Abstract

The global trend towards urbanisation explains the growing interest in the study of the modification of the urban climate due to the heat island effect and global warming, and its impact on energy use of buildings. Also urban comfort, health and durability, referring respectively to pedestrian wind/thermal comfort, pollutant dispersion and wind-driven rain are of interest. Urban Physics is a well-established discipline, incorporating relevant branches of physics, environmental chemistry, aerodynamics, meteorology and statistics. Therefore, Urban Physics is well positioned to provide key-contributions to the current urban problems and challenges. The present paper addresses the role of Urban Physics in the study of wind comfort, thermal comfort, energy demand, pollutant dispersion and wind-driven rain. Furthermore, the three major research methods applied in Urban Physics, namely field experiments, wind tunnel experiments and numerical simulations are discussed. Case studies illustrate the current challenges and the relevant contributions of Urban Physics.

Abbreviations

ABL , atmospheric boundary layer ; CFD , computational fluid dynamics ; LES , large eddy simulation ; RANS , Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes ; WDR , wind-driven rain

Keywords

Field experiments ; Wind tunnel experiments ; Numerical simulations ; Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) ; Wind comfort ; Thermal comfort ; Energy demand ; Pollutant dispersion ; Wind-driven rain

1. Introduction

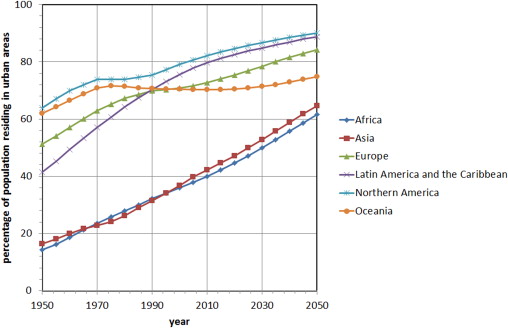

1.1. Trend towards urbanisation

As of 2010, more than half of the worlds population is living in towns or cities (United Nations, 2010 ). The number of urban dwellers rose from 729 million in 1950 to 3.5 billion in 2010. Over the same time period, the total population has increased from 2.5 billion to 6.9 billion. Current projections by the United Nations assume that this growth continues (United Nations, 2010 ). By 2045, every two out of three persons are expected to live in urbanized areas, corresponding to 5.9 billion people. Over the past decades, urbanisation mainly took place in Europe and the US, while nowadays, the centre of urbanisation moved to Asia as consequence of their rapid economic growth (Figure 1 ).

|

|

|

Figure 1. Percentage of population residing in urban areas by continent 1950–2050 (based on data from United Nations (2010) ). |

1.2. Urban heat island

Urbanisation necessitates expansion of the cities' boundaries, as well as densification of the urban tissue. The latter often results in the construction of tall building structures along relatively narrow streets. As a consequence of the altered heat balance, the air temperatures in densely built urban areas are generally higher than in the surrounding rural hinterland, a phenomenon known as the “urban heat island”. The heat island is the most obvious climatic manifestation of urbanisation (Landsberg, 1981 ).

Possible causes for the urban heat island were suggested by Oke (1982) and their relative importance was determined in numerous follow-up studies:

- Trapping of short and long-wave radiation in between buildings.

- Decreased long-wave radiative heat losses due to reduced sky-view factors.

- Increased storage of sensible heat in the construction materials.

- Anthropogenic heat released from combustion of fuels (domestic heating, traffic).

- Reduced potential for evapotranpiration, which implies that energy is converted into sensible rather than latent heat.

- Reduced convective heat removal due to the reduction of wind speed.

In other than extreme thermal climates, the heat island effect can largely be explained by a combination of the first three causes (Oke et al., 1991 ).

Studies of the urban heat island usually refer to the heat island intensity, which is the maximum temperature difference between the city and the surrounding area. The intensity is mainly determined by the thermal balance of the region, and is consequently subject to diurnal variations and short-term weather conditions (Santamouris, 2001 ). Santamouris (2001) compiled data from a large number of heat island studies worldwide. He reports heat island intensities for European cities ranging between 2.5 °C (London, UK) and 14 °C (Paris, France), for American cities ranging between 2 °C (Sao Paulo, Brasil) and 10.1 °C (Calgary, Alberta), for Asian cities ranging between 1 °C (Singapore) and 10 °C (Pune, India), and for African cities ranging between 1.9–2 °C (Johannesburg, South Africa) and 4 °C (Cairo, Egypt). The IPCC has compiled data from various sources and found heat island intensities ranging from 1.1 °C up to 6.5 °C (IPCC, 1990 ).

The urban heat island is not necessarily detrimental, especially in cold climates (Erell et al., 2011 ). However, in warm-climate cities, heat islands can seriously affect the overall energy consumption of the urban area, as well as the comfort and health of its inhabitants. Climatic measurements from almost 30 urban and suburban stations, as well as specific measurements performed in 10 urban canyons in Athens, Greece, revealed a doubling of the cooling load of urban buildings and a tripling of the peak electricity load for cooling, while the minimum COP value of air conditioners may be decreased up to 25% because of the higher ambient temperatures (Santamouris et al., 2001 ). In the same study it was shown that the potential of natural ventilation was significantly reduced because of the important decrease of the wind speed in the urbanized area. The only positive impact was a 30% reduction of the energy demand for space heating during the winter period. Similar conclusions were reported in Shimoda (2003) for the city of Osaka, Japan. Besides affecting the energy demand, increased air temperatures also lead to thermal stress. Thermal stress not only causes discomfort, but may also lead to reduced mental and physical performance and to physiological and behavioural changes (Evans, 1982 ). The physiological changes range from vasodilatation and sweating, over faintness, nausea and headache, up to heat strokes, heart attacks and eventually death. The performance and behavioural changes are only evident under extreme conditions, while under intermediate conditions a unique causal relation still needs to be established.

A significant amount of research is directed towards the mitigation of the undesired consequences of the urban heat island. One way to mitigate the excess heat is to make use of evaporative cooling, for example from ground-level ponds (Krüger and Pearlmutter, 2008 ) and roof ponds (Runsheng et al ., 2003 ; Tiwari et al ., 1982 ), from surfaces wetted by wind-driven rain (Blocken and Carmeliet, 2004b ; Blocken et al ., 2007c ), or from vegetated surfaces (Alexandri and Jones, 2008 ). Alternatively one can try to control the amount of solar gains, e.g. by applying high-albedo (i.e. reflective) materials, especially at horizontal surfaces (Erell et al., 2011 ). For novel urban developments, the shape and location of building volumes can be designed in order to control and optimise solar access.

1.3. Climate change

Despite being extremely important, the urban heat island is a localised phenomenon and does not significantly contribute to the observed large-scale trends of climate change (Solomon et al., 2007 ). The inverse statement is however not true: global climate change will add an additional thermal burden to urban areas, accentuating urban heat island impacts (Voogt, 2002 ).

According to the most recent IPCC report (Solomon et al., 2007 ), warming of the climate system is unequivocal. It can be observed by the increase in global average air and ocean temperatures, the widespread melting of snow and ice and the rise of the global average sea level. They state that the observed increase in global average temperatures since the mid-20th century can most likely be attributed to the increase in anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations. As global greenhouse gas emissions are expected to continue to grow, a warming of about 0.2 °C per decade is projected for the next two decades, after which temperature projections increasingly depend on specific emission scenarios (Solomon et al., 2007 ). The report also discusses the potential impacts of the continuing temperature rise. They include amongst others (i) increases in frequency of hot extremes, heat waves and heavy precipitation, (ii) increases in precipitation in high latitudes and precipitation decreases in most subtropical land regions, and (iii) contraction of snow cover area and corresponding sea level rise. Asian and African megadeltas, as well as the African content, are expected to suffer the most from these consequences. Nevertheless, also within other areas, even those with high incomes, some people (such as the poor, young children and the elderly) can be particularly at risk.

1.4. Major urban problems and challenges

From the preceding, it is clear that the combined effects of urbanisation and global climate warming can give rise to a decrease in urban air quality and an increase in urban heat island intensity, amplifying the risk to expose the citizens to discomfort and health-related problems, and leading to higher energy demands for cooling. In assessing these aspects, it is needed to consider a wide scope of phenomena, occurring over a wide range of spatial scales. The individual building with its technical installation marks one end of the spectrum. At increasingly larger scales we have the effect of the urban morphology at neighbourhood scale, the urban heat island effect at city-scale, the effect of topography at regional scale and finally the global effects of climate and climate change.

1.5. Urban Physics

Urban Physics is a well-established discipline, incorporating relevant branches of physics, environmental chemistry, aerodynamics, meteorology and statistics. Therefore, Urban Physics is well positioned to provide key-contributions to the existing urban problems and challenges. The present paper addresses the role of Urban Physics in the study of wind comfort (Section 2 ), thermal comfort (Section 3 ), energy demand (Section 4 ), pollutant dispersion (Section 5 ) and wind-driven rain (Section 6 ). Furthermore, the three major research methods applied in Urban Physics, namely field experiments, wind tunnel experiments and numerical simulations are discussed (Section 7 ).

2. Urban wind comfort

2.1. Problem statement

High-rise buildings can introduce high wind speed at pedestrian level, which can lead to uncomfortable or even dangerous conditions. Wise (1970) reports about shops that are left untenanted because the windy environment discouraged shoppers. Lawson and Penwarden (1975) report the death of two old ladies due to an unfortunate fall caused by high wind speed at the base of a tall building. Today, many urban authorities only grant a building permit for a new high-rise building after a wind comfort study has indicated that the negative consequences for the pedestrian wind environment remain limited.

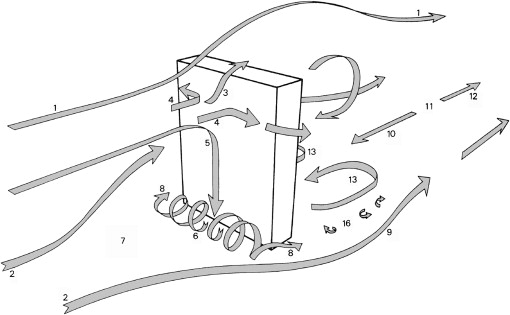

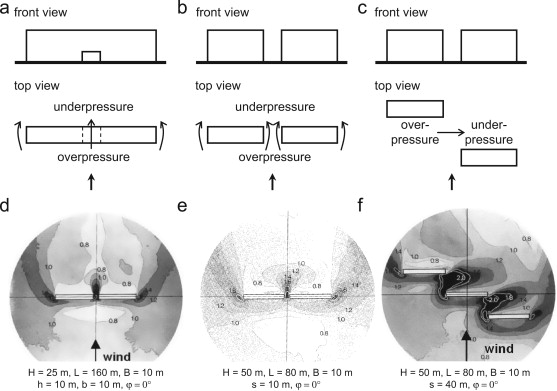

The high wind speed conditions at pedestrian level are caused by the fact that high-rise buildings deviate wind at higher elevations towards pedestrian level. The wind-flow pattern around a building is schematically indicated in Figure 2 . The approaching wind is partly guided over the building (1,3), partly around the vertical edges (2,4), but the largest part is deviated to the ground-level, where a standing vortex develops (6) that subsequently wraps around the corners (8) and joins the overall flow around the building at ground level (9). The typical problem areas where high wind speed occurs are the standing vortex and the corner streams. Further upstream, a stagnation region with low wind speed is present (7). Downstream of the building, complex and strongly transient wind-velocity patterns develop, but these are generally associated with lower wind speed values and are of less concern (10–16). Based on an extensive review of the literature, Blocken and Carmeliet (2004a) identified three other typical problem situations, which are schematically indicated in Figure 3 . In all three cases, the increased wind speed is caused by so-called pressure short-circuiting, i.e. the connection between high-pressure and low-pressure areas. Figure 3 a shows a passage through a building (gap or through-passage), which can lead to very strong amplifications of wind speed, up to a factor 2.5–3 compared to free-field conditions (Figure 3 d). Figure 3 (b) shows a passage between two buildings. Wind speed in the passage is increased due to the two corner streams from both buildings that merge together in the passage. Amplification factors up to 2 can be obtained this way (Figure 3 e). Figure 3 (c) finally shows a passage between two shifted parallel buildings. In this case, a rather large area of increased wind speed can occur between the buildings, with amplification values up to 2 (Figure 3 f).

|

|

|

Figure 2. Schematic representation of wind flow pattern around a high-rise building (Beranek and van Koten, 1979 ). |

|

|

|

Figure 3. Schematic representation of three situations in which increased wind speed can occur due to pressure-short circuiting: (a) passage through a building; (b) passage between two parallel buildings; (c) passage between two parallel shifted buildings (sketch after Blocken and Carmeliet, 2004a ). (d–f) show the corresponding amplification factors as obtained by means of wind tunnel testing (Beranek and Van Koten, 1979 ; Beranek, 1984b ; Beranek, 1982 ). |

2.2. Methodology

A distinction needs to be made between methods to assess pedestrian-level wind conditions (mean wind speed and/or turbulence intensity), and methods to assess pedestrian-level wind comfort and wind danger.

2.2.1. Pedestrian-level wind conditions

Pedestrian-level wind conditions around buildings and in urban areas can be analysed by on-site measurements, by wind tunnel measurements or by CFD. Wind tunnel studies of pedestrian-level wind conditions are focused on determining the mean wind speed and turbulence intensity at pedestrian height (full scale height 1.75 or 2 m). Wind tunnel tests are generally point measurements with Laser Doppler Anemometry (LDA) or Hot Wire Anemometry (HWA). In the past, also area techniques such as sand erosion (e.g. Beranek and Van Koten, 1979 ; Beranek, 1982 ; Beranek, 1984a ; Beranek, 1984b ; Livesey et al ., 1990 ; RichardsPlease check the maintitle in Ref. (Richards et al., 2002) and correct if necessary. et al., 2002 ) and infrared thermography (e.g. Yamada et al ., 1996 ; Wu and Stathopoulos, 1997 ; Sasaki et al ., 1997 ) have been used. They are however considered less suitable to obtain accurate quantitative information. Instead, they can be used as part of a two-step approach: first an area technique is used to qualitatively indicate the most important problem locations, followed by accurate point measurements at these most important locations (Blocken and Carmeliet, 2004a ).

One of the main advantages of CFD in pedestrian-level wind comfort studies is avoiding this time-consuming two-step approach by providing whole-flow field data. In spite of its deficiencies, steady RANS modelling with the k –ε model or with other turbulence models has become the most popular approach for pedestrian-level wind studies. Two main categories of studies can be distinguished: (1) fundamental studies, which are typically conducted for simple, generic building configurations to obtain insight in the flow behaviour, for parametric studies and for CFD validation, and (2) applied studies, which provide knowledge of the wind environmental conditions in specific and often much more complex case studies. Fundamental studies – beyond the case of the isolated building – were performed by several authors including Baskaran and Stathopoulos (1989) ; Bottema (1993) ; Baskaran and Kashef (1996) ; Franke and Frank (2005) ; Yoshie et al. (2007) ; Blocken et al ., 2007b ; Blocken et al ., 2008b ; Blocken and Carmeliet (2008) ; Tominaga et al. (2008a) and Mochida and Lun (2008) . Apart from these fundamental studies, also several CFD studies of pedestrian wind conditions in complex urban environments have been performed (e.g. Murakami, 1990 ; Gadilhe et al ., 1993 ; Takakura et al ., 1993 ; Stathopoulos and Baskaran, 1996 ; Baskaran and Kashef, 1996 ; He and Song, 1999 ; Ferreira et al ., 2002 ; RichardsPlease check the maintitle in Ref. (Richards et al., 2002) and correct if necessary. et al., 2002 ; Miles and Westbury, 2002 ; Westbury et al ., 2002 ; Hirsch et al ., 2002 ; Blocken et al ., 2004 ; Yoshie et al ., 2007 ; Blocken and Carmeliet, 2008 ; Blocken and Persoon, 2009 ; Blocken et al ., 2012 ). Almost all these studies were conducted with the steady RANS approach and a version of the k–ε model. An exception is the study by He and Song (1999) who used LES.

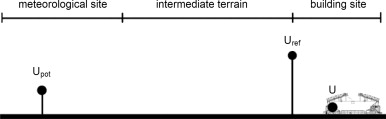

2.2.2. Pedestrian-level wind comfort and wind danger

Assessment of wind comfort and wind danger involves a more extensive methodology in which statistical meteorological data are combined with aerodynamic information and with a comfort criterion. The aerodynamic information is needed to transform the statistical meteorological data from the weather station to the location of interest at the building site, after which it is combined with a comfort criterion to evaluate local wind comfort. The aerodynamic information usually consists of two parts: the terrain-related contribution and the design-related contribution. The terrain-related contribution represents the change in wind statistics from the meteorological site to a reference location near the building site (see Figure 4 : transformation from potential wind speed Upot to reference wind speed Uref ). The design-related contribution represents the change in wind statistics due to the local urban design, i.e. the building configuration (Uref to local wind speed U ). Different transformation procedures exist to determine the terrain-related contribution; they often employ a simplified model of the atmospheric boundary layer such as the logarithmic mean wind speed profile. The design-related contribution (i.e. the wind flow conditions around the buildings at the building site) can be obtained by wind tunnel modelling or by CFD.

|

|

|

Figure 4. Schematic representation of the wind speed at the meteorological station (Upot ), the reference wind speed at the building site (Uref ) and the wind speed at the location of interest (U) (Blocken and Persoon, 2009 ). |

CFD has been employed on a few occasions in the past as part of wind comfort assessment studies (e.g. RichardsPlease check the maintitle in Ref. (Richards et al., 2002) and correct if necessary. et al., 2002 ; Hirsch et al ., 2002 ; Blocken et al ., 2004 ; Blocken and Carmeliet, 2008 ; Blocken and Persoon, 2009 ; Blocken et al ., 2012 ). The use of CFD for studying the pedestrian wind conditions in complex urban configurations is receiving strong support from several international initiatives that specifically focus on the establishment of guidelines for such simulations (Franke et al ., 2004 ; Franke et al ., 2007 ; Franke et al ., 2011 ; Yoshie et al ., 2007 ; Tominaga et al ., 2008b ) and from review papers summarizing past achievements and future challenges (e.g. Stathopoulos, 2002 ; Blocken and Carmeliet, 2004a ; Blocken and Carmeliet, 2004b ; Franke et al ., 2004 ; Mochida and Lun, 2008 ; Blocken et al ., 2011b ). Recently, Blocken et al. (2012) developed a general decision framework for CFD simulation of pedestrian wind comfort and wind safety in urban areas.

To remove the large uncertainty in studies of wind comfort and wind danger due to the use of different sets of statistical data, different terrain-related transformation procedures and different comfort and danger criteria, a standard for wind comfort and wind danger (NEN 8100) and a new practice guideline (NPR 6097) have been developed in the Netherlands (NEN, 2006a ; NEN, 2006b ) based on research work by Verkaik, 2000 ; Verkaik, 2006 ; Willemsen and Wisse, 2002 ; Willemsen and Wisse, 2007 ; Wisse and Willemsen (2003) ; Wisse et al. (2007) , and others. This is – to the best of our knowledge – the first and, at the time of writing this paper, still the only standard on wind comfort and wind danger in the world. The standard and guideline contain a verified transformation model for the terrain-related contribution. The standard explicitly allows the user to choose between wind tunnel modelling and CFD to determine the design-related contribution, but requires a report specifying details of the employed wind tunnel or CFD procedure, as a measure to achieve a minimum level of quality assurance. In relation to this new standard, Willemsen and Wisse (2007) state that research and demonstration projects are needed. The first published demonstration project was conducted by Blocken and Persoon (2009) , and is briefly outlined in the next section. A later demonstration project was published by Blocken et al. (2012) .

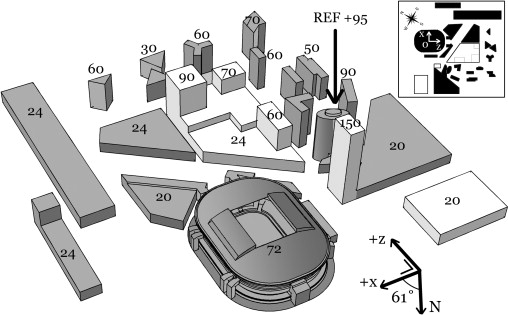

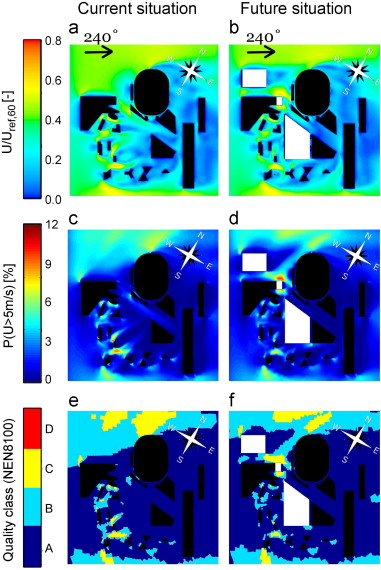

2.3. Case study

The “Amsterdam ArenA” (Figure 5 ) is a large multifunctional stadium located in the urban area of south-east Amsterdam. The new urban master plan of the site aims to erect several high-rise buildings in the stadium vicinity. The current situation is indicated by the grey buildings in Figure 5 . The newly planned buildings are indicated in white. The addition of these new buildings raises questions about the future wind comfort at the streets and squares surrounding the stadium. To assess wind comfort in the current and in the new situation, an extensive study was performed. This study included on-site wind speed measurements, CFD simulations, validation of the CFD simulations with the measurements and application of the Dutch wind nuisance standard. The CFD simulations were performed with 3D steady RANS and the realisable k –ε model, on a high-resolution grid that was constructed using the body-fitted grid generation technique developed by van Hooff and Blocken (2010a) . These simulations were successfully validated based on the wind speed measurements. For the details of the study, the reader is referred to (Blocken and Persoon, 2009 ). Figure 6 shows the main results of the study. Figure 6 a and b display contours of the mean wind-velocity ratio U /Uref,60 for wind direction 240°. U is the local wind speed at 1.75 m height and Uref,60 is the reference free-field wind speed at 60 m height, which is used in the Dutch Standard. Figure 6 (a) shows the present situation, and Figure 6 (b) the situation with newly planned buildings. The addition of the new high-rise tower building with height 150 m clearly yields a strong increase in velocity ratio at the west side of the stadium. When these data, for 12 different wind directions, are combined with the wind statistics, the transformation model and the wind comfort criteria, Figure 6 (c) and (d) are obtained. They show the exceedance probability of the 5 m/s discomfort threshold. Also here, the negative impact of the new high-rise tower is clear. Finally, these probabilities are converted into quality classes (Figure 6 (e) and (f)). The main conclusion of the study is that the addition of the high-rise tower has the largest impact. In the present situation, the quality class A at the west side of the stadium refers to a good wind climate for sitting, strolling and walking. However, in the new situation, this area is partly converted to quality class B or C, where C is considered a bad wind climate for sitting, a moderate wind climate for strolling and a sufficiently good wind climate for walking.

|

|

|

Figure 5. Amsterdam ArenA football stadium and surrounding buildings in a 300 m radius around the stadium. Blocks in grey: current situation; blocks in white: newly planned buildings. The reference measurement position (ABN-Amro tower) and the height (in meter) of each building are indicated (Blocken and Persoon, 2009 ). |

|

|

|

Figure 6. (a and b) Amplification factor U/Uref,60 ; (c and d) exceedance probability P ; and (e and f) quality class. All values are taken in a horizontal plane at 2 m above ground-level. Left: current situation; right: situation with newly planned buildings (Blocken and Persoon, 2009 ). |

This study, to our knowledge, is the first published demonstration project based on the Dutch wind nuisance standard. Apart from the validation of the CFD simulations, the further development of this standard would benefit from validation by comparison with local surveys on the perception of wind comfort or wind nuisance itself.

3. Urban thermal comfort

3.1. Problem statement

Thermal comfort is closely related to wind comfort, since wind plays a crucial role in the comfort sensation (e.g. Blocken and Carmeliet, 2004a ; Stathopoulos, 2006 ; Mochida and Lun, 2008 ). Additionally, outdoor thermal comfort is governed by both direct and diffuse solar irradiation, the exchange of long-wave radiation between a person and the environment, as well as the air temperature and humidity. Since the weather parameters vary over time, and since the pedestrians circulate through the urban environment, understanding the dynamic response of people to varying environmental conditions is necessary in the evaluation of outdoor thermal comfort. Humans not only select their clothing and adjust their activity level to the ambient conditions, but they may also adapt on a psychological level, depending on the available choices, the environmental stimulation, the thermal history and the expectations (Nikolopoulou and Steemers, 2003 ). Outdoor thermal comfort is thus governed by numerous factors.

3.2. Methodology

A crucial element in the assessment of thermal comfort is the development of a comfort index which appropriately reflects the comfort sensation of a person in a given situation. Several indices have been proposed in literature. A concise overview is given below. A more detailed description can be found in Erell et al. (2011) .

- Predicted mean vote (PMV) and predicted percentage of dissatisfied (PPD) calculation schemes were developed by Fanger (1970) on the basis of empirical laboratory-based comfort research for indoor environments, under steady-state conditions. PMV and PPD are calculated on the basis of air temperature and humidity, mean radiant temperature and air speed, for a given activity level and clothing. The schemes are implemented in many indoor thermal comfort standards, such as ISO 7730, 2005 ; ASHRAE Standard 55, 2010 .

- The standard effective temperature (SET⁎ ) is defined as the air temperature of a reference environment in which a person has the same mean skin temperature and skin wetness as in the real situation (Gagge et al., 1986 ). For outdoor applications SET⁎ has been extended to the OUT-SET⁎ scale (Pickup and de Dear, 1999 ).

- The physiological equivalent temperature (PET) is defined as the air temperature of a reference environment in which the heat budget of the human body is balanced with the same core and skin temperature as under the complex outdoor conditions to be assessed (Höppe, 1999 ).

- The wet bulb globe temperature is a measure for heat stress, and is defined in ISO 7243 (2003) .

The physical parameters of the urban microclimate on which the comfort indices are based can be obtained from measurements (Mayer et al., 2008 , Katzscher and Thorsson, 2009 ), or by means of calculation models. The simplest approaches are based on radiation modelling of the outdoor environment (Robinson and Stone, 2005 ). Examples are e.g. the SOLWEIG model (Lindberg et al., 2008 ) and the RayMan model (Matzarakis et al., 2010 ). More complex models take more factors into account. ENVI-met is a three-dimensional non-hydrostatic microclimatic model, which includes a simple one dimensional soil model, a radiative heat transfer model, a vegetation model (Bruse and Fleer, 1998 ), as well as an air flow model. Diurnal forcing parameters can be defined and the resulting microclimatic parameters can be directly imported into BOTworld (Bruse, 2009 ) for multi-agent thermal outdoor comfort assessment, and considering specified pedestrian movement patterns (Robinson and Bruse, 2011 ). The most sophisticated models incorporate an energy balance or a dynamic thermoregulatory model of the human body, considering the different types of heat exchange (radiation, transpiration by skin vapour diffusion and sweat evaporation, dry and latent respiration) (Pearlmutter et al., 2007 ). The transient nature of outdoor thermal comfort may be assessed by determining comfort values, integrated over time and space, or, based on techniques originally developed for indoor applications (Nicol and Humphreys, 2010 ). The predicted comfort assessment can be compared to the results of in situ pedestrian surveys (Nikolopoulou et al., 2001 ).

3.3. Results and discussion

There are numerous experimental and numerical studies dealing with thermal comfort in urban outdoor spaces.

Within the project RUROS (Rediscovering the Urban Realm and Open Spaces), a large survey in 14 cities across Europe was conducted and the thermal comfort was analysed (Nikolopoulou, 2004 ). The project revealed two dominant factors affecting thermal perception, namely (i) the mean radiant temperature and (ii) the wind speed. Based on field measurements and a comfort survey, Tablada et al. (2009) suggested some preliminary design recommendations for residential buildings in the historical centre of Havana, Cuba. Ren et al. (2010) proposed to use urban climate maps, to transfer information on urban microclimate to city designers and planners. Erell et al. (2011) gave guidelines and examples of practical urban outdoor space design. Katzschner and Thorsson (2009) performed experimental microclimatic investigations as a tool for urban design, and compared field measurement with results from numerical modelling using SOLWEIG and ENVI-met.

Ali-Toudert and Mayer (2006) identified aspect ratio and orientation of an urban street canyon as important factors affecting the outdoor thermal comfort in hot and dry climate by means of a numerical study with ENVI-met. They showed that for many configurations, additional shading and cooling effects by vegetation and wind are needed to keep the outdoor comfort within acceptable ranges, and that different configurations might be optimal in regard to peak heat stress and diurnal comfort evaluations respectively. Yoshida (2011) developed a numerical method to assess pedestrian comfort evolution along a given walking trajectory, and found a significant effect of the walking direction on pedestrian thermal comfort (SET⁎ ). The impact of climate change on the microclimate in European cities was studied with ENVI-met by Huttner et al. (2008) .

With intensified urban heat island effects in growing cities and an increased heat wave occurrence frequency due to climate change, thermal comfort topics are currently extended into thermal stress and related health issues (Harlan et al ., 2006 ; Pantavou et al ., 2011 ).

4. Urban energy demand

4.1. Problem statement

As the fraction of people living in urban areas is expected to grow up to almost 70% by 2050, the energy consumption in cities is likely to follow that trend. During the next decades, urban planners and stakeholders will have to face major issues in terms of energy, traffic and resource flows. Their main concern will certainly be to find adequate ways of planning sustainable energy generation, distribution and storage, but also to increase energy efficiency and to reduce the dependency on non-renewable energies. Minimising the energy demand of buildings in urban areas has a great energy-saving potential (Santamouris, 2001 ).

The energy demand of a building in an urban area does not only depend on the characteristics of the building itself. Urban heat island effects at meso- and micro-scale as well as interactions with the surrounding buildings at local scale do have an important effect on the energy demand of a building in an urban area (Rasheed, 2009 ). As compared to an isolated building, a building in an urban area experiences: (i) increased maximum air temperatures due to the urban heat island effect; (ii) lower wind speeds due to a wind-sheltering effect; (iii) reduced energy losses during the night due to reduced sky view factors; (iv) altered solar heat gains due to shadowing and reflections; (v) a modified radiation balance due to the interaction with neighbouring buildings. All these effects have a significant impact on the energy demand of buildings (Kolokotroni et al., 2006 ), since it affects the conductive heat transport through the building envelope, as well as the energy exchange by means of ventilation (Ghiaus et al., 2006 ), and the potential to employ passive cooling (Geros et al., 2005 ) and renewable energy resources.

4.2. Methodology

There is a wide span of spatial and temporal scales which are relevant when assessing the energy demand of individual buildings or building clusters. The largest scale is probably the regional scale, which captures phenomena such as the heat island effect. At the other end of the spectrum, there is the scale of the individual building and its technical installation. A successful modelling approach to study the energy demand of an individual building or a cluster of buildings in an urban context needs to cover all these scales.

At the scale of the individual buildings detailed models exist, such as TRNSYS, IDA-ICE, EnergyPlus or ESP-r. These have to be supplied with suitable boundary conditions, which represent the urban microclimate. Several options exist: (i) heat island effects can be included by means of modified meteorological data, or from meso-scale meteorological models; (ii) radiation trapping and shadowing effects can be accounted for by values found in standards, simple geometrical relationships, or by explicitly modelling the effect of the local neighbourhood by means of a radiation model; (iii) convective heat transfer can be based on norm values, measured data or can be derived from CFD simulations. The most complex simulations combine building energy simulation tools with meso-scale meteorological models, radiation models and CFD. Combined or integrated urban microclimate modelling and building energy simulation was mainly advanced in Japan (Ooka, 2007 ; Chen et al ., 2009 ; He et al ., 2009 ).

At urban level there exist many tools for the design and planning of energy supply and distribution systems, based on assumed or measured annual or seasonal building energy demand figures. However, in order to consider interactions between energy demand and the urban microclimate, more complex tools are needed, as e.g. the CitySim simulation platform (Robinson et al., 2011 ). The tool consists of a collection of building physics models such as radiation, thermal, energy conversion and HVAC that were designed to conduct hourly simulations at the urban scale. Each building is modelled explicitly to be able to account for mutual interactions.

Prototypes of software platforms for the total analysis of urban climate were described by (Murakami, 2004 ; Tanimoto et al ., 2004 ; Mochida and Lun, 2008 ). They are mostly based on meso-scale meteorological models and employ urban canopy parameterisations to account for lower-scale phenomena such as the impact of urban surfaces (roofs, walls, streets) on wind speed, temperature, turbulent kinetic energy, shadowing, and radiation trapping. As demonstrated e.g. by Krpo (2009) or Santiago and Martilli (2010) , meso-scale meteorological models can be coupled to urban microclimate models to account for these lower-scale phenomena in a more detailed way.

4.3. Results and discussion

The impact of the urban heat island and the urban microclimate on the energy demand of buildings was investigated for a number of large cities, such as Athens (Santamouris et al., 2001 ), London (Kolokotroni et al ., 2006 ; Kolokotroni et al ., 2010 ), Kassel (Schneider and Maas, 2010 ), Tokyo (Hirano et al., 2009 ), and in a more general way by Hamdi and Schayes (2008) . Also the application limits of passive cooling by night-time ventilation were studied (Geros et al., 2005 ). The influence of building and ground surface reflectivity (albedo) on urban heat island intensity and building energy demand is widely analysed. Santamouris (2001) for instance reports a reduction of the energy demand for space cooling of 78% when increasing the building roof albedo from 0.20 to 0.78. Nevertheless, such studies mostly consider the buildings as stand-alone buildings, and do not take into account their (e.g. radiative) interaction with the local neighbourhood. Allegrini et al. (2011) showed that this may lead to huge differences in the predicted energy demand. They considered a stand-alone office building and a building surrounded by street canyons. In the latter, (i) measured field data were used to include the urban heat island effect; (ii) heat transfer coefficients determined by CFD were employed to account for the convective heat transfer along the building envelope; and (iii) radiative exchange was explicitly modelled taking into account the real urban geometry. In the considered case, the modified radiation balance was the main reason for the different energy demand. The other two aspects – heat island effect and convective energy losses – only had a secondary effect. This is in agreement with the findings of other authors. Bozonnet et al. (2007) established a dynamic coupling between a building energy simulation tool and a street canyon aeraulic zonal model for the air speed and temperature, which considers long wave radiative exchange and wind effects in a simplified way. They showed that the predicted building energy consumption for cooling in summer can differ by more than 30% depending on whether the chosen reference point for the outdoor air temperature is situated inside the street canyon or at the meteorological station. Bouyer et al. (2011) developed a coupled CFD—thermoradiative simulation tool and also showed the importance to model a specific building in its urban environment.

Anthropogenic heat fluxes such as heat released by air-conditioning facilities can have an important impact on urban environment and are to be accounted for in more complete studies of urban canopy climate such as urban heat island processes (Krpo, 2009 ) and in building cooling/heating energy demand analysis. One of the first works in which urban canopy parameterizations were taken into account inside a meso-scale meteorological model was the one of Kikegawa et al. (2003) . They used a simulation system consisting of a three-dimensional meso-scale meteorological model, a one-dimensional urban canopy model, and building energy model. The coupled model dynamically determines the energy demand for cooling and the corresponding generation of waste heat, in response to varying meteorological conditions. Additionally, it can be used to analyse the feedback mechanism, i.e. how the waste-heat affects the heat balance in the urban canopy layer (Kikegawa et al., 2006 ). Recent studies focus on surfaces with high albedo such as cool roofs and surfaces, as they have a significant impact both on building energy demand (Synnefa et al., 2007 ) and on the heat balance of the urban canopy (Scherba et al., 2011 ).

In summary, to accurately evaluate the building energy demand in a specific urban environment, a multiscale approach has to be adopted. The buildings radiation balance depends to a large extent on the urban setting and thus has to be considered in detail. Shading effects not only affect the radiation balance, but also influence the demand for artificial lighting and therefore the energy consumption (Strømann-Andersen and Sattrup, 2011 ). Also convective losses and the urban heat island effect play an important role in the energy demand. Additionally, effects such as evaporative cooling from wet surfaces and evapotranspiration from urban greenery have an impact on the urban microclimate (Saneinejad et al., 2011 ). Integrated approaches in urban design are becoming increasingly apparent (Santamouris, 2006 ).

5. Urban pollutant dispersion

5.1. Problem statement

Air pollution in the urban atmosphere can have an adverse impact on the climate (Dentener et al., 2005 ), on the environment (a.o. acid rain, crop and forest damage, ozone depletion) and on human health (Brunekreef and Holgate, 2002 ). The transport sector is responsible for a significant share of these emissions in the urban environment (O'Mahony et al., 2000 ). Other sources of emissions are industrial applications, domestic heating and cooling systems in residential buildings and the accidental and/or deliberate release of toxic agents into the atmosphere. After being emitted, the pollutants are dispersed (i.e. advected and diffused) over a wide range of horizontal length scales. The dispersion process is to a large extent affected by the characteristics of the flow field, which in turn is dominated by the complex interplay between meteorological conditions and urban morphology. During transport, chemically active pollutants might react with other substances and form reaction products. Traffic-induced emissions such as NOx and VOCs (Volatile Organic Compounds) are for instance the main precursors of tropospheric ozone. Furthermore, the concentration of airborne compounds is also affected by deposition processes. Distinction is made between so-called wet and dry deposition processes, depending on whether or not coagulation of pollutants with water droplets takes place.

From the preceding, it is clear that accurately predicting outdoor air quality is extremely complicated. In view of its importance, numerous studies have been performed in the past decades to arrive at a better understanding of pollutant emission, dispersion and deposition processes. Insight herein can help to develop measures to improve air quality, to reduce climate change, and to minimise the negative impact on the environment and human health.

5.2. Methodology

A comprehensive review of air pollution aerodynamics was recently compiled by Meroney (2004) , addressing the wide range of methods that exist for predicting pollutant dispersion, ranging from field tests and wind tunnel simulations to semi-empirical methods and numerical simulations with Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD).

Several field tests have been conducted in the past (e.g. Barad, 1958 ; Wilson and Lamb, 1994 ; Lazure et al ., 2002 ; Stathopoulos et al ., 2002 ; Stathopoulos et al ., 2004 ). Since these tests are conducted under real atmospheric conditions, they provide information on the full complexity of the problem. However, their strength is also their weakness: the uncontrollable nature and variation of wind and weather conditions leads to a wide scatter in the measured data (Schatzmann et al., 1999 ). Moreover, field tests can only be performed for existing building sites. A priori assessment of new urban developments is inherently not possible.

As opposed to field tests, wind tunnel modelling allows controlled physical simulation of dispersion processes (e.g. Halitsky, 1963 ; Huber and Snyder, 1982 ; Li and Meroney, 1983 ; Saathoff et al ., 1995 ; Saathoff et al ., 1998 ; Leitl et al ., 1997 ; Meroney et al ., 1999 ; Stathopoulos et al ., 2002 ; Stathopoulos et al ., 2004 ). Wind tunnel modelling can therefore be used to enhance field data (Schatzmann et al., 1999 ). Drawbacks of wind tunnel tests are that they can be time consuming and costly, that they are not applicable for weak wind conditions, and that scaling can be a difficult issue (see Section 7.3.3 ).

Semi-empirical models, such as the Gaussian model (Turner, 1970 ; Pasquill and Smith, 1983 ) and the so-called ASHRAE models (Wilson and Lamb, 1994 ; ASHRAE, 1999 ; ASHRAE, 2003 ) are relatively simple and easy-to-use, at the expense of limited applicability and less accurate estimates. The Gaussian model, in its original form, is not applicable when there are obstacles between the emission source and the receptor, and the ASHRAE models only evaluate the minimum dilution factor on the plume centreline.

Numerical simulation with CFD offers some advantages compared to other methods: it is often said to be less expensive than field and wind tunnel tests and it provides results of the flow features at every point in space simultaneously. However, CFD requires specific care in order for the results to be reliable (see Section 7.4 ). Therefore, CFD simulations should be performed in accordance with the existing best practise guidelines (Franke et al ., 2007 ; Franke et al ., 2011 ; Blocken et al ., 2007a ; Tominaga et al ., 2008b ) and should be validated based on high-accuracy experimental data (CODASC, 2008 ; CEDVAL-Compilation of Experimental Data for Validation of Microscale Dispersion Models, ; CEDVAL-Compilation of Experimental Data for Validation of Microscale Dispersion LES-Models, ).

5.3. Results and discussion

Several studies have compared the performance of RANS and LES approaches for pollutant dispersion in idealised urban geometries like street canyons (e.g. Walton and Cheng, 2002 ; Salim et al ., 2011a ; Salim et al ., 2011b ; Tominaga and Stathopoulos, 2011 ) and arrays of buildings (e.g. Chang, 2006 ; Dejoan et al ., 2010 ). Other efforts have compared RANS and LES for isolated buildings (e.g. Tominaga and Stathopoulos, 2010 ; Yoshie et al ., 2011 ; Gousseau et al ., 2011b ), courtyards (e.g. Moonen et al., 2011 ), cityblocks (e.g. Moonen et al., 2012 ), and in real urban environments (e.g. Hanna et al ., 2006 ; Gousseau et al ., 2011a ). Overall, LES appears to be more accurate than RANS in predicting the mean concentration field because it captures the unsteady concentration fluctuations. Moreover, this approach provides the statistics of the concentration field which can be of prime importance for practical applications. The predictive quality of RANS-type models highly depends on the turbulent Schmidt number (e.g. Riddle et al ., 2004 ; Tang et al ., 2005 ; Meroney et al ., 1999 ; Banks et al ., 2003 ; Blocken et al ., 2008a ; Tominaga and Stathopoulos, 2007 ). LES models allow updating the Schmidt number dynamically.

Many studies have pointed out that the width-to-height ratios of streets, their orientation and the presence of intersections, are critical parameters governing pollutant dispersion at street level in urban settings (e.g. Kastner-Klein et al., 2004 ). Soulhac et al. (2009) conducted numerical simulations of flow and dispersion in an urban intersection and compared the simulation results with wind tunnel measurements. They found that the average concentration along a finite-length street is significantly lower than that observed in an infinitely long street. Furthermore, they observed that the amount of vertical mixing remains limited, which leads to higher concentration levels at street level. Santiago and Martin (2005) showed that buildings with an irregular shape enhance turbulence and vertical mixing in the atmosphere. Wind tunnel measurements of Uehara et al. (2000) highlighted the impact of thermal stratification on the flow field in a row of urban street canyons. A weak standing vortex was found under stable atmospheric conditions, while unstable conditions tend to enhance mixing in the street canyon, causing the vertical temperature gradient to decrease, and thus the instability as well. Cheng and Liu (2011) have investigated the implications of thermal stratification on pollutant concentration. In neutral and unstable conditions the pollutant tends to be well mixed in the street canyons. A slightly improved pollutant removal is observed under unstable conditions because of enhanced roof-level buoyancy-driven turbulence.

Research towards passive measures of pollutant dispersion control has been conducted. The influence of avenue-like tree planting on pollutant dispersion was investigated by means of wind tunnel measurements (Gromke et al., 2008 ). It was shown that tree planting reduces the air change rate of an urban street canyon, and leads to increased concentrations on the leeward wall and slightly decreased concentrations at the windward wall. The effect is more pronounced for tree crowns with a lower porosity. These observations were confirmed by numerical simulations (Buccolieri et al ., 2009 ; Salim et al ., 2011a ; Salim et al ., 2011b ). McNabola et al. (2008) carried out a combined monitoring and numerical modelling study to highlight the role of an existing low boundary wall in an urban street in Dublin, Ireland. The wall was situated between the roadway footpath and the pedestrian boardwalk. The results of the study indicated greater exposure to fine particulates (PM2.5) and volatile organic compounds on the roadside footpath compared to the boardwalk. Simulations of a street canyon model consisting of two low boundary walls located adjacent to each footpath predicted reductions in pedestrian exposure of up to 65% for parallel wind conditions (McNabola et al., 2009 ).

Studies on active means to control pollutant dispersion are scarce. Mirzaei and Haghighat (2010) propose a pedestrian ventilation system in high rise urban canyons. The mechanism for ventilation is based on guiding air through a designed vertical duct system between the building roofs and the street level.

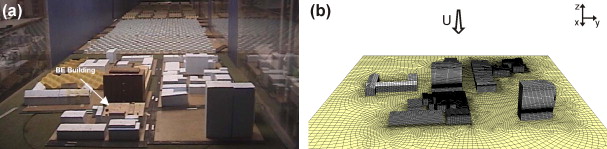

5.4. Case study

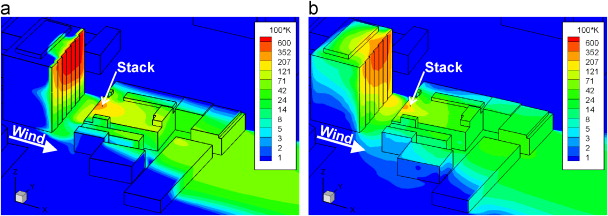

As an example, the case study by Gousseau et al. (2011a) for near-field gas dispersion in downtown Montreal is briefly reported. This study was incited by the fact that most previous studies on pollutant dispersion in actual urban areas all involved a large group of buildings (13 or more) with the primary intention to determine the far-field spread of contaminants released from a source through the network of city streets and over buildings. Gousseau et al. (2011a) categorised these studies as “far-field” dispersion studies. Given the extent of the computational domains involved, the grid resolutions in these far-field studies are generally relatively low, with a minimum cell size of the order of 1 m. The aim of the work by Gousseau et al. (2011a) therefore was to provide a near-field dispersion study around a building group in downtown Montreal on a high-resolution grid. The focus is both on the prediction of pollutant concentrations in the surrounding streets (for pedestrian outdoor air quality) and on the prediction of concentrations on building surfaces (for ventilation system inlets placement and indoor air quality). The CFD simulations were compared with detailed wind-tunnel experiments performed earlier by Stathopoulos et al. (2004) , in which sulphur-hexafluoride (SF6) tracer gas was released from a stack on the roof of a three-storey building and concentrations were measured at several locations on this roof and on the facade of a neighbouring high-rise building (Figure 7 a). Note that earlier CFD studies for the same case included none or only one of the neighbouring buildings (Blocken et al ., 2008a ; Lateb et al ., 2010 ), while in this study by Gousseau et al. (2011a) , surrounding buildings are included up to a distance of 300 m, in line with the best practice guidelines by Franke et al ., 2007 ; Franke et al ., 2011 and Tominaga et al. (2008b) . A high-resolution grid with minimum cell sizes down to a few centimetres (full-scale) was generated using the procedure by van Hooff and Blocken (2010a) (Figure 7 b). The grids were obtained based on detailed grid-sensitivity analysis. Both RANS and LES simulations are performed. The RANS simulations were performed with the standard k –ε model (SKE) and the LES simulations with the dynamic Smagorinsky subgrid scale model. For more details about the computational parameters and settings, including boundary conditions, the reader is referred to the original publication ( Gousseau et al., 2011a ). Figure 8 shows the contours of the non-dimensional concentration coefficient K on the building and street surfaces, for south-west wind, as obtained with RANS SKE and LES. For the RANS case shown in this figure, a turbulent Schmidt number of 0.7 has been used. Comparison between the simulation results and the wind tunnel measurements confirms the sensitivity of the RANS results to the turbulent Schmidt number and the overall good performance by LES.

|

|

|

Figure 7. Case study of near-field gas dispersion in downtown Montreal: (a) wind-tunnel model and (b) corresponding computational grid on the building and ground surfaces (Gousseau et al., 2011a ). |

|

|

|

Figure 8. Contours of 100 K on building surfaces and surrounding streets for south-west wind obtained with (a) RANS SKE and (b) LES (Gousseau et al., 2011a ). |

6. Urban wind-driven rain

6.1. Problem statement

Wind-driven rain (WDR) is one of the most important moisture sources affecting the hygrothermal performance and durability of building facades (Blocken and Carmeliet, 2004b ). Consequences of its destructive properties can take many forms. Moisture accumulation in porous materials can lead to rain water penetration (Day et al ., 1955 ; Marsh, 1977 ), frost damage (Price, 1975 ; Stupart, 1989 ; Maurenbrecher and Suter, 1993 ; Franke et al ., 1998 ), moisture-induced salt migration (Price, 1975 ; Franke et al ., 1998 ), discolouration by efflorescence (Eldridge, 1976 ; Franke et al ., 1998 ), structural cracking due to thermal and moisture gradients (Franke et al., 1998 ; Moonen et al., 2010 ), to mention just a few. WDR impact and runoff is also responsible for the appearance of surface soiling patterns on facades that have become characteristic for so many of our buildings (White, 1967 ; Camuffo et al ., 1982 ; Davidson et al ., 2000 ). Assessing the intensity of WDR on building facades is complex, because it is influenced by a wide range of parameters: building geometry, environment topography, position on the building facade, wind speed, wind direction, turbulence intensity, rainfall intensity and raindrop-size distribution.

6.2. Methodology

Three categories of methods exist for the assessment of WDR on building facades: (i) measurements, (ii) semi-empirical methods and (iii) numerical methods based on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). An extensive literature review of each of these categories was provided by Blocken and Carmeliet (2004b) . Measurements have always been the primary tool in WDR research, although a systematic experimental approach in WDR assessment is less feasible. Different reasons are responsible for this, the most important of which is the fact that WDR measurements can easily suffer from large errors (Högberg et al ., 1999 ; Van Mook, 2002 ; Blocken and Carmeliet, 2005 ; Blocken and Carmeliet, 2006b ). Recently, guidelines that should be followed for selecting accurate and reliable WDR data from experimental WDR datasets have been proposed (Blocken and Carmeliet, 2005 ; Blocken and Carmeliet, 2006b ). The strict character of these guidelines however implies that only very few rain events in a WDR dataset are accurate and reliable and hence suitable for WDR studies. Other drawbacks of WDR measurements are the fact that they are time-consuming and expensive and the fact that measurements on a particular building site have very limited application to other sites. These limitations drove researchers to establish semi-empirical relationships between the quantity of WDR and the influencing climatic parameters wind speed, wind direction and horizontal rainfall intensity (i.e. the rainfall intensity through a horizontal plane, as measured by a traditional rain gauge). The advantage of semi-empirical methods is their ease-of-use; their main disadvantage is that only rough estimates of the WDR exposure can be obtained (Blocken and Carmeliet, 2004b ). Recently, Blocken and Carmeliet (2010) and Blocken et al ., 2010 ; Blocken et al ., 2011a provided a detailed evaluation of the two most often used semi-empirical models, i.e. the model in the ISO Standard for WDR and the model by Straube and Burnett (2000) . Given the drawbacks associated with measurements and with semi-empirical methods, researchers realized that further achievements were to be found by employing numerical methods. In the past fifteen years, the introduction of CFD in the area has provided a new impulse in WDR research.

Choi, 1991 ; Choi, 1993 ; Choi, 1994a ; Choi, 1994b ; Choi, 1997 developed and applied a steady-state simulation technique for WDR, in which the wind-flow field is modelled using the RANS equations with a turbulence model to provide closure. The raindrop trajectories are determined by solving the equation of motion of raindrops of different sizes in the wind-flow pattern. This technique has been universally adopted by the WDR research community. In 2002, Blocken and Carmeliet (2002) extended Chois steady-state simulation technique into the time domain, allowing WDR simulations for real-life transient rain events. Some first CFD validation studies of the steady-state technique were performed by Hangan (1999) and Van Mook, 2002 . The extension of Chois technique into the time domain allowed detailed validation studies to be performed based on full-scale WDR measurements from real-life transient rain events. The first study of this type was made by Blocken and Carmeliet (2002) for a low-rise test building. Later, the same authors performed more detailed validation studies for the same building (2006b, 2007). In 2004, the extended WDR simulation method by Blocken and Carmeliet was also used by Tang and Davidson (2004) to study the WDR distribution on the high-rise Cathedral of Learning in Pittsburgh. Later validation studies by Abuku et al. (2009a) for a low-rise building and Briggen et al. (2009) for a tower building also used this method.

The steady-state CFD technique for WDR was also employed to study the distribution of WDR over small-scale topographic features such as hills and valleys (Arazi et al ., 1997 ; Choi, 2002 ; Blocken et al ., 2005 ; Blocken et al ., 2006 ). Arazi et al. (1997) compared CFD simulations of WDR in a small valley with the corresponding measurements. Choi (2002) modelled WDR impingement on idealised hill slopes. Blocken et al. (2005) simulated WDR distributions on sinusoidal hill and valley slopes. Finally, Blocken et al. (2006) performed validation of CFD simulations of the WDR distribution over four different small-scale topographic features: a succession of two cliffs, a small hill, a small valley and a field with ridges and furrows. The steady-state CFD technique for WDR was later also used by Persoon et al. (2008) and van Hooff et al. (2011a) to study WDR impingement on the stands of football stadia.

The numerical model for the simulation of WDR on buildings, developed by Choi, 1991 ; Choi, 1993 ; Choi, 1994a ; Choi, 1994b and extended by Blocken and Carmeliet (2002) , consists of the five steps outlined below. For more information, the reader is referred to the original publications.

- The steady-state wind-flow pattern around the building is calculated using a CFD code.

- Raindrop trajectories are obtained by injecting raindrops of different sizes in the calculated wind-flow pattern and by solving their equations of motion.

- The specific catch ratio is determined based on the configuration of the calculated raindrop trajectories.

- The catch ratio is calculated from the specific catch ratio and from the raindrop-size distribution.

- From the data in the previous step, catch-ratio charts are constructed for different zones (positions) at the building facade. The experimental data record of reference wind speed, wind direction and horizontal rainfall intensity for a given rain event is combined with the appropriate catch-ratio charts to determine the corresponding spatial and temporal distribution of WDR on the building facade.

This model is referred to as the “Eulerian-Lagrangian” model for WDR, because the Eulerian approach is adopted for wind-flow field, while the Lagrangian approach is used for the rain phase. Recently, Huang and Li (2010) employed an “Eulerian-Eulerian” model for WDR, in which also the rain phase is treated as a continuum, and they successfully validated this model based on the WDR measurements on the VLIET building by Blocken and Carmeliet (2005) .

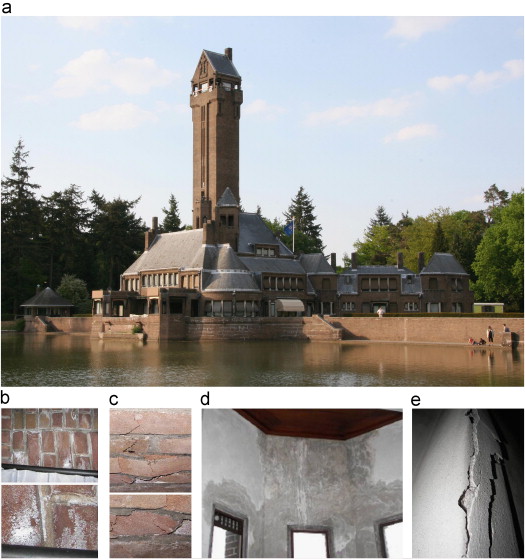

6.3. Case study

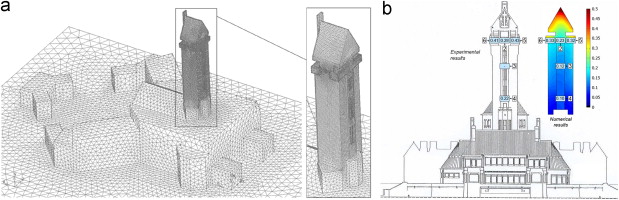

Hunting Lodge “St. Hubertus” is a monumental building situated in the National Park “De Hoge Veluwe” (Figure 9 a). Especially the south-west facade of the building shows severe deterioration caused by WDR and subsequent phenomena such as rain penetration, mould growth, frost damage, salt crystallisation and efflorescence, and cracking due to hygrothermal gradients (Figure 9 b–e). To analyse the causes for these problems and to evaluate the effectiveness of remedial measures, Building Envelope Heat-Air-Moisture (BE-HAM) simulations are generally conducted. However, these BE-HAM simulations require the spatial and temporal distribution of WDR on the facade as a boundary condition. Therefore, both field measurements and CFD simulations of wind around the building and WDR impinging on the building south-west facade were performed by Briggen et al. (2009) . The field measurements include measurements of wind speed and wind direction, horizontal rainfall intensity (i.e. the rainfall intensity falling on the ground in unobstructed conditions), and WDR intensity on the facade. The WDR measurements were made at 8 positions and by WDR gauges that were designed following the guidelines by Blocken and Carmeliet (2006b) . The WDR measurements at the few discrete positions do not give enough information to obtain a complete picture of the spatial distribution of WDR on the south-west facade of the tower. Therefore, they are supplemented by the CFD simulations. First, the WDR measurements were used to validate the CFD simulations, after which the CFD simulations were used to provide the additional WDR intensity information at positions where no WDR measurements were made. Note that for selecting the rain events for CFD validation, the guidelines by (Blocken and Carmeliet, 2005 ) were followed, which are important to limit the measurement errors and in order not to compromise the validation effort. Figure 10 (a) shows the computational grid of the monumental building, in which the detailed geometry of the south-west building facade was reproduced. The CFD simulations were made with steady RANS and the realisable k –ε model ( Shih et al., 1995 ), and with the Lagrangian approach for WDR. Figure 10 (b) compares measured and simulated catch ratios at the south-west facade at the end of a rain event, during which the wind direction was perpendicular to this south-west facade. The catch ratio is the ratio between the sum of WDR and the sum of horizontal rainfall during this rain event. Given the complexity of the building and of WDR in general, the agreement at the top part of the facade is considered quite good. However, at the bottom of the facade, a large deviation is obtained between simulations and measurements. As discussed by Briggen et al. (2009) , this deviation is attributed to the absence of turbulent dispersion in the Lagrangian raindrop model. This absence will lead to less accurate results at the lower part of high-rise buildings. Future RANS WDR simulations for high-rise buildings should therefore either include turbulent dispersion models or they should employ LES, in which the turbulent dispersion of raindrops can be explicitly resolved.

|

|

|

Figure 9. (a) Hunting Lodge St. Hubertus and moisture damage at the tower due to wind-driven rain: (b) salt efflorescence; (c) cracking/blistering due to salt crystallisation; (d) rain penetration and discolouration; (e) cracking at inside surface (Briggen et al., 2009 ). |

|

|

|

Figure 10. (a) Computational grid (2'110'012 cells) and (b) spatial distribution of the catch ratio at the end of a rain event. The experimental results at the locations of the wind-driven rain gauges are shown on the left, the numerical results are shown on the right (Briggen et al., 2009 ). |

7. Urban Physics: research methods

7.1. Scientific approaches

The three main research methods in Urban Physics are field measurements, wind tunnel measurements and numerical simulations based on Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). These three methods are to a large extent complementary.

7.2. Field experiments

7.2.1. Role of field experiments in Urban Physics

Field experiments are indispensable in Urban Physics, because only field experiments represent the real complexity of the problem under investigation. Neither wind tunnel measurements, nor CFD can fully reproduce this real complexity. As such, field experiments – if conducted with great care and for a sufficiently long measurement period – are very valuable, and in many cases even necessary, to validate wind tunnel measurements and CFD simulations. Nevertheless, studies in which field measurements have been used to evaluate wind tunnel measurements and CFD are relatively scarce.

In pedestrian-level wind studies, wind tunnel experiments have been evaluated based on field measurements by Isyumov and Davenport (1975) ; Williams and Wardlaw (1992) ; Visser and Cleijne (1994) and Yoshie et al. (2007) . Published evaluations of CFD for pedestrian wind conditions with field measurements has – to our knowledge – only been performed by Yoshie et al. (2007) ; Blocken and Persoon (2009) and Blocken et al. (2012) .

In pollutant dispersion studies, comparisons of wind tunnel experiments and field measurements have been made by Stathopoulos et al. (2004) . Additionally, a number of large field campaigns have been conducted, such as the Mock Urban Setting Test (MUST) (Biltoft, 2001 ), the Joint Urban 2003 Oklahoma City (OKC) Atmospheric Dispersion Study (Allwine et al., 2004 ), the Dispersion of Air Pollution and its Penetration into the Local Environment campaign (DAPPLE) (Arnold et al., 2004 ) and the Basel Urban Boundary Layer Experiment (BUBBLE) (Rotach et al., 2005 ). The data acquired in these studies have been widely used to validate CFD models (e.g. Santiago et al., 2010 ; Dejoan et al., 2010 (MUST), Chan and Leach, 2007 ; Neophytou et al., 2011 (OKC), Xie and Castro, 2009 (DAPPLE), Rasheed, 2009 (BUBBLE)) and to compare to wind tunnel measurements (e.g. Bezpalcova, 2007 (MUST), Klein et al., 2011 (OKC), Carpentieri et al., 2009 (DAPPLE), Feddersen, 2005 (BUBBLE)).

7.2.2. Measurement techniques and challenges

A wide variety of measurement techniques exist, most of which are classified as point measurements. This holds amongst others for measurements of wind speed and wind direction, rainfall intensity, wind-driven rain intensity, temperature, relative humidity, short-wave and long-wave radiation and moisture content. A full description of measurement techniques for Urban Physics is outside the scope of this paper. The interested reader is referred to Hewitt and Jackson (2003) .

Because they are point measurements and because they are performed under largely uncontrolled (meteorological) conditions, field measurements by definition give an incomplete picture of the problem under study. This motivates the employment of wind tunnel testing (see Section 7.3 ) and CFD simulations (see Section 7.4 ). First, these tests and simulations can be calibrated/validated based on the field measurements, after which they can be used to provide information beyond the point measurements made in the field.

Important challenges concerning field measurements are related to spatial and temporal extent and spatial and temporal resolution, all of which are limited. Another important problem is repeatability, which strictly does not occur in reality. In this respect, field measurements are fundamentally different from wind tunnel experiments and CFD simulations, in which the boundary conditions can be controlled and in which repeatability should be straightforward. The variability and uncontrollability of field measurement conditions imply that validation of wind tunnel results and CFD simulation results with field measurements only makes sense when the latter have been obtained based on long time series, to average out the inherent meteorological variability. These issues have been discussed and demonstrated in detail by Schatzmann et al. (1997) and by Schatzmann and Leitl (2011) .

7.3. Wind tunnel experiments

7.3.1. Role of wind tunnel experiments in Urban Physics

Wind tunnel experiments in the field of Urban Physics are widely applied to (i) determine wind loads, e.g. on the facades and roof of a low-rise building (Uematsu and Isyumov, 1999 ), (ii) assess outdoor wind comfort, e.g. in passages and near high rise buildings (Kubota et al., 2008 ), and (iii) analyse pollutant dispersion e.g. in street canyons and intersections (Ahmad et al., 2005 ). Besides this applied research, studies on basic configurations are conducted (single bluff bodies, arrays) to get more insight in the flow structure and to serve as validation for numerical models (Minson et al., 1995 ). Finally, wind tunnel measurements can also be utilised to enhance field data, i.e. to assess the degree of uncertainty on the measured data (Schatzmann et al., 2000 ).

7.3.2. Measurement techniques

There is a multitude of wind tunnel measurement techniques. Giving a comprehensive overview is beyond the scope of this article. The interested reader is referred to Barlow et al. (1999) . Below, we summarise the most commonly used methods to measure three quantities of interest, namely the velocity, the pressure and the scalar concentration.

The most widely used techniques to measure velocities are based on Thermal Anemometry (TA), Laser Doppler Velocimetry (LDV) and Particle Imaging Velocimetry (PIV). In contrast to the former technique, the latter two techniques are non-intrusive and hence do not interfere with the velocity to be measured. Where Thermal Anemometry and Laser Doppler Velocimetry are point-wise techniques, Particle Imaging Velocimetry provides whole-field data. Particle Imaging Velocimetry is the only technique that allows studying all components of the velocity vector and its derivatives in a spatially and temporally resolved way. However, the need for optical access limits the applicability in complex urban environments.

Pressure distribution across the surfaces of a model can be measured if the model includes flush-mounted (static) pressure taps. The taps are connected via tubes to a pressure transducer, often located outside of the wind tunnel model. The transducer measures the difference between the pressure in the tube and a reference pressure. The length between the sensor and the pressure tap governs the response time. Alternatively, Pressure Sensitive Paint (PSP) can be employed to measure surface pressures.

The Flame Ionisation Detector (FID) is the most widely used device for hydro-carbon concentration measurements. It is a point-wise measurement technique, with a temporal resolution 1–1000 Hz. Recently Laser-Induced Fluorescence (LIF) became available as an alternative concentration measurement tool. Like Particle Imaging Velocimetry, it is an optical technique. Laser-Induced Fluorescence can be used to measure instantaneous whole-field concentration or temperature maps at high temporal resolution.

7.3.3. Challenges

7.3.3.1. Similarity

Wind tunnel tests are usually performed on a scale model of the real geometry. In order for the results of the wind tunnel test to be applicable in real-life, some general similarity criteria have to be satisfied. This implies that three types of similarity must exist. Geometric similarity implies that both have the same shape. Kinematic similarity implies that fluid velocities and velocity gradients are in the same ratios at corresponding locations. Dynamic similarity implies that the ratios of all forces acting on corresponding fluid particles and boundary surfaces in the two systems are constant. Additionally thermal similarity has to be realized if thermal effects are expected to play a role, and mass ratios need to be similar when dispersion processes are of importance. The general requirements for similarity of flow in the atmospheric boundary layer are obtained by converting the governing equations into a dimensionless system of equations by scaling the dependent and independent variables. During this procedure, certain dimensionless parameters are formed from the scaling factors. The values of the dimensionless parameters have to be the same for both the scale model and application. Strict similarity can almost never be realized (Cermak, 1971 ). Selecting the relevant dimensionless parameters, such as the Reynolds-number to obtain similitude of the flow field, the Richardson or Froude number to properly scale thermal effects and the Schmidt-number to control dispersion processes, and determining the test conditions accordingly is one of the most important challenges in wind tunnel modelling (VDI 3783-12, 2000 ; Kanda, 2006 ).

7.3.3.2. Blockage

The blockage ratio is the ratio between the frontal area of the model and the area of the wind tunnel cross-section (Holmes, 2001 ). Employing a too high blockage ratio may lead to a significant increase of the velocities around and the pressures on the model. Generally 4% is considered as the upper limit (Okamoto and Takeuchi, 1975 ), but even below this threshold a distinct effect on the mean velocities can be observed (Castro and Robins, 1977 ). Theory to correct for the effects of blocking have been developed, based upon the pioneering work of Maskell (1963) .

7.3.3.3. Boundary layer

In order for the results of the wind tunnel test to be applicable to practice, it is important that not only the model, but also the boundary layer has similitude (see ) with the real atmospheric boundary layer. This implies not only that the average velocity and turbulence intensity profile should be similar, but also that the power spectrum and the integral length scales are comparable (Cook, 1978 ; De Bortoli et al ., 2002 ). A boundary layer profile can be created by a combination of barrier, spires and roughness elements (Cook, 1978 ), or, in special wind tunnels by controlling the individual fans in a large fan cell array (Liu et al., 2011 ).

7.3.3.4. Atmospheric stability

Most wind tunnel tests are performed under neutral atmospheric stability. This condition however occurs only for a limited amount of time in reality. Measurements in Cracow, Poland revealed for instance that neutral conditions occur about 20% to 40% of the time, depending on the season (Walczewski and Feleksy-Bielak, 1988 ). Despite often being neglected, atmospheric stability could have a major impact on many phenomena in the field of Urban Physics. Pollutant concentrations tend to be higher for stable atmospheric conditions than for unstable conditions (Uehara et al. 2002). Some wind tunnels offer the possibility to study stratified flow (e.g wind tunnel of Institute Industrial Science the University of Tokyo). Performing such kind of studies greatly complicates the way to reach similitude.

7.4. Numerical simulations

7.4.1. Role of CFD in Urban Physics

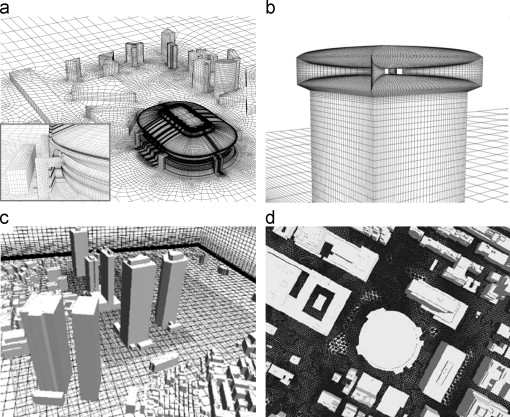

Although CFD has been originally developed and applied for aeronautical research, it has been used as well in more applied fields of research during the past decades. Urban Physics is one of them. Nowadays, CFD studies are used in almost all areas of Urban Physics research, of which a non-exhaustive list is given:

- Pedestrian wind and thermal comfort (e.g. He and Song, 1999 ; Blocken and Carmeliet, 2004a ; Blocken et al ., 2004 ; Stathopoulos, 2006 ; Yoshie et al ., 2007 ; Mochida and Lun, 2008 ; Tominaga et al ., 2008b ; Blocken and Persoon, 2009 ; Bu et al ., 2009 ; Blocken et al ., 2008b ; Blocken et al ., 2012 ).

- Wind-driven rain (e.g. Choi, 1993 ; Choi, 1994a ; Blocken and Carmeliet, 2002 ; Blocken and Carmeliet, 2004b ; Blocken and Carmeliet, 2006a ; Blocken and Carmeliet, 2007 ; Abuku et al ., 2009a ; Briggen et al ., 2009 ; Blocken et al ., 2010 ; Huang and Li, 2010 ; van Hooff et al ., 2011a ) (Figure 11 a and b).

|

|

|

Figure 11. (a and b) Wind-driven rain research: south-west facade of the VLIET test building and simulated wind-driven raindrop trajectories for south-west wind (Blocken and Carmeliet, 2002 ); (c and d) air pollutant dispersion research: view from east at part of downtown Montreal and contours of dimensionless concentration coefficient on the building and street surfaces (Gousseau et al., 2011a ); (e and f) surface erosion research: overview of the Giza plateau and contours of the surface friction coefficient (Hussein and El-Shishiny, 2009 ); (g and h) natural ventilation research: view from south at the Amsterdam ArenA stadium and surrounding buildings and contours of velocity magnitude for west wind (van Hooff and Blocken, 2010b ). |

- Pollutant dispersion (e.g. Tominaga et al ., 1997 ; Blocken et al ., 2008a ; Gromke et al ., 2008 ; Balczo et al ., 2009 ; Tominaga and Stathopoulos, 2010 ; Tominaga and Stathopoulos, 2011 ; Gousseau et al ., 2011a ; Gousseau et al ., 2011b ; Yoshie et al ., 2011 ) and deposition (e.g. Jonsson et al ., 2008 ; Meroney, 2008 ) (Figure 11 c and d).

- Urban heat island effects (e.g. Mochida et al ., 1997 ; Sasaki et al ., 2008 ).

- Preservation of cultural heritage (e.g. Hussein and El-Shishiny, 2009 ) (Figure 11 e and f).

- Design and performance analysis of building components.

- Solar collectors, ventilated photovoltaic arrays or building-integrated photovoltaic thermal systems (e.g. Gan and Riffat, 2004 ; Corbin and Zhai, 2010 ; Karava et al ., 2011a ).

- Solar chimneys (e.g. Ding et al ., 2005 ; Harris and Helwig, 2007 ).

- Building facades (e.g. Loveday et al ., 1994 ; Ding et al ., 2005 ), e.g. double-skin facades.

- Energy performance analysis of buildings (e.g. Zhai et al ., 2002 ; Zhai and Chen, 2004 ; Zhai, 2006 ; Albanakis and Bouris, 2008 ; Barmpas et al ., 2009 ; Blocken et al ., 2009 ; Defraeye and Carmeliet, 2010 ; Defraeye et al ., 2011a ).

- Hygrothermal analysis of exterior building envelopes (e.g. Blocken et al ., 2007c ; Abuku et al ., 2009b ; Carmeliet et al ., 2011 ) and building envelope materials (e.g. Defraeye et al., 2012 ).

- Flow over complex topography (e.g. Kim et al ., 2000 ; Blocken et al ., 2006 ).

- Natural ventilation of buildings (e.g. Jiang et al ., 2003 ; Karava et al ., 2007 ; Karava et al ., 2011b ; Chen, 2009 , van Hoof and Blocken 2010a, 2010b, Norton et al ., 2009 ; Norton et al ., 2010 ) and design of natural ventilation systems (e.g. Montazeri et al ., 2010 ; van Hooff et al ., 2011b ; Blocken et al ., 2011c ) (Figure 11 g and h).

CFD has specific advantages compared to field experiments or wind-tunnel experiments: