Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Resumen

This study analyses the role of communication in social activism from models that surpass the mere emotional reaction, prior belief reinforcement or brand identification. This paper tests the hypothesis that a message focused on the cause (and its results) will motivate a previously sensitized audience depending on their interactions with source favorability. The methodology is based on the design of a bifactor experimental action result study 2 (failure versus success) x 2 valences (favorable versus unfavorable source) with the participation of 297 people who are pro-avoidance of evictions. The results allow us to infer that the messages from sources hostile to the cause that report negative results have the potential to emotionally and behaviorally motivate activists to a greater extent than messages with more positive results from favorable sources. The conclusions point to the dialogue between social injustice frames and pro-cause action emotions as a way to increase social mobilization. The theoretical and empirical implications of these findings are discussed in the present-day context of social media prevalence.

Resumen

Esta investigación analiza el papel de la comunicación en el activismo social desde modelos que superen la mera reacción emocional, el refuerzo de creencias previas o la identificación con la marca. Este estudio pone a prueba la hipótesis de que un mensaje que centre la atención en la causa (en sus resultados) motivará a una audiencia previamente sensibilizada en favor de dicha causa cuando interactúe con la favorabilidad de la fuente. Se ha diseñado un estudio experimental bifactorial 2 resultado de la acción (fracaso versus éxito) x 2 valencia (fuente favorable versus fuente desfavorable) con la participación de 297 personas pro-evitación de desahucios. Los resultados permiten deducir que los mensajes emitidos por fuentes hostiles para la causa que informen de resultados negativos tienen el potencial de motivar afectiva y conductualmente a los activistas en mayor medida que mensajes con resultados más positivos en fuentes favorables. Las conclusiones finales señalan al diálogo entre marcos discursivos de injusticia social y emociones de acción pro-causa como vía para incrementar la movilización social. Se discuten las implicaciones teórico-prácticas de estos resultados en el contexto actual de predominio de redes sociales.

Keywords

Communication, activism, engagement, social change, efficacy, persuasion, social motivation, reception

Palabras clave

Comunicación, activismo, compromiso, cambio social, eficacia, persuasión, motivación social, recepción

Introduction and state of the art

This empirical research analyzes one of the most pressing questions in forums and publications engaged in communication for social change: How can communication aimed at citizen involvement in social transformation be more effective? (Kirk, 2012; Waisbord, 2015). The activism promoted by social media that induces users to click while on their social networks (Fatkin & Lansdown, 2015), or to make a donation (Nos-Aldás & Pinazo, 2013) is insufficient to bring about social change. Communication strategies aimed at motivating active responses to a social cause require formats that focus on the cause and motivate people to defend it. Participation in pro-cause behaviors seems to go no further than activity in open communication spaces, such as the digital (Sampedro & Martínez-Avidad, 2018), or for the audience to listen only to what they want to hear (Hart, Albarracín, Eagly, Brechan, Lindberg, & Merrill, 2009; Nisbet, Hart, Myers, & Ellithorpe, 2013; Stroud, 2007; Webster & Ksiazek, 2012). Willing recipients of the message are not necessarily active even though they may be defenders of the cause. Exposing oneself to messages that fit prior attitudes and avoiding those that challenge their values can lead to a kind of inactive conformity, summed up as, “that’s the way things are”.

Social media facilitate the widespread dissemination of social causes that represent online what social networks do offline (Bakker & de-Vreese, 2011; Boulianne, 2009; Dimitrova, Shedata, Strömbäck, & Nord, 2014). This feature of online communication can enable the messages from these closed self-confirming circles to be broadcast widely and to raise political awareness (Boulianne, 2009; Sampedro & Martínez-Avidad, 2018). In this new context, activating the social commitment of those already converted to the cause but insufficiently active, could depend on where the recipient’s attention lies when receiving the message. What is the best communication strategy for activating this type of audience? People tend to act with greater intensity and commitment when they feel their participation could be useful or necessary —e.g. when the cause is under threat. This research aims to explore aspects of communication that could intensify social motivation towards the cause among recipients who are already sensitized in that direction.

Sensitization towards social justice issues

To be socially sensitized is to feel affected, to judge, to think and act in accordance with social-moral values in a coherent way (Haidt, 2001; 2003). This implies an affective and cognitive rejection response towards the perception of moral breakdown resulting from a social action (Haidt, 2003). This does not necessarily result in immediate action, but rather a greater predisposition towards acting in favor of a social cause that motivates the person. The subsequent moral judgement entails evaluating the appropriateness or inappropriateness of the social act that defends the cause, a judgement based on a cognitive-emotional process that is predisposed towards the action (Haidt, 2007). The judgement arises from a communication scenario that should be able to motivate action and commitment. What aspects of the communication structure can stimulate a motivating social-moral judgment that will better predispose someone to act in favor of the cause?

To keep motivation alive, activists need to be sensitized to content that can rouse them to defend the cause beyond merely sending in a donation or feeling comfortable with the brand (De-Andrés, Nos-Aldás, & García-Matilla, 2016; Nos-Aldás & Pinazo, 2013; Pinazo & Nos-Aldás, 2016; Pinazo, Barros-Loscertales, Peris, Ventura-Campos, & Avila, 2012). Activists who ultimately take up the cause will be those who are motivated to follow up the conclusions of the message in favor of the cause, if these are deemed relevant for the defense of their values. The difficulty with those converted to the cause, is that they probably feel they are already active, and perhaps the message no longer moves them to make an effective commitment to specific actions. In this sense, the arguments’ valence could be particularly relevant for social activism in terms of their capacity to motivate. Content that describes the success of the social action (positive valence) or failure (negative valence) can affect motivation to act in favor of the message in different ways. Activists in favor of social causes will tend to search for messages that validate their position. In this sense, they can expect to receive a call to action through negative or positive valence messages from a favorable outlet. If the cause is not under threat, it is only necessary to remain convinced of the value of such messages; however, the need to defend a cause under threat can motivate action, regardless of the source of this information. The consideration of the social action’s outcome as a persuasive argument has not been widely researched (Reysen & Hackett, 2016; Reysen & Katzarska-Miller, 2013), neither has the interaction between the social action and the source.

When the source is unexpected

In terms of social sensitization, the recipient is the essential element in the communication process, not for their passivity but for their influence on how that communication is framed, given that it is the recipient who will shape the meaning of the message. The recipient can and should attend to the message actively. Studies on selective exposure seem to suggest that the response to a message is conditioned by the extent of the recipient’s engagement with the cause defended, and they essentially relate this exposure to the source of the message (Arceneaux & Johnson, 2015; Briñol, Petty, & Tormala, 2004; Chaffee & Miyo, 1983; Ehrenberg, 2000; Freedman & Sear, 1965).

This research expands the tools demanded by the global social justice community and reinforces the proposals of communication for social change on the transformative, educational and mobilizing effectiveness of communicative strategies that go beyond emotional reaction or identification with the brand.

A source that is confirmatory of the recipient’s prior position, sensitizes them to the cause to a lesser extent, as the message is expected to confirm prior beliefs; such trust shifts focus away from other potentially dissonant information (Briñol & Petty, 2015) although it could polarize the political position (Arceneaux, Johnson, & Cryderman, 2013). Commercial communication uses these information reception preferences to associate social causes to brands in order to boost their image (Becker-Olsen, Cudmore, & Hill, 2006; Pinazo, Peris, Ramos, & Brotons, 2013); this communication strategy does not boost motivation for the cause itself.

In short, evidence shows that the motivation to attend to a message favoring a social cause increases in the presence of a consonant source and can burnish the image of the neutral source (commercial brand). But what happens if someone is exposed to a message that is consistent with his or her social sensibility but comes from a dissonant source? We have found no studies that analyze the effect of a message from a disruptive source on sensitization to a social cause, expressed as an active response (cognitive, affective or behavioral) in favor of social causes.

Valence of the argument and the source

Possessing attitudes is not enough to influence behavior. People need to believe that their attitudes are correct and feel comfortable with them (Briñol & Petty, 2015). For activists, receiving information on a positive outcome about their advocated social action, can strongly reinforce their position. However, a negative outcome could be seen as a weak argument for the efficacy of the social action. Information containing a positive outcome of the social action can arouse good feelings about their position, thus requiring no further reinforcement. Such information could reduce motivation for action while the weak argument could have the opposite effect.

The credibility of the source interacts with the effect of the argument’s valence. Related research on the area shows that when the message contains strong arguments, the highly credible source fosters prior attitudes more than when the source is barely credible; however, this effect is reversed when the arguments presented are weak (Briñol & Petty, 2015). If the argument is weak, it could contradict what the reader expects to receive and undermine confirmation that the action is effective. If the source offers arguments consistent with the person’s values, this person will be more inclined to agree with the message, for they will reason that “if the message fits with me and my values, it must be good” (Briñol & Petty, 2015). If one receives information about the effectiveness of the action, it can then be interpreted that there is no need for further action. A failure of the pro-cause action could rouse an individual to defend it, but if the source is pro-attitude, it could diminish their motivation, as it could be interpreted that the reason why they are reporting a setback is not because it is real but because they want to rouse people to action. Yet a source that is barely credible in its coverage in favor of the cause could boost activist motivation to defend it, as the action could end in failure, perhaps due to the fact that the source is controlled by media hostile to the cause. No research exists dealing directly with this combination of factors in recipients differentiated by the extent of their partiality to a social cause. The communication model presented by Pinazo and Nos-Aldás (2016) suggests that motivation in favor of a cause is modulated by a communication strategy associated to the context in which the message is presented. A context that is negative to the cause in a pro-attitude medium can arouse motivation favorable to the medium, not to the cause.

The results of this study show that positive or negative messages focusing on success or failure (in terms of social psychology and, the message’s positive or negative valence) are important for keeping activists in protest mode.

The aim of this work is to assess whether the context of interaction in political activism, as well as the source and valence of the result of the action influence pro-cause motivation. Specifically, we defend the hypothesis that presenting a group of pro-cause activists with a negative valence message from a source hostile to their attitudes will motivate them more in favor of the cause than presenting them with a negative valence message from a pro-attitude source. Likewise, positive valence messages will have no differentiated effects on pro-cause motivation regardless of the attitude towards the cause of the medium that publishes it.

Method

Sample

The study participants were individuals who fulfilled the following criteria: 1) to be committed to social causes; 2) to have participated in pro-avoidance of evictions mobilizations. Initially, 400 booklets were distributed, of which 24 were discarded for not having been entirely completed. A further 79 people were eliminated from the sample for not having taken part in any initiative demanding justice for those threatened by eviction (demonstrations, strikes, petition drives, filing complaints, use of social media or other types of action aimed at defending the cause of preventing evictions). This was the final distribution by conditions: failure/favorable source (70 individuals), failure/unfavorable source (83), success/favorable source (81) and success/unfavorable source (63). The final sample consisted of 297 individuals. Men accounted for 37.4% of the sample (N=111), women 62.6% (N=186). The age range was 18 to 70 (M=34.23; SD=13.91). Level of education was classified as those without a college degree, 56.2% (N=167), and those with a college degree, 43.8% (N=130). Of the total sample, 34.7% (N=103) held wage-earning employment while 65.3% (N=194) were unemployed. Monthly income was measured on a scale of 1 to 8: no income (1), less than or equal to 300€ (2), 301€ to 600€ (3), 601€ to 1,000€ (4), 1,001€ to 2,000€ (5), 2,001€ to 3,000€ (6), 3,001€ to 5,000€ (7), more than 5,000€ (8). The mean monthly income of those surveyed was between 301€ and 600€.

Study design and procedure

We performed a bifactor experimental action result study 2 (negative versus positive) x 2 sources (favorable versus unfavorable). A fictitious eviction case in the format of a news item was created then reviewed by a panel of experts in journalism, advertising, sociology, semiotics and social psychology. With the body of the message approved, the experimental conditions for the study were created.

The booklets containing the conditions of the experiment were distributed personally by research assistants to those individuals selected to take part in the survey. First, the participants were asked to provide demographic data (gender, age, education, employment, income) then quantify the extent of their participation in demanding social justice for those affected by evictions. Later, on a separate sheet, each participant read the single news item on an eviction case drafted according to one of the four experimental conditions; on the next page, the participants responded to a series of questions related to the news item.

Dependent variables

Moral motivation (MM): the same items as in Pinazo and Nos-Aldás (2016) were used to measure moral judgement or the extent to which the action in the news report transgresses norms of social or ethical justice. The respondents had to answer two questions: “do you consider what has happened to this family socially unjust?”, and, “do you consider it immoral to do nothing to prevent this situation?” Both items had a high internal consistency (α=.798; M=7.47; SD=2.06).

Affective motivation (AM): a version of the items selected from the PANAS-X scale (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) were used, but instead of applying an approach to the effect in two dimensions, one negative and one positive, we opted for items in line with the study objective to assess that affective state (Lambert, Eadeh, Peak, Scherer, Schott, & Slochower, 2014). Two affective motivator states were considered in relation to social activism: 1) the affective state that drives the activist to action; 2) the affective state associated to the rejection of the situation. Items were selected that better represented these states, based on PANAS. For affective motivation for action (AMA), the states selected were “Energetic”, “Enthusiastic”, “Inspired” and “Active” (α=.800; M=4.54; SD=1.65), and to represent affective motivation for rejection (AMR) the states chosen were “Hostile”, “Irritable”, “Anxious” and “Angry” (α=.805; M=5.07; SD=1.83).

Pro-conduct motivation (PcM): this assessed their predisposition to collaborate in just causes, and consisted of a set of three behaviors related to social activism: “collaborate in protest actions”, “invest my money in ethical banks that do not pay interest and invest only in companies that favor just causes”, “report companies that attempt to deceive customers, or act unjustly to make a profit”. On a scale of 1 (I totally disagree) to 9 (I totally agree), participants were questioned on an eviction demanded by a bank: “what would you be willing to do to participate in a solution to this problem?” Given that the internal consistency of the three items is high, α=.711, we created an aggregate variable that assessed predisposition to act in favor of social causes (M=6.73; SD=1.83).

Control variable

Message credibility: the control variable to assess whether the recipient has understood the message. The effect of a message depends on the recipient’s motivation to process it, according to certain models of persuasion, especially the one relating to elaboration likelihood (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). As a credibility factor, belief in news veracity was evaluated, based on two questions: 1) “this news item has been manipulated”; 2) “this news item is false” (α=.565). The aggregate measure of news credibility was M=3.97 (SD=2.44). A high score indicates that the participants do not trust the news item.

Results

The SPSS v24 statistical software package was used to analyze the data. Before studying the effect of the experimental conditions on the dependent variables, several analyses were run to evaluate possible bias in the demographic variables and in the motivation to elaborate the message. The results showed that the sample was evenly distributed according to the various conditions considered for the experiment: the gender proportion in each experimental condition is similar (χ2=1.62; p=.656), as is the distribution for education level (χ2=0.99; p=.805) and for being in or out of work (χ2=0.99; p=.092). ANOVA for age (F=0.57; p=.634) and income (F=1.72; p=.163) indicates that these variables are also evenly distributed across the experimental conditions.

A univariate analysis of variance (UNIANOVA) was conducted to assess whether the recipients reacted in different ways to the message, in each of the conditions, perceiving it to be either true or false; results showed that different reactions did occur (F=5.513; p=.001; η2=.053). The Tukey post-hoc means comparison test was used to reveal differences between various pairs. There were differences (p=.027) between news of success versus unfavorable source (M=4.62; SD=2.19) in relation to news of failure versus unfavorable source (M=3.50; SD=2.40). There were also differences (p=.018) between news of success versus favorable source (M=4.49; SD=2.34) in relation to news of failure versus favorable source (M=3.35; SD=2.40). There were differences (p=.013) between news of success versus unfavorable source (M=4.62; SD=2.66) in relation to news of failure versus favorable source (M=3.35; SD=2.40). Finally, there were differences (p=.040) between news of failure versus unfavorable source (M=3.50; SD=2.19) in relation to news of success versus favorable source (M=4.49; SD=2.34). These paired differences indicate that the recipients regarded news publicizing the success of the cause as less credible, which shows a predisposition towards an expectation of failure. There was also a tendency of disbelief towards news from the unfavorable source. These differences are expected in people who are favorable to the social cause, demonstrating that the participants had read and understood the cases involved. With confidence in the participants’ attention to the study, we assessed the effect of the cases on recipients’ motivation towards the social cause.

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to compare the effect of the interaction of the Result (positive or negative) of the social action versus Source on motivational results (Moral Motivation, Affective Motivation and Motivation for Action). Some indicators showed that the MANOVA statistical assumptions were fulfilled. Box’s M test =69.128, p<.000 showed that the homoscedasticity of the covariance matrices was not in question; consequently, the interpretation of the multivariate test could be made with Pillai’s Trace (Tabachnick, Fidell, & Ullman, 2007). Levene’s test for equality of variances is not significant for the Pro-Conduct Motivation and Affective Motivation variables; therefore, the Tukey test was applied to these variables during post-hoc analysis. On the other hand, Levene’s test was significant, which indicated a lack of homogeneity in the sample variances, in the Moral Motivation and Motivation to Reject variables. Thus, Dunnett’s C test was used in the post-hoc analysis of these variables.

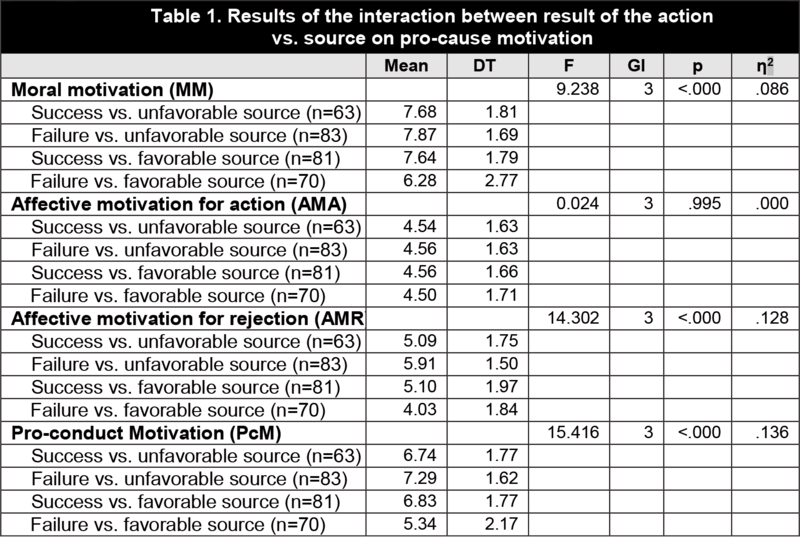

The MANOVA results for motivation revealed a significant principal effect, the Pillai Trace =.269 (F=7.191; =.000), with a small sample of the effect (η2=.090). The univariate test showed significant effects in the direction expected for the effects of motivation (Table 1).

|

|

To locate the differences between certain pairs in the interaction model set, we performed the Tukey post-hoc comparison test, which provided the following results: In AMA, the comparison between the four groups did not display any significant differences; in PcM, the pairs comparison in the experimental conditions revealed significant differences between the condition of failure versus unfavorable source with failure versus favorable source (p<.000), and the condition of success versus unfavorable source with failure versus favorable source (p<.000). The means comparison (Table 1) suggests that the recipients were more motivated to act when the news of failure came from an unfavorable source.

Dunnett’s C post-hoc test for MM indicated that there are considerable differences in the means when comparing the following: groups of success versus unfavorable source with failure versus favorable source (p<.000); groups of failure versus unfavorable source with failure versus favorable source (p<.000); and groups of success versus favorable source with failure versus favorable source (p<.000). These differences imply that the recipients felt more morally motivated when the news came from an unfavorable source or from a favorable source reporting on the success of the action.

The Dunnett C test for AMR showed significant differences in the means when comparing the following: groups of success versus unfavorable source with failure versus favorable source (p=.002); groups of failure versus unfavorable source with failure versus favorable source (p=.000); and groups of success versus favorable source with failure versus favorable source (p=.001). The means comparison showed that the motivation to reject the news occurs when news of failure appear in a hostile medium, or in a consonant medium if the news report a success.

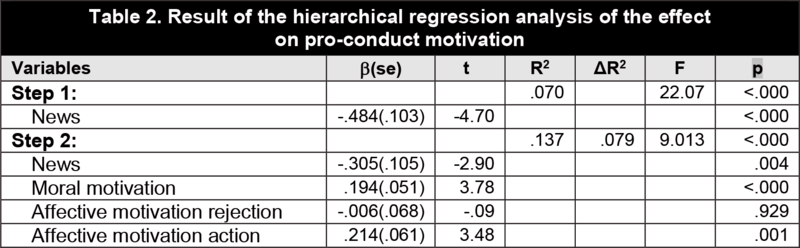

The results indicate that the reception of a news item that displays a negative valence in the social action presented by an unfavorable source generates greater affective rejection towards the failure of the cause, and better predisposes the activist to act in favor of the social causes. However, it has no effect on positive affective motivations. To assess whether PcM is a direct effect of the source versus valence of the result interaction, or whether intervening variables exist, we performed a hierarchical regression analysis (Table 2).

|

|

One of the objectives of this analysis was to assess whether the effect on pro-conduct motivation is direct, mediated by other variables or modulated by them. The research procedure most frequently used to test mediation was developed by Kenny (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Hayes, 2009) and consists of four stages. First, the causal independent predictor variable, in this case the news, must have a direct effect on the dependent variable. This is verified by observing the effect in MANOVA (Table 1) and in the first regression model obtained (Table 2). Secondly, the independent variable must have an effect on the possible mediator variables. This second supposition is only fulfilled in MM and AMR in our study (Table 1). Thirdly, these three variables (News, MM and AMR) should have a significant direct effect on the dependent variable PcM, which occurs in Step 2 of the regression for the “moral motivation” variable (Table 2). Finally, the effect of the mediator variable on the dependent variable should annul the direct effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, which does not occur since the effect of the news continues to be significant in Step 2. Therefore, mediation is not observed. The moderation hypothesis is confirmed if the increase in the proportion of variability due to the interaction is significant. Table 2 shows that this criterion is satisfied in Step 2.

The results of the hierarchical regression analysis show that the effect of the news on motivation to act is biased due to the presence of at least two factors: MM and AMA. Analyzing the conditions in order to assess the type of participation of these variables, we observe that they do not comply with the mediation criteria but do so with the modulation criteria, so, we conclude that MM and AMA are modulator variables on the effect of the news on the motivation for action.

Discussion and conclusions

Participation in the defense of social causes not only occurs within a favorable context, such as the digital environment (Sampedro & Martínez-Avidad, 2018), the cause itself must motivate the audience. In this study, we have tested the hypothesis that a message focusing attention on the cause (as a result of a successful outcome for the cause) will motivate the audience when it interacts with the favorability of the source. We have analyzed the effect on the pro-cause response of the interaction between source versus result of the pro-cause action on an audience previously sensitized by the social cause defended.

All judgement passed on a social object is determined by a cognitive and affective process (Oskamp, 1991). When assessing the efficacy of the communication, consideration is usually placed upon the utilitarian responses that are normally considered, such as the quantity and frequency of donations (Pinazo & Nos-Aldás, 2016) or the likelihood that a message is shared on social media (Brady, Wills, Burkart, Jost, & van-Bavel, 2018; Hansen, Arvidsson, Nielsen, Colleoni, & Etter, 2011). In both cases, it is brand penetration or the communication piece that is evaluated, rather than the content or sensitization to the cause itself. In this study, we have focused on sensitization in the pro-cause response and the conditions in which it can be identified.

The results show that reporting on the failure of the cause better sensitizes a pro-cause audience. This sensitization means there is greater affective engagement with the rejection of the cause’s failure, and a greater predisposition to act in order to reverse this setback. This perception of failure is accentuated when reported in a hostile medium, so that the communication of failure versus hostile medium interaction is a source of affective and intentional pro-cause sensitization that is more effective than its reporting in sympathetic media and the communication of the cause’s successes. This effect is modulated by the positive moral and affective motivation of the audience that reinforces this effect. Moral motivation and affective motivation for action modulate the effect of the news on pro-cause motivation. That is, the predisposition to act is in consonance with the reception of news of failure in a hostile medium. But this effect increases or decreases according to the effect of the news on moral motivation and the affective motivation for action. The sharper the perception of social injustice as revealed by the news and the greater the arousal of the emotions to act, the more likely the person will be to act in favor of the cause.

The results show that the message’s positive or negative valence is relevant for keeping activists in protest mode. This fits with research that emphasizes the efficacy of designing communication strategies that go beyond mere emotional reaction or brand identification (Pinazo & Nos-Aldás, 2016). The results of this work show that at least one of the reasons why social media could boost citizen engagement and commitment (Boulianne, 2009; Dimitrova, Shehata, Strömbäck, & Nord, 2014; Norris, 2001; Papacharissi, 2002) is by coaxing activists out of their comfort zones. The potential of the media to access sources of information that challenge recipients’ convictions could be one way of reactivating their efforts in defense of their causes.

The results of this work broaden the concept of the efficacy of communication for social change, from its ability to mobilize and educate (Obregón & Tufte, 2017; Pinazo & Nos-Aldás, 2016; Seguí-Cosme & Nos-Aldás, 2017).

Study limitations

Regarding the theoretical contributions of the results, one key limitation is the absence of an analysis comparing the pro-cause sample with an anti-cause sample. A study design that identified this type of audience and analyzed their reactions would be an important empirical and theoretical contribution to the knowledge of how to disseminate social causes.

Given that it is an experiment performed outside the laboratory, the results could have been affected by the diminished internal control that such conditions imply. Although the participants’ attention while reading the message was controlled in part, we cannot guarantee that rejection of the source intervened more strongly than the need to carefully evaluate the meaning of the message. Control conditions, therefore, need to be bolstered in future studies.

Another issue that affects the relevance of the results is whether they can be generalized to include other communication frames. Replicating the study in different communication contexts would provide additional evidence as to how messages against the social cause in hostile media can motivate the pro-cause audience. The study needs to be repeated in samples with population and/or cultural variants.

See Annex for the experimental conditions applied to the design of the news item, at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9852719.v1.

Notes

- See Annex for the experimental conditions applied to the design of the news item, at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9852719.v1.

References

- ArceneauxK, JohnsonM, . 2015.does media choice affect hostile media perceptions? Evidence from participant preference experiments&author=Arceneaux&publication_year= How does media choice affect hostile media perceptions? Evidence from participant preference experiments.Journal of Experimental Political Science 2(1):12-25

- ArceneauxK, JohnsonM, CrydermanJ, . 2013.persuasion, and the conditioning value of selective exposure: Like minds may unite and divide but they mostly tune out&author=Arceneaux&publication_year= Communication, persuasion, and the conditioning value of selective exposure: Like minds may unite and divide but they mostly tune out.Political Communication 30:2013-231

- BakkerT P, De-VreeseC H, . 2011.news for the future? Young people, Internet use, and political participation&author=Bakker&publication_year= Good news for the future? Young people, Internet use, and political participation.Communication Research 38(4):451-470

- BaronR M, KennyD A, . 1986.moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations&author=Baron&publication_year= The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51(6):1173-1182

- Becker-OlsenK L, CudmoreB A, HillR P, . 2006.impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior&author=Becker-Olsen&publication_year= The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior.Journal of Business Research 59(1):46-53

- BoulianneS, . 2009.Internet use affect engagement? A meta-analysis of research&author=Boulianne&publication_year= Does Internet use affect engagement? A meta-analysis of research.Political Communication 26(2):193-211

- BradyW J, WillsJ A, BurkartD, JostJ T, Van-BavelJ J, . 2018.ideological asymmetry in the diffusion of moralized content on social media among political leaders&author=Brady&publication_year= An ideological asymmetry in the diffusion of moralized content on social media among political leaders.Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 49(2):192-205

- BriñolP, PettyR E, . 2015.and validation processes: Implications form media attitudes change&author=Briñol&publication_year= Elaboration and validation processes: Implications form media attitudes change.Media Psychology 18(3):267-291

- BriñolP, PettyR E, TormalaZ L, . 2004.of cognitive responses to advertisements&author=Briñol&publication_year= Self-validation of cognitive responses to advertisements.Journal of Consumer Research 30(4):559-573

- ChaffeeS, MiyoY, . 1983.exposure and the reinforcement hypothesis: An intergenerational panel study of the 1980 presidential campaign&author=Chaffee&publication_year= Selective exposure and the reinforcement hypothesis: An intergenerational panel study of the 1980 presidential campaign.Communication Research 10(1):3-36

- De-AndrésS, Nos-AldásE, García-MatillaA, . 2016.transformative image: The power of a photograph for social change: The death of Aylan. [La imagen transformadora. El poder de cambio social de una fotografía: la muerte de Aylan&author=De-Andrés&publication_year= The transformative image: The power of a photograph for social change: The death of Aylan. [La imagen transformadora. El poder de cambio social de una fotografía: la muerte de Aylan.Comunicar 24:29-37

- DimitrovaD V, ShehataA, StrömbäckJ, NordL W, . 2014.effects of digital media on political knowledge and participation in election campaigns: Evidence from panel data&author=Dimitrova&publication_year= The effects of digital media on political knowledge and participation in election campaigns: Evidence from panel data.Communication Research 41(1):95-118

- EhrenbergA S, . 2000.advertising and the consumer&author=Ehrenberg&publication_year= Repetitive advertising and the consumer.Journal of Advertising Research 40(6):39-48

- FatkinJ M, LansdownT C, . 2015.media in action&author=Fatkin&publication_year= Prosocial media in action.Computers in Human Behavior 48:581-586

- FreedmanJ L, SearsD O, . 1965.exposure&author=Freedman&publication_year= Selective exposure.Advances in experimental social psychology.

- HaidtT J, . 2007.new synthesis in moral psychology&author=Haidt&publication_year= The new synthesis in moral psychology.Science 316:998-1002

- HaidtT J, . 2003.The moral emotions.Handbook of affective sciences.

- HaidtT J, . 2001.emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment&author=Haidt&publication_year= The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment.Psychological Review 108(4):814-834

- HansenL K, ArvidssonA, NielsenF Å, ColleoniE, EtterM, . 2011.friends, bad news-affect and virality in Twitter&author=Hansen&publication_year= Good friends, bad news-affect and virality in Twitter.Future information technology. Communications in computer and information science.

- HartW, AlbarracínD, EaglyA H, BrechanI, LindbergM J, MerrillL, . 2009.validated versus being correct: A meta-analysis of selective exposure to information&author=Hart&publication_year= Feeling validated versus being correct: A meta-analysis of selective exposure to information.Psychological Bulletin 135(4):555-588

- HayesA F, . 2009.Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium&author=Hayes&publication_year= Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium.Communication Monographs 76(4):408-420

- KirkM, . 2012.charity: Helping NGOs lead a transformative new public discourse on global poverty and social justice&author=Kirk&publication_year= Beyond charity: Helping NGOs lead a transformative new public discourse on global poverty and social justice.Ethics & International Affairs 26(2):245-263

- LambertA J, EadehF R, PeakS A, SchererL D, SchottJ P, SlochowerJ M, . 2014.a greater understanding of the emotional dynamics of the mortality salience manipulation: Revisiting the ‘affect-free’ claim of terror management research&author=Lambert&publication_year= Toward a greater understanding of the emotional dynamics of the mortality salience manipulation: Revisiting the ‘affect-free’ claim of terror management research.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 106(5):655

- NisbetE C, HartP S, MyersT, EllithorpeM, . 2013.change in competitive framing environments? Open-/closed-mindedness, framing effects, and climate change&author=Nisbet&publication_year= Attitude change in competitive framing environments? Open-/closed-mindedness, framing effects, and climate change.Journal of Communication 63(4):766-785

- NorrisP, . 2001.divide: Civic engagement, information poverty, and the Internet worldwide&author=&publication_year= Digital divide: Civic engagement, information poverty, and the Internet worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nos-AldásE, PinazoD, . 2013.and engagement for social justice&author=Nos-Aldás&publication_year= Communication and engagement for social justice.Peace Review 25(3):343-348

- ObregónR, TufteT, . 2017.social movements, and collective action: Toward a new research agenda in communication for development and social change&author=Obregón&publication_year= Communication, social movements, and collective action: Toward a new research agenda in communication for development and social change.Journal of Communication 67(5):635-645

- OskampS, . 1991. , ed. and opinions&author=&publication_year= Attitudes and opinions.Englewood Cliffs, NJ, US: Prentice-Hall.

- PapacharissiZ, . 2002.virtual sphere: The Internet as a public sphere&author=Papacharissi&publication_year= The virtual sphere: The Internet as a public sphere.New Media & Society 4(1):9-27

- PettyR E, CacioppoJ T, . 1986.elaboration likelihood model of persuasion&author=Petty&publication_year= The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion.Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 19:123-205

- PinazoD, Nos-AldásE, . 2016.moral sensitivity through protest scenarios in International NGDO’s communication&author=Pinazo&publication_year= Developing moral sensitivity through protest scenarios in International NGDO’s communication.Communication Research 43(1):25-48

- PinazoD, PerisR, RamosA, BrotonsJ, . 2013.effects of the perceived image of non-governmental organisations&author=Pinazo&publication_year= Motivational effects of the perceived image of non-governmental organisations.Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 23(5):420-434

- PinazoD, Barros-LoscertalesA, PerisR, Ventura-CamposN, AvilaC, . 2012.role of protest scenario in the neural response to the supportive communication&author=Pinazo&publication_year= The role of protest scenario in the neural response to the supportive communication.International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 17(3):263-274

- ReysenS, HackettJ, . 2017.as a pathway to global citizenship&author=Reysen&publication_year= Activism as a pathway to global citizenship.The Social Science Journal 54(2):132-138

- ReysenS, Katzarska-MillerI, . 2013.model of global citizenship: Antecedents and outcomes&author=Reysen&publication_year= A model of global citizenship: Antecedents and outcomes.International Journal of Psychology 48(5):858-870

- SampedroV, Martinez-AvidadM, . 2018.The digital public sphere: An alternative and counterhegemonic space? The case of Spain.International Journal of Communication 12:23-44

- Seguí-CosmeS, Nos-AldásE, . 2017.epistemológicas y metodológicas para definir indicadores de eficacia cultural en la comunicación del cambio social&author=Seguí-Cosme&publication_year= Bases epistemológicas y metodológicas para definir indicadores de eficacia cultural en la comunicación del cambio social.Commons 6(2):10-33

- StroudN J, . 2007.use and political predispositions: Revisiting the concept of selective exposure&author=Stroud&publication_year= Media use and political predispositions: Revisiting the concept of selective exposure.Political Behavior 30:341-366

- TabachnickB G, FidellL S, UllmanJ B, . 2007. , ed. multivariate statistics&author=&publication_year= Using multivariate statistics.Boston, MA: Pearso. 5

- WaisbordS, . 2015.challenges for communication and global social change&author=Waisbord&publication_year= Three challenges for communication and global social change.Communication Theory 25:144-165

- WatsonD, ClarkL A, TellegenA, . 1988.and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales&author=Watson&publication_year= Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54(6):1063-1070

- WebsterJ G, KsiazekT B, . 2012.dynamics of audience fragmentation: Public attention in an age of digital media&author=Webster&publication_year= The dynamics of audience fragmentation: Public attention in an age of digital media.Journal of Communication 62(1):39-56

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Esta investigación analiza el papel de la comunicación en el activismo social desde modelos que superen la mera reacción emocional, el refuerzo de creencias previas o la identificación con la marca. Este estudio pone a prueba la hipótesis de que un mensaje que centre la atención en la causa (en sus resultados) motivará a una audiencia previamente sensibilizada en favor de dicha causa cuando interactúe con la favorabilidad de la fuente. Se ha diseñado un estudio experimental bifactorial 2 resultado de la acción (fracaso versus éxito) x 2 valencia (fuente favorable versus fuente desfavorable) con la participación de 297 personas pro-evitación de desahucios. Los resultados permiten deducir que los mensajes emitidos por fuentes hostiles para la causa que informen de resultados negativos tienen el potencial de motivar afectiva y conductualmente a los activistas en mayor medida que mensajes con resultados más positivos en fuentes favorables. Las conclusiones finales señalan al diálogo entre marcos discursivos de injusticia social y emociones de acción pro-causa como vía para incrementar la movilización social. Se discuten las implicaciones teórico-prácticas de estos resultados en el contexto actual de predominio de redes sociales.

ABSTRACT

This study analyses the role of communication in social activism from models that surpass the mere emotional reaction, prior belief reinforcement or brand identification. This paper tests the hypothesis that a message focused on the cause (and its results) will motivate a previously sensitized audience depending on their interactions with source favorability. The methodology is based on the design of a bifactor experimental action result study 2 (failure versus success) x 2 valences (favorable versus unfavorable source) with the participation of 297 people who are pro-avoidance of evictions. The results allow us to infer that the messages from sources hostile to the cause that report negative results have the potential to emotionally and behaviorally motivate activists to a greater extent than messages with more positive results from favorable sources. The conclusions point to the dialogue between social injustice frames and pro-cause action emotions as a way to increase social mobilization. The theoretical and empirical implications of these findings are discussed in the present-day context of social media prevalence.

Palabras clave

Comunicación, activismo, compromiso, cambio social, eficacia, persuasión, motivación social, recepción

Keywords

Communication, activism, engagement, social change, efficacy, persuasion, social motivation, reception

Introducción y estado de la cuestión

La investigación empírica que sigue aborda uno de los interrogantes abiertos en los foros y publicaciones sobre comunicación para el cambio social: ¿cómo podemos incrementar la eficacia de la comunicación para la implicación ciudadana en la transformación social? (Kirk, 2012; Waisbord, 2015). El activismo promovido por las redes sociales incitando al «clic» (Fatkin & Lansdown, 2015) o a la donación (Nos-Aldás & Pinazo, 2013) puede resultar inefectivo para el cambio social. Las estrategias comunicativas orientadas a motivar respuestas activas hacia la causa social requieren de formatos de comunicación que pongan la atención en la causa, y motiven a las personas en su defensa. La participación en comportamientos pro-causa parece ceñirse a la posibilidad de espacios de comunicación abiertos, como el digital (Sampedro & Martínez-Avidad, 2018), o a la tendencia de la audiencia a escuchar solo lo que quiere escuchar (Hart, Albarracín, Eagly, Brechan, Lindberg, & Merrill, 2009; Nisbet, Hart, Myers, & Ellithorpe, 2013; Stroud, 2007; Webster & Ksiazek, 2012). Los receptores afines al mensaje no siempre están activos, aunque defiendan la causa. Exponerse a los mensajes más afines a las actitudes previas y evitar los que contrarían sus valores puede generar un cierto conformismo inactivo, del tipo «así son las cosas».

Los «social media» facilitan la amplificación de la difusión de las causas sociales representando online las redes sociales offline (Bakker & de-Vreese, 2011; Boulianne, 2009; Dimitrova, Shedata, Strömbäck, & Nord, 2014). Esta característica podría sacar los mensajes de sus círculos cerrados autoconfirmatorios e incrementar la conciencia política (Boulianne, 2009; Sampedro & Martínez-Avidad, 2018). En este nuevo contexto, activar el compromiso social de receptores convencidos, pero no suficientemente activos, podría depender de dónde se sitúe la atención del receptor al recibir el mensaje. ¿Cuál sería la estrategia comunicativa más apropiada para activar a esta audiencia? La gente suele actuar con más intensidad y compromiso cuando sienten que su participación es útil o necesaria, como cuando la causa está en riesgo. Este trabajo está orientado a explorar aspectos de la estructura comunicativa que puedan intensificar la motivación social por la causa entre los receptores previamente sensibilizados.

Sensibilización hacia las causas de justicia social

La sensibilización social es la capacidad para sentirse afectado, juzgar, pensar y actuar conforme a valores socio-morales de un modo coherente (Haidt, 2001; 2003). Implica una respuesta cognitivo-afectiva de rechazo ante la percepción de la ruptura moral de una acción social (Haidt, 2003). No conlleva una acción inmediata, aunque sí una mayor predisposición a actuar en favor de la causa social que motiva. El juicio moral subsecuente valora lo correcto o incorrecto del acto social que defiende la causa, un juicio basado en un proceso cognitivo-emocional que predispone a la acción (Haidt, 2007). El juicio se realiza ante un escenario comunicativo que debe ser capaz de motivar a la acción y al compromiso. ¿Qué aspectos de la estructura comunicativa pueden estimular un juicio socio-moral motivador que predisponga mejor a actuar en favor de la causa?

Para mantener viva la motivación se necesita sensibilizar sobre los contenidos capaces de activar la defensa de la causa, más allá de la acción de realizar un donativo, o de sentirse comprometido con la marca (De-Andrés, Nos-Aldás, & García-Matilla, 2016; Nos-Aldás & Pinazo, 2013; Pinazo & Nos-Aldás, 2016; Pinazo, Barros-Loscertales, Peris, Ventura-Campos, & Avila, 2012). Los activistas por la causa serán receptores motivados a seguir las conclusiones del mensaje en favor de la causa si estas son relevantes para la defensa de sus valores. La dificultad con los ya convencidos es que probablemente sientan que ya están actuando, y el mensaje quizás no estimule su motivación hacia el compromiso efectivo o la acción específica. En este sentido, para el activismo social, la valencia de los argumentos puede ser especialmente relevante en su capacidad motivadora. Un contenido que indique éxito en la acción social (valencia positiva) o un argumento que indique fracaso (valencia negativa), pueden tener efectos distintos en la motivación por la acción favorable al mensaje. El receptor favorable a las causas sociales tenderá a buscar mensajes que validen su posición. Un activista puede esperar de un emisor favorable una llamada a la acción anunciando mensajes con valencia negativa, o el mantenimiento de la misma con mensajes de valencia positiva. Si la causa no está amenazada, tan solo es necesario mantenerse convencido de su valor. Por otra parte, la necesidad de trabajar por una causa amenazada puede impulsar a la acción, sin importar la fuente de la que se obtenga esa información. Considerar como argumento persuasivo el resultado de la acción social es un tema poco presente en la investigación (Reysen & Hackett, 2016; Reysen & Katzarska-Miller, 2013), como tampoco es frecuente analizar su interacción con la fuente.

Cuando el emisor no es el esperado

Desde la perspectiva de la sensibilización social, el receptor es esencial en la comunicación, no por su pasividad, sino por su influencia en el modo en que se comunica, ya que es el que construye el significado del mensaje. El receptor puede y debe atender al mensaje de un modo activo. Los estudios sobre exposición selectiva parecen sugerir que la respuesta a los mensajes emitidos está condicionada por el grado de implicación hacia la causa defendida, y orientan la exposición a la fuente del mensaje esencialmente (Arceneaux & Johnson, 2015; Briñol, Petty, & Tormala, 2004; Chaffee & Miyo, 1983; Ehrenberg, 2000; Freedman & Sear, 1965).

Esta investigación amplía las herramientas que reclama el tejido asociativo de la justicia social global y refuerza las propuestas de la comunicación para el cambio social sobre la eficacia transformativa, educativa y movilizadora de plantear estrategias comunicativas que vayan más allá de la reacción emocional o de identificación con la marca.

La fuente confirmadora de la posición previa sensibiliza en menor intensidad sobre la causa debido a que incita a esperar confirmar las creencias previas, confianza que distrae de la posibilidad de otro tipo de información disonante (Briñol & Petty, 2015), aunque puede polarizar la posición política (Arceneaux, Johnson, & Cryderman, 2013). La comunicación comercial utiliza estas preferencias de recepción de información para asociar causas sociales a marcas con el objetivo de favorecer su imagen (Becker-Olsen, Cudmore, & Hill, 2006 ; Pinazo, Peris, Ramos, & Brotons, 2013). No es una estrategia comunicativa que ayude a mejorar la motivación por la propia causa.

En síntesis, la evidencia muestra que la motivación por atender un mensaje favorable a una causa social se incrementa con la presencia de una fuente consonante, y mejora la imagen de la fuente neutral (marca comercial). Pero, ¿qué sucede si alguien es expuesto a un mensaje consonante con su sensibilidad social, pero de una fuente disonante? No se han encontrado estudios que valoren el efecto de un mensaje en una fuente disruptiva sobre la sensibilización hacia la causa social, expresada en una respuesta activa (cognitiva, afectiva o conductual) en favor de causas sociales.

La valencia del argumento y la fuente

Tener actitudes no es suficiente para influir sobre la conducta. Las personas deben creer que sus actitudes son correctas o sentirse bien con ellas (Briñol & Petty, 2015). Para un activista recibir información sobre un resultado positivo de la acción social que defiende puede ser un argumento fuerte en defensa de su posición. Sin embargo, un resultado negativo en la acción puede ser visto como un argumento débil en relación a la efectividad de la acción social. En este sentido, la información que muestra el resultado positivo de una acción social podría incitar a sentirse bien con su posición, lo que no requiere fortalecerla. Es una información que podría disminuir la motivación por la acción. El argumento débil podría tener un efecto opuesto.

La credibilidad de la fuente interactúa con el efecto de la valencia del argumento. La literatura indica que cuando el mensaje contiene argumentos fuertes, la fuente altamente creíble favorece las actitudes previas mejor que cuando la fuente es poco creíble; sin embargo, este efecto es el inverso cuando los argumentos son débiles (Briñol & Petty, 2015). Si el argumento es débil puede contradecir lo esperado y desconfirmar la efectividad de la acción. Si la fuente ofrece argumentos consistentes con los valores de la persona, esta persona estará más inclinada a estar de acuerdo con el mensaje, pues razonará si el mensaje se ajusta a ella o sus valores, debe ser bueno (Briñol & Petty, 2015). Si se recibe información de que la acción está siendo efectiva, se puede interpretar que no es necesario hacer nada más.

Un fracaso en la acción pro-causa puede incitar a la acción para defenderla, pero, si es emitido por un medio pro-actitudinal, podría desmotivar, debido a que se puede interpretar que, si informan de un fracaso, no es porque sea real, sino porque quieren incitarnos a actuar. Sin embargo, un emisor poco creíble en trabajar en favor de la causa podría incrementar la motivación por defenderla ante la perspectiva de que está fracasando la acción, quizás debido a que está en manos de medios poco proclives a defenderla. No se ha investigado directamente sobre esta combinación de factores en receptores diferenciados por su grado de favorabilidad ante una causa social.

Los resultados de esta investigación evidencian que comunicar en positivo o en negativo, centrarse en los éxitos o en los fracasos (en términos de la psicología social, la valencia positiva o negativa de la comunicación), tienen relevancia para mantener a los activistas en tensión reivindicativa.

El modelo de comunicación presentado por Pinazo y Nos-Aldás (2016) sugiere que la motivación en favor de una causa es modulada por una estrategia de comunicación asociada al contexto en que se presenta el mensaje. Un contexto negativo hacia la causa en un medio pro-actitudinal podría incitar una motivación favorable al medio, y no a la causa. El objetivo de este trabajo es valorar si el contexto de interacción activismo político, fuente y valencia del resultado de la acción influyen en la motivación pro-causa. En concreto, defendemos la hipótesis de que presentar ante un grupo de activistas pro-causa un mensaje de valencia negativa emitido por una fuente contra-actitudinal, motivará más a favor de la causa que presentar un mensaje de valencia negativa emitido por una fuente pro-actitudinal. Mientras, los mensajes con valencia positiva no tendrán efectos diferenciados sobre la motivación pro-causa, independientemente de la actitud hacia la misma del medio que lo emita.

Método

Muestra

El universo de la investigación está constituido por personas que cumplen dos criterios: 1) tener un compromiso con causas sociales; 2) Haber participado en alguna movilización pro-evitación de desahucios. Inicialmente, se distribuyeron 400 cuadernillos de los que se descartaron 24 por no estar completamente cumplimentados. Además, se han eliminado otras 79 personas que no habían participado en ninguna iniciativa de demanda de justicia por los afectados en los desahucios (manifestaciones, huelgas, petición de firmas, denuncias y uso de las redes u otro tipo de acciones que tuvieran como fin defender la causa de evitación de desahucios).

La distribución final por condiciones ha sido: fracaso/fuente favorable (70 personas), fracaso/fuente desfavorable (83 personas), éxito/fuente favorable (81 personas) y éxito/fuente desfavorable (63 personas). La muestra final está constituida por un total de 297 personas. Los hombres constituyen el 37,4% de la muestra (N=111), mientras que las mujeres son el 62,6% (N=186).

La edad oscila entre 18 y 70 años (M=34,23; SD=13,91). El nivel de estudios se distribuye entre quienes no tienen estudios universitarios, el 56,2% (N=167), y quienes sí han realizado estudios universitarios, el 43,8% (N=130). Del total de la muestra, el 34,7% (N=103) de las personas encuestadas declaran tener un trabajo remunerado, mientras que el 65,3% (N=194) no tienen trabajo.

El nivel de ingresos mensuales se evaluaba con una escala ordinal (1 a 8): no ingresos (1), menos o igual a 300 (2), 301 a 600€ (3), 601 a 1.000€ (4), 1.001 a 2.000€ (5), 2.001 a 3.000€ (6), 3.001 a 5.000€ (7) y más de 5.000€ (8). La media de ingresos se sitúa en el intervalo de 301 a 600€.

Diseño y procedimiento

Hemos realizado un estudio experimental bifactorial 2 resultado de la acción (negativa versus positiva) x 2 fuente (favorable versus desfavorable). Se ha elaborado un caso ficticio de desahucio en formato de noticia revisado por un grupo de expertos en periodismo, publicidad, sociología, semiótica y psicología social. Una vez elaborado el cuerpo central del mensaje, se han planteado las condiciones experimentales.

El cuadernillo con las condiciones experimentales fue entregado personalmente por los colaboradores del estudio a las personas previamente seleccionadas. Primero debían responder a cuestiones de carácter demográfico (sexo, edad, estudios, trabajo, ingresos) y grado de participación en demandar justicia social para los afectados por los desahucios. Posteriormente, en hoja aparte, cada participante leía una única noticia sobre un caso de desahucio redactada en función de una de las cuatro condiciones experimentales, y, al pasar la página, debían responder a una batería final de preguntas.

Variables dependientes

Motivación moral (MM): utilizando los mismos ítems de Pinazo y Nos-Aldás (2016), se evaluó el juicio moral o grado en que la acción observada en la noticia transgrede normas de justicia social o éticas con dos preguntas: «¿es socialmente injusto lo que le ha pasado a esta familia?», «¿es inmoral no hacer nada para evitar esta situación?». Ambos ítems tienen una alta consistencia interna (α=,798; M=7,47; SD=2,06).

Motivación afectiva: se ha utilizado una versión de ítems seleccionados de la escala PANAS-X (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988), pero en lugar de una aproximación al efecto en dos dimensiones, una negativa y otra positiva, hemos optado por seleccionar los ítems en función del objetivo para el que se evalúa el estado afectivo (Lambert, Eadeh, Peak, Scherer, Schott, & Slochower, 2014). Se han considerado dos estados afectivos motivadores relacionados con el activismo social: 1) el estado afectivo que impulsa a la acción; 2) el estado afectivo asociado al rechazo de la situación. A partir de PANAS se han escogido los ítems que mejor podrían representar estos estados. Para el estado afectivo de acción (MAA) se han escogido los estados «Energético», «Entusiasta», «Inspirado» y «Activo» (α=,800; M=4,54; SD=1,65) y para representar la motivación de rechazo (MAR) los estados «Hostil», «Irritable», «Nervioso» y «Alterado» (α=,805; M=5,07; SD=1,83).

Motivación pro-conducta (MpC): evalúa la predisposición a colaborar por causas justas. Se trata de un conjunto de tres conductas relacionadas con el activismo social: «colaborar en acciones de protesta», «invertir mi dinero en bancos éticos, que no dan intereses, e invierten solo en empresas que favorecen las causas justas», «denunciar a las empresas que actúan de un modo engañoso, o injusto con otros, para obtener beneficios». Mediante una escala de 1 (Nada de acuerdo) a 9 (Muy de acuerdo), se les pregunta, en relación a una situación de desahucio bancario, «¿qué estaría Usted dispuesto a hacer para participar en la solución de este problema?». Dado que la consistencia interna de los tres ítems es alta, α=,711, hemos compuesto una variable agregada que evalúa la predisposición a actuar en favor de causas sociales (M=6,73; SD=1,83).

Variable control

Credibilidad del mensaje: variable de control para evaluar si el receptor ha entendido el núcleo del mensaje. El efecto de un mensaje depende de la motivación para ser procesado por el receptor, según algunos modelos de persuasión, especialmente el de probabilidad de elaboración (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Como factor de credibilidad se ha evaluado la creencia en la veracidad de la noticia. Se realizan dos preguntas sobre la veracidad de la noticia: 1) «la noticia está manipulada»; 2) «esta noticia es falsa» (α=,565). La medida agregada de la credibilidad de la noticia tiene una M=3,97 (SD=2,44). Una puntuación alta indica que no creen en el contenido de la noticia.

Resultados

El análisis de los datos se ha realizado con el programa estadístico SPSS v24. Antes de realizar el estudio del efecto de las condiciones sobre las variables dependientes, hemos hecho diversos análisis para valorar los sesgos que pudiera haber en función de variables demográficas y la motivación por elaborar el mensaje. Los resultados reflejan que la muestra está equilibrada en las distintas condiciones: la proporción del sexo en cada condición experimental es similar (χ2=1,62; p=,656), al igual que la distribución de los niveles de estudios (χ2=0,99; p=,805) y el tener o no trabajo (χ2=0,99; p=,092). El ANOVA por la edad (F=0,57; p=,634) y por el nivel de ingresos (F=1,72; p=,163), indican que estas variables también están distribuidas equitativamente en las condiciones experimentales.

El análisis univariado de la varianza (UNIANOVA) para valorar si los receptores han reaccionado de modo diferenciado a la lectura del mensaje, en la condición a la que ha sido expuesto cada grupo, percibiéndolo como falso o verdadero, indica que así ha sido (F=5,513; p=,001; η2=,053). La prueba post-hoc de comparación de medias Tukey muestra diferencias entre varios pares. Existen diferencias (p=,027) entre la noticia de éxito vs. fuente desfavorable (M=4,62; SD=2,19) en relación a la noticia de fracaso vs. fuente desfavorable (M=3,50; SD=2,40). También hay diferencias (p=,018) entre la noticia de éxito vs. fuente favorable (M=4,49; SD=2,34) en relación a la noticia de fracaso vs. fuente favorable (M=3,35; SD=2,40). Hay diferencias (p=,013) entre la noticia de éxito vs. fuente desfavorable (M=4,62; SD=2,66) en relación a la noticia de fracaso vs. fuente favorable (M=3,35; SD=2,40). Y, por último, hay diferencias (p=,040) entre la noticia de fracaso vs. fuente desfavorable (M=3,50; SD=2,19) en relación a la noticia de éxito vs. fuente favorable (M=4,49; SD=2,34). Estas diferencias por pares nos indican que los receptores se creen menos la noticia cuando les dicen que ha tenido éxito su causa, indicando su predisposición a esperar un fracaso de la misma. Asimismo, se observa una tendencia a no creerse a la fuente desfavorable. Estas diferencias son las esperadas en un público favorable a la causa social, indicando que los casos han sido leídos y comprendidos por la muestra. Con la confianza en la atención de los participantes hacia la investigación podemos pasar a evaluar el efecto de los casos en la motivación de los receptores por la causa social. Se ha usado un análisis múltiple de la varianza (MANOVA) para comparar el efecto de la interacción Resultado (positivo o negativo) de la acción social vs. Fuente sobre los resultados motivacionales (Motivación Moral, Motivación Afectiva y Motivación por la Acción).

Algunos indicadores muestran que se han cumplido las asunciones estadísticas del MANOVA. El test M de Box=69,128, p<,000 informa que no está en cuestión la homocesdaticidad de las matrices de covarianza, por lo que la interpretación de la prueba multivariante se realizará mediante la Traza de Pillai (Tabachnick, Fidell, & Ullman, 2007). El Test de Levene para la igualdad de varianzas no es significativo para las variables MpC y MAA, por lo que para estas variables utilizaremos la prueba de Tukey en el análisis post-hoc. Por su parte la prueba de Levene sí fue significativa, indicando falta de homogeneidad en las varianzas de las muestras, en las variables MM y MAR. Debido a esto, para estas variables el análisis post-hoc se realizará con la prueba C de Dunnett.

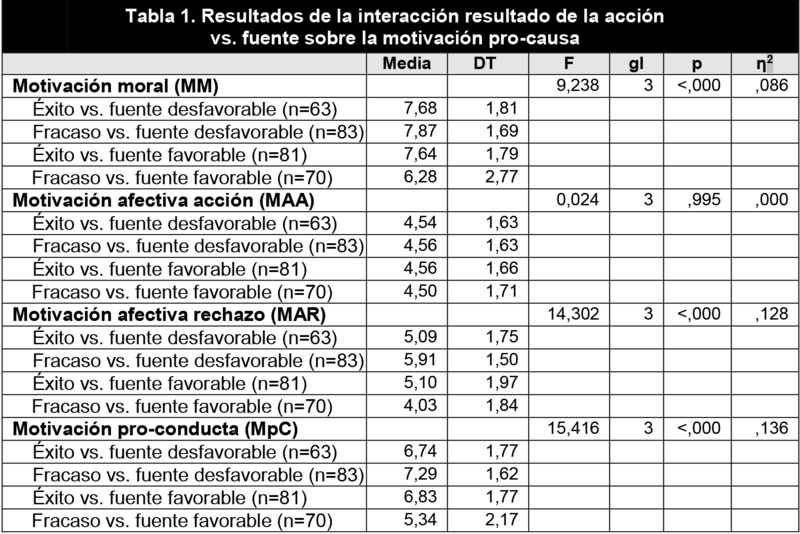

|

|

Los resultados de la MANOVA sobre la motivación revelan un efecto principal significativo, Traza de Pillai =,269 (F=7,191; =,000), con un tamaño pequeño del efecto (η2=,090). El test univariado revela efectos significativos en la dirección esperada para los efectos de la motivación (Tabla 1).

Para saber entre qué pares están las diferencias en el conjunto del modelo de interacción, realizamos la comparación post-hoc con la prueba de Tukey, que ofrece los siguientes resultados. Para la MAA, la comparación entre los cuatro grupos no presenta diferencias significativas. Encontramos diferencias en algunos pares de las condiciones presentadas en los efectos sobre la motivación. Para la MpC, la comparación por pares de las condiciones experimentales revela que existen diferencias significativas entre la condición de fracaso vs. fuente desfavorable con fracaso vs. fuente favorable (p<,000), y la condición de éxito vs. fuente desfavorable con fracaso vs. fuente favorable (p<,000). La comparación de las medias (Tabla 1) sugiere que los receptores tienen mayor motivación a actuar cuando la noticia de fracaso proviene de una fuente desfavorable.

La prueba post-hoc C de Dunnett para la MM indica que existe una diferencia de medias alta para la comparación de los grupos de éxito vs. fuente desfavorable con fracaso vs. fuente favorable (p<,000), entre los grupos fracaso vs. fuente desfavorable con fracaso vs. fuente favorable (p<,000), y entre los grupos éxito vs. fuente favorable con fracaso vs. fuente favorable (p<,000). Estas diferencias muestran que los receptores se sienten más motivados moralmente cuando la noticia proviene de una fuente desfavorable, o de una fuente favorable que informa del éxito de la acción. La prueba C de Dunnett para la MAR indica diferencias de medias significativas para la comparación de los grupos de éxito vs. fuente desfavorable con fracaso vs. fuente favorable (p=,002), entre los grupos fracaso vs. fuente desfavorable con fracaso fuente favorable (p<,000), y entre los grupos éxito vs. fuente favorable con fracaso vs. fuente favorable (p=,001). La comparación de medias indica que la mayor motivación en rechazar la noticia se presenta cuando la noticia de fracaso aparece en un medio hostil, o en un medio consonante si es una noticia de éxito.

Los resultados indican que la recepción de una noticia que muestra una valencia negativa en la acción social presentada por una fuente desfavorable, genera mayor rechazo afectivo al fracaso de la causa, y predispone mejor a actuar en favor de las causas sociales. Sin embargo, no tiene efecto en motivaciones afectivas positivas.

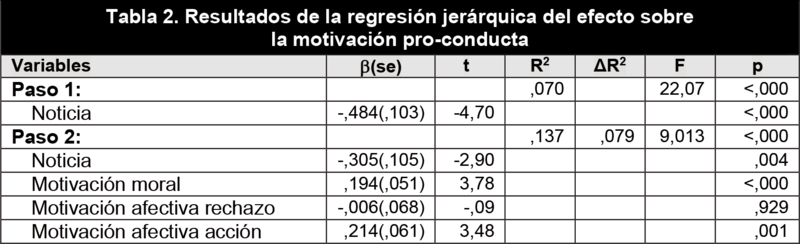

Para evaluar si la MpC es efecto directo de la interacción fuente vs. valencia del resultado o si hay variables intervinientes, hemos realizado un análisis jerárquico de regresión (Tabla 2).

|

|

Uno de los objetivos de este análisis es valorar si el efecto sobre la motivación pro-conducta es directo, mediado por otras variables o modulado por ellas. El procedimiento más frecuente para probar mediación en una investigación fue desarrollado por Kenny (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Hayes, 2009) y consta de cuatro etapas. En primer lugar, la variable predictora causal independiente, en nuestro caso la noticia, debe tener un efecto directo sobre la variable dependiente. Esta situación se comprueba observando tanto el efecto en la MANOVA (Tabla 1), como en el primer modelo de regresión obtenido (Tabla 2). En segundo lugar, debemos comprobar que la variable independiente tiene un efecto sobre las variables potencialmente mediadoras. Este segundo supuesto solo se cumple en nuestro caso con la MM, y la MAR (Tabla 1). En tercer lugar, estas tres variables (Noticia, MM y MAR) deberían tener un efecto significativo directo sobre la variable dependiente MpC, condición que se cumple en el Paso 2 de regresión para la variable «motivación moral» (Tabla 2). Y finalmente, el efecto de la variable mediadora sobre la variable dependiente debería anular el efecto directo de la variable independiente sobre la dependiente, situación que no se produce puesto que el efecto de la noticia sigue siendo significativo en el Paso 2. No se observa, pues, mediación. Por su parte la hipótesis de moderación se confirma si el incremento en proporción de variabilidad debida a la interacción es significativo. Observando la Tabla 2, vemos que este criterio se cumple para el Paso 2.

Los resultados del análisis jerárquico de regresión muestran que el efecto de la noticia sobre la motivación de actuar está sesgado por la presencia de al menos dos factores: la MM y la MMA. Estudiando las condiciones para valorar el tipo de participación de estas variables, vemos que no cumplen con los criterios exigidos a la mediación, pero sí al exigido a la modulación, por lo que concluimos que la MM y la MAA son variables moduladoras en el efecto de la noticia sobre la motivación por la acción.

Discusión y conclusiones

La participación en defensa de las causas sociales no solo se produce cuando hay un contexto favorecedor como el digital (Sampedro & Martínez-Avidad, 2018), es necesario que la causa motive a la audiencia. En este estudio hemos puesto a prueba la hipótesis de que un mensaje que centre la atención en la causa (resultado del cumplimiento de la causa) motivará a la audiencia cuando interactúe con la favorabilidad de la fuente. Hemos analizado el efecto sobre la respuesta pro-causa de la interacción fuente vs. resultado de la acción pro-causa sobre una audiencia previamente sensibilizada por la causa social defendida. Todo juicio sobre un objeto social viene determinado tanto por un proceso cognitivo como afectivo (Oskamp, 1991). En la forma de evaluar la eficacia de la comunicación se suelen considerar respuestas utilitaristas como la cantidad o frecuencia de las donaciones (Pinazo & Nos-Aldás, 2016) o la probabilidad de que un mensaje sea compartido en los «social media» (Brady, Wills, Burkart, Jost, & van-Bavel, 2018; Hansen, Arvidsson, Nielsen, Colleoni, & Etter, 2011). En ambos casos, o se valora la penetración de la marca o de la pieza comunicativa, pero el contenido o la sensibilización sobre la causa en sí misma no forma parte de esta evaluación. En este trabajo hemos puesto el foco en la sensibilización, en la respuesta pro-causa y en las condiciones en las que esta puede intensificarse.

Los resultados muestran que presentar el fracaso de la causa sensibiliza mejor a una audiencia pro-causa. Esta sensibilización se traduce en que hay mayor implicación afectiva con el rechazo al fracaso de la causa, y mayor predisposición en actuar para reparar ese fracaso. Esta percepción de fracaso se acentúa cuando es un medio hostil el que la transmite, de modo que la interacción comunicación de fracaso de la causa vs. medio hostil es una fuente de sensibilización afectiva e intencional pro-causa más efectiva que la exposición a los medios afines y la comunicación de éxitos de la causa. Este efecto es modulado por la motivación moral y afectivo positiva de la audiencia que potencia este efecto. La motivación moral y la motivación afectiva de acción modulan el efecto de la noticia sobre la motivación pro-causa. Es decir, la predisposición a actuar es consonante con la recepción de una noticia de fracaso en un medio hostil. Pero este efecto se incrementa o disminuye en función del efecto de la noticia sobre la motivación moral y afectiva de acción. Cuanta más percepción de injusticia social revele la noticia y más despierte emociones de acción, más probable es que la persona esté dispuesta a actuar en favor de la causa social.

Los resultados evidencian que la valencia positiva o negativa de la comunicación tienen relevancia para mantener a los activistas en tensión reivindicativa. Están en consonancia con la investigación que advierte sobre la eficacia de plantear estrategias comunicativas que vayan más allá de la reacción emocional o de identificación con la marca (Pinazo & Nos-Aldás, 2016). Por otro lado, los resultados de este trabajo señalan que al menos una de las razones por las que los «social media» pueden aumentar la participación o el compromiso ciudadano (Boulianne, 2009; Dimitrova, Shehata, Strömbäck, & Nord, 2014; Norris, 2001; Papacharissi, 2002), es sacando a las personas activistas de sus zonas de confort. La posibilidad que ofrecen los media de dar acceso a fuentes de información que contrarían las convicciones de los receptores puede ser una de las razones por las que estos se vuelvan más activos en la defensa de sus causas.

Los resultados de este trabajo amplían el concepto de eficacia en la comunicación de cambio social desde su capacidad movilizadora y educativa (Obregón & Tufte, 2017; Pinazo & Nos-Aldás, 2016; Seguí-Cosme & Nos-Aldás, 2017).

Limitaciones del estudio

En base a las contribuciones teóricas de los resultados, una limitación clave es la ausencia de un análisis comparativo de la muestra pro-causa con una muestra anti-causa. Un diseño que identificara a este tipo de público y analizara sus reacciones sería una importante contribución empírica y teórica al conocimiento de cómo difundir causas sociales.

Dado que es un experimento realizado fuera de laboratorio, los resultados pueden verse afectados por la disminución del control interno que ello implica. Aunque se ha controlado parcialmente la atención puesta en la lectura del mensaje, no podemos asegurar que el rechazo de la fuente haya intervenido con más fuerza que la necesidad de evaluación cuidadosa del significado del mensaje. Son aspectos que aluden a mejorar las condiciones de control en futuras investigaciones.

Otra cuestión que reduce la relevancia de los resultados es si pueden ser generalizables en diferentes marcos comunicativos. Replicar el estudio en diversos contextos de comunicación aportaría evidencia adicional sobre cómo los mensajes contra la causa en fuentes hostiles pueden activar la motivación de la audiencia pro-causa. Se requiere replicar el estudio en muestras distintas con variantes poblaciones y/o culturales.

Ver anexo condiciones experimentales aplicadas al diseño de la noticia en https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9466499.

Notes

- Ver anexo condiciones experimentales aplicadas al diseño de la noticia en https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9466499.

References

- ArceneauxK, JohnsonM, . 2015.does media choice affect hostile media perceptions? Evidence from participant preference experiments&author=Arceneaux&publication_year= How does media choice affect hostile media perceptions? Evidence from participant preference experiments.Journal of Experimental Political Science 2(1):12-25

- ArceneauxK, JohnsonM, CrydermanJ, . 2013.persuasion, and the conditioning value of selective exposure: Like minds may unite and divide but they mostly tune out&author=Arceneaux&publication_year= Communication, persuasion, and the conditioning value of selective exposure: Like minds may unite and divide but they mostly tune out.Political Communication 30:2013-231

- BakkerT P, De-VreeseC H, . 2011.news for the future? Young people, Internet use, and political participation&author=Bakker&publication_year= Good news for the future? Young people, Internet use, and political participation.Communication Research 38(4):451-470

- BaronR M, KennyD A, . 1986.moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations&author=Baron&publication_year= The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51(6):1173-1182

- Becker-OlsenK L, CudmoreB A, HillR P, . 2006.impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior&author=Becker-Olsen&publication_year= The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior.Journal of Business Research 59(1):46-53

- BoulianneS, . 2009.Internet use affect engagement? A meta-analysis of research&author=Boulianne&publication_year= Does Internet use affect engagement? A meta-analysis of research.Political Communication 26(2):193-211

- BradyW J, WillsJ A, BurkartD, JostJ T, Van-BavelJ J, . 2018.ideological asymmetry in the diffusion of moralized content on social media among political leaders&author=Brady&publication_year= An ideological asymmetry in the diffusion of moralized content on social media among political leaders.Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 49(2):192-205

- BriñolP, PettyR E, . 2015.and validation processes: Implications form media attitudes change&author=Briñol&publication_year= Elaboration and validation processes: Implications form media attitudes change.Media Psychology 18(3):267-291

- BriñolP, PettyR E, TormalaZ L, . 2004.of cognitive responses to advertisements&author=Briñol&publication_year= Self-validation of cognitive responses to advertisements.Journal of Consumer Research 30(4):559-573