Abstract

New technology-based firms (NTBFs) are usually created by entrepreneurs with a technical or scientific background. They are highly skilled at a given technology but they may not have any business experience. Nonetheless, these firms need a balance between technical and managerial skills in order to succeed. Most technology entrepreneurs focus on perfecting a particular technology rather than on the market and customer preferences, which worsens the problem. They often have a ‘technology push’ view of innovation. There is abundant literature on start-up knowledge and on the managerial skills required of entrepreneurs. However, little attention is paid to the influence of managers in the ‘technology push’ view of innovation in NTBFs. This research is devoted to exploring this gap. The case study was chosen as the research methodology. Three Spanish NTBFs from the healthcare and the ceramic hard coatings industries were studied. It was concluded that the main role of managers in NTBFs consists in adopting a market orientation, limiting exploration, and ensuring employees have the necessary skills and accomplish their functions. Managers need to partner with experts and make sure investors understand the firm’s business model.

Keywords: NTBF; technical skills; managerial skills; market pull; technology push

1. Introduction

New technology-based firms (NTBFs) need a combination of technical and managerial skills in order to be successful (Vesper, 1990; Murray, 1996; Oakey, 2003; Colombo and Piva, 2008). However, they are mostly set up by engineers and scientists, individuals with a technical or scientific background, highly skilled at a given technology (Roberts, 1991; Zucker, Darby, and Brewer, 1998), but without any business education or experience as managers or entrepreneurs. Moreover, technology entrepreneurs often have a ‘technology push’ instead of a ‘market pull’ view of innovation. They focus on perfecting the technology on which the new venture is based at the expense of neglecting the market and their customers’ preferences (Rice, Matthews, and Kilcrease, 1995; Oakey, 2003).

There is abundant literature on start-up knowledge (Wiklund and Shepherd, 2003; West and Noel, 2009) and on the managerial skills entrepreneurs need to have (Capaldo and Fontes, 2001; Wright et al., 2007; Scillitoe and Chakrabarti, 2010). These skills are essential for identifying and assessing target markets, raising external funds, and managing teams and employees. The literature refers to business education, social capital, and prior managerial and start-up experience, as sources or drivers of these managerial skills (Ganotakis, 2012; Yli-Renko, Autio, and Sapienza, 2001). A review of the relevant literature cited in section 2.3. on the skills technology entrepreneurs must possess shows the relationship between the founders’ background and the ability of NTBFs to raise private funds, grow, or perform as expected.

The critical nature of managerial skills applies to both technology and non-technology entrepreneurs. However, engineers and scientists are more likely to lack a background in management. They may have particular difficulties in identifying markets, understanding customers’ preferences, and adopting a market orientation when selling the product. They may not possess the necessary financial expertise to present the venture’s financials to potential investors.

The literature on the skills required of technology entrepreneurs pays attention to how NTBFs, founded by entrepreneurs without any business education and experience, can acquire and develop the managerial skills needed. It suggests solving the problem through management education (Chandler and Jansen, 1992; Oakey, 2003; Wright et al., 2007). Hiring experienced individuals, partnering with them (Murray, 1996; Colombo and Grilli, 2010), or relying on the coach function venture capitalists may exert (Baum and Silverman, 2004) are other options considered.

However, the reviewed literature does not provide much detail on the influence of managers on the inception and subsequent development of NTBFs founded by entrepreneurs who have no background in business and hold a ‘technology push’ view of innovation. We hypothesize that managers in NTBFs must play a role to help overcome the absence of the appropriate background and counteract the ‘technology mindset’ of founders and employees. As many NTBFs fail due to focusing on technology rather than on the market, understanding the influence managers may exert on shifting the focus of the organization towards the market and towards customers’ preferences is a topic of interest for research in NTBFs. The relation between managerial skills, the background of technology entrepreneurs and the ‘technology push’ view of innovation deserves further research efforts. The purpose of this research is to shed new light on the role of managers in counteracting a ‘technology push’ view of innovation in NTBFs founded by engineers and scientists without any start-up experience. Our aim is to answer the research question “How can managers counteract a ‘technology push’ view of innovation in NTBFs?”

This research intends to specify the role of managers in NTBFs in making their organization stay focused on the market and not on technology, as part of their managerial work (O’Gorman, Bourke, and Murray, 2005) and entrepreneurial competencies (Man, Lau, and Chan, 2002).

The paper is structured as follows: theoretical background, methodology, multiple-case study, results, discussion, and conclusions.

2. Theoretical background

In this section, we will refer to the specificities of technology entrepreneurship by describing the profile of most technology entrepreneurs. We will specify the knowledge required to create a new venture, as well as the skills, roles, and competencies of managers in NTBFs. This section will also address the influence of the founders’ background regarding the firm’s external funding, growth, and performance.

NTBFs are small size firms based on emerging technologies that produce novel outputs (Cooper and Bruno, 1977). They make intensive and sustained R&D efforts and pay high salaries to highly skilled workers (Brinckmann, Salomo, and Gemuenden, 2011). Founders of NTBFs are often engineers or scientists who created the venture’s technology from scratch and have been working on its development (Roberts, 1991; Zucker, Darby, and Brewer, 1998). Although engineers and scientists possess profound knowledge of the venture’s core technology, they usually lack business education and experience when managing businesses or establishing new ventures (Capaldo and Fontes, 2001; Scillitoe and Chakrabarti, 2010). This is a drawback, as factors such as business education and experience are considered to be drivers of the managerial skills required of entrepreneurs when founding a new venture. The founders’ background influences the ability of NTBFs to raise private funds (Colombo, Grilli, and Verga, 2007; Patzelt, 2010), to grow (Colombo and Grilli, 2005), or to perform as expected. Ganotakis (2012) refers to human capital and Yli-Renko, Autio, and Sapienza (2001) to social capital as ultimate drivers of performance.

Some authors state that engineers and scientists, when are involved in converting technology into marketable products or services, therefore becoming technology entrepreneurs, focus on that particular technology and have a ‘technology push’ view of innovation instead of a ‘market pull’ view. They do not take their customers’ preferences into account. Technology entrepreneurs may focus on perfecting their invention to meet their expectations (Rice, Matthews, and Kilcrease, 1995) and may value technical elegance more than customer needs (Oakey, 2003). Venture capitalists view them as too concerned with technical perfection and not concerned enough with market satisfaction (Sapienza and Amason, 1993). Business proposals developed by scientists are often ‘technology push’-oriented and pay little attention to the market opportunity (Wright et al., 2007).

Conversely, Vesper (1990), Murray (1996), and Oakey (2003) claim that NTBFs need a balance between technical and managerial skills in order to succeed. The presence within the founding team of both technical and managerial skills originates synergistic effects (Colombo and Piva, 2008). However, this perfect balance is present in the founding teams of very few companies. Gimmon and Levie (2010) found the combination of technical background and business management expertise in only 25% of a sample of firms. More recently, Welter, Bosse, and Alvarez (2013) examined how managerial and technological capabilities interact to affect firm performance. They studied small biotech firms in an alliance with a larger pharmaceutical firm. They concluded firms perform better when both capabilities are present, and having one set of capabilities without the other is correlated with lower performance.

- 2.1. Start-up knowledge

In order to be successful, founders of new ventures must possess start-up knowledge, usually acquired through prior participation in start-ups. Wiklund and Shepherd (2003) identify three types of knowledge required to create a new venture: knowledge about the industry’s technology, knowledge about the strategic approach to be adopted in the industry, and knowledge about creating and harvesting new ventures. Venturing also requires knowledge regarding organizing and planning (West and Noel, 2009).

When founders lack start-up knowledge, firms may hire or partner with an expert. Colombo and Piva (2008) state that partnering is preferred to hiring because having a stake in the firm’s future profits increases commitment. Firms can also benefit from the skills of their investors. Venture capitalists provide firms with additional resources and capabilities and exert a coach function (Baum and Silverman, 2004). They can be active partners when it comes to complementing the founders’ skills (Murray, 1996). Besides funding, they can assist founders in strategic planning and finance and may extend the social capital of the firm through their network of contacts (Colombo and Grilli, 2010). Technology entrepreneurs can acquire the skills they lack through business education (Chandler and Jansen, 1992; Oakey, 2003). Wright et al. (2007) say university programs combining science and technology with business management provide great benefits.

- 2.2. Skills, roles, and competencies of managers in NTFBs

Wright et al. (2007) define three stages in the entrepreneurial process and claim for a balanced combination of capabilities. In the first stage, creativity and technological knowledge are required to recognize opportunities. In the second one, managerial skills are needed to grow. In the third one, commercial skills are needed to sell the product adopting a market orientation. Capaldo and Fontes (2001) remark that, due to a lack of business education and business experience, technology entrepreneurs may have problems with identifying niche markets and recognizing who will buy their products or services.

Managerial skills are very important to identify and assess the target market. Because of their ‘technology push’ view of innovation, founders may need marketing assistance to understand buyer preferences during the early stages of product or service development (Scillitoe and Chakrabarti, 2010). Managerial skills are also critical to acquire external funds because technology entrepreneurs may lack the financial expertise to create forecasts and submit them to venture capital firms. Finally, managerial skills are essential to manage teams and employees: how to organize the firm, how to motivate employees, how to coordinate teams, how to mitigate conflicts, and how to assess employees and provide them with feedback (Capaldo and Fontes, 2001).

Scillitoe and Chakrabarti (2010) list some of the fields in which NTBFs may need support: business planning, personnel recruiting, marketing, laws, accessing external funds, accessing business and industry contacts, technology transfer, learning of buyer preferences, and intellectual property protection. Oakey (2003) refers to personnel management, finance, marketing, and business strategy.

O’Gorman, Bourke, and Murray (2005) replicate Mintzberg's (1973) structured observational method in a new context, that of small growth-orientated businesses. They hypothesize that typically the managerial responsibility of owner-managers in small businesses extends beyond the CEO function to include many direct line management responsibilities (e.g. meeting with customers). They conclude that, in terms of Mintzberg’s 10 roles, the roles of Leader, Monitor and Entrepreneurial account for 62% of managerial work; the roles of Liaison and Resource Allocator account for only 18%; and the roles of Figurehead, Spokesman, Disturbance Handler, Negotiation and Disseminating account for only 20%. They also deduce that, as far as the functional nature of managerial activity is concerned, General Management, Sales/Marketing, Production and Finance account for 86% of managerial work; while R&D, Applied Engineering, Market Research, Distribution, Personal and Legal account for only 14%.

Man, Lau, and Chan (2002) present a model of SME competitiveness that brings together four constructs: entrepreneurial competencies, competitive scope, organizational capabilities and firm performance. They use a categorization of six competency areas (opportunity, relationship, conceptual, organizing, strategic, and commitment) and propose that the opportunity, relationship, and conceptual competencies are positively related to the competitive scope; the organizing, relationship, and conceptual competencies are positively related to the organization capabilities; and the strategic and commitment competencies are positively related to the long-term performance, a relationship moderated by the competitive scope and the organization capabilities. This theoretical framework shows that differences in long-term performance are explained by entrepreneurial competencies and that an entrepreneur needs a balance between various competencies (i.e. the lack of organizing competencies hinders the development of organizational capabilities, which in turn limits the use of strategic and commitment competencies).

- 2.3. The relation between founders’ background and external funding, firm growth, and firm performance

Obtaining external funds to support product development is one of the major challenges of technology entrepreneurs (Patzelt, 2010) because high risk projects and information asymmetries difficult the financing of NTBFs without a track record (Colombo and Piva, 2008). Financial management is therefore the most relevant competence in the initial stages (Brinckmann, Salomo, and Gemuenden, 2011). Failure to obtain the external funds required to afford R&D and to finance sales growth may compromise the future of the start-up.

Table 1 enumerates some characteristics of founders’ background that influence external fund-raising.

Founders’ education and experience are a quality signal for investors. They provide information that reduces uncertainty and hence increases the chances of successful fund-raising.

According to Colombo and Grilli (2005), founders’ education and prior work experience positively affect growth. Colombo and Grilli (2010) and later Criaco et al. (2014) evidence that the human capital of founders has a direct positive effect on the growth of NTBFs and an indirect positive effect mediated by the attraction of venture capital investments, thus showing that growth is enabled by fund-raising.

Founders’ background also influences firm performance, and a lack of managerial skills is a major drawback that reduces survival chances (Capaldo and Fontes, 2001).

Prior experience gained with other employers is an indicator of success (Willard, Krueger, and Feeser, 1992). Founders’ business management expertise positively affects venture survival (Gimmon and Levie, 2010). When teams are more heterogeneous and include individuals with both technical and commercial experience, firms achieve superior performance (Colombo and Piva, 2008).

Some authors have examined the relationship between prior entrepreneurial experience and new venture performance. Baum and Silverman (2004) caution against an overestimation of the role of prior start-up experience, one of the venture capital evaluation criteria. Chandler and Jansen (1992) show that the number of businesses previously initiated and the years spent as an owner-manager are not strongly related to the performance of the venture. Song et al. (2008) conclude that founders’ management experiences are correlated to venture performance while founders’ start-up experiences are not. West and Noel (2009) show that there is no relationship between previous start-up experience and new venture performance.

From the literature review, we conclude that: 1) technology entrepreneurs may not have any business education and experience in managing businesses and creating new ventures; 2) the managerial skills required to create and develop a firm are based on the founders’ background; 3) technology entrepreneurs usually have a ‘technology push’ view of innovation; 4) NTBFs need a balance between technical and managerial skills in order to succeed; and 5) managerial skills are critical to identify and assess target markets, to raise external funds, and to manage teams and employees. Considering these conclusions, a greater understanding of the role managers must play in NTBFs is necessary.

3. Methodology

The aim of this investigation is to answer the research question “How can managers counteract a ‘technology push’ view of innovation in NTBFs?” The case study was chosen as the research methodology because the research question starts with ‘how’ (Yin, 2003) and the purpose of the inquiry is to understand a specific phenomenon and to a build theory using qualitative evidence, rather than test hypotheses and generalize findings. Due to the exploratory nature of this study, we chose a qualitative approach based on semi-structured interviews with the owner-managers of three NTBFs. The expected outcome is a model describing the relationships between some constructs to be validated using quantitative methods. The three firms studied were WIRS, Sagetis Biotech, and Flubetech.

In this research we followed the Gioia Methodology (Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton, 2012), a systematic approach to new concept development and grounded theory articulation designed to bring qualitative rigor to conducting and presenting inductive research. It is a procedure that guides the conduct of the research and the presentation of the findings in a way that demonstrates the connections between data, the emerging concepts and the resulting grounded theory. It consists of a ‘1st-order’ analysis using informant-centric terms and a ‘2nd-order’ analysis using researcher-centric concepts, themes and dimensions. The full set of terms, concepts, themes and dimensions is the basis for the ‘data structure,’ which represents the progression from raw data to research findings. The derived grounded theory model that shows the dynamic relationships between the emergent concepts and clarifies the relevant data-to-theory connections is depicted in a box-and-arrow graph. Using the Gioia Methodology allowed us to maintain a chain of evidence (Yin, 2003), for external observers to be able to follow the derivation of evidence from the research question to the case study conclusions.

As described before, primary data was collected through semi-structured interviews with the owner-managers of three companies. Although the interviews were open, a questionnaire based on the literature review was prepared to guide the interviews and keep the focus on the research question. All the interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded. Website information, newspaper clippings, interviews in media, business plans, presentations to investors, public reports, and internal documents were used to develop the questionnaire.

4. Multiple-case study

The three firms were chosen taking into account several selection criteria. They had to be NTFBs based on emerging technologies, involved in intensive and sustained R&D efforts, and able to produce novel outputs (Cooper and Bruno, 1977; Brinckmann, Salomo, and Gemuenden, 2011). The founders had to be novice entrepreneurs. The firms had to be new ventures requiring fund-raising. By studying neophytes that required external funding, we controlled for previous start-up experience, which is a very strong signal for many investors (Gimmon and Levie, 2010). The founders had to have a technical or scientific background, with or without management education and experience (in three firms, there was one founder with management experience, one with management education, and one who had neither). The respondents had to be the founders as well as the current owner-managers of the firms. We wanted to interview individuals willing to share their personal experience in going through the entire process from the inception to the subsequent development of a NTBF, providing valuable information. All three companies have received awards, recognition, and public grants. They have raised both public and private funds.

- 4.1. WIRS

Worldwide Integral Rehabilitation Systems (WIRS), a healthcare company, has developed a web platform that allows patients to do physical rehabilitation at medical centers and at home. The platform is based on cloud computing technology and uses motion sensors and videogames. Sensors register patients’ movements and send data to the computers of doctors and physiotherapists. Therapies can be personalized and there is a reduction in healthcare provision costs.

WIRS was selected because the founder and CEO, Manuel Guerris, is an industrial engineer but also holds an MBA. He has work experience in different industries, in both marketing and sales positions. He also worked as a strategy and management consultant. He is able to talk about the difficulties he would have encountered if he had not had any business experience.

- 4.2. Sagetis Biotech

Sagetis Biotech is a drug delivery company focused on developing technologies that enable drugs to cross the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) to treat Central Nervous System (CNS) diseases. The BBB is a natural system protecting the brain from infections and other attacks. However, it hinders most drugs from entering the CNS. The market for drugs for CNS diseases is underdeveloped because the great majority of drugs do not cross the BBB. Sagetis Biotech tries to cross the BBB by means of capsules made of biodegradable polymers. To date the company has developed three platforms to solve specific problems: drug delivery, genetic material delivery, and bone tissue regeneration. Compared to other technologies, the advantage of the venture’s approach to drug delivery is its ability to transport and release a potential wide range of drugs into the brain minimizing their toxicity in other organs and tissues of the body.

Sagetis Biotech is a spin-off from GEMAT (Materials Engineering Group) at IQS (Universitat Ramon Llull). It was selected because the CEO, Eduard Diviu, is an industrial engineer but he also holds a degree in business management. He too can talk about the difficulties he would have encountered if he had not had any business education.

- 4.3. Flubetech

Flubetech develops ceramic hard coatings. Its coating technology provides objects with some desired characteristics, especially hardness, wear resistance, and low friction. These properties are needed in a variety of applications such as cutting, stamping and forming dies, plastic injection molds, cutting tools, high productivity tools and components, surgical tools, dental prosthetic components and screws.

Flubetech is also a spin-off from GEMAT (Materials Engineering Group) at IQS (Universitat Ramon Llull). It was selected because the founder and CEO, Carles Colominas, has a scientific background and track record, but no management education or experience. He can talk about the difficulties he encountered.

5. Results

The intention of this inquiry is to derive a model describing the relationships between some constructs (such as the founders’ background, the ‘technology push’ view of innovation and the role of managers in NTBFs). The research was based on primary data collected through semi-structured interviews and followed the Gioia Methodology. In this section we will explain how the findings are presented, then we will detail the main results and finally we will report other results of interest.

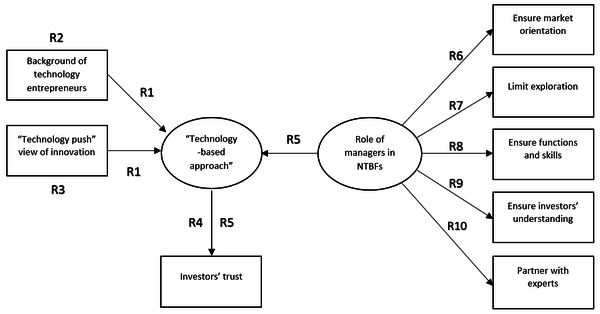

Table 2 lists the respondents’ most relevant quotations and their translation into ‘1st-order’ terms. At this stage, we kept the terms used by the respondents during the semi-structured interviews. The conversion from raw data to informant-centric terms was done by codifying the verbatim quotations. Keywords are underlined. Table 3 shows the data structure of the research. ‘1st-order’ terms from Table 2 are linked to ‘2nd-order’ themes and then to aggregate dimensions. Tables 2 and 3 allow tracking the progression from raw data to terms, themes, and dimensions. Figure 1 shows the outcome of Table 3. It depicts the dynamic relationships between the emergent concepts and makes the relevant data-to-theory connections clear.

The main results of the research are summarized in Figure 1 which depicts the model derived. The constructs and their relationships are explained in 10 statements that can be tracked in the figure: R1) the combination of the prevailing background of technology entrepreneurs and the ‘technology push’ view of innovation mostly exhibited by managers and employees in NTBFs prompts what we term a ‘technology-based approach’; R2) the background of technology entrepreneurs is characterized by a lack of management education, managerial experience, start-up competencies and financial expertise, as well as by an inability to present business plans to investors using the proper structure and vocabulary; R3) managers and employees in NTBFs may have a ‘technology push’ view of innovation due to their confinement to labs and may prioritize technology over market and customer preferences; R4) the ‘technology-based approach’ may not only undermine firm’s performance but also compromise fund-raising because investors will hardly trust a company focused on technology or a company whose founders do not possess a background in management and selling skills; R5) managers in NTBFs have a role to play in counteracting a ‘technology-based approach’ and, therefore, in dissipating investors’ distrust and preserving the firm’s performance from the negative influence of the ‘technology-based approach’; R6) they have to ensure that managers and employees have a ‘market pull’ view of innovation and that the products of the company are orientated towards the market and the consumers’ preferences; R7) they have to limit research and experimentation within the firm, restrict the exploration efforts that are the result of a ‘technology push’ view of innovation, and make the firm comply with commitments (e.g. achieve deadlines and meet budgets) thus strengthening the investors’ trust in the firm; R8) they have to ensure managers and employees accomplish their functions and possess the necessary skills within the firm; R9) they have to ensure that investors understand the firm’s business model and its cash generation mechanism and that the dialogue with them is not centered on technology; and R10) they have to select and partner with individuals with entrepreneurial expertise that have a network of contacts within the investor community.

Other results of interest obtained from the semi-structured interviews refer to fund-raising, to partnering, and to the difference between raising private and public funds.

The respondents said that attracting external funds requires having a founder or manager with managerial and financial expertise, and a network of contacts with potential investors. Individuals with managerial and financial expertise are more adept at explaining the foundations of the business without focusing on technology. Financial expertise in particular is required to answer questions about the company’s financials. A network of contacts including potential investors allows entrepreneurs to accelerate the funding process. On the other hand, investors highly value marketing and sales expertise as a signal of the firm’s market orientation. At the time of raising funds, despite having management education and prior managerial experience, Guerris (WIRS) partnered with someone with prior start-up experience. Because of his academic profile, Colominas (Flubetech) hired a former classmate with management education and prior managerial experience who also invested in the company as a business angel. Guerris (WIRS) and Colominas (Flubetech) both relied on partners and managers because they lacked financial expertise. In contrast, Diviu (Sagetis Biotech) did not count on external individuals because of his financial education.

The respondents also said that, when the founder is a neophyte, partnering with someone with knowledge about creating new ventures is advisable. Partners may contribute not only with funds but also with expertise in a variety of fields. In this regard, Guerris (WIRS) stated that novice entrepreneurs are concerned about ‘the daily problems of start-ups.’ He remarked the contribution of individuals with ‘knowledge of how to do things, of what steps to take and of how to approach investors.’ Moreover, partnering implies complementing the founders’ skills. For instance, Colominas (Flubetech), who has an academic background, partnered with someone with financial expertise.

Diviu (Sagetis Biotech) said that the skills needed to raise public funds are different from those required to raise private funds. In public fund-raising, scientists are the true actors. They participate in international projects and attend summits and conferences where trendy topics are discussed, recent breakthroughs are presented and results of ongoing clinical trials are shown. Attending these events allows technology entrepreneurs to enlarge their network of contacts, be aware of the latest novelties and the activities of the rivals, and deal with government institutions and agencies. In public fund-raising, technical evaluation of projects precedes financial evaluation. In contrast, in private fund-raising ‘you have to explain the business model, the way participants interact is different, common financial vocabulary is used, dealings are oriented toward financial issues, and you need communication skills to convince the potential investors. (…). The financial evaluation of projects dominates negotiations.’ Therefore, according to Diviu (Sagetis Biotech), managerial skills are imperative to raise private funds but not to raise public funds, because in public fund-raising the discussions are among scientists and about technical issues.

The nature of the constructs developed through the research (‘technology-based approach’ and the role of managers in NTBFs), as well as their relationship, are the essentials of the model derived from this research.

6. Discussion

In this section we will specify the nature of the constructs and we will show their relationship. We will also discuss other results of interest related to fund-raising and to the particular jobs to be performed in a NTBF.

The ‘technology-based approach’ emerges as the combination of the prevailing background of technology entrepreneurs and the ‘technology push’ view of innovation of most managers and employees in NTBFs. The background of technology entrepreneurs is characterized in the literature by a lack of commercial skills to sell the product with a market orientation (Wright et al., 2007), by a lack of financial expertise (Brinckmann, Salomo, and Gemuenden, 2011), by an inability to identify niche markets and recognize who will buy the firm’s product (Capaldo and Fontes, 2001), and by an inability to understand buyer preferences (Scillitoe and Chakrabarti, 2010). On the other hand, Sapienza and Amason (1993), Rice, Matthews, and Kilcrease (1995), Oakey (2003), and Wright et al. (2007) provide detailed accounts of the ‘technology push’ view of innovation.

The research suggests that it is the combination of the background of technology entrepreneurs and the ‘technology push’ view of innovation of managers and employees in NTBFs that prompts the ‘technology-based approach.’ A technology background and a ‘technology push’ view of innovation together would result in a ‘technology-based approach,’ while a managerial background and a ‘market pull’ view of innovation would not. The other two combinations (managerial background and ‘technology push’ view of innovation and technology background and ‘market pull’ view of innovation) are less likely to result in a ‘technology-based approach.’

This first result can be summarized as follows:

Proposition 1: The combination of the prevailing background of technology entrepreneurs and the ‘technology push’ view of innovation mostly exhibited by managers and employees in NTBFs prompts a ‘technology-based approach.’

This proposition calls for a slight reformulation of the initial research question. Instead of “How can managers counteract a ‘technology push’ view of innovation in NTBFs?”, henceforth the question to be answered is “How can managers counteract a ‘technology-based approach’ in NTBFs?”

Identifying the mentioned ‘technology-based approach’ is the first contribution of this inquiry. When reviewing the literature nothing was found on the existence of this ‘mindset’ and the way it influences decision-making in NTBFs. Searches on ‘technology-based approach’ in the literature on technology management do not refer to the kind of ‘myopia’1 technology entrepreneurs may suffer.

Managers in NTBFs must play a role in counteracting a ‘technology-based approach’ and, therefore, in dissipating investors’ distrust and preserving firm performance from the negative influence of the ‘technology-based approach.’ This managerial role is fivefold: 1) ensuring a market orientation; 2) limiting exploration; 3) ensuring accomplishment of functions and possession of skills; 4) ensuring investors understand the firm’s business model; and 5) partnering with experts. Table 3 (see ‘1st-order’ terms column) provides a description, using the respondents’ words, of the role managers in NTBFs must play to overcome the absence of the appropriate background and counteract the ‘technology mindset’ of founders and employees. This is the second contribution of this research.

Our findings are related to Man, Lau, and Chan's (2002) model of SME competitiveness that connects some entrepreneurial competencies with firm performance. The fivefold role of managers identified in NTBFs correspond to one or more of the entrepreneurial competencies of the model, as shown in Table 4.

In the model of SME competitiveness, strategic competencies and commitment competencies are directly related to firm performance while relationship competences are indirectly related to firm performance through the competitive scope and organization capabilities. Organizing competencies are indirectly related to firm performance through organization capabilities.

This second result can be summarized as follows:

Proposition 2: Managers in NTBFs have a role to play in counteracting a ‘technology-based approach’ and, therefore, in dissipating investors’ distrust and preserving firm performance from the negative influence of the ‘technology-based approach.’

Proposition 3: This managerial role is fivefold: ensuring a market orientation, limiting exploration, ensuring the accomplishment of functions and the possession of skills, ensuring investors’ understanding of the firm’s business model, and partnering with experts.

Proposition 4: The fivefold managerial role is composed of entrepreneurial competencies related to firm performance.

Our findings are also related to the replication of Mintzberg's (1973) structured observational method in the context of small growth-orientated businesses conducted by O’Gorman, Bourke, and Murray (2005). It provides an account of the managerial work in terms of Mintzberg’s 10 roles. The identified fivefold role of managers in NTBFs also corresponds to one or more of Mintzberg’s roles, as shown in Table 5.

The respondents also gave insightful accounts of fund-raising and the particular jobs to be performed in a NTBF.

Private fund-raising requires having a team member with managerial and financial expertise to explain the foundations of the business without falling into the trap of describing the technology on which the new venture is based. Marketing and sales expertise show potential investors the ability of entrepreneurs to center on the market and not on technology. One of the respondents recommended partnering with someone with start-up knowledge when the founder is a neophyte. In order to accelerate the funding process, he partnered with an entrepreneur with a track record in private fund-raising. This finding confirms a relationship between prior start-up experience, social capital, and the ability to obtain external funds (Wright et al., 2007). Therefore, having prior start-up experience or partnering with someone with knowledge of creating new ventures and a network of contacts is required to approach investors and to raise funds. It applies to both NTBFs and non-NTBFs, but taking into consideration that most NTBFs are created by engineers and scientists without any business education and prior business or start-up experience, being able to relay on an experienced entrepreneur is especially advisable for NTBFs. Moreover, companies whose founders lack prior start-up experience can partner with entrepreneurs with a track record and a network of contacts in exchange for a stake in the firm. The contribution of an experienced entrepreneur to accelerate the funding process is so valuable that it makes sense to offer him/her a major stake in the firm.

By contrast, managerial skills are imperative to raise private funds but not to raise public funds. Public fund-raising is primarily led by scientists. This finding clarifies the importance of a technical background (Colombo, Grilli, and Verga, 2007) and academic status (Gimmon and Levie, 2010) in attracting external funds. Both are mandatory in public fund-raising but not in private fund-raising. They could even be unfavorable in private fund-raising.

According to the respondents, the jobs to be performed in the early years of an NTBF and the managerial skills required to perform them can be classified into four areas: finance to attract external funds; marketing and sales to identify markets and customers and to sell the product; strategy to make decisions about the business scope, and organization to assemble and manage a team. The most critical task is selling the product with a market orientation (Wright et al., 2007), which requires recognizing who will buy the product (Capaldo and Fontes, 2001) and understanding buyer preferences (Scillitoe and Chakrabarti, 2010). However, the results indicate that knowledge about how to organize the firm (Capaldo and Fontes, 2001) and about organizing and planning (West and Noel, 2009) cannot be ignored. Entrepreneurs must know the steps to follow, the milestones to pass, the obstacles to overcome, the management issues to solve. In the words of one of the respondents, they must know ‘how to do things, what steps to take.’ Again, it applies to both technology and non-technology entrepreneurs, but particularly to the former because engineers and scientists may lack business education and prior business or start-up experience and may focus on technology rather than on market.

As mentioned in the methodology section, this research is based on semi-structured interviews with owner-managers of NTBFs because our aim was to derive a model describing the relationships between some constructs. This model should be validated using quantitative methods. We also consider two future research lines. The first one consists in examining how managers in NTBFs play their role of counteracting a ‘technology-based approach.’ More specifically, how they use their authority, power or influence to avoid focusing on technology and neglecting the market and customer preferences. The second research line intends to evaluate to what extent incubators and accelerators are currently playing a similar role in technology start-ups.

7. Conclusions

The purpose of this research was to shed new light on the role of managers in counteracting a ‘technology push’ view of innovation in NTBFs founded by engineers and scientists without start-up experience. Our aim was to answer the research question “How can managers counteract a ‘technology push’ view of innovation in NTBFs?”

The first contribution of the research is identifying the ‘technology-based approach’ that emerges as a combination of the prevailing background of technology entrepreneurs and the ‘technology push’ view of innovation mostly exhibited by managers and employees in NTBFs. This first result calls for a slight reformulation of the initial research question which has been rewritten as follows: “How can managers counteract a ‘technology-based approach’ in NTBFs?” The ‘technology-based approach’ may not only undermine firm performance but also compromises fund-raising because investors will hardly trust in a company focused on technology or in a company whose founders do not possess a background in management and selling skills.

The second contribution of the research is identifying the role that managers in NTBFs must play in counteracting a ‘technology-based approach’ and, therefore, in dissipating investors’ distrust and preserving firm performance from the negative influence of ‘technology-based approach.’

This research has an implication for engineers and scientists willing to commercially exploit a business idea conceived as an application of a particular technology.

References

Baum, J. A. C., & Silverman, B. S. (2004). Picking winners or building them? Alliance, intellectual, and human capital as selection criteria in venture financing and performance of biotechnology startups. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(3), 411–436.

Beckman, C. M., Burton, M. D., & O’Reilly, C. (2007). Early teams: the impact of team demography on VC financing and going public. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(2), 147–173.

Brinckmann, J., Salomo, S., & Gemuenden, H. G. (2011). Financial management competence of founding teams and growth of new technology-based firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(2), 217–243.

Capaldo, G., & Fontes, M. (2001). Support for graduate entrepreneurs in new technology-based firms: an exploratory study from Southern Europe. Enterprise & Innovation Management Studies, 2(1), 65–78.

Chandler, G. N., & Jansen, E. (1992). The founder’s self-assessed competence and venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 7(3), 223–236.

Colombo, M. G., & Grilli, L. (2005). Founders’ human capital and the growth of new technology-based firms: a competence-based view. Research Policy, 34(6), 795–816.

Colombo, M. G., & Grilli, L. (2010). On growth drivers of high-tech start-ups: exploring the role of founders’ human capital and venture capital. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(6), 610–626.

Colombo, M. G., Grilli, L., & Verga, C. (2007). High-tech start-up access to public funds and venture capital: evidence from Italy. International Review of Applied Economics, 21(3), 381–402.

Colombo, M. G., & Piva, E. (2008). Strengths and weaknesses of academic startups: a conceptual model. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 55(1), 37–49.

Cooper, A. C., & Bruno, A. V. (1977). Success among high technology firms. Business Horizons, 20(2), 16–22.

Criaco, G., Minola, T., Migliorini, P., & Serarols-Tarrés, C. (2014). “To have and have not”: Founders’ human capital and university start-up survival. Journal of Technology Transfer, 39(4), 567–593.

Ganotakis, P. (2012). Founders’ human capital and the performance of UK new technology based firms. Small Business Economics, 39(2), 495–515.

Gimmon, E., & Levie, J. (2010). Founder’s human capital, external investment, and the survival of new high-technology ventures. Research Policy, 39(9), 1214–1226.

Gioia, D. a., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2012). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31.

Man, T. W. ., Lau, T., & Chan, K. . (2002). The competitiveness of small and medium enterprises. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(2), 123–142.

Mintzberg, H. (1973). The nature of managerial work. New York: Harper & Row.

Murray, G. (1996). A synthesis of six exploratory, European case studies of successfully exited, venture capital-financed, new technology-based firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 20(4), 41–60.

O’Gorman, C., Bourke, S., & Murray, J. A. (2005). The nature of managerial work in small growth-orientated businesses. Small Business Economics, 25(1), 1–16.

Oakey, R. (2003). Technical entrepreneurship in high technology small firms: some observations on the implications for management. Technovation, 23(8), 679–688.

Patzelt, H. (2010). CEO human capital, top management teams, and the acquisition of venture capital in new technology ventures: an empirical analysis. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 27(3–4), 131–147.

Rice, M. P., Matthews, J. B., & Kilcrease, L. (1995). Growing new ventures, creating new jobs. Quorum.

Roberts, E. B. (1991). Entrepreneurs in high technology: lessons from MIT and beyond. Oxford University Press.

Sapienza, H. J., & Amason, A. C. (1993). Effects of innovativeness and venture stage on venture capitalist-entrepreneur relations. Interfaces, 23(6), 38–51.

Scillitoe, J. L., & Chakrabarti, A. K. (2010). The role of incubator interactions in assisting new ventures. Technovation, 30(3), 155–167.

Song, M., Podoynitsyna, K., Van Der Bij, H., & Halman, J. I. M. (2008). Success factors in new ventures: a meta-analysis. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 25(1), 7–27.

Vesper, K. H. (1990). New venture strategies. Prentice Hall.

Welter, C., Bosse, D. A., & Alvarez, S. A. (2013). The interaction between managerial and technological capabilities as a determinant of company performance: an empirical study of biotech firms. International Journal of Management, 30(1), 272–284.

West, G. P., & Noel, T. W. (2009). The impact of knowledge resources on new venture performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(1), 1–22.

Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2003). Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses. Strategic Management Journal, 24(13), 1307–1314.

Willard, G. E., Krueger, D. A., & Feeser, H. R. (1992). In order to grow, must the founder go: a comparison of performance between founder and non-founder managed high-growth manufacturing firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 7(3), 181–194.

Wright, M., Hmieleski, K. M., Siegel, D. S., & Ensley, M. D. (2007). The role of human capital in technological entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(6), 791–806.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: design and methods. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Yli-Renko, H., Autio, E., & Sapienza, H. J. (2001). Social capital, knowledge acquisition, and knowledge exploitation in young technology-based firms. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7), 587–613.

Zucker, L. G., Darby, M. R., & Brewer, M. B. (1998). Intellectual human capital and the birth of U.S. biotechnology enterprises. American Economic Review, 88(1), 290–306.

Table 1. Characteristics of founders’ background influencing external fund-raising.

| Authors | Characteristics of founders’ background |

| Beckman, Burton, and O’Reilly (2007) | Team composition, having worked for different companies in different functions |

| Brinckmann, Salomo, and Gemuenden (2011) | Entrepreneurial skills, social capital, similarity with investors |

| Colombo, Grilli, and Verga (2007) | Economics-managerial education, managerial experience |

| Gimmon and Levie (2010) | Business management expertise, academic status |

| Patzelt (2010) | Management education, firm-specific experience, industry-specific experience, international experience |

| Wright et al. (2007) | Prior start-up experience, social capital |

Table 2. From raw data to informant-centric terms.

| INFORMANTS’ QUOTATIONS | ‘1ST-ORDER’ TERMS |

| ‘Pure engineers are not concerned about the market’ (Guerris, WIRS).

‘Pure engineers just pay attention to technology, and most of the time technology does not fit customers’ preferences’ (Guerris, WIRS). ‘Creating and harvesting a new venture is beyond the competences of a pure engineer. (…). All these issues are too much for an engineer, unless he has management education or managerial experience, or has partnered with someone’ (Guerris, WIRS). ‘Scientists are focused on their technical role. Sometimes they are stuck in their field and live confined in their labs. A product can be perfect for the scientist but useless for the market’ (Diviu, Sagetis Biotech). |

* Pure engineers lack management education and managerial experience

* Pure engineers lack start-up competencies * Scientists are confined in their labs * Pure engineers pay more attention to technology than to the market and to customer preferences * Technology products may not fit customers’ preferences |

| ‘I have stopped works in my company several times because they [employees with a technical background] were just experimenting and were not focused’ (Guerris, WIRS).

‘Scientists need to be complemented by managers when making decisions about how to invest the funds received. Managers are focused on achieving the deadlines and meeting the budgets. Scientists tend to be more careless with time and budget’ (Diviu, Sagetis Biotech). ‘My leadership consists of saying ‘stop’ in discussions about new applications and new sectors; of questioning whether there is a true market opportunity or, in contrast, we are looking for a market for our lab experiments; of recalling employees that the company only manufactures and sells, and that research must be done within the university research group. The research group is devoted to exploring and the spin-off to exploiting’ (Colominas, Flubetech). |

* Companies should focus on exploitation (e.g. manufacture and sales)

* Exploration (e.g. research and experimentation) should be done outside the company (e.g. at university) * Managers must stop exploration * Investment decisions should be made by managers and scientists together * Managers achieve deadlines and meet budgets while scientists do not |

| Evaluate the market potential; identify market niches; formulate a strategy; assemble a team; decide on a revenue model, a price policy, and a distribution channel; assemble a sales force; prioritize; present the project to potential investors and explain cash generation; sell the product to the market and the project to investors (Guerris, WIRS).

Determine the proper financial structure, the equilibrium between equity, debt, and grants (Diviu, Sagetis Biotech). Decide what application to pursue, what products or services to launch, what customers to target, what industries to supply; ‘know exactly where we lose money’ (Colominas, Flubetech). ‘My concerns are (…) working hard but not earning money, making mistakes and not being aware of them… [We need] to know where we spend our money, [to] known in advance whether we will have a cash problem…’ (Colominas, Flubetech). |

* Jobs to be done: marketing, product development, strategy making, team making, cash generation, funding, control |

| ‘Communication skills are needed to sell products and interacting with investors is required to raise funds’ (Guerris, WIRS).

‘Expertise about how to do things, what steps to take, how to approach investors’ (Guerris, WIRS). ‘[Investors] require the possession of selling skills’ (Guerris, WIRS). ‘Communication skills are required to participate in partnering events [such as investment forums]. (…). It is about ‘selling’ a project and answering questions by chatting with investors’ (Diviu, Sagetis Biotech). |

* Skills to possess: communication and selling skills to sell products and raise funds, and start-up expertise |

| ‘Investors will not invest if the entrepreneur is a pure engineer, unless he or she has management education or prior managerial experience. Lack of marketing and sales expertise is problematic. Selling skills are critical. (…). Investor’s confidence requires a ‘commercial’ profile’ (Guerris, WIRS).

‘Possessing a background in management is essential to lead funding rounds. Investors expect to find someone able to explain to them more than the venture’s technology. They want to understand the basis of the firm. Therefore, having a founder or manager in control of the financials of the new venture is a condition for success’ (Diviu, Sagetis Biotech). ‘Investors are aware that most of the technology entrepreneurs do not possess financial expertise, and tightly monitor the company’s financials. (…). If investors realize that you need a person in charge of finance, they will tell you to hire someone and will help you to recruit him or her’ (Diviu, Sagetis Biotech). |

* Pure engineers lack financial expertise

* The investors’ trust in the company depends on the founders’ management background * The investors’ trust in the company depends on the selling skills of founders * Investors need to understand the business, not the technology |

| ‘A pure engineer will not be able to present the project to potential investors and explain financial issues as cash generation. Presentations have to be formally structured and entrepreneurs must answer investors’ questions adequately. It is also a matter of vocabulary’ (Guerris, WIRS).

‘Negotiations with business angels or venture capitalists must be conducted by people with prior managerial experience and financial background’ (Diviu, Sagetis Biotech). ‘The business plan is the tool to raise funds from private investors. You must be rigorous in providing them with data because they are financial experts’ (Diviu, Sagetis Biotech). ‘You have to communicate financial information, more than technical information’ (Diviu, Sagetis Biotech). ‘For more than two years, he [the former classmate who served in the company as a manager and also invested as a business angel] was in charge of developing business plans constantly to get grants, loans, and equity. His role was crucial to raise funds. Without his contribution…’ (Colominas, Flubetech). ‘Negotiations with potential investors are directly held by me. We [Colominas and his partner] present the project and are the company’s spokesmen’ (Colominas, Flubetech). |

* Pure engineers cannot present business plans to investors

* Fund raising requires a background in management and finance * Presentations should use certain structure and vocabulary * Investors need to understand cash generation * Investors need to understand the financials, not the technology * Investors expect to deal with founders |

| ‘Fund-raising is different depending on whether funds are public or private. Managerial skills are not needed to raise public funds, because the negotiations are among scientists and about technical issues’ (Diviu, Sagetis Biotech). | * Raising public funds requires technology skills rather than managerial skills |

| Do an MBA or attend seminars (Guerris, WIRS).

‘Find someone to help me in exchange for a stake in the firm’ (Guerris, WIRS). ‘I partnered with someone who had previously experienced the entire entrepreneurial process’ (Guerris, WIRS). ‘He [the partner] had a network of contacts. If you do not know investors, you must attend [investment] forums. Learning the rules of the game of forums is time-consuming. You lose a lot of time preparing the presentations and meeting with investors. Entrepreneurs with a track record can skip forums because they know investors. By meeting with prior contacts, the process can go faster’ (Guerris, WIRS). ‘A person devoted full-time to raising funds deserves a 50% ownership’ (Guerris, WIRS). ‘If founders have a pure technical background, it is far better to hire someone or partner with someone, rather than doing a ‘compressed’ MBA program or attending ‘ad hoc’ seminars’ (Guerris, WIRS). ‘At the time of developing the financial plan, I was assisted by my venture capitalists and by consultancy firms’ (Diviu, Sagetis Biotech). ‘Entrepreneurs with a technical background could learn about management, but it is far better to have someone with the profile on board from scratch’ (Diviu, Sagetis Biotech). ‘If the founder does not possess managerial skills, he or she can partner with someone. In order to have them completely involved, partners must be shareholders since the beginning rather than just being employees. People who contribute with equity take more responsibilities’ (Diviu, Sagetis Biotech). ‘We needed someone with managerial skills because the two founders have a technical background. We partnered with a former classmate who earned a degree and a doctorate in chemistry and also did an MBA program. He had a management position in a company. He also invested in the new venture as a business angel’ (Colominas, Flubetech). ‘I have considered many times the possibility of doing a training program in management. I am sure that a program would help me. I would learn a lot. But I have no time’ (Colominas, Flubetech). |

* Lack of managerial skills can be solved by management education

* Entrepreneurs have no time for education * Lack of managerial skills can be solved by partnering with someone with entrepreneurial expertise * Lack of managerial skills can be solved by partnering with someone with managerial experience * A partner should bring his or her network of contacts (investors) |

Table 3. Data structure.

| ‘1ST-ORDER’ TERMS | ‘2ND-ORDER’ THEMES | AGGREGATE DIMENSIONS |

| * Pure engineers lack management education and managerial experience

* Pure engineers lack start-up competencies * Pure engineers lack financial expertise * Pure engineers cannot present business plans to investors * Presentations should use a certain structure and vocabulary |

Background of technology entrepreneurs | ‘Technology-based approach’ |

| * Scientists are confined in their labs

* Pure engineers pay more attention to technology than to the market and to customer preferences |

‘Technology push’ view of innovation | |

| * Technology products may not fit customer preferences | Ensure market orientation | Role of managers in NTBFs |

| * Companies should focus on exploitation (e.g. manufacture and sales)

* Exploration (e.g. research and experimentation) should be done outside the company (e.g. at university) * Managers must stop exploration * Managers achieve deadlines and meet budgets while scientists do not |

Limit exploration | |

| * Jobs to be done: marketing, product development, strategy making, team making, cash generation, funding, control

* Skills to possess: communication and selling skills to sell products and raise funds, and start-up expertise * Investment decisions should be made by managers and scientists together * Fund raising requires a background in management and finance |

Ensure (accomplishment of) functions and (possession of) skills | |

| * The investors’ trust in the company depends on the founders’ background in management

* The investors’ trust in the company depends on the selling skills of founders * Investors expect to deal with founders |

Investors’ trust | ‘Technology-based approach’ |

| * Investors need to understand the business, not the technology

* Investors need to understand the financials, not the technology * Investors need to understand cash generation |

Ensure investors’ understanding (of the firm’s business model) | Role of managers in NTBFs |

| * Lack of managerial skills can be solved by management education

* Entrepreneurs have no time for education * Lack of managerial skills can be solved by partnering with someone with entrepreneurial expertise * Lack of managerial skills can be solved by partnering with someone with managerial experience * A partner should bring his or her network of contacts (investors) |

Partner with experts |

Figure 1. Dynamic relationships between concepts.

Table 4. Fivefold role of managers in NTBFs and entrepreneurial competencies in the model of SME competitiveness.

| Fivefold role of managers in NTBFs | Entrepreneurial competencies in the model of SME competitiveness |

| Ensure market orientation | Strategic competencies, commitment competencies |

| Limit exploration | Commitment competencies |

| Ensure (accomplishment of) functions and (possession of) skills | Organizing competencies |

| Ensure investors’ understanding (of business model) | Relationship competencies |

| Partner with experts | Relationship competencies |

Table 5. Fivefold role of managers in NTBFs and Mintzberg’s roles.

| Fivefold role of managers in NTBFs | Mintzberg’s roles |

| Ensure market orientation | Leader, Monitor, Entrepreneurial, Figurehead |

| Limit exploration | Leader, Monitor, Resource Allocator, Figurehead, |

| Ensure (accomplishment of) functions and (possession of) skills | Leader, Monitor, Entrepreneurial, Resource Allocator |

| Ensure investors’ understanding (of business model) | Liaison, Spokesman, Negotiation |

| Partner with experts | Leader, Monitor, Entrepreneurial, Liaison, Resource Allocator, Figurehead, Spokesman, Negotiation |

(1) We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer who suggested this term.