Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Plagiarism has engendered increasing concern in academia in the past few decades. While previous studies have investigated student plagiarism from various perspectives, how plagiarism is understood and responded to by university teachers, especially those in English-as-a-foreign-language (EFL) writing contexts, has been under-researched. As academic insiders and educators of future academics, university teachers play a key role in educating students against plagiarism and upholding academic integrity. Their knowledge of and attitudes toward plagiarism not only have a crucial influence on their students’ perceptions of plagiarism but can also provide insights into how institutions of higher education are tackling the problem. The study reported in this paper aims to address this imbalance in research on plagiarism by focusing on a sample of 108 teachers from 38 Chinese universities. Drawing on both quantitative and qualitative data that comprise textual judgments and writing samples, it examines whether EFL teachers in Chinese universities share Anglo-American conceptions of plagiarism, what stance they take on detected cases of plagiarism, and what factors may have influenced their perceptions. Findings from this study problematize the popular, yet over-simplistic, view that Chinese EFL writers are tolerant of plagiarism and point to academic and teaching experience as influences on their perceptions and attitudes concerning plagiarism.

1. Introduction

Academic writing builds on the current knowledge base by incorporating words and ideas from existing work into new texts (Pecorari & Petric, 2014). This is a convention-governed process (Pecorari, 2008) in which a writer has to comply with established and shared disciplinary practices to steer clear of plagiarism accusations. In the past few decades, the advent of the Internet and the boom of various information and communication technologies have made an ever increasing wealth of sources readily available and easy to plagiarize (Hu & Lei, 2012). The incidence of plagiarism has been on the increase and engendered growing concern in academia.

To tackle the problem of plagiarism, it is necessary to look beyond the symptoms to the underlying causes (Macdonald & Carroll, 2006). In essence, all contributing factors to plagiarism boil down to a certain deficiency in the perpetrators, who may lack academic integrity, the willingness, the necessary knowledge or the language skills to use sources appropriately (Pecorari, 2008). For second language (L2) writers who have to navigate the writing conventions associated with a new language, the contributing factors can be more complex. The most widely discussed factor is culture-specific views of plagiarism. It is frequently suggested that cultures differ in their understanding and acceptance of plagiarism (Bloch & Chi, 1995; Pennycook, 1996; Sapp, 2002; Scollon, 1995; Shei, 2005; Sowden, 2005). For example, literacy practices such as memorization and imitation of model texts that are common in Confucian-heritage cultures are often cited to explain why Chinese students in particular and Asian students in general tend to hold different conceptions of plagiarism (Bloch & Chi, 1995; Maxwell, Curtis, & Vardanega, 2008). Other researchers (Liu, 2005; Pecorari, 2008; Rinnert & Kobayashi, 2005), however, maintain that difficulties faced by L2 writers are more likely a result of their inadequate language proficiency, which may cause them to feel unconfident about their own language use and hence over-rely on source texts. Empirical studies on factors likely to influence understandings of and attitudes toward plagiarism have yielded contradictory findings, especially in terms of how enculturation in higher education may impact on knowledge of and stance on plagiarism (Chandrasegaran, 2000; Deckert, 1993; Lei & Hu, 2014; Sapp, 2002; Wheeler, 2009).

In Anglo-American academia, source documentation and attributed paraphrasing are considered two important strategies for avoiding plagiarism (Park, 2003)1. While the former is reasonably straightforward and can be done with adequate training, the latter entails high demands on subject knowledge and linguistic competence (Keck, 2010) and, as such, usually forms «a complex and often elusive experience for L2 writers» (Hirvela & Du, 2013: 87). Moreover, researchers and academic gatekeepers differ greatly in terms of their standards for sufficient paraphrasing. While some believe that to keep clear of plagiarism, there should be no traces in a paraphrase of verbatim copying of strings of even a few words from the original (Benos, Fabres, & Farmer, 2005; Roig, 2001; Shi, 2004), others adopt more lax standards by allowing the inclusion of more source text in a paraphrase (Keck, 2006; Pecorari, 2008). Empirical studies which examine paraphrasing practices in actual writing samples would provide a better understanding of what paraphrasing practices are considered acceptable by participants.

Considering the essential role that teachers can play in detecting and responding to student plagiarism and educating students against plagiarism, researchers have been directing increasing attention to teacher perceptions of plagiarism. Previous studies found that teachers differed among themselves as to what constitutes plagiarism (Borg, 2009; Flint, Clegg, & Macdonald, 2006; Pickard, 2006) and that many had little knowledge of institutional definitions of plagiarism and did not teach students about plagiarism effectively (Eriksson & Sullivan, 2008). In two of the very few such studies conducted in the Chinese context, Lei and Hu (2014; 2015) found that while most of the EFL teachers in their study could identify both unacknowledged copying and unattributed paraphrasing as plagiarism and/or held condemnatory attitudes toward detected plagiarism, their understandings of unattributed paraphrasing, which is considered a less clear-cut form of plagiarism than unacknowledged copying, appeared divergent and ambivalent. Apart from this, it remains largely unknown to what extent Chinese teachers’ perceptions of plagiarism are different from or similar to those widely accepted in Anglo-American academia. This lack of research on Chinese teachers’ understandings of plagiarism is surprising given the many studies done on Chinese learners in Anglophone and Chinese universities (Bloch & Chi, 1995; Deckert, 1993; Matalene, 1985; Pennycook, 1996; Sapp, 2002; Shi, 2004; Valentine, 2006).

To fill the gap in plagiarism research on Chinese teachers, we conducted a study on a sample of Chinese EFL teachers from multiple universities in mainland China to examine whether they shared Anglo-American standards abut plagiarism and what factors may have influenced their knowledge of and stance on plagiarism. We aimed to gather empirical evidence that could deepen our understanding of plagiarism as an important discursive phenomenon and put cultural explanations of plagiarism to the test (Flowerdew & Li, 2007). Specifically, the following research questions were formulated to guide this study: How well do Chinese university English teachers understand plagiarism? What are their attitudes toward recognized plagiarism? What factors may influence their knowledge of and attitudes toward plagiarism?

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

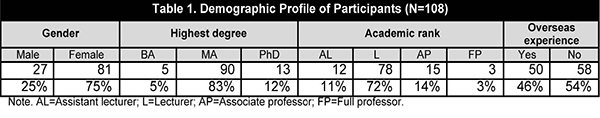

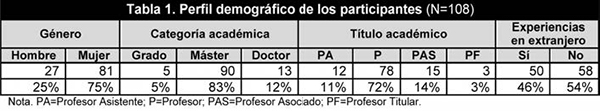

We adopted a combination of convenience and snowball sampling strategies for participant recruitment. We contacted our personal acquaintances who were English teachers in different Chinese universities, invited them to participate in the study, and asked for their assistance in recruiting colleagues who might be interested in participating in our study. Ultimately, 108 EFL teachers from 38 universities located in different regions of mainland China were involved. Table 1 summarizes the relevant demographic information on these participants. The sample ranged in age from 25 to 50 (M=34.33, SD=4.99) and comprised predominantly female teachers, reflecting the typical gender distributions of the female-dominated discipline in Chinese universities. It included both very experienced teachers and those new to the profession. The 107 participants who provided information about their length of teaching service had an average of 9.47 years of teaching experience (SD=5.39; range=1 to 27). A great majority of the participants held a Master’s degree and were hired at the academic rank of lecturer. Slightly less than half of the participants had overseas academic experience, that is, studying in universities in Anglophone countries or in English-as-a-second-language (ESL) contexts such as Hong Kong and Singapore, where the Anglo-American notions of plagiarism are widely adopted.

2.2. Instruments

We used two instruments to collect data: the Plagiarism Knowledge Survey (PKS), and the Paraphrasing Practices Survey (PPS). Both instruments were adapted from Roig (2001). The PKS aimed to explore whether the participants would recognize insufficient paraphrasing as plagiarism, to ascertain the criteria they adopted for determination, and to investigate their attitudes (e.g., punitive or lenient) toward recognized cases of plagiarism. It consisted of an original two-sentence paragraph and six rewritten versions of this paragraph. The first four versions were incrementally but insufficiently paraphrased from the original and thus were instances of plagiarism, whereas the last two versions were adequately paraphrased and free of plagiarism. As reported by Roig (1997), four American professors independently validated the instrument and agreed with the plagiarism characterization of the six written versions. The participants in our study were asked to compare each rewritten version with the original paragraph, choose one of the three provided options «plagiarized, not plagiarized, or cannot determine, and then provide reasons for their judgment. In order to elicit participants’ attitudes toward identified plagiarism, we added a rating scale of 0 to 10 points to the original PKS and asked them to rate each rewritten version according to the presence and gravity of plagiarism: the gravest case of plagiarism could be penalized by a zero, and a properly paraphrased paragraph might be awarded the highest score possible.

The PPS described a scenario in which participants had to paraphrase the following short paragraph from a journal article about astrology (Roig, 2001): «If you have ever had your astrological chart done, you may have been impressed with its seeming accuracy. Careful reading shows many such charts to be made up of mostly flattering traits. Naturally, when your personality is described in desirable terms, it is hard to deny that the description has the «ring of truth» (Coon, 1995: 29).

The instrument generated authentic writing samples by asking the participants to paraphrase the paragraph in a way that they believed would not constitute plagiarism. The participants were also required to fill out a personal information sheet which asked about their gender, age, educational background, teaching experience, number of academic publications, as well as the types of students and courses that they usually taught. Information on such variables was gathered because previous studies (Hu & Lei, 2012; Lei & Hu, 2014, 2015) suggested that they could have an impact on the participants’ knowledge of and stance on plagiarism as well as their paraphrasing practices.

2.3. Data coding and analysis

The PKS generated two sets of scores: the plagiarism knowledge scores (hereafter knowledge scores), and the plagiarism stance scores (hereafter stance scores). Knowledge scores were calculated following Roig (2001). For each participant, one point was given for each rewritten version that was correctly identified, two points for each rewritten version that was not identified (including both choices of «cannot determine» and cases where a participant failed to give any judgment), and three points for each version incorrectly identified. A participant who correctly identified all six rewritten versions would obtain a perfect score of 6, whereas one who misjudged all six cases would get 18 points. Thus, lower scores would indicate greater knowledge of plagiarism and paraphrasing. Stance scores were derived by calculating the mean of the ratings given by each participant to the rewritten paragraphs that s/he identified as plagiarized (regardless of whether the paragraph was designed as a case of plagiarism or proper paraphrasing). The higher a stance score, the more lenient the participant was toward recognized plagiarism. The knowledge and stance scores thus obtained were analyzed with SPSS (version 23.0) to obtain descriptive and inferential statistics needed for answering our research questions.

The PKS also generated qualitative data in the form of the participants’ written justifications for their judgments and ratings of the rewritten versions. The second author read these justifications repeatedly and analyzed them iteratively to identify the factors that the participants took into consideration when judging and rating the rewritten paragraphs. A coding scheme based on this analysis was then developed and used to capture the criteria the participants adopted to evaluate the rewritten versions. To ensure the reliability of the coding, a graduate student used the coding scheme to code a randomly selected subset of the data independently, and the inter-coder agreement was 100%.

The coding of the PPS data was conducted by the second author and consisted in identifying strings of three or more consecutive words in the paraphrases that were appropriated from the original paragraph. Because the coding did not involve subjective judgments, a second coder was not involved.

3. Findings

3.1. Results from the PKS

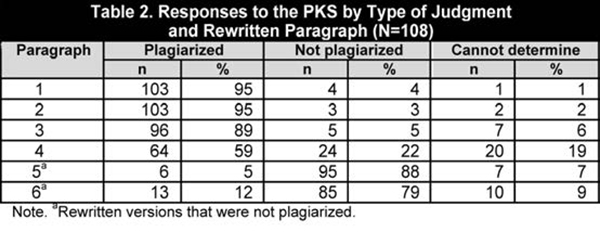

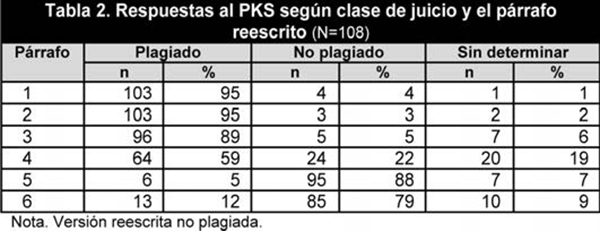

The participants’ knowledge scores were analyzed both descriptively and inferentially. The range, mean, and mode of the knowledge scores were calculated to gauge the extent to which the Chinese teachers as a group accurately identified cases of plagiarism. The mean knowledge score was 7.51 (SD= 1.488; range=6-12), indicating that the 108 participants were able to correctly identify most of the rewritten paragraphs. Notably, as many as 43 teachers (approximately 40%) had the perfect score of 6, attesting to a satisfactory knowledge of plagiarism and proper paraphrasing. To show how accurately the participants identified each rewritten version, the percentage of responses to each response category (i.e., «plagiarized, not plagiarized, cannot determine») for each rewritten version was calculated, and the results are summarized in table 2. Notably, none of the rewritten versions was judged with perfect consensus. For the first four rewritten versions, as the extent of reformulation increased, the percentages of correct identifications dropped, whereas the percentages of misidentifications and choices of the «cannot determine» category increased correspondingly. This pattern clearly indicated that difficulty in identifying plagiarism increased with the extent of change made to the original text; it also suggested the existence of different criteria for plagiarism and proper paraphrasing even among teachers from the same discipline.

Of the 108 participants, 102 provided written justifications for their judgments regarding the rewritten versions. An analysis of these justifications revealed that they used three criteria when evaluating the paragraphs. First, many participants based their judgments on the extent to which the original paragraph was changed. About 65% of the participants pointed out that to avoid accusations of plagiarism, one needs to rewrite the original to change its diction and/or structure, as illustrated by the following representative justifications:

• The rewritten paragraph is thoroughly paraphrased, i.e., the student uses all his own words as well as restructures the sentences to express the idea of the original paragraph (Rewritten version 5).

• [This is plagiarism] because the same or similar sentence structures are applied (Rewritten version 2).

• Changing the order of the original sentences without paraphrasing is definitely plagiarism (Rewritten version 1).

A second criterion used by the participants concerned the correct format of citation. Although the PKS instructions asked the participants to assume the inclusion of a proper citation for each rewritten version, many participants still emphasized the importance of acknowledging the source in the correct format, as can be seen in the following quotations:

• This version suggests clearly that it is the research result of another researcher. But it does not say whose idea it is and where it comes from (Rewritten version 4).

• The author points out the source of the finding and paraphrases it in his own words. It will be better if the researcher’s name is clearly mentioned (Rewritten version 5).

• In academic writing, it stipulates that you need to state overtly whose ideas you are discussing (Rewritten version 5).

Still another consideration the participants had was whether certain words or expressions were used to indicate that the writer was reporting another person’s ideas, as the following quotations illustrate:

• This is not P, since the writer uses many words to indicate that this is quoted from another researcher (Rewritten version 5).

• The writer used «according to one researcher» to indicate that he is retelling someone’s research results (Rewritten version 4).

A 3-way ANOVA was run to assess the potential impact of teaching experience, overseas academic experience, and educational attainment on the knowledge scores. The participants were divided into three groups according to their years of teaching (1-7, 8-14, 15+) and two groups according to their highest degrees (BA/MA, PhD). The one case with missing value on teaching experience was deleted, leaving 107 cases for the analysis. The analysis found that the knowledge scores were not influenced by teaching experience, F(3, 107)=.089, p=.966, ?p2=.003, overseas academic experience, F(1, 107)=.564, p=.454, ?p2=.006, or educational attainment, F(1, 107)=.147, p=.702, ?p2=.002. There was no significant interaction between teaching experience and educational attainment, F(2, 107)=.450, p=.639, ?p2=.009, between teaching experience and overseas academic experience, F(2, 107)=.882, p=.417, ?p2=.018, between educational attainment and overseas academic experience, F(1, 107)=.018, p=.892, ?p2 =.000, or among the three variables, F(1, 107)=.731, p=.398, ?p2=.008. The effect sizes indicated that none of the independent variables or the interactions reached the criterial value suggested by Cohen (1988) for a small effect (i.e., ?p2=.02).

The range, mean, and mode of the stance scores were obtained as measures of how the teachers as a group reacted to identified instances of plagiarism. The 108 respondents had a mean stance score of 1.73 (range=0-5.17), which indicated their overall punitive attitudes toward what they perceived to be plagiarism. Approximately 14% of the participants believed that no score should be awarded to a plagiarized text, and another 67.6% gave an average rating of less than 2 points. These results were consistent with an understanding of plagiarism as an act of stealing, as revealed in the following quotations:

• The first sentence is stolen from the original (Rewritten version 6).

• This one has made it clear enough this is a research finding of others but this cannot justify the act of «stealing» most [of] the sentences from the original paragraph (Rewritten version 4).

• The rewriter paraphrased the original statement through intentionally reversing the order of the sentences, without giving any credit to the author through citation. It is the steal of both language and ideas (Rewritten version 1).

A 3-way ANOVA was run to determine possible influences on the stance scores, with the three independent variables being teaching experience, overseas academic experience, and plagiarism knowledge. The participants were divided into three groups according to their knowledge scores (6 points, 7-9 points, and 10+). The ANOVA found that the stance scores were influenced by teaching experience, F(3, 107)= 3.306, p=.024, ?p2 =.099, but were not affected by overseas academic experience, F(1, 107)=3.245, p=.075, ?p2=.035, or plagiarism knowledge, F(2, 107)=.343, p=.710, ?p2 =.008. The direction of the relation between teaching experience and the stance scores indicated that as teaching experience increased, the stance scores increased accordingly. In other words, the longer time a participant spent on tertiary teaching, the more lenient s/he would become toward plagiarism.

3.2. Results from the PPS

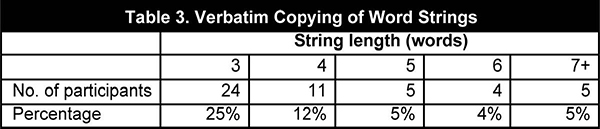

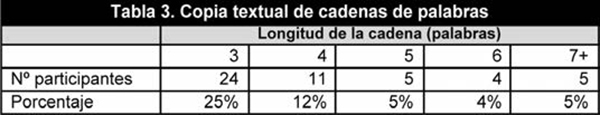

The PPS elicited paraphrases of the original paragraph from 96 of the 108 participants. Fifty-seven (59.38%) of them did not appropriate any strings of 3 or more words from the original. Thirty-nine (40.62%) produced paraphrases containing 3 or more consecutive words copied verbatim from the original. Table 3 presents the percentages of participants who copied word strings of different lengths. Most verbatim copying involved strings of 3 or 4 words, but 3 paraphrases appropriated unusually long word strings.

To find out what factors might influence the participants’ textual appropriation practices, the 96 teachers who completed the PPS were divided into two groups: those who did not appropriate any string of three or more words and those who did. Five 2-way Chi square tests were run to determine if there was any significant association between engagement in verbatim copying and teaching experience, educational attainment, overseas academic experience, plagiarism knowledge, and plagiarism stance, respectively. Participant groupings according to the four variables other than plagiarism stance followed the procedures described earlier. The grouping for plagiarism stance was done by putting those who gave average scores from 0 to 2 points, from above 2 to 4 points, and above 4 points into three separate groups. Four of the Chi square tests found no significant relationship: between teaching experience and textual appropriation practice, X2 (2, N= 96)= .732, p=.694; between educational attainment and textual appropriation practice, X2 (1, N= 96)=.029, p=.864; between plagiarism knowledge and textual appropriation practice, X2 (2, N=96)= 2.389, p= .303; and between plagiarism stance and textual appropriation practice, X2 (2, N=96)= 2.168, p= .338. A significant association was found between overseas academic experience and textual appropriation practice, X2 (1, N=96)=5.597, p= .018. These results indicated that those teachers who had studied in overseas universities were less likely to incorporate word strings from the original text.

4. Discussion and conclusions

4.1. Chinese university English teachers’ knowledge of plagiarism

Both the quantitative and qualitative results suggested that as a whole, the Chinese university EFL teachers in this study tended to understand plagiarism in a manner similar to that prevalent in Anglo-American academia. The knowledge scores yielded by the PKS showed that the participants as a group were able to correctly distinguish the plagiarized texts from correctly paraphrased ones. As demonstrated by the justifications given for their textual judgments, they considered plagiarism not only according to the extent to which the original text was changed, but also in terms of textual ownership and source attribution – perceptions closely associated with Anglo-American conceptions of plagiarism (Marshall & Garry, 2006; Pennycook, 1996; Scollon, 1995; Shi, 2004). The writing samples collected with the PPS further indicated that the great majority of the Chinese teachers paraphrased the given paragraph quite sufficiently, perhaps even more thoroughly than the American psychology professors in Roig (2001). With the exception of a few cases, the teachers had both the awareness and ability to sufficiently modify the original paragraph to avoid plagiarism.

Taken together, our results contradict the findings of some previous studies that Chinese culture is more accepting of plagiarism and that Chinese writers do not acknowledge sources explicitly (Bloch & Chi, 1995; Sapp, 2002; Shei, 2005). A plausible explanation of the contradictory findings lies in Flowerdew and Li’s (2007) observations that understandings of plagiarism in non-Anglo-American contexts are increasingly influenced by those in Anglo-American academia and that although the concept of plagiarism does not have a historical and ideological origin in China, perceptions of plagiarism should not be seen as culturally conditioned but constantly evolving as circumstances change (Lei & Hu, 2014). The growing penetration of Anglo-American ideas of plagiarism seems inevitable as long as English remains the academic lingua franca and Anglo-American dominance of the international academic community continues. Thus, the Chinese academic community is increasingly compelled to adapt its values and textual practices to face and navigate the Anglo-American dominance in order to participate in knowledge production in English-medium international journals.

4.2. Chinese university English teachers’ attitudes toward plagiarism

As reported in a previous section, the PKS data yielded a mean stance score of 1.73 on a scale of 0-10 points for recognized plagiarism, indicating clearly punitive attitudes held by the teachers toward what they perceived to be transgressive intertextuality. A sizeable number of teachers (n=15) took a zero tolerance approach by awarding no points to any paragraph they regarded as plagiarized. Such a harsh stance was not surprising in view of the teachers’ conception of plagiarism as a moral transgression, that is, an act of «stealing». It also showed that these teachers found plagiarism punishable and punished the perpetrators by marking them down. These results corroborate several recent studies (Hu & Lei, 2012; Lei & Hu, 2014, 2015) which reported a generally punitive attitude held by Chinese teachers and students toward perceived plagiarism, but contradict the conclusion of a number of earlier studies (Bloch & Chi, 1995; Deckert, 1993; Matalene, 1985; Pennycook, 1996; Sapp, 2002) which found Chinese students tolerant of and likely to engage in plagiaristic behaviors.

There are several plausible explanations of the contradictory findings. First, because the second group of studies mentioned above focused on Chinese students, it was possible that our teacher participants had a stronger sense of academic integrity and hence a greater obligation for ethical behaviors. Second, the EFL teachers in our study were likely to be much more knowledgeable about plagiarism as a result of their professional work than the students involved in the previous studies and, consequently, were able to recognize most instances of plagiarism. Third, it would be also reasonable to expect the university EFL teachers in our study to have stronger linguistic competence in English, when compared with the students in the previous studies, and therefore be able to use a greater variety of strategies for avoiding plagiarism (e.g., summarizing or paraphrasing a source thoroughly with appropriate attribution). In any case, our findings constitute new counterevidence against over-simplistic claims about Chinese writers being culturally more accepting of plagiarism (Sapp, 2002; Sowden, 2005).

4.3. Factors influencing Chinese university English teachers’ knowledge of and attitudes toward plagiarism

Unexpectedly, teaching experience was found to have a negative effect on teacher stance on plagiarism in this study. In other words, the longer a teacher worked at university, the more lenient s/he was toward plagiarism. Two explanations are possible. It was likely for some teachers to relax their moral stance on plagiarism over years of teaching service, perhaps, as a result of having seen too many cases of student plagiarism, having been frustrated by going through all the trouble of navigating red tape when dealing with student plagiarism, or having been resigned to the futility of individual efforts to stem student plagiarism. Another possibility is that teachers with longer years of teaching service were older, had had less exposure to Anglo-American conceptions of plagiarism when they were in graduate and teacher education programs and, as a result, understood plagiarism differently from their younger counterparts. Given the nature of our data, it was impossible to tell which explanation was valid. If the first explanation was closer to the reality, our finding revealed a truly disconcerting tendency. If the second explanation captured the truth, our finding pointed to a need to re-educate the educators regularly so as to update their understandings of plagiarism, strengthen their condemnatory attitudes toward plagiarism, and ensure consistent treatment of student plagiarism (Pecorari & Shaw, 2012).

Overseas academic experience was also found to be an influence on the teachers’ textual appropriation practice. That is, those teachers with overseas academic experience were less likely to copy strings of words verbatim from the original text in their paraphrases. This result was consistent with the findings of several studies (Deckert, 1993; Gu & Brooks, 2008; Song-Turner, 2008) which found a notable enculturational effect on the understandings of Anglo-American notions of plagiarism developed by Asian/Chinese students studying in ESL contexts, particularly those being immersed in Anglo-American settings. In our study, more than half of the teachers with overseas academic experience studied in a 1-year postgraduate program in Singapore. The program briefed new students about academic integrity at the program orientation, required them to sign the university’s code of academic conduct, included a range of extended written assignments which must be submitted through Turnitin for plagiarism checking, and had a course focused specifically on norms and conventions of English academic writing. Lecturers in the program emphasized the importance of avoiding plagiarism and taught the students how to reference and appropriate sources in academic writing. With such extensive socialization against plagiarism, it was not surprising that the overseas-trained teachers were more capable of paraphrasing the original paragraph in a plagiarism-free manner.

4.4. Limitations and recommendations

Given the huge population of EFL teachers in China and the nature of plagiarism as «a complex problem about student learning, compounded by a lack of clarity about the concept of plagiarism, and a lack of clear policy and pedagogy surrounding the issue» (Angelil-Carter, 2000: 2), this study only gives a glimpse into the issues discussed, and its findings are by no means conclusive. Further research is needed to develop a more robust and contextualized understanding of how plagiarism is understood and dealt with in Chinese higher education. To facilitate this research, we offer several recommendations regarding sampling and data collection.

Future research can adopt more systematic sampling strategies to recruit participants who work in universities of different types and prestige, and teach different types of students (e.g., English-language majors vs. non-majors; undergraduates vs. postgraduates) and courses (writing vs. non-writing). More detailed inclusion criteria would not only contribute to the representativeness of the sample but also facilitate comparisons between participants with different backgrounds. Future studies can also sample teachers from a range of disciplines so that disciplinary differences in relation to perceptions and practices of plagiarism can be investigated. In addition, not only teachers but also students and institutional administrators can be involved in the same investigation to explore plagiarism from different viewpoints and develop a multi-faceted picture.

As for data collection, it would be worthwhile to explore if adjustments to our instruments and their administration may have any influence on participants’ responses. For one thing, the instructions in the two instruments, especially the PKS, added several lines and might have caused extra burdens to some participants in an already demanding task. These instructions could be simplified or translated into Chinese so as to ensure better comprehensibility. For another, the PKS was placed before the PPS in the package of questionnaires sent out for the present study, and most participants presumably followed this order while completing the questionnaires. Undertaking the PKS (i.e., reading and judging the legitimacy of several rewritten versions of the same original paragraph) first might have alerted some participants to the importance of thoroughly paraphrasing an original text and caused them to make extra efforts in the subsequent PPS to keep clear of unacceptable paraphrasing practices. Future studies can explore whether reversing the order of the PKS and the PPS will generate writing samples exhibiting different textual appropriation practices. Large-scale investigations into institutional regulations on plagiarism, like those reported in Sutherland-Smith (2011) and Yamada (2003), can also be conducted to collect comprehensive and in-depth data on how Chinese universities are tackling the challenges posed by plagiarism.

Notes

References

Angelil-Carter, S. (2000). Stolen Language? Plagiarism in Writing. New York: Longman.

Benos, D., Fabres, J., & Farmer, J. (2005). Ethics and Scientific Publication. Advances in Physiology Education, 29(2), 59-74. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/advan.00056.2004

Bloch, J., & Chi, L. (1995). A Comparison of the Use of Citations in Chinese and English Academic Discourse. In D. Belcher & G. Braine (Eds.), Academic Writing in a Second Language: Essays on Research & Pedagogy (pp. 231-274). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Borg, E. (2009). Local plagiarism. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(4), 415-426. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930802075115

Chandrasegaran, A. (2000). Cultures in Contact in Academic Writing: Students’ Perceptions of Plagiarism. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 10, 91-113.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Deckert, G. (1993). Perspectives on Plagiarism from ESL Students in Hong Kong. Journal of Second Language Writing, 2(2), 131-148. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/1060-3743(93)90014-T

Eriksson, E.J., & Sullivan, K.P.H. (2008). Controlling Plagiarism: A Study of Lecturer Attitudes. In T.S. Roberts (Ed.), Student Plagiarism in an Online World: Problems and Solutions (pp. 23-36). Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference.

Flint, A., Clegg, S., & Macdonald, R. (2006). Exploring Staff Perceptions of Student Plagiarism. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 30(2), 145-156. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03098770600617562

Flowerdew, J., & Li, Y. (2007). Plagiarism and Second Language Writing in an Electronic Age. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 27, 161-183. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0267190508070086

Gu, Q., & Brooks, J. (2008). Beyond the Accusation of Plagiarism. System, 36(3), 337-352. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2008.01.004

Hirvela, A., & Du, Q. (2013). Why am I paraphrasing? Undergraduate ESL Writers’ Engagement with Source-based Academic Writing and Reading. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 12(2), 87-98. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2012.11.005

Hu, G., & Lei, J. (2012). Investigating Chinese University Students’ Knowledge of and Attitudes toward Plagiarism from an Integrated Perspective. Language Learning, 62(3), 813-850. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2011.00650.x

Keck, C. (2010). How do University Students Attempt to Avoid Plagiarism? A Grammatical Analysis of Undergraduate Paraphrasing Strategies. Writing & Pedagogy, 2(2), 193-222. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1558/wap.v2i2.193

Lei, J., & Hu, G. (2014). Chinese ESOL Lecturers’ Stance on Plagiarism: Does Knowledge Matter? ELT Journal, 68(1), 41-51. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/elt/cct061

Lei, J., & Hu, G. (2015). Chinese University EFL Teachers’ Perceptions of Plagiarism. Higher Education, 70(3), 551-565. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9855-5

Liu, D. (2005). Plagiarism in ESOL Students: Is Cultural Conditioning Truly the Major Culprit? ELT Journal, 59(3), 234-241. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/elt/cci043

Macdonald, R., & Carroll, J. (2006). Plagiarism: A Complex Issue Requiring a Holistic Institutional Approach. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 31(2), 233-245. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930500262536

Marshall, S., & Garry, M. (2006). NESB and ESB Students’ Attitudes and Perceptions of Plagiarism. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 2(1), 26-37.

Matalene, C. (1985). Contrastive Rhetoric: An American Writing Teacher in China. College English, 47(8), 789-808. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/376613

Maxwell, A., Curtis, G.J., & Vardanega, L. (2008). Does Culture Influence Understanding and Perceived Seriousness of Plagiarism. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 4(2), 25-40.

Park, C. (2003). In other (people's) Words: Plagiarism by University Students - Literature and Lessons. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 28(5), 471-488. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930301677

Pecorari, D. (2008). Academic Writing and Plagiarism: A Linguistic Analysis. London: Continuum.

Pecorari, D., & Petric, B. (2014). Plagiarism in Second-language Writing. Language Teaching, 47(3), 269-302. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0261444814000056

Pecorari, D., & Shaw, P. (2012). Types of Student Intertextuality and Faculty Attitudes. Journal of Second Language Writing, 21(2), 149-164. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2012.03.006

Pennycook, A. (1996). Borrowing Others' Words: Text, Ownership, Memory, and Plagiarism. TESOL Quarterly, 30(2), 201-230. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3588141

Pickard, J. (2006). Staff and Student Attitudes to Plagiarism at University College Northampton. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 31(2), 215-232. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930500262528

Rinnert, C., & Kobayashi, H. (2005). Borrowing Words and Ideas: Insights from Japanese L1 Writers. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 15(1), 31-56. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1075/japc.15.1.05rin

Roig, M. (2001). Plagiarism and Paraphrasing Criteria of College and University Professors. Ethics & Behavior, 11(3), 307-323. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327019EB1103_8

Sapp, D.A. (2002). Towards an International and Intercultural Understanding of Plagiarism and Academic Dishonesty in Composition: Reflections from the People’s Republic of China. Issues in Writing, 13(1), 58-79.

Scollon, R. (1995). Plagiarism and Ideology: Identity in Intercultural Discourse. Language in Society, 24(1), 1-28. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500018388

Shei, C. (2005). Plagiarism, Chinese Learners and Western Conventions. Taiwan Journal of TESOL, 2(1), 97-113.

Shi, L. (2004). Textual Borrowing in Second-language Writing. Written Communication, 21(2), 171-200. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0741088303262846.

Song-Turner, H. (2008). Plagiarism: Academic Dishonesty or ‘Blind Spot’ of Multicultural Education? Australian Universities’ Review, 50(2), 39-50.

Sowden, C. (2005). Plagiarism and the Culture of Multilingual Students in Higher Education abroad. ELT Journal, 59(3), 226-233. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/elt/cci042

Sutherland-Smith, W. (2011). Crime and Punishment: An Analysis of University Plagiarism Policies. Semiotica, 187, 127-139. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/semi.2011.067

Valentine, K. (2006). Plagiarism as Literacy Practice: Recognizing and Rethinking Ethical Binaries. College Composition and Communication, 58(1), 89-109.

Wheeler, G. (2009). Plagiarism in the Japanese Universities: Truly a Cultural Matter? Journal of Second Language Writing, 18(1), 17-29. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2008.09.004

Yamada, K. (2003). What Prevents ESL/EFL Writers from Avoiding Plagiarism? Analyses of 10 North-American College Websites. System, 31(2), 247-258. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(03)00023-X

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El plagio ha generado preocupaciones crecientes en el círculo académico en las últimas décadas. Aunque estudios anteriores han investigado el plagio del estudiante desde varias perspectivas, todavía hay poca investigación sobre cómo los profesores universitarios entienden el plagio y responden ante él, especialmente en contextos escritos en la enseñanza del inglés como lengua extranjera (EFL). Como expertos académicos y educadores de futuros académicos, los profesores universitarios desempeñan un papel clave en la formación de los estudiantes contra el plagio y en la defensa de la integridad académica. Sus conocimientos y actitudes con respecto al plagio no solo tienen una influencia crucial sobre las percepciones estudiantiles hacia el plagio, sino que también pueden proporcionar ideas sobre cómo las universidades resuelven el problema. El presente estudio pretende abordar este desequilibrio en la investigación sobre el plagio, centrándose en una muestra de 108 profesores de 38 universidades chinas. Basándose en datos cuantitativos y cualitativos obtenidos de juicios textuales y de redacciones, se examina: 1) si los docentes de EFL en universidades chinas comparten los conceptos angloamericanos del plagio; 2) qué postura tienen en los casos de plagio detectados; 3) qué factores pueden influir en sus comprensiones. Los resultados de este estudio problematizan la opinión popular y simplista de que los escritores chinos de inglés como lengua extranjera son indulgentes en cuanto al plagio, y señalan que las experiencias académicas y educativas tienen mucha influencia sobre sus percepciones y actitudes hacia el plagio.

1. Introducción

La redacción académica de nuevos textos se basa en el estado actual de los conocimientos a través de la incorporación de palabras e ideas de otras obras existentes (Pecorari & Petric, 2014). Este es un proceso regido por la costumbre (Pecorari, 2008) que un autor tiene que cumplir según prácticas disciplinariamente establecidas y compartidas para alejarse de las acusaciones de plagio. En las últimas décadas, la llegada de Internet y de diversas tecnologías de información y la comunicación han dado lugar a una riqueza cada vez más creciente de fuentes fácilmente disponibles y fáciles de plagiar (Hu & Lei, 2012). La incidencia del plagio va en aumento y ha generado gran preocupación en el mundo académico.

Para resolver el problema del plagio, es necesario mirar más allá de los síntomas y llegar a las causas fundamentales (Macdonald & Carroll, 2006). En esencia, todos los factores que contribuyen al plagio se reducen a una cierta deficiencia en los perpetradores, los cuales pueden carecer de la integridad académica, de la voluntad, de los conocimientos necesarios o de la habilidad lingüística para utilizar fuentes adecuadamente (Pecorari, 2008). Para autores de lenguas extranjeras (L2), los factores que contribuyen a ello pueden ser más complejos. El factor más discutido es el plagio en los contextos específicos de cultura. Frecuentemente se sugiere que las culturas difieren en la comprensión y aceptación que tienen del plagio (Bloch & Chi, 1995; Pennycook, 1996; Sapp, 2002; Scollon, 1995; Shei, 2005, Sowden, 2005). Por ejemplo, se citan a menudo las prácticas de alfabetización como la memorización y la imitación de los textos modelo que son comunes en culturas de herencia confuciana para explicar por qué los estudiantes chinos en particular y los estudiantes asiáticos en general, tienden a sostener diversos conceptos sobre el plagio (Bloch & Chi, 1995; Maxwell, Curtis, & Vardanega, 2008). Otros investigadores (Liu, 2005; Pecorari, 2008; Rinnert & Kobayashi, 2005), sin embargo, mantienen que las dificultades de los autores de L2 probablemente sean la falta de dominio adecuado del idioma, lo que puede causar inseguridad acerca de su uso del lenguaje y por lo tanto hacer que dependan demasiado de los textos originales. En estudios empíricos se han encontrado resultados contradictorios, especialmente en cuanto a cómo la endoculturación en la educación superior puede afectar al conocimiento y la postura sobre el plagio (Chandrasegaran, 2000; Deckert, 1993; Lei & Hu, 2014; Sapp, 2002; Wheeler, 2009).

En el mundo académico angloamericano, se considera que la documentación de fuentes y la paráfrasis son dos estrategias importantes para evitar el plagio (Park, 2003). Mientras que la primera es razonablemente sencilla y puede ser realizada con un entrenamiento adecuado, la última implica altas demanda del conocimiento del tema y la competencia lingüística (Keck, 2010), y por lo tanto, generalmente forma «una experiencia compleja y a menudo ardua para autores de L2» (Hirvela & Du, 2013: 87). Por otra parte, los investigadores y responsables académicos difieren mucho en los estándares sobre lo que se considera perífrasis. Mientras que algunos creen que para alejarse del plagio, no deben tener ningún rastro de la copia textual, incluso en cadenas de unas pocas palabras desde la obra original (Benos, Fabres, & Farmer, 2005; Roig, 2001; Shi, 2004), otros adoptan normas más laxas permitiendo la inclusión de más fuentes en una paráfrasis (Keck, 2006; Pecorari, 2008). Los estudios empíricos que examinen las prácticas de paráfrasis proveerán un mejor entendimiento de este tipo de prácticas que pueden considerarse aceptables entre los participantes.

Considerando el papel esencial que los profesores desempeñan en detectar y responder al plagio y educar para estar en su contra, los investigadores han prestado cada vez más atención a las percepciones del profesorado ante el plagio. En estudios anteriores se descubrió que los profesores diferían entre sí sobre qué constituye el plagio (Borg, 2009; Flint, Clegg, & Macdonald, 2006; Pickard, 2006), y que muchos tenían pocos conocimientos sobre las definiciones institucionales del plagio y que para evitar este no se enseñaba eficazmente (Eriksson & Sullivan, 2008). En dos de los escasos estudios realizados en el contexto chino, Lei y Hu (2014, 2015) encontraron que la mayoría de los profesores de EFL podían identificar las copias no reconocidas y paráfrasis anónimas como plagio y tenían actitudes condenatorias hacia el plagio detectado, sin embargo, la comprensión de la paráfrasis anónima, la cual se considera un tipo de plagio menos claro que la copia no reconocida, parecía divergente y ambivalente. Por otro lado, no se conoce hasta qué punto las percepciones de los profesores chinos sobre el plagio son diferentes o similares a aquellas ampliamente aceptadas en el ámbito académico angloamericano. La falta de este tipo de investigaciones es sorprendente cuando hay tantos estudios realizados sobre estudiantes chinos en universidades chinas y anglófonas (Bloch & Chi, 1995; Deckert, 1993; Matalene, 1985; Pennycook, 1996; Sapp, 2002; Shi, 2004; Valentine, 2006).

Para cubrir esta carencia, se realizó un estudio sobre una muestra de profesores chinos de EFL en varias universidades chinas para conocer si compartían normas y estándares angloamericanos sobre el plagio, y qué factores podrían haber influenciado su conocimiento y actitud. Planteamos como objetivo reunir evidencias empíricas que pudieran profundizar nuestra comprensión del plagio como un fenómeno discursivo e importante y poner a prueba las explicaciones culturales del plagio (Flowerdew & Li, 2007). Específicamente, se definieron las siguientes preguntas de investigación para guiar este estudio: ¿Hasta qué punto entienden el plagio los profesores de inglés en la universidad china? ¿Cuáles son sus actitudes hacia el plagio reconocido? ¿Qué factores influyen en sus conocimientos y actitudes sobre el plagio?

2. Metodología

2.1. Participantes

Para el reclutamiento de los participantes adoptamos una combinación de conveniencia y estrategias de muestreo de referencia. Contactamos con profesores en diferentes universidades chinas, les invitamos a participar en el estudio, y les pedimos su ayuda en el reclutamiento de colegas. Finalmente se involucraron 108 profesores de inglés como lengua extranjera de 38 universidades ubicadas en diferentes regiones chinas. La tabla 1 resume la información demográfica relacionada con estos participantes. Asimismo la muestra oscilaba entre los 25 y los 50 años de edad (M= 34.33, SD=4.99) y estaba compuesta predominantemente por profesoras, reflejando las distribuciones típicas del género de la disciplina dominada por las mujeres en las universidades chinas. Constaba de profesores con mucha experiencia y también noveles. De los 107 encuestados que suministraron información sobre su antigüedad en la enseñanza, se reflejó un promedio de 9,47 años (SD=5.39; gama=1-27). Una gran mayoría de participantes tenía el grado de maestría y tenía una categoría académica de profesor. Un poco menos de la mitad de participantes tenía experiencia académica en el extranjero, es decir, había estudiado en universidades en países anglófonos o en ambientes de inglés como segunda lengua (ESL), tales como Hong Kong y Singapur, donde se adoptan las nociones angloamericanas del plagio.

2.2. Instrumentos

Para la recolección de los datos fueron utilizados dos instrumentos: la Encuesta de Conocimiento de Plagio (PKS) y la Encuesta de Prácticas de Paráfrasis (PPS). Ambos instrumentos fueron adaptados de Roig (2001). El PKS tiene como objetivos explorar si los participantes reconocen la paráfrasis insuficiente como forma de plagio, establecer los criterios adoptados por ellos para la determinación, e investigar sus actitudes (p.ej., punitiva o indulgente) hacia los casos reconocidos del plagio. La prueba consistía en un párrafo original de dos oraciones y seis versiones reescritas de las mismas. Las cuatro primeras fueron progresivas, pero insuficientemente parafraseadas de la original y por tanto fueron objeto de plagio, mientras que las dos últimas fueron adecuadamente parafraseadas y estaban libres de plagio. Según Roig (1997), cuatro profesores estadounidenses convalidaron independientemente el instrumento y estuvieron de acuerdo con la descripción del plagio de las seis versiones escritas. Pedimos a los participantes que compararan cada versión reescrita con el párrafo original y eligieran una de las tres opciones previstas (es decir, plagiado, no plagiado, o no se puede determinar), y que aportaran posteriormente razones para su opción. Con el fin de conocer las actitudes de los participantes hacia la identificación del plagio, añadimos una escala de estimación de 0 a 10 puntos en el PKS original y les dijimos que estimaran cada versión reescrita según la presencia y la gravedad del plagio: el caso más grave podría ser penalizado con un cero, y para un párrafo bien parafraseado se podría poner la nota más alta.

El PPS describía una situación donde los participantes tenían que parafrasear el siguiente párrafo corto de un artículo periodístico sobre astrología, según el sistema de puntuación escogido por Roig (2001): «Si alguna vez te han hecho tu dibujo astrológico, te sorprendería su exactitud. Leyéndolo cuidosamente, descubrirás que la mayoría de las cualidades se describen de forma aduladora. Sin embargo, cuando tu personalidad se describe positivamente es difícil reconocer que dicha descripción carece de veracidad» (Coon, 1995: 29).

Este instrumento generó muestras auténticas de redacción después de pedirles que parafrasearan el párrafo de manera que mostrase que no estaba plagiado. También se requería que rellenaran un formulario con información personal con datos sobre género, edad, experiencia educativa, experiencia docente, número de publicaciones académicas, además de los tipos de estudiantes y cursos que generalmente enseñaban. Se recogió este tipo de información porque estudios anteriores (Hu & Lei, 2012; Lei & Hu, 2014, 2015) sugirieron que podría tener un impacto en el conocimiento y actitud de los participantes sobre el plagio, además de sus prácticas de paráfrasis.

2.3. La codificación de datos y el análisis

Con el PKS se recogieron dos tipos de notas: las de conocimiento del plagio (notas de conocimiento de ahora en adelante), y las de postura o actitud hacia el plagio (notas de actitud de ahora en adelante). Las notas de conocimiento se calcularon según Roig (2001). Para cada participante se asignó un punto para cada versión reescrita correctamente identificada, dos puntos para cada versión no identificada (incluyendo tanto los casos de «no se puede determinar» como los casos en que un participante no podía opinar), y tres puntos para la versión incorrectamente identificada. El participante que identificaba correctamente todas las versiones reescritas obtenía una puntuación perfecta de seis puntos, en el caso contrario obtenía 18 puntos. Por lo tanto, las notas más bajas podían indicar un mejor conocimiento del plagio y de la paráfrasis. Se obtuvieron las puntuaciones sobre la actitud calculando el promedio de las estimaciones dadas por cada participante para los párrafos reescritos que él o ella consideraba plagiados (sin considerar si el párrafo fue diseñado como un caso del plagio o una paráfrasis apropiada). Cuanta más alta fuera la nota sobre actitud, más indulgente sería el participante hacia el plagio reconocido. Se analizaron con SPSS (versión 23.0) las notas obtenidas para conseguir datos estadísticos descriptivos e inferenciales necesarios para responder a nuestras preguntas de investigación.

El PKS también generó datos cualitativos con las justificaciones escritas por los participantes sobre sus juicios y estimaciones de las versiones reescritas. El segundo autor leía repetidamente estas justificaciones y las analizaba iterativamente para identificar los factores que consideraban al juzgar y estimar los párrafos reescritos. Se desarrolló entonces un esquema de codificación basado en este análisis y se utilizó para recoger los criterios adoptados por los participantes para evaluar las versiones reescritas. Para asegurar la fiabilidad de la codificación, un estudiante graduado la utilizó independientemente para codificar un subconjunto de datos seleccionados aleatoriamente, y el acuerdo de la codificación fue del cien por cien.

El segundo autor llevó a cabo la codificación de datos de PPS que consistió en identificar cadenas de tres o más palabras consecutivas en las paráfrasis que se apropiaron del párrafo original. No fue necesario un segundo codificador porque la codificación no involucraba juicios subjetivos.

3. Resultados

3.1. Resultados del PKS

Se analizaron las puntuaciones de conocimientos, descriptiva e inferencialmente. Se calcularon el rango, el promedio y la moda para medir hasta qué punto los profesores chinos como grupo identificaban los casos de plagio. El promedio fue de 7,51 (SD=1.488; rango=6-12), indicando que los 108 participantes fueron capaces de identificar correctamente la mayoría de los párrafos reescritos. En particular, 43 profesores (40% del total de la muestra efectiva) tuvieron una puntuación perfecta de 6, demostrando un conocimiento satisfactorio y apropiado del plagio y de la paráfrasis. Para mostrar la precisión en que los participantes identificaron cada versión reescrita, se calculó el porcentaje de respuestas a cada categoría (es decir, plagiado, no plagiado, no se puede determinar) cuyos resultados se muestran en la tabla 2. En concreto, ninguna de las versiones reescritas fue juzgada con los consensos perfectos. Para las cuatro primeras, como la extensión de la reformulación aumentó, los porcentajes de identificaciones correctas bajaron, mientras que los porcentajes de las incorrectas y de las que no se puede determinar subieron correspondientemente. Este modelo indicó claramente que la dificultad en la identificación del plagio aumentó con la extensión del cambio hecho para el texto original; también implicó la existencia de diferentes criterios para el plagio y la paráfrasis apropiada incluso entre profesores de la misma disciplina.

Entre los 108 participantes, 102 ofrecieron justificaciones escritas para sus juicios con respecto a las versiones reescritas. Se reveló en un análisis de estas justificaciones que ellos utilizaron tres criterios al evaluar los párrafos. En primer lugar, muchos basaron sus comentarios por la extensión en que cambiaba el párrafo original. Alrededor del 65% de los participantes señalaron que para evitar acusaciones de plagio, se tenía que reescribir el párrafo original para cambiar su estilo y estructura, como lo demuestran las siguientes justificaciones:

• El párrafo reescrito está completamente parafraseado, los alumnos parafrasean el texto original tanto en el sentido como en la estructura de la frase (versión 5 de reescrito).

• Este es plagio porque la estructura de las frases que se utilizan son las mismas o similares al texto original (versión 2 de reescrito).

• Se considera sin duda plagio porque solo hay cambio en el orden de palabras sin parafrasear nada (versión 1 de reescrito).

Un segundo criterio se interesó por el formato correcto de la cita. Aunque en las instrucciones del PKS se les pidió a los participantes que asumieran la inclusión de una cita adecuada para cada versión reescrita, muchos todavía enfatizaron la importancia de reconocer la fuente en el formato correcto, como se puede ver en las citas siguientes:

• El párrafo reescrito indica claramente el resultado de otro investigador sin aclarar de dónde viene concretamente (versión 4 de reescrito).

• El autor ha mencionado el origen del resultado de la investigación y ha parafraseado el párrafo. Será mejor aclarar el nombre del investigador original (versión 5 de reescrito).

• En el texto académico, es indispensable mencionar quién da la opinión (versión 5 de reescrito).

Otra consideración que los participantes tuvieron en cuenta fue si se utilizaban ciertas palabras o expresiones para indicar que el escritor estaba informando sobre ideas de otra persona, como lo ilustran las siguientes citas:

• Esto no es plagio por la aclaración al citar a otro investigador (versión 5 de reescrito).

• El autor indica que está citando el resultado de otro investigador utilizando la frase «según X investigador» (versión 4 de reescrito).

Se utilizó el Análisis de la Varianza de tres vías (3-way ANOVA) para evaluar el impacto potencial de la experiencia docente, la experiencia académica en el extranjero, y los logros educativos sobre las notas de conocimientos. Se dividieron los participantes en tres grupos según sus años de experiencia docente (1-7, 8-14, 15+) y dos grupos según sus titulaciones académicas más altas (Licenciatura, Máster y Doctorado). Quedaron 107 casos para el análisis después de eliminarse un caso en el que faltaba el valor en la experiencia docente. El análisis reveló que la experiencia docente no influía en las notas de conocimiento, F(3, 107)=.089, p=.966, ?p2=003, así como tampoco la experiencia académica en el extranjero, F(1, 107)= .564, p=.454, ?p2=.006, o los logros educativos, F(1, 107)=.147, p=.702, ?p2=.002. No había ninguna interacción notable entre la experiencia docente y los logros educativos, F(2, 107)=.450, p=.639, ?p2= .009, entre la experiencia docente y la experiencia académica en el extranjero, F(2, 107)=.882, p= .417, ?p2=.018, entre los éxitos educativos y la experiencia académica en el extranjero, F(1, 107)= .018, p=.892,?p2=.000, o entre las tres variables, F(1, 107)=.731, p=.398, ?p2=.008. Los tamaños del efecto indicaron que ninguna de las variables independientes o las interacciones alcanzó el valor propuesto por Cohen (1988) para un efecto pequeño (es decir, ?p2=.02).

Se obtuvieron el rango, el promedio, y la moda de las notas de actitud para medir cómo reaccionó el grupo de profesores frente a casos identificados de plagio. Los 108 encuestados tuvieron un promedio de 1,73 (gama=0-5.17), que indicaba sus actitudes punitivas en general. Aproximadamente el 14% de los participantes creyó que no debían poner ningún punto para un texto plagiado, y otro 67,6% pusieron una estimación media de menos de dos puntos. Estos resultados fueron coherentes con una comprensión del plagio como un acto de robo, como se revela en las citas siguientes:

• La primera oración está sacada del texto original (versión 6 de reescrito).

• El párrafo reescrito ha mencionado la cita del resultado de otro investigador, pero la mayor parte de las oraciones son robadas del texto original (versión 4 de reescrito).

• El re-escritor cambia el orden de las frases sin indicar quién es el autor. Este acto se considera como robo, tanto del lenguaje como también de las ideas (versión 1 de reescrito).

Se realizó el ANOVA a tres vías para determinar posibles influencias sobre la puntuación de la actitud, con las tres variables independientes como la experiencia docente, la experiencia académica en el extranjero, y los conocimientos del plagio. Se dividieron los participantes en tres grupos según sus notas de conocimientos (es decir, 6 puntos, 7-9 puntos y 10+). El ANOVA reveló que la experiencia docente influenciaba a las otras variables, F(3, 107)=3.306, p=.024, ?p2=.099, pero la experiencia académica en el extranjero no, F(1, 107)=3.245, p=.075, ?p2=.035, tampoco los conocimientos del plagio, F(2, 107)= .343, p=.710, ?p2=.008. La dirección de la relación entre la experiencia docente y las puntuaciones sobre la actitud indicó que cuando aumentaba la experiencia docente, subían las puntuaciones sobre la actitud. En otras palabras, cuanto más tiempo pasaba un participante en la enseñanza superior, más indulgente sería hacia el plagio.

3.2. Resultados del PPS

El PPS obtuvo las paráfrasis del párrafo original de 96 de los 108 participantes, 57 de ellos (59,38%) no se apropiaron de ninguna cadena de tres o más palabras del original. Los 39 (40,62%) produjeron las paráfrasis que contenían tres o más palabras consecutivas textualmente copiadas del párrafo original. La tabla 3 presenta los porcentajes de los participantes que copiaron cadenas de palabras de diversas longitudes. La mayoría de las copias textuales consistieron en cadenas de tres o cuatro palabras, pero tres paráfrasis inusualmente se apropiaron de largas cadenas de palabras del original.

Para saber qué factores pueden influir en las prácticas de apropiación textual de los participantes, se dividieron los 96 maestros que completaron el PPS en dos grupos: aquellos que no se apropiaron de ninguna cadena de tres o más palabras y aquellos que sí lo hicieron. Se ejecutaron cinco pruebas de Chi Cuadrado a 2 vías (2-way Chi square) para determinar si había asociaciones significativas entre el compromiso en la copia textual y la experiencia docente, los logros educativos, la experiencia académica en el extranjero, el conocimiento del plagio, y la actitud ante el plagio, respectivamente. Las agrupaciones de los participantes de conformidad con las cuatro variables aparte de la actitud ante el plagio siguieron los procedimientos anteriormente descritos. Se realizó la agrupación para la actitud ante el plagio poniéndoles a aquellos que dieron notas medias de 0 a 2 puntos, de 2 a 4 puntos, y más de 4 puntos, en tres grupos separados. En las cuatro pruebas de Chi Cuadrado no se descubrió ninguna relación significativa: entre la experiencia docente y la práctica de apropiación textual, X2 (2, N=96)=732, p=.694; entre los logros educativos y la práctica de apropiación textual, X2 (1, N=96) =.029, p=.864; entre el conocimiento del plagio y la práctica de apropiación textual, X2 (2, N=96) =2.389, p=.303; y entre la actitud ante el plagio y la práctica de apropiación textual, X2 (2, N=96)= 2.168, p=.338. Se halló una asociación significativa entre la experiencia académica en el extranjero y la práctica de apropiación textual, X2 (1, N=96)= 5.597, p=.018. Estos resultados indicaron que era menos probable que los profesores que habían estudiado en universidades extranjeras incorporaran palabras del texto original.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

4.1. El conocimiento del plagio de profesores de inglés en universidades chinas

Los resultados cuantitativos y cualitativos implicaron que, en conjunto, los profesores tendían a entender el plagio de una manera similar a la que predomina en el mundo académico angloamericano. Las notas de conocimientos producidas por el PKS demostraron que como grupo, los participantes fueron capaces de distinguir correctamente los textos plagiados de los correctamente parafraseados. Como lo demostraron las justificaciones dadas para sus juicios textuales, ellos consideraron el plagio no solo según la extensión en la que cambiaba el texto original, sino también en términos de propiedad textual y la atribución de fuentes, percepciones estrechamente relacionadas con los conceptos angloamericanos de plagio (Marshall & Garry, 2006; Pennycook, 1996; Scollon, 1995; Shi, 2004). Las muestras de redacción obtenidas con el PPS indicaron además que la gran mayoría de los profesores chinos parafraseaba bastante el párrafo ofrecido, quizás todavía más a fondo que los profesores norteamericanos de psicología en Roig (2001). Excepto algunos casos, los profesores tuvieron la conciencia y la capacidad de modificar suficientemente el párrafo original para evitar el plagio.

En conjunto, nuestros resultados contradicen los hallazgos de algunos estudios anteriores que afirman que en la cultura china es más aceptable el plagio y que los autores chinos no reconocen explícitamente las fuentes (Bloch & Chi, 1995; Sapp, 2002; Shei, 2005). Una explicación plausible sobre los resultados contradictorios está en las observaciones de Flowerdew y Li (2007), en cuanto a que la comprensión del plagio en los ambientes no angloamericanos está cada vez más influenciada por el marco académico angloamericano, y que aunque el concepto del plagio no tiene un origen histórico e ideológico en China, las percepciones del plagio no deben ser consideradas como culturalmente condicionadas, sino que están constantemente evolucionando debido a que cambian las circunstancias (Lei & Hu, 2014). La creciente penetración de las ideas angloamericanas del plagio parece inevitable siempre que el inglés siga siendo la lengua vehicular y el dominio angloamericano de la comunidad académica internacional continúe. Por lo tanto, la comunidad académica china se ve cada vez más obligada a adaptar sus valores y prácticas textuales para hacer frente al dominio angloamericano y manejarlo con el fin de participar en la producción de conocimientos en las publicaciones internacionales de habla inglesa.

4.2. Actitudes sobre el plagio de profesores de inglés en universidades chinas

Como se ha mostrado anteriormente, los datos del PKS produjeron una nota media sobre la actitud de 1,73, en una escala de 0-10 puntos, para el plagio reconocido, indicando claramente las actitudes punitivas mostradas por los docentes hacia la intertextualidad transgresiva que percibían. Un número considerable de profesores (n=15) tomó una estrategia de tolerancia cero no otorgando ningún punto a los párrafos que consideraban plagiados. No fue sorprendente una postura tan dura en profesores para los que el plagio era como una transgresión moral, es decir, un acto de «robo». También demostraron que lo consideraban un acto condenable, y castigaron a los perpetradores con una nota muy baja. Estos resultados corroboran varios estudios recientes (Hu & Lei, 2012; Lei & Hu, 2014, 2015) que dan a conocer una actitud generalmente punitiva mostrada por los profesores chinos y los alumnos hacia el plagio percibido, pero contradicen las conclusiones de una serie de estudios anteriores (Bloch & Chi, 1995; Deckert, 1993; Matalene, 1985; Pennycook, 1996; Sapp, 2002), donde se demostró que los estudiantes chinos eran indulgentes y probablemente se comprometían con la conducta del plagio.

Hay varias explicaciones plausibles sobre los resultados contradictorios. En primer lugar, como el segundo grupo de estudios anteriormente mencionado se concentraba en estudiantes chinos, es posible que nuestros profesores participantes tuvieran un sentimiento más fuerte sobre la integridad académica y por eso, un mayor compromiso con los comportamientos éticos. En segundo lugar, posiblemente nuestros participantes tenían más conocimientos sobre el plagio que los estudiantes debido a su trabajo profesional, de modo que eran capaces de reconocer la mayoría de los casos de plagio. En tercer lugar, también sería razonable esperar que nuestros participantes tuvieran mayores competencias lingüísticas en el manejo del idioma inglés que los estudiantes, y por lo tanto serían capaces de usar una mayor variedad de estrategias para evitar el plagio (p.ej. cuando resumen o parafrasean una fuente completamente con la atribución adecuada). En cualquier caso, nuestros resultados constituyen una nueva evidencia contra las afirmaciones simplistas de que los autores chinos culturalmente aceptan más el plagio (Sapp, 2002; Sowden, 2005).

4.3. Factores que influyen en el conocimiento y actitudes hacia el plagio

Inesperadamente, se descubrió en este estudio que la experiencia docente tenía un efecto negativo en la actitud del profesor sobre el plagio. En otras palabras, cuanto más tiempo llevaba un profesor trabajando en la universidad, más indulgente era hacia el plagio. Hay dos explicaciones posibles. Es probable que algunos profesores relajen su postura moral sobre el plagio a lo largo de su trayectoria docente, tal vez, debido a haber visto demasiados casos de plagio en estudiantes, se hayan frustrado por comprobar todos los problemas de gestión burocrática en casos de plagio, o se hayan resignado a la inutilidad de los esfuerzos individuales por detenerlo. Otra posibilidad es que los profesores con muchos años de experiencia son mayores, y han tenido menor exposición a los conceptos angloamericanos del plagio cuando eran estudiantes y posteriormente profesores y, por eso, comprenden de manera distinta el plagio de sus homólogos más jóvenes. Considerando la naturaleza de nuestros datos, es imposible decir qué explicación es válida. Si la primera está más cerca de la realidad, nuestros resultados revelaron una tendencia verdaderamente desconcertante. Si la segunda es la razón imperante, nuestra conclusión señaló una necesidad de reeducar regularmente a los docentes para actualizar sus conocimientos sobre el plagio, reforzar sus actitudes condenatorias hacia el plagio, y garantizar un tratamiento consistente del plagio de los estudiantes (Pecorari & Shaw, 2012).

Se descubrió que la experiencia académica en el extranjero también influenciaba las prácticas de la apropiación textual. Es decir, los profesores con esta experiencia tenían menos probabilidades de copiar palabras textuales desde el texto original en sus paráfrasis. Este hallazgo fue coherente con los resultados de varios estudios (Deckert, 1993; Gu & Brooks, 2008; Song-Turner, 2008) que descubrieron un efecto notable de la endoculturación sobre los entendimientos desarrollados del plagio de las nociones angloamericanas por estudiantes asiáticos o chinos que estudiaban en un ambiente de inglés como segunda lengua, particularmente aquellos sumergidos en valores angloamericanos. En nuestro estudio, más de la mitad de estos profesores estudió en un programa de posgrado de un año en Singapur. El programa enseñó a los nuevos estudiantes, durante la orientación académica del programa, sobre la integridad académica, les exigía que firmaran el código de la universidad sobre conducta académica, incluía una serie de tareas amplias de redacción que debían ser entregadas a través de Turnitin para la comprobación del plagio, y tenía un curso centrado específicamente en las normas y convenciones de la redacción académica del inglés. Los profesores del programa enfatizaron la importancia de evitar el plagio y les enseñaron cómo citar y apropiarse de fuentes en la redacción de textos académicos. Con una socialización tan amplia como esta contra el plagio, no fue sorprendente que los profesores que habían estudiado en el extranjero tuvieran más capacidad para parafrasear el párrafo original libre de plagio.

4.4. Limitaciones y recomendaciones

Teniendo en cuenta la gran cantidad de profesores de EFL en China y la naturaleza del plagio como «un problema complejo sobre el aprendizaje de los estudiantes, compuesto de una falta de claridad sobre el concepto de plagio, y una escasez de reglas claras y la pedagogía en torno a este tema» (Angelil-Carter, 2000: 2), este estudio tan solo se centra en los temas discutidos, y sus resultados no pretenden ser decisivos. Se necesitan investigaciones más profundas para desarrollar una comprensión más robusta y contextualizada sobre cómo se entiende el plagio y se soluciona en la educación superior china. Para facilitar este trabajo, ofrecemos varias recomendaciones con respecto a la selección de muestras y recogida de datos.

En investigaciones futuras, se pueden seleccionar muestras más sistemáticas para reclutar a los participantes que trabajan en universidades de diferentes tipos y prestigio, y enseñan a diferentes tipos de alumnos (por ejemplo, carreras con especialidad en inglés frente a carreras sin esta especialidad; estudiantes universitarios de pregrado vs. a los postgraduados) y cursos (con redacción o sin redacción). Los criterios de esta inclusión detallada no solo contribuirían a la representatividad de la muestra, sino que también facilitarían las comparaciones entre los participantes de distintos ambientes. Los futuros estudios también pueden tomar muestras de los profesores desde diversas disciplinas para que se investiguen las diferencias disciplinarias en relación con las percepciones y prácticas de plagio. Además, no solo los profesores sino también los estudiantes y administradores institucionales pueden participar en la misma investigación con el fin de explorar el plagio desde diferentes puntos de vista y desarrollar una imagen desde diferentes perspectivas.

En cuanto a la recolección de datos, valdría la pena explorar si las adaptaciones de nuestros instrumentos y su administración influirían en las respuestas de los participantes. Por una parte, las instrucciones en los dos instrumentos, especialmente el PKS, operaba varias líneas y podía haber causado en algunos participantes cargas extras en una tarea que ya era exigente. Dichas instrucciones podrían ser simplificadas o traducidas al chino para asegurar una mejor comprensión. Por otra parte, se aplicó el PKS antes del PPS, y la mayoría de los participantes presuntamente siguió este orden al completar los cuestionarios. Comenzando primero con el PKS (es decir, leer y juzgar la legitimidad de varias versiones reescritas del mismo párrafo original), podría haber alertado a algunos participantes sobre la importancia de parafrasear plenamente un texto original y haber hecho que tuvieran los esfuerzos extras en el PPS siguiente para estar libres de prácticas inaceptables de paráfrasis. Los futuros estudios pueden explorar si la inversión del orden del PKS y el PPS genera muestras de redacción que demuestran las diferentes prácticas de la apropiación textual. También se pueden hacer investigaciones a gran escala sobre los reglamentos institucionales respecto al plagio, como ya evidenciaban Sutherland-Smith (2011) y Yamada (2003), para recopilar datos completos y detallados sobre cómo se enfrentan las universidades chinas a los desafíos generados por el plagio.

1 For example, a quotation is expected in Anglo-American writing conventions to be attributed to the original author regardless of how familiar the quotation or the author is to the intended readership. However, such attribution is considered unnecessary and even condescending to a knowledgeable readership by many a Chinese writer (Bloch & Chi, 1995).

Referencias

Angelil-Carter, S. (2000). Stolen Language? Plagiarism in Writing. New York: Longman.

Benos, D., Fabres, J., & Farmer, J. (2005). Ethics and Scientific Publication. Advances in Physiology Education, 29(2), 59-74. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/advan.00056.2004

Bloch, J., & Chi, L. (1995). A Comparison of the Use of Citations in Chinese and English Academic Discourse. In D. Belcher & G. Braine (Eds.), Academic Writing in a Second Language: Essays on Research & Pedagogy (pp. 231-274). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Borg, E. (2009). Local plagiarism. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(4), 415-426. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930802075115

Chandrasegaran, A. (2000). Cultures in Contact in Academic Writing: Students’ Perceptions of Plagiarism. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 10, 91-113.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Deckert, G. (1993). Perspectives on Plagiarism from ESL Students in Hong Kong. Journal of Second Language Writing, 2(2), 131-148. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/1060-3743(93)90014-T

Eriksson, E.J., & Sullivan, K.P.H. (2008). Controlling Plagiarism: A Study of Lecturer Attitudes. In T.S. Roberts (Ed.), Student Plagiarism in an Online World: Problems and Solutions (pp. 23-36). Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference.

Flint, A., Clegg, S., & Macdonald, R. (2006). Exploring Staff Perceptions of Student Plagiarism. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 30(2), 145-156. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03098770600617562

Flowerdew, J., & Li, Y. (2007). Plagiarism and Second Language Writing in an Electronic Age. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 27, 161-183. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0267190508070086

Gu, Q., & Brooks, J. (2008). Beyond the Accusation of Plagiarism. System, 36(3), 337-352. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2008.01.004

Hirvela, A., & Du, Q. (2013). Why am I paraphrasing? Undergraduate ESL Writers’ Engagement with Source-based Academic Writing and Reading. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 12(2), 87-98. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2012.11.005

Hu, G., & Lei, J. (2012). Investigating Chinese University Students’ Knowledge of and Attitudes toward Plagiarism from an Integrated Perspective. Language Learning, 62(3), 813-850. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2011.00650.x

Keck, C. (2010). How do University Students Attempt to Avoid Plagiarism? A Grammatical Analysis of Undergraduate Paraphrasing Strategies. Writing & Pedagogy, 2(2), 193-222. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1558/wap.v2i2.193

Lei, J., & Hu, G. (2014). Chinese ESOL Lecturers’ Stance on Plagiarism: Does Knowledge Matter? ELT Journal, 68(1), 41-51. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/elt/cct061