Summary

Background/Objective

To review published pediatric trauma research from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries so as to identify research fields that need to be enhanced.

Methods

A MEDLINE search for articles on pediatric trauma from GCC countries during the period 1960 to 2010 was performed. The content of articles was analyzed, classified and summarized.

Results

Fifty-three articles were found and retrieved of which 18 (34%) were published in the last 5 years, 42 (79.2%) were original articles. The first author was affiliated to a university in 29 reports (54.7%), to a community hospital in 13 (24.5%) and to a military hospital in 10 (18.9%). All articles were observational studies that included 18 (34%) case-control studies, 18 (34%) case reports/case series studies, 8 (15.1%) prospective studies, and 7 (13.2%) cross sectional studies. The median (range) impact factor of the journals was 1.3 (0.5–3.72). No meta-analysis studies were found.

Conclusion

A strategic plan is required to support pediatric trauma research in GCC countries so as to address unmet needs. Areas of deficiency include pre-hospital care, post-traumatic psychological effects and post-traumatic rehabilitation, interventional studies focused on a safe child environment and attitude changes, and the socioeconomic impact of pediatric trauma.

Keywords

children;research;strategic planning;trauma

1. Introduction

Pediatric trauma is a major health problem worldwide. Globally, pediatric injuries account for a remarkable 40% of all child deaths.1 Most Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries are-high income with developing economies.2 These countries include Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Pediatric trauma and its effects at a national level have not been extensively studied in this region. Prevention remains the most effective measure to reduce this burden of loss.3 Management and prevention priorities for childhood trauma must be identified and acted upon with implementation of strategic planning research initiatives. This cannot be accomplished comprehensively without awareness of what has been done already and which important areas of research have not yet been investigated.

The aim of this study is to analyze the areas of interest already explored and the quality of the pediatric trauma research conducted in GCC countries to date, in order to identify research areas that merit investigation.

2. Materials and methods

A MEDLINE search of the PubMed website on pediatric trauma publications from GCC countries covering the period 1960 to 2010 was performed.4 Definition of a child included everyone below the age of 18 years according to the Convention on Rights of the Child.5 Terms used for the search were “injury, trauma, child, pediatric”; age limits were 0–18 years, and specific country names were entered. A total of 101 abstracts were retrieved, all were reviewed manually. Fifty-nine articles were related to pediatric trauma, all full papers were obtained through the National Medical Library of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, UAE University.

The articles were critically analyzed and classified according to a prepared protocol developed specifically for the study. This protocol contained the country name, MEDLINE category, first authors' affiliation, year of publication, journal impact factor in 2008, study design, area of study, mechanism of injury, injured body regions, and reason(s) for exclusion of an article.

Six articles were excluded (Appendix 1): two were studies in adults; two articles included data not from GCC countries; one article was similar to a previously published study by the same author with the same study aim and patients; and one article was a short report of another article, which was published subsequently. The contents of 53 articles (Appendix 2) were studied. Data were reviewed by three of the authors, analyzed independently, discussed, and consensus was taken in controversial areas. The number of publications generated was standardized according to country population in 2007.2 Data were analyzed with PASW Statistics 18, SPSS Inc., USA.

3. Results

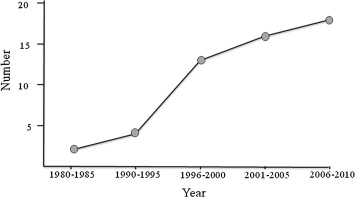

Fifty-three published pediatric trauma research articles from the GCC countries were retrieved. Eighteen (34%) articles were published during the past 5 years (Fig. 1) with Kuwait having the highest number of published articles per 100,000 population (0.42) (Table 1). Thirty-eight of 53 journals had an impact factor in the Journals Citation Reports.6 The median (range) impact factor of these articles was 1.3 (0.5–3.72).

|

|

|

Figure 1. MEDLINE pediatric trauma publications from the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. |

| Country | Number of articles | Population | Standardized data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kuwait | 12 | 2,851,144 | 0.42 |

| Saudi Arabia | 33 | 24,734,533 | 0.13 |

| UAE | 5 | 4,380,439 | 0.11 |

| Qatar | 1 | 840,635 | 0.11 |

| Oman | 2 | 4,595,133 | 0.04 |

The first author was affiliated to a university in 29 reports (54.7%), to a community hospital in 13 (24.5%) and a military hospital in 10 (18.9%). Forty-two (79.2%) of the reports were original articles (Table 2), only three articles (6%) were published in free-access journals. All articles have been observational studies that included 18 (34%) case-report/case-series studies, 18 (34%) case-control studies, 8 (15.1%) prospective studies, and 7 (13.2%) cross-sectional studies. No meta-analysis studies were found. The reported causes of trauma were mainly multiple mechanisms in 15 (28.3%) followed by road traffic collisions in seven (13.2%) (Table 3). Twenty-four (45.3%) reported the effect of trauma on multiple body regions (Table 4). No research publications were found on pre-hospital care, post-traumatic psychological effects, post-traumatic rehabilitation of injured children, interventional studies focused on a safe child environment and attitude changes, or the socioeconomic impact of pediatric trauma.

| Number | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Original article | 42 | 79.2 |

| Case report | 9 | 17.0 |

| Review | 1 | 1.9 |

| Letter to the Editor | 1 | 1.9 |

| Mechanism of injury | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple mechanisms | 15 | 28.3 |

| Road traffic collision | 7 | 13.2 |

| Burn | 6 | 11.3 |

| Penetrating injury | 5 | 9.4 |

| Child abuse | 3 | 5.7 |

| Iatrogenic | 3 | 5.7 |

| Animal-related | 2 | 3.8 |

| Corrosive ingestion | 2 | 3.8 |

| Drowning | 2 | 3.8 |

| Fall | 1 | 1.9 |

| Other mechanisms | 7 | 13.2 |

| Region | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple body regions | 24 | 45.3 |

| Extremity/orthopedic | 7 | 13.2 |

| Gastrointestinal | 6 | 11.3 |

| Head | 4 | 7.5 |

| Eye | 3 | 5.7 |

| Chest | 3 | 5.7 |

| Dental | 3 | 5.7 |

| Urology | 1 | 1.9 |

| Others | 2 | 3.8 |

4. Discussion

Trauma is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children. The curiosity of children and limited physical and cognitive ability render them more susceptible to injury than others. Their injuries are generally preventable.7 Principles of trauma management and prevention can be shared worldwide. The identification of regional features of pediatric trauma and subsequent planning for management and preventive interventions in GCC countries requires scrutiny of research stemming from the region. Publications are the final outcome of research and can be considered as an indicator of the level of research activity.

The MEDLINE is a valuable journal database with strict criteria for inclusion. Journals that are indexed in MEDLINE are highly cited and accessible through PubMed. We have chosen MEDLINE publications and the impact factors of the journals cited as indicators of good quality research.

Our study has shown that there have been very few publications on pediatric trauma in the GCC countries. These publications have increased exponentially. This was more obvious after 1990. The recent impact factor of these publications had a median value of 1.3.

A majority of the publications have come from university centers. Academic institutions have a responsibility to lead research endeavors in the community as Faculty members are usually trained in research methodology. Research collaboration between university, community, and military hospitals at national and regional levels will benefit the community as a whole.

The majority of pediatric trauma research in GCC countries was epidemiological in nature. Surprisingly, the studies were mainly observational. Neither randomized controlled trials nor meta-analysis studies were found. Case reports and case-series studies have the simplest design and constituted 34% of all studies. Eighteen (34%) of the reports were case-control studies. These can be completed in a much shorter time and are less expensive to conduct than other studies. Only eight (15.1%) were prospective in nature. This can be attributed to a lack of planning for clinical research, of incentives, time available for research, health informatics and available funding.8 Our study has shown that Kuwait was the most active GCC country in pediatric trauma research standardized per 100,000 population. This is not specific for pediatric trauma research per se but also for other types of medical research. We have shown previously that Kuwait had the highest standardized medical research publications in the GCC countries with 6.57 publications per 100,000 population followed by the UAE with 2.62 publications per 100,000 population. 9 The medical publications from Kuwait dropped temporarily following the Second Gulf War of 1990 but then increased exponentially, while medical publications from other GCC countries continued to increase exponentially over time.9 The same trend was shown in trauma research stemming from the UAE.10

Globally, road traffic injuries are the second leading cause of death among children aged 5 to 14 years.7 Road traffic collision (RTC) is a growing problem in the GCC countries with higher mortality rate compared with other high income countries.11 It is the most commonly studied mechanism of pediatric trauma and remains one of the leading causes of death and disability in the GCC Countries.11 The majority of injured children in the studies reported were pedestrians (70%). The overall mortality of RTC was 5% (Table 5).12; 13 ; 14

| Author | Country | Number | Gender M/F | Occupant | Pedestrian | Others | Mortality | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Maramhi et al12 | KSA | 5 | 4/1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Bile duct injuries |

| Crankson13 | KSA | 664 | 469/195 | 177 | 472 | 15 | 34 | |

| Gupta et al14 | Oman | 10 | — | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | Extradural hematoma |

| Total Percentage (%) | 679 (100) | 473/196 (71/29) | 185 (27.3) | 476 (70) | 18 (2.7) | 34 (5) |

KSA = Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Burns, drowning and falls were less studied. Scald burns were the most common types of burns (73%). Burns had an overall mortality of 1.6% (Table 6).15; 16; 17; 18; 19 ; 20 A 10-year retrospective study on drowning in children showed that 80% of patients were less than 6 years of age. Seventy-five percent of drownings occurred in private swimming pools, of which only one was compatible with proper safety standards for swimming pools.21 Two articles discussed child sexual abuse and child maltreatment, one of them was a 20-year retrospective study on surgical aspects of child sexual abuse. It has shown that 70% of sexually abused children were girls; the perpetrator was a family relative in 54% of the victims and 10% of the victims were disabled.22 Three articles discussed pediatric eye injuries. Lithander et al, in a cross-sectional survey of 6292 school students, has shown that 12 had loss of vision of one eye caused by an injury. In the majority of cases, families and teachers were not aware of the visual loss.23 Pediatric animal-related injuries were addressed in two studies; one of them was retrospective in 78 children. Ninety-two percent of these children were camel jockeys who fell during camel racing. The majority had head injuries.24

| Author | Country | No | Gender M/F | Scald | Flame | Electrical | Chemical | Others | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jamal et al15 | KSA | 197 | 119/78 | 148 | 45 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 9 |

| Lari et al16 | KSA | 394 | 234/160 | 276 | 91 | 10 | 4 | 13 | 12 |

| Bang et al17 | Kuwait | 388 | 233/155 | 388 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Al Qattan et al18 | KSA | 3 | 1/2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Al Shehri et al19 | KSA | 380 | 191/189 | 243 | 105 | 19 | 7 | 6 | — |

| Sharma et al20 | Kuwait | 826 | 526/300 | 550 | 192 | 65 | — | 19 | 11 |

| Total Percentage (%) | 2188 | 1304/884 (60/40) | 1605 (73.4) | 433 (19.8) | 96 (4.4) | 16 (0.7) | 38 (1.7) | 36 (1.6) |

KSA = Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

We included burns, poisoning, and other unintentional causes of trauma as external causes of injury in accordance with the WHO world report on child injury prevention.3 Furthermore, burns and poisoning are described in chapter XIX as a part of injuries in the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) Version for 2010.25

Clinicians and epidemiologists need to heighten an awareness in policy makers that trauma is a major public crisis that merits appropriate research and funding which can be cost-effective in reducing the unacceptable burden of trauma.3 Funding can also be raised from the local community if the importance of the research projects and their potential impact on child safety is clearly explained. Interdisciplinary collaboration between basic scientists, health care providers, clinical researchers, educators, economists, legislators and policing agencies is essential to drive the suggested agenda.

During the Arab Childrens Health Congress 2010 held in Dubai, a parallel round table session took place to identify the research agenda in the Middle East in the field of pediatric care, injury, and prevention. The general consensus was the need to direct the pediatric trauma research initiatives so as to fill the research gaps in this field in the GCC states. The recommendations of the conference were similar to the conclusion of the present paper.26

We realized the importance of injury surveillance and established a Trauma Research Group within our Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences in 2001. The first step in this direction was to collect data utilizing a registry surveillance system. The groups efforts resulted in establishing a trauma registry in 2003. This helped to consolidate trauma research efforts in the UAE and attracted more research funding which led to the development of a road traffic collision registry 3 years later.10 ; 27 The trauma registry was then modified to include important information on injury prevention and made more user-friendly with regard to easier data entry.28

Data in our trauma registry have given rise to a number of publications and abstracts in pediatric trauma, these being based on registry data that were presented nationally and internationally.29 ; 30

The trauma research publications from the UAE have helped to promote trauma prevention in the community leading to preventive legislation. A child safety seatbelt law has been recently implemented.31 ; 32 Another example is the prevention of child camel jockey injuries following legislation on 5 July 2005 banning children from taking part in camel racing.33 ; 34 Health Authority Abu Dhabi (HAAD) has developed a model of healthcare trauma system that will include major trauma centers at Abu Dhabi and Al-Ain cities.35

The next step is to establish a nationwide trauma registry, which will allow collection of data from different hospitals in distant emirates.28 The registry requires some modifications to collect specific data relating to pediatric trauma. Widespread experience from the USA has shown that simply inaugurating independent pediatric trauma registries may not succeed because of a lack of ongoing commitment to funding. According to the experience of the National Trauma Bank, USA, apparently, it is much more cost-effective to collaborate with trauma surgeons in adult practice, utilizing the same tool for data collection for both adults and children.36 Optimal trauma management and prevention is interdisciplinary in nature and collaborations between adult and pediatric trauma surgeons need to be built, with some difficult bridges to cross, for the benefit of all our patients regardless of age. We hope that governments in our region will realize the major socioeconomic impact of pediatric trauma on our communities so that they will support different research projects on pediatric trauma. This will identify the real size of the problem and ways for its management and prevention.

In summary, we believe that there is a need for greater commitment to strategic planning to support pediatric trauma research in the GCC countries with interactions between hospitals on a national and at a regional level. A well-organized user-friendly data collection system for pediatric trauma is essential for conducting such high quality research. Areas of deficiency needing to be addressed are pre-hospital care, post-traumatic psychological effects and post-traumatic rehabilitation of injured children, safe child environment, and the socioeconomic impact of pediatric trauma. Obstacles to these endeavors can be overcome if we can convince our local communities that such initiatives are of overriding importance in terms of child health and future economic prosperity.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix 1. Excluded articles.

- Al-Sayyad MJ. Taylor spatial frame in the treatment of pediatric and adolescent tibial shaft fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26:164–170.

- Bener A, Al-Suweidi NK, Pugh RN, Hussein AS. A retrospective descriptive study of pediatric trauma in a desert country. Indian Pediatr. 1999;34:1111–1114.

- Ghali AM, El Malik EM, Ibrahim AI, Ismail G, Rashid M. Ureteric injuries: diagnosis, management, and outcome. J Trauma. 1999;46:150–158.

- Oman JA, Cooper RJ, Holmes JF et al. NEXUS II Investigators. Performance of a decision rule to predict need for computed tomography among children with blunt head trauma. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e238–246.

- Rehmani R. Childhood injuries seen at an emergency department. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58:114–118.

- Rahman MM, Al-Zahrani S, Al-Qattan MM. “Outbreak” of hand injuries during Hajj festivities in Saudi Arabia. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;43:154–155.

Appendix 2. MEDLINE articles on pediatric trauma and injury from GCC countries included in the study.

- Al-Arabi KM, Sabet NA. Severe mincer injuries of the hand in children in Saudi Arabia. J Hand Surg Br. 1984;9:249–250.

- Al-Binali AM, Al-Shehri MA, Abdelmoneim I, Shomrani AS, Al-Fifi SH. Pattern of corrosive ingestion in southwestern Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:15–17.

- Al Eissa M, Almuneef M. Child abuse and neglect in Saudi Arabia: journey of recognition to implementation of national prevention strategies. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:28–33.

- Al-Hoqail R, Al-Shlash SO. Hand injuries in children at King Fahd Hospital of the University in Saudi Arabia (1989–1991). Afr J Med Med Sci. 2000;29:289–291.

- Ali AM, Al-Abdulgader A, Kamal HM, Al-Wehedy A. Traumatic and non-traumatic coma in children in the referral hospital, Al-Hasa, Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13:608–614.

- Al-Jame Q, Andersson L, Al-Asfour A. Kuwaiti parents' knowledge of first-aid measures of avulsion and replantation of teeth. Med Princ Pract. 2007;16:274–279.

- Al-Khawahur HA, Al-Salem AH. Iatrogenic perforation of the esophagus. Saudi Med J. 2002; 23:732–734.

- Al-Majed I, Murray JJ, Maguire A. Prevalence of dental trauma in 5–6- and 12–14-year-old boys in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Dent Traumatol. 2001;17:153–158.

- Almaramhi H, Al-Qahtani AR. Traumatic pediatric bile duct injury: nonoperative intervention as an alternative to surgical intervention. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:943–945.

- Al-Mofadda SM, Nassar A, Al-Turki A, Al-Sallounm AA. Pediatric near drowning: the experience of King Khalid University Hospital. Ann Saudi Med. 2001;21:300–303.

- Al-Moosa A, Al-Shaiji J, Al-Fadhli A, Al-Bayed K, Adib SM. Pediatricians' knowledge, attitudes and experience regarding child maltreatment in Kuwait. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:1161–1178.

- Al-Qattan MM. Self-mutilation in children with obstetric brachial plexus palsy. J Hand Surg Br. 1999;24:547–549.

- Al-Qattan MM. The cartilaginous cap fracture. Hand Clin. 2000;16:535–539, vii.

- Al-Qattan MM. Pediatric burns induced by psoralens in Saudi Arabia. Burns. 2000;26:653–655.

- Al-Qattan MM, Al-Zahrani K, Al-Boukai AA. The relative incidence of fractures at the base of the proximal phalanx of the thumb in children. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2009;34:110–114.

- Al-Salem AH, Qaisaruddin S. Thoracic and abdominal trauma in children. Ann Saudi Med. 1999;19:58–61.

- Al-Samarrai AY, El-Faqih SR, Atassi RA, Neel KA. Penetrating injury of the bladder (a unique etiology). Ann Saudi Med. 1995;15:414–415.

- Al-Sayyad MJ. Taylor spatial frame in the treatment of open tibial shaft fractures. Indian J Orthop. 2008;42:431–438.

- Al-Sebeih K, Karagiozov K, Jafar A. Penetrating craniofacial injury in a pediatric patient. J Craniofac Surg. 2002;13:303–307.

- Al-Shehri M. The pattern of paediatric burn injuries in Southwestern, Saudi Arabia. West Afr J Med. 2004;23:294–299.

- Ansari S, Al Moutaery K. An unusual cause of depressed skull fracture: case report. Surg Neurol. 1999;52:638–640.

- Bang RL, Ebrahim MK, Sharma PN. Scalds among children in Kuwait. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13:33–39.

- Barss P, Grivna M. Letter to editor — trends in childhood injury mortality in a developing country: United Arab Emirates. Int Emerg Nurs. 2009;17:130–131.

- Bayoumi A. The clinical epidemiology of childhood accidents in a newly urbanized Bedouin community in Kuwait: a pilot study. J Trop Pediatr. 1985;31:263–267.

- Behbehani AM, Lotfy N, Ezzdean H, Albader S, Kamel M, Abul N. Open eye injuries in the pediatric population in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract. 2002;11:183–189.

- Bener A, Al-Salman KM, Pugh RN. Injury mortality and morbidity among children in the United Arab Emirates. Eur J Epidemiol. 1998;14:175–178.

- Bener A, Al-Mulla FH, Al-Humoud SM, Azhar A. Camel racing injuries among children. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15:290–293.

- Bener A, El-Rufaie OE, Al-Suweidi NE. Pediatric injuries in an Arabian Gulf country. Inj Prev. 1997;3:224–226.

- Bener A, Hyder AA, Schenk E. Trends in childhood injury mortality in a developing country: United Arab Emirates. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2007;15:228–233.

- Boker AM. Bilateral tension pneumothorax and pneumoperitonium during laser pediatric bronchoscopy — case report and literature review. Middle East J Anesthesiol. 2008;19:1069–1078.

- Bouhaimed M, Alwohaib M, Alabdulrazzaq S, Jasem M. Toy gun ocular injuries associated with festive holidays in Kuwait. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:463–467.

- Crankson SJ. Motor vehicle injuries in childhood: a hospital-based study in Saudi Arabia. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22:641–645.

- Crankson SJ, Fischer JD, Al-Rabeeah AA, Al-Jaddan SA. Pediatric thoracic trauma. Saudi Med J. 2001;22:117–120.

- Gupta PK, Mahapatra AK, Lad SD. Posterior fossa extradural hematoma. Indian J Pediatr. 2002;69:489–494.

- Heller D. Child patients in a field hospital during the Gulf conflict J R Army Med Corps. 2005;151:41–43.

- Hijazi OM, Shahin AA, Haidar NA, Sarwi MF, Musawa ES. Effect of submersion injury on water safety practice after the event in children, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:100–104.

- Jamal YS, Ardawi MS, Ashy AR, Shaik SA. Paediatric burn injuries in the Jeddah area of Saudi Arabia: a study of 197 patients. Burns. 1990;16:36–40.

- Jetley NK, Al Assiry AH, Dawood AA, Donkol RH. Diagnostic dilemmas, course, management and prognosis of traumatic lung cysts in children. Case report. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:200–202.

- Lari AR, Bang RL, Ebrahim MK, Dashti H. An analysis of childhood burns in Kuwait. Burns. 1992; 18:224–227.

- Lithander J, Al Kindi H, Tönjum AM. Loss of visual acuity due to eye injuries among 6292 school children in the Sultanate of Oman. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1999;77:697–699.

- Mallick MS, Al-Bassam AA, Boukai AA. Non operative management of blunt bile duct injuries in children. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:341–344.

- Mirdad T. Pattern of hand injuries in children and adolescents in a teaching hospital in Abha, Saudi Arabia. J R Soc Promot Health. 2001;121:47–49.

- Nawaz A, Matta H, Hamchou M, Jacobsz A, Al Salem AH. Camel-related injuries in the pediatric age group. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1248–1251.

- Pal K, Alwabari A, Abdulatif M. Traumatic pharyngeal pseudodiverticulum mimicking esophageal atresia. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:195–196.

- Sharma PN, Bang RL, Al-Fadhli AN, Sharma P, Bang S, Ghoneim IE. Paediatric burns in Kuwait: incidence, causes and mortality. Burns. 2006;32:104–111.

- Shyama M, al-Mutawa SA, Honkala S. Malocclusions and traumatic injuries in disabled schoolchildren and adolescents in Kuwait. Spec Care Dentist. 2001;21:104–108.

- Raboei EH. Surgical aspects of child sexual abuse. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2009;19:10–13.

- Raboei EH, Syed SS, Maghrabi M, El Beely S. Management of button battery stricture in 22-day-old neonate. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2009;19:130–131.

- Reyna TM. Observations of a pediatric surgeon in the Persian Gulf War. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:209–213.

- Saquib Mallick M, Rauf Khan A, Al-Bassam A. Late presentation of tracheobronchial foreign body aspiration in children. J Trop Pediatr. 2005;51:145–148.

- Siddiqui MA, Banjar AH, Al-Najjar SM, Al-Fattani MM, Aly MF. Frequency of tracheobronchial foreign bodies in children and adolescents. Saudi Med J. 2000;21:368–371.

- Siddiqui S, Ogbeide DO. Use of a hospital-based accident and emergency unit by children (0–12 years) in Alkharj, Saudi Arabia. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2002;22:101–105.

- Taha D, Khider A, Cullinane AR, Gissen P. A novel VPS33B mutation in an ARC syndrome patient presenting with osteopenia and fractures at birth. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:2835–2837.

References

- 1 World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/index.html [accessed 21.07.10].

- 2 World Health Organization. Global status report on road safety: time for action, Geneva 2009. http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_safety_status/2009 [accessed 5.09.10].

- 3 World Health Organization. World report on child injury prevention, Geneva 2008. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241563574_eng.pdf [accessed 4.08.10].

- 4 US National Library of Medicine and National Institute of Health. PubMed. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PubMed [accessed March 2010].

- 5 World Health Organization. Convention on the Rights of the Child. New York, NY, United Nations, 1989(A/RES/44/25). http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/k2crc.htm [accessed 10.05.10].

- 6 Journals Citation Reports 2010. http://admin-apps.isiknowledge.com/JCR/JCR?PointOfEntry=Home&SID=P2gMFN25pIOFOcjE1FC [accessed 5.09.10].

- 7 World Health Organization. Violence and injuries: the facts 2010. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599375_eng.pdf [accessed 22.07.10].

- 8 F.M. Abu-Zidan, D.E. Rizk; Research in developing countries: problems and solutions; Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct, 16 (2005), pp. 174–175

- 9 S.F. Shaban, F.M. Abu-Zidan; A quantitative analysis of medical publications from Arab countries; Saudi Med J, 24 (2003), pp. 294–296

- 10 H.O. Eid, K. Lunsjo, F.C. Torab, F.M. Abu-Zidan; Trauma research in the United Arab Emirates: reality and vision; Singapore Med J, 49 (2008), pp. 827–830

- 11 A.K. Abbas, A.F. Hefny, F.M. Abu-Zidan; Seatbelt compliance and mortality in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries in comparison with other high-income countries; Ann Saudi Med, 31 (2011), pp. 347–350

- 12 H. Almaramhi, A.R. Al-Qahtani; Traumatic pediatric bile duct injury: nonoperative intervention as an alternative to surgical intervention; J Pediatr Surg, 41 (2006), pp. 943–945

- 13 S.J. Crankson; Motor vehicle injuries in childhood: a hospital-based study in Saudi Arabia; Pediatr Surg Int, 22 (2006), pp. 641–645

- 14 P.K. Gupta, A.K. Mahapatra, S.D. Lad; Posterior fossa extradural hematoma; Indian J Pediatr, 69 (2002), pp. 489–494

- 15 Y.S. Jamal, M.S. Ardawi, A.R. Ashy, S.A. Shaik; Paediatric burn injuries in the Jeddah area of Saudi Arabia: a study of 197 patients; Burns, 16 (1990), pp. 36–40

- 16 A.R. Lari, R.L. Bang, M.K. Ebrahim, H. Dashti; An analysis of childhood burns in Kuwait; Burns, 18 (1992), pp. 224–227

- 17 R.L. Bang, M.K. Ebrahim, P.N. Sharma; Scalds among children in Kuwait; Eur J Epidemiol, 13 (1997), pp. 33–39

- 18 M.M. Al-Qattan; Pediatric burns induced by psoralens in Saudi Arabia; Burns, 26 (2000), pp. 653–655

- 19 M. Al-Shehri; The pattern of paediatric burn injuries in Southwestern, Saudi Arabia; West Afr J Med, 23 (2004), pp. 294–299

- 20 P.N. Sharma, R.L. Bang, A.N. Al-Fadhli, P. Sharma, S. Bang, I.E. Ghoneim; Paediatric burns in Kuwait: incidence, causes and mortality; Burns, 32 (2006), pp. 104–111

- 21 S.M. Al-Mofadda, A. Nassar, A. Al-Turki, A.A. Al-Sallounm; Pediatric near drowning: the experience of King Khalid University Hospital; Ann Saudi Med, 21 (2001), pp. 300–303

- 22 E.H. Raboei; Surgical aspects of child sexual abuse; Eur J Pediatr Surg, 19 (2009), pp. 10–13

- 23 J. Lithander, H. Al Kindi, A.M. Tönjum; Loss of visual acuity due to eye injuries among 6292 school children in the Sultanate of Oman; Acta Ophthalmol Scand, 77 (1999), pp. 697–699

- 24 A. Nawaz, H. Matta, M. Hamchou, A. Jacobsz; Al Salem AH: camel-related injuries in the pediatric age group; J Pediatr Surg, 40 (2005), pp. 1248–1251

- 25 World Health Organization: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) Version for 2010. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en#/XIX [accessed 20.12.11].

- 26 Arab Children Health Congress: Congress recommendations. http://www.hearme.ae/recommendations2010.php [accessed 5.09.10].

- 27 S. Shaban, M. Ashour, M. Bashir, Y. El-Ashaal, F. Branicki, F.M. Abu-Zidan; The long term effects of early analysis of a trauma registry; World J Emerg Surg, 4 (2009), p. 42

- 28 S. Shaban, H.O. Eid, E. Barka, F.M. Abu-Zidan; Towards a national trauma registry for the United Arab Emirates; BMC Res Notes, 3 (2010), p. 187

- 29 M. Grivna, P. Barss, M. El-Sadig; Epidemiology and Prevention of Child Injuries in the United Arab Emirates: A Report for Safe Kids Worldwide, 2008; University Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences and Roadway Transportation & Traffic Safety Research Center, Al Ain, UAE (2008)

- 30 P. Barss, M. Al-Obthani, A. Al-Hammadi, H. Al-Shamsi, M. El-Sadig, M. Grivna; Prevalence and issues in non-use of safety belts and child restraints in a high-income developing country: lessons for the future; Traffic Inj Prev, 9 (2008), pp. 256–263

- 31 Hassan H. Seat belts mandatory for children by 2011. The National 2010. http://www.thenational.ae/news/uae-news/seat-belts-mandatory-for-children-by-2011?pageCount=0 [accessed 5.09.10].

- 32 Chung M. Buckle up to curb backseat deaths. The National 2009. http://www.thenational.ae/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20090902/NATIONAL/709019843 [accessed 5.09.10].

- 33 Emirates tightens camel race laws. BBC News World Edition. July 6, 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/4657353.stm [accessed 20.12.11].

- 34 F.M. Abu-Zidan, H.O. Eid, A.F. Hefny, M.O. Bashir, F.J. Branicki; Camel Bite Injuries in United Arab Emirates: A 6 year prospective study; Injury (2011) http://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2011.10.039

- 35 Health Statistics 2010, Health Authority Abu Dhabi, Updated 20 October 2011.http://www.haad.ae/HAAD/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=c-lGoRRszqc%3d&tabid=349 [accessed 20.12.11].

- 36 L.D. Cassidy; Pediatric disaster preparedness: the potential role of the trauma registry; J Trauma, 67 (2 Suppl.) (2009), pp. S172–S178

Document information

Published on 26/05/17

Submitted on 26/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?