Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

As a mechanism for social participation and integration and for the purpose of building their identity, teens make and share videos on platforms such as YouTube of which they are also content consumers. The vulnerability conditions that occur and the risks to which adolescents are exposed, both as creators and consumers of videos, are the focus of this study. The methodology used is content analysis, applied to 400 videos. This research has worked with manifest variables (such as the scene) and latent variables (such as genre or structure). The results show that there are notable differences in style among the videos according to the producer of the message, and indicate that the most consumed videos are located around four thematic axes (sex, bullying, pregnancy and drugs) and that the referents as audiovisual content creators are the YouTubers. Everything points to problems in using the same language, including audiovisual language, as adolescents. This paper provides evidences of the convenience of using their codes so that this sector of the population see risks and conditions of vulnerability that they seem not to perceive according to their audiovisual creations in which they do not protect their identity, among other features.

1. Introduction, current situation, aims, and objectives

The subject matter of this research is audiovisual content directed at teens, made by them themselves or by other agents, through the YouTube platform. To this end, vulnerability (Fuente-Cobo, 2017) and the risks associated with the consumption, preparation, and exposure of this type of content by this sector of the population (O’Keeffe & Clarke-Pearson, 2011) are taken to be key factors.

The electronic environment has affected the traditional problems of adolescence due to the “increase in online communication, the existence of wider peer networks and greater opportunities for self-presentation and exploring identity” (Subrahmanyam, Greenfield, & Michikyan, 2015: 126). When studies continue to warn of an increased percentage of conditions that favour addition to Internet use, especially by young people (Bleakley, Ellithorpe, & Romer, 2016), it becomes essential to know how adolescents interact with the digital environment (Blomfield & Barber, 2014). It is a medium in which phenomenon such as cyber bullying (Edwards, Kontostathis, & Fisher, 2016) develop, with video being one of the tools used (Álvarez-García, Barreiro-Collazo, & Nuñez, 2017).

This research continues the line focusing on the risks and defined by the studies, led by Sonia Livingstone, on EU-Kids Online. It also progresses specifically as regards situations of vulnerability occurring in both the creation and the consumption of audiovisual material by teens.

The risks children are exposed to include viewing inappropriate material. The content broadcast on YouTube is of a very diverse nature and has very varied, not always positive, intentions. According to the study by Livingstone and others (2014), almost one-third of adolescents state they have seen material they did not like, the most frequent incident being exposure to violent or pornographic videos. In the work of Yarosh and others (2016), which records and compares the topics appearing on two platforms like YouTube and Vine, it is observed there is a greater percentage of videos containing sexual, violent or obscene content appearing on the latter. Exposure to certain commercial offerings broadcast on networks such as YouTube, Facebook and Twitter also entails a risk, as studies such as the research by Barry and others (2015) demonstrate that children can be exposed through these media to content that is advertising alcoholic beverages.

Another cause for concern is the level of credibility underage viewers can lend to the content of certain videos, especially if on delicate subjects such as health. Studies on this subject already exist as regards accuracy in videos on anorexia, analysed by Syed-Abdul and others (2013), and the lower visibility achieved by health videos from reliable sources, conducted by Karlsen, Borrás-Morell, and Traver-Salcedo (2017). These make it necessary to reassess the appropriateness of protocols to filter this type of material, so as to prevent certain content from becoming highly circulated and popular. This is all the more relevant when research such as that conducted by López-Vidales and Gómez-Rubio (2015) indicates that institutional videos (in this case dealing with the issue of drugs) are not widely accepted or circulated among teens.

As regards vulnerability, teenagers are a particularly vulnerable group since while they are aware of the risks of the Internet, which they consider a space open to an unknown public, they have a different perception of environments such as social networks. These they deem safer, private and far removed from the dangers linked to the Internet (Martínez-Pastor, Sendín-Gutiérrez, & García-Jiménez, 2013; Sabater, 2014). This perception, according to Blais and others (2008), is underpinned by the fact that applications which enable direct, individualised communication, such as instant messaging, increase trust and the feeling of privacy even though these applications are operating in an online environment. Moreover, there is a dissociation between the negative experiences endured by the adolescents in the social media environment and their assessment of the risk posed by social network usage (De-Frutos & Marcos, 2017).

In order to explore identity construction and social integration and participation, teenagers make videos that they share and spread through social networks or specific platforms such as YouTube, which enable their creations to achieve a wider circulation. The repercussions from the dissemination of these videos involve all types of spheres. As they are experimenting with new forms of communication and audiovisual styles, the spheres range from social (Abisheva & al., 2014) or cultural (Bañuelos, 2009; Chau, 2010) areas (Misoch, 2014) to public health issues (Wartella & al., 2016), political topics (Dias-da-Silva & Garcia, 2012) and economic matters (Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010), among others.

Jenkins, Ford, and Green (2015) state that whenever a teen creates some Harry Potter fan fiction, the value of the Harry Potter brand rises. Every time a fan shares a Star Wars parody on YouTube, the actions of that narrative world in the kingdom of intangible assets goes up (Jenkins, Ford, & Green, 2015: 10. These actions affect areas as diverse as economics or culture.

YouTube is a platform with content specifically aimed at teens, and accessing this social network is one of the first things individuals do when starting out in the digital domain, regardless of the device they use to connect to it (Protégeles, 2014). Given that adolescents do not only consume audiovisual material they have created, in this study, we will also deal with productions disseminated by other agents such as the media or YouTubers. The latter have a great influence on teenagers, as can be seen from the conclusions of the study by McRoberts and others (2016), as young people imitate the creative guidelines of the professionals, although they do not have video editing or position themselves using meta data as YouTubers do.

Participation levels by YouTube users differ greatly. In some areas, such as politics, huge consumption of materials on this subject does not go hand in hand with mass production of videos. In this case, passive users predominate, and participation frequently involves sharing videos that have already been broadcast on other media such as the television (Berrocal, Campos, & Redondo, 2014) rather than users creating their own content. More active prosumers who record and share audiovisual messages are found elsewhere, in cultural or social areas, for example. YouTube even becomes an efficient tool for education and, moreover, for dissemination of science, through live transmission of academic events (Franco, 2017), among other possibilities.

In essence, we will analyse the content of the videos targeting teenagers in order to determine the subjects of interest, discover who the authors are, look at the communication styles and thus define the risks they are exposed to. In addition, the vulnerability factors there are, both in the consumption and in the creation and dissemination of these materials by the adolescents themselves, an active sector of the population in all aspects: a creative, participative and consumer population (García-Jiménez, Catalina-García, & López-de-Ayala, 2016). The aims and objectives of this paper are:

a) To identify the situations of vulnerability and the underlying risks in the videos made and disseminated by the teens themselves.

b) To analyse the characteristics of the audiovisual creations in terms of focus and their style-genre, as well as other aspects relating to the level of impact based on indicators such as the number of views, “likes” or “dislikes”, and comments generated.

c) To determine what content (subjects) is aimed at teens on YouTube, how it is constructed, based on genre, focus and structure, and what the most consumed content is (number of “likes”, views or comments). Given that YouTube videos are accessed through popularity filters, the aim is to analyse the suitability of the content, the risk of consuming material that is not suitable for children or the treatment of certain subjects which may lead to risky situations. In this case, we will take especially into account two types of audiovisual content producers which are held out as being fundamental when defining the communicative reality of teens: YouTubers, given that their productions achieve high levels of popularity, and the media, whose videos are created by audiovisual media professionals but have a lower impact on YouTube.

2. Material and methods

YouTube is a channel that is conducive to spreading messages as it has become a forum of global dimensions (Jiménez & Gaitán, 2013). The aim is to find out through this study what type of audiovisual works, aimed at adolescents, are available on this social network, which we can class as such given that it allows teens and young people to reflect their interests and contact peers who share them (Lenhart & al., 2015). The producers of the videos include the adolescents themselves, who demand their space and part of the limelight (Aguaded & Sánchez, 2013).

2.1. Methodology

In this study, the content analysis technique has been used, which enables comparable and repeatable quantitative data, as well as the subsequent comparison of the data to identify if certain factors or “clusters” link or separate them. As these are audiovisual units, a record has been made, in accordance with the terminology from Igartua (2006), of both manifest variables (such as the setting, whether children appear in the video and whether their identities have been protected) and latent variables (structure, genre or focus, among others).

Although adapted to a certain extent, the protocol and indicators used are based on previous work such as that by Yarosh and others (2016) focusing on the audiovisual content published by adolescents and the study by Halliday (2004) into the modal structure of the videos. The action protocol which has enabled the formal, narrative, thematic or evaluative components of the audiovisual content to be studied has been verified at various stages of the research.

Finally, the variables recorded in this study were: link and address of the video, consultation dates (discovery and viewing of the video by the researchers) and date of the publication of the video, description (whether it contains it or not), category (according to YouTube categories), title, authorship, user (who hosts the video), duration, genre or format (expanded values from Yarosh & al., 2016), appearances by children (and if their identity is protected or not in the cases where they appear), structure (declarative, imperative or interrogative; based on Halliday, 2004), focus (positive, negative, neutral or undetermined), presence of content related to vulnerability and risks, subject, space of the representation (private or public), three variables relating to the interaction it generates (amount of “likes”, “dislikes” and comments) and, lastly, number of views (relevance).

2.2. Definition of the sample

The audiovisual content studied was determined through a selection process involving tags. The study aimed to analyse videos created by teens, although it did not want to be limited to these authors. However, to facilitate discovery of the videos produced by them, a search was conducted on the YouTube website, using speech marks, for the expression “teenager videos” (more specific for this purpose than if only the term “teenagers” had been used).

Although platforms like YouTube promote active users, who do not only limit themselves to consuming content but also produce content (Ritzer, Dean, & Jurgeson, 2012), it is no simple matter for teens to gain visibility and achieve an impact for the content they upload to YouTube. Taking into account the objectives of the study, it was decided to arrange the results of the search based on the number of views –even though this made it more difficult for videos created by teens to form part of the selection– and an initial sample of 100 videos were defined. Although studies such as that by Karlsen, Borrás-Morell, and Traver-Salcedo (2017) mention the suitability of implementing other variables in the internal YouTube search mechanism, which makes it easier to arrange in order and discover content through approaches other than number of views or popularity of the video (such as the credibility of the source), it was decided to choose the number of views. It is the clearest current manner to ensure the videos analysed have been disseminated to at least a certain extent.

The language factor also conditioned the sample, as it focused on audiovisual content in Spanish. With the aim of analysing units that were fairly current, the sample comprised videos hosted on YouTube as of 2010. This time margin was left since, in order to reach a relevant number of views, videos tend to need to be present for a certain amount of time on the platform, although among the 100 videos of the initial sample, only two had such an old upload date.

Once the aforementioned conditioning factors had been applied, the variables of the analysis protocol were tested. This made it possible to refine certain values as well as to rule out some variables (whose results would not be material due to the diversity of their authorship) and the subjects present in the 100 videos making up the initial sample were recorded.

After locating four redundant subjects (sex, drugs, bullying, and pregnancy) in this initial group, the sample was increased to 400 videos. However, the 300 new videos incorporated into the study focused exclusively on these recurring subjects based on the tags “teenagers sex”, “teenagers drugs”, “teenagers pregnancy” and “teenagers bullying”. As can be seen in the scientific literature, these subjects are in tune with the lines established by the researchers in the area: sexual relations (sex, pregnancy), consumption of harmful substances (alcohol or drugs, among others) and situations of bullying and violence. Studies such as those of Livingstone and others (2014), Barry and others (2015), López-Vidales and Gómez-Rubio (2015), Edwards, Kontostathis and Fisher (2016), Yarosh and others (2016) and Álvarez-García, & Barreiro-Collazo and Nuñez (2017) corroborate that the aforementioned subjects are of great interest to teenagers.

3. Analysis and results

3.1. Authorship

As has been commented, this study opted to determine the authorship of the video (the original author). This task presents some difficulties, and therefore it is not surprising that the first category should be “unknown” with a score of 25.3%. When the content of the video or the information provided by the user hosting it did not make it possible to specify the authorship, it was opted to record it as “unknown”. In the second position were videos uploaded by the media, representing 20.3%, followed by 15.1% of videos where the author is a teenager.

Furthermore, there are two intermediate groups, such as YouTubers (most of whom are young), who represent 8.8% of the total number of videos analysed, and public institutions, which essentially disseminate campaigns to raise society’s awareness of any aspect deemed to be of interest. Adults or professionals (10.3%) upload fewer videos than teenagers, that demonstrates that YouTube is a field mostly dominated by young people.

3.2. Conditions of vulnerability3.2.1. Appearances by children

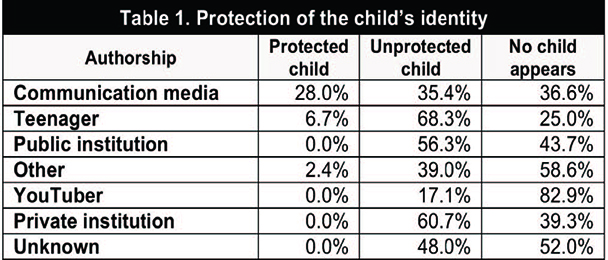

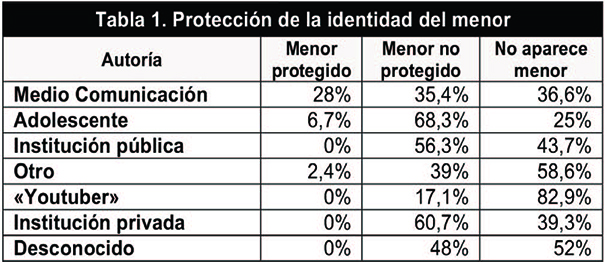

In this study, an analysis has also been made of how children appear, although it has to be borne in mind that in certain age groups it is difficult to determine the possible year of birth of the people appearing in the audiovisual content. In this case, it can be observed that it is in the videos authored by teenagers where their identities are least protected (68.3%). It also highlights the fact that in both private and public institutions there is a high percentage of documents in which it is possible to see children whose identities have not been protected (60.7% and 56.3%, respectively). In contrast, videos from the media are those that, to a greater extent (28%), respect protection of the children’s identities (that is, a technique is used to prevent them from being recognised, either by using shadow or by distorting or pixelating the images). However, they contain a higher percentage (35.4%) of forbidden for children.

3.2.2. Authorship and space

Following the YouTubers, where spaces considered to be private (80%) are shown in their videos, it is teen-authored videos which, to a greater extent, are recorded in private locations (31.7%) as compared to public places (16.7%). This takes into account that in 28.3% of cases there is a mixture of both types. The videos made by the media essentially present public spaces (the category includes television studios) given that they represent 82.9% of the videos belonging to these entities. Besides, the videos made by institutions, there is consistency in those from public institutions (33.3% in public spaces compared to 44.4% in non-detectable spaces), which use private locations rarely. Private institutions mainly record in public places (52.6%).

3.2.3. Authorship and vulnerability

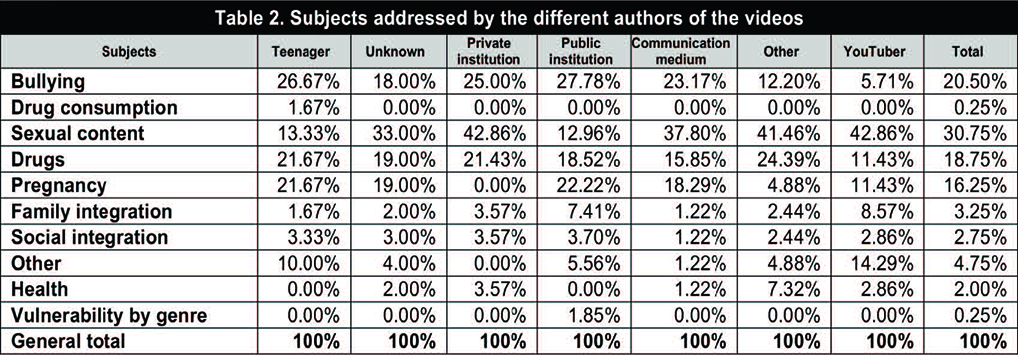

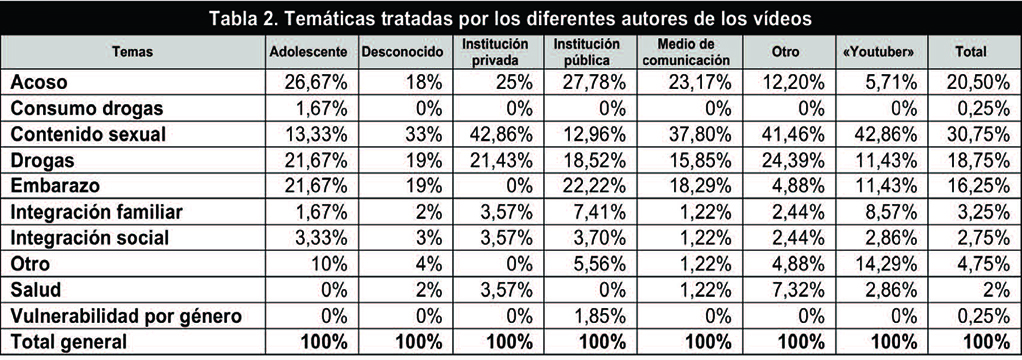

One of the crucial elements has to do with issues linked to vulnerability. In this respect, 26.67% of the teenauthored videos tackle in one way or another the subject of bullying, which features as the issue paid the most attention. The next most important issues for this group are drugs (21.67%) and pregnancy (21.67%). Fourth place is taken by the videos containing sexual content (13.33%). No relevant figures were offered by the remaining aspects. In comparative terms, when the author of the video is a YouTuber, the content is fundamentally of sexual nature (42.86%), followed at some distance by content related to drugs or pregnancies (in both cases, 11.43%). Sexual content (37.80%) is also deemed a more prominent subject in videos from the media. In the second place, the audience can access media-made videos that address the question of bullying (23.17%), followed by those that reflect some aspect of pregnancy (18.29%).

3.3. Characteristics of the audiovisual content3.3.1. Authorship and genre

Compared to the rest of the groups or institutions analysed, teenagers show great diversity as regards the genre of the videos they upload to YouTube. “Choreographies” predominate, representing 38.3% of the total number of their videos, followed by “remixes” (25%). Next, and in a less significant proportion of their videos, are “selfies” and “fun stuff”, both with 13.3%. From this data, it is possible to deduce the recreational purpose of the audiovisual offerings from the adolescents. These results were not repeated in the other categories. YouTubers show a fundamental inclination towards selfies, amounting to 54.3%, while the media opt mainly (91.5%) for items of journalism.

3.3.2. Authorship and structure

The majority of the teen-authored videos have a declarative structure (55.7%) followed at some distance by those using the imperative style (27.9%). In the videos from the media, practically all have a declarative structure (89.0%). The same is true with those made by YouTubers, although more than ten percentage points less (77.1%). It could be stated that the predominant style of these three groups is far from an imperative structure (videos that include orders that lead to action) or an interrogative/reflexive structure (videos that pose questions or stir the conscience), as they opt more for an aseptic (or declarative) model offering.

3.3.3. Authorship, focus, and duration

Another aspect addressed has to do with the focus (positive, negative, neutral or indeterminate) of the videos depending on authorship. In this respect, it can be observed that the videos made by public institutions, in the first place, and by teenagers, in second place, are those offering a more significant percentage of positive messages (in which there is an attempt to solve a problem).

There is symmetry between the positive and neutral focus (those videos which just explain the situation) in the videos made by the media or YouTubers. Those with the most negative tone (when solutions to the problem are rejected without any alternative solutions being contributed) of all the videos are those made by YouTubers, even though they constitute a minority (11.4%) of their videos.

Concerning duration, all the authors show their predilection for videos lasting between 1 and 10 minutes (this range accounts for over 74% of the videos). If we subdivide this category into two (videos lasting 1-5 minutes and those lasting 5-10 minutes), while the YouTubers mostly opt for videos between 5-10 minutes long, the remaining authors have a preference for videos lasting 1-5 minutes.

3.4. Popularity of the videos and degree of interaction 3.4.1. Authorship and “likes”

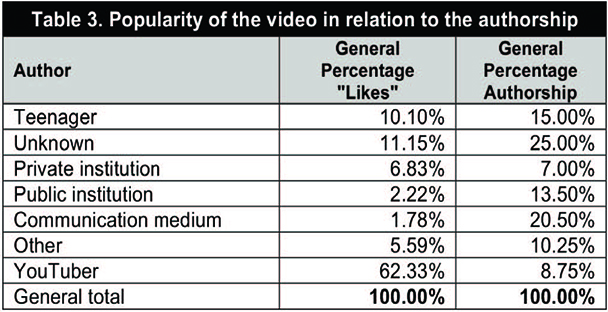

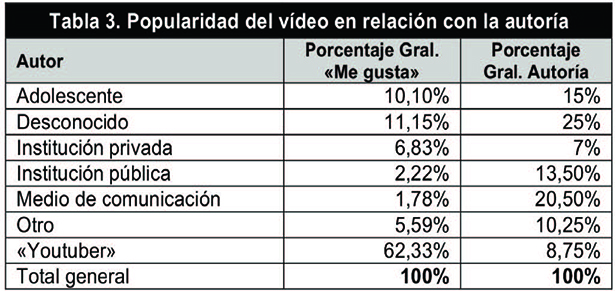

According to the results obtained, videos by teenagers, which represent 15% of the total number of audiovisual items, only account for 10.10% of the “likes” detected. As regards videos made by YouTubers, although these only represent 8.75% of the total number of videos, they have 62.33% of the “likes”. By contrast, the videos from the media, which constitute the highest percentage of videos with known authorship (20.50%), only account for 1.78% of “likes”. In short, it can be stated that videos by YouTubers generate a very positive reaction, from which it can be deduced there is a greater ability to get a reaction (possibly of forming some community) and, to a certain extent, to click with the tastes and trends of the audience. This would occur to a lesser extent in the case of videos made by teenagers, although there are some noteworthy results.

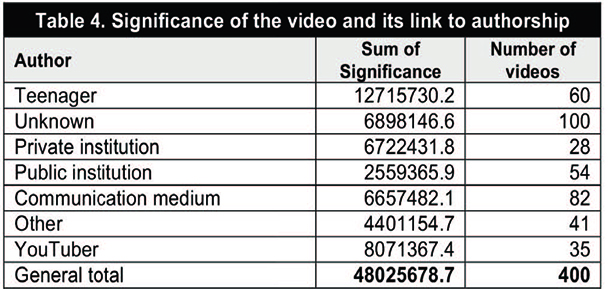

3.4.2. Authorship and significance

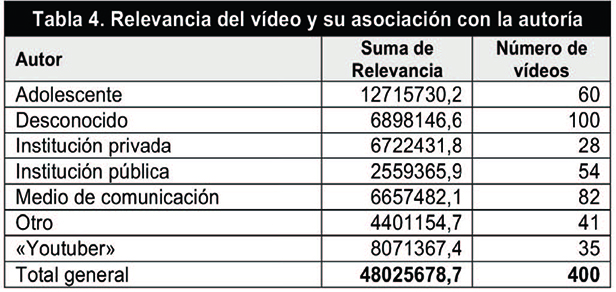

Concerning the data obtained on “likes” and in absolute terms, teen-authored videos are the most viewed: their 60 videos received nearly 13 million views. They are followed by the YouTubers, who obtained, with just 35 videos, 8 million views (representing the highest ratio). Meanwhile, the media, despite having more videos (82), obtained approximately half of the number of views received by the teenagers’ videos (6.6 million). Once again, it is possible to observe the greater significance in percentage terms of the videos made by YouTubers. However, the total figure obtained by the teenagers’ offerings gives clear proof of their ability to create an impact.

Another way of defining their significance comes from analysing the number of views. Those demonstrating the most success are those made by YouTubers, as almost half of their videos are among those with over one million visits. In the case of videos made by one or several teenagers, 45% of the documents analysed had 25,000 views. However, the sum of the remaining categories, that is, videos obtaining more than 25,000 visits, make up the remaining 55% of their videos.

3.4.3. Authorship and comments

The videos causing a greater impact, regarding comments generated, are those made by YouTubers, which stand out from the rest as regards both absolute data (67.66%) and relative data when comparing authorship category percentages. This is the only category analysed in which this occurs. In the remaining categories, the percentage of comments is lower, relatively speaking, than the authorship percentage recorded. In the case of teenagers, it accounts for 7.27% of the total number of comments. Also, in absolute terms, they are of the “unknown” authorship category. These data show it is videos by YouTubers which elicit support, debate or also censure from their audience.

4. Discussion, conclusions, and limitations

This study aims to gain more knowledge about the ways teenagers interact in the digital environment. The study does not seek to detect extremes such as cyber bullying. However, it does confirm, from the beginning, that situations of vulnerability that occur for adolescents both in creating and consuming audiovisual material fall with four major thematic areas: sex, drugs, bullying, and pregnancy.

Authorship has been demonstrated to be the variable which most explains the results, with the results obtained by institutional videos (e.g., campaigns to prevent the use of drugs or about anorexia) being totally at odds with the audiovisual content created by teenagers and young people. The studies on the potential factors for risk and anxiety among children and teenagers also indicate the central nature of empathy. Videos made by young people in emotional situations which are familiar and seem authentic trigger the strongest empathy among the young. In contrast, the study has also established that institutional videos are not greatly accepted or circulated among the teenage public. YouTube is a field chiefly dominated by young people with young codes.

The content study conducted not only complements the conclusions of the research into the subject and quantifies its potential impact (videos by adolescents are watched twice as much, and those by YouTubers are those with the greatest impact). It also shows the gaps between codes are profound, which makes audiovisual communication between adolescents, young people, and adults extremely difficult. Evidently, the recreational purpose of the audiovisual offerings by teenagers (the genres of “choreographies”, “remixes”, “selfies” and “fun stuff” in general) contrasts with the seriousness of the adults’ audiovisual offerings. However, above all, it is lack of perception about the conditions of vulnerability (perhaps only slightly less on the subject of bullying) which shows how the codes of adults and those of teenagers as regards identifying risk differ very widely. Videos created by teenagers offer a greater percentage of items in which it is possible to observe unprotected children and teenagers; the videos by YouTubers and teenagers are those recorded to a greater extent in private settings as opposed to public places.

In all the subjects, the predominating structure is an aseptic, declarative, model structure. It is only in the case of videos on bullying where there is a significant percentage (almost half) of videos that address the audience in an imperative manner or call upon the recipients in a questioning (interrogative) or reflexive fashion. If to this we add a clear predominance of positive or neutral videos, we get a picture of a lack of problematisation, that is, a scenario of normality. The adolescents “take for granted” certain codes which, in circumstances of vulnerability, should perhaps become problematised.

In sum, the outlined research into content shows videos made by young people for young people which are entertaining, normalised, unconcerned with potential situations of vulnerability and present themselves, perhaps dangerously, as simple spaces for asserting their adolescence.

The criticism that can be made of this conclusion is that we do not know to what extent young people can de-codify as having been made as an investment or for “fun” a good part of the material which can be seen as “dangerous” from the perspective of its content. Moreover, much less can we calculate the effect its message, as they de-codify it, may have. From our point of view, future research should look deeper into this issue.

For example, the General Aggression Model (GAM) of Anderson and Bushman (2001) makes it possible to predict, with considerable empirical support, aggressive conduct by children. It accepts that both the personal variables and the situation-related variables (including exposure to violence in the real world, in the media or online) influence the current internal state of an individual (Kirsh, 2010; 2012). In the same vein, a more thorough research should work towards a Model of Adolescent and Youth Vulnerability that includes the viewing of unsuitable material among the risks to which children and adolescents are exposed. What we seek to do is to identify the codes of the interaction of teenagers in the digital environment and the content liable to cause potential vulnerability, although the materialisation of situations of vulnerability is reliant on a complex maze of variables.

Funding agency

This study is part of the activities of the PROVULDIG Digital Vulnerability Programme (S2015/HUM3434) funded by the Madrid Autonomous Community (Spain) on Social Sciences and Humanities and the European Social Fund (2016-2018).

References

Abisheva, A., Kiran-Garimella, V.R., García, D., & Weber, I. (2014). Who watches (and shares) what on YouTube? And when?: Using twitter to understand YouTube viewership. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, 593-602. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556195.2566588

Aguaded, I., & Sánchez, J. (2013). El empoderamiento digital de niños y jóvenes a través de la producción audiovisual. AdComunica, 5, 175-196. https://doi.org/10.6035/2174-0992.2013.5.11

Álvarez-García, D., Barreiro-Collazo, A., & Nuñez, J.C. (2017). Cyberaggression among adolescents: Prevalence and gender differences. [Ciberagresión entre adolescentes: Prevalencia y diferencias de género]. Comunicar, 50(XXV), 89-97. https://doi.org/10.3916/C50-2017-08

Anderson, C.A., & Bushman, B.J. (2001). Effects of violent video games on aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, aggressive affect, physiological arousal, and prosocial behavior: A meta-analytic review of the scientific literature. Psychological Science, 12, 353-359. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00366

Bañuelos, J. (2009). YouTube como plataforma de la sociedad del espectáculo. Razón y Palabra, 69, 1-68. (https://goo.gl/XJpyrz).

Barry, A., Johnson, E., Rabre, A., Darville, G., Donovan, K., & Efunbumi, O. (2015). Underage access to online alcohol marketing content: A YouTube case study. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 50(1), 89-94. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agu078

Berrocal, S., Campos, E., & Redondo, M. (2014). Media prosumers in political communication: Politainment on YouTube. [Prosumidores mediáticos en la comunicación política: El ‘politainment’ en YouTube]. Comunicar, 43(XXII), 65-72. https://doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-06

Blais, J., Craig, W., Pepler, D., & Connolly, J. (2008). Adolescents online: The importance of Internet activity choices to salient relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 522-536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9262-7

Bleakley, A., Ellithorpe, M., & Romer, D. (2016). The role of parents in problematic internet use among US adolescents. Media and Communication, 4(3), 24-34. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v4i3.523

Blomfield, C.J., & Barber, B.L. (2014). Social networking site use: Linked to adolescents’ social self-concept, self-esteem, and depressed mood. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66, 56-64. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12034

Chau, C. (2010). YouTube as a participatory culture. New Directions for Youth Development, 128, 65-74. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.376

De-Frutos, B., & Marcos, M. (2017). Disociación entre las experiencias negativas y la percepción de riesgo de las redes sociales en adolescentes. El Profesional de la Información, 26(1), 88-96. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.ene.09

Días-da-Silva, P., & Garcia, J.L. (2012). YouTubers as satirists: Humour and remix in online video. eJournal of eDemocracy and Open Government, 4(1), 89-114. (https://goo.gl/PHM6Ul).

Edwards, L., Kontostathis, A., & Fisher, C. (2016). Cyberbullying, race/ethnicity and mental health. Media and Communication, 4(3), 71-78. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v4i3.525

Franco, E.C. (2017). Redes sociales libres en la universidad pública. Revista Digital Universitaria, 18(1). (https://goo.gl/5ptkf1).

Fuente-Cobo, C. (2017). Públicos vulnerables y empoderamiento digital: El reto de una sociedad e-inclusiva. El Profesional de la Información 26(1), 5-12. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.ene.01

García-Jiménez, A., Catalina-García, B., & López-de-Ayala-López, M.C. (2016). Adolescents and YouTube: Creation, participation and consumption. Prisma Social, n. extra, 60-89. (https://goo.gl/qNifJN).

Halliday, M.A.K. (2004). An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Edward Arnold.

Igartua, J.J. (2006). Métodos cuantitativos de investigación en comunicación. Barcelona: Bosch.

Jenkins, J., Ford, S., & Green J. (2015). Cultura transmedia, la creación de contenido y valor en una cultura en red. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Jiménez, C., & Gaitán, B.N. (2013). Análisis de los factores que motivan a los estudiantes de la Universidad Autónoma de Occidente a difundir contenidos virales en la Red. Cali (Colombia): Universidad Autónoma de Occidente. (https://goo.gl/0jP6tH).

Karlsen, R., Borrás-Morell, J., & Traver-Salcedo, V. (2017). Are trustworthy health videos reachable on YouTube? - A study of YouTube ranking of diabetes health videos. In Proceedings of the 10th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2017) - Volume 5: Healthinf, 17-25. https://doi.org/10.5220/0006114000170025

Kirsh, S.J. (2010). Media and youth: A developmental perspective. Malden (Massachusetts): Wiley-Blackwell.

Kirsh, S.J. (2012). Children, adolescents, and media violence: A critical look at the research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lenhart, A., Smith, A., Anderson, M., Duggan, M., & Perrin, A. (2015). Teens, technology and friendships. Pew Research Center. (https://goo.gl/PHq81a).

Livingstone, S., Kirwil, L., Ponte, C., & E. Staksrud, E. (2014). In their own words: What bothers children online? European Journal of Communication, 29(3), 271-288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323114521045

López-Vidales, N., & Gómez-Rubio, L. (2015). Análisis y proyección de los contenidos audiovisuales sobre jóvenes y drogas en YouTube. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 21(2), 863-881. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_ESMP.2015.v21.n2.50889

Martínez-Pastor, E., Sendín-Gutiérrez, J.C., & García-Jiménez, A. (2013). Percepción de los riesgos en la red por los adolescentes en España: Usos problemáticos y formas de control. Análisi, 48, 111-130. (https://goo.gl/ao3odb).

McRoberts, S., Bonsignore, E., Peyton, T., & Yarosh, S. (2016). Do It for the viewers!: Audience engagement behaviors of young YouTubers. In Proceedings of the The 15th IDC International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, 334-343. https://doi.org/10.1145/2930674.2930676

Misoch, S. (2014). Card Stories on YouTube: A New Frame for Online Self-Disclosure. Media and Communication, 2(1), 2-12. (https://goo.gl/W5OsRt).

O’Keeffe, G., & Clarke-Pearson, K. (2011). The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics, 127, 800-804. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0054

Protégeles (Ed.) (2014). Menores de edad y conectividad móvil en España: Tablets y smartphones. (https://goo.gl/pBaMvV).

Ritzer, G., & Jurgenson, N. (2010). Production, Consumption, Prosumption: The nature of capitalism in the age of the digital ‘prosumer’. Journal of Consumer Culture, 10(1), 13-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540509354673

Ritzer, G., Dean, P., & Jurgenson, N. (2012). The Coming of Age of the Prosumer. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(4), 379-398. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211429368

Sabater, C. (2014). La vida privada en la sociedad digital. La exposición pública de los jóvenes en Internet. Aposta, 61, 1-32. (https://goo.gl/0HRnyI).

Subrahmanyam, K., Greenfield, P., & Michikyan, M. (2015). Comunicación electrónica y generaciones adolescentes. Infoamérica, 9, 115-130. (https://goo.gl/uvP9R7).

Syed-Abdul, S., Fernandez-Luque, L., Jian, W.S., Li, Y.C., Crain, S.,… Liou, D.M. (2013). Misleading health-related information promoted through video-based social media: Anorexia on YouTube. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(2), e30. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2237

Wartella, E., Rideout, V., Montague, H., Beaudoin-Ryan, L., & Lauricella, A. (2016). Teens, Health and Technology: A National Survey. Media and Communication, 4(3), 13-23. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v4i3.515

Yarosh, S., Bonsignore, E., McRoberts, S., & Peyton, T. (2016). YouthTube: Youth video authorship on YouTube and Vine. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 1423-1437. https://doi.org/10.1145/2818048.2819961

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Como un mecanismo de participación e integración social y con el propósito de construir su identidad, los adolescentes realizan y comparten vídeos en plataformas como YouTube, de la que también son consumidores de contenido. Las condiciones de vulnerabilidad que tienen lugar y los riesgos a los que se exponen los adolescentes, tanto como creadores como consumidores de vídeos, son el objeto central de este estudio. La metodología utilizada es el análisis de contenido, aplicado a 400 vídeos. Se ha trabajado con variables manifiestas (como el escenario) y latentes (como el género o la estructura). Los resultados muestran unas notables diferencias de estilo entre los vídeos a tenor del productor del mensaje e indican que los vídeos más consumidos se sitúan alrededor de cuatro ejes temáticos (sexo, acoso, embarazo y drogas) y que los referentes como creadores de contenido audiovisual son los «youtubers». Todo apunta a la existencia de problemas a la hora de utilizar el lenguaje, también audiovisual, de los adolescentes. Este trabajo proporciona evidencias de la conveniencia de emplear sus códigos para que este sector de la población se percate de los riesgos y de las condiciones de vulnerabilidad que parecen no percibir según sus creaciones audiovisuales, en las que, entre otras características, no protegen su identidad.

1. Introducción, estado de la cuestión y objetivos

Esta investigación tiene como objeto de estudio las elaboraciones audiovisuales dirigidas a adolescentes, realizadas por ellos mismos o por otros agentes, a través de la plataforma YouTube. Para ello se toman como factores clave la vulnerabilidad (Fuente-Cobo, 2017) y los riesgos asociados al consumo, la elaboración y la exposición de este tipo de contenidos por parte de este sector de la población (O’Keeffe & Clarke-Pearson, 2011).

El contexto electrónico ha influido en los problemas tradicionales de la adolescencia a causa del «aumento de la comunicación en línea, por la existencia de redes de pares más amplias y por las mayores oportunidades para la autopresentación y la exploración de la identidad» (Subrahmanyam, Greenfield, & Michikyan, 2015: 126). Cuando los estudios siguen alertando de un mayor porcentaje de condiciones para la adicción al uso de Internet, especialmente por parte de los jóvenes (Bleakley, Ellithorpe, & Romer, 2016), se hace imprescindible conocer cómo interactúa el adolescente con el entorno digital (Blomfield & Barber, 2014), un medio en el que se desarrollan fenómenos como el «cyberbullying» (Edwards, Kontostathis, & Fisher, 2016) o la ciberagresión, siendo el vídeo una de las herramientas con la que se produce (Álvarez-García, Barreiro-Collazo, & Nuñez, 2017).

La investigación continúa la línea centrada en los riesgos, definida por los estudios en EU-Kids Online, encabezados por Sonia Livingstone. Por otra parte, se avanza específicamente en las situaciones de vulnerabilidad que acaecen tanto en la creación como en el consumo de material audiovisual por parte de los adolescentes.

Entre los riesgos a que se exponen los menores destaca la visualización de material inapropiado. Los contenidos difundidos en YouTube son de índole muy diversa y con intenciones muy variadas, no siempre positivas. Según el estudio de Livingstone y otros (2014) casi un tercio de los adolescentes afirma haber visualizado un material que no era de su agrado, siendo lo más frecuente la exposición a vídeos violentos o pornográficos. En el trabajo de Yarosh y otros (2016), que registra y compara las temáticas aparecidas en dos plataformas como YouTube y Vine, se observa que en esta última aparece un mayor porcentaje de vídeos de contenido sexual, violento u obsceno. También supone un riesgo la exposición a ciertas ofertas comerciales difundidas en redes como YouTube, Facebook o Twitter ya que estudios como el de Barry y otros (2015) demuestran que a través de estos medios los menores pueden quedar expuestos a contenidos que promocionan bebidas alcohólicas.

También es preocupante el nivel de credibilidad que el menor puede otorgar al contenido de ciertos vídeos, especialmente si estos versan sobre temas delicados como los de salud. Existen ya estudios al respecto en relación al rigor presente en vídeos sobre la anorexia, analizado por Syed-Abdul y otros (2013) o la menor visibilidad que logran los vídeos sanitarios de fuentes fiables, elaborado por Karlsen, Borrás-Morell y Traver-Salcedo (2017), que hacen necesario un replanteamiento sobre la pertinencia de protocolos de filtrado de este tipo de material, para evitar que ciertos contenidos alcancen elevadas cuotas de difusión y popularidad. Esto es más relevante si cabe cuando investigaciones como las de López-Vidales y Gómez-Rubio (2015) indican que los vídeos institucionales (en este caso los que tratan el tema de las drogas) no logran una gran aceptación o divulgación entre el público adolescente.

Por lo que respecta a la vulnerabilidad, los adolescentes son un público especialmente vulnerable ya que a pesar de estar informados sobre los riesgos de Internet, que consideran un espacio abierto a un público desconocido, perciben de manera distinta entornos como el de las redes sociales, que consideran más seguro, privado y alejado de los peligros vinculados a Internet (Martínez-Pastor, Sendín-Gutiérrez, & García-Jiménez, 2013; Sabater, 2014). Una percepción que, según Blais y otros (2008), se sustenta en que las aplicaciones que posibilitan la comunicación directa e individualizada, como las de mensajería instantánea, incrementan la confianza y la sensación de intimidad aunque el entorno en el que estas operan sea el de Internet. A esto se añade que existe una disociación entre las experiencias negativas que los adolescentes han vivido en el entorno de las redes sociales y la valoración del riesgo que supone su uso (De-Frutos & Marcos, 2017).

Con el propósito de la construcción de una identidad y de la participación e integración social, los adolescentes elaboran vídeos que comparten y difunden a través de redes sociales o en plataformas específicas como YouTube, que posibilitan que sus creaciones tengan una mayor difusión. Las repercusiones de las emisiones implican a todo tipo de ámbitos desde el social (Abisheva & al., 2014) o cultural (Bañuelos, 2009; Chau, 2010) ya que se experimentan con nuevas formas de comunicación y estilos audiovisuales (Misoch, 2014), pasando por asuntos de salud pública (Wartella & al., 2016), temas políticos (Dias-da-Silva & Garcia, 2012) o cuestiones económicas (Ritzer & Jurgenson, 2010), entre otros. Tal y como exponen Jenkins, Ford y Green (2015): «cada vez que un adolescente crea una «fanfiction» de Harry Potter sube el valor de la marca Harry Potter y cada vez que un fan comparte en YouTube una parodia de Star Wars se incrementan las acciones de ese mundo narrativo en el reino de los activos intangibles» (Jenkins, Ford, & Green, 2015: 10), es decir, estos actos afectan a áreas tan diversas como la económica o la cultural.

YouTube es una plataforma que cuenta con contenido destinado específicamente para adolescentes, siendo el acceso a esta red social una de las primeras acciones que efectúa un individuo cuando se inicia en el dominio digital, con independencia del dispositivo empleado para la conexión (Protégeles, 2014). Puesto que los adolescentes no consumen únicamente materiales audiovisuales creados por ellos mismos, en este estudio nos ocuparemos también de las producciones difundidas por otros agentes como son los medios de comunicación o los «youtubers». Estos últimos ejercen una gran influencia entre los adolescentes como se desprende de las conclusiones del estudio de McRoberts y otros (2016) ya que los menores imitan las pautas creativas de los profesionales, aunque no tengan una edición de vídeo o no logren un posicionamiento a través de los metadatos como el de los «youtubers».

Los niveles de participación de los usuarios de YouTube son muy diversos. En algunos ámbitos, como la política, el ingente consumo de materiales de esta temática no va acorde con acciones masivas de producción. En este caso, predominan los usuarios pasivos y es frecuente el hecho de compartir vídeos ya emitidos en otros medios como la televisión (Berrocal, Campos, & Redondo, 2014) en vez de crear los propios. Se encuentran prosumidores más activos grabando y compartiendo mensajes audiovisuales en otras áreas como la cultural o social. Incluso YouTube se convierte en una herramienta eficaz para la faceta educativa y hasta para la divulgación científica, mediante la transmisión en directo de eventos académicos (Franco, 2017), entre otras posibilidades.

En definitiva, analizaremos el contenido de los vídeos destinados a los adolescentes con el fin de determinar las temáticas de interés, averiguar quiénes son sus autores, los estilos de la comunicación y así delimitar a qué riesgos se ven expuestos y también los factores de vulnerabilidad que concurren, tanto en el consumo como en la elaboración y difusión de estos materiales, cuando son realizados por los propios adolescentes, un sector de la población activo en todas las facetas: creativa, participativa y consumidora (García-Jiménez, Catalina-García, & López-de-Ayala, 2016). Los objetivos de este trabajo son:

a) Identificar las situaciones de vulnerabilidad y los riesgos subyacentes en los vídeos realizados y difundidos por los propios adolescentes.

b) Analizar las características de las creaciones audiovisuales en términos de orientación, su estilo-género, así como otros aspectos relativos al nivel de impacto a partir de indicadores como el número de visualizaciones, los «me gusta» o «no me gusta» y los comentarios generados.

c) Determinar qué contenidos (temáticas) están dirigidos a los adolescentes en YouTube, cómo están construidos, a partir de su género, orientación y estructura, y cuáles son los más consumidos (número de «me gusta», visualizaciones o comentarios). Puesto que el acceso a los vídeos en YouTube se realiza mediante filtros de popularidad se pretende analizar la idoneidad de estos contenidos, el riesgo de consumir material no apto para menores o el tratamiento que reciben algunos temas que pueden conducir a situaciones de riesgo. En este caso, tendremos en cuenta especialmente dos tipos de productores de contenidos audiovisuales que se postulan como básicos a la hora de definir la realidad comunicativa de los adolescentes: los «youtubers», puesto que logran producciones con elevadas cuotas de popularidad y los medios de comunicación, cuyos vídeos son elaborados por profesionales del medio audiovisual, pero con menor repercusión en YouTube.

2. Material y métodos

YouTube es un canal propicio para divulgar mensajes ya que se ha convertido en un foro de dimensiones planetarias (Jiménez & Gaitán, 2013). A través de este estudio se pretende conocer qué tipo de audiovisuales, dirigidos a adolescentes, están disponibles en esta red social, que podemos catalogar como tal, puesto que permite a jóvenes y a adolescentes mostrar sus intereses y contactar con otros iguales que los compartan (Lenhart & al., 2015). Entre los productores de los vídeos estarán los elaborados por los propios adolescentes que demandan su espacio y cuota de protagonismo (Aguaded & Sánchez, 2013).

2.1. Metodología

En esta investigación se ha utilizado la técnica del análisis de contenido que posibilita la recogida de datos cuantitativos comparables y reiterables, así como su posterior cotejo con el fin de identificar si ciertos factores o «clusters» los relacionan o disocian. Al tratarse de unidades audiovisuales se han registrado, según la terminología de Igartua (2006), tanto variables manifiestas (como el espacio de la representación, la presencia de menores o la protección de la identidad) como variables latentes (la estructura, el género o la orientación, entre otras).

El protocolo y los indicadores empleados se basan, con un cierto grado de adaptación, en anteriores trabajos como el de Yarosh y otros (2016), centrado en el contenido audiovisual publicado por los adolescentes, o el de Halliday (2004) al respecto de la estructura modal de los vídeos. En distintas fases de la investigación se ha verificado el protocolo de actuación que ha permitido el estudio de los componentes formales, narrativos, temáticos o valorativos de los contenidos audiovisuales.

Finalmente, las variables registradas en esta investigación han sido: enlace y dirección del vídeo, fechas de consulta (localización y visionado del vídeo por parte de los investigadores) y de publicación del vídeo, descripción (si la contiene o no), categoría (según modalidades de YouTube), título, autoría, usuario (que aloja el vídeo), duración, género o formato (valores ampliados de Yarosh & al., 2016), aparición del menor (y si hay protección o no de su identidad en los casos en que aparece), estructura (declarativa, imperativa o interrogativa; basada en Halliday, 2004), orientación (positiva, negativa, neutra o indeterminada), presencia de contenidos relacionados con la vulnerabilidad y los riesgos, temática, espacio de la representación (privado o público), tres variables alusivas a la interacción que suscita (cantidad de «me gusta», «no me gusta» y comentarios) y, por último, el número de reproducciones (relevancia).

2.2. Definición de la muestra

La determinación de los audiovisuales que han sido objeto de estudio se realizó a través de un proceso selectivo con etiquetas. El estudio se proponía analizar vídeos elaborados por los adolescentes, si bien no quería limitarse a estos autores. No obstante, para favorecer la localización de sus producciones se realizó en el sitio web de YouTube una búsqueda entrecomillando la expresión «vídeos de adolescentes» (más específica para este fin que si se empleaba únicamente el término «adolescentes»).

Si bien plataformas como YouTube promueven usuarios activos, que no solo se limiten a consumir sino que también produzcan contenidos (Ritzer, Dean, & Jurgeson, 2012), no resulta sencillo para un adolescente obtener visibilidad y lograr cierta repercusión de los contenidos que sube a YouTube. Teniendo en cuenta los objetivos del estudio, se optó por ordenar el resultado de la búsqueda en función del número de reproducciones -aunque esto dificultase que formasen parte de la selección vídeos realizados por los propios adolescentes- y se definió una primera muestra de 100 vídeos. A pesar de que en estudios como el de Karlsen, Borrás-Morell y Traver-Salcedo (2017) se manifiesta la pertinencia de implementar otras variables en el mecanismo de búsqueda interna de YouTube, que favorezcan la ordenación y localización de los contenidos mediante otros enfoques diferentes al número de visualizaciones o la popularidad del vídeo (como la credibilidad de la fuente), se optó por el número de visualizaciones por ser el modo actual más claro para garantizar un mínimo grado de difusión de los vídeos analizados.

El factor idiomático también condicionó la muestra, que se centró en audiovisuales en castellano. Con el propósito de analizar unidades de cierta actualidad, la muestra se conformó con vídeos alojados en YouTube a partir de 2010. Se dejó este margen de años ya que para lograr un número relevante de visualizaciones el audiovisual suele necesitar cierto tiempo de presencia en la plataforma, a pesar de lo cual entre los 100 vídeos de la muestra inicial solo dos vídeos tenían tal antigüedad en su fecha de subida.

Una vez aplicados los condicionantes referidos, se testaron las variables del protocolo de análisis, lo que permitió depurar ciertos valores así como descartar algunas variables (cuyos resultados no serían significativos debido a la diversidad de la autoría) y se registraron las temáticas presentes en los 100 vídeos que compusieron la muestra inicial.

Tras localizar, en este grupo inicial, cuatro temáticas redundantes (sexo, drogas, acoso y embarazo), se incrementó la muestra hasta llegar a los 400 audiovisuales, si bien los nuevos 300 vídeos incorporados al estudio se centraron exclusivamente en estos temas recurrentes a partir de las etiquetas «adolescentes sexo», «adolescentes drogas», «embarazo adolescente» y «adolescentes acoso». Como se puede apreciar en la literatura científica, estas temáticas están en sintonía con las líneas marcadas por los investigadores del área: las relaciones sexuales (sexo, embarazo), el consumo de sustancias perniciosas (alcohol o drogas, entre otras) y las situaciones de acoso y violencia. Estudios como los de Livingstone y otros (2014), Barry y otros (2015), López-Vidales y Gómez-Rubio (2015), Edwards, Kontostathis y Fisher (2016), Yarosh y otros (2016) y Álvarez-García, Barreiro-Collazo y Nuñez (2017) corroboran que las mencionadas temáticas son de interés prioritario para los adolescentes.

3. Análisis y resultados

3.1. Autoría

Tal y como se ha comentado se ha optado por la determinación de la autoría del vídeo (de origen). Esta tarea presenta algunas dificultades, por lo que no resulta extraño que la primera categoría sea la de «desconocido» con un 25,3%. Cuando el contenido del vídeo o la información facilitada por el usuario que lo aloja no permitían concretar la autoría se optó por registrar el valor «desconocido». En segundo lugar, los vídeos subidos por medios de comunicación representan el 20,3% seguidos de un 15,1% cuyo autor es un adolescente.

Por otra parte, existen dos colectivos intermedios como son los «youtubers» (la mayoría jóvenes) que representan el 8,8% del total de vídeos analizados y, a continuación, las instituciones públicas, que difunden esencialmente campañas con vistas a sensibilizar a la sociedad sobre algún aspecto considerado de interés. Los adultos o profesionales (10,3%) suben menos vídeos que los adolescentes, lo que demuestra que YouTube es un campo mayoritariamente dominado por jóvenes.

3.2. Condiciones de vulnerabilidad3.2.1. Aparición de menores

En este estudio también se ha analizado cómo aparecen los menores, aunque se ha de tener en cuenta que, en determinados tramos de edad, resulta complejo encajar el posible año de nacimiento de las personas que aparecen en las piezas audiovisuales. En este caso, se puede observar que en los vídeos planteados por los adolescentes es donde menos se protege (68,3%) la identidad del menor. También destaca el hecho de que tanto en las instituciones privadas como en las de naturaleza pública sea alto el porcentaje de documentos en los que es posible ver menores no protegidos (60,7% y 56,3% respectivamente). Frente a esto, los vídeos que proceden de medios de comunicación son los que, en mayor medida (28%), respetan la protección de la identidad del menor (es decir, se utiliza alguna técnica para que no sean reconocidos, ya sea, mediante sombras o a través de la distorsión o el pixelado de las imágenes), aunque presenten en un porcentaje mayor (35,4%) a menores no protegidos.

3.2.2. Autoría y espacio

Después de los «youtubers», en cuyos vídeos se ven espacios considerados privados (80%), son los vídeos de adolescentes los que, en mayor medida, se graban en sitios privados (31,7%) frente a lugares públicos (16,7%), teniendo en cuenta que en un 28,3% de los casos hay una mezcla de ambas modalidades. Por su parte, los vídeos realizados por los medios de comunicación presentan fundamentalmente espacios públicos (categoría en la que se han incluido los platós de televisión) puesto que suponen el 82,9% de los vídeos pertenecientes a estas entidades. En cuanto a los vídeos realizados por instituciones hay homogeneidad en las de carácter público (33,3% en espacios públicos frente al 44,4% en espacios no detectables), que apenas emplean espacios privados. Las instituciones de carácter privado graban fundamentalmente en lugares públicos (52,6%).

3.2.3. Autoría y vulnerabilidad

Uno de los elementos cruciales tiene que ver con los temas vinculados a la vulnerabilidad. En este sentido, en el 26,67% de vídeos de adolescentes abordan de una forma u otra el tema del acoso, que se nos presenta como el tema al que se presta mayor atención. A continuación, las drogas (21,67%) y el embarazo (21,67%) aparecen como problemáticas de calado para este colectivo. En cuarto lugar, sobresalen las piezas con contenido sexual (13,33%). El resto de aspectos no ofrecen cifras relevantes. En términos comparativos, cuando el autor del vídeo es un «youtuber», el contenido es fundamentalmente de naturaleza sexual (42,86%), seguido ya a mucha distancia por los relacionados con la droga o los embarazos (en ambos casos, 11,43%). También en los vídeos que proceden de los medios de comunicación lo sexual (37,80%) se estima como un tema más relevante. En segundo lugar, la audiencia puede acceder a vídeos que tratan la cuestión del acoso (23,17%), seguido de aquellos que reflejan algún aspecto del embarazo (18,29%).

3.3. Características de los audiovisuales3.3.1. Autoría y género

Frente al resto de colectivos o instituciones analizados, los adolescentes presentan una gran diversidad en cuanto al género del vídeo que suben a la plataforma YouTube. En cualquier caso, predominan las «coreografías», con un 38,3% del total de vídeos y un 25% de «remezclas». A continuación, ya con menor relevancia, aparecen los «selfies» y las «cosas divertidas», ambos con un 13,3%. De estos datos se puede derivar el afán lúdico de las propuestas audiovisuales de los adolescentes. Estos resultados no se repiten en el resto de categorías. Así, los «youtubers» muestran una inclinación fundamental por los «selfies», con un 54,3% y los medios de comunicación optan mayoritariamente (91,5%) por la pieza periodística.

3.3.2. Autoría y estructura

La mayoría de los vídeos realizados por adolescentes tienen una estructura declarativa (55,7%) seguida a gran distancia por la imperativa (27,9%). En los vídeos que pertenecen a los medios de comunicación prácticamente la totalidad es de estructura declarativa (89%). Sucede lo mismo con los realizados por «youtubers», aunque más de diez puntos por debajo (77,1%). Se podría afirmar que el estilo preponderante en los tres colectivos se encuentra lejos de la estructura imperativa (vídeos que incluyen órdenes que mueven a la acción) o bien de la estructura interrogativa/reflexiva (vídeos que plantean preguntas o que mueven la conciencia) y apuestan más por una propuesta modal aséptica (o declarativa).

3.3.3. Autoría, orientación y duración

Otro de los aspectos abordados tiene que ver con la orientación (positiva, negativa, neutra o indeterminada) de los vídeos en función de la autoría. En este sentido, se puede observar que, en primer lugar, los vídeos realizados por las instituciones públicas y, en segundo lugar, los adolescentes son quienes ofrecen un porcentaje más relevante de mensajes positivos (en los que se trata de resolver un problema). Por su parte, existe una simetría entre la orientación positiva y neutra (aquellos vídeos en los que únicamente se explica el hecho) en los vídeos realizados por medios de comunicación o «youtubers». Los que tienen un tono más negativo (cuando rechaza soluciones al problema sin aportar alternativas) de todos son los realizados por «youtubers» aunque constituyen una minoría (11,4%).

Con respecto a la duración, todos los autores muestran su apuesta por vídeos cuya duración oscila entre 1 y 10 minutos (este rango acapara más del 74% de los vídeos). Si subdividimos esta categoría en dos (vídeos: entre 1-5 minutos y entre 5-10 minutos), salvo los «youtubers», que optan mayoritariamente por vídeos entre 5-10 minutos, el resto de autores se decanta preferentemente por vídeos entre 1-5 minutos.

3.4. Popularidad de los vídeos y grado de interacción 3.4.1. Autoría y los «me gusta»

Según los resultados obtenidos, los vídeos de adolescentes, que suponen el 15% del total de piezas audiovisuales, solo suman el 10,1% de los «me gusta» detectados. Por su parte, aunque los vídeos realizados por «youtubers» representan únicamente el 8,75% del total, acaparan el 62,33% de los «me gusta». En el lado opuesto, los vídeos pertenecientes a medios de comunicación, que suponen el porcentaje con autoría reconocida más importante (20,5%) solo presentan el 1,78% de los «me gusta». En definitiva, se puede afirmar que son los vídeos de los «youtubers» los que generan una reacción muy positiva, de lo que se puede deducir una mayor capacidad de propiciar alguna reacción (posiblemente de formar un tipo de comunidad) y, en cierta medida, de conectar con los gustos y tendencias de la audiencia. Esto ocurriría en menor medida en el caso de los vídeos realizados por adolescentes, aunque con alguna incidencia reseñable.

3.4.2. Autoría y relevancia

Frente a los datos obtenidos en relación con los «me gusta» y en términos absolutos, los vídeos de adolescentes son los más vistos: 60 vídeos acaparan cerca de 13 millones de visualizaciones. A continuación se sitúan los «youtubers» que obtienen, con solo 35 vídeos, 8 millones de visualizaciones (que supone la ratio más alta). Mientras, los medios de comunicación, aunque con más vídeos (82) obtienen aproximadamente la mitad de las visualizaciones que los vídeos de los adolescentes (6,6 millones). De nuevo se vuelve a observar una mayor relevancia porcentual por parte de los vídeos realizados por «youtubers». No obstante, la cifra total obtenida por las piezas de los adolescentes deja una evidencia clara de su capacidad de impacto.

Otro modo de delimitar la relevancia procede del análisis del número de visionados. Los que presentan más éxito son los elaborados por los «youtubers» pues casi la mitad de los vídeos se sitúan entre los que tienen más de un millón de visitas. Por su parte, en el caso de los vídeos con autoría de uno o varios adolescentes, un 45% de los documentos analizados obtienen menos de 25.000 visionados. No obstante, la suma del resto de categorías, es decir los vídeos que superan las 25.000 visitas, suponen el 55% restante.

3.4.3. Autoría y comentarios

Los vídeos que generan un mayor impacto, en términos de comentarios, son aquellos realizados por «youtubers», que destacan sobre el resto tanto en datos absolutos (67,66%) como en datos relativos, al comparar con el porcentaje de autoría. Es la única categoría analizada en la que ocurre este hecho. En el resto de categorías, el porcentaje de comentarios existentes es menor, relativamente hablando, que el porcentaje de autoría detectado. En el caso de los adolescentes, supone el 7,27% sobre el total de comentarios. Además, en términos absolutos, se encuentran detrás de la categoría «desconocido». Estos datos demuestran que son los vídeos de los «youtubers» los que realmente suscitan el apoyo, el debate o también la reprobación de la audiencia social.

4. Discusión, conclusiones y limitaciones

El propósito de la presente investigación es avanzar en el conocimiento de los modos de interacción del adolescente en el entorno digital. El estudio no pretende detectar manifestaciones extremas como el «cyberbullying» o la ciberagresión. Pero sí se confirma, desde el principio, que las situaciones de vulnerabilidad que acaecen tanto en la creación como en el consumo de material audiovisual por parte de los adolescentes se localizan en cuatro grandes cuadros temáticos: sexo, drogas, acoso y embarazo.

La autoría se ha demostrado como la variable con mayor poder explicativo, encontrándose los vídeos institucionales (por ejemplo, las campañas de prevención sobre el uso de las drogas o sobre la anorexia) en las antípodas de los audiovisuales elaborados por adolescentes y jóvenes. Los estudios sobre los factores potenciales de riesgo y ansiedad en los niños y adolescentes también señalan la centralidad de la empatía. Los vídeos elaborados por jóvenes en situaciones emocionales que son familiares y parecen auténticas producen la empatía más fuerte en la juventud. A la inversa, la investigación ha probado también que los vídeos institucionales no logran una gran aceptación o divulgación entre el público adolescente. YouTube es un campo mayoritariamente dominado por jóvenes con códigos jóvenes.

El estudio de contenido llevado a cabo no solo complementa las conclusiones de la investigación sobre la materia y cuantifica su posible incidencia (los vídeos de adolescentes se ven el doble y los de los «youtubers» son los de mayor impacto), sino que muestra que los gaps entre los códigos son muy profundos, lo que hace extremadamente difícil la comunicación audiovisual entre adolescentes, jóvenes y adultos. Por supuesto, el afán lúdico de las propuestas audiovisuales de los adolescentes (los géneros de coreografías, remezclas, «selfies» y «cosas divertidas» en general) contrasta con la seriedad de las propuestas audiovisuales adultas. Pero es, sobre todo, la falta de percepción de las condiciones de vulnerabilidad (quizás solo algo menos en el tema del acoso) lo que muestra que los códigos de los adultos y de los adolescentes sobre la identificación del riesgo se encuentran muy alejados: son los vídeos planteados por adolescentes los que muestran un mayor porcentaje de piezas en las que se pueden advertir menores no protegidos; son los vídeos de «youtubers» y de adolescentes los que en mayor medida se graban en sitios privados frente a lugares públicos.

En todos los temas predomina la estructura modal aséptica, declarativa; solo en el caso de los vídeos sobre acoso hay un porcentaje relevante (casi la mitad) que se dirigen a la audiencia de forma imperativa o apelan a los receptores de forma interrogativa o reflexiva. Si a esto añadimos un predominio claro de vídeos positivos o neutros, obtenemos un cuadro de falta de problematización, es decir, un escenario de normalidad. Los adolescentes «dan por supuesto» unos códigos que, en condiciones de vulnerabilidad, quizás deberían problematizarse.

En suma, la investigación de contenidos planteada muestra unos audiovisuales hechos por jóvenes para jóvenes, lúdicos, normalizados, indiferentes a las posibles situaciones de vulnerabilidad, que se presentan, quizá peligrosamente, como simples espacios de reafirmación de la adolescencia.

La crítica que puede hacerse a esta conclusión es que no sabemos en qué medida los jóvenes son capaces de decodificar en tono de inversión o de «juego» buena parte del material que puede ser detectado como «peligroso» desde el punto de vista del contenido y menos aún calcular el efecto que ese mensaje decodificado pueda producir. Desde nuestro punto de vista, futuras investigaciones deben ahondar en esta cuestión. Por ejemplo, el Modelo General de Agresión (GAM), de Anderson y Bushman (2001), permite predecir, con un gran soporte empírico, el comportamiento agresivo de los niños, aceptando que tanto las variables personales como las variables situacionales (entre ellas, la exposición a la violencia en el mundo real, en los medios o en Internet) influyen en el estado interno actual de un individuo (Kirsh, 2010; 2012). En el mismo sentido, una investigación más completa debería avanzar hacia un Modelo de Vulnerabilidad de Adolescentes y Jóvenes que contemplase, entre los riesgos a que se exponen los menores y los adolescentes, la visualización de material inapropiado. Lo que pretendemos es identificar los códigos de interacción del adolescente en el entorno digital y los contenidos susceptibles de generar potenciales vulnerabilidades, aunque la materialización de las mismas dependa de un complejo entramado de variables.

Apoyos

El presente estudio forma parte de las actividades del Programa sobre Vulnerabilidad Digital PROVULDIG (S2015/HUM3434), financiado por la Comunidad de Madrid (España) en Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades y el Fondo Social Europeo (2016-2018).

Referencias

Abisheva, A., Kiran-Garimella, V.R., García, D., & Weber, I. (2014). Who watches (and shares) what on YouTube? And when?: Using twitter to understand YouTube viewership. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, 593-602. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556195.2566588

Aguaded, I., & Sánchez, J. (2013). El empoderamiento digital de niños y jóvenes a través de la producción audiovisual. AdComunica, 5, 175-196. https://doi.org/10.6035/2174-0992.2013.5.11

Álvarez-García, D., Barreiro-Collazo, A., & Nuñez, J.C. (2017). Cyberaggression among adolescents: Prevalence and gender differences. [Ciberagresión entre adolescentes: Prevalencia y diferencias de género]. Comunicar, 50(XXV), 89-97. https://doi.org/10.3916/C50-2017-08

Anderson, C.A., & Bushman, B.J. (2001). Effects of violent video games on aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, aggressive affect, physiological arousal, and prosocial behavior: A meta-analytic review of the scientific literature. Psychological Science, 12, 353-359. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00366

Bañuelos, J. (2009). YouTube como plataforma de la sociedad del espectáculo. Razón y Palabra, 69, 1-68. (https://goo.gl/XJpyrz).

Barry, A., Johnson, E., Rabre, A., Darville, G., Donovan, K., & Efunbumi, O. (2015). Underage access to online alcohol marketing content: A YouTube case study. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 50(1), 89-94. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agu078

Berrocal, S., Campos, E., & Redondo, M. (2014). Media prosumers in political communication: Politainment on YouTube. [Prosumidores mediáticos en la comunicación política: El ‘politainment’ en YouTube]. Comunicar, 43(XXII), 65-72. https://doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-06

Blais, J., Craig, W., Pepler, D., & Connolly, J. (2008). Adolescents online: The importance of Internet activity choices to salient relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 522-536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9262-7

Bleakley, A., Ellithorpe, M., & Romer, D. (2016). The role of parents in problematic internet use among US adolescents. Media and Communication, 4(3), 24-34. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v4i3.523

Blomfield, C.J., & Barber, B.L. (2014). Social networking site use: Linked to adolescents’ social self-concept, self-esteem, and depressed mood. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66, 56-64. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12034

Chau, C. (2010). YouTube as a participatory culture. New Directions for Youth Development, 128, 65-74. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.376

De-Frutos, B., & Marcos, M. (2017). Disociación entre las experiencias negativas y la percepción de riesgo de las redes sociales en adolescentes. El Profesional de la Información, 26(1), 88-96. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.ene.09

Días-da-Silva, P., & Garcia, J.L. (2012). YouTubers as satirists: Humour and remix in online video. eJournal of eDemocracy and Open Government, 4(1), 89-114. (https://goo.gl/PHM6Ul).

Edwards, L., Kontostathis, A., & Fisher, C. (2016). Cyberbullying, race/ethnicity and mental health. Media and Communication, 4(3), 71-78. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v4i3.525

Franco, E.C. (2017). Redes sociales libres en la universidad pública. Revista Digital Universitaria, 18(1). (https://goo.gl/5ptkf1).

Fuente-Cobo, C. (2017). Públicos vulnerables y empoderamiento digital: El reto de una sociedad e-inclusiva. El Profesional de la Información 26(1), 5-12. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.ene.01

García-Jiménez, A., Catalina-García, B., & López-de-Ayala-López, M.C. (2016). Adolescents and YouTube: Creation, participation and consumption. Prisma Social, n. extra, 60-89. (https://goo.gl/qNifJN).

Halliday, M.A.K. (2004). An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Edward Arnold.

Igartua, J.J. (2006). Métodos cuantitativos de investigación en comunicación. Barcelona: Bosch.

Jenkins, J., Ford, S., & Green J. (2015). Cultura transmedia, la creación de contenido y valor en una cultura en red. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Jiménez, C., & Gaitán, B.N. (2013). Análisis de los factores que motivan a los estudiantes de la Universidad Autónoma de Occidente a difundir contenidos virales en la Red. Cali (Colombia): Universidad Autónoma de Occidente. (https://goo.gl/0jP6tH).

Karlsen, R., Borrás-Morell, J., & Traver-Salcedo, V. (2017). Are trustworthy health videos reachable on YouTube? - A study of YouTube ranking of diabetes health videos. In Proceedings of the 10th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2017) - Volume 5: Healthinf, 17-25. https://doi.org/10.5220/0006114000170025

Kirsh, S.J. (2010). Media and youth: A developmental perspective. Malden (Massachusetts): Wiley-Blackwell.

Kirsh, S.J. (2012). Children, adolescents, and media violence: A critical look at the research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lenhart, A., Smith, A., Anderson, M., Duggan, M., & Perrin, A. (2015). Teens, technology and friendships. Pew Research Center. (https://goo.gl/PHq81a).

Livingstone, S., Kirwil, L., Ponte, C., & E. Staksrud, E. (2014). In their own words: What bothers children online? European Journal of Communication, 29(3), 271-288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323114521045

López-Vidales, N., & Gómez-Rubio, L. (2015). Análisis y proyección de los contenidos audiovisuales sobre jóvenes y drogas en YouTube. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 21(2), 863-881. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_ESMP.2015.v21.n2.50889

Martínez-Pastor, E., Sendín-Gutiérrez, J.C., & García-Jiménez, A. (2013). Percepción de los riesgos en la red por los adolescentes en España: Usos problemáticos y formas de control. Análisi, 48, 111-130. (https://goo.gl/ao3odb).

McRoberts, S., Bonsignore, E., Peyton, T., & Yarosh, S. (2016). Do It for the viewers!: Audience engagement behaviors of young YouTubers. In Proceedings of the The 15th IDC International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, 334-343. https://doi.org/10.1145/2930674.2930676

Misoch, S. (2014). Card Stories on YouTube: A New Frame for Online Self-Disclosure. Media and Communication, 2(1), 2-12. (https://goo.gl/W5OsRt).

O’Keeffe, G., & Clarke-Pearson, K. (2011). The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics, 127, 800-804. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0054

Protégeles (Ed.) (2014). Menores de edad y conectividad móvil en España: Tablets y smartphones. (https://goo.gl/pBaMvV).

Ritzer, G., & Jurgenson, N. (2010). Production, Consumption, Prosumption: The nature of capitalism in the age of the digital ‘prosumer’. Journal of Consumer Culture, 10(1), 13-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540509354673

Ritzer, G., Dean, P., & Jurgenson, N. (2012). The Coming of Age of the Prosumer. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(4), 379-398. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211429368

Sabater, C. (2014). La vida privada en la sociedad digital. La exposición pública de los jóvenes en Internet. Aposta, 61, 1-32. (https://goo.gl/0HRnyI).

Subrahmanyam, K., Greenfield, P., & Michikyan, M. (2015). Comunicación electrónica y generaciones adolescentes. Infoamérica, 9, 115-130. (https://goo.gl/uvP9R7).

Syed-Abdul, S., Fernandez-Luque, L., Jian, W.S., Li, Y.C., Crain, S.,… Liou, D.M. (2013). Misleading health-related information promoted through video-based social media: Anorexia on YouTube. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(2), e30. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2237

Wartella, E., Rideout, V., Montague, H., Beaudoin-Ryan, L., & Lauricella, A. (2016). Teens, Health and Technology: A National Survey. Media and Communication, 4(3), 13-23. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v4i3.515

Yarosh, S., Bonsignore, E., McRoberts, S., & Peyton, T. (2016). YouthTube: Youth video authorship on YouTube and Vine. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 1423-1437. https://doi.org/10.1145/2818048.2819961

Document information

Published on 31/12/17

Accepted on 31/12/17

Submitted on 31/12/17

Volume 26, Issue 1, 2018

DOI: 10.3916/C54-2018-06

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?