Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

New democratic participation forms and collaborative productions of diverse audiences have emerged as a result of digital innovations in the online access to and consumption of news. The aim of this paper is to propose a conceptual framework based on the possibilities of Web 2.0. Outlining the construction of a “social logic”, which combines computer and communicative logics, the conceptual framework is theoretically built to explore the evolution of news consumption from a pure circulation of designed products towards a global conversation of proactive news designers. Then, the framework was tested using an empirical database built by the Pew Research Centre, which investigates the future of the news industry, through a large-scale survey with adults. Results show significant differences (by age, gender and educational level) in the forms of participation, access and consumption of news. However, whilst immersed in the culture of Web 2.0 there is a low-level of user participation in news production; far from being proactive news designers, findings suggest that citizens are still located in the lower participatory levels of our conceptual framework. Conclusions suggest there is a need for media education providers to carry out training initiatives according to the social logic possibilities through proposed guidelines.

1. Introduction

The emergence of a digital landscape is increasing the ability of citizens to consume news in many different ways. The use of online media is also changing the way in which news is being produced. It is increasingly being argued that there is blurring of the barriers separating news producers (traditionally, news agencies and journalist) and news users (a diversity of audiences). Thereby, the activities of news production and consumption also merge together. A new set of terms is now emerging such as that of “pro-sumer” (Gillmor, 2006) and “prod-usage” (Bruns, 2014). These imply audiences having a significant role and contribution to make in the production of news content. Furthermore, users will be empowered to participate in the process of news selection, design and distribution. This change adds a democratic role for users, which in turn can be empowered via the collaborative participation means of Web 2.0.

Interestingly, there are two main interpretations of the Web 2.0 phenomenon (Kümpel, Karnowski, & Keyling, 2015; Papacharissi, 2015). On the one hand, Web 2.0 is presented as an interactive platform. O’Reilly (2005) describes the platform as an architecture of participation. Basically, it makes numerous tools and services available to promote social interaction. On the other hand, it is suggested that Web 2.0 is a social enabler, that it is creating greater cultural and societal transformation through changing the way news are being produced and consumed. Jenkins (2009) notes that the participation that characterizes the news mediatoday is cultural. As a result, new practices, norms, values and constructs are evolving into “Culture 2.0”. This includes new digital participative behaviours for managing news (Beckett, 2008). One implication is that users become news producers and/or news prosumers (García-Ruiz, 2013; Pérez-Rodríguez & Delgado, 2012; González-Fernández, Gozálvez, & Ramírez-García, 2015).

This paper suggests that participative behaviours may be part of a new logic, which is entitled as: “social logic”. This is part of a wider digital landscape movement crucially altering the traditional ways of producing and consuming news. Social logic confronts us with the innovative possibilities of increased connectivity and participation that presupposes a major involvement of the audience in the use of the news media. We investigate the extent to which the social logic is leading citizens to become more involved in the design and production of news content. The aim of this paper therefore is to investigate the influence of this emerging social logic on the news industry production. In meeting this aim, we first develop a conceptual framework of news “prod-design”. Then, using the framework as an analytical tool, it was tested with empirical data drawn from different socio-economic cohorts of users. The intention is to theoretically advance categories of the framework and provide more detailed understanding of the social logic paradigm. It is here believed that this will make it possible to discover whether the theory of social logic has been implemented in the news industry. Are citizens actually in practice designing their news content with professional media organisations? If not, are there still barriers erected by the news industry preventing pro-design? Or is it simply a case that different groups (by age or education level) have little motivation or interest in participation? From the analysis and discussion, we conclude with important guidelines to be included in the educational agenda on social logic and media literacy.

2. Social Logic: a conceptual framework

As stated by Jönsson & Örnebring (2011), Web 2.0 offers an unprecedented range of possibilities encouraging much greater levels of user involvement in the news production process. However, if the audience is to change its role from purely a consumer to that of a news producer, then there are still many barriers and challenges to be overcome. In the 2.0 context, it is necessary to find a more sustainable framework that enables users to function as a genuine news producer. They would be central to value adding activity. Furthermore, this would work beyond their current peripheral role as a User Generated Content supplier (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010; Susarla, Oh, & Tan, 2012). Therefore, a clearer understanding of news sharing and producing needs to be developed if educators are to keep up with their evolving social media ecology (Kümpel, Karnowski, & Keyling, 2015).

There is a constant improvement on the Web 2.0 news channels and innovative interacting tools. This includes the dimensions for understanding the participatory processes in online environments. We have gone beyond the period of media convergence. As stated by Siapera (2011), this period was the result of a convergence between the characteristic of a “computational logic” –the logic of the computers– and the characteristic of the “communicative logic”– the logic of the media.

This study proposes that together with these two logics there is a third logic, the “social logic” (Hernández-Serrano, Greenhill, & Graham, 2015), which is the logic for the Web 2.0. The innovative possibilities offered by Web 2.0 places the user at the beginning of a new logic. There is a strong emphasis on the social component and how we are connected online with other users. This is a new logic from which some societal practices can be translated while other new practices and interpretations of the practices are being altered. In the context of the treatment of news, the social logic impacts into the everyday experiences of the audience. This is done by introducing innovative ways of interacting with news producers and with other news users. As stated by Nel & Westlund (2013), participation within the social logic is challenging the traditional logics of “professional” journalism and control. Essentially, the social logic creates opportunities for news media plurality and it is paving the way for a much more innovative era in the news media sector.

2.1. What social logic adds to news production?

The social era calls the ownership of news production into question. Considering that journalists and citizens are closer than ever before in being able to report the news, theoretically we now all have the means of production to be newsmakers (Gillmor, 2006). This is contributing to strategic tension between professional control and levels of open participation in news production (Lewis, 2012). The informative authority of new companies is at stake, as it was based on a centralised and hierarchical framework. “We select and we write, you only read”; now shaped by the participatory possibilities of altogether “… we select, we write, we read”, and “… we share”. Emerging new roles, functions, actors, practices and scenarios are generated in the area of news production in order to approach the democratisation of news production where the social era is an enabler for citizens to publish news online with the aim of benefiting a community (Carpenter, 2010). In this amalgam of cross-connections, newspapers that use stories and videos or photos reported by citizens can create personal blogs to publish their opinions. At the same time, news content is being (re)tweeted through mobile phones. Facebook groups are being generated under the positive or negative judgment about a news story.

Finally, this new social logic is challenging traditional power and control of news production. It does this through creating user owned distribution mechanisms, and questioning traditional journalistic values. Consumers are increasingly turning to non-mainstream producers for their news supply (Greenhill & Fletcher 2015). This is leading to a new phenomenon, in which credibility is being shared across different news related sources. This in turn may influence the decision of news consumption. In contrast to a “hierarchy of credibility” (Paulussen & Harder, 2014), the term “distributed credibility”, as stated by Burbulles (2001), reinforces the social logic. It suggests that like-minded people may collectively evaluate the truthfulness and believability of an information source. Thereby, it is further legitimizing audience leadership in news production.

2.2. What social logic adds to news consumption?

The second modification brought by the social logic emphasises the way in which we relate to the news. With the social logic, it significantly changes the way we think about news consumption and how we are informed by the mass media. In a printed newspaper, it is the sub-editor who controls the lineal organisation and layout of editorial and advertising content. They also control the quality of editorial content. Conversely, the reading of online news is “multi-medial” and “intertextual” (Erdal, 2009). This is because the content is supplied through a network of hyper-connected links. In the online space, there are no restrictions of space, content quantity or production time. Therefore, online news can now be changed and updated in seconds. Online news sites because of legal pressure have to maintain their product quality. The most frequent changes occurring in the industry are consumer patterns and the participatory possibilities brought about by the social web. News are copied, cut and reframed in order to be shared through multiple networks and platforms. The process of consumption is extended by news sharing and website linking (Costera & Groot, 2014). This type of participation, which is named indirect participation (Splendore, 2013), influences the news making process, with incoming news trends calculated by the total number of re-twitters, hashtags or followers.

The perspective of gratification is modernising news consumption, based on user’s selections from an online “supermarket of news” (Schrøder, 2015). This is a major change in news flow, from which content is no longer static but depends on fluctuating trends. These trends determine the longevity of the news. It is important to consider that this movement in online news flow impacts in terms of market reach and readership scale, as online audiences can access the content more easily, either global or local news. With an ever-expanding access to information sources, point of production no longer singularly determines the pattern of consumption. As Hermida & Thurman (2008) argue, the advance of social media is eroding away fixed parameters of news timeliness, relevance and utility. The incessant online searching practices let the users go straight to the news that are leading their interest by simply typing a keyword in a search engine (Olmstead, Mitchell, & Rosenstiel, 2011). Likewise, information aggregator systems enable the user to choose and personalise their news domain (Nel & Westlund, 2013).

2.3. What social logic implies for the news prod-usage?

The proactive role of the audience is at the very heart of the social logic. As stated by Hermida (2012) social media reinforce the value of the audience to the media. New channels and new interacting tools expand the dimensions for understanding the participatory process. The participatory practices of social media have the potential not only to bring stakeholders, journalists and audiences together, but they also facilitate a more extensive version of the news production process. Those users can take part in the redefinition of news production practices and stages. Through the use of diverse participatory formulas, news are evolving into a dyadic service conversation rather than a mass-produced product for transactional consumption (Kunelius, 2001; Gillmor, 2006). The online space is enlarging the spread of news towards a global debate and in so doing is expanding its market reach. While the news content circulates around virtual spaces, with the Web 2.0 this product circulation is being converted into a social process of service conversation.

However, this process of online collaborative participation is a complex phenomenon also, known like an experience in co-creation between people (Pavlícková & Kleut, 2016). In order to progress from technological interaction with news product to effective participation in a co-designed news service it requires major rethinking. Without forgetting the many barriers associated with personal factors, technological facilities and opportunities, online participation requires a major change in news media agendas and the training of future journalists. The curriculum needs to be designed to take advantage of the Web 2.0.

Several authors (Domingo & al., 2008; Jonsson & Ornebring, 2011; Singer & al., 2011) have already started to differentiate stages regarding their online participatory practices in the news process. These approaches have been reviewed a conceptual framework has been designed. This was tested and advanced with empirical data. Then, there was an assessment with empirical evidence about the extent to which there is prod-usage in the news industry.

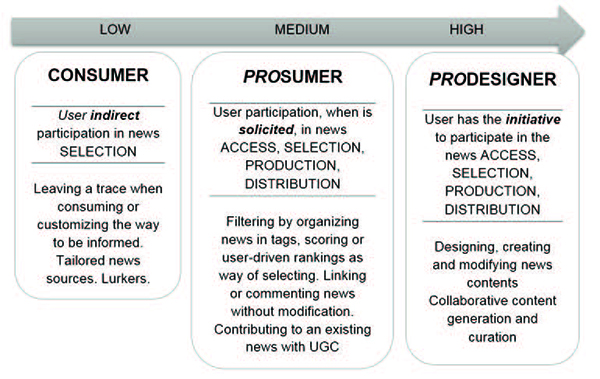

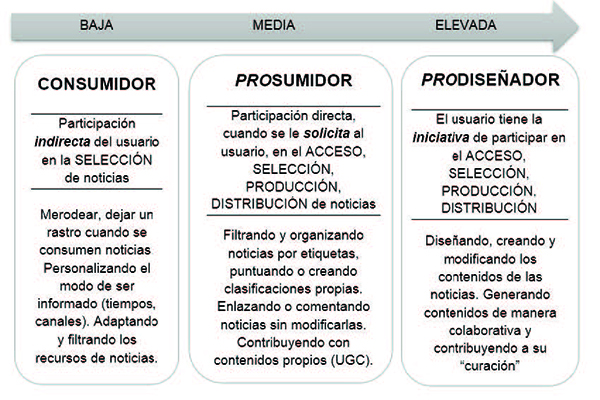

Our three-level conceptual framework suggests that participation in the processes of news consumption and production can take many different forms. Depending on user participation and contribution this can be unplanned, solicited or user oriented (figure 1).

The conceptual framework follows a participative continuum, from low to medium and also from medium to high participation. This evolution states the question of: what drives the participation of users in digital enabled social spaces? The first level assumes that users are only entities from whom news producers record and extract data. They do this in order to select and personalise their consumption of news. Some studies (Dennen, 2008) reported that even ‘lurkers’ are participating and receive benefits from this kind of indirect participation.

The second level implies an expansion of participation to other stages of the news production process, despite this stage is still driven by the news industry and a range of possibilities offered to users for news consumption and/or production. The user as prosumer ensures a possibility that news production is hierarchically organised. It is the news organisation that decides what is newsworthy and what is a mere story from a citizen. Audience participation is high, news users are invited to become active, but journalists control and dominate the stages of production.

The third level refers to more advanced participation with users as pro-designers. Bruns (2014) developed the term “prod-user” to emphasise users as being authentic producers. It is observable that participation goes beyond the stage of prod-user –the user contributing news in the production system– into the user actually news pro-designing. They are related to creating or modifying news content, distribution and circulation. News content is an evolving conversation via social media and the collaborative content generation tools that are available. With pro-designers, they stimulate a more democratic form of news production and curation. The narrative of the news is contingent on social media disruptive capabilities that dislocate the stream and permanence of news. The contributions of a pro-designer therefore are not always to create a new product but also to curate worthy content (Bruns, 2015).

This framework and the three levels were tested, as it is explained in the next section, by analysing the differences in user levels of participation at each stage of the production process. Our aim is to provide a theoretical assessment of opportunities and challenges of pro-designing news content.

3. Research method

Since the beginning of the 21st Century, The Pew Internet and American Life project has been conducting extensive, consistent and long-term representative random surveys on general and specific aspects of Internet users. The value for this study in using this wide-ranging data of Pew is that it provides the only comprehensive “neutral” dataset available on news consumption and production patterns. Whilst we were able to access other data sets and studies produced by the news industry, in other countries or contexts, these were not used as they were partially biased towards defending the online strategy of news organisations.

The data we analysed were obtained during the last five years through telephone interviewing. This was collected using stratified regional random sampling and digital dialling conducted by Pew in USA. The survey was administered among a regionally representative sample of 8,248 adults aged eighteen and older on landline and cell phones. The survey had an overall margin of sampling error of plus or minus 2 percentage points and a significant level of 95%. Using the Shapiro Wilk Normality test provided in the KNIME analytics software we found that it did not differ significantly from a normal distribution (W value of 1,595 p =<0.03) (Green & al., 1977). Furthermore, we explored the normal distribution curve of one of the most critical sample characteristics, which is “age”. The sample data for this variable is normally distributed with a minimum age of 18 rising to a maximum of 99. The Mean is 51.88, Variance is 392.67, Skewness is 0.21, Excess kurtosis is -0.547.

4. Results

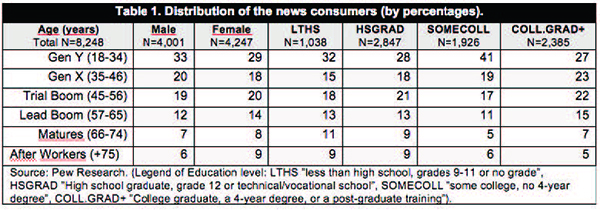

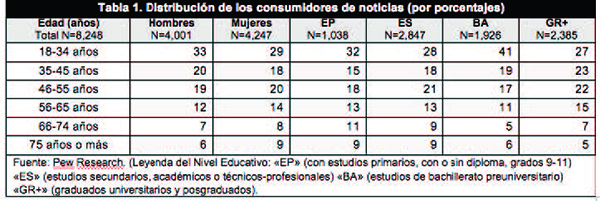

Using this Pew database, we explored patterns of users’ news consumption and production by examining the influence of variables such as: age (by six conglomerates of generational age breaks), gender and education level (by four groups of grade completed) as described in table 1. The analysis we conducted consisted of basic descriptive statistics and cross-tabulations.

4.1. News consumption and production patterns

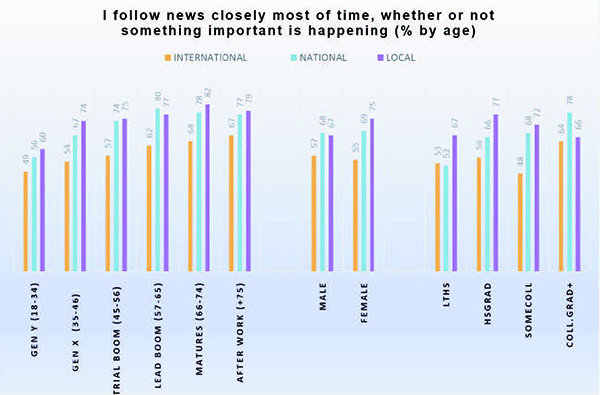

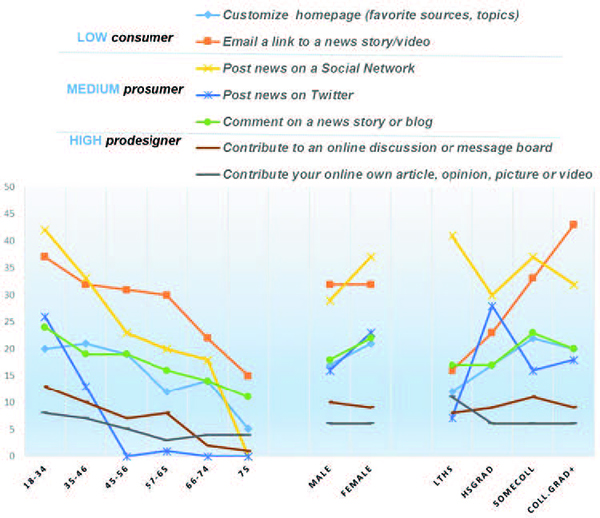

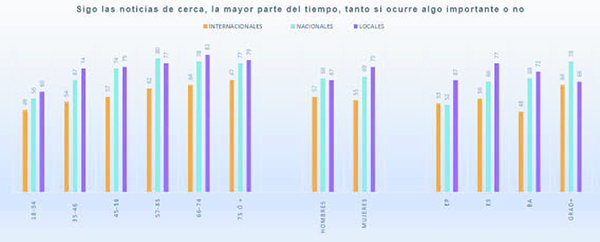

The results showed significant differences in the ways the audience engages with the news. Figure 2 illustrates the news consumption (news following) patterns of the audience studied based on age, gender and education. The table shows that the Matures (66-74 yr. old) consume the most news with 82% of them consuming local news closely followed by the Lead Boomers (57-65 yr. old) with 80% consuming national news.

Gen Y (18-34 yr. old) consume much less news that their older peers, with only 49% consuming international news as compared to 67% of After Workers (aged 75+) consuming international news. If we look at news consumption in relation to gender both males and females consume much less international news (57 and 56% respectively) when compared to local news; and females consume more local news (75%) than males (67%) with both genders following international news in a similar percentage. Overall, in relation to gender, females consume more news that males do, although a healthy number of females and males still follow the news.

Finally, in relation to education there are also significant differences in news consumption patterns. The largest variation in the consumption of news is the differences between College Graduates who are the largest consumers of national news (78%) and local news (64%). From the collegers (Somecoll: a category describing education beyond High School but not necessarily College graduate) only 48% consume local news (the lowest percentage of news consumption across all categories relating to age, gender and education). However, 72% of collegers consume international news. Therefore, whilst there is some relative consistency in the consumption of international news across the ages and between males and females, there are significant differences in relation to those who are regularly interacting with the news that has been produced.

Figure 2.

4.2. Accessing the news

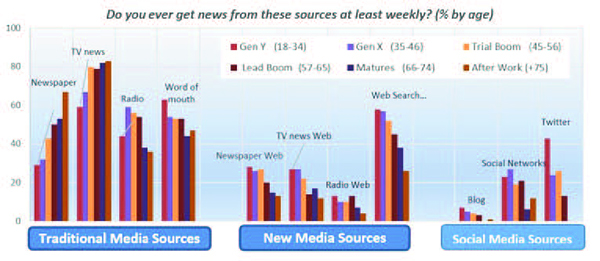

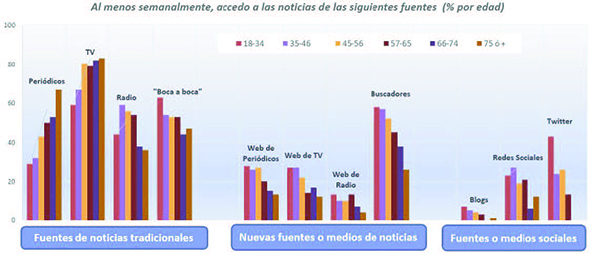

In contrast to how audiences consume news products, we also looked closely into where audience members access their news. Figure 3 further illustrates news consumption. However, these tables illustrate where various age groups are accessing their content, particularly in relation to new media sources such as social media versus traditional media.

All age groups indicated that their main source of content is television news. Gen Y (18-34 yr. old) source a significant amount of news by word of mouth (63%) and After Workers (75+) clearly prefer to read their news from newspapers in comparison to the other age groups. The most interesting finding in relation to new media is the comparison of sourcing news on the Web with Gen Y (18-34 yr. old) leading in searching the web and every other old age group falling away in terms of their use of the web to source news. The lowest user of the Web for news sourcing is the After Workers with only 30% drawing on this.

Similarly, the younger the age group is, the more likely it is to source news via Twitter or Bing with 425 of Gen Y using Twitter and only 17% of After Workers using Twitter as a source. Age seems to have a significant impact on the propensity to source news using social media.

Figure 3. News sources used by audiences according to age (by percentages).

4.3. Participatory continuum in the news social logic

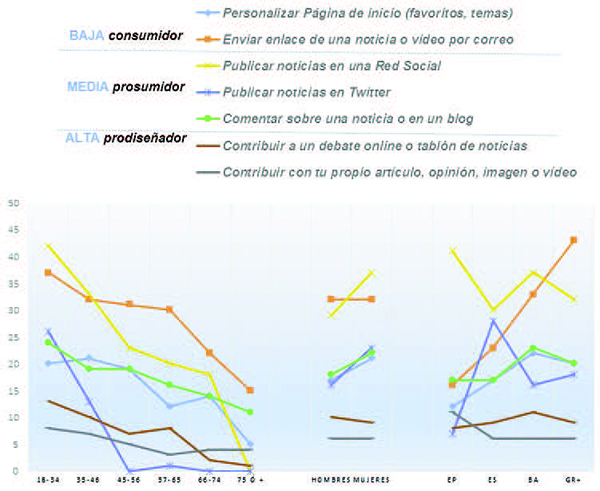

From seven items of the survey we extrapolated data to illustrate low to high levels of interaction and participation with the news. Drawing on three categories of age, gender and education, we explored participatory practices such as customising a home page in order to contribute your own online article, opinion, picture or video. The section of “social media sources” in Figure 3 reveals that Gen Y (18-34 yr. old) are the highest consumers and pro-designers but are not as high as Gen X (35-46 yr. old) in posting a news item to Twitter. Overall Gen Y are the highest news producers and designers and 65+ are the least, they are the group with the lowest rate to be a consumer, producer or pro-designer. No one over 50 yr. old tweeted about the news.

In terms of gender (figure 4), both females and males similarly pro-design and send an email link to a news story or video. Females are much bigger contributors of customising a home page, posting news on a social network, such as on twitter and commenting on a news story or blog. Education reveals the most surprising results in terms of who contributes to news. The higher the level of education is, the more likely the users are to email a link to a news story/video.

College Graduates are sending links double that of LTHS. However, LTHS are the biggest contributors of posting news on Twitter and contributing their own article, opinion, and pictures/ videos. High School Graduates are the largest Tweeters of news and those with some college education are the highest commenter’s on a news story or blog. Across all levels of education, pro-designing is minimal. While all levels of education moderately consume and prosume news, the data illustrate that education is associated with highest degrees of variation.

5. Discussion and conclusions. Implications for education

Some existing research on news consumption in adolescents (Casero-Ripollés, 2012; Condeza & al., 2014) and other young groups (Hasebrink & Domeyer, 2012) confirms our data as well as it confirms the opposite relationship between age and use of social media, where the elderly prefer reading printed news. The results from the Association for Research of Media (AIMC, 2015) indicate that the main activity in news consumption for the young generations is searching, diminishing the location-dependence for the news selection and consumption.

We are increasingly more immersed in a Web 2.0 culture; however, there are low levels of participation as users are predominantly consumers of news (as depicted in figure 4). Previous studies confirm that it is the toll or devices potential for interaction what is important, however our data reveal that there is little indication of change. With little evidence to suggest that citizens are actively co-designing editorial content with news organizations. Despite the myriad of participatory practices, some emerging studies confirm that participation in the processes of news production have been severely circumscribed, as the news organisation still dominates and controls the production of its editorial content (Domingo & al., 2008; Harrison & Barthel, 2009; Hermida & Thurman, 2008; Hermida, 2012; Sienger, & al., 2011).

Furthermore, the current research examples of participation demonstrate that the involvement of the user is not oriented towards the informational aspects of the news. Rather, the cultural or private stories, which have been widely analysed by Jönsson & Örnerbring (2011). Citizens are mostly empowered to create popular culture-oriented content and personal/everyday life-oriented content rather than news/informational content.

If news consumption is one of the ways and means of connection with reality, the challenge is how to increase the interest in online media and the involvement of different users for a global news conversation. While there is an increase in digital consumption (Katz, 2015) in all countries from USA, Europe and Asia (Diaz-Nosty, 2013), new educational approaches are required. These need to enable a citizen to think, create and produce media messages, and be actively engaged. Furthermore, they need to draw on their critical skills if they are to engage and participate in news consumption (Kuehn, 2011). This requires a rethinking to ensure that citizens acquire general and specific skills to support an efficient evolution from being a news user to being a “pro-designer”. Active and comprehensive media literacy coupled with involvement in the communication policy; and a revision of how media literacy levels in Europe should be assessed (Celot & Pérez-Tornero, 2010). Literacy programs should be designed to involve citizens of different ages in the active media prosumption and pro-design.

We suggest the following pro-design development initiatives for a more sustainable news ecosystem. First, the establishment of incentives for the audience to enhance their activating, or extrinsic or intrinsic motivation to participate (ways of rewarding based on explicit recognition, prizes or material). Second, regarding the production of the news, some mechanism of verification needs to be translated from the journalism practices to the community audience reports. Both with respect to reliability (trust) and readability (style) of the news. Third, another important issue are the regulations in the creation, management, sharing, curation and referencing of User Generated Contents. Certainly, we acknowledge there is a gap in between what technologies allow audience members to do for reporting an event, and what is legally appropriate to turn into public news.

For individuals, the development of the social logic will be based on an educational basis in participatory practices to be critical, active and responsible to, for and by the media. Although evidence of the higher levels of the conceptual framework was not significant to the data provided, with low presence of users in the news prodesign, it is worth to point out a fact that probably see multiplied after and may be present in the course taken by the news production in a near future worldwide. The social logic and the innovative practices described in the conceptual framework serve to make recommendations regarding media literacy. Thus, we finally propose some guidelines for media education aimed at training citizens to build their pro-design capabilities:

• Instead of passive viewing of news content, the evolutions of Web 2.0 towards collaborative formulas are offering a major involvement of the audience in the use of the media. However, individual factors such as demographic characteristic of the users –age, gender, and education– and the type of news content they are permitted to produce are restraining their participatory possibilities. Thus, democratic societies are asked to question the media literacy models, with a commitment for the training of audiences supporting the dignity, democratic values and civic ethics that makes sense in the self-identification and configuration of the social logic of diverse collectives.

• Media literacy training at early stages, from formal educational contexts, must be focused on providing tools and strategies for citizens to enable them to produce, and interpret the news, from a responsible, sustainable and ethical use. In older age groups, from formal and informal education, training programs must be developed for stimulating democratic news production and civic participation in the news production process. This will require in the long run the disrupting of the established design education curricula of schools and universities offers, which are moving away from specific emerging technologies that are in constant evolution, to training on successful participatory practices where citizens can find value and implication.

• If future news product design and production democratization is to occur then the key to its success will be the ability for the news innovators to work across a variety of different disciplines (besides to education including economics, politics, sociology, innovation, and computer science) so that they can build productive news eco-systems. Establishing transdisciplinary partnerships between public and private entities, audio-visual and journalistic professionals and other agents, would favour an effective exchange of how to analyse and what kind of participatory practices are needed across different cohorts in several media.

• With the advance of the social era, the role of citizens is evolving from prosumers into pro-designers. This could be in collaboration with incumbent news producers or through newly emerging organizational forms and citizen-driven production systems. This would facilitate wider democratic participation in news production and decentralised organizational designs. However, how much and when this will happen will of course depend on several factors linked to economics, technological feasibility, social policies and of course politics. Meanwhile, the creation of interconnection systems through virtual communities is necessary. These could emerge in social spaces and be encouraged by local community training initiatives. This includes the construction of a social logic led by principles such as “open participation”, “shared evaluation systems”, “heterarchy” and “connectivism”.

References

AIMC (2015). Resumen General. (http://goo.gl/4WKGdi) (2016-08-23).

Beckett, C. (2008). SuperMedia : Saving Journalism So It Can Save the World. Oxford: Blackwell.

Bruns, A. (2014). Beyond the Producer/Consumer Divide: Key Principles of Produsage and Opportunities for Innovation. In M.A. Peters, T. Besley, & D. Araya, (Eds.), The New Development Paradigm: Education, Knowledge Economy and Digital Futures. New York: Peter Lang.

Bruns, A. (2015). Working the Story: News Curation in Social Media as a Second Wave of Citizen Journalism. In C. Atton (Ed.), The Routledge Companion to Alternative and Community Media (pp. 379-388). London: Routledge.

Burbulles, N.C. (2001). Paradoxes of the Web: The Ethical Dimensions of Credibility. Library Trends, 49(3), 441-454.

Carpenter, S. (2010). A Study of Content Diversity in Online Citizen Journalism and Online Newspaper Articles. New Media & Society 12(7), 1064-1084. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809348772

Casero-Ripollés, A. (2012). Beyond Newspapers: News Consumption among Young People in the Digital Era. [Beyond Newspapers: News Consumption among Young People in the Digital Era]. Comunicar, 39, 151-158. https://doi.org /10.3916/C39-2012-03-05

Celot, P., & Pérez-Tornero, J.M. (2010). Study on Assessment Criteria for Media Literacy Levels. A Comprehensive View of the Concept of Media Literacy and an Understanding of How Media Literacy Levels in Europe should be Assessed. Brussels: EAVI: European Association for Viewers’ Interests. (http://goo.gl/U1Ai36) (04-12-2015).

Condeza, R., Bachmann, I., & Mujica, C. (2014). News Consumption among Chilean Adolescents: Interests, Motivations and Perceptions on the News Agenda. [News Consumption among Chilean Adolescents: Interest, Motivations and Perceptions on the News Agenda]. Comunicar, 43, 55-64. https://doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-05

Costera, I., & Groot, T. (2014). Checking, Sharing, Clicking and Linking: Changing Patterns of News Use between 2004 and 2014. Digital Journalism, 3 (5), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.937149

Dennen, V.P. (2008). Pedagogical Lurking: Student engagement in Non-posting Discussion Behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(4), 1624-1633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2007.06.003

Díaz-Nosty, B. (2013). La prensa en el nuevo ecosistema informativo. ¡Que paren las rotativas! Madrid: Ariel, Fundación Telefónica.

Domingo, D., Quandt, T., & al. (2008). Participatory Journalism Practices in the Media and Beyond. Journalism Practice, 2(3), 326-342. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512780802281065

Erdal, I.J. (2009). Repurposing of Content in Multi-Platform News Production. Journalism Practice, 3(2), 178-195. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512780802681223

García-Ruiz, R., Gozálvez, V., & Aguaded, I. (2014). La competencia mediática como reto para la educomunicación: instrumentos de evaluación. Cuadernos.info, 35, 15-27. https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.35.623

Gillmor, D. (2006). We theMedia : Grassroots Journalism by the People, for the People. Sebastopol: O’Reilly.

González-Fernández, N., Gozálvez, V., & Ramírez-García, A. (2015). La competencia mediática en el profesorado no universitario. Diagnóstico y propuestas formativas. Revista de Educación, 367, 117-146. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2015-367-285

Green, S, Lissitz R., & Mulaik S. (1997). Limitations of Coefficient Alpha as an Index of Test Unidimensionlity. Educational Psychological Measurement, 37, 827-38. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447703700403

Greenhill, A., & Fletcher, G. (2015). Self-Organizing Value Creation (pp 107-125). In G. Graham, A. Greenhill, D. Shaw, & C. Vargo (Eds.), Content is King: News Media Management in the Age of Turbulence. New York: Bloomsbury.

Harrison, T.M., & Barthel, B. (2009). Wielding New Media in Web 2.0: Exploring the History of Engagement with the Collaborative Construction of Media Products. New Media & Society, 11(1-2), 155-178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444808099580

Hasebrink, U., & Domeyer, H. (2012). Media Repertoires as Patterns of Behaviour and as Meaningful Practices: A Multimethod Approach to Media Use in Converging Media Environments. Participations, 9(2), 757-779.

Hermida, A. (2012). Social Journalism: Exploring How Social Media is Shaping Journalism. In E. Siapera, & A. Veglis (Eds), The Handbook of Global Online Journalism (pp. 309-328). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Hermida, A., & Thurman, N. (2008). A Clash of Cultures: The Integration of User-generated Content within Professional Journalistic Frameworks at British Newspaper Websites. Journalism Practice, 2(3), 343-356. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512780802054538

Hernández-Serrano, M.J., Greenhill, A., & Graham, G. (2015). Transforming the News Value Chain in the Social Era: A Community Perspective. Supply Chain Management. An International Journal, 20(3), 313-326. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-05-2014-0147

Jenkins, H. (2009). Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Jönsson, A.M., & Örnebring, H. (2011). User-generated Content and the News. Journalism Practice, 5(2), 127-144. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2010.501155

Kaplan, A.M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the World, Unite! The Challenges and Opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons, 53, 59-68. https//:doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

Katz, R. (2015). El ecosistema y la economía digital en América Latina. Madrid: Ariel, Fundación Telefónica. (http://goo.gl/oM2UJQ) (2016-08-23).

Kuehn, K. (2011). Prosumer-Citizenship and the Local: A Critical Case Study of Consumer Reviewing on Yelp.com. ProQuest LLC, Ph.D. Dissertation, Pennsylvania State University. (http://goo.gl/MPbO9Q) (2016-08-23).

Kunelius, R. (2001). Conversation: a Metaphor and a Method for Better Journalism? Journalism Studies, 2(1), 31-54. https//:doi.org/10.1080/14616700117091

Kümpel, A.S., Karnowski, V., & Keyling, T. (2015). News Sharing in SocialMedia : A Review of Current Research on News Sharing Users, Content, and Networks. Social Media+ Society, 1(2), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115610141

Lewis, S.C. (2012). The Tension between Professional Control and Open Participation. Information, Communication & Society, 15(6), 836-866. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.674150

Nel, F., & Westlund, O. (2013). Managing New (s) Conversations: The Role of Social Media in News Provision and Participation. In M. Friedrichsen, & W. Mühl-Benninghaus (Eds.), Handbook of Social Media Management (pp. 179-200). Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-28897-5_11

Olmstead, K., Mitchell, A., & Rosenstiel, T. (2011). Navigating News Online: Where People Go, How they Get there and Whatlures them Away. Pew Research Center, 1-30. (http://goo.gl/iTymIO) (2016-08-23).

O’Reilly, T. (2005). What is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software. O’Reilly Media, Inc. (http://goo.gl/edA2kN) (2016-08-23).

Papacharissi, Z. (2015). We have Always Been Social. Social Media + Society, 1, 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115581185

Paulussen, S., & Harder, R.A. (2014). Social Media References in Newspapers: Facebook, Twitter and YouTube as Sources in Newspaper Journalism. Journalism Practice, 8(5), 542-551. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2014.894327

Pavlícková, T., & Kleut, J. (2016). Produsage as Experience and Interpretation. Participations, 13(1), 349-359.

Pérez-Rodríguez, A., & Delgado, A. (2012). De la competencia digital y audiovisual a la competencia mediática: dimensiones e indicadores. [From Digital and Audiovisual Competence to Media Competence: Dimensions and Indicators]. Comunicar, 39, 25-34. https://doi.org/10.3916/C39-2012-02-02

Schrøder, K.C. (2015). News Media Old and New: Fluctuating Audiences, News Repertoires and Locations of Consumption. Journalism Studies, 16(1), 60-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2014.890332

Siapera, A. (2011). Understanding New Media. London: Sage.

Singer, J.B., Hermida, A., Domingo, D., Heinonen, A. Paulussen, S., Quandt, T. … Vujnovic, M. (2011). Participatory Journalism: Guarding Open Gates at Online Newspapers. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Splendore, S. (2013). The Online News Production and the Use of Implicit Participation. Comunicazione Politica, 13(3), 341-360. https://doi.org/10.3270/75017

Susarla, A., Oh, J.H., & Tan, Y. (2012). Social Networks and the Diffusion of User-generated Content: Evidence from YouTube. Information Systems Research, 23-41. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1100.0339

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Nuevas formas de participación democrática y producciones colaborativas de audiencias diversas han surgido como resultado de las innovaciones digitales en el acceso y consumo de noticias. El objetivo de este estudio es proponer un marco conceptual basado en las posibilidades de la Web 2.0. Describiendo la construcción de una «lógica social», que se combina con las lógicas comunicativa y computacional, se construye el marco teórico para explorar la evolución en el consumo de noticias desde una mera circulación de productos diseñados, hacia una conversación global de diseñadores proactivos de noticias. Este marco teórico se ha testeado a través de una base de datos empírica del Instituto de investigación PEW, que mediante una encuesta con adultos a gran escala permite analizar el futuro de la industria de las noticias. Los resultados muestran diferencias significativas (por edad, sexo y nivel educativo) en las formas de participación, acceso y consumo de noticias. Aunque existe una cultura Web 2.0, hay un bajo nivel de participación de usuarios en la producción de noticias; lejos de ser diseñadores proactivos de noticias, los hallazgos sugieren que la mayoría de ciudadanos se sitúan en los niveles de participación más bajos del marco conceptual propuesto. Se concluye sugiriendo la necesidad de que los responsables de la educación en medios desarrollen iniciativas formativas acordes a las posibilidades de la lógica social a través de la propuesta de pautas.

1. Introducción

El panorama digital emergente está incrementando la habilidad que tienen los ciudadanos para consumir noticias de modos muy diferentes. Al mismo tiempo, el uso de los medios on-line está cambiando el modo de producción de las noticias. Cada vez se discute más si se están borrando las barreras que separan a los productores de noticias (tradicionalmente, las agencias de noticias y los periodistas) de los nuevos usuarios de noticias (una gran diversidad de audiencias). Como resultado, se genera toda una combinación de actividades de producción y consumo de noticias entre los diversos actores. También surgen un nuevo conjunto de términos en torno a estas prácticas, como el de «prosumidor» (Gillmor, 2006) y el de «produsuario» (Bruns, 2014). Esto conlleva a que, cada vez más, las audiencias tengan un papel relevante y contribuyan en la producción del contenido de las noticias. Y a que los usuarios se vean empoderados para participar en el proceso de selección de noticias, su diseño y distribución. Este cambio añade un rol democrático para los usuarios, quienes pueden ser empoderados a través de la participación colaborativa que implica la Web 2.0.

Es interesante distinguir entre las dos principales interpretaciones del fenómeno Web 2.0 (Kümpel, Karnowski, & Keyling, 2015; Papacharissi, 2015). Por un lado, la Web 2.0 es presentada como una plataforma interactiva. O’Reilly (2005) describe esta plataforma como una arquitectura de participación. Básicamente, se crean numerosas herramientas y servicios disponibles para promover la interacción social. Por otro lado, la Web 2.0 es entendida como un elemento de habilitación social. Esta segunda interpretación está creando importantes transformaciones culturales y sociales, cambiando la forma en que las noticias están siendo producidas y consumidas. Jenkins (2009) indica que la participación, en la que se basa la evolución de las noticias hoy es cultural. Como resultado, nuevas prácticas, normas, valores y constructos están desarrollándose dentro de lo que podemos denominar como la «Cultura 2.0». Esta nueva forma cultural incluiría nuevos comportamientos digitales participativos para gestionar las noticias (Beckett, 2008). Y una mayor implicación, para que los usuarios se puedan convertir en productores de noticias y/o prosumidores (García-Ruiz, Gozálvez, & Aguaded, 2014; Pérez-Rodríguez & Delgado, 2012; González-Fernández, Gozálvez, & Ramírez-García, 2015).

En este artículo vamos a sugerir que los comportamientos participativos pueden ser parte de una nueva lógica, que denominamos: «lógica social». Una lógica que parte del amplio movimiento que supone el panorama digital, que está cambiando crucialmente los modos tradicionales de producción y consumo de noticias. La lógica social nos confronta con posibilidades innovadoras para incrementar la conectividad y participación, reconociendo las formas en que las audiencias están cada vez más involucradas en el proceso de las noticias y en los medios. Investigamos el alcance de la lógica social para liderar el cambio que hace que los ciudadanos estén cada vez más involucrados en el diseño y producción del contenido noticioso. El objetivo de este artículo es investigar la influencia de esta lógica social emergente en la producción de noticias y sus industrias. De acuerdo a este objetivo, primero desarrollamos un marco conceptual en torno al «prodiseño» de noticias. A continuación, usando este marco como herramienta analítica, lo sometemos a comprobación con datos empíricos extraídos de diferentes cohortes socioeconómicas de audiencias. Buscamos avanzar sobre las categorías teóricamente enunciadas en el marco conceptual, proporcionando un conocimiento más detallado del paradigma de la lógica social. Nuestra intención es descubrir si la teoría de la lógica social ha sido implementada, afectando a la industria de las noticias. Y nos preguntamos: ¿están los ciudadanos realmente diseñando en la práctica sus contenidos de noticias, y lo hacen junto a organizaciones profesionales mediáticas? Si no es así, ¿hay todavía barreras alzadas por la industria de noticias que frenan el «pro-diseño»? O ¿es simplemente que diferentes grupos (por edad, o nivel educativo) tienen más o menos motivación o interés por participar? Del análisis y la discusión de los datos extraídos, concluimos con pautas relevantes sobre la lógica social que podrían ser incluidas en la agenda educacional y en las prácticas de alfabetización digital.

2. Lógica social: un marco conceptual

Como han puesto de manifestó Jönsson y Örnebring (2011) con la Web 2.0 hay un amplio margen de posibilidades participativas sin precedentes, que están alentando niveles mucho más elevados de implicación de los usuarios en el proceso de producción de noticias. Sin embargo, si las audiencias cambian su rol de puramente consumidores a productores de noticias, entonces, puede que algunos cambios y barreras tengan que ser superadas. En el contexto 2.0, se necesita encontrar una fórmula más sostenible con la que los usuarios puedan convertirse verdaderamente en productores de noticias. Porque ellos serán elementos nucleares para añadir valor a las actividades, superando el rol periférico que supone la mera provisión de contenido generado por el usuario (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010; Susarla, Oh, & Tan, 2012). Por lo tanto, se necesita desarrollar un entendimiento más claro de la forma en que las noticias se comparten y producen, para poder enseñarse, y que los educadores contribuyan al desarrollo de la ecología de los medios sociales (Kümpel & al., 2015).

Los canales de noticias Web 2.0 y las herramientas interactivas de innovación están expandiéndose. Esto requiere determinar las dimensiones para entender los procesos de participación en entornos on-line, más allá del periodo de convergencia mediática. Como manifestó Siapera (2011), este periodo fue el resultado de la convergencia entre las características proporcionadas por la «lógica computacional» –la lógica de los ordenadores– y las características de la «lógica comunicativa» –la lógica de los medios–.

En este trabajo proponemos que junto con estas dos lógicas hay una tercera lógica, la «lógica social» (Hernández-Serrano, Greenhill, & Graham, 2015), que es la lógica de la Web 2.0. Las posibilidades innovadoras ofrecidas por la Web 2.0 sitúan al usuario ante una nueva lógica, a través de la cual se da un fuerte énfasis al componente social y a la forma en que nos conectamos on-line con otros usuarios. Es una nueva lógica donde algunas prácticas sociales pueden ser traducidas desde el contexto offline, mientras otras se alteran generándose nuevas prácticas e interpretaciones de las prácticas. En este contexto de la gestión de noticias, la lógica social impacta en las experiencias cotidianas de las audiencias, como consecuencia de la introducción de modos innovadores de interacción entre los productores tradicionales de noticias y otros usuarios. Como pusieron de manifiesto Nel y Westlund (2013), la participación en el contexto de la lógica social está cambiando las lógicas y las formas de control tradicionales de los «profesionales» del periodismo. Fundamentalmente, la lógica social crea oportunidades para la pluralidad de noticias mediáticas y prepara el camino para una era mucho más innovadora en el sector mediático de las noticias.

2.1. ¿Qué añade la lógica social a la producción de noticias?

La era social empieza a cuestionar de quién es la propiedad en la producción de noticias. Teniendo en cuenta que los periodistas y ciudadanos están más próximos que nunca para generar noticias, teóricamente, y que todos nosotros disponemos ahora de medios para convertirnos en creadores de noticias (Gillmor, 2006). Esto está acrecentando una tensión estratégica entre el control mantenido tradicionalmente por los profesionales y los nuevos niveles de participación abierta en la producción de noticias (Lewis, 2012). La autoridad informativa de la industria de noticias está en juego, dado que está basada en un marco centralizado y jerárquico: «nosotros seleccionamos y escribimos, tú solamente lees»; ahora modificado por las posibilidades participativas que implican que juntos podemos: «seleccionar, escribir y leer», y «compartir». Bajo este enfoque emergen nuevos roles, funciones, actores, prácticas y escenarios, que hacen más próxima la democratización de la producción de noticias, y dotan a la era social de una posibilidad habilitadora para que diferentes comunidades puedan beneficiarse de la publicación de noticias on-line (Carpenter, 2010). En esta amalgama de conexiones cruzadas encontramos: periódicos que usan historias, vídeos o fotografías realizadas por los ciudadanos; blogs personales de periodistas que publican sus opiniones; contenidos de noticias que están siendo (re)tuiteados a través de los teléfonos móviles; o grupos de Facebook que surgen para posicionarse positiva o negativamente ante historias de noticias, entre otros.

Esta nueva lógica social está, por tanto, cambiando el poder y el control tradicional de la producción de noticas, a través de la creación de mecanismos de distribución del rol propietario entre los usuarios, y cuestionando los valores periodísticos tradicionales. Los consumidores están convirtiéndose, cada vez más, en productores no convencionales de sus propias noticias (Greenhill & Fletcher 2015). Y todo ello está guiándonos hacia un nuevo fenómeno, en el cual la credibilidad está siendo compartida entre diferentes fuentes de noticias, lo que definitivamente influye en el consumo de dichas noticias. Contrario a la «jerarquía de la credibilidad» (Paulussen & Harder, 2014), en el contexto de la lógica social se afianza el término de «credibilidad distribuida», como argumentaba Burbulles (2001), haciendo que personas afines puedan evaluar colectivamente la veracidad y credibilidad de una fuente de información. Legitimándose, de este modo, el liderazgo de la audiencia en la producción de las noticias.

2.2. ¿Qué añade la lógica social al consumo de noticias?

La segunda modificación interpuesta por la lógica social enfatiza el modo en que nos relacionamos con las noticias. Con la lógica social, cambia significativamente el modo en el que pensamos sobre el consumo de noticias y las múltiples formas en que somos informados por los medios de comunicación. En los periódicos en papel, es el editor quien controla la línea editorial, el diseño organizativo o el contenido publicitario, así como la calidad del contenido editorial. En cambio, la lectura de las noticias on-line es «multimedia» e «hipertextual» (Erdal, 2009), ya que el contenido es suministrado a través de una red de enlaces hiperconectados. En el espacio on-line, no hay restricciones de espacio, de cantidad de contenido o límites de tiempo en la producción. Las noticias on-line pueden ser modificadas y actualizadas en segundos, con mayores presiones para mantener la calidad de su producto. La mayor parte de los cambios frecuentes que ocurren en la industria on-line se basan en patrones de consumo y posibilidades participativas provocadas por la web social, donde las noticias pueden ser copiadas, recortadas y replanteadas para ser compartidas a través de múltiples redes y plataformas. El proceso de consumo se ha visto extendido por las nuevas formas en que las noticias se enlazan y comparten (Costera & Groot, 2014). Este tipo de participación, que se ha denominado como participación indirecta (Splendore, 2013), influye también en el proceso de creación de noticias, con nuevas entradas basadas en las tendencias que marcan el número total de retuiteos, hashtags o seguidores.

La perspectiva de gratificación también está modernizando el consumo de noticias, basándose en las selecciones de los usuarios en el «supermercado on-line de noticias» (Schrøder, 2015). Esto supone un cambio relevante en la circulación de noticias, a partir del cual el contenido ya no es estático sino que depende de la fluctuación de tendencias muy diversas que determinan la longevidad de noticias. Es importante considerar que el modo en que las noticias circulan en el entorno on-line impacta en términos de alcance de mercado y en la escala de lectores, ya que las audiencias on-line pueden acceder a los contenidos más fácilmente, tanto a las noticias globales como a las locales. Y con un acceso cada vez mayor a las fuentes de información, el origen de la producción no está únicamente determinado por los patrones de consumo. Como Hermida y Thurman (2008) argumentaron, el avance de los medios sociales está deteriorando los parámetros fijados para la actualidad, relevancia y utilidad de las noticias. Las prácticas incesantes de búsqueda en línea permiten a los usuarios ir directamente a las noticias que más les interesan simplemente escribiendo una palabra clave en el buscador (Olmstead, Mitchell, & Rosenstiel, 2011). Del mismo modo, los sistemas agregadores de contenidos de información permiten al usuario elegir y personalizar el alcance y ámbito de las noticias (Nel & Westlund, 2013).

2.3. ¿Qué implica la lógica social para el «prodiseño» de noticias?

El papel proactivo de la audiencia es el verdadero corazón de la lógica social. Como manifestó Hermida (2012), los medios sociales refuerzan el valor de la audiencia hacia dichos medios. Los nuevos canales y las nuevas herramientas interactivas expanden las dimensiones que nos permiten entender los procesos participativos. Las prácticas participativas de los medios sociales tienen el potencial, no solo de atraer a las partes interesadas -periodista y audiencia juntos-, sino que también facilitan una versión más extensa del proceso de producción de noticias. Estos usuarios pueden formar parte de la redefinición de prácticas de producción y representación de noticias. A través del uso de diversas fórmulas participativas, las noticias evolucionan hacia una conversación diádica de servicios, no tanto como producto en masa sino como consumo transaccional (Kunelius, 2001; Gillmor, 2006). Mientras el espacio on-line está ampliando la difusión de noticias hacia un debate global, y al hacerlo, está ampliando su alcance de mercado, con la Web 2.0 el contenido de las noticias circula alrededor de los espacios virtuales, convirtiéndose en un proceso social al servicio de la conversación global.

Sin embargo, este proceso de participación colaborativa on-line es también un fenómeno complejo, como lo es toda experiencia de co-creación entre personas (Pavlícková & Kleut, 2016). Para poder progresar desde la interacción tecnológica con productos de noticias hacia la participación efectiva que implica el co-diseño de noticias, se requiere un planteamiento de mayor calado. Sin olvidar las muchas barreras asociadas a los factores personales, tecnológicos y de infraestructura, la participación on-line requiere un cambio amplio, empezando por las agencias de noticias mediáticas y la preparación de futuros periodistas, y también por los currículos educativos, donde desde etapas tempranas se enseñe a las audiencias a diseñar noticias y sacar partido de las posibilidades participativas de la Web 2.0.

Varios autores (Domingo & al., 2008; Jonsson & Ornebring, 2011; Singer & al. 2011) han comenzado ya a diferenciar escenarios en relación a las prácticas de participación on-line de las audiencias en el proceso de noticias. Hemos revisado estas aproximaciones y con base en ellas hemos delineado un marco conceptual, evaluado con datos empíricos hasta qué punto existe un «prodiseño» de noticias.

Nuestro marco conceptual en tres niveles sugiere que la participación en los procesos de consumo y producción de noticias puede darse de muchas formas diferentes. Dependiendo de la participación del usuario y su contribución, esta puede ser no planificada, solicitada u orientada por el usuario (figura 1).

El marco conceptual se establece en torno a un continuo participativo, desde poca a media y también alta participación. Esta evolución plantea la pregunta de: qué es lo que impulsa a los usuarios a participar en espacios sociales habilitados digitalmente.

El primer nivel asume que los usuarios son solo entes de los que los productores de noticias graban y extraen datos. Hacen esto para seleccionar y personalizar el consumo de sus noticias. Algunos estudios (Dennen, 2008) declaran que incluso los «merodeadores» están participando y reciben beneficios de este tipo de participación indirecta.

El segundo nivel implica una expansión de la participación hacia otras etapas del proceso de producción de noticias, aunque esta etapa todavía es guiada por la industria mediática limitando el rango de posibilidades ofrecido a los usuarios para el consumo y/o producción de noticias. El usuario como prosumidor asegura la posibilidad de que la producción de noticias pueda estar jerárquicamente organizada. Pero es la industria de las noticias la que todavía decide qué es una noticia relevante y qué es una mera historia contada por un ciudadano. La participación de la audiencia puede ser más elevada, ya que los usuarios de noticias son invitados a convertirse en agentes activos, pero los periodistas siguen controlando y dominando las fases de producción.

El tercer nivel es el que supone una participación más avanzada, entendiendo a los usuarios como pro-diseñadores. Bruns (2014) desarrolla el término «produsuario» para enfatizar el hecho de que los usuarios se conviertan en auténticos productores de noticias. Sin embargo, avanzando un poco más, se puede observar que la participación puede ir más allá de la etapa de productor –el usuario contribuye en el sistema de producción de noticias– para abarcar el proceso de pro-diseño de noticias. Los usuarios van creando o modificando el contenido de las noticias, su distribución y circulación. El contenido de las noticias es una conversación que evoluciona vertiginosamente en los medios sociales y a través de las herramientas de creación de contenido colaborativo que están disponibles. A diferencia de los produsuarios, los «pro-diseñadores» estimulan formas más democráticas en la producción de noticias. La narrativa de las noticias está supeditada a las capacidades disruptivas de los medios de comunicación que desplazan la transmisión y permanencia de noticias. Las contribuciones del «prodiseñador» no son siempre para crear un nuevo producto, sino también para seleccionar un contenido valioso (Bruns, 2015) para su «curación». Este marco conceptual y los tres niveles han sido contrastados en la práctica, como exploramos en la siguiente sección, analizando las diferencias en los niveles de participación del usuario en cada etapa del proceso de producción. Con ello, nuestro propósito es proporcionar una aproximación teórica de las oportunidades y desafíos que supone el prodiseño de contenidos de noticias.

3. Método de investigación

Desde principios del 2000, el proyecto «The Pew Internet and American Life» ha estado desarrollando de manera amplia, consistente y a largo plazo encuestas representativas y aleatorias de aspectos generales y específicos de los usuarios de Internet. El valor de estos datos de gran alcance de Pew es que nos proporcionan el único conjunto de datos «neutral» disponible sobre los modelos de consumo y producción de noticias. Mientras que hemos podido acceder a otros conjuntos de datos y a estudios producidos por la industria de las noticias, en otros países o contextos, se han desestimado, ya que podrían estar sesgados parcialmente hacia la defensa de la estrategia on-line de las propias organizaciones de noticias que financiaban dichos estudios.

Los datos analizados se obtuvieron durante los últimos cinco años a través de entrevistas telefónicas, a través de un muestreo aleatorio estratificado regional, en toda la población de Estados Unidos. La encuesta fue administrada a una muestra representativa regional de 8.248 adultos mayores de dieciocho años, a través de teléfonos fijos y móviles. La encuesta tuvo un margen de error de más o menos dos puntos porcentuales y un nivel significativo del 95%. Usando la prueba de Normalidad Shapiro Wilk proporcionada en el software de análisis KNIME, obtuvimos una distribución que no difirió significativamente de una distribución normal (W valor de 1,595 p=<.03) (Green & al., 1977). Además, exploramos la curva de distribución normal de una de las variables más crítica de la muestra, la edad, obteniéndose que los datos de la muestra para esta variable se distribuyeron normalmente, con una edad mínima de 18 años llegando a un máximo de 99; con una media de 51,88, varianza de 392,67, asimetría de 0,21, curtosis de -0,547.

4. Resultados

Usando los datos de la base de datos de Pew, exploramos los patrones de consumo y producción de noticias de los usuarios mediante el examen de la influencia de tres variables: edad (por seis conglomerados, de saltos generacionales de edad), sexo y nivel de estudios (por cuatro grupos, según el nivel completado) como se describe en la tabla 1. El análisis que desarrollamos se obtuvo a partir de estadísticos descriptivos y tabulaciones cruzadas.

4.1. Patrones de consumo y producción de noticias

Los resultados mostraron diferencias significativas en las formas en que la audiencia se involucra con las noticias. La figura 2 ilustra el consumo de noticias (seguimiento de noticias), el perfil de la audiencia estudiado a partir de la edad, el género y la educación. La tabla muestra que los adultos de 66-74 años consumen la mayoría de las noticias locales con el 82%, seguido de cerca por los usuarios de 57-65 años, los cuales consumen noticias nacionales en un 80%.

Los usuarios más jóvenes (18-34 años) consumen menos noticias que los usuarios de más edad, con solo un 49% de consumo de noticias internacionales, en comparación con el 67% de los usuarios de más de 75 años, quienes consumen más noticias internacionales. Si nos fijamos en el consumo de noticias en relación con el género, tanto hombres como mujeres consumen mucho menos noticias internacionales (57% y 56%, respectivamente); cuando comparamos las noticias locales y las mujeres, ellas consumen más noticias locales (75%) que los hombres (67%) con datos similares en ambos géneros ante las noticias internacionales. En general, en relación con el género, las mujeres consumen más noticias que los hombres, a pesar de que un buen número de mujeres y hombres todavía siguen ampliamente las noticias.

Finalmente, en relación al nivel educativo también hay diferencias significativas en los patrones de consumo de noticias. La mayor variación en el consumo de noticias se encuentra entre los graduados universitarios (GR+) que son los mayores consumidores de noticias nacionales (78%) y las noticias locales (64%). De los usuarios con estudios secundarios (ES) solo el 48% consume las noticias locales (el porcentaje más bajo de consumo de noticias en todas las categorías relacionadas con la edad, el género y la educación). Sin embargo, el 72% de usuarios con ES consumen noticias internacionales. Por lo tanto, aunque podríamos observar una tendencia en el consumo de noticias internacionales por edad y entre hombres y mujeres, sí hay diferencias significativas en relación al nivel de estudios y la forma en que se interactúa regularmente con las noticias de distinto ámbito.

Figura 2. Seguimiento de las noticias según su ámbito (por porcentajes).

4.2. Acceso a las noticias

Además de conocer cómo las audiencias consumen noticias, también hemos buscado un acercamiento sobre las fuentes que permiten el acceso de noticias en diferentes grupos de audiencias. La figura 3 ilustra el consumo de noticias, representando cómo diversos grupos de edad tienen acceso a su contenido. Particularmente, en relación con los nuevos medios de comunicación, los medios sociales frente a los medios de comunicación más tradicionales.

Todos los grupos de edad indicaron que su principal fuente son las noticias televisivas. En los usuarios de 18-34 años se observa una cantidad significativa de noticias conocidas informalmente, a través del boca a boca (63%), mientras que los usuarios de más de 75 años prefieren claramente los periódicos en papel, como fuente de información frecuente. El hallazgo más interesante en relación con los nuevos medios es la comparación de las fuentes de noticias en la web de los usuarios más jóvenes (18-34 años) liderando el consumo basado en las búsquedas de noticias en la web, frente a cualquier otro grupo de edad. El uso más bajo en la búsqueda a través de fuentes de la web, con solamente el 30%, se detecta entre los usuarios de mayor edad.

Del mismo modo los jóvenes son el grupo de edad que más utiliza diversas fuentes de noticias a través de Twitter o blogs, mientras que solo el 17% de los mayores de 65 años usan Twitter como fuente de noticias. La edad parece tener un impacto significativo, marcando una brecha que indica que solo los más jóvenes utilizan fuentes de noticias a través de los medios sociales.

Figura 3. Fuentes de noticias usadas por las audiencias de acuerdo a la edad (por porcentajes).

4.3. Continuo participativo en la lógica social de noticias

De los siete ítems de la encuesta extrapolamos los datos más significativos para ilustrar los tres niveles de interacción y participación con las noticias, que se describieron en el marco conceptual. Extrayendo las tres categorías de edad, género y nivel de estudios, exploramos las prácticas participativas desde la personalización en el acceso a las noticias, hasta la contribución de un artículo propio de opinión, una imagen o vídeo (figura 4).

En la figura 3, la sección de «fuentes o medios sociales» revelaba que los usuarios más jóvenes (18-34 edad) eran los mayores consumidores, pudiendo ser también pro-diseñadores, si consideramos los porcentajes elevados en la publicación de una noticia en Twitter; sin embargo, en el acceso y reenvío de noticias en redes sociales, los porcentajes no son tan altos como en el siguiente cohorte (35-45 años). En general, la tendencia podría ir en aumento, siendo los más jóvenes los más productores y diseñadores de noticias, mientras que los más mayores, los menores consumidores, productores o pro-diseñadores de noticias en los medios sociales; de hecho, nadie de más de 50 años tuiteó alguna noticia.

Atendiendo a la figura 4, por género, todas las mujeres y hombres presentan prácticas de prodiseño de manera similar, enviando enlaces de correo electrónico de una noticia o vídeo. Las mujeres son mucho más activas en la personalización de una página de inicio, en la publicación de noticias en una red social, o en Twitter, y en comentar una noticia o en un blog. El nivel educativo revela las mayores sorpresas en lo que se refiere al consumo de noticias. A mayor nivel educativo de los usuarios predomina más el envío por correo electrónico de enlaces a una noticia / vídeo. Los graduados universitarios envían enlaces el doble de lo que lo hacen los que solo cuentan con estudios primarios. Sin embargo, estos últimos son los más activos en la publicación de noticias en Twitter, contribuyendo con sus propios artículos de opinión y fotos/vídeos. Los que cuentan con estudios secundarios son los mayores tuiteros de noticias; y los que poseen un nivel de estudios de educación superior son los que más comentan en noticias o blogs. En todos los niveles el prodiseño es mínimo, se consume y «prosume» moderadamente, si bien, los datos ilustran que el nivel educativo podría estar asociado a la variación de altas cotas de participación en la producción de noticias.

5. Discusión y conclusiones: Implicaciones educativas

Algunas investigaciones existentes sobre el consumo de noticias en adolescentes (Casero-Ripollés, 2012; Condeza, Bachmann, & Mujica, 2014) y en otros grupos de jóvenes (Hasebrink & Domeyer, 2012) confirman nuestros datos, así como la relación inversa entre la edad y el uso de medios sociales, obteniéndose que las personas mayores prefieren la lectura de noticias impresas. Los resultados de la Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación (AIMC, 2015), indica que la actividad principal en el consumo de noticias para las nuevas generaciones es la búsqueda on-line de las mismas, disminuyéndose la dependencia de la localización del usuario en la selección y consumo de noticias.

Estamos cada vez más inmersos en una cultura Web 2.0; sin embargo, hay un bajo nivel de participación ya que los usuarios son en su mayoría meros consumidores de noticias (como se representa en la figura 4). Estudios previos han confirmado que el potencial de recursos y estrategias de interacción es importante, sin embargo nuestros datos revelan que hay poca evidencia de cambio. Hay relativamente pocos datos que sugieran que los ciudadanos estén activamente co-diseñando el contenido editorial junto con las organizaciones de noticias. A pesar de la gran cantidad de prácticas de participación, algunos estudios emergentes han confirmado que la participación en los procesos de producción de noticias está severamente limitada, ya que las industrias mediáticas todavía dominan y controlan la producción de su contenido editorial (Domingo & al., 2008; Harrison & Barthel, 2009; Hermida & Thurman, 2008; Hermida, 2012; Sienger & al., 2011).

Además, los ejemplos actuales de investigación en torno a la participación demuestran que la implicación del usuario no está orientada a los aspectos informativos de las noticias. Más bien a las historias culturales o privadas, como han analizado ampliamente Jönsson y Örnerbring (2011). Los ciudadanos están en su mayoría dirigidos a crear contenidos orientados a temas de cultura popular y de la vida diaria, más que a noticias o contenido propiamente informacional.

Si el consumo de noticias es una de las formas y medios de conexión de la ciudadanía con la realidad, el reto está en conseguir aumentar el interés por los medios on-line y promover la efectiva implicación de los diferentes usuarios en una auténtica conversación global de noticias. Si bien hay un aumento en el consumo digital (Katz, 2015) en todos los países (USA, Europa y Asia) (Díaz-Nosty, 2013), se requieren nuevos enfoques educativos que promuevan ese consumo, permitiendo a los ciudadanos pensar, crear y producir mensajes de los medios, y participar activamente. Además, es indispensable despertar sus habilidades críticas para que puedan participar y aplicarlas en el consumo de noticias (Kuehn, 2011). Retos que sin duda van a requerir una revisión de la agenda educativa, que asegure que los ciudadanos adquieran competencias, generales y específicas, para apoyar la evolución que supone convertir a los usuarios en «pro-diseñadores» de noticias. Para ello, se precisa una alfabetización mediática activa y global, junto con la intervención de políticas de comunicación innovadoras; y una revisión de cómo deben ser evaluados los niveles de alfabetización mediática en Europa (Celot & Pérez-Tornero, 2010). En un futuro próximo, los programas de alfabetización deberán estar diseñados para involucrar a los ciudadanos de diferentes edades como prosumidores y prodiseñadores activos de los medios.

Nosotros sugerimos las siguientes iniciativas de desarrollo sostenible en favor del pro-diseño en el ecosistema de noticias. En primer lugar, el establecimiento de incentivos a las audiencias para aumentar su implicación, hacia una motivación extrínseca o intrínseca para participar (formas de recompensas basadas en el reconocimiento explícito, premios o material). En segundo lugar, en cuanto a la producción de las noticias, de las prácticas de periodismo se necesitan traducir algunos mecanismos de verificación a las audiencias y cómo estas deben informar a la comunidad, tanto en lo que respecta a la fiabilidad (confianza) como a la legibilidad (estilo) de las noticias. En tercer lugar, otro aspecto importante son las regulaciones en la creación, gestión, distribución, curación y «referenciación» de contenidos generados por el usuario. Ciertamente, reconocemos que hay una brecha entre lo que las tecnologías permiten hacer a las audiencias para informar de un evento, y lo que legalmente es adecuado que se convierta en noticia pública.

Para los individuos, el desarrollo de la lógica social se basará en una serie de pilares educativos en torno a las prácticas de participación para convertirse en usuarios críticos, activos y responsables de, por y para los medios de comunicación. A pesar de que no hallamos suficientes datos que pudieran confirmar la existencia de niveles elevados de participación, respecto al marco conceptual, hallando una baja presencia de prácticas de prodiseño de noticias, vale la pena señalar un hecho que probablemente se verá multiplicado a medio plazo y que puede tomarse como referencia en la producción de noticias en un futuro próximo a nivel global. La lógica social y las prácticas innovadoras que se describen en el marco conceptual sirven para hacer recomendaciones con respecto a la educación mediática. En base a estas, y para finalizar, proponemos algunas pautas educativas para la formación en medios dirigida a los ciudadanos, que contribuyan a construir sus capacidades pro-diseñadoras:

• En lugar de una visualización pasiva de los contenidos informativos, las evoluciones de la Web 2.0 hacia fórmulas de colaboración están ofreciendo una importante participación de la audiencia en el uso de los medios de comunicación. Sin embargo, los factores individuales, tales como características demográficas de los usuarios –edad, género y educación– y el tipo de contenido de noticias que se les permiten producir están limitando sus posibilidades de participación. Por lo tanto, es una tarea de las sociedades democráticas el cuestionar los modelos de alfabetización mediática, con un compromiso en la formación de audiencias en apoyo a la dignidad, los valores democráticos y la ética cívica que tienen sentido en la autoidentificación y la configuración de la lógica social de colectivos diversos.

• La alfabetización mediática en las primeras etapas, especialmente en contextos educativos formales, debería centrarse en proporcionar herramientas y estrategias para que los ciudadanos puedan producir e interpretar las noticias, desde un uso responsable, sostenible y ético. En los grupos de edad más avanzada, desde la educación formal y no formal, se podrían desarrollar programas de formación para estimular la producción de noticias democráticas y la participación ciudadana en el proceso de producción de noticias. Para ello, será necesario a largo plazo la modificación del diseño de los planes de estudios establecido en las escuelas y universidades, que en ocasiones se alejan del conocimiento y uso de tecnologías emergentes específicas, que además están en constante evolución, para desarrollar una formación sobre prácticas exitosas de participación donde los ciudadanos pueden encontrar valor y sea más fácil su implicación.

• Si el futuro del diseño de noticias y la democratización de la producción están próximos a ocurrir, la clave de su éxito será la capacidad para innovar sobre las noticias, y que estas sean trabajadas a través de una variedad de diferentes disciplinas (además de la educación, incluyendo la economía, la política, la sociología, la innovación y la informática) para que pueda construirse un ecosistema productivo de noticias. El establecimiento de agrupaciones transdisciplinares entre entidades públicas y privadas, profesionales audiovisuales y periodísticos y otros agentes favorecerá un intercambio eficaz que permita analizar qué tipo de prácticas participativas son necesarias según cada nivel poblacional.

• Con el avance de la era social, el papel de los ciudadanos está evolucionando de prosumidores a prodiseñadores. Esto podría desarrollarse en colaboración con los productores de noticias o por medio de las organizaciones de reciente aparición, junto a sistemas de producción impulsados por los propios ciudadanos. Esto facilitaría una participación democrática más amplia en la producción de noticias y diseños organizacionales descentralizados. Sin embargo, cuánto y cuándo sucederá esto, por supuesto, dependerá de varios factores relacionados con la economía, la viabilidad tecnológica, las políticas sociales y la política en general. Mientras tanto, se puede pensar en una creación de sistemas de interconexión a través de comunidades virtuales. Estos podrían surgir en los espacios sociales y ser alentados por las iniciativas de formación de comunidades locales, que contribuirían a la construcción de una lógica social basada en principios tales como la «participación abierta», los «sistemas de evaluación compartidos», la «heterarquía» y el «conectivismo».

Referencias

AIMC (2015). Resumen General. (http://goo.gl/4WKGdi) (2016-08-23).

Beckett, C. (2008). SuperMedia : Saving Journalism So It Can Save the World. Oxford: Blackwell.

Bruns, A. (2014). Beyond the Producer/Consumer Divide: Key Principles of Produsage and Opportunities for Innovation. In M.A. Peters, T. Besley, & D. Araya, (Eds.), The New Development Paradigm: Education, Knowledge Economy and Digital Futures. New York: Peter Lang.

Bruns, A. (2015). Working the Story: News Curation in Social Media as a Second Wave of Citizen Journalism. In C. Atton (Ed.), The Routledge Companion to Alternative and Community Media (pp. 379-388). London: Routledge.