Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Resumen

Today's learning ecologies stand out due to their variety, dynamism and mutability, demanding an observation that matches them. This paper focuses on emerging youth informal learning cultures, with the main objective of recognizing and characterizing a new figure in online social media : the studygrammer. Using questionnaires (N=256), discussion groups organized using Philips 66 (N=56) and Atlas.ti (thematic analysis), as well as participant observation, we analyzed: practices of academic use of social networks by Communication students outside the institutional environment, the opinion about the #Studygram community, and the analysis of profiles. The main results are centered on a proposed definition of the studygrammer: namely the student who works as a mentor and peer leader in Instagram's academic field. This profile not only shares notes (which stand out for their neatness and detailed aesthetics), but also conveys advice, support and experiences. In fact, studygrammers keep influencer genetics by prioritizing aesthetics and monetization in their publications. The conclusion is that the academic purpose adds exclusive characteristics to the community, where the visual code functions as a lingua franca between fields of study. In fact, studygrammers have followers from various academic backgrounds who seek "know-how" (management and planning of their own learning) as well as a fundamentally rational adherence.

Resumen

Las actuales ecologías de aprendizaje destacan por su variedad, dinamismo y mutabilidad, lo que requiere una observación análoga de las mismas. Este trabajo se centra en las culturas de aprendizaje informal juvenil emergentes, tomando como objetivo principal reconocer y caracterizar una nueva figura en medios sociales en línea: el estudigramer. Empleando cuestionarios (N=256), grupos de discusión organizados mediante Philips 66 (N=56) y Atlas.ti (análisis temático), y observación participante, se analizan: prácticas de uso académico en redes sociales por parte de estudiantes de Comunicación al margen del entorno institucional, la opinión sobre la comunidad #Studigram, y el análisis de perfiles. Los principales resultados se concentran en una propuesta de definición del estudigramer: véase aquel estudiante que ejerce la labor de mentor y líder entre pares del ámbito académico en Instagram. Este perfil no solo comparte apuntes (que sobresalen por su orden y detallada estética), sino que también transmite consejos, apoyo y experiencias. De hecho, el estudigramer mantiene la genética influencer al priorizar la estética y monetización en sus publicaciones. Se concluye que el fin académico añade características exclusivas a la comunidad, donde el código visual funciona como lengua franca entre ámbitos de estudio. En efecto, los estudigramers cuentan con seguidores de diversos grados académicos que buscan el «saber hacer» (gestión y planificación del aprendizaje), así como una adhesión fundamentalmente racional.

Keywords

Studygrammer, Instagram, influencer, informal learning, social media, learning communities, communication students, transmedia literacy

Palabras clave

Estudigramer, Instagram, influencer, aprendizaje informal, redes sociales, comunidades de aprendizaje, estudiantes de comunicación, alfabetización transmedia

Introduction

After an extensive decade of usage and exploration of social networks fluctuating between panacea and apocalypse (Piscitelli, Adaime, & Binder, 2010), the maturity of their life cycle (IAB, 2018) invites a more pondered reading of their possible effects (Allcott & al., 2019). The scientific literature records both negative consequences, normally associated with intensive uses such as: personal discomfort and depression, digital addiction, distancing from healthy activities and physical personal relationships, increased consumption of biased information and political polarization (Mosquera& al.,2019); and positive consequences: obtaining information and entertainment, evading isolation, fostering relationships and social participation (Valkenburg& Peter, 2007). While the concerns are well-founded and legitimate, these authors suggest preventing the negative from obscuring the positive (Allcott & al., 2019).

The need of individuals to relate to the group as an anchor for a sense of belonging, and the creation of group and individual identity, which is also forged in relation to the group (Fisher, 1992), is characteristic of human beings. Social networks play a great role in this sense, since they have the power to exert influence from the dawn of their existence (Castells, 2001). In this way, relationship and influence are considered outstanding ingredients in the concept of community.

These online platforms can connect people with common interests, although this is certainly not new. Fans have always gathered around their affinities, but, in this case, with the peculiarity provided by the Network to replace a physical space by a virtual one. This enables associations to stick to the subject that concerns them jointly and, once the common objective has been achieved (or not), the link is dissolved, since "there are no membership cards or membership fees, only common concerns" (Bajo, 2015: 114). An example of this are the various changes that took place in this century under the umbrella of technopolitics (Castells, 2009; Candon-Mena, 2013) led by the so-called "smart mobs" (Rheingold, 2004).

The growth of participative culture on the Web (Jenkins, 2009) also reaches the didactic field. Thus, "transmedia literacy" (Scolari, 2016) implies a new relationship between subjects, ICT and educational institutions that doubly affects the youth population. On the one hand, this group is in full formative development, and on the other, it is openly exposed to media and technology. However, it is important to maintain a watchful function from the research community, the home and the school, given that a longer screen time "does not guarantee the development of a reflective attitude nor does it favor learning" (Caldeiro-Pedreira & Aguaded, 2017: 102). It is for this reason that adolescents are invited to demand "the ability to reflect in order to achieve audiovisual autonomy" and to "develop a critical view that allows them to survive in a digitalized world" (Caldeiro-Pedreira & Aguaded, 2017: 102).

State of the art

The greatest contribution of the Internet and ICTs to the field of education has been the promotion of teacher innovation. The logic and dynamics of digital technology itself have become natural allies of the new teaching model based on collaborative, autonomous and decentralized work. The scientific framework related to the positive effects of the introduction of technology in learning processes covers all types of scenarios, skills and procedures.

Experiences in the formal environment report advances in terms of methodologies such as flipped learning, which relies on the use of digital resources inside and outside the classroom (Serrano & Casanova, 2018), the usefulness of Personal Learning Environments (PLE) and gamification (Torres-Toukoumidis, Romero-Rodriguez & Pérez-Rodriguez,2018), from which an increased acquisition of skills is identified (Callaghan & Bower, 2012; López-Pérez, Pérez-López, & Rodríguez-Ariza, 2011).

The empirical verification of these experiences includes both formal and informal processes. Pereira, Fillol and Moura (2019) state that, despite the excessively institutionalized view of education, informal learning strategies contribute to the development of useful skills and competences from a school viewpoint. In fact, the skills acquired through the use of information technologies go beyond the cognitive realm to also cover the social and emotional realm (Tan& Pierce, 2011). Simply, the cross-sectional nature, ubiquity and versatility of virtual space makes it more "friendly" for young people, who also take advantage of it to learn without establishing differences.

The unlimited digital space does not respond to the stagnant logic of the pre-digital world, since "unlike other environments exclusively dedicated to learning (...) the opportunity for interactivity offered by social networks configures a completely hybrid space where it is not possible to distinguish when young people are sharing and when they are learning" (Arriaga, Marcellan-Baraze, & González-Vida, 2016: 213).

The existential journey of social networks also enables us to observe an evolution in their uses. Although in the beginning, a predominance of entertainment was detected, there has been an increase in their use for professional purposes since 2015 (Fundación Telefónica, 2016). Recently, the Internet Oxford Institute has detected a decrease in their use to stay informed in favor of the consumption of news via traditional media (Marchal, 2019). Piscitelli, Adaime and Binder (2010) talk about the potential of social networks to influence education through the collective intelligence of groups of prosumers (content producers and consumers).

Studygrammers offer freely (on Instagram) and for the entire virtual community, what students usually exchange via WhatsApp: notes, doubts and/or encouragement. The order and aesthetics in their publications, together with the humanization of the relationship, complete the contribution of this informal learning community headed by their leaders-coaches.

The pedagogical and cultural possibilities of YouTube have also produced valuable scientific literature (Gilroy, 2010; Burgess & Green, 2018), discovering figures such as, for example, the booktuber: a young Internet user who recommends books in vlog format (Vizcaíno-Verdú, Contreras-Pulido, & Guzmán-Franco, 2019).

The veteran and versatile nature of Facebook can also be seen in the scientific production generated (Selwyn, 2009; Piscitelli & al., 2010; Sánchez, Cortijo, & Javed, 2014) and, by extension, in the rest of platforms such as WhatsApp and Twitter (Abdullah & Darshak, 2015; Túñez & Sixto, 2012), the contributions of this epigraph have significance beyond the national scale, since they include populations from different places, such as: Portugal, United Kingdom, United States, Australia, Turkey, Israel, Singapore and Indonesia.

The social network focus of this research, Instagram, is the most recent (2010), and continues to expand increasing in users, rating and notoriety (IAB, 2018).

In addition, it has been the object of several studies, which report the positive reception of students to the inclusion of Instagram as part of the learning methodology. Some of the results observed highlight the improvement in the presentation of papers through a flipped classroom model (Supiandi, Sari, & Subarkah, 2019), or the improvement of expression skills in the acquisition of a second language (Barbosa & al., 2017; Jalaludin, Abas, & Yunus, 2019).

However, the scope of this line of research has the following limitations: a) most existing references deal with the educational use of Instagram in a limited field known as SMILLA (social networks as an instrument of language learning); b) references are mostly concentrated in Asia; and c) studies are published extensively in the infamous "predator journals", which is why they are not referenced in this text. In contrast, there is not much scientific activity in the West. Moreover, most papers focus on docent view on this social platform, which justifies the relevance of undertaking a study focused on the academic activity of students, regardless of the institution.

Material and methods

Objectives and approach

This research addresses how Communication students use social networks outside the institutionalized educational environment, although directly linked to their higher education, with the aim of identifying new components and emerging learning processes. Within the heterogeneous digital ecosystem, attention is focused on a new actor: the studygrammer. A student who leads the #Studygram community of Instagram. The main purpose of the text is, therefore, to define and characterize his figure, while understanding the relationship and opinion of students in the Communication area about this phenomenon.

The analytical approach is comparative in relation to other networks or "influencers" of other fields, other degrees and other training stages. In this way, "Instagram use by Communication students" and "role played by the studygrammer" are established as dependent variables; and the independent variables are: "types of social network: Instagram or other", "purpose of learning: formal or informal", "field of knowledge: communication or other" and "education stage: university or earlier.”

Methodological design

The present design offers a triangulation of three techniques: questionnaires, participant observation and Philips 66 processed with Atlas.ti. The data on the academic uses in social networks and, in particular, from the #Studygrammer community, were obtained from 256 students from all the courses of the different degrees in Communication of a Spanish public university, both in person and online. The main collection instrument was an online questionnaire.

The innovative nature of the phenomenon initially posed a stumbling block to the development of sufficiently representative categories of variables. A pilot questionnaire was conducted that collected open-ended answers to those questions with less certainty about the possible options. The replication of responses to the pilot questionnaire facilitated the development of representative categories, which gave rise to manifest variables for analyzing behavior through closed options (many of them with a "multi-response" option).

During the participant observation, an appropriate technique to become acquainted with groups or communities outside the researcher (Gaitán & Piñuel, 1999), 15 random profiles (Spanish, English and Portuguese speaking) were followed for two weeks under the label #Studygram. This qualitative evaluation on the images and the associated "post" (the 10 top posts of each "hashtag" eliminating duplicates and posts not related to the object of study) allowed to characterize the figure of the studygrammer.

The methodological design was completed with the execution of a Philips 66, a conversational technique that is useful to organize the participation of large groups in limited times (Peñafiel, Torres, & Izquierdo, 2016). According to the protocol of the technique (Gaitán & Piñuel, 1999), 10 discussion groups were organized with a total of 56 participating subjects, all of them students of the double degree in Journalism and Audiovisual Communication.

The design of the groups did not determine homogeneity or heterogeneity variables, precisely because the first type (age, studies) adequately served the design of previously established independent variables. In addition, variables irrelevant to the ultimate purpose of the study were recognized, such as gender (which was randomly distributed and naturally annulled by the spontaneous group formation). Each group had a secretary who collected the main findings of the "group discourse" (Ibáñez, 2003) in writing. Alphanumeric coding was used to maintain the confidentiality and anonymity of the participants (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2007), and a spokesperson exposed the data in a meeting where each group had two rounds of intervention.

The exploitation of the documents generated by the groups was carried out with the Atlas.ti program, following the method of "thematic analysis", which allows to identify, organize and provide patterns or themes for the understanding of the phenomenon (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The strategy of open, axial and selective coding (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) was also used to create and organize the codes through networks or flow diagrams that graphically represented the possible systems of relationships between categories and/or codes. That is to say, linking participants' concepts and opinions.

In order to increase validity, another Philips 66 was carried out, whose data were not processed, although it did enable the verification of the hermeneutic unit of analysis in which a previously formed group (a classroom of peers) was constituted, which did not produce group biases in the discourse produced. An external auditor's review of the codebook was also requested (Creswell, 2012). The data collected in this phase of the study responded to the objective of knowing the relationship and the opinion of Communication students on the studygrammer phenomenon.

Analysis and results

Use of social media in informal learning

To contextualize the topic of learning in a peer community, one begins with the question: "habitually, what notes do you use to study?", where the answer "Those I take in class complemented with those of a colleague" obtained 70.07%.

|

|

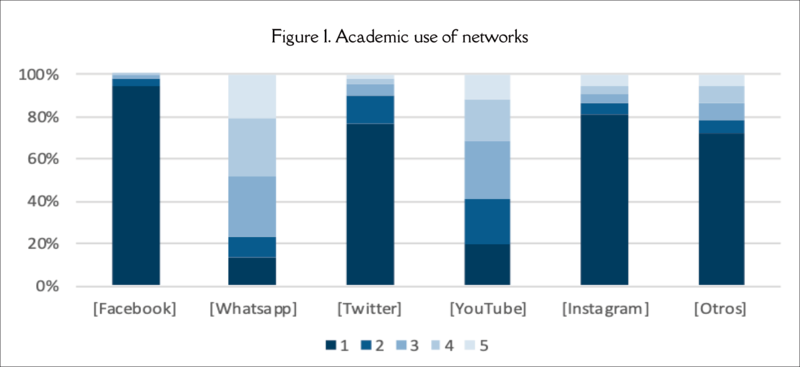

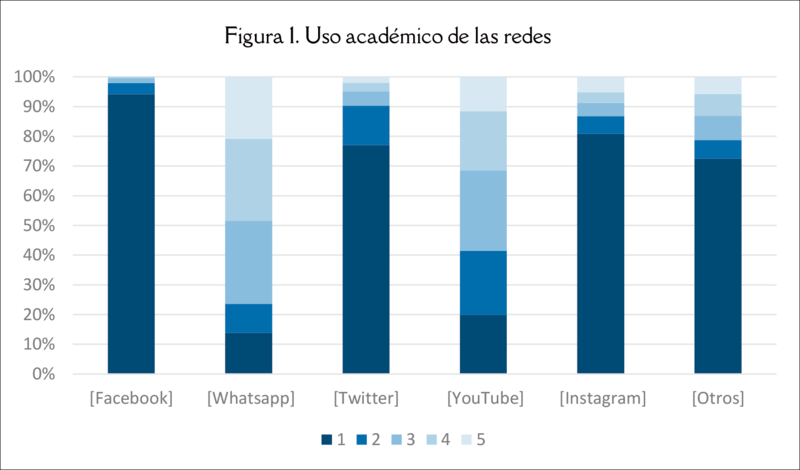

Regarding the usefulness of the educational use of social networks (Figure 1), only WhatsApp and YouTube have a significant utility (represented by lighter tones in Figure 1), where Facebook is indicated as the least useful, followed by Instagram and Twitter.

In relation to specific features, WhatsApp stands out for "solving short and practical doubts.” It is the only platform that has been indicated as very useful for: "sharing notes", "sharing general information about the degree and/or the university", "obtaining diagrams and summaries", "receiving encouragement" and "reviewing in company" (although the last three in less intensity). YouTube is considered the most appropriate for "complete explanations of complex subjects", its usefulness was most recognized in previous stages of training. In this sense, the data relating to the authorship of the videos that are consumed as academic support stands out: in secondary education 50% of the videos were made by professional teachers, in higher education this figure dropped to 30%. "The possibility of stopping and repeating the explanation" (sample testimony) and "we did not know how to make our own websites, blogs or profiles" (sample testimony) are the arguments offered. Likewise, it is relevant for this study to emphasize that the option "none" was the option most frequently mentioned with respect to receiving "study and planning advice.”

In order to completely understand the assessment of the educational use of social networks, it is essential to underline that the adjective most commonly used is "collaborative" (indicated 70.6% of the time), followed by "fast" (63.25%), while adjectives such as "clear" and "organized" obtained low scores: 3.3% and 9.6% respectively. The assessment "reproduces errors" had a significant incidence of 35%. Another element detected as a barrier when associating social networks and study was identified as a danger of distraction. Despite the balance expressed, a door remained open for the manifest opinion: "these are still used sparingly, but they could be used more and better", which obtained 58.3% support.

The figure of the studygrammer

Analysis of profiles and activities of the studygrammer

Instagram has over 3.5 million #Studygram publications. During the month of February, 2019 it accumulated 9.1 million interactions (Instagram, 2019), these figures invite an empirical observation of the phenomenon. The term #Studygram (also #Studigram, #Estudygram or #Estudigram) comes from the English root "Study" and the suffix "-gram" in reference to Instagram, where the "hashtag" or tag (#) indicates a particular community on the Web. The word "studygrammer" designates the person who publishes in the community, and although in its Spanish version it resembles English terms in line with other similar terms such as "youtuber", "booktuber" or "studytuber", it uses the suffix "-er", which in English forms nouns that indicate profession or occupation, equivalent to Spanish "-or" or "-ero.” In general, studygrammers post their notes, share experiences of their student life, offer advice on planning and studying, and sometimes resolve questions. It is a profile that dominates Instagram's communication codes, as their publications show meticulous care for all visual aspects: colors, calligraphy, framing and lighting. The order of both the content shown and the environment (table and/or desk) take center stage. In fact, this question is related to additional data obtained from the questionnaires, where 95% of the subjects "consider that having well-ordered notes that are pleasing to the eye can be a motivation to devote more time to studying.” Therefore, the use of these codes and visual elements of organization can produce a personal and community effect. The motivational factor does not only arise from inspiration it is also expressed explicitly. The phrases of self-improvement and the exchange of good wishes are present in the analyzed publications, where two message recipients are observed: themselves and the community. Analyzing the economic aspect, we observe two relevant elements: the presence of brands and online stores. The most important companies are those of markers, such as Stabilo Boss. Studygramers also monetize their online community by selling their diagrams, agendas and planners through online portals and/or with their personal brand. The most outstanding example is that of the British Communication student "Emma Studies", who has more than 450,000 followers and an online store.

Studygrammers in Communication undergraduate programs: Perception and assessment

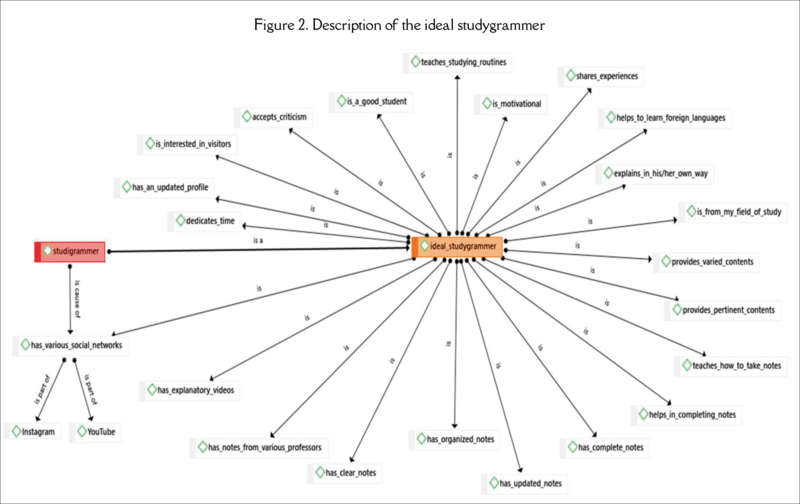

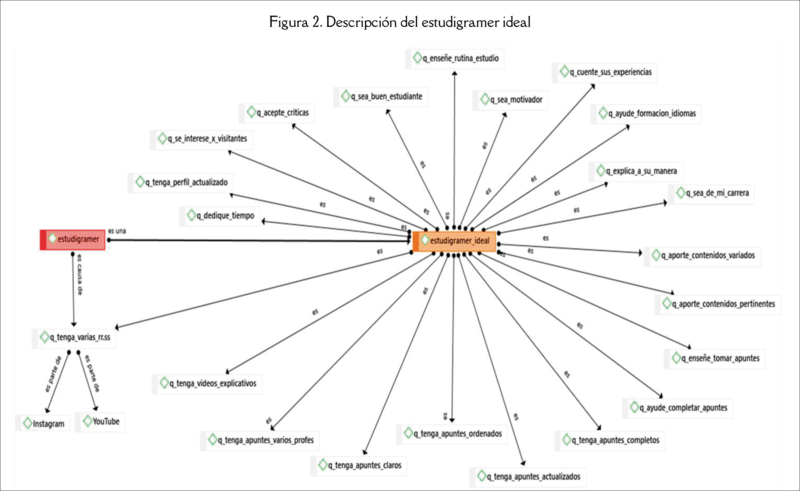

The most relevant data obtained both from the questionnaires and the discussion groups on the relationship (follow-up and opinion) of Communication Degree students with the studygrammer are the following: the students stated that they knew fewer studygrammers from their own degree program (4.4%) than from other fields (12.1%), among which they mentioned Medicine, Biology, Architecture, Fashion Design, Philosophy, Law, History, Engineering, Teaching, Physics and Mathematics. For 87.9%, the criteria for choosing to follow a studygrammer should be based on content, while for 12.1% on personality. However, to follow a generic influencer the personality does gain importance, increasing the degree of agreement to 58%. Considering the reasons to follow them, the most frequently mentioned is: "to complete notes" with 56.3%. Other reasons for deciding to be part of a studygrammer's community are: "for doubts" and "for advice" (both mentioned 37.6% of the time), followed by "for help to get organized" with 31.1%. These questions are reflected in the description that the reporting subjects make of their "ideal studygrammer" (Figure 2).

|

|

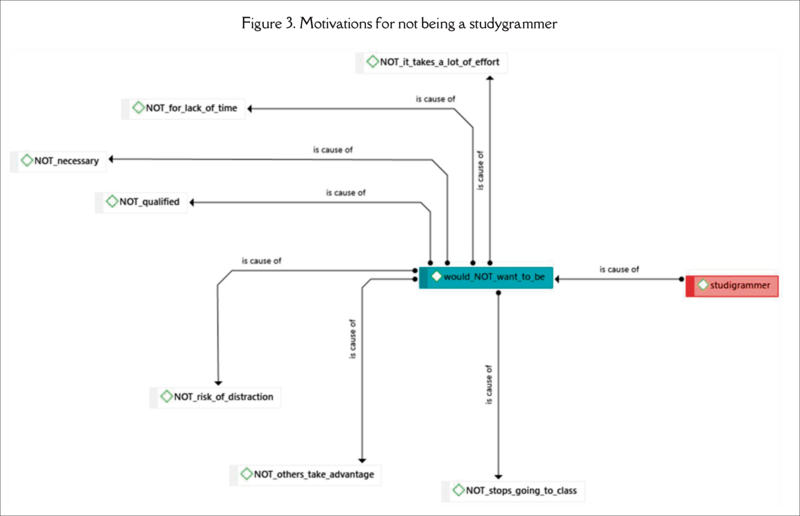

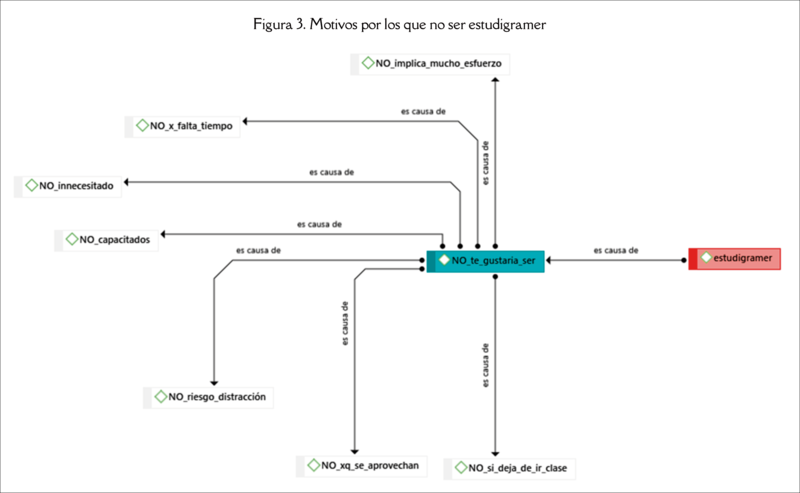

The variable "explains in his/her own way, with a language appropriate to our age" also stands out from this representation. Based on the economic question, 19.7% think that "having the activity of the studygrammers for educational purposes, they should not get any benefit. 48.7% think it is appropriate for them to "monetize their online community by selling their schemes and other content", and for 31.6% to do so "through collaborations with brands.” The fact that the economic variable comes into play in the #Studygram community does not seem to generate strong disagreement. A fact that may be explained by the opinion expressed regarding the reasons students consider that lead a person to become a studygrammer: "for helping" (50%), "for money" (43.8%) and "because they consider that they are good students" (37.5%). On the other hand, although 68% think it is a useful figure, 75% say they would not like to be a studygrammer. The reasons for this refusal are shown in Figure 3.

|

|

Discussion of results

The manifestations of the performance of informal peer learning reflect a certain "sense of community", with spatial limits that extend when social networks come into play, where they orbit around content sharing.

Initially, the educational usefulness of social networks perceived by students seems limited, because along with positive aspects, other negative factors continue to be identified. From the perspective of the learner, this opinion agrees with the one obtained from the teacher's point of view (Waycott & al.,2019) which, as previously commented, places its effects in both poles (Allcott & al., 2019). On the one hand, motivational benefits and community building are described; on the other, there is concern about the risk of students feeling exposed or having poor digital behavior (Waycott & al., 2019); only the value of WhatsApp, which functions as a virtual extension of what is usual in face to face interaction: sharing notes, doubts and encouragement with classmates, is highlighted.

During high school, YouTube is considered to play an outstanding role, not as a tool used among peers, but as a space for technical training (foreseeably also for personal development). Moreover, the professional teaching staff seems to favor, during the previous training stages, the delegation of regulated content in spaces outside the classroom, where the digital ecosystem helps as an extension of the lesson at home. This notion of "physical extension" (teaching staff, content), which is planned in the stories by incorporating the digital variable, highlights the importance of ubiquity as a characteristic of the virtual world and the specific contribution of cybertechnology to learning. Within the framework of learning ecologies in the digital age and contextualized within the rise of collaborative culture among young people (Scolari, 2018), we observe the existence of the studygrammer as a student using Instagram for academic purposes for himself and a community. As Arriaga, Marcellán-Baraze and González-Vida (2016: 211) state, "the act of sharing what is produced also contains, in itself, an act of learning, both for those who get a response to what they show, and for those who observe what is produced by others.”

Along with academic content in this community, motivational aspects aimed at two audiences are very present. Both self-motivation statements and community support slogans are frequent, with members also expressing inspiration for the care of visual details. The aesthetics and the order of notes, diagrams and the work table are the protagonists of the communication code. The element of stimulus detected in the activity of the studygrammer makes it possible to establish a connection with the figure of the booktuber (prescriber of literature in vlog format), since "in the same line, it facilitates ratification and meditation on the factor of affinity between peers as an eminent motivational driver for reading in everyday and informal environments" (Vizcaíno-Verdú & al., 2019).

Another remarkable part of the activity in the #Studygram community is the advice offered on the organization of the study task, especially valued by your community, which recognizes such deficiency. They also consider them useful for current training needs, seeking the incorporation of mechanisms that allow them to resolve similar situations in the future.

The presence of products in some profiles indicates agreed collaborations with commercial brands, mainly in the stationery sector; in other cases, the monetization of the community takes place through the sale of its contents in virtual stores. In short, studygrammers reproduce, probably intuitively and in a self-taught manner, the only two business models that social networks have developed to date to obtain income: advertising and the sale of digital services and goods (Muñoz, 2018).

|

|

The initial skepticism of students regarding the relevance of the educational use of social networks and their subsequent positive assessment of the #Studygram community may seem paradoxical, but it has an explanation. Studygrammers neutralize —with their characteristic aesthetics and order— the aspects that were identified as factors of social networks that do not contribute to learning: "not clear", "not organized.”

Similarly, their advice mitigated the shortcomings reported, since it is noted that to receive "advice on studying and planning" the most common option was "no social network." Therefore, this untapped potential manifested in the subjects, became tangible through the personal leadership component. In fact, studygrammers carry out those same functions that, from the beginning, were recognized in the use of WhatsApp (exchanging notes, doubts, encouragement). Now, studygrammers do it in open, where the messaging network selected is the intracommunity. The fundamental stigma in the combination of social networks and studies is marked by the recognition of the threat of distraction that these can pose when working (although it is also assumed that this is a factor of self-control).

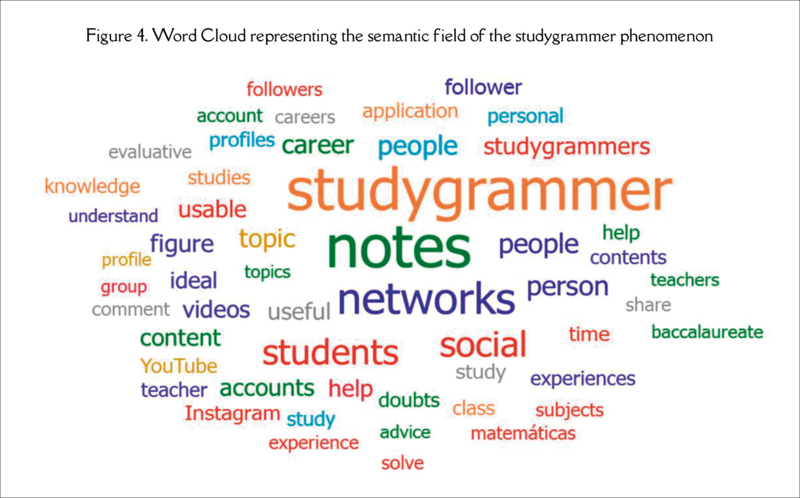

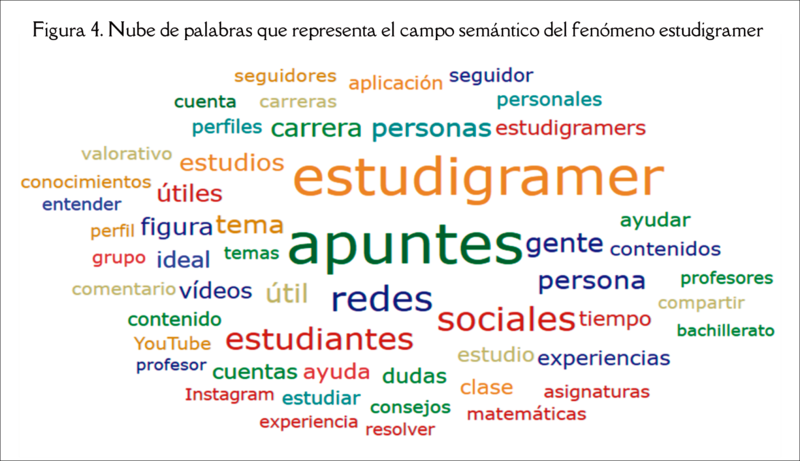

The fact that it is a contemporary community appears to add value to the groups, since the subjects valued the fact that studygrammers used familiar words (appropriate to their age group) in explanations. The analysis of booktubers also reflects the generational alignment, positively reporting the prosumer role of young people around training, from which "new youth exercises in social networks find new tactics of literary development in environments that are beyond academic control, but which, likewise, are positive" (Vizcaíno-Verdú & al., 2019). In general, the whole "conversation" of the study moves within a specific framework that adequately focuses the phenomenon of study and enables one to understand its dimension as expressed in the following word cloud developed with the interventions in Philips 66 (Figure 4).

To finalize the characterization of the studygrammer, the general influencer phenomenon is analyzed in relation to the particular influencer for studying. The data on the "content" is seven times greater than the data related to "personality.” As a follow-up motivation, a more conscious decision is made to adhere to a learning community rather than a recreational one. This finding is in line with the results of Vizcaíno-Verdú and others (2019: 104) on the booktuber, when they state that, "unlike other studies on the identity and autobiographical fame of the youtuber (...) booktubing has created a synergy of collaboration, recommendation and participation among equals in which physical or psychic aspects are not as important as preferences and reflections.”

From the economic perspective, the differences between general influencers vs. influencers for studying are not so conclusive. On the one hand, half the subjects expressed their agreement with the monetization of the community of followers, when the answer for the reasons why someone becomes a studygrammer was very much "for helping" rather than "for benefit.”

The contribution of the present study limits their contributions to present-day culture and moments, since there are many factors that influence the life cycle of Web trends and, therefore, many cases of exhaustion of practices and actors by the socio-digital dynamics themselves.

Conclusions

The #Studygram phenomenon represents the new transmedia competences that Ferrés and Piscitelli (2012) describe as: 1) learning by doing what you like; 2) learning by simulation; 3) learning by perfecting one's own or others' work; 4) learning by teaching, where the young person transmits and receives knowledge. The first skill is led by the studygrammer, the second by the follower, and the third and fourth by the whole community. This places studygrammers and their activity within the growing group of informal digital practices that contribute to the young people's learning (Scolari, 2018), exemplifying the so-called visual culture learning communities (Freedman & al., 2013).

As a result of this research, a definition of studygrammer is proposed: "A student who exercises, through Instagram, a peer-to-peer mentoring role in the academic field, not only sharing notes and outlines, but also transmitting advice, encouragement and experiences." Likewise, the following characterization proposal is proposed as a result: "The studygrammer incorporates the influencer nature: mastery of the aesthetics and monetization of online activity, where the academic purpose adds its own characteristics." Among their followers the rational motives have more weight than the emotional ones for community adhesion, that is to say, what to follow becomes more important than who to follow.

The visual code functions as a lingua franca between fields of knowledge. In fact, a studygrammer can be followed by students from other degrees because "how it's done" is also relevant. The learning mechanisms that underlie the studygrammer's activity and their virtual community are considered a practice and a positive contribution to the formative needs of today's society.

References

- AbdullahA, DarshakP, . 2015.Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook in economics classrooms&author=Abdullah&publication_year= Incorporating Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook in economics classrooms.The Journal of Economic Education 46(1):56-67

- AllcottH, BraghieriL, EichmeyerS, GentzkowM, . 2019.welfare effects of social media&author=Allcott&publication_year= The welfare effects of social media.National Bureau of Economic ResearchWorking paper No. 25514

- ArriagaA, Marcellan-BarazeI, Gonzalez-VidaM, . 2016.redes sociales: Espacios de participación y aprendizaje para la producción de imágenes digitales de los jóvenes&author=Arriaga&publication_year= Las redes sociales: Espacios de participación y aprendizaje para la producción de imágenes digitales de los jóvenes.Estudios sobre Educación 30:197-216

- BajoC, . 2015.media y derechos humanos en África. Nuevos medios para nuevos horizontes&author=Bajo&publication_year= Social media y derechos humanos en África. Nuevos medios para nuevos horizontes. In: García-JimenezA., Rubira-GarcíaR., eds. Comunicación en Derechos Humanos, tan cerca, tan lejos&author=García-Jimenez&publication_year= África: Comunicación en Derechos Humanos, tan cerca, tan lejos.Tenerife: Sociedad Latina de Comunicación Social. 99-117

- BarbosaC, BulhoesJ, ZhangY, MoreiraA, . 2017.do Instagram no ensino e aprendizagem de português língua estrangeira por alunos chineses na Universidade de Aveiro&author=Barbosa&publication_year= Utilização do Instagram no ensino e aprendizagem de português língua estrangeira por alunos chineses na Universidade de Aveiro.Revista Latinoamericana de Tecnología Educativa-RELATEC 16(1):21-33

- BraunV, ClarkeV, . 2006.thematic analysis in psychology&author=Braun&publication_year= Using thematic analysis in psychology.Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2):77-101

- BurgessJ, GreenJ, . 2018.Online video and participatory culture&author=&publication_year= YouTube: Online video and participatory culture. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Caldeiro-PedreiraM C, AguadedI, . 2017.Contenido e interactividad. ¿Quién enseña y quién aprende en la realidad digital inmediata?Virtualidad, Educación y Ciencia 8(15):95-105

- CallaghanN, BowerM, . 2012.through social networking sites. The critical role of the teacher&author=Callaghan&publication_year= Learning through social networking sites. The critical role of the teacher.Educational Media International 49(1):1-17

- Candon-MenaJ, . 2013.la calle, toma las redes. El movimiento 15M en internet&author=&publication_year= Toma la calle, toma las redes. El movimiento 15M en internet. Sevilla: Atrapasueños.

- CastellsM, . 2001. , ed. Internet&author=&publication_year= Galaxia Internet.Madrid: Plaza & Janés..

- CastellsM, . 2009. , ed. y poder&author=&publication_year= Comunicación y poder.Madrid: Alianza.

- CohenL, ManionL, MorrisonK, . 2007.methods in education&author=&publication_year= Research methods in education. London, New York: Routledge.

- CreswellJ W, . 2012.research. Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research&author=&publication_year= Educational research. Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Boston: Pearson.

- FerrésJ, PiscitelliA, . 2012.competence. Articulated proposal of dimensions and indicators. [La competencia mediática: Propuesta articulada de dimensiones e indicadores&author=Ferrés&publication_year= Media competence. Articulated proposal of dimensions and indicators. [La competencia mediática: Propuesta articulada de dimensiones e indicadores]]Comunicar 38:75-82

- FischerG N, . 1992.de intervención en psicología social&author=&publication_year= Campos de intervención en psicología social.

- FreedmanK, HeijnenE, Kallio-TavinM, KárpátiA, PappL, . 2013.culture learning communities: How and what students come to know in informal art groups&author=Freedman&publication_year= Visual culture learning communities: How and what students come to know in informal art groups.Studies in Art Education: A Journal of Issues and Research 54(2):103-115

- GaitanJ A, PiñuelJ L, . 1998. , ed. de investigación en comunicación social&author=&publication_year= Técnicas de investigación en comunicación social.Madrid: Síntesis.

- GilroyM, . 2010.Higher education migrates to YouTube and social networks.The Education Digest 75(7):18

- IAB Spain (Ed.). 2018.[Madrid: IAB. https://bit.ly/2Spfixp Estudio anual redes sociales 2018].

- IbañezJ, . 2003.se realiza una investigación mediante grupos de discusión&author=Ibañez&publication_year= Cómo se realiza una investigación mediante grupos de discusión.Análisis de la realidad social.

- JalaludinA M, AbasN A, YunusM M, . 2019.Teacher-pupil interaction&author=Jalaludin&publication_year= AsKINstagram: Teacher-pupil interaction.International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 9(1):125-136

- JenkinsH, . 2009.blogueros y videojuegos: La cultura de la colaboración&author=&publication_year= Fans, blogueros y videojuegos: La cultura de la colaboración. Barcelona: Paidós.

- López-PérezM V, Pérez-LópezM C, Rodríguez-ArizaL, . 2011.learning in Higher Education: Students’ perceptions and their relation to outcomes&author=López-Pérez&publication_year= Blended learning in Higher Education: Students’ perceptions and their relation to outcomes.Computers & Education 56(3):818-826

- MarchalN, KollanyiB, NeudertL M, PhilipN, . 2019. , ed. news during the EU parliamentary elections: Lessons from a Seven-Language study of Twitter and Facebook. Data Memo 2019.3&author=&publication_year= Junk news during the EU parliamentary elections: Lessons from a Seven-Language study of Twitter and Facebook. Data Memo 2019.3.Oxford, UK: Project on Computational Propaganda.

- MosqueraR, OdunowoM, McnamaraT, GuoX, PetrieR, . 2019. , ed. economic effects of Facebook. Working Paper&author=&publication_year= The economic effects of Facebook. Working Paper.Texas: A&M University.

- Muñoz-LópezL, . 2018. , ed. anual del sector de los contenidos digitales en España&author=&publication_year= Informe anual del sector de los contenidos digitales en España.Madrid: Observatorio Nacional de las Telecomunicaciones y la Sociedad de la Información (ONTSI).

- PeñafielC, TorresE, IzquierdoP, . 2016.cualitativa de gestores universitarios de investigación a través de un Philips 66&author=Peñafiel&publication_year= Percepción cualitativa de gestores universitarios de investigación a través de un Philips 66. In: HerreroJ., MateosC., eds. verbo al bit &author=Herrero&publication_year= Del verbo al bit .Tenerife: Sociedad Latina de Comunicación Social. 790-810

- PereiraS, FillolJ, MouraP, . 2019.people learning from digital media outside of school: The informal meets the formal. [El aprendizaje de los jóvenes con medios digitales fuera de la escuela: De lo informal a lo formal&author=Pereira&publication_year= Young people learning from digital media outside of school: The informal meets the formal. [El aprendizaje de los jóvenes con medios digitales fuera de la escuela: De lo informal a lo formal]]Comunicar 58:41-50

- PiscitelliA, AdaimeI, BinderI, . 2010.proyecto Facebook y la posuniversidad. Sistemas operativos sociales y entornos abiertos de aprendizaje&author=&publication_year= El proyecto Facebook y la posuniversidad. Sistemas operativos sociales y entornos abiertos de aprendizaje. Madrid: Ariel.

- RheingoldH, . 2004.inteligentes. La próxima revolución social&author=&publication_year= Multitudes inteligentes. La próxima revolución social. Barcelona: Gedisa.

- ScolariC, . 2016.Estrategias de aprendizaje informal y competencias mediáticas en la nueva ecología de la comunicación.Telos 13:1-9

- ScolariC, . 2018. , ed. medios de comunicación y culturas colaborativas. Aprovechando las competencias transmedia de los jóvenes en el aula&author=&publication_year= Adolescentes, medios de comunicación y culturas colaborativas. Aprovechando las competencias transmedia de los jóvenes en el aula.Barcelona: Ce.Ge.

- SelwynN, . 2009.Exploring students’ education-related use of Facebook&author=Selwyn&publication_year= Faceworking: Exploring students’ education-related use of Facebook.Learning, Media and Technology 34(2):157-174

- Serrano-PastorR M, Casanova-LópezO, . 2018.tecnológicos y educativos destinados al enfoque pedagógico Flipped Learning&author=Serrano-Pastor&publication_year= Recursos tecnológicos y educativos destinados al enfoque pedagógico Flipped Learning.REDU 16(1):155-173

- StraussA L, CorbinJ M, . 1990.of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques&author=&publication_year= Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- SupiandiU, SariS, SubarkahC Z, . 2019.Students higher order thinking skill through instagram based flipped classroom learning model&author=Supiandi&publication_year= Enhancing Students higher order thinking skill through instagram based flipped classroom learning model. In: , ed. of the 3rd Asian Education Symposium (AES 2018), 253&author=&publication_year= Proceedings of the 3rd Asian Education Symposium (AES 2018), 253.233-237

- TanE, PierceN, . 2011.education videos in the classroom: Exploring the opportunities and barrier to the use of YouTube in teaching introductory sociology&author=Tan&publication_year= Open education videos in the classroom: Exploring the opportunities and barrier to the use of YouTube in teaching introductory sociology.Research in Learning Technology 19:125-132

- Torres-ToukoumidisA, Romero-RodríguezL M, Pérez-RodríguezM A, . 2018.y sus posibilidades en el entorno de blended learning: Revisión documental&author=Torres-Toukoumidis&publication_year= Ludificación y sus posibilidades en el entorno de blended learning: Revisión documental.RIED 21(1):95-111

- TuñezM, SixtoJ, . 2012.Las redes sociales como entorno docente: Análisis del uso de Facebook en la docencia universitaria.Pixel-Bit 41:77-92

- Vizcaíno-VerdúA, Contreras-PulidoP, Guzmán-FrancoM D, . 2019.and informal learning trends on YouTube: The booktuber. [Lectura y aprendizaje informal en YouTube: El booktuber&author=Vizcaíno-Verdú&publication_year= Reading and informal learning trends on YouTube: The booktuber. [Lectura y aprendizaje informal en YouTube: El booktuber]]Comunicar 59:95-104

- Fundación Telefónica (Ed.). 2015.[Madrid: Ariel. https://bit.ly/2p4YQYX La Sociedad de la Información en España 2015].

- WaycottJ, SheardJ, ThompsonC, ClerehanR, . 2013.students' work visible on the social web: A blessing or a curse?&author=Waycott&publication_year= Making students' work visible on the social web: A blessing or a curse?Computers & Education 68(1):86-95

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Las actuales ecologías de aprendizaje destacan por su variedad, dinamismo y mutabilidad, lo que requiere una observación análoga de las mismas. Este trabajo se centra en las culturas de aprendizaje informal juvenil emergentes, tomando como objetivo principal reconocer y caracterizar una nueva figura en medios sociales en línea: el estudigramer. Empleando cuestionarios (N=256), grupos de discusión organizados mediante Philips 66 (N=56) y Atlas.ti (análisis temático), y observación participante, se analizan: prácticas de uso académico en redes sociales por parte de estudiantes de Comunicación al margen del entorno institucional, la opinión sobre la comunidad #Studigram, y el análisis de perfiles. Los principales resultados se concentran en una propuesta de definición del estudigramer: véase aquel estudiante que ejerce la labor de mentor y líder entre pares del ámbito académico en Instagram. Este perfil no solo comparte apuntes (que sobresalen por su orden y detallada estética), sino que también transmite consejos, apoyo y experiencias. De hecho, el estudigramer mantiene la genética influencer al priorizar la estética y monetización en sus publicaciones. Se concluye que el fin académico añade características exclusivas a la comunidad, donde el código visual funciona como lengua franca entre ámbitos de estudio. En efecto, los estudigramers cuentan con seguidores de diversos grados académicos que buscan el «saber hacer» (gestión y planificación del aprendizaje), así como una adhesión fundamentalmente racional.

ABSTRACT

Present learning ecologies are diverse and change quickly, which demands a similar observation of the phenomenon. This paper is focused on the youth emerging informal learning communities and the study’s object is to discover and characterize a new figure in this landscape, the Studygrammer. With surveys (N=256), focus groups carried out through the Philips 66 technique and analyze with Atlas ti software (thematic analysis) we analyze: practices of academic social media use amongst Communication students and apart of the institutional enviroment, plus their opinions regarding the #Studygram community, #Studygrammer profiles from different degrees are also analyzed. Main results help us to concrete a definition for Studygrammer: a student that performs a mentoring (coach-leader) role amongst peers using Instagram, not only sharing notes (highly performed) but also tips, inspiration and experiences. They have the DNA of an influencer using the same visual code and monetizating their practices but the academic goal adds some peculiarities: the visual code works as lingua franca between different knowledge areas (students of a certain degree follow studygrammers which study different degrees, because they are also interested on the know-how learning process) and in the followers’ adhesion criteria we find more rational than emotional reasons.

Palabras clave

Estudigramer, Instagram, influencer, aprendizaje informal, redes sociales, comunidades de aprendizaje, estudiantes de comunicación, alfabetización transmedia

Keywords

Studygrammer, Instagram, influencer, informal learning, social media, learning communities, communication students, transmedia literacy

Introducción

Tras una extensa década de uso y estudio de redes sociales fluctuantes entre la panacea y el apocalipsis (Piscitelli, Adaime, & Binder, 2010), la madurez de su ciclo vital (IAB, 2018) invita a una lectura más ponderada de los posibles efectos (Allcott & al., 2019). La literatura científica deja constancia tanto de consecuencias negativas, normalmente asociadas a usos intensivos como: el malestar personal y la depresión, la adicción digital, el distanciamiento de actividades saludables y relaciones personales físicas, el mayor consumo de información sesgada y polarización política (Mosquera & al., 2019); como positivas: la obtención de información y entretenimiento, la evasión del aislamiento, el fomento de relaciones y participación social (Valkenburg & Peter, 2007). Si bien las preocupaciones son fundadas y legítimas, estos autores proponen evitar que lo negativo opaque lo positivo (Allcott & al., 2019).

La necesidad de relación del individuo con el grupo como anclaje del sentimiento de pertenencia, y la creación de la identidad grupal e individual, que también se forja en relación al grupo (Fisher, 1992), es característica del ser humano. Las redes sociales cumplen un gran papel en este sentido, pues tienen la potestad para ejercer influencia desde los albores de su existencia (Castells, 2001). De manera que la relación e influencia se consideran ingredientes destacados del concepto de comunidad. Estas plataformas en línea permiten conectar personas con intereses comunes, aunque no resulte ciertamente novedoso. Los aficionados siempre se han congregado alrededor de sus afinidades, pero, en este caso, con la peculiaridad que aporta la Red al sustituir el espacio físico por el virtual. Ello permite que las asociaciones se ciñan al tema que concierne conjuntamente y que, una vez logrado el objetivo común (o no), el vínculo se disuelva, pues «no hay carnés de miembros ni cuotas de adhesión, solo inquietudes comunes» (Bajo, 2015: 114). La puntualidad de la asociación no menoscaba la capacidad de transformación. Ejemplo de ello son las variadas mudanzas acontecidas en este siglo bajo el paraguas de la tecnopolítica (Castells, 2009; Candon-Mena, 2013) protagonizadas por las denominadas «multitudes inteligentes» (Rheingold, 2004). El crecimiento de la cultura participativa en la Red (Jenkins, 2009) también llega al ámbito didáctico. Así, el «alfabetismo transmedia» (Scolari, 2016) supone una nueva relación entre sujetos, TIC e instituciones educativas que afecta doblemente a la población juvenil.

Por un lado, se encuentra en pleno desarrollo formativo, y por otro, queda abiertamente expuesta a medios y tecnología. Sin embargo, es importante mantener una función vigilante desde la investigación, el hogar y la escuela, dado que un mayor tiempo de pantalla «no garantiza el desarrollo de la actitud reflexiva ni favorece el aprendizaje» (Caldeiro-Pedreira & Aguaded, 2017: 102). Es por ello que se invita a demandar «a los adolescentes capacidad de reflexión para alcanzar autonomía audiovisual» y a «desarrollar una mirada crítica que les permita sobrevivir en un mundo digitalizado» (Caldeiro-Pedreira & Aguaded, 2017: 102).

Estado de la cuestión

El mayor aporte de Internet y las TIC en el ámbito de la educación ha consistido en facilitar la innovación docente. La propia dinámica y lógica digital se ha convertido en aliada natural del nuevo modelo docente basado en el trabajo colaborativo, autónomo y descentralizado. El marco científico relacionado con los efectos positivos de la introducción de la tecnología en los procesos de aprendizaje abarca todo tipo de escenarios, destrezas y procedimientos. Las experiencias en el entorno formal reportan avances en cuanto a metodologías como el flipped learning, que se apoya en el uso de recursos digitales fuera y dentro del aula (Serrano & Casanova, 2018), la usabilidad de los Entornos Personales de Aprendizaje (PLE) y la ludificación (Torres-Toukoumidis, Romero-Rodríguez, & Pérez-Rodríguez, 2018), a partir de los cuales se distingue una elevada adquisición de destrezas (Callaghan & Bower, 2012; López-Pérez, Pérez-López, & Rodríguez-Ariza, 2011).

La constatación empírica de estas experiencias incluye tanto procesos formales como informales. Pereira, Fillol y Moura (2019) afirman que, a pesar de la visión excesivamente institucionalizada de la educación, las estrategias de aprendizaje informal contribuyen al desarrollo de capacidades y competencias útiles desde un punto de vista escolar. De hecho, las destrezas adquiridas con el uso de las infotecnologías superan el ámbito cognitivo para cubrir también el social y el emocional (Tan & Pierce, 2011). Simplemente, la transversalidad, ubicuidad y versatilidad del espacio virtual lo hace más «amable» para los jóvenes, que también lo aprovechan para aprender sin establecer diferencias. El ilimitado espacio digital no responde a la lógica estanca del mundo pre-digital, puesto que «a diferencia de otros entornos exclusivamente dedicados al aprendizaje (…) la oportunidad de interactividad que ofrecen las redes sociales configura un espacio completamente híbrido en el que no es posible distinguir cuándo los jóvenes están compartiendo y cuándo están aprendiendo» (Arriaga, Marcellan-Baraze, & González-Vida, 2016: 213).

El recorrido existencial de las redes sociales también permite observar una evolución en sus usos. Si bien en los comienzos se detectaba un predominio del entretenimiento, a partir de 2015 se constata un incremento de su uso para fines profesionales (Fundación Telefónica, 2016). Recientemente, el Internet Oxford Institute ha detectado un descenso en su empleo para mantenerse informado a favor del consumo de noticias vía medios tradicionales (Marchal, 2019).

El estudigramer ofrece en abierto (vía Instagram) para toda su comunidad virtual lo que habitualmente los estudiantes intercambian vía WhatsApp: apuntes, dudas y/o ánimos. El orden y la estética en sus publicaciones junto a la humanización de la relación completan el aporte de esta comunidad de aprendizaje informal protagonizada por su líder-coach.

Y es que, en relación con su utilización con fines didácticos, Piscitelli, Adaime y Binder (2010) hablan del potencial de las redes sociales para influir en la educación mediante la inteligencia colectiva de grupos de prosumidores (productores y consumidores de contenidos). Las posibilidades pedagógicas y culturales de YouTube también han producido valiosa literatura científica (Gilroy, 2010; Burgess & Green, 2018), descubriendo figuras como, por ejemplo, el booktuber: un joven internauta que recomienda libros en formato vlog (Vizcaíno-Verdú, Contreras-Pulido, & Guzmán-Franco, 2019). La veteranía y polivalencia de Facebook también se percibe en la producción científica generada (Selwyn, 2009; Piscitelli & al., 2010; Sánchez, Cortijo, & Javed, 2014) y, por extensión, en el resto de plataformas como WhatsApp y Twitter (Abdullah & Darshak, 2015; Túñez & Sixto, 2012). Los aportes de este epígrafe tienen significación más allá de la escala nacional, puesto que incluyen poblaciones de diversos lugares, tales como: Portugal, Reino Unido, Estados Unidos, Australia, Turquía, Israel, Singapur e Indonesia. La red social foco de esta investigación, Instagram, es la más reciente (2010), y continúa en expansión aumentando en usuarios, valoración y notoriedad (IAB, 2018).

Adicionalmente, ha sido objeto de varios estudios, los cuales reportan la positiva acogida de los discentes a la inclusión de Instagram como parte de la metodología de aprendizaje. Algunos de los resultados observados destacan la mejora en la presentación de trabajos mediante un modelo flipped classroom (Supiandi, Sari, & Subarkah, 2019), o la mejora de las destrezas de expresión en la adquisición de una segunda lengua (Barbosa & al., 2017; Jalaludin, Abas, & Yunus, 2019).

No obstante, el alcance de esta línea de investigación presenta las siguientes limitaciones: a) la mayoría de referencias existentes tratan el uso educativo de Instagram en un campo limitado conocido como SMILLA (redes sociales como instrumento del aprendizaje de lenguas); b) las referencias mayoritariamente se concentran en Asia; y c) los estudios se publican sobremanera en las renombradas «predator journals» (revistas predadoras), motivo por el cual no se citan en este texto.

Por contraste, no se registra abundante actividad científica en la zona occidental. Es más, no existen trabajos que despunten en el foco docente en esta plataforma social, lo cual justifica la pertinencia de abordar un estudio centrado en la actividad académica del alumnado, independientemente de la institución.

Material y métodos

Objetivos y planteamiento

La presente investigación aborda cómo el alumnado de Comunicación utiliza las redes sociales fuera del entorno educativo institucionalizado, aunque directamente vinculado a su formación superior, con el objetivo de identificar nuevos componentes y procesos de aprendizaje emergentes. Dentro del heterogéneo ecosistema digital, la atención se focaliza en un nuevo actor: el estudigramer. Estudiante que lidera la comunidad #Studigram de Instagram. El fin principal del texto es, por tanto, definir y caracterizar su figura, así como conocer la relación y la opinión de los estudiantes de grados del área de Comunicación sobre este fenómeno. El planteamiento analítico es comparativo en relación con otras redes o «influencers» de otros ámbitos, otros grados y otras etapas de formación. De este modo, se establecen como variables dependientes «uso de Instagram de estudiantes de Comunicación» y «papel desempeñado por el estudigramer»; y como variables independientes: «tipos de red social: Instagram u otra», «fin del aprendizaje: formal o informal», «área de conocimiento: comunicación u otra» y «etapa de los estudios: universitaria o anterior».

Diseño metodológico

El presente diseño ofrece una triangulación de técnicas: cuestionarios, observación participante y Philips 66 tratados con Atlas.ti. Los datos sobre usos académicos en redes sociales y, en concreto, de la comunidad #Studigramer, fueron obtenidos a partir de 256 estudiantes de todos los cursos de los diferentes grados de Comunicación de una universidad pública española, tanto de la modalidad presencial como online. El instrumento de recogida principal fue el cuestionario telemático.

El innovador carácter del fenómeno, supuso en un primer momento un escollo para elaborar categorías suficientemente representativas de las variables. Se llevó a cabo un cuestionario piloto que recogía respuestas abiertas en aquellas preguntas sobre las que se tenía menos certeza sobre las posibles opciones. La réplica de respuestas al cuestionario piloto facilitó la elaboración de categorías representativas, que dieron lugar a variables manifiestas para analizar el comportamiento mediante opciones cerradas (muchas de ellas con opción de «multirespuesta»).

Durante la observación participante, técnica adecuada para la familiarización con grupos o comunidades ajenas al investigador (Gaitán & Piñuel, 1999), se hizo un seguimiento de dos semanas a 15 perfiles aleatorios (de habla española, inglesa y portuguesa) bajo la etiqueta #Studigram. Esta evaluación cualitativa sobre las imágenes y los «post» asociados (los 10 top de cada «hashtag» eliminando los duplicados o no relacionados con el objeto de estudio) permitió caracterizar la figura del estudigramer.

El diseño metodológico se completó con la ejecución de un Philips 66, una técnica conversacional que resulta de utilidad para organizar la participación de grupos numerosos en tiempos limitados (Peñafiel, Torres, & Izquierdo, 2016). Acorde al protocolo de la técnica (Gaitán & Piñuel, 1999), se organizaron 10 grupos de discusión con un total de 56 sujetos participantes, todos ellos estudiantes del doble grado de Periodismo y Comunicación Audiovisual.

El diseño de los grupos no determinó variables de homogeneidad ni heterogeneidad, precisamente debido a que las del primer tipo (edad, estudios) servían adecuadamente al diseño de variables independientes previamente establecidas. Además, se reconocieron variables irrelevantes para el fin último del estudio como el género (que quedó aleatoriamente distribuido y naturalmente anulado por la formación espontánea de grupos).

Cada grupo contaba con un secretario que recogía en un documento escrito los principales hallazgos del «discurso del grupo» (Ibáñez, 2003). Se hizo uso de la codificación alfanumérica para mantener la confidencialidad y el anonimato de los participantes (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2007), y un portavoz que exponía los datos en un encuentro donde cada grupo contó con dos rondas de intervención.

La explotación de los documentos generados por los grupos se realizó con el programa Atlas.ti, siguiendo el método de «análisis temático», que permite identificar, organizar y proporcionar patrones o temas para la comprensión del fenómeno (Braun & Clarke, 2006). También se empleó la estrategia de codificación abierta, axial y selectiva (Strauss & Corbin, 1990), para crear y organizar los códigos a través de redes o diagramas de flujo que representaran gráficamente los posibles sistemas de relaciones entre las categorías y/o códigos. Es decir, vinculando conceptos y opiniones de los participantes. Para aumentar la validez, se realizó otro Philips 66 cuyos datos no se procesaron, aunque sí posibilitó la comprobación de la unidad hermenéutica de análisis en la que se constituyó un grupo previamente formado (una clase de compañeros), que no producía sesgos grupales en el discurso producido. También se solicitó la revisión de un auditor externo del libro de códigos (Creswell (2012). Los datos recopilados en esta fase de la investigación respondieron al objetivo de conocer la relación y la opinión de los estudiantes de grados de Comunicación sobre el fenómeno de los estudigramers.

Análisis y resultados

Uso de redes sociales en el aprendizaje informal

Para contextualizar el tema del aprendizaje en la comunidad de pares, se comienza con la pregunta: «habitualmente, ¿con qué apuntes estudias?», donde la respuesta «Los que yo tomo en clase complementados con los de algún compañero/a» obtiene un 70,07%.

|

|

Por lo que respecta a la utilidad del uso educativo de las redes sociales, únicamente WhatsApp y YouTube presentan una utilidad significativa (representada por tonos más claros en la Figura 1), donde Facebook es señalada como la menos útil, seguida de Instagram y Twitter.

En relación con las utilidades concretas, WhatsApp destaca por «resolver dudas» fundamentalmente breves y de carácter práctico. Es la única plataforma que se ha señalado como muy útil para: «compartir apuntes», «compartir información general del grado y/o la universidad», «obtener esquemas y resúmenes», «recibir ánimos» y «repasar en compañía» (aunque las tres últimas en menor intensidad). YouTube se considera la más apropiada para «explicaciones completas de materia compleja», siendo su utilidad más reconocida en etapas de formación previas.

En este sentido, se destaca el dato de la autoría de los vídeos que se consumen como apoyo académico: en la educación secundaria el 50% de los vídeos eran de profesores profesionales, en la formación superior esa cifra descendía hasta el 30%. «La posibilidad de parar y repetir la explicación» (testimonio muestra) y «no sabíamos hacer webs ni blogs ni perfiles propios» (testimonio muestra) son las argumentaciones ofrecidas. Asimismo, es relevante para esta investigación recalcar que la opción «ninguna» fue la más señalada respecto a recibir «consejos de estudio y planificación».

Para terminar de entender la valoración del uso educativo de las redes sociales, resulta imprescindible subrayar que el adjetivo más empleado es «colaborativo» (señalado el 70,6% de las veces), seguido de «rápido» (63,25%). Por otro lado, adjetivos como «claro» y «organizado» obtienen baja puntuación: 3,3% y 9,6% respectivamente. La valoración «reproduce errores» tiene una incidencia significativa del 35%.

Otro elemento detectado como barrera al asociar redes sociales y estudio es el reconocido como peligro de distracción. A pesar del balance manifestado, la puerta queda abierta para la manifiesta opinión: «aún se usan poco, pero se podrían usar más y mejor», que obtiene un 58,3% de respaldo.

La figura del estudigramer

Análisis de perfiles y actividad del estudigramer

Instagram cuenta con más de 3,5 millones de publicaciones #Studigram. Durante el mes de febrero de 2019 acumuló 9,1 millones de interacciones (Instagram, 2019), cifras que invitan a una observación empírica del fenómeno. El término #Studigram (también #Studygram, #Estudygram o #Estudigram) proviene de la raíz inglesa «Study» y el sufijo «-gram» en alusión a Instagram, donde el «hashtag» o etiqueta (#) indica una comunidad concreta en la Red. El vocablo «estudigramer» designa a quien realiza publicaciones en la referida comunidad, y aunque es una versión castellanizada (al igual que otros términos análogos como «youtuber», «booktuber» o «estudituber») utiliza el sufijo «-er», que en inglés forma sustantivos que indican profesión u ocupación, equivalente al español «-or» o «-ero». En general, los estudigramers exponen sus apuntes, comparten experiencias de su vida estudiantil, ofrecen consejos sobre planificación y estudio y, a veces, resuelven dudas. Se trata de un perfil que domina los códigos de comunicación de Instagram, pues sus publicaciones muestran un cuidado minucioso de todos los aspectos visuales: colores, caligrafía, encuadre e iluminación.

El orden, tanto del contenido mostrado como del entorno (mesa y/o escritorio), cobra gran protagonismo. De hecho, esta cuestión se relaciona con otro dato obtenido de los cuestionarios, donde el 95% de los sujetos «considera que tener apuntes bien ordenados y agradables a la vista puede ser una motivación para dedicar más tiempo a estudiar». Por tanto, se valora que el empleo de estos códigos y elementos visuales de organización pueden producir un efecto personal y comunitario. El factor motivacional no solo aparece por inspiración, también se expresa explícitamente. Las frases de auto-superación y el intercambio de buenos deseos están presentes en las publicaciones analizadas, donde se vuelven a observar dos destinatarios del mensaje: ellos mismos y la comunidad. Analizando el aspecto económico, observamos dos elementos relevantes: presencia de marcas y tiendas en línea. Las empresas figurantes en mayor medida son las de rotuladores, como Stabilo Boss. Los estudigramer también monetizan su comunidad online vendiendo sus esquemas, agendas y planificadores a través de portales online y/o con su marca personal. El ejemplo más destacado es el de la estudiante británica de Comunicación «Emma Studies», que tiene más de 450.000 seguidores y tienda online.

|

|

Los estudigramers en los Grados de Comunicación: percepción y valoración

Los datos más relevantes obtenidos tanto de los cuestionarios como de los grupos de discusión sobre la relación (seguimiento y opinión) de los discentes de los Grados de Comunicación con los estudigramer son los siguientes: los estudiantes manifestaron conocer menos estudigramers de su propio Grado (4,4%) que de otras carreras (12,1%), entre las que mencionaron Medicina, Biología, Arquitectura, Diseño de Moda, Filosofía, Derecho, Historia, Ingeniería, Magisterio, Física y Matemáticas. Para el 87,9%, el criterio de elección para seguir a un estudigramer debe basarse en los contenidos, mientras que para el 12,1% en la personalidad.

Sin embargo, para seguir a un influencer genérico la personalidad sí cobra importancia, aumentando el grado de acuerdo hasta el 58%. Atendiendo a los motivos para seguirles, el más señalado es: «para completar apuntes» con un 56,3%. Otras causas para decidir formar parte de la comunidad de un estudigramer son: «para dudas» y «para consejos» (ambas mencionadas en un 37,6% de las ocasiones), seguidas de «ayuda para organizarse» con un 31,1 %. Estas cuestiones se reflejan en la descripción que los sujetos informantes realizan de su «estudigramer ideal» (Figura 2).

De esta representación destaca también la variable «explica a su manera, con lenguaje de nuestra edad». En base a la cuestión económica, al 19,7% les parece que «al tener la actividad de los estudigramers fines educativos, no debieran obtener ningún beneficio». Al 48,7% les parece adecuado que «moneticen su comunidad online vendiendo sus esquemas y otros contenidos», y al 31,6% que lo hagan «a través de colaboraciones con marcas». Que la variable económica entre en juego en la comunidad #Studigram no parece generar un desacuerdo contundente. Un hecho que quizá se explique por la opinión manifestada respecto a los motivos que el alumnado considera que llevan a una persona a hacerse estudigramer: «por ayudar» (50%), «por dinero» (43,8%) y «porque consideran que son buenos estudiantes» (37,5%). Por otro lado, aunque al 68% sí les parece una figura útil, el 75% manifiesta que no les gustaría ser estudigramer. Los motivos de tal negativa se recogen en la Figura 3.

|

|

Discusión de los resultados

El conjunto de manifestaciones acerca del desempeño del aprendizaje informal entre pares apunta a un cierto «sentido de comunidad», el cual ve sus límites espaciales ampliados cuando entran en juego las redes sociales, donde se orbita en torno a compartir contenidos.

Inicialmente, la utilidad percibida por los estudiantes sobre el uso educativo de las redes sociales parece limitada, pues junto a aspectos positivos se siguen señalando otros factores negativos. Desde la perspectiva del discente, esta opinión concuerda con la obtenida desde el punto de vista del docente (Waycott & al., 2019) que, como ya se comentó previamente sitúa sus efectos en ambos polos (Allcott & al., 2019). Por un lado, se describen beneficios motivacionales y construcción de comunidades. Por otro, se habla de preocupación sobre el riesgo a que los estudiantes se sientan expuestos o a la pobre conducta digital (Waycott & al., 2019). Únicamente se destaca el valor de WhatsApp, que funciona como extensión virtual de lo que en el espacio físico es habitual: compartir apuntes, dudas y ánimos con los compañeros de clase.

Durante Bachillerato, se considera que YouTube cumple un papel destacado, no como herramienta usada entre pares, sino como un espacio para la capacitación técnica (previsiblemente también de desarrollo personal). Es más, el profesorado profesional parece que favorece durante las etapas de formación previas, la delegación del contenido reglado en espacios ajenos al aula, donde el ecosistema digital ayuda como prolongación de la lección en casa. Sin embargo, en la fase universitaria el apoyo y ayuda del aprendizaje informal parece estar sostenido más por la propia comunidad de discentes. Esta noción de «extensión física» (profesorado, contenidos) que se planea en los relatos al incorporar la variable de lo digital, destaca la importancia de la ubicuidad como característica del mundo virtual y aporte específico de la cibertecnología al aprendizaje.

En el marco de las ecologías de aprendizaje en la era digital y, contextualizado dentro el auge de la cultura colaborativa entre jóvenes (Scolari, 2018), observamos la existencia del estudigramer como un estudiante que utiliza Instagram con fines de estudio para sí mismo y para una comunidad. Se entiende que esta práctica resulta provechosa para todos los actores implicados, ya que como afirman Arriaga, Marcellán-Baraze y González-Vida (2016: 211), «el acto de compartir lo producido contiene también, en sí mismo, un acto de aprendizaje, tanto para quien obtiene una respuesta a lo que muestra, como para quien observa lo producido por otros».

Junto a contenidos académicos en esta comunidad, quedan muy presentes los aspectos motivacionales dirigidos a dos destinatarios. Son frecuentes tanto los enunciados de auto-motivación, como las consignas de apoyo a la comunidad, en cuyos miembros también se ha manifestado inspiración para el cuidado de los detalles visuales. La estética y el orden de apuntes, esquemas y mesa de trabajo, protagonizan el código de comunicación. El elemento de estímulo detectado en la actividad del estudigramer permite establecer una conexión con la figura del booktuber (prescriptor de literatura en formato vlog), pues «en la misma línea, facilita la ratificación y meditación sobre el factor de afinidad entre pares como eminente motor motivacional para la lectura en entornos cotidianos e informales» (Vizcaíno-Verdú & al., 2019).

Otra parte destacable de la actividad en la comunidad #Studigram son los consejos que se ofrecen sobre la organización de la tarea de estudio, especialmente valorados por su comunidad, que reconoce dicha carencia. También los consideran útiles para las actuales necesidades de formación, buscando la interiorización de mecanismos que permitan resolver futuras situaciones análogas.

El tipo de presencia de productos en algunos perfiles indica colaboraciones acordadas con marcas comerciales, principalmente del sector del material de papelería. En otros casos, la monetización de la comunidad se produce mediante la venta de sus contenidos en tiendas virtuales. En definitiva, los estudigramers reproducen, probablemente de manera intuitiva y autodidacta, los dos únicos modelos de negocio que hasta la actualidad han desarrollado las redes sociales para obtener ingresos: la publicidad y la venta de servicios y bienes digitales (Muñoz, 2018).

El inicial escepticismo mostrado por los estudiantes en relación con la utilidad del uso educativo de las redes sociales y su posterior valoración positiva de la comunidad #Studigram, puede parecer paradójico, pero tiene explicación. El estudigramer neutraliza con su estética y orden característicos los aspectos que fueron señalados como factores no coadyuvantes de las redes sociales al aprendizaje: «no claro», «no organizado». Del mismo modo, sus consejos palían las carencias reseñadas, pues se recuerda que para recibir «consejos de estudio y planificación» la opción más señalada fue «ninguna red social». Por tanto, ese potencial sin concretar que manifestaban detectar los sujetos, se hace tangible mediante el componente personal del liderazgo. De hecho, el estudigramer lleva a cabo aquellas mismas utilidades que, desde un principio, se le reconocieron a WhatsApp (intercambiar apuntes, dudas, ánimos). Ahora bien, el estudigramer lo hace en abierto, donde la red de mensajería se limitaba a la intracomunidad. El estigma fundamental en la asociación de redes sociales y estudio viene marcado al reconocer el peligro de distracción que estas pueden suponer a la hora de trabajar (aunque también se asume que este es un factor de autocontrol).

El tratarse de una comunidad coetánea parece sumar valor en la celebración de los grupos, ya que los sujetos valoraban el hecho de que los estudigramer usen palabras cercanas (propias de su grupo etario) en las explicaciones. El análisis del booktuber también refleja la sintonía generacional, al reportar positivamente el papel prosumidor de los jóvenes en torno a la formación, a partir de la cual «los nuevos ejercicios juveniles en redes sociales encuentran nuevas tácticas de desarrollo literario en entornos que escapan al control académico, pero, que, de igual modo, resultan positivos» (Vizcaíno-Verdú & al., 2019). En general, toda la «conversación» de la investigación se mueve en un marco concreto que centra adecuadamente el fenómeno de estudio y permite comprender su dimensión tal y como expresa la siguiente nube de palabras elaborada con las participaciones del Philips 66 (Figura 4).

|

|

Para terminar de perfilar la caracterización del estudigramer, se analiza el peso replicado del fenómeno influencer general en el influencer de los estudios particular. El dato reportado en base al «contenido» pesa siete veces más que la «personalidad». Como motivo de seguimiento, se indica una decisión más consciente en la adhesión a una comunidad de aprendizaje que a una de fines más lúdicos. Este hallazgo se muestra en consonancia con uno de los resultados de Vizcaíno-Verdú y otros (2019: 104) sobre el booktuber, cuando afirman que, «a diferencia de otros estudios sobre la identidad y la fama autobiográfica del youtuber (…) el booktubing ha creado una sinergia de colaboración, recomendación y participación entre iguales en las que no importan tanto los aspectos físicos o psíquicos, sino los gustos y las reflexiones».

Desde la perspectiva económica, las diferencias influencer general vs. influencer de estudios no son tan conclusivas. Por un lado, la mitad de los sujetos manifestaron su acuerdo con la monetización de la comunidad de seguidores, cuando la respuesta para los motivos por los que alguien se hace estudigramer fueron sobremanera «por ayudar» frente a «por beneficio».

El presente estudio limita sus aportaciones a la cultura y momentos actuales, ya que son muchos los factores que influyen en el ciclo vital de las tendencias en la Red y, por ende, muchos también los casos de agotamiento de prácticas y actores por la propia dinámica sociodigital.

Conclusiones

El fenómeno #Studigram representa las nuevas destrezas transmedia que Ferrés y Piscitelli (2012) describen como: 1) aprender haciendo lo que gusta; 2) aprender por simulación; 3) aprender mediante el perfeccionamiento del trabajo propio o ajeno; 4) aprender mediante una enseñanza con la que el joven transmite y recibe conocimientos. La primera destreza la protagoniza el estudigramer, la segunda solo el seguidor/a, y la tercera y la cuarta toda la comunidad. Todo ello sitúa al estudigramer y su actividad dentro del creciente grupo de prácticas digitales informales que contribuyen al aprendizaje de los jóvenes (Scolari, 2018), suponiéndose un ejemplo concreto de lo que se denominan comunidades de aprendizaje de la cultura visual (Freedman & al., 2013).

Como resultado de esta investigación, se plantea una propuesta de definición de estudigramer: «estudiante que ejerce a través de Instagram una labor de mentor entre pares en el ámbito académico, que no solo comparte apuntes y esquemas, sino que también transmite consejos, ánimos y experiencias».

Asimismo, se plantea como resultado la siguiente propuesta de caracterización: «el estudigramer incorpora la genética influencer: dominio de la estética y monetización de la actividad online, donde el fin académico añade características propias». Entre sus seguidores pesan más los motivos racionales que los emocionales para la adhesión a la comunidad, es decir, importa más el qué seguir que a quién seguir.

El código visual funciona como lengua franca entre ámbitos de conocimiento. De hecho, un estudigramer puede ser seguido por estudiantes de otros Grados porque también es relevante «el cómo se hace». Los mecanismos de aprendizaje que subyacen a la actividad del estudigramer y su comunidad virtual se consideran una práctica y un aporte positivos de las necesidades formativas de la sociedad actual.

References

- AbdullahA, DarshakP, . 2015.Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook in economics classrooms&author=Abdullah&publication_year= Incorporating Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook in economics classrooms.The Journal of Economic Education 46(1):56-67

- AllcottH, BraghieriL, EichmeyerS, GentzkowM, . 2019.welfare effects of social media&author=Allcott&publication_year= The welfare effects of social media.National Bureau of Economic ResearchWorking paper No. 25514

- ArriagaA, Marcellan-BarazeI, Gonzalez-VidaM, . 2016.redes sociales: Espacios de participación y aprendizaje para la producción de imágenes digitales de los jóvenes&author=Arriaga&publication_year= Las redes sociales: Espacios de participación y aprendizaje para la producción de imágenes digitales de los jóvenes.Estudios sobre Educación 30:197-216