Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Understanding the factors that predict excessive use of social networks in adolescence can help prevent problems as addictive behaviours, loneliness or cyberbullying. The main aim was to ascertain the psychological and social profile of adolescents whose use of SNSS is excessive. Participants comprised 1,102 adolescents aged between 11 and 18 from Girona (Spain). Those who made excessive use of social networks were grouped together. Their personality and social profiles were explored, the former using NEO FFI, NEO PI-R and Self-Concept AF5, and the latter through the use of Social Support Appraisals, self-attributed type of ICT use in the family and rules regarding ICT use at home. The prevalence of excessive use was 12.8%, being higher among girls. The personality profile was characterized by neuroticism, impulsivity and a lower family, academic and emotional self-concept. The social profile was defined by the perception of high ICT consump¬tion in the mother and siblings, and a lack of rules. The protective factors were conscientiousness, the existence of rules, and being a boy; risk factors were the use of SNSS as a distraction and for fun, and the perception of high sibling consumption. Interventions based on gender and working on responsible ICT use within the family environment are proposed to prevent more serious psychological problems.

1. Introduction

Children and adolescents’ increased use of and constant presence on social networks has been highlighted by a number of global organizations and researchers (Livingstone, Haddon, Görzig, & Ólafsson, 2011; International Telecommunication Union, 2017). This continuous use of technology may lead to “excessive use”, something recognized as a public health concern (World Health Organization, 2014) and it can be associated with serious psychological and interpersonal relationship problems as addiction (Ho, Lwing, & Lee, 2017), loneliness (Ndasauka & al., 2016) or cyberbullying (Casas, Del Rio, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2013).This study will use the term “excessive use” of social networks (Buckner, Castille, & Sheets, 2012), understanding this to be when the number of hours of use affects adolescents leading a normal daily life (Castellana, Sánchez-Carbonell, Graner, & Beranuy, 2007; Viñas, 2009), but not only in terms of the time invested in this use but also in the impact that it causes in personal and social areas of adolescent life (Smahel & al., 2012).

In southern European countries, excessive Internet use ranges from 3% to 24% (Olafsson, Livingstone, & Haddon, 2014), with similar percentages reported in the United States (Weinstein & Lejoyeux, 2010). In Spain, 21.3% of adolescents are at risk of developing addictive Internet behaviour due to abusive use of social networks (Fundación Mapfre, 2014). Some studies pointed out gender differences in social network excessive use (Müller & al., 2017): intensive use is related to girls whereas an addictive use is related to boys among intensive users (3.6% of girls vs. a 4.1% of boys). Nevertheless, results on gender differences are not consistent in the literature. In this sense, Salehan and Negabahn (2013) didn’t find gender differences between the use of mobile social networking applications and mobile addiction; in opposite to previous research that suggests that women are more susceptible to develop addictive behaviour.

The heavy presence of adolescents in social networks allows them to express and develop their personality and their characteristics. Moreover, the social nature of networks implies a wide range of interactions and relationships among adolescents and the others as peers, relatives, or strangers. For this reason, the present research is conducted on their psychological profile, as well as personality, social, and context factors, to determine the impact of excessive use of social networks on adolescents. While some studies show the importance of analyzing these aspects together (Marino & al., 2016), studies that explore them separately are more common.

Research linked certain personality traits to the social networks use, and the majority of them are based on Costa and McCrae’s (1992) Big Five Theory. In this regard, it has been observed that high scores in neuroticism (Amichai-Hamburger & Vinitzky, 2010; Marino & al., 2016; Tang, Chen, Yang, Chung, & Lee, 2016) and low scores in extraversion (Ross, Orr, Sisic, Arseneault, & Simmering, 2009) are linked to problematic or addictive use. There is a negative correlation between the use of networks such as Facebook or Twitter and the facets of openness to experience and conscientiousness (Hughes, Rowe, Batey, & Lee, 2012; Schou & al., 2013), which act as protective factors. Some studies show that high scores in agreeability are linked to problematic use (Kuss, Van-Rooij, Shorter, Griffiths, & Van-de-Mheen, 2013), while others conclude that they are an indicator of a lower risk of developing addiction (Meerkerk, Van-den-Eijnden, Vermulst, & Garrestsen, 2009). Finally, our aim was also to analyze the relationship between impulsiveness and excessive use of social networks, since some studies note that this seems to be the strongest predictor of problematic use (Billieux, Gay, Rochat, & Van-der-Linden, 2010; Billieux, Van-der Linden, & Rochat, 2008).

Adolescents seek acceptance or social validation through social networks, and this affects their well-being and self-esteem (Jackson, von Eye, Fitzgerald, Zhao, & Witt, 2010; Pérez, Rumoroso, & Brenes, 2009; Valkenburg, Peter, & Schouten, 2006). Low self-esteem is linked to the more frequent use of social networks (Aydin & Volkan, 2011), and symptoms of addiction (Bahrainian, Haji-Alizadeh, Raeisoon, Hashemi-Gorji, & Khazaee, 2014).

The Internet and social networks allow adolescents to connect with their friends, create and strengthen interpersonal relationships, support others and receive social support, and cultivate emotional ties (Best, Manktelow, & Taylor, 2014; Frison & Eggermont, 2015; Livingstone, 2008; Reich, Subrahmanyam, & Spinoza, 2012; Tang & al., 2016).

The family may provide an environment that protects against excessive use of technology as long as this social context is perceived to be a facilitator of social support (Echeburúa, 2012). Research shows that parents use a range of mediation strategies to regulate the use their children make of the Internet (Durager & Livingstone, 2012; Livingstone & Helsper, 2008), among them restrictions or rules of use (OfCom, 2016; Garmendia, Jiménez, Casado, & Mascheroni, 2016).

Another factor related to adolescents’ use of technology is the real or perceived use of their parents (Hiniker, Shoenebeck, & Kientz, 2016; Lauricella, Wartella, & Rideout, 2015; Livingstone, Haddon, Görzig, & Ólafsson, 2011). In those European countries where parents use the Internet on a daily basis, their children use it more frequently; the reverse is also true (Livingstone & al., 2011). These data would seem to indicate that the relationship between parental and children’s use not only means that they spend more time using technology together, but also that there is an individualized increase in the time they spend separately on their devices (Lauricella & al., 2015). As Boyd points out (2014: 85): “A gap in perspective –about the adolescents’ opportunities to gather with friends– exists because teens and parents have different ideas of what social life should look like”.

The primary aim of this cross-sectional study is to determine the psychological and social profile of adolescents aged between 11 and 18 who make excessive use of social networks. It explicitly sets out to:

Describe the socio-demographic profile and prevalence of use among the group of adolescents identified as excessive users versus that of the normative group.

Explore which personality and social context variables constitute the profile of such consumers.

Assess which variables best predict excessive use of social networks in the age group researched.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

The multi-stage cluster sampling technique was used to choose a random sample (n=1,218) from a total population of 5,365 secondary, baccalaureate, and professional training students in the Alt Empordà region (Girona, Spain). The final sample was comprised of 1,102 students (90.5% participation) from 6 educational centres, most of which are state-run (91.6%). 48.1% of participants were boys whose ages ranged from 11 to 18 (M=14.42; SD=1.78). At the time of the research, the students were attending the 4th year of secondary education (n=793) (equivalent to year 10 in the UK education system); the 1st and 2nd years of the university entry level course or baccalaureate (n=278) (equivalent to a two-year ‘A’ level course); or professional training cycles (n=31).

2.2. Instruments

• Scales to determine excessive social networks use:

– A Self-attributed scale of social networks use (Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram, Snapchat) (Casas & al., 2007). A single-item scale which asks subjects what kind of social networks consumer they consider themselves to be based on 5 possible answers (1=I never or hardly ever use it; 2=I’m a low consumer; 3=I’m an average consumer; 4=I’m a fairly high consumer; 5=I’m a very high consumer).

– The media and technology usage and attitudes scale (MTUA) (Rosen, Whaling, Carrier, Cheever, & Rokkum, 2013). 60 items are grouped into 15 sub-scales assessing the frequency of use and attitudes towards ICT (1=Never and 10=Continually). The sub-scale “social networks Activities” (a= .89) was used for those who indicated they had a Facebook profile (Instagram was added as it is currently one of the networks most used by adolescents).

• Scales to determine personality:

– NEO Five Factor Inventory (Costa & Mc Rae, 1992, 2004): a reduced version of NEO PI-R, allowing the assessment of five personality traits and consisting of 60 items (0=Totally disagree and 4=Totally agree). Cronbach alphas for each scale are: neuroticism, .64; extraversion, .61; openness to experience, .62; agreeableness, .53; and conscientiousness, .69. The impulsiveness facet items of the NEO PI-R (Costa & Mc Rae, 2008) were added, showing an internal consistency of .74.

– AF5 self-concept by García and Musitu (1999). The Catalan-adapted version was applied (Malo & al., 2014), consisting of 30 items contemplating the five self-concept dimensions suggested by the original authors (0=Never and 10=Always). The psychometric properties of this scale are excellent and similar to those of the original scale: internal consistency ranges vary between .75 (social) and .91 (academic).

• Scales to determine social context:

– Social Support Appraisals (SSA) (Vaux & al., 1986). This study used 14 of the 23 original items, seven referring to the family and seven to friendships (0=Not at all and 10=Very clearly). The internal consistency of the friends’ dimension of SSA is .91, and that of family .92.

– Self-attributed scale for family ICT use. A single-item scale adapted from Casas et al. (2007), in which subjects classified the kind of consumer their parents and siblings were.

– Rules on ICT use at home (adapted version of Hiniker & al., 2017). A dichotomous question (Yes/No) was created to determine whether there were any set rules at home regarding the use of ICT (mobile, computer, tablet, etc.).

– Items from the scale perceptions regarding social networks use (a scale created ad hoc). 19 items were designed to explore how and what adolescents feel when using social networks. The question was as follows: Below you will find a group of phrases regarding things you may feel when using social networks such as Facebook, Twitter or WhatsApp. Please indicate how far you agree with each of them. When I use social networks… The scale ranged from 0 (I completely disagree) to 10 (I completely agree). The Cronbach Alpha for this study was .92.

2.3. Procedure

Permission was requested from the Government of Catalonia’s Department of Education and the respective school boards and parents associations, who were also informed of the research aims. All head teachers and students were guaranteed data confidentiality and anonymity. The questionnaire was divided into two parts to make it less tiring for participants and administered in two one-hour sessions during the 2016-2017 academic year. Two researchers were present to answer questions or doubts.

2.4. Data analysis

To meet the general aim, two groups of social network use were created: one for excessive use and a normative group. To this end, participants who had answered “5” (I’m a very high consumer) in the social networks consumption self-concept questionnaire, and those who had answered “10” (Continually) in three or more of the items of the MTUA “social network activity” sub-scale, were grouped. A value of “0” was given to the normative group and “1” to that of excessive use. For the first specific aim, the prevalence of participants who formed part of this group was calculated in comparison to the normative group; chi-squared tests were used to compare the results by gender and age. For the second, the t-test was used to analyze both the psychological and social profiles of the group with excessive use, and chi-squared tests were also used to analyze the social profile. For the final aim, a forward stepwise binary logistic regression was carried out to ascertain the variables that are predictors of excessive use. The dependent variable was the categorical variable of the “use group”, where “0” was given to the normative group and “1” to the group making excessive use of social networks. The covariables were the personality dimensions (NEOFFI, NEOPIR, and AF5 self-concept), social variables (social support, perceived use by father, mother and siblings, the presence or not of rules, and the group of variables from the ad hoc scale on perceptions regarding use of social networks), and gender.

All analyses were carried out using the SPSS, version 23.0 statistical package. The minimum level of statistical significance required in all tests was p<.05.

3. Analysis and results

a) Socio-demographic profile and prevalence of excessive social networks use group and normative group. The prevalence of boys (n=34) and girls (n=78) who form part of the group making excessive use of social networks is 12.8%; the percentage of girls (69.4%) is significantly higher (?2=16.743; p<.001) than that of boys. No differences were observed regarding age.

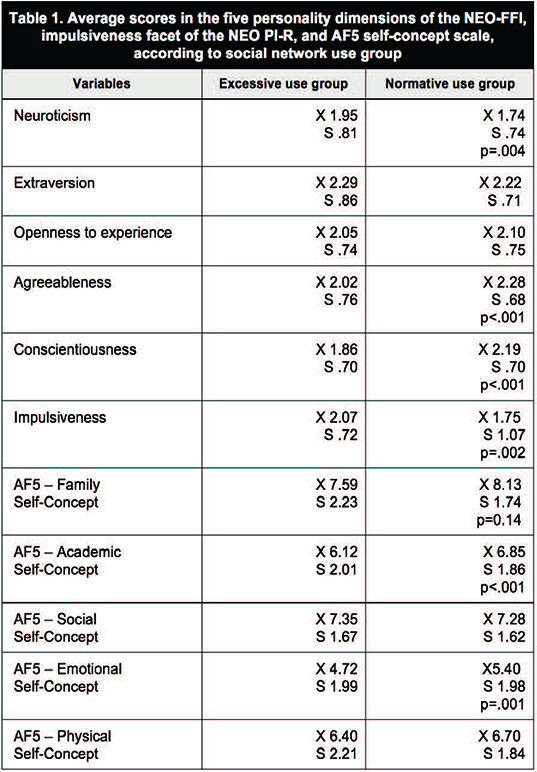

b) Personality profile of excessive social networks use group and normative group. Those participants classified in the group with excessive use show significantly higher scores than the normative group concerning neuroticism and impulsiveness, while this difference was observed in the scores for agreeableness and conscientiousness for the normative group. Those adolescents with excessive use show significantly lower scores in the family, academic and emotional self-concept than the other users (Table 1).

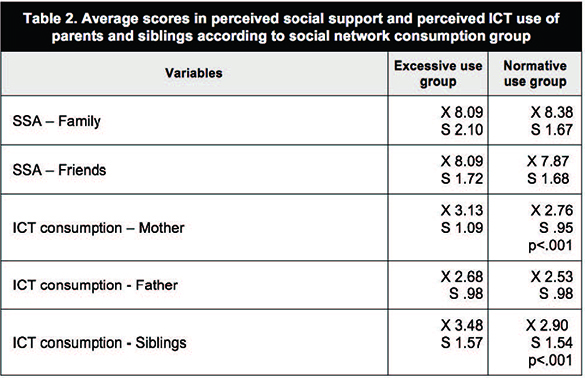

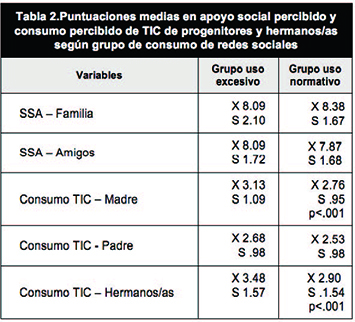

c) The social profile of excessive social networks use group and normative group. There are no significant differences in the perception of social support from friends and family among groups; however, significant differences were noted in the perception of ICT consumption by parents and siblings: those adolescents who make excessive use of social networks attribute a higher consumption to their mothers and siblings than those in the normative group (Table 2).

59.5% of participants said there were no rules regulating ICT use at home. The groups show significant statistical differences (?2(4) =8.390; p=.004): 72.1% of the excessive use group stated there were no rules (57.6% in the normative group), and 42.2% of the normative group said there were (27.9% of the excessive use group).

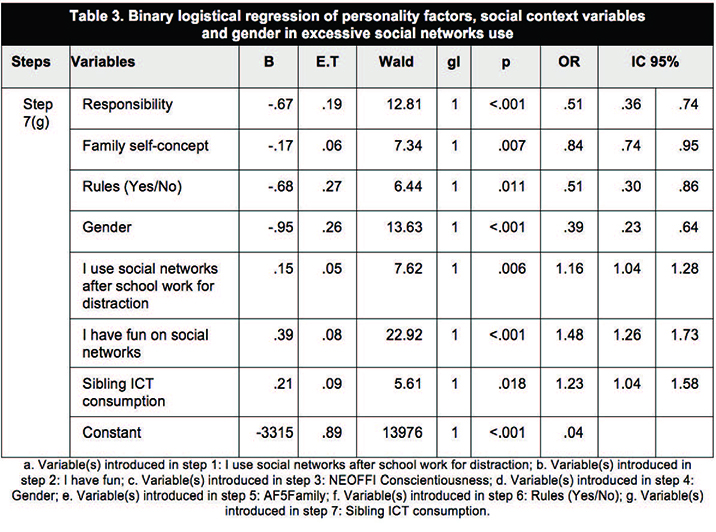

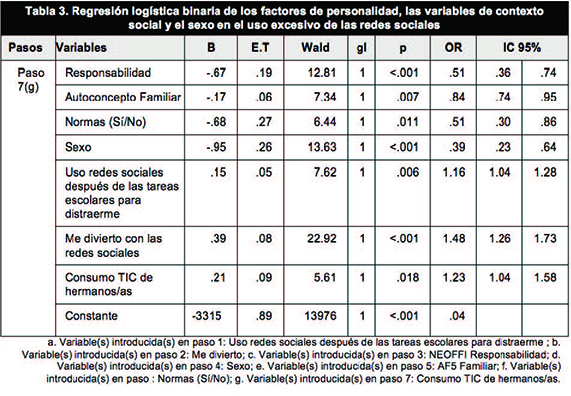

d) Variables predicting excessive and normative use of social networks. The model correctly classified 86.3% of participants. The Nagelkerke R2 indicates that the model explains 27.2% of the variability. The protective factors against excessive social networks use are the dimension of conscientiousness (OR=.512; IC 95%= .355-.739), family self-concept (OR=.841; IC 95%= .742 -.953), the existence of rules regulating ICT use at home (OR=.508; IC 95% =.301-.857) and being a boy (OR=.387; IC 95%=.234-.641); while the risk factors are related to the use of social networks as a distraction after schoolwork (OR=1.157; IC 95%=1.043-1.283), for fun (OR=1.475; IC 95%=1.258-1.729), and the perception of sibling ICT use (OR=1.229; IC 95%=1.036-1.458) (Table 3).

4. Discussion and conclusions

The primary aim of this paper was to describe the psychosocial profile of a sample of Spanish adolescents aged between 11 and 18 who make excessive use of social networks. The data used to construct this profile were based on results deriving from the Five Factor Model, self-concept, the contextual variables of social support from friends and family, and the perception of the family’s ICT consumption. Specifically, we found a greater prevalence of girls than boys in the excessive use group (Müller & al., 2017); and, while age does not seem to be a discriminating element, it was observed that it is at 13 (21.4%) and 16 (18.8%), the periods where there is most intense use of these technologies (Caldevilla, 2010). The prevalence of excessive use in this study (12.8%) was moderate, and in the intermediate band of values detected in previous studies (Olafsson & al., 2014; Weinstein & Lejoyeux, 2010).

Secondly, the results of this study support data from previous research identifying differentiated personality characteristics between the group making excessive use of social networks and the normative group, the former presenting the traits of neuroticism and impulsiveness, which confirmed their link to addictive and problematic behaviors. Some adolescents with high scores in neuroticism use Facebook as much to regulate their mood (Marino & al., 2016; Tang & al., 2016) as to experience the feeling of belonging to a group and satisfy their need to feel confident (Amichai-Hamburger & Vinitzky, 2010). Furthermore, the tendency to act hastily in response to intense emotional situations, such as social networks use, is an indicator of problematic use (Billieux & al., 2010; Billieux & al., 2008). The normative use group was characterized by higher agreeableness and conscientiousness, both factors being related to a lower risk of developing addictive behaviors (Meerkerk & al., 2009; Schou & al., 2013). However, these results should be interpreted with caution due to the low rates of internal consistency observed in some of the scales.

Self-esteem was another construct that presents differences between groups: the excessive use group showed a lower self-assessment of how they were perceived by their family, the academic world –by teachers, classmates and themselves– and the level of understanding of their own emotions and how these were shown to others (García & Musitu, 1999). Maintaining good levels of self-esteem and self-concept, above all in some of these dimensions, acts as a protective factor against ICT addictions (Echeburúa, 2012). An example is to be found in Pérez et al. (2009), who observed that those adolescents who make a varied and intense use of their free-time, and a low use of entertainment media and new media such as the Internet, show a more positive academic self-assessment than those whose free-time is less rich and diverse and who make greater use of entertainment and new media.

Regarding the contextual variables, no differences were found between the groups in perceived social support from either friends or family. Previous research does, however, show that giving and receiving social support online may be a motivation to make more intensive use of social networks (Tang & al., 2016). Nonetheless, the role played by the perception of the family’s ICT consumption appeared as a differentiating factor in the formation of one type of social networks consumer or other (Hiniker & al., 2016). Our results support the idea that those adolescents who form part of the group of excessive users perceived that their mothers and siblings also made intensive use of such technologies, functioning as models of consumption (Livingstone & al., 2011). As previous studies have noted, this aspect seems not only to affect how the family uses ICT, but also individualized use by children (Lauricella & al., 2015). In the current context, in which multiple devices are frequently used by all members of the family, including the youngest (Holloway, Green, & Livingstone, 2013), parents and relatives play an essential role in the vicarious learning of responsible ICT use. Our study revealed that half of the sample said there are no rules governing ICT use at home, confirming that education should not merely be limited to rule-regulated use (OfCom, 2016; Garmendia & al., 2016). This percentage was even higher (72.1%) in the group that made excessive use. Durager and Livingstone (2012) suggest that one of the most effective strategies for regulating responsible use, increasing opportunities and preventing risks, is active mediation, talking actively or sharing online activities with children. Contrarily, setting rules, restrictions, or technical mediation strategies (such as parental filters) is linked to lower online risk. However, this can lead to children becoming less free to explore, learn and develop resilience; thus taking less advantage of digital opportunities and abilities.

The present study is not exempt from limitations. The sample, while representative of a region and age range, does not permit extrapolation to other population groups. The data have been compiled through self-assessment surveys, which do not guarantee reliability or validity, as some subjects may have responded based on social desirability. Since this is a cross-sectional study, we cannot determine causative relationships. Future longitudinal cohort research would provide a sounder profile of excessive social network use, as well as protective and risk variables. Taking into account the percentage of explained variance, further variables that have not been dealt with in this study should be examined, such as social context and personality, as these may be related to the studied profile.

Despite these limitations, our study allows us to support previous findings because we found: a) gender differences between excessive and normative user, but not according to age, b) similar prevalence of Spanish adolescents’ excessive use than European and American countries, c) impulsiveness and neuroticism as a main personality variables related to excessive use, and d) although we didn’t find differences in perceived social support between groups of consumers, the group of excessive users perceived significantly more ICT family consume (mother and siblings). Furthermore, our data showed that the excessive use of social networks was negatively predicted by gender, responsibility, to have rules at home, and family self-concept; and was positively predicted by the perception of siblings ICT use, the use of social networks to have fun and to use them after school for distraction. According to these predictive variables we observed two adolescents’ profiles: (a) Being a girl, using social networks as a distraction and for fun, and perceiving a high ICT use by siblings, as a risk profile; (b) Being a boy, with a high score in conscientiousness, high academic self-concept and having ICT-use rules at home as a protective one. It should be noted that the percentage of variance explained by the regression model is rather low and, consequently, it can be considered that there are other variables not included in this study that can predict excessive use.

These discoveries lead us to a number of conclusions: 1) Being part of the group of excessive users implies greater time using social networks and it may lead to a potential risk, affecting adolescents’ everyday life; in this regard, recent studies point out that the intensive use of social networks in adolescence is related to Internet addiction and psychosocial distress. (Müller & al., 2017) 2) The profile of this group of users is comprised of the combination of personality traits and the closest social context in which they learn to use ICT, revealing the need for further studies that explore both variables, on the one hand, and on the other hand, the need to create: a) specific youth interventions to regulate the traits of personality directly associated with excessive use –as impulsivity– with training programs in full conscientiousness (Mindfulness) (Franco, de la Fuente, & Salvador, 2011), and b) to develop social policies to promote a more responsible use in family context. (Gómez, Harris, Barreiro, Isorna, & Rial, 2017). Finally, 3) As we have seen in previous studies (Müller & al., 2017) due to being a girl is a factor of risk for excessive use, the gender variable should be taken into account when developing specific intervention proposals to prevent problematic ICT behaviours.

Overall, the results of this study can be a first step for the construction of new measures of excessive use of social networks to assess the facets of the personality of adolescents, as well as to more deeply analyze the context of family use in which children and teenagers are socialized. Following the ecological model of Bronfenbrenner (Bronfenbrenner & Evans, 2000) we could explore other contexts of socialization such as school life or leisure and free time (see chapter 3 of Boyd, 2014), and even explore what social values are involved in the excessive ICT use (for example, hedonism, security, or individualism). All these new variables would allow us to have a wider view of the complexity of this psychosocial reality.

Funding Agency

The authors belong to the ERIDIQV, Research Team on Children, Adolescents, Children’s Rights and their Quality of Life (www.udg.edu/eridiqv) from the University of Girona, recognized as a Consolidated Research Group by Autonomous Government of Catalonia (2014-SGR-1332 and 2017 SGR 162), obtaining funding to collect data for this study.

References

Amichai-Hamburger, Y., & Vinitzky, G. (2010). Social network use and personality. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 1289-1295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.018

Aydin, B., & Volkan, S. (2011). Internet addiction among adolescents: the role of self-steem. Procedia and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 3500-3505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.325

Bahrainian, S., Haji-Alizadeh, K., Raeisoon, M., Hashemi-Gorji, O., & Khazaee, A. (2014). Relationship of Internet addiction with self-esteem and depression in university students. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, 55(3), 86-89.

Best, P., Manktelow, R., & Taylor, B. (2014). Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Children and Youth Services, 41, 27-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.001

Billieux, J., Gay, P., Rochat, L., & Van-der-Linden, M. (2010). The role of urgency and its underlying psychological mechanisms in problematic behaviours. Behaviour Research and Therapy 48(11), 1085-1096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.07.008

Billieux, J., Van-der-Linden, M., & Rochat, L. (2008). The role of impulsivity in actual and problematic use of the mobile phone. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 22, 1195-1210. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1429

Boyd, D. (2014). It’scomplicated. The social lives of networked teens. Yale University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Evans, G.W. (2000). Developmental science in the 21st century: Emerging theoretical models, research designs, and empirical findings. Social Development, 9, 115-125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00114

Buckner, J.E., Castille, C.M., & Sheets, T.L. (2012). The five factor model of personality and employees’ excessive use of technology. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1947-1953. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.05.014

Caldevilla, D. (2010). Las Redes Sociales. Tipología, uso y consumo de las redes 2.0 en la sociedad digital actual. Documentación de las Ciencias de la Información, 33, 45-68.

Casas, F., Madorell, L., Figuer, C., González, M., Malo, S., García, M. ... Babot, N. (2007). Preferències i expectatives dels adolescents relatives a la televisió a Catalunya. Barcelona: Consell Audiovisual de Catalunya.

Casas, J.A., Del-Rio, R., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2013). Bullying and cyberbullying: Convergent and divergent predictor variables. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 580-587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.015

Castellana, M., Sánchez-Carbonell, X., Graner, C., & Beranuy, M. (2007). El adolescente ante las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación: Internet, móvil y videojuegos. Papeles del Psicólogo, 28(3), 196-204.

Costa, P.T., & Mc-Crae, R.R. (2008). NEO PI-R Inventario de Personalidad NEO Revisado Manual. Madrid, TEA.

Costa, P.T., & McCrae, R.R. (1992). The revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO-five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Costa, P.T., & McCrae, R.R. (2004). A contemplated revision of the NEO Five-Factor Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 587-596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00118-1

Durager, A., & Livingstone, S. (2012). How can parents support children’s Internet safety? London: EU Kids Online. https://goo.gl/Bh3Lw1

Echeburúa, E. (2012). Factores de riesgo y factores de protección en la adicción a las nuevas tecnologías y Redes Sociales en jóvenes y adolescentes. Revista Española de Drogodependencias, 4, 435-448.

Franco, C., de la Fuente, M., & Salvador, M. (2011). Impacto de un programa de entrenamiento en consciencia plena (mindfulness) en las medidas de crecimiento y la autorrealización personal. Psicothema, 23(1), 58-65.

Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2015). Exploring the relationships between different types of Facebook use, perceived online social Support, and adolescents’ depressed mood. Social Science Computer Review, 34(2), 153-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314567449.

Fundación Mapfre (Ed.) (2014). Tecnoadicción. Más de 70.000 adolescentes son tecnoadictos. Seguridad y Medioambiente, 1, 66-69.

García, F., & Musitu, G. (1999). Autoconcepto forma 5. AF5. Manual. Madrid: TEA.

Garmendia, M., Jiménez, E., Casado, M., & Mascheroni, G. (2016). Riesgos y oportunidades en Internet y uso de dispositivos móviles entre menores españoles (2010-2015). Net children and go mobile. Final Report March 2016. https://goo.gl/aFSxsB

Gómez, P., Harris, S.K., Barreiro, C., Isorna, M., & Rial, A. (2017). Profiles of Internet use and parental involvement, and rates of online risks and problematic Internet use among Spanish adolescents. Computer in Human Behaviour, 75, 826-833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.027

Hiniker, A., Schoenebeck, S.Y., & Kientz, J.A. (2017). Not at the dinner table: Parents’ and children’s perspectives on family technology rules. CSCW ‘16, February 27-March 02, 2016, San Francisco, CA, USA. https://doi.org/10.1145/2818048.2819940

Ho, S.S., Lwing, M.O., & Lee, E.W.J. (2017).Till logout do us part? Comparison of factors predicting excessive social network sites use and addiction between Singaporean adolescents and adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 632-642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.002

Holloway, D., Green, L., & Livingstone, S. (2013). Zero to eight. Young children and their Internet use. London: EU Kids Online. https://goo.gl/bfZrH8

Hughes, D.J., Rowe, M., Batey, M., & Lee, A (2012). A tale of two sites: Twitter vs. Facebook and the personality predictors of social media usage. Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 561-569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.11.001

International Telecommunication Union (2017). The World in 2017. ICT facts and figures. Geneva, Switzerland: International Telecommunication Union.

Jackson, L.A., Von-Eye, A., Fitzgerald, H.E., Zhao, Y., & Witt, E.A. (2010). Self-concept, self-esteem, gender, race and information technology use. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(3), 323-328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.001

Kuss, D.J., Van-Rooij, A.J., Shorter, G.W., Griffiths, M.D., & Van-de-Mheen, D. (2013). Internet addiction in adolescents: Prevalence and risk factors. Computers Human Behaviour, 29(5), 1987-1996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.04.002

Lauricella, A., Wartella, E., & Rideout, V. (2015). Young children’s screen time: The complex role of parent and child factors. Journal of Applied Developemental Psychology, 36, 11-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.12.001

Livingstone, S. (2008). Taking risky opportunities in youthful content creation: Teenagers’ use of social networking sites for intimacy, privacy and self-expression. New Media & Society, 10(3), 393-411. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444808089415

Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. (2008). Parental mediation and children’s Internet use. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 52(4), 581-599. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150802437396

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., & Ólafsson, K. (2011). Risks and safety on the Internet: The perspective of European children: full findings and policy implications from the EU Kids Online survey of 9-16 year olds and their parents in 25 countries. Deliverable D4. London: EU Kids Online. https://goo.gl/otGdQV

Malo, S., González, M., Casas, F., Viñas, F., Gras, M.E., & Bataller, S. (2014). Adaptación al catalán [Catalan adaptation]. In F. García & G. Musitu (Ed.), AF5. Autoconcepto-Forma 5 (pp. 69-88). Madrid: TEA.

Marino, C., Vieno, A., Pastore, M., Albery, I.P., Frings, D., & Spada, M.M. (2016). Modeling the contribution of personality, social identity and social norms to problematic Facebook use in adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 63, 51-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.07.001

Meerkerk, G.J., Van-den-Eijnden, R.J., Vermulst, A.A., & Garretsen, H.F. (2009). The compulsive Internet use scale (CIUS): Some psychometric properties. Cyberpsychology Behavior, 12(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0181

Müller, K.W., Dreier, M., Beutel, M.E., Duven, E., Giralt, S., & Wölfling, K. (2017). A hidden type of Internet addiction? Intense and addictive use of social networking sites in adolescence. Computers in Human Behaviour, 55, 172-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.007

Ndasauka Y., Hou, J., Wang, Y., Yang, L., Yang, Z., Ye, Z. … Zhang, X. (2016). Excessive use of Twitter among college students in the UK: Validation of microblog excessive use scale and relationships to social interaction and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 963-971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.020

OfCom, U.K. (2016). Children and Parents: Media use and attitudes report. https://goo.gl/9FxdxB

Ólafsson, K., Livingstone, S., & Haddon, L. (2014). Children’s use of online technologies in Europe: a review of the European evidence base (revised edition). London: EU Kids Online. https://goo.gl/NiQxm4

Pérez, R., Rumoroso. A.M., & Brenes, C. (2009). El uso de tecnologías de la información y la comunicación y la evaluación de sí mismo en adolescentes costarricenses. Revista Interamericana de Psicología, 43(3), 610-617.

Reich, S.M., Subrahmanyam, K., & Espinoza, G. (2012). Friending, IMing, and hanging out face-to-face: overlap in adolescents’ online and offline social networks. Development Psychology, 48(2), 356-68. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026980

Rosen, L.D., Whaling, K., Carrier, L.M., Cheever, N.A., & Rokkum, J. (2013). The Media and Technology Usage and Attitudes Scale: An empirical investigation. Computer Human Behavior, 29(6), 2501-2511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.06.006

Ross, C., Orr, E., Sisic, M., Arseneault, J.M., & Simmering, M. (2009). Personality and motivations associated with Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(2), 578-586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.12.024

Salehan, M., & Negabahn, A. (2013). Social networking on smartphones: When mobile phones become addictive. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 2632-2639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.003

Schou, C., Griffiths,M. D., Gjertsen, S.R., Krossbakken, E., Kvam, S., & Pallesen, S. (2013). The relationships between behavioral addictions and the five-factor model of personality. Journal Behavior Addiction, 2(2), 90-99. https://doi.org/10.1556/JBA.2.2013.003

Smahel, D., Helsper, E., Green, L., Kalmus, V., Blinka, L., & Ólafsson, K. (2012). Excessive Internet use among European children. London: EU Kids Online, London School of Economics & Political Science. https://goo.gl/P7rhLT

Tang, J.H., Chen, M.C., Yang, C.Y., Chung, T.Y., & Lee, Y.A. (2016). Personality traits, interpersonal relationships, online social support, and Facebook addiction. Telematics and Informatics, 33, 102-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.06.003

Valkenburg, P., Peter, J., & Schouten, A. (2006). Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents’ well-being and social self-esteem. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9(5), 584-590.https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.584

Vaux, A., Phillips, J., Holly, L., Thomson, B., Williams, D., & Stewart, D. (1986). The social support appraisals (SS-A) scale: Studies of reliability and validity. American Journal of Community Psychology, 14(2), 195-218. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00911821

Viñas, F. (2009). Uso autoinformado de Internet en adolescentes: Perfil psicológico de un uso elevado de la Red. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 9(1), 109-122.

Weinstein, A., & Lejoyeux, M. (2010). Internet addiction or excessive Internet use. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36(5), 277-283. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2010.491880.

Who (Ed.) (2014). World health organization statistics. https://goo.gl/wv8xQe

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Poder entender los factores que predicen un uso excesivo de redes sociales en la adolescencia puede ayudar a prevenir problemas como conductas adictivas, soledad o ciberacoso. El principal objetivo es explorar el perfil psicológico y social de adolescentes que realizan un uso excesivo de redes sociales. Participaron 1.102 adolescentes de 11 a 18 años de Girona (España). Se agruparon los que realizaban un uso excesivo y se exploró su perfil de personalidad (NEO FFI, NEO PI-R y autoconcepto AF5) y el social (apoyo social percibido, tipología autoatribuida de consumo de TIC en la familia y normas de uso de las TIC en el hogar). La prevalencia de uso excesivo fue del 12,8%, siendo mayor en chicas. El perfil de personalidad se caracterizaba por el neuroticismo, la impulsividad y menor autoconcepto familiar, académico y emocional. Percibir elevado consumo de TIC en la madre y hermanos y no disponer de normas de uso define su perfil social. Los factores protectores fueron: la responsabilidad, tener normas de uso y ser chico, y los de riesgo: el uso de redes sociales para distraerse y divertirse, y la elevada percepción de consumo de los hermanos. Se sugiere plantear intervenciones según el sexo y trabajar el uso responsable de las TIC con el entorno familiar, para prevenir problemáticas psicológicas más graves.

1. Introducción

El incremento del uso de las redes sociales y la presencia constante de niños y adolescentes en ellas es un hecho constatado por diversas organizaciones globales e investigadores (Livingstone, Haddon, Görzig, & Ólafsson, 2011; International Telecommunication Union, 2017). Esta utilización continuada de la tecnología puede conducir a un «uso excesivo», un hecho que ha sido reconocido como problema de salud pública (Organización Mundial de la Salud, 2014) y se puede asociar a serios problemas psicológicos y de relaciones interpersonales como la adicción (Ho, Lwing, & Lee, 2017), la soledad (Ndasauka & al., 2016) o el ciberacoso (Casas, Del Rio, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2013). Este estudio utilizará el término «uso excesivo» de redes sociales (Buckner, Castille, & Sheets, 2012), entendiendo que este se da cuando el número de horas de uso afecta al normal desarrollo de la vida cotidiana del adolescente (Castellana, Sánchez-Carbonell, Graner, & Beranuy, 2007; Viñas, 2009), y no solo por lo que se refiere al tiempo invertido, sino también por el impacto que causa en aspectos personales y sociales de la vida del adolescente (Smahel & al., 2012).

En los países del sur de Europa, el uso excesivo de Internet oscila entre un 3% y un 24% (Olafsson, Livingstone, & Haddon, 2014), porcentajes similares a los encontrados en Estados Unidos (Weinstein & Lejoyeux, 2010). En España, un 21,3% de los adolescentes están en riesgo de desarrollar conductas adictivas a Internet debido al uso abusivo de redes sociales (Fundación Mapfre, 2014). Algunos estudios han apuntado diferencias según el sexo en el uso excesivo de redes sociales (Müller & al., 2017): se relaciona a las chicas con el uso intensivo mientras que a los chicos con el uso adictivo entre los consumidores intensivos (3,6% de chicas frente al 4,1% de chicos). Sin embargo, los resultados sobre diferencias por sexo en la literatura no son consistentes. En este sentido, Salehan y Negabahn (2013) no encontraron diferencias por sexo entre la utilización de aplicaciones de redes sociales móviles y la adicción al móvil, en oposición a investigaciones previas que sugieren que las mujeres son más propensas a desarrollar una conducta adictiva.

La fuerte presencia de adolescentes en las redes sociales les permite expresar y desarrollar su personalidad y sus características personales. Además, la naturaleza social de las redes supone una amplia variedad de interacciones y relaciones entre los adolescentes y los demás, como compañeros, familiares o desconocidos. Es por esta razón que realizamos el presente estudio sobre su perfil psicológico, así como sobre factores de personalidad, sociales y de contexto, con el fin de determinar el impacto del uso excesivo de redes sociales entre los adolescentes. Aunque algunos estudios muestran la importancia de analizar estos aspectos conjuntamente (Marino & al., 2016), son más comunes los estudios que los exploran por separado.

Existen investigaciones que han vinculado ciertos rasgos de personalidad con el uso de redes sociales, basándose la mayoría de ellos en la Big Five Theory de Costa y McCrae (1992). A este respecto, se ha observado que elevadas puntuaciones en neuroticismo (Amichai-Hamburger & Vinitzky, 2010; Marino & al., 2016; Tang, Chen, Yang, Chung, & Lee, 2016) y puntuaciones bajas en extraversión (Ross, Orr, Sisic, Arseneault, & Simmering, 2009) están asociadas a un uso adictivo o problemático. Existe una correlación negativa entre el uso de redes sociales, como Facebook o Twitter, y las facetas de apertura a la experiencia y responsabilidad (Hughes, Rowe, Batey, & Lee, 2012; Schou & al., 2013), que actúan como factores protectores. Algunos estudios demuestran que puntuaciones elevadas en amabilidad están asociadas a un uso problemático (Kuss, van-Rooij, Shorter, Griffiths, & Van-der-Mheen, 2013), mientras que otros concluyen que son un indicador de menor riesgo de desarrollar adicción (Meerkerk, Van-den Eijnden, Vermulst, & Garrestsen, 2009). Finalmente, también formaba parte de nuestro objetivo analizar la relación entre impulsividad y uso excesivo de redes sociales, puesto que algunos estudios indican que este parece ser el más potente predictor de consumo problemático (Billieux, Gay, Rochat, & Van-der-Linden, 2010; Billieux, Van-der-Linden, & Rochat, 2008).

Los adolescentes buscan aceptación o validación social a través de las redes sociales, lo cual afecta a su bienestar y su autoestima (Jackson, von-Eye, Fitzgerald, Zhao, & Witt, 2010; Pérez, Rumoroso, & Brenes, 2009; Valkenburg, Peter, & Schouten, 2006). Una baja autoestima se relaciona con un uso más frecuente de las redes sociales (Aydin & Volkan, 2011), y con síntomas de adicción (Bahrainian, Haji-Alizadeh, Raeisoon, Hashemi-Gorji, & Khazaee, 2014).

Internet y las redes sociales permiten a los adolescentes conectarse con sus amigos, crear y reforzar relaciones interpersonales, dar y recibir apoyo social, y cultivar vínculos emocionales (Best, Manktelow, & Taylor, 2014; Frison & Eggermont, 2015; Livingstone, 2008; Reich, Subrahmanyam, & Spinoza, 2012; Tang, Chen, Yang, Chung, & Lee, 2016).

La familia puede proporcionar un entorno protector ante el uso excesivo de las tecnologías, siempre que este contexto social sea percibido como facilitador de apoyo social (Echeburúa, 2012). Las investigaciones demuestran que los progenitores utilizan una variedad de estrategias de mediación para regular el uso que sus hijos hacen de Internet (Durager & Livingstone, 2012; Livingstone & Helsper, 2008), entre ellas, las restricciones o normas de uso (OfCom, 2016; Garmendia, Jiménez, Casado, & Mascheroni, 2016).

Otro factor relacionado con el uso de las tecnologías por parte de los adolescentes es el uso real o percibido de sus progenitores (Hiniker, Shoenebeck, & Kientz, 2016; Lauricella, Wartella, & Rideout, 2015; Livingstone, Haddon, Görzig, & Ólafsson, 2011). En aquellos países europeos donde padres y madres usan Internet diariamente, sus hijos lo usan con más frecuencia; y viceversa (Livingstone & al., 2011). Estos datos parecen indicar que la relación entre el uso que hacen progenitores e hijos no significa solamente que emplean más tiempo usando las tecnologías juntos, sino también que existe un incremento individualizado del tiempo que emplean con sus dispositivos por separado (Lauricella & al., 2015). En palabras de Boyd (2014: 85): «Existe una importante diferencia de perspectiva sobre las posibilidades de los adolescentes para reunirse con amigos, ya que adolescentes y progenitores tienen ideas diferentes sobre cómo debería ser la sociabilidad».

Este estudio transversal tiene como principal objetivo determinar el perfil psicológico y social de los adolescentes de 11 a 18 años que hacen un uso excesivo de redes sociales. A nivel específico, se propone:

• Describir el perfil socio-demográfico y la prevalencia de uso que presenta un grupo de adolescentes identificados como consumidores excesivos frente al grupo normativo.

• Explorar qué variables de personalidad y del contexto social constituyen el perfil de dichos consumidores.

• Evaluar qué variables predicen mejor el uso excesivo de redes sociales en el grupo de edad investigado.

2. Material y metodología

2.1. Participantes

Se utilizó la técnica de muestreo multi-etápico por conglomerados para seleccionar una muestra aleatoria (n=1.218) de entre una población total de 5.365 estudiantes de ESO, bachillerato y formación profesional de la comarca del Alto Ampurdán en Gerona (España). La muestra final comprende 1.102 estudiantes (90,5% de participación) de seis centros educativos, públicos en su mayor parte (91,6%). El 48,1% de los participantes fueron chicos y de edades que oscilaban entre los 11 y los 18 años (M=14,42; SD=1,78). Los cursos escolares comprenden estudiantes de los cuatro cursos de la ESO (n=793), de 1º y 2º de Bachiller (n=278) y de ciclos formativos (n=31).

2.2. Instrumentos

• Escalas para explorar el uso excesivo de redes sociales:

– Tipología autoatribuida de consumo de redes sociales (Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram, Snapchat) (Casas & al., 2007). Escala de ítem único preguntando a los sujetos qué clase de consumidores de redes sociales consideran que son, basándose en cinco respuestas posibles (1=No las uso nunca o muy poco; 2=Soy un/a consumidor/a bajo; 3=Soy un/a consumidor/a medio; 4=Soy un/a consumidor/a bastante elevado; 5=Soy muy alto consumidor/a).

– Escala de actitudes y usos de los medios y tecnologías (Media and technology usage and attitude scale: MTUA) (Rosen, Whaling, Carrier, Cheever, & Rokkum, 2013). Consta de 60 ítems agrupados en 15 subescalas que evalúan la frecuencia de uso y las actitudes hacia las TIC (1=Nunca y 10=Continuamente). Se utilizó la subescala «actividades con redes sociales» (a= .89) para aquellos que indicaban que tenían un perfil en Facebook (se añadió Instagram por ser en la actualidad una de las redes más usadas por los adolescentes).

• Escalas para explorar la personalidad:

– NEO Five Factors Inventory (Costa & Mc-Rae, 1992, 2004): versión reducida de NEO PI-R, que permite evaluar cinco rasgos de personalidad y que consta de 60 ítems (0=En total desacuerdo y 4=Totalmente de acuerdo). Los Alpha de Cronbach para cada escala son: neuroticismo, .64; extraversión, .61; apertura a la experiencia, .62; amabilidad, .53; y responsabilidad, .69. Se añadieron los ítems de la faceta de impulsividad de NEO PI-R (Costa & Mc Rae, 2008), mostrando una consistencia interna de .74.

– Autoconcepto AF5 de García y Musitu (1999). Se aplicó la versión adaptada al catalán (Malo & al., 2014), que consta de 30 ítems contemplando las cinco dimensiones de autoconcepto propuestas por los autores originales (0=Nunca y 10=Siempre). Las propiedades psicométricas de esta escala son muy buenas y similares a las de la escala original: los rangos de consistencia interna oscilan entre .75 (social) y .91 (académico).

• Escalas para explorar el contexto social:

– Escala de Apoyo social percibido (Social support appraisals) (Vaux & al., 1986). El estudio utilizó 14 de los 23 ítems originales, siete referentes a la familia y siete a las amistades (0=De ninguna forma y 10=Muy claramente). La consistencia interna de la dimensión SSA de los amigos es de .91, y la de la familia .92.

– Escala autoatribuida de consumo familiar de las TIC. Escala de ítem único adaptada de Casas y otros (2007), en la que los sujetos clasificaron el tipo de consumo que hacen sus progenitores y hermanos/as.

– Normas de uso de las TIC en el hogar (versión adaptada de Hiniker & al., 2017). Se creó una pregunta de repuesta dicotómica (Sí/No) para explorar si había normas establecidas en el hogar relacionadas con el uso de las TIC (móvil, ordenador, tablet, etc.).

– Ítems de la escala de percepciones relativas al uso de redes sociales (escala creada ad hoc). Se diseñaron 19 ítems para explorar qué sienten y cómo se sienten los adolescentes cuando usan las redes sociales. La pregunta era la siguiente: A continuación encontrarás un conjunto de frases respecto a cosas que puedes sentir cuando usas redes sociales como Facebook, Twitter or WhatsApp. Indica, por favor, tu grado de acuerdo con cada una de ellas. Cuando uso redes sociales… La escala iba de 0 (En total desacuerdo) a 10 (Totalmente de acuerdo). El alfa Cronbach para este estudio fue .92.

2.3. Procedimiento

Se pidió permiso al Departamento de Educación de la Generalitat de Cataluña y a los respectivos consejos escolares y asociaciones de padres y madres de alumnos, a quienes también se informó de los objetivos de la investigación. Se garantizó a directores y alumnos la confidencialidad de los datos y el anonimato. Se dividió el cuestionario en dos partes para evitar fatigar a los participantes y se aplicó en dos sesiones de una hora durante el curso escolar 2016-2017. Dos investigadores estuvieron presentes para resolver preguntas y dudas.

2.4. Análisis de los datos

Con el fin de alcanzar el objetivo general, se crearon dos grupos de consumo de redes sociales: el de uso excesivo y el de uso normativo. Para ello, se agrupó a los participantes que habían contestado «5» (Soy un/a muy alto consumidor/a) en la pregunta sobre tipología auto-atribuida de consumo de las redes sociales y a aquellos que habían respondido «10» (Continuamente) en tres o más ítems en la subescala «actividades con redes sociales» de la MTUA. Se asignó un valor «0» al grupo normativo, y «1» al de uso excesivo.

Para el primer objetivo específico, se calculó la prevalencia de participantes que forman parte de este grupo frente al grupo normativo, utilizando pruebas chi-cuadrado para comparar los resultados por sexo y edad.

Para el segundo, se utilizó una prueba t para analizar tanto el perfil psicológico como el social del grupo de uso excesivo, y se emplearon también pruebas chi-cuadrado para analizar el perfil social.

Para el último objetivo, se llevó a cabo una regresión logística binaria por pasos hacia adelante para verificar las variables que son predictores de uso excesivo. La variable dependiente fue la variable categórica del «grupo de uso», donde se atribuyó «0» al grupo normativo y «1» al grupo que hacía un uso excesivo de redes sociales.

Las covariables fueron las dimensiones de personalidad (NEOFFI, NEOPIR y autoconcepto AF5), las variables sociales (apoyo social, consumo percibido del padre, madre y hermanos/as, presencia o no de normas, y el grupo de variables de la escala ad hoc sobre percepciones relativas al uso de redes sociales), y el sexo.

Todos los análisis se llevaron a cabo usando el paquete estadístico SPSS, versión 23. El nivel mínimo de significación estadística requerido en todas las pruebas fue p<.05.

3. Análisis y resultados

a) Perfil socio-demográfico y prevalencia del grupo de uso excesivo de redes sociales y del grupo normativo.

La prevalencia de chicos (n=34) y chicas (n=78) que forman parte del grupo que hace un uso excesivo de redes sociales es del 12,8%; siendo el porcentaje de chicas (69,4%) significativamente superior (?2= 16,743; p<,001) al de los chicos. No se observan diferencias por razón de edad.

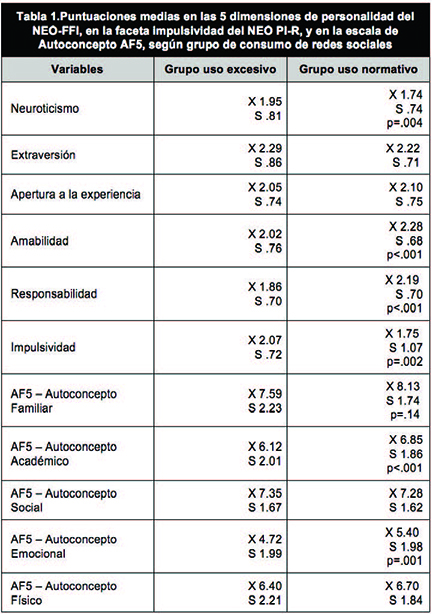

b) Perfil de personalidad del grupo de uso excesivo de redes sociales y del grupo normativo. Los participantes clasificados en el grupo de uso excesivo muestran unas puntuaciones significativamente más elevadas que el grupo normativo en neuroticismo e impulsividad, mientras que en el grupo normativo se observa esta diferencia en las puntuaciones en amabilidad y responsabilidad. Se constata que aquellos adolescentes que hacen un uso excesivo presentan unas puntuaciones significativamente más bajas que los demás consumidores en el autoconcepto familiar, académico y emocional (Tabla 1).

c) Perfil social del grupo de uso excesivo de redes sociales y del grupo normativo. No existen diferencias significativas en la percepción de apoyo social por parte de amigos y familia entre los grupos; sin embargo, sí que se constatan diferencias significativas en la percepción de consumo de las TIC de progenitores y hermanos/as: los adolescentes que hacen un uso excesivo de redes sociales atribuyen un mayor consumo a sus madres y hermanos/as que los del grupo normativo (Tabla 2).

El 59,5% de los participantes informó no tener normas que regulen el uso de las TIC en el hogar. Los grupos muestran diferencias estadísticas significativas (?2(4)=8.390; p=.004): un 72,1% del grupo de uso excesivo afirmó no tener normas (57,6% del grupo normativo), y el 42,2% del grupo normativo afirmó tenerlas (27,9% del grupo de uso excesivo).

d) Variables que predicen el uso excesivo y normativo de redes sociales. El modelo clasificó correctamente al 86,3% de los participantes. La R2 de Nagelkerke indica que el modelo explica el 27,7% de la variabilidad. Los factores protectores ante el uso excesivo de redes sociales son la dimensión de responsabilidad (OR=.512; IC 95%=.355–.739), el autoconcepto familiar (OR=.841; IC 95%=.742 –.953), la existencia de normas reguladoras del uso de las TIC en el hogar (OR=.508; IC 95%= .301–.857) y ser chico (OR=.387; IC 95%=.234-.641); mientras que los factores de riesgo están relacionados con el uso de redes sociales para distraerse después de las tareas escolares (OR=1.157; IC 95%=1.043-1.283), para divertirse (OR=1.475; IC 95%=1.258-1.729) y la percepción del consumo de las TIC por parte de hermanos/as (OR=1.229; IC 95%=1.036-1.458) (Tabla 3).

4. Discusión y conclusiones

El objetivo principal de este trabajo era describir el perfil psicosocial de una muestra de adolescentes españoles de edades comprendidas entre los 11 y 18 años que hacen un uso excesivo de redes sociales. Los datos utilizados para construir este perfil se basan en resultados obtenidos a partir del modelo de los cinco factores de personalidad, el autoconcepto, las variables contextuales de apoyo social de amigos y familia, y la percepción del consumo familiar de las TIC. A nivel específico, encontramos una mayor prevalencia de chicas que de chicos en el grupo de uso excesivo (Müller & al., 2017); y aunque la edad no parece ser un elemento discriminador, sí que se ha observado que es a los 13 (21,4%) y a los 16 (18,8%) años cuando aparece un uso más intensivo de las tecnologías (Caldevilla, 2010). La prevalencia de uso excesivo en este estudio (12,8%) fue moderado, situándose en la banda intermedia de los valores detectados en estudios anteriores (Olafsson & al., 2014; Weinstein & Lejoyeux, 2010).

En segundo lugar, los resultados de este estudio corroboran los datos de investigaciones anteriores que identifican características de personalidad diferenciadas entre el grupo que hace un uso excesivo de redes sociales y el grupo normativo, presentando el primero rasgos de neuroticismo e impulsividad, lo que confirma su relación con conductas adictivas y problemáticas. Algunos adolescentes con puntuaciones altas en neuroticismo usan Facebook tanto para regular su estado de ánimo (Marino & al., 2016; Tang & al., 2016) como para experimentar la sensación de pertenecer a un grupo y de satisfacer su necesidad de sentirse seguros (Amichai-Hamburger & Vinitzky, 2010). Además, la tendencia a actuar precipitadamente como respuesta a situaciones emocionales intensas, como el uso de redes sociales, es un indicador de uso problemático (Billieux & al., 2010; Billieux & al., 2008). El grupo de uso normativo se caracteriza por presentar un mayor grado de amabilidad y responsabilidad, factores ambos que están relacionados con un menor riesgo de desarrollar conductas adictivas (Meerkerk & al., 2009; Schou & al., 2013). Sin embargo, estos resultados deberían interpretarse con cautela debido a los bajos índices de consistencia interna observados en algunas de las escalas.

La autoestima es otro constructo que presenta diferencias entre los grupos: el grupo de uso excesivo muestra una menor autovaloración de cómo son percibidos por su familia, por el mundo académico –profesores, compañeros de clase y ellos mismos– y de nivel de comprensión de sus propias emociones y de cómo las muestran ante los demás (García & Musitu, 1999). Mantener buenos niveles de autoestima y autoconcepto, sobre todo en algunas de sus dimensiones, actúa como factor protector ante las adicciones a las TIC (Echeburúa, 2012). Como ejemplo, Pérez y otros (2009) observaron que los adolescentes que hacían un uso variado e intenso de su tiempo libre, y a su vez un uso bajo de los medios de entretenimiento y de los nuevos medios como Internet, mostraban una autovaloración académica más positiva que aquellos con un tiempo libre menos rico y diverso, y que hacen mayor uso de los medios de entretenimiento y de los nuevos medios.

Respecto a las variables contextuales, no se encontraron diferencias entre los grupos en cuanto al apoyo social percibido de amigos o familia, aunque existen investigaciones previas que muestran que dar y recibir apoyo social online puede ser una motivación para hacer un uso más intensivo de redes sociales (Tang & al., 2016). Sin embargo, el papel que juega la percepción del consumo familiar de las TIC aparece como factor diferencial en la formación de una u otra tipología de consumidor de redes sociales (Hiniker & al., 2016). Nuestros resultados corroboran la idea de que los adolescentes que forman parte del grupo de consumidores excesivos perciben que sus madres y hermanos/as también hacen un uso intensivo de estas tecnologías, funcionando como modelos de consumo (Livingstone & al., 2011). Tal y como se apunta en estudios anteriores, este aspecto parece incidir no solo en cómo la familia usa las TIC sino también en el uso individualizado que hacen los hijos (Lauricella & al., 2015). En el contexto actual, donde todos los miembros de la familia, incluyendo a los más jóvenes, usan frecuentemente múltiples dispositivos (Holloway, Green, & Livingstone, 2013) cobra importancia el papel jugado por progenitores y familiares en el aprendizaje vicario del uso responsable de las TIC. Nuestro estudio revela que la mitad de la muestra afirma no tener normas que regulen el uso de las TIC en el hogar, confirmando que la educación no debería ceñirse únicamente a un uso regulado por normas (OfCom, 2016; Garmendia & al., 2016); siendo este porcentaje incluso superior (72,1%) en el grupo que hace un uso excesivo. Durager y Livingstone (2012) sugieren que una de las estrategias más efectivas para regular un uso responsable, que incremente las oportunidades y prevenga riesgos, es la mediación activa, hablando activamente o compartiendo actividades online con los hijos. Por el contrario, el establecimiento de normas, restricciones o estrategias técnicas de mediación –como los filtros parentales– se relaciona con un menor riesgo online, aunque esto puede comportar que los hijos sean menos libres para explorar, aprender y desarrollar resiliencia, obteniendo un menor aprovechamiento de las oportunidades y habilidades digitales.

El presente estudio no está exento de limitaciones. La muestra, aunque representativa de una comarca y de un rango de edad, no nos permite hacer extrapolación a otros grupos de población. Los datos han sido recopilados mediante escalas de autovaloración que no garantizan ni la fiabilidad ni validez de los mismos, puesto que algunos sujetos pueden haber respondido basándose en la deseabilidad social. Por tratarse de un estudio transversal, no podemos establecer relaciones causales, si bien futuros estudios longitudinales de cohorte nos podrían proporcionar un perfil más sólido de uso excesivo de redes sociales, así como de las variables de protección y de riesgo. Teniendo en cuenta el porcentaje de varianza explicada, deberían examinarse otras variables que no han sido tratadas en este estudio, tanto del contexto social como de personalidad, ya que pueden estar relacionadas con el perfil estudiado.

A pesar de estas limitaciones, nuestro estudio nos permite sustentar hallazgos previos ya que encontramos: a) Diferencias según sexo entre consumidores excesivos y normativos, pero no según edad; b) Una prevalencia del uso excesivo de los adolescentes españoles similar a la de países de Europa y América; c) La impulsividad y el neuroticismo como principales variables de personalidad relacionadas con el uso excesivo; d) Aunque no hallamos diferencias entre los grupos de consumidores en el apoyo social percibido, el grupo de consumidores excesivos percibe un consumo familiar de las TIC significativamente mayor (madre y hermanos/as). Además, nuestros datos demuestran que el sexo, la responsabilidad, tener normas en el hogar y el autoconcepto familiar predicen negativamente el uso excesivo de redes sociales, mientras que la percepción de uso de las TIC de los hermanos/as, el uso de redes sociales para divertirse y su uso después de la escuela para distraerse lo predicen positivamente. Según estas variables predictivas, observamos dos perfiles de adolescentes: a) Constituye un perfil de riesgo ser chica, usar redes sociales para distraerse o divertirse, y percibir un uso elevado de las TIC de los hermanos/as; b) Constituye un perfil de protección ser chico, con una puntuación elevada en responsabilidad, un autoconcepto académico elevado y tener normas de uso de las TIC en el hogar. Deberíamos mencionar que el porcentaje de varianza explicada por el modelo de regresión es más bien baja y que, por consiguiente, podríamos considerar que hay otras variables no incluidas en este estudio que pueden predecir el uso excesivo.

Estos hallazgos nos permiten llegar a ciertas conclusiones: 1) Formar parte del grupo de consumidores excesivos comporta pasar más tiempo usando redes sociales y puede convertirse en un riesgo potencial, afectando al día a día de los adolescentes; en este sentido, estudios recientes señalan que el uso intensivo de redes sociales en la adolescencia está relacionado con la adicción a Internet y la ansiedad psicológica (Müller & al., 2017); 2) El perfil de este grupo de consumidores está conformado por la combinación de rasgos de personalidad y el contexto más inmediato en el que aprenden a usar las TIC, hecho que revela la necesidad, por un lado, de hacer más estudios para explorar estas dos variables y, por otro lado, la necesidad de diseñar: a) Intervenciones específicas entre los jóvenes para regular los rasgos de personalidad asociados directamente al uso excesivo –como la impulsividad– mediante programas de formación en conciencia plena (Mindfulness) (Franco, de la Fuente, & Salvador, 2011); b) Políticas sociales que promuevan un uso más responsable en el contexto familiar (Gómez, Harris, Barreiro, Isorna, & Rial, 2017); finalmente; c) Como hemos visto en anteriores estudios (Müller & al., 2017) puesto que el hecho de ser chica es un factor de riesgo de uso excesivo, debería tenerse en cuenta la variable sexo a la hora de diseñar propuestas específicas de intervención para prevenir conductas problemáticas de uso de las TIC.

En general, los resultados de este estudio pueden constituir un primer paso para la elaboración de nuevas medidas sobre el uso excesivo de redes sociales que evalúen las facetas de personalidad de los adolescentes y que también analicen de manera más profunda el contexto del uso familiar en el cual están socializados niños y adolescentes. Siguiendo el modelo ecológico de Bronfenbrenner (Bronfenbrenner & Evans, 2000) podríamos explorar otros contextos de socialización como la vida escolar o el ocio y el tiempo libre (véase capítulo 3 de Boyd, 2014), e incluso explorar qué valores sociales se ven implicados en el uso excesivo de las TIC (por ejemplo, el hedonismo, la seguridad o el individualismo). Todas estas variables nos permitirían tener una visión más plural de la complejidad de esta realidad psicológica.

Apoyos

Los autores forman parte del equipo de investigación ERIDIQV (www.udg.edu/eridiqv) de la Universitat de Girona, reconocido como Grupo de Investigación Consolidado por la Generalitat de Cataluña (2014-SGR-1332 y 2017 SGR 162), que ha financiado la obtención de datos para este estudio.

Referencias

Amichai-Hamburger, Y., & Vinitzky, G. (2010). Social network use and personality. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 1289-1295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.018

Aydin, B., & Volkan, S. (2011). Internet addiction among adolescents: the role of self-steem. Procedia and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 3500-3505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.325

Bahrainian, S., Haji-Alizadeh, K., Raeisoon, M., Hashemi-Gorji, O., & Khazaee, A. (2014). Relationship of Internet addiction with self-esteem and depression in university students. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, 55(3), 86-89.

Best, P., Manktelow, R., & Taylor, B. (2014). Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Children and Youth Services, 41, 27-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.001

Billieux, J., Gay, P., Rochat, L., & Van-der-Linden, M. (2010). The role of urgency and its underlying psychological mechanisms in problematic behaviours. Behaviour Research and Therapy 48(11), 1085-1096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.07.008

Billieux, J., Van-der-Linden, M., & Rochat, L. (2008). The role of impulsivity in actual and problematic use of the mobile phone. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 22, 1195-1210. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1429

Boyd, D. (2014). It’scomplicated. The social lives of networked teens. Yale University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Evans, G.W. (2000). Developmental science in the 21st century: Emerging theoretical models, research designs, and empirical findings. Social Development, 9, 115-125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00114

Buckner, J.E., Castille, C.M., & Sheets, T.L. (2012). The five factor model of personality and employees’ excessive use of technology. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1947-1953. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.05.014

Caldevilla, D. (2010). Las Redes Sociales. Tipología, uso y consumo de las redes 2.0 en la sociedad digital actual. Documentación de las Ciencias de la Información, 33, 45-68.

Casas, F., Madorell, L., Figuer, C., González, M., Malo, S., García, M. ... Babot, N. (2007). Preferències i expectatives dels adolescents relatives a la televisió a Catalunya. Barcelona: Consell Audiovisual de Catalunya.

Casas, J.A., Del-Rio, R., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2013). Bullying and cyberbullying: Convergent and divergent predictor variables. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 580-587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.015

Castellana, M., Sánchez-Carbonell, X., Graner, C., & Beranuy, M. (2007). El adolescente ante las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación: Internet, móvil y videojuegos. Papeles del Psicólogo, 28(3), 196-204.

Costa, P.T., & Mc-Crae, R.R. (2008). NEO PI-R Inventario de Personalidad NEO Revisado Manual. Madrid, TEA.

Costa, P.T., & McCrae, R.R. (1992). The revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO-five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Costa, P.T., & McCrae, R.R. (2004). A contemplated revision of the NEO Five-Factor Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 587-596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00118-1

Durager, A., & Livingstone, S. (2012). How can parents support children’s Internet safety? London: EU Kids Online. https://goo.gl/Bh3Lw1

Echeburúa, E. (2012). Factores de riesgo y factores de protección en la adicción a las nuevas tecnologías y Redes Sociales en jóvenes y adolescentes. Revista Española de Drogodependencias, 4, 435-448.

Franco, C., de la Fuente, M., & Salvador, M. (2011). Impacto de un programa de entrenamiento en consciencia plena (mindfulness) en las medidas de crecimiento y la autorrealización personal. Psicothema, 23(1), 58-65.

Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2015). Exploring the relationships between different types of Facebook use, perceived online social Support, and adolescents’ depressed mood. Social Science Computer Review, 34(2), 153-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314567449.

Fundación Mapfre (Ed.) (2014). Tecnoadicción. Más de 70.000 adolescentes son tecnoadictos. Seguridad y Medioambiente, 1, 66-69.

García, F., & Musitu, G. (1999). Autoconcepto forma 5. AF5. Manual. Madrid: TEA.

Garmendia, M., Jiménez, E., Casado, M., & Mascheroni, G. (2016). Riesgos y oportunidades en Internet y uso de dispositivos móviles entre menores españoles (2010-2015). Net children and go mobile. Final Report March 2016. https://goo.gl/aFSxsB

Gómez, P., Harris, S.K., Barreiro, C., Isorna, M., & Rial, A. (2017). Profiles of Internet use and parental involvement, and rates of online risks and problematic Internet use among Spanish adolescents. Computer in Human Behaviour, 75, 826-833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.027

Hiniker, A., Schoenebeck, S.Y., & Kientz, J.A. (2017). Not at the dinner table: Parents’ and children’s perspectives on family technology rules. CSCW ‘16, February 27-March 02, 2016, San Francisco, CA, USA. https://doi.org/10.1145/2818048.2819940

Ho, S.S., Lwing, M.O., & Lee, E.W.J. (2017).Till logout do us part? Comparison of factors predicting excessive social network sites use and addiction between Singaporean adolescents and adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 632-642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.002

Holloway, D., Green, L., & Livingstone, S. (2013). Zero to eight. Young children and their Internet use. London: EU Kids Online. https://goo.gl/bfZrH8

Hughes, D.J., Rowe, M., Batey, M., & Lee, A (2012). A tale of two sites: Twitter vs. Facebook and the personality predictors of social media usage. Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 561-569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.11.001

International Telecommunication Union (2017). The World in 2017. ICT facts and figures. Geneva, Switzerland: International Telecommunication Union.

Jackson, L.A., Von-Eye, A., Fitzgerald, H.E., Zhao, Y., & Witt, E.A. (2010). Self-concept, self-esteem, gender, race and information technology use. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(3), 323-328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.001

Kuss, D.J., Van-Rooij, A.J., Shorter, G.W., Griffiths, M.D., & Van-de-Mheen, D. (2013). Internet addiction in adolescents: Prevalence and risk factors. Computers Human Behaviour, 29(5), 1987-1996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.04.002

Lauricella, A., Wartella, E., & Rideout, V. (2015). Young children’s screen time: The complex role of parent and child factors. Journal of Applied Developemental Psychology, 36, 11-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.12.001

Livingstone, S. (2008). Taking risky opportunities in youthful content creation: Teenagers’ use of social networking sites for intimacy, privacy and self-expression. New Media & Society, 10(3), 393-411. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444808089415

Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. (2008). Parental mediation and children’s Internet use. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 52(4), 581-599. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150802437396

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., & Ólafsson, K. (2011). Risks and safety on the Internet: The perspective of European children: full findings and policy implications from the EU Kids Online survey of 9-16 year olds and their parents in 25 countries. Deliverable D4. London: EU Kids Online. https://goo.gl/otGdQV

Malo, S., González, M., Casas, F., Viñas, F., Gras, M.E., & Bataller, S. (2014). Adaptación al catalán [Catalan adaptation]. In F. García & G. Musitu (Ed.), AF5. Autoconcepto-Forma 5 (pp. 69-88). Madrid: TEA.

Marino, C., Vieno, A., Pastore, M., Albery, I.P., Frings, D., & Spada, M.M. (2016). Modeling the contribution of personality, social identity and social norms to problematic Facebook use in adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 63, 51-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.07.001

Meerkerk, G.J., Van-den-Eijnden, R.J., Vermulst, A.A., & Garretsen, H.F. (2009). The compulsive Internet use scale (CIUS): Some psychometric properties. Cyberpsychology Behavior, 12(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0181

Müller, K.W., Dreier, M., Beutel, M.E., Duven, E., Giralt, S., & Wölfling, K. (2017). A hidden type of Internet addiction? Intense and addictive use of social networking sites in adolescence. Computers in Human Behaviour, 55, 172-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.007

Ndasauka Y., Hou, J., Wang, Y., Yang, L., Yang, Z., Ye, Z. … Zhang, X. (2016). Excessive use of Twitter among college students in the UK: Validation of microblog excessive use scale and relationships to social interaction and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 963-971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.020

OfCom, U.K. (2016). Children and Parents: Media use and attitudes report. https://goo.gl/9FxdxB

Ólafsson, K., Livingstone, S., & Haddon, L. (2014). Children’s use of online technologies in Europe: a review of the European evidence base (revised edition). London: EU Kids Online. https://goo.gl/NiQxm4

Pérez, R., Rumoroso. A.M., & Brenes, C. (2009). El uso de tecnologías de la información y la comunicación y la evaluación de sí mismo en adolescentes costarricenses. Revista Interamericana de Psicología, 43(3), 610-617.

Reich, S.M., Subrahmanyam, K., & Espinoza, G. (2012). Friending, IMing, and hanging out face-to-face: overlap in adolescents’ online and offline social networks. Development Psychology, 48(2), 356-68. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026980

Rosen, L.D., Whaling, K., Carrier, L.M., Cheever, N.A., & Rokkum, J. (2013). The Media and Technology Usage and Attitudes Scale: An empirical investigation. Computer Human Behavior, 29(6), 2501-2511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.06.006

Ross, C., Orr, E., Sisic, M., Arseneault, J.M., & Simmering, M. (2009). Personality and motivations associated with Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(2), 578-586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.12.024

Salehan, M., & Negabahn, A. (2013). Social networking on smartphones: When mobile phones become addictive. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 2632-2639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.003

Schou, C., Griffiths,M. D., Gjertsen, S.R., Krossbakken, E., Kvam, S., & Pallesen, S. (2013). The relationships between behavioral addictions and the five-factor model of personality. Journal Behavior Addiction, 2(2), 90-99. https://doi.org/10.1556/JBA.2.2013.003

Smahel, D., Helsper, E., Green, L., Kalmus, V., Blinka, L., & Ólafsson, K. (2012). Excessive Internet use among European children. London: EU Kids Online, London School of Economics & Political Science. https://goo.gl/P7rhLT

Tang, J.H., Chen, M.C., Yang, C.Y., Chung, T.Y., & Lee, Y.A. (2016). Personality traits, interpersonal relationships, online social support, and Facebook addiction. Telematics and Informatics, 33, 102-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.06.003

Valkenburg, P., Peter, J., & Schouten, A. (2006). Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents’ well-being and social self-esteem. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9(5), 584-590.https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.584

Vaux, A., Phillips, J., Holly, L., Thomson, B., Williams, D., & Stewart, D. (1986). The social support appraisals (SS-A) scale: Studies of reliability and validity. American Journal of Community Psychology, 14(2), 195-218. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00911821

Viñas, F. (2009). Uso autoinformado de Internet en adolescentes: Perfil psicológico de un uso elevado de la Red. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 9(1), 109-122.

Weinstein, A., & Lejoyeux, M. (2010). Internet addiction or excessive Internet use. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36(5), 277-283. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2010.491880.

Who (Ed.) (2014). World health organization statistics. https://goo.gl/wv8xQe

Document information

Published on 30/06/18

Accepted on 30/06/18

Submitted on 30/06/18

Volume 26, Issue 2, 2018

DOI: 10.3916/C56-2018-10

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?