Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Resumen

In researching student learning experience in Higher Education, a dearth of studies has investigated cognitive, social, and material dimensions simultaneously with the same population. From an ecological perspective of learning, this study examined the interrelatedness amongst key elements in these dimensions of 365 undergraduates’ personalised learning networks. Data were collected from questionnaires, learning analytics, and course marks to measure these elements in the blended learning experience and academic performance. Students reported qualitatively different cognitive engagement between an understanding and a reproducing learning orientation towards learning, which when combined with their choices of collaboration, generated five qualitatively different patterns of collaboration. The results revealed that students had an understanding learning orientation and chose to collaborate with students of similar learning orientation tended to have more successful blended learning experience. Their personalised learning networks were characterized by self-reported adoption of deep approaches to face-to-face and online learning; positive perceptions of the integration between online environment and the course design; the way they collaborated and positioned themselves in their collaborative networks; and they were more engaged with online learning activities in the course. The study had significant implications to inform theory development in learning ecology research and to guide curriculum design, teaching, and learning.

Resumen

En la Educación Superior, pocos estudios han investigado simultáneamente las dimensiones cognitivas, sociales y materiales de una misma población. Desde una perspectiva ecológica del aprendizaje, este estudio examina la interrelación entre elementos clave a partir de estas dimensiones en las redes personalizadas de 365 estudiantes. Los datos procedentes de cuestionarios, análisis de aprendizaje y calificaciones del curso permiten considerar estos aspectos en la experiencia de aprendizaje y en el rendimiento académico. Los participantes registraron niveles cualitativamente dispares en el nivel de implicación en el curso, oscilando de un enfoque orientado a la comprensión a enfoques basados en la reproducción de contenidos, lo que, junto a sus opciones de colaboración, generó cinco patrones distintos. Los resultados revelaron que una orientación más comprensiva y una cooperación con estudiantes de orientaciones similares tiende a asociarse con mejores rendimientos en el aprendizaje semipresencial. Sus redes personalizadas se caracterizaron por enfoques más profundos hacia el aprendizaje presencial y virtual; percepciones positivas hacia la integración de ambos contextos; el diseño del curso, por la forma y modo de colaboración; y por una mayor implicación en las actividades en línea. El estudio tuvo implicaciones significativas de aplicación en el desarrollo teórico de la investigación en la ecología del aprendizaje, así como en la forma de guiar el diseño del currículum, la práctica docente y el aprendizaje.

Keywords

Ecological perspective, personalised learning network, interrelatedness, cognitive dimension, social dimension, material dimension, blended learning experience, university students

Palabras clave

Perspectiva ecológica, red de aprendizaje personalizada, interrelación, dimensión cognitiva, dimensión social, dimensión material, experiencia de aprendizaje semipresencial, estudiantes universitarios

Introduction

In contemporary Higher Education, students are increasingly given choices in their learning processes: the subjects they choose to study, the lectures they prefer to attend or view online, the approaches they favor when learning in a seminar, the ways in which they learn online, their partners for laboratory work, or their preference to study in a physical library or log onto an online database. Consequently, modern experiences of learning at the university level should be understood in terms of contemporaneous decisions made by students when they engage in different dimensions in their learning. In this study, we argue that each choice made by students can be considered as an element in relation to a personalised learning network, which can have different levels of success. The purpose of the study is to explain why some personalised learning networks are relatively more or less successful. Adopting an ecological perspective on student experience of learning, which looks for associations across multiple dimensions, this study examines: 1) Qualitative differences in first-year science students’ personalised learning networks created by their decisions involving approaches to, and perceptions of learning, their choices of collaboration with others, and the extent of engagement with learning technologies in and outside of class in a human biology subject designed as a blended course; 2) How these choices are related to their academic performance in the course.

An ecological perspective on learning

The term “ecology” is used to describe the dynamic interactions between organisms and their environments in which a diversity of factors is intricately intertwined (Ellis & Goodyear, 2019). When the ecological metaphor is applied to learning, Barron (2006: 195) defines a learning ecology as: “the set of contexts found in physical or virtual spaces that provide opportunities for learning. Each context is comprised of a unique configuration of activities, material resources, relationships, and the interactions that emerge from them.” Likewise, Jackson (2013: 2) describes an individual’s learning ecology as one that: “Comprises their process and set of contexts and interactions that provides them with opportunities and resources for learning, development and achievement. Each context comprises a unique configuration of purposes, activities, material resources, relationships and the interactions and mediated learning that emerge from them”. These two definitions share some similarities that learning is seen as a dynamic system from an ecological perspective, and such an ecosystem of learning is constituted by the interdependencies between learners and their intertwining with people and multifarious material resources (Ellis & Goodyear, 2019). To date, only limited research has adopted ecological perspectives in the study of learning. Of these limited studies, the majority has been conducted in school settings (Barron, 2004; Barron, Wise, & Martin, 2013). One of the limitations of these studies has been the use of a single method —either the survey or the observational method— failing to provide a more comprehensive picture of students’ learning ecologies than could be obtained by using multiple methods. This study fills these gaps as it investigates ecologies of university students’ learning experience by adopting complementary methods drawing on different data sources. From the definition that learning ecologies are seen as the interdependencies between learners and their intertwining with people and things, we considered three dimensions in students’ learning experience, namely cognitive, social, and material. While the cognitive dimension is primarily concerned with learners’ internal states, which are interdependent on other learners and non-human elements in learning, the latter two focus on the social and material dimensions respectively.

For analytical purposes, we selected the key elements in each dimension: including approaches to, and perceptions of, learning (cognitive dimension); with whom and how to collaborate (social dimension); and engagement with learning technologies both in and outside formal classes (material dimension). Investigation of the interplay of these elements across the dimensions will be able to reveal features of relatively more or less successful personalised learning networks, providing important actionable knowledge for educators to improve student learning experience. In successful personalised learning networks, we hypothesise that the elements are aligned and coherent, which tend to support student understanding of subject matter and assist them achieving desirable learning outcomes. In impoverished networks, students may miss key elements in learning, or the elements are likely to be fragmented and unaligned. Such experiences will impede understanding and be related to poorer academic performance. Investigating variations across multiple dimensions of student experience will provide holistic evidence that reveals structural features of successful personalised learning networks for the purposes of learning improvement. The rationale of adopting an ecological perspective includes the following:

- It acknowledges that the reality that university student learning experiences are made up of multiple elements in many dimensions and the interplay between them, which are dynamic, hard to separate, and intricately intertwined. Hence, it is only through investigation of the interrelatedness amongst them that one can explain why some students are more successful than others.

- It allows for a synergy of complementary research methodologies so that the complexity of modern learning experiences across class and online contexts can be effectively revealed.

- It accommodates a combination of different data sources, including self-report and observational data in order for triangulation of research results.

From the definition that learning ecologies are seen as the interdependencies between learners and their intertwining with people and things, we considered three dimensions in students’ learning experience, namely cognitive, social, and material.

Informed by this rationale, the study draws on methodologies in three areas: 1) Student approaches to learning (Pintrich, 2004; Prosser & Trigwell, 2017); 2) Social network research (De-Nooy, Mrvar, & Batagelj, 2011; Wasserman & Faust, 1994); 3) Materiality in learning (Fenwick, 2015; Fenwick & Landri, 2012). A combined use of these methods is illuminating because: 1) Their explicit and implicit intent to reveal qualitative variations when used to investigate student learning; 2) Their capacity to examine student learning experience at the individual and group levels across face-to-face and online contexts; and 3) they are consistent with an ecologically informed, social scientific way to understanding student learning experience adopted in this study.

Student approaches to learning (SAL) research

SAL research is used in this study to identify key cognitive elements in student learning experience to explain qualitatively different academic performance in Higher Education (Kember, 2015). Seminal studies have shown that how students go about learning (their approaches) and how they perceive learning (their perceptions) relate to their learning performance (Entwistle & Ramsden, 2015).

Applying the framework in blended learning context, research has demonstrated logical associations amongst approaches to face-to-face and online learning and perceptions of blended learning environment: students who perceive that face-to-face and online learning are well integrated tend to adopt deep approaches to learning and to using online learning technologies, which in turn are positively associated with better academic achievement (Ellis, Pardo, & Han, 2016). These deep approaches are proactive, engaged, reflective, and analytical, which help to achieve meaningful understanding of the subject matter (Nelson Laird, Seifert, Pascarella, Mayhew, & Blaich, 2014). When students do not see the relevance between face-to-face and online learning, they are more likely to approach learning on a surface level, thereby obtaining relatively poorer performance (Ellis & al., 2016).

Surface approaches involve adopting simplistic learning strategies, relying heavily on formulaic and mechanistic ideas to merely fulfill the required tasks and to pass exams (Vermunt & Donche, 2017). The cognitive elements investigated in this study are student approaches to face-to-face and online learning and their perceptions of the blended learning environment.

Social network research

Originating in sociology, social network research aims to identify, detect, and interpret roles of individuals within a group and patterns of ties amongst individuals (De-Nooy & al., 2011; Wasserman & Faust, 1994). Social network research in education has investigated work and discussion ties amongst teachers (Quardokus & Henderson, 2015), characteristics of formal and informal interactional networks amongst students (Cadima, Ojeda, & Monguet, 2012), the relation between friendship ties and learning outcomes (Brewe, Kramer, & Sawtelle, 2012; Rienties, Héliot, & Jindal-Snape, 2013), students’ online communications (Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Zhu, Questier, & Alfonso, 2015), and the associations between learning networks and achievement (Tomás-Miquel, Expósito-Langa, & Nicolau-Julia, 2015).

The current study will investigate the relations between students’ approaches to learning, perceptions of the blended learning environment, and quality of collaborations, because of limited extant research. The key social network measures of student collaborations will serve as indicators of social elements in student learning experience.

Materiality in learning

Research into materiality in learning experience focuses on a combined unit of analysis of “people and things” (artefacts), and how their combination helps to create, consolidate, and disseminate knowledge (Fenwick, 2014). Informed by social constructivism, this body of research challenges the isolated role of human factors and foregrounds things in the learning (Fenwick, 2014).

Hence, objects, things, and artefacts are not considered as merely having meanings attributed to by humans. Instead, they are treated as “continuous with and in fact embedded in the immaterial and the human” (Fenwick, Nerland, & Jensen, 2012:6). This area of research has been used to explore how learning is experienced through learner configurations, tangible and intangible objects, such as learning tasks in class and online (Ellis & Goodyear, 2019). In this study, students’ use of online learning technologies is considered an element of the material dimension of their learning experience.

Research questions

Three research questions guided the current study:

1) What are the relations between cognitive elements of learning experience and academic performance?

2) What are the relations between cognitive and social elements of learning experience and academic performance?

3) What are the relations amongst cognitive, social, material elements of learning experience and academic performance?

Material and method

Participants

Altogether 365 first-year undergraduates (251 females, 113 males; ages: 18 to 53, M=19.72, SD=3.55) from a metropolitan Australian university were recruited following the university ethics guidelines. They were enrolled in a semester-long blended course – introduction to human biology. They were from faculties of health sciences (162), nursing (22), pharmacy (55), and sciences (124) (two students did not report faculty information.

Learning context

The face-to-face teaching in the course included a weekly two-hour lecture, a three-hour laboratory class every fortnight, and a two-hour workshop every other week. The online learning required 6 to 9 hours’ participation in the weekly activities and collaboration. An important learning goal in the course was to develop students’ teamwork and collaborative skills, which was promoted by encouraging students to work in small groups to conduct experiments in the laboratory and to co-write scientific reports in the workshops. The course not only required students to learn disciplinary contents, but it also aimed to develop graduate skills, including inquiry abilities, critical and creative thinking, and collaborative skills.

Data sources and instruments

The data came from four sources: 1) A 5-point Likert-scale questionnaire interrogating approaches to, and perceptions of, learning (cognitive elements); 2) A social network questionnaire interrogating students’ collaboration (social elements); 3) Online learning analytics measuring frequency and time of students’ interactions with the online learning technologies (material elements); 4) The final marks (students’ academic performance).

The Likert-scale questionnaire

The development and validation of the scales in the questionnaire has been reported in previous studies (Bliuc, Ellis, Goodyear, & Piggott, 2010; Ellis & Bliuc, 2016; Han & Ellis, 2019a), which confirmed the reliability and validity. The items pool was constructed by drawing on interviews with students and consulting with the SAL literature and previous questionnaires using the SAL framework (Biggs, Kember, & Leung, 2001; Crawford, Gordon, Nicholas, & Prosser, 1998). Item analysis, exploratory factor analysis, scale reliability analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, and invariance tests have been used for validating the scales (Han & Ellis, 2019a).

- “Deep approaches to inquiry” scale (DAI: 5 items; α=.71) describes that approaches to learning through inquiry are characterized being proactive, initiative, and independent, with deep thinking to pursue a line of inquiry (e.g., “I often pursue independent pathways when researching something”).

- “Surface approaches to inquiry” scale (SAI: 4 items; α=.63) are approaches that lack thinking, being simplistic and mechanistic, and are heavily dependent upon others (e.g., “Researching something for a task means only using the resources given to me by the teacher”).

- “Deep approaches to online learning technologies” scale (DAT: 5 items; α=.72) assesses using technologies as a way to promote deeper understanding of the key ideas, to facilitate research, to connecting concepts in the course to real-world problems (e.g., “I spend time using the learning technologies in this course to connect key ideas to real contexts”).

- “Surface approaches to online learning technologies” scale (SAT: 4 items; α=.66) describes using online learning technologies to a limited extent, and using them as just to satisfy course requirements rather than to promote learning (e.g., “I only use the learning technologies in this course to fulfil course requirements”).

- “Perceptions of integrated learning environment” scale (INTER: 6 items; α=.88) evaluates to what extent students’ perceptions of face-to-face (e.g., lectures, ideas, and key concepts presented face-to-face) and online learning (e.g., online resources, course website, online activities) are coherent and integrated (e.g., “The online activities help me to understand the lectures in my course”).

The social network questionnaire

The social network questionnaire examined students’ choices of collaborators and mode of collaborations. Students were asked to name up to three peers according to frequency of collaborations in this course; and to indicate the mode of collaborations.

Please list up to three students you collaborated in this course according to frequency, and circle the mode of collaboration (F=face-to-face, B=both face-to-face and online): The most frequent: F-B; The second most frequent: F-B; The third most frequent: F-B.

The online learning analytics

The online learning analytics included frequency and time spent on online learning resources and interactive activities. The online learning resources, which included course timetable, learning objectives and learning outcomes, reading materials, video lectures, lecture notes, and digital images, provided sufficient scaffolding and materials.

The online interactive activities included multiple-choice questions, labeling, matching, text entry, short answer questions, biological card games, and these components offered opportunities to interact with biological concepts and receive feedback on their responses.

The final marks

The final marks (ranged from 32 to 90, M=67.93; SD=10.13) were aggregated scores of six assessments: 1) Summative quizzes for laboratory sessions (15%); 2) Oral presentation of a case study (8%); 3) Online posts following each workshop (3%); 4) Peer feedback for scientific report drafts (4%); 5) Final scientific report (20%); 6) Final examination (50%).

Except for peer feedback, all the assessments were graded by the teaching staff. The final examination consisted of multiple-choice questions based on the learning materials from the course.

Data collection

The questionnaires were completed in class towards the end of the semester. Students were ensured that once their responses to the questionnaire were matched with the online learning analytic data and their final marks, unique codes would be assigned to replace their names in the data analyses.

Data analysis

To answer the first research question, correlation, cluster analysis, and one-way ANOVAs were performed. While correlation analyses examined pairwise relations, cluster analysis and one-way ANOVAs revealed interrelations amongst groups of variables. To answer the second research question, social network analysis (SNA) were applied using Gephi, which visualized collaborative patterns and calculate key SNA measures, including degree, eccentricity, average clustering coefficients, and eigenvector (Bonacich, 2007).

The SNA measures across different collaborative patterns were then compared using one-way ANOVAs. To provide the answer to the third research question, one-way ANOVAs and post-hoc analyses were conducted to examine the frequency and time spent on learning technologies amongst qualitatively different collaborative patterns jointly shaped by students’ choices in the cognitive and social elements.

Results

Results for research question 1

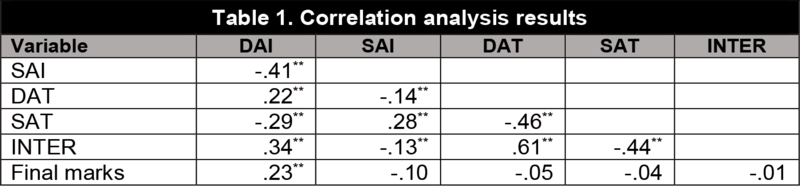

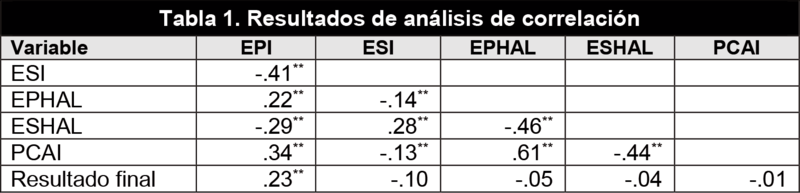

The results of correlation analyses are presented in Table 1, which shows that DAI was positively and moderately correlated with DAT (r=.22, p<.01), INTER (r=.34, p<.01), and final marks (r=.23, p<.01). DAI was moderately and negatively associated with SAI (r= -.41, p<.01) and SAT (r=-.29, p<.01). SAI had positive association with SAT (r=.28, p<.01), but negative association with DAT (r=-.14, p<.01), and INTER (r=-.13, p<.01).

|

|

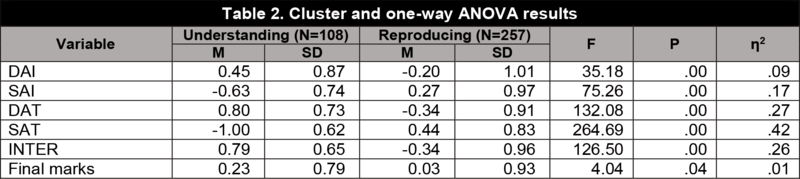

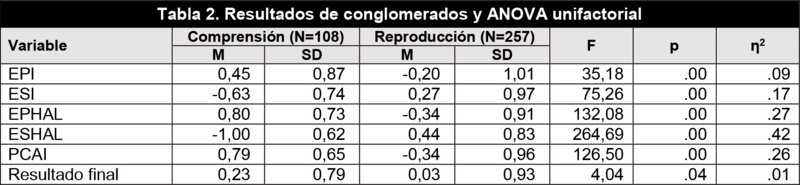

DAT was moderately and negatively related to SAT (r=-.46, p<.01), but it positively associated with INTER (r=.61, p<.01). The INTER, however, was negatively related to SAT (r=-.44, p<.01). Table 2 shows that the cluster analysis produced two clusters, which had 108 and 257 students respectively.

The scores of all the variables were standardized into z-scores, which were used in the one-way ANOVAs. One-way ANOVAs showed that cluster 1 and 2 students differed significantly on all the variables: DAI (F(1,363)=35.18, p<.01, η2=.09), SAI (F(1,363)=75.26, p<.01, η2=.17), DAT (F(1,363)=132.08, p<.01, η2=.27),SAT (F(1,363)=264.69, p<.01, η2=.42), INTER(F(1,363)=126.50, p<.01, η2=.26), and final marks (F(1,363)=4.04, p=.04, η2=.01).

|

|

Cluster 1 students reported using more DAI, DAT, and had positive ratings on INTER; which were learning oriented towards understanding of subject matter (“understanding” learning orientation); whereas cluster 2 students adopted more SAI, SAT, and had negative ratings on INTER, which were characteristics of learning towards knowledge reproducing (“reproducing” learning orientation). Understanding students achieved better academic performance than reproducing students in the course.

Results for research question 2

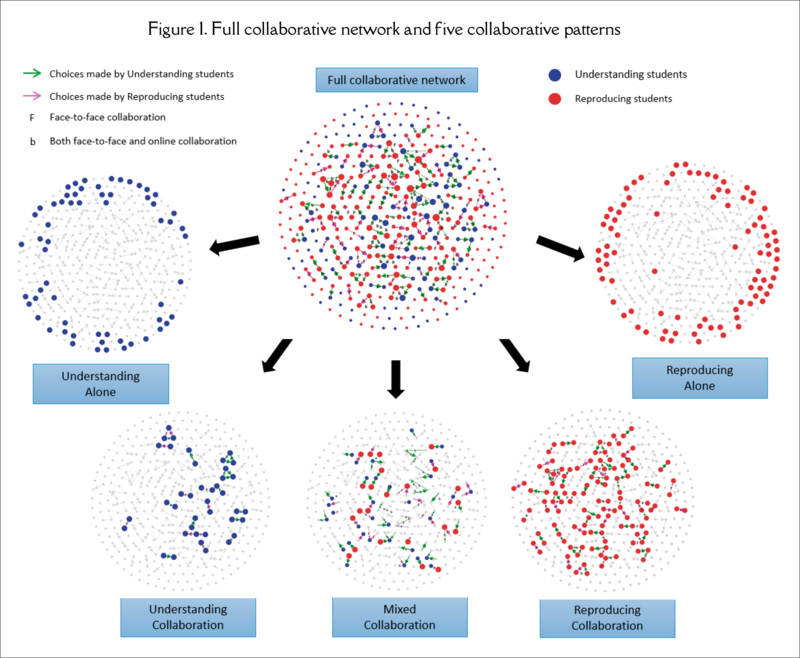

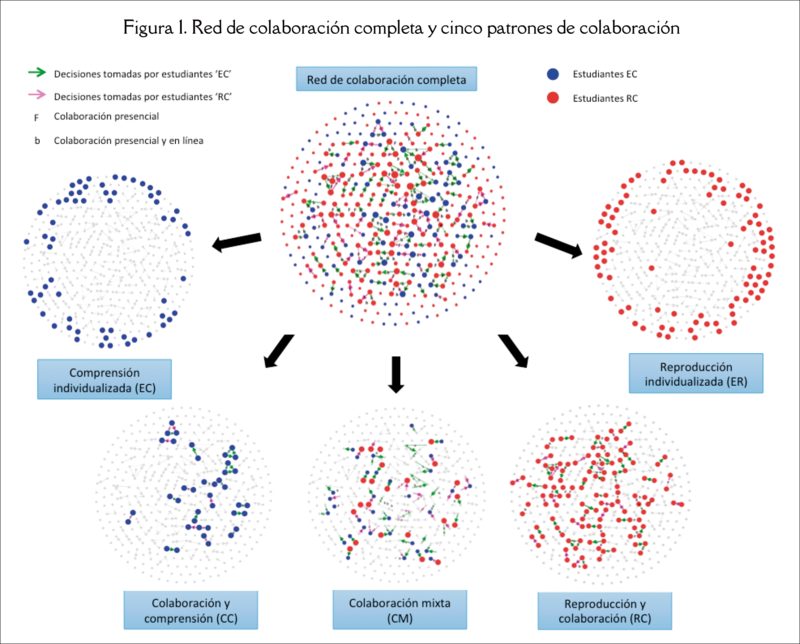

Using students’ learning orientations (understanding vs. reproducing) and their choices of collaboration (alone, collaborating with students from the same cluster, collaborating with students from a different cluster), five collaborative patterns were identified:

- Understanding Alone (UA) students had an understanding orientation but did not collaborate;

- Reproducing Alone (RA) students had a reproducing orientation but did not collaborate;

- Understanding Collaboration (UC) students had an understanding orientation and collaborated with understanding students;

- Reproducing Collaboration (RC) students had a reproducing orientation and collaborated with reproducing students;

- Mixed Collaboration (MC) students only collaborated with students having a different orientation from them.

|

|

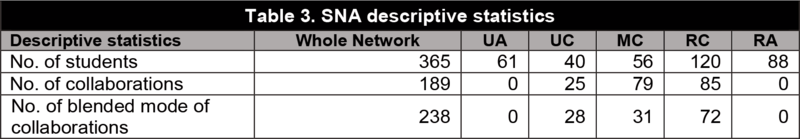

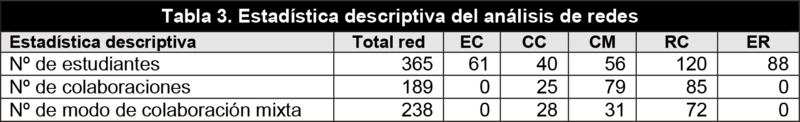

The visualization and the descriptive statistics of the five groups of students showing five collaborative patterns are presented in Figure 1 and Table 3 respectively.

|

|

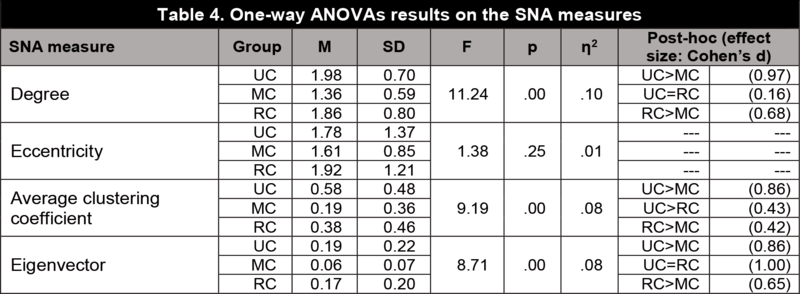

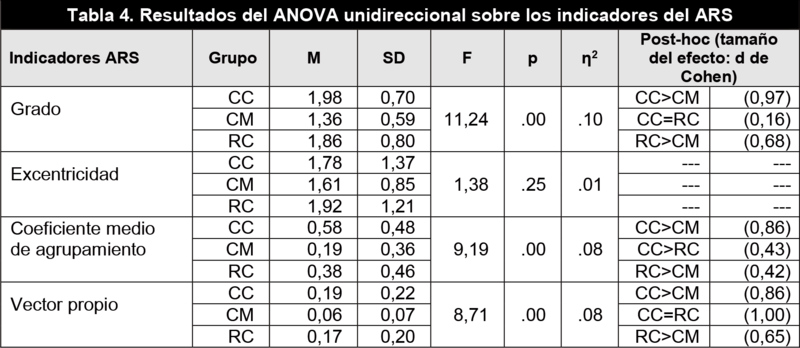

To compare the quality of students’ collaborations amongst the groups, one-way ANOVAs were applied on the key SNA measures. As the SNA measures were only available for students who collaborated, the analyses were conducted amongst UC, MC, and RC, and the results are displayed in Table 4. This table shows that the three groups of students differed significantly on degree (F(2,214)=11.24, p<.01, η2=.10), average clustering coefficient (F(2,214)=9.19, p<.01, η2=.08), and eigenvector (F(2,214)=8.71, p<.01, η2=.09).

The LSD post-hoc analyses showed that for the degree, UC and RC students had more collaboration than MC students. UC students had a higher clustering coefficient than RC students, who in turn were higher than MC students. This suggests that UC students were more likely to form closely knitted sub-networks than RC and MC students, hence they had more opportunities to directly interact with all the members in the sub-networks.

Both UC and RC students had higher eigenvector than MC students, demonstrating that UC and MC students were surrounded by others with higher quality of collaborative connections.

|

|

Results for research question 3

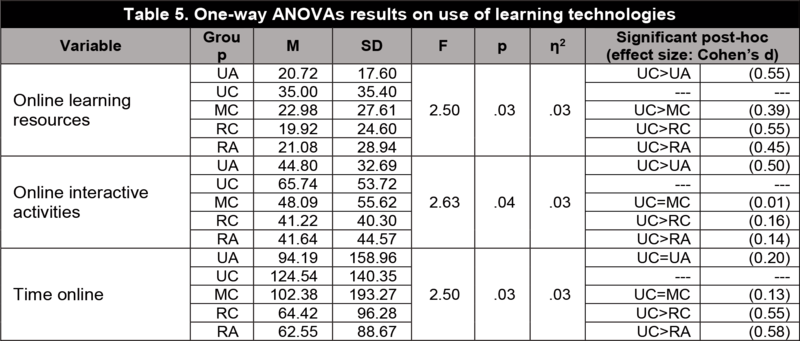

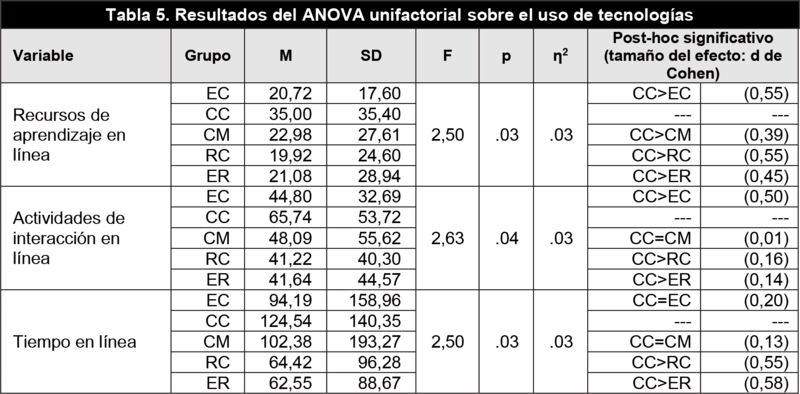

The comparison of the use of learning technologies amongst the five groups revealed the material elements of learning experience in relation to the cognitive and social elements and their academic performance, because the five groups of students representing five collaborative patterns were jointly shaped by the cognitive and social elements as well as their learning performance. Table 5 shows that the five groups differed significantly in their frequency of using online learning resources (F(4,361)=2.50, p<.05, η2=.03), online interactive activities (F(4,361)=2.63, p<.05, η2=.03), and the total time online (F(4,361)=2.50, p<.05, η2=.03). The LSD post-hoc analyses found that UC students engaged with online learning more frequently than the other four groups, except for the frequency of access to online interactive activities. There was no difference between UC and MC students. UC students also spent more time online than RC and RA students.

|

|

Discussion and conclusion

Before discussing important implications for an ecological perspective to understanding the complexity of student learning experience in blended contexts in contemporary Higher Education, some limitations are noted. The study was conducted in a science course and the participants all majored in sciences and applied sciences. The relations amongst cognitive, social, and material dimensions in their learning experience may differ from humanities and social sciences students. Before strong conclusions are drawn, similarly designed studies in a range of disciplines are warranted. Despite these limitations, the use of different types of data (self-report and observational) and evidence derived from the multiple methodologies offer some valuable insights.

From an ecological perspective on learning, this study investigated personalised learning networks of 365 first-year undergraduates in a blended course. Personalised learning networks on the university student experience emphasizes the value of an ecologically inspired approach to research into learning. The distinction between this type of investigation and closely related previous investigations is a foregrounding of measures of collaborations and materiality in student experience to complement the findings in the cognitive dimension. One of the key shifts in the methodologies used is the unit of analysis comprising both people and things, including measures of their interplay. In this study, we bring together multiple complementary methods from SAL research, social network research, and materiality in learning, to reveal the choices and decisions made by individuals and groups of students in their learning experience. Broadly summarizing, students of the most successful learning experience were UC students, as they not only performed relatively better in learning the contents of the subject matter, but they also developed their collaborative skills, an important attribute required for graduates to be ready for future employment. Apart from obtaining higher academic performance, these students reported deep approaches to learning in class and online, held positive perceptions of the integration of the learning environment, used effective strategies for collaboration, and were more engagement with learning technologies. The following explains in more details of qualitative variations amongst the elements in these three dimensions.

In terms of qualitative variations of cognitive dimension, we identified students reporting contrasting learning orientations described as “understanding” and “reproducing”. “Understanding” students reported using deep approaches to face-to-face and online learning and holding positive perceptions of the integrated learning environment. They performed academically higher in the course compared to “reproducing” students, who reported using surface approaches and holding relatively negative perceptions of how the online part of the experience was integrated into the course design. They obtained relatively lower academic outcomes. These results are consistent with previous SAL research in different academic disciplines, such as engineering (Ellis & al., 2016), business (Han & Ellis, 2019b), and social sciences (Bliuc & al., 2010) in the blended learning settings that there is a logical alignment amongst approaches to learning, perceptions of learning environment, and academic performance. Our results and the similar previous results together seem to suggest that across disciplines distinctive learning orientations are present based on students’ contrasting approaches to and perceptions of learning, highlighting the importance of the approaches and perceptions elements.

The variations in the cognitive dimension combined with students’ choices of collaboration revealed qualitative variations in the social dimension of student learning experience. The five identified groups demonstrated students’ collaborative experience with varying success: two groups chose not to collaborate (UA and RA) and three did collaborate (UC, RC, and MC). UA and RA students failed to fulfil one of the key course aims of developing teamwork and collaborative skills as an important graduate attribute. Amongst the three collaborative groups, UC students appeared to have more successful collaborative experience. They collaborated more (degree); their collaborative sub-networks tended to be closely knitted, which means that they might have more opportunities to contact directly with each member in the sub-networks (average clustering coefficient); and their neighborhood students (the students whom they directly connected to) were also well-connected in other sub-networks (eigenvector). Together, these findings suggested that UC students not only maximized their opportunities to develop collaborative skills, but also were in a position, which allowed them to gather more information and share knowledge more easily in the class compared with MC and RC students.

Looking at the elements in the material dimension, in general UC students were more engaged with the online learning activities than the other students. This was reflected by the observed evidence of their use of learning technologies. These observations of students’ actual use of learning technologies not only demonstrated significant differences in student choice of material dimension, but its consistency with students’ self-report evidence triangulates the results and reinforces the overall findings.

The results generated by different data sources and multiple methods across the three dimensions describe key aspects of students’ personalised learning networks in their learning ecologies. These unique configurations manifested by students’ decision-making processes in learning suggest how complex a learning ecology can be in a blended course design: that multifarious resources, such as people, tangible things, and virtual learning space and learning activities, are drawn and orchestrated in order to learn (Ellis & Goodyear, 2019).

The study offers some theoretical implications. The authors do not delude themselves that this is the first time the idea of an ecological perspective on learning research has been undertaken (Barnett, 2018; Cope & Kalantzis, 2017; Patterson & Holladay, 2017). However, it is the first time that complementary multiple methodologies have been brought to bear on the same population sample producing consistent results in ways that help to push onwards an ecologically informed theory of learning in higher education. The strengths of the study are: 1) its inclusion of both human and non-human elements in student blended learning experience; 2) its adoption of multiple and complementary methods, which allowed structural discovery of qualitative variations of students personalized learning networks that distinguished on the key elements across major dimensions in learning; and 3) its simultaneous use of self-report and observational data sources provides a more holistic understanding of the nature of overall student experience than collecting data from a single source. These methodological merits can be applied in the ecological theory of learning to continuously identify and expand key elements and dimensions in university students’ blended learning experience in order to better explain factors impacting on student academic success.

Our fine-grained analyses in and across each dimension also provide specific actionable evidence for teachers so that corresponding strategies can be undertaken in the following ways. The identification of less desirable student learning orientations (“reproducing”) early in course delivery can help teachers design activities to encourage students to adjust surface approaches and negative perceptions of the online context. This could be achieved through inviting “understanding” students to talk about their ways of approaching learning, and the strategies when engaging with learning technologies. Teachers could also explicitly discuss the purpose of online activities in terms of course outcomes, so that students can appreciate the coherence between face-to-face and online components in the course. These strategies may increase student engagement both in class and online.

Similarly, to promote collaboration in learning, the identification of the five groupings of students in the course can help teachers understand why not all students develop collaborative skills. Teachers could fruitfully discover these types of groupings amongst their students in order to pair them. For instance, teachers can consider assigning students who are not likely to collaborate into those collaborative groups (UC, MC, and RC groups). Likewise, teachers could mix UC students with RA and RC students so that all collaborative groups have at least one or two stronger partners.

The university student experience of learning in the current Higher Education context is growing in complexity through new pedagogies and new technologies across a variety of learning contexts. With rapid changes continually occurring, more research is required that reveals how elements across cognitive, social, and material dimensions of the student experience are related to each other and to learning outcomes.

References

- BarnettR, . 2018. , ed. ecological university: A feasible utopia&author=&publication_year= The ecological university: A feasible utopia.London: Routledge.

- BarronB, . 2004.ecologies for technological fluency: Gender and experience differences&author=Barron&publication_year= Learning ecologies for technological fluency: Gender and experience differences.Journal of Educational Computing Research 31(1):1-36

- BarronB, . 2006.and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: A learning ecology perspective&author=Barron&publication_year= Interest and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: A learning ecology perspective.Human Development 49(4):193-224

- BarronB, WiseS, MartinC, . 2013.within and across life spaces: The role of a computer clubhouse in a child’s learning ecology&author=Barron&publication_year= Creating within and across life spaces: The role of a computer clubhouse in a child’s learning ecology.LOST Opportunities.

- BiggsJ, KemberD, LeungD, . 2001.revised two-factor study process questionnaire: R-SPQ-2F&author=Biggs&publication_year= The revised two-factor study process questionnaire: R-SPQ-2F.British Journal of Educational Psychology 71:133-149

- BliucA M, EllisR, GoodyearP, PiggottL, . 2010.through face-to-face and online discussions: Associations between students’ conceptions, approaches and academic performance in political science&author=Bliuc&publication_year= Learning through face-to-face and online discussions: Associations between students’ conceptions, approaches and academic performance in political science.British Journal of Educational Technology 41(3):512-524

- BonacichP, . 2007.unique properties of eigenvector centrality&author=Bonacich&publication_year= Some unique properties of eigenvector centrality.Social Networks 29(4):555-564

- BreweE, KramerL, SawtelleV, . 2012.student communities with network analysis of interactions in a physics learning center&author=Brewe&publication_year= Investigating student communities with network analysis of interactions in a physics learning center.Physical Review Special Topics-PER 8:10101

- CadimaR, OjedaJ, MonguetM, . 2012.Social networks and performance in distributed learning communities.Educational Technology and Society 15(4):296-304

- CopeB, KalantzisM, . 2017. , ed. ecologies: Principles for new learning and assessment&author=&publication_year= E-learning ecologies: Principles for new learning and assessment.New York: Routledge.

- CrawfordK, GordonS, NicholasJ, ProsserM, . 1998.different experiences of learning mathematics at university&author=Crawford&publication_year= Qualitatively different experiences of learning mathematics at university.Learning and Instruction 8(5):455-468

- De-NooyW, MrvarA, BatageljV, . 2011. , ed. social network analysis with Pajek&author=&publication_year= Exploratory social network analysis with Pajek.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- EllisR, BliucA, . 2016.exploration into first-year university students’ approaches to inquiry and online learning technologies in blended environments&author=Ellis&publication_year= An exploration into first-year university students’ approaches to inquiry and online learning technologies in blended environments.British Journal of Educational Technology 47(5):970-980

- EllisR, BliucA, GoodyearP, . 2012.experiences of engaged enquiry in pharmacy education: Digital natives or something else?&author=Ellis&publication_year= Student experiences of engaged enquiry in pharmacy education: Digital natives or something else?Higher Education 64(5):609-626

- EllisR, GoodyearP, . 2019. , ed. education ecology of universities: Integrating learning, strategy and the academy&author=&publication_year= The education ecology of universities: Integrating learning, strategy and the academy.London: Routledge.

- EllisR, PardoA, HanF, . 2016.in blended learning environments - significant differences in how students approach learning collaborations&author=Ellis&publication_year= Quality in blended learning environments - significant differences in how students approach learning collaborations.Computers & Education 102:90-102

- EntwistleN, RamsdenP, . 2015. , ed. student learning&author=&publication_year= Understanding student learning.London: Routledge.

- FenwickT, LandriP, . 2012.textures and pedagogies: Socio-material assemblages in education&author=Fenwick&publication_year= Materialities, textures and pedagogies: Socio-material assemblages in education.Pedagogy, Culture & Society 20(1):1-7

- FenwickT, . 2014.in medical practice and learning: Attuning to what matters&author=Fenwick&publication_year= Sociomateriality in medical practice and learning: Attuning to what matters.Medical Education 48(1):44-52

- FenwickT, NerlandM, JensenK, . 2012.approaches to conceptualizing professional learning and practice&author=Fenwick&publication_year= Sociomaterial approaches to conceptualizing professional learning and practice.Journal of Education and Work 25(1):1-13

- FreemanL, . 1977.set of measures of centrality based on betweenness&author=Freeman&publication_year= A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness.Sociometry 40(1):35-41

- HanF, EllisR, . 2019.development and validation of the perceptions of the blended learning environment questionnaire&author=Han&publication_year= Initial development and validation of the perceptions of the blended learning environment questionnaire.Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment

- HanF, EllisR, . 2019.consistent patterns of quality learning discussions in blended learning&author=Han&publication_year= Identifying consistent patterns of quality learning discussions in blended learning.Internet and Higher Education 40:12-19

- JacksonN, . 2013.The concept of learning ecologies. In: JacksonN., CooperG., eds. learning, education and personal development e-book&author=Jackson&publication_year= Lifewide learning, education and personal development e-book.1-21

- KemberD, . 2015.qualitative studies beyond findings of a limited number of categories, with motivational orientation as an example&author=Kember&publication_year= Taking qualitative studies beyond findings of a limited number of categories, with motivational orientation as an example.Methodological challenges in research on student learning.

- Nelson-LairdT, SeifertT, PascarellaE, MayhewM, BlaichC, . 2014.affecting first-year students’ thinking: Deep approaches to learning and three dimensions of cognitive development&author=Nelson-Laird&publication_year= Deeply affecting first-year students’ thinking: Deep approaches to learning and three dimensions of cognitive development.Journal of Higher Education 85(3):402-432

- PattersonL, HolladayR, . 2017.learning ecologies: An invitation to complex teaching and learning&author=&publication_year= Deep learning ecologies: An invitation to complex teaching and learning. Circle Pines, MN: Human Systems Dynamics Institute.

- PintrichP, . 2004.conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students&author=Pintrich&publication_year= A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students.Educational Psychology Review 16(4):385-407

- ProsserM, TrigwellK, . 2017.Student learning and the experience of teaching.HERDSA Review of Higher Education 4:5-27

- QuardokusK, HendersonC, . 2015.instructional change: Using social network analysis to understand the informal structure of academic departments&author=Quardokus&publication_year= Promoting instructional change: Using social network analysis to understand the informal structure of academic departments.Higher Education 70(3):315-335

- RientiesB, HéliotY, Jindal-SnapeD, . 2013.social learning relations of international students in a large classroom using social network analysis&author=Rienties&publication_year= Understanding social learning relations of international students in a large classroom using social network analysis.Studies in Higher Education 66(4):489-504

- Rodríguez-HidalgoR, ZhuC, QuestierF, Torrens-AlfonsoA, . 2011.social network analysis for analysing online threaded discussions&author=Rodríguez-Hidalgo&publication_year= Using social network analysis for analysing online threaded discussions.International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research 10(3):128-146

- Tomás-MiquelJ, Expósito-LangaM, Nicolau-JuliáD, . 2016.influence of relationship networks on academic performance in higher education: A comparative study between students of a creative and a non-creative discipline&author=Tomás-Miquel&publication_year= The influence of relationship networks on academic performance in higher education: A comparative study between students of a creative and a non-creative discipline.Higher Education 71(3):307-322

- VermuntJ, DoncheV, . 2017.learning patterns perspective on student learning in higher education: State of the art and moving forward&author=Vermunt&publication_year= A learning patterns perspective on student learning in higher education: State of the art and moving forward.Educational Psychology Review 29(2):269-299

- WassermanS, FaustK, . 1994.network analysis: Methods and applications&author=&publication_year= Social network analysis: Methods and applications. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

En la Educación Superior, pocos estudios han investigado simultáneamente las dimensiones cognitivas, sociales y materiales de una misma población. Desde una perspectiva ecológica del aprendizaje, este estudio examina la interrelación entre elementos clave a partir de estas dimensiones en las redes personalizadas de 365 estudiantes. Los datos procedentes de cuestionarios, análisis de aprendizaje y calificaciones del curso permiten considerar estos aspectos en la experiencia de aprendizaje y en el rendimiento académico. Los participantes registraron niveles cualitativamente dispares en el nivel de implicación en el curso, oscilando de un enfoque orientado a la comprensión a enfoques basados en la reproducción de contenidos, lo que, junto a sus opciones de colaboración, generó cinco patrones distintos. Los resultados revelaron que una orientación más comprensiva y una cooperación con estudiantes de orientaciones similares tiende a asociarse con mejores rendimientos en el aprendizaje semipresencial. Sus redes personalizadas se caracterizaron por enfoques más profundos hacia el aprendizaje presencial y virtual; percepciones positivas hacia la integración de ambos contextos; el diseño del curso, por la forma y modo de colaboración; y por una mayor implicación en las actividades en línea. El estudio tuvo implicaciones significativas de aplicación en el desarrollo teórico de la investigación en la ecología del aprendizaje, así como en la forma de guiar el diseño del currículum, la práctica docente y el aprendizaje.

ABSTRACT

In researching student learning experience in Higher Education, a dearth of studies has investigated cognitive, social, and material dimensions simultaneously with the same population. From an ecological perspective of learning, this study examined the interrelatedness amongst key elements in these dimensions of 365 undergraduates’ personalised learning networks. Data were collected from questionnaires, learning analytics, and course marks to measure these elements in the blended learning experience and academic performance. Students reported qualitatively different cognitive engagement between an understanding and a reproducing learning orientation towards learning, which when combined with their choices of collaboration, generated five qualitatively different patterns of collaboration. The results revealed that students had an understanding learning orientation and chose to collaborate with students of similar learning orientation tended to have more successful blended learning experience. Their personalised learning networks were characterized by self-reported adoption of deep approaches to face-to-face and online learning; positive perceptions of the integration between online environment and the course design; the way they collaborated and positioned themselves in their collaborative networks; and they were more engaged with online learning activities in the course. The study had significant implications to inform theory development in learning ecology research and to guide curriculum design, teaching, and learning.

Palabras clave

Perspectiva ecológica, red de aprendizaje personalizada, interrelación, dimensión cognitiva, dimensión social, dimensión material, experiencia de aprendizaje semipresencial, estudiantes universitarios

Keywords

Ecological perspective, personalised learning network, interrelatedness, cognitive dimension, social dimension, material dimension, blended learning experience, university students

Introducción

En el contexto universitario, hoy los alumnos disponen de múltiples alternativas a la hora de elegir asignaturas, modalidades de aprendizaje (presencial o en línea), formas de enfocar el aprendizaje en un seminario, elegir con quién trabajar en un laboratorio, acudir a una biblioteca física o acceder a bases de datos en línea. Por ello, la experiencia actual del alumno universitario debería entenderse en esta serie de decisiones, que lo involucran en las distintas dimensiones de su aprendizaje. En este estudio se sostiene que cada decisión puede considerarse un factor en relación con una red de trabajo personalizado, conllevando la obtención de resultados más o menos eficaces. El objetivo del trabajo es explicar por qué algunos sistemas de trabajo resultan más eficaces que otros.

Desde una perspectiva ecológica y con vistas a establecer asociaciones entre dimensiones, el estudio examina: 1) diferencias cualitativas en redes personalizadas de aprendizaje entre alumnos de primero de Ciencias, creadas a partir de decisiones en torno al enfoque y percepción que tienen de su propio aprendizaje, sus opciones de colaboración, y el grado de implicación con herramientas tecnológicas dentro y fuera del aula en una asignatura de Biología Humana diseñada en formato semipresencial; 2) el modo en que sus decisiones están relacionadas con el desempeño académico en el curso.

Una perspectiva ecológica del aprendizaje

El término ‘ecología’ se emplea para describir las interacciones dinámicas entre organismos y el medio que les rodea, donde se entrelazan intrincadamente diversos factores (Ellis & Goodyear, 2019). Trasladando la metáfora ecológica al aprendizaje, Barron (2006: 1995) define la ecología del aprendizaje como «el conjunto de contextos localizados en espacios físicos o virtuales que proporcionan oportunidades para el aprendizaje. Cada contexto comprende una configuración única de las actividades, recursos materiales, relaciones e interacciones que emergen de ellos mismos». De la misma forma, Jackson (2013: 2) describe la ecología de aprendizaje del individuo entendiendo que «comprende sus procesos y un conjunto de contextos e interacciones que le proporcionan oportunidades y recursos de aprendizaje, desarrollo y rendimiento. Cada contexto incluye una configuración única de finalidades, actividades, recursos materiales, relaciones e interacciones y aprendizaje intermedio que emergen del mismo». Estas dos definiciones comparten similitudes en torno a la percepción del aprendizaje como un sistema dinámico desde una perspectiva ecológica, y dicho ecosistema está constituido por interdependencias entre aprendientes y su interconexión con la gente y los numerosos recursos materiales (Ellis & Goodyear, 2019).

Hasta la fecha, contamos con un limitado número de estudios que hayan adoptado la perspectiva ecológica en el aprendizaje. De ellos, la mayoría ha tenido lugar en el contexto escolar (Barron, 2004; Barron, Wise, & Martin, 2013). Una de las limitaciones ha sido el manejo de un único método, la entrevista o la observación, dificultándose así una visión más holística. Este estudio pretende suplir esas carencias, investigando la ecología de las experiencias de aprendizaje en estudiantes universitarios mediante la aplicación de métodos complementarios y uso de diferentes fuentes. Entendiendo las ecologías de aprendizaje como interdependencias entre aprendientes y su interconexión con personas y elementos de su entorno, consideramos tres dimensiones en la experiencia de aprendizaje: cognitiva, social y material. La primera está relacionada con estados internos del alumno, interdependientes a otros alumnos y a otros elementos no humanos que conviven en el aprendizaje, mientras que las otras dos dimensiones se centran más en aspectos relacionados con lo social y material, respectivamente. Para el análisis, seleccionamos una serie de elementos de cada dimensión, incluyendo enfoques y percepciones del aprendizaje (dimensión cognitiva), con quién y cómo se establecen las colaboraciones en el proceso (dimensión social), y el grado de implicación en el uso de tecnologías dentro y fuera del aula (dimensión material). El análisis de la interacción de estos elementos revela características que resultan de mayor o menor eficacia en las redes de aprendizaje, aportando información importante para educadores con vistas a mejorar la experiencia de aprendizaje.

Planteamos la hipótesis de que, en redes eficaces, los elementos se presentan alineados y coherentes, ayudando al estudiante a desarrollar un conocimiento de la materia y asistiéndole en la consecución de resultados. En redes de menor calidad, los estudiantes son susceptibles de perder elementos clave que pueden presentarse fragmentados, impidiendo la comprensión y generando un desempeño académico menos satisfactorio. El estudio de las variaciones en las múltiples dimensiones proporcionará una evidencia holística que revela rasgos estructurales de las redes más eficaces con el objetivo de mejorar el aprendizaje. Las razones para adoptar una perspectiva ecológica incluyen:

- La constatación de que las experiencias de aprendizaje en el contexto universitario están constituidas por múltiples elementos en varias dimensiones que interactúan, son dinámicas, difíciles de desmembrar y se presentan interrelacionadas. Por ello, solo analizando esas interrelaciones puede explicarse por qué algunos estudiantes obtienen mejores resultados que otros.

- La sinergia entre metodologías complementarias con el objetivo de desvelar la complejidad de las experiencias en clase y en entornos virtuales.

- La inclusión de diferentes fuentes de datos, incluyendo la autoevaluación y la observación para la triangulación de los resultados de la investigación.

Entendiendo las ecologías de aprendizaje como interdependencias entre aprendientes y su interconexión con personas y elementos de su entorno, consideramos tres dimensiones en la experiencia de aprendizaje: cognitiva, social y material.

Basándose en estas premisas, el estudio aplica las metodologías propuestas en tres áreas: 1) el enfoque de los estudiantes hacia el aprendizaje (Pintrich, 2004; Prosser & Trigwell, 2017); el análisis de redes sociales (De-Nooy, Mrvar, & Batagelj, 2011; Wasserman & Faust, 1994); 3) la materialidad en el aprendizaje (Fenwick, 2015; Fenwick & Landri, 2012). El uso combinado se justifica porque: 1) tratan de revelar explícita e implícitamente variaciones cualitativas cuando se emplean para investigar el aprendizaje; 2) tienen capacidad para analizar las experiencias de aprendizaje tanto a nivel individual como a nivel grupal en contextos presenciales o virtuales; y 3) son coherentes con la perspectiva ecológica, social y científica hacia la experiencia de aprendizaje adoptada en este estudio.

Análisis del enfoque de los estudiantes hacia el aprendizaje (SAL)

El análisis SAL se utilizó con el objetivo de identificar elementos cognitivos clave en la experiencia de aprendizaje, que explicaran las diferencias cualitativas en el rendimiento académico en la Educación Superior (Kember, 2015). Estudios influyentes han demostrado que la manera en que los estudiantes se comportan ante el aprendizaje (su enfoque) y la forma en que lo perciben (percepciones) están vinculadas a su rendimiento (Entwistle & Ramsden, 2015). Trasladando este marco al contexto semipresencial, se han demostrado asociaciones lógicas entre enfoques hacia el aprendizaje presencial y en línea, y percepciones del contexto de aprendizaje semipresencial: aquellos estudiantes que perciben una buena integración de ambos tienden a adoptar enfoques más profundos hacia el aprendizaje y el uso de la tecnología, lo que a su vez se asocia positivamente a un mejor rendimiento académico (Ellis, Pardo, & Han, 2016). Estos enfoques más profundos son proactivos, demuestran implicación, reflexión y análisis y ayudan a lograr un conocimiento significativo de la materia de estudio (Nelson-Laird, Seifert, Pascarella, Mayhew, & Blaich, 2014). Cuando no se aprecia relevancia entre el aprendizaje presencial y virtual, se tiende a adoptar una perspectiva más superficial y a obtener resultados más pobres (Ellis & al., 2016). Este enfoque implica la adopción de estrategias más simples, muy dependientes de ideas predecibles y mecánicas concebidas para completar estrictamente las tareas asignadas y aprobar exámenes (Vermunt & Donche, 2017). En este trabajo analizamos como elementos cognitivos los enfoques hacia el aprendizaje presencial y en línea, y las percepciones acerca del contexto de aprendizaje semipresencial.

Análisis de redes sociales (ARS)

Con sus raíces en la sociología, el Análisis de Redes Sociales (ARS) busca identificar, detectar e interpretar el papel de los individuos en un grupo y los patrones de conexión entre individuos (De-Nooy & al., 2011; Wasserman & Faust, 1994). En educación, el análisis de redes ha investigado los vínculos entre el trabajo y la discusión entre docentes (Quardokus & Henderson, 2015), las características de las redes de interacción formales e informales entre estudiantes (Cadima, Ojeda, & Monguet, 2012), la relación entre vínculos de amistad y resultados de aprendizaje (Brewe, Kramer, & Sawtelle, 2012; Rienties, Héliot, & Jindal-Snape, 2013), la comunicación en línea entre estudiantes (Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Zhu, Questier, & Alfonso, 2015), y las asociaciones entre redes de aprendizaje y rendimiento académico (Tomás-Miquel, Expósito-Langa, & Nicolau-Julia, 2015). El presente estudio busca, ante la falta de investigaciones existentes en este sentido, analizar las relaciones subyacentes entre los enfoques, las percepciones del contexto de aprendizaje semipresencial, y la calidad de las colaboraciones. Los indicadores de colaboración servirán como elementos sociales a considerar en la experiencia de aprendizaje.

Materialidad y aprendizaje

El análisis de lo material en el aprendizaje se centra en una unidad combinada de ‘personas y cosas’ (artefactos), y en cómo su combinación contribuye a crear, consolidar y diseminar conocimiento. Basado en el constructivismo social, cuestiona el papel aislado de los factores humanos y todo aquello que está en un primer plano en el aprendizaje (Fenwick, 2014). De ahí que objetos, cosas y artefactos no sean considerados como significados meramente atribuidos por los individuos, sino «en continuidad con y de hecho integrados en lo inmaterial y en lo humano» (Fenwick, Nerland, & Jensen, 2012: 6). Esta área de investigación ha explorado la experiencia del aprendizaje a través de la configuración de alumnos y objetos tangibles e intangibles, como tareas de aprendizaje en clase y en línea (Ellis & Goodyear, 2019). En este estudio, el uso de la tecnología se emplea como elemento en la dimensión material de la experiencia de aprendizaje.

Preguntas de investigación

El estudio se fundamenta en tres preguntas de investigación:

1) ¿Qué relaciones existen entre elementos cognitivos de la experiencia de aprendizaje y el rendimiento académico?

2) ¿Qué relaciones se establecen entre elementos cognitivos y sociales y el rendimiento académico?

3) ¿Qué relaciones existen entre elementos cognitivos, sociales y materiales y el rendimiento académico?

Materiales y método

Participantes

En el estudio participaron 365 estudiantes de primer año universitario (251 mujeres, 113 hombres de entre 18 y 53 años, M=19, 72: SD=3,55) pertenecientes a una universidad australiana, tras un proceso de selección acorde a los preceptos éticos de la institución. Todos se matricularon en una asignatura semestral de Biología Humana en formato semipresencial. Los alumnos procedían de varias facultades: Ciencias de la Salud (162), Enfermería (22), Farmacia (55), y Ciencias (124). Dos estudiantes no aportaron información sobre su facultad.

Contexto de aprendizaje

La carga presencial incluía una sesión semanal de dos horas, una sesión de laboratorio de tres horas cada dos semanas, y un taller de dos horas en semanas alternas. El componente en línea requería de seis a nueve horas de dedicación en actividades semanales y de colaboración. Un objetivo importante era desarrollar habilidades colaborativas y de trabajo en equipo. Para ello se animó a los estudiantes a trabajar en pequeños grupos, realizar experimentos en el laboratorio y escribir conjuntamente informes científicos en los talleres. El curso no constaba solo de contenidos curriculares, sino que incluía también el desarrollo de otras competencias, incluyendo investigación, pensamiento crítico y creativo, y trabajo colaborativo.

Fuente de datos e instrumentos

Los datos obtenidos proceden de: 1) un cuestionario basado en una escala Likert de cinco puntos con preguntas sobre enfoques y percepciones hacia el aprendizaje (elementos cognitivos); 2) un cuestionario de redes sociales para valorar la colaboración entre estudiantes (elementos sociales); 3) análisis de aprendizaje en línea en base a la frecuencia y la duración de las interacciones con las herramientas de aprendizaje en línea (elementos materiales); 4) resultados finales (rendimiento académico de los estudiantes).

Cuestionario de escala Likert

El desarrollo y validación de las escalas en el cuestionario ya ha sido demostrado con anterioridad en estudios (Bliuc, Ellis, Goodyear, & Piggott, 2010; Ellis & Bliuc, 2016; Han & Ellis, 2019a) que confirmaron su fiabilidad y validez. El conjunto de ítems se constituyó a partir de las entrevistas y de la revisión de la literatura existente sobre enfoques y aproximaciones del alumno hacia el aprendizaje. Se consideraron además cuestionarios previos en el marco del SAL (Biggs, Kember, & Leung, 2001; Crawford, Gordon, Nicholas, & Prosser, 1998). Para validar las escalas se llevaron a cabo análisis de ítems, análisis factorial exploratorio, análisis de fiabilidad de la escala, análisis factorial confirmatorio y test de invarianza (Han & Ellis, 2019a).

- La escala de “Enfoques en profundidad hacia la investigación” (EPI: 5 ítems; α=.71) describe los enfoques hacia el aprendizaje a través de la investigación, que se caracterizan por ser proactivos e independientes, con un pensamiento sólido de continuar con una línea (por ejemplo: “siempre persigo vías o caminos independientes cuando investigo sobre algo”).

- La escala de “Enfoques superficiales hacia la investigación” (ESI: 4 ítems; α=.63) contiene estrategias menos elaboradas a nivel de pensamiento, más simples y mecánicas, muy dependientes de otros (por ejemplo: “Buscar información para una tarea implica solo utilizar recursos que me proporciona el profesor”).

- La escala de “Enfoques en profundidad hacia herramientas de aprendizaje en línea” (EPHAL: 5 ítems; α=.72) evalúa el uso de la tecnología como forma de promover un conocimiento más profundo de ideas clave para facilitar la investigación, conectar conceptos de la asignatura con problemas del mundo real (por ejemplo: “Pasé tiempo utilizando las herramientas de aprendizaje de la asignatura para conectar ideas clave con contextos reales”).

- La escala de “Enfoques superficiales hacia las herramientas de aprendizaje en línea” (ESHAL: 4 ítems; α=.66) describe el uso de la tecnología con un alcance limitado a satisfacer los requisitos del curso más que a promover el aprendizaje (por ejemplo: “Solo utilizo las herramientas para cumplir con los requisitos del curso”).

La escala “Percepciones de contexto de aprendizaje integrado” (PCAI: 6 ítems, α=.88) evalúa hasta qué punto la percepción de los estudiantes del aprendizaje presencial (conferencias, ideas y conceptos clave presentados) y en línea (recursos en línea, sitio web, actividades) son coherentes y están integrados (por ejemplo: “Las actividades en línea me ayudaron a entender las lecciones”).

Cuestionario de redes

El cuestionario examinó las decisiones de los estudiantes sobre colaboradores y formas de colaboración. Nombraron hasta tres compañeros según la frecuencia y forma de colaboración establecida. Por ejemplo: “Por favor, enumera a tres estudiantes con los que hayas colaborado en esta asignatura en función de la frecuencia, y rodea el modo de colaboración (F=presencial, B=presencial y en línea). El más frecuente: F-B; El segundo más frecuente: F-B; El tercero más frecuente: F-B.

Análisis del aprendizaje en línea

Este apartado se centró en la frecuencia y duración de uso de las herramientas en línea y las actividades de interacción. Los recursos en línea (horario, objetivos de aprendizaje, calificaciones, materiales de lectura, videoconferencias, apuntes e imágenes digitales), proporcionaron el andamiaje y los materiales necesarios. Las actividades de interacción (preguntas de respuesta múltiple, rellenar con conceptos, relacionar, redactar, preguntas de respuesta corta y juegos de cartas) posibilitaron la interacción con conceptos relacionados con la Biología y la recepción de comentarios y retroalimentación sobre las respuestas.

Resultados finales

A los resultados finales (entre 32 y 90 puntos, M=67,93; SD=10,13) se añadieron: 1) cuestionarios sumativos para las sesiones de laboratorio (15%); 2) presentación oral de un estudio de caso (8%); 3) publicaciones en línea posteriores a cada taller (3%); 4) retroalimentación entre pares en los borradores de informes científicos (4%); 5) versión final del informe científico (20%); 6) examen final (50%). A excepción del punto cuatro, el resto de pruebas fueron evaluadas por el profesorado. El examen consistió en preguntas de respuesta múltiple basadas en los materiales del curso.

Recogida de datos

Los cuestionarios se completaron en clase al final del semestre. Se aseguró a los estudiantes que una vez sus respuestas fueran combinadas con los datos del análisis del aprendizaje en línea y sus resultados finales, se asignarían códigos para sustituir sus nombres.

Análisis de datos

Para responder a la primera pregunta se emplearon la correlación, el análisis de conglomerados y un análisis de varianza unifactorial (ANOVA). Los análisis de correlación examinaron las relaciones entre pares y el análisis de conglomerados y el ANOVA revelaron interrelaciones entre grupos de variables. Para la segunda pregunta, se aplicó el ARS usando Gephi, que visualiza patrones colaborativos y calcula indicadores clave, incluyendo el grado, la excentricidad, el coeficiente medio de agrupamiento y el vector propio (Bonacich, 2007). Los indicadores del ARS a través de diferentes patrones colaborativos se compararon utilizando un ANOVA unifactorial. Para la tercera pregunta, se utilizaron un ANOVA unifactorial y un análisis post-hoc, con el fin de examinar la frecuencia y el tiempo dedicados al uso de tecnologías entre patrones de colaboración, diseñados conjuntamente en base a las decisiones de los alumnos y a los elementos cognitivos y sociales.

Resultados

Resultados de la primera pregunta de investigación

El resultado de los análisis de correlación (Tabla 1) muestra que EPI (“Enfoques en profundidad hacia la investigación”) correlaciona positiva y moderadamente con EPHAL (“Enfoques en profundidad hacia herramientas de aprendizaje en línea”) (r=.22, p<.01), PCAI (r=.34, p<.01) (“Percepciones de contexto de aprendizaje integrado”) y con los resultados finales (r=.23, p<.01).

|

|

EPI correlaciona moderada y negativamente asociado con ESI (“Enfoques superficiales hacia la investigación”) (r=-.41, p<.01) y ESHAL (“Enfoques superficiales hacia las herramientas de aprendizaje en línea”) (r=-.29, p<.01). ESI tiene una asociación positiva con ESHAL (r=.28, p<.01), pero negativa con EPHAL r=-.14, p<.01), y PCAI (r=-.13, p<.01).

EPHAL se relaciona moderada y negativamente con ESHAL (r=-.46, p<.01), pero se asocia positivamente con PCAI (r=.61, p<.01). PCAI, sin embargo, correlaciona negativamente con ESHAL (r=-.44, p<.01). La Tabla 2 muestra que el análisis de agrupamiento produjo dos conglomerados con 108 y 257 estudiantes respectivamente. Los resultados de las variables se estandarizaron en puntaje z y se utilizaron en el ANOVA unifactorial.

|

|

El ANOVA mostró que en los conglomerados uno y dos los estudiantes se diferenciaron significativamente en todas las variables: EPI (F(1,363)=35.18, p<.01, η2=.09), ESI (F(1,363)=75.26, p<.01, η2=.17), EPHAL (F(1,363)=132.08, p<.01, η2=.27), ESHAL (F(1,363)=264.69, p<.01, η2=.42), PCAI (F(1,363)=126.50, p<.01, η2=.26), y en el resultado final (F(1,363)=4.04, p=.04, η2=.01).

En el primer conglomerado los estudiantes afirmaron hacer un mayor uso de EPI, EPHAL, y obtuvieron puntuaciones positivas en PCAI, lo que se reflejó en una aproximación mayor hacia la comprensión de la materia (una orientación del aprendizaje enfocada a la “comprensión”), mientras en el segundo conglomerado se registraron valores mayores de ESI, EPHAL y se obtuvieron valores negativos en PCAI, asociados a la “reproducción”.

Los estudiantes que profundizaron en el enfoque orientado a la comprensión obtuvieron mejores resultados académicos.

Resultados de la segunda pregunta de investigación

A partir de las orientaciones (comprensión frente a reproducción), y opciones de colaboración (solos, con estudiantes de su mismo grupo o de grupos diferentes), se identificaron cinco patrones colaborativos:

- Comprensión individual (EC): una orientación hacia la comprensión, pero sin colaboraron.

- Reproducción individual (ER): una orientación hacia la reproducción de lo aprendido, pero sin colaboraron.

- Comprensión y colaboración (CC): una orientación hacia la comprensión y colaboraron con otros estudiantes con mismo enfoque.

- Reproducción y colaboración (RC): una orientación hacia la reproducción de lo aprendido, colaborando con estudiantes de su mismo perfil.

- Colaboración mixta (CM): solo colaboraron con estudiantes que tenían una orientación distinta.

|

|

En la Figura 1 y en la Tabla 3 aparecen los resultados de los cinco grupos de estudiantes y los cinco patrones de colaboración.

Con el objetivo de comparar la calidad de las colaboraciones, se aplicó un ANOVA unifactorial sobre los principales indicadores del ARS. Puesto que los indicadores solo estaban disponibles para estudiantes que habían colaborado, el análisis se llevó a cabo entre los grupos de CC, CM y RC. Los resultados se muestran en la Tabla 4.

|

|

La Tabla 4 muestra que los tres grupos de estudiantes difieren significativamente en el grado (F(2,214)=11.24, p<.01, η2=.10), coeficiente medio de agrupamiento (F(2,214)=9.19, p<.01, η2=.08), y vector propio (F(2,214)=8.71, p<.01, η2=.09).

|

|

El análisis post-hoc de mínima diferencia significativa (LSD por sus siglas en inglés), sugiere que, en el grado, los grupos CC y RC colaboraron más que los del grupo CM. CC registró un coeficiente de agrupamiento mayor que RC, a su vez mayor que el de CM.

Esto alude a que los estudiantes del grupo CC fueron más proclives a la formación de sub-redes que los grupos de RC y CM. De ahí también que tuvieran más oportunidades de interactuar de forma directa con todos los miembros de las sub-redes. Tanto los estudiantes CC como RC obtuvieron un vector propio mayor que los del grupo CM, demostrando que los estudiantes CC y CM estaban rodeados de otros con conexiones colaborativas de mayor calidad.

Resultados de la tercera pregunta de investigación

La comparación del uso de tecnologías en los tres grupos reveló los elementos materiales en relación con los elementos cognitivos, sociales y el rendimiento académico, dado que los cinco grupos de estudiantes representantes de los cinco patrones de colaboración se configuraron conjuntamente a partir de dichos elementos. La Tabla 5 muestra que los cinco grupos difieren significativamente en la frecuencia de uso de los recursos en línea (F(4,361)=2.50, p<.05, η2=.03), actividades de interacción en línea (F(4,361)=2.63, p<.05, η2=.03), y en el tiempo total en línea (F(4,361)=2.50, p<.05, η2=.03). Los análisis post-hoc de mínima diferencia significativa muestran que los estudiantes CC se involucraron con mayor frecuencia en el aprendizaje en línea en comparación con los otros, a excepción de la frecuencia de acceso a las actividades en línea, donde no se registró diferencia entre CC y CM. Los estudiantes CC pasaron más tiempo conectados que RC y ER.

|

|

Discusión y conclusiones

Antes de citar implicaciones importantes de la perspectiva ecológica sobre la complejidad de las experiencias en contextos semipresenciales en la educación universitaria actual, cabe señalar algunas limitaciones. El estudio se realizó en un curso científico donde los participantes dominaban la materia de estudio. Las relaciones entre las dimensiones cognitiva, social y material podrían diferir en estudiantes de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales. Por lo que, antes de extraer conclusiones firmes, habrían de garantizarse estudios similares en otras disciplinas. A pesar de estas limitaciones, el uso de diferentes tipos de datos (autoevaluación, observación) y la evidencia que se deriva de las múltiples metodologías utilizadas arrojan algunos puntos de vista valiosos.

Desde una perspectiva ecológica del aprendizaje, este estudio abarca la investigación de redes de aprendizaje personalizadas pertenecientes a 365 estudiantes de primer año universitario en una asignatura semipresencial. Las redes personalizadas en la experiencia universitaria enfatizan el valor de un enfoque inspirado en la ecología hacia la investigación del aprendizaje. El punto diferenciador reside en que los indicadores de colaboración y materialidad en la experiencia del estudiante se ponen en primer plano como complemento a los resultados en la dimensión cognitiva. Uno de los cambios más importantes en la metodología es la unidad de análisis, que incluye a su vez personas y cosas, así como indicadores de la interacción entre ellos. En este trabajo se aúnan distintos métodos complementarios: la investigación en el enfoque del estudiante hacia el aprendizaje, el análisis de redes y la materialidad para revelar las decisiones tomadas por individuos y grupos durante su experiencia de aprendizaje. A grandes rasgos, los estudiantes con mayor rendimiento fueron los del grupo CC: no solo se desenvolvieron mejor frente a los contenidos, sino que además desarrollaron destrezas colaborativas (un atributo importante requerido en futuros empleos). Además de obtener un mejor rendimiento, desarrollaron enfoques más profundos hacia el aprendizaje (tanto en clase como en línea), mantuvieron percepciones positivas sobre la integración del contexto de aprendizaje, aplicaron estrategias efectivas de colaboración, y se implicaron más con las tecnologías de aprendizaje. A continuación, se detallan las variaciones cualitativas entre elementos en estas tres dimensiones.

En la dimensión cognitiva, se identificaron dos tipos diferenciados de orientación hacia el aprendizaje: una enfocada a la “comprensión” y otra a la “reproducción”. Los primeros resultaron tener aproximaciones más profundas hacia el aprendizaje presencial y en línea, así como percepciones positivas sobre el contexto de aprendizaje integrado. Obtuvieron mejor rendimiento en el curso en comparación con el segundo grupo, que desarrolló un enfoque más superficial y unas percepciones relativamente negativas sobre la integración de la parte virtual en el diseño del curso. Alcanzaron calificaciones relativamente más bajas. Estos resultados coinciden con investigaciones previas en otras disciplinas, como el área de Ingeniería (Ellis & al., 2016), Gestión de Empresas (Han & Ellis, 2019b), y Ciencias Sociales (Bliuc & al., 2010) en contextos de aprendizaje semipresencial, indicando que hay una relación lógica entre aproximaciones al aprendizaje, percepciones del contexto y rendimiento académico. Considerando otros estudios y nuestros resultados, parece sugerirse que en distintas disciplinas existen orientaciones de aprendizaje diversas basadas en los enfoques de los estudiantes y en sus percepciones, señalándose así la importancia de ambos elementos.

Las variaciones en la dimensión cognitiva en combinación con las opciones de colaboración revelaron variaciones cualitativas en la dimensión social. Los cinco grupos que se identificaron registraron varios grados de éxito en la colaboración: dos grupos decidieron no colaborar entre ellos (EC y ER) y los tres restantes sí (CC, RC y CM). Los dos primeros no lograron cumplir uno de los principales objetivos, que consistía en desarrollar un grupo de trabajo y habilidades de colaboración. De los tres restantes, los primeros (CC) lograron una colaboración más exitosa. Colaboraron más (grado); sus sub-redes fueron más estrechas, con más oportunidades de contacto directo con cada miembro (coeficiente medio de agrupamiento); y sus estudiantes paralelos (aquellos con los que conectaron de forma directa) también se conectaron a su vez con otras sub-redes de colaboración (vector propio). Estos hechos muestran que los estudiantes de este grupo no solo maximizaron sus oportunidades de desarrollar habilidades de colaboración, sino que además pudieron reunir más información y compartir conocimiento más fácilmente en clase que los estudiantes CM y RC.

Si observamos los elementos de la dimensión material, el grupo CC se mostró más involucrado en las actividades de aprendizaje en línea, de acuerdo a los resultados que se observan en el uso de tecnologías. Estas observaciones acerca del uso real de estas herramientas no solo demuestran diferencias significativas en la elección de los estudiantes en esa dimensión material, sino que además su consistencia con los resultados de la autoevaluación triangula los resultados y evidencia los resultados globales.