Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Resumen

This paper analyzes the links that exist between the perceptions of teachers-in-training regarding the use of digital resources in the Secondary Education classroom and their own methodological and epistemological conceptions. Shulman’s theories continue to largely guide current research on teacher knowledge. However, the impact caused by the new technologies has inspired new approaches like T-PACK, which put the focus on the teachers’ digital competence. In order to address this goal, information has been collected by means of a questionnaire implemented in 22 universities, 13 Spanish (344 participants) and 9 British (162 participants). The analysis of data was conducted along three phases: a) examination of the structure of assessments regarding the usefulness of digital resources by analyzing latent classes; b) estimation of confirmatory factor models for variable evaluation processes, History as a formative subject and historical competencies; c) estimation of interclass differences by using confirmatory factor models. The results showed four types of response regarding the use of digital resources in the classroom that were polarized about two items: comics and video games. Important interclass differences have likewise been found regarding methodological issues (traditional and innovative practices), as well as less important differences concerning epistemological conceptions and views on the development of historical competencies in the classroom.

Resumen

El objetivo de este trabajo es analizar los vínculos entre las percepciones del profesorado en formación sobre el uso de los recursos digitales en el aula de Secundaria, y sus concepciones metodológicas y epistemológicas. Las teorías de Shulman siguen orientando en gran medida las investigaciones sobre el conocimiento del profesorado. Sin embargo, el impacto de las nuevas tecnologías ha impulsado nuevos enfoques, como el T-PACK, que incide en la competencia digital docente. Para abordar este objetivo se ha recogido información de un cuestionario implementado en 22 universidades, 13 españolas (344 participantes) y 9 inglesas (162 participantes). Los análisis de datos se realizaron en tres fases: a) exploración de la estructura de las valoraciones sobre la utilidad de los recursos digitales mediante análisis de clases latentes; b) estimación de los modelos factoriales confirmatorios para las variables procesos de evaluación, Historia como materia formativa, y competencias históricas; c) estimación de las diferencias entre clases. Los resultados mostraron cuatro perfiles de respuesta en función de la opinión sobre el uso de los recursos en el aula, y polarizadas en torno a dos ítems: cómics y videojuegos. También se ha podido comprobar importantes diferencias entre clases en cuestiones metodológicas (prácticas tradicionales e innovadoras); y diferencias menos importantes sobre percepciones epistemológicas y de desarrollo de competencias históricas en el aula.

Keywords

ICT, mass media, digital competence, secondary education, teacher education, didactic methodology, questionnaire, history

Keywords

TIC, medios, competencia digital, educación secundaria, formación docente, metodología didáctica, cuestionario, historia

Introduction and state of the question

Teacher training and pedagogical content knowledge

Over the last few decades the initial training and the continuous professional development of teachers has become a mainstream issue (González & Skultety, 2018). International studies insist on the need to renew teacher training programs in order to upgrade the teaching-learning processes in compulsory education (Barnes, Fives, & Dacey, 2017). A large number of authors argue that it is necessary to conduct more comparative research and to transfer its findings into classroom practice (König, Ligtvoet, Klemenz, & Rothlandb, 2017). In the context of current research lines in teacher training, the analysis of the knowledge and conceptions of teachers has come to play a fundamental part in the approach that should be adopted by investigations on initial training programs (Darling-Hammond, 2006; Fives & Buehl, 2012). Outstanding among this body of research are studies aimed at calibrating the several types of professional knowledge possessed by teachers and emphasizing the command of regular classroom tasks (Oliveira, Lopes & Spear-Swerling, 2019).

The proposals by Shulman (1987) have had a broad influence on the definition of such categories as are designed for the purpose of researching teachers’ knowledge. Particularly when teaching skills are evaluated, researchers tend to draw distinctions between content knowledge (CK), pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) and general pedagogical knowledge (GPK) (Kleickmann, Richter, Kunter, Elsner, Besser, Krauss, & Baumert, 2012). While CK consists in the knowledge of a specific subject and is related to the contents that teachers are expected to explain, GPK is general pedagogical knowledge and involves broad principles and strategies for classroom management and organization (Blömeke, Busse, Kaiser, König, & Sühl, 2016). PCK includes knowledge that relates the specific subject contents to the purposes of teaching (Monte-Sano, 2011): it is a kind of knowledge that delves deep into the social representations that students have with regard to a specific subject matter as well as into the way students understand that knowledge, the methods and resources that are needed in order to teach that discipline and the selection and organization of specific contents so as to adapt them to the reality of the classroom (Meschede, Fiebranz, Möller, & Steffensky, 2017).

T-PACK, teacher digital competence and didactic methodology

Digital resources are having a great impact on the new ways of classifying teacher competencies. While it is true that both teachers and students are immersed in media experiences in their everyday lives, the transfer of such an experience into the teaching-learning process has not yet been fully developed (Ramírez & González, 2016). There are still some reservations about their use that have a strong bearing on teacher training. In fact, teacher training constitutes the variable that exerts the greatest influence on the level of digital competence of teachers, according to studies like the one by González, Gozálvez and Ramírez (2015).

One of the most robust research proposals for the integration of digital resources in teacher training programs is the methodological model known as Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (T-PACK) developed by Koehler and Mishra (2008). This model supports a teacher training approach that incorporates digital resources from a threefold perspective: the teacher’s acceptance of technology and technological competence, the use of pedagogical models and the didactic application of such technologies (Koh & Divaharan, 2011). In other words, the T-PACK model is based on the interrelatedness of three types of knowledge: pedagogical content knowledge, technological content knowledge regarding how technology can be useful in generating new types of content, and technological pedagogical knowledge, which is the whole body of knowledge related to the use of technology in teaching methodologies. This model has proven relatively successful, so that in the last five years we have seen a proliferation of studies about its impact in teacher training (Gisbert, González, & Esteve, 2016), which trace the teachers’ perceptions regarding the significance of digital literacy skills (García-Martín & García-Sánchez, 2017) or measure the teachers’ ability to develop digital information among their students and promote their communicative skills in this regard (Claro & al., 2018).

Other relevant studies focus on the integration of professional digital skills into teacher training (Instefjord & Munthe, 2017) and the characterization of such factors as account for digital inclusion (Hatlevik & Christophersen, 2013) or the proposal of basic criteria for the teaching of digital skills both in schools and in teacher training programs (Engen, Giæver, & Mifsud, 2015).However, research work on the training of teachers in the domains of History and other Social Sciences that involves comprehensive, systematic and comparative studies is still scarce. There are some proposals that have produced a model in order to align evaluation with learning skills and activities (Guerrero-Roldán & Noguera, 2018). Other studies, like the one by Cózar and Sáez (2016), focus on play-based learning or gamification in the initial training of Social Science teachers; or on the digital skills of prospective Social Science teachers as defined by the TPACK model (Colomer, Sáiz & Bel, 2018). All together, they have opened up an avenue of research that needs to be further pursued.

The T-PACK model is based on the interrelatedness of three types of knowledge: pedagogical content knowledge, technological content knowledge regarding how technology can be useful in generating new types of content, and technological pedagogical knowledge, which is the whole body of knowledge related to the use of technology in teaching methodologies.

Research problems

Our main goal is to analyze the existing relationships between the views and perceptions of teachers-in-training regarding the use of digital resources and their own appraisal of History as a formative subject, as well as the didactic strategies that they are expected to implement in the classroom. This general goal, in turn, gives rise to four distinct research problems:

- Q1. What is the response profile of teachers-in-training concerning the use of digital resources in the teaching of History? Are there differences between the answers provided by Spanish and British respondents?

- Q2. What is the relationship between the opinions of teachers-in-training about the use of digital resources and their perception of evaluation processes?

- Q3. What is the relationship between the opinions of teachers-in-training about the use of digital resources and the value they attach to History as a formative subject?

- Q4. What is the relationship between the opinions of teachers-in-training about the use of digital resources and the value they attach to the development of historical skills in the classroom?

Material and methods

Participants

The context in which this research took place is the professional postgraduate degree that provides graduates with the required qualification to become Secondary Education teachers of History both in Spain and in Britain. 506 teachers-in-training were recruited all of whom were enrolled in either Spain’s Master’s degree in secondary education, History and Geography specialty (344), or Britain’s Postgraduate Certificate in Education courses or Teach First programs (162) by the end of academic year 2015-2016. 22 universities joined the study, 13 from Spain and 9 from Britain. Even though the number of British participants was lower, the sample representativeness was similar for both countries.

According to official data, and following consultation with a British expert in teacher training, its is estimated that a population of 1,200 students in Spain and 800 in Britain are enrolled in these professionally-geared degrees. The choice of these two countries is due to their different traditions in History education —in the case of Britain focused on the development of historical skills by contrast with Spain’s emphasis on conceptual contents and transversal competencies.

Research approach

The design chosen for the purpose of the present study was quantitative and non-experimental, involving the use of a Likert scale questionnaire (1-5). Survey-based designs are quite common in the field of education, since they are applicable to multiple problems and make it possible to collect information on a high number of variables (Sapsford & Jupp, 2006).

Data collection instrument

The data used are part of a questionnaire named “Views and perceptions of teachers receiving initial training on History learning and the evaluation of historical competencies”. The questionnaire was validated by four experts from different areas and universities in Spain who had extensive experience in Secondary Education. It was constructed around the pertinence and clarity of each of the items: only items scoring three on average were eventually included. The first part of the questionnaire deals with identification details and includes information about the university, gender, age and training background of respondents. The second one consists of three thematic blocks. The first block, titled “Views and perceptions about evaluation and its role in the teaching-learning process” focuses on teaching practices in relation to traditional and innovative profiles, following studies like those authored by Alonso-Tapia and Garrido (2017) or Stufflebeam and Shinkfield (2007).

The second block, “Views and perceptions about History as a formative subject, methods, sources and teaching resources” deals with the opinions of respondents with regard to the epistemology of History and its function as a subject in education. This section draws upon the Beliefs History Questionnaire used by VanSledright and Reddy (2014). The third block, “Views and perceptions about the evaluation of historical competencies in Secondary Education: use of sources, causal reasoning and historical empathy”, is mainly based on the three basic principles of historical thinking: causal explanation, sources and evidences, and empathy or historical perspective (Martínez-Hita & Gómez, 2018).

Once the questionnaire was validated by the experts, it was translated into English and submitted for further validation to the ethics committee of the University College of London’s Institute of Education, which provided its approval. For the purpose of collecting the information we previously contacted teachers in both countries. Completed questionnaires were collected in paper format from the universities of Murcia, Alicante, Valencia, Barcelona, La Rioja, Zaragoza, Oviedo, Cantabria, Valladolid, Burgos, Madrid (Universidad Autónoma), Málaga and Jaén. In Britain, questionnaires were collected, both on line and in format paper from the following universities: IoE-UCL, Exeter, Edge Hill, Metropolitan Manchester, York, Leeds, East-Anglia, Birmingham and Christ Church of Canterbury.

Procedure and data analysis

Data analysis was performed along three stages: a) Exploration of the structure of assessments on the usefulness of digital resources through latent class analysis; b) Estimation of confirmatory factor models for all three questionnaire blocks; c) Estimation of the differences across classes as regards the variables modeled under point b. All the analyses were performed by using Mplus 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2015).

Latent class analysis

In the first place, modeling was performed on the assessments provided by students regarding the importance of using the several modalities of digital resources (Internet, digital and printed press, films and documentaries on historical topics, video games and comics). To this end we used latent class analysis (LCA). LCA constitutes a useful method in order to statistically identify internally homogenous groups on the basis of continuous or categorical multivariate data. LCA uses probabilistic models for non-observable group membership unlike other clustering methods based on the detection of conglomerates by means of arbitrary or theoretical distance measurements (Hagenaars & McCutcheon, 2002). The number of classes was determined by using fit indices: entropy, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the sample-size ajusted BIC (ssaBIC) and the Lo-Mendell-Rubin test (LMR). Lower values for AIC, BIC and saaBIC suggest a better fit of the current model with respect to the more parsimonious previous one. Entropy is an index of the accuracy with which the model classifies individuals (values above .70 suggest a substantial accuracy). The LMR tests the null hypothesis that the solution with k+1 classes is no better than the solution with k classes. Significant LMR values (p<.05) suggest that the solution involving the higher number of classes represents more closely the structure of the data (Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001).

Estimation of factor models

Prior to estimating interclass differences concerning the variables under examination, confirmatory factor analyses were conducted in order to ensure measurement quality. We first assessed the dimensionality of each scale by means of an optimized parallel analysis (Timmerman & Lorenzo-Seva, 2011). Next, we estimated the confirmatory models according to the number of factors suggested by the parallel analysis.

In order to evaluate the goodness-of-fit of factor models, we estimated the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). RMSEA values lower than .05 or .08, and CFI and TLI higher than .95 and .90 respectively suggest a good or acceptable fit of the data in the model (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Additionally, we traced the presence of local misfits by using the modification indices (MI) and the standardized expected parameter change (SPEC) for each model. MI values higher than 10 and SEPC values higher than .20 suggest the presence of local sources of misfit that should be investigated before selecting the definitive model (Saris, Satorra & Van der Veld, 2009). In order to estimate all factor models, we used means and variance adjusted weighted least squares (WLSMV), given the ordinal nature of the input data.

Class comparison

Classes were compared by using the standardized factor scores obtained for each of the scales. A t-test was performed on every pair of classes. A significance level of .01 was used in order to decrease the probability of classifying as significant differences that are substantially irrelevant. For every significant contrast, we estimated the effect size (Cohen, 1988).

Results

Latent class analysis

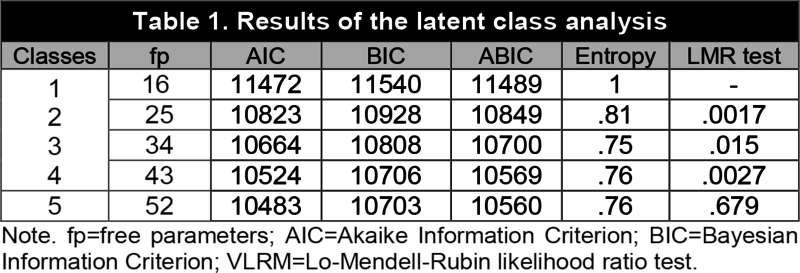

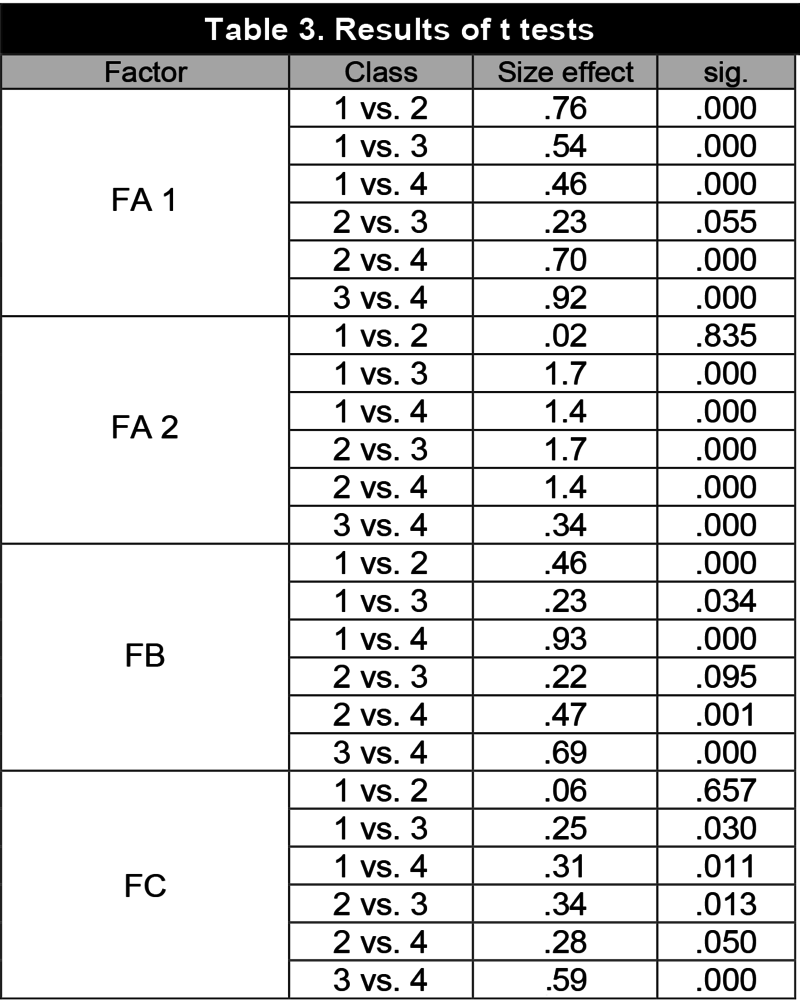

Table 1 contains the results of our latent class analysis. We estimated models of a maximum of five classes (the six-class solution could not be correctly estimated due to a non-positive definite derivative matrix). The one-class solution, equivalent to a unidimensional factor model, obtained the worst fit of all consulted indices.

|

|

AIC, BIC and saaBIC showed improved values as far as the five-class solution was concerned. However, the BIC and saaBIC improvement in the five-class model with regard to the four-class model could not be taken as strong evidence in favor of the model with more parameters (ΔBIC=3 and ΔsaaBIC=9 were in both cases lower than a Bayes factor of 150; Raftery, 1995). The LMR test suggested the inclusion of more classes until reaching the five-class model, where LMR turned out to be non-significant (p=.679), thus suggesting that the four-class model should be retained. Entropy was adequate in all cases. Given these results, we chose to retain the more parsimonious four-class solution.

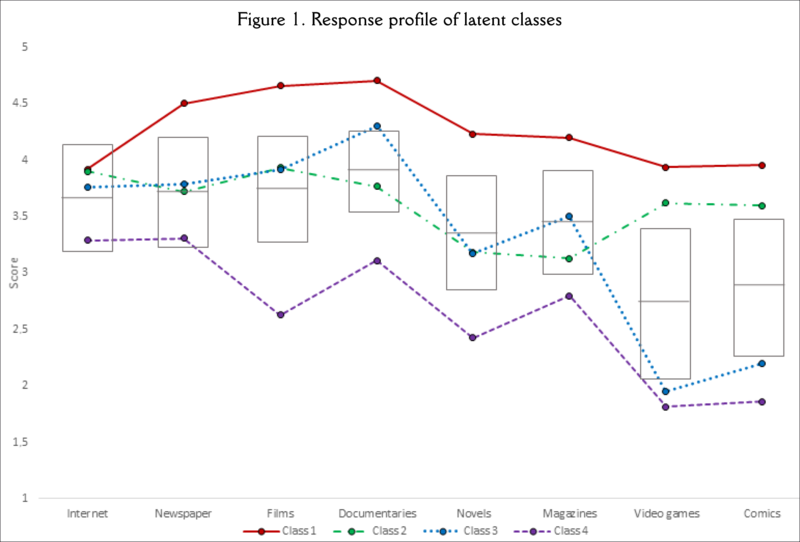

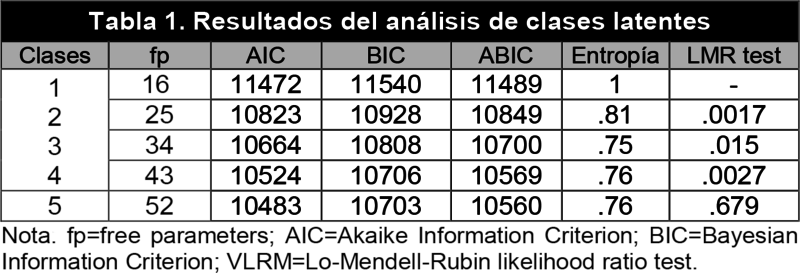

The response profile of the several classes is shown in figure 1. The lines represent the average score for each item per class (the higher the score, the more importance is attached to the items within digital resources).

|

|

The rectangles represent a standard deviation around the mean (horizontal line) estimated on the basis of the data from the full sample. Class 1 (21.2% of the sample) assigned high values to all items in digital resources. Class 2 (25.7%) assigned moderately high values to all items, with the exception of those with a larger written content (popularizing magazines and historical novels), which obtained somewhat lower values.

|

|

Class 3 (30.1%) showed a very similar profile to class 2, except for the items “documentaries”, which received slightly higher values, and “video games” and “comics”, where values were substantially low (unlike in class 2). Lastly, class 4 (22.9%) was assigned intermediate (Internet, digital and printed press, documentaries), low (film, novels and popularizing magazines) or very low values (comics and video games). The distribution of individuals across classes was significantly different in Spain and Britain (χ²(3)=28.96, p.=.001), but hardly relevant in any case (Cramer's V=.21).

Factor analysis

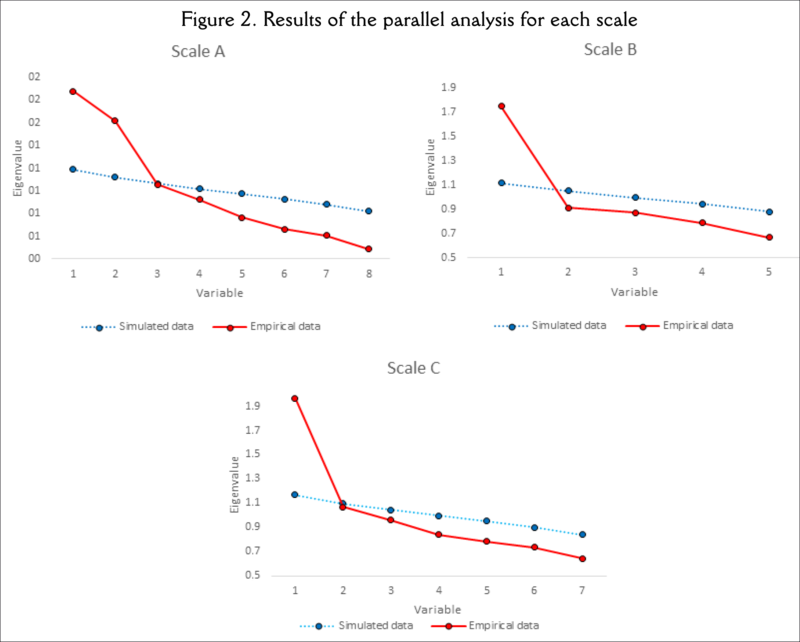

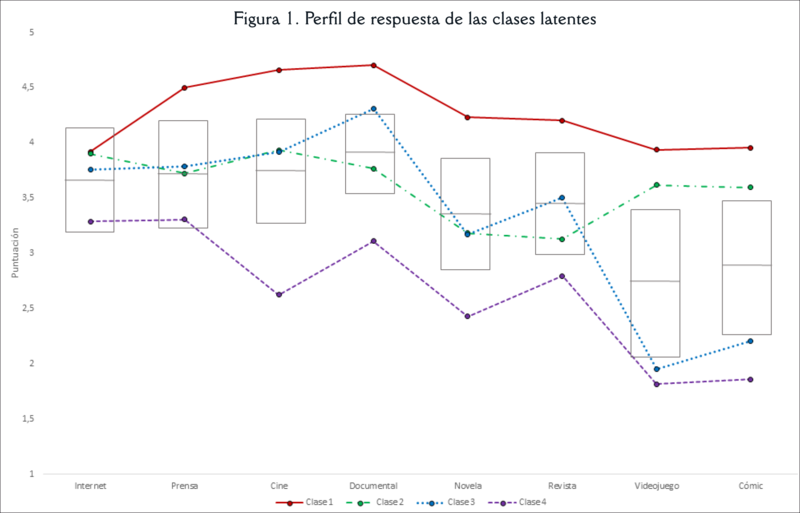

Figure 2 (panels a, b and c) shows the results of the parallel analysis for each scale. The analysis suggested a two-factor structure for scale A and a one-factor structure for scales B and C, since only one of the empirical eigenvalues was higher than the simulated eigenvalues (1,000 matrices).

Items on scale A underwent an exploratory factor analysis (weighted least squares for categorical variables implemented on FACTOR 10.9; Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2006). The two-factor correlated solution produced a clear structure where one factor clustered items referring to the preference for traditional evaluation procedures, and another one clustered those other items related to innovative evaluation procedures.

Traditional evaluation procedures clustered by factor A1 were: a) evaluation is a positive element; b) it must rely on curricular precepts; c) qualitative techniques must have a lower impact; and d) the examination is an objective procedure. The more innovative procedures clustered by factor A2 were: a) conceptual concepts must have a lower impact; b) traditional evaluation procedures hamper innovation; and c) traditional innovation procedures are related to school failure. Inter-factor correlation was negative and low (-.31), suggesting that the preference for innovative methods does not necessarily imply the rejection of traditional methods (and vice versa). Factor B clustered items related to conceptions of history as a formative subject from a traditional perspective: a) History is simply knowledge of the past; b) the disagreement among historians is only due to problems about sources; c) historical contents must be based on the origin of the nation; d) sound reading and memory skills are enough to interpret sources; e) it is complicated to use methods of inquiry. Factor C included items that were least inclined to the development and evaluation of historical skills in the classroom, save for the use of sources: a) it is essential to memorize dates; b) items supporting the use of sources; c) items against causal explanation; d) items against the use of historical empathy.

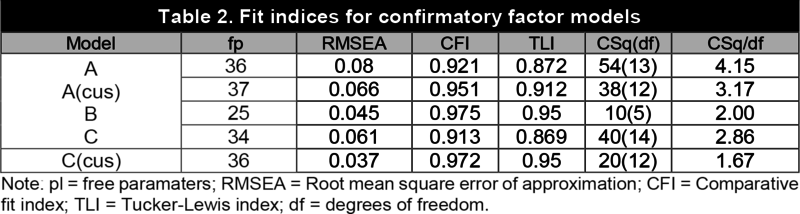

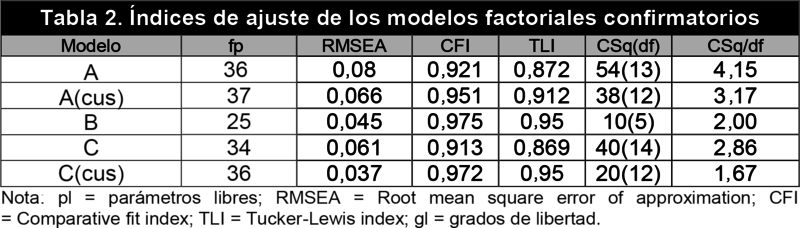

Table 2 contains the fit indices of confirmatory factor models. In the case of variable A, the two-factor correlated model achieved a sufficient goodness-of-fit according to RMSEA and CFI, but a suboptimal one according to TLI.

|

|

We can observe that the correlation between residuals for two items specifically referred to content evaluation obtained MI and SEPC values respectively higher than 10 and .20. Since it is to be expected that pairs of items referring to very specific aspects of content should exhibit moderate correlations beyond those explained by the factor itself (Brown, 2006), we chose to dispense with that correlation. The resulting model displayed a sufficient goodness-of-fit (RMSEA=.06, CFI=.951, TLI=.912). The unidimensional model for variable B obtained a close fit (RMSEA=.04, CFI=.97, TLI=.95) without further model specifications being needed. The unidimensional model for variable C obtained a sufficient goodness-of-fit on RMSEA and CFI, but not on TLI (.86). The main sources of misfit in this case were two correlations between residuals. Such specific shared variance was modelled by dispensing with both correlations, which resulted in a substantially better fit (RMSEA=.03, CFI=.97, TLI=.95).

Interclass comparison

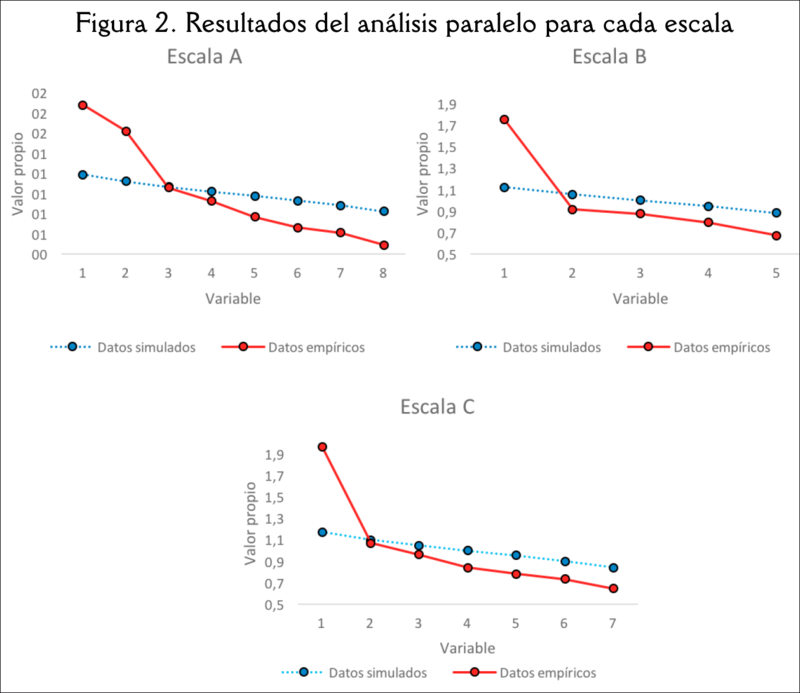

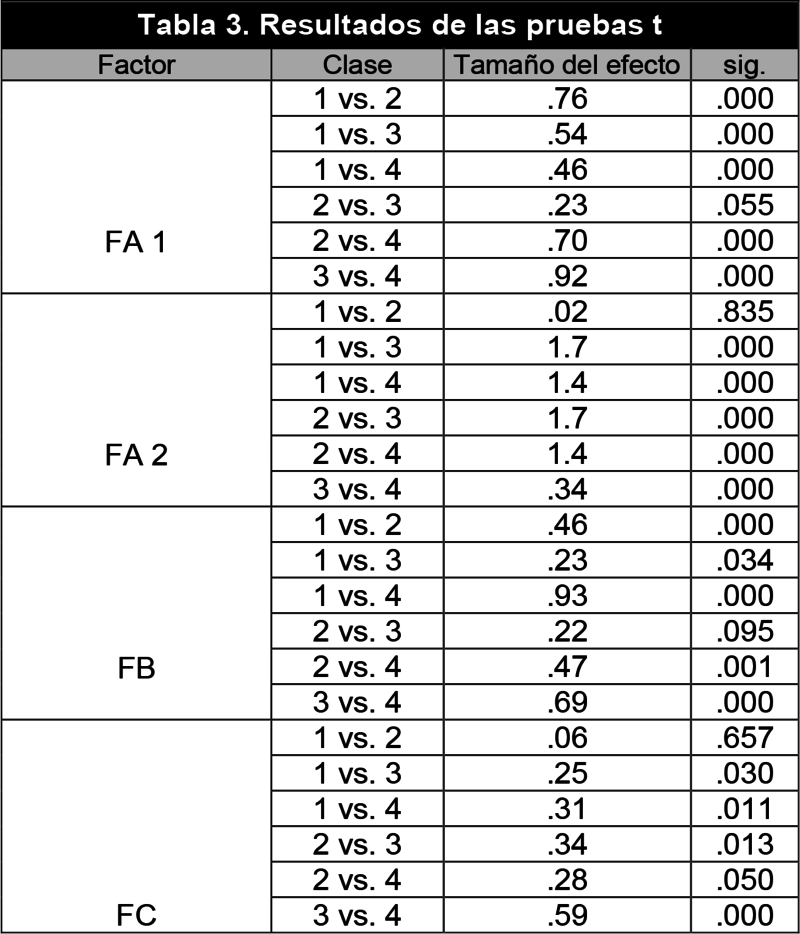

For the purpose of interclass comparison, we use the standardized factor scores (M=0, DT=1) estimated by means of the factor models described above. Table 3 contains the results of the t tests.

|

|

The main differences across classes were observed in factors A1 and A2, where ten out of twelve contrasts turned out to be significant with effect size ranging from very low (.34) to very high (1,77). Factor B showed significant differences in four out of six contrasts, with effect sizes ranging from moderate (.47) to high (.93). Finally, factor C only presented one significant difference with a moderate size effect (.59).

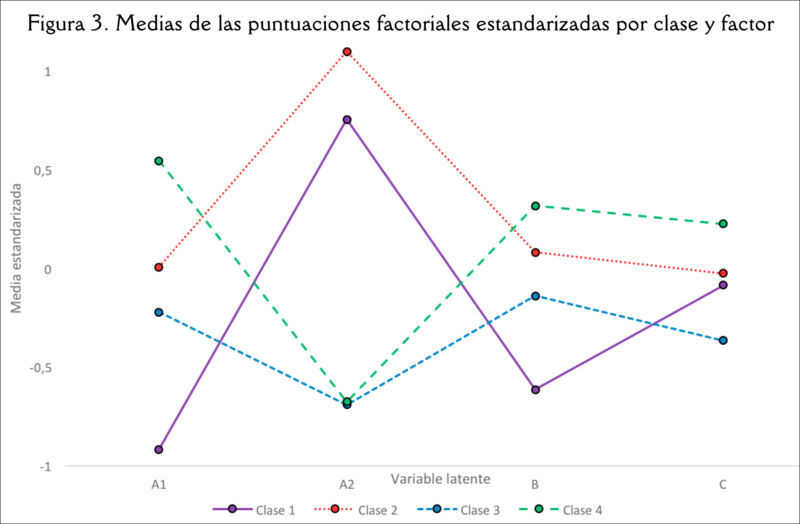

In order to facilitate the interpretation of results, figure 3 shows the mean standardized factor scores by class and factor. Regarding variable A1, class 4 showed substantially more favorable appraisals of traditional methods than the remaining classes: classes 2 and 3 showed intermediate ratings and class 1 expressed very unfavorable ones. Regarding variable A2, the most favorable views on innovative procedures were presented by classes 1 and 2, with very large differences (as many as 1.7 standard deviations) compared to classes 3 and 4, which showed moderately unfavourable assessments of innovative procedures. Regarding variable B, the main differences were observed in class 1, which produced a substantially negative appraisal of traditional perceptions of History; and in class 4, which showed moderately positive appraisals. In the case of variable C, the single relevant difference was observed between classes 3 (slightly negative appraisals) and 4 (slightly positive appraisals).

Discussion and conclusions

The results of the latent class analysis and the interclass comparison performed by using the factor model for each of the questionnaire blocks enable us to answer all four research problems.

P1. Taken as a whole, the classes reflect two issues: a) In the first six analyzed items, the classes are virtually arranged like a continuum ranging from high (class 1) to moderate ratings (classes 2 and 3), and from moderate to low (class 4); b) The previous arrangement changes in the case of comics and video games, where classes are organized around two opposite extremes resulting in a highly polarized bimodal distribution involving two substantially favourable classes (1 and 2) and two highly unfavourable ones (3 and 4). Differences in class size, on the other hand, are not very relevant, since all range between 21 and 30% of the sample. As for the differences between the results for Spain and Britain, these are scarce from a statistical point of view and basically concern the sizes of individual classes.

P2. There is no single bipolar continuum of traditional-innovative processes. The preference for innovative or traditional procedures operates as a binomial of two different and scarcely dependent factors, so that one can find individuals who prefer innovative processes without necessarily rejecting traditional ones. The traditional process factor is clearly class-related in the sense that the higher the rating assigned to the usefulness of digital resources, the lower the preference for the use of traditional procedures (this relation is clearly seen in classes 1 and 4). In the innovative process factor, groups are polarized in a similar fashion to what happened with the ratings of comics and videogames. Thus, classes 1 and 2 (positive assessments of comics and video games) are quite in favor of using innovative strategies. In comparison, classes 3 and 4 (low value attached to comics and video games) express a lower preference for innovative processes. The results show a clear correlation between the value assigned to innovative methodologies, on the one hand, and to the usefulness of comics and video games in the History classroom on the other. A clear example of this correlation can be found in class 3, which assigned very similar values to those attached by class 2 to the first six items within digital resources, while expressing a more negative assessment of comics and video games. Class 3 presents assessments of innovative procedures that are radically different from those of class 2. International studies on gamification have shown the close connection between the use of video games in the classroom and the increase in motivation and support of innovation in teacher training (Landers & Amstrong, 2017; Özdener, 2018). Although to a smaller extent, research and innovation experiences have also been published with regard to the use of comics in specific topics in the social sciences and its impact on motivation (Delgado-Algarra, 2017). Teachers-in-training see both resources as two important elements for innovation in the History classroom that are closely tied to motivation.

P3. The result for factor A1 (traditional evaluation procedures) is now repeated, but differences are much slighter in this case. In other words, the higher the ratings for the items under the digital resources category, the lower the values assigned to items presenting history as a formative subject from a traditional perspective. These results are in line with the findings in the study by García-Martín and García-Sánchez (2016), which relates the implementation of active methodologies (together with the use of innovative strategies, styles and approaches) to the acquisition and development of digital skills. In this case, again classes 1 and 4 (which express opposite views regarding the value of digital resources) represent the largest rating differences (.93). Classes 2 and 3 (representing opposite views as regards the rating of comics and video games) assign similar scores to this factor. We can observe that this polarization of classes 2 and 3 is rather related to the views on the value of innovative methodological procedures than to the open rejection of traditional methods. Moreover, since for factor B there is a mixture of methodological and epistemological elements, no differences in the views expressed by both classes (2 and 3) can be attested.

P4. There is only one difference and it qualifies as moderate. A tendency is perceived for factor B. The larger presence of items related to the discipline’s epistemology explains the fewer discrepancies across classes. In the case of factor C, the items are mainly related to the development and evaluation of historical competencies. The differences in the teachers’ ratings of the use of digital resources were mainly linked to their conception (rather traditional or innovative) of teaching methodologies. Yet such differences did not exhibit the same intensity as regards their epistemological conceptions of history: a mismatch that was already pointed at by Kirschner a decade ago (2009).

In view of the results obtained, we believe it necessary to strengthen digital competencies in teacher training programs that go beyond the mere acquaintance with ICT tools. The T-PACK model provides an alternative where the use of technology is seen from a didactic perspective targeted at teaching contents (Claro & al., 2018). If we implement this model in the training of History teachers, the use of digital resources should encourage the prospective teachers’ ability to propose activities where the historian’s procedures play a major part. Moreover, such activities should be developed on the basis of questions that enable students to solve problems by applying methods of inquiry. Research on History education over the last few decades has espoused these proposals in the face of traditional approaches and on the basis of a more competency-based epistemological view (Van-Drie & Van-Boxtel, 2008). Until these methodological perspectives are not brought together, digital resources will play a merely playful and motivational role, and will not develop a truly critical approach that instils in students the ability to evaluate digital information (Hatlevik & Hatlevik, 2018) and solve historical questions. It is necessary to adopt measures within teacher training so as to achieve a competency-based form of History education that resorts to more active learning methods (Gómez & Miralles, 2016) and foregrounds a direct relationship between the implementation of active methodologies (involving the use of innovative strategies and approaches), a shift in the epistemological model of historical knowledge and the development of digital competencies (García-Martín & García-Sánchez, 2016).

References

- Alonso-TapiaJ., GarridoH., . 2017.para el aprendizaje. Evaluación de la comprensión de textos no escritos&author=Alonso-Tapia&publication_year= Evaluar para el aprendizaje. Evaluación de la comprensión de textos no escritos.Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology 15(1):164-184

- BarnesN., FivesH., DaceyC., . 2017.teachers' conceptions of the purposes of assessment&author=Barnes&publication_year= U.S. teachers' conceptions of the purposes of assessment.Teaching and Teacher Education 65:107-116

- BlömekeS., BusseA., KaiserG., KönigJ., SühlU., . 2016.relation between content-specific and general teacher knowledge and skills&author=Blömeke&publication_year= The relation between content-specific and general teacher knowledge and skills.Teaching and Teacher Education 56:35-46

- BrownT.A., . 2006.Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Publications.

- ClaroM., SalinasA., Cabello-HuttT., San-MartínE., PreissD.D., ValenzuelaS., JaraI., . 2018.in a Digital Environment (TIDE): Defining and measuring teachers' capacity to develop students' digital information and communication skills&author=Claro&publication_year= Teaching in a Digital Environment (TIDE): Defining and measuring teachers' capacity to develop students' digital information and communication skills.Computers & Education 121:162-174

- CohenJ., . 1988.Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- ColomerJ.C., SáizJ., BelJ.C., . 2018.digital en futuros docentes de Ciencias Sociales en Educación Primaria: Análisis desde el modelo TPACK&author=Colomer&publication_year= Competencia digital en futuros docentes de Ciencias Sociales en Educación Primaria: Análisis desde el modelo TPACK.Educatio Siglo XXI 36(1):107-128

- CózarR., SáezJ.M., . 2016.learning and gamification in initial teacher training in the social sciences: An experiment with MinecraftEdu&author=Cózar&publication_year= Game-based learning and gamification in initial teacher training in the social sciences: An experiment with MinecraftEdu.International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 13(2):1-11

- Darling-HammondL., . 2006.teacher education. The usefulness of multiple measures for assessing program outcomes&author=Darling-Hammond&publication_year= Assessing teacher education. The usefulness of multiple measures for assessing program outcomes.Journal of Teacher Education 57(2):120-138

- Delgado-AlgarraE.J., . 2017.as an educational resource in the teaching of social science: Socio-historical commitment and values in Tezuka’s manga&author=Delgado-Algarra&publication_year= Comics as an educational resource in the teaching of social science: Socio-historical commitment and values in Tezuka’s manga.Culture & Education 4:848-862

- EngenB.K., GiæverT.H., MifsudL., . 2015.Guidelines and regulations for teaching digital competence in schools and teacher education: A weak link?Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 10(2)

- FivesH., BuehlM.M., . 2014.differences in practicing teachers' valuing of pedagogical knowledge based on teaching ability beliefs&author=Fives&publication_year= Exploring differences in practicing teachers' valuing of pedagogical knowledge based on teaching ability beliefs.Journal of Teacher Education 65(5):435-448

- García-MartínJ., García-SánchezJ.-N., . 2017.teachers' perceptions of the competence dimensions of digital literacy and of psychological and educational measures&author=García-Martín&publication_year= Pre-service teachers' perceptions of the competence dimensions of digital literacy and of psychological and educational measures.Computers & Education 107:54-67

- GisbertM., GonzálezJ., EsteveF., . 2016.digital y competencia digital docente: Una panorámica sobre el estado de la cuestión&author=Gisbert&publication_year= Competencia digital y competencia digital docente: Una panorámica sobre el estado de la cuestión.RIITE. Revista Interuniversitaria de Investigación en Tecnología Educativa 0:74-83

- GómezC.J., MirallesP., . 2016.skills in compulsory education: Assessment, inquiry based strategies and students’ argumentation&author=Gómez&publication_year= Historical skills in compulsory education: Assessment, inquiry based strategies and students’ argumentation.Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research 5(2):130-136

- González-FernándezN., Gozálvez-PérezV., Ramírez-GarcíaA., . 2015.competencia mediática en el profesorado no universitario. Diagnóstico y propuestas formativas&author=González-Fernández&publication_year= La competencia mediática en el profesorado no universitario. Diagnóstico y propuestas formativas.Revista de Educación 367:117-146

- GonzálezG., SkultetyL., . 2018.learning in a combined professional development intervention&author=González&publication_year= Teacher learning in a combined professional development intervention.Teaching and Teacher Education 71:341-354

- Guerrero-RoldánA.E., NogueraI., . 2018.model for aligning assessment with competences and learning activities in online courses&author=Guerrero-Roldán&publication_year= A model for aligning assessment with competences and learning activities in online courses.The Internet and Higher Education 38:36-46

- J.A.Hagenaars,, A.L.McCutcheon,, . 2002. , ed. latent class analysis&author=&publication_year= Applied latent class analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- HatlevikI.K.R., HatlevikO.E., . 2018.evaluation of digital information: The role teachers play and factors that influence variability in teacher behavior&author=Hatlevik&publication_year= Students' evaluation of digital information: The role teachers play and factors that influence variability in teacher behavior.Computers in Human Behavior 83:56-63

- HatlevikO.E., ChristophersenK.A., . 2013.competence at the beginning of upper secondary school: Identifying factors explaining digital inclusion&author=Hatlevik&publication_year= Digital competence at the beginning of upper secondary school: Identifying factors explaining digital inclusion.Computers & Education 63:240-247

- HuL.T., BentlerP.M., . 1999.criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives&author=Hu&publication_year= Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives.Structural Equation Modeling 6(1):1-55

- InstefjordE.J., MuntheE., . 2017.digitally competent teachers: A study of integration of professional digital competence in teacher education&author=Instefjord&publication_year= Educating digitally competent teachers: A study of integration of professional digital competence in teacher education.Teaching and Teacher Education 67:37-45

- KirschnerP.A., . 2009.or pedagogy, that is the question&author=Kirschner&publication_year= Epistemology or pedagogy, that is the question. In: TobiasS., DuffyT.M., eds. Instruction: Success or Failure?&author=Tobias&publication_year= Constructivist Instruction: Success or Failure?.London-New York: Routledge.

- KleickmannT., RichterD., KunterM., ElsnerJ., BesserM., KraussS., BaumertJ., . 2012.content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge: The role of structural differences in teacher education&author=Kleickmann&publication_year= Teachers´ content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge: The role of structural differences in teacher education.Journal of Teacher Education 1(17):10-1177

- KoehlerJ., MishraP., . 2008.Introducing technological pedagogical knowledge. In: AACTE, ed. handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge for educators&author=AACTE&publication_year= The handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge for educators. New York: Routledge. 3-28

- KohJ.H.L., DivaharanH., . 2011.Developing pre-service teachers' technology integration expertise through the tpack-developing instructional model.Journal of Educational Computing Research 44(1):35-58

- KönigJ., LigtvoetR., KlemenzS., RothlandbM., . 2017.of opportunities to learn in teacher preparation on future teachers’ general pedagogical knowledge: Analyzing program characteristics and outcomes&author=König&publication_year= Effects of opportunities to learn in teacher preparation on future teachers’ general pedagogical knowledge: Analyzing program characteristics and outcomes.Studies in Educational Evaluation 53:122-133

- LandersR.M., AmstrongM.B., . 2017.instructional outcomes with gamification: An empirical test of the Technology-Enhanced training effectiveness model&author=Landers&publication_year= Enhancing instructional outcomes with gamification: An empirical test of the Technology-Enhanced training effectiveness model.Computers in Human Behavior 71:499-507

- LoY., MendellN.R., RubinD.B., . 2001.the number of components in a normal mixture&author=Lo&publication_year= Testing the number of components in a normal mixture.Biometrika 88(3):767-778

- Lorenzo-SevaU., FerrandoP.J., . 2006.A computer program to fit the exploratory factor analysis model&author=Lorenzo-Seva&publication_year= Factor: A computer program to fit the exploratory factor analysis model.Behavior Research Methods 38(1):88-91

- Martínez-HitaM., GómezC.J., . 2018.cognitivo y competencias de pensamiento histórico en los libros de texto de Historia de España e Inglaterra. Un estudio comparativo&author=Martínez-Hita&publication_year= Nivel cognitivo y competencias de pensamiento histórico en los libros de texto de Historia de España e Inglaterra. Un estudio comparativo.Revista de Educación 379:145-169

- MeschedeN., FiebranzA., MöllerK., SteffenskyM., . 2017.professional vision, pedagogical content knowledge and beliefs: On its relation and differences between pre-service and in-service teacher&author=Meschede&publication_year= Teachers' professional vision, pedagogical content knowledge and beliefs: On its relation and differences between pre-service and in-service teacher.Teaching and Teacher Education 66:158-170

- Monte-SanoC., . 2011.to open up history for students: Preservice teachers' emerging pedagogical content knowledge&author=Monte-Sano&publication_year= Learning to open up history for students: Preservice teachers' emerging pedagogical content knowledge.Journal of Teacher Education 62(3):260-272

- MuthénL.K., MuthénB., . 2015. , ed. The comprehensive modelling program for applied researchers: User’s guide&author=&publication_year= Mplus. The comprehensive modelling program for applied researchers: User’s guide.Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

- OliveiraC., LopezJ., Spear-SwerlingL., . 2019.academic training for literacy instruction&author=Oliveira&publication_year= Teachers’ academic training for literacy instruction.European Journal of Teacher Education 43:315-334

- ÖzdenerN., . 2018.for enhancing Web 2.0 based educational activities: The case of pre-service grade school teachers using educational Wiki pages&author=Özdener&publication_year= Gamification for enhancing Web 2.0 based educational activities: The case of pre-service grade school teachers using educational Wiki pages.Telematics and Informatics 35:564-578

- RafteryA.E., . 1995.model selection in social research&author=Raftery&publication_year= Bayesian model selection in social research.Sociological Methodology 25:111-163

- Ramírez-GarcíaA., González-FernándezN., . 2016.competence of teachers and students of compulsory education in Spain. [Competencia mediática del profesorado y del alumnado de educación obligatoria en España&author=Ramírez-García&publication_year= Media competence of teachers and students of compulsory education in Spain. [Competencia mediática del profesorado y del alumnado de educación obligatoria en España]]Comunicar 24(49):49-58

- SapsfordR., JuppV., . 2006.Data collection and analysis. London: Sage.

- SarisW.E., SatorraA., Van-der-VeldW.M., . 2009.structural equation models or detection of misspecifications?&author=Saris&publication_year= Testing structural equation models or detection of misspecifications?Structural Equation Modeling 16(4):561-582

- ShulmanL., . 1987.and teaching: Foundations of the New Reform&author=Shulman&publication_year= Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the New Reform.Harvard Educational Review 57(1):1-23

- StufflebeamD.L., ShinkfieldA.J., . 2007.Evaluation theory, models, and applications. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- TimmermanM.E., Lorenzo-SevaU., . 2011.assessment of ordered polytomous items with parallel analysis&author=Timmerman&publication_year= Dimensionality assessment of ordered polytomous items with parallel analysis.Psychological methods 16(2):209-220

- VanSledrightB.A., ReddyK., . 2014.Epistemic Beliefs? An exploratory study of cognition among prospective history teacher&author=VanSledright&publication_year= Changing Epistemic Beliefs? An exploratory study of cognition among prospective history teacher.Tempo e Argumento 6(11):28-68

- Van-DrieJ., Van-BoxtelC., . 2008.reasoning: Towards a framework for analyzing student’s reasoning about the past&author=Van-Drie&publication_year= Historical reasoning: Towards a framework for analyzing student’s reasoning about the past.Educational Psychology Review 20:87-110

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El objetivo de este trabajo es analizar los vínculos entre las percepciones del profesorado en formación sobre el uso de los recursos digitales en el aula de Secundaria, y sus concepciones metodológicas y epistemológicas. Las teorías de Shulman siguen orientando en gran medida las investigaciones sobre el conocimiento del profesorado. Sin embargo, el impacto de las nuevas tecnologías ha impulsado nuevos enfoques, como el T-PACK, que incide en la competencia digital docente. Para abordar este objetivo se ha recogido información de un cuestionario implementado en 22 universidades, 13 españolas (344 participantes) y 9 inglesas (162 participantes). Los análisis de datos se realizaron en tres fases: a) exploración de la estructura de las valoraciones sobre la utilidad de los recursos digitales mediante análisis de clases latentes; b) estimación de los modelos factoriales confirmatorios para las variables procesos de evaluación, Historia como materia formativa, y competencias históricas; c) estimación de las diferencias entre clases. Los resultados mostraron cuatro perfiles de respuesta en función de la opinión sobre el uso de los recursos en el aula, y polarizadas en torno a dos ítems: cómics y videojuegos. También se ha podido comprobar importantes diferencias entre clases en cuestiones metodológicas (prácticas tradicionales e innovadoras); y diferencias menos importantes sobre percepciones epistemológicas y de desarrollo de competencias históricas en el aula.

ABSTRACT

This paper analyzes the links that exist between the perceptions of teachers-in-training regarding the use of digital resources in the Secondary Education classroom and their own methodological and epistemological conceptions. Shulman’s theories continue to largely guide current research on teacher knowledge. However, the impact caused by the new technologies has inspired new approaches like T-PACK, which put the focus on the teachers’ digital competence. In order to address this goal, information has been collected by means of a questionnaire implemented in 22 universities, 13 Spanish (344 participants) and 9 British (162 participants). The analysis of data was conducted along three phases: a) examination of the structure of assessments regarding the usefulness of digital resources by analyzing latent classes; b) estimation of confirmatory factor models for variable evaluation processes, History as a formative subject and historical competencies; c) estimation of interclass differences by using confirmatory factor models. The results showed four types of response regarding the use of digital resources in the classroom that were polarized about two items: comics and video games. Important interclass differences have likewise been found regarding methodological issues (traditional and innovative practices), as well as less important differences concerning epistemological conceptions and views on the development of historical competencies in the classroom.

Keywords

TIC, medios, competencia digital, educación secundaria, formación docente, metodología didáctica, cuestionario, historia

Keywords

ICT, mass media, digital competence, secondary education, teacher education, didactic methodology, questionnaire, history

Introducción y estado de la cuestión

Formación del profesorado y conocimiento didáctico del contenido

En los últimos decenios la formación inicial y continua del profesorado se ha convertido en un tema axial (González & Skultety, 2018). Los estudios internacionales insisten en la necesidad de renovar los programas de capacitación docente para mejorar los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje en educación obligatoria (Barnes, Fives, & Dacey, 2017). Gran parte de los autores señalan que es necesaria una mayor investigación comparativa y transferir estos hallazgos a la práctica docente en el aula (König, Ligtvoet, Klemenz, & Rothlandb, 2017). En el marco de las líneas de investigación sobre la capacitación del profesorado, el análisis de los conocimientos y concepciones de estos docentes ha tomado un protagonismo fundamental para orientar los programas de formación inicial (Darling-Hammond, 2006; Fives & Buehl, 2012). En estos trabajos destacan las investigaciones que pretenden calibrar los diferentes tipos de conocimiento profesional del docente, haciendo hincapié en el dominio de las tareas habituales del aula (Oliveira, Lopes, & Spear-Swerling, 2019). Las propuestas de Shulman (1987) han influido ampliamente en la definición de las categorías diseñadas para la investigación del conocimiento del profesorado. Especialmente cuando se evalúan las competencias docentes, los investigadores tienden a distinguir entre conocimiento de contenido (CK), conocimiento didáctico del contenido (PCK) y conocimiento pedagógico general (GPK) (Kleickmann & al., 2012).

Mientras que CK es el conocimiento de la asignatura específica y está relacionado con el contenido que el profesorado debe enseñar; el GPK es el conocimiento pedagógico general, que implica amplios principios y estrategias de gestión y organización del aula (Blömeke, Busse, Kaiser, König, & Sühl, 2016).

El PCK incluye un conocimiento que relaciona la temática concreta de la materia con las finalidades de la enseñanza (Monte-Sano, 2011); un conocimiento que profundiza en las representaciones sociales que el alumnado tiene de una materia en concreto, en cómo el alumnado comprende esos conocimientos, en los métodos y recursos necesarios para enseñar esa disciplina, así como en la selección y organización de los contenidos concretos para adecuarlos a la realidad del aula (Meschede, Fiebranz, Möller, & Steffensky, 2017).

T-PACK, competencia digital docente y metodología didáctica

Los recursos digitales y los medios de comunicación están teniendo un gran impacto en las nuevas formas de clasificar las competencias docentes. Aunque el profesorado y el alumnado viven inmersos en experiencias mediáticas, la transferencia al proceso de enseñanza y aprendizaje no se ha realizado de forma plena (Ramírez & González, 2016). Existen todavía reservas sobre su uso muy relacionadas con la formación docente. Esta formación es la variable que más incide en el nivel de competencia digital de profesorado según estudios como los de González, Gozálvez y Ramírez (2015).

Una de las propuestas de integración de los recursos digitales que más fuerza está teniendo en las investigaciones sobre formación del profesorado es el modelo metodológico Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (T-PACK), desarrollado por Koehler y Mishra (2008). Este modelo apuesta por una formación del profesorado que integre las TIC desde una triple perspectiva: la aceptación y competencia técnica de los docentes; la modelización pedagógica y la aplicación didáctica de estas tecnologías (Koh & Divaharan, 2011). Así, el modelo T-PACK se basa en la interrelación de tres tipos de conocimiento: Pedagogical Content Knowledge, conocimiento didáctico del contenido; Technological Content Knowledge, sobre cómo la tecnología puede ser útil para generar nuevas formas de contenido; y Technological Pedagogical Knowledge, que hace referencia al conjunto de saberes relacionados con el uso de las tecnologías en la metodología docente.

Este modelo ha tenido relativo éxito, y en los últimos cinco años se han multiplicado los estudios sobre su incidencia en la capacitación docente (Gisbert, González, & Esteve, 2016), identificando las percepciones de los profesores sobre las dimensiones de la competencia en alfabetización digital (García-Martín & García-Sánchez, 2017) o midiendo la capacidad de los docentes para desarrollar la información digital de los alumnos y sus habilidades comunicativas (Claro & al., 2018).

Otros estudios relevantes se han centrado en la integración de la competencia digital profesional en la formación docente (Instefjord & Munthe, 2017) caracterizando los factores que explican la inclusión digital (Hatlevik & Christophersen, 2013) o aportando criterios básicos para la enseñanza de la competencia digital en las escuelas y en la formación docente (Engen, Giæver, & Mifsud, 2015). Sin embargo, todavía son escasas las investigaciones sobre la formación del profesorado de Historia y otras Ciencias Sociales a través de estudios amplios y sistemáticos que permitan la comparación. Algunas propuestas han generado un modelo para alinear la evaluación con las competencias y actividades de aprendizaje (Guerrero-Roldán & Noguera, 2018). Trabajos como los de Cózar y Sáez (2016), centrado en el aprendizaje basado en juegos y gamificación en la formación inicial del profesorado en ciencias sociales, o el de Colomer, Sáiz y Bel (2018) sobre la competencia digital en futuros docentes de Ciencias Sociales desde el modelo TPACK, han abierto un camino sobre el que es necesario profundizar.

El modelo T-PACK se basa en la interrelación de tres tipos de conocimiento: Pedagogical Content Knowledge, conocimiento didáctico del contenido; Technological Content Knowledge, sobre cómo la tecnología puede ser útil para generar nuevas formas de contenido; y Technological Pedagogical Knowledge, que hace referencia al conjunto de saberes relacionados con el uso de las tecnologías en la metodología docente.

Problemas de investigación

El principal objetivo es analizar las relaciones existentes entre la opinión y percepción que tiene el profesorado en formación sobre el uso de los recursos digitales con la valoración que estos docentes realizan de la historia como materia formativa, y las estrategias didácticas que deben implementar en el aula.

Este objetivo ha dado lugar a cuatro problemas de investigación:

- P1. ¿Qué perfil de respuesta tiene el profesorado en formación sobre los recursos digitales y los medios para la enseñanza de la historia? ¿Existen diferencias entre las respuestas de los participantes en España e Inglaterra?

- P2. ¿Qué relación existe entre la opinión del profesorado en formación sobre el uso de los recursos digitales y su percepción sobre los procesos de evaluación?

- P3. ¿Qué relación existe entre la opinión del profesorado en formación sobre el uso de las TIC y los medios y su valoración de la historia como materia formativa?

- P4. ¿Qué relación existe entre la opinión del profesorado en formación sobre el uso de los recursos digitales y su valoración del desarrollo de competencias históricas en el aula?

Material y métodos

Participantes

El contexto en el que se realiza la investigación es el posgrado habilitante para ser profesor de Secundaria de la materia de Historia en España y en Inglaterra. Intervinieron 506 docentes en formación que cursaban el Máster de Educación Secundaria, especialidad de Geografía e Historia, en España (344), y el Postgraduate Certificate in Education y el Teach First en Inglaterra (162), al finalizar el curso académico 2015-2016. Participaron 22 universidades, 13 españolas y 9 inglesas. A pesar de que el número de participantes ingleses es menor, la representatividad de la muestra es similar. Según datos oficiales y las consultas realizadas a un experto de Inglaterra sobre la formación del profesorado, se estima una población de 1.200 estudiantes en España y 800 en Inglaterra en estos posgrados habilitantes. La elección de estos dos países se debe a su diferente tradición en educación histórica: centrada en competencias históricas en el caso de Inglaterra, y arraigada a contenidos conceptuales y competencias transversales en España.

Enfoque de la investigación

Para este estudio el diseño escogido fue cuantitativo no experimental a través de un cuestionario con escala Likert (1-5). Los diseños mediante encuesta son muy habituales en el ámbito de la educación ya que son aplicables a múltiples problemas y permiten recoger información sobre un elevado número de variables (Sapsford & Jupp, 2006).

Instrumento de recogida de la información

Los datos utilizados forman parte de un cuestionario denominado «Opinión y percepción del profesorado en formación inicial sobre el aprendizaje de la historia y la evaluación de competencias históricas». El cuestionario fue validado por cuatro expertos de diferentes áreas y universidades españolas, con amplia experiencia en Educación Secundaria. Se estructuró en torno a la pertinencia y claridad de cada uno de los ítems. Se dejaron solo los ítems que superaron tres de media.

El cuestionario tiene una primera parte de identificación con información sobre universidad, sexo, edad y formación. La segunda consta de tres bloques temáticos. En el primero, titulado «Opinión y percepción sobre la evaluación y su papel en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje», se han tenido en cuenta las prácticas docentes relacionadas con perfiles tradicionales e innovadores, según estudios como los de Alonso-Tapia y Garrido (2017) o Stufflebeam y Shinkfield (2007). El segundo bloque, «Opinión y percepción sobre la historia como materia formativa, métodos, fuentes y recursos de enseñanza», se centra en las percepciones de los encuestados sobre la epistemología de la historia y su función como materia educativa. Esta parte se ha basado en el Beliefs History Questionaire, empleado por VanSledright y Reddy (2014). El tercero, «Opinión y percepción sobre la evaluación de competencias históricas en Secundaria: utilización de fuentes, razonamiento causal y empatía histórica», se ha basado principalmente en tres de los principales conceptos de pensamiento histórico: explicación causal, fuentes y pruebas, y empatía o perspectiva histórica (Martínez-Hita & Gómez, 2018). Tras realizar la validación del cuestionario por los expertos, fue traducido al inglés y se sometió a la validación del comité de ética del Institute of Education (University College of London), que fue positiva.

Para la recogida de información se contactó previamente con el profesorado de ambos países. Se recopilaron cuestionarios en papel de las universidades de Murcia, Alicante, Valencia, Barcelona, La Rioja, Zaragoza, Oviedo, Santander, Valladolid, Burgos, Autónoma de Madrid, Málaga y Jaén. En Inglaterra se reunieron cuestionarios en papel y on line: IoE-UCL, Exeter, Edge Hill, Metropolitan Manchester, York, Leeds, East-Anglia, Birmingham y Christ Church of Canterbury.

Procedimiento y análisis de datos

Los análisis de datos se realizaron en tres fases: a) exploración de la estructura de las valoraciones sobre la utilidad de los recursos digitales mediante análisis de clases latentes; b) estimación de los modelos factoriales confirmatorios para los tres bloques del cuestionario; c) estimación de las diferencias entre clases en las variables modeladas en el punto b. Todos los análisis se realizaron con Mplus 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2015).

Análisis de clases latentes

En primer lugar, se modelaron las valoraciones dadas por los estudiantes de la importancia del uso de diversas modalidades de los recursos digitales (Internet, prensa digital y en papel, películas y documentales de temática histórica, novela histórica, revistas de divulgación, videojuegos y cómics). Empleamos análisis de clases latentes (LCA). El LCA es un método útil para identificar estadísticamente grupos internamente homogéneos a partir de datos multivariados continuos o categóricos. El LCA utiliza modelos probabilísticos de pertenencia a subgrupos no observables, a diferencia de otros métodos de agrupamiento basados en la detección de conglomerados mediante medidas de distancia arbitrarias o teóricas (Hagenaars & McCutcheon, 2002).

El número de clases se determinó a partir de los índices de ajuste: entropía, el Criterio de Información de Akaike (AIC), el Criterio de Información Bayesiana (BIC), el BIC ajustado al tamaño de la muestra (ssaBIC) y el test de Lo-Mendell-Rubin (LMR). Valores menores de AIC, BIC y saaBIC sugieren mejor ajuste del modelo actual respecto del modelo anterior más parsimonioso. La entropía es un indicador de la precisión con que el modelo clasifica a los individuos en las clases (valores superiores a .70 sugieren bastante precisión). El LMR pone a prueba la hipótesis nula de que la solución con k+1 clases no es mejor que la solución con k clases. Valores significativos de LMR (p<.05) sugieren que la solución con más clases representa mejor la estructura de los datos (Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001).

Estimación de los modelos factoriales

Antes de estimar las diferencias entre clases respecto a las variables de estudio, se realizaron análisis factoriales confirmatorios para garantizar la calidad de la medida. En primer lugar, analizamos la dimensionalidad de cada escala mediante análisis paralelo optimizado (Timmerman & Lorenzo-Seva, 2011). Después, estimamos los modelos confirmatorios con el número de factores sugerido por el análisis paralelo. Para evaluar el ajuste de los modelos factoriales, evaluamos el «root mean square error of approximation» (RMSEA), el «comparative fit index» (CFI) y el «Tucker-Lewis index» (TLI). Valores RMSEA inferiores a .05 o a .08, y valores CFI y TLI superiores a .95 y .90 sugieren un ajuste bueno o aceptable de los datos al modelo, respectivamente (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Adicionalmente investigamos la presencia de fuentes de desajuste local mediante la inspección de los índices de modificación (MI) y los parámetros estandarizados de cambio (SEPC) de cada modelo. Valores MI mayores a 10 y SEPC mayores a .20 sugieren la presencia de fuentes de desajuste que debieran ser investigadas antes de la selección del modelo definitivo (Saris, Satorra & Van-der-Veld, 2009). Para la estimación de todos los modelos factoriales utilizamos mínimos cuadrados ponderados con media y varianza ajustada (WLSMV) dada la naturaleza ordinal de los datos de entrada.

Comparación de clases

Las clases se compararon utilizando las puntuaciones factoriales estandarizadas obtenidas en cada una de las escalas, mediante una prueba t para cada par de clases. Se empleó un nivel de significación de .01 para disminuir la probabilidad de clasificar como significativas diferencias substantivamente irrelevantes. Para cada contraste significativo tuvimos en cuenta el tamaño del efecto (Cohen, 1988).

Resultados

Análisis de clases latentes

La Tabla 1 contiene los resultados del análisis de clases latentes. Valoramos modelos de hasta cinco clases (la solución de seis no se pudo estimar correctamente debido a una matriz derivativa de primer orden no definida positivamente). La solución de una clase, equivalente a un modelo factorial unidimensional, obtuvo el peor ajuste en todos los índices consultados. AIC, BIC y saaBIC mejoraron hasta la solución de cinco clases. Sin embargo, la mejora de BIC y saaBIC en el modelo de cinco clases respecto del de cuatro no pudo interpretarse como evidencia fuerte a favor del modelo con más parámetros (ΔBIC=3 y ΔsaaBIC=9, en ambos casos menor a un factor Bayes de 150; Raftery, 1995). El test LMR sugirió la inclusión de más clases hasta el modelo de cinco, donde LMR resultó no significativo (p=.679), sugiriendo la retención del modelo de cuatro clases. La entropía resultó adecuada en todos los casos. Dados estos resultados, optamos por conservar la solución más parsimoniosa de cuatro clases.

|

|

El perfil de respuesta de las clases se muestra en la Figura 1. Las líneas representan la puntuación media en cada ítem por clase (mayor puntuación corresponde a mayor importancia atribuida a los ítems de los recursos digitales). Los rectángulos representan una desviación típica en torno a la media (línea horizontal) calculada a partir de los datos de toda la muestra. La clase 1 (21,2% de la muestra) asignó valoraciones altas a todos los ítems de las TIC. La clase 2 (25,7%) asignó valores moderadamente altos a todos los ítems, excepto aquellos con mayor carga escrita (revistas de divulgación y novela histórica), con valoraciones algo menores. La clase 3 (30,1%) mostró un perfil muy similar a la clase 2, excepto en el ítem «documentales» donde asignaron valores ligeramente más altos, y en los ítems «videojuegos» y «cómics», donde las valoraciones fueron sustancialmente bajas (al contrario que en la clase 2).

Por último, la clase 4 (22,9%) otorgó valores medios (Internet, prensa digital y escrita, documentales), bajos (cine, novelas y revistas de divulgación) o muy bajos (cómics y videojuegos). Las distribución de personas en las clases fue significativamente distinta entre España e Inglaterra (χ²(3)=28,96, p.=.001), pero de escasa relevancia (v de Cramer=.21).

|

|

Análisis factorial

La Figura 2 (paneles a, b y c) muestra los resultados del análisis paralelo para cada escala. El análisis sugirió una estructura de dos factores para la escala A, y de un factor para las escalas B y C, toda vez que solo uno de los valores propios empíricos superó los valores propios simulados (1.000 matrices). Los ítems de la escala A se sometieron a un análisis factorial exploratorio (mínimos cuadrados ponderados para variables categóricas implementado en FACTOR 10,9; Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2006). La solución de dos factores correlacionados produjo una estructura clara, donde un factor agrupó a los ítems referidos a la preferencia por procedimientos de evaluación tradicionales, y otro factor a los referidos a procedimientos de evaluación innovadores.

Los procedimientos tradicionales de evaluación que agrupó el factor A1 fueron: a) la evaluación es un elemento positivo; b) debe basarse en preceptos curriculares; c) las técnicas cualitativas deben tener un menor peso; y d) el examen es objetivo. Los procedimientos más innovadores que agrupó el factor A2 fueron: a) los contenidos conceptuales deben tener un menor peso; b) los procedimientos tradicionales de evaluación impiden la innovación; y c) los procedimientos tradicionales de evaluación están relacionados con el fracaso escolar.

La correlación entre factores fue negativa y baja (-.31), sugiriendo que la preferencia por métodos innovadores no implica necesariamente el rechazo de métodos tradicionales (y viceversa). El factor B agrupó a los ítems de concepciones de la historia como materia formativa desde una perspectiva tradicional: a) la historia es simplemente el conocimiento del pasado; b) el desacuerdo entre historiadores es solo por problemas con las fuentes; c) los contenidos históricos deben basarse en el origen de la nación; d) las buenas habilidades de lectura y memorización son suficientes para interpretar fuentes; e) es complicado usar métodos de indagación.

El factor C estuvo compuesto por los ítems menos proclives al desarrollo y evaluación de competencias históricas en el aula, excepto en el uso de fuentes: a) es fundamental memorizar fechas; b) ítems a favor del uso fuentes; c) ítems en contra de la explicación causal; d) ítems en contra del uso de la empatía histórica.

|

|

La Tabla 2 contiene los índices de ajuste de los modelos factoriales confirmatorios. En el caso de la variable A, el modelo de dos factores correlacionados obtuvo un ajuste suficiente según RMSEA y CFI, pero subóptimo según el TLI. Observamos que la correlación entre los residuales de dos ítems referidos específicamente a la evaluación de contenidos tuvo MI y SEPC superiores a .10 y .20, respectivamente.

Ya que es esperable que pares de ítems referidos a aspectos muy concretos del contenido presenten correlaciones moderadas más allá de las explicadas por el factor (Brown, 2006), optamos por liberar la correlación. El modelo resultante presentó un ajuste suficiente (RMSEA=.06, CFI=.951, TLI=.912). El modelo unidimensional de la variable B obtuvo un ajuste bueno (RMSEA=.04, CFI=.97, TLI=.95) sin necesidad de ulteriores re-especificaciones del modelo.

El modelo unidimensional de la variable C obtuvo un ajuste suficiente en RMSEA y CFI pero no en TLI (.86). Las responsables principales del desajuste fueron dos correlaciones entre residuales. Dicha varianza específica compartida se modeló liberando ambas correlaciones, lo que dio lugar a una mejora sustancial en el ajuste (RMSEA=.03, CFI=.97, TLI=.95).

|

|

Comparación de clases

Para la comparación de clases empleamos las puntuaciones factoriales estandarizadas (M=0, DT=1) estimadas mediante los modelos factoriales arriba descritos.

La Tabla 3 contiene los resultados de las pruebas t. Las principales diferencias entre clases se observaron en los factores A1 y A2, donde diez de doce contrastes resultaron significativos, con tamaños de efecto desde bajos (.34) a muy altos (1,77).

|

|

El factor B registró diferencias significativas en cuatro de seis contrastes, con tamaños de efecto entre moderados (.47) y altos (.93). Por último, el factor C solo registró una diferencia significativa, con un tamaño de efecto moderado (.59). Para facilitar la lectura de resultados, la Figura 3 muestra las medias de las puntuaciones factoriales estandarizadas por clase y factor.

Respecto a la variable A1, la clase 4 mostró valoraciones sustancialmente más favorables a los métodos tradicionales que el resto de clases: las clases 2 y 3 mostraron valoraciones medias, y la clase 1 muy desfavorables. Respecto la variable A2, las opiniones más favorables hacia los procedimientos innovadores fueron registradas por las clases 1 y 2, con diferencias muy grandes (hasta 1,7 desviaciones típicas) respecto de las 3 y 4, que manifestaron valoraciones moderadamente desfavorables hacia procedimientos innovadores. Respecto a la variable B, las principales diferencias se observaron en la clase 1, que valoró de forma sustancialmente negativa las percepciones tradicionales de la historia; y la clase 4, que mostró valoraciones moderadamente positivas. En el caso de la variable C, la única diferencia relevante se observó entre la clase 3 (valoraciones ligeramente negativas) y la 4 (valoraciones ligeramente positivas).

|

|

Discusión y conclusiones

Con los resultados obtenidos del análisis de clases latentes y la comparación de clases con el modelo factorial de cada uno de los bloques del cuestionario, podemos responder a los cuatro problemas de investigación.

P1. Tomadas en conjunto las clases reflejan dos cuestiones: a) en los primeros seis ítems analizados, las clases se disponen prácticamente como un continuo, desde valoraciones elevadas (clase 1), a moderadas (clases 2 y 3), y de moderadas a bajas (clase 4); b) el orden anterior se rompe en el caso de los cómics y videojuegos, de manera que las clases se organizan en dos extremos opuestos, produciendo una distribución bimodal muy polarizada, con dos clases bastante favorables (1 y 2) y dos muy contrarias (3 y 4). La diferencia de tamaño entre clases no es muy relevante, pues todas oscilan entre el 21-30% de la muestra. La diferencia entre los resultados de España e Inglaterra es escasa a nivel estadístico, y recae principalmente en el tamaño de cada una de las clases.

P2. No existe un continuo único bipolar de procesos tradicionales-innovadores. La preferencia por procesos innovadores o tradicionales funciona como un binomio de dos factores distintos y poco dependientes, de forma que pueden observarse personas que prefieren procesos innovadores, pero no por eso rechazan procesos tradicionales. En el factor de procesos tradicionales hay una relación clara con las clases, de modo que cuanto más elevada es la valoración de la utilidad de las TIC, menos preferencia hay por el uso de procedimientos tradicionales (esta relación se ve especialmente en las clases 1 y 4). En el factor de procesos innovadores los grupos se polarizan de forma similar a como se polarizaban en la valoración de cómics y videojuegos. Así, las clases 1 y 2 (valoraciones positivas de los cómics y videojuegos) están bastante a favor del uso de estrategias innovadoras. Comparativamente, las 3 y 4 (valoración pobre de cómics y videojuegos) manifiestan mucha menor preferencia por procesos innovadores. Los resultados muestran que existe una clara correlación entre la valoración de los procesos metodológicos innovadores y la valoración de la utilidad de cómics y videojuegos en el aula de Historia. Un ejemplo claro es la clase 3, que valoró de forma muy similar a la 2 los primeros seis ítems de los recursos digitales, y de una forma más negativa los cómics y videojuegos. Esta clase presenta valoraciones de los procedimientos de innovación radicalmente distintos a los de la clase 2. Estudios internacionales sobre gamificación han mostrado la estrecha relación entre el uso de videojuegos en el aula con el incremento de la motivación y el impulso de la innovación en la formación del profesorado (Landers & Amstrong, 2017; Özdener, 2018). Aunque más minoritarias, también se han publicado experiencias de investigación e innovación sobre el uso de los cómics en temas específicos de ciencias sociales y su impacto en la motivación (Delgado-Algarra, 2017). El profesorado en formación asume estos dos recursos como dos elementos importantes para la innovación en el aula de Historia, muy ligados a la motivación.

P3. Se repite el resultado del factor A1 (procedimientos tradicionales de evaluación) pero con diferencias mucho más moderadas. Esto es, a mayor valoración de los ítems de TIC, corresponde menor estimación de los ítems que exponen la historia como materia formativa desde una perspectiva tradicional. Estos resultados se sitúan en la línea del estudio de García-Martín y García-Sánchez (2016), que pone en relación la implementación de metodologías activas (así como el uso de estrategias estilos y enfoques innovadores) con la adquisición y el desarrollo de competencias digitales. En este caso, de nuevo las clases 1 y 4 (opuestas en cuanto a valoración de las TIC) son las que presentan mayor diferencia de valoración (,93). Las clases 2 y 3 (opuestas en cuanto a la valoración de cómics y videojuegos) otorgan una puntuación muy similar en este factor. Podemos comprobar que esa polarización de las clases 2 y 3 está más relacionada con la opinión sobre la valoración de procedimientos metodológicos innovadores que con el rechazo a los métodos tradiciones. Además, como en el factor B se mezclan elementos metodológicos con epistemológicos no hay diferencia de opinión entre estas dos clases (2 y 3).

P4. Hay una sola diferencia y es moderada. Se percibe la tendencia del factor B. La mayor presencia de ítems relacionados con la epistemología de la disciplina provoca que las discrepancias entre clases sean menores. En el caso del factor C, los ítems están relacionados principalmente con el desarrollo y evaluación de competencias históricas. Las diferencias de valoración que el profesorado realizó sobre el uso de las TIC estuvieron ligadas principalmente a su concepción más tradicional o innovadora de la metodología didáctica. Pero estas diferencias no tuvieron la misma intensidad en relación con sus concepciones epistemológicas de la historia. Una falta de conexión que ya apuntó hace una década Kirschner (2009).

A tenor de los resultados obtenidos, creemos que es necesario reforzar en los programas de formación del profesorado unas competencias digitales docentes que lleguen más allá del simple conocimiento de las herramientas TIC. El modelo T-PACK nos ofrece una alternativa que plantea el uso de la tecnología desde una perspectiva didáctica y orientada al contenido propio a enseñar (Claro & al., 2018). Si aplicamos este modelo en la formación del profesorado de Historia, el planteamiento de recursos digitales debe utilizarse para incentivar en los futuros docentes la capacidad de proponer actividades en las que los procedimientos del historiador tengan un importante protagonismo. Pero, además, estas actividades deben partir de interrogantes que permitan al alumnado resolver problemas a través de métodos de indagación. Las investigaciones sobre educación histórica en las últimas décadas han defendido estas propuestas frente al enfoque tradicional, partiendo desde una visión epistemológica de la historia más competencial (Van-Drie & Van-Boxtel, 2008). Si no se aúnan estas perspectivas metodológicas y epistemológicas, los recursos digitales tendrán solo una función lúdica y motivacional, y no un abordaje crítico que desarrolle en el alumnado la capacidad de evaluar información digital (Hatlevik & Hatlevik, 2018) y resolver interrogantes históricos. Es necesaria una intervención en la formación del profesorado que permita conseguir una educación histórica basada en competencias y desde métodos activos de aprendizaje (Gómez & Miralles, 2016), mostrando así la relación directa entre la implementación de metodologías activas (así como el uso de estrategias y enfoques innovadores), un cambio en el modelo epistemológico del saber histórico, y el desarrollo de competencias digitales (García-Martín & García-Sánchez, 2016).

References

- Alonso-TapiaJ., GarridoH., . 2017.para el aprendizaje. Evaluación de la comprensión de textos no escritos&author=Alonso-Tapia&publication_year= Evaluar para el aprendizaje. Evaluación de la comprensión de textos no escritos.Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology 15(1):164-184

- BarnesN., FivesH., DaceyC., . 2017.teachers' conceptions of the purposes of assessment&author=Barnes&publication_year= U.S. teachers' conceptions of the purposes of assessment.Teaching and Teacher Education 65:107-116

- BlömekeS., BusseA., KaiserG., KönigJ., SühlU., . 2016.relation between content-specific and general teacher knowledge and skills&author=Blömeke&publication_year= The relation between content-specific and general teacher knowledge and skills.Teaching and Teacher Education 56:35-46