Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This audience study explores how a group of children from Southeast Mexico, perceive the animated cartoon «Dexter’s Laboratory». The objective is to observe the ways in which a young local audience, still in the process of building its cultural identity, perceives an American television program. A qualitative approach was applied: 44 children between 8 and 11 years old participated in a series of semi-structured interviews and focus groups, which took place in a provincial city in Mexico (Villahermosa, Tabasco). In each session, the participants watched an episode of the cartoon dubbed into Latin Spanish. Afterwards, it was assessed if they were able to notice cultural elements present in the series (texts in English, traditions, ways of life, symbols, etc.), which are different from their own culture. It was also observed if age, gender and social background had any impact on the degree of awareness. The results showed that most of the participants were aware of beingthat they were watching a foreign program, that they could recognize elements of American culture and that they applied diverse strategies to make sense of these foreign narratives. Older children, and those studying English as a second language, were able to make more sophisticated comparisons between the cultures of Mexico and the United States.

1. Introduction and background

Animation is one of the most expensive and difficult to produce television genres. Hence, only a few countries in the world have the expertise to create it, while the rest have to import it (Martell, 2011). Among the countries producing animation, the most salient are the United States of America and Japan, which have developed two important traditions: animated «cartoons» and «anime» (Napier, 2001). As a consequence, the majority of the animated series available worldwide reflect the ways of life, traditions and values of these two countries.

As a technique of audio-visual creation, animation can tell any kind of story (horror, romance, pornography, suspense, action, etc.), and thus, it can reach audiences of any age. However, traditionally the youngest viewers have been the most attracted to animated cartoons, especially comedy or adventures, to the point that they prefer them above any other kind of television program.

In Mexico, where production of animation is scarce, the majority of the animated series broadcasted on television are imports. In fact, animation is one of the genres, along with films and fiction series, for which there is a strong American dominance (Lozano, 2008). This means that Mexican children devote a good part of their leisure time to watching these animated cartoons, which show different realities from the ones they experience in their daily life. The first example of such differences that comes to mind is the representation of the scholastic routines of the animated characters: these attend schools that not only look different (with long corridors lined up with lockers in the case of American cartoons), but which also show different social routines (in anime, pupils change their regular shoes for slippers when they enter the classrooms).

Two questions emerge from observing this situation: a) are children able to identify that they are watching a program created in another culture? and b) which strategies do they use to deal with the foreign cultural references they find in the program?

Their popularity among children and the fact that the market is dominated by two nations, make animated series a unique case for studying how local audiences perceive television messages of international reach.

All television programs, when imported, have to pass a «localisation» process (Chalaby, 2002) to make them more understandable and likeable for the new audiences. Still, this does not mean that the programs will lose all of their cultural specificity, since they contain references to the lifestyle, landscapes, values, humour, traditions and even stereotypes of the country of origin.

Generally, animated series are adapted through dubbing, which implies the substitution of the original soundtrack for a new one in the target language (Kilborn, 1993). Besides the dialogues, we often find that dubbing also applies to songs and to the written signs that appear in the program. The most elaborated dubbing examples are achievements in translation, since they can include local accents, traditional sayings, popular expressions and even references to famous characters from the importing country (Cobos, 2010). But even such elaborated dubbing cannot change the visuals or the story of the programs. Within these translation gaps, specific cultural references remain, which the young viewers have to deal with if they are to make sense of the narrative.

Hence, it is relevant to ask how children perceive imported animated series. First, in order to know whether they can identify these cartoons as something different from their own culture and second, to explore how they make sense of the foreign cultural references found in these programs.

The review of the literature reveals that there is a scarcity of empirical research on the understanding that children have of animated programs of foreign origin. In particular, little is known about the strategies that they use to understand animated cartoons that have been adapted through dubbing.

Although the complex relationship between children and television has been amply studied from a variety of perspectives, there are just a few research works that have directly studied the way in which children understand foreign animated cartoons (among others, Corona, 1989; Charles, 1989; Moran & Chung, 2003; Amaral, 2005; Donald, 2005). In this sense, this work aims to contribute to a field of research that is still under development.

The main objective of this study is to ascertain if a group of Mexican children between the ages of 8 and 11 are able to identify that the animated cartoons they watch are foreign. A second goal is to identify the mechanisms these young members of the audience use to understand the references to American culture that appear in the series «Dexter’s Laboratory» (produced by Cartoon Network). Finally, the third objective is to evaluate if this understanding could be affected by factors such as age, gender or social class. The publication of these results is pertinent because of the prevalence of the assumptions that originated the research: a) the Japanese and American dominance in the Mexican market for animation, b) the preference that children in these age groups show for animated cartoons, and c) the limitations of dubbing in order to adapt the cultural references included in the programs. Thus, the specific relationship that becomes established between the American cartoons and Mexican children continues to exist, with the mediating action of dubbing.

2. Research methods

As it has been explained before, the objective was to explore how a group of children from a provincial city in Southeast Mexico understood American animated cartoons that have been translated through dubbing. Specifically, the aim was to observe whether the participants were able to recognise that the series was foreign, and to identify which were the mechanisms they put at play to make sense of media products created outside of their own culture.

For the empirical work, a qualitative approach was chosen, following the main tradition of international studies on television audiences (Ang, 1985; Liebes & Katz, 1990; Kraidy, 1999; Pertierra, 2012). Qualitative techniques, such as semi-structured interviews and focus groups, do not limit the respondents to a pre-determined set of answers, but can nevertheless offer a clear vision of the situation in which these children watch television.

Therefore, the results obtained in this manner should not be generalized to the whole population, but should be understood as insights about the meanings that a specific community is creating out of a given cultural product. In this particular case, they would make it possible to obtain a clearer idea about the ways in which these children perceive the cultural references that remain in this American animated series, even after dubbing.

The fieldwork consisted of six sessions of semi-structured interviews and six focus groups, which took place during the months of December 2004 and January 2005 in the city of Villahermosa, Tabasco, Mexico. The interviews were conducted in the children’s homes, which allowed for the observation of the daily context where the social practice of television viewing took place. Half of the focus groups’ sessions took place in a public elementary school, while the other half took place in a private one. In Mexico, the type of school a child attends marks in a clear way the belonging to a given social class due to the high cost of tuition in private institutions.

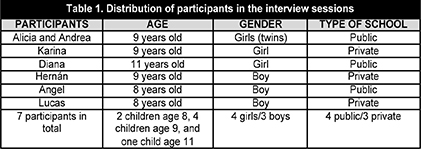

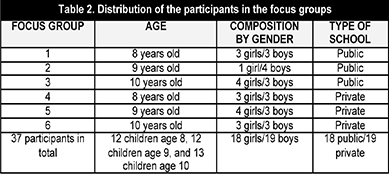

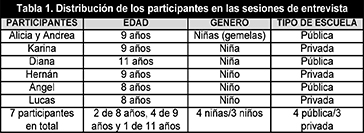

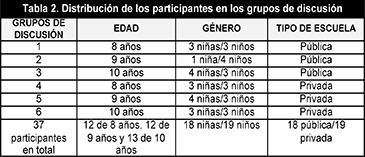

A total of 44 children participated in the research project: 7 of them in the interviews (a pair of twin girls took part in a single session) and 37 in the focus groups. Plenty of attention was given in order to ensure that the groups were equally divided by age and gender. Likewise, we sought participants that belonged to a variety of social strata, which in a certain way was determined by their attendance to public or private schools (Tables 1 and 2). An exact proportion was not achieved in every case, but the qualitative outlook of the study allowed for a certain amount of flexibility in this regard.

The age of the participants was within the range of 8 to 11 because these children are already capable of clearly understanding the narrative codes of television (Josephson, 1995; Anderson, 2004). Also, working with children this age ensures that all of them are able to read the written texts that usually appear in animated cartoons, as those signs cannot always be translated and remain in the original language.

In the case of the interviews, due to the difficulty of obtaining access to the homes of young children to carry on observations, the participants were recruited through acquaintances and relatives of the researcher. The participants in the focus groups volunteered at their schools. In every case, the researcher obtained consent from the children as well as informed consent signed by the parents. Pseudonyms were used to ensure confidentiality.

The animated series «Dexter’s Laboratory» was selected as the case study because of three main reasons: a) at the time, the series was available in Mexico both on over the air and paid television; b) it was dubbed in Latin American Spanish; c) it was very popular among the young Mexican television viewers (IBOPE, 2005). All of these characteristics made it accessible for the children who participated in the study, without distinction of age, gender or social class. An important additional reason was that the series, being set in contemporary United States, displayed the lifestyle of a typical American family.

The series tells the story of a boy genius named Dexter and of his sister DeeDee, who live with their parents in a house in the suburbs. There is a strong element of fantasy and science fiction in the narrative but there are also typical situations that show American culture. Besides Dexter’s adventures, there are also short stories of a group of superheroes led by Major Glory (Mayor America in Spanish) in the series. The presence of all these elements was crucial to enable the discussion about aspects related to cultural differences.

Each of the interview sessions and discussion groups was divided into three parts: for the first 20 minutes the children watched an episode from the animated series, which had been recently recorded from the daily television broadcast. The viewing phase allowed the researcher to observe the reactions of the children while watching the program, as well as to gather spontaneous comments. Afterwards, the participants were asked to tell the main story of the episode. The discussion that followed was structured in a flexible way around a series of topics: it started by asking the participants their opinion about the series, then they were asked where they thought the character lived and where the series was produced; they were also asked to compare their own life with the life of the protagonist, and then slowly the discussion moved to questions concerning the American cultural references contained in the episodes, such as written signs in English, locales and places typical of the American cities, monuments, symbols, etc. Both the focus groups and the interviews were videotaped and field notes were taken. The interviews were transcribed in full. Transcription of the focus groups was partial, due to the large amount of data and the level of overlap of the participants’ interventions. However, the video recordings from these sessions were carefully analysed in order to take into account the answers in the most faithful manner possible.

The information obtained from the fieldwork was codified according to categories of analysis. Since the interest of the study was very specific, some of the categories had been established a priori and were already included in the guide of topics used to structure the sessions (e.g. understanding of the narrative, identification of the origin of animated cartoons, comparison between the life of the character and their own life, etc.). Other categories emerged directly from the answers that children offered, as well as from the field notes (e.g. violent cartoons, negotiation of foreign content through local referents, awareness of dubbing conventions, etc.).

3. Analysis and results

The first result derived from the fieldwork is that all the participants were able to understand and correctly tell the basic story of the episode. In this sense, there were no visible differences in terms of age, gender or social class of the respondents. The participants showed a good understanding of humour as well, which is one of the elements that is regularly lost or diminished in translation. This could be explained in part because a high percentage of comedy in cartoons is visual.

When their opinion on animated cartoons was asked, children mentioned the parts that they liked and those they disliked the most. From this question, it became clear that a majority of the participants were already acquainted with the characters and the basic themes in the series. Not only did they remember the main argument and specific moments of the episode, but they also mentioned many other scenes, characters and recurrent jokes in the series, which they had seen on their own televisions. Hence, the availability of «Dexter’s Laboratory» to its audience was confirmed, as well as the popularity of animated cartoons in general, since the participants also named many other titles of both American and Japanese origins.

Immediately afterwards, the children compared what the saw in the animated cartoons with what they experienced in their own lives. Mostly, they focused on tangible things that surrounded them, such as the shape of the houses they saw in the series and their own houses. Many other children also compared the protagonist’s family with their own family, talking about the anatomy of the characters, the parents’ occupation and sibling rivalry. In this sense, age seems to be a determinant factor as 10-year-old children, from both the public and private schools, made more sophisticated comparisons. In fact, the 10-year-old participants of the focus group from the private school talked about Mexican and American lifestyles. After they had agreed that Dexter lived in the United States, they were asked how they knew this.

The answer came from two boys (Calvin and Armando) and a girl (Ari): «Calvin: Because of the American lifestyle; Researcher: How is the American lifestyle? Calvin: Well, a house with their family, only for themselves; Armando: And also they are always two-storey houses; Calvin: Yes, and a school with lockers, which are very rare here in Mexico; Armando: And that they go [to school] with everyday clothes; Calvin: With pants, everyday clothes, yes; Ari: And the public schools [in the United States] are like the private ones [in Mexico], only that the private ones [in the United States] are much more expensive.» In this dialogue, the participants show they are able to compare elements of their daily life with what they watch onscreen, even in the case of a genre like animation, which could be considered incredible.

The next category of analysis was the place where Dexter lived. Most of the children, both in the interviews and the focus groups, responded that the character lived in the United States. They said that they had reached this conclusion because they had seen the character Major Glory, a superhero that wears the American flag as his uniform. The 10-year-old children in the focus groups, both in the public and private schools, were so sure that Dexter lived in the United States that they even tried guessing the exact setting of the series, saying that it could be Washington or New York City. On the other hand, a minority of children (one 8-year-old boy from the public school, five 9-year-olds from the public school and one 9-year-old boy from the private school) said that Dexter lived in the capital of their own country, that is, in Mexico City. As the reason for this conclusion, one of them mentioned that it was «because most of the characters [on television] live there». Somehow, the children, from a provincial city, see the capital as the centre of many things in the country, and particularly for television production.

When the participants were asked if they knew where the series «Dexter’s Laboratory» was produced, once again the older children in general, and those that attended the private school in particular, were able to say that the program was produced in the United States. Among the reasons they mentioned to reach such conclusions were: a) the opening title and the closing credits of the program are in English; b) Major Glory’s uniform displays the American flag; c) they had seen a special program about the production of the series on the cable/satellite channel Cartoon Network. One 8-year-old from the public school mentioned that he was sure the program was made in the United States because he had read it on the Internet. Similarly, a 9-year-old from the private school specified that it was produced in the United States «but it is translated here [in Mexico] ». Only the 9-year-old children group from the public school said that the series was produced in Mexico City, but they did not offer any reasons to justify this idea.

Following the logic of the previous question, the children discussed how it was possible to recognize the origins of animated cartoons. The participants coming from all social classes and ages were accurate in describing the differences between American and Japanese animated series, even from an aesthetic point of view (they said, for example, that the characters in Japanese programs have huge bright eyes). Interestingly, mirroring a common opinion among parents at the time, some children said that Japanese cartoons could be recognized because they were violent (this was clearly expressed by a 10-year-old boy from the private school: «The most bloody ones come from Japan, such as «Jackie Chan», «Dragon Ball Z», «The Ninja Turtles»). Likewise, a couple of children said that the written signs that appear in the programs are good indicators of the cartoon’s origin. At this point, the children were asked to explain what they usually do when they see written signs in English in the animated cartoons. Most of them, without distinction in age or social origin, said that when they see a sign that is written in another language, they wait for a voice to «announce» what it means (this would be a dubbing convention). A minority of the participants, all of them from the private school, explained that they read the written texts because they could already understand their meaning in English, for they study the language as a mandatory subject at school. Elementary public schools in Mexico, on the other hand, do not offer teaching of the English language. However, the twin girls interviewed (9-years-old), who attended a public school, said that when they see an unknown word in the title of a cartoon they look for the meaning in the bilingual dictionary. Another 8-year-old boy from the public school explained that regarding the signs written in English, he would ask his father: «I never understand a thing. I ask my dad: what does that mean? And he does not understand a thing either. The one who understands is my uncle, because he knows English…». All of these seem to be common mechanisms among these children to try to understand the foreign cultural references.

Besides the participants’ answers, it was also possible to take note of their reactions while they watched the episode. From there came the observation that they understand the narrative in a quite adequate way. 10-year-old participants from the private school even recognized the image of Albert Einstein in one of the shorts. Also, there was a curious moment of negotiation of meanings, when the 9-year-old boy interviewed (private school), seeing the image of a cowboy riding in a black and white scene, identified him with the Mexican «revolucionario» Emiliano Zapata. Thus, he used a local reference to make sense of something that came from outside his own culture.

4. Discussion and conclusions

Observing these children watching television confirmed what had theoretically been sustained, in the sense that these are viewers that created meanings socially-within their interpretive communities (Orozco, 1990; 1994; Seiter, 1998): while they were watching the episodes recorded for the sessions they commented with their peers, brothers or sisters, made observations, criticized, and asked about what they could not understand.

Complementary, these children were not only an active audience in an ideological sense, as Stuart Hall understood it (2001), but also an audience that was physically active while watching television (Palmer, 1986). During the interviews at their homes, they would entertain themselves in different activities while watching television, such as playing with their toys, eating candy, hugging their stuffed animals, finding the best spot on their beds or sofas, or even teasing their siblings. Also, it was observed that these children had clear categories for what is good and bad, realistic or not realistic in television programs and that they knew what to expect from different genres. In fact, it was possible to infer from their answers that they had specialized knowledge about animated cartoons, which constitute an important part of their daily cultural consumption, along with videogames, films, comic books, etc. (Kinder, 1991).

In regard to the specific focus of this work, all of the participants were able to follow the narrative of the American animated cartoons and they were able to understand the humour. There were not differences related to gender, since both girls and boys showed equal understanding. Age, on the other hand, seemed to be an influential factor, for older children made more sophisticated comparisons regarding their own lives and the elements they watched on the program. Also, children attending the private school were able to talk in a more abstract manner about Mexican and American lifestyles. The facts that these children were more familiar with the English language and that many of them had travelled abroad seemed to play a relevant role in this respect.

Regarding the notions they had about the places portrayed in the animated cartoons, and the place of production of the show, the participants as a group still expressed a certain level of ambiguity. For some of them, Mexico City, as a different and far removed place from their province, was an important point of reference. In fact, it was obvious that for older children and for those belonging to a higher social class, it was clearer that the program was specifically American. They recognized the origin because of the title and credit sequences in English, as well as for some specifically American cultural traits of the characters.

The discussion on the ways these children recognized the origin of animated cartoons was very revealing, since they precisely described the aesthetic features of Japanese anime, and even expressed some of their judgements about it, such as the fact that it was considered violent.

Finally, it was possible to identify some of the mechanisms that these children applied for the understanding of the cultural references coming from outside their own culture, above all the signs written in English that could not be modified or deleted from the visuals. At this point, the efficacy of dubbing as an adaptation method was confirmed, because all of the children interviewed knew that by convention a masculine voice («a man») must read out loud in Spanish what is written in English. This implies that from a very young age, these children are already aware that some television contents are translated. Nevertheless, regarding the interpretation of these written texts, there was a noticeable difference between younger and older children, because the older reported that they made the effort to ask their parents about the meaning of the words, or even directly searched for them in a bilingual dictionary. At the social class level, the children from the private school had an advantage, for they knew the English language, some of them had been in the United States, or they had relatives who lived in that country. All of this provided them with better first hand-knowledge of the American lifestyle. At this point, my interpretation coincides with the one proposed by La Pastina and Straubhaar (2005) regarding the perception of telenovelas in Brazil: cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1984) seems to be a relevant factor that guides the interpretation of media narratives, even at ages so early as the range studied here.

The implications of these results can neither be generalized to all Mexican children nor to all children from the same region where the study was conducted, due to the use of qualitative methods. In spite of that, many of the comments and observations show that these children are conscious about watching a message coming from a different culture. Apparently, the ability of the participants to differentiate their own reality from the one presented in a television program matures with age and is also related to cultural capital. The participants from the private school had a higher possibility of developing, from earlier on, a more complex conception of the world by learning English, through access to international channels on pay television and even by travelling to the United States, where they had personally seen the culture portrayed in American cartoons.

Television messages contribute to children’s education by showing them portrayals of the world; as a result, it is important to endorse the active consumption of television by children. In this study, although limited in scope but nevertheless clarifying, children appeared as curious and conscious television viewers. They revealed themselves as subjects that built their cultural identity from a multiplicity of stimuli (local, national and global), to which they had access to according to the socio-economic conditions in which they lived in. A new series of empirical observations would surely enrich the understanding of this phenomenon, especially if we take into account that children are adopting new technologies such as smartphones and tablets, which are privileged access points to local and foreign cultural referents.

Support and acknowledgment

This research was funded by a Fulbright-García Robles scholarship. Special thanks to the thesis supervisors, Dr. Michael Kackman and Dr. Joseph Straubhaar.

References

Amaral, E.S. (2005). Constructed Childhoods: A Study of Selected Animated Programmes for Children with Particular Reference for the Portuguese Case. (Tesis Doctoral). (http://goo.gl/1dXBf3) (26-04-2014).

Anderson, D.R. (2004). Watching Children Watch Television and the Creation of Blue’s Clues. In H. Hendershot (Ed.), Nickelodeon Nation: The History, Politics, and Economics of America’s only TV Channel for Kids. (pp. 387-434). New York: New York University Press.

Ang, I. (1985). Watching Dallas: Soap Opera and the Melodramatic Imagination. New York: Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Chalaby, J. (2002). Transnational Television in Europe: The Role of Pan-European Channels. European Journal of Communication, 17(2), 183-203.

Charles, M. (1989). La televisión y los niños. El reto de vencer al Capitán América. In E. Sánchez-Ruiz (Comp.), Teleadicción infantil, mito o realidad. (pp. 15-26). México: Universidad de Guadalajara.

Cobos, T.L. (2010). Animación japonesa y globalización: la latinización y la subcultura Otaku en América Latina. Razón y Palabra, 72. (http://goo.gl/N5AisY) (15-07-2014).

Cornelio-Marí, E.M. (2005). Mexican Children’s Perception of Cultural Specificity in American Cartoons. (Tesis de Maestría no publicada, The University of Texas at Austin).

Corona, S. (1989). El niño y la TV: una relación de doble apropiación. In E. Sánchez-Ruiz (Comp.), Teleadicción infantil, mito o realidad. (pp. 69-78). México: Universidad de Guadalajara.

Donald, S.H. (2005). Little Friends: Children’s Film and Media Culture in China. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Hall, S. (2001). Encoding/Decoding. In M.G. Durham, & D.M. Kellner (Eds.), Media and Cultural Studies: Key Works. (pp. 166-176). Maldern: Blackwell Publishers.

IBOPE (2005). IBOPE Network Ranking Multi-Country Report (Weighted Average of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru Survey Areas). Total Day Rating Among Cable Households (Average Monday-Sunday). (http://goo.gl/fHep7a) (26-04-2014).

Josephson, W.L. (1995). TV Violence: a Review of the Effects on Children at Different Ages. Ottawa: National Clearinghouse on Family Violence.

Kilborn, R. (1993). Speak my Language: Current Attitudes to Television Subtitling and Dubbing. Media, Culture and Society, 15, 641-660.

Kinder, M. (1991). Playing with Power in Movies, Television, and Video Games: from Muppet Babies to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kraidy, M. (1999). The Global, the Local and the Hybrid: a Native Ethnography of Glocalization. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 16, 456-473.

La Pastina, A., & Straubhaar, J. (2005). Multiples Proximities between TV Genres & Audiences: The Schism between Telenovelas Global Distribution and Local Consumption. Gazette: The International Journal for Communication Studies, 67(3), 271-288.

Liebes, T., & Katz, E. (1990). The Export of Meaning: Cross-Cultural Readings of Dallas. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lozano, J. (2008). Consumo y apropiación de cine y TV extranjeros por audiencias en América Latina. Comunicar, 15(30), 62-72.

Martel, F. (2011). Cultura Mainstream: cómo nacen los fenómenos de masas. (Trad. Núria Petit Fonserè). Madrid: Taurus.

Moran, K.C., & Chung, L.C. (2003). Creating an ‘Ambiguous’ Identity: the Role of International Mass Media in the Lives of Children. Second annual Global Fusion Conference, Austin, TX. October 2003.

Napier, S. J. (2001). Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. New York: Palgrave.

Orozco, G. (1990). El niño como televidente no nace, se hace. In M. Charles, & G. Orozco (Eds.), Educación para la recepción. (pp. 33-48). México: Trillas.

Orozco, G. (1994). Recepción televisiva y mediaciones: la construcción de estrategias para la audiencia. In G. Orozco (Ed.). Televidencia: perspectivas para el análisis de los procesos de recepción televisiva. (pp. 69-88). México D.F.: Universidad Iberoamericana.

Palmer, P. (1986). The Lively Audience: A study of Children around the TV Set. Sidney: Allen, & Unwin.

Pertierra, A. (2012). If They Show Prison Break in the United States on a Wednesday, by Thursday It Is Here: Mobile Media Networks in Twenty-First-Century Cuba. Television & New Media, 13(5), 399-414.

Seiter, E. (1998). Children’s Desires/Mother Dilemmas: The Social Context of Comsumption. In H. Jenkins (Ed.), The Children’s Culture Reader. (pp. 297-317). New York: New York University Press.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Este estudio sobre audiencias explora cómo un grupo de niños del sureste de México perciben los dibujos animados de «El laboratorio de Dexter». El objetivo primordial es conocer la manera en que un programa norteamericano distribuido internacionalmente es entendido por una audiencia local, especialmente por una conformada por individuos que aún están construyendo su identidad cultural. Se utilizó un enfoque cualitativo: un total de 44 niños en edades entre los 8 y 11 años participaron en una serie de entrevistas semi-estructuradas y grupos de discusión, que se llevaron a cabo en una ciudad de la provincia mexicana (Villahermosa, Tabasco). En cada sesión se observó un episodio de la serie animada doblada al español latino. Posteriormente, se evaluó si los participantes sabían que los dibujos animados eran norteamericanos y si notaban la presencia de elementos culturales diferentes respecto a su propia cultura (textos escritos en inglés, referencias a tradiciones, estilo de vida, símbolos, etc.). Asimismo, se indagó si la edad, el género y estrato social de proveniencia influían en esta percepción. Los resultados muestran que la mayoría de los participantes eran conscientes de estar viendo un programa extranjero, reconocían elementos de la cultura norteamericana y aplicaban diversas estrategias para crear sentido a estas narrativas. Niños mayores, y aquellos que estudian el idioma inglés, fueron capaces de realizar comparaciones más sofisticadas entre las culturas de México y Estados Unidos.

1. Introducción y estado de la cuestión

La animación es uno de los géneros televisivos más costosos y difíciles de producir. Debido a esto, solo unos cuantos países en el mundo tienen la capacidad de crearla, mientras el resto de las naciones deben importarla (Martel, 2011). Entre los países productores de animación los más destacados son los Estados Unidos de América y Japón, que han desarrollado a lo largo de la historia dos grandes tradiciones: los dibujos animados o «cartoon» y el «anime» (Napier, 2001). Como consecuencia, la mayor parte de las series animadas disponibles a nivel mundial cuentan historias que tienen como telón de fondo las culturas nipona y norteamericana; es decir, que reflejan el modo de vida, tradiciones y valores de estos dos países.

Como técnica de creación audiovisual, la animación es utilizada para narrar cualquier tipo de historia (horror, romance, pornografía, suspenso, acción, etc.), y en ese sentido puede dirigirse a públicos de todas las edades. Sin embargo, tradicionalmente han sido los más pequeños los que se ven atraídos por los dibujos animados, regularmente cómicos o de aventuras, al grado de preferirlos por encima de cualquier otro tipo de programa televisivo.

En México, donde la producción de animación para la televisión es escasa, la mayor parte de las series animadas que se transmiten son importadas. De hecho, este es uno de los géneros televisivos, junto con los filmes y las series de ficción, en el que existe un fuerte dominio norteamericano (Lozano, 2008). Esto quiere decir que los niños mexicanos dedican buena parte de su tiempo de ocio a seguir estos dibujos animados, que muestran realidades distintas a las que ellos viven diariamente. El primer ejemplo de estas diferencias que viene a la mente es la representación de las rutinas escolares de los personajes animados, que asisten a colegios que no solo se ven distintos (con casilleros y largos pasillos en el caso de los dibujos norteamericanos), sino que también muestran rutinas sociales distintas (en los animes, los niños cambian sus zapatos de calle por pantuflas para entrar al salón).

Frente a esta situación, surgen un par de preguntas: ¿son los niños capaces de identificar que están viendo un programa creado en otra cultura?, y ¿qué estrategias usan para interaccionar con las referencias culturales extranjeras que encuentran en el programa?

Su amplia popularidad entre los niños y el hecho de que el mercado esté dominado por un par de naciones provoca que las series animadas sean un caso único para estudiar la percepción de los mensajes televisivos de alcance internacional por parte de las audiencias locales.

Es cierto que todos los programas de televisión al ser importados tienen que pasar un proceso de «localización» (Chalaby, 2002) para hacerlos más comprensibles y agradables para las nuevas audiencias. Sin embargo, esto no significa que perderán toda su especificidad cultural, ya que retienen referencias al estilo de vida, los paisajes, los valores, el sentido del humor, las tradiciones e incluso los estereotipos del país de origen.

Generalmente, las series animadas son adaptadas por medio del doblaje, que implica la sustitución de la banda sonora original por una nueva realizada en el idioma de destino (Kilborn, 1993). Además de las voces, muchas veces se doblan también las canciones y se leen en voz alta los textos escritos (letreros) que aparecen. Los doblajes más elaborados son verdaderos prodigios de la traducción, pues logran incluir acentos locales, refranes, expresiones populares e incluso referencias a personajes famosos del país de destino (Cobos, 2010). Incluso estos doblajes elaborados no pueden cambiar la parte visual, ni la historia o la trama de la narrativa. En estos intersticios permanecen referencias culturales específicas al país de origen, con los que los jóvenes televidentes tienen que interaccionar para darle sentido a la narrativa.

Entonces, es válido preguntarse cómo perciben los niños estos dibujos animados para conocer si son capaces de identificarlos, en primer lugar, como algo distinto a su propia cultura y cómo encuentran sentido a las referencias culturales incluidas en ellos que les pueden resultar lejanas.

La revisión de literatura existente sobre el tema revela que existe una escasez de investigación empírica sobre la comprensión que los niños tienen de estos programas animados de origen extranjero. En particular, se conoce poco sobre las estrategias que utilizan para entender los dibujos animados que han sido adaptados a través del doblaje.

Aunque la compleja relación entre los niños y la televisión ha sido ampliamente estudiada desde variados puntos de vista, son escasos los estudios que tratan directamente la manera en que entienden los dibujos animados extranjeros (algunos ejemplos son los trabajos de: Corona, 1989; Charles, 1989; Moran & Chung, 2003; Amaral, 2005; Donald, 2005). En este sentido, este trabajo pretende contribuir a un campo de investigación aún en desarrollo.

El objetivo primordial es conocer si un grupo de niños mexicanos de edades entre los 8 y los 11 años son capaces de identificar si los dibujos animados que observan son extranjeros. De la misma manera, se pretende identificar los mecanismos que estos pequeños utilizan para entender las referencias a la cultura norteamericana que aparecen en la serie «El Laboratorio de Dexter» (producida por Cartoon Network). Finalmente, se pretende evaluar si esta comprensión puede ser afectada por factores como la edad, el género o el estrato social de pertenencia. La publicación de estos resultados es pertinente por la prevalencia de los supuestos que originaron la investigación: a) el dominio japonés y norteamericano en el mercado mexicano de la animación, b) la predilección de los niños de las edades estudiadas por los dibujos animados, y c) las limitaciones del doblaje para adaptar los referentes culturales presentes en los programas; es decir, la relación específica entre el niño mexicano y los dibujos animados norteamericanos que se buscaban explorar se sigue estableciendo con la acción mediadora del doblaje.

2. Método de la investigación

Como se ha dicho antes, se pretende explorar cómo un grupo niños de una ciudad provincial del Sureste de México comprenden los dibujos animados norteamericanos que han sido traducidos por doblaje. Específicamente, se observa si los participantes son capaces de identificar que la serie es extranjera, y se busca conocer cuáles son los mecanismos que ponen en juego para crear sentido a productos mediales creados fuera de su propia cultura.

Para el trabajo empírico se eligió un enfoque cualitativo, siguiendo la tradición principal de los estudios internacionales de las audiencias televisivas (Ang, 1985; Liebes & al., 1990; Kraidy, 1999; Pertierra, 2012). Técnicas cualitativas, como las entrevistas semi-estructuradas y los grupos de discusión, permiten obtener respuestas que no siguen un formato predefinido, pero que igualmente ofrecen una visión clara de la situación en que estos niños ven televisión. En este sentido, los resultados aquí obtenidos no deben ser generalizados a la población, sino entendidos como indicios que permiten vislumbrar los significados que una comunidad específica está creando de un producto cultural determinado. En este caso particular, se trata de tener una idea más clara de cómo estos niños perciben los rasgos culturales que persisten en esta serie animada norteamericana, aún después del doblaje.

El trabajo de campo consistió en seis sesiones de entrevista semi-estructurada y seis grupos de discusión, que tuvieron lugar en los meses de diciembre de 2004 y enero de 2005 en la ciudad de Villahermosa, Tabasco, México. Las entrevistas se realizaron en las viviendas de los niños, lo que permitió observar el contexto cotidiano donde se realiza la práctica social de ver televisión. En lo que se refiere a los grupos de discusión, la mitad de las sesiones se llevaron a cabo en una escuela primaria pública, mientras que la otra mitad en una escuela primaria privada. La razón de esta división es que, en México, el tipo de escuela a la que un niño asiste sirve para identificar de modo muy claro su pertenencia a un estrato social determinado, debido al costo elevado de las colegiaturas que se deben pagar en las instituciones de educación privadas.

Un total de 44 niños participaron en la investigación: siete de ellos en las entrevistas (porque en una sola sesión participaron un par de gemelas) y 37 en los grupos de discusión. Se puso mucha atención para asegurar que los grupos estuvieran divididos de forma equitativa por edad y género. Igualmente, se buscó que los participantes provinieran de una variedad de estratos sociales, lo que en cierta manera estaba determinado por su asistencia a escuelas públicas o de pago (tablas 1 y 2). No se logró una proporción exacta en todos los casos pero el carácter cualitativo del estudio permite una cierta flexibilidad en este sentido.

La edad de los participantes se ubicó dentro del rango de los 8 y los 11 años, debido a que estos niños ya son capaces de entender claramente los códigos narrativos de la televisión (Josephson, 1995; Anderson, 2004). Además, trabajar con niños de esta edad asegura que todos ellos ya son capaces de leer los textos escritos que aparecen usualmente en los dibujos animados, los cuales muchas veces no pueden ser traducidos y permanecen en el idioma original.

En el caso de las entrevistas, debido a la dificultad que conlleva obtener acceso a las viviendas de niños pequeños para realizar observaciones, los participantes fueron reclutados a través de conocidos y parientes de la investigadora. Los participantes de los grupos de discusión fueron niños que se ofrecieron como voluntarios en las escuelas. En todos los casos se obtuvo su asentimiento para participar, el consentimiento informado firmado por los padres y se garantizó el anonimato mediante el uso de seudónimos.

La serie animada «El laboratorio de Dexter» (Dexter’s Laboratory) fue seleccionada como caso de estudio por tres razones principales: a) en el momento en que se realizó el estudio estaba disponible en México tanto en televisión abierta como en sistemas de pago; b) la serie había sido doblada en español latino; c) era una serie muy popular entre los jóvenes televidentes mexicanos en ese momento (IBOPE, 2005). Todas estas características la hacían accesible para los niños que participaron en el estudio, sin distinción de edad, género o proveniencia social. Una importante razón adicional fue que esta serie, al estar ambientada en los Estados Unidos en la época contemporánea permitía ver el estilo de vida de una familia típica de aquel país.

La serie cuenta las aventuras de un niño genio de nombre Dexter y de su hermana DeeDee, que viven en una casa de los suburbios norteamericanos. Existe un fuerte elemento de fantasía y ciencia ficción en la narrativa, pero también se presentan situaciones típicas que muestran la cultura norteamericana. Aparte de las aventuras de Dexter, dentro de la serie se incluyen además historias breves de un grupo de superhéroes encabezados por el Mayor América. La presencia de todos estos elementos fue crucial para facilitar la discusión sobre aspectos de las diferencias culturales.

Cada una de las sesiones de entrevistas y grupos de discusión se dividió en tres partes: durante los primeros 20 minutos los niños observaron un episodio de los dibujos animados a analizar, el cual había sido grabado recientemente de la transmisión televisiva cotidiana. Esto permitió a la investigadora observar sus reacciones durante el programa y recoger comentarios espontáneos. Posteriormente, se pidió a los participantes que narraran el argumento principal del episodio. La discusión que siguió estuvo estructurada de manera flexible alrededor de una serie de temas: se inició por preguntarles su opinión de la serie, luego se les preguntó si sabían dónde vivía el personaje y dónde estaba producida la serie; se les pidió comparar su vida con la del protagonista de los dibujos animados y se llegó poco a poco a las cuestiones relativas a las referencias culturales norteamericanas que aparecían en el vídeo mostrado, como podrían ser letreros escritos en inglés, ambientes y lugares típicos de las ciudades estadounidenses, monumentos, símbolos, etc.

Tanto los grupos de discusión como las entrevistas fueron videograbadas y se tomaron notas de campo. Las entrevistas fueron transcritas en su totalidad. La transcripción de los grupos de discusión fue parcial, debido a la gran cantidad de datos y al nivel de las intervenciones de los participantes. Sin embargo, las videograbaciones de estas sesiones fueron analizadas cuidadosamente para tomar en cuenta las respuestas de los participantes de la manera más fiel posible.

La información obtenida del trabajo de campo se codificó de acuerdo a categorías de análisis. Como el interés del estudio es muy específico, algunas de dichas categorías habían sido establecidas a priori y formaban parte de la guía de temas que se utilizó para estructurar las sesiones (comprensión del relato, identificación del origen de los dibujos animados, comparación entre la vida del personaje y la propia, etc.). Otras emergieron directamente de las respuestas que los niños proporcionaron, así como de las notas de campo (dibujos animados violentos, negociación a través de referentes locales, conciencia de las convenciones del doblaje, etc.).

3. Análisis y resultados

El primer resultado que se derivó del trabajo de campo es que todos los participantes fueron capaces de entender y posteriormente narrar correctamente la historia básica del episodio que observaron. No se presentaron diferencias visibles en términos de edad, género y proveniencia social. Los participantes mostraron igualmente una buena comprensión del humor, que es uno de los elementos que regularmente se pierde o disminuye con la traducción. Esto último se debe en parte a que en los dibujos animados un alto porcentaje del humorismo es visual.

Cuando se les preguntó su opinión acerca de los dibujos animados, los niños mencionaron aquellas partes que les agradaban y aquellas que más les desagradaban. De esta pregunta resultó que una mayoría de los niños entrevistados estaban ya familiarizados con los personajes y los temas básicos que se presentaban en la serie. No solo recordaron el argumento principal y momentos específicos del episodio utilizado en la sesión, sino que también mencionaron muchas otras escenas, personajes y bromas recurrentes de la serie que habían visto por su cuenta en televisión. Se confirmó, por ello, la disponibilidad de «El laboratorio de Dexter» entre su audiencia, así como la popularidad de los programas animados en general, pues los participantes nombraron también muchos otros títulos norteamericanos y japoneses.

A continuación, los niños compararon lo que veían en los dibujos animados con sus propias vidas. Mayormente, se enfocaron en cosas tangibles que los rodean, como la forma de las casas que ven en la serie y sus propias casas. Muchos también compararon la familia del protagonista con su propia familia, hablando de los rasgos físicos de los personajes, de la ocupación de los padres y de la rivalidad entre hermanos. En este sentido, la edad parece ser un factor determinante porque los niños de 10 años, tanto de la escuela pública como de la privada, realizaron comparaciones más sofisticadas. De hecho, los miembros del grupo de discusión de 10 años de edad de la escuela privada hablaron de estilos de vida mexicano y norteamericano. Después de que hubieron concordado que Dexter vive en Estados Unidos, se les inquirió cómo pueden saberlo. Respondieron dos niños (Calvin y Armando) y una niña (Ari): «Calvin: Por el estilo de vida americano; Investigadora: ¿Cómo es el estilo de vida americano?; Calvin: Pues, una casa con su familia, ellos solos; Armando: Y además son siempre de dos pisos; Calvin: Ajá, y una escuela con casilleros, que son muy raros aquí en México; Armando: Y que van [a la escuela] con ropa de vestir; Calvin: Con pantalones, ropa de vestir, ajá; Ari: Y las escuelas de gobierno [en Estados Unidos] son como las particulares [en México], solo que las particulares [en Estados Unidos] son mucho más caras». En este diálogo, los participantes se muestran capaces de comparar los elementos de su vida cotidiana con lo que ven en la pantalla, incluso en el caso de un género como la animación, que podría ser considerado fantasioso.

La siguiente categoría de análisis fue el lugar donde habitaría Dexter. La mayoría de los niños participantes, tanto en las entrevistas como en los grupos de discusión, respondió que el personaje vive en los Estados Unidos. Dijeron que llegaron a esa conclusión porque habían visto al personaje llamado Mayor América (Major Glory en el original en inglés), el cual es un superhéroe que viste la bandera de las barras y las estrellas como uniforme. Los niños de diez años de edad de los grupos de discusión, tanto de la escuela pública como de la privada, se mostraron tan seguros de que Dexter vive en los Estados Unidos que inclusive trataron de adivinar la localización exacta de la serie, diciendo que debía ser en Washington o en la ciudad de Nueva York. Por otra parte, una minoría (un niño de ocho años de la escuela pública, cinco niños de nueve años de la escuela pública y un niño de nueve años de la escuela privada) respondieron que Dexter vive en la capital de su propio país, es decir, en la Ciudad de México. Al preguntarles la razón para llegar a esa conclusión, uno de ellos indicó que «porque la mayoría de los personajes [de la televisión] viven allá». De alguna manera, la ciudad capital es vista por estos niños de provincia como el centro de muchas cosas en el país, y particularmente de producción de televisión.

Cuando se preguntó a los participantes si sabían dónde se producía la serie «El laboratorio de Dexter», nuevamente los niños mayores en general, y particularmente aquellos que asistían a la escuela privada, fueron capaces de decir que el programa estaba producido en los Estados Unidos. Entre las razones que mencionaron para llegar a esta conclusión estaban: a) el título y los créditos finales del programa están en inglés; b) el uniforme del superhéroe Mayor América muestra la bandera norteamericana; c) habían visto un programa especial sobre la producción de la serie en el canal de pago Cartoon Network. Un niño de ocho años de la escuela pública indicó que él estaba seguro de que el programa estaba hecho en Estados Unidos porque lo había visto en Internet. Igualmente, un niño de nueve años de la escuela privada especificó que se producía en Estados Unidos «pero se traduce aquí [en México]». Solamente el grupo de nueve años de edad de la escuela pública indicó que la serie estaba producida en la Ciudad de México, pero no ofrecieron ninguna razón para justificar esta idea.

Siguiendo la lógica de lo anterior, los niños discutieron cómo es posible reconocer los orígenes de los dibujos animados. Los y las participantes de todos los estratos sociales y edades se mostraron certeros al describir las diferencias entre las series animadas japonesas y norteamericanas, incluso desde un punto de vista estético (dijeron, por ejemplo, que los personajes de los programas japoneses tienen ojos enormes y brillantes). De manera interesante, reflejando una concepción común entre los padres en esa época, algunos niños dijeron que los dibujos japoneses pueden reconocerse porque son violentos (como lo expresó un niño de diez años de la escuela privada: «de Japón vienen las más sangrientas, como «Jackie Chan», «Dragon Ball Z», «Las tortugas ninjas»). Asimismo, un par señaló que los letreros escritos que aparecen en los programas son un buen indicador para conocer el origen de los mismos.

En este punto, se les pidió a los niños que explicaran qué cosa hacen usualmente cuando ven textos escritos en inglés en los dibujos animados. La mayoría, sin distinción de edad ni estrato social, apuntó que cuando ven un letrero en otro idioma, esperan a que una voz «anuncie» lo que significa (sería una convención del doblaje). Una minoría de los participantes, todos ellos de la escuela privada, explicaron que ellos leían los textos escritos porque ya pueden entender lo que significan en inglés, dado que estudian el idioma como materia obligatoria, lo que no ocurre en las escuelas públicas. Sin embargo, las gemelas entrevistadas que asisten a una escuela pública (nueve años) dijeron que ellas cuando ven una palabra desconocida en un título buscan su significado en el diccionario bilingüe. Otro pequeño de ocho años de la escuela pública explicó que respecto a los letreros en inglés él preguntaba a su padre: «Yo nunca le entiendo nada. Yo le pregunto a mi papá: «¿Qué quiere decir ahí?». Y él tampoco le entiende nada. El que le entiende es mi tío, que ese sabe inglés…». Todos estos en conjunto parecen ser mecanismos comunes entre estos niños para tratar de entender las referencias culturales extranjeras.

Aparte de las respuestas de los participantes, fue también posible tomar nota de sus reacciones cuando miraban el episodio. De ahí se observó que todos ellos entendían la narrativa de modo bastante adecuado. Inclusive, participantes de diez años de la escuela privada reconocieron la imagen de Albert Einstein en uno de los capítulos observados. También se presentó un curioso momento de negociación de significados, cuando el niño de nueve años entrevistado (escuela privada), al ver la imagen de un «cowboy» galopando en un montaje en blanco y negro lo identificó con el revolucionario mexicano Emiliano Zapata, utilizando así una referencia local para explicarse algo que provenía fuera de su cultura.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

La observación de estos niños mirando televisión confirma lo que la teoría ya ha sustentado previamente, en el sentido de que estos son espectadores que crean significados de manera social dentro de sus comunidades interpretativas (Orozco, 1990; 1994; Seiter, 1998), ya que mientras veían los episodios grabados para la sesión comentaban con sus compañeros o hermanos, hacían observaciones, criticaban y preguntaban sobre lo que no entendían.

De manera complementaria, no son solamente una audiencia activa en el sentido ideológico, como la entendía Stuart Hall (2001), sino también una audiencia que se mantiene activa mientras ve la televisión (Palmer, 1986), ya que durante las entrevistas en sus casas, se entretenían en diferentes actividades mientras veían la televisión, como era jugar con sus juguetes, comer dulces, abrazar a sus muñecos de felpa, acomodarse en el mejor lugar posible o molestar a sus hermanos. Asimismo, se observó a partir de sus respuestas que estos niños tienen categorías claras para lo que es bueno y malo, realista o no realista en los programas de televisión y que saben qué esperar de los distintos géneros televisivos. De hecho, se deduce de sus respuestas que tienen un conocimiento especializado de los programas animados, lo que deja ver que constituyen una parte importante de su consumo cultural cotidiano, junto con los videojuegos, filmes, historietas, etc. (Kinder, 1991).

Respecto al tema específico de este trabajo, todos los participantes se mostraron capaces de seguir la narrativa de los dibujos animados norteamericanos en cuanto a la historia y entendieron el humor. No se presentaron diferencias ligadas al género de los participantes, pues niños y niñas mostraron igual comprensión. La edad fue un factor influyente, pues los mayores hicieron comparaciones más sofisticadas respecto a sus propias vidas y los elementos que veían en el programa, sobre todos los niños que asistían a la escuela privada, quienes también hablaron de manera un poco más abstracta sobre los estilos de vida mexicanos y norteamericano. El hecho de que estos tengan mayor familiaridad con el idioma inglés y que muchos de ellos hayan viajado al extranjero parece jugar un papel relevante en esta diferencia.

En cuanto a las nociones sobre los lugares representados en los dibujos animados y el lugar de producción del mismo, los participantes como grupo expresaron aún un cierto grado de ambigüedad. Para algunos de ellos la Ciudad de México, como lugar distinto y alejado de la provincia, fue un importante punto de referencia. De nuevo fue notorio que para los mayores y para aquellos de proveniencia social más alta, era mucho más claro que se trataba de un programa específicamente norteamericano, pues lo reconocían por los títulos y créditos en inglés, así como por los rasgos culturalmente específicos de los mismos personajes.

Muy reveladora fue la discusión sobre las maneras en que estos niños reconocen la proveniencia de los dibujos animados, ya que describieron con precisión los rasgos estéticos del anime japonés, e incluso expresaron algunos de los juicios que existen sobre él, como el hecho de que sea considerado violento.

Finalmente, fue posible identificar algunos de los mecanismos que estos niños aplican para entender las referencias culturales externas a su propia cultura, sobre todo los textos escritos en inglés que no se podían modificar o eliminar de las imágenes. Aquí la efectividad del doblaje como método de adaptación quedó confirmada, pues todos los entrevistados sabían que por convención una voz masculina (un señor) debe leer en español lo que está escrito. Esto implica que desde una edad muy temprana ya son conscientes de que ciertos contenidos televisivos son traducidos. Sin embargo, en la interpretación de estos textos fue notoria una diferencia entre los más jóvenes y los mayores, pues estos últimos reportaron que hacían el esfuerzo de preguntar a sus padres por el significado de las palabras o incluso las buscaban por sí mismos en el diccionario. Con respecto al origen social, se encontró que los niños de la escuela privada llevaban una ventaja, pues conocían mejor el idioma inglés y algunos de ellos habían estado ya en los Estados Unidos, o tenían parientes que vivían en aquel país. Todo esto les proporcionaba un mejor conocimiento de primera mano del modo de vida norteamericano. En este punto, mi interpretación coincide con la que proponen La Pastina y Straubhaar (2005) respecto a la percepción de las telenovelas en Brasil: el capital cultural (Bourdieu, 1984) parece ser un factor relevante que guía la interpretación de las narrativas mediales, incluso a una edad tan temprana como la que se estudió aquí.

Las implicaciones de estos resultados no se pueden generalizar a todos los niños mexicanos, ni aún a los de la provincia donde se realizó el estudio, debido al uso de métodos cualitativos. A pesar de ello, muchos de los comentarios y de las observaciones permiten vislumbrar que estos pequeños son conscientes de estar viendo un mensaje proveniente de otra cultura. Esta capacidad de diferenciar la propia realidad de la ajena a como es mostrada en un programa televisivo se desarrolla con la edad y está ligada igualmente al capital cultural, en el sentido de que los pequeños de las escuelas privadas que participaron tenían la posibilidad de desarrollar desde más temprano una concepción más compleja del mundo a través del aprendizaje del inglés, del acceso a sistemas de televisión de pago con canales internacionales e incluso a través de los viajes a Estados Unidos, donde habían visto personalmente la cultura que veían representada en los dibujos animados.

Al mostrarles representaciones del mundo, los mensajes de televisión contribuyen a la educación de los niños; por tanto, es significativo ratificar que estos pequeños los consumen activamente. En este estudio, limitado en su alcance pero aun así esclarecedor, los niños se confirman como espectadores curiosos y conscientes de lo que ven en la televisión. Se revelan como sujetos que construyen su identidad cultural a partir de una multiplicidad de estímulos (locales, nacionales y globales), a los que tienen acceso según las condiciones socioeconómicas en las que viven. Una nueva serie de observaciones empíricas seguramente enriquecería la comprensión de este fenómeno, sobre todo si se toma en cuenta que los niños están adoptando nuevas tecnologías como teléfonos inteligentes y tabletas, que son puntos de acceso privilegiados a referentes culturales propios y extranjeros.

Apoyos y agradecimientos

Una beca Fulbright-García Robles permitió realizar esta investigación. Agradezco especialmente a los supervisores de tesis Dr. Michael Kackman y Dr. Joseph Straubhaar.

Referencias

Amaral, E.S. (2005). Constructed Childhoods: A Study of Selected Animated Programmes for Children with Particular Reference for the Portuguese Case. (Tesis Doctoral). (http://goo.gl/1dXBf3) (26-04-2014).

Anderson, D.R. (2004). Watching Children Watch Television and the Creation of Blue’s Clues. In H. Hendershot (Ed.), Nickelodeon Nation: The History, Politics, and Economics of America’s only TV Channel for Kids. (pp. 387-434). New York: New York University Press.

Ang, I. (1985). Watching Dallas: Soap Opera and the Melodramatic Imagination. New York: Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Chalaby, J. (2002). Transnational Television in Europe: The Role of Pan-European Channels. European Journal of Communication, 17(2), 183-203.

Charles, M. (1989). La televisión y los niños. El reto de vencer al Capitán América. In E. Sánchez-Ruiz (Comp.), Teleadicción infantil, mito o realidad. (pp. 15-26). México: Universidad de Guadalajara.

Cobos, T.L. (2010). Animación japonesa y globalización: la latinización y la subcultura Otaku en América Latina. Razón y Palabra, 72. (http://goo.gl/N5AisY) (15-07-2014).

Cornelio-Marí, E.M. (2005). Mexican Children’s Perception of Cultural Specificity in American Cartoons. (Tesis de Maestría no publicada, The University of Texas at Austin).

Corona, S. (1989). El niño y la TV: una relación de doble apropiación. In E. Sánchez-Ruiz (Comp.), Teleadicción infantil, mito o realidad. (pp. 69-78). México: Universidad de Guadalajara.

Donald, S.H. (2005). Little Friends: Children’s Film and Media Culture in China. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Hall, S. (2001). Encoding/Decoding. In M.G. Durham, & D.M. Kellner (Eds.), Media and Cultural Studies: Key Works. (pp. 166-176). Maldern: Blackwell Publishers.

IBOPE (2005). IBOPE Network Ranking Multi-Country Report (Weighted Average of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru Survey Areas). Total Day Rating Among Cable Households (Average Monday-Sunday). (http://goo.gl/fHep7a) (26-04-2014).

Josephson, W.L. (1995). TV Violence: a Review of the Effects on Children at Different Ages. Ottawa: National Clearinghouse on Family Violence.

Kilborn, R. (1993). Speak my Language: Current Attitudes to Television Subtitling and Dubbing. Media, Culture and Society, 15, 641-660.

Kinder, M. (1991). Playing with Power in Movies, Television, and Video Games: from Muppet Babies to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kraidy, M. (1999). The Global, the Local and the Hybrid: a Native Ethnography of Glocalization. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 16, 456-473.

La Pastina, A., & Straubhaar, J. (2005). Multiples Proximities between TV Genres & Audiences: The Schism between Telenovelas Global Distribution and Local Consumption. Gazette: The International Journal for Communication Studies, 67(3), 271-288.

Liebes, T., & Katz, E. (1990). The Export of Meaning: Cross-Cultural Readings of Dallas. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lozano, J. (2008). Consumo y apropiación de cine y TV extranjeros por audiencias en América Latina. Comunicar, 15(30), 62-72.

Martel, F. (2011). Cultura Mainstream: cómo nacen los fenómenos de masas. (Trad. Núria Petit Fonserè). Madrid: Taurus.

Moran, K.C., & Chung, L.C. (2003). Creating an ‘Ambiguous’ Identity: the Role of International Mass Media in the Lives of Children. Second annual Global Fusion Conference, Austin, TX. October 2003.

Napier, S. J. (2001). Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. New York: Palgrave.

Orozco, G. (1990). El niño como televidente no nace, se hace. In M. Charles, & G. Orozco (Eds.), Educación para la recepción. (pp. 33-48). México: Trillas.

Orozco, G. (1994). Recepción televisiva y mediaciones: la construcción de estrategias para la audiencia. In G. Orozco (Ed.). Televidencia: perspectivas para el análisis de los procesos de recepción televisiva. (pp. 69-88). México D.F.: Universidad Iberoamericana.

Palmer, P. (1986). The Lively Audience: A study of Children around the TV Set. Sidney: Allen, & Unwin.

Pertierra, A. (2012). If They Show Prison Break in the United States on a Wednesday, by Thursday It Is Here: Mobile Media Networks in Twenty-First-Century Cuba. Television & New Media, 13(5), 399-414.

Seiter, E. (1998). Children’s Desires/Mother Dilemmas: The Social Context of Comsumption. In H. Jenkins (Ed.), The Children’s Culture Reader. (pp. 297-317). New York: New York University Press.

Document information

Published on 30/06/15

Accepted on 30/06/15

Submitted on 30/06/15

Volume 23, Issue 2, 2015

DOI: 10.3916/C45-2015-13

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?