Summary

Pseudoachalasia, or secondary achalasia, caused by neoplasms is a rare entity. We describe a case of pseudoachalasia in an 80-year-old woman who presented with a 2-month history of progressive dysphagia and postprandial vomiting. An esophagogram demonstrated a markedly dilated esophagus with a typical “bird-beak” appearance of the gastroesophageal junction, indicative of achalasia. However, esophageal manometric study disclosed normal peristalsis of the esophagus, not suggestive of a typical feature of achalasia. Abdominal computed tomography scan demonstrated a hypovascular tumor in the left lobe of the liver, extending to the gastroesophageal junction and proximal lesser curve of the stomach. The patient underwent a palliative gastrostomy with a liver biopsy. Finally, cholangiocarcinoma was diagnosed based on the pathological findings. Despite its rarity, clinicians should be aware of this finding as a potential cause of dysphagia in elderly patients.

Keywords

Cholangiocarcinoma ; Esophageal manometry ; Esophagogram ; Pseudoachalasia

Introduction

Achalasia is a disorder characterized by functional obstruction at the gastroesophageal (GE) junction. The disease is secondary to increased resting lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure, failure or incomplete relaxation of the LES with swallowing, and absence of or abnormal peristalsis in the body of the esophagus on swallowing [1] . It can be divided into two major categories: primary (idiopathic) achalasia and secondary (pseudoachalasia) achalasia. The pathogenesis of idiopathic achalasia involves the selective loss of inhibitory neurons of the myenteric plexus, which produces vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, nitric oxide, and inflammatory infiltration, and is responsible for the unopposed excitation of LES, thereby causing dysfunction or failure of the LES relaxation in response to each swallow [2] . The pathogenesis of pseudoachalasia involves mechanical obstruction of the distal esophagus or an infiltration of the malignancy that affects the inhibitory neurons of the myenteric plexus [3] . Herein, we describe a rare case of pseudoachalasia caused by cholangiocarcinoma.

Case report

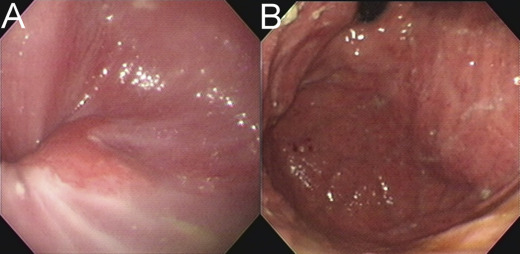

An 80-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to our hospital with a 2-month history of progressive dysphagia and postprandial vomiting. She also experienced poor appetite and weight loss of 6–7 kg during this period. She underwent an appendectomy for acute appendicitis at another hospital 3 months previously. One month after the operation, she presented with epigastralgia; an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed erosive gastritis. However, she had progressive dysphagia and postprandial vomiting despite medical treatment. She was referred to our hospital, where EGD showed erosive esophagitis (Fig. 1 A). There was no tumor lesion in the gastric cardia, from retroflexion of the endoscope (Fig. 1 B). Moreover, a radionucleotide esophageal transit study also revealed GE reflux. Proton pump inhibitors and prokinetic agents were administered, but they showed a poor response to the patient. Subsequently, she was admitted to our hospital for further investigation 1 month later.

|

|

|

Figure 1. Initial esophagogastroduodenoscopy. (A) Erosive esophagitis is identified in the gastroesophageal junction. (B) There is no tumor lesion in the gastric cardia, from retroflexion of the endoscope. |

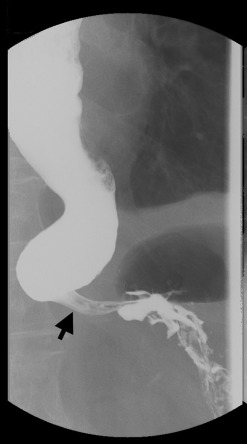

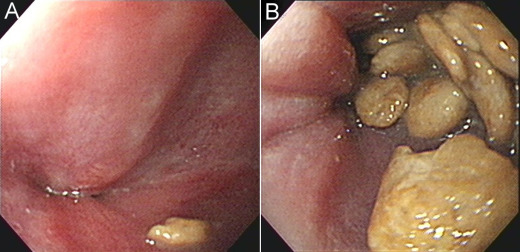

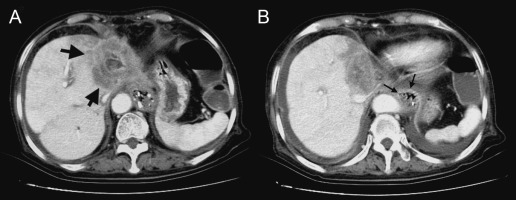

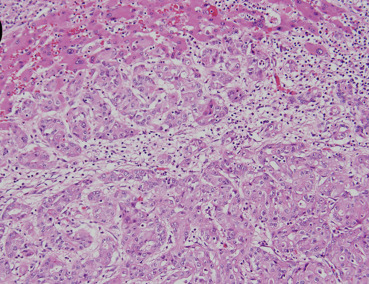

Physical examination demonstrated a thin woman. Her height was 158 cm and weight 48 kg. Her abdomen was soft without rebound tenderness. The laboratory tests were normal, apart from hypokalemia (K 3.4 mmol/L, normal range 3.5–5.3 mmol/L) and normocytic anemia (Hb 11.9 g/dL, normal range 12–14 g/dL). An esophagogram demonstrated a markedly dilated esophagus with a “bird-beak” appearance at the GE junction (Fig. 2 ). Idiopathic achalasia was preliminarily diagnosed based on the above findings, although the patients age and short duration of symptoms were not consistent with the diagnosis. Repeated EGD demonstrated a very tight GE junction (Fig. 3 A) with retention of some food residues and pills in the lower third of the esophagus (Fig. 3 B). Besides, the endoscope could not pass the GE junction into the stomach. However, esophageal manometry demonstrated a normal pattern of esophageal peristalsis. Based on the endoscopic findings and manometric features, pseudoachalasia was suspected. Abdominal computed tomography demonstrated a hypovascular tumor in the left lobe of the liver (Fig. 4 A, arrows). Moreover, the tumor encased the lower end of the esophagus (Fig. 4 B, arrows). Thus, the diagnosis of pseudoachalasia caused by liver tumor was made. At laparotomy, the liver tumor was deemed unresectable and biopsy specimens were taken. A pathological examination of the biopsy specimens showed cuboidal tumor cells with pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nuclei arranged in a ductular or glandular pattern within the desmoplastic stroma, the findings being consistent with cholangiocarcinoma (Fig. 5 ). Finally, the patient died due to disease progression 1 year later.

|

|

|

Figure 2. Esophagogram demonstrating a markedly dilated esophagus with a “bird beak” tapering at the gastroesophageal junction (arrow). |

|

|

|

Figure 3. Repeated esophagogastroduodenoscopy. (A) A very tight gastroesophageal junction is found. (B) Retention of food residues and pills are identified in the lower third of the esophagus. |

|

|

|

Figure 4. Abdominal computed tomography. (A) A hypodense tumor located in the left lobe of the liver (arrows). (B) The tumor encased the gastroesophageal junction of the esophagus (arrows). |

|

|

|

Figure 5. Pathological examination of the biopsy specimens of the tumor demonstrates cuboidal tumor cells with pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nuclei arranged in a ductular or glandular pattern within desmoplastic stroma, confirming the diagnosis of a cholangiocarcinoma (hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification 200×). |

Discussion

Pseudoachalasia is an infrequent motility disorder of the esophagus, accounting for approximately 4% of all cases of achalasia [4] . The most common etiologies are primary or metastatic tumors, secondary amyloidosis, and peripheral neuropathy as a sequela of GE surgery. Rare causes of pseudoachalasia are neurological disorders, paraneoplastic syndromes in the context of small-cell adenocarcinoma of the lung, carcinoma of the cardia, and pleural mesothelioma [3] . Adenocarcinoma of the GE junction accounts for most cases of malignant pseudoachalasia [2] , although other tumor types, including lymphoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, pleural mesothelioma, bronchogenic cancers, pancreatic cancers, prostatic cancers, colonic cancers, and renal cell carcinomas, have also been implicated [5] . Pseudoachalasia caused by cholangiocarcinoma is extremely rare, and only two cases have been reported in the English literature [6] ; [7] . The two cases occurred in the Asian population, which is not surprising considering that the prevalence of cholangiocarcinoma is significantly higher in Asian countries than in Western countries. Cholangiocarcinoma is a common primary liver cancer in East Asia, where fluke infestations, hepatolithiasis, and recurrent pyogenic cholangitis are prevalent [1] . The most common manifestations of cholangiocarcinoma are painless jaundice, pruritus, right upper-quadrant abdominal pain, and weight loss. These symptoms and signs are accompanied by markedly elevated levels of serum bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase. Interestingly, our patient presented with dysphagia and postprandial vomiting but without hyperbilirubinemia. Although dysphagia has been reported as a presenting symptom in a patient with metastatic cholangiocarcinoma in the paraesophageal lymph nodes, our patient had manometric and radiographic features of achalasia, together with clinical features suggestive of gastroparesis [4] . Three mechanisms have been proposed for tumor-associated pseudoachalasia. The first involves encirclement or compression of the distal esophagus by the tumor, thereby producing a constricting segment. The second mechanism is that malignant cells infiltrate the esophageal myenteric plexus, which in turn impairs postganglionic innervation of the LES. The third proposal is that the tumor directly affects the vagus nerves to cause achalasia-like features.

It is often difficult to distinguish between pseudoachalasia and idopathic achalasia based on the clinical features, radiologic images, and endoscopic findings. Certain historical features can help raise the suspicion of the presence of a malignant tumor. A short duration of symptoms (<1 year), presentation later in life (at the age of 50–60 years), and unexplained weight loss (6.8–9.0 kg) are all more typical of malignancy than of idiopathic achalasia [8] ; [9] . Although a few studies have reported that these criteria are poor predictors of malignancy and are not especially helpful in individual cases, the clinical features of our patient were all compatible with the abovementioned criteria. Moreover, esophageal manometric findings of a hypertensive (48 mmHg), nonrelaxing LES and a total lack of esophageal peristalsis may be indicative of achalasia. In our present case, an esophagogram demonstrated a markedly dilated esophagus with a typical bird-beak appearance, leading to the initial diagnosis of idiopathic achalasia. However, repeated EGD showed stenosis of the GE junction, and esophageal manometry revealed a normal pattern of esophageal peristalsis, not suggestive of idiopathic achalasia. A reasonable explanation for the presentation of pseudoachalasia in our patient is that the tumor cells encircled the distal esophagus, producing a constricting segment, but did not infiltrate the esophageal myenteric plexus or directly affect the vagus nerves.

EGD is a useful modality to exclude esophageal from gastric tumor-induced pseudoachalasia; however, extramural tumors will inevitably be missed. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan can offer high-resolution images of the esophageal wall and has been used to differentiate patients with achalasia from those with pseudoachalasia. For example, the wall is more symmetric and demonstrates less substantial thickening in achalasia patients than in pseudoachalasia patients [10] . Endoscopic ultrasound offers high-resolution images of the esophageal wall and can, therefore, be used to differentiate patients with primary achalasia from those with pseudoachalasia.

Pneumatic dilation provides a safe, effective, and relatively inexpensive option for the management of achalasia [11] . The most common complication of pneumatic dilations is esophageal perforation. The less common complications are intramural hematoma, diverticula at the gastric cardia, mucosal tears, reflux esophagitis, prolonged postprocedure chest pain, hematemesis, fever, and angina. Pneumatic dilation may improve pseudoachalasia of a benign etiology and may provide a complete recovery from stenosis. By contrast, pneumatic dilation is an ineffective treatment for a malignancy-associated pseudoachalasia stenosis and delays adequate therapy of the underlying disorder. Surgical resection is the best treatment method for pseudoachalasia caused by tumors. Moreover, a feeding bypass via palliative gastrostomy or jejunostomy may be necessary. Metallic stenting, palliative chemotherapy, and radiotherapy are alternative methods for managing unresectable tumors.

In conclusion, pseudoachalasia caused by cholangiocarcinoma is an extremely rare entity, but it must be considered in elderly Asian patients who present with idiopathic postprandial vomiting and dysphagia. A feeding bypass via palliative gastrostomy is necessary in most cases.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1] J.W. Leung, A.S. Yu; Hepatolithiasis and biliary parasites; Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol, 11 (1997), pp. 681–706

- [2] W. Park, M.F. Vaezi; Etiology and pathogenesis of achalasia: the current understanding; Am J Gastroenterol, 100 (2005), pp. 1404–1414

- [3] I. Gockel, V.F. Eckardt, T. Schmitt, T. Junginger; Pseudoachalasia: a case series and analysis of the literature; Scand J Gastroenterol, 40 (2005), pp. 378–385

- [4] P.J. Kahrilas, S.M. Kishk, J.F. Helm, W.J. Dodds, J.M. Harig, W.J. Hogan; Comparison of pseudoachalasia and achalasia; Am J Med, 82 (1987), pp. 439–446

- [5] F.D. Manela, E.M. Quigley, F.F. Paustian, R.J. Taylor; Achalasia of the esophagus in association with renal cell carcinoma; Am J Gastroenterol, 86 (1991), pp. 1812–1816

- [6] V.K.S. Leung, P.S. Kan, M.S. Lai; Cholangiocarcinoma presenting as pseudoachalasia and gastroparesis; Hong Kong Med J, 9 (2003), pp. 296–298

- [7] U.C. Ghoshal, S. Sachdeva, A. Sharma, D. Gupta, A. Misra; Cholangiocarcinoma presenting with severe gastroparesis and pseudoachalasia; Indian J Gastroenterol, 24 (2005), pp. 167–168

- [8] H.J. Tucker, W.J. Snape Jr., S. Cohen; Achalasia secondary to carcinoma: manometric and clinical features; Ann Intern Med, 89 (1978), pp. 315–318

- [9] R.W. Rozman Jr., E. Achkar; Features distinguishing secondary achalasia from primary achalasia; Am J Gastroenterol, 85 (1990), pp. 1327–1330

- [10] M. Carter, R.C. Deckmann, R.C. Smith, M.I. Burrell, M. Traube; Differentiation of achalasia from pseudoachalasia by computed tomography; Am J Gastroenterol, 92 (1997), pp. 624–628

- [11] V.F. Eckardt, C. Aignherr, G. Bernhard; Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation; Gastroenterology, 103 (1992), pp. 1732–1738

Document information

Published on 15/05/17

Submitted on 15/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?