Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This paper examines the academic use made of the social networks by university students through a survey conducted among a representative sample of students at Universidad de Málaga (Spain) (n=938) and two discussion groups. Given that network consumption has profoundly penetrated the daily routines of the students, the vast communication possibilities of these channels could be considered for educational use in the future despite a predominance of entertainment-related use. We discuss the most suitable networks for academic use, which type of activities may be most widely accepted among the students and which social networking tools could be most useful for academic purposes. The results indicate that consumption of social networks in the student population surveyed is very high. In addition, the students show a favourable attitude to lecturers using social networks as an academic resource. However, the frequency of use of such networks for academic activities was rather low and, on average, the most frequently used academic activities are those initiated by the students themselves, such as answering queries among peers or doing coursework. The perceived low academic support on social networks may mean that lecturers take only limited advantage of their potential.

1. Introduction

Universities are facing classfuls of digitally native students who are demanding a new kind of teaching. They have been brought up under the influence of audiovisuals and the web. The new technological tools (social networks, blogs, video platforms, etc) have given them the power to share, create, inform and communicate and have become an essential element in their lives.

All the applications or social media to have emerged from the Web 2.0 entail active participation by the users, who have become both producers and recipients. Particularly worthy of note are the social networks, which have become a true mass phenomenon (Flores, 2009). In fact in Spain, as shown by the Social Networks Observatory (January 2011), «The Cocktail Analysis», 85% of web surfers are users, with two active accounts per user on average.

Social networks have gone universal. Young people have fully incorporated them into their lives. They have become the ideal space in which to exchange information and knowledge in a swift, simple and convenient way. Teachers may be able to take advantage of this situation and of the students' predisposition to using social networks to incorporate them into their teaching. «The use of social networks, blogs, video applications implies (…) taking information and education to the places that students associate with entertainment, and where they may approach them with fewer prejudices » (Alonso & Muñoz de Luna, 2010: 350). Thus, De la Torre (2009) points out that it is no longer a waste of time for young people to browse the internet or to use social networks, as they are assimilating technological and communications competences that are crucial in the contemporary world. This means that, together with a merely social use, as a space and a route for communication, information and entertainment, networks possess vast potential for the educational sphere, and evidence is emerging that students are favourably disposed towards the academic use of social networks (e.g.: Espuny, González, Lleixà & al., 2011).

In the juncture of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA), the social media in general and the social networks in particular provide several ways for addressing the challenges of higher education, both from the technical and the educational point of view. In fact some of their inherent characteristics, such as collaboration, free dissemination of information or generation of own content for the construction of knowledge have been applied on an immediate basis to the educational field (De Haro, 2010). This means that the student develops some of the competences highlighted by the EHEA: personal (self-learning and critical thought, recognition of diversity); instrumental (visual culture, computer skills); or systematic (research potential or case-based learning) (Alonso & López, 2008).

The networks permit and favour the publication and sharing of information; self-learning; teamwork; communication, both between students and between pupil-teacher; feedback; access to other sources of information that support or even facilitate constructivist learning and collaborative learning; and contact with experts. As a whole, all of these applications and resources make learning more interactive and significant and above all allow it to develop in a more dynamic environment (Imbernón, Silva & Guzmán, 2011).

This is why its use and familiarisation can be very helpful both in the learning phase and for the student's professional future, given that the vast majority of businesses are already employing such applications in the performance of their functions.

2. Material and methods

The objective of our research is to describe the academic use that college students make of commercial social networks. We employed a methodological design that combines qualitative and quantitative techniques. The weight of the quantitative part was greater, as we sought to extrapolate the results to the surveyed population as a whole. The essential method in this work was a descriptive survey of a sociological nature.

The surveyed population was constituted by undergraduate and graduate students registered at Universidad de Málaga (UMA). The population size was set at 32,464 students, according to the figures provided by the latest available official statistics published (SCI, 2010).

The population is spread over five branches of learning. Each branch is divided into degrees and undergraduate and graduate studies. According to the statistics, the proportion in each branch of learning and in each cycle with regard to the population total is the following: undergraduate students, 69.91% and graduate students, 30.09%; Law and Business Science, 58.70% of the total of individuals; Technical, 22.57%; Humanities, 7.33%; Health Sciences, 5.79%, and Experimental Sciences, 5.61%.

Sampling of a probabilistic type by conglomerates was used, corresponding to the five branches of learning (e.g.: Experimental Sciences, Health Sciences, Humanities, Technical and Law and Business Science) for each cycle. The choice of degree holder to be interviewed in each conglomerate was made in a simple random way based on the use of a computer program. The population structure was preserved by setting the quota of the cycle and branches of learning, then calculating the proportional number of surveys to be conducted according to the relative weight of the quota in the population structure. The size of the sample set for the study was 1033 students for a confidence level of 95% and a confidence interval of +/-3%.

A specific questionnaire was designed for the research. We adapted to the research objectives some questions from other questionnaires that had been reviewed in existing scientific literature (AIMC, 2011; Caballar, 2011; Valenzuela, Park & Kee, 2009; Ledbetter, Mazer & al., 2010; Ellison, Steinfield & Lampe, 2007; Monge & Olabarri, 2011) and new questions emerging from two discussion groups were drafted.

The objectives of the groups were to explore the field and extract qualitative information. A convenience criterion was applied to the selection of participants (Journalism and Advertising and Public Relations students). The size of the groups was seven and ten participants. The interview lasted no more than an hour and a half. A themed script was used for moderating, which in the first half of the sessions gave little direction to allow the discourses to emerge naturally, with more direction given in the second half in order to clarify specific issues on the content of the questionnaire. The audio of the sessions was recorded and then transcribed, coded and analysed.

The questionnaire was later redrafted and an exploratory pilot study was conducted. All the questions except for one were closed. Likert-type, five-point self-applied scales were employed (e.g.: scales of quantity, frequency or degree of accord), which provided averages and deviations. In addition, dichotomic multiple-answer questions were also used as well as questions with category-type answers. The questions explored the frequency with which the networks are used for different academic-type activities in a normal week (e.g.: doing coursework), the degree of academic support perceived in the networks, the monitoring of the university through the networks, the academic relationship between students and teachers through them, or the students' assessment of the possibility that teachers would use them as a teaching resource in detriment of the virtual campus. In addition to these, the questionnaire obtained other socio-demographic data and data on consumer habits and general uses that shall not be given an in-depth treatment in this paper.

The fieldwork was performed during the second week of April 2011. The group of survey takers was constituted by 21 research volunteers who gleaned specific information on how to administer the surveys and assist with any doubts among the respondents. The data obtained through the survey generated a database that was analysed with the scientific software PASW Statistics v.18. After reviewing and refining the data matrix, the classic resources of descriptive statistics were used, such as summary statistics, frequency tables and graphics.

3. Results

After discarding erroneous and incomplete surveys, the final size of the sample was 938 students. The distribution of respondents by learning area was as follows: Social Sciences and Law, 60%; Technical, 25.4%; Health Sciences, 6.6%; Experimental Sciences, 4.3%, and Humanities, 3.7%. Moreover, 68.01% of respondents were undergraduate students and 31.9% graduate students. 54.8% of respondents were women against 45.2% of men. And the average age was 21.62 years (SD=3.878).

Before describing the specific results on the academic use of social networks, we must briefly highlight some of the data referring to their consumption. The use of social networks is widely extended among the university population. 91.2% of respondents admitted using a social network. The data and percentages that we henceforth recount have therefore been calculated according to this base (n=855) of network users.

On average, respondents use 2.25 networks (SD=1.19). From among them, the one used by the highest percentage is Tuenti (89%), followed by Facebook (74.9%) and Twitter (25.5%). Other networks do not in themselves attract more than 7% of respondents (e.g.: MySpace, Fotolog, LinkedIn, Hi5, Xing, Flickr). The use of networks among university students has become a quotidian activity that forms part of their daily lives. The majority connects to the networks several times a day (53%), with the most intense consumption occurring between 19.00 and 00.00 hours. Furthermore, on average they agree that «the use of social networks forms part of their habitual tasks» (M=3.43. SD=1.301) (Likert scale of 1 completely disagree to 5 completely agree).

On average, respondents spend a fair amount of time connected to the networks from their homes (M=4.21. SD=0.944) (scale of 1 not at all to 5 a great deal), and while they connect fairly little while in college (M=2.29. SD=1.082), it takes second place in connection time. Asked for the reason why they use the networks, respondents most often answered «to keep up with what is happening in my social environment» (75% of respondents), «for entertainment» (61.8%) and «to study» (24.7%). In addition, college students are experienced users of networks, as almost all respondents (97.3%) have been participating in them for more than a year.

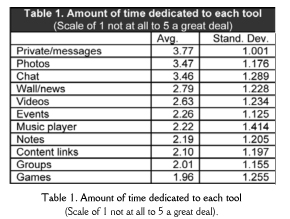

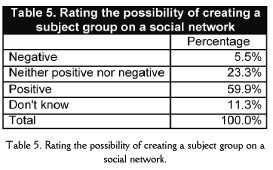

The students were asked about the amount of time they dedicate to the use of the different tools provided by the networks (Likert scale of 1 not at all to 5 a great deal). Private messages are the most widely used tool, with photos and chats also being habitually used. In contrast, the averages for the rest of the tools point to fairly limited use (table 1).

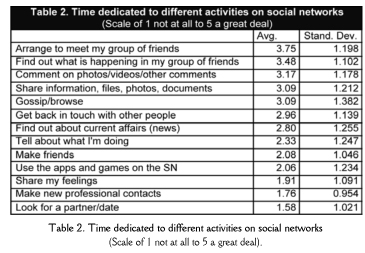

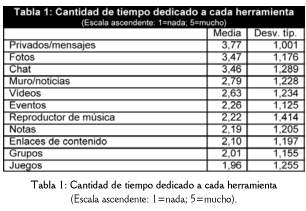

Within a single space, networks allow you to perform multiple activities. From among the possible ones, those to which students dedicate the most time are: «arranging to meet up with my group of friends» (M=3.75. SD=1.198); «finding out what is happening in my group of friends» (M=3.48. SD=1.102); «commenting on photos/videos» (M=3.17. SD=1.178); and «sharing information, files, photos, documents» (M=3.09. SD=1.212) (table 2). These data confirm the conclusions of the report «The Information Society in Spain 2010», which reports that while penetration of networks is increasing (from 28.7% in 2009 to 50% in 2010) and its use as a form of communication is growing (from 2% in 2008 to 13% in 2010), there is a decrease in the use of text messages (with a drop in invoicing of 19.3% between 2009 and 2010), in landline telephony (8.3% less than in 2009), in mobile telephony (4.1%) and email (from 91% in 2009 to 88.6% in 2010).

3.1. Academic use of social networks

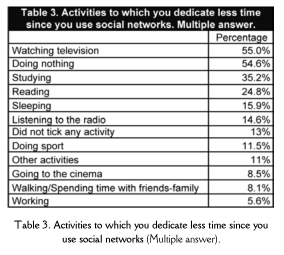

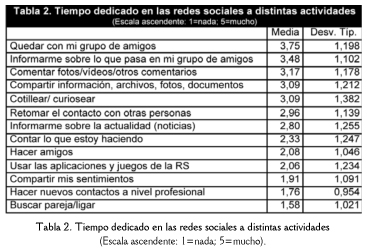

The principal objective of our research was to learn about the academic use of social networks that students make. First, we asked ourselves whether the networks were just a new distraction from university studies. The majority of respondents indicates that time has been taken from other activities to dedicate it to the networks. More than half of students dedicate less time to «watching television» and to «doing nothing». Social networks are therefore taking up leisure time. However, activities with an academic profile such as «studying» and «reading» were also pinpointed by a relevant percentage of respondents (table 3).

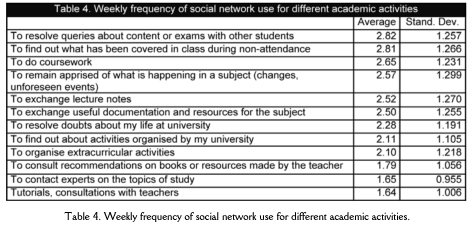

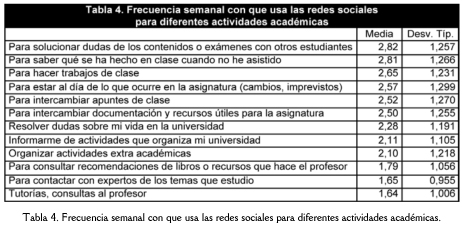

We specifically asked for the academic activities they performed through the social networks. None of the academic activities suggested has attained the average of three on a five-point scale, with 5 being very frequently. This means that on average they are infrequently performed. To resolve queries about a subject, whether in the day-to-day or at exam time; to remain apprised of the pace of the class; and to perform group tasks are on average the activities most frequently performed, though the averages indicate that the tasks are not very frequent. The less habitual ones encourage communication with experts and teachers. These are activities that hardly ever take place (table 4).

When consulted about the academic support they find on social networks, students on average tend to disagree (Likert Scale from 1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree) with whether they can find people on the networks who will help them to resolve subject-related queries relating to subjects (M=2.75. SD=1.249) or to exams (M=2.61. SD=1.266); find people with whom to share and do coursework (M=2.71. SD=1.258) or who will provide them with useful materials for studying (M=2.63. SD=1.249); and to consult general problems relating to their studies (registration, grants, accommodation, etc) (M=2.66. SD=1.258). We can therefore deduce from the answers that students do not perceive that there is any academic support from other people on the networks. Perhaps this indicates that the activities are always initiated by the students and rarely at the indication of the teacher. Proof of this is that there are very few students who have included one of their university lecturers among their network contacts: only 17.5%, against 82.5% who have not done so. And there are even fewer who follow a teacher on Twitter; only 8%.

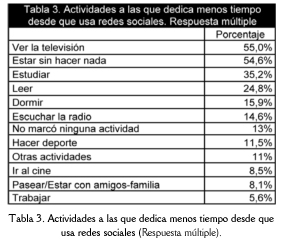

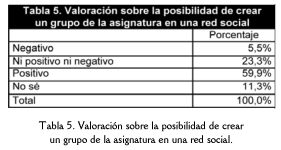

The survey data indicated that an important percentage of students (42.6%) had included among their contacts the institutional profile of Universidad de Málaga, something that points to their interest in their studies. However, in order to examine more in depth the expectations of the didactic use made of the networks, we asked the students about the possibility of creating subject groups on one of the social networks. The results are clearly striking, particularly because more than half welcomed it. Generally, those who do not or who are indifferent extend this attitude (as we could see in the qualitative analysis) to the use of the ICTs in general. They are known as pessimistic or anti-ICT students (Gutiérrez, Palacios & Torrego, 2010) (table 5). Given the possibility of using a social network in replacement of the university's virtual campus, the percentages are fairly even, although those who think it is positive visibly stand out (39.8%). 20.4%, in turn, view it as negative; 27.9% neither positive nor negative, and 11.9% don't know.

4. Discussion and conclusions

Basing upon the data obtained, we find ourselves with a paradox. On one hand, university students make intensive use of social networks, which form part of their lives and their everyday tasks – they are practically «connected» all day long. On the other, the academic application and use they make of social networks is scarce, given that the frequency with which they performed all the academic activities surveyed was low according to their scores. Furthermore, the vast majority of students did not have a teacher among their contacts on the networks, nor did they follow them on Twitter. And perceived academic support on the networks was rather scant.

It is likely that the reason for the limited academic use of social networks that students make is, above all, that both the teaching staff and the institutions give it very little importance. Our research has disclosed that the use of networks for academic activities almost always occurred at the initiative of the students and almost never at the initiative of the lecturer, as we were able to substantiate in the discussion groups. Among the reasons that might justify this situation, we can resort to Gutiérrez, Palacio & Torrego (2010), who point out that educational innovation occurs at a slower rate than that at which society evolves and is consequently slower than the rate of technological innovation. The possibilities for interpersonal communication and collaboration afforded by the networks are thus barely made use of in formal education, where educational value is given to interpersonal relations. In this line, Richmond, Rochefort & Hitch (2011) highlight the limited impact that the networks have on current formal teaching. We deduce from this that formal traditional learning is still very deep-rooted in universities, where communication is always unidirectional (teacher-pupil) and where the student finds it more difficult to participate and feel integrated.

The generational gap between students (digital natives) and teachers (digital immigrants) makes it imperative for teachers to acquire training and skills in the use and handling of such tools and to adapt to these new environments. Teachers must become acquainted with, select, create and utilise teaching intervention strategies within the context of the ICTs and within EHEA (Area, 2006; Ruzo & Rodeiro, 2006). That is to say, teaching planning cannot ignore the active and social use of the social networks (Duart, 2009).

In our study, students displayed a positive attitude to using social networks with educational purposes. In fact, among the principal reasons for «study» use, it occupies third place; in addition, the majority of students (59.9%) believes it is positive to create subject groups in one of the social networks; and 39.8% would replace the virtual campus as an educational platform with the social networks. These same positive attitude trends stand out in the above-mentioned study by Espuny, González, Lleixà & al. (2011), where the students did not display a negative attitude towards the educational use of the social networks.

Despite the potentiality of the social networks in the academic sphere, it cannot go unnoticed that «studying» is the third activity from which time was taken in benefit of the social networks, a trend that must be reversed to make educational use of the amount of time they spend on the networks. Once again this leads us to the idea that teachers have an important role to play in fostering the students' academic use and participation. From the lecture room, the lecturer can motivate students' interest. This is why he or she has to convey that this is a tool to support classroom work and that the content they generate and devote to it forms part of their learning, in addition to fostering active participation and cohesion as a group (Castañeda, 2010).

When a lecturer does decide to use social networks in his or her teaching, he or she has to choose one from among the wide range available on the internet. According to the data, we can discuss which commercial networks are the ones that best adapt to the educational sphere, not only for their suitability for teaching practice but also for the greater and skilled use that students make of them, their ease of use and the fact that they are open websites with a low technological profile. In keeping with this reasoning, according to the data of our study – similar to those of other contemporary studies (Tapia, Gómez, Herranz de la Casa & al., 2010 – the ideal networks would be Tuenti, Facebook and, to a lesser extend owing to its reduced penetration, Twitter. Nevertheless, we opt for Facebook owing to its greater possibilities in regard to applications (fora, chat, texts, videos, etc) and content creation (production of pages). The first strategy of any teacher could consist of creating a group on Facebook with the actual name of the subject, an action that would be given a favourable reception by almost two thirds of the students, according to the survey data .

Even while knowing that the didactic or educational uses of the social networks are not the ones that attract the greatest attention among university student respondents, we have still been able to pinpoint several teaching activities performed on these networks: resolving queries, keeping abreast of what is happening in the classroom, group work and sharing information. That is to say, all of them are issues that can be summed up in one main idea: creation and exchange of knowledge. These activities are always undertaken among fellow students, among the group of peers. They occur at the students' own initiative and in an informal and spontaneous manner. Teachers could therefore reinforce them as well as offering the students new optics and formulas to make more academic use of the networks.

According to the assertions of the participants in the discussion groups, using the social networks for such tasks does not entail any additional effort; on the contrary, they discover multiple advantages in them when it comes to sharing information, getting projects done, interacting among them and with lecturers. Such attitudes match the results of other studies (Espuny, González, Lleixà & al., 2011), where students considered that the social networks were especially profitable from the educational point of view.

The academic-type activities that were most often performed in the sample were directly linked to the new active and participative methodologies advocated by the EHEA, that is to say, the exchange and development of knowledge among reduced groups of peers. The introduction of these «well-conceived» activities into the lecture room could entail a change in the educational culture; breach the limitation of space and time; expedite collaborative work; foster ongoing learning; increase student motivation; foster cooperation, collaboration and cohesion within the group; foster self-learning, responsibility and independence; foster dialogue and communication between students, between students and teachers and between students and experts; foster critical thought; share and improve collective personal knowledge; reduce costs, effort and time; optimise the way the work is performed; facilitate the exchange of information; provide up-to-date and accessible information; provide a collaborative documentation system based on a self-publishing mechanism; increase freedom in the way the work is organised; and facilitate access to experts.

In short, we cannot rule out the academic use of social networks in the future, given the degree to which it forms part of the daily routine of university students. Despite a predominance in entertainment-centric use, the positive attitude of the students and the vast communicational possibilities of these channels also enable the didactic use of the social networks so long as the teachers suitably plan and manage these resources. We thus coincide with Castañeda (2010) in that while the educational potential of the social networks is huge, the challenge will consist in awakening the interest of the institutions, teachers and students to integrate them as basic teaching tools.

Given that we have found evidence of the students' positive attitude and of a low – though existing – use of the networks for academic purposes, future studies might bring their attention to bear on several research questions such as the following: what are the attitudes of the teaching staff to the idea of incorporating social networks into their teaching practices? What use are teachers giving to the networks? Specifically which type of activities? With which educational purposes? How do they assess them? And, of course, and in our view the most relevant one: does the use of social networks in teaching really imply a significant increase in student learning?

Notes

During the 2011/12 academic year a pilot experience in this line will be undertaken in the subject of General Structure of the Media System in the Journalism degree, imparted at Universidad de Málaga.

Support

This work is part of the PIE 08.045 Educational Innovation Project financed by University of Malaga.

References

Alonso, H. & López, I. (2008). Adaptando asignaturas al EEES: el caso de Teoría y Técnica de la Publicidad. In Rodríguez, I. (Ed.). El nuevo perfil del profesor universitario en el EEES. Claves para la renovación metodoló-gica. Valladolid: Universidad Europea Miguel de Cervantes.

Alonso, M.H. & Muñoz de Luna, A.B. (2010). Uso de las nuevas tecnologías en la docencia de Publicidad y Relaciones Públicas, en Sierra, J. & Sotelo, J. (Coords.). Métodos de innovación docente aplicados a los estudios de Ciencias de la Comunicación. Madrid: Fragua; 348-358.

Area, M. (2006). La enseñanza universitaria en tiempo de cambio: El papel de las bibliotecas en la innovación educativa. IV Jornadas CRAI. Red de Bibliotecas Universitarias (REBIUN). Burgos: Universidad de Burgos, 10-12 mayo 2006.

Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación (AIMC). (2011) Navegantes en la Red. Encuesta AIMC a usuarios de Internet. Octubre-diciembre 2010. AIMC (http://download.aimc.es/aimc/navred2010/ma-cro2010_cuest.pdf) (10-03-2011).

Caballar, J.A. (2011). Cuestionario sobre redes sociales online. Grupo de Investigación SEJ494. E-Business. Em-presa, Administración y Ciudadano (http://edoctorado.es) (07-03-2011).

Castañeda, L. (2010). Aprendizaje con redes sociales. Tejidos educativos para los nuevos entornos. Sevilla: MAD.

De Haro, J.J. (2010). Redes Sociales para la educación. Madrid: Anaya.

De la Torre, A. (2009). Nuevos perfiles en el alumnado: la creatividad en nativos digitales competentes y expertos rutinarios. Revista Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento, 6, 1; 9.

Duart, J.M. (2009). Internet, redes sociales y educación. Revista Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento, 6, 1; 1-2.

Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C. & Lampe, C. (2007). The Benefits of Facebook Friends: Social Capital and College Students Use of Online Social Network Sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12; 1143-1168.

Espuny, C.; González, J. & al. (2011). Actitudes y expectativas del uso educativo de las redes sociales en los alumnos universitarios. Revista de Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento (RUSC), 8, 1; 171-185.

Flores, J.M. (2009). Nuevos modelos de comunicación, perfiles y tendencias en las redes sociales. Comunicar, 33; 73-81.

Gutiérrez, A.; Palacios, A. & Torrego, L. (2010). Tribus digitales en las aulas universitarias. Comunicar, 34; 173-181.

Imbernón, F.; Silva, P. & Guzmán, C. (2011). Competencias en los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje virtual y semipresencial. Comunicar, 36; 107-114.

Ledbetter, A.M.; Mazer, J.P. & otros (2010). Attitudes Toward Online Social Connection and Self-Disclosure as Predictors of Facebook Communication and Relational Closeness. Communication Research, 38, 1; 27-53.

Monge, S. & Olabarri, M.E. (2011). Los alumnos de la UPV/EHU frente a Tuenti y Facebook: usos y percep-ciones. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 66; 79-100 (www.revistalatinacs.org/11/art/925_UPV/04_-Monge.html) (01-03-2011).

Richmond, N.; Rochefort, B. & Hitch, L.P. (2011). Using Social Networking Sites During the Career Management Process, en Wankel, L.A & Wankel, C. (Eds.). Higher Education Administration with Social Media : Including Applications in Student Affairs, Enrolment Management, Alumni Affairs, and Career Centers. Bingley (UK): Emerald.

Ruzo, S. & Rodeiro, D. (2006). Enseñanza-aprendizaje, en Uceda, J. & Senén, B. (Coords.). Las TIC en el sistema universitario español 2006: un análisis estratégico. Madrid: CRUE.

Servicio central de informática (2010). Estadísticas de alumnos. Grado 1º y 2º ciclo. Curso 2009-2010. Málaga: Universidad de Málaga.

Tapia, A.; Gómez, B. & al. (2010). Los estudiantes universitarios ante las redes sociales: cuestiones de uso y agrupación en estructuras elitistas o pluralistas. Vivat Academia, 113 (www.ucm.es/info/vivataca/numeros/n-113/DATOSS.htm) (25-02-2011).

Valenzuela, S.; Park, N. & Kee, K.F. (2009). Is There Social Capital in a Social Network Site?: Facebook Use and College Students Life Satisfaction, Trust and Participation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14; 875-901.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El uso académico que hacen los universitarios de las redes sociales es el estudio que se presenta a partir de una encuesta administrada a una muestra representativa de estudiantes de la Universidad de Málaga (n=938) y dos grupos de discusión. Dado que el consumo de redes se ha implantado profundamente en las rutinas diarias de los estudiantes, las vastas posibilidades comunicativas de estos canales podrían considerarse para sacar provecho educativo en el futuro, a pesar del predominio del uso dirigido al entretenimiento. Se discuten cuáles son las redes más adecuadas para su uso académico, qué tipo de actividades pueden tener mejor acogida entre los estudiantes y qué herramientas de las redes sociales podrían ser más útiles para propósitos académicos. Los resultados indican que el consumo de redes sociales de la población estudiada es muy alto. Así mismo, los estudiantes presentan una actitud favorable a que los docentes utilicen las redes como recurso educativo. Sin embargo, la frecuencia con la que los estudiantes dan un uso académico a las redes es más bien escasa y, en promedio, las actividades académicas con frecuencia de uso más elevada son aquellas que parten de la iniciativa de los propios estudiantes, como la solución de dudas inter pares o la realización de trabajos de clase. Del escaso apoyo académico percibido en las redes por los estudiantes, se deduce un limitado aprovechamiento por parte de los docentes.

1. Introducción

La universidad se enfrenta a aulas de nativos digitales que demandan un nuevo tipo de enseñanza. Los universitarios han crecido bajo la influencia del audiovisual y de la Red. Las nuevas herramientas tecnológicas (redes sociales, blogs, plataformas de vídeo, etcétera) les han dado el poder de compartir, crear, informar y comunicarse, convirtiéndose en un elemento esencial en sus vidas.

Todas las aplicaciones o medios sociales, surgidas de la Web 2.0, suponen la participación activa de los usuarios, convirtiéndose a la vez en productores y destinatarios. Destacan las redes sociales que se han convertido en un auténtico fenómeno de masas (Flores, 2009). De hecho, en España, tal y como muestra el Observatorio de Redes Sociales (enero de 2011), «The Cocktail Analysis», el 85% de los internautas son usuarios, con una media de dos cuentas activas por usuario.

Las redes sociales se han universalizado. Los jóvenes las han incorporado plenamente en sus vidas. Se han convertido en un espacio idóneo para intercambiar información y conocimiento de una forma rápida, sencilla y cómoda. Los docentes pueden aprovechar esta situación y la predisposición de los estudiantes a usar redes sociales para incorporarlas a la enseñanza. «El uso de redes sociales, blogs, aplicaciones de vídeo implica (…) llevar la información y formación al lugar que los estudiantes asocian con el entretenimiento, y donde es posible que se acerquen con menores prejuicios» (Alonso & Muñoz de Luna, 2010: 350). De la Torre (2009) señala que ya no es una pérdida de tiempo para los jóvenes navegar por Internet o el uso de redes sociales, ya que están asimilando competencias tecnológicas y comunicativas muy necesarias para el mundo contemporáneo. Así, junto al uso meramente social, como espacio y vía de comunicación, información y entretenimiento; la redes poseen un enorme potencial para el ámbito educativo, habiendo evidencias de que los estudiantes presentan una actitud favorable al uso académico de las redes sociales (e.g.: Espuny, González, Lleixà & otros, 2011).

En la coyuntura del Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior (EEES), los medios sociales, en general, y las redes sociales, en particular, proporcionan varias maneras de hacer frente a los desafíos de la enseñanza superior, tanto desde el punto de vista técnico como pedagógico. De hecho, algunas de sus características propias, tales como colaboración, libre difusión de información o generación de contenidos propios para la construcción del conocimiento han sido aplicadas de inmediato al campo educativo (De Haro, 2010). De esta forma, el alumno desarrolla algunas de las competencias señaladas por el EEES: personales (autoaprendizaje y pensamiento crítico, reconocimiento de la diversidad); instrumentales (cultura visual, habilidades informáticas); o sistemáticas (potencial investigador o aprendizaje a través de casos) (Alonso & López, 2008).

Las redes permiten y favorecen publicar y compartir información, el autoaprendizaje; el trabajo en equipo; la comunicación, tanto entre alumnos como entre alumno-profesor; la retroalimentación; el acceso a otras fuentes de información que apoyan e incluso facilitan el aprendizaje constructivista y el aprendizaje colaborativo; y el contacto con expertos. En conjunto, todas estas aplicaciones y recursos hacen que el aprendizaje sea más interactivo y significativo y sobre todo que se desarrolle en un ambiente más dinámico (Imbernón, Silva & Guzmán, 2011).

Por todo ello, su utilización y familiarización puede ser de gran ayuda tanto en la etapa de formación, como en el futuro profesional, donde la gran mayoría de las empresas manejan ya estas aplicaciones en el desarrollo de sus funciones.

2. Material y métodos

El objetivo de nuestra investigación es describir el uso académico que hacen los estudiantes universitarios de las redes sociales comerciales. Nos servimos de un diseño metodológico en el que combinamos técnicas cualitativas y cuantitativas. El peso de lo cuantitativo fue mayor, pues se pretende extrapolar los resultados al conjunto de la población estudiada. El método fundamental en este trabajo fue la encuesta descriptiva de carácter sociológico.

La población de estudio estuvo constituida por los estudiantes matriculados en primer o segundo ciclo en la Universidad de Málaga (UMA). El universo de la población se fijó en 32.464 estudiantes, según las cifras proporcionadas por las últimas estadísticas oficiales publicadas disponibles (SCI, 2010).

La población se distribuye en cinco ramas de enseñanza. Dentro de cada rama, se reparte en titulaciones, y estudios de primer y segundo ciclo. De acuerdo a las estadísticas, la proporción de cada rama de enseñanza y de cada ciclo respecto del total de la población es la siguiente: estudiantes de primer ciclo, 69,91% y estudiantes de segundo ciclo, 30,09%; Ciencias Jurídicas y Empresariales, el 58,70% del total de los individuos; Técnicas, 22,57%; Humanidades, 7,33%; Ciencias de la Salud, 5,79%, y Ciencias Experimentales, 5,61%.

Se usó un muestreo de tipo probabilístico por conglomerados, correspondientes a las cinco ramas de enseñanza (Ciencias Experimentales, Ciencias de la Salud, Humanidades, Técnicas, y Ciencias Jurídicas y Empresariales) por cada ciclo. La elección de la titulación a entrevistar dentro de cada conglomerado se hizo de forma aleatoria simple a partir de la utilización de un programa informático. Se preservó la estructura poblacional a través de la fijación de las cuotas de ciclo y ramas de enseñanza, por tanto, se calculó el número proporcional de encuestas a realizar en función del peso relativo de la cuota en la estructura de la población. El tamaño de la muestra fijada para en el estudio fue de 1.033 estudiantes para un nivel de confianza del 95% y un intervalo de confianza del +/-3%.

Se diseñó un cuestionario específico para la investigación. Se adaptaron a los objetivos de la investigación algunas preguntas de otros cuestionarios revisados en la literatura científica existente (AIMC, 2011; Caballar, 2011; Valenzuela, Park & Kee, 2009; Ledbetter, Mazer & al., 2010; Ellison, Steinfield & Lampe, 2007; Monge & Olabarri, 2011) y se redactaron nuevas preguntas que surgieron de dos grupos de discusión.

Los objetivos de los grupos de discusión eran explorar el campo y extraer información cualitativa. Se usó un criterio de conveniencia para la selección de los participantes (estudiantes de Periodismo y Publicidad y Relaciones Públicas). El tamaño de los grupos de discusión fue de siete y diez participantes. La duración no superó la hora y media. Se usó un guión temático para la moderación que fue poco directiva durante la primera mitad de las sesiones, con la finalidad de que los discursos surgieran de manera natural, y más directiva en la segunda mitad, con la intención de aclarar cuestiones específicas sobre el contenido del cuestionario. El audio de las sesiones fue grabado para su posterior transcripción, codificación y análisis.

Posteriormente, se reelaboró el cuestionario y se realizó un estudio piloto y exploratorio. Todas las preguntas, excepto una, fueron cerradas. Se emplearon escalas autoaplicadas tipo Likert de cinco puntos (escalas de cantidad, frecuencia o grado de acuerdo…) con las que se obtuvieron promedios y desviaciones. Así mismo, también se utilizaron preguntas de respuesta múltiple dicotómicas y preguntas con respuestas de tipo categórico. Las preguntas exploraban la frecuencia con que se aprovechan las redes para distintas actividades de tipo académico en una semana normal (hacer trabajos de clase), el grado de apoyo académico percibido en las redes, el seguimiento a la institución universitaria a través de las redes, la relación académica existente entre estudiantes y profesores a través de ellas, o la valoración de los estudiantes sobre la posibilidad de que los profesores las utilizaran como un recurso en su docencia en detrimento del campus virtual. Además de éstas, el cuestionario recabó otros datos sociodemográficos, de hábitos de consumo y usos generales, que no serán tratados en profundidad en este artículo.

El trabajo de campo se realizó durante la segunda semana de abril de 2011. El grupo de encuestadores estuvo constituido por 21 voluntarios de investigación que recibieron formación específica sobre cómo suministrar las encuestas y asistir las dudas de los encuestados. A partir de los datos obtenidos a través de la encuesta, se generó una base de datos que fue analizada con el software científico PASW Statistics v.18. Tras la revisión y refinamiento de la matriz de datos, se utilizaron los recursos clásicos de la estadística descriptiva como son los estadísticos de resumen, las tablas de frecuencia y las gráficas.

3. Resultados

Tras la eliminación de las encuestas erróneas e incompletas, el tamaño final de la muestra fue de 938 estudiantes. La distribución de los encuestados por área de enseñanza fue la siguiente: Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas, 60%; Técnicas, 25,4%; Ciencias de la Salud, 6,6%; Ciencias Experimentales, 4,3%, y Humanidades, 3,7%. Por otra parte, el 68,01% de los encuestados fueron estudiantes de primer ciclo y el 31,9% de segundo ciclo. El 54,8% de los encuestados fueron mujeres frente al 45,2%, hombres. Y la edad promedio fue de 21,62 años (DT=3,878).

Antes de describir los resultados específicos sobre uso académico de las redes sociales, es preciso apuntar brevemente algunos datos referidos a su consumo. El uso de las redes sociales está ampliamente extendido entre la población universitaria. El 91,2% de los encuestados se reconoció como usuario de alguna red social. Por tanto, los datos y los porcentajes que relatamos a partir de ahora se han calculado a partir de esta base (n=855) de usuarios de las redes.

Los encuestados utilizan de promedio 2,25 redes (DT=1,19). Entre ellas, la empleada por el mayor porcentaje es Tuenti (89%), seguida de Facebook (74,9%) y Twitter (25,5%). Otras redes no acaparan por sí mismas a más del 7% de encuestados (MySpace, Fotolog, Linkedin, Hi5, Xing, Flickr). El uso de las redes entre los universitarios se ha convertido en una actividad cotidiana, pasando a formar parte de su vida diaria. La mayoría se conecta a las redes varias veces al día (53%), siendo el consumo más intenso entre las 19,00 y las 00,00 horas. Así mismo, de promedio están de acuerdo con que «el uso de las redes sociales forma parte de sus tareas habituales» (M=3,43. DT=1,301) (escala Likert de 1 nada de acuerdo a 5 muy de acuerdo).

Los encuestados pasan de media bastante tiempo conectados a las redes desde su casa (M=4,21. DT=0,944) (escala de 1 nada a 5 mucho), y aunque en la universidad se conectan más bien poco (M=2,29. DT=1,082), es el segundo lugar en tiempo de conexión. Preguntados por el motivo por el que usan las redes, los encuestados señalaron con mayor frecuencia «por estar al tanto de lo que ocurre en mi entorno social» (75% de los encuestados), «por entretenimiento» (61,8%) y «por estudios» (24,7%). Así mismo, Los universitarios son usuarios experimentados en el uso de las redes, ya que casi la totalidad de los encuestados (97,3%) participan en ellas desde hace más de un año.

Los estudiantes fueron preguntados por la cantidad de tiempo que dedican al uso de las distintas herramientas incluidas en las redes (escala Likert de 1 nada a 5 mucho). Los mensajes privados son la herramienta más utilizada, siendo el uso de fotos y chat también bastante habituales. Por el contrario, los promedios del resto de herramientas indican una utilización bastante limitada (tabla 1).

Las redes permiten, en un mismo espacio, realizar múltiples actividades. De entre las posibles, aquellas a los que los alumnos dedican más tiempo se encuentran: «quedar con mi grupo de amigos» (M=3,75. DT= 1,198); «informarme sobre lo que pasa en mi grupo de amigos» (M=3,48. DT=1,102); «comentar fotos/vídeos» (M=3,17. DT=1,178); y «compartir información, archivos, fotos, documentos» (M=3,09. DT=1,212) (tabla 2). Estos datos confirman las conclusiones del informe «La Sociedad de la Información en España 2010», donde se recoge que mientras aumenta la penetración de las redes (de un 28,7% en 2009 a un 50% en 2010), y aumenta su uso como forma de comunicación (de un 2% en 2008 a un 13% en 2010); baja el uso de los SMS (cuya facturación cae un 19,3% entre 2009 y 2010), de la telefonía fija (un 8,3% menos que en 2009), de telefonía móvil (un 4,1%) y del correo electrónico (pasa de un 91% en 2009 a un 88,6% en 2010).

3.1. Uso académico de las redes sociales

El principal objetivo de nuestra investigación era conocer el uso académico que los alumnos hacen de las redes sociales. Primero, nos preguntamos si las redes estaban suponiendo una nueva distracción a los estudios de los universitarios. La mayoría de los encuestados señala que ha restado tiempo a otras actividades para dedicarlo a las redes. Más de la mitad de los estudiantes dedican menos tiempo a «ver la televisión» y a «estar sin hacer nada». Luego, las redes sociales están ocupando el tiempo de ocio. No obstante, actividades de con perfil académico como «estudiar» y «leer» también fueron señaladas por un porcentaje relevante de encuestados (tabla 3).

Se preguntó de manera específica por las actividades académicas que realizaban a través de las redes sociales. Ninguna de las actividades académicas planteadas ha alcanzado la media de tres en una escala de cinco puntos, siendo 5 mucha frecuencia. Por tanto, se realizan de promedio con muy poca frecuencia. Solucionar dudas sobre la materia, ya sea en el día a día o en época de exámenes; estar informado del ritmo de la clase; y la realización de trabajos en grupo son las actividades realizadas con mayor frecuencia de promedio, aunque sus medias indican que no son tareas muy frecuentes. Las menos habituales concitan a la comunicación con expertos y con los docentes. Se trata de actividades que casi nunca tienen lugar (tabla 4).

Consultados por el apoyo académico que encuentran en las redes sociales, los estudiantes están, de promedio, más bien en desacuerdo (Escala Likert de 1 nada de acuerdo a 5 muy de acuerdo) con que en las redes puedan encontrar a gente que les ayude a resolver dudas relacionadas con las asignaturas (M=2,75. DT=1,249) o con los exámenes (M=2,61. DT=1,266); encontrar a gente con la que poder compartir y realizar trabajos de clase (M=2,71. DT=1,258) o que proporcione materiales útiles para el estudio (M=2,63. DT=1,249); y consultar problemas generales relacionados con los estudios (matrícula, becas, alojamiento, etc.) (M=2,66. DT=1,258). Por tanto, de las respuestas se deduce que los estudiantes no perciben que haya apoyo académico de otras personas en las redes. Quizás indique que las actividades parten siempre de la propia iniciativa de los alumnos y muy rara vez por indicación del profesor. Prueba de ello es que son muy pocos los alumnos que han incluido entre sus contactos en las redes a algún profesor de la universidad. Tan sólo un 17,5%, frente a un 82,5% que no lo ha hecho. Y, aún son menos los que siguen a algún profesor en Twitter, solamente un 8%.

Los datos de la encuesta indicaron que un porcentaje importante de estudiantes (42,6%) ha incluido entre sus contactos al perfil institucional de la Universidad de Málaga, lo que indica interés por sus estudios. No obstante, para profundizar en las expectativas sobre el uso didáctico de las redes, planteamos a los estudiantes la posibilidad de crear grupos de las asignaturas en alguna red social. Los resultados llaman claramente la atención, sobre todo, porque más de la mitad la valora positivamente. Generalmente, los que se muestran en contra o indiferentes extienden esa actitud (como pudimos ver en el análisis cualitativo) al uso de las TIC en general. Son los conocidos como alumnos pesimistas o anti-TIC (Gutiérrez, Palacios & Torrego, 2010) (tabla 5). Ante la posibilidad de usar una red social en sustitución del campus virtual de la universidad, los porcentajes están bastante igualados, aunque despunta visiblemente, el de aquellos que lo consideran positivo (39,8%). Por su parte, un 20,4% lo considera negativo; un 27,9%, ni positivo ni negativo, y un 11,9% no sabe qué decir.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

A la luz de los datos obtenidos, nos encontramos con una paradoja. Por un lado, los estudiantes universitarios hacen un uso intensivo de las redes sociales, que forman parte de su vida y de sus tareas cotidianas –están prácticamente «conectados» durante todo el día–. Por otro, la aplicación y la utilización académica que hacen de las redes son escasas, ya que la frecuencia de realización de todas las actividades curriculares planteadas en el cuestionario fue baja de acuerdo a sus puntuaciones. Además, la gran mayoría de los alumnos no tenía entre sus contactos de las redes a ningún profesor, ni los seguían en Twitter. Y el apoyo docente percibido en las redes fue más bien escaso.

Probablemente, el limitado aprovechamiento didáctico de las redes por parte de los estudiantes está causado, sobre todo, porque tanto el profesorado como las instituciones no les otorgan apenas importancia. En nuestra investigación se ha puesto de manifiesto que el uso de las redes para actividades académicas casi siempre partía de la iniciativa de los alumnos y casi nunca por iniciativa del profesor, tal y como pudimos contrastar en los grupos de discusión. Entre los motivos que podrían justificar esta situación, podemos recurrir a Gutiérrez, Palacio y Torrego (2010), que señalan que la innovación educativa se produce a un ritmo menor al que evoluciona la sociedad y, por lo tanto, más lento que el ritmo de la innovación tecnológica. Así, las posibilidades de comunicación interpersonal y de colaboración que permiten las redes son escasamente aprovechadas en la educación formal, donde no se le da valor educativo a las relaciones interpersonales. En esta línea, Richmond, Rochefort y Hitch (2011) señalan el limitado impacto que tienen las redes en la enseñanza formal actual. Se deduce de esto que, en las universidades podría estar aún muy arraigada la enseñanza tradicional formal, donde la comunicación siempre es unidireccional (profesor-alumno) y donde al alumno le cuesta más participar y sentirse integrado.

El desfase generacional entre alumnos (nativos digitales) y profesores (inmigrantes digitales), hace necesario que los docentes adquieran formación y destreza en el uso y manejo de estas herramientas y se adapten a estos nuevos entornos. Los profesores deben conocer, seleccionar, crear y utilizar estrategias de intervención didáctica en el contexto de las TIC y dentro del EEES (Area, 2006; Ruzo & Rodeiro, 2006). Esto es, las planificaciones docentes no pueden ignorar el uso activo y social de las redes sociales (Duart, 2009).

En nuestro estudio, los alumnos mostraron una actitud positiva en utilizar las redes sociales con fines educativos. De hecho, entre los principales motivos de uso «por estudios» ocupa el tercer puesto; además, la mayoría de los estudiantes (59,9%) considera positivo crear grupos para las asignaturas en alguna red social; y el 39,8% sustituiría el campus virtual como plataforma educativa por las redes sociales. Estas mismas tendencias actitudinales positivas sobresalen en el mencionado estudio de Espuny, González, Lleixà y otros (2011), donde los alumnos no mostraron una actitud negativa respecto al uso didáctico de las redes sociales.

A pesar de la potencialidad de las redes sociales en el ámbito académico, no puede pasar desapercibido que «estudiar» sea la tercera actividad a la que se ha restado tiempo en beneficio de las redes sociales. Una tendencia que hay que revertir para aprovechar con fines educativos esa cantidad de tiempo que pasan en las redes. De nuevo esto nos lleva a la idea de que los docentes tienen un papel importante en el fomento del uso académico y la participación de los alumnos. Desde el aula el profesor puede motivar el interés de los estudiantes. Para ello, tiene que transmitir que se trata de una herramienta de apoyo al trabajo en el aula y que los contenidos que generen y viertan en ella forman parte de su aprendizaje. Además de fomentar la participación activa y la cohesión como grupo (Castañeda, 2010).

Llegado el momento en el que el profesor decide usar las redes sociales en su docencia, ha de elegir una de entre la amplia oferta de Internet. De acuerdo a los datos, podemos discutir qué redes comerciales son las que mejor se pueden ajustar al ámbito educativo. No sólo por su idoneidad para la práctica docente, sino por el mayor uso y dominio de las mismas por parte de los estudiantes; así como su facilidad de uso y que se trate de una web abierta cuyo perfil tecnológico sea bajo. Siguiendo este razonamiento, según los datos de nuestro estudio –similares a los de otros estudios contemporáneos (Tapia, Gómez, Herranz de la Casa & al., 2010)–, las redes idóneas serían Tuenti, Facebook y, en menor medida por su reducida penetración, Twitter. No obstante, nos decantamos por Facebook por sus mayores posibilidades en cuanto a aplicaciones (foros, chat, textos, vídeos, etcétera) y creación de contenidos (elaboración de páginas). La primera estrategia de cualquier docente podría consistir en la creación de un grupo en Facebook con el propio nombre de la asignatura, acción que estaría bien vista por casi los dos tercios del alumnado, según los datos de la encuesta .

Aun conociendo que los usos didácticos o educativos de las redes sociales no son los que concitan la mayor atención de los universitarios encuestados, sí se han podido destacar varias actividades didácticas, que se llevan a cabo en estas redes: resolución de dudas, mantenerse informado sobre las clases, realización de trabajos en grupo y compartir información. Es decir, cuestiones todas ellas que se pueden resumir en una idea principal: creación e intercambio de conocimiento. Estas actividades se desarrollan siempre entre compañeros, entre el grupo de iguales. Nacen «motu proprio» y de una manera informal y espontánea. Por tanto, los docentes podrían afianzarlas además de ofrecer a los estudiantes nuevas ópticas y fórmulas para sacar partido académico a las redes.

De acuerdo a las manifestaciones de los participantes en los grupos de discusión, utilizar las redes sociales para estas tareas no les supone un esfuerzo adicional, sino que muy al contrario descubren en ellas múltiples ventajas a la hora de compartir información, realizar trabajos, interactuar entre ellos y con los profesores. Estas actitudes coinciden con los resultados de otros estudios (Espuny, González, Lleixà & al., 2011), donde los estudiantes consideraban a las redes sociales especialmente rentables desde el punto de vista educativo.

Las actividades de tipo académico que presentaron una frecuencia de utilización mayor en la muestra están directamente relacionadas con las nuevas metodologías activas y participativas por las que aboga el EEES, es decir, con el intercambio y el desarrollo de conocimiento entre grupos reducidos de iguales. La introducción de estas actividades «bien llevadas» en las aulas podría suponer un cambio en la cultura educativa; romper con la limitación del espacio y el tiempo; agilizar el trabajo colaborativo; fomentar el aprendizaje continuo; aumentar la motivación del alumnado; fomentar la cooperación, la colaboración y la cohesión del grupo; fomentar el aprendizaje autónomo, la responsabilidad y la independencia; fomentar el diálogo y la comunicación entre alumnos, entre alumnos y profesores y entre alumnos y expertos; fomentar el pensamiento crítico; compartir y mejorar el conocimiento personal colectivo; reducir costes, esfuerzo y tiempo; optimizar la manera de trabajar; facilitar el intercambio de información; disponer de información actualizada y accesible; disponer de un sistema de documentación colaborativa, basado en un mecanismo de autoedición; aumentar la libertad en la organización del trabajo, y facilitar el acceso a expertos.

En conclusión, no puede descartarse un aprovechamiento académico de las redes sociales en el futuro dada la profundidad de su implantación en las rutinas diarias de los estudiantes universitarios. A pesar de que predomine el uso dirigido al entretenimiento, la actitud positiva del alumnado y las vastas posibilidades comunicativas de estos canales posibilitan también la utilización didáctica de las redes sociales, siempre y cuando, los docentes planifiquen y gestionen adecuadamente estos recursos. De esta manera, coincidimos con Castañeda (2010) en que si bien el potencial educativo de las redes sociales es enorme, el reto consistirá en despertar el interés tanto de instituciones, docentes y alumnado para integrarlas como herramientas básicas de la enseñanza.

Toda vez que se han hallado evidencias de la actitud positiva de los estudiantes y del escaso –aunque existente– uso de las redes con fines académicos, futuros estudios podrían centrar su atención en varias preguntas de investigación como las siguientes: ¿cuáles son las actitudes del profesorado ante la idea de incorporar las redes sociales a su práctica docente?, ¿qué uso están dando los profesores a las redes?, ¿qué tipo de actividades concretamente?, ¿con qué fines educativos?, ¿cómo las evalúan? Y, por supuesto, a nuestro juicio la más relevante: ¿implica realmente el uso de redes sociales en la docencia un aumento significativo del aprendizaje de los estudiantes?

Notas

Durante el curso académico 2011/12 se realizará una experiencia piloto en esta línea en la asignatura «Estructura general del sistema de medios» de la titulación de Periodismo, impartida en la Universidad de Málaga.

Apoyos

Este trabajo se enmarca en el Proyecto de Innovación Educativa PIE 08-045, financiado por la Universidad de Málaga.

Referencias

Alonso, H. & López, I. (2008). Adaptando asignaturas al EEES: el caso de Teoría y Técnica de la Publicidad. In Rodríguez, I. (Ed.). El nuevo perfil del profesor universitario en el EEES. Claves para la renovación metodoló-gica. Valladolid: Universidad Europea Miguel de Cervantes.

Alonso, M.H. & Muñoz de Luna, A.B. (2010). Uso de las nuevas tecnologías en la docencia de Publicidad y Relaciones Públicas, en Sierra, J. & Sotelo, J. (Coords.). Métodos de innovación docente aplicados a los estudios de Ciencias de la Comunicación. Madrid: Fragua; 348-358.

Area, M. (2006). La enseñanza universitaria en tiempo de cambio: El papel de las bibliotecas en la innovación educativa. IV Jornadas CRAI. Red de Bibliotecas Universitarias (REBIUN). Burgos: Universidad de Burgos, 10-12 mayo 2006.

Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación (AIMC). (2011) Navegantes en la Red. Encuesta AIMC a usuarios de Internet. Octubre-diciembre 2010. AIMC (http://download.aimc.es/aimc/navred2010/ma-cro2010_cuest.pdf) (10-03-2011).

Caballar, J.A. (2011). Cuestionario sobre redes sociales online. Grupo de Investigación SEJ494. E-Business. Em-presa, Administración y Ciudadano (http://edoctorado.es) (07-03-2011).

Castañeda, L. (2010). Aprendizaje con redes sociales. Tejidos educativos para los nuevos entornos. Sevilla: MAD.

De Haro, J.J. (2010). Redes Sociales para la educación. Madrid: Anaya.

De la Torre, A. (2009). Nuevos perfiles en el alumnado: la creatividad en nativos digitales competentes y expertos rutinarios. Revista Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento, 6, 1; 9.

Duart, J.M. (2009). Internet, redes sociales y educación. Revista Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento, 6, 1; 1-2.

Ellison, N.B.; Steinfield, C. & Lampe, C. (2007). The Benefits of Facebook Friends: Social Capital and College Students Use of Online Social Network Sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12; 1143-1168.

Espuny, C.; González, J. & al. (2011). Actitudes y expectativas del uso educativo de las redes sociales en los alumnos universitarios. Revista de Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento (RUSC), 8, 1; 171-185.

Flores, J.M. (2009). Nuevos modelos de comunicación, perfiles y tendencias en las redes sociales. Comunicar, 33; 73-81.

Gutiérrez, A.; Palacios, A. & Torrego, L. (2010). Tribus digitales en las aulas universitarias. Comunicar, 34; 173-181.

Imbernón, F.; Silva, P. & Guzmán, C. (2011). Competencias en los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje virtual y semipresencial. Comunicar, 36; 107-114.

Ledbetter, A.M.; Mazer, J.P. & otros (2010). Attitudes Toward Online Social Connection and Self-Disclosure as Predictors of Facebook Communication and Relational Closeness. Communication Research, 38, 1; 27-53.

Monge, S. & Olabarri, M.E. (2011). Los alumnos de la UPV/EHU frente a Tuenti y Facebook: usos y percep-ciones. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 66; 79-100 (www.revistalatinacs.org/11/art/925_UPV/04_-Monge.html) (01-03-2011).

Richmond, N.; Rochefort, B. & Hitch, L.P. (2011). Using Social Networking Sites During the Career Management Process, en Wankel, L.A & Wankel, C. (Eds.). Higher Education Administration with Social Media : Including Applications in Student Affairs, Enrolment Management, Alumni Affairs, and Career Centers. Bingley (UK): Emerald.

Ruzo, S. & Rodeiro, D. (2006). Enseñanza-aprendizaje, en Uceda, J. & Senén, B. (Coords.). Las TIC en el sistema universitario español 2006: un análisis estratégico. Madrid: CRUE.

Servicio central de informática (2010). Estadísticas de alumnos. Grado 1º y 2º ciclo. Curso 2009-2010. Málaga: Universidad de Málaga.

Tapia, A.; Gómez, B. & al. (2010). Los estudiantes universitarios ante las redes sociales: cuestiones de uso y agrupación en estructuras elitistas o pluralistas. Vivat Academia, 113 (www.ucm.es/info/vivataca/numeros/n-113/DATOSS.htm) (25-02-2011).

Valenzuela, S.; Park, N. & Kee, K.F. (2009). Is There Social Capital in a Social Network Site?: Facebook Use and College Students Life Satisfaction, Trust and Participation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14; 875-901.

Document information

Published on 29/02/12

Accepted on 29/02/12

Submitted on 29/02/12

Volume 20, Issue 1, 2012

DOI: 10.3916/C38-2012-03-04

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?