Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Resumen

Bullying and cyberbullying have negative consequences on adolescents’ mental health. The study had two objectives: 1) to analyze possible differences in sexual orientation (heterosexual and non-heterosexual) in the percentage of victims and aggressors of bullying/cyberbullying, as well as the amount of aggressive behavior suffered and carried out; 2) to compare the mental health of adolescent heterosexual and non-heterosexual victims, aggressors, cybervictims, and cyberaggressors. Participants included 1,748 adolescents from the Basque Country, aged between 13 and 17 years (52.6% girls, 47.4% boys), 12.5% non-heterosexuals, 87.5% heterosexuals, who completed 4 assessment instruments. A descriptive and comparative cross-sectional methodology was used. The results confirm that: 1) the percentage of victims and cybervictims was significantly higher in non-heterosexuals, but the percentage of heterosexual and non-heterosexual aggressors and cyberaggressors was similar; 2) non-heterosexual victims and cybervictims had suffered significantly more aggressive bullying/cyberbullying; 3) non-heterosexual victims and aggressors of bullying exhibited significantly more depression, social anxiety, and psychopathological symptoms (somatization, obsession-compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity…) than heterosexuals; 4) non-heterosexual cybervictims and cyberaggressors displayed more depression and more psychopathological symptoms, but no differences were found in social anxiety. The importance of intervening from the family, school, and society to reduce bullying/cyberbullying and enhance respect for sexual diversity is discussed.

Resumen

Acoso y ciberacoso tienen consecuencias muy negativas en la salud mental de los adolescentes. El estudio tuvo dos objetivos: 1) analizar si existen diferencias en función de la orientación sexual (heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales) en el porcentaje de víctimas y agresores de acoso y ciberacoso, así como en la cantidad de conducta agresiva sufrida-realizada; 2) comparar la salud mental de adolescentes heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales que han sido víctimas, agresores, cibervíctimas y ciberagresores. Participaron 1.748 adolescentes del País Vasco, entre 13 y 17 años (52,6% chicas, 47,4% chicos), 12,5% no-heterosexuales, 87,5% heterosexuales, que cumplimentaron 4 instrumentos de evaluación. Se utilizó una metodología descriptiva y comparativa transversal. Los resultados confirman que: 1) el porcentaje de víctimas y cibervíctimas fue significativamente mayor en el grupo no-heterosexual, sin embargo, el porcentaje de agresores y ciberagresores heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales fue similar; 2) víctimas y cibervíctimas no-heterosexuales habían sufrido significativamente más cantidad de conductas agresivas de acoso/ciberacoso; 3) víctimas y agresores de acoso no-heterosexuales comparados con heterosexuales tenían significativamente más depresión, ansiedad social y síntomas psicopatológicos diversos (somatización, obsesión-compulsión, sensibilidad interpersonal…); 4) cibervíctimas y ciberagresores no-heterosexuales también presentaban más depresión y más síntomas psicopatológicos diversos, sin embargo, en ansiedad social no se hallaron diferencias. El debate se centra en la importancia de intervenir desde la familia, la escuela y la sociedad, para reducir el acoso/ciberacoso y estimular el respeto por la diversidad sexual.

Keywords

Bullying, cyberbullying, LGBT-phobia, sexual orientation, prevalence, mental health, homophobia, school violence

Palabras clave

Acoso, ciberacoso, LGTB-fobia, orientación sexual, prevalencia, salud mental, homofobia, violencia escolar

Introduction

In recent years, bullying and cyberbullying have aroused considerable social concern and interest in the scientific community. Bullying refers to the existence of a defenseless victim, harassed by one or more aggressors, with power inequality, who frequently engage in aggressive behavior towards the victim (physical, verbal, social exclusion...) with the intention of causing harm.

Cyberbullying is a new type of bullying, which uses information and communication technologies, the Internet (email, messaging, chats, the web, games...) and mobile phones to bully classmates. A review of national and international epidemiological studies has identified a relevant prevalence of bullying and cyberbullying (2-12% victims; 1-10% cybervictims) (Garaigordobil, 2018), along the same lines as the recent study by Save the Children (2016) with adolescent Spaniards (9.3% victims; 6.9% cybervictims). The impact of these behaviors can be devastating. People with a non-normative sexual orientation and identity are a vulnerable population (Poteat & Espelage, 2005), and suffer bullying/cyberbullying and aggressive LGBT-phobic behaviors more frequently. LGBT-phobic bullying refers to bullying motivated by a phobia toward the LGBT population, and homophobia/LGBT-phobia is defined as a hostile attitude of aversion… that considers that a non-normative sexual orientation (homosexual, bisexual, transsexual...) is inferior, pathological…, and that LGBT individuals are sick, unbalanced, delinquents… The study is contextualized within a theoretical framework that considers behavior to be influenced by the social norms prevailing in the socio-cultural environment, and that stereotypes/prejudices fostered by a hetero-normative society stigmatize LGBT individuals, justifying and promoting their bullying, impacting their mental health negatively.

In line with the theory of social identity, in order to maintain a positive social identity, individuals tend to overrate their group, attributing positive characteristics to it, to the detriment of the outgroup, whose stereotype is negative. This categorization and contempt encourage and justify aggressive behaviors toward the other group. Studies show an increase of homophobic insults with age (Espelage & al., 2017), identifying the school context as the main area for their use (Generelo & al., 2012), and the classmates, especially males, playing an important role in the formulation of these insults (Birkett & Espelage, 2015). Given the relevant role of the educational context, it is necessary to assess adolescent attitudes towards sexual diversity and, if necessary, to intervene and reinforce respect and tolerance.

Prevalence of bullying and cyberbullying in LGBT individuals

In relation to bullying, some research has revealed data ranging from 51% to 58% of victimization in people with non-normative sexual orientation/identity (Generelo, Garchitorena, Montero, & Hidalgo, 2012; Martxueta & Etxeberria, 2014). In cyberbullying, cybervictimization rates between 10% and 71% have been reported in LGBTs (Abreu & Kenny, 2017; COGAM, 2016; Cooper & Blumenfeld, 2012; Kosciw, Greytak, Giga, Villenas, & Danischewski, 2016). The discrepancies between studies are due to the different ages of the samples and the different behaviors measured.

Studies that have focused on comparing victimization levels as a function of sexual orientation suggest that non-heterosexuals suffer a greater amount of bullying compared to heterosexuals (Abreu & Kenny, 2017; Baiocco, Pistella, Salvati, Loverno, & Lucidi, 2018; Bouris, Everett, Heath, Elsaesser, & Neilands, 2016; Camodeca, Baiocco, & Posa, 2018; Collier, Bos, & Sandfort, 2013; COGAM, 2016; Elipe, De-la-Oliva-Muñoz, & Del-Rey, 2017; Gegenfurtne & Gebhardt, 2017; Toomey & Russel, 2016). Research analyzing the aggressor role from a sexual diversity perspective has focused on the prevalence of aggressors' LGBT-phobic behavior, but it has not compared bullying/cyberbullying perpetration among heterosexuals and non-heterosexuals.

Bullying/cyberbullying in LGBTs and mental health

Some research has shown that LGBTs who have been victims of bullying and cyberbullying at school show depression and anxiety (Ferlatte, Dulai, Hottes, Trussler, & Marchand, 2015; Martxueta & Etxeberria, 2014; Wang & al., 2018), psychological distress (Birkett, Newcomb, & Mutanski, 2015), and risk of suicide (Cooper & Blumenfeld, 2012; Duong & Bradshaw, 2014; Ferlatte & al., 2015; Luong, Rew, & Banner, 2018; Quintanilla, Sánchez-Loyo, Correa-Márquez, & Luna-Flores, 2015; Ybarra, Mitchell, Kosciw, & Korchmaros, 2014). Few studies compare heterosexual and non-heterosexual cybervictims and cyber-aggressors in different mental health variables, to explore whether the cyber-victimization of LGBTs is associated with further deterioration of their mental health, compared to health of heterosexual cybervictims and cyber-aggressors.

The studies of Ybarra and others (2014) are worth mentioning. They showed that the relationship between suicidal ideation and bullying was stronger in gays, lesbians and queers, compared to bisexuals, heterosexuals, and those who were uncertain of their sexual orientation. Hence, there is hardly any research that focuses on this differentiation with other mental health variables.

Studies that have focused on comparing victimization levels as a function of sexual orientation suggest that non-heterosexuals suffer a greater amount of bullying compared to heterosexuals.

Objectives and hypotheses

The study had two objectives: 1) to analyze possible differences as a function of sexual orientation (heterosexual and non-heterosexual) in the percentage of victims and aggressors of bullying and cyberbullying (victims, aggressors, cybervictims, cyberaggressors) and in the amount of aggressive behavior suffered and performed in both groups; 2) to compare the mental health (depression, social anxiety, interpersonal sensitivity, somatization, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation...) of heterosexuals and non-heterosexuals who have been victims, aggressors, cybervictims and cyberaggressors. These objectives are formulated in three hypotheses:

- H1. The percentage of victims and cybervictims will be significantly higher in the group of non-heterosexual adolescents, compared to the percentage of victims and cybervictims of the heterosexual group, whereas there will be no differences in the percentage of heterosexual and non-heterosexual aggressors and cyberaggressors.

- H2. The amount of behavior suffered by victims and cybervictims will be significantly higher in the group of non-heterosexuals, compared to the amount suffered by heterosexual victims and cybervictims; however, no differences will be found between the two conditions in the amount of aggressive bullying and cyberbullying behavior performed.

- H3. Compared to heterosexuals, non-heterosexual victims, cybervictims, aggressors, and cyberaggressors will have significantly poorer mental health, which will manifest in more symptoms of depression, social anxiety, increased general psychopathology, and a larger amount of diverse psychopathological symptoms (somatization, obsession-compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism).

Material and methods

Participants

The study sample is made up 1,748 adolescents aged13 to 17 years (52.6% girls, 47.4% boys) from 19 schools. Concerning educational level, 60.2% are in 3rd grade of Secondary Education and 39.8% are studying 4th grade (44.7% in public schools and 55.3% in private schools). Regarding sexual orientation, 87.5% are heterosexual, 0.7% are gay, 0.2% are lesbian, 5.7% are bisexual, and 5.9% are unsure of their sexual orientation; that is, 12.5% are non-heterosexual and 87.5% are heterosexual. The sample was selected randomly and is representative of the students of the last cycle of Secondary Education of the Basque Country (N=37.575). Using a confidence level of 0.95, with a sample error of 2.3%, the representative sample is 1,732. A stratified sampling technique was used to select the sample, taking into account the following parameters: province, type of school (public-private), and educational level (3rd and 4th grades).

Instruments

To measure the variables under study, in addition to a sociodemographic questionnaire requesting information on sexual orientation, four evaluation tools with psychometric guarantees were used.

- Cyberbullying. Screening of Peer Harassment (Garaigordobil, 2013; 2017). This assesses bullying and cyberbullying. The bullying scale measures four types of bullying (physical, verbal, social, and psychological), and the cyberbullying scale explores 15 behaviors related to cyberbullying (sending offensive/threatening messages, phoning to insult/threaten, recording an aggression/humiliation and uploading the video, creating rumors to slander, stealing a password, isolating on social networks...). Adolescents report how often they have suffered and performed these behaviors over the course of their lives. Four scores are provided: level of victimization, cybervictimization, aggression, and cyberaggression. The Cronbach alpha coefficients with the original sample show adequate internal consistency (bullying α=.81; cyberbullying α=.91), as in the sample of this study (bullying α=.76; cyberbullying α=.84).

- Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck & al.,1996; adaptation of Sanz, García-Vera, Espinosa, Fortún, & Vázquez, 2005). It is composed of 21 items that measure the severity of depression. The items measure symptoms of depression: sadness, pessimism, feelings of failure, loss of pleasure, feeling guilty, feelings of punishment, self-dissatisfaction, self-criticism, thoughts of suicide, crying, agitation, loss of interest, indecision, futility, loss of energy, changes in sleep pattern, irritability, changes in appetite, difficulty concentrating, tiredness or fatigue, and loss of interest in sex. The adolescent reports the degree to which he or she has had these symptoms over the past two weeks. The alpha coefficients with the original sample were adequate (α=.87), as in sample of this study (α=.84).

- Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A; La-Greca & Stone, 1993; Spanish adaptation Olivares & al., 2005). It is made up of 22 items that evaluate global social anxiety (social phobia) and 3 sub-dimensions: fear of negative evaluation, social avoidance and distress in the face of unknown situations and strangers, and stress in the company of acquaintances. Adolescents report how often (never-always) they have such thoughts, feelings, behaviors... The internal consistency of the test in the original sample was high (α=.91), as in the sample in this study (α=.87).

- 90-Symptom Checklist-Revised (SCL-90-R; Derogatis, 2002). This contains 90 items on nine scales that report psychopathological alterations: somatization (experiences of body dysfunction, neurovegetative alterations of the cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal and muscular systems), obsession-compulsion (absurd and unwanted behaviors, thoughts... that generate intense distress and are difficult to resist, avoid, or eliminate), interpersonal sensitivity (timidity and embarrassment, discomfort and inhibition in interpersonal relationships), depression (anhedonia, hopelessness, helplessness, lack of energy, self-destructive ideas...), anxiety (generalized and acute anxiety/panic), hostility (aggressive thoughts, feelings and behaviors, anger, irritability, rage, and resentment), phobic anxiety (agoraphobia and social phobia), paranoid ideation (paranoid behavior, suspicion, delirious ideation, hostility, grandiosity, need for control...), and psychoticism (feelings of social alienation). A total score is obtained from the summary of the scales of the SCL-90-R (general degree of psychopathology). Studies with Spanish samples suggest good reliability (α=.81 to .90), as in this study (α=.97).

Procedure

This study uses a descriptive and comparative cross-sectional methodology. Firstly, a letter was sent to the headmasters of the randomly selected schools, explaining the research project. Those who agreed to participate received informed consents for parents and participants. Subsequently, the evaluation team visited the schools and administered the assessment tools to the students (in one 50-minute session). The study fulfilled the ethical values required in human research, having been favorably evaluated by the Ethics Commission of the UPV/EHU (M10_2017_094).

Data analysis

To determine the prevalence of heterosexual and non-heterosexual victims, cybervictims, aggressors, and cyberbullies, the frequencies/percentages of students who had suffered and engaged in bullying/cyberbullying frequently (fairly often + always) were calculated and, through contingency analysis, the Pearson Chi square was obtained to compare the two conditions. Second, to identify possible differences as a function of sexual orientation in the four indicators of bullying/cyberbullying (victimization, cybervictimization, aggression, cyberaggression), descriptive analysis (means and standard deviations), analysis of univariate variance, and effect size analysis (Cohen’s d: small<.50; moderate .50-79; large ≥.80) were performed with the scores of the heterosexuals and non-heterosexuals. Finally, to explore possible differences according to sexual orientation (heterosexuals and non-heterosexuals) in various psychopathological symptoms (mental health), first, we selected the sample of bullying victims (who had reported having suffered aggressive bullying during their lifetime), and we performed an analysis of variance (MANOVA, ANOVA) as a function of heterosexual and non-heterosexual group membership. The same procedure was performed with cybervictims, aggressors, and cyberaggressors, respectively. Data analysis was performed with the SPSS 24.0 program.

Results

Prevalence of heterosexual and non-heterosexual victims and cybervictims

The percentages of heterosexual and non-heterosexual students who had frequently (fairly often + always) suffered bullying and cyberbullying were: 1) severe victims: 11% (n=193) of the victims had suffered bullying frequently over the course of their lives. The percentage of severe heterosexual and non-heterosexual victims of the sample in each sexual orientation group was 9% heterosexuals (n=138) and 25.1% non-heterosexuals (n=55). The percentage of victims was significantly higher in the non-heterosexual group (X²=50.48, p<.001); 2) severe cybervictims: 7.2% (n=126) of the victims had frequently suffered cyberbullying. The percentage of severe heterosexual and non-heterosexual cybervictims of the sample in each sexual orientation group was 6.2% heterosexuals (n=95) and 13.7% non-heterosexuals (n=30). The percentage of cybervictims was significantly higher in the non-heterosexual group (X²=16.16, p<.001). Thus, the percentage of victims and cybervictims was significantly higher in the non-heterosexual group, compared to the percentage of victims and cybervictims of the heterosexual group.

Prevalence of heterosexual and non-heterosexual aggressors and cyberaggressors

The percentages of heterosexual and non-heterosexual students who had frequently performed (fairly often + always) bullying and cyberbullying were: 1) severe aggressors: 2.7% (n=47) had frequently performed bullying behaviors. The percentage of severe heterosexual and non-heterosexual aggressors in the sample of each sexual orientation group was 1.7% heterosexuals (n=38) and 0.9% non-heterosexuals (n=9). No significant differences were found as a function of sexual orientation (X²=0.75, p>.05); 2) severe cyberaggressors: 1.6% (n=28) had frequently engaged in cyberbullying behaviors. The percentage of severe heterosexual and non-heterosexual cyberaggressors of the sample in each sexual orientation was 1.7% heterosexuals (n=26) and 0.9% non-heterosexuals (n=2). No significant differences were found (X²=0.75, p>.05). Thus, the percentage of adolescent heterosexual and non-heterosexual aggressors and cyberaggressors was similar.

Victimization, cybervictimization, aggression, and cyberaggression levels

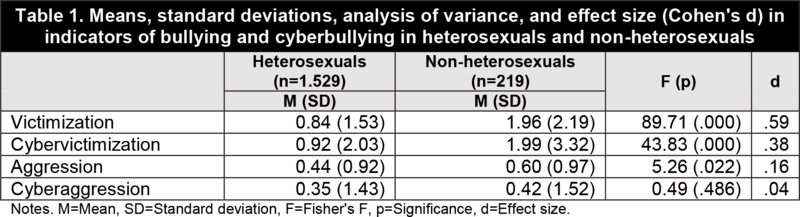

Concerning differences in the level of victimization and cybervictimization as a function of sexual orientation, the results (Table 1) show that, compared to heterosexuals, non-heterosexual victims/cybervictims had suffered a significantly greater amount of aggressive bullying and cyberbullying (moderate effect size in victimization). In relation to the level of aggression and cyberaggression (Table 1), the results show that the amount of face-to-face aggressive behavior performed was significantly higher in the non-heterosexual group, but the amount of cyberbullying behavior performed was similar in the two groups.

|

|

In short, non-heterosexual victims and cybervictims had suffered significantly more aggressive bullying and cyberbullying behaviors during their lifetime. Non-heterosexual aggressors had performed a significantly greater amount of aggressive face-to-face behaviors, although no differences were found in the amount of behavior performed by cyberaggressors in the two conditions.

|

|

Victimization and cybervictimization in the mental health of adolescent LGBTs

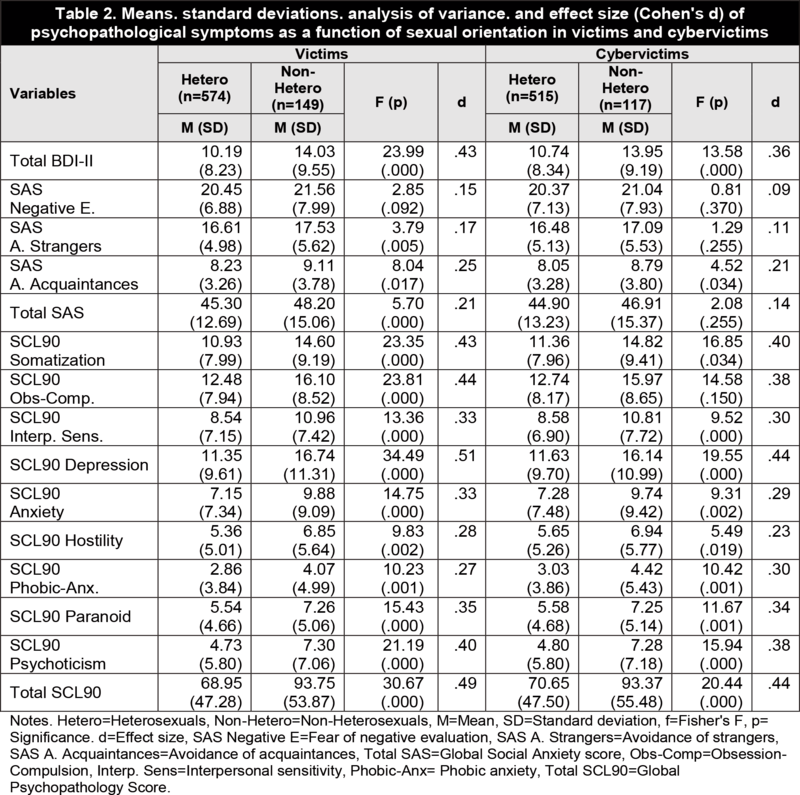

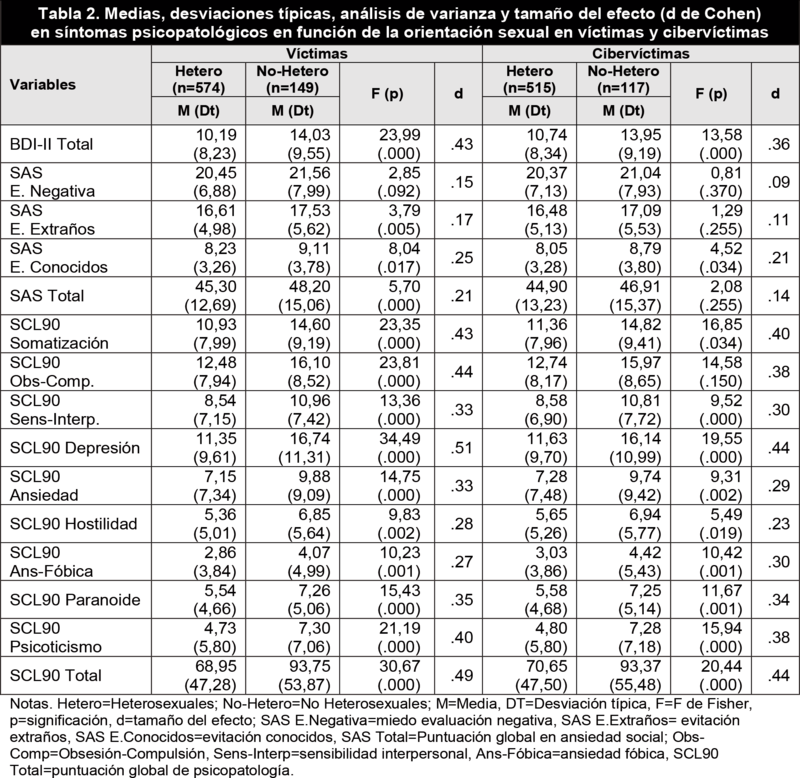

Regarding differences in psychopathological symptoms between victims and cybervictims as a function of sexual orientation (heterosexuals, non-heterosexuals), the multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) performed with all the mental health variables revealed significant differences between heterosexual and non-heterosexual bullying victims, Wilks' Lambda, Λ=0.942, F(13,708)=3.36, p<.001 (small effect size, η2=0.058, r=0.24). The same results were found in cybervictims, Wilks' Lambda, Λ=0.953, F(13,618)=2.34, p<.05 (small effect size, η2=0.047, r=0.22). The results of the descriptive, univariate and effect size analyses of each variable are presented in Table 2. Non-heterosexual victims and cybervictims presented significantly more psychopathology than heterosexual victims/cybervictims (moderately low and low effect size).

|

|

The analyses of variance (Table 2) confirmed that non-heterosexual victims (compared to heterosexual victims) showed significantly higher scores in depression (BDI-II), global social anxiety (SAS) (avoidance and social distress with acquaintances and strangers), in all the psychopathological symptoms of the SCL-90 (somatization, obsession-compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism), as well as in the global psychopathology score. Non-heterosexual cybervictims (compared to heterosexuals) (Table 2) obtained significantly higher scores in depression (BDI-II) and in all the psychopathological symptoms evaluated with the SCL-90 except for obsession-compulsion. However, non-heterosexual cybervictims had a similar level of global social anxiety (social phobia) to the heterosexual cybervictims, although their anxiety in the presence of acquaintances was higher.

Differential mental health of adolescent LGBT aggressors and cyberaggressors

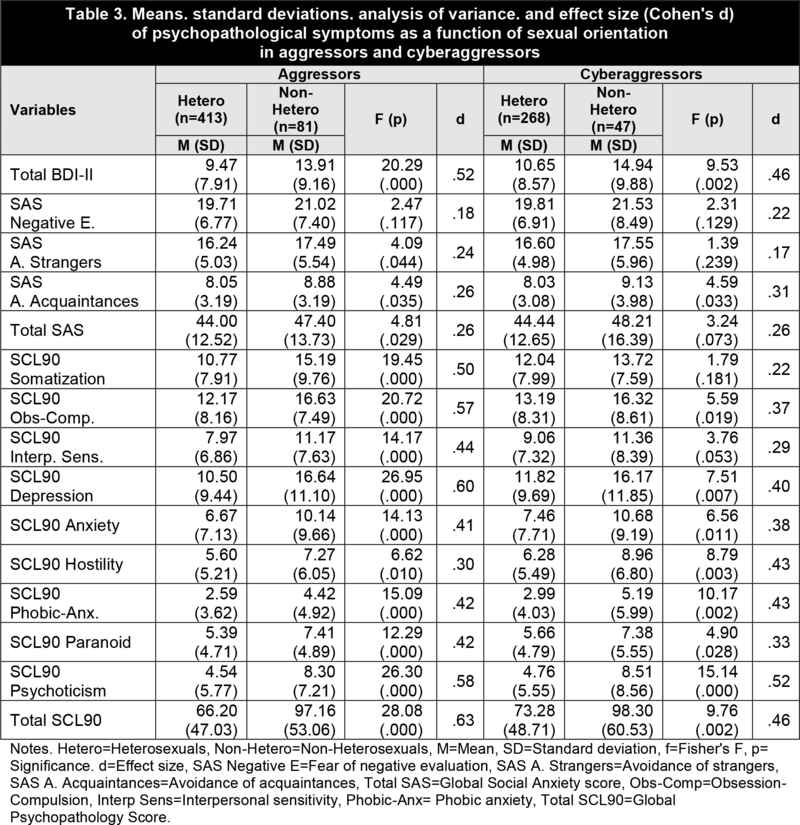

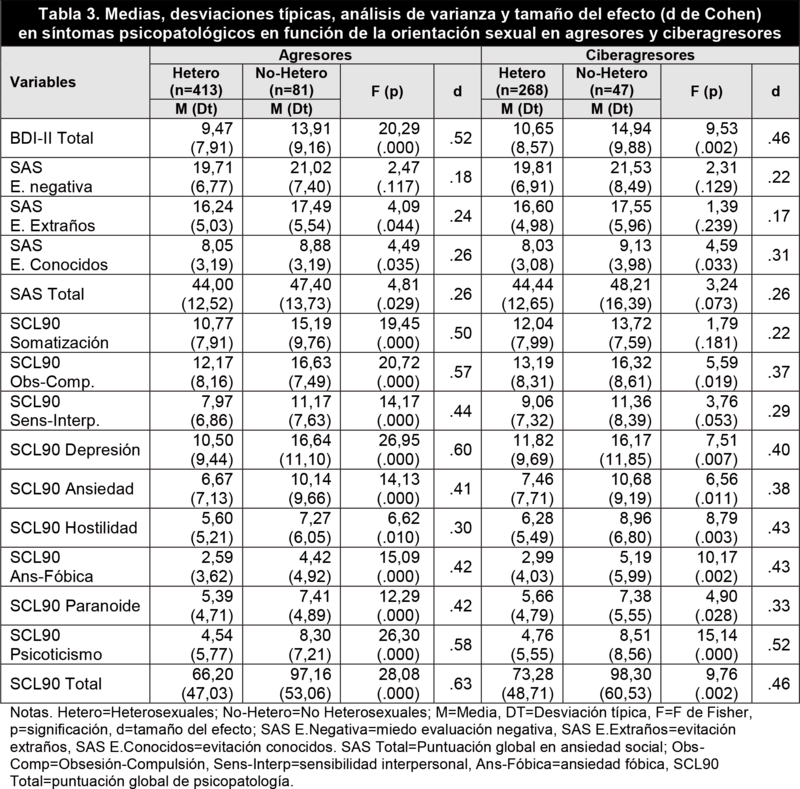

Regarding the differences in psychopathological symptoms between aggressors and cyberaggressors as a function of sexual orientation (heterosexuals, non-heterosexuals), the multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) with all the mental health variables yielded significant differences between heterosexual and non-heterosexual aggressors, Wilks' Lambda, Λ=0.923, F(10,479)=3.07, p<.001 (small effect size, η2=0.07, r=0.27). The same results were found in cyberaggressors, Wilks' Lambda, Λ=0.923, F(13,300)=1.92, p<.05 (small effect size, η2=0.077, r=0.28).

Consequently, non-heterosexual aggressors and cyberaggressors generally present significantly more psychopathology than heterosexual aggressors and cyberaggressors. The results of the descriptive, univariate, and effect size analyses in each variable under study are presented in Table 3.

As can be seen (Table 3), non-heterosexual aggressors (compared to heterosexuals) had significantly more depression (BDI-II), more social anxiety (SAS), more psychopathological symptoms evaluated with the SCL-90 (somatization, obsession-compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism), and a higher global psychopathology score. Non-heterosexual cyberaggressors had significantly more depression (BDI-II) and more psychopathological symptoms (obsession-compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism), except for symptoms of somatization. No differences were found in global social anxiety between heterosexual and non-heterosexual cyberaggressors (moderate effect size in depression and global psychopathology score).

Discussion and conclusions

The objective of the study was to analyze possible differences as a function of sexual orientation (heterosexuals and non-heterosexuals) in the percentage of victims and aggressors of bullying and cyberbullying, and in the amount of aggressive behavior they suffer and perform it also compares the mental health of heterosexuals and non-heterosexuals who have been victims, aggressors, cybervictims, and cyber-aggressors.

Firstly, the results confirm that the percentage of victims and cybervictims was significantly higher in non-heterosexual adolescents, compared to the percentage of heterosexual victims and cybervictims. However, the percentage of heterosexual and non-heterosexual aggressors and cyberaggressors was similar. Hypothesis one is confirmed. In addition, the overall prevalence of bullying and cyberbullying found in this study (11% victims; 7.2% cybervictims) confirms the prevalence found in recent epidemiological reviews and studies (Garaigordobil, 2018; Save the Children, 2016).

Secondly, the results show that non-heterosexual victims/cybervictims, compared to heterosexual victims/cybervictims, had suffered a greater amount of aggressive bullying and cyberbullying. Non-heterosexual aggressors had engaged in significantly more bullying behaviors, although no differences were found in cyberaggressors. Hypothesis two is partially confirmed, as non-heterosexual aggressors were also found to engage in a greater amount of aggressive bullying than heterosexuals.

The high vulnerability of people who do not match the stereotypes based on hetero-normativity is confirmed. The results point in the same direction as other studies that have shown that the LGBT collective is more vulnerable to bullying and cyberbullying (Abreu & Kenny, 2017; Baiocco & al., 2018; Birkett & al., 2009; Bouris & al., 2016; Camodeca & al., 2018; Collier & al., 2013; COGAM, 2016; Elipe & al., 2017; Gegenfurtne & Gebhardt, 2017; Pichardo & al., 2002; Shields & al., 2012; Toomey & Russel, 2016). As there are no studies comparing the prevalence of aggressors/cyberaggressors between heterosexuals and non-heterosexuals, the results of this study contribute to the knowledge.

Third, the results show that non-heterosexual victims and aggressors (compared to heterosexual victims and aggressors) have significantly more depression, social anxiety, and more psychopathological symptoms in all the scales (somatization, obsession-compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism). Non-heterosexual cybervictims and cyberaggressors (compared to heterosexuals) present significantly more depression and more psychopathological symptoms (interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism). No differences were found in global social anxiety between heterosexual and non-heterosexual cybervictims and cyberaggressors. Hypothesis three is almost entirely confirmed, as greater social anxiety was not found in non-heterosexual cybervictims and cyberaggressors.

Therefore: 1) non-heterosexual victims and aggressors (versus heterosexuals) show more symptoms in all the evaluated psychopathological disorders (somatization, obsession-compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism, social anxiety); 2) non-heterosexual cybervictims and cyberaggressors (versus heterosexuals) have more psychopathological symptoms (interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism), although they do not have more social anxiety; in addition, non-heterosexual cybervictims do not have more symptoms of obsession-compulsion, nor do cyberaggressors show more somatization; 3) non-heterosexual victims have greater anxiety/social phobia than non-heterosexual cybervictims.

Although there are no prior studies comparing diverse psychopathological symptoms in heterosexuals and non-heterosexuals who have suffered and/or performed bullying/cyberbullying—which is a contribution of this work—the results obtained confirm those found in research that has revealed psychopathological symptoms in victims with a non-normative sexual orientation that also found depression and anxiety (Ferlatte & al., 2015; Martxueta & Etxeberria, 2014; Wang & al., 2018).

The study provides data on the prevalence of LGBT-phobic bullying/cyberbullying and shows that LGBTs, in addition to being bullied/cyberbullied more frequently, also develop more psychopathological symptoms due to the victimization/cybervictimization they suffer than do heterosexuals who are bullied/cyberbullied. Among the limitations of the study are: 1) the use of self-reports with the desirability bias involved; 2) although there is greater visibility of LGBTs, many people still conceal their sexuality. If this is a reality in the general population, adolescents find it even more difficult to identify themselves as non-heterosexual. Hence, in the study emerged a percentage of adolescents who are uncertain about their sexuality and who were included in the non-heterosexual group, as other researchers have done; 3) the cross-sectional nature of the study, which does not allow causal inferences. Future studies could analyze the role of victim-aggressor, expand the LGBT sample, perform analyses as a function of age and gender, and design anti-bullying programs based on stigma, evaluating their effects on the stereotypes and prejudices towards LGBTs.

Both aggressive behavior towards sexual diversity and the internalized discrimination that characterizes LGBTs can be considered as the result of a society that is educated by a hetero-normative system. Children are not born as homophobes, they are modeled since their birth through messages received from their family, school, and social environment. Therefore, it is necessary to educate in sexual orientation/identity from different contexts, so that children grow up respecting differences in general and sexual diversity in particular. The results have practical implications and suggest the need to develop specific activities during childhood and adolescence that stimulate respect and tolerance for sexual diversity and activities within anti-bullying programs that address LGBT-phobic bullying/cyberbullying due to non-hetero-normative sexual orientation/identity. Among these programs, we can mention Cyberprogram 2.0, an intervention program to prevent cyberbullying that addresses bullying due to sexual orientation (e.g,. open cyber-secrets, sexting, false promises…). The program has been evaluated experimentally, confirming a reduction in bullying and cyberbullying (Garaigordobil & Martínez-Valderrey, 2014; 2015; 2018).

Earnshaw and others (2018) observe an increase in interventions to address stigma-based bullying (against young LGBTQs, overweight or disabled youth…). Although many Spanish schools carry out anti-bullying activities, few programs contain specific strategies to reduce stereotypes and prejudices, which are needed to address stigma-based bullying. Future intervention proposals should include such strategies to address the bullying of stigmatized groups.

Finally, we underline that interventions to reduce stigmatization and bullying/cyberbullying of LGBTs should be multidirectional. Family education in tolerance for diversity plays a key role. School is a relevant context for anti-bullying activities that focus on vulnerable groups, promoting tolerance for diversity. A third axis of intervention should be society in general, as the norms and values it promotes condition behavior. It is important to spread messages of tolerance through the mass media (TV, radio, press, Internet, social networks...), as these media are privileged tools to promote empathy and tolerance towards diversity in general and sexual diversity in particular, eliminating stereotypes and prejudices. However, clinical intervention should not be forgotten because of the risk of suicide of people suffering from LGBT-phobic bullying/cyberbullying.

References

- AbreuR L, KennyM C, . 2018.and LGBTQ youth: A systematic literature review and recommendations for prevention and intervention&author=Abreu&publication_year= Cyberbullying and LGBTQ youth: A systematic literature review and recommendations for prevention and intervention.Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 11(1):81-97

- BaioccoR, PistellaJ, SalvatiM, SalvatoreI, LucidiF, . 2018.as risk environment: Homophobia and bullying in a simple of gay and heterosexual men&author=Baiocco&publication_year= Sports as risk environment: Homophobia and bullying in a simple of gay and heterosexual men.Journal of Gai & Lesbian Mental Health 22(4):385-411

- BeckA T, SteerR A, BrownG K, . 1996.Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition Manual&author=&publication_year= BDI-II. Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

- BirkettM, EspelageD L, . 2015.name-calling, peer-groups, and masculinity: The socialization of homophobic behavior in adolescents&author=Birkett&publication_year= Homophobic name-calling, peer-groups, and masculinity: The socialization of homophobic behavior in adolescents.Social Development 24(1):184-205

- BirkettM, NewcombM E, MustanskiB, . 2015.it get better? A longitudinal analysis of psychological distress and victimization in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth&author=Birkett&publication_year= Does it get better? A longitudinal analysis of psychological distress and victimization in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth.Journal of Adolescent Health 56(3):280-285

- BourisA, EverettB G, HeathR D, ElsaesserC E, NeilandsT B, . 2016.of victimization and violence on suicidal ideation and behaviors among sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents&author=Bouris&publication_year= Effects of victimization and violence on suicidal ideation and behaviors among sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents.LGBT Health 3(2):153-161

- CamodecaM, BaioccoR, PosaO, . 2018.bullying and victimization among adolescents: The role of prejudice, moral disengagement, and sexual orientation&author=Camodeca&publication_year= Homophobic bullying and victimization among adolescents: The role of prejudice, moral disengagement, and sexual orientation.European Journal of Developmental Psychology 16(5):503-521

- COGAM (Ed.). 2016.[Madrid: FELGTB, Colectivo de Lesbianas, Gays, Transexuales y Bisexuales de Madrid. Ciberbullying LGBT-fóbico. Nuevas formas de intolerancia].

- CollierK L, BosH M, SandfortT G, . 2013.name-calling among secondary school students and its implications for mental health&author=Collier&publication_year= Homophobic name-calling among secondary school students and its implications for mental health.Journal of Youth and Adolescence 42(3):363-375

- CooperR M, BlumenfeldW J, . 2012.to cyberbullying: A descriptive analysis of the frequency of and impact on LGBT and allied youth&author=Cooper&publication_year= Responses to cyberbullying: A descriptive analysis of the frequency of and impact on LGBT and allied youth.Journal of LGBT Youth 9(2):153-177

- DerogatisL R, . 2002. , ed. Cuestionario de 90 síntomas revisado&author=&publication_year= SCL-90-R. Cuestionario de 90 síntomas revisado.Madrid: TEA.

- DuongJ, BradshawC, . 2014.between bullying and engaging in aggressive and suicidal behaviors among sexual minority youth: The moderating role of connectedness&author=Duong&publication_year= Associations between bullying and engaging in aggressive and suicidal behaviors among sexual minority youth: The moderating role of connectedness.Journal of School Health 84(10):636-645

- EarnshawV A, ReisnerS L, MeninoD, PoteatV P, BogartL M, BarnesT N, SchusteM A, . 2018.bullying interventions: A systematic review&author=Earnshaw&publication_year= Stigma-based bullying interventions: A systematic review.Developmental Review 48:178-200

- ElipeP, De-La-Oliva MuñozM, Del-ReyR, . 2017.bullying and cyberbullying: Study of a silenced problem&author=Elipe&publication_year= Homophobic bullying and cyberbullying: Study of a silenced problem.Journal of Homosexuality 65(5):672-686

- EspelageD L, HongJ S, MerrinG J, DavisJ P, RoseC A, LittleT D, . 2017.longitudinal examination of homophobic name-calling in middle school: Bullying, traditional masculinity, and sexual harassment as predictors&author=Espelage&publication_year= A longitudinal examination of homophobic name-calling in middle school: Bullying, traditional masculinity, and sexual harassment as predictors.Psychology of Violence 8(1):57-66

- FerlatteO, DulaiJ, HottesT S, TrusslerT, MarchandR, . 2015.related ideation and behavior among Canadian gay and bisexual men: A syndemic analysis&author=Ferlatte&publication_year= Suicide related ideation and behavior among Canadian gay and bisexual men: A syndemic analysis.BMC Public Health 15:597

- GaraigordobilM, . 2013.Screening de acoso entre iguales. Screening del acoso escolar presencial (bullying) y tecnológico (cyberbullying)&author=&publication_year= Cyberbullying. Screening de acoso entre iguales. Screening del acoso escolar presencial (bullying) y tecnológico (cyberbullying).

- GaraigordobilM, . 2017.properties of the cyberbullying test, a screening instrument to measure cybervictimization, cyberaggression, and cyberobservation&author=Garaigordobil&publication_year= Psychometric properties of the cyberbullying test, a screening instrument to measure cybervictimization, cyberaggression, and cyberobservation.Journal of Interpersonal Violence 32(23):3556-3576

- GaraigordobilM, . 2018. , ed. y cyberbullying: Estrategias de evaluación&author=&publication_year= Bullying y cyberbullying: Estrategias de evaluación.Barcelona: Oberta UOC Publishing.

- GaraigordobilM, Martínez-ValderreyV, . 2014.2.0. Un programa de intervención para prevenir y reducir el ciberbullying&author=&publication_year= Cyberprogram 2.0. Un programa de intervención para prevenir y reducir el ciberbullying. Madrid: Pirámide.

- GaraigordobilM, Martínez-ValderreyV, . 2015.2.0: Effects of the intervention on ‘face-to-face’ bullying, cyberbullying, and empathy&author=Garaigordobil&publication_year= Cyberprogram 2.0: Effects of the intervention on ‘face-to-face’ bullying, cyberbullying, and empathy.Psicothema 27:45-51

- GaraigordobilM, Martínez-ValderreyV, . 2018.resources to prevent cyberbullying during adolescence: The cyberprogram 2.0 program and the cooperative cybereduca 2.0 videogame&author=Garaigordobil&publication_year= Technological resources to prevent cyberbullying during adolescence: The cyberprogram 2.0 program and the cooperative cybereduca 2.0 videogame.Frontiers in Psychology 9:745

- GegenfurtnerA, GebhardtM, . 2017.education including lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) issues in schools&author=Gegenfurtner&publication_year= Sexuality education including lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) issues in schools.Educational Research Review 22:215-222

- GenereloJ, GarchitorenaM, MonteroP, HidalgoP, . 2012.escolar homofóbico y riesgo de suicidio en adolescentes y jóvenes LGB&author=&publication_year= Acoso escolar homofóbico y riesgo de suicidio en adolescentes y jóvenes LGB. Madrid: FELGTB.

- KosciwJ G, GreytakE A, GigaN M, VillenasC, DanischewskiD J, . 2016.2015 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools&author=&publication_year= The 2015 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. New York: GLSEN.

- La-GrecaA M, StoneW L, . 1993.anxiety scale for children-revised: Factor structure and concurrent validity&author=La-Greca&publication_year= Social anxiety scale for children-revised: Factor structure and concurrent validity.Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 22:17-27

- LuongC T, RewL, BannerM, . 2018.in young men who have sex with men: A systematic review of the literature&author=Luong&publication_year= Suicidality in young men who have sex with men: A systematic review of the literature.Issues in Mental Health Nursing 39(1):37-45

- MartxuetaA, EtxeberriaJ, . 2014.diferencial retrospectivo de las variables de salud mental en lesbianas, gais y bisexuales (LGB) víctimas de bullying homofóbico en la escuela&author=Martxueta&publication_year= Análisis diferencial retrospectivo de las variables de salud mental en lesbianas, gais y bisexuales (LGB) víctimas de bullying homofóbico en la escuela.Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica 19(1):23-35

- OlivaresJ, RuizJ, HidalgoM D, García-LópezL J, RosaA I, PiquerasJ A, . 2005.Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A): Psychometric properties in a Spanish-speaking population.International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 5(1):85-97

- PichardoJ I, MolinueloB, RodríguezP O, MartínN, RomeroM, . 2007. , ed. ante la diversidad sexual de la población adolescente de Coslada Madrid) y San Bartolomé de Tirajana (Gran Canaria; Madrid)&author=&publication_year= Actitudes ante la diversidad sexual de la población adolescente de Coslada Madrid) y San Bartolomé de Tirajana (Gran Canaria; Madrid).Madrid: FELGTB.

- PoteatV P, EspelageD L, . 2005.the relation between bullying and homophobic verbal content: The Homophobic Content Agent Target (HCAT) Scale&author=Poteat&publication_year= Exploring the relation between bullying and homophobic verbal content: The Homophobic Content Agent Target (HCAT) Scale.Violence and Victims 20:513-528

- QuintanillaR, Sánchez-LoyoL M, Correa-MárquezP, Luna-FloresF, . 2015.de adaptación de la homosexualidad y la homofobia asociados a la conducta suicida en varones homosexuales&author=Quintanilla&publication_year= Proceso de adaptación de la homosexualidad y la homofobia asociados a la conducta suicida en varones homosexuales.Masculinities and Social Change 4(1):1-25

- SanzJ, García-VeraM P, EspinosaR, FortúnM, VázquezC, . 2005.Adaptación española del Inventario para la Depresión de Beck-II (BDI-II): 3. Propiedades psicométricas en pacientes con trastornos psicológicos.Clínica y Salud 16(2):121-142

- ShieldsJ P, WhitakerK, GlassmanJ, FranksH M, HowardK, . 2012.of victimization on risk of suicide among lesbian, gay, and bisexual high school students in San Francisco&author=Shields&publication_year= Impact of victimization on risk of suicide among lesbian, gay, and bisexual high school students in San Francisco.Journal of Adolescent Health 50(4):418-420

- Save the Children (Ed.). 2016.[Madrid: Save the Children España Bullying y ciberbullying en la infancia].

- ToomeyR B, RussellS T, . 2016.role of sexual orientation in school-based victimization: A meta-analysis&author=Toomey&publication_year= The role of sexual orientation in school-based victimization: A meta-analysis.Youth & Society 48(2):176-201

- WangC C, LinH C, ChenM H, KoN Y, ChangY P, LinI M, YenC F, . 2018.of traditional and cyber homophobic bullying in childhood on depression, anxiety, and physical pain in emerging adulthood and the moderating effects of social support among gay and bisexual men in Taiwan&author=Wang&publication_year= Effects of traditional and cyber homophobic bullying in childhood on depression, anxiety, and physical pain in emerging adulthood and the moderating effects of social support among gay and bisexual men in Taiwan.Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 14:1309-1317

- YbarraM L, MitchellK J, KosciwJ G, KorchmarosJ D, . 2014.linkages between bullying and suicidal ideation in a national sample of LGB and heterosexual youth in the United States&author=Ybarra&publication_year= Understanding linkages between bullying and suicidal ideation in a national sample of LGB and heterosexual youth in the United States.Prevention Science 16(3):451-462

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Acoso y ciberacoso tienen consecuencias muy negativas en la salud mental de los adolescentes. El estudio tuvo dos objetivos: 1) analizar si existen diferencias en función de la orientación sexual (heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales) en el porcentaje de víctimas y agresores de acoso y ciberacoso, así como en la cantidad de conducta agresiva sufrida-realizada; 2) comparar la salud mental de adolescentes heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales que han sido víctimas, agresores, cibervíctimas y ciberagresores. Participaron 1.748 adolescentes del País Vasco, entre 13 y 17 años (52,6% chicas, 47,4% chicos), 12,5% no-heterosexuales, 87,5% heterosexuales, que cumplimentaron 4 instrumentos de evaluación. Se utilizó una metodología descriptiva y comparativa transversal. Los resultados confirman que: 1) el porcentaje de víctimas y cibervíctimas fue significativamente mayor en el grupo no-heterosexual, sin embargo, el porcentaje de agresores y ciberagresores heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales fue similar; 2) víctimas y cibervíctimas no-heterosexuales habían sufrido significativamente más cantidad de conductas agresivas de acoso/ciberacoso; 3) víctimas y agresores de acoso no-heterosexuales comparados con heterosexuales tenían significativamente más depresión, ansiedad social y síntomas psicopatológicos diversos (somatización, obsesión-compulsión, sensibilidad interpersonal…); 4) cibervíctimas y ciberagresores no-heterosexuales también presentaban más depresión y más síntomas psicopatológicos diversos, sin embargo, en ansiedad social no se hallaron diferencias. El debate se centra en la importancia de intervenir desde la familia, la escuela y la sociedad, para reducir el acoso/ciberacoso y estimular el respeto por la diversidad sexual.

ABSTRACT

Bullying and cyberbullying have negative consequences on adolescents’ mental health. The study had two objectives: 1) to analyze possible differences in sexual orientation (heterosexual and non-heterosexual) in the percentage of victims and aggressors of bullying/cyberbullying, as well as the amount of aggressive behavior suffered and carried out; 2) to compare the mental health of adolescent heterosexual and non-heterosexual victims, aggressors, cybervictims, and cyberaggressors. Participants included 1,748 adolescents from the Basque Country, aged between 13 and 17 years (52.6% girls, 47.4% boys), 12.5% non-heterosexuals, 87.5% heterosexuals, who completed 4 assessment instruments. A descriptive and comparative cross-sectional methodology was used. The results confirm that: 1) the percentage of victims and cybervictims was significantly higher in non-heterosexuals, but the percentage of heterosexual and non-heterosexual aggressors and cyberaggressors was similar; 2) non-heterosexual victims and cybervictims had suffered significantly more aggressive bullying/cyberbullying; 3) non-heterosexual victims and aggressors of bullying exhibited significantly more depression, social anxiety, and psychopathological symptoms (somatization, obsession-compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity…) than heterosexuals; 4) non-heterosexual cybervictims and cyberaggressors displayed more depression and more psychopathological symptoms, but no differences were found in social anxiety. The importance of intervening from the family, school, and society to reduce bullying/cyberbullying and enhance respect for sexual diversity is discussed.

Palabras clave

Acoso, ciberacoso, LGTB-fobia, orientación sexual, prevalencia, salud mental, homofobia, violencia escolar

Keywords

Bullying, cyberbullying, LGBT-phobia, sexual orientation, prevalence, mental health, homophobia, school violence

Introducción

En los últimos años, el acoso y ciberacoso ha generado gran preocupación social e interés en la comunidad científica. Acoso hace referencia a la existencia de una víctima indefensa, acosada por uno o varios agresores/as, que realizan frecuentemente conductas agresivas hacia la víctima (físicas, verbales, exclusión social…), con intencionalidad de hacer daño y desigualdad de poder. El ciberacoso es un nuevo tipo de acoso que utiliza las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación, Internet (correo electrónico, mensajería, chat, web, juegos...) y el teléfono móvil para acosar a compañeros. Una revisión de estudios epidemiológicos nacionales e internacionales ha identificado una prevalencia de acoso y ciberacoso relevante (2-12% víctimas; 1-10% cibervíctimas) (Garaigordobil, 2018), en la misma dirección que el reciente estudio de Save the Children (2016) con adolescentes españoles (9,3% víctimas; 6,9% cibervíctimas). El impacto de estas conductas puede ser devastador. Las personas con una orientación e identidad sexual no-normativa son un colectivo vulnerable (Poteat & Espelage, 2005), y sufren con mayor frecuencia acoso/ciberacoso y conductas agresivas LGTB-fóbicas. Acoso LGTB-fóbico se refiere al motivado por la fobia al colectivo LGTB, y homofobia/LGTB-fobia se define como una actitud hostil, de aversión… que considera que una orientación sexual no-normativa (homosexual, bisexual, transexual…) es inferior, patológica…, y las personas LGTB enfermas, desequilibradas, delincuentes…

El estudio se contextualiza en un marco teórico desde el que se considera que la conducta está influenciada por las normas sociales imperantes en el medio sociocultural, y que los estereotipos/prejuicios fomentados por una sociedad heteronormativa estigmatizan a las personas LGTB, justifican y promueven su acoso, lo que tiene un impacto muy negativo en su salud mental. En consonancia con la teoría de la identidad social, los individuos para mantener una identidad social positiva, tienden a sobrevalorar su grupo, atribuyéndole características positivas, en detrimento del exogrupo cuyo estereotipo es negativo. Esta categorización y desprecio fomenta y justifica las conductas agresivas hacia el otro grupo. Estudios muestran un incremento de los insultos homofóbicos con la edad (Espelage & al., 2017), siendo el contexto escolar el principal ámbito de su uso (Generelo & al., 2012), y los compañeros, especialmente los varones, tienen un papel importante en la formación de estos insultos (Birkett & Espelage, 2015). Dado el relevante papel del contexto educativo, es necesario evaluar las actitudes de los/las adolescentes ante la diversidad sexual y, si se requiere, intervenir para reforzar el respeto y la tolerancia por lo diferente.

Prevalencia del acoso y ciberacoso en personas LGTB

En relación al acoso, algunas investigaciones han revelado datos que oscilan entre 51% y 58% de victimización en personas con una orientación/identidad sexual no-normativa (Generelo, Garchitorena, Montero, & Hidalgo, 2012; Martxueta & Etxeberria, 2014). En ciberacoso, se han evidenciado porcentajes de cibervictimización entre 10% y 71% en las personas LGTB (Abreu & Kenny, 2017; COGAM, 2016; Cooper & Blumenfeld, 2012; Kosciw, Greytak, Giga, Villenas, & Danischewski, 2016). Las discrepancias entre estudios se explican por las diferentes edades de las muestras y por las diferentes conductas medidas.

Los estudios que se han centrado en comparar los niveles de victimización en función de la orientación sexual, sugieren que las personas no-heterosexuales sufren mayor porcentaje de conductas de acoso comparadas con las heterosexuales (Abreu & Kenny, 2017; Baiocco, Pistella, Salvati, Loverno, & Lucidi, 2018; Bouris, Everett, Heath, Elsaesser, & Neilands, 2016; Camodeca, Baiocco, & Posa, 2018; Collier, Bos, & Sandfort, 2013; COGAM, 2016; Elipe, De-la-Oliva-Muñoz, & Del-Rey, 2017; Gegenfurtne & Gebhardt, 2017; Toomey & Russel, 2016). Las investigaciones que analizan el rol de agresor desde la perspectiva de diversidad sexual se han centrado en mostrar prevalencias de agresores de conductas LGTB-fóbicas, pero no han comparado la perpetración de acoso/ciberacoso entre personas heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales.

Acoso/ciberacoso en personas LGTB y salud mental

Algunas investigaciones han evidenciado que las personas LGTB víctimas de acoso y ciberacoso en la escuela muestran depresión y ansiedad (Ferlatte, Dulai, Hottes, Trussler, & Marchand, 2015; Martxueta & Etxeberria, 2014; Wang & al., 2018), malestar psicológico (Birkett, Newcomb, & Mutanski, 2015), y riesgo de suicidio (Cooper & Blumenfeld, 2012; Duong & Bradshaw, 2014; Ferlatte & al., 2015; Luong, Rew, & Banner, 2018; Quintanilla, Sánchez-Loyo, Correa-Márquez, & Luna-Flores, 2015; Ybarra, Mitchell, Kosciw, & Korchmaros, 2014).

Pocos estudios comparan cibervíctimas y ciberagresores heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales en distintas variables de salud mental, para explorar si la cibervictimización de las personas LGTB se relaciona con mayor deterioro de su salud mental, comparada con la salud mental de cibervíctimas y ciberagresores heterosexuales. Cabe mencionar el estudio de Ybarra y otros (2014) que evidenció que la relación entre la ideación de suicidio y el acoso era más fuerte en las personas gais, lesbianas y queers, en comparación con bisexuales, heterosexuales y las que no estaban seguras de su orientación sexual. Por lo tanto, apenas existen investigaciones que realicen esta diferenciación con otras variables de salud mental.

Los estudios que se han centrado en comparar los niveles de victimización en función de la orientación sexual, sugieren que las personas no-heterosexuales sufren mayor porcentaje de conductas de acoso comparadas con las heterosexuales.

Objetivos e hipótesis

El estudio tuvo dos objetivos: 1) analizar si existen diferencias en función de la orientación sexual (heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales) en el porcentaje de víctimas y agresores de acoso y ciberacoso (víctimas, agresores, cibervíctimas, ciberagresores) y en la cantidad de conducta agresiva que sufren y realizan en ambos grupos; 2) comparar la salud mental (depresión, ansiedad social, sensibilidad interpersonal, somatización, ansiedad fóbica, ideación paranoide…) de heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales que han sido víctimas, agresores, cibervíctimas y ciberagresores. Con estos objetivos se formulan tres hipótesis:

- H1. El porcentaje de víctimas y cibervíctimas será significativamente mayor en el grupo de adolescentes no-heterosexuales, comparado con el porcentaje de víctimas y cibervíctimas del grupo heterosexual, mientras que no habrá diferencias en el porcentaje de agresores y ciberagresores heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales.

- H2. La cantidad de conducta sufrida por víctimas y cibervíctimas será significativamente mayor en el grupo de no-heterosexuales, comparada con la cantidad sufrida por las víctimas y cibervíctimas heterosexuales, sin embargo, no se hallarán diferencias entre ambas condiciones en la cantidad de conducta agresiva de acoso y ciberacoso realizada.

- H3. Víctimas, cibervíctimas, agresores y ciberagresores no-heterosexuales, comparados con los heterosexuales, tendrán significativamente peor salud mental, lo que se manifestará en más síntomas de depresión, ansiedad social, mayor psicopatología general y más síntomas psicopatológicos diversos (somatización, obsesión-compulsión, sensibilidad interpersonal, depresión, ansiedad, hostilidad, ansiedad fóbica, ideación paranoide, psicoticismo).

Material y métodos

Participantes

La muestra del estudio está constituida por 1.748 adolescentes de 13 a 17 años (52,6% chicas, 47,4% chicos), de 19 centros escolares. El 60,2% cursa 3º de Educación Secundaria y 39,8% estudia 4º curso (44,7% en centros públicos y 55,3% privados). Respecto a la orientación sexual, 87,5% son heterosexuales, 0,7% gais, 0,2% lesbianas, 5,7% bisexuales y 5,9% no estaban seguro/as de su orientación sexual; es decir, 12,5% no-heterosexuales y 87,5% heterosexuales. La muestra fue seleccionada aleatoriamente, siendo representativa de los/as estudiantes del último ciclo de Secundaria del País Vasco (N=37.575). Utilizando un nivel de confianza de 0,95, con un error muestral de 2,3%, la muestra representativa es 1.732. Para la selección de la muestra se utilizó una técnica de muestreo estratificado, teniendo en cuenta los siguientes parámetros: provincia, tipo de red (pública-privada) y nivel educativo (3º y 4º).

Instrumentos

Para medir las variables objeto de estudio, además de un cuestionario sociodemográfico en el que se solicitó información sobre la orientación sexual, se utilizaron cuatro instrumentos de evaluación con garantías psicométricas.

- Cyberbullying. Screening de acoso entre iguales (Garaigordobil, 2013; 2017). Evalúa acoso y ciberacoso. La escala de acoso mide cuatro tipos de acoso (físico, verbal, social, psicológico) y la escala de ciberacoso explora 15 conductas relacionadas con el acoso cibernético (enviar mensajes ofensivos/amenazadores, telefonear para insultar/amenazar, grabar una agresión/humillación y difundir el vídeo, crear rumores para difamar, robar la contraseña, aislar en redes sociales...). Los adolescentes informan de la frecuencia con la que han sufrido y realizado estas conductas en el transcurso de su vida. Se obtiene 4 puntuaciones: nivel de victimización, cibervictimización, agresión y ciberagresión. Los coeficientes alpha de Cronbach con la muestra original evidencian adecuada consistencia interna (acoso α=.81; ciberacoso α=.91), igual que en la muestra de este estudio (acoso α=.76; ciberacoso α=.84).

- Inventario de Depresión de Beck II (Beck & al., 1996; adaptación de Sanz, García-Vera, Espinosa, Fortún, & Vázquez, 2005). Compuesto por 21 ítems que miden la gravedad de la depresión. Los ítems miden síntomas de la depresión: tristeza, pesimismo, sentimiento de fracaso, pérdida de placer, sentimiento de culpa, sentimiento de castigo, insatisfacción con uno/a mismo/a, autocríticas, pensamientos de suicidio, llanto, agitación, pérdida de interés, indecisión, inutilidad, pérdida de energía, cambios en el patrón de sueño, irritabilidad, cambios en el apetito, dificultad de concentración, cansancio o fatiga y pérdida de interés por el sexo. El adolescente informa del grado en el que ha tenido esos síntomas durante las dos últimas semanas. Los coeficientes alpha con la muestra original fueron adecuados (α=.87), igual que con la muestra de este estudio (α= .84).

- Escala de Ansiedad Social para Adolescentes (SAS-A) (La-Greca & Stone, 1993; adaptación española Olivares & al., 2005). Formada por 22 ítems, evalúa la ansiedad social global (fobia social) y 3 subdimensiones: miedo a la evaluación negativa; evitación social y distrés ante situaciones y personas desconocidas; y ante la compañía de conocidos. Los adolescentes informan de la frecuencia con la que tienen (nunca-siempre) los pensamientos, sentimientos, conductas… La consistencia interna de la prueba con la muestra original fue alta (α=.91), igual que con la muestra de este estudio (α=.87).

- SCL-90-R. Cuestionario de 90 síntomas revisado (Derogatis, 2002). Contiene 90 ítems en nueve escalas que informan de alteraciones psicopatológicas: somatización (vivencias de disfunción corporal, alteraciones neurovegetativas de sistemas cardiovascular, respiratorio, gastrointestinal y muscular), obsesión-compulsión (conductas, pensamientos… absurdos e indeseados que generan intensa angustia y que son difíciles de resistir, evitar o eliminar), sensibilidad interpersonal (timidez y vergüenza, incomodidad e inhibición en las relaciones interpersonales), depresión (anhedonia, desesperanza, impotencia, falta de energía, ideas autodestructivas…), ansiedad (generalizada y aguda/pánico), hostilidad (pensamientos, sentimientos y conductas agresivas, ira, irritabilidad, rabia y resentimiento), ansiedad fóbica (agorafobia y fobia social), ideación paranoide (conducta paranoide, suspicacia, ideación delirante, hostilidad, grandiosidad, necesidad de control…), y psicoticismo (sentimientos de alienación social). Del sumatorio de las puntuaciones de las escalas se obtiene una puntuación total en el SCL-90-R (grado general de psicopatología). Estudios con muestra española sugieren buena fiabilidad de la prueba (α=.81 a.90), igual que en este estudio (α=.97).

Procedimiento

Este estudio utiliza una metodología descriptiva y comparativa de corte transversal. En primer lugar, se envió una carta a los centros educativos seleccionados aleatoriamente explicando la investigación. Aquellos que aceptaron participar recibieron los consentimientos informados para padres y participantes. Posteriormente, el equipo evaluador se desplazó a los centros y administró a los estudiantes los instrumentos de evaluación (1 sesión de 50 minutos). El estudio cumplió los valores éticos requeridos en la investigación con seres humanos, habiendo sido evaluado favorablemente por la Comisión de Ética de la UPV/EHU (M10_2017_094).

Análisis de datos

Para conocer la prevalencia de estudiantes víctimas, cibervíctimas, agresores y ciberagresores, heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales, se calculan las frecuencias/porcentajes de estudiantes que ha sufrido y realizado conductas de acoso/ciberacoso frecuentemente (bastantes veces + siempre), y mediante análisis de contingencia, se obtienen las Chi cuadrado de Pearson comparando ambas condiciones.

En segundo lugar, para identificar si existen diferencias en función de la orientación sexual en los 4 indicadores de acoso/ciberacoso (victimización, cibervictimización, agresión, ciberagresión), se llevan a cabo análisis descriptivos (medias y desviaciones típicas), análisis de varianza univariantes y del tamaño del efecto (d de Cohen: pequeño<.50; moderado .50-79; grande ≥.80) con las puntuaciones de heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales.

Finalmente, para explorar si existen diferencias en función de la orientación sexual (heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales) en diversos síntomas psicopatológicos (salud mental), se selecciona la muestra de víctimas de acoso (habían informado haber sufrido conductas agresivas de acoso durante su vida), y se realizan análisis de varianza (MANOVA; ANOVA) en función de la pertenencia al grupo heterosexual y no-heterosexual. El mismo procedimiento se opera con cibervíctimas, agresores y ciberagresores respectivamente. El análisis de datos se realiza con el programa SPSS 24.0.

Resultados

Prevalencia de víctimas y cibervíctimas heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales

Los resultados del porcentaje de estudiantes heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales que habían sufrido frecuentemente (bastantes veces + siempre) conductas de acoso y ciberacoso fueron: 1) víctimas severas: 11% (n=193) de las víctimas habían sufrido conductas de acoso frecuentemente en el transcurso de su vida.

El porcentaje de heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales víctimas severas sobre la muestra en cada grupo de orientación sexual fue 9% heterosexuales (n=138) y 25,1% no-heterosexuales (n=55). El porcentaje de víctimas fue significativamente mayor en el grupo no-heterosexual (X²=50,48, p<.001); 2) cibervíctimas severas: 7,2% (n=126) de las víctimas había sufrido ciberacoso frecuentemente. El porcentaje de heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales cibervíctimas severas sobre la muestra en cada grupo de orientación sexual fue 6,2% heterosexuales (n=95) y 13,7% no-heterosexuales (n=30).

El porcentaje de cibervíctimas fue significativamente mayor en el grupo no-heterosexual (X²=16,16, p<.001). Así, el porcentaje de víctimas y cibervíctimas fue significativamente mayor en el grupo no-heterosexual, comparado con el porcentaje de víctimas y cibervíctimas del grupo heterosexual.

Prevalencia de agresores y ciberagresores heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales

Los resultados del porcentaje de estudiantes heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales que habían realizado frecuentemente (bastantes veces + siempre) conductas de acoso y ciberacoso fueron: 1) agresores severos: 2,7% (n=47) había realizado conductas de acoso frecuentemente.

El porcentaje de heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales agresores/as severos/as sobre la muestra en cada grupo de orientación sexual fue 1,7% heterosexuales (n=38) y 0,9% no-heterosexuales (n=9). No se hallaron diferencias significativas en función de la orientación sexual (X²=0,75, p>.05); 2) ciberagresores severos: 1,6% (n=28) ha realizado conductas de ciberacoso frecuentemente.

El porcentaje de heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales ciberagresores/as severos/as sobre la muestra en cada orientación sexual fue 1,7% heterosexuales (n=26) y 0,9% no-heterosexuales (n=2). No se hallaron diferencias significativas (X²=0,75, p>.05). Así, el porcentaje de adolescentes agresores y ciberagresores heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales fue similar.

Niveles de victimización, cibervictimización, agresión y ciberagresión

Sobre las diferencias en el nivel de victimización y cibervictimización en función de la orientación sexual, los resultados (Tabla 1) muestran que víctimas/cibervíctimas no-heterosexuales comparadas con las heterosexuales habían sufrido significativamente más cantidad de conductas agresivas de acoso y ciberacoso (tamaño del efecto moderado en victimización).

En relación al nivel de agresión y ciberagresión (Tabla 1), los resultados muestran que la cantidad de conducta agresiva cara-a-cara realizada fue significativamente mayor en el grupo no-heterosexual, sin embargo, la cantidad de conducta de ciberacoso realizada fue similar en ambos grupos.

En síntesis, víctimas y cibervíctimas no-heterosexuales habían sufrido significativamente más cantidad de conductas agresivas de acoso y ciberacoso durante su vida. Los agresores no-heterosexuales habían realizado significativamente más cantidad de conductas agresivas cara-a-cara, aunque no se hallaron diferencias en la cantidad de conducta realizada por los ciberagresores de ambas condiciones.

|

|

Victimización y cibervictimización en la salud mental de los adolescentes LGTB

Respecto a las diferencias en síntomas psicopatológicos entre víctimas y cibervíctimas en función de la orientación sexual (heterosexuales, no-heterosexuales), los análisis multivariantes (MANOVA) realizados con el conjunto de las variables de salud mental revelan diferencias significativas entre las víctimas de acoso heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales, Lambda de Wilks, Λ=0,942, F(13,708)=3,36, p<.001 (tamaño de efecto pequeño, η2=0,058, r=0,24).

Los mismos resultados se hallan en las cibervíctimas, Lambda de Wilks, Λ=0,953, F(13,618)=2,34, p<.05 (tamaño de efecto pequeño, η2=0,047, r=0,22).

Los resultados de los análisis descriptivos, univariantes y del tamaño del efecto en cada variable se presentan en la Tabla 2. Las víctimas y cibervíctimas no-heterosexuales tienen significativamente mayor psicopatología que las víctimas/cibervíctimas heterosexuales (tamaño del efecto moderadamente-bajo y bajo).

Los análisis de varianza (Tabla 2) confirman que las víctimas no-heterosexuales (comparadas con las heterosexuales) muestran puntuaciones significativamente superiores en depresión (BDI-II), en ansiedad social global (SAS) (evitación y malestar social con conocidos/as y extraños/as), en todos los síntomas psicopatológicos del SCL-90 (somatización, obsesión-compulsión, sensibilidad interpersonal, depresión, ansiedad, hostilidad, ansiedad fóbica, ideación paranoide, psicoticismo), así como en la puntuación global de psicopatología.

Las cibervíctimas no-heterosexuales (comparadas con las heterosexuales) (Tabla 2) muestran puntuaciones significativamente superiores en depresión (BDI-II) y en todos los síntomas psicopatológicos evaluados con el SCL-90 excepto en obsesión-compulsión. Sin embargo, las cibervíctimas no-heterosexuales tuvieron similar nivel de ansiedad social global (fobia social) que las cibervíctimas heterosexuales, aunque tuvieron mayor nivel de ansiedad ante los conocidos.

|

|

Salud mental diferencial de los adolescentes LGTB agresores y ciberagresores

Sobre las diferencias en síntomas psicopatológicos entre los agresores y ciberagresores en función de la orientación sexual (heterosexuales, no-heterosexuales), los análisis multivariantes (MANOVA) con el conjunto de las variables de salud mental revelan diferencias significativas entre los agresores heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales, Lambda de Wilks, Λ=0,923, F(10,479)=3,07, p<.001 (tamaño de efecto pequeño, η2=0,07, r=0,27). Idénticos resultados se hallan en ciberagresores, Lambda de Wilks, Λ=0,923, F(13,300)=1,92, p<.05 (tamaño de efecto pequeño, η2= 0,077, r=0,28). Por consiguiente, agresores y ciberagresores no-heterosexuales en general tienen significativamente mayor psicopatología que agresores y ciberagresores heterosexuales. Los resultados de los análisis descriptivos, univariantes y del tamaño del efecto, en cada variable objeto de estudio, se presentan en la Tabla 3.

Como se puede observar (Tabla 3) los agresores no-heterosexuales (comparados con los heterosexuales) tienen significativamente más depresión (BDI-II), más ansiedad social (SAS), más síntomas psicopatológicos evaluados con el SCL-90 (somatización, obsesión-compulsión, sensibilidad interpersonal, depresión, ansiedad, hostilidad, ansiedad fóbica, ideación paranoide, psicoticismo), y en la puntuación global de psicopatología. Los ciberagresores no-heterosexuales tienen significativamente más depresión (BDI-II), y más síntomas psicopatológicos (obsesión-compulsión, sensibilidad interpersonal, depresión, ansiedad, hostilidad, ansiedad fóbica, ideación paranoide, psicoticismo), excepto en síntomas de somatización. Además, en ansiedad social global no se hallaron diferencias entre ciberagresores heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales (tamaño del efecto moderado en depresión y puntuación global de psicopatología).

|

|

Discusión y conclusiones

El estudio tuvo como objetivos analizar si existen diferencias en función de la orientación sexual (heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales) en el porcentaje de víctimas y agresores de acoso y ciberacoso y en la cantidad de conducta agresiva que sufren y realizan; además, compara la salud mental de heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales que han sido víctimas, agresores, cibervíctimas y ciberagresores.

En primer lugar, los resultados confirman que el porcentaje de víctimas y cibervíctimas fue significativamente mayor en los adolescentes no-heterosexuales, comparado con el porcentaje de víctimas y cibervíctimas heterosexuales. Sin embargo, el porcentaje de agresores y ciberagresores heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales fue similar. La hipótesis uno se ratifica. Además, la prevalencia general de acoso y ciberacoso encontrada en este estudio (11% víctimas; 7,2% cibervíctimas) confirma la hallada en revisiones y estudios epidemiológicos recientes (Garaigordobil, 2018; Save the Children, 2016). En segundo lugar, los resultados muestran que víctimas/cibervíctimas no-heterosexuales, comparadas con víctimas/cibervíctimas heterosexuales, habían sufrido más cantidad de conductas agresivas de acoso y ciberacoso. Los agresores no-heterosexuales habían realizado significativamente más cantidad de conductas de acoso, aunque no se hallaron diferencias en ciberagresores. La hipótesis dos se ratifica parcialmente, ya que también se ha encontrado que los agresores no-heterosexuales realizan más cantidad de conductas agresivas de acoso que los heterosexuales.

Se confirma la alta vulnerabilidad que sufren las personas que se alejan de los estereotipos basados en la heteronormatividad. Los resultados apuntan en la misma dirección que otros estudios que han evidenciado que el colectivo LGTB es un colectivo con mayor vulnerabilidad de padecer conductas de acoso y ciberacoso (Abreu & Kenny, 2017; Baiocco & al., 2018; Birkett & al., 2009; Bouris & al., 2016; Camodeca & al., 2018; Collier & al., 2013; COGAM, 2016; Elipe & al., 2017; Gegenfurtne & Gebhardt, 2017; Pichardo & al., 2002; Shields & al., 2012; Toomey & Russel, 2016). No habiendo estudios que hayan comparado la prevalencia de agresores/ciberagresores entre heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales, los resultados de este estudio implican una contribución al conocimiento.

En tercer lugar, los resultados muestran que víctimas y agresores no-heterosexuales (comparados con víctimas y agresores heterosexuales) tienen significativamente más depresión, ansiedad social, y más síntomas psicopatológicos en todas las escalas (somatización, obsesión-compulsión, sensibilidad interpersonal, depresión, ansiedad, hostilidad, ansiedad fóbica, ideación paranoide, psicoticismo). Cibervíctimas y ciberagresores no-heterosexuales (comparados con los heterosexuales) presentan significativamente más depresión y más síntomas psicopatológicos diversos (sensibilidad interpersonal, depresión, ansiedad, hostilidad, ansiedad fóbica, ideación paranoide, psicoticismo). En ansiedad social global no se hallaron diferencias entre cibervíctimas y ciberagresores heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales. Se ratifica la hipótesis tres casi en su totalidad, ya que no se ha encontrado mayor ansiedad social en cibervíctimas y ciberagresores no-heterosexuales.

Por consiguiente: 1) víctimas y agresores no-heterosexuales (versus heterosexuales) muestran más síntomas en todos los trastornos psicopatológicos evaluados (somatización, obsesión-compulsión, sensibilidad interpersonal, depresión, ansiedad, hostilidad, ansiedad fóbica, ideación paranoide, psicoticismo, ansiedad social); 2) cibervíctimas y ciberagresores no-heterosexuales (versus heterosexuales) tienen más síntomas psicopatológicos diversos (sensibilidad interpersonal, depresión, ansiedad, hostilidad, ansiedad fóbica, ideación paranoide, psicoticismo), aunque no tienen más ansiedad social; además las cibervíctimas no-heterosexuales no tienen más síntomas de obsesión-compulsión, ni los ciberagresores muestran más somatización; 3) víctimas no-heterosexuales tienen mayor ansiedad/fobia social que las cibervíctimas no-heterosexuales.

Aunque no hay estudios previos que comparan diversos síntomas psicopatológicos en heterosexuales y no-heterosexuales que han sufrido y/o realizado acoso/ciberacoso, lo que representa una aportación de este trabajo, los resultados obtenidos confirman los hallados en investigaciones que han evidenciado síntomas psicopatológicos en víctimas con una orientación sexual no-normativa, encontrando también depresión y ansiedad (Ferlatte & al., 2015; Martxueta & Etxeberria, 2014; Wang & al., 2018).

El estudio aporta datos de la prevalencia del acoso/ciberacoso LGTB-fóbico, y muestra que las personas LGTB además de sufrir acoso/ciberacoso con mayor frecuencia, también desarrollan más síntomas psicopatológicos por la victimización/cibervictimización sufrida, que aquellos que sufriendo acoso/ciberacoso son heterosexuales. Entre las limitaciones del estudio cabe destacar: 1) el uso de autoinformes con el sesgo de deseabilidad que implican; 2) aunque existe mayor visibilización de las personas LGTB, muchas personas viven a la sombra su propia sexualidad.

Si esta es una realidad para la población en general, los adolescentes sienten aún mayor dificultad para identificarse como no-heterosexuales, por ello, en el estudio emerge un porcentaje de adolescentes que no están seguros, y que se han incluido dentro del grupo no-heterosexual, como han realizado otros investigadores; 3) la naturaleza transversal del estudio, que no permite realizar inferencias causales. Futuros estudios podrían analizar el rol de víctima-agresor, ampliar la muestra LGTB, realizar análisis en función de la edad y sexo, y diseñar programas antiacoso basados en el estigma, evaluando sus efectos en los estereotipos y prejuicios hacia personas LGTB. Se puede considerar que tanto las conductas agresivas ante la diversidad sexual, como la discriminación internalizada que caracteriza a las personas LGTB son fruto de una sociedad que está educada por un sistema heteronormativo. Los niños y niñas no nacen homófobos, son modelados desde que nacen mediante los mensajes recibidos desde su entorno familiar, escolar y social. Por ello, es necesario educar sobre la orientación/identidad sexual desde distintos contextos, para que los niños y niñas crezcan en el respeto hacia las diferencias en general y hacia la diversidad sexual en particular.

Los resultados tienen implicaciones prácticas y sugieren la necesidad de desarrollar actividades específicas durante la infancia y la adolescencia que estimulen el respeto y la tolerancia hacia la diversidad sexual, y actividades dentro de programas antiacoso que aborden el acoso/ciberacoso LGTB-fóbico, debido a la orientación/identidad sexual no-heteronormativa. Entre estos programas mencionar Cyberprogram 2.0, un programa de intervención para prevenir el ciberacoso que aborda en diversas actividades el acoso debido a la orientación sexual (por ejemplo, secretos a cibervoces, sexting, falsas promesas…).

El programa ha sido evaluado experimentalmente, confirmando una reducción del acoso y ciberacoso (Garaigordobil & Martínez-Valderrey, 2014; 2015; 2018). Earnshaw y otros (2018) observan un aumento en las intervenciones para abordar la intimidación basadas en el estigma (a jóvenes LGBTQ, con sobrepeso, con discapacidades…). Sin embargo, actualmente muchos centros educativos españoles, aunque realizan actividades antiacoso, pocos programas contienen estrategias específicas para reducir los estereotipos y prejuicios, necesarias para abordar el acoso basado en el estigma. Futuras propuestas de intervención deben incluir estrategias de este tipo para afrontar el acoso hacia colectivos estigmatizados.

Finalizar destacando que la intervención para reducir la estigmatización y el acoso/ciberacoso a las personas LGTB debe ser multidireccional. La educación familiar en la tolerancia a la diversidad desempeña un papel primordial. La escuela es un contexto relevante para realizar actividades antiacoso que pongan el foco en colectivos vulnerables, fomentando la tolerancia ante la diversidad. Un tercer eje de intervención debe ser la sociedad en general, ya que las normas y valores que fomenta condicionan la conducta. Sería importante difundir mensajes de tolerancia a través de los medios de comunicación (TV, radio, prensa, Internet, redes sociales…), ya que estos medios son instrumentos privilegiados para fomentar la empatía y tolerancia hacia la diversidad en general y la sexual en particular, eliminando estereotipos y prejuicios. No obstante, no se debe olvidar la intervención clínica, por el riesgo de suicidio de las personas que sufren acoso/ciberacoso LGTB-fóbico.

References