Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Media use plays an important role in the social, emotional, and cognitive development of young individuals and accounts for a large portion of their time. For this reason it is important to understand the variables that contribute to improve the use of the Internet as a source of information and knowledge in formal and informal contexts. How is it possible to exploit the huge potential of this tool to help people learn? What are the cognitive and social characteristics that help individuals experience the Internet without being overwhelmed by its negative effects? What skills are needed to select and manage information and communication? What type of Internet use creates new relationships and ways of learning? A sample of 191 subjects was examined to determine certain characteristic differences between subjects with high and low levels of Internet use. The results show that individuals with high levels of Internet use have higher extroversion and openness scores. The research analyses the use of the Internet in informal contexts to determine the benefits that may result from Internet use in education which may include the development of the skill set necessary to evaluate information critically and analytically and build independent attitudes.

1. Introduction

Media use plays an important role in the social, emotional, and cognitive development of young individuals and accounts for a large portion of their time (Roberts, Foehr & Rideout, 2005). For many people, the Internet has become an essential part of daily life, and they have adopted the innovative linguistic practices, cultural forms and costumes that have emerged. An example of such changes is the fact that literacies (Garton, 1997) are evolving from traditional literacy to multiliteracy practices (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000; Nuzzaci, 2012) that involve the subject viewing, creating and critiquing multi-mode texts (spoken, written, visual, aural and interactive) (New London Group, 2000). Reading and understanding the Internet (Coiro, 2003a; 2003b) represents a new way to explore reality and to build knowledge through the development of unusual relationships. Multiliteracies are therefore a container in which multiple elements converge; giving rise to educational practices that can take place in formal and informal situations. Refers to education, «formal» proposal defines a teaching/learning that takes place in the context of education in which the relationship between teacher and learner is governed on the basis of a normative institutional and ends with the release of an officially recognized certification. The expression «non-formal education» defines a proposal for a teaching/learning process in which the relationship between teacher and learner is not regulated by the legislation that concerns the institutional context of education and does not end with the issuance of a certification officially recognized.

Many people all over the world learn a series of skills through multi-level activities that are put into action when they use the Internet. The concept of multiliteracies incorporates the development of learning potential through the notion that contamination between the social cultures helps to delineate the multiple and complex contemporary languages. An American survey found that 84% of college students possessed a laptop and that 99% used the Internet (Student Monitor, 2003). Students seem to use the Internet to interact with others and find materials for assistance (Kuh & Hu, 2001; Student Monitor, 2003). The Internet is a useful tool for searching information (Kumar & Karapudi, 2012), and is becoming a key tool for news consumption by young people (Casero, 2012), but it is also a «modality/channel» that expands the notion of text to visual, multimodal and electronic hypertexts (Garton, 1997). People search for information on the Internet because they hope that more information will help them make the right purchase decision (Bei & al., 2004) and also to communicate using different modalities. For instance, Soengas (2013) believes that social networks could represent a counterbalance with respect to official censorship and government supported media, and that they helped overcome the isolation of Arab society. The Internet is a powerful device that, if used appropriately, can enhance the development of children’s physical, cognitive, and social skills. Tejedor and Pulido (2012) analyzed current online risks which produce the most emotional distress for children and they focus on how to empower children in their daily Internet use highlighting the importance of the acquisition of skills related to media literacy. The research shows that the Internet is a powerful tool that is revolutionizing thinking mechanisms, learning, communication and play. Peterson and Merino (2003) agree that the Internet makes a large volume and variety of information available with relatively minimal expenditures of time, effort and money.

People can acquire information from web sites that is similar to the information available from traditional mass-media advertising but they can also acquire information directly from physical places (Peterson & Merino, 2003). The media contributes to a re-theorisation of literacy that is incorporated in ideas, practices, interventions and educational practices that teachers can implement in formal contexts (Cuzzocrea, Murdaca & Oliva, 2011). At the same time, the use and implementation of different systems of signification combined with relevant and challenging content enables the students (Gibbons, 2002) to offer sophisticated and critical interpretations and analysis of the world, their own work and the work of others. The Internet allows information to flow freely from one network to another, increasing cultural communication because information passes from one culture to another (i.e. cultural trends include Facebook, instant messaging, blogs, etc.). Cultures can directly communicate with other cultures through elements, signs, systems of signification and cultural symbolism (Nuzzaci, 2011; Nuzzaci, 2012). They use it for activities such as shopping, information and socialization, and in many other ways it is considered to be one of the key factors of innovation towards a «Smart Community» (Nuzzaci & La Vecchia, 2012).

It seems that there is no aspect of life that the Internet does not touch. It is probably the recognition of the predominance of the Internet that has recently led psychologists, pedagogists, sociologists, and semeiologists (Eco, 1975) to focus on this phenomenon (Amichai-Hamburger & Ben-Artzi, 2003). The Internet offers an alternative for people to gratify their social and emotional needs, which might be unmet in their traditional offline networks (Leung, 2003). The increasingly multi-modal nature of our global technology is expressed at different levels and evidence shows that the majority of Internet use is for entertainment (Alvermann & Hagood, 2000; Bearne, 2003; Downes & Zammit, 2001; Sturken & Cartwright, 2001). Cyber-culture does not have a distinctly recognizable form or singular visual style yet; it does seems to mobilize different abilities and resources operating through a combination of perceptions, projections, meanings and interpretations. However, due to the easy accessibility of information, education has been able to advance in many ways. People can now learn about anything using the Internet as a source of information, but much less is known about how people use comprehension strategies during Internet use (Leu, Kinzer, Coiro & Cammack, 2004). Poor empirical evidence has been gathered to support claims that (Salomon, 1994) new types of cognitive processes and strategic knowledge are necessary to effectively locate, comprehend, and use information; the research also analyzes how this is related to the features, characteristics and traits of the individuals and highlights the importance of Internet in education (Keller & Karau, 2013).

With the exploration of context, environment and cultures, there is a decrease in cultural uniqueness because people see there are other possible ways of living life and they gain the abilities (cognitive, social etc.) that help them adapt to a complex society. In the faceless cyberspace, people can create online personas where they alter their identities and «pretend to be» someone other than themselves (Turkle, 1995: 192). They can enjoy aspects of the Internet that allow them to meet, socialize, and exchange ideas through the use of e-mail, ICQ, chat rooms and newsgroups, which in turn «allow the person to fulfil unmet emotional and psychological needs that are more intimate» (Chak & Leung, 2004: 561) and less threatening than real life relationships. Amichai-Hamburger and Ben-Artzi (2000) examined personality theory in relation to Internet use and found it to be connected to different levels of Internet use. They analysed levels of extroversion and neuroticism and found that the individuals showed different patterns in their interaction with the Internet. The main result was that extroverts and introverts use different services on the Internet. Furthermore Amichai-Hamburger and Ben-Artzi (2003) demonstrates not only that personality characteristics are related to different types of Internet use, but also that these personality characteristics are an important indicator of well-being during Internet use. Tosun and Lajunen (2010: 162) indicated that psychoticism was the only personality dimension related to «establishing new relationships and having «Internet only» friends; and extroversion was the only personality dimension» that is related to maintaining long-distance relationships, and supporting daily face-to-face relationships. The results of Tousun and Lajunen (2010: 162) supported the idea that for some individuals, «Internet can be used as social substitute for face-to-face social interactions while for some others» it can be used as a tool of social extension.

Correa, Hinsley, and De-Zuniga (2010: 247) «revealed that while extraversion and openness to experiences were positively related to social media use, emotional stability was a negative predictor». A description of the five personality traits is as follow: openness to experience trait refers to individuals’ receptivity to learning, novelty and change. Individuals who are high in openness to experience tend to be intelligent, curious and like to try new ideas; conscientiousness trait refers to individuals who are rule-following, responsible, dependable, detail-oriented, achievement-oriented, like to plan ahead, thorough and persistent; extraversion trait is related to heightened level of sociability. «Individuals who are high in extraversion are energetic, bold, warm-hearted, outgoing» and enjoy the company of others (Tan & Yang, 2012: 186); agreeableness trait is most concerned with inter-personal relationships. Individuals who are high in this trait tend to be friendly, courteous, considerate, accommodating, tend to avoid conflict, co-operative, helpful, forgiving and show propensity to trust; and neuroticism trait is often known as the anxiety factor. It deals with adjustment and emotional resilience when under stress. Individuals who are high in neuroticism are likely to have higher anxiety level, feel insecure, discontented, sensitive to ridicule, shy and easily embarrassed.

Erjavec (2013: 117) discovered that young children use Facebook for informal learning, but that they believed that there is a connection between use of Facebook and knowledge and skills that their teachers valued in school. «Young students use Facebook primarily for social support and research has shown that there» are gender differences in the expression of emotional support. These results are important because they show that personality is a highly relevant factor in determining behaviour on the Internet. For this reason it is important understand the variables that contribute to improving the Internet use as a source of information and knowledge in formal and informal contexts (Costa & al. 2013).

The Internet has a unique potential to assist people to develop the ability to build and maintain relationships and knowledge. Accessing the information easily, sharing the information and the sources of information are important factors during this process. In a learning context, the Internet can provide effective feedback to the users, enabling pair and group work, enhancing student achievement, providing access to authentic materials, facilitating greater interaction and individualising instruction (Kabilan & Rajab, 2010). In some cases, as McKenna, Green, and Gleason (2002) suggested, there may be a natural transition from an online relationship to an offline association. How is it possible to exploit the huge potential of this tool to help people learn? What are the characteristics and cognitive and social skills needed to help individuals experience the Internet without being overwhelmed by its negative effects? What skills are needed to select and manage information and communication? What uses of the Internet make relationships and learning different? This exploratory study attempted to examine the potential influences of personality variables (emotional stability, extroversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, openness) on Internet use. These characteristics seem to play an important role in Internet use in informal contexts (Murdaca, Cuzzocrea, Conti & Larcan, 2011).

Specifically, the purpose of this study was to examine differences in personality traits, in subjects with a high level of Internet use and subjects with a low level of Internet use after controlling for problematic use of internet. This study used the Big Five Personality Traits taxonomy (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Landers & Lounsbury, 2006). It is a popular personality classification method, and a well-established and unifying framework for measuring personality. The factor of problematic use of internet is considered and controlled because these characteristics are often the subjects of investigation and explain the negative effects that problematic use of internet can have on social and academic development of young adults (Chen & Peng, 2008). Others investigations have been made in order to determine the relation between Internet use and personality. This article brings as a novelty the distinction of personality traits between users with high and users with low levels of Internet use.

Each subject has a cultural profile with their learning outcomes and competencies. This article shall be limited to the first aspect of the problem and postpones to subsequent analysis the exploration of other questions. The significant results motivate to move forward with research. Our hypotheses were examined in a sample of Italian participants. This was deemed important because few studies have examined the role of personality in the internet use in Italy.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample

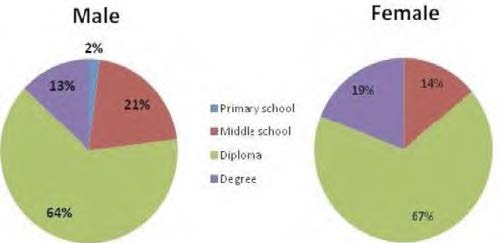

Participants for this study consisted of 89 females and 104 males. Participants were asked to fill a socio-demographic questionnaire asking several questions about age, gender, ethnic background, and educational level. All the 192 participants ranged from 18 to 47 years with a mean of 31.25 (SD=8.62). All participants had the Italian nationality, were Italian-speaking and voluntarily decided to take part in the research. It was a convenience sample and they were recruited by soliciting volunteers through friends, and appeals to community groups such as churches, clubs, associations and local organizations in Messina (Italy). In terms of education level, the majority of male participants reported that they had a high school diploma (64%), 21% had a middle school certificate, 13% had a degree, and 2% had a primary school certificate. The majority of female instead reported that they had a high school diploma (67%), 14% had a middle school certificate and 19% had a degree (fig. 1).

2.2. Procedure and measures

Participants signed an informed consent form. It was emphasized that participation was voluntary. They did not receive money or course credit for participation. Prior to completing the questionnaire, participants were instructed to respond to the questions as honestly as possible, and were told that there were no right or wrong answers. Participants completed the questionnaire in approximately 25 min under the supervision of a researcher.

• Problematic Internet use: To eliminate the potential confounding effects of problematic Internet use, in accordance with the indications of Young (1998) subjects who scored in the at-risk range on Internet addiction scale (i.e., greater than 70; Young, 1998) were excluded from analysis. The 20-item Internet Addiction Test (IAT; Young, 1998) was used (e.g.: How often do you lose sleep due to late-night log-ins?). Respondents are asked to answer the 20 items on a 5-point Likert scale indicating the degree to which Internet use affects their daily routine, social life, productivity, sleeping pattern, and feelings. The higher the score, the greater the problems caused by Internet use. Young found a cut-off score of 70 to indicate a problematic level of Internet use. 7 subjects (3 male and 4 female) who scored in the at-risk range on problematic Internet use were excluded from analysis.

• Internet use and online experience: Internet use was measured by asking respondents (a) the number of days per week they used the Internet and (b) the number of hours and minutes spent on each Internet session. After having excluded subjects at risk for problematic Internet use, subjects were categorized in two groups according to the frequency of Internet use (bottom percentile up to 49, 50 and above top percentile): low use of Internet (N=94) and high use of Internet (N=8).

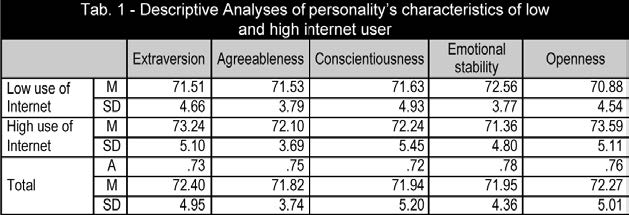

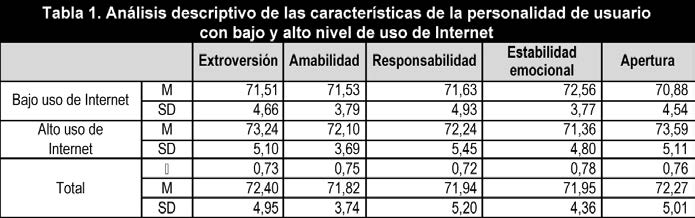

• Personality: Personality traits were measured using the Big Five Questionnaire (BFQ; Caprara, Barbaranelli & Borgogni, 1993). The BFQ contains five domain scales: Energy/Extroversion (e.g., I talk to a lot of different people at parties), Agreeableness/ Friendliness (I am interested in people.), Conscientiousness (e.g., I pay attention to details), Emotional stability (vs. Neuroticism) (e.g.: I am relaxed most of the time), and Openness (e.g.: I am full of ideas). For each of the 132 items, respondents indicated the extent to which they assign personal relevance to it on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (very false for me) to 5 (very true for me). Validity of the BFQ scales has been demonstrated by high correlations with analogous scales, such as the NEO-PI, on both Italian and American samples (Barbaranelli & Caprara, 2000). Alpha coefficients for the present study are presented in table 1.

3. Results

The Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS 15.1) was used. Group differences were analyzed using a multivariate of variance (MANOVA) and t-test for simple independent groups comparing and t-test for dependent groups in order to verify differences in trait’s personality. All dates were transformed in sin-1 (Freeman & Tukey, 1950) to normalize the distribution.

Descriptive Analyses of personality in the two groups are synthesized in table 1. Participants reported to be on line with a mean of 21.66 hours (SD=20.26) for weak: low users remain on line with a mean of 7.19 (SD=4.33), while high users of internet reported a mean of 35.21 (SD=19.99).

Differences between groups [F(1,190)=6.36; p=.012] were found. The tests between groups showed that subjects with higher levels of Internet use had higher Extroversion scores [t(190)=2.44; p=.02] and a higher score on the Openness scale [t(190) =3.86; p=.001] compared to subjects with lower levels of Internet use. However, the testing within the groups yielded no significant differences when comparing the five traits [F(4,760)=.55; p=.696]. There were differences within personality traits connected to the different levels of Internet use [F(4, 760) =5.30; p=.001]. In fact, a paired sample test showed that subjects that have lower levels of Internet use scored higher in emotional stability than in Openness [t(93)=2.74; p=.007], and subjects that have higher level of Internet use scored lower in emotional stability than in Openness [t(97)= 3.28; p=.001]. Subjects that have higher levels of Internet use showed higher levels of Extroversion than Emotional Stability [t(97)=2.78; p= .006]. Finally subject that have higher levels of Internet use showed a higher level of Openness than Agreeableness [t(97)=2.50; p=.014].

4. Discussion and conclusion

Results have shown that subjects with high levels of Internet use have higher scores in extroversion and openness. These preliminary results of the research illustrate the potential and the advantages that could come from using the Internet for education. People with high levels of extroversion are assertive, energetic, active, upbeat, and excitable. The excitement and sensory stimulation sought by extroverts’ leads them to use Internet to satisfy their emotional and social needs. Instead, openness to experience describes the originality and complexity of an individual’s mental and experiential life and is characterized by activity, imagination, aesthetics, and sensitivity. Subjects that scored higher could use Internet to satisfy their need to explore and to improve their knowledge. In fact, in according with Correa & al. (2010) the positive relationship between openness to experiences and social media use found in this study was expected given the novel nature of these technologies.

Therefore, this may explain why extraverted, rather than introverted, people tend to engage in social media use. These results are consistent with other studies that explored the relationship between personality traits and Facebook and social media use (Correa & al., 2010). This result suggests that given the influence of these social media on today’s social interactions –more than half of America’s teens and young adults use them and more than one-third of all Web users engage in these activities– Internet designers should take into account users’ characteristics and needs (Hamburger & Ben-Artzi, 2000). The same thing should happen to the school context in situations of instructional design. Social networks can become a resource for teaching and learning when they become part of a deliberate and rational process that can be located and developed within different contexts and operational knowledge with evident implication for the opportunity to improve educational outcomes, using technologies that students are accustomed to. The results of this research indicate that the use of Internet could provide the opportunity to improve educational outcomes using technology with which the students were already familiar, especially in creating a favorable disposition to learning in the school environment using the resources available in the informal contexts (Costa & al., 2013).

In according with Correa & al. (2010) and using the notions of digital natives and digital immigrants (Prensky, 2001), this study concludes that many digital immigrants confront each change in technology as something new to be mastered. Correa & al. (2010) found that older people who are predisposed to being open to new activities are more likely to engage in social media use while for younger generations using the Internet as a social media tool has more to do with being extraverted. Younger people grew up with these digital options at their disposal to interact and communicate, making them digital natives (Prensky, 2001) and often show more skills in using digital technologies of those of teachers. If the teachers were using in the school context the same tools that the students use to communicate could identify the best solutions to help them teach better and to make their teaching more responsive to the characteristics of the students, by applying force on those variables that constitute the engine of learning (emotionality) and stimulating higher-order skills (awareness and open-mindedness), as well as meeting new forms of multi-literacy. The authors of this paper are working in this direction with a series of research initiatives that link the isolation of significant variables in the informal setting in order to verify the effects in formal context (Costa & al., 2013) and the relationship between digital competence and multiliteracies (Nuzzaci, 2011; 2012).

This research is grounded within the theoretical framework that the use of Internet goes beyond informal learning and includes the use of information in a critical or analytic manner and building an open mind and independent attitude. Technology is an integrated part of today’s schooling and everyday practice and for this reason future research should focus on assessing how students use technology as thinking tools in order to search, produce, manage, analyse, and share knowledge as well as solve complex problems individually and collaboratively (Häkkinen & Hämäläinen, 2012). Numerous researchers have been arguing that using information and computer technologies (ICTs) in traditional paper-based reading activities can maximize students’ reading comprehension in a technology-supported learning setting (Chen, Kinshuk, Wei & Yang, 2008; Grasset, Dunser & Billignhurst, 2008). This experience promotes critical thinking and communication, even if such impact needs to be supported by further well-documented evidence since conditional effects are relatively unknown.

Combining digital information with physical objects is the trend in education, which allows students to use technology in the classroom (Huang, Wu & Chen, 2012). Furthermore, Barron (2006) refers to the importance of self-initiated and interest-driven learning that takes place across formal and informal learning settings. For this reason, powerful computer-supported collaborative environments can be seen as essential elements in the re-structuring of social interaction and creation of knowledge (Häkkinen & Hämäläinen, 2012).

There are still some open questions and more evidence is needed for:

• Hp1 - Selective use and awareness promote the integration of all subjects and school groups.

• Hp2 – Raising performance standards in the use of Internet due to high performance standards promotes critical thinking for all subjects and school groups.

• Hp3 - Raising performance standards of Internet use due to high faculty standards promotes social awareness for all subjects and school groups.

• Hp4 - Raising performance standards in the use of Internet predicts awareness for all subjects and groups.

• Hp5 - Raising performance standards of Internet use promotes critical thinking.

• Hp6 - Raising performance standards of Internet use promotes aspirations for all subjects and groups.

The contribution suggests avenues for future research for better understanding whether the nature of the variables of use of Internet differs in certain ways, thus producing dissimilar outcomes for different groups of subjects in relation to their personal characteristics. In order to comprehensively examine the relationship between personal characteristics and uses/ interaction, educational outcomes and gender race status should also be considered. In this sense, more analysis should be conducted and other instruments used to determine whether the relationships are significantly different for student subgroups. Interestingly, the types of use of Internet relate to smaller gains in cultural appreciation and social awareness. Other research shows an impact on student outcomes. The results bring to light that students, who use the Internet in a more selective and conscious way, possess higher skill levels and tend to aspire to more advanced degrees. This research contributes to clarifying the elements that act as a backdrop in the relationship between learning that takes place in informal and formal contexts, and it helps to understand how to build new forms of literacy. This relates to cultural appreciation and social awareness that represent vital factors in the improvement of the cultural profiles of the population.

Notes

Costa S. assisted with generation of the initial draft of this manuscript and data analyses. Cuzzocrea F. assisted with study design, data analysis and interpretation and manuscript editing. Nuzzaci A. assisted with concept, manuscript preparation and editing and study supervision. All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

References

Amichai-Hamburger, Y. & Ben-Artzi, E. (2003). Loneliness and Internet Use. Computers in Human Behavior, 19 (1), 71-80. (DOI: 10.1016/S0747-5632(02)00014-6).

Barbaranelli, C. & Caprara, G.V. (2000). Measuring the Big five in Self Report and Other Ratings: A Multitrait-multimethod Study. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 16 (1), 31-43. (DOI: 10.1027//1015-5759.16.1.31).

Barron, B. (2006). Interest and Self-sustained Learning as Catalysts of Development: A Learning Ecologies Perspective. Human Development, 49 (4), 193-224. (DOI: 10.1159/000094368).

Bearne, E. (2003). Rethinking Literacy: Communication, Representation and Text. Literacy, 37 (3), 98-103. (DOI: 10.1046/j.0034-0472.2003.03703002.x).

Bei, L-T, Chen, E.Y.I. & Widdows, R. (2004). Consumers’ Online Information Search Behavior and the Phenomenon of Search and Experience Products. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 25 (4), 449-467. (DOI: 10.1007/s10834-004-5490-0).

Caprara, G.V., Barbaranelli, C. & Borgogni, L. (1993). BFQ: Big Five Questionnaire. Firenze: OS, Organizzazioni Speciali.

Casero-Ripollés, A. (2012). Beyond Newspapers: News Consumption among Young People in the Digital Era. Comunicar, 20 (39), 151-158. (DOI: 10.3916/C39-2012-03-05).

Chen, N.S., Kinshuk, Wei, C.W. & Yang, S.J.H. (2008). Designing a Self-contained Group Area Network for Ubiquitous Learning. Educational Technology & Society, 11(2), 16-26.

Chen, Y.F. & Peng, S.S. (2008). University Students’ Internet Use and its Relationships with Academic Performance, Interpersonal Relationships, Psychosocial Adjustment, and Self-evaluation. Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 11 (4), 467-469. (DOI: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0128).

Coiro, J. (2003a). Reading Comprehension on the Internet: Expanding our Understanding of Reading Comprehension to Encompass New Literacies. The Reading Teacher, 56(5), 458-464.

Coiro, J. (2003b). Rethinking Comprehension Strategies to Better Prepare Students for Critically Evaluating Content on the Internet. The NERA Journal, 39 (2), 29-34.

Cope, B. & Kalantzis, M. (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures. South Melbourne: Macmillan.

Correa, T., Hinsley, A.W. & De-Zúñiga, H.G. (2010). Who Interacts on the Web?: The Intersection of Users’ Personality and Social Media Use. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 247-253. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2009.09.003).

Costa Jr, P.T. & McCrae, R.R. (1992). Four Ways Five Factors Are Basic. Personality and Individual Differences, 13 (6), 653-665. (DOI: 10.1016/0191-8869(92)90236-I).

Costa, S., Cuzzocrea, F., La Vecchia, L., Murdaca, A.M. & Nuzzaci, A. (2013). A Study on the Use of Facebook in Informal Learning Contexts: What are the Prospects for Formal Contexts? International Journal of Digital Literacy and Digital Competence (IJDLDC), 4 (1), 1-11. (DOI: 10.4018/jdldc.2013010101).

Cuzzocrea, F., Murdaca, A., Oliva P. (2011). Using Precision Teaching Software to Improve Foreign Language and Cognitive Skills in University Students. International Journal of Digital Literacy and Digital Competence, 2 (4), 50-60. (DOI: 10.4018/978-1-4666-2943-1.ch014).

Downes, T. & Zammit, K. (2001). New Literacies for Connected Learning in Global Classrooms. A Framework for the Future. In P. Hogenbirk & H. Taylor (Eds.), the Bookmark of the School of the Future (113-128). Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Eco, U. (1975). Trattato di semiotica generale. Milano: Bompiani.

Erjavec, K. (2013). Informal Learning through Facebook among Slovenian Pupils. Comunicar, 21 (40), 607-611 (DOI: 10.3916/C41-2013-11).

Freeman, M.F. & Tukey, J.W. (1950). Transformations Related to the Angular and the Square Root. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 21 (4), 607-611. (DOI: 10.1214/aoms/1177729756).

Garton, J. (1997). New Genres and New Literacies: The Challenge of the Virtual Curriculum. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 20 (3), 209-221.

Gibbons, P. (2002). Scaffolding Language, Scaffolding Learning: Teaching Second Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom. Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Grasset, R., Dunser, A. & Billignhurst, M. (2008). The Design of a Mixed-reality Book: is it Still a Real Book? In Proceedings of the 2008 7th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (Ismar ’08) (pp. 99-102).

Hamburger, Y.A. & Ben-Artzi, E. (2000). The Relationship between Extraversion and Neuroticism and the Different Uses of the Internet. Computers in Human Behavior, 16 (4), 441-449. (DOI: 10.1016/S0747-5632(00)00017-0).

Huang, H.W., Wu, C.W. & Chen, N.S. (2012). The Effectiveness of Using Procedural Scaffoldings in a Paper-plus-smartphone Collaborative Learning Context. Computers & Education, 59 (2), 250-259. (DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.01.015).

Häkkinen, P. & Hämäläinen, R. (2012). Shared and Personal Learning Spaces: Challenges for Pedagogical Design. The Internet and Higher Education, 15 (4), 231-236. (DOI: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.09.001).

Kabilan, M. & Rajab, B. (2010). The Utilisation of the Internet by Palestinian English Language Teachers Focusing on Uses, Practices and Barriers and Overall Contribution to Professional Development. International Journal of Education and Development Using ICT, 6 (3), 56-72.

Keller, H. & Karau, S.J. (2013). The Importance of Personality in Students’ Perceptions of the Online Learning Experience. Computers in Human Behavior, 29 (6), 2494-2500. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.06.007).

Kuh, G.D. & Hu, S. (2001). The Effects of Student-faculty Interaction in the 1990s. The Review of Higher Education, 24 (3), 309-332. (DOI: 10.1353/rhe.2001.0005).

Kumar, M.M. & Karapudi, B. (2012). Students’ Insight on Internet Usage: A Study. SRELS Journal of Information Management, 49 (3), 331-339.

Landers, R.N. & Lounsbury, J.W. (2006). An Investigation of Big Five and Narrow Personality Traits in Relation to Internet Usage. Computers in Human Behavior, 22 (2), 283-293. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2004.06.001).

Leu, D.J., JR., Kinzer, C.K., Coiro, J. & Cammack, D.W. (2004). Toward a Theory of New Literacies Emerging from the Internet and Other Information and Communication Technologies. In R.B. Ruddell & N. Unrau (Eds.), Theoretical Models and Processes of Reading (pp. 1570-1613). Newark: International Reading Association.

Leung, L. (2003). Impacts of Net-generation attributes, Seductive Properties of the Internet, and Gratifications-obtained on Internet Use. Telematics and Informatics, 20 (2), 107-129. (DOI: 10.1016/S0736-5853(02)00019-9).

McKenna, K.Y.A., Green, A.S. & Gleason, M.J. (2002). Relationship Formation on the Internet: What’s the Big Attraction? Journal of Social Issues, 58 (1), 9-32. (DOI: 10.1111/1540-4560.00246).

Murdaca A., Cuzzocrea F., Conti F. & Larcan R. (2011). Evaluation of Internet Use and Personality Characteristics. REM - Research on Education and Media, 3(2), 75-93.

New London Group (Ed.) (2000). A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures (pp. 9-38). South Melbourne: Macmillan.

Nuzzaci, A. & La Vecchia, L. (2012). A Smart University for a Smart City. International Journal of Digital Literacy and Digital Competence (IJDLDC), 3 (4), 16-32. (DOI: 10.4018/jdldc.2012100102).

Nuzzaci, A. (2012). The «Technological good» in the Multiliteracies Processes of Teachers and Students. International Journal of Digital Literacy and Digital Competence, 3 (3), 12-26. (DOI: 10.4018/jdldc.2012070102).

Nuzzaci, A. (2013). The Use of Facebook in Informal Contexts: What Implication does it have for Formal Contexts? In Convegno SIREM 2013, ICT in Higher Education and Lifelong Learning, Bari, 14-15 Novembre 2013, Università degli Studi di Bari.

Nuzzaci, A. (Ed.) (2011). Patrimoni culturali, educazioni, territori: verso un’idea di multiliteracy. Lecce: Pensa Multimedia.

Peterson, R.A. & Merino, M.C. (2003). Consumer Information Search Behaviour and the Internet. Psychology & Marketing, 20 (2), 99-121. (DOI: 10.1002/mar.10062).

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, Digital Immigrants part 1. On the horizon, 9 (5), 1-6.

Roberts, D.F., Foehr, U.G. & Rideout, V.J. (2005). Generation M: Media in the lives of 8-18 year-olds. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. January 2010. (http://goo.gl/bu2d3y).

Salomon, G. (1994). Interaction of Media, Cognition and Learning. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Soengas, X. (2013). The Role of the Internet and Social Networks in the Arab Uprisings. An Alternative to Official Press Censorship. Comunicar, Scientific Journal of Media Education, 21(41), 147-155 (DOI: 10.3916/C41-2013-14).

Student Monitor (2003). Computing & the Internet: Fall 2002. Ridgewood: Author.

Sturken, M. & Cartwright, L. (2001). Practices of Looking: Images, Power, and Politics & Viewers Make Meaning. Oxford-NewYork: Oxford University Press.

Tejedor, S. & Pulido, C. (2012). Challenges and Risks of Internet Use by Children. How to Empower Minors? Comunicar, 20 (39), 65-72 (DOI: 10.3916/C39-2012-02-06).

Tosun, L.P. & Lajunen, T. (2010). Does Internet Use Reflect your Personality? Relationship between Eysenck’s Personality Dimensions and Internet Use. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(2), 162-167. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2009.10.010).

Turkle, S. (1995). Life on the Screen. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Young, K.S. (1998). Internet Addiction: The Emergence of a New Clinical Disorder. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 1 (3), 237-244. (DOI: 10.1089/cpb.1998.1.237).

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El uso de Internet ofrece un importante espacio para el desarrollo social, emocional y cognitivo de los jóvenes y ocupa gran parte de su tiempo libre. Por lo tanto, es muy importante observar algunas variables que contribuyen a mejorar su uso como fuente de información y conocimiento en contextos formales e informales. ¿Cómo, entonces, aprovechar el enorme potencial de esta herramienta para ayudar a las personas en su aprendizaje?, ¿cuáles son las características cognitivas y sociales que ayudan a utilizarla sin que les afecte negativamente?, ¿qué habilidades se necesitan para seleccionar y gestionar la información y la comunicación?, ¿qué tipos de usos de Internet suscitan aprendizaje y nuevas y diferentes relaciones? En una muestra de 191 sujetos se examinan las diferentes características entre los sujetos con alto y bajo nivel de uso. Los resultados muestran que los individuos con alto nivel de uso de Internet tienen una puntuación más alta en lo que se refiere a las características de extroversión y apertura. La investigación se basa en un marco teórico que parte del análisis del uso de en un contexto informal para llegar a una reflexión sobre las posibilidades y ventajas que pueden derivarse de su uso en la educación, y del conjunto de habilidades que es necesario desarrollar para utilizar y evaluar la información de manera crítica y analítica y para construir una mente abierta y una actitud independiente.

1. Introducción

El empleo de medios de comunicación juega un papel importante en el desarrollo social, emocional, y cognitivo de individuos jóvenes y representa una parte importante de su tiempo (Roberts, Foehr & Rideout, 2005). Para muchas personas, Internet es esencial en su vida diaria, y ha contribuido a adaptar prácticas innovadoras lingüísticas, así como hábitos culturales que han ido surgiendo. Un ejemplo de estos cambios es el hecho que la alfabetización (Garton, 1997) se está transformando de una alfabetización tradicional a prácticas de multialfabetización (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000; Nuzzaci, 2012) lo que implica la observación del sujeto, la creación y la crítica de textos multimodales (oral, escrito, visual, auditivo e interactivo) (New London Group, 2000). Leer y aprender en Internet (Coiro, 2003a; 2003b) representan un nuevo modo de explorar la realidad y construir el conocimiento gracias al desarrollo de relaciones insólitas. La multialfabetización es, por lo tanto, un contenedor donde convergen múltiples elementos; donde pueden tener lugar las prácticas educativas que surgen tanto en situaciones formales como informales. Por lo que se refiere a la educación, la oferta «formal» define un proceso de enseñanza/aprendizaje que se desarrolla en el contexto educativo donde tiene lugar la relación entre el profesor y el principiante. Esta relación se rige sobre la base de una normativa institucional y termina con la concesión de un certificado oficial. La expresión «educación no formal» define una propuesta de enseñanza/aprendizaje en la que la relación entre el profesor y el principiante no es regulada según la legislación educativa y no termina con la emisión de un certificado con reconocimiento oficial. Muchas personas en todo el mundo aprenden una serie de habilidades por las actividades de multinivel que se activan cuando utilizan Internet. El concepto de multialfabetización incorpora la posibilidad de aprender por el hecho de que la contaminación entre las diferentes culturas ayuda a delinear lenguajes múltiples, complejos y contemporáneos. Según los datos de un estudio americano sobre estudiantes de primaria (Student Monitor, 2003), el 84% de estos estudiantes poseía un ordenador portátil y el 99% usaba Internet. Parece que los estudiantes usan la Red para socializarse entre ellos y para encontrar recursos (Kuh & Hu, 2001; Student Monitor, 2003). Internet es un instrumento útil para buscar información (Kumar & Karapudi, 2012), y es además un instrumento clave para el consumo de noticias en los jóvenes (Casero-Ripollés, 2012), pero es también «una modalidad/canal» que amplía la noción de texto a hipertextos visuales, multimodales y electrónicos (Garton, 1997). Los usuarios buscan información variada en Internet porque esperan que esta les ayude a tomar la justa decisión sobre los diferentes productos que pueden comprar y sobre diferentes alternativas (Bei, Chen & Widdows, 2004). Por ejemplo, Soengas (2013) cree que las redes sociales podrían representar un contrapeso a la censura oficial y a los medios de comunicación apoyados por el gobierno, y que fueron precisamente las redes sociales las que ayudaron a vencer el aislamiento de la sociedad árabe. Internet es un dispositivo poderoso que, usado de manera apropiada, puede mejorar el desarrollo físico, cognoscitivo y las habilidades sociales de los niños.

Tejedor y Pulido (2012) analizan los riesgos actuales como origen de la mayor parte de los trastornos emocionales en los niños. Destacan la necesidad de regularizar el empleo diario de la Red de los niños, resaltando la importancia de la adquisición de habilidades relacionadas con la alfabetización mediática. La investigación muestra que Internet es un instrumento poderoso que revoluciona mecanismos de pensamiento, de estudio, de comunicación y de juego. Peterson y Merino (2003) coinciden en afirmar que Internet genera un gran volumen de información variada, comportando gastos relativamente mínimos de tiempo, esfuerzo y dinero. Los usuarios pueden adquirir en la web información sobre publicidad similar a la información disponible en la medios de comunicación tradicionales y también pueden adquirir la información directamente en sitios físicos (Peterson & Merino, 2003). Los medios de comunicación contribuyen pues a una re-teorización de la alfabetización que se incorpora a las ideas, intervenciones y prácticas educativas y que los profesores pueden poner en práctica en contextos formales (Cuzzocrea, Murdaca & Oliva, 2011). Al mismo tiempo, el empleo y la puesta en práctica de sistemas diferentes de significado, combinado con contenido relevante y desafiante, permite a los estudiantes (Gibbons, 2002) ofrecer interpretaciones complejas y críticas y el análisis del mundo, de su propio quehacer y del de otros. Internet permite que la información fluya libremente de una red a otra, aumentando la comunicación cultural (por ejemplo, tendencias culturales diferentes que se incluyen en Facebook, en la mensajería instantánea, en blogs...).

Las diferentes culturas pueden poner en relación directamente con otras sus elementos, signos, sistemas de significado y simbolismo cultural (Nuzzaci, 2011; Nuzzaci, 2012). Estos elementos se emplean en actividades como compras, información y socialización, entre otras, constituyéndose en uno de los factores claves de innovación hacia «una comunidad simpática» (Nuzzaci & La Vecchia, 2012). Parece pues que no hay ningún aspecto de la vida que Internet no abarque. Es el reconocimiento del poder de la Red, afirmado por psicólogos, pedagogos, sociólogos y semiólogos (Eco, 1975), según el enfoque del fenómeno que realiza Amichai-Hamburger y Ben-Artzi (2003). Internet ofrece la posibilidad de satisfacer las necesidades sociales y emocionales de las personas, necesidades que no podrían ser colmadas en sus autónomas redes tradicionales (Leung, 2003). El carácter cada vez más multimodal de nuestra tecnología global se expresa en niveles diferentes, pero los resultados muestran que el principal uso es el socializador (Alvermann & Hagood, 2000; Bearne, 2003; Downes & Zammit, 2001; Sturken & Cartwright, 2001).

La cibercultura aún no tiene una forma claramente reconocible o un estilo visual singular; más bien moviliza capacidades y recursos diferentes que funcionan gracias a una combinación de percepciones, proyecciones, significados e interpretaciones. Sin embargo gracias al fácil acceso a la información, la educación ha podido avanzar mucho. En la actualidad se puede lograr el aprendizaje si se utiliza Internet como fuente de información, sin embargo se conoce poco cuáles son las estrategias de comprensión que los usuarios ponen en práctica cuando usan Internet (Leu, Kinzer, Coiro & Cammack, 2004). Son escasas las pruebas empíricas que subrayan la necesidad de nuevos tipos de procesos cognoscitivos y de conocimiento estratégico para localizar, comprender y usar la información con eficacia (Salomon, 1994). La investigación también analiza cómo este proceso se relaciona con las características y rasgos de los individuos y destaca el importante papel de la Red en la educación (Keller & Karau, 2013). Con la exploración del contexto y el entorno de las diferentes culturas, disminuye la unicidad cultural: al conocerse que hay otros modos posibles de vida se adquieren las capacidades (cognoscitivas, sociales, etc.) que nos ayudan a adaptarnos a una sociedad compleja. En el ciberespacio anónimo, la gente puede crearse personalidades diferentes, cambiar su identidad y ser la persona que quiera ser (Turkle, 1995). Internet permite y ofrece la posibilidad de encontrar a otros, socializar e intercambiar ideas gracias al correo electrónico, ICQ, chats y grupos de discusión, así como la posibilidad de satisfacer necesidades emocionales y psicológicas de forma más íntima y menos traicionera que las relaciones de la vida verdadera. Amichai-Hamburger y Ben-Artzi (2000) examinaron la teoría de la personalidad con relación al uso de la Red pudiendo establecer la existencia de una relación que varía mucho según sean los diferentes niveles de uso de Internet. Concretamente analizaron los niveles de extroversión e introversión y mostraron cómo los individuos extrovertidos e introvertidos interactúan en la Red de forma diferente. También estos mismos autores en 2003 afirmaron que los rasgos de la personalidad no solo están relacionados con los diferentes tipos de uso, sino también que estas características son importantes indicadores de bienestar.

Tosun y Lajunen (2010) señalan que la introversión es una dimensión característica de una personalidad propicia al establecimiento de nuevas relaciones de amistad solo en la Red; y por el contrario la extroversión se concreta en el mantenimiento de relaciones de fondo y en el cultivo diario de las relaciones reales. Los resultados de Tousun y Lajunen (2010) apoyaron la idea que para algunos individuos Internet puede ser considerado como un sustitutivo de las interacciones sociales reales, mientras que para otros puede ser un instrumento de extensión social. Correa, Hinsley y De-Zúñiga (2010) revelaron que mientras las personas extrovertidas y sinceras tienden al uso de los medios de comunicación social, las personalidades con más estabilidad emocional tienden a una utilización menos frecuente. Y describen cinco rasgos de la personalidad: la cualidad de la apertura a nuevas experiencias, se refiere a la receptividad de los individuos hacia la novedad y el cambio. Los individuos que presentan un alto nivel de apertura a nuevas experiencias suelen ser inteligentes, curiosos y les gusta poner en práctica nuevas ideas; la personalidad meticulosa se refiere a individuos generalmente responsables, serios, que cuidan los detalles, orientados al éxito, y a los que les gusta planificar el futuro, cuidadosos y persistentes; la extroversión se relaciona con un alto nivel de sociabilidad. Estos individuos son enérgicos, valientes, cariñosos, abiertos y disfrutan con la compañía de los demás; el rasgo de la simpatía se refiere a las relaciones interpersonales. Los individuos que poseen un nivel alto en este rasgo suelen ser amistosos, amables, considerados, tolerantes, tienden a evitar el conflicto, cooperan, ayudan, perdonan y son confiados. La introversión es un factor de ansiedad está relacionado con la adaptación emocional bajo estrés. Los individuos que presentan un nivel alto de introversión probablemente tienen el nivel de ansiedad también más alto, se sienten inseguros, descontentos, tienen miedo al ridículo y se sienten incómodos.

Erjavec (2013) demostró que los más pequeños usan Facebook para el aprendizaje informal, pero creen que hay una conexión entre el empleo de Facebook y el reconocimiento y la valoración de sus capacidades por parte de sus profesores. Los estudiantes jóvenes usan Facebook principalmente para el apoyo social, y la investigación ha mostrado diferencias sexuales en la expresión de este apoyo emocional.

Estos resultados son importantes porque muestran que la personalidad es un factor sumamente relevante en la determinación del comportamiento en el uso de Internet. Por esta razón es importante entender las variables que contribuyen al mejoramiento de su uso como fuente de información y conocimiento en contextos formales e informales (Costa & al., 2013). Internet tiene un potencial único como herramienta de ayuda a la hora de desarrollar la capacidad de construir y mantener relaciones y amistades. El tener fácil acceso a la información y el poder compartirla son factores importantes durante este proceso. En un proceso de aprendizaje Internet puede proporcionar un feedback eficaz a los usuarios, mejorando el trabajo de grupo y el trabajo individual, optimizando el éxito del estudiante, proporcionando el acceso a materiales auténticos, facilitando la interacción mayor e individualizando la educación (Kabilan & Rajab, 2010). En algunos casos, como McKenna, Green y Gleason (2002) sugieren, puede haber una transición natural de una relación en línea a un aprendizaje autónomo.

¿Cómo es posible explotar el enorme potencial de este instrumento para que las personas aprendan? ¿Cuáles son las habilidades sociales y cognitivas que se necesitan para disfrutar del uso de Internet sin sufrir demasiados efectos secundarios? ¿Qué habilidades son necesarias para seleccionar y manejar la información y la comunicación? Este estudio exploratorio intenta examinar las influencias potenciales de algunas variables de personalidad (la estabilidad emocional, la extroversión, la meticulosidad, la amistad, la apertura a nuevas experiencias), cuando se usa. Estas características parecen jugar un papel importante en el empleo en contextos informales (Murdaca, Cuzzocrea, Conti & Larcan, 2011). Expresamente, el objetivo de este estudio es examinar las diferencias de los rasgos de personalidad de sujetos con un nivel alto de uso y sujetos con un nivel bajo de uso, una vez que se ha controlado su empleo problemático.

Este estudio ha utilizado la taxonomía de «Big five personality traits» (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Landers & Lounsbury, 2006). Este es un método popular de clasificación de la personalidad y se establece como marco común y unificador a fin de medir la personalidad. El factor de un empleo problemático de Internet se tiene en cuenta y se controla porque estas características se dan a menudo en el sujeto de la investigación, y se explican los efectos negativos que el empleo problemático puede tener sobre el desarrollo social y académico de adultos jóvenes (Chen & Peng, 2008). Existen otras investigaciones que han determinado la relación entre el uso de Internet y la personalidad. Este artículo presenta como novedad la distinción de rasgos de personalidad entre usuarios con alto nivel de uso de Internet y usuarios con un nivel bajo de uso. Cada sujeto tiene un perfil cultural por el estudio de sus resultados y capacidades.

Este artículo se limita a un primer aspecto del problema y deja otras cuestiones para investigaciones posteriores. Los resultados alcanzados se presentan como un estímulo para continuar con futuras investigaciones. Nuestras hipótesis fueron contrastadas en una muestra de participantes italianos. Nos parece un aspecto destacable puesto que son pocos los estudios que han examinado el papel de la personalidad en el uso de Internet en Italia.

2. Material y métodos

2.1. Muestra

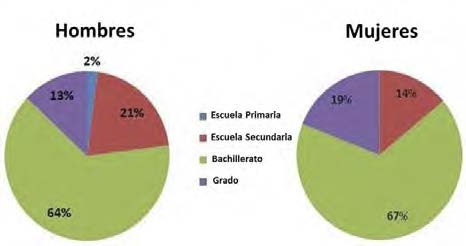

Los participantes en este estudio han sido 89 mujeres y 104 hombres. Se les pidió cumplimentar un cuestionario socio-demográfico con varias preguntas sobre la edad, el sexo, la nacionalidad y el nivel educativo. Los 192 participantes tenían entre 18 y 47 años con una media de 31,25 (SD=8.62). Todos los participantes tenían la nacionalidad italiana, eran de habla italiana y habían decidido voluntariamente participar en la investigación. Esta muestra aleatoria se eligió entre amigos, grupos de comunidades –como iglesias, clubs, asociaciones y organizaciones locales– de Messina (Italia). En cuanto al nivel de educación, la mayoría de participantes masculinos declaró tener estudios de bachillerato (el 64%), el 21% contaba con un certificado de secundaria, el 13% tenía un grado, y el 2% un certificado de escuela primaria. La mayoría de las mujeres en cambio, declaró tener un título de bachillerato (el 67%), el 14% tenía un certificado de escuela secundaria y el 19 % estaba en posesión de un grado (figura 1).

2.2. Procedimiento y método

Los participantes firmaron un formulario en el que daban su consentimiento. Se hizo hincapié en que la participación era voluntaria. No recibieron dinero alguno o créditos por participar. Antes de completar el cuestionario, se instó a los participantes a que respondieran a las preguntas lo más honestamente posible y se les dijo que no había respuestas correctas o incorrectas. Los participantes completaron el cuestionario en aproximadamente unos 25 minutos bajo la supervisión de un investigador.

• Empleo problemático de Internet: para eliminar los potenciales efectos problemáticos de su uso, según las indicaciones de Young (1998) los sujetos que presentaron valores de riesgo en la escala de adicción a Internet (es decir, mayor a 70) fueron excluidos del análisis. Se utilizó pues la prueba de adicción desarrollada por este autor (Young, 1998) donde se pide a los sujetos que contesten a los 20 enunciados utilizando una escala de Likert de cinco puntos, que indica en qué grado el uso afecta el orden de su jornada, la vida social, la productividad y otros factores (por ejemplo, ¿Pierde usted el sueño a menudo debido a conexiones nocturnas?). Cuantos más altos son los niveles, más frecuentes son los problemas causados por el uso. Young sostuvo que un nivel de 70 era problemático. En la investigación, siete sujetos (tres hombres y cuatro mujeres) fueron excluidos del análisis después de haber presentado niveles de riesgo.

• Empleo de Internet y experiencia en línea: su empleo fue medido preguntando a) el número de días por semana en los que la usaron, y b) el número de horas y minutos empleados en cada sesión. Después de excluir los sujetos con riesgo de su empleo problemático, los participantes fueron clasificados en dos grupos según la frecuencia de empleo de Internet (el porcentaje inferior hasta 49, y a partir de 50 el porcentaje superior): bajo empleo (N=94) y alto empleo (N=98).

• Personalidad: los rasgos de personalidad se midieron usando el cuestionario «Big Five» (BFQ) (Caprara, Barbaranelli & Borgogni, 1993). El BFQ contiene cinco escalas de dominio: la extroversión (por ejemplo, me relaciono con mucha gente), la amabilidad (me intereso por los demás), la responsabilidad (por ejemplo, presto atención a los detalles), la estabilidad emocional, contraria al nerviosismo (por ejemplo estoy relajado la mayor parte del tiempo) y la apertura a nuevas experiencias (por ejemplo: estoy lleno de ideas). Para cada uno de los 132 enunciados, los sujetos indicaron el grado de importancia personal en una escala de 5 puntos con los límites de 1 (muy falso para mí) a 5 (muy verdadero para mí). La validez de la medición de la BFQ ha quedado demostrada por las altas correlaciones con escalas análogas, como la NEO-PI, tanto sobre muestras italianas como sobre muestras americanas (Barbaranelli & Caprara, 2000). El coeficiente alfa para el estudio presente se representa en 1.

3. Resultados

Se utilizó el programa SPSS (versión 15.1). Las diferencias de grupo fueron analizadas usando una multivariante de discrepancia (MANOVA) y la prueba de t para grupos simples independientes que se comparan y la prueba de t para grupos dependientes para verificar las diferencias de los rasgos de personalidad. Todas las fechas fueron transformadas en sin-1 (Freeman & Tukey, 1950) para normalizar la distribución.

Los análisis descriptivos de personalidad en los dos grupos se sintetizan en la tabla 1. Los participantes hicieron un informe sobre el tiempo en línea con una media de 21,66 horas (SD=20,26) para un uso débil: usuarios bajos permanecen en línea con una media de 7,19 (SD=4,33), mientras los altos usuarios de Internet hicieron un informe con una media de 35,21 (SD=19,99).

Se encontraron diferencias entre los grupos [F (1,190)=6,36; p=0,012]. Las pruebas mostraron que los sujetos con los niveles más altos de uso también tenían niveles de extroversión más altos [la t (190)= 2,44; p=0,02] y una puntuación más alta en la escala de apertura a nuevas experiencias [la t (190)=3,86; p=0,001] en comparación con los sujetos con niveles inferiores de uso de Internet. Sin embargo, las pruebas dentro de los grupos no dieron ninguna diferencia significativa en cuanto a la comparación de los cinco rasgos [la F (4,760)=0,55; p=0,696]. Había diferencias dentro de los rasgos de personalidad unidos a los diferentes niveles de uso de Internet [la F (4,760)=5,30; p=0,001]. De hecho, una prueba de la muestra mostró que los sujetos que tienen los niveles inferiores de uso de Internet puntúan más alto en la estabilidad emocional que en la apertura a nuevas experiencias [la t (93)=2,74; p=0,007], y los sujetos que tienen el nivel más alto de empleo puntúan más bajo en la estabilidad emocional que en la apertura a nuevas experiencias [la t (97)=3,28; p=0,001]. Los sujetos que tienen los niveles más altos de uso mostraron los niveles más altos de extroversión con respecto a la estabilidad emocional [la t (97)=2,78; p=0,006]. Finalmente los sujetos que tienen los niveles más altos de uso mostraron un nivel más alto de apertura a nuevas experiencias con respecto al rasgo amistad [la t (97)=2,50; p=0,014].

4. Discusión y conclusión

Los resultados han mostrado que un sujeto con altos niveles de uso de Internet tiene niveles más altos en la extroversión y en la apertura a nuevas experiencias. Estos resultados preliminares de la investigación ilustran el potencial de su uso para la educación y las ventajas que pueden derivarse de este uso. Las personas con altos niveles de extroversión son asertivas, enérgicas, activas, optimistas y excitables. El entusiasmo y el estímulo sensorial que buscan los extrovertidos los conducen a usar Internet para satisfacer sus necesidades emocionales y sociales. Por su parte, la apertura para experimentar describe la originalidad y la complejidad de la vida mental y empírica de un individuo y son caracterizadas por la actividad, la imaginación, la estética y la sensibilidad. El sujeto que muestra un nivel más alto podría usar Internet para satisfacer su necesidad de investigar y de mejorar su conocimiento. De hecho, según Correa (2010) era previsible la relación positiva entre la apertura a experiencias y el empleo de medios de comunicación social que se ha encontrado en este estudio, dada la naturaleza de estas nuevas tecnologías.

Por lo tanto, se puede explicar por qué las personas extrovertidas, más que las introvertidas, tienden a tener adicción en el empleo de medios de comunicación social. Estos resultados son compatibles con los estudios de otros autores que exploraron la relación entre los rasgos de personalidad y Facebook y el empleo de medios de comunicación social (Correa & al., 2010). El dato sugiere que, vista la influencia de estos medios de comunicación social sobre interacciones sociales de hoy –más de la mitad de los adolescentes de América y de los adultos jóvenes los utilizan y más de un tercio de todos los usuarios de la web tienen adicción a estas actividades–, los diseñadores de Internet deben tener en cuenta las características y las necesidades de los usuarios (Hamburger & Ben-Artzi, 2000). La misma conclusión se podría trasladar al contexto de la escuela en lo que se refiere a la programación de los contenidos educativos. Las redes sociales pueden ser un recurso importante para la enseñanza de los profesores y para el estudio del alumnado al formar parte de un proceso deliberado y racional que puede ser localizado y desarrollado dentro de contextos diferentes y del conocimiento operacional. Los resultados de esta investigación indican que el empleo de Internet podría proporcionar la oportunidad de mejorar los resultados de una educación que usa la tecnología con la que los estudiantes están ya familiarizados, sobre todo en la creación de una disposición favorable al estudio en el entorno de la escuela al usar los recursos disponibles en contextos informales (Costa & al., 2013).

Correa et al. (2010) sostienen que la gente adulta que está dispuesta a abrirse a las nuevas experiencias con mayor probabilidad desarrollará una adicción al uso de medios de comunicación social, mientras que el hecho de que las generaciones jóvenes usen Internet como un instrumento de comunicación social tiene que ver más con la extroversión. La gente más joven ha crecido con estas opciones digitales a su disposición para relacionarse y comunicarse, lo que la convierte en nativos digitales (Prensky, 2001) que a menudo muestran mejores habilidades en la utilización de las tecnologías digitales que sus profesores. Si los profesores usaran en el contexto de la escuela los mismos instrumentos que los estudiantes suelen utilizar para comunicarse se podrían identificar las mejores soluciones que les ayudaran a enseñar mejor y a amoldar su enseñanza a las características de los estudiantes, optimizando aquellas variables que constituyen el motor del aprendizaje (la emotividad) y estimulando habilidades de carácter más elevado (la toma de conciencia y la liberalidad), y a encontrar nuevas formas de alfabetización múltiple. Los autores de este estudio trabajan en esta dirección con una serie de iniciativas de investigación que reúnen el aislamiento de variables significativas en el ajuste informal para verificar los efectos en el contexto formal (Costa & al., 2013) y la relación entre competencia digital y multialfabetización (Nuzzaci, 2011; 2012).

Esta investigación tiene sus raíces en el marco teórico que sostiene que el uso de Internet va más allá del estudio informal e incluye el empleo de información de una manera crítica o analítica, la construcción de una mente abierta y la actitud independiente. La tecnología es una parte integrada de la educación actual y por esta razón la futura investigación debería enfocar la evaluación sobre cómo los estudiantes usan la tecnología como instrumentos capaces de pensar para buscar, producir, manejar, analizar, y compartir el conocimiento así como para solucionar problemas complejos individual y colaborativamente (Häkkinen & Hämäläinen, 2012). Los numerosos estudiosos han argumentado que la utilización de tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC) en actividades de lectura tradicionales en papel pueden maximizar la comprensión de lectura de los estudiantes en un ajuste de estudio apoyado por la tecnología (Chen, Kinshuk, Wei & Yang, 2008; Grasset, Dunser & Billignhurst, 2008). Esta experiencia promueve el pensamiento crítico y la comunicación, aunque tal impacto tiene que ser apoyado por hipótesis bien documentadas ya que los efectos condicionales son relativamente desconocidos.

La combinación de la información digital con objetos físicos es una tendencia en la educación, que permite a los estudiantes usar la tecnología en el aula (Huang, Wu & Chen, 2012). Además, Barron (2006) subraya el interés de un autoaprendizaje que posteriormente se deja guiar, y que se produce gracias a la combinación entre los estudios formales e informales. Por esta razón, los grandes entornos que se apoyan en ordenadores colaborativos pueden verse como elementos esenciales en la reestructuración de la interacción social y la creación de conocimiento (Häkkinen & Hämäläinen, 2012).

Quedan todavía algunas hipótesis por resolver que requieren nuevos datos:

• Hipótesis 1: Un uso selectivo y que cuenta la sensibilidad de todos promueve la integración de todos los sujetos y grupos escolares.

• Hipótesis 2: Elevar los estándares de rendimiento en el uso de Internet, debido a un alto rendimiento en los individuos, promueve el pensamiento crítico de todos los sujetos y grupos escolares.

• Hipótesis 3: Elevar los estándares de rendimiento en el uso de Internet debido a los altos niveles de rendimiento de los docentes que promueve el pensamiento crítico de todos los sujetos y grupos escolares.

• Hipótesis 4: Elevar los estándares de rendimiento en el uso de Internet promueve la toma de conciencia en todos los individuos y grupos.

• Hipótesis 5: Elevar los estándares de rendimiento en el uso de Internet promueve el pensamiento crítico.

• Hipótesis 6: Mejorar los estándares de rendimiento en el uso de Internet fomenta las aspiraciones en todos los sujetos y grupos.

La presente contribución sugiere vías para futuras investigaciones que mejoren el entendimiento sobre si el cambio en la naturaleza de las variables en su empleo conduce a resultados diferentes para los diferentes grupos de sujetos según sus características personales. Además, con el fin de examinar de forma exhaustiva la relación entre las características personales y las interacciones, también convendría tener en consideración las variables del rendimiento educativo y del sexo. En este sentido, se requieren nuevas investigaciones y utilizar otros instrumentos para determinar si las relaciones son significativamente diferentes para los subgrupos de estudiantes. Es interesante comprobar cómo los diferentes tipos de uso de Internet están relacionados con pequeñas mejoras en la apreciación cultural y en la conciencia social. Otras investigaciones muestran un impacto en el rendimiento de los estudiantes. Los resultados sacan a la luz que los estudiantes que la usan de forma más selectiva y consciente poseen niveles más altos de destreza y tienden a aspirar a grados más avanzados. Esta investigación aclara los elementos que actúan como un telón de fondo en la relación entre el aprendizaje producido en contextos informales y formales, lo que ayuda a entender cómo construir nuevas formas de alfabetización. Esto se relaciona con la valoración de la cultura y la conciencia social que representan factores de vital importancia para la mejora de los perfiles culturales de la población.

==

Referencias

Amichai-Hamburger, Y. & Ben-Artzi, E. (2003). Loneliness and Internet Use. Computers in Human Behavior, 19 (1), 71-80. (DOI: 10.1016/S0747-5632(02)00014-6).

Barbaranelli, C. & Caprara, G.V. (2000). Measuring the Big five in Self Report and Other Ratings: A Multitrait-multimethod Study. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 16 (1), 31-43. (DOI: 10.1027//1015-5759.16.1.31).

Barron, B. (2006). Interest and Self-sustained Learning as Catalysts of Development: A Learning Ecologies Perspective. Human Development, 49 (4), 193-224. (DOI: 10.1159/000094368).

Bearne, E. (2003). Rethinking Literacy: Communication, Representation and Text. Literacy, 37 (3), 98-103. (DOI: 10.1046/j.0034-0472.2003.03703002.x).

Bei, L-T, Chen, E.Y.I. & Widdows, R. (2004). Consumers’ Online Information Search Behavior and the Phenomenon of Search and Experience Products. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 25 (4), 449-467. (DOI: 10.1007/s10834-004-5490-0).

Caprara, G.V., Barbaranelli, C. & Borgogni, L. (1993). BFQ: Big Five Questionnaire. Firenze: OS, Organizzazioni Speciali.

Casero-Ripollés, A. (2012). Beyond Newspapers: News Consumption among Young People in the Digital Era. Comunicar, 20 (39), 151-158. (DOI: 10.3916/C39-2012-03-05).

Chen, N.S., Kinshuk, Wei, C.W. & Yang, S.J.H. (2008). Designing a Self-contained Group Area Network for Ubiquitous Learning. Educational Technology & Society, 11(2), 16-26.

Chen, Y.F. & Peng, S.S. (2008). University Students’ Internet Use and its Relationships with Academic Performance, Interpersonal Relationships, Psychosocial Adjustment, and Self-evaluation. Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 11 (4), 467-469. (DOI: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0128).

Coiro, J. (2003a). Reading Comprehension on the Internet: Expanding our Understanding of Reading Comprehension to Encompass New Literacies. The Reading Teacher, 56(5), 458-464.

Coiro, J. (2003b). Rethinking Comprehension Strategies to Better Prepare Students for Critically Evaluating Content on the Internet. The NERA Journal, 39 (2), 29-34.

Cope, B. & Kalantzis, M. (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures. South Melbourne: Macmillan.

Correa, T., Hinsley, A.W. & De-Zúñiga, H.G. (2010). Who Interacts on the Web?: The Intersection of Users’ Personality and Social Media Use. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 247-253. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2009.09.003).

Costa Jr, P.T. & McCrae, R.R. (1992). Four Ways Five Factors Are Basic. Personality and Individual Differences, 13 (6), 653-665. (DOI: 10.1016/0191-8869(92)90236-I).

Costa, S., Cuzzocrea, F., La Vecchia, L., Murdaca, A.M. & Nuzzaci, A. (2013). A Study on the Use of Facebook in Informal Learning Contexts: What are the Prospects for Formal Contexts? International Journal of Digital Literacy and Digital Competence (IJDLDC), 4 (1), 1-11. (DOI: 10.4018/jdldc.2013010101).

Cuzzocrea, F., Murdaca, A., Oliva P. (2011). Using Precision Teaching Software to Improve Foreign Language and Cognitive Skills in University Students. International Journal of Digital Literacy and Digital Competence, 2 (4), 50-60. (DOI: 10.4018/978-1-4666-2943-1.ch014).

Downes, T. & Zammit, K. (2001). New Literacies for Connected Learning in Global Classrooms. A Framework for the Future. In P. Hogenbirk & H. Taylor (Eds.), the Bookmark of the School of the Future (113-128). Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Eco, U. (1975). Trattato di semiotica generale. Milano: Bompiani.

Erjavec, K. (2013). Informal Learning through Facebook among Slovenian Pupils. Comunicar, 21 (40), 607-611 (DOI: 10.3916/C41-2013-11).

Freeman, M.F. & Tukey, J.W. (1950). Transformations Related to the Angular and the Square Root. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 21 (4), 607-611. (DOI: 10.1214/aoms/1177729756).

Garton, J. (1997). New Genres and New Literacies: The Challenge of the Virtual Curriculum. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 20 (3), 209-221.

Gibbons, P. (2002). Scaffolding Language, Scaffolding Learning: Teaching Second Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom. Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Grasset, R., Dunser, A. & Billignhurst, M. (2008). The Design of a Mixed-reality Book: is it Still a Real Book? In Proceedings of the 2008 7th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (Ismar ’08) (pp. 99-102).

Hamburger, Y.A. & Ben-Artzi, E. (2000). The Relationship between Extraversion and Neuroticism and the Different Uses of the Internet. Computers in Human Behavior, 16 (4), 441-449. (DOI: 10.1016/S0747-5632(00)00017-0).

Huang, H.W., Wu, C.W. & Chen, N.S. (2012). The Effectiveness of Using Procedural Scaffoldings in a Paper-plus-smartphone Collaborative Learning Context. Computers & Education, 59 (2), 250-259. (DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.01.015).

Häkkinen, P. & Hämäläinen, R. (2012). Shared and Personal Learning Spaces: Challenges for Pedagogical Design. The Internet and Higher Education, 15 (4), 231-236. (DOI: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.09.001).

Kabilan, M. & Rajab, B. (2010). The Utilisation of the Internet by Palestinian English Language Teachers Focusing on Uses, Practices and Barriers and Overall Contribution to Professional Development. International Journal of Education and Development Using ICT, 6 (3), 56-72.

Keller, H. & Karau, S.J. (2013). The Importance of Personality in Students’ Perceptions of the Online Learning Experience. Computers in Human Behavior, 29 (6), 2494-2500. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.06.007).

Kuh, G.D. & Hu, S. (2001). The Effects of Student-faculty Interaction in the 1990s. The Review of Higher Education, 24 (3), 309-332. (DOI: 10.1353/rhe.2001.0005).

Kumar, M.M. & Karapudi, B. (2012). Students’ Insight on Internet Usage: A Study. SRELS Journal of Information Management, 49 (3), 331-339.

Landers, R.N. & Lounsbury, J.W. (2006). An Investigation of Big Five and Narrow Personality Traits in Relation to Internet Usage. Computers in Human Behavior, 22 (2), 283-293. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2004.06.001).

Leu, D.J., JR., Kinzer, C.K., Coiro, J. & Cammack, D.W. (2004). Toward a Theory of New Literacies Emerging from the Internet and Other Information and Communication Technologies. In R.B. Ruddell & N. Unrau (Eds.), Theoretical Models and Processes of Reading (pp. 1570-1613). Newark: International Reading Association.

Leung, L. (2003). Impacts of Net-generation attributes, Seductive Properties of the Internet, and Gratifications-obtained on Internet Use. Telematics and Informatics, 20 (2), 107-129. (DOI: 10.1016/S0736-5853(02)00019-9).

McKenna, K.Y.A., Green, A.S. & Gleason, M.J. (2002). Relationship Formation on the Internet: What’s the Big Attraction? Journal of Social Issues, 58 (1), 9-32. (DOI: 10.1111/1540-4560.00246).

Murdaca A., Cuzzocrea F., Conti F. & Larcan R. (2011). Evaluation of Internet Use and Personality Characteristics. REM - Research on Education and Media, 3(2), 75-93.

New London Group (Ed.) (2000). A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures (pp. 9-38). South Melbourne: Macmillan.

Nuzzaci, A. & La Vecchia, L. (2012). A Smart University for a Smart City. International Journal of Digital Literacy and Digital Competence (IJDLDC), 3 (4), 16-32. (DOI: 10.4018/jdldc.2012100102).

Nuzzaci, A. (2012). The «Technological good» in the Multiliteracies Processes of Teachers and Students. International Journal of Digital Literacy and Digital Competence, 3 (3), 12-26. (DOI: 10.4018/jdldc.2012070102).

Nuzzaci, A. (2013). The Use of Facebook in Informal Contexts: What Implication does it have for Formal Contexts? In Convegno SIREM 2013, ICT in Higher Education and Lifelong Learning, Bari, 14-15 Novembre 2013, Università degli Studi di Bari.

Nuzzaci, A. (Ed.) (2011). Patrimoni culturali, educazioni, territori: verso un’idea di multiliteracy. Lecce: Pensa Multimedia.

Peterson, R.A. & Merino, M.C. (2003). Consumer Information Search Behaviour and the Internet. Psychology & Marketing, 20 (2), 99-121. (DOI: 10.1002/mar.10062).

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, Digital Immigrants part 1. On the horizon, 9 (5), 1-6.

Roberts, D.F., Foehr, U.G. & Rideout, V.J. (2005). Generation M: Media in the lives of 8-18 year-olds. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. January 2010. (http://goo.gl/bu2d3y).

Salomon, G. (1994). Interaction of Media, Cognition and Learning. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Soengas, X. (2013). The Role of the Internet and Social Networks in the Arab Uprisings. An Alternative to Official Press Censorship. Comunicar, Scientific Journal of Media Education, 21(41), 147-155 (DOI: 10.3916/C41-2013-14).

Student Monitor (2003). Computing & the Internet: Fall 2002. Ridgewood: Author.

Sturken, M. & Cartwright, L. (2001). Practices of Looking: Images, Power, and Politics & Viewers Make Meaning. Oxford-NewYork: Oxford University Press.

Tejedor, S. & Pulido, C. (2012). Challenges and Risks of Internet Use by Children. How to Empower Minors? Comunicar, 20 (39), 65-72 (DOI: 10.3916/C39-2012-02-06).

Tosun, L.P. & Lajunen, T. (2010). Does Internet Use Reflect your Personality? Relationship between Eysenck’s Personality Dimensions and Internet Use. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(2), 162-167. (DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2009.10.010).

Turkle, S. (1995). Life on the Screen. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Young, K.S. (1998). Internet Addiction: The Emergence of a New Clinical Disorder. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 1 (3), 237-244. (DOI: 10.1089/cpb.1998.1.237).

Document information

Published on 30/06/14

Accepted on 30/06/14

Submitted on 30/06/14

Volume 22, Issue 2, 2014

DOI: 10.3916/C43-2014-16

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?