Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

When compared to more digitized western countries, Italy seems to have suffered a delay of ten years, in both the use of ICTs by the elderly and the study of the relation between elderly people, ICTs and ageing. Considering this time lapse, it is now urgent that we question the factors that influence the adoption of ICTs by the elderly and whether ICTs can provide cultural and relational resources that could improve the quality of life of elderly in terms of health and social life. This article describes the main findings of a survey carried out as part of a larger national research project focused on active ageing, which involved 900 Italian people aged between 65 and 74 years of age. The research investigate socio-demographic characteristics of young elderly Italian Internet users and factors related to their use of ICTs. Results have shown that there is a strong digital divide between young elderly Italians, which is primarly influenced –in terms of classical dynamics– by differences in economic, social and cultural capital. With regard to the theme of active ageing, if it is true that highly digitalized young elders are generally characterized by good health, at the present stage of this research it is not possible to indicate whether the adoption of ICTs guarantees social inclusion and participation.

1. Introduction

In many studies focused on the adoption and use of ICTs by the elderly, one of the most widely used theoretical frameworks has been that of the digital divide, both on the primary level, in which the divide lies between the «haves» and «have nots», and on a secondary level, which is related to digital literacies, competencies, skills and motivations (Loges & Jung, 2001; Hargittai, 2002; Warschauer, 2002). Within this framework, as it is known, age seems to be one of the most discriminatory socio-demographic variables, to the benefit of young people.

In recent years, the increasing focus of international and European policies on the theme of active ageing1 has provided a second framework, according to which it is now possible to contextualize the adoption of ICTs within a far broader scenario – that of the progressive ageing of European populations (European Commission, 2011). Following the latest sociological research debate (Riva, Ajmone Marsan & Grassi, 2014), active aging is not understood solely in terms of structural (good/bad health) and economic (lengthening of working and leisure age) well-being, but also in terms of «quality» of life and as a subjective and socially rewarding ageing. Hence, the specific objective becomes to determine what «active aging» really means –from the point of view of the subjective, intersubjective and collective opportunities–, in relation to practices, ideas, values and cultural perspective. Today the role of media and communication technologies in improving the quality of life (Sourbati 2008), health (European Commission, 2011) and care (Olve & Vimarlund, 2006) of the elderly is a key issue in the academic discussion on ageing. In particular, there is discussion on the role of ICTs in the life of the elderly: if it is true that ICTs are a useful resource for the elderly to improve their health, care and social life (Selwyn, 2004), it is equally true that recent researches are uncovering risks and showing the dual role of the ICTs in daily life of the elderly (Aroldi & al, 2014).

The adoption of ICTs by the elderly is a well established area of ??research in countries like the US (Saunders, 2004), the UK (Haddon, 2000) and Scandinavian countries (Naumanen et al., 2009), where the penetration of the Internet into the home environment occurred early and rapidly, involving a significant portion of the older population. In comparison to other, more digitalised countries, Italy seems to have suffered a delay of around ten years (ISTAT, 2013), which makes it all the more urgent that we start to question the factors that influence (or hinder) the adoption and domestication of ICTs (Silverstone & Hirsch, 1992) by the elderly population and the real ability of digital technologies and networks to provide cultural and relational resources that improve the quality of life of older people.

Based on this theoretical background, the research questions that guided our research project were as follows:

1) (a) What are the socio- demographic characteristics of elderly Italian Internet users?; (b) What factors are related to the use of ICTs by these older users?

2) (a) How are ICTs used and incorporated (Silverstone & Hirsch, 1992) into the everyday life of the elderly?; (b) How do they contribute to an improved quality of life and active ageing?

To this end, this article describes the main findings of a survey carried out as part of a larger national research project focused on active ageing in Italy (Riva, Ajmone Marsan & Grassi, 2014).

2. Material and methods

The research project is based on a survey conducted between December 2013 and January 2014 through a face-to-face questionnaire administered to a statistically representative national sample of 900 young elderly Italians aged between 65 and 74 years of age (selected according to a random, proportional, stratified division defined by region and by the size of the place of residence, divided into two sampling stages)1.

The questionnaire collected data related to information concerning family relations; health status; leisure time and cultural consumption; any past or present working condition; participation in any kind of volunteering or socio-political activities; social capital and social solidarity; family networks and friendships; values; representation of the elderly condition, and the economic status of respondents.

With regard to media use, the questionnaire aimed to investigate:

• Choice of technological devices (personal and domestic digital devices).

• The preferred times and amount of time spent using PCs and the Internet

• Ways of using PCs and the Internet (chosen places, platforms used and people involved).

• Types of activities carried out using PCs and the Internet.

• Ways of learning how to use PCs, online services and the Internet (places and people involved in the learning activity).

• Reasons for using the Internet (changes in the lives of the elderly caused by the use of the Internet; fears, anxieties, enthusiasm in the use of PCs and the Internet).

3. Results

3.1. Possession and use of ICTs technologies: the socio-demographic characteristics of digitalized elders

In this section we will introduce the key findings of the questionnaire concerning the possession and use of digital media by younger elderly Italians, correlated with socio-demographic characteristics.

Firstly, it is significant to note that possession and use of digital media involve only a part of the sample, since only 21.3% of elderly Italians possess or use a computer (17.5% own and use a laptop, 16.7% own and use a desktop PC).

These data become more interesting if related to specific age groups (distinguishing between two age groups: 65-69 and 70-74) and gender. Men aged between 65-69 own and use computers and the Internet significantly more the than elderly women: women over 65 who have never used the Internet comprise 81% of the sample, compared to 65.6% of men.

Interestingly, the difference between men and women is less relevant than it is in relation to other technologies: although it is true that all devices (PCs, laptops, smart-phones, MP3, game consoles) are available and used more by males than by females (with a forked variable between the two genres), two devices (namely iPad and eBook reader) are an exception. Percentages of elderly males and females using tablets (including iPads) and eBook readers are very similar: respectively 6% of men versus 3.8% of women use tablets and 1.9% of men versus 1.5% of women use eBook readers. Given that tablets, iPads and eBook readers are new technologies and that «new users» tend to be women more often than men, this shows a likely phenomenon of leapfrogging. A significant number of elderly users who start to use ICTs when they are older than 65 (especially women) do so by using a new generation of technologies but skipping previous technologies (PC-laptops). 20% of elderly female users claim to access the Internet using mobile devices, compared to 8.5% of men, who are more often traditionally rooted, prefering to use to desktop devices.

Analysing the characteristics of digitalized elders in more detail, 45% of the elders who use computers today started using them before they turned 50, 28.2% started between 50 and 59 y.o.a. and 19.1% between the age of 60 and 64. Only 9.1% of users are «new» ICTs users (who started using a computer after the age of 64), with a significant difference between males (6.8%) and females (12.8%).

In terms of the preferred locations of Internet access, home is regarded as the best place, with 98.8% of users citing domestic connections and, in second place, 15.3% of connections at work (among our sample with Internet access). The elderly usualy access the Internet by themselves, with a significant proportion of seniors accessing the net with the help of their partner (19.2%), their children (17.6%), or their grandchildren (4.7%). As far as learning processes are concerned, 49.8% of users stated that they had learnt to use a computer at work, with a significant difference showing between males (57.8 %) and females (37.6 %): if most males learned at work, the proportion of women who learned how to use a computer by attending courses offered by organizations or associations, or municipal institutes, is substantially higher (22.8%) than that of men (14.3%). Males seem to have a more solitary learning approach, which is either practical (45.5% vs. 40.6 % of women) or guided by self-learning manuals (14.9% vs. 6.9%). Conversely, in addition to courses, women make more use of the help of younger friends or relatives (36.6% vs. 31.2 % of males) or peers (9.9% vs. 2.6%).

As far as SNSs use is concerned, a significant number of elderly Internet users joined Facebook and Twitter. In particular, 27.9% of male and 28.9% of female Internet users are on Facebook, while 11.5 % of male and 6.7% of female Internet users are on Twitter. It is noteworthy that, the users who access these tools use them very often: 46% of elderly male and 73% of elderly women with a Facebook profile use it every day.

Hence, there is a significant gender difference, with women being particularly heavy users of Facebook. Furthermore, SNSs use is strongly influenced by the differences between the two identified age groups: while 31,8% of the 65-69 year old sample use Facebook, the percentage drops to 21.1% in those aged between 70-74 years of age.

Moving away from the topic of allocations to the use of ICTs, an interesting point emerges in relation to the frequency of use. 71% of the elderly who access the Internet do so almost every day. As further evidence suggests, 58.8% of the elderly state that they access the Internet at any time of the day, but probably only when it is needed for something useful.

Having introduced and described the main characteristics of the digitalized elders (our first research question), let us now introduce the factors that are either positively or negatively correlated to the use of ICTs by Italians between 65 and 74 (question 1b),

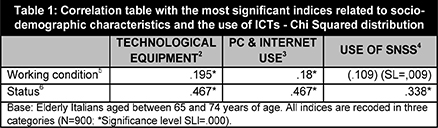

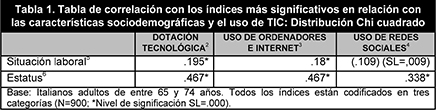

To answer this research question, we proceeded to build some indices that would outline the socio-economic status of the elderly. These indices were then crossed with the synthetic indices that describe the technology used – i.e. the use of the PC and the Internet, and participation in SNS - in an attempt to link the most significant correlations between allocation and use of information technology and the personal condition of the elderly users. The following table records the most significant correlations, between the indices used. Status appears to be significantly correlated to technological equipment, the use of PCs and the Internet, and the use of SNS. Working condition appears to be rather weakly correlated to both the adoption of digital technologies and their use. There is no significant correlation between working condition and social networks, nor between marital status and indices related to new technologies.

Furthermore, it is also interesting to note that, unlike the relation to technological equipment, differing employment status affects the use of social networks relatively little, in fact, amongst our elderly interviewees, Facebook appears to be a niche service that is transversal and less affected by the differences between workers and non-workers.

3.2. Possession and use of ICTs, well-being, active ageing

In this section we consider a number of indices that describe the quality of living conditions and the activity of older people from different points of view in relation to the use of ICTs. These indices relate to cultural and media consumption, health status, perceived seniority, physical activity, social capital, the intensity of relationships, intergenerational solidarity and individual and overall satisfaction in relation to the quality of their lives. These indices were then crossed with the indices that describe the technological equipment the use of a PC and Internet, and participation in SNS, in order to capture the most significant correlations between allocation and use of information technology, and overall quality of experience and activity of the elderly.

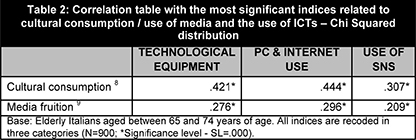

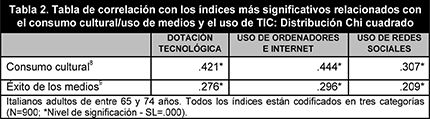

Beyond the allocation and use of PCs and the Internet, it is interesting to investigate how the possession and consumption of digital media fits into the concept of media diets and the broader cultural consumption of the elderly. Within the broader scope of analysing the leisure activities of the elderly, it is interesting to investigate whether the media diet of our sample presents any dynamic examples that feature the replacement / integration of old and new communication media.

This correlation table shows some interesting results: the use of technology, of PCs, the Internet and SNS were all significantly correlated with indices of cultural and media consumption. A culturally active life is linked to intensive use of digital media, just as the use and consumption of digital media does not replace old media, but rather links this usage to a high use of media (both in terms of time and variety of means). In particular, the index of cultural consumption is strongly correlated with the index of technological equipment, confirming the relationship between (economic and cultural) well-being of elderly individuals and access to the digital world.

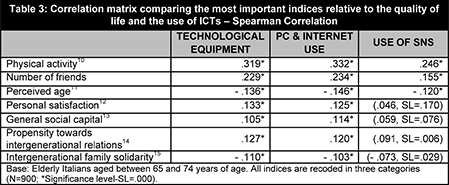

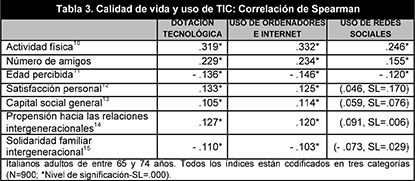

Shifting from economic well-being and status towards a broader reflection on the concept of psycho-physical relationships, the following table accounts for Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rs) of the most significant correlations (direct or inverse) between the indices used to define the quality of life and those relating to the use of ICTs.

It is noteworthy that the most significant direct correlations, with regard to technological equipment, the use of PCs and the Internet and the use of SNS, appear to be those relating to the index of physical activity and number of friends, while the most significant inverse correlation concerns the users’ perceived age. It is also possible to detect a correlation between technological equipment and the use of PCs and the Internet when compared to the indices of individual satisfaction, social capital and propensity towards intergenerational relations. However, the values ??indicate an inverse correlation with respect to intergenerational family solidarity. In addition, compared to these indexes, the use of SNS seems to be correlated to a lesser extent and not particularly meaningful. Finally, there are no significant correlations between the use of SNS and the indices of personal satisfaction, social capital, or intergenerational relations.

Overall, the data indicate that the possession and use of ICTs is more likely to accompany an elderly condition characterized by good levels of physical activity, a large number of friends and a low perceived age. General social capital is also a significant element of this condition, as is the propensity for intergenerational relationships, while family solidarity is not.

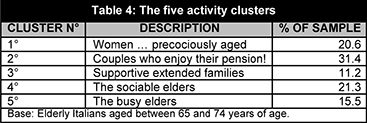

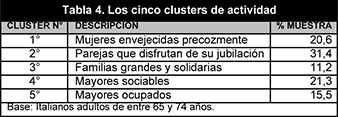

A second means of assessing the importance of ICTs in the context of the activity of young elders is based on the cluster analysis; the five clusters were identified and their weight in the sample calculated as follows (Rossi, Bramanti & Moscatelli, 2014):

The first cluster, equal to about one-fifth of the sample, consists mainly of women aged between 70 and 74 with low socio-economic status, few health problems and limited social relations, who are at risk of exclusion. The second and largest cluster (almost one-third of the sample), includes mostly retired couples, with an average income, relatively low in status, who are in good health and have a good network of friends and family, but cultivate few interests or forms of social engagement, with the exception of an average level of physical activity. The third cluster of older people is the smallest (slightly more than one in ten), who live in extended family households, or in the presence of adult children at home because they are strongly committed to their children and grandchildren. This cluster is found more in the south of Italy and is characterized by a low income status, even when compared with the low general average, and represents an approach to active ageing that almost seems to continue on without distinction from the middle stage of life. The fourth cluster, the «Sociable» elders, constitutes more than one-fifth of the sample and is characterized by a dense network of friendships, parental and neighborhood relations and a high personal and relational satisfaction index. These individuals do not yet perceive their age as a limit and confirm a high level of physical activity. Finally, the «busy» elders confirm a 360° activity level. These individuals are mostly men between 65 and 69 years of age, who are still engaged in high status and high income employment, and invest in the support of younger generations, participate in club activities, do exercise and nurture high levels of confidence in others and of social solidarity.

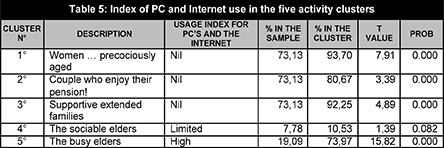

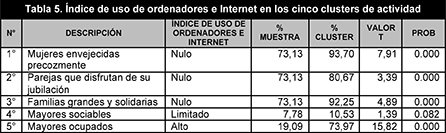

The survey index of PC and Internet use in the five clusters is as follows (table 5).

As is shown, ICTs are irrelevant for both older women who are exposed to the risk of exclusion (1st cluster), and for spouses who are fully involved in family support within the context of a low-mid socio-economic background (3rd cluster); their presence is nil or limited with relation to both pensioner couples dependent on the private sector (2nd cluster) and the most Sociable individuals (4th cluster). The presence of ICTs use is notably higher and more significant to the «Busy» elders (5th cluster), especially for those who enjoy higher levels of activity, are often still involved in the working world and have a strong «generative dimension which includes the family and social area [...] and identifies a profile of individuals who enjoys good overall satisfaction» (Rossi, Bramanti & Moscatelli, 2014).

Finally, some indication of the perception of the role of ICTs in defining the quality of life of older respondents is derived from a battery of questions, which describes the changes felt while using Internet. 63.7% of older users noted positive changes with regard to the cognitive dimension (information on current affairs and personal interests), while 36.3% refer to positive changes in the sphere of relationships («I stay in touch with my friends and family») and the overall perception of their own activity («compared to my peers who live without the Internet I feel more active»). For many respondents the Internet is a knowledge resource used in relation to health and well-being (40.3%) and in gathering information relative to the treatment of their diseases (29.9%). Other areas of perceived change affect the concept of time management: about 25% say they watch less television, but only 13.5% said they spend too much time on the computer and about 8% stated they had become more sedentary and / or pass more time at home; the incidence of those who think they spend less time with their loved ones (2.2%) is even lower. Another aspect, which is not negligible, even though it affects a distinct minority group, is the problem area of fears related to the use of Internet: some elders fear making mistakes, or that their privacy will be violated (over 20%), or fear that they are not able to assess the reliability of online sources (18.7%). Finally, although the use of the Internet is generally accompanied by a perception of increased activity and social interaction, participation in online and offline activities still remains a minority practice (from the 12.5% of those who feel «more active in the life of my local community / community / neighborhood», to the 4.1% who express their opinions more freely in SNS).

4. Discussion and conclusion

The results of the survey presented here show how:

• Question 1a) the digitalized elderly feature as a (significant) minority in the Italian population aged between 65 and 74, and share highly specific, distinctive demographic and relational characteristics in relation to their non-digitalized counterparts, with a stable economic and employment condition coming first, followed by a higher level of education, as well as a satisfying relational context and good levels of physical activity.

• (Question 1b) the domestic context seems to be crucial to the adoption of new technologies and influences their «good use»: the home is the place in which most elders’ media consumption develops, including uses related to new media (V27 Where access PCs, V32.1 Access to the Internet: at home). Media consumption by the elderly is developed within both temporal and spatial contexts, and produces processes of media domestication and routine that are shared / negotiated within the family. Beyond the biological fact of age, there are other stories (personal, work, family, generational) that influence the domestication of technology. Completed professional experiences, relationships with family, and even the spatial organization of the home, are all factors that strongly influence access to and the use of ICTs.

• Question 2a the Internet is extensively and continuatively used by our digitalized elders. The majority of the (few) younger elders who access the Internet are in fact heavy users. Accessing the Internet is a common practice rooted and incorporated into the everyday life of our sample: once they have crossed the threshold of Internet access, users become mature users in all respects and are no longer occasional visitors.

• Question 2b) the possession and use of ICTs is more likely to accompany an elderly condition characterized by good levels of physical activity but some answers to our questionnaire (V38: «Since using the Internet... ») have pointed out that prolonged and excessive use of the Internet, alongside w a number of positive changes, is sometimes identified by elders as a problem in relation to their family life, their previous routines, and the potential activities now no longer carried out in favor of the Internet.

Amongst the potential signs that reveal the ambivalent role of ICT, is that, in some cases, ICTs are used in an attempt to resolve difficulties. In an apparently paradoxical comparison, although the correlations are not significant, the use of SNS is inversely correlated to the relational satisfaction index (rs = -.067; SL=0.45) and is only weakly related to social capital indices, when compared to the use of PCs and the Internet. This would almost seem to indicate a compensatory use of SNS due to a network of weak or unsatisfactory social relations rather than an online investment countered by a strong social capital offline.

These results help to contextualize the phenomenon of the progressive digitalization of older Italians in terms of the «classic» dynamics of the digital divide, which are influenced by socio-economic dimensions (Loges & Jung, 2001; Smith, 2014). Thus, wealthier elders, with a greater cultural and social capital, and who started to use computers during their professional working career, are characterized by increased susceptibility to possession and use of ICTs. This is a phenomenon –that of the digital divide related to income– that significantly characterizes the early stages in the spread of ICTs significantly. In poorly digitalized segments such as that of the elderly Italian population, ICTs courses seem to have spread by «traditional» means, resulting in processes of exclusion based on income, and social and cultural capital (Van-Dijk, 2005).

Hence, we are faced with an increasing polarization and radicalization of the haves and have nots, in which a sizable chunk of young elders is disconnected and risks marginalisation (due to broader social factors), while for a minority of more affluent users (economic and social), digital media has penetrated everyday life with extreme force, in terms of both the time spent on and economic and relational investment therein.

In truth, things could change in the coming years: the arrival of a new generation of elders who grew up in a more digitalized, computerized society (including their professional sphere) than their predecessors, may dilute the centrality of income and status levels in determining the phenomenon of the digital divide. From this point of view, the generational approach on one hand (Aroldi & Colombo, 2013; Loos, 2011) and the repetition of this survey after a number of years could clarify the direction this phenomenon will take.

With regard to the relation between ICTs and well-being, at the present stage of this research it is not possible to indicate whether the adoption of ICTs guarantees inclusion and participation. The transverse diffusion of technology amongst older people probably does not automatically determine greater well-being for all: the issue of ICTs adoption and active ageing requires further investigation, before we can understand the role played by ICTs in the daily life of the elderly and their relational, spatial and temporal organization in domestic contexts (Haddon, 2000) fully. Using the domestication theory framework and an ethnographic approach, we are undertaking a second phase of our research with a qualitative approach in order to investigate the subjective dimension of the perceived role of ICTs and personal story of «conversion» (Silverstone & Hirsch, 1992) of ICTs into tangible meanings and values that contribute to the quality of the elderly everyday life.

Finally, some considerations in terms of policies and education. As our results suggest, active ageing cannot be simplistically defined by the possession of technological devices or their use (Dickinson & Gregor 2006): active ageing signifies «quality of life» that could also be related (but not determined by) the many uses of ICTs. These results suggest the necessary development of inclusive digital policies and education programs that take into account the risks and benefits, as well as the complex role played by ICTs. The processes of digital inclusion should aim to promote the «good use» (conscious, careful, thoughtful, moderate, unperturbing relational contexts) of ICTs and not simply the diffusion of computers, tablets and smartphones to deal (deterministically) with age related problems.

Acknowledgement and support

This research is supported by Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Italia).

Notes

1 1,600 names were extracted from electoral list of 90 municipalities, using the systematic method. 900 were the repondentes. Error sample: 3%; confidence error: 0.05%.

2 This index consists of the elaboration of answers related to questions on the possession and use of ICTs (Laptop or Netbook, Desktop computer, tablet, e-book reader, Smartphone, WiFi, MP3 player).

3 Questions related to the frequency of PC use and the nature of the activities effected (copying-moving files or folders, using ‘copy-paste’, calculating formulas in spreadsheets, transfering files from a PC to other devices, using e-mail, playing online games, reading the news, refering to Wikipedia, blogs, forums, community-produce UGC, searching for information related to on daily life and health, performing administrative, shopping online)

4 Responses regarding the use of Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube and related services (chat, shares, comments).

5 Works/does not work.

6 Responses regarding the professional activity and level of education of the respondent, their partner and father.

7 Single, Married, Widowed, In a Domestic Partnership, Separated / Divorced.

8 Responses regarding the frequency of reading books and of going to concerts, shows, museum, lessons.

9 Responses regarding the frequency of viewing, listening and reading of television, radio, newspapers, and weekly publications.

10 Responses regarding sporting activities, outdoor activities, dancing, travelling etc.

11 Responses regarding the subjects’ reflexive perception of their age.

12 Responses regarding individual satisfaction in relation to income, health, work, place of living and spiritual elements.

13 Responses regarding the interest shown in and trust in others (fellow countrymen, foreigners, Europeans, disabled, children, the unemployed, the elderly).

14 Responses regarding the opinion on the desirability and dynamics of collaboration between older and younger users.

15 Responses relating to opinions on mutual responsibility between parents and children.

16 The statistical software used for clustering is SPAD, that produce cluster with a two step clustering [see Lanzetti (1995), 81-99)].

References

Aroldi, P., & Colombo, F. (2013). La terra di mezzo delle generazioni. Media digitali, dialogo intergenerazionale e coesione sociale. Studi di Sociologia, 3-4, 285-294. (http://goo.gl/rmTSlU) (10-10-2014).

Aroldi, P., Carlo, S., & Colombo, F. (2014). «Stay Tuned»: The Role of ICTs in Elderly Life. In G. Riva, P. Ajmone, & C. Grassi (Eds.), Active Ageing and Healthy Living: A Human Centered Approach in Research and Innovation as Source of Quality of Life. (pp. 145-156). Amsterdam: IOS Press. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-425-1-145

Dickinson, A., & Gregor, P. (2006). Computer Use has no Demonstrated Impact on the Well-being of Older Adults. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 64(8), 744-753. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2006.03.001

European Commission (2011). Active ageing, Special Eurobarometro 378. Bruxelles: EU Publishing. (http://goo.gl/c6BfB) (10-10-2014).

Haddon, L. (2000). Social Exclusion and Information and Communication Technologies: Lessons from Studies of Single Parents and the Young Elderly. New Media and Society, 2(4), 387-406. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1461444800002004001

Hargittai, E. (2002). Second-Level Digital Divide: Differences in People’s Online Skills. First Monday, [S.l.], apr. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v7i4.942

ISTAT (2013). Cittadini e nuove tecnologie. Roma: Pubblicazioni Istat. (http://goo.gl/LTTvn2) (10-10-2014).

Lanzetti, C. (1995). Elaborazioni di dati qualitative. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Loges, W.E., & Jung J.Y. (2001). Exploring the Digital Divide: Internet Connectedness and Age. Communication Research, 28(4), 536-562. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/009365001028004007

Loos, E.F. (2011). Generational Use of New Media and the (ir)relevance of Age. In F. Colombo, & L. Fortunati (Eds.), Broadband Society and Generational Changes. (pp. 259-273). Berlin: Peter Lang.

Naumanen, M., & Tukiainen, M. (2009). Guided Participation in ICT-education for Seniors: Motivation and Social Support, Frontiers in Education Conference, 2009. FIE ‘09. 39th IEEE, 1-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/FIE.2009.5350544

Olve, G.N., & Vimarlund, V. (2006). Elderly Healthcare, Collaboration and ICTs - Enabling the Benefits of an Enabling Technology. VINNOVA. Stockholm: Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems Publishing. (http://goo.gl/ZySpnK) (10-10-2014).

Riva, G., Ajmone-Marsan, P., & Grassi, C. (2014) (Eds.). Active Ageing and Healthy Living: A Human Centered Approach in Research and Innovation as Source of Quality of Life. Amsterdam: IOS Press. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-425-1-57

Rossi, G., Boccacin, L., & Moscatelli, M. (2014). Active Ageing and Social Generativity: Social Network Analysis and Intergenerational Exchanges. A Quantitative Study on a National Scale. Sociologia e Politiche Sociali. Milano: Franco Angeli, pp. 33-60.

Saunders, E.J. (2004). Maximizing Computer Use among the Elderly in Rural Senior Centers. Educational Gerontology, 30(7), 573-585. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03601270490466967

Selwyn, N. (2004). The Information Aged: A Qualitative Study of Older Adults’ Use of Information and Communications Technology. Journal of Ageing Studies, 18, 369-384. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2004.06.008

Silverstone, R., & Hirsch, E. (1992) (Eds.). Consuming Technologies: Media and Information in Domestic Space. London: Routledge.

Smith, A. (2014). Older Adults and Technology Use. Pew Research Center. (http://goo.gl/6nMNra) (10-10-2014).

Sourbati, M. (2008). On Older People, Internet Access and Electronic Service Delivery. A Study of Sheltered Homes. In E. Loos, L. Haddon, & E. Mante-Meijer (Eds.), The Social Dynamics of Information and Communication Technology. (pp. 95-104). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Van-Dijk, J. (2005). The Deepening Divide: Inequality in the Information Society. London: Sage.

Warschauer, M. (2002). Reconceptualizing the Digital Divide. First Monday, [S.l.], jul. 2002. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v7i7.967

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Italia parece tener un retraso de unos diez años en comparación con otros países más digitalizados, tanto en el uso de las TIC por las personas mayores como en el estudio de la relación entre las TIC y los mayores de 65 años. Por ello, se hace urgente examinar los factores que influyen en la adopción de las tecnologías por los mayores y la capacidad real de estas para proporcionar recursos culturales e interactivos, útiles para mejorar el envejecimiento activo y mejorar su calidad de vida en salud y vida social. Este trabajo describe los principales resultados de un estudio que involucró a 900 italianos de 65 a 74 años, en el marco de un proyecto nacional de investigación sobre el envejecimiento activo. El estudio indaga en las características sociodemográficas de los mayores italianos usuarios de Internet y en los factores que influyen en el uso de las TIC. Los resultados evidencian que existe una fuerte brecha digital entre los mayores, influenciada por el contexto económico y cultural. En cuanto al envejecimiento activo, se demuestra que los mayores altamente digitales presentan una mejor vida saludable en su envejecimiento, sin poderse concluir que el uso de las TIC garantice la inclusión y participación.

1. Introducción

En muchos de los estudios sobre adopción y uso de las TIC entre personas mayores, uno de los marcos teóricos más recurrentes ha sido el de la brecha digital, tanto a nivel primario, donde esta se establece entre «los que tienen» y «los que no tienen», como a nivel secundario, vinculado a alfabetizaciones digitales, competencias, habilidades y motivación (Loges & Jung, 2001; Hargittai, 2002; Warschauer, 2002). En este contexto, según sabemos, la edad parece ser una de las variables sociodemográficas más discriminatorias, en beneficio de la población más joven.

En los últimos años, las políticas europeas e internacionales han dedicado una creciente atención al llamado envejecimiento activo1, proporcionándose así un segundo marco, según el cual hoy en día es posible contextualizar la adopción de las TIC en un escenario mucho más amplio, el del envejecimiento progresivo de la población europea (Comisión Europea, 2011). Según los últimos debates en investigación sociológica (Riva, Ajmone Marsan & Grassi, 2014), el envejecimiento activo no se entiende exclusivamente en términos de bienestar estructural (buena o mala salud) o económico (prolongación de la vida laboral y edad de ocio), sino también en términos de «calidad» de vida y como envejecimiento subjetivo y socialmente gratificante. De ahí que de forma específica, el objetivo sea determinar qué significa verdaderamente «envejecimiento activo» desde el punto de vista de lo subjetivo, intersubjetivo y de las oportunidades colectivas en relación con la práctica, las ideas, los valores y la perspectiva cultural. Hoy en día el papel que tienen los medios y las tecnologías de la comunicación en la mejora de la calidad de vida (Sourbati, 2008), de la salud (Comisión Europea, 2011) y en la atención a los mayores (Olve & Vimarlund, 2006) es una cuestión fundamental en toda discusión académica en torno al envejecimiento. En esta línea, muchos investigadores discuten hoy en día el papel de las TIC en la vida de los mayores, si bien es cierto que las TIC constituyen un recurso para mejorar la salud, la atención y la vida social de este colectivo (Selwyn, 2004), es igualmente cierto que algunas investigaciones recientes han empezado a alertar de los riesgos y de la dualidad que implica la presencia de las nuevas tecnologías en la vida diaria de estas personas (Aroldi & al., 2014).

La adopción de las TIC en personas de edad avanzada es un área de investigación que está bastante consolidada en países como Estados Unidos (Saunders, 2004), Reino Unido (Haddon, 2000) y en los países escandinavos (Naumanen & al., 2009), donde la penetración de Internet en los hogares fue temprana y veloz, y además implicó a una buena parte de la población más adulta. En comparación con otros países más digitalizados, Italia parece haber sufrido alrededor de diez años de retraso (ISTAT, 2013). Esta demora convierte en una cuestión más urgente si cabe el planteamiento de los factores que influencian (u obstaculizan) la adopción y el dominio de las TIC (Silverstone & Hirsch, 1992) por los mayores, y la habilidad real de las tecnologías digitales y las redes para proporcionar recursos culturales y relacionales que puedan mejorar su calidad de vida.

Basándonos en este contexto teórico, las preguntas de investigación que han guiado nuestro proyecto son:

1) a) ¿Qué características sociodemográficas definen a las personas mayores que utilizan Internet en Italia?; b) ¿Qué factores guardan relación con el uso que hacen de las TIC estos usuarios?

2) a) ¿Cómo se utilizan e incorporan las TIC (Silverstone & Hirsch, 1992) a la vida diaria de los mayores?; b) ¿Cómo contribuyen las TIC a mejorar la calidad de vida y al envejecimiento activo?

Con este objetivo, este artículo describe los hallazgos más importantes extraídos de un estudio llevado a cabo dentro de un proyecto de investigación nacional a mayor escala sobre envejecimiento activo en Italia (Riva, Ajmone Marsan & Grassi, 2014).

2. Materiales y métodos

El proyecto de investigación se basa en un estudio realizado entre diciembre de 2013 y enero de 2014 a través de un cuestionario presencial administrado a una muestra nacional estadísticamente representativa de 900 adultos de edades comprendidas entre los 65 y los 74 años (seleccionada a partir de una división aleatoria, proporcional, estratificada y definida según regiones y el tamaño del lugar de residencia, obtenida en dos etapas de muestreo).

A partir del cuestionario se obtuvieron los datos relacionados con la información relativa a relaciones familiares, estado de salud, tiempo de ocio y consumo cultural, condiciones laborales pasadas o vigentes en el momento de la recogida de datos, participación en actividades socio-políticas o de voluntariado, capital social y solidaridad social, redes familiares y amigos, valores, representación de la condición de mayores y situación económica de los participantes.

En relación con el uso de los medios, el cuestionario pretendía investigar:

• Dispositivos tecnológicos (dispositivos digitales personales y domésticos).

• Horarios de preferencia y tiempo de exposición a ordenadores y a Internet.

• Formas de uso de ordenadores e Internet (sitios escogidos, plataformas utilizadas y personas implicadas).

• Tipos de actividades llevadas a cabo durante el uso.

• Formas de aprendizaje de uso de ordenadores, servicios en línea e Internet (lugares y personas implicadas en la actividad de aprendizaje).

• Razones para el uso de Internet (cambios provocados por el uso de Internet: miedos, ansiedades, entusiasmo).

3. Resultados

3.1. Tenencia y uso de TIC: características sociodemográficas de los ancianos digitalizados

En esta sección introducimos los hallazgos más importantes extraídos a partir del cuestionario en relación con la tenencia y el uso de los medios digitales en el sector de la población estudiado en Italia, en correlación con sus características sociodemográficas.

En primer lugar, es significativo señalar que la tenencia y el uso de medios digitales afecta tan solo a una parte de la muestra, puesto que tan solo el 21,3% de los participantes posee o utiliza un ordenador (el 17,5% tiene y utiliza un portátil, el 16,7% tiene y utiliza un ordenador de mesa).

Resultó muy interesante relacionar estos datos con grupos de edad específicos (dos franjas de edad: 65-69 y 70-74) y con el género. Los hombres de entre 65 y 69 años resultaron tener y utilizar el ordenador e Internet significativamente más que las mujeres: las mujeres de más de 65 años que nunca habían utilizado Internet conformaban el 81% de la muestra, comparado con el 65,6% de hombres.

Parece igualmente interesante que en este caso, la diferencia que se establece entre hombres y mujeres es menos relevante de la establecida en relación con otras tecnologías: si bien es cierto que todos los dispositivos (ordenadores, portátiles, smartphones, MP3, videoconsolas) están más disponibles y se usan más entre hombres que entre mujeres (con una variable bifurcada entre los dos), existen dos dispositivos (el iPad y el lector de eBook) que constituyen una excepción. Los porcentajes de hombres y mujeres de edad avanzada que utilizan tabletas (incluidos los iPads) y los lectores de eBook son muy similares: respectivamente, un 6% de hombres frente a un 3,8% de mujeres utiliza tabletas y un 1,9% de hombres frente a un 1,5% de mujeres utiliza lectores de eBook. Si tenemos en cuenta que tanto las tabletas, como iPads y lectores eBook son tecnologías novedosas, y que los «nuevos usuarios» suelen ser con más frecuencia mujeres, parece estar surgiendo un nuevo fenómeno que revierte la tendencia anterior. Un número importante de los mayores que han empezado a manejar TIC con más de 65 años (especialmente mujeres) lo ha hecho de la mano de una nueva generación de tecnologías, obviando el funcionamiento de dispositivos anteriores (PC, portátiles). El 20% de las mujeres participantes declara acceder a Internet a partir de dispositivos móviles, en comparación con el 8,5% de los hombres, que con frecuencia permanecen más apegados a dispositivos de sobremesa.

Cuando analizamos con más detalle las características de la población estudiada, descubrimos que el 45% de los que emplean hoy en día el ordenador comenzó a hacerlo antes de cumplir 50 años, el 28,2% comenzó a utilizarlo entre los 50 y 59 años, y el 19,1% entre los 60 y 64 años. Tan solo el 9,1% de los usuarios son «nuevos» usuarios TIC (que han empezado a utilizar los ordenadores después de los 64 años), con una diferencia significativa entre hombres (6,8%) y mujeres (12,8%).

En lo que respecta a los lugares de preferencia para el acceso a Internet, el hogar se considera la mejor ubicación, con un 98,8% de los usuarios que cita la conexión doméstica y, en segundo lugar, un 15,3% hace referencia a la conexión en el trabajo (dentro de la muestra que tiene acceso a Internet). Las personas de edad avanzada suelen acceder a Internet por ellas mismas, y entre ellas existe una proporción destacable que accede con ayuda de su pareja (19,2%), de sus hijos (17,6%) o de sus nietos (4,7%). En lo relativo a los procesos de aprendizaje, el 49,8% afirma que aprendió a manejar Internet en el trabajo, estableciéndose una diferencia importante entre el número de hombres (57,8%) y de mujeres (37,6%). Siendo así, la proporción de mujeres que aprendió a utilizar Internet asistiendo a cursos ofrecidos por organizaciones o asociaciones, o institutos municipales es sustancialmente mayor (22,8%) que la de hombres (14,3%). Los hombres parecen tener una aproximación al aprendizaje más solitaria, motivada por la práctica (45,5% frente al 40,6% de mujeres) o apoyada por guías de autoaprendizaje (14,9% frente al 6,9%). De forma contraria, además de los cursos, las mujeres se valen más frecuentemente de la ayuda de amigos más jóvenes o de familiares (36,6% frente al 31,2% de hombres), o colegas (9,9% frente al 2,6%).

En el uso de las redes sociales, un número importante de usuarios se ha unido a la red de Facebook y a Twitter. En particular, el 27,9% de hombres y el 28,9% de mujeres está en Facebook, frente al 11,5% de hombres y el 6,7% de mujeres que está en Twitter. Incluso en este caso, los que tienen acceso a estas herramientas las utilizan a menudo: el 46% de los hombres y el 73% de las mujeres con una cuenta en Facebook acceden diariamente. De aquí se extrae una importante diferencia de género, siendo las mujeres más activas en la red Facebook.

Además, el uso de las redes sociales está fuertemente influenciado por las diferencias entre los dos grupos de edad: en la muestra de 65-69 años, el 31,8% utiliza Facebook, y el porcentaje desciende al 21,1% en la franja de 70-74 años.

En lo relativo al uso de las TIC, aparece un punto interesante relativo a la frecuencia de uso. El 71% de los que tienen acceso a Internet se conecta casi diariamente. Como sugieren pruebas adicionales, el 58,8% afirma acceder a Internet en cualquier momento del día, pero más probablemente cuando les resulta necesario o útil. Una vez introducidas y descritas las principales características del grupo de edad objeto de estudio (en relación con la primera pregunta de la investigación), nos proponemos introducir los factores que correlacionan positiva o negativamente con el uso de TIC en italianos de entre 65 y 74 años (pregunta 1b).

Para dar respuesta a esta pregunta de investigación, procedimos a construir algunos índices que pudieran describir la situación socioeconómica de los mayores. Estos se cruzaron con los sintéticos que describen la tecnología empleada, por ejemplo, el uso de ordenadores y de Internet, y la participación en redes sociales, en un intento de vincular las correlaciones más significativas entre distribución y uso de las tecnologías de la información y la condición personal de los usuarios de edad avanzada. La siguiente tabla recopila las correlaciones más significativas entre los índices utilizados.

El estatus parece correlacionar significativamente con la dotación tecnológica, con el uso de ordenadores e Internet, y el uso de redes sociales. La situación laboral parece correlacionarse de una forma más débil con la adopción de tecnologías digitales y con su uso. No existe una correlación significativa entre la situación laboral y las redes sociales, así como tampoco se da entre el estado civil7 y los índices relacionados con las nuevas tecnologías.

Por otro lado, también es interesante apuntar que, a diferencia de la relación con la dotación tecnológica, la situación laboral afecta relativamente poco al uso de las redes sociales. De hecho, entre los mayores entrevistados, Facebook se presenta como un servicio transversal, poco afectado por las diferencias entre trabajadores y no trabajadores.

3.2. Tenencia y uso de TIC, bienestar, envejecimiento activo

En esta sección consideramos un número de índices que describen la calidad de las condiciones de vida y la actividad de los mayores desde diferentes puntos de vista en relación con el uso de las TIC. Estos índices están relacionados con el consumo cultural y mediático, el estado de salud, la vejez percibida, la actividad física, el capital social, la intensidad de relaciones sociales, la solidaridad intergeneracional e individual y la satisfacción general en relación con la calidad de vida. Estos índices se cruzaron con los que describen la dotación tecnológica y el uso de ordenadores e Internet y la participación en las redes sociales, para extraer las correlaciones más significativas entre distribución y uso de las tecnologías de la información y la calidad general de la experiencia y de la actividad en los mayores.

Más allá de la distribución y el uso de ordenadores e Internet, resulta interesante investigar cómo la tenencia y el consumo de medios digitales se adecua al concepto de dieta de medios y al amplio consumo cultural de los mayores. Desde el enfoque más amplio del análisis de las actividades de ocio que realizan estas personas, es interesante investigar si la dieta de medios de nuestra muestra presenta ejemplos dinámicos que representen el reemplazamiento o la integración de los viejos y nuevos medios de comunicación.

Esta tabla de correlaciones arroja resultados llamativos: el uso de la tecnología, ordenadores, Internet y redes sociales correlacionó de forma significativa con los índices de consumo cultural y mediático. Una vida activa en términos culturales está ligada al uso intensivo de los medios digitales, así como el uso y el consumo de medios digitales no sustituye a los medios tradicionales, pero vincula su empleo a un elevado uso de los medios (en lo que respecta al tiempo y variedad de dispositivos). En particular, el índice de consumo cultural correlaciona fuertemente con el índice de dotación tecnológica, confirmando la relación entre el bienestar (económico y cultural) de los mayores, y el acceso al mundo digital.

Para ilustrar la transición desde el bienestar y el estatus económico hacia una reflexión más amplia sobre el concepto de relaciones psicofísicas sigue la siguiente tabla, que representa el coeficiente de correlación de Spearman (rs) de las correlaciones más significativas (directas o inversas) entre los índices utilizados para definir la calidad de vida y aquellos relacionados con el uso de TIC.

Como se puede percibir, las correlaciones directas más significativas en relación con la dotación tecnológica, el uso de ordenadores e Internet y de las redes sociales, parecen ser aquellas relativas al índice de actividad física y al número de amigos, mientras que las correlaciones inversas están relacionadas con la edad percibida de los usuarios. También es posible detectar una correlación existente entre la dotación tecnológica y el uso de ordenadores e Internet cuando lo comparamos con los índices de satisfacción individual, capital social y propensión hacia las relaciones intergeneracionales. Sin embargo, los valores indican una correlación inversa con respecto a la solidaridad familiar intergeneracional. Además, comparado con estos índices, el uso de redes sociales parece correlacionar en menor sentido y no de forma particularmente significativa. Por último, no se registran correlaciones significativas entre el uso de redes sociales y los de satisfacción personal, capital social y relaciones intergeneracionales.

En su conjunto, los datos indican que la tenencia y el uso de TIC suele caracterizar a un perfil de persona de edad avanzada que destaca por tener buenos niveles de actividad física, un gran número de amigos y una edad percibida menor. El capital social general también es un elemento importante de esta condición, como lo es la propensión a relaciones intergeneracionales, al tiempo que la solidaridad familiar no lo es.

La segunda forma de evaluar la importancia de las TIC en el contexto de la actividad de la población objeto de estudio se basó en el análisis cluster. Se identificaron cinco clusters y se calculó su importancia en la muestra según mostramos en la tabla 4 (Rossi, Bramanti & Moscatelli, 2014).

El primer cluster, correspondiente aproximadamente a un quinto de la muestra, consiste fundamentalmente en mujeres de entre 70 y 74 años con un estatus socioeconómico bajo, algunos problemas de salud y relaciones sociales limitadas, que se encuentran en riesgo de exclusión. El segundo, que es también el más numeroso (prácticamente un tercio de la muestra), incluye en su mayoría a parejas jubiladas con ingresos medios, incluso de bajo estatus, que gozan de buena salud y tienen una buena red de amigos y familiares, pero que cultivan escasos intereses o formas de compromiso social, con la excepción de un nivel normal de actividad física. El tercer cluster es el más minoritario (algo más de una décima parte de la muestra), y engloba a personas que viven en los hogares de familiares, o que cuentan con la presencia de sus hijos adultos en casa como consecuencia de su dedicación a hijos y nietos. Este cluster es más propio de las regiones del sur de Italia, y se caracteriza por un nivel de ingresos bajo, en comparación incluso con la media de referencia para estos casos. Este cluster representa una aproximación al envejecimiento activo que parece tener continuidad a partir de la etapa intermedia de la vida, sin distinción. El cuarto, que incluye a los mayores sociables, constituye algo más de un quinto de la muestra y se caracteriza por una densa red de amigos, relaciones paternas y vecinales y un alto índice de satisfacción personal y relacional. Estos individuos no consideran su edad como un límite y confirman un alto grado de actividad física. En último lugar, los mayores ocupados confirman un nivel de actividad de 360º. En este grupo se encuentran sobre todo varones de entre 65 y 69 años que todavía trabajan en puestos de alto rango o con ingresos altos, e invierten en el apoyo a las nuevas generaciones, participan en actividades organizadas en clubs, hacen ejercicio y fomentan altos grados de confianza en la gente y en la solidaridad social.

El índice de la entrevista relativo al uso de Internet y ordenadores en estos cinco clusters se detalla en la tabla. Tal y como se muestra, las TIC son irrelevantes para las mujeres más mayores expuestas al riesgo de exclusión (primer cluster), y para los cónyuges implicados en el apoyo familiar en el contexto de niveles socioeconómicos medio-bajos (tercer cluster); su presencia es nula o limitada en relación con parejas jubiladas dependientes del sector privado (segundo cluster) y con los individuos más sociables (cuarto cluster). La presencia del uso de TIC es notablemente mayor y más significativa en mayores ocupados (quinto cluster), especialmente para aquellos que gozan de mayores niveles actividad, están implicados con frecuencia en el mundo laboral y tienen una gran «dimensión generativa que incluye a la familia y el área social […] e identifica un perfil de individuos que disfruta de un nivel de satisfacción global» (Rossi, Bramanti & Moscatelli, 2014).

Por último, algunos indicios sobre la percepción del papel que juegan las TIC en la definición de la calidad de vida de los participantes se derivan de una batería de preguntas que describen los cambios experimentados a partir del uso de Internet. El 63,7% de los usuarios percibió cambios positivos en relación con la dimensión cognitiva (información sobre cuestiones de actualidad e intereses personales); el 36,3% menciona cambios positivos en la esfera de las relaciones sociales («Estoy en contacto con familia y amigos»), y en la percepción global de sus actividades («me siento más activo que mis compañeros que viven sin Internet»). Para muchos participantes, Internet es un recurso de conocimiento que utilizan para su salud y bienestar (40,3%), y para recopilar información relativa al tratamiento de sus enfermedades (29,9%). Otras áreas de cambio percibido afectan al concepto de gestión del tiempo: aproximadamente el 25% afirma ver menos la televisión, solo el 13,5% declara pasar demasiado tiempo frente al ordenador, y alrededor del 8% reconoce ser más sedentario y/o pasar más tiempo en el hogar. La incidencia de aquellos que pasan menos tiempo con sus seres queridos es incluso menor (2,2%).

Otro aspecto no desdeñable, aunque afecta a un grupo minoritario, es el temor asociado al uso de Internet: algunos mayores temen cometer errores o ver violada su privacidad (más del 20%), o temen no ser capaces de valorar la fiabilidad de las fuentes que encuentran en línea (18,7%). Para concluir, aunque el uso de Internet está acompañado, por lo general, de una percepción de mayor actividad e interacción social, la participación en actividades en línea o sin conexión, continúa siendo una práctica minoritaria (desde el 12,5% de aquellos que se sienten «más activos en la vida de mi comunidad local/comunidad/barrio», al 4,1% que expresa sus opiniones con mayor libertad en las redes sociales).

4. Discusión y conclusión

Los resultados de la encuesta presentada demuestran que:

• Pregunta 1a: los mayores digitalizados se presentan como una (significativa) minoría dentro de la población italiana con edades entre los 65 y los 74 años, y comparten características muy específicas, distintivas demográfica y relacionalmente con referencia a sus homólogos no digitalizados. Estos individuos tienen en primer lugar una situación económica y laboral estable, seguida de un mayor nivel educativo y un contexto relacional satisfactorio, así como un buen nivel de actividad física.

• Pregunta 1b: el contexto del hogar parece ser determinante para la adopción de las nuevas tecnologías e influencia su «buen uso»: el hogar es el lugar donde tiene lugar la mayor parte del consumo mediático, incluido el uso relacionado con los nuevos medios (27 accesos a los PC, 32,1 acceso a Internet en el hogar). El consumo de medios de comunicación por parte de los mayores se desarrolla en un contexto temporal y espacial, y produce procesos de domesticación mediática y rutinas que se comparten/negocian en el seno de la familia.

Más allá del hecho biológico de la edad, existen otros factores (personales, laborales, familiares, generacionales) que influencian la domesticación. Las experiencias profesionales concluidas, la relación con la familia, e incluso la organización espacial del hogar, son cuestiones que determinan fuertemente el acceso y el uso de las TIC.

• Pregunta 2a: Los mayores utilizan Internet extensiva y continuamente. La mayor parte de los (pocos) mayores que acceden a Internet son usuarios muy activos. El acceso a Internet es una práctica común enraizada e incorporada a la vida cotidiana de nuestra muestra: una vez que estas personas atraviesan el umbral del acceso, los individuos se convierten en usuarios maduros en todos los sentidos y dejan de ser visitantes ocasionales.

• Pregunta 2b: La tenencia y el uso de TIC es más frecuente en mayores caracterizados por buenos niveles de actividad física. No obstante, la respuesta a algunas preguntas de nuestro cuestionario (Ver 38: «Desde el uso de Internet...») señala que el uso prolongado y excesivo de Internet, además de múltiples cambios positivos, también puede identificarse en ocasiones como un problema en relación con la vida familiar, sus rutinas previas o las actividades potenciales que han dejado de realizar en detrimento del uso de Internet.

Entre los signos potenciales que revelan el papel ambivalente de las TIC encontramos que, en algunos casos, estas se utilizan como un intento para resolver dificultades. En una comparación aparentemente paradójica, aunque las correlaciones no fueron significativas, el uso de las redes sociales correlaciona inversamente con el índice de satisfacción relacional (rs=-.067; SL=0.45), y solo correlaciona débilmente con los índices de capital social, cuando se compara con el uso de ordenadores y de Internet. Esto parece indicar un uso compensatorio de las redes sociales debido a una red social débil o insatisfactoria más que una inversión en línea contrarrestada por un fuerte capital social fuera de las redes.

Estos resultados ayudan a contextualizar el fenómeno de la digitalización progresiva de los mayores en Italia en los términos de las dinámicas «clásicas» de la brecha digital, influenciadas por dimensiones socioeconómicas (Loges & Jung, 2001; Smith, 2014). Así, los mayores con alto poder adquisitivo, con un mayor capital cultural y social, y que han comenzado a utilizar el ordenador durante su carrera profesional, se caracterizan por una mayor susceptibilidad frente a la tenencia y el uso de TIC. Se trata de un fenómeno –el de la brecha digital en relación con los ingresos– que caracteriza de forma significativa los primeros estadios de la expansión de las TIC. En segmentos pobremente digitalizados, como es el caso de la población de edad avanzada en Italia, el itinerario de las TIC parece haberse extendido por medios «tradicionales», generando como consecuencia procesos de exclusión basados en los ingresos y en el capital social y cultural (Van-Dijk, 2005). De lo anterior se deriva que nos enfrentamos a una creciente polarización y radicalización entre ricos y pobres, en la que una considerable proporción de los mayores permanece desconectada y en riesgo de marginalización (debido a factores sociales más amplios), mientras que para una minoría de usuarios más acomodados (económica y socialmente), los medios digitales han penetrado en la vida diaria con gran fuerza, en términos de tiempo empleado y de inversión económica y relacional. Verdaderamente, el panorama podría cambiar en los años venideros: la llegada de una nueva generación de mayores que ha crecido en una sociedad más digitalizada e informatizada que la anterior (incluyendo la esfera profesional), puede diluir la centralidad de los niveles de ingresos y estatus que determina el fenómeno de la brecha digital. Desde este punto de vista, el enfoque generacional por un lado (Aroldi & Colombo, 2013; Loos, 2011), y la repetición de esta entrevista dentro de unos años, podrían ayudar a arrojar luz sobre la dirección que pueda tomar este fenómeno.

En relación con el vínculo que se establece entre las TIC y el bienestar, a la hora de realizar esta investigación no es posible indicar si la adopción de las tecnologías garantiza la inclusión y la participación. La difusión transversal de la tecnología entre los mayores no determina probablemente un alto bienestar para todos ellos: la adopción de las TIC y el envejecimiento activo requieren una investigación más amplia antes de poder comprender por completo el papel que desempeñan las tecnologías en la vida diaria de los mayores y en su organización relacional, espacial y temporal en el contexto doméstico (Haddon, 2000).

A partir de un marco teórico que contempla la domesticación y un enfoque etnográfico, emprendemos una segunda fase de nuestra investigación con un enfoque cualitativo con el objetivo de investigar la dimensión subjetiva del papel percibido de las TIC y la historia personal de «conversión» (Silverstone & Hirsch, 1992) de las tecnologías en significados tangibles y en valores que contribuyen a la igualdad en la vida de los mayores.

Para concluir, queremos añadir algunas consideraciones en términos de políticas y educación. Tal y como sugieren nuestros resultados, no podemos limitar la definición de envejecimiento activo a la tenencia de dispositivos tecnológicos o a su uso (Dickinson & Gregor, 2006): envejecimiento activo significa «calidad de vida», que también puede estar relacionado con –pero no determinado por– los múltiples usos de la TIC. Los resultados sugieren el desarrollo necesario de políticas digitales inclusivas y programas educativos que tengan en cuenta riesgos y beneficios, así como el complejo papel que juegan las tecnologías. Los procesos de inclusión digital deberían estar destinados a promover el «buen uso» –consciente, atento, reflexivo, moderado, respetando los contextos relacionales– de las TIC, y no simplemente la difusión de ordenadores, tabletas y smartphones para tratar –determinísticamente– los problemas derivados de la edad.

Apoyos y agradecimientos

Esta investigación ha sido apoyada por la Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Milán-Italia).

Notas

1 1.600 nombres se han extraído de la lista electoral de 90 municipios, usando el método sistemático. 900 son participantes. Error de muestreo: 3%. Intervalo de confianza: 0,05%.

2 El índice consiste en la elaboración de respuestas relacionadas con preguntas sobre la tenencia y el uso de las TIC (portátil o Netbook, ordenadores de mesa, tabletas, lectores de e-Book, Smartphone, WIFI, reproductor de MP3).

3 Preguntas relacionadas con la frecuencia de uso de ordenadores y la naturaleza de las actividades realizadas (copiar o mover archivos o carpetas, usar la función «cortar-pegar», calcular fórmulas en hojas de cálculo, transferir archivos de un ordenador a otros dispositivos, uso del correo electrónico, juegos on-line, consulta de noticias, consultas en Wikipedia, blogs, foros, contenido generado por el usuario, búsqueda de información relacionada con la vida diaria y la salud, realización de compras y tareas administrativas en línea).

4 Respuestas que contemplan el uso de Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube y otros servicios relacionados (participar en chats, compartir contenidos, escribir comentarios).

5 Trabaja/No trabaja.

6 Respuestas que contemplan la actividad profesional y el nivel educativo del participante, su pareja y su padre.

7 Soltero/a, casado/a, viudo/a, pareja de hecho, separado/a o divorciado/a.

8 Respuestas que contemplan la frecuencia de lectura y salidas a conciertos, espectáculos, museos, cursos.

9 Respuestas que contemplan la frecuencia de exposición, escucha y lectura en televisión, radio, periódicos y publicaciones semanales.

10 Respuestas que contemplan la participación en actividades deportivas, actividades al aire libre, baile, viajes, etc.

11 Respuestas que contemplan la percepción reflexiva de los participantes con respecto a su edad.

12 Respuestas que contemplan la satisfacción individual en relación con los ingresos, la salud, el trabajo, el lugar de residencia y elementos espirituales.

13 Respuestas que contemplan el interés mostrado y la confianza en otros (compatriotas, extranjeros europeos, personas con discapacidad, niños, desempleados, mayores).

14 Respuestas que contemplan la opinión sobre la conveniencia y las dinámicas de colaboración entre usuarios jóvenes y de edad avanzada.

15 Respuestas que contemplan opiniones sobre responsabilidad mutua entre padres e hijos.

16 El software estadístico utilizado para agrupar los clusters es SPAD, que los obtiene mediante dos fases de agrupamiento (Lanzetti, 1995: 81-99).

Referencias

Aroldi, P., & Colombo, F. (2013). La terra di mezzo delle generazioni. Media digitali, dialogo intergenerazionale e coesione sociale. Studi di Sociologia, 3-4, 285-294. (http://goo.gl/rmTSlU) (10-10-2014).

Aroldi, P., Carlo, S., & Colombo, F. (2014). «Stay Tuned»: The Role of ICTs in Elderly Life. In G. Riva, P. Ajmone, & C. Grassi (Eds.), Active Ageing and Healthy Living: A Human Centered Approach in Research and Innovation as Source of Quality of Life. (pp. 145-156). Amsterdam: IOS Press. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-425-1-145

Dickinson, A., & Gregor, P. (2006). Computer Use has no Demonstrated Impact on the Well-being of Older Adults. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 64(8), 744-753. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2006.03.001

European Commission (2011). Active ageing, Special Eurobarometro 378. Bruxelles: EU Publishing. (http://goo.gl/c6BfB) (10-10-2014).

Haddon, L. (2000). Social Exclusion and Information and Communication Technologies: Lessons from Studies of Single Parents and the Young Elderly. New Media and Society, 2(4), 387-406. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1461444800002004001

Hargittai, E. (2002). Second-Level Digital Divide: Differences in People’s Online Skills. First Monday, [S.l.], apr. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v7i4.942

ISTAT (2013). Cittadini e nuove tecnologie. Roma: Pubblicazioni Istat. (http://goo.gl/LTTvn2) (10-10-2014).

Lanzetti, C. (1995). Elaborazioni di dati qualitative. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Loges, W.E., & Jung J.Y. (2001). Exploring the Digital Divide: Internet Connectedness and Age. Communication Research, 28(4), 536-562. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/009365001028004007

Loos, E.F. (2011). Generational Use of New Media and the (ir)relevance of Age. In F. Colombo, & L. Fortunati (Eds.), Broadband Society and Generational Changes. (pp. 259-273). Berlin: Peter Lang.

Naumanen, M., & Tukiainen, M. (2009). Guided Participation in ICT-education for Seniors: Motivation and Social Support, Frontiers in Education Conference, 2009. FIE ‘09. 39th IEEE, 1-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/FIE.2009.5350544

Olve, G.N., & Vimarlund, V. (2006). Elderly Healthcare, Collaboration and ICTs - Enabling the Benefits of an Enabling Technology. VINNOVA. Stockholm: Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems Publishing. (http://goo.gl/ZySpnK) (10-10-2014).

Riva, G., Ajmone-Marsan, P., & Grassi, C. (2014) (Eds.). Active Ageing and Healthy Living: A Human Centered Approach in Research and Innovation as Source of Quality of Life. Amsterdam: IOS Press. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-425-1-57

Rossi, G., Boccacin, L., & Moscatelli, M. (2014). Active Ageing and Social Generativity: Social Network Analysis and Intergenerational Exchanges. A Quantitative Study on a National Scale. Sociologia e Politiche Sociali. Milano: Franco Angeli, pp. 33-60.

Saunders, E.J. (2004). Maximizing Computer Use among the Elderly in Rural Senior Centers. Educational Gerontology, 30(7), 573-585. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03601270490466967

Selwyn, N. (2004). The Information Aged: A Qualitative Study of Older Adults’ Use of Information and Communications Technology. Journal of Ageing Studies, 18, 369-384. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2004.06.008

Silverstone, R., & Hirsch, E. (1992) (Eds.). Consuming Technologies: Media and Information in Domestic Space. London: Routledge.

Smith, A. (2014). Older Adults and Technology Use. Pew Research Center. (http://goo.gl/6nMNra) (10-10-2014).

Sourbati, M. (2008). On Older People, Internet Access and Electronic Service Delivery. A Study of Sheltered Homes. In E. Loos, L. Haddon, & E. Mante-Meijer (Eds.), The Social Dynamics of Information and Communication Technology. (pp. 95-104). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Van-Dijk, J. (2005). The Deepening Divide: Inequality in the Information Society. London: Sage.

Warschauer, M. (2002). Reconceptualizing the Digital Divide. First Monday, [S.l.], jul. 2002. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v7i7.967

Document information

Published on 30/06/15

Accepted on 30/06/15

Submitted on 30/06/15

Volume 23, Issue 2, 2015

DOI: 10.3916/C45-2015-05

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?