Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Resumen

The mediated use of technology fosters learning from early childhood and is a potential resource for inclusive education. Nevertheless, the huge range of options and exposure to interactive digital content, which is often online, also implies a series of risks. The definition of protection underlying the current strategies to protect children is inadequate as it only extends to reducing children's exposure to harmful content. This study proposes the expansion of this definition. Through systematic observation of 200 apps within the Catalan sphere for children under 8 years of age and principal component analysis, the results support a multidimensional conceptualisation of protection which, instead of being restricted to the potential risks, also considers aspects related to the educational and inclusive potential of digital resources. Five factors are suggested in order to select these resources and contribute to the digital competence of teachers and students. The first factor concerns the use of protection mechanisms and the existence of external interference, the second factor indicates the presence of adaptation tools; the exposure to stereotypes corresponds to the third factor and the last two consider the previous knowledge required and the verbal component of the apps. Finally, the scope of the suggested definition and its limitations as a guide for future analysis will be discussed.

Resumen

El uso mediado de la tecnología fomenta el aprendizaje desde la infancia y representa un potencial recurso para la educación inclusiva. Al mismo tiempo, la creciente exposición a contenidos digitales interactivos, a menudo conectados a la red, conlleva una serie de riesgos para los niños. A las estrategias actualmente empleadas para protegerlos, que se limitan a reducir su exposición a contenidos perjudiciales, parece subyacer una definición de protección inadecuada. Esta investigación propone que se amplíe esta definición. A través de una observación sistemática de 200 apps para menores de ocho años en el ámbito catalán y un análisis de componentes principales, se propone una definición multidimensional de protección que no se limita a detallar los riesgos potenciales, sino que también considera aspectos relacionados con el potencial educativo e inclusivo de los recursos digitales. Se sugieren cinco factores a considerar para seleccionar estos recursos y contribuir a la competencia digital de docentes y alumnos. El primer factor concierne al uso de mecanismos de protección y la existencia de interferencias externas; el segundo factor indica la presencia de herramientas de adaptación; la exposición a estereotipos corresponde al tercer factor y los últimos dos consideran los conocimientos previos requeridos y el componente verbal de las apps. Finalmente se discute el alcance de la definición propuesta y sus limitaciones para guiar análisis futuros.

Keywords

Children, educational technology, apps, safety, inclusive education, content analysis, protection of minors, cybersafety, digital competence

Keywords

Niños, tecnología educativa, apps, seguridad, educación inclusiva, análisis de contenido, protección de menores, ciberseguridad, competencia digital

Introduction

Data from the report “EU Kids online” (Livingstone, 2014) and Nielsen Group (2012) relating to the adoption of technologies by children and young people in Europe shows they connect to the internet on a daily basis, using various devices (mobile phones in particular), and at an increasingly young age. This trend has continued to date.

According to the OFCom report (2017), 65% of children aged between 3 and 4 and 75% of those aged between 5 and 7 years old use tablets on a daily basis in the UK, and 23% in the age range 3 to 4 and 47% of those aged 5 to 7 use smartphones. The Common Sense Census corroborates these data (Rideout, 2017). At the same time, the number of apps for pre-school age children has increased considerably (the Apple Store alone has over 80,000 apps for children, in line with the growing demand for digital tools from educators and families that can help children to learn, play and entertain themselves (Troseth, Russo, & Strouse, 2016). The contextual framework for this research focuses on the Catalan sphere, which has registered exponential growth in its digital games industry since 2012, as noted in the report “Llibre blanc de la indústria catalana del videojoc” (Desarrollo Español de Videojuegos, 2016).

The possible benefits for learning processes that may derive from digital games in general, and for children in particular, is one of the most extensively debated issues in the literature. In fact, the learning potential offered by interactive digital resources is widely supported (Herodotou, 2017; Flewitt, Messer, & Kucirkova, 2015; Kirkorian & Pempek, 2013), although children’s exposure to potentially harmful online content generates controversy. In this regard, the European Commission (2006) identifies three macro-categories of risks for underage users: risks related to getting in touch with strangers (cyber-bullying, grooming and sexting), rather than exposure and access to different kinds of inappropriate and harmful content (for instance pornography or violence), or privacy risks (for example, services that use geo-localization).

Lievens (2015) also notes the existence of three types of online risks for children: those related to content, in which the child is a recipient; risks relating to contact, in which they are proactive participants; and behavioural risks, in which the child is an actor who breaches certain behavioural rules (e.g. making purchases or downloading illegal content). This type of classification makes clear the complexity of the phenomenon as well as the different types of threat children face online and offline, implying that new measures for prevention and protection need to be found.

With this objective in mind, the European Union report establishing a “European framework for the digital competence of educators” (Redecker, 2017) stresses that safety measures cannot be limited to setting up external barriers (preventing access to potentially harmful content, for instance). Instead, the priority should be to empower learners to identify and manage risks autonomously. Following the conclusions of Livingstone, Mascheroni and Staksrud (2015), an educator’s role as a mediator is a key factor in limiting the potential risks associated with the use of technologies in online settings. However, the ability to select the most suitable devices and content “should not be taken for granted” (Felini, 2015: 114).

Scholars generally agree that the gatekeepers of children’s technology use need support (in terms of information or training) to perform this selection and to understand the risks associated with the use of mobile devices (European Commission, 2015; De Haan, Van-der-Hof, Bekkers, & Pijpers, 2013). At the same time, however, they stress the need for a structural change that could redefine educators’ skills within the framework of a more general process of pedagogical innovation (Howard, Yang, Ma, Maton, & Rennie, 2018; Redecker, 2017; Suárez-Guerrero, Lloret-Catalá, & Mengual-Andrés, 2016).

On the other hand, initiatives such as the International Age Rating Coalition (IARC) have attempted to enable parents and educators to select digital resources by classifying digital content for suitable age groups. IARC is used worldwide and is currently the system adopted to classify all apps in the Windows Store for PCs, tablets and smartphones. It has the added value of allowing the target age to be identified using an ad hoc classification for each country, such as the Pan European Game Information (PEGI) system in Europe, which was formerly used to classify audiovisual and console video games by age. PEGI classifies content according to five age groups: 3, 7, 12, 16 and 18. To determine the classifications it uses a residual definition, meaning the product is considered suitable for all ages (PEGI 3) or for children aged 7 or above (PEGI 7) if it does not include the following disturbing elements: violence, bad language, horror, or anything that may be frightening, explicit references to drugs and/or sex, discrimination, gambling or betting, or online gaming with other people. Indeed, developers of games targeting children under 8 years old do not tend to include explicit scenes of violence or the other elements mentioned, but it does not necessarily follow that all video games devoid of this type of content will have been developed with children in mind.

The limited classification criteria may explain why, according to the PEGI report (2013), 58% of the total 25,387 content items classified using the PEGI system between 2003 and 2015 were deemed to be PEGI 3 or PEGI 7; in other words, suitable for children. Similarly, the “Anuario de la industria del videojuego” (AEVI, 2013) highlights the fact that over half the 20 best-selling videogames are classified as suitable for PEGI 3 (for all audiences) or PEGI 7. These data underscore the limited ability of the current definition of protection to engender the reality of the risks children face, for instance, the risk of exclusion or exposure to more normalised but no less harmful content (such as stereotypes related to ethnicity or gender).

The current definition of protection circumscribes the task of prevention to reducing the potential risks and children’s exposure to harmful content, thus situating the child-player as a mere object of protection.

The limitations that affect the current attempts at regulation derive from a definition of “protection” which falls short for two reasons, the first being that the definition is merely residual (i.e. the absence of certain threats deems the content to be appropriate), whilst the second is that it does not take into account the suitability of the apps’ characteristics for the target audience, infringing children’s right to participation in and access to Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) as laid down by the United Nations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child (Assembly of the United Nations, 1989) and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Assembly of the United Nations, 2006). For instance, it has been proven that digital games can increase social skills (e.g. self-concept, self-efficacy, awareness of emotions, etc.) and communicative skills in children with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) (Hourcade & al., 2013; Gay & Leijdekkers, 2014) and with Down’s syndrome (Porter, 2018; Yussof & al., 2016). However, to fully take advantage of these possible benefits, teachers need to know which digital resources are most suited to students and how to guarantee the safe use of technology during the learning process (Soler, López-Sánchez, & Lacave, 2018).

The first step is to agree on a definition, which will depend on the role attributed to child players. In the author’s view, the current definition of protection circumscribes the task of prevention to reducing the potential risks and children’s exposure to harmful content, thus situating the child-player as a mere object of protection. In contrast, initiatives such as the Better Internet for Kids campaign by the European Commission (2012) place particular emphasis on the need to promote activities to empower children from an early age in order to foster their engagement in the digital world. And teachers play a key role in this regard.

Taking into account these limitations, this research defends a broader conceptualisation of child protection in line with that established by BinDhim and Trevena (2015), encompassing both the absence of threats and accessibility. From this perspective, the research is grounded on the paradigm of Universal Design for ICT, envisaging accessible design that can adapt to all boys and girls, both with normal development and special educational needs (Holt, Moore, & Beckett, 2014; Sobel, O’Leary, & Kientz, 2015; Odom, & Diamond, 1998). The research aims to offer a new and more critical and ethical perspective on the concept of protection related to underage users. To explore the theoretical-empirical consistency of this definition, and to establish which aspects teachers should take into account when selecting educational digital tools, we conducted a content analysis and principal component analysis, that are explained below.

Instruments and method

Sample and features of the selected apps

The sample was limited to apps targeting children under 8 years old (apps classified as PEGI 3 and PEGI 7 and/or 4+ in the Apple Store), due to the scarcity of studies focusing on early childhood and the need to consider the specific features of child development during the first few years of life.

Apps were selected using a search engine (Google Search) and two databases (Apple Store and Google Play Store) and based upon two inclusion criteria: 1) the app should be aimed at children from 0 to 7 years old following the explicit statement of the developer or, if this information was not available, by the distributors; 2) the app developer should be based in Catalonia and/or at least one version of the app should be in Catalan (see Acknowledgments).

To ensure a heterogeneous sample, simple random sampling was used to exclude apps by the same developers with the same programming and visual engine but different content (for example: colouring in princesses, colouring in cars, colouring in animals). Using these criteria, the final sample included 200 apps in Catalan or developed in Catalonia aimed at children under 8 years old.

The apps analysed were created by 87 different developers and were all launched between 2011 and 2017. Due to the geographic focus of the research, 80% of the apps in the sample were developed in Spain (149 in Catalonia and 11 outside this region). 47% of the sample works on more than one operating system and 34.5% (n=69) are completely free. Of the paid-for apps, 36 cost less than €3, 15 between €3 and €10 and 3 between €10 and €30.

Analytical approach

The methodology used in the research was content analysis through structured observation, which is usually used in the study of digital and interactive applications for children (Amy, Alisa, & Andrea, 2002; Bruckman & Bandlow, 2002). The methodological framework of the project is the post-positivist research paradigm (Creswell, 2008). The observation sheet used to perform the content analysis was composed of a total of twenty variables, of which six were descriptive and dichotomous and aimed at identifying some basic features of the apps, such as: a) whether the app is aimed at a group with special educational needs; b) whether the responses adapt to the user; c) whether it includes the option to select different levels of difficulty; d) whether it can be used offline; e) whether it can be used by multiple players; and finally, f) whether it uses geolocation systems.

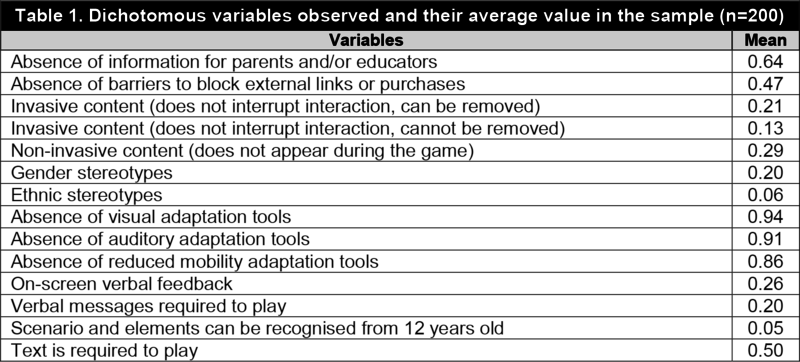

Table 1 shows the other variables —also dichotomous (presence=1 / absence=0) used for the operationalization of the "child protection" construct, considering the safe use of digital content and its accessibility.

|

|

As defined by Cusack (2013: 17), "‘gender stereotyping’ is the practice of ascribing to an individual man or woman specific attributes, characteristics or roles by reason only of her or his membership in the social group of men or women".

As regards the procedure, a researcher carried out observation of the 200 apps in the sample in the last quarter of 2017 using an iPad and a Samsung Galaxy tablet. The observation protocol of each app involved an initial 10-minute interaction with the game, after which the researcher started coding the information using an Excel sheet. During the coding process the researcher was free to return to the app as necessary and with no time restrictions until the analysis form was complete.

Nine experts, six women and three men, validated the observation sheet (content validity by expert judgments): five professors (three from the area of education technology and two from special and inclusive education); a full professor in education and mother of two children under eight, one of them with Down’s syndrome; a children's app developer; a communication professional and father of three children under the age of 8; and a nursery school teacher with vast experience in educational inclusion and pre-schoolers with functional diversity. Two researchers conducted a pilot test, independently observing the same three apps, which were not included in the final sample.

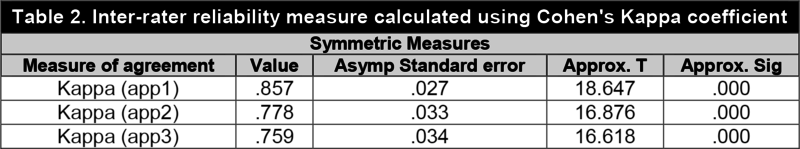

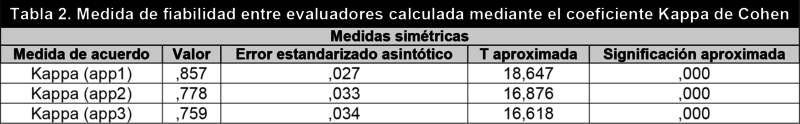

Table 2 shows the results of the inter-rater reliability measure for the three apps, which show a very good level of agreement (Landis & Koch, 1977).

|

|

An analysis of the observed frequencies and contingency tables was chosen to describe the characteristics of the apps analysed. Following this, principal component analysis was conducted (hereinafter referred to as PCA) to observe the eigenvalues of each component. PCA was performed using the Varimax orthogonal rotation method. Descriptive and inferential statistical analysis was performed using statistics software IBM SPSS Statistics.

Results

Description of the sample of 200 apps

In terms of the target age group, it is notable that in 126 cases the developer does not state the group the app is designed for, and in 9 the app is stated as suitable for all ages. In other words, 67.5% of the apps do not include any precise instructions from the developers with regard to the target age group. 163 of the apps can be used offline (81.5%), 27 can be used offline without access to all content (13.5%) and 10 cannot be used offline (5%). When it comes to privacy, the presence and use of geolocation systems was considered, but was only recorded in 2 apps.

To stimulate collaborative and inclusive peer-to-peer play, apps need to allow games to be played by more than one user. However, 177 apps (88.5%) are designed for a single player. Only 13 apps are explicitly aimed at a particular group (children with ASD, Down’s syndrome, attention deficit disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or other learning disorders). In 9 cases (3 in apps for children with ASD) the apps are adaptive (4.5%) —in other words, the user's response determines the difficulty of the game— whereas 73 apps include the option to choose different levels of difficulty (36.5%).

Adequacy with the protection and safety assumptions for children under eight years' old

A descriptive analysis was carried out of the characteristics of the apps according to the definition of child protection used in this research, encompassing both the idea of safety in the strict sense and elements related to access in the design and content of apps for children. 35% of the sample provides information for parents and/or educators in the application itself, and 1.5% provides a link via an external website. In other words, only 36.5% contain information for parents and educators.

Barriers to block children from accessing external links or purchases during the game are incorporated in 57 apps (28.5%). Considering they are not necessary in another 49 cases (24.5%), 47% of the sample does not comply with the requirement to prevent access (involuntary or conscious) to external links or purchases by children. Likewise, only 40.5% of the apps analysed are free from external interference, with most exhibiting at least one of the following features:

- Invasive advertisements or messages that interrupt the interaction (n=7; 3.5% of the sample).

- Invasive advertisements or messages that, despite not interrupting the interaction, cannot be removed (n=25; 12.5%);

- Invasive advertisements or messages that do not interrupt the interaction but can be removed, for example by clicking on the “x” symbol to close the window (n=41; 20.5%);

- Non-invasive advertisements or messages that do not appear during the game (n=58; 29%).

As expected, none of the content covered by PEGI was found, although gender stereotypes were found in 39 cases (19.5%), and ethnic stereotypes in 11 cases (5.5%). In terms of aspects related to accessibility, three different dimensions were considered: the range of strategies or mechanisms for visual, auditory and motor adaptation. Visual adaptation tools were only found in 13 apps (6.5%). From these, only 3 apps allow identification, inversion or adaptation of colours, 7 allow text size to be changed, 6 the screen or element size to be changed and 2 have a voice-over. Similar data was recorded with the visual adaptation tools (only 13 apps analysed included these) and auditory adaptation tools (19 apps).

Finally, tools to adapt to reduced physical and motor skills were found in 28 cases (14%). The sample therefore has serious shortcomings in terms of accessibility, especially if we consider that none of the apps analysed allow the keyboard to be adapted or the use of external devices for reduced mobility. Only two apps recognise drawing on the screen and two allow the use of alternative gestures as a different mode of interacting with the screen and achieving the goal of the game (i.e. tap instead of drag).

Approximately half the sample (109 apps, 54.5%) does not include verbal messages. In 40 apps (20%) verbal messages are essential to play, which presents both cognitive and communicative adaptation problems for some groups with special educational needs. Conversely, feedback on the game screen is verbal in 25.5% of the cases analysed. In relation to the adequacy for the target, text was identified as necessary to play in 99 apps (49.5%).

Exclusively taking into account the 70 apps explicitly aimed at children aged 6 or under (at pre-school age reading and writing skills are not usually developed), text is necessary to be able to play in over half (n=37; 53%). Bearing in mind that the study focuses on children aged between 0 and 8 years old, this could be interpreted as an indicator of the game developers’ poor understanding of the target group. Scenarios and elements that could only be recognised by children over 12 years old were also observed (10.5%).

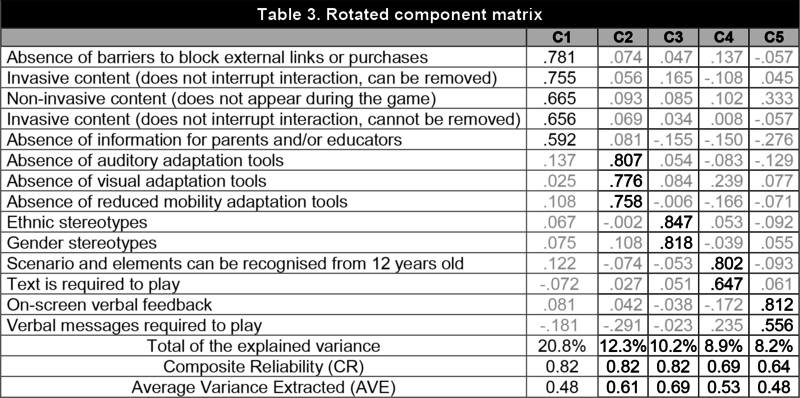

Reduction of dimensions

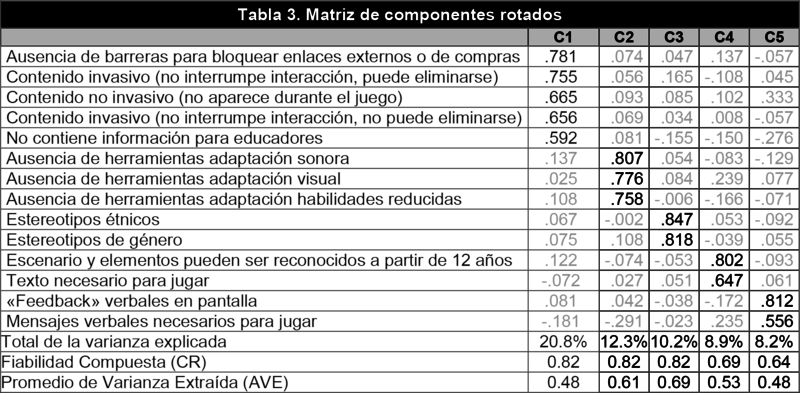

The PCA included variables associated with the idea of protection (Table 3), with the exception of one variable present in very few cases (“Invasive advertisements or message that interrupt the interaction”, n=7). The descriptive variables were not considered, because in themselves they do not constitute a problem of accessibility or safety for underage users. As already mentioned, the variables used in the PCA are dichotomous, their presence (1) or absence (0) being recorded during observation. The PCA allowed us to extract five components with values over the Kaiser criterion of 1. The five components together explained 60.4% of the variance. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure for sampling adequacy is 0.663, above the commonly recommended value of 0.6 (Kaiser & Rice, 1974), and Bartlett’s sphericity test is significant, x2 (91)=488.758, p<.001, which indicates that the correlations between the variables are high enough to justify the PCA.

|

|

The reliability of the constructs was measured with the composite reliability index (CR) (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988) and the average variance extracted (AVE) (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The values for each of the components extracted are summarised in the last two rows of Table 3. Both indices are above or approaching their respective cut-off values (CR>.60 and AVE>.50) for all five components. A cut-off value of λ=0.5 was established in order to make a decision about the number of variables to retain for each component. All the variables contained in the five components showed positive factorial loadings (in other words, the variables showed positive correlation with the respective latent component).

The first component, the “Security dimension”, accounts for 20.8% of the total variance and brings together items associated with insufficient prevision of protection mechanisms on one hand, and the existence of external interference, on the other. The absence of barriers to block external links or purchases is the aspect that contributes most to the first component in terms of factorial load (λ=0.781), followed by the presence of invasive advertisements or messages that, although they do not interrupt the action, may represent a negative interference, especially considering the age of the users. These invasive advertisements and/or messages have different characteristics, as they may sometimes be removed by the user (λ=0.755), whilst others do not appear during the game (λ=0.665) or simply cannot be removed (λ=0.656). Lastly, this component encompasses an aspect related to the absence of information for parents/educators (λ=0.592).

The second component accounts for 12.3% of the total variance. It was labelled “Adaptation tools” and identifies variables associated with the presence (or in this case lack of) strategies and mechanisms that favour inclusive use of the app. Specifically, the second component establishes a connection between three aspects: the absence of auditory adaptation tools (λ=0.807), visual adaptation tools (λ=0.776), and reduced physical and motor skills adaptation tools (λ=0.758). The third component (“Exposure to stereotypes”) accounts for 10.2% of the total variance. In this case, reference is made to ethnic stereotypes (λ=0.847) or gender stereotypes (λ=0.818).

The fourth and fifth components account for 8.9% and 8.2% of the total variance and are “Prior knowledge” and “Verbal component”, respectively. Both identify issues with adequacy. The first makes special reference to textual barriers –text is required to play (λ=0.647)– associated with the user’s ability to recognise the scenario and elements from 12 years old onwards (λ=0.802). Verbal barriers themselves are identified in component five: either the feedback is verbal on the game screen (λ=0.812) or verbal messages are necessary to play (λ=0.556).

In sum, the outputs derived from the PCA suggest that in the case under analysis focusing on apps in the Catalan language or developed in Catalonia, the traditional definition of protection (identified by the first component) contributes to 34.4% of the total variance explained (20.8/60.4*100). On the other hand, roughly two thirds of the variance explained (the remaining 65.6%) is accountable to an idea of child protection encompassing aspects related to accessibility (adaptation tools, users’ prior knowledge and auditory skills) and inclusiveness (absence of stereotypes).

Discussion and conclusions

The spread of digital technologies, the growing use of mobile devices in childhood and their progressive introduction into the classroom, implies a challenge for teachers, new knowledge and digital skills. Child protection in the digital environment is a complex issue that should be approached in a more comprehensive way than it is at present. In this sense, children's right to participation and accessibility from early childhood justifies our proposal for a more critical and ethical definition of protection; one that is not limited to preventing threats but that takes into account other aspects such as universal design and the accessibility of apps for young children.

The results suggest an invitation to teachers and educators in general to consider at least 5 aspects related to the design and development of educational digital tools (in this case, apps) that contribute to this updated definition of protection:

1) App mechanisms and strategies that could help to increase “safety” in its most traditional conceptualization and that include:

- Barriers to connecting to the internet and the absence of external interference accountable for the risks associated with being online (contact with strangers and the violation of privacy, and the use of geolocation).

- Information provided by the app (or not provided in 63.5% of the sample analysed) and aimed at parents and educators should ideally inform them of the game’s educational and recreational potential and warn of any potential risks. This information would empower educators as well as increasing their feelings of safety thanks to their perception of being able to control the risk factors.

2) Exposure and access to unsuitable or harmful content within the app itself has an undesirable effect in the mid and long term. None of the content “screened” by current age classification systems used for apps for children was observed during the analysis (explicit scenes involving sex, drugs, violence, etc). This notwithstanding, rather than stressing the ability of the PEGI system to classify apps for underage users, these results reveal its limitations in detecting other risks users may be exposed to (discrimination, exclusion, etc.), such as “exposure to stereotypes” (Component 3) relating to both gender and ethnicity;

3) Integration of visual, auditory and reduced physical or motor skills “adaptation tools” (Component 2) which protect the right to accessibility and participation for all children, within the framework of universal design and inclusive education;

4) Adaptation of the interactive content and design for the target group, considering children’s “prior knowledge” (Component 4). Despite the fact that the suitable age is often specified (as is the case with board games), the industry tendency to treat child users as a single undifferentiated target group is criticised. Reading and writing skills being essential to be able to play the game, an element found in the vast majority of the sample, is considered an accessibility issue (especially bearing in mind the audiovisual potential of interactive games);

5) Finally, the verbal component of the app should be considered (Component 5). This aspect ends up being a hindrance for children with normal development (who are learning to speak and/or are not familiar with the language), or those with special educational needs (deafness or hypoacusia, auditory memory and processing disabilities, ADHD and other learning difficulties), as in many apps it is the only way to access information.

Our proposal aims to contribute to the debate on the digital skills of teachers, but without suggesting that the set of characteristics observed is exhaustive. In addition, there were some limitations that affected the research; in terms of the instrument, it was not possible to measure its external validity as it was created specifically for the study. Additionally, from a methodology perspective, the single context and limited size of the sample prevent us from generalizing the results across the thousands of apps on the market for children under 8 years old. These limitations open up possibilities for future research to test this proposal in other contexts, with the objective of establishing guidelines to critically select resources that can guarantee children’s safety and ensure their right to participation.

Introducing digital competences into pedagogical practices in the classroom is not only up to teachers, but implies a structural change within educational institutions (Suárez-Guerrero, Lloret-Catalá & Mengual-Andrés, 2016; Howard, Yang, Ma, Maton, & Rennie, 2018). However, empowering teachers would at least produce a set of spill-over effects on students and the educational community at large. Becoming familiar with the different stages of designing, planning and implementing the use of digital technology is one of the priorities addressed by the “European framework for the digital competence of educators” (Redecker, 2017), with particular emphasis on an educational context in which, in the near future, teachers would not just select but would actually develop digital tools. To sum up, protecting children from an ethical and inclusive perspective means providing them with critical knowledge from pre-school onwards, to help them become fully integrated in the digital world.

References

- Asociación Española de Videojuegos (Ed.). 2013. , ed. de la industria del videojuego&author=&publication_year= Anuario de la industria del videojuego. Madrid: AEVI.

- Assembly of the United Nations (Ed.). 1989.Convention on the Rights of the Child. UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- Assembly of the United Nations (Ed.). 2006.Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [A/RES/61/106]

- BagozziR.P., YiY., . 1988.the evaluation of structural equation models&author=Bagozzi&publication_year= On the evaluation of structural equation models.Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 16(1):74-94

- BinDhimN., TrevenaL., . 2015.smartphone apps: Regulations, safety, privacy and quality&author=BinDhim&publication_year= Health-related smartphone apps: Regulations, safety, privacy and quality.BMJ Innovations 1(2):43-45

- BruckmanA., BandlowA., . 2002.Human-computer interaction for kids. In: BruckmanA., BandlowA., ForteA., eds. human-computer interaction handbook&author=Bruckman&publication_year= The human-computer interaction handbook. New Jersey, USA: Erlbaum Associates Inc. 428-440

- CusackS., . 2013.Gender stereotyping as a Human Rights violation: Research report. Prepared for the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- CreswellJ.W., . 2008.Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- De-HaanJ., Van-der-HofS., BekkersW., PijpersR., . 2013.Self-regulation. In: , ed. a better Internet for Children&author=&publication_year= Towards a better Internet for Children.111-129

- Desarrollo Español de Videojuegos (Ed.). 2016.Llibre blanc de la indústria catalana del videojoc 2016.

- European Commission (Ed.). 2006.Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 (2006/952/EC) on the protection of minors and human dignity and on the right of reply in relation to the competitiveness of the European audiovisual and on-line information services industry.

- European Commission (Ed.). 2012.Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: European Strategy for a better Internet for Children. COM(2012)

- 2015.Survey and Data Gathering to support the impact assessment of a possible new legislative proposal concerning. In: CommissionEuropean, ed. 2010/13/EU (AVMSD) and in particular the provisions on the protection of minors, Final Report&author=Commission&publication_year= Directive 2010/13/EU (AVMSD) and in particular the provisions on the protection of minors, Final Report. 2015

- FeliniD., . 2015.today’s video game rating systems: A critical approach to PEGI and ESRB, and proposed improvements&author=Felini&publication_year= Beyond today’s video game rating systems: A critical approach to PEGI and ESRB, and proposed improvements.Games and Culture 10(1):106-122

- FlewittR., MesserD., KucirkovaN., . 2015.directions for early literacy in a digital age: The iPad&author=Flewitt&publication_year= New directions for early literacy in a digital age: The iPad.Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 15(3):289-310

- FornellC., LarckerD.F., . 1981.structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error&author=Fornell&publication_year= Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error.Journal of Marketing Research 18(1):39-50

- GayV., LeijdekkersP., . 2014.of emotion-aware mobile apps for autistic children&author=Gay&publication_year= Design of emotion-aware mobile apps for autistic children.Health and Technology 4(1):21-26

- HerodotouC., . 2017.children and tablets: A systematic review of effects on learning and development&author=Herodotou&publication_year= Young children and tablets: A systematic review of effects on learning and development.Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 34(1):1-9

- HoltR.J., MooreA.M., BeckettA.E., . 2014.Together through play: Facilitating inclusive play through participatory design. In Inclusive designing: Joining usability, accessibility, and inclusion. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. 245-255

- HourcadeJ.P., WilliamsS.R., MillerE.A., HuebnerK.E., LiangL.J., . 2013.of tablet apps to encourage social interaction in children with autism spectrum disorders&author=Hourcade&publication_year= Evaluation of tablet apps to encourage social interaction in children with autism spectrum disorders. In: , ed. of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems&author=&publication_year= Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.3197-3206

- HowardS.K., YangJ., MaJ., MatonK., RennieE., . 2018.clusters: Exploring patterns of multiple app use in primary learning contexts&author=Howard&publication_year= App clusters: Exploring patterns of multiple app use in primary learning contexts.Computers & Education 127:154-164

- KaiserH.F., RiceJ., . 1974.jiffy, mark IV&author=Kaiser&publication_year= Little jiffy, mark IV.Educational and Psychological Measurement 34(1):111-117

- KirkorianH.L., PempekT.A., . 2013.Toddlers and touch screens: Potential for early learning?Zero to Three 33(4):32-37

- LandisJ.R., KochG.G., . 1997.measurement of observer agreement for categorical data&author=Landis&publication_year= The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data.Biometrics 33(1):159-174

- LievensE., . 2015.protection of&author=Lievens&publication_year= Children, protection of. In: M.Robin,, P.Hwa-Ang,, eds. International Encyclopedia of Digital Communication and Society&author=M.&publication_year= The International Encyclopedia of Digital Communication and Society.1-5

- LivingstoneS., . 2014.EU Kids Online. Final report to the EC Safer Internet Programme from the EU Kids Online network 2011-2014. Contract number: SIP-2010-TN-4201001.

- LivingstoneS., MascheroniG., StaksrudE., . 2015.Developing a framework for researching children’s online risks and opportunities in Europe.

- Nielsen Group (Ed.). 2012.American families see tablets as playmate, teacher, and babysitter.

- OdomS.L., DiamondK.E., . 1998.Inclusion of young children with special needs in early childhood education: The research base.Early Childhood Research Quarterly 13(1):3-25

- OFCom. Office of Communications (Ed.). 2017.Children and parents: Media use and attitudes report publication.

- Pan European Game Information (Ed.). 2013.PEGI Annual Report.

- PorterJ., . 2018.Aladdin's cave: Developing an app for children with Down syndrome&author=Porter&publication_year= Entering Aladdin's cave: Developing an app for children with Down syndrome.Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 34(4):429-439

- RideoutV., . 2017.The common sense census: Media use by kids age zero to eight 2017.

- RedeckerC., . 2017.European framework for the digital competence of educators. DigCompEdu. JCR Science for Policy Report.

- ShulerC., . 2009. , ed. A content analysis of the iTunes App Store Education Section&author=&publication_year= iLearn; A content analysis of the iTunes App Store Education Section. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. 2009

- SobelK., O'LearyK., KientzJ.A., . 2015.children's opportunities with inclusive play: Considerations for interactive technology design&author=Sobel&publication_year= Maximizing children's opportunities with inclusive play: Considerations for interactive technology design. In: , ed. of the 14th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children&author=&publication_year= Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children.ACM. 39-48

- SolerI.R., López-SánchezC., LacaveT.T., . 2018.de riesgo online en jóvenes y su efecto en el comportamiento digital. [Online risk perception in young people and its effects on digital behaviour&author=Soler&publication_year= Percepción de riesgo online en jóvenes y su efecto en el comportamiento digital. [Online risk perception in young people and its effects on digital behaviour]]Comunicar 56:71-79

- Suárez-GuerreroC., Lloret-CataláC., Mengual-AndrésS., . 2016.docente sobre la transformación digital del aula a través de tabletas: un estudio en el contexto español. [Teachers' perceptions of the digital transformation of the classroom through the use of tablets: A study in Spain&author=Suárez-Guerrero&publication_year= Percepción docente sobre la transformación digital del aula a través de tabletas: un estudio en el contexto español. [Teachers' perceptions of the digital transformation of the classroom through the use of tablets: A study in Spain]]Comunicar 49:81-89

- TrosethG.L., RussoC.E., StrouseG.A., . 2016.next for research on young children’s interactive media?&author=Troseth&publication_year= What’s next for research on young children’s interactive media?Journal of Children and Media 10(1):54-62

- YussofR.L., AnuuarW.S.W.M., RiasR.M., AbasH., AriffinA., . 2016.An approach in teaching reading for down syndrome children.International Journal of Information and Education Technology 6(11):909

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El uso mediado de la tecnología fomenta el aprendizaje desde la infancia y representa un potencial recurso para la educación inclusiva. Al mismo tiempo, la creciente exposición a contenidos digitales interactivos, a menudo conectados a la red, conlleva una serie de riesgos para los niños. A las estrategias actualmente empleadas para protegerlos, que se limitan a reducir su exposición a contenidos perjudiciales, parece subyacer una definición de protección inadecuada. Esta investigación propone que se amplíe esta definición. A través de una observación sistemática de 200 apps para menores de ocho años en el ámbito catalán y un análisis de componentes principales, se propone una definición multidimensional de protección que no se limita a detallar los riesgos potenciales, sino que también considera aspectos relacionados con el potencial educativo e inclusivo de los recursos digitales. Se sugieren cinco factores a considerar para seleccionar estos recursos y contribuir a la competencia digital de docentes y alumnos. El primer factor concierne al uso de mecanismos de protección y la existencia de interferencias externas; el segundo factor indica la presencia de herramientas de adaptación; la exposición a estereotipos corresponde al tercer factor y los últimos dos consideran los conocimientos previos requeridos y el componente verbal de las apps. Finalmente se discute el alcance de la definición propuesta y sus limitaciones para guiar análisis futuros.

ABSTRACT

The mediated use of technology fosters learning from early childhood and is a potential resource for inclusive education. Nevertheless, the huge range of options and exposure to interactive digital content, which is often online, also implies a series of risks. The definition of protection underlying the current strategies to protect children is inadequate as it only extends to reducing children's exposure to harmful content. This study proposes the expansion of this definition. Through systematic observation of 200 apps within the Catalan sphere for children under 8 years of age and principal component analysis, the results support a multidimensional conceptualisation of protection which, instead of being restricted to the potential risks, also considers aspects related to the educational and inclusive potential of digital resources. Five factors are suggested in order to select these resources and contribute to the digital competence of teachers and students. The first factor concerns the use of protection mechanisms and the existence of external interference, the second factor indicates the presence of adaptation tools; the exposure to stereotypes corresponds to the third factor and the last two consider the previous knowledge required and the verbal component of the apps. Finally, the scope of the suggested definition and its limitations as a guide for future analysis will be discussed.

Keywords

Niños, tecnología educativa, apps, seguridad, educación inclusiva, análisis de contenido, protección de menores, ciberseguridad, competencia digital

Keywords

Children, educational technology, apps, safety, inclusive education, content analysis, protection of minors, cybersafety, digital competence

Introducción

Los datos del informe «EU Kids online» (Livingstone, 2014) y de Nielsen Group (2012) sobre la adopción de las tecnologías en Europa muestran como a principios de la década actual, los niños/as se conectaban a Internet a diario a través de diversos dispositivos (especialmente móviles), y cada vez a una edad más temprana. Esta tendencia continúa. Según el informe publicado por OFCom (2017), en Reino Unido el 65% de los niños y niñas de tres a cuatro años y el 75% de niños/as entre cinco y siete años utilizan asiduamente tabletas, así como «smartphones» (el 23% del grupo de tres a cuatro años y el 47% de cinco a siete). En esta misma dirección apunta el último «Common Sense Census» (Rideout, 2017).

Del mismo modo, la oferta de apps para niños en edad preescolar ha aumentado considerablemente (solamente en Apple Store existen más de 80.000 apps para público infantil), reflejando la creciente demanda por parte de educadores y familias de recursos digitales que ayuden a los niños a aprender, jugar y entretenerse (Troseth, Russo, & Strouse, 2016). La presente investigación se centra en la porción del mercado de las apps ocupada por las industrias de juegos digitales catalanas que desde 2012 han experimentado un crecimiento exponencial, como indica el «Llibre blanc de la indústria catalana del videojoc» (Desarrollo Español de Videojuegos, 2016).

Una de las cuestiones más debatidas en la literatura concierne al impacto que los juegos digitales puedan tener sobre los procesos de aprendizaje, en general, y el aprendizaje de los niños, en particular. En efecto, si por un lado el potencial de aprendizaje de los recursos digitales interactivos es ampliamente respaldado (Herodotou, 2017; Flewitt, Messer, & Kucirkova, 2015; Kirkorian & Pempek, 2013), por el otro, preocupa la exposición de los niños a contenidos online que puedan poner en riesgo su seguridad. En este sentido, la Comisión Europea (2006) ha tipificado los principales riesgos para los menores de edad en tres macro-categorías: riesgos asociados al contacto con desconocidos («cyber-bullying», «grooming» o «sexting»), riesgos asociados a la exposición y acceso a diferentes tipos de contenidos inapropiados o perjudiciales (como pornografía y violencia), y riesgos asociados a la privacidad (por ejemplo, servicios que utilizan geo-localización). De manera similar, Lievens (2015) apunta a la existencia de tres tipos de riesgos online para los niños: los riesgos de contenido, en los que el niño es un receptor; los riesgos de contacto, en los que es un participante; y los riesgos de conducta, donde el niño es un actor que incumple determinadas normas de comportamiento (como realizar compras o descargar contenidos ilegales). Este tipo de clasificaciones advierte tanto de la complejidad del fenómeno como de su evolución respecto a los peligros asociados a la infancia cuando no se encuentra conectada a la red, lo que implica encontrar nuevas medidas de prevención y protección.

Con este propósito, el informe presentado por la Comisión Europea (Redecker, 2017), que establece un «Marco europeo para la competencia digital de los docentes», evidencia que las medidas de protección no pueden limitarse a contemplar barreras externas (por ejemplo, a través de filtros que impidan el acceso a contenidos potencialmente perjudiciales), sino que la prioridad es empoderar a los usuarios para que dispongan de recursos para identificar y gestionar los riesgos de forma autónoma. Las conclusiones propuestas por Livingstone, Mascheroni y Staksrud (2015) muestran que la mediación de los educadores es un primer factor determinante para limitar los potenciales riesgos que conlleva el uso de tecnología online. Sin embargo, la capacidad de seleccionar dispositivos y contenidos más apropiados «no puede darse por sentada» (Felini, 2015: 114).

Hay un acuerdo generalizado en admitir que los educadores necesitan algún tipo de soporte (información o «training») para hacer esta selección y entender los riesgos asociados al uso de dispositivos móviles (Comisión Europea, 2015; De Haan, Van-der-Hof, Bekkers, & Pijpers, 2013). Aunque para ello es necesario plantear un cambio estructural que redefina las competencias de los educadores en el marco de un proceso de innovación pedagógica (Howard, Yang, Ma, Maton, & Rennie, 2018; Redecker, 2017; Suárez-Guerrero, Lloret-Catalá, & Mengual-Andrés, 2016).

Por otra parte, existen iniciativas como la de la «International Age Rating Coalition» (IARC), que intenta ayudar a padres y educadores a seleccionar los recursos digitales mediante una clasificación de contenidos por edades. IARC tiene una difusión global y se emplea para clasificar todas las apps en el «Windows Store» para PC, tabletas y «smartphones». Su uso tiene la ventaja de permitir identificar la edad del público empleando una clasificación ad hoc para cada país. Por ejemplo, en Europa se emplea el sistema «Pan European Game Information» (PEGI), ya empleado para clasificar por edades los contenidos audiovisuales y videojuegos. PEGI clasifica los contenidos en cinco franjas de edad: 3, 7, 12, 16 y 18.

Para ello, utiliza una definición residual, esto es, el producto se considera apto para todas las edades (PEGI 3) o para niños desde los siete años (PEGI 7) si no incluye los siguientes elementos «perturbadores»: violencia, lenguaje soez, miedo/horror, referencias explícitas a drogas y/o sexo, discriminación, juegos de azar y apuestas, juego en línea con otras personas. Evidentemente, los desarrolladores de juegos para menores de ocho años no suelen incluir escenas explícitas de violencia ni otros de estos elementos. Probablemente por este motivo, como indica el informe del PEGI (2013), el 58% de un total de 25.387 contenidos clasificados con su sistema desde 2003 a 2015 se etiquetan como PEGI 3 o PEGI 7, es decir, aptos para un público infantil.

Las connotaciones asociadas a la definición de protección actual circunscriben la tarea de la prevención a la reducción de los riesgos, para evitar la exposición del niño a contenidos impactantes, situando al niño-jugador como mero objeto de protección.

De forma parecida, el «Anuario de la industria del videojuego» (AEVI, 2013) destaca que más de la mitad de los 20 videojuegos más vendidos también se clasificaron aptos para PEGI 3 (todos los públicos) o PEGI 7. Estos datos subrayan la escasa capacidad de la actual definición de protección para captar los riesgos a los que se enfrentan los niños, como por ejemplo el riesgo de exclusión o la exposición a contenidos más normalizados, pero no por esto menos perjudiciales (como la presencia de estereotipos étnicos o de género).

Las limitaciones de los intentos de regulación actuales derivan de una definición de «protección» deficitaria por dos razones. Primero, porque es una definición meramente residual (es decir, que los contenidos se consideran aptos en ausencia de determinadas amenazas); y segundo, porque no presta atención a la adecuación de las características de las apps a su «target», vulnerando el derecho de los niños a la participación y a la accesibilidad a las Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicación (TIC), tipificado por las Naciones Unidas en el marco de la Convención sobre los Derechos del Niño (Assembly of the United Nations, 1989) y la Convención Internacional sobre los Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad de 2006. Como ejemplo, se ha demostrado que los juegos digitales pueden incrementar habilidades sociales (el autoconcepto, la autoeficacia, el reconocimiento de las emociones, etc.) y comunicativas de niños con trastorno del espectro autista (ASD) (Hourcade & al., 2013; Gay & Leijdekkers, 2014) y con síndrome de Down (Porter, 2018; Yussof & al., 2016). Sin embargo, para aprovechar estos potenciales beneficios, el profesorado necesita conocer qué recursos digitales emplear con los alumnos y cómo «protegerlos» durante un proceso de aprendizaje potenciado por la tecnología (Soler, López-Sánchez, & Lacave, 2018). El primer paso es consensuar una definición de protección que depende en última instancia del papel que se atribuye al menor. Desde la perspectiva de los autores, las connotaciones asociadas a la definición de protección actual circunscriben la tarea de la prevención a la reducción de los riesgos, para evitar la exposición del niño a contenidos impactantes, situando al niño-jugador como mero objeto de protección. Contrariamente, iniciativas como la denominada «Better Internet for Kids» promovida por la Comisión Europea (2012) ponen particular énfasis en la necesidad de promover actividades de empoderamiento de los niños en edades tempranas para su integración en el mundo digital. En este proceso el profesorado tiene un papel determinante.

Considerando estas limitaciones, se defiende una conceptualización de protección de los menores más amplia, ajustada a las indicaciones de BinDhim y Trevena (2015), que considere la ausencia de amenazas además de la accesibilidad. En este sentido, el paradigma del Diseño Universal de las TIC en el que se enmarca esta propuesta, contempla un diseño accesible y adaptable a todos los niños/as con desarrollo típico y con necesidades educativas especiales (Holt, Moore, & Beckett, 2014; Sobel, O’Leary, & Kientz, 2015; Odom & Diamond, 1998). Este trabajo se propone ofrecer una nueva perspectiva más crítica y ética del concepto de protección de los menores. Para poder explorar la consistencia teórico-empírica de esta definición y establecer cuáles son los aspectos a tener en cuenta por el profesorado a la hora de seleccionar los recursos educativos digitales, se ha llevado a cabo un análisis de contenido y un análisis de componentes principales, cuyos detalles se explican a continuación.

Material y métodos

Muestra y características de las apps analizadas

Se seleccionaron apps para menores de ocho años (clasificadas como PEGI 3 y PEGI 7 y/o como +4 en el Apple Store), para subsanar la escasez de estudios enfocados a la primera infancia y atender a la necesidad de tener en cuenta la incesante evolución del desarrollo infantil durante los primeros años de vida. El muestreo de apps se llevó a cabo utilizando un buscador (Google Search), dos bases de datos (Apple Store y Google Play Store) y empleando dos criterios de inclusión: 1) Que la app se dirigiera a niños de 0 hasta los siete años de edad, según la explícita indicación del desarrollador o, a falta de esta información, de los distribuidores; 2) Que la productora de la app tuviera una sede en Cataluña y/o que el idioma empleado en al menos una versión de la app fuera el catalán (ver apoyos). Se excluyeron las apps de una misma productora que presentaran el mismo motor de programación y visual, aunque contenidos diferentes (por ejemplo, colorear princesas, colorear coches, colorear animales). Ateniéndose a estos criterios, la muestra final incluyó 200 apps en catalán o desarrolladas en Cataluña destinadas a niños menores de ocho años. Todas las apps analizadas se lanzaron al mercado entre 2011 y 2017 por iniciativa de 87 desarrolladores diferentes. Debido al contexto en el que se centra la investigación, el 80% de la muestra ha sido desarrollada en España (149 en Cataluña y 11 en el resto del país). El 47% funciona en más de un sistema operativo y el 34,5% (n=69) son gratuitas. Entre las de pago, 36 cuestan menos de 3€, 15 entre 3€ y 10€ y 3 entre 10€ y 30€.

Enfoque analítico

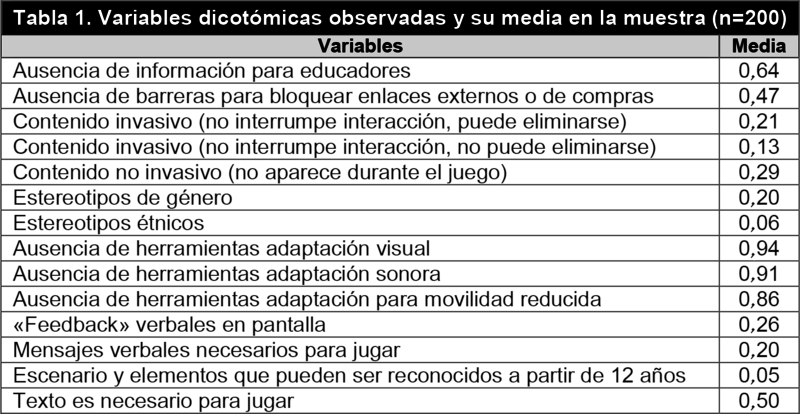

La metodología empleada en la investigación es el análisis de contenido mediante observación estructurada. Esta metodología se enmarca en un paradigma de investigación post-positivista (Creswell, 2008) y suele emplearse en el estudio de las aplicaciones digitales e interactivas para niños (Amy, Alisa, & Andrea, 2002; Bruckman & Bandlow, 2002). La ficha de observación empleada para realizar el análisis de contenido estaba compuesta por un total de veinte variables, entre las que seis eran descriptivas dicotómicas y destinadas a identificar algunas características básicas de las apps, como por ejemplo: a) Si se dirigen a un colectivo con necesidades educativas especiales; b) Si adaptan sus respuestas al usuario; c) Si incluyen la posibilidad de seleccionar diferentes niveles de dificultad; d) Si es posible utilizarlas offline; e) Entre más jugadores; y, por último, f) Si emplean sistemas de geo-localización. En la Tabla 1 se muestran las demás variables, también dicotómicas (presencia=1/ausencia=0), utilizadas para la operacionalización del constructo «protección del menor», considerando el uso seguro del contenido digital y su accesibilidad.

|

|

La conceptualización de las variables en la tabla anterior es generalmente auto-explicativa (presencia o ausencia de determinadas características técnicas o de diseño). Por otra parte, se definieron los estereotipos étnicos como el conjunto de las cualidades o conductas que se atribuyen de forma generalizada a una cultura o a un individuo en función de su procedencia. Según la definición de Cusack (2013: 17), un estereotipo de género es la «práctica de atribuir a una mujer o un hombre atributos, características o roles específicos sobre la única base de su pertenencia al grupo social de mujeres u hombres».

En relación con el procedimiento, se realizó la observación de las 200 apps que componen la muestra durante el último trimestre del 2017, empleando un iPad o una tableta Samsung Galaxy. El protocolo de observación de cada app implicaba una interacción inicial de 10 minutos con el juego y, a continuación, se iniciaba la codificación de la información mediante una ficha de observación en Excel. Durante el proceso de codificación, se podía volver a la app en cualquier momento sin límites de tiempo hasta completar la ficha de análisis.

Nueve expertos, seis mujeres y tres hombres, validaron la ficha de observación (validez de contenido por juicios de expertos): cinco profesores universitarios doctores (tres del área de tecnología de la educación y dos de educación especial e inclusiva); una profesora universitaria titular en educación y madre de dos niños menores de ocho años, uno de ellos con síndrome de Down; un desarrollador de apps infantiles; un profesional de la comunicación y padre de tres niños menores de ocho años; y una profesora de infantil con una vasta experiencia en escuelas inclusivas y niños en edad preescolar con diversidad funcional.

A continuación, se realizó una prueba piloto de forma independiente observando las mismas tres apps, que no se incluyeron en la muestra final. En la Tabla 2 se presentan los resultados de la medida de fiabilidad entre evaluadores para las tres apps, que muestran un grado elevado de acuerdo (Landis & Koch, 1977).

|

|

Se optó por un análisis de las frecuencias observadas y, sucesivamente, se ejecutó el análisis de componentes principales (de aquí en adelante ACP) para observar los autovalores ('eigenvalues') de cada componente. El desarrollo del análisis de componentes principales se realizó aplicando el método de rotación ortogonal Varimax. El análisis estadístico descriptivo e inferencial se realizó utilizando el software IBM SPSS Statistics.

Resultados

Descripción de la muestra de 200 apps

En cuanto a la edad de los destinatarios es destacable que, en 126 casos, el desarrollador no indica la edad del público al que se destina la app, y en otros 9 se indica que es para todas las edades. En otras palabras, en el 67,5% de los casos no existen indicaciones precisas por parte de los desarrolladores respecto a la edad del «target».

Se observaron 163 apps que se pueden usar offline (81,5%), 27 que se pueden usar offline sin tener acceso a todo el contenido (13,5%) y 10 que se pueden utilizar solo conectados a Internet (5%). Relacionado con la privacidad, se ha considerado la presencia y uso de sistemas de geolocalización, que sin embargo se registró en tan solo dos apps. Para estimular el juego colaborativo e inclusivo entre pares, las apps deberían permitir el juego entre más de un usuario. No obstante, 177 (88,5%) están pensadas para un único usuario.

Tan solo se dan 13 casos en los que las apps se orientan a algún colectivo en particular de forma explícita (niños con trastorno del espectro autista TEA, síndrome de Down, TDH, TDAH u otros trastornos del aprendizaje). En 9 casos (3 de ellos en apps para niños con TEA) las apps eran adaptativas (4,5%), es decir, la respuesta del usuario determina la dificultad del juego. Por otro lado, en 73 existe la posibilidad de escoger diferentes niveles de dificultad (36,5%).

Adecuación con los supuestos de protección y seguridad para menores de ocho años

Se realizó un análisis descriptivo de las características de las apps siguiendo una definición de protección que abarca tanto la idea de seguridad stricto sensu, como los elementos relacionados con el acceso al diseño y contenido de las apps infantiles. El 35% de la muestra proporciona información para los educadores en la misma app y otro 1,5% la ofrece a través de enlace a web externa, frente al 63,5% que no brinda ningún tipo de información para los adultos de referencia.

Existen barreras para bloquear el acceso de los menores a enlaces externos o compras durante el juego en 57 apps (28,5%). Considerando que en otras 49 no son necesarias (24,5%), el 47% de la muestra no cumple con el requisito de impedir el acceso (involuntario o consciente) a enlaces externos o compras por parte de los niños/as. Asimismo, solo el 40,5% de la muestra está libre de contenido invasivo (interferencias externas), mientras que la mayoría presenta al menos uno de los siguientes elementos:

- Anuncios o mensajes invasivos que interrumpen la interacción (n=7; 3,5% de la muestra).

- Anuncios o mensajes invasivos que, si bien no interrumpan la interacción, no pueden eliminarse (n=25; 12,5%).

- Anuncios o mensajes invasivos que no interrumpen la interacción, y pueden eliminarse, por ejemplo, haciendo clic en el icono «x» para cerrar pantalla (n=41; 20,5%).

- Anuncios o mensajes no invasivos que no aparecen durante el juego (n=58; 29%).

Como se preveía, no se observó ningún contenido contemplado en PEGI, aunque sí se muestran estereotipos de género en 39 casos (19,5%) y estereotipos étnicos en 11 (5,5%).

En cuanto a los aspectos relativos a la accesibilidad, se consideraron tres dimensiones distintas: la oferta de estrategias o mecanismos de adaptación visual, sonora y motora. La presencia de herramientas de adaptación visual se encuentra en tan solo 13 apps (6,5%). Entre ellas, tres permiten identificar, invertir o adaptar colores, siete cambiar de tamaño los textos, seis cambiar el tamaño de pantallas o elementos y dos tienen «voice-over». Datos similares se registraron con referencia a las herramientas de adaptación visual (solo 13 de los casos analizados disponen de ellas) y sonora (19). Por último, la presencia de herramientas de adaptación para habilidades físicas o motoras reducidas se da en 28 casos (14%).

Por tanto, la muestra presenta graves déficits en cuanto a accesibilidad, sobre todo si se considera que ninguna app analizada permite adaptar el teclado ni utilizar dispositivos externos para movilidad reducida. Tan solo dos reconocen el trazo en pantalla y otras dos permiten utilizar gestos diversos como alternativa para interactuar con la pantalla y lograr el objetivo del juego (ej.: tocar en lugar de arrastrar). Aproximadamente la mitad de la muestra (109 apps, 54,5%) no incluye mensajes verbales. En 40 apps (20%) los mensajes verbales son necesarios para jugar, lo que supone un problema a nivel de adaptación tanto cognitiva como comunicativa para algunos colectivos con necesidades educativas especiales. Por otro lado, en la pantalla de juego los «feedback» son verbales en el 25,5% de los casos.

En relación con la adecuación al público, se ha identificado que el texto es necesario para jugar en 99 apps (49,5%). Si se estiman exclusivamente las 70 apps dirigidas explícitamente a niños de 6 años o más pequeños (en edad preescolar no suelen haber desarrollado habilidades de lectoescritura), en más de la mitad (n=37; 53%) el texto es necesario para jugar. Considerando que el estudio se centra en apps para niños de 0 a 8 años, este es un indicio del escaso conocimiento del «target» por parte de los desarrolladores. Aunque con menos frecuencia, se observó también la presencia de escenarios y elementos que pueden ser reconocidos por niños solamente a partir de 12 años (10,5%).

Reducción de dimensiones

El ACP incluyó las variables asociadas al concepto de protección (Tabla 3), a excepción de una variable que presentaba un número de casos muy escaso («Anuncios o mensajes invasivos que interrumpen la interacción», n=7). No se consideraron las variables descriptivas porque en sí mismas no constituye un problema para la accesibilidad o seguridad del menor. Como se ha indicado, todas las variables utilizadas en el ACP son dicotómicas, registrando su presencia (1) o ausencia (0) durante la observación. El ACP permitió extraer cinco componentes con valores propios por encima del valor 1 fijado por el criterio de Kaiser. Los cinco componentes en su conjunto explican el 60,4% de la varianza total. La medida de la adecuación muestral de Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin es de 0.663, superior al valor comúnmente recomendado de 0.6 (Kaiser & Rice, 1974), y la prueba de esfericidad de Bartlett es significativa, x2 (91)=488.758, p<.001, lo que indica que las correlaciones entre las variables son lo suficientemente altas como para justificar el ACP.

|

|

La fiabilidad de los constructos se midió con el índice de fiabilidad compuesta (CR) (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988) y con el índice promedio de varianza extraída (AVE) (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), cuyos valores por cada uno de los componentes extraídos se resumen en las últimas dos filas de la Tabla 3. Ambos índices están por encima o aproximan sus respectivos valores de corte (CR>.60 y AVE>.50) para cada uno de los cinco componentes.

Se estableció un valor de corte de λ=0.5 para tomar una decisión respecto al número de variables a retener por cada componente. Todas las variables que integran los cinco componentes mostraron coeficientes factoriales positivos (es decir, las variables comparten una correlación positiva con el respectivo componente latente).

El primer componente, denominado «Desprotección», explica el 20,8% de la varianza total y reúne los ítems asociados con una insuficiente previsión de mecanismos de protección y la existencia de interferencias externas. La ausencia de barreras para bloquear enlaces externos o de compras es el aspecto que más aporta en términos de carga factorial al primer componente (λ=0.781), seguido por la presencia de anuncios o mensajes invasivos que, si bien no interrumpen la acción, pueden representar una injerencia negativa, especialmente considerando la edad del usuario. Estos anuncios y/o mensajes invasivos tienen características distintas: en ocasiones se pueden eliminar por parte del usuario (λ=0.755), mientras que en otras no aparecen durante el juego (λ=0.665) o no pueden eliminarse (λ=0.656). Por último, este componente engloba un aspecto relacionado con la ausencia de información para educadores (λ=0.592).

El segundo componente explica el 12,3% de la varianza total. Denominado «Herramientas de adaptación», identifica las variables asociadas a la presencia (o la falta) de estrategias y mecanismos que favorecen un uso inclusivo. En concreto, el segundo componente establece una conexión entre tres aspectos: la ausencia de herramientas de adaptación sonora (λ=0.807), visual (λ=0.776) y para habilidades físicas o motoras reducidas (λ=0.758).

El tercer componente («Exposición a estereotipos») explica el 10,2% de la varianza total. En este caso, se hace referencia a la presencia de estereotipos étnicos (λ=0.847) o de género (λ=0.818).

El cuarto y quinto componentes explican el 8,9% y el 8,2% de la varianza total. Denominados «Conocimientos previos» y «Componente verbal» respectivamente, ambos identifican problemas de adecuación. En el primer caso se hace especial referencia a barreras de carácter textual –el texto es necesario para jugar (λ=0.647)– que están asociadas con las potencialidades del usuario de poder reconocer el escenario y los elementos solo a partir de los 12 años (λ=0.802). Por su parte, en el componente cinco se identifican barreras verbales: en la pantalla de juego los «feedback» son verbales (λ=0.812) o los mensajes verbales son necesarios para jugar (λ=0.556). En conclusión, a raíz de los «outputs» de la ACP se puede afirmar que, en el caso en cuestión de apps en catalán o desarrolladas en Cataluña, la definición clásica de protección (sintetizada por el primer componente) contribuye al 34,4% de la varianza total explicada (20,8/60,4*100). Al mismo tiempo, aproximadamente dos tercios de la varianza explicada (el restante 65,6%) dependen de una idea de tutela del menor que abarca aspectos relacionados con la acessibilidad (herramientas de adaptación, conocimientos previos y capacidades auditivas de los usuarios) y la inclusividad (ausencia de estereotipos).

Discusión y conclusiones

La difusión de las tecnologías digitales, el creciente uso de los dispositivos móviles en la infancia y su progresiva integración en las aulas conllevan un reto para el profesorado, nuevos conocimientos y competencias digitales. La protección de los menores en entornos digitales es un tema complejo que debería abordarse de forma más amplia a la actual. En este sentido, el derecho de los niños a ver garantizadas la participación y accesibilidad desde la primera infancia justifica proponer una definición de protección más crítica y ética, que no se limite a considerar la ausencia de amenazas, sino que tenga en cuenta otros aspectos como el diseño universal y la accesibilidad de los recursos digitales educativos.

Los resultados presentados invitan al profesorado y los educadores en general, a considerar al menos cinco características de los recursos educativos digitales (en este caso apps) que contribuyen a esta definición de protección:

1) Los mecanismos y estrategias de la app que contribuyen a incrementar la seguridad «tout court» (Componente 1) y que incluyen:

- Barreras ante la conexión a la Red y ausencia de interferencias externas que responden a los riesgos asociados a la conexión a Internet (contacto con desconocidos y violación de la privacidad o datos, como el uso de geo-localización).

- La información que ofrece la app (o no ofrece, como en el 63,5% de la muestra analizada) sobre las potencialidades educativas y lúdicas del juego, e idealmente sobre los potenciales riesgos. Esta información fomenta el empoderamiento de los educadores, incrementando la percepción de poder ejercer un control sobre los factores que causan el riesgo.

2) La exposición y acceso a contenidos inapropiados o perjudiciales incluidos en la app que tienen un efecto indeseable a medio y largo plazo. Este estudio no encontró evidencia de contenidos «filtrados» a través de los actuales sistemas de clasificación por edad de las apps infantiles (escenas explícitas de sexo, droga, violencia, etc.). Este resultado, más que destacar la capacidad del sistema PEGI para filtrar aplicaciones para menores de 8 años con contenidos prejudiciales, subraya sus límites para detectar otros riesgos a los que se enfrentan los usuarios (discriminación, exclusión, etc.), como la «exposición a estereotipos» (Componente 3) de género y étnicos.

3) La integración de «herramientas de adaptación» (Componente 2) visual, sonora y para habilidades físicas o motoras reducidas, que proteja el derecho a la accesibilidad y la participación de todos los niños/as, en el marco de un diseño universal y para una educación inclusiva.

4) La adecuación del contenido y diseño interactivo a la edad, considerando los «conocimientos previos» de los niños/as (Componente 4). Aunque a menudo se especifica la edad de los destinatarios de una app (como en los juegos de mesa), la tendencia de la industria a considerar el «target» infantil como un conjunto indiferenciado de usuarios es un aspecto muy problemático. Se considera un problema de accesibilidad (especialmente por las potencialidades audiovisuales de los juegos interactivos) el requerimiento de la lectoescritura para poder jugar en la amplia mayoría de la muestra analizada.

5) Finalmente, es necesario considerar el componente verbal de la app (Componente 5). Este aspecto termina siendo un obstáculo para niños/as con desarrollo típico (que están aprendiendo a hablar y/o que no estén familiarizados con el idioma) o con necesidades educativas especiales (sordera o hipoacusia, discapacidad de la memoria, TDHA y otros problemas de aprendizaje), al ser la única vía de acceso a la información en muchas apps.

La propuesta quiere contribuir al debate sobre las competencias digitales del profesorado, sin pretensiones de que el conjunto de estas características sea exhaustivo. Se destacan además algunas limitaciones: no fue posible medir la validez externa del instrumento al ser creado expresamente para el estudio y, además, desde el punto de vista metodológico hay que considerar los límites del muestreo centrado en un único contexto y del tamaño de la muestra, que no permiten generalizar los resultados al conjunto de apps para menores de 8 años ofrecido por el mercado. Estas limitaciones abren el camino para futuras investigaciones que pongan a prueba la presente propuesta en contextos diferentes del catalán, con el objetivo de poder llegar a ofrecer pautas para elegir críticamente recursos que garanticen la protección del menor y su derecho a la participación.

La integración de las competencias digitales en las dinámicas pedagógicas del aula no solo depende de los profesores, sino que implica un cambio estructural de las instituciones educativas (Suárez-Guerrero, Lloret-Catalá, & Mengual-Andrés, 2016; Howard, Yang, Ma, Maton, & Rennie, 2018). Sin embargo, el empoderamiento del profesorado terminaría produciendo una serie de efectos «spill-over» sobre la comunidad de alumnos y la comunidad educativa en su conjunto. La familiarización con las diferentes etapas del diseño, planificación e implementación del uso de las tecnologías digitales es una de las prioridades del «European framework for the digital competence of educators» (Redecker, 2017), sobre todo en un contexto educativo en el que, en un futuro próximo, los profesores desarrollarán, además de seleccionar los recursos digitales. En conclusión, proteger al menor desde una perspectiva ética e inclusiva implica promocionar la formación crítica del alumnado desde la escuela infantil, para su integración en el mundo digital.

References

- Asociación Española de Videojuegos (Ed.). 2013. , ed. de la industria del videojuego&author=&publication_year= Anuario de la industria del videojuego. Madrid: AEVI.

- Assembly of the United Nations (Ed.). 1989.Convention on the Rights of the Child. UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- Assembly of the United Nations (Ed.). 2006.Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [A/RES/61/106]

- BagozziR.P., YiY., . 1988.the evaluation of structural equation models&author=Bagozzi&publication_year= On the evaluation of structural equation models.Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 16(1):74-94

- BinDhimN., TrevenaL., . 2015.smartphone apps: Regulations, safety, privacy and quality&author=BinDhim&publication_year= Health-related smartphone apps: Regulations, safety, privacy and quality.BMJ Innovations 1(2):43-45

- BruckmanA., BandlowA., . 2002.Human-computer interaction for kids. In: BruckmanA., BandlowA., ForteA., eds. human-computer interaction handbook&author=Bruckman&publication_year= The human-computer interaction handbook. New Jersey, USA: Erlbaum Associates Inc. 428-440

- CusackS., . 2013.Gender stereotyping as a Human Rights violation: Research report. Prepared for the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- CreswellJ.W., . 2008.Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- De-HaanJ., Van-der-HofS., BekkersW., PijpersR., . 2013.Self-regulation. In: , ed. a better Internet for Children&author=&publication_year= Towards a better Internet for Children.111-129

- Desarrollo Español de Videojuegos (Ed.). 2016.Llibre blanc de la indústria catalana del videojoc 2016.

- European Commission (Ed.). 2006.Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 (2006/952/EC) on the protection of minors and human dignity and on the right of reply in relation to the competitiveness of the European audiovisual and on-line information services industry.

- European Commission (Ed.). 2012.Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: European Strategy for a better Internet for Children. COM(2012), 196-final.

- 2015.Survey and Data Gathering to support the impact assessment of a possible new legislative proposal concerning. In: CommissionEuropean, ed. 2010/13/EU (AVMSD) and in particular the provisions on the protection of minors, Final Report&author=Commission&publication_year= Directive 2010/13/EU (AVMSD) and in particular the provisions on the protection of minors, Final Report. 2015

- FeliniD., . 2015.today’s video game rating systems: A critical approach to PEGI and ESRB, and proposed improvements&author=Felini&publication_year= Beyond today’s video game rating systems: A critical approach to PEGI and ESRB, and proposed improvements.Games and Culture 10(1):106-122

- FlewittR., MesserD., KucirkovaN., . 2015.directions for early literacy in a digital age: The iPad&author=Flewitt&publication_year= New directions for early literacy in a digital age: The iPad.Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 15(3):289-310

- FornellC., LarckerD.F., . 1981.structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error&author=Fornell&publication_year= Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error.Journal of Marketing Research 18(1):39-50

- GayV., LeijdekkersP., . 2014.of emotion-aware mobile apps for autistic children&author=Gay&publication_year= Design of emotion-aware mobile apps for autistic children.Health and Technology 4(1):21-26