Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Global ageing has led European and international organizations to develop programs for active ageing, in order to reconstruct the role of the elderly in society. Active ageing includes social communication aspects which have been the subject of less research than other more pressing ones linked to physical and economic characteristics. This research is centered on these communication variables; it addresses the link between the elderly and Internet, and has two main objectives: to discover how useful Internet is for this age group, and to explain the potential this medium has for active ageing. To do so, a qualitative methodology is used based on three discussion groups, each made up of four or five people between the ages of 56 and 81, led by an expert moderator. The results of the qualitative content analysis of each discussion indicate that the Internet is a source of opportunities for the elderly, and this potential may be divided into four categories: Information, communication, transactions and administration, together with leisure and entertainment. This potential improves the quality of life for the elderly and contributes to their active ageing. However, to maximize this, e-inclusion programs and methodologies are needed to make the Internet user-friendlier for the elderly and provide them with training in digital skills.

1. Introduction and state of the question

According to a recent UN report (2014), in 2050, Spain will become the third «oldest» country in the world, with 34.5% of its population over the age of 65 (Aunión, 2014). The 2012 Eurobarometer states that, depending on the European Union country, the concept of what ‘elderly’ means is very different, but, on average, anyone over the age of 63.9 is considered «elderly» (TNS Opinion & Social, 2012). In view of this progressive ageing of the population, «the challenge in the 21st century is to delay the onset of disability and ensure optimal quality of life for older people» (WHO, 2001: 3). Thus, during the 1980s, the European Union began to develop a new policy on ageing, which meant moving from a passive attitude to a more proactive one among the elderly. This new approach allows for greater well-being of older people and contributes to the economic sustainability of the social protection systems in the European Union, and thus can unify the interests of all stakeholders (citizens, NGOs, business interests and policy makers) (Walker, 2009).

Active ageing was defined by the WHO (2002: 79) as «the process of optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age». This concept is linked to both physical and social and mental well-being, and also refers to the participation and integration of old people in society (WHO, 2002; OMS, 2002).

From a psychological perspective, the work of Fernández-Ballesteros et al. (2010) shows the criteria and predictors for what they call «successful ageing», which spring from the three variables with which Rowe and Khan (1987, 1997) characterized the opportunities of ageing: «Usual», «pathological» and «successful». In this study, based on the ESAP (European Survey on Aging Protocol) and its PELEA version (Protocol for the Longitudinal Study of Active Ageing), social and participative engagement was identified as one of the aspects of «successful ageing». It is on this point that this work is based and it is also the point which has inspired the least research in comparison with other more urgent aspects linked to health or economics.

The European Union (2011) declared the year 2012 as the «European Year for Active Ageing and Solidarity between Generations» in order to combat the effect of demographic ageing on the social models of the member states, and to promote the creation of an active ageing culture as a permanent process in a multi-age society.

Since the 1990s, the European Commission has developed programs intended to tackle this new challenge, by building initiatives which lead to greater levels of independence and integration of the older age group. Within these programs, communication has been considered a key element for the development of active ageing. Nevertheless, in spite of its importance, Nussbaum and Coupland (2008) consider that communication is not yet a core concept in studies on ageing.

However, there is no doubt that ICT can offer new possibilities for the elderly. For this reason the R&D Report on ageing underlines the need to encourage research into technological aspects to combat the effects of human ageing (Parapar & al., 2010).

It has been proven that it is precisely in old age that ICT offer relevant opportunities for the improvement of psychological processes (Aldana, García-Gómez & Jacobo, 2012; Elosua, 2010), social aspects (Martínez-Rodríguez, Díaz-Pérez & Sánchez-Caballero, 2006), and issues that are clearly related to dependency (Del-Arco & San-Segundo, 2011; Malanowski, Özcivelek & Cabrera, 2008). Ala-Mutka et al. (2008) suggest various policies with a holistic focus in order to improve the quality of life of the elderly through a process of permanent training, based on ICT, in which the involvement of the institutions and younger generations is essential. It also seems crucial that such methodologies should include instruments for the assessment of the media competences of the elderly (Tirado & al., 2012). However, it seems complicated to decide with certainty if ICT can improve the quality of life for the elderly, as there are three variables which are decisive in measuring this impact: Wealth, health, and social relations (Gilhooly, Gilhooly & Jones, 2009).

In this context, Internet appears to offer great support for active ageing, and should be taken into account in the development of active ageing policies in present-day and future societies. It has been predicted that the percentage of older Internet users will grow in the next few years; but this growth will presumably be slow due to the difficulties of access this group has because of its low level of education (lower than secondary-education) (Fundación Vodafone, 2012). In spite of this, the general spread of web accessibility and the abundance of devices that enable mobile access have provided new ways of improving the quality of life. But the undeniable potential offered by the Internet to other younger groups appears to be limited in the case of the elderly. The digital divide is more evident between these two collectives in modern societies. On this point, the elderly make up a group who are at risk of exclusion –or of isolation– (Querol, 2012; Fernández-García, 2011). ICT can counteract this, by promoting the collaboration and development of learning communities who will overcome physical limitations (Shepherd & Aagard, 2011), and by offering them an opportunity for social integration and healthy orientation (Agudo, Fombona & Pascual, 2013).

This divide between the young and the old generations, brought about by discrimination in access to ICT, has become one of the great challenges for the UN and the European Commission. Thus, during the «World Summit on the Information Society», organized by the United Nations International Telecommunications Union in Geneva (2003) and in Tunisia (2005), a commitment was declared to those groups who are at risk of marginalization (UN, 2003). Regarding the same concern, the European Commission has carried out several initiatives, outstanding amongst which is «i2010», which intends to promote accessibility and ensure that all groups will learn basic digital skills (European Commission, 2005). A year later, «e-inclusion» is considered a key element in achieving integration of ICT and their use in people’s lives in order to guarantee their participation in the information society, to reduce the digital divide and to promote better quality of life and social cohesion (European Commission, 2006). The «e-inclusion» policies should focus on helping the most excluded individuals to use ICT productively (European Commission, 2007). On this point, the European Union Digital Agenda 2020 aims to make the most of the potential of ICT «to respond to the needs of an ageing population» and so to contribute to active ageing (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, 2012: 18). At present, one of the aims regarding the use of ICT in order to achieve independent living for the elderly is to reduce their need for assistance (Bubbolini, 2014).

As we have indicated, despite the fact that recent studies show that social aspects such as communication have been identified as an important part of active ageing, there has been less research on this subject in comparison with other more pressing issues. This piece of research focuses precisely on this type of communication variables and tackles two essential objectives:

a) Awareness of the multiple uses of the Internet for the elderly.

b) Explanation of the reasons that make this medium a source of opportunities for active ageing.

2. Material and method

The methodological design responds to a qualitative typology. The discussion group was considered, in this case, as the most suitable qualitative tool, because it admits more in-depth explanation, which will allow us to discover the potential of the Internet.

Thus, a model was designed to gather first-hand data on the experiences of older people with Internet. This design is based on three discussion groups, guided and moderated by an expert, and the later qualitative analysis of the content expressed in each discussion.

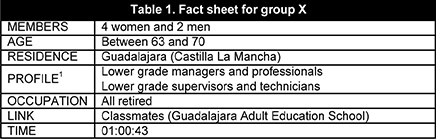

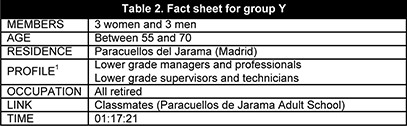

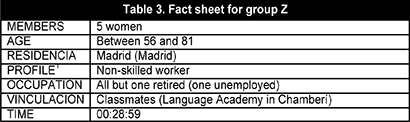

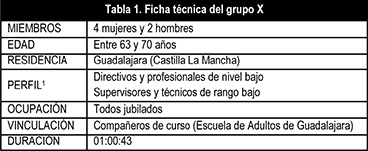

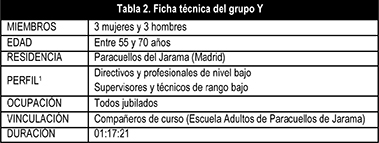

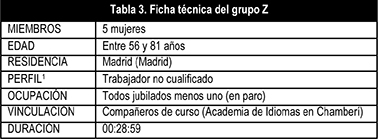

The members of the sample were chosen in accordance with the following criteria: Internet users of both sexes, aged between 56 and 81, belonging to the middle class, with different education levels, who reside in urban areas of different sizes and show a clear interest in an active life (they are all linked through being involved in continuous education programmes). In this way, sufficient heterogeneity was achieved to guarantee greater wealth and variety in the opinions expressed.

The procedure followed by the moderators was to interfere as little as possible, with the help of a position statement which gives the major points to be dealt with in the group, but also to help the participants to freely express the use they make of the Internet as a means to improve their everyday habits, and to optimize their quality of life.

The length of each group discussion varied, which is why the Group Z conversation was shorter. The conversation was guided but not conditioned by the moderator

The group discussions were recorded and transcribed, thus permitting a qualitative analysis of the contents which has allowed us to identify relevant aspects in the participants’ experiences regarding the proposed objectives. Such analysis is focused on the corpus of textual data resulting from the transcription of speech, together with the description and interpretation of same in order to, later, establish the possibility categories offered by the Internet for active ageing. This taxonomy responds to a subject criterion in accordance with units of content which were defined «by taking as units those fragments that express an idea referred to a topic» (Gil, García & Rodríguez, 1994: 192).

3. Results

The experiences narrated by the participants in the three discussion groups have shown some concurrence in considering the Internet to be a source of opportunities to optimize their habits for living and to contribute to their active ageing.

The richest results were obtained from the experiences from group X and group Y; those of group Z were less productive. These data have been classified into four categories of opportunities, according to the results of the consensus detected in the analysis of the discourse. As it has been explained, this classification corresponds to a subject criterion which permitted its own nomenclature at a later stage. Moreover, isolated quotes from some of the participants have been incorporated as they reflect a consensus on the opportunities which the Internet offers them.

3.1. Information opportunities

For the elderly the Internet has become a magnificent source of information. It is a large encyclopedia, dynamic, comfortable and easily accessible, which allows them to find information on multiple subjects: «I consult Internet a lot, for anything and everything» (group X, 2014).

Google is the only search engine used by the participants in the different groups and the resource through which they access other information sites which are of interest to them. However, they admit to not using other types of information platforms such as blogs and forums.

The recurring topics for consultation found in the discourse analysis of the groups can be classified into the following areas:

a) Current affairs: This age-group shows special interest in the news that affects the areas in which they are involved (province, town, country) and some of them confess a preference for digital press rather than the traditional one.

b) Health issues: Interest in this type of information is widespread among the participants in all the discussion groups. Nevertheless, they always look for information which affects them more or less directly: «If this hadn’t happened to me, I wouldn’t look it up on Google» (group Y, 2014). In general, they look for data on:

• Illnesses. In this case, they always trust the diagnosis of the healthcare professional and are simply interested in natural remedies or want to find out more or better understand the information offered by the physician, but always keep in mind that «Internet can never take the place of a doctor » (group Y, 2014).

• Doctors. On this point, they look for information about the professionals who are going to treat them and/or members of their families and/or friends.

• Hospitals. They are interested in the quality of the centers in which they are treated: «I always get into information about the hospital, about the prizes they have been given, the awards they have received; that is the prestige of the hospital» (group X, 2014).

• Healthy diets. For them Internet is a source of information on healthy habits, although they consider that diets usually change.

c) Culture and general interest topics: This age group, particularly the women, frequently use the web to find recipes. They often look for information about things that intrigue them, for example: «When there is a word that doesn’t sound familiar, Wikipedia or a country. I mean, the information on Wiki, it’s just sensational» (group Y, 2014). Even to resolve one-off technical problems: «Well, any question that arises or that I don’t know, technical information, anything there is» (group X, 2014). Regarding culture, they also look for information on exhibitions, travel, theatre and other activities related with their leisure and entertainment.

An important aspect that affects the information opportunities offered by Internet refers to the reliability of the data. On this point, the participants are wary: «I don’t believe everything they say […] There are a lot of smart asses» (group X, 2014). Therefore, they realize that Internet: «It is not the panacea. There is a lot of rubbish too» (group Y, 2014). For this reason, they stress the importance of verifying the information and finding it in reliable sources. Apart from the reliability of the source of information, there are other variables which influence their feeling of more or less confidence in the data, such as the design and appearance of the website or the prestige of said platform.

Particularly for health information, they are especially cautious and express warnings on moderation in the use of the Internet for access to this type of data, so as not to become hypochondriacs: «You make your life a disease» (group Z, 2014).

3.2. Communication opportunities

Within the communication opportunities offered by the Internet, the one most used by the participants in the research is email. Several members of the groups consider that smartphones have made communication easier, offering more immediate connection to email or the social networks. They have concentrate the use of the computer to those personal interactions to which they prefer to devote most time, such as communication with family members who live abroad, using platforms like Skype: «The computer, well I use it for Skype, if I’m talking to Manuela [her daughter]» (group Y, 2014).

Moreover, the increase in mobile devices has, amongst this group, promoted the possibility of communicating by means of social networks such as WhatsApp and Facebook. As is common amongst other age groups, WhatsApp has replaced traditional telephone communications: «WhatsApp, right, I’ve stopped using the telephone» (group X, 2014). On the other hand, Facebook is seen as a means of interaction with friends and family members, less immediate than WhatsApp, but more enjoyable for many of the participants, as it allows them to share experiences: «Well, my daughters sent me photos of my grandchildren» (group Z, 2014). Belonging to Facebook is determined by a link of friendship or a family relationship with other people who belong to it. This fact and the feeling that attending to several social profiles is a waste of time are variables which explain why they do not belong to other networks such as Twitter. Those with a negative opinion on social networks prefer not to spend time on them: «But as for Facebook, if you really want to know what I believe, I think it’s a lot of rubbish» (group X, 2014).

In general, the communication opportunities offered by the web facilitate social interaction which involves the elderly in relationships that strengthen their social abilities and keep isolation away; these are effects that improves their motivation, self-esteem and satisfaction. Additionally, making the most of these opportunities causes admiration amongst their peers: «I’m very pleased to say that on WhatsApp the person I send most messages to is a gentleman of 93» (group X, 2014).

3.3. Transactional and administrative opportunities

Internet has made certain everyday habits easier for older people, due to the possibilities it offers to carry out «online» transactions and administrative processes. On this point Miranda (2004) states that these operations are particularly useful for those people who have limited mobility because of health problems. Thus the elderly may feel that these possibilities are very beneficial and convenient.

The members of the groups habitually use the web for their income tax returns or to manage bills and bank accounts: «I, for example, for the natural gas bills, the telephone bills and everything, everything, I do it on Internet, and bank on Internet, except for withdrawing money because I don’t let me» (group Z, 2014). They also use it frequently to ask for appointments (to see the doctor or for bureaucratic processes), and emphasize its convenience and immediacy compared to other ways of doing so, such as going to the centre or telephoning.

Regarding «online» shopping, its use is not found to be very widespread although some people use it to organize travel, to buy tickets for the cinema or the theatre, etc. Only one participant showed interest in buying products «online»: «I really like getting into buying and selling. I buy things from abroad […] things I need that are more expensive in Spain» (group X, 2014).

3.4. Leisure and entertainment opportunities

Apart from facilitating information on leisure and entertainment, the Internet offers direct entertainment consumption, although these possibilities are the least exploited by this group. In this regard, some members of the discussion groups confess that they consume radio and television programs online, generally because they have missed the live broadcast; this is the most «widespread online» leisure consumption amongst the participants in the study.

A member of the group says: «Well, I do use it […] also to play sudokus, to tell you the truth, I play to sharpen up my brain a little» (group X, 2014). In this way, he shows his interest in promoting his cognitive activity.

Another member of a different group confesses that he uses Spotify to consume «online» music, although its use cannot be considered widespread amongst the old people who make up said groups.

4. Discussion and conclusions

The results of the study carried out show that the elderly are becoming more and more interested in the Internet and technological devices; and are beginning to make them part of their lives as they have discovered the possibilities they offer, which they explain in their discussions.

In the specific case of the Internet, which is the focus of this research, the results are in accordance with the ideas of Juncos, Pereiro & Facal (2006), who conclude that the Internet is a new window onto the world which facilitates communication and cognitive activity for the elderly, by contributing to their greater autonomy and satisfying their demand for «space and a social voice» (IMSERSO, 2013: 16). The elderly make use of quite a few opportunities offered by the web, particularly for information and communication; but they are also beginning, in their day-to-day life, to use other possibilities for administrative processes and entertainment.

The information options are the most utilized by the elderly and promote greater autonomy of knowledge, thus improving their well-being by contributing to the implementation of their skills, broadening their knowledge and increasing their self-esteem. As Miranda (2004) declares, in general, the elderly are interested in similar topics to those which interest most of the population, but they also consult information that is relevant to their time of life. Consequently, current affairs and health are the key focuses in their searches. However, the elderly are cautious and try to use trustworthy sources. The National Telecommunications and Information Society Observatory (ONTSI) (2012) identifies uncertainty on the reliability of information (54.4%) and the risk of misinterpretation of same (28.7%) as the two main obstacles in the search of healthcare information by older people.

In general, the communication opportunities offered by the web facilitate social interaction that integrates the elderly into relationships that strengthen their social qualities and keep them out of danger of isolation; these effects favor their motivation and satisfaction. The elderly use the web to communicate by means of email and other types of «online» interaction which are adapted to mobility, such as WhatsApp or Facebook. In this sense, the communication facilities offered by the Internet contribute to their social integration with peer groups and with their family members, which is essential to guarantee active ageing (Agudo, Pascual & Fombona, 2012).

As regards the transactional and administrative opportunities offered by the Internet, it may be concluded that they speed up the development of elderly people’s everyday activities, involving them in a more dynamic environment. In addition, the Internet allows them to carry out actions that some of them would not be able to do because of physical impediments, thus contributing to their greater independence. Although Agudo, Pascual & Fombona (2012: 199) suggested that administrative processes were not very common amongst the elderly, this tendency is undergoing change.

Finally, the elderly define the potential for entertainment and leisure offered by the Internet as a playmate that contributes to their physical and psychosocial well-being (Blat, Arcos & Sayago, 2012). From this perspective, the Internet opens the doors to autotelic leisure in its ludic and creative dimensions (Cuenca, 1995), «in which freedom of choice, of expression and the development of non-utilitarian tasks prevail» (Goytia & Lázaro, 2007: 5). These possibilities, however, are not the most appreciated by the elderly, although they improve their cognitive activity and facilitate a positive attitude which strengthens their self-esteem. Therefore, it can be concluded that the Internet is a source of opportunities for active ageing, as it has possibilities that optimize the quality of life of many different types of elderly people in its psychological dimension and also from a holistic perspective.

Among the limitations of the research we must mention that, although the methodology permits us to achieve the main objectives, allowing for a thorough and direct explanation of the establishment of the Internet as a source of opportunities for active ageing, some interesting questions demand additional treatment, as they are proposed as a first approach and require further in-depth study.

Thanks to our varied sample, we have found that elderly people with different levels of education and cognitive capacities «actively demand and make the most of learning from new technologies» (Requena, Pastrana & Salto, 2012: 17). For this reason, the encouragement of digital literacy amongst the elderly is of capital importance. They themselves demand training to facilitate this learning, and more accessible tools, as they are aware of the great opportunities offered by the web. Fernández-Campomanes & Fueyo (2014) consider that these training programs should be developed taking into account gender factors which will promote the participation of women in society from an empowering and not merely instrumental perspective. Regardless of gender, according to Macías-González & Manresa (2013), those older people who have had prior contact with ICT feel greater motivation to learn more about the subject and see these technologies as a helpful tool. Whatever the case, one of the main objectives which should be considered in this digital literacy program is to offer the elderly «a full and more participative life» in which ICT would be instruments that foster their civic participation (Abad, 2014: 179).

In a changing and technologically advanced world, lifelong learning is fundamental to avoid exclusion and to guarantee adaptation to the norm (Jiménez, 2011). This fact offers an interesting field for reflection for civic and institutional leaders, who should sponsor the development of policies to facilitate access to ICT and proper use by the collective studied. Such policies are what will promote and consolidate a change in our way of understanding and perceiving ageing, as a response to the legitimate rights of participation of the elderly. Hence, it is essential to optimize «e-inclusion» programs and to support the development of methodologies that will bring the Internet closer to older people by offering them training in skills which will allow them to exploit the potential offered by the Internet for active ageing to which this work has referred.

Notes

1 Profiles classified following the European Socio-economic Classification (http://goo.gl/krmKrL).

Support and acknowledgement

Research carried out within the project funded by Universidad CEU San Pablo: «Digital Communications in Healthcare Institutions for Active Aging», reference USPBS-PPC03/2012.

References

Abad, L. (2014). Diseño de programas de e-inclusión para alfabetización mediática de personas mayores. Comunicar, 42, 173-180. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C42-2014-17

Agudo, S., Fombona, J., & Pascual, M.A. (2013). Ventajas de la incorporación de las TIC en el envejecimiento. Relatec, 12(2), 131-142. (http://goo.gl/mF7RHa) (14-10-2014).

Agudo, S., Pascual, M.A., & Fombona, J. (2012). Usos de las herramientas digitales entre las personas mayores. Comunicar, 39, 193-201. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C39-2012-03-10

Ala-Mutka, K., Malanowski, N., Punie, Y., & Cabrera, M. (2008). Active Ageing and the Potential of ICT for Learning. Institute for Prospective Technological Studies (IPTS). Joint Research Centre (JRC), European Communities. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2791/33182 (http://goo.gl/MaalFD) (17-10-2014).

Aldana, G., García-Gómez, L., & Jacobo, A. (2012). Las tecnologías de la información y Comunicación (TIC) como alternativa para la estimulación de los procesos cognitivos en la vejez. CPU-e, 14, 153-166. (http://goo.gl/zFauoe) (21-09-2014).

Aunión, J.A. (2014). No hay niños para el parque. El País, 06-07-2014. (http://goo.gl/b7uhm0) (14-10-2014).

Blat, J., Arcos, J.L., & Sayago, S. (2012). WorthPlay: Juegos digitales para un envejecimiento activo y saludable. Lychonos, 8, 16-21. (http://goo.gl/RYGqS9) (30-05-2014).

Bubbolini, G. (2014). ICT for Social Inclusion: Big (Social) Gains Ahead! Digital Agenda for Europe, 15-10-2014. (http://goo.gl/bkGx05) (17-10-2014).

Cuenca, M. (1995). Temas de pedagogía del ocio. Bilbao: Universidad de Deusto.

Del-Arco, J., & San-Segundo, J.M. (2011). Los mayores ante las TIC: Accesibilidad y asequibilidad. Madrid: Fundación Vodafone España. (http://goo.gl/mwj6AO) (23-05-2014).

Dirección General de Empleo, Asuntos Sociales e Inclusión (2012). La aportación de la UE al envejecimiento activo y a la solidaridad entre las generaciones. (http://goo.gl/XVMci6) (20-01-2015).

Elosua, P. (2010). Valores subjetivos de las dimensiones de calidad de vida en adultos mayores. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, 45(2), 67-71. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.regg.2009.10.008

European Commission (2005). i2010-A European Information Society for Growth and Employment. COM (2005) 229 Final. (http://goo.gl/8eKkeB) (20-05-2014).

European Commission (2006). ICT for an Inclusive Society. Ministerial Declaration of the Ministerial Conference in Riga. (http://goo.gl/MOXT1Q) (10-10-2014).

European Commission (2007). European i2010 Initiative on e-Inclusion «To be Part of the Information Society». COM (2007) 694 Final. (http://goo.gl/c5BTvM) (18-04-2014).

Fernández-Ballesteros, R., Zamarrón, M.D., & al. (2010). Envejecimiento con éxito: Criterios y predictores. Psicothema, 22(4), 641-647. (http://goo.gl/hZq1eQ) (14-05-2014).

Fernández-Campomanes, M., & Fueyo, A. (2014). Redes sociales y mujeres mayores: Estudio sobre la influencia de las redes sociales en la calidad de vida. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 5(1), 157-177. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2014.5.1.11

Fernández-García, A. (2011). Las personas mayores ante las tecnologías de información y comunicación. Revista 60 y más, 300, 8-13. (http://goo.gl/DQDjhm) (18-05-2014).

Fundación Vodafone (2012). TIC y mayores conectados al futuro. Resumen ejecutivo. (http://goo.gl/qybxae) (21-10-2014).

Gil, J., García, E., & Rodríguez, G. (1994). El análisis de los datos obtenidos en la investigación mediante grupos de discusión. Enseñanza, XII, 183-199. (http://goo.gl/HktjWP) (22-01-2015).

Gilhooly, M.L.M., Gilhooly, K.J., & Jones, R.B. (2009). Quality of Life: Conceptual Challenges in Exploring the Role of ICT in Active Ageing. In M. Cabrera, & N. Malanowski (Eds.), Information and Communication Technologies for Active Ageing: Opportunities and Challenges for the European Union. (pp. 49-76). Amsterdam: IOS Press. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/978-1-58603-937-0-49

Goytia, A., & Lázaro, Y. (Coords.) (2007). La experiencia de ocio y su relación con el envejecimiento activo. Bilbao: Instituto de Estudios de Ocio, Universidad de Deusto. (http://goo.gl/knYQ6y) (12-06-2014).

IMSERSO (2013). Envejecimiento activo. Libro Blanco. (http://goo.gl/LSJjP7) (10-04-2014).

Jiménez, J.A. (2011). Educación en nuevas tecnologías y envejecimiento activo. Segovia: Congreso Internacional Educación Mediática y Competencia Digital. (http://goo.gl/nKU3GB) (10-04-2014).

Juncos, O., Pereiro, A.X., & Facal, D. (2006). Lenguaje y comunicación. In C. Triadó, & F. Villar (Coords.), Psicología de la vejez (pp.169-189). Madrid: Alianza.

Macías-González, L., & Manresa, C. (2013). Mayores y nuevas tecnologías: Motivaciones y dificultades. Ariadna, I(1), 7-11. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.6035/Ariadna.2013.1.2

Malanowski, N., Özcivelek, R., & Cabrera, M. (2008). Active Ageing and Independent Living Services: The Role of Information and Communication Technology. Seville: Institute for Prospective Technological Studies (IPTS), Joint Research Centre (JRC), European Communities. (http://goo.gl/k2P7bY) (04-10-2014).

Martínez-Rodríguez, T., Díaz-Pérez, B., & Sánchez-Caballero, C. (Coords.) (2006). Los centros sociales de personas mayores como espacios de promoción del envejecimiento activo y la participación social. Oviedo: Consejería de Vivienda y Bienestar Social, Gobierno del Principado de Asturias.

Miranda, R. (Ed.) (2004). Los mayores en la sociedad de la información: Situación actual y retos de futuro. Madrid: Fundación AUNA. (http://goo.gl/AFceAq) (18-09-2014).

Nussbaum, J.F., & Coupland, J. (Eds.) (2008). Handbook of Communication and Aging Research. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

OMS (2001). El abrazo mundial. Campaña de la OMS por un envejecimiento activo. (http://goo.gl/1qgEBp) (12-03-2014).

OMS (2002). Envejecimiento activo: Un marco político. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, 37(S2), 74-105. (http://goo.gl/9xUBRE) (14-10-2014).

ONTSI (2012). Los ciudadanos ante la e-sanidad. (http://goo.gl/EnTeh) (14-06-2014).

ONU (2003). Declaración de principios de la Cumbre Mundial sobre la Sociedad de la Información. Construir la sociedad de la información: Un desafío mundial para el nuevo milenio. (http://goo.gl/iVXMTy) (12-03-2014).

Parapar, C., Fernández-Nuevo, J.L., Rey, J., & Ruiz-Yaniz, M. (2010). Informe de la I+D+i sobre Envejecimiento. Madrid: Fundación General CSIC. (http://goo.gl/PQwwDx) (22-01-2015).

Querol, V.A. (2012). Mayores y ciberespacio: Procesos de inclusión y exclusión. Barcelona: UOC.

Requena, C., Pastrana, I., & Salto, F. (2012). Multiplicadores de nuevas tecnologías. In Universidad de León, & Telefónica (Eds.), Cuadernos de la Cátedra Telefónica (Eds.), TIC y envejecimiento de la sociedad. (pp. 15-26). León: Universidad de León y Telefónica. (http://goo.gl/eiP4P5) (22-01-2015).

Rowe, J.W., & Khan, R.L. (1987). Human Aging: Usual and Successful. Science, 237(4811), 143-149. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.3299702

Rowe, J.W., & Khan, R.L. (1997). Successful Aging. The Gerontologist, 37(4), 433-440. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/37.4.433

Shepherd, C.E., & Aagard, S. (2011). Journal Writing with Web 2.0 Tools: A Vision for Older Adults. Educational Gerontology, 37(7), 606-620. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03601271003716119

Tirado, R., Hernando, A., García-Ruiz, R., Santibáñez, J., & Marín-Gutiérrez, I. (2012). La competencia mediática en personas mayores. Propuesta de un instrumento de evaluación. Icono14, 10(3), 134-158. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v10i3.211

TNS Opinion, & Social (2012). Active Aging. Special Eurobarometer 378, Wave EB76.2. Brussels: European Commission. (http://goo.gl/pn8A8D) (20-01-2015).

Unión Europea (2011). Año Europeo del Envejecimiento Activo y la Solidaridad Intergeneracional (2012). (http://goo.gl/jVmHHo) (15-04-2014).

Walker, A. (2009). Active Ageing in Europe: Policy Discourses and Initiatives. In M. Cabrera, & N. Malanowski (Eds.), Information and Communication Technologies for Active Ageing: Opportunities and Challenges for the Europe Union. (pp. 35-48). Amsterdam: IOS Press. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/978-1-58603-937-0-35

WHO (2002). Active Ageing: A Policy Framework. Geneva: World Health Organization. (http://goo.gl/67HVLL) (18-10-2014).

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El progresivo envejecimiento de las sociedades ha llevado a los organismos internacionales y europeos a desarrollar programas de envejecimiento activo, capaces de construir una nueva cultura sobre el papel de las personas mayores en la sociedad. Estos incluyen aspectos sociales de carácter comunicacional que, sin embargo, han tenido menos desarrollo investigador que otros más apremiantes, vinculados a aspectos físicos y económicos. Esta investigación atiende precisamente a estas variables comunicacionales, abordando la vinculación de los mayores con Internet y planteándose dos objetivos principales: Conocer las utilidades que tiene Internet para este colectivo y explicar los motivos que convertirían a este medio en una fuente de oportunidades para un envejecimiento activo. Para satisfacerlos, se utiliza una metodología cualitativa que se apoya en el desarrollo de tres grupos de discusión constituidos por entre cinco y seis personas de 56 a 81 años y moderados por un experto. Los resultados obtenidos del análisis cualitativo del contenido en cada discusión indican que Internet es una fuente de oportunidades para los mayores, que pueden aglutinarse en cuatro categorías: informativas, comunicativas, transaccionales y administrativas, y de ocio y entretenimiento. Estas oportunidades optimizan la calidad de vida de los mayores y contribuyen a su envejecimiento activo, si bien, su máximo aprovechamiento precisa de programas de «e-Inclusion» y metodologías que aproximen Internet a los mayores, facilitándoles una formación en competencias digitales.

1. Introducción y estado de la cuestión

Según uno de los últimos informes de la ONU (2014), en 2050, España se convertirá en el tercer país más «viejo» del mundo, con un 34,5% de su población por encima de 65 años (Aunión, 2014). El Eurobarómetro de 2012 manifiesta que el concepto de persona mayor es muy distinto entre los países de la Unión Europea, pero como media, se considera «mayores» a las personas de más de 63,9 años (TNS Opinion & Social, 2012). Ante este envejecimiento progresivo de la población, «el reto del siglo XXI es asegurar una calidad de vida óptima para las personas de edad y retrasar la aparición de discapacidades propias de la edad» (OMS, 2001: 3). Así, durante la década de 1980, la Unión Europea empieza a desarrollar una nueva política de envejecimiento que supone una transición desde una actitud pasiva a una orientación más proactiva entre las personas mayores. Este nuevo enfoque permite un mayor bienestar entre los mayores y contribuye a la sostenibilidad económica de los sistemas sociales de la Unión Europea, por lo que unifica los intereses de todos los actores (ciudadanos, ONG, empresas y responsables políticos) (Walker, 2009).

El envejecimiento activo fue definido por la OMS (2002: 79) como «el proceso de optimización de las oportunidades de salud, participación y seguridad con el fin de mejorar la calidad de vida a medida que las personas envejecen». Este concepto aparece vinculado tanto al bienestar físico, como al social y al mental, lo que implica también la participación e integración de las personas mayores en la sociedad (WHO, 2002; OMS, 2002).

Desde una perspectiva psicológica, el trabajo de Fernández-Ballesteros y otros (2010) muestra los criterios y predictores de lo que denominan «envejecimiento con éxito», que emerge de las tres variantes en las que Rowe y Khan (1987; 1997) sintetizaron las posibilidades de envejecimiento: «Usual», «patológico» y «con éxito». En este estudio, basado en el ESAP (European Survey on Aging Protocol) y su versión PELEA (Protocolo del Estudio Longitudinal sobre Envejecimiento Activo), se identifica el funcionamiento social y participativo como uno de los dominios del «envejecimiento con éxito», punto sobre el que se articula este trabajo y que menos interés investigador ha suscitado en beneficio de otros aspectos más urgentes vinculados a la salud o la economía.

La Unión Europea (2011) declaró el año 2012 como el «Año Europeo del Envejecimiento Activo y de la Solidaridad Intergeneracional» para combatir el efecto del envejecimiento demográfico sobre los modelos sociales de los Estados miembros y promover la creación de una cultura del envejecimiento activo como un proceso permanente en una sociedad multiedad.

Desde la década de 1990, la Comisión Europea ha desarrollado programas orientados a afrontar este nuevo reto, procurando iniciativas que lleven a mayores niveles de independencia e integración en el colectivo de los mayores. En tales programas, la comunicación se ha considerado un elemento clave para el desarrollo de un envejecimiento activo. Sin embargo, pese a su importancia, Nussbaum y Coupland (2008) consideran que todavía la comunicación no constituye un eje central en estos estudios.

No obstante, es innegable que las TIC pueden ofrecer nuevas oportunidades a los mayores. Por ello, el Informe de la I+D+i sobre envejecimiento subraya la necesidad de impulsar investigaciones sobre aspectos tecnológicos para combatir los efectos del envejecimiento humano (Parapar & al., 2010).

Se ha demostrado que es especialmente en la vejez donde las TIC ofrecen relevantes oportunidades para la mejora de procesos psicológicos (Aldana, García-Gómez & Jacobo, 2012; Elosua, 2010), aspectos sociales (Martínez-Rodríguez, Díaz-Pérez & Sánchez-Caballero, 2006) y cuestiones particularmente relacionadas con la dependencia (Del-Arco & San-Segundo, 2011; Malanowski, Özcivelek & Cabrera, 2008). Ala-Mutka y otros (2008) sugieren diversas políticas con un enfoque holístico para mejorar la calidad de vida de las personas mayores a través de un proceso de formación permanente, basado en las TIC y en el que es esencial la implicación de las instituciones y de las generaciones más jóvenes. Además, parece esencial que tales metodologías incluyan también instrumentos para la evaluación de las competencias mediáticas de los mayores (Tirado & al., 2012). No obstante, parece complicado determinar con certeza si las TIC pueden mejorar la calidad de vida de los mayores, pues median tres variables que resultan determinantes en la medición de tal impacto: La riqueza, la salud y las relaciones sociales (Gilhooly, Gilhooly & Jones, 2009).

En este contexto, Internet emerge como un gran apoyo para un envejecimiento activo y debe considerarse en el desarrollo de estas políticas en las actuales y futuras sociedades. Se prevé que el porcentaje de internautas mayores crezca en los próximos años, pero de manera presumiblemente lenta, por las dificultades de acceso que presenta este colectivo con una formación inferior a la secundaria (Fundación Vodafone, 2012). Pese a ello, la extensión general de la accesibilidad a la Red y la profusión de dispositivos que hacen posible un acceso en movilidad han facilitado nuevas formas de mejorar la calidad de vida. Pero las oportunidades innegables que ofrece Internet a otros colectivos más jóvenes parecen limitarse en el caso de las personas mayores. La brecha digital es más evidente entre estos grupos de las modernas sociedades. En este sentido, los mayores conforman un colectivo con riesgo de exclusión –o aislamiento– (Querol, 2012; Fernández-García, 2011) y las TIC pueden contrarrestarla, promoviendo la colaboración y el desarrollo de comunidades de aprendizaje que superen los límites físicos (Shepherd & Aagard, 2011) y ofreciéndoles una oportunidad de integración social y de orientación saludable (Agudo, Fombona & Pascual, 2013). Esta fractura entre jóvenes y mayores, generada por la discriminación en el acceso a las TIC, se ha convertido en uno de los grandes retos para la ONU y la Comisión Europea. Así, durante la «Cumbre Mundial de la Sociedad de la Información», realizada por la Unión Internacional de Telecomunicaciones de Naciones Unidas en Ginebra (2003) y en Túnez (2005), se declara un compromiso con aquellos colectivos que corren peligro de marginación (ONU, 2003). En la misma línea de preocupación, la Comisión Europea ha desarrollado varias iniciativas, entre las que destaca «i2010», que pretende fomentar la accesibilidad y lograr que todos los colectivos adquieran unas competencias digitales básicas (European Commission, 2005).

Un año después, la «e-inclusión» se plantea como elemento clave para conseguir una integración de las TIC y su uso en la vida de los individuos para garantizar su participación en la sociedad de la información, reducir la brecha digital y potenciar una mayor calidad de vida y cohesión social (European Commission, 2006). Las políticas de «e-inclusión» deben, pues, focalizarse en ayudar a los más excluidos a utilizar las TIC de forma productiva (European Commission, 2007). En este sentido, la Agenda Digital 2020 de la Unión Europea tiene por objeto aprovechar el potencial de las TIC «para satisfacer las necesidades de una población que envejece» y contribuir así a un envejecimiento activo (Dirección General de Empleo, Asuntos Sociales e Inclusión, 2012: 18). Actualmente, uno de los objetivos respecto al uso de las TIC para lograr una vida independiente entre los mayores es reducir sus necesidades de asistencia (Bubbolini, 2014).

Como se ha apuntado, pese a que estudios recientes demuestran que aspectos sociales, como los comunicacionales, se identifican como parte importante del envejecimiento activo, son los que menos desarrollo investigador han tenido en detrimento de otros más apremiantes. Esta investigación se focaliza precisamente en este tipo de variables comunicacionales atendiendo a dos objetivos esenciales:

a) Conocer las diversas utilidades que tiene Internet para las personas mayores.

b) Explicar los motivos que convertirían a este medio en una fuente de oportunidades para un envejecimiento activo.

2. Material y método

El diseño metodológico responde a una tipología cualitativa que permite resultados explicativos capaces de lograr los objetivos planteados. El grupo de discusión se plantea, en este caso, como el instrumento cualitativo más adecuado, ya que posibilita una mayor profundidad explicativa, lo que permitiría descubrir las posibles oportunidades de Internet.

De este modo, se ha diseñado un modelo capaz de recoger datos de primera mano sobre las experiencias de las personas mayores con Internet. Este diseño se apoya en tres grupos de discusión, guiados y moderados por un experto, y el posterior análisis cualitativo del contenido vertido en cada discusión.

Los integrantes de la muestra se escogen siguiendo los siguientes criterios: Participantes de ambos sexos que utilizan Internet, con una edad comprendida desde los 56 a los 81 años, de clase social media, con diversidad de formación, residentes en zonas urbanas de diferente envergadura y con manifiesto interés por una vida activa (todos están vinculados por el aprendizaje). De este modo, se logra una heterogeneidad suficiente para garantizar una mayor riqueza y variedad en las perspectivas vertidas.

El procedimiento seguido por los moderadores responde a la menor interferencia posible, ayudándose de un argumentario que recoge los grandes aspectos a tratar en el grupo, pero facilitando que los participantes expresen libremente los usos que hacen de Internet vinculados a una mejora de sus hábitos cotidianos y a una optimización de su calidad de vida.

La duración de cada grupo varía según la propia riqueza de su conversación, orientada pero no condicionada por el moderador, lo que explica que el grupo Z sea de menor duración.

Las discusiones de los grupos están grabadas y transcritas, lo que facilita un análisis cualitativo del contenido que ha permitido identificar aspectos relevantes entre las experiencias de los participantes y en relación a los objetivos planteados. El mencionado análisis se centra en el corpus de datos textuales resultante de la transcripción del discurso, con la descripción e interpretación de los mismos para, a posteriori, establecer las categorías de oportunidades que ofrece Internet para un envejecimiento activo. Esta taxonomía responde a un criterio temático según unidades de contenido que se han delimitado «considerando como unidades aquellos fragmentos que expresan una idea o se refieren a un tema» (Gil, García & Rodríguez, 1994: 192).

3. Resultados

Las experiencias narradas por los participantes en los tres grupos de discusión han manifestado algunas coincidencias en la consideración de Internet como una fuente de oportunidades para optimizar sus hábitos de vida y contribuir a su envejecimiento activo.

Los resultados más ricos se han obtenido a partir de las experiencias procedentes del grupo X y del grupo Y, siendo menos productiva la discusión del grupo Z. Estos datos se han clasificado en cuatro categorías de oportunidades, fruto de los consensos detectados en el análisis de los discursos. Como se ha explicado, su clasificación corresponde a un criterio temático que ha posibilitado su propia nomenclatura a posteriori. Además, se han incorporado citas aisladas de algunos participantes que, a modo de ejemplo clarificador, reflejan un consenso respecto a las oportunidades que les brinda Internet.

3.1. Oportunidades informativas

Internet emerge para las personas mayores como una magnífica oportunidad informativa. Es una gran enciclopedia, dinámica, cómoda y de fácil acceso, que permite encontrar información sobre múltiples temas: «Consulto mucho en Internet, cualquier cosa» (grupo X, 2014).

Google se posiciona como el único buscador usado por los participantes de los diferentes grupos y el recurso a través del cual acceder a otras páginas con información relevante para ellos. Sin embargo, reconocen no utilizar otro tipo de plataformas informativas como los blogs y los foros.

Los recurrentes temas de consulta que se han localizado en el análisis del discurso de los grupos se pueden clasificar en los siguientes campos:

a) Temas de actualidad: Este colectivo muestra especial interés por las noticias que afectan a los diferentes entornos en los que se mueven (provincia, pueblo, país) y algunos de ellos confiesan una predilección por la prensa digital frente a la tradicional.

b) Temas de salud: El interés sobre este tipo de información está muy extendido entre los participantes de todos los grupos de discusión. No obstante, siempre buscan información que les afecta de una forma más o menos directa: «Si a mí no me llega a pasar eso, no lo buscas en Google» (grupo Y, 2014). De forma general, rastrean datos sobre:

• Enfermedades. En este caso, siempre confían en el diagnóstico del profesional sanitario y, simplemente, se interesan por remedios naturales o por completar y/o aclarar la información que les ofrece el médico, pero siempre considerando que: «Nunca puede sustituir un Internet a un médico» (grupo Y, 2014).

• Médicos. Al respecto, buscan información sobre los profesionales que les van a tratar a ellos y/o a sus familiares y/o amigos.

• Hospitales. Se interesan por la calidad de los centros a los que acuden: «Siempre me he metido en informaciones sobre el hospital, sobre los premios que han ganado, las condecoraciones que les han dado, pues el caché que tiene el hospital» (grupo X, 2014).

• Dietas saludables. Encuentran en Internet una fuente de información sobre hábitos saludables, aunque consideran que suelen responder a tendencias.

c) Temas de cultura e interés general: Es frecuente que este grupo poblacional, especialmente el femenino, utilice la Red para buscar recetas de cocina. También es frecuente la búsqueda de información sobre curiosidades, por ejemplo: «Cuando hay alguna palabra que no te suena, la Wikipedia o un país. O sea, la información de la Wiki, es la leche» (grupo Y, 2014); incluso para resolver problemas puntuales de carácter técnico: «Pues cualquier pregunta que me surge o que desconozco, informaciones técnicas, cualquier cosa que haya» (grupo X, 2014). En relación a la cultura, también buscan información sobre exposiciones, viajes, libros, cine, teatro y otras actividades relacionadas con su ocio y entretenimiento.

Un aspecto importante que afecta a las oportunidades informativas que ofrece Internet, se refiere a la fiabilidad de los datos. Al respecto, los participantes se muestran precavidos: «No me creo todo lo que dicen […] Hay mucho pájaro» (grupo X, 2014). En este sentido, se dan cuenta de que Internet: «No es todo la panacea. Hay mucha basura también» (grupo Y, 2014). Por ello, recalcan la importancia de contrastar la información y buscarla en fuentes fidedignas. Además de la fiabilidad de la fuente que firma la información, existen otras variables que influyen en la percepción de una mayor o menor confianza en los datos, como el diseño y la apariencia de la «web» o el prestigio de mencionado soporte.

En lo que respecta particularmente a la información sobre salud, muestran especial cautela y desarrollan advertencias relacionadas con la moderación en el uso de Internet para el acceso a este tipo de datos, con el fin de no caer en la hipocondría: «Haces de tu vida una enfermedad» (grupo Z, 2014).

3.2. Oportunidades comunicativas

Dentro de las oportunidades comunicativas de Internet, la más utilizada por la mayoría de los participantes en la investigación, es el correo electrónico. Varios integrantes de los grupos consideran que los «smartphones» han facilitado las comunicaciones, favoreciendo la inmediatez en la conexión al correo electrónico o las redes sociales. El uso del ordenador lo reducen a interacciones personales a las que prefieren dedicar más tiempo, como las que establecen con familiares que viven fuera, apoyándose en plataformas como Skype: «El ordenador pues lo utilizo para Skype, si hablo con Manuela [su hija]» (grupo Y, 2014).

Además, la proliferación de los dispositivos móviles ha promovido, entre este colectivo, la oportunidad de comunicarse a través de redes sociales como WhatsApp y Facebook. Como ocurre en otros segmentos poblacionales, WhatsApp ha desplazado la comunicación telefónica tradicional: «WhatsApp, vamos, yo he dejado de hablar por teléfono» (grupo X, 2014). Por otro lado, Facebook se percibe como un medio de interacción con amigos y familiares, menos inmediato que WhatsApp, pero más ameno para muchos de los participantes, ya que les permite compartir experiencias: «Bueno, mis hijas me mandan la fotografía de mis nietos» (grupo Z, 2014). La pertenencia a esta red social viene determinada por un vínculo de amistad o de parentesco con otras personas que pertenecen a ella. Este hecho y la percepción de una pérdida de tiempo en atender a varios perfiles sociales son variables que determinan que no pertenezcan a otras redes como Twitter. En una perspectiva más negativa de las redes sociales, algunos miembros de los grupos prefieren no dedicarles tiempo: «Pero lo de Facebook, si quieres que te diga, a mí me parece mucho chafardeo» (grupo X, 2014).

En general, las oportunidades comunicativas que ofrece la Red facilitan una interacción social que integra a los mayores en relaciones que potencian sus cualidades sociales y les apartan del aislamiento; efectos que favorecen su motivación, autoestima y satisfacción. Asimismo, el aprovechamiento de tales oportunidades genera la admiración entre sus iguales: «A mí me da mucha alegría que por WhatsApp, con la persona que yo más mensajes mando es un señor de 93 años» (grupo X, 2014).

3.3. Oportunidades transaccionales y administrativas

Internet ha facilitado a las personas mayores ciertos hábitos cotidianos, gracias a las posibilidades que ofrece para realizar transacciones y trámites administrativos «online». Al respecto, Miranda (2004) manifiesta que estas operaciones son especialmente útiles para aquellas personas que tienen restricciones motivadas por problemas de salud. Así, los mayores pueden obtener grandes beneficios y comodidades aprovechando estas oportunidades.

Es habitual entre los participantes de los grupos, utilizar la Red para hacer la declaración de la renta o para gestionar facturas y cuentas bancarias: «Yo, por ejemplo, con las facturas de gas, teléfono y todo, todo, lo hago por Internet y el banco por Internet, menos sacar el dinero que no me lo dan» (grupo Z, 2014). Además, es frecuente su utilización para solicitar citas (para consulta médica o para trámites burocráticos), destacando su comodidad e inmediatez frente a otras formas de conseguirla, como acercarse al centro o llamar por teléfono.

En lo relativo a la compra «online», no se percibe un uso demasiado extendido, algunos lo utilizan para contratar viajes, comprar entradas de cine o teatro, etc. Únicamente un participante muestra su interés por la adquisición de productos «online»: «A mí me gusta mucho meterme en compra-ventas. Compro en el extranjero […] cosas que necesito que en España están más caras» (grupo X, 2014).

3.4. Oportunidades de ocio y entretenimiento

Además de facilitar información sobre ocio y entretenimiento, Internet ofrece posibilidades directas para su consumo, aunque son las oportunidades menos explotadas por este colectivo. Al respecto, algunos de los miembros de los grupos de discusión confiesan consumir programas de radio y televisión «online», generalmente, porque se han perdido su emisión en directo; es el consumo «online» de ocio más extendido entre los participantes en el estudio.

Un miembro de uno de los grupos dice: «Pues yo lo utilizo […] también para jugar a sudokus, la verdad, juego para agilizar un poco la mente» (grupo X, 2014). De este modo, muestra su interés por fomentar su actividad cognitiva.

Otro miembro de otro de los grupos confiesa que utiliza Spotify para consumir música «online», aunque su uso no puede considerarse extendido entre las persona mayores que conforman mencionados grupos.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

Los resultados del estudio realizado manifiestan que los mayores tienen cada vez mayor interés por Internet y los dispositivos tecnológicos y empiezan a integrarlos en sus vidas al descubrir las oportunidades que ofrecen, verbalizándolo explícitamente en sus discursos.

En el caso específico de Internet, que es en el que se focaliza esta investigación, los resultados se muestran acordes a las consideraciones de Juncos, Pereiro y Facal (2006), quienes concluyen que Internet es una nueva ventana al mundo que facilita la comunicación y la actividad cognitiva, contribuyendo a la mayor autonomía de los mayores y satisfaciendo su demanda de «espacio y voz social» (IMSERSO, 2013: 16). Las personas mayores explotan diversas oportunidades que ofrece la Red, especialmente las de carácter informativo y comunicativo, pero también comienzan a implementar, en su día a día, otras oportunidades relativas a los trámites administrativos y el entretenimiento.

Las oportunidades informativas son las más aprovechadas por las personas mayores y fomentan una mayor autonomía de conocimiento, beneficiando su bienestar, al contribuir a la implementación de sus habilidades, ampliar sus conocimientos e incrementar su autoestima. Como sentencia Miranda (2004), en general, los mayores muestran interés por temas similares a los que interesan a la mayoría de la población, pero también consultan información relevante para el momento de vida en el que se encuentran. Así, la actualidad y la salud emergen como ejes claves en sus búsquedas. Sin embargo, los mayores se muestran cautos, procurando utilizar fuentes fidedignas. El Observatorio Nacional de las Telecomunicaciones y la Sociedad de la Información (ONTSI) (2012) identifica la incertidumbre sobre la fiabilidad de la información (54,4%) y el riesgo a una mala interpretación de la misma (28,7%) como las dos barreras principales en la búsqueda de información sobre salud por parte de los mayores.

En general, las oportunidades comunicativas que ofrece la Red facilitan una interacción social que integra a los mayores en relaciones que potencian sus cualidades sociales y les apartan del aislamiento, efectos que favorecen su motivación y satisfacción. Los mayores utilizan la Red para comunicarse, utilizando el correo electrónico u otras formas de interacción «online» más adaptadas a la movilidad como WhatsApp o Facebook. En este sentido, las facilidades comunicativas que ofrece Internet contribuyen a su integración social con sus grupos de iguales y sus familiares, algo esencial para garantizar su envejecimiento activo (Agudo, Pascual & Fombona, 2012).

En lo que se refiere a las oportunidades transaccionales y administrativas que facilita Internet, puede concluirse que agilizan el desarrollo de actividades de la vida cotidiana de los mayores, involucrándolas en un ambiente más dinámico. Además, Internet les permite solventar acciones que algunos no podrían desarrollar por impedimento físico, contribuyendo a su mayor autonomía. Aunque Agudo, Pascual y Fombona (2012: 199) planteaban que los trámites administrativos eran poco habituales entre los mayores, es una tendencia que está cambiando.

Finalmente, las oportunidades de ocio y entretenimiento que facilita Internet, lo definen como un amigo de juego que contribuye a su bienestar físico y psicosocial (Blat, Arcos & Sayago, 2012). Desde este punto de vista, Internet abre las puertas a un «ocio autotélico» en su dimensión lúdica y creativa (Cuenca, 1995), «en el que reina la libertad de elección, de expresión y de realización de tareas no utilitarias» (Goytia & Lázaro, 2007: 5) Estas oportunidades, si bien, no son las más valoradas por las personas mayores de todas las que ofrece la Red, permiten mejorar su actividad cognitiva y facilitan una actitud positiva que potencia su autoestima. Por todo ello, se puede determinar que Internet es una fuente de oportunidades para un envejecimiento activo, al ofrecer oportunidades que optimizan la calidad de vida de muy diversos tipos de mayores en su dimensión psicológica y desde una perspectiva integradora.

Entre las limitaciones de la investigación es preciso mencionar que, si bien, la metodología permite alcanzar los objetivos principales, posibilitando una explicación profunda y directa de la constitución de Internet como una fuente de oportunidades para un envejecimiento activo, algunas cuestiones de interés precisarían un tratamiento complementario, al plantearse como una primera aproximación que requiere mayor profundidad.

Gracias a una muestra diversa, se ha detectado que mayores con diferentes niveles de formación y de capacidades cognitivas «demandan activamente y aprovechan el aprendizaje de nuevas tecnologías» (Requena, Pastrana & Salto, 2012: 17). Por ello, es de capital importancia fomentar la alfabetización digital de los mayores. Ellos mismos solicitan programas que faciliten tal aprendizaje y herramientas más accesibles, conscientes de las grandes oportunidades que brinda la Red. Fernández-Campomanes y Fueyo (2014) consideran que estos programas de formación deben elaborarse teniendo en cuenta aspectos de género que potencien la participación de las mujeres en la sociedad desde una perspectiva empoderadora y no únicamente instrumental. Independientemente del género, según Macías-González y Manresa (2013), las personas mayores que han tenido un contacto previo con las TIC sienten una motivación mayor por aprender cosas nuevas sobre la materia y ven en tales tecnologías una herramienta de ayuda. En cualquier caso, uno de los grandes objetivos que debe plantearse esta alfabetización digital es permitir a los mayores «una vida más plena y participativa» en la que las TIC sean instrumentos que fomenten su participación cívica (Abad, 2014: 179).

En una sociedad cambiante y tecnológicamente avanzada, la formación durante toda la vida es fundamental para evitar la exclusión y garantizar la adaptación al medio (Jiménez, 2011). Este hecho, plantea un interesante campo de reflexión a los responsables institucionales y cívicos, quienes deben apoyar el desarrollo de políticas que faciliten, al colectivo estudiado, el acceso a las TIC y su adecuado aprovechamiento. Tales políticas son las que pueden promover y consolidar un cambio en la manera de entender y percibir el envejecimiento, dando respuesta al legítimo derecho de participación de los mayores. Por tanto, es esencial optimizar los programas de «e-inclusión» y apoyar el desarrollo de metodologías que aproximen Internet a las personas mayores, facilitándoles una formación en competencias que les permita explotar las oportunidades que ofrece Internet para un envejecimiento activo y a las que se han hecho referencia en este trabajo.

Notas

1 Perfiles codificados según la Clasificación Socioeconómica Europea (http://goo.gl/krmKrL).

Apoyos y agradecimientos

Investigación realizada dentro del proyecto financiado por la Universidad CEU San Pablo: «Comunicación digital en las instituciones sanitarias para un envejecimiento activo», con referencia USPBS-PPC03/2012.

Referencias

Abad, L. (2014). Diseño de programas de e-inclusión para alfabetización mediática de personas mayores. Comunicar, 42, 173-180. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C42-2014-17

Agudo, S., Fombona, J., & Pascual, M.A. (2013). Ventajas de la incorporación de las TIC en el envejecimiento. Relatec, 12(2), 131-142. (http://goo.gl/mF7RHa) (14-10-2014).

Agudo, S., Pascual, M.A., & Fombona, J. (2012). Usos de las herramientas digitales entre las personas mayores. Comunicar, 39, 193-201. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C39-2012-03-10

Ala-Mutka, K., Malanowski, N., Punie, Y., & Cabrera, M. (2008). Active Ageing and the Potential of ICT for Learning. Institute for Prospective Technological Studies (IPTS). Joint Research Centre (JRC), European Communities. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2791/33182 (http://goo.gl/MaalFD) (17-10-2014).

Aldana, G., García-Gómez, L., & Jacobo, A. (2012). Las tecnologías de la información y Comunicación (TIC) como alternativa para la estimulación de los procesos cognitivos en la vejez. CPU-e, 14, 153-166. (http://goo.gl/zFauoe) (21-09-2014).

Aunión, J.A. (2014). No hay niños para el parque. El País, 06-07-2014. (http://goo.gl/b7uhm0) (14-10-2014).

Blat, J., Arcos, J.L., & Sayago, S. (2012). WorthPlay: Juegos digitales para un envejecimiento activo y saludable. Lychonos, 8, 16-21. (http://goo.gl/RYGqS9) (30-05-2014).

Bubbolini, G. (2014). ICT for Social Inclusion: Big (Social) Gains Ahead! Digital Agenda for Europe, 15-10-2014. (http://goo.gl/bkGx05) (17-10-2014).

Cuenca, M. (1995). Temas de pedagogía del ocio. Bilbao: Universidad de Deusto.

Del-Arco, J., & San-Segundo, J.M. (2011). Los mayores ante las TIC: Accesibilidad y asequibilidad. Madrid: Fundación Vodafone España. (http://goo.gl/mwj6AO) (23-05-2014).

Dirección General de Empleo, Asuntos Sociales e Inclusión (2012). La aportación de la UE al envejecimiento activo y a la solidaridad entre las generaciones. (http://goo.gl/XVMci6) (20-01-2015).

Elosua, P. (2010). Valores subjetivos de las dimensiones de calidad de vida en adultos mayores. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, 45(2), 67-71. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.regg.2009.10.008

European Commission (2005). i2010-A European Information Society for Growth and Employment. COM (2005) 229 Final. (http://goo.gl/8eKkeB) (20-05-2014).

European Commission (2006). ICT for an Inclusive Society. Ministerial Declaration of the Ministerial Conference in Riga. (http://goo.gl/MOXT1Q) (10-10-2014).

European Commission (2007). European i2010 Initiative on e-Inclusion «To be Part of the Information Society». COM (2007) 694 Final. (http://goo.gl/c5BTvM) (18-04-2014).

Fernández-Ballesteros, R., Zamarrón, M.D., & al. (2010). Envejecimiento con éxito: Criterios y predictores. Psicothema, 22(4), 641-647. (http://goo.gl/hZq1eQ) (14-05-2014).

Fernández-Campomanes, M., & Fueyo, A. (2014). Redes sociales y mujeres mayores: Estudio sobre la influencia de las redes sociales en la calidad de vida. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 5(1), 157-177. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2014.5.1.11

Fernández-García, A. (2011). Las personas mayores ante las tecnologías de información y comunicación. Revista 60 y más, 300, 8-13. (http://goo.gl/DQDjhm) (18-05-2014).

Fundación Vodafone (2012). TIC y mayores conectados al futuro. Resumen ejecutivo. (http://goo.gl/qybxae) (21-10-2014).

Gil, J., García, E., & Rodríguez, G. (1994). El análisis de los datos obtenidos en la investigación mediante grupos de discusión. Enseñanza, XII, 183-199. (http://goo.gl/HktjWP) (22-01-2015).

Gilhooly, M.L.M., Gilhooly, K.J., & Jones, R.B. (2009). Quality of Life: Conceptual Challenges in Exploring the Role of ICT in Active Ageing. In M. Cabrera, & N. Malanowski (Eds.), Information and Communication Technologies for Active Ageing: Opportunities and Challenges for the European Union. (pp. 49-76). Amsterdam: IOS Press. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/978-1-58603-937-0-49

Goytia, A., & Lázaro, Y. (Coords.) (2007). La experiencia de ocio y su relación con el envejecimiento activo. Bilbao: Instituto de Estudios de Ocio, Universidad de Deusto. (http://goo.gl/knYQ6y) (12-06-2014).

IMSERSO (2013). Envejecimiento activo. Libro Blanco. (http://goo.gl/LSJjP7) (10-04-2014).

Jiménez, J.A. (2011). Educación en nuevas tecnologías y envejecimiento activo. Segovia: Congreso Internacional Educación Mediática y Competencia Digital. (http://goo.gl/nKU3GB) (10-04-2014).

Juncos, O., Pereiro, A.X., & Facal, D. (2006). Lenguaje y comunicación. In C. Triadó, & F. Villar (Coords.), Psicología de la vejez (pp.169-189). Madrid: Alianza.

Macías-González, L., & Manresa, C. (2013). Mayores y nuevas tecnologías: Motivaciones y dificultades. Ariadna, I(1), 7-11. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.6035/Ariadna.2013.1.2

Malanowski, N., Özcivelek, R., & Cabrera, M. (2008). Active Ageing and Independent Living Services: The Role of Information and Communication Technology. Seville: Institute for Prospective Technological Studies (IPTS), Joint Research Centre (JRC), European Communities. (http://goo.gl/k2P7bY) (04-10-2014).

Martínez-Rodríguez, T., Díaz-Pérez, B., & Sánchez-Caballero, C. (Coords.) (2006). Los centros sociales de personas mayores como espacios de promoción del envejecimiento activo y la participación social. Oviedo: Consejería de Vivienda y Bienestar Social, Gobierno del Principado de Asturias.

Miranda, R. (Ed.) (2004). Los mayores en la sociedad de la información: Situación actual y retos de futuro. Madrid: Fundación AUNA. (http://goo.gl/AFceAq) (18-09-2014).

Nussbaum, J.F., & Coupland, J. (Eds.) (2008). Handbook of Communication and Aging Research. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

OMS (2001). El abrazo mundial. Campaña de la OMS por un envejecimiento activo. (http://goo.gl/1qgEBp) (12-03-2014).

OMS (2002). Envejecimiento activo: Un marco político. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, 37(S2), 74-105. (http://goo.gl/9xUBRE) (14-10-2014).

ONTSI (2012). Los ciudadanos ante la e-sanidad. (http://goo.gl/EnTeh) (14-06-2014).

ONU (2003). Declaración de principios de la Cumbre Mundial sobre la Sociedad de la Información. Construir la sociedad de la información: Un desafío mundial para el nuevo milenio. (http://goo.gl/iVXMTy) (12-03-2014).

Parapar, C., Fernández-Nuevo, J.L., Rey, J., & Ruiz-Yaniz, M. (2010). Informe de la I+D+i sobre Envejecimiento. Madrid: Fundación General CSIC. (http://goo.gl/PQwwDx) (22-01-2015).

Querol, V.A. (2012). Mayores y ciberespacio: Procesos de inclusión y exclusión. Barcelona: UOC.

Requena, C., Pastrana, I., & Salto, F. (2012). Multiplicadores de nuevas tecnologías. In Universidad de León, & Telefónica (Eds.), Cuadernos de la Cátedra Telefónica (Eds.), TIC y envejecimiento de la sociedad. (pp. 15-26). León: Universidad de León y Telefónica. (http://goo.gl/eiP4P5) (22-01-2015).

Rowe, J.W., & Khan, R.L. (1987). Human Aging: Usual and Successful. Science, 237(4811), 143-149. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.3299702

Rowe, J.W., & Khan, R.L. (1997). Successful Aging. The Gerontologist, 37(4), 433-440. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/37.4.433

Shepherd, C.E., & Aagard, S. (2011). Journal Writing with Web 2.0 Tools: A Vision for Older Adults. Educational Gerontology, 37(7), 606-620. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03601271003716119

Tirado, R., Hernando, A., García-Ruiz, R., Santibáñez, J., & Marín-Gutiérrez, I. (2012). La competencia mediática en personas mayores. Propuesta de un instrumento de evaluación. Icono14, 10(3), 134-158. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v10i3.211

TNS Opinion, & Social (2012). Active Aging. Special Eurobarometer 378, Wave EB76.2. Brussels: European Commission. (http://goo.gl/pn8A8D) (20-01-2015).

Unión Europea (2011). Año Europeo del Envejecimiento Activo y la Solidaridad Intergeneracional (2012). (http://goo.gl/jVmHHo) (15-04-2014).

Walker, A. (2009). Active Ageing in Europe: Policy Discourses and Initiatives. In M. Cabrera, & N. Malanowski (Eds.), Information and Communication Technologies for Active Ageing: Opportunities and Challenges for the Europe Union. (pp. 35-48). Amsterdam: IOS Press. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/978-1-58603-937-0-35

WHO (2002). Active Ageing: A Policy Framework. Geneva: World Health Organization. (http://goo.gl/67HVLL) (18-10-2014).

Document information

Published on 30/06/15

Accepted on 30/06/15

Submitted on 30/06/15

Volume 23, Issue 2, 2015

DOI: 10.3916/C45-2015-03

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?