarcar el dato en su contexto natural sin despegarnos un ápice de la exactitud del número.

Comencemos detallando la metodología cualitativa. El grupo ha utilizado dos técnicas de análisis cualitativo ampliamente reconocidas. Nos referimos a los «focus group» o grupos de discusión (se han realizado un total de diez; ocho entre alumnado de entre 14 y 18 años y otras dos con padres y madres) y las entrevistas en profundidad semi-estructuradas (depth semi-structured interview).

2.1. Variables utilizadas

La composición de los ocho grupos de discusión realizados entre los jóvenes se estructuró teniendo en cuenta dos variables independientes:

- La edad y nivel académicos de los participantes. Se escogió, por una parte, a alumnado de tercer y cuarto curso de la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria (14-16 años) y por otra a jóvenes de primer y segundo curso de Bachillerato (16-18 años).

- El plan de estudios. Los grupos se han estructurado en función de la presencia o ausencia de algún tipo de materia relacionada con la educación en comunicación.

La variable dependiente utilizada en los tres estamentos investigados ha sido el propio estado de la alfabetización audiovisual.

2.2. Procedimiento.

- Las opiniones del alumnado se recogieron en ocho grupos pertenecientes a otros tantos centros1. Cuatro de ellos eran de Bachillerato artístico o incluían en su currículo disciplinas relacionadas directamente con la educación en comunicación. En los otros cuatro no aparecía dicha variable. En todos los casos, el inicio de la discusión partía del visionado de la secuencia inicial2 de la película «El rey León» (Walt Disney, 1994).

- Para conocer la opinión del profesorado se realizaron cinco entrevistas en profundidad en las que participaron siete educadores3 (en una de ellas fueron tres las personas intervinientes).

- Para conocer la opinión de los padres y madres o tutores/as se realizaron dos grupos de discusión. El primero de ellos tuvo lugar en Vitoria y el segundo en Bilbao. En el primero, la composición del grupo obedeció a una muestra al azar, mientras que el segundo fue establecido por la dirección de EHIGE, la coordinadora de grupos de Padres y Madres del País Vasco que agrupa 240 asociaciones. Además de ello, se realizó una entrevista en profundidad a una responsable de esta asociación con amplia experiencia en la materia.

Los datos cuantitativos se han extraído de una encuesta llevada a cabo entre noviembre de 2009 y febrero de 2010 por la empresa Aztiker. El universo de la encuesta lo constituían 107.467 alumnos/as jóvenes escolares del País Vasco de entre 14 y 18 años, tanto de institutos como de centros de formación profesional. De ese amplio universo, se escogió una muestra representativa compuesta por los citados 598 jóvenes4. El trabajo de campo fue llevado a cabo por el método de «aplicación simultánea en grupo» (Wimmer & Dominick, 1996:136). Ello quiere decir que la información se recoge en base a un cuestionario autoaplicado. Cada encuestado rellena su propio cuestionario. Se acudió a los centros educativos, a sus aulas habituales. Se formaron grupos de 15 a 20 jóvenes. Previamente, un encuestador de la empresa citada les explicó con detalle la mecánica de la encuesta, y les mostró el material audiovisual sobre el que se basaron algunas de las preguntas.

3. Resultados

3.1. Investigación cualitativa

Comenzaremos por la investigación cualitativa. Hemos estructurado estas reflexiones en función de los tres estamentos analizados: profesorado, alumnado y padres/madres o tutores/as.

3.1.1. Experiencias del profesorado

Las entrevistas realizadas arrojan un perfil de docente muy amplio. En todos los casos, las TIC han sido determinantes, pero su acercamiento al ámbito de la educomunicación ha partido de inquietudes diversas: mundo del videoclip, el cine, la fotografía, Internet o la informática, por ejemplo. La totalidad del profesorado entrevistado es autodidacta; se han formado a sí mismos tras muchas horas de bagaje y contrastar múltiples experiencias.

Entre los testimonios recogidos algunos han sido especialmente ilustrativos, como por ejemplo, la experiencia del centro público «Amara Berri» de San Sebastián. Esta escuela, creada en 1979, ha acuñado su propio método de educomunicación denominado «Amara Berri Sistema». Se trata de todo un referente en la comunidad escolar del País Vasco, hasta el punto de que ha sido asumido por otras 18-20 escuelas del entorno. Los protagonistas son estudiantes de educación primaria. El alumnado no sigue un libro de texto al uso para estudiar matemáticas, por ejemplo; aprenden el sistema métrico como responsables de una tienda ficticia, o lo que es una hipoteca cuando les toca pagar un crédito al banco que regenta otro compañero. Tampoco tienen clase de lengua al uso. En su lugar, hacen un periódico todos los días, editan programas de radio y televisión, interactúan a través de su «txikiweb» e incluso ofrecen charlas con las que pierden el miedo a hablar en público. El proceso resulta muy cooperativo y está siempre supervisado por los docentes. Desde que en 1990 el Gobierno vasco reconociera el carácter innovador del centro, Amara Berri Sistema ha ido perfeccionándose año tras año.

Todos los profesores entrevistados han coincidido en demandar un mayor compromiso a los responsables de educación: En su opinión, la educomunicación no puede ser una mera disciplina tecnológica, sino un instrumento capaz de formar a la ciudadanía libre del siglo XXI. Dicha necesidad se hace más acuciante si se tiene en cuenta el «background» con el que los nuevos alumnos llegan a las aulas. La docente MPY reflexionaba al respecto en los siguientes términos: «Esta es una generación con un enorme bagaje de conocimiento de técnicas: Han estado colgados de la televisión, consiguen y se intercambian materiales, fotos y mil cosas por la Red, saben buscar cosas nuevas en Internet. Tienen un gran bagaje aunque muchas veces ni se den cuenta. Y cuando se les da la oportunidad te superan inmediatamente. El profe tiene que ser humilde; debe saber darles las bases y dejar que luego ellos florezcan».

3.1.2. Competencias interpretativas de los jóvenes

El objetivo prioritario de los grupos de discusión entre los jóvenes era tanto indagar acerca de sus competencias interpretativas como averiguar si realmente existían diferencias notables en el grado de alfabetización audiovisual entre quienes habían cursado o no materias relacionadas con la educomunicación.

Digamos, en primer lugar, que existen diferencias. Los adolescentes formados en educomunicación manifiestan una madurez interpretativa superior a aquellos que no han cursado este tipo de materias. Ello es especialmente evidente a la hora de diferenciar entre denotación y connotación, cuando designan un determinado plano o cuando interpretan la función comunicativa de un encuadre concreto. No obstante, es igualmente cierto que, para otros jóvenes sin formación en educomunicación, la mera acumulación de textos culturales a lo largo de su vida les ha generado el resorte intelectual necesario para desarrollar ciertas capacidades interpretativas. Incluso en los grupos en los que nadie era capaz de citar una norma «gramatical» cinematográfica (encuadre, iluminación), había jóvenes capaces de realizar reflexiones interesantes a otro nivel.

El propio método de los grupos de discusión llevado a cabo en la presente investigación resultó revelador. Conforme avanzaba el debate, muchos participantes modificaron de forma absolutamente natural y espontánea, su punto de vista inicial haciendo suyas las opiniones de otros contertulios. Es evidente que en el debate en grupo operan fenómenos de liderazgo y de inercias derivadas de las opiniones dominantes. No obstante, la comunicación en grupo se revela como método muy interesante de análisis social.

La madurez cultural aparece como determinante de las competencias interpretativas. La consideración del bajo desarrollo cognitivo que tienen los niños se va superando con la edad. Los nuevos conocimientos adquiridos con el paso del tiempo pueden generar un pensamiento autónomo crítico. Así se razonaba en una las intervenciones de un grupo de Bachillerato con formación en educomunicación: «Yo vi la película siendo niño y no me di cuenta de estas cosas; pero ahora la vas a ver con tu hermana pequeña y dices ‘joder’ (…) Te quieren meter una idea, pero luego, cuando comienzas a pensar de manera autosuficiente, puedes modificarla, y eso es lo que suele ocurrir?».

En los grupos de discusión apareció Disney como megacorporación ilustradora del universo simbólico infantil. Reproducimos una reflexión en un grupo de Bachillerato con formación en educomunicación: «Es una película típica de Disney. Como está producida para niños, pues tiene que responder a la capacidad de entender de estos (…) Utilizan los animales por eso, porque es una película para niños. Si presentaran personas sería muy raro,… contar esas cosas con personas; con los animales es más fácil enganchar a los niños (…) A mi entender está mal que te metan esas ideas desde niño».

La reflexión muestra capacidad crítica sobre la estrategia comunicativa de Disney. Es, probablemente, resultado de la mayor formación audiovisual de este grupo. Para el resto de grupos, Disney es algo «en lo que los padres confían».

3.1.3. Las preocupaciones de padres y madres

Preocupación. Esa es, quizás, la sensación que mejor define el estado que embarga a padres y madres ante estas cuestiones. Se trata de una preocupación unida a un cierto vértigo provocado por el desconocimiento que muchos profesan hacia las nuevas tecnologías. Las opiniones recogidas a través de los grupos de discusión se han visto complementadas con la información derivada de una entrevista en profundidad a una representante del colectivo de padres y madres (AE) persona con décadas de experiencia asociativa y amplia conocedora de la materia objeto de análisis.

Conviene, sin embargo, matizar que dentro de las madres y padres o tutores y tutoras existen diferencias apreciables a la hora de encarar el fenómeno. Tal y como deja entrever la citada AE la brecha digital también está presente en este colectivo: «Hoy en día hay diferencias apreciables entre unos y otros. La actitud hacia las nuevas tecnologías de una persona de 35 años es muy diferente a la de otra de 55. En veinte años las cosas han cambiado muchísimo y eso se percibe cuando hablas con los padres y madres».

En general, los padres y madres aceptan la llegada de las nuevas tecnologías. Creen que son un reflejo de la sociedad y ven en ellas más aspectos positivos (nuevas formas de comunicación, interactividad…) que negativos. No ocultan, sin embargo, una sensación de incertidumbre, sobre todo al verse superados por sus propios hijos e hijas. Todos los y las participantes en los grupos de discusión detectan una tendencia progresiva a la individualización en el consumo de los medios audiovisuales. Frente a ese consumo individual, subrayan los beneficios que comportan el visionado en grupo.

Nostalgia puede ser otra de las claves. Nostalgia por los juegos de calle cooperativos que los padres y madres disfrutaron de niños y por ciertos hábitos que se están perdiendo, como acudir a las bibliotecas. Esa nostalgia va unida también a la esperanza de un futuro mejor. AE insiste en unir perspectiva tecnológica y actitud crítica. La misma protagonista, para concluir la entrevista, nos dejó la siguiente reflexión: «El panorama actual va a cambiar radicalmente en diez años. Los centros educativos van a ser totalmente diferentes. Un 40% del profesorado se va a jubilar. En el entorno familiar más de la mitad de los padres y madres no se van a enterar de casi nada, pero tendrán que ir adaptándose a los nuevos tiempos inducidos por sus hijos e hijas. Los padres y madres mantendrán sus valores y sus ideas pero lo suyo será una adaptación; no un cambio».

3.2. Investigación cuantitativa

Reproducimos a continuación los principales resultados extraídos de la encuesta entre 598 jóvenes vascos de entre 14 y 18 años. Los datos aparecen agrupados en seis grandes apartados: lenguaje audiovisual (máximo 20 puntos), tecnológico (máx.15 puntos), producción (12), recepción crítica (13), valores e ideología (25) y estéticas (15). Así se completó un sistema de graduación de 0 a 100 puntos que nos daba cuenta del grado de alfabetización audiovisual de cada encuestado/a. Reproducimos a continuación los gráficos más representativos.

3.2.1. Lenguaje audiovisual.

Según las respuestas recogidas, comprobamos que los adolescentes y jóvenes escolarizados no estaban muy formados en cuanto a lenguaje audiovisual. Sólo un cuarto de ellos y ellas se acercó al aprobado. Los otros tres cuartos suspendieron de forma notoria (ver gráfico 1).

Gráfico 1: Grado de conocimiento del lenguaje audiovisual. Intervalo: 0-20 puntos

Fuente: Encuesta Aztiker

3.2.2. Tecnología

Es en este apartado donde nuestro equipo encontró la cifra más alta de respuestas acertadas. En general, puede decirse que los jóvenes vascos conocen bien el funcionamiento de los instrumentos audiovisuales. Según los datos, nueve de cada diez fueron capaces, en cuanto receptores, de utilizar eficazmente las tecnologías comunicativas. Son autónomos en ese sentido (ver gráfico 2).

Gráfico 2: Grado de conocimiento y uso de instrumentos audiovisuales.

Intervalo: 0-20 puntos

Fuente: Encuesta Aztiker

3.3.3. Producción

A través de este apartado se pretendía averiguar el grado de conocimiento del proceso de creación de un producto audiovisual por parte de los jóvenes. Las preguntas pretendían averiguar si los encuestados eran capaces de: a) describir las actividades laborales de los profesionales (por ejemplo, de los realizadores, regidores…) que se ocupan de los trabajos de producción de los audiovisuales y b) hacer una relación de las tareas de preparación necesarias para producir un producto.

Según los datos recogidos, puede decirse que el nivel de conocimiento de la producción es muy limitado entre estos jóvenes (ver gráfico 3).

Gráfico 3: Grado de conocimiento sobre el proceso de creación de un producto audiovisual. Intervalo: 0-12 puntos

Fuente: Encuesta Aztiker

A la hora de describir el mundo de la producción, dos variables –la edad y el género– marcaron diferencias estadísticas considerables. Según avanzan en edad, se aprecia un mayor nivel de conocimiento del sistema de producción. En cuanto al género las chicas –también en este apartado– fueron más capaces que los chicos.

3.2.4. Ideología y valores

Los encuestados no fueron especialmente hábiles a la hora de detectar la ideología y los valores subyacentes en los textos audiovisuales sometidos a examen (ver gráfico 5).

Gráfico 4: Capacidad de interpretar correctamente la ideología y valores de los productos audiovisuales. Intervalo: 0-25 puntos

Fuente: Encuesta Aztiker

En la evaluación de las competencias ideológicas comprobamos que los jóvenes utilizaban razonamientos muy simples y débiles a la hora captar y describir el barniz ideológico de un producto audiovisual. Del máximo de 25 puntos que admitía este apartado nadie consiguió siquiera llegar a la mitad.

3.2.5. Balance global

El sumatorio de todas las respuestas ofrece un balance estremecedor. Según esta encuesta, ningún joven escolar vasco estaría hoy en día alfabetizado audiovisualmente, ya que ninguno superó 50 de los 100 puntos posibles. Tan sólo tres de cada diez se acercaron levemente al aprobado sin llegar a superarlo (ver gráfico 7). Son datos que invitan a una seria reflexión.

4. Discusión

Los resultados cosechados en la presente investigación evidencian un notable interés de la comunidad escolar vasca hacia la alfabetización audiovisual. Dicho interés se torna en apremiante necesidad a tenor de los resultados cuantitativos derivados de la encuesta entre los jóvenes.

La investigación muestra un sistema educativo vasco incapaz de alfabetizar audiovisualmente a la población escolar. Los jóvenes desconocen los fundamentos del lenguaje audiovisual. Carecen de discurso estructurado para explicar razonadamente lo que tienen ante sus ojos. Tanto la gramática como la retórica del lenguaje audiovisual les resultan extrañas. En buena lógica, las autoridades educativas deberían tomar nota de los datos aquí recogidos e incluir la educomunicación entre sus prioridades curriculares. Sólo así podrían darse pasos efectivos de cara al objetivo común: la formación de una ciudadanía libre, audiovisualmente educada, capaz de sobrevivir autónomamente en la autodenominada sociedad de la información.

A pesar del indudable interés de las experiencias que en materia de educomunicación se han analizado en la presente investigación, resulta palpable el aislamiento curricular que rodea a las mismas. Los propios docentes implicados se quejan de falta de continuidad y de ausencia de planteamientos globales. El enfoque tecnicista prima sobre el crítico. Reina una fascinación tecnológica que puede incluso llegar a obnubilar y, consecuentemente, a obstaculizar la capacidad de reflexión crítica.

El perfil del profesorado implicado en estas experiencias es multidisciplinar. El dominio de las nuevas tecnologías ha sido determinante, pero cada cual ha llegado al mundo de la educomunicación por vías diferentes. Detectan lagunas en sus propias experiencias y las achacan a la falta de formación reglada en estas materias. Aunque este profesorado muestra mayoritariamente unas dosis de entusiasmo realmente encomiables, también es cierto que en algunos de ellos se palpa un cierto cansancio intelectual, fruto entre otros factores del paso de los años. La motivación del docente resulta clave en esta materia (como en todas). Está ampliamente demostrado que si el educador o educadora es capaz de relacionar los objetivos pedagógicos al contexto social y emocional del alumnado, éste consigue más fácilmente sus metas. En ese sentido, las nuevas tecnologías abren unas posibilidades inmensas, siempre y cuando se adjunten contenidos concretos y objetivos fácilmente identificables por los estudiantes.

Los jóvenes escolarizados en centros vascos donde se han desarrollados experiencias concretas en educomunicación muestran una mejor alfabetización audiovisual. Conviene, sin embargo matizar, que la propia madurez evolutiva de los jóvenes –ligada a su edad– facilita una mayor capacidad interpretativa.

La propia metodología utilizada en la investigación cualitativa –los «focus group» o grupos de discusión– se ha revelado como un instrumento eficaz en la implementación del objetivo a conseguir: la alfabetización audiovisual.

La revolución tecnológica ocupa y preocupa a las madres y padres. Se sienten abrumados y sin criterios ante una realidad que, en muchos casos, les supera. Se sienten incluso incapaces de poner límites al consumo audiovisual de sus hijos e hijas. A pesar de ello, ven más aspectos positivos que negativos en las nuevas tecnologías; reclaman un uso más crítico de dichos instrumentos.

Los resultados de la encuesta aquí recogidos deberían preocupar profundamente a los responsables educativos y a la sociedad en general, máxime si se tiene en cuenta que el grado de alfabetización audiovisual del conjunto de la población no será –presumiblemente– superior al demostrado por los jóvenes. Los registros alcanzados son muy pobres. Muestran una juventud audiovisualmente analfabeta. Disponen de avanzados equipos. Son hábiles en sus destrezas mecánicas, pero desconocen cuestiones elementales relacionadas con la cultura audiovisual, la producción o la detección de los valores éticos y estéticos que subyacen los textos audiovisuales.

Tanto los resultados cualitativos como cuantitativos aquí recogidos vienen a corroborar la hipótesis central que dio pie a la presente investigación: la ausencia de forma reglada de una educación en materia de comunicación provoca serias lagunas en la alfabetización audiovisual del conjunto de la comunidad escolar vasca. Dicha comunidad va a experimentar cambios radicales en breve espacio de tiempo. Dentro de una década, un profesorado sensiblemente más joven que el actual impartirá docencia a una generación mucho más digital que la actual. El perfil de las madres y padres evolucionará igualmente a parámetros más tecnológicos. El equipo investigador entiende que la comunidad escolar vasca tiene ante sí una ocasión de oro, una oportunidad inmejorable para abordar seriamente un debate que afecta a la médula espinal del sistema educativo actual: la alfabetización audiovisual de su ciudadanía.

Apoyos

1 La presente investigación ha sido financiada con fondos de la Universidad del País Vasco y gracias a las ayudas de los Departamentos de Presidencia y Educación del Gobierno Vasco. El trabajo de campo ha sido posible gracias a los servicios de la empresa Aztiker.

2 Además de los autores del presente artículo, también forman parte del equipo investigador el Dr. Petxo Idoiaga Arróspide, catedrático de Comunicación Audiovisual del Departamento del mismo nombre de la Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y de la Comunicación de la Universidad del País Vasco y Amaia Andrieu Sanz, profesora titular del Departamento de Didáctica de la Expresión Musical, Plástica y Corporal de la Escuela Universitaria de Magisterio de Vitoria.

Notas

1 Los grupos de discusión entre los jóvenes se realizaron durante el curso 2008-09. Se escogieron cuatro grupos de entre aquellos centros que sí habían desarrollado algún tipo de estudios audiovisuales. Fueron el instituto Manteo Zubiri de Donostia, los institutos públicos de Eibar y Sopela y el instituto público Mendizabala de Vitoria. Nos interesaba el contraste con el grado de alfabetización audiovisual del alumnado de los centros que no habían cursado este tipo de disciplinas. Por ello se acudió al instituto público Koldo Mitxelena de Vitoria-Gasteiz, a la ikastola privada San Fermín de Pamplona y a los institutos públicos de Bilbao de Txurdinaga Behekoa y Gabriel Aresti.

2 La citada secuencia narra la presentación pública de Simba, el león recién nacido que se convierte en rey de su comunidad.

3 Las personas entrevistadas fueron: MPY doctora en comunicación audiovisual y licenciada en Filología inglesa. Impartió docencia hasta el curso 2008-09 en que se jubiló. Durante su larga trayectoria, la entrevistada llevó a cabo diversas experiencias en alfabetización audiovisual en los institutos públicos de Sopela y Sestao en Bizkaia. La entrevista se celebró el 3 de octubre de 2008; IO, profesor del instituto público Zubiri Manteo de Donostia y responsable del programa europeo «Cine y Juventud» (European Cinema and Young People) dentro del programa «Comenius 3». El encuentro tuvo lugar el 7 de noviembre de 2008 en el propio centro; EL, profesor de euskara y responsable del taller de audiovisuales en el Instituto «Txurdinaga Beheko» en Bilbao. El encuentro se celebró el 16 de febrero de 2009 en el propio centro educativo; TE profesor de la ikastola privada San Nikolas de Getxo y responsable de la experiencia «Globalab» desarrollada en el propio centro. El encuentro se celebró el 12 de marzo de 2009; EMG, AM y AP director y responsables de la sección de medios y del laboratorio respectivamente en la escuela pública Amara Berri de Donostia. Ellos coordinan el «Amara Berri Sistema», un programa pionero en alfabetización audiovisual que trabaja con niños/as de enseñanza primaria. La entrevista se celebró el 3 de abril de 2009 en el propio centro educativo.

4 El trabajo de campo se llevó a cabo entre noviembre del 2009 y febrero del 2010. Los jóvenes respondieron a las preguntas según el modelo lingüístico utilizado en el aula (en euskera, francés o castellano). El cálculo del margen de error (atribuible a muestreos completamente aleatorios) es de +/-4,1% para todo el universo, para un nivel de confianza del 95,5%, siendo p=q%50,0 para la hipótesis más contraria. En total, el cuestionario se ha cumplimentado en 33 centros de Álava, Vizcaya, Guipúzcoa, Navarra y Lapurdi (Labourd), de los que 15 eran privados y 18 públicos. Para construir la muestra, se ha tomado en cuenta el sexo de los alumnos, el nivel de estudios y la experiencia en torno a actividades audiovisuales.

Referencias

Aguaded, J. I. (2009). El Parlamento Europeo apuesta por la alfabetización mediática. Comunicar, 32.

Aguaded, J.I. (1998). Descubriendo la caja mágica. Aprendemos a ver la tele. Huelva: Grupo Comunicar.

Aguaded, J.I. (2000). La educación en medios de comunicación. Huelva: Grupo Comunicar.

Aguaded, J.I. (2009). Miopía en los nuevos planes de formación de maestros en España: ¿docentes analógicos o digitales? Comunicar 33; 7-8.

Ambrós, A. (2006). La educación en comunicación en Cataluña. Comunicar, 27; 205-210

Aparici, R. (1994). Los medios audiovisuales en la educación infantil, la educación primaria y la educación secundaria. Madrid: Uned.

Barranquero, A. (2007). Concepto, instrumentos y desafíos de la edu-comunicación para el cambio social. Comunicar 29; 115-120.

Berger, J. (1972). From Today Art is Dead in Times Educational Supplement, 1972 ko abenduaren 1.

Bonney, B. & Wilson, H. (1983). Australia’s Comercial Media. Melbourne: MacMillan.

Buckingham, D. (2005). Educación en medios. Alfabetización, aprendizaje y cultura contemporánea. Barcelona: Paidós.

Cohen, S. & Young, J. (1973). The Manufacture of News. London: Constable. CORTÉS de CERVANTES, P. (2006). Educación para los medios y las TIC: reflexiones desde América Latina. Comunicar, 26; 89-92.

Duncan, B. et al. (1996). Mass Media and Popular Culture. Toronto, Harcourt-Brace.

Esperon, T.M. (2005). Adolescentes e comunicação: espaços de aprendizagem e comunicação. Comunicar, 24; 133-141.

Ferrés, J. (2006). La competència en comunicació audiovisual: proposta articulada de dimensions i indicadors. Quaderns del CAC, monografikoa L’educació en comunicació audiovisual, 25; 9-17.

Ferrés, J. (2007). La competencia en comunicación audiovisual: dimensiones e indicadores. Comunicar, 29; 100-107.

Fiske, S.T. & Taylor, S.E. (1991). Social Cognition. Nueva Cork: McGraw-Hill.

Fleitas, A.M. & Zamponi, R.S. (2002). Actitud de los jóvenes ante los medios de comunicación. Comunicar, 19; 162-169.

Gainer, S. (2010). Critical Media Literacy in Middle School: Exploring the Politics of Representation. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53 (5); 364-373.

Galtung, J. & Ruge, M. (1965). The Structure of the Foreign News. Journal of International Peace Research, 2, 64-91.

Garcia Matilla, A. & al. (1996). La televisión educativa en España, Madrid: MEC.

Garcia Matilla, A. & al. (2004). (Ed.). Convergencia multimedia y alfabetización digital. Madrid: UCM.

Gerbner, G. (1983). Ferment in the field: 36 Communications Scholars Address Critical Issues and Research Tasks of the Discipline. Philadelphia: Annenberg School Press.

Golay, J.P. (1973). Introduction to the Language of Image and Sound. London: British Film Institute.

Hall, S. & Whankel, P. (1964). The Popular Arts. New York: Pantheon.

Hall, S. (1977). Culture, the Media and Ideological Effect in CURRAN J. & al. (Eds.). Mass Communication and Society. London: Edward Arnold.

Jones, M. (1984). Mass Media Education, Education for Communication and Mass Communication Research. Paris: Unesco.

Kaplun, M. (1998). Una pedagogía de la comunicación. Madrid: De la Torre.

Larson, L.C. (2009). E-Reading and e-Responding: New Tools for the next Generation of Readers. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53 (3); 255-258.

Livingstone, S. & Brake, D.R. (2010). On the Rapid Rise of Social Networking Sites: New Findings and Policy Implications. Children & Society, 24 (1); 75-83.

Lomas, C. (2004). Leer y escribir para entender el mundo. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, 331; 86-90.

Marí-Sáez, V.M. (2006). Jóvenes, tecnologías y el lenguaje de los vínculos. Comunicar, 27; 113-116.

Masterman, L. (1979). Television Studies: Tour approaches. London: British Film Institute.

Masterman, L. (1980). Teaching about Television. Basingstoke Hampshire: MacMillan.

Masterman, L. (1985). Teaching the Media. London: Methuen.

Masterman, L. (1993). La enseñanza de los medios de comunicación. Madrid: De la Torre.

Moreno-Rodríguez, M.D. (2008). Alfabetización digital: el pleno dominio del lápiz y el ratón. Comunicar, 30; 137-146.

Nathanson, A.I. (2002). The Unintended Effects of Parental Mediation of Television on Adolescents. Media Psychology, 4 (3); 207-230.

Nathanson, A.I. (2004). Factual and Evaluative Approaches to Modifying Children's Responses to Violent Television. Journal of Communication, 54 (2); 321-336.

Orozco, G. (1999). La televisión entra al aula. México: Fundación SNTE.

Perceval, J.M. & Tejedor, S. (2008). Los cinco grados de la comunicación en educación. Comunicar, 30; 155-163.

Stein, L. & Prewett, A. (2009). Media Literacy Education in the Social Studies: Teacher Perceptions and Curricular Challenges. Teacher Education Quarterly, 36 (1); 131-148.

Tucho, F. (2006). La educación en comunicación como eje de una educación para la ciudadanía. Comunicar, 26; 83-88.

Wimmer, R. & Dominick, J.R. (1996). La investigación científica de los medios de comunicación. Una introducción a sus métodos. Barcelona: Bosch.

Document information

Published on 28/02/11

Accepted on 28/02/11

Submitted on 28/02/11

Volume 19, Issue 1, 2011

DOI: 10.3916/C36-2011-03-07

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?