Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

With the transformation of Spain into an immigration country, society has become a major change by setting up a social space characterized, increasingly, by cultural, ethnic and religious diversity. In this new frame is interesting to investigate the overall value of diversity into the Spanish society. The two aims for of this paper are, on one hand, to process feedback on Spanish opinion on immigration between 1996 and 2007, and, on the other hand, to find out the role of the media in the construction of that opinion. For the first aim, an index of anti-foreigner sentiments was constructed using data provided by the national survey on opinions and attitudes on immigration, published annually by ASEP. For the second, an analysis, using the Agenda-Setting Theory, of articles published on immigration that appeared in the newspapers, «El País» and «El Mundo». The results show that a negative sentiment towards the outgroup has increased over time. The main variables explaining these trends are a sense of threat, to the population and to identity, and competition for resources and political decisions in integration – legalisation. The media analysis has six dimensions, the main ones refer to the illegality of the phenomenon, linking immigration to crime, and the social integration policies, highlighting the role of the media in creating public opinion.

1. Introduction

In just a few decades Spain has seen a substantial increase in its immigrant population. According to the National Institute of Statistics (INE), there were only 542,314 foreigners in Spain in the mid-nineties. This figure rose to 1,370,657 at the beginning of the millennium and, according to the latest data published in January 2011, currently stands at 5,730,667. This is the sharpest rise in the number of foreign residents in any member state of the European Union.

The arrival of immigrants from all over the world, forming the largest cultural melting pot in the country’s history, has not gone unnoticed by native Spaniards. The Centre for Sociological Research (CIS), in its monthly surveys, shows that Spanish attitudes towards immigrants have changed significantly in recent years. In 1996, a majority was in favour of immigration, judging it as necessary and not excessive in terms of the number of arrivals, whereas today there is more xenophobia directed at or rejection of the immigrant (Cea D’Ancona, 2009; Díez Nicolás, 2005; Pérez & Desrues, 2005), although this is not the result of a linear process. More specifically, in 2000 immigration was considered to be the fourth most pressing issue after ETA terrorism, unemployment and the economy. In 2006, 38.3% of Spaniards stated that immigration was the most important problem faced by the country, rising to second place after unemployment. According to the latest 2010 survey, immigration has dropped back to fourth place behind unemployment, the economy and the state of the mainstream political parties.

The transformation of a social phenomenon such as immigration into a social problem is a process in which many different agents play a part, the most prominent being the communications media. Cachón (2009) points to the media as responsible for turning immigration into a contentious public issue, since an event reported in a particular way can foment discrimination and social exclusion (Van Dijk, 2003). In the wake of the Agenda-Setting Theory, it has been shown that perception of social issues is largely conditioned by media reporting (Dearing and Rogers, 1996; Scheufele, 2000). This framing is related to two basic operations, selecting and emphasizing expressions and images to attribute a viewpoint, a perspective or a certain angle according to the given information. As understood by Valkenburg, Semetko and de Vreese (1999:550), «A media frame is a particular way in which journalists compose a news story to optimize audience accessibility».

Studies developed from this theoretical perspective demonstrate that the greater the media emphasis on a certain subject or social issue, the greater the public concern it generates, such as in the case of migration (Brader, Valentino & Suhay, 2004; Igartua & Muñiz, 2005; Igartua & al., 2007). Igartua & al. (2004) found a significant positive correlation between the number of news items published in the newspapers and the percentage of interviewees who indicated that immigration was a problem for the country. This association demonstrates that news coverage can convert the migratory phenomenon into a perceived social problem and, thereby, into a source of prejudice and stereotyping that can lead to racism.

The dual purpose of this article is to present the evolution and variables that define public opinion regarding the outgroup using an anti-immigration sentiment index, and to find out how Spain’s communications media cover this phenomenon, since we believe they represent the first step in cementing such feelings.

We have chosen two different time periods for this longitudinal analysis: 1997/1998, during which Spain was in economic recession but the immigrant population was small; and 2006/07, when the immigration rate was high and economic expansion was peaking but also showing signs of imminent stagnation and recession.

2. Method and data

For the first objective, we collected data from a national survey by the polling company «Análisis Sociológicos, Económicos y Políticos» (ASEP). Between 1995 and 2007, it carried out several statistically significant surveys, with the same items throughout, on the attitudes of the Spanish adult population towards foreigners. The sample was proportionally stratified by the number of immigrants settled in the various autonomous regions. The data were collected at random. For the two-year period 1996/1997, the aggregated sample comprised 2,413 people. In 2006/07, 2,405 people were surveyed. The matrix was completed with official statistics on the foreign population and unemployment rate.

The Anti-Immigrant Sentiment Index (Semyonov & al., 2006) was used to measure the attitude of Spaniards towards immigration. This model is based on the following four items, «Immigration will cause Spain to lose its identity» (Agree=1), «Influence of immigration on unemployment» (Increase=1), «Influence of immigration on Spanish salaries» (Decrease=1); and «Influence of immigration on delinquency» (Increase=1). The index varies from 0 to 4, where 4 represents the strongest anti-immigrant attitude.

However, as Cea d’Ancona (2009) points out, the measurement of xenophobia through surveys has limitations that exceed the technique itself, basically due to the social desirability bias defined by the stigma of admitting to racist sentiment. Any declaration or behaviour deemed to contravene the constitutional principles of equality and non-discrimination is liable to censure and even prosecution.

In order to find the variables that best predict this sentiment we carried out a regression analysis, taking into account the following dimensions: threat, insecurity and social rights (Cea d’Ancona, 2009). Threat is measured, on the one hand, by the real size of the foreign population, i.e., the rate of foreigners, and the perceived size (Quillan, 1995; 1996; Schenider, 2008; Schlueter & Scheepers, 2010; Semyonov & al., 2008), with a score of (1) for agreeing with the statement that there are too many immigrants in Spain, and on the other hand by identity threat, which is visible in the perception of conflict in questions of identity, measured by the extolling of either ethnic or civic virtues. To do this, we used the variable effects that immigration has on Spanish culture (bad or very bad=1), typical of an ethnic identity.

Insecurity, derived from threat, is expressed via two elements: one material, quantified by the attitude of only admitting immigrants when there are no Spaniards to carry out the activity (Agree=1), and the unemployment rate. And, political insecurity, referred to in two questions related to migratory policy and the granting of citizenship (Díez Nicolás, 2005). The first element is: «The economic situation is complicated enough for Spaniards let alone allotting money to help immigrants» (Agree=1) and the second: «The best attitude towards illegal immigrants» (legalize them=1).

Social distance, understood as the lack of interaction with immigrants, is constructed by three dimensions used in intergroup contact (Allport, 1954; Escandell & Ceobanu, 2009), that is, intense if they have a close affective relationship (No=1), occasional if they have ever had a long conversation (No=1), and at the workplace, when there is a labour relationship with foreign workers (No=1).

Finally, the variables on individual character are also extremely important in predicting anti-immigrant sentiment (Coenders & Scheepers, 2008): Sex (male=1), age (in years), education (university=1), income (lowest quartile =1), political orientation (right=1), activity (unemployed=1) and marital status (married=1).

Two national newspapers were chosen to gauge news treatment of immigration, «El País» and «El Mundo». All news items referring to immigration in the standard two-year reporting phases, 1997/98 and 2006/07, were taken as recommended by Lorite (2007), excluding new items from vacation periods. Also exempt from analysis were news stories about migration in which immigrants were not the protagonists. In all, the study used 217 news items from both newspapers.

News frames were established by news type and factor analysis (Igartua & al., 2005; Muñiz & al., 2008). News items where the description of the event or its consequences could be judged undesirable for immigrants, for example crime, were coded negative. Information was coded neutral or ambiguous when no negative or positive slant towards immigrants was observed, and positive if the event or its consequences were desirable, such as legalisation.

3. Results

We first analysed the intensity and evolution of anti-immigrant sentiment and the variables that define it. Later, we examined the communications media’s frame and treatment of news about immigration.

The initial result of the longitudinal study is the gradual increase in anti-immigrant sentiment in Spain. Whereas in 1997 the mean was 1.4, in 2007 it had risen to 2.1 (see Graph 1). In other words, the foreigner is identified more and more as a generator of unemployment, delinquency, lower salaries and an enemy of cultural identity. This evolution occurs during three distinct time periods within the 10 years analysed. Sentiment in 1997-1999 remains almost constant at around 1.4. With the beginning of the new millennium, rejection jumps to 2.1, and from 2004 to 2007 it again increases, to 2.4. As Blalock (1967) suggests, there is no linear growth in Spanish attitudes towards the outgroup.

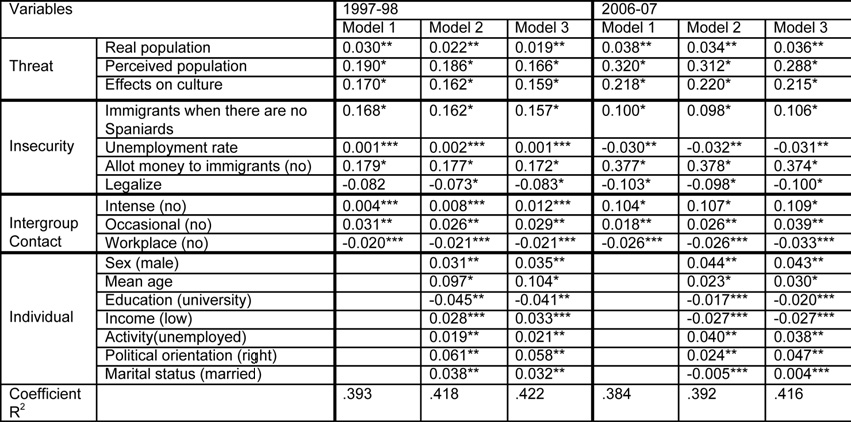

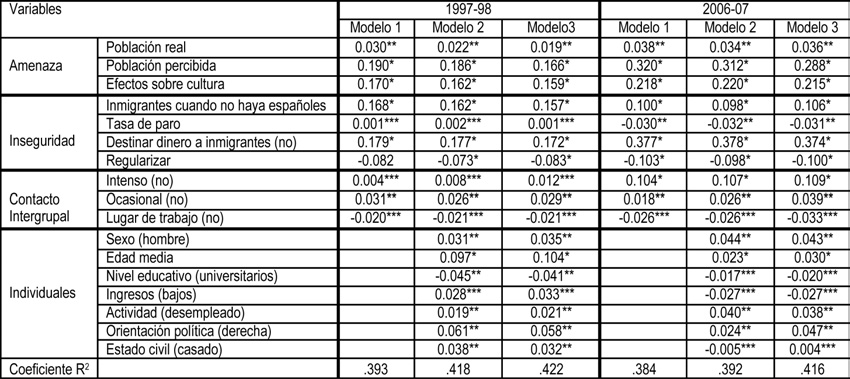

In the second stage of the analysis, two regression models were estimated based on the individual and contextual variables (Table 1). In Model 1, we examined the role of threat and insecurity, and intergroup contact variables in the construction of anti-immigrant sentiment. In Model 2, we added the individual variables.

In the first model, in 1997/1998 both the threat and insecurity variables are seen as the best explanation for the sentiment, in this order of importance: perceived threat, money allotted to integration policies, negative effects on the host culture and allowing immigrants to enter when there are no Spaniards to perform the activity, all positively signalled, explaining 39.3% of the variance of anti-immigrant sentiment. In other words, the stronger the sensation of invasion and money allotted to integration policies, and the more they think that immigration has negative effects on the culture, and that immigrants should only be allowed to enter when no Spaniards can be found to occupy the job, the stronger the negative sentiment is. The size of the real population appears to have less weight, and negatively, legalizing immigrants. In the contact variables, only occasional contact appears statistically significant, so the more often they have a long conversation with a foreigner, the less negative the perception of the outgroup is.

In 2006/2007, the variables increased their weight in explaining the sentiment. Rejection of allotting money to immigrant integration policies was important, followed by population and cultural threat, and admitting immigrants when there are no Spaniards to do the job. Legalisation again appeared in negative and, with fewer incidences than in the previous period, the unemployment rate. Concerning intergroup contact, statistically significant intense relationships appeared for the first time, such that the more intense contact is, the less xenophobia is aroused.

Therefore, the perceived threat created by various agents and institutions, and economic and political competition is more important in creating sentiment towards foreigners than the real population size or the unemployment rate, even when the immigration rates are relatively low, as occurred in 1997/1998.

In the second model, the data corresponding to threat, insecurity and intergroup contact remained almost constant with the individual variables. In 1997/1998, negative sentiment towards the outgroup was predicted by, in this order: age, political orientation, education, negatively, marital status, sex and unemployment. In other words, being older with a conservative ideology and low-level of education, married, male and unemployed revealed itself in anti-immigrant sentiment.

In 2006/2007, unemployed and male are the most important socio-demographic variables, even though unemployment was at its lowest during the period analysed. Also, education and income lost predictive ability during this period.

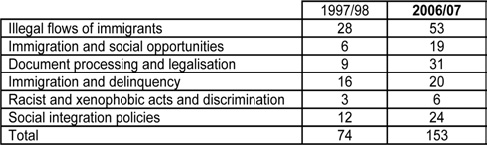

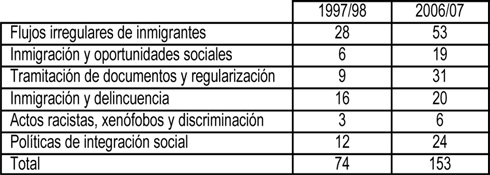

How, then, is this sentiment constructed? The elements that contribute to constructing the view of otherness are multiple and of different depths. In our interest to discover the role of the communications media in configuring this process, as shown in Table 2, we found that there was a considerable increase in the number of news items from the first to the second two-year period. There are two main reasons for this: the huge increase in the number of immigrants at that time, and immigrant demands and related political action. For example, in 2006, the fallout from legalisation passed the year before could still be felt, especially because of the so-called «call effect» it may have generated. In the space of 10 years, the migratory phenomenon went from being a matter of secondary importance to being a top priority on political and social agendas.

Delving deeper into the analysis, news items published in both periods were found to have had a distinctly negative character. In 1996/1997, 65% of the news items had a negative profile and only 18% highlighted the positive aspects of immigration, and in 2006/2007, negative news items rose to 69% and the positive to 21%. We find headlines citing undetailed affirmations by political and religious leaders, etc., such as: «An Islamic centre endangers coexistence in the Babel of Extremadura» (El Mundo, 17/8/2006); «Muslims ask for the «Moros y Cristianos» fiestas to be eliminated as unfitting for Spanish democracy» (El Mundo, 5/10/2006); «Islamic fundamentalism and immigration threaten Europe» (El Pais, 10/10/2006); «Living here is to die over a slow fire» (El País, 28/10/2006).

The increase in positive news also responds to migrations over time that aroused less suspicion in journalists, especially during times of economic expansion, such as the period from 1997 to 2007.

Six news frames resulted from the factor analysis: 1) illegal flows of immigrants (entering the country in makeshift boats, hidden inside lorries, etc.); 2) immigration and social opportunities (job market, housing, social services, etc.); 3) processing documents and legalisation of immigrants; 4) immigration and delinquency (crime, mafias, etc.); 5) racist and xenophobic acts, and discrimination; 6) social integration policies (central, regional and local governments). We might add that, with exceptions, each news item only fits into one frame.

The top frame in 2006/2007 is illegal flows of immigrants, followed by document processing and legalisation, while immigration and crime appear most frequently in 1997/1998; the third frame in both periods refers to social integration policies. The, smallest number of frames are for racist acts, xenophobia and legalisation on the one hand, and immigration and social opportunities on the other. The news frames say little about the positive effects of immigration on the host country, such as the economic contribution of immigrants to the State or its importance in a nation’s development. Neither do they touch on the immigrants’ experiences of discrimination or racism that they are subjected to almost daily, as reported by SOS Racismo. However, the social opportunities frame increased considerably in 2006/07, coinciding with the economic boom.

4. Discussion and conclusions

This article analyses the image of foreign immigrants in Spain, since the opinions and attitudes towards immigrants represent new forms of racism and xenophobia. For this we took two different time periods, one that coincided with economic recession and low immigration rates, and the other at the high point of economic expansion and migratory consolidation.

The data show that hostility towards immigrants increased over a 10-year period. Whereas in 1997/98 the index showed a mean of 1.4, in 2006/07 it had risen to 2.4. However, this trend is not just explained by the increase in the real population over a short time. This is only the trigger at the beginning of immigrant entry flows, as the variables predicting the sentiment in 1997/98 are not far from those 10 years later. Therefore, the sentiment responds to daily and/or institutionalised discursive practices dictated mainly by the communications media.

The construction of immigration is not per se through numbers or immigration inflows but responds to a symbolic construction, the product of speeches from a variety of actors and social scenes, in which the communications media are preeminent. Suffice it to recall that the top news frame in both periods referred to illegal entry flows. Thus when referring to figures on immigration, metaphors are used to quantify the flows as: a wave, avalanche, invasion, etc., descriptions that promote the idea that there are too many immigrants and which provoke hostility and fear. «El Pais» expressed it like this in an article (8/8/1998): «Immigration: the tide grows». As a result, the immigrant is transformed by the host’s fear of hyper-foreignization. In other words, immigration is seen as a problem rather than a phenomenon typical of international society presented with a new challenge.

But the threat transcends the numerical to become consolidated in identity (Schiefer & al., 2010; Schwart, 2008). As we are reminded by Worchel (1998), any type of group identity serves as a basis for conflict, especially when ethnic content is assigned to it based on stereotypes;, so, certain groups come to be conceptualized as culturally incompatible. They are distinguished by the exaggeration of cultural differences through subtle prejudice. Culture is perceived as a hereditary trait that nobody can shed, or that, «there is a genealogical, and therefore, racial conception of the culture and its transmission» (Todd, 1996: 343). Immigrants are faced with open rejection or subordinate «integration» since the beliefs of the others are almost always seen as containing elements of fundamentalism, the equivalent of a focus of conflict, especially if this involves Muslims, who are the archetype. Therefore, the best response to this situation, according to native Spaniards, is cultural assimilation but denial of full citizenship rights, which is acceptable even to those locals who do not consider themselves racists.

Consequently, Spaniards believe that the continual arrival of foreigners has a negative effect on the national culture, and money should not be allotted to their integration, nor should they be legalized. Moreover, in the speeches of some politicians that appear in the communications media, semantic structures prevail that stress the difference in appearance, culture and behaviour, or deviation from norms and values, and which take the form of slogans such as, «defend your identity», «defend your rights». This is boosted by a nationalist awareness, one in particular that has an ethnic basis. They demand of others what the native Spaniard would not ask of himself. Spanish identity has been configured in opposition to the other and defined on the basis of dimensions of an abstract and symbolic nature rather than on quality.

The feeling of threat is complemented by competition for limited resources such as jobs, housing, healthcare, etc., which also leads to a magnification of the immigrant presence. This is a response to news frames, or in other words, to immigration and social opportunities, and not to positive aspects such as the contribution to economic development, rather to the negative, and the excess demand for resources. Thus most Spaniards think that foreigners should only be accepted in situations where there are no Spaniards to the job required. Following on from this, economic insecurity is accentuated in times of recession as, supposedly, it reduces labour market opportunities and lowers the quality of the jobs available. Nevertheless, our study shows this to be secondary in the case of a negative sentiment towards the outgroup, since in 1997 Spain was in the midst of an economic crisis that raised unemployment to record levels and the number of foreigners in the country was the lowest among the then 15-member European Union; however, xenophobia was lower than in the two later periods, especially in 2006/07 when the country experienced its highest ever economic growth and lowest unemployment rates but, by contrast, the immigration rate stood at over 10% of the population. This is also confirmed first by the fact that unemployment in the first period was statistically insignificant in predicting variability in anti-immigration sentiment, while it was statistically significant in the other two periods; secondly because being unemployed carried greater predictive weight during economic expansion and when the immigration rate is at its highest.

This is due to the fact that the labour market occupied by immigrants (mainly agriculture and construction) complemented that dominated by native Spaniards. In fact, labour discrimination against the immigrants gave locals access to jobs for which they were initially unqualified. However, immigrants then started to move into other labour sectors (services, for example) in which they competed directly for jobs with the national population, especially with those nationals who were at a disadvantage in terms of social and human capital. At the same time, immigration featured more prominently as a newsworthy topic, and in the 10-year period analysed the number of news items on immigration doubled, especially those with a negative slant. Moreover, the national population also perceived competition for welfare state benefits (housing, education and healthcare). They would, therefore, be prepared to accept the award of a minor payment towards the integration of immigrants, or they would legalize them. This is what Zapata (2009) calls the governance hypothesis, such that if the government confronted immigrant integration inclusively, offering them civic instead of credentialist citizenship, or stopped reassuring the population about its efforts to control flows, the negative sentiment towards the outgroup would be even greater. That is why the media emphasize government actions to control borders.

According to Van Dijk (2003), these are the definitive stereotypes held by the majority of those who feel threatened by the presence of ethnic groups that concur with semantic structures that reflect racist discourse, and which Echevarría and Villareal (1995) summarise as: 1) different appearance, culture and behaviour; 2) deviation from norms and values; 3) competition for scarce resources; 4) perceived threat.

As we can see, the perception of immigration is also closely related to social position; young people show a more moderate anti-immigration sentiment, as do people with a higher level of education or income. They do not see immigrants as a threat or in competition for resources, and they also understand that some news stories and speeches by politicians on immigration respond to specific agendas and are far from objective. Relational experience (direct or indirect) with immigrants also affects perception, since attitudes towards the outgroup are rooted in prejudice and stereotypes which are constructed and consolidated due to lack of intergroup contact. In Spain, the results show that although contact has increased, relations between natives and immigrants hardly exist, be they affective or occasional in nature. This is not due so much to the lack of common spaces as to the instrumentalization of the immigrant as a degrading agent. There is no shortage of news referring to problems of neighbourhood coexistence among groups or the deterioration of environments where immigrants reside. Social cognitions are acquired and deployed, and transform within situations and social interactions, and social structure contexts (Van Dijk, 2003).

To judge by the results, there is a definitive and clear correlation between the variables that define anti-immigrant sentiment and the news frames of the communications media. As in other national studies already mentioned, and international studies on the subject, (Dursun, 2005; d’Haenens & de Lange, 2001; Ter Wal, & al., 2005), the results show that the migratory phenomenon is viewed in negative terms. Furthermore, media representation through news frames, such as those linking immigrants to violence and/or delinquency, or illegal entry in «pateras» (makeshift boats), contributes to the development of prejudice through the legitimization of certain xenophobic and racist discourses. The error stems from the selection of the event within the paradigm and standardized parameters of what is deemed newsworthy, and impacts little or not at all on what is revealed. Such a journalistic strategy replaces balanced news reporting, and the progressive monopolization of this sector leads to content homogenization by prioritising commercial interests over journalists’ vocational sense of social responsibility.

Therefore, efforts must be made in increasingly multiethnic societies to strengthen a pluralistic view, and the communications media must modify their strategies, for example, by inserting other news frames that counterbalance the view of immigration as a perceived threat (identity or population), to reduce the rising trend of anti-immigrant sentiment that advances almost regardless of the real economic situation. Likewise, the educational system not only provides a space for intergroup interaction, as an important element in casting judgment on the outgroup, it must also impart values of equality and the acknowledgment of difference to counteract negative images disseminated by other institutions. To do nothing and allow the current situation to prevail is to tolerate a process that will lead to xenophobic acts against groups and individuals.

References

Allport, G.W. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. New York: Addison-Wesley.

Blalock, H.M. (1967). Toward a theory of minority-group relations. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Brader, T.; Valentino, N. & Suhay. E. (2004). Seeing Threats versus Feeling Threats: Group cues, Emotions, and Activating opposition to Immigration. Philadelphia: American Political Science Association.

Cachón, L. (2009). En la España inmigrante: entre la fragilidad de los inmigrantes y las políticas de integración. Papeles del CEIC, 45; 1-35.

Cea D'ancona, M.A. (2009). La compleja detección del racismo y la xenofobia a través de encuesta. Un paso adelante en su medición. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 125; 13-45.

Coenders, M. & Scheepers, P. (2008). Changes in Resistance to the Social Integration of Foreigners in Germany 1980-2000: Individual and Contextual Determinants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 34 (1); 1-26.

Dearing, J.W. & Rogers, E.M. (1996). Agenda Setting. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Díez Nicolás, J. (2005). Las dos caras de la inmigración. Madrid: OPI.

Dursun, O. (2005). News Coverage of the Enlargement of the European Union and Public Opinion: A Case Study of Agenda-Setting Effects in the United Kingdom. European Union Studies Association’s. Ninth Biennial International Conference. Austin, EEUU.

D´Haenens, L. & De Lange M. (2001). Framing of Asylum Seekers in Dutch Regional Newspapers. Media, Culture and Society, 23; 847-60.

Echevarría, A. & Villareal, M. (1995). Psicología social del racismo. In Echevarría, A. & al. (Eds.). Psicología social del prejuicio y el racismo. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Ramón Areces.

Escandell, X. & Ceobanu, M. (2009). When Contact with Immigrants matters Threat, Interethnic Attitudes and Foreinger Exclusionism in Spain´s Comunidades Autónomas. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 32 (1); 44-69.

Igartua, J.J. & Muñiz, C. (2004). Encuadres noticiosos e inmigración. Un análisis de contenido de la prensa y televisión españolas. Revista de Estudios de Comunicación, 16; 87-104.

Igartúa, J.J.; Humanes, M.L. & al. (2004). Tratamiento informativo de la inmigración en la prensa española y opinión pública. VII Congreso Latinoamericano de la Comunicación. La Plata (Argentina), 11-16 de octubre.

Igartua, J.J.; Muñiz, C. & Cheng, L. (2005). La inmigración en la prensa española. Aportaciones empíricas y metodológicas desde la teoría del encuadre noticioso. Migraciones, 17; 143-181.

Igartua, J.J.; Otero J.A. & al. (2007). Efectos cognitivos y afectivos de los encuadres noticiosos de la inmigración, en Igartua, J.J. & Muñiz, C. (Eds.). Medios de comunicación, Inmigración y Sociedad. Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca; 197-232.

Lorite, N. (2007). Tratamiento informativo de la inmigración en España 2007. Barcelona: Migracom.

Muñiz, C.; Igartu, J.J. & al. (2008). El tratamiento informativo de la inmigración en los medios españoles. Un estudio comparativo de la prensa y televisión. Perspectivas de la Comunicación, 1 (1); 97-112.

Pérez, M. & Desrues, T. (2005). Opinión de los españoles en materia de racismo y xenofobia. Madrid: Observatorio Español de Racismo y Xenofobia.

Quillian, L. (1995). Prejudice as a Response to Perceived Group Threat: Population Composition and Anti-immigrant and Racial Prejudice in Europe. American Sociological Review, 60 (4); 586-611.

Quillian, L. (1996). Group Threat and Regional Change in Attitudes toward African-americans. American Journal of Sociology, 102 (3); 816-860.

Scheufele, D. (2000). Agenda-setting, Priming and Framing Revisited: Another Look at Cognitive Effects of Political Communication. Mass Communication and Society, 3 (2-3); 297-316.

Schiefer, D.; Möllering, A. & al. (2010). Cultural Values and Outgroup Negativity: A Cross Cultural Analysis of Early and Late Adolescents. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40; 635-651.

Schlueter, E. & Scheepers, P. (2010). The Relationship between Outgroup Size and Anti-outgroup Attitudes: a Theorical Synthesis and Empirical Test Group Threat and Intergroup Contact Theory. Social Science Research, 39; 285-295.

Schneider, S.L. (2008). Anti-immigrant Attitudes in Europe: Outgroup Size and Perceived Ethnic Threat. European Sociological Review, 24 (1); 53-67.

Schwart, S.H. (2008). Culture Value Orientations: Nature and Implications of National Differences. Moscow: University Economic Press.

Semyonov, M.; Raijman, R. & Gorodzeisky, A. (2006). The Rise of Anti-foreigner Sentiment in European Societies 1988-2000. American Sociological Review, 71; 426-449

Semyonov, M.; Raijman, R. & Gorodzeisky, A. (2008). Foreigners Impact on European Societies: Public Views and Perceptions in a Cross-national Comparative Perspective. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 49 (1); 5-29.

Ter Wal, J.; D’Haenens, L. & Koeman, J. (2005). (Re)presentation of Ethnicity in EU and Dutch Domestic News: A quantitative Analysis. Media, Culture and Society, 27; 937-50.

Tood, E. (1996). El destino de los inmigrantes. Barcelona: Tusquets

Valkenburg, P.M.; Semetko, H.A. & de Vreese C.H. (1999). The Effects of News Frames on Reader’s thoughts and Recall. Communication Research, 26; 550-69.

Van Dijk, T.A. (2003). Dominación étnica y racismo discursivo en España y América Latina. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Worchel, S. (1998). Written in Blood. Ethnic Identity and the Struggle for Human Harmony. New York: Worth Publishers.

Zapata-Barrero, R. (2009). Policies and Public Opinion towards Immigrants: the Spanish Case. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 32 (7); 1101-1120.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Con la transformación de España desde hace unas décadas en país de inmigración, la sociedad ha experimentado un importante cambio configurando un espacio social caracterizado, cada vez más, por la diversidad cultural, étnica y religiosa. En este escenario novedoso es de gran interés indagar sobre la valoración que de dicha diversidad tiene la sociedad española. El objetivo de este artículo es doble, por un lado, conocer la opinión que tienen los españoles sobre la inmigración entre 1996 y 2007. Por otro, comprobar el papel que juegan los medios de comunicación en la configuración de ese sentir. Para el primer objetivo se ha construido el índice de sentimiento anti-inmigrante, a partir de los datos ofrecidos por la encuesta nacional sobre opiniones y actitudes ante la inmigración, administrada, anualmente, por ASEP. Para el segundo, se analizan, utilizando la teoría de la «Agenda Setting», las noticias publicadas por los periódicos «El País» y «El Mundo» sobre inmigración. Los resultados muestran que el sentimiento negativo hacia el exogrupo se va incrementado con el paso del tiempo. Las principales variables que explican esa tendencia son: el sentimiento de amenaza –poblacional e identitaria–, competencia por los recursos y decisiones políticas en el proceso de integración –regularización–. Del análisis de los medios resultan seis encuadres, los principales hacen referencia a la irregularidad del fenómeno, a la vinculación inmigración y delincuencia y a las políticas de integración social. Por tanto, se pone de manifiesto el papel que juegan los medios de comunicación a la hora de crear opinión.

1. Introducción

España se ha convertido en sólo unas décadas en tierra de inmigración. Según el Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) los extranjeros en España alcanzaban a mediados de los noventa la cifra de 542.314, ésta ascendía hasta a 1.370.657 a principios del presente milenio, y en la actualidad, según el último dato publicado en enero de 2011, se sitúa en 5.730.667. O lo que es igual, corresponde al mayor incremento de población extranjera de toda la Unión Europea.

La llegada de población desde todos los continentes, formando el mayor crisol cultural de la historia del país, no ha dejado indiferente a la población nacional. El Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS), en sus barómetros mensuales, pone de manifiesto que las actitudes de los españoles hacia los inmigrantes han cambiado sustancialmente en los últimos años. Frente a la postura mayoritaria en 1996 a favor de la inmigración, al juzgarla como necesaria y no excesiva, en la actualidad se aprecia una mayor xenofobia o rechazo hacia el inmigrante (Cea D’Ancona, 2009; Díez Nicolás, 2005; Pérez & Desrues, 2005), aunque no como resultado de un proceso lineal. Más concretamente, en el 2000 la inmigración era el cuarto mayor problema para los españoles tras el terrorismo de ETA, el paro y las dificultades de índole económica. En 2006 para el 38.3% de los españoles la inmigración era el inconveniente más importante del país, ascendiendo al segundo lugar, tras el paro. En el último barómetro de 2010 la inmigración vuelve a ser el cuarto problema, tras el paro, las dificultades de índole económica y los partidos políticos.

Ahora bien, la transformación de un fenómeno social, como es la inmigración, en un problema social responde a un proceso donde intervienen agentes de diversa índole, entre los que destacan los medios de comunicación. Más concretamente, Cachón (2009) apunta a éstos como los que evocan el problema y lo hacen público. Puesto que cualquier factor situacional que contribuye a generar imágenes de discriminación y exclusión social tiene mucho que ver con la acción informativa de los medios (Van Dijk, 2003). Desde la teoría «Agenda Setting» se indica que la percepción de los asuntos sociales está condicionada, en gran parte, por su contribución (Dearing & Rogers, 1996; Scheufele, 2000). El proceso de «framing» está relacionado con dos operaciones básicas: seleccionar y enfatizar expresiones e imágenes para conferir un punto de vista, una perspectiva o un ángulo determinado a una información. Por esto, Valkenburg, Semetko y de Vreese (1999:550) entienden el encuadre mediático como «una forma particular a través de la cual el periodista compone o construye una noticia para optimizar la accesibilidad de la audiencia».

Los estudios desarrollados desde esta perspectiva teórica demuestran que un mayor énfasis mediático sobre un determinado tema o asunto social tiende a provocar en la opinión pública una mayor preocupación sobre ese tema, como puede ser el caso de las migraciones (Brader, Valentino & Suhay, 2004; Igartua & Muñiz, 2005; Igartua, & al., 2007). De este modo, Igartua y colaboradores (2004) encuentran una correlación positiva y significativa entre el número de noticias publicadas por los diarios de información general y el porcentaje de encuestados que indicaba que la inmigración era una problema para el país. Asociación que pone de manifiesto que la cobertura informativa se puede convertir en un factor fundamental a la hora de considerar el fenómeno migratorio como un problema y, por extensión, en una fuente de prejuicios y estereotipos que derivan en racismo.

Por tanto, el objetivo de este artículo es doble, por un lado, conocer la evolución y las variables que definen las opiniones hacia el exogrupo, a través del índice de sentimiento anti-inmigrante. Y, por otro, conocer cómo los medios de comunicación españoles cubren este fenómeno, ya que entendemos que éstos constituyen el primer paso a la hora de cimentar dicho sentimiento.

Para este análisis longitudinal hemos elegido dos momentos diferentes. En el primero, 1997/98, España está inmersa en un periodo de crisis económica y donde la población inmigrante es reducida. En el segundo, 2006/2007, la tasa de inmigrantes es alta y se alcanza el punto álgido de la expansión económica; pero donde también se empieza a vislumbrar el proceso de estancamiento y posterior regresión.

2. Método y datos

Para el primer objetivo obtenemos los datos de la encuesta nacional realizada por la empresa de opinión Análisis Sociológicos, Económicos y Políticos (ASEP). Desde 1995 hasta 2007 realizaron encuestas, estadísticamente significativas y con los mismos ítems, sobre las actitudes de la población española, mayor de 18 años, hacia los extranjeros. La muestra está estratificada proporcionalmente atendiendo al número de inmigrantes asentados en las diferentes comunidades autónomas. Los datos se recogen de manera aleatoria. Para el bienio 1996/1997 la muestra agregada la componen 2.413 personas; en 2006/2007 los encuestados fueron 2.405. A su vez, la matriz ha sido completada con las estadísticas oficiales de población extranjera y tasa de paro.

Para medir la actitud de los españoles ante la inmigración se elige el índice de sentimiento anti-inmigrante (Semyonov & al., 2006), construido a partir de las siguientes cuatro cuestiones: «La inmigración provocará que España pierda su identidad» (De acuerdo=1); «Influencia de la inmigración en el paro» (Aumenta=1); «Influencia de la inmigración en los salarios de los españoles» (Disminuye=1); e «Influencia de la inmigración en la delincuencia» (Aumenta=1). El índice oscila entre 0 y 4, donde 4 significa máxima actitud anti-inmigrante.

No obstante, cabe señalar, tal y como lo hace Cea d´Ancona (2009), que la medición de la xenofobia a través de encuestas presenta algunas limitaciones que exceden a la propia técnica, fundamentalmente, por el sesgo de deseabilidad social, definido por el estigma que conlleva su admisión, donde se censura e incluso penaliza cualquier declaración o conducta contraria a los principios constitucionales de igualdad y no discriminación.

Con el propósito de conocer las variables que mejor predicen el sentimiento llevaremos a cabo un análisis de regresión teniendo en cuenta las siguientes dimensiones: amenaza, inseguridad y distancia social. Completadas con otras que hacen referencia a indicadores de política migratoria y derechos sociales (Cea d´Ancona, 2009). La amenaza se mide, por un lado, a partir del tamaño real de la población extranjera –tasa de extranjeros– y la percibida (Quillan, 1995, 1996; Scheneider, 2008; Schlueter & Scheepers, 2010; Semyonov, & al., 2008), damos el valor (1) a quienes contestaron que los inmigrados en España son demasiados. Y, por otro, la amenaza identitaria, visibilizada en la percepción de conflicto en las cuestiones de identidad, ensalzando lo étnico o lo cívico. Para ello, se toma la variable efectos que la inmigración tiene para la cultura española (Malos o muy malos=1); propio de una identidad étnica.

De la amenaza deriva la inseguridad, que se expresa a partir de dos elementos: uno, la material; cuantificada, por un lado, por la actitud ante que sólo deben admitirse a inmigrantes cuando no haya españoles para desarrollar esa actividad (De acuerdo=1). Y, por otro, por la tasa de paro. Dos, inseguridad política; referida a dos cuestiones relacionadas con la política migratoria y concesión de ciudadanía (Díez Nicolás, 2005): primera, «Bastante complicada es la situación económica de los españoles como para destinar dinero para ayudar a los inmigrantes» (De acuerdo=1) y, segunda, «Actitud más adecuada ante los inmigrantes irregulares» (regularizarlos=1).

La distancia social, entendida como falta de interacción con inmigrantes, se construye por las tres dimensiones utilizadas en el contacto intergrupal (Allport, 1954; Escandell & Ceobanu, 2009), a saber: intenso, si se tiene una relación estrecha y afectiva (No=1); ocasional, si ha tenido alguna vez una conversación larga (No=1); y en el lugar de trabajo, existe relación laboral con trabajadores extranjeros (No=1).

Por último, las variables de carácter individual poseen también una enorme importancia a la hora de predecir el sentimiento anti-inmigrante (Coenders & Scheepers, 2008): sexo (hombre=1), edad (en años), nivel educativo (universitarios=1), ingresos (cuartil más bajo=1), orientación política (derecha=1), actividad (desempleado=1) y estado civil (casado=1).

En cuanto al tratamiento informativo de la inmigración se han elegido dos periódicos nacionales: «El País» y «El Mundo». Se tomaron todas las noticias que hacían referencia a la inmigración en el periodo de producción informativa estándar de los bienios 1997/98 y 2006/2007, tal y como recomienda Lorite (2007); quedando fuera los periodos vacacionales. De igual modo, han quedado exentas del análisis aquellas noticias que, aunque hablan o hacen referencia al hecho migratorio, no figuran como protagonistas principales de la acción los inmigrantes. En suma, para este trabajo se han contabilizado un total de 217 noticias.

A través del tipo de noticia y con el análisis factorial (Igartua & al., 2005; Muñiz & al., 2008), se establecen los encuadres noticiosos. También, se codificó con carácter negativo aquellas noticias donde la descripción del suceso o sus consecuencias pueden ser juzgadas como no deseables para los inmigrantes; por ejemplo, actos delictivos. Las informaciones se codificaron neutras o ambiguas cuando no se apreciaban consecuencias negativas ni positivas para los inmigrantes y, finalmente, positivo si el suceso o sus consecuencias eran deseables, como regulaciones.

3. Resultados

Atendiendo a los objetivos que guían el texto, primero analizamos la intensidad y evolución del sentimiento anti-inmigrante, así como las variables que lo definen. Posteriormente, nos aproximaremos al encuadre y tratamiento que los medios de comunicación ofrecen de las noticias sobre inmigración.

Lo primero que resulta del estudio longitudinal es el incremento paulatino del sentimiento anti-inmigrante en España. Si en 1997 la media era de 1.4, en 2007 se sitúa en 2.1 (véase gráfico 1). O lo que es igual, se identifica, cada vez más, al extranjero como generador de desempleo, delincuencia, bajada de salarios y enemigo de la identidad cultural. Incluso, la evolución responde a tres momentos distintos dentro de la propia década analizada. En un primer momento 1997/99 el sentimiento se mantiene casi constante, alrededor del 1.4. Con la entrada del nuevo milenio, se produce un impulso llegando el rechazo hasta el 2.1. Por último, desde 2004 hasta 2007 vuelve a incrementarse hasta llegar al 2.4. Por tanto, en España, tal y como sostiene Blalock (1967), las actitudes hacia el exogrupo no experimentan un incremento lineal.

En un segundo paso del análisis, se han estimado, en función de las variables individuales y contextuales, dos modelos de regresión (véase tabla 1). En el modelo 1 examinamos el papel que juegan las variables de la amenaza e inseguridad y contacto intergrupal en la construcción del sentimiento anti-inmigrante. En el modelo 2 añadimos las variables individuales.

En el primero, bienio 1997/98, se observa que tanto las variables de la amenaza, como las de inseguridad son las que mejor explican el sentimiento. Más concretamente, y por este orden: la amenaza percibida, destinar dinero a las políticas de integración, efectos negativos sobre la cultura de origen y permitir la entrada de inmigrantes cuando no haya españoles para realizar las actividades, todas ellas con signo positivo, explican el 39,3% de la varianza del sentimiento anti-inmigrante. En otras palabras, cuando se tiene una mayor sensación de invasión, se destina más dinero a políticas de integración, se piensa que la inmigración tiene efectos negativos sobre la cultura y se opina que sólo deberían entrar inmigrantes cuando no se encuentren españoles para ocupar el puesto de trabajo, mayor es el sentimiento negativo. Con menor peso aparece la población real y, con signo negativo, regularizar a los inmigrantes. En las variables del contacto sólo aparece con significación estadística el contacto ocasional, de manera que cuantas más veces tengamos una conversación larga con un extranjero menor será la percepción negativa que se tendrá sobre el exogrupo.

En 2006/07 las variables amplían su peso a la hora de explicar el sentimiento. Destaca el rechazo a destinar dinero a la política de integración de los inmigrantes, seguido por la amenaza poblacional y cultural, así como aceptar inmigrantes cuando no haya españoles para el desempeño. Con signo negativo vuelve la regularización y, con menor incidencia, con respecto a la fecha anterior, la tasa de paro. En cuanto al contacto intergrupal, las relaciones intensas aparecen, por primera vez, con significación estadística, de modo que cuanto más intenso es el contacto se reduce la xenofobia.

En consecuencia, es más importante la amenaza percibida, creada por diferentes agentes e instituciones y la competencia económica y política a la hora de crear sentimientos hacia los extranjeros, que la población real o la tasa de paro, incluso cuando las tasas de inmigración son relativamente bajas, como ocurre en 1997/98.

En el segundo modelo, con las variables individuales, los datos correspondientes a la amenaza, inseguridad y contacto intergrupal se mantienen casi constantes. En 1997/98, por este orden, predicen el sentimiento negativo hacia el exogrupo: la edad, la orientación política, el nivel educativo –con signo negativo-, estado civil, sexo y desempleo. Dicho de otro modo, a más edad, tener ideología de derechas y bajo nivel educativo, estar casado, ser hombre y sufrir el desempleo repercute en presentar mayor sentimiento anti-inmigrante.

En 2006/07, hombre y desempleado son las variables sociodemográficas más importantes, a pesar de que es el momento que menor tasa de desempleo existe en el periodo analizado. También en esta fecha pierde el nivel de estudios e ingresos su capacidad de predicción.

Ahora bien, ¿cómo se construye ese sentimiento? Son múltiples y de diverso calado los elementos que ayudan a construir la visión de la alteridad. En nuestro interés por conocer el papel que juegan los medios de comunicación en la configuración de este proceso, tal y como muestra la tabla 2, encontramos que se produce un aumento importante en el número de noticias del primer al segundo bienio. Situación que responde a dos motivos principales: primero, al gran incremento del número de inmigrantes durante esa época y, dos, a las demandas de los inmigrantes y las actuaciones políticas en dicha materia; por ejemplo, en 2006 aún resonaban los ecos del proceso de regularización llevado a cabo el año anterior, sobre todo, por el supuesto «efecto llamada» que pudo ocasionar. En consecuencia, el fenómeno migratorio en una década pasó de ser una cuestión subsidiaria a ser otra de primer orden en la agenda política y social.

Cuando se ahonda más en el análisis se comprueba que las noticias publicadas, para ambas fechas, tienen un marcado carácter negativo. Si en el bienio 1996/97 el 65% de las noticias tenían un perfil negativo y sólo el 18% resaltaban los elementos positivos de la inmigración; en 2006/07 las noticias negativas ascendían al 69% y las positivas al 21%. De ahí que podamos encontrar titulares que corresponden a afirmaciones, sin matizar, de líderes políticos, religiosos, etc., como los siguientes: «Un centro islámico hace peligrar la convivencia en la Babel extremeña» (El Mundo, 17-08-2006); «Musulmanes piden suprimir las fiestas de Moros y Cristianos por no caber en la España democrática» (El Mundo, 05-10-2006); «El fundamentalismo islámico y la inmigración amenazan Europa» (El País, 10-10-2006); «Vivir aquí es morir a fuego lento» (El País, 28/10/2006).

No obstante, el aumento también de las noticias positivas responde a que las migraciones, con el paso del tiempo, han generado menor suspicacia a los informadores, especialmente en épocas de expansión económica, como fue el periodo de 1997 a 2007.

Con el análisis factorial resultaron seis encuadres noticiosos, a saber: 1) Flujos irregulares de inmigrantes (pateras, cayucos, camiones, etc.); 2) Inmigración y oportunidades sociales (mercado de trabajo, vivienda, servicios sociales, etc.); 3) Tramitación de documentos y regularización de inmigrantes; 4) Inmigración y delincuencia (actos delictivos, mafias, etc.); 5) Actos racistas, xenófobos y discriminación; y 6) Políticas sobre la integración social (administración central, regional y local). A lo que sumamos que, salvo excepciones, las noticias solo se enmarcan en un encuadre.

El «frame» que predomina sobre el resto es el de flujos irregulares de inmigrantes; seguido por tratamiento de documentos y regulación en el bienio 2006/07 e inmigración y actos delictivos en 1997/98; y, en tercer lugar, y para ambos periodos, aparecen políticas de integración social. Sin embargo, los encuadres menos numerosos son actos racistas, xenofobia y regularización, por un lado; e inmigración y oportunidades sociales; por otro. Por tanto, los encuadres periodísticos poco dicen de cuestiones positivas que la inmigración deja en país de destino como, por ejemplo, las aportaciones económicas al Estado o su importancia en el proceso de desarrollo. Tampoco se incide en las experiencias de discriminación o racismo de las que son objeto los inmigrantes de forma casi diaria, tal y como recogen los informes de SOS racismo. Si bien es cierto que para el bienio 2006/2007, el encuadre de las oportunidades sociales se ha incrementado de manera importante, ya que coincide con el punto álgido de la expansión económica.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

Este artículo analiza la imagen que los inmigrantes extranjeros tienen en España, ya que las opiniones y actitudes sobre los inmigrantes representan nuevas formas de racismo y xenofobia. Para ello se han elegido varios momentos: uno, en situación de crisis económica y reducidas tasas de inmigración; dos, en el punto álgido de la expansión económica y consolidación de las migraciones.

Lo primero que los datos ponen de relieve es que la hostilidad hacia los inmigrantes se ha ido incrementando con el paso del tiempo: si en 1997/98 el índice tenía como media 1.4, en 2006/07 llega a 2.4. Ahora bien, esta tendencia no se explica únicamente por el incremento de la población real en poco tiempo, ésta sólo es el desencadenante al principio de la llegada de los flujos, puesto que las variables que predicen el sentimiento en 1997/98 no distan de las aparecidas una década después; por tanto, el sentimiento responde a prácticas discursivas cotidianas y/o institucionalizadas, dictadas principalmente por los medios de comunicación.

La construcción de la inmigración a través de su número (invasión) no es «per se», sino que responde a una construcción simbólica producto de alocuciones provenientes de diversos actores y escenarios sociales, en los que destacan, especialmente, los medios de comunicación. Basta recordar que el primer encuadre periodístico para ambas fechas hacía referencia a los flujos de entrada de irregulares. De modo que para referirse a su cifra, normalmente, se hace alusión a metáforas que poco tienen que ver con la cuantificación de los flujos: oleada, avalancha, invasión, etc., calificaciones que promueven la idea de que son demasiados y que provocan hostilidad y miedo. Así lo expresaba el dominical de «El País» (08-08-1998) cuando sostenía «Inmigración: crece la marea». De esta forma el inmigrante se traduce en miedo por la hiperextranjerización. En otras palabras, la inmigración es vista como un problema antes que como un fenómeno propio de la sociedad internacional, que, a lo sumo, acarrea grandes retos.

Pero la amenaza trasciende lo numérico para consolidarse también en lo identitario (Schiefer & al., 2010; Schwart, 2008). Tal y como nos recuerda Worchel (1998) cualquier tipo de identidad grupal sirve de base para el conflicto, especialmente cuando se adscribe un contenido étnico en base a estereotipos y ciertos grupos pasan a conceptualizarse como culturalmente incompatibles. Se distinguen por la exageración de las diferencias culturales, a través del prejuicio sutil. Se percibe a la cultura como un rasgo heredado del que nadie puede desprenderse, o lo que es igual, «existe una concepción genealógica y, por tanto, racial de la cultura y su transmisión» (Todd, 1996: 343). Se enfrentan al rechazo abierto o a una «integración» subordinada, puesto que las creencias de los otros son, casi siempre, vistas como elementos de fundamentalismo, lo que equivale a focos de conflicto o de choque, sobre todo, si se trata de musulmanes, puesto que a éstos se les toma como el arquetipo. Por eso, la mejor respuesta a esta situación, según los autóctonos, es la asimilación cultural y la negación del pleno derecho de la ciudadanía; inclusive por aquellos que no se consideran racistas.

De ahí, que los españoles sostienen que la llegada continua de población extranjera provoca efectos negativos en la cultura nacional y no debe destinarse dinero para su integración, ni deben ser regularizados. Más aún, en los discursos de algunos políticos, que recogen los medios de comunicación, prevalecen estructuras semánticas que resaltan la diferencia de apariencia, de cultura y conducta; o la desviación de las normas y de los valores; que toman forma en lemas del tipo «defiende tu identidad», «defiende tus derechos». Todo esto alentado con una conciencia nacionalista basada especialmente en lo étnico. Se exige para otros lo que incluso no tiene ni el propio nacional. La identidad española se ha configurado en oposición al otro, y definida a partir de dimensiones de naturaleza abstracta y simbólica, más que de cualidad.

El sentimiento de amenaza se ve complementado por el de competencia en los recursos limitados como el empleo, vivienda, sanidad, etc., lo que lleva también a magnificar la presencia de inmigrantes. Situación que responde a encuadres noticiosos; esto es, la inmigración y las oportunidades sociales, no tanto en su faceta positiva (contribución al desarrollo económico), sino como la negativa (saturación de los recursos). De ahí que la mayoría de los españoles opinen que sólo deben aceptarse a extranjeros cuando no se encuentren españoles para hacer su trabajo. Atendiendo a lo anterior la inseguridad económica se verá acentuada en épocas de crisis puesto que, supuestamente, reduce las posibilidades en el mercado laboral y desciende la calidad de los empleos. No obstante, en nuestro caso hemos comprobado que esta situación es secundaria a la hora de manifestar el sentimiento negativo hacia el exogrupo, puesto que en 1997 España estaba sometida a una crisis económica que elevó la tasa de paro a cifras históricas y con una tasa de extranjería de las más bajas de la Europa de los quince; sin embargo, la xenofobia era más reducida que en los otros dos periodos posteriores, especialmente en el bienio 2006/07 que se alcanzaron las mayores dosis de crecimiento económico y menores tasas de desempleo de la historia; pero, por el contrario, la tasa de inmigración significaba más del 10% de la población. Esta situación también se ratifica, primero, cuando el paro en el primer periodo no tiene significación estadística a la hora de predecir la variabilidad del sentimiento anti-inmigrante y sí en las otras dos fechas. Segundo, estar desempleado tiene mayor peso a la hora de predecir en las etapas de expansión económica, pero de mayor tasa de inmigración.

Realidad que responde, por un lado, a que en un principio el mercado laboral que ocupan los inmigrantes (agricultura y construcción, principalmente) era complementario al desempeñado por los autóctonos. Incluso la discriminación laboral sobre los primeros permite a estos últimos acceder a empleos para los cuales inicialmente no tienen la cualificación. Sin embargo, con el paso del tiempo, los inmigrantes han ocupado otros nichos laborales (sector servicios) que sí han sido competencia con la población nacional, especialmente con aquellos nacionales que presentan mayores desventajas en capital social y humano. Por otro, al aumento de la inmigración como realidad noticiable, ya que en una década el número de noticias sobre inmigración se ha duplicado, sobresaliendo las de carácter negativo. Más aún, la población nacional percibe la competencia también en los beneficios del Estado de Bienestar –vivienda, educación o sanidad–; por eso, de manera minoritaria destinarían dinero para el proceso de integración de los inmigrantes o los regularizarían. Es lo que Zapata (2009) ha llamado «gobernance hypothesis», de manera que si el gobierno afrontara la integración de los inmigrantes de forma inclusiva ofreciendo una ciudadanía cívica, en vez de credencialista, o dejara de transmitir a la población los esfuerzos que se realizan en el control de los flujos, el sentimiento negativo hacia el exogrupo sería aún mayor. Por eso, los medios enfatizan las acciones gubernamentales de control fronterizo.

En definitiva, éstos son, de acuerdo con Van Dijk (2003), los estereotipos tópicos de la mayoría de los miembros que se sienten amenazados por la presencia de grupos étnicos. Los cuales coinciden con las estructuras semánticas que reflejan el discurso racista y que Echevarría y Villareal (1995) resumen en cuatro: 1) Diferencia de apariencia, de cultura y conducta; 2) Desviación de las normas y de los valores; 3) Competición por recursos escasos; 4) Amenaza percibida.

La percepción de la inmigración, como vimos, también está en estrecha relación, por un lado, con la posición de la persona en la estructura social; puesto que los jóvenes presentan un sentimiento anti-inmigrante más moderado, al igual que ocurre con un mayor nivel de estudios o ingresos económicos altos. Ya que los individuos no ven a los inmigrados como una amenaza y competencia por los recursos, además de entender que, en ciertas ocasiones, tanto las manifestaciones periodísticas como políticas pueden responder a intereses creados, que distan de la objetividad del hecho. Por otro, con la experiencia relacional (directa o indirecta) con inmigrantes, ya que las actitudes hacia el exogrupo se fundamentan en prejuicios y estereotipos que se construyen y consolidan por la falta de contacto intergrupal. Para España los resultados han mostrado que, aunque existe un incremento, las relaciones son reducidas, tanto en lo afectivo, como en el contacto ocasional. Esta ausencia no se debe tanto a la falta de espacios comunes, sino que es fruto de la instrumentalización del inmigrante como agente que degrada. No faltan noticias que hacen referencia a los problemas de convivencia vecinal entre los grupos o el deterioro que sufren los entornos donde se insertan los inmigrados. Las cogniciones sociales se adquieren, se utilizan y se cambian en el transcurso de situaciones e interacciones sociales y dentro de un contexto de estructuras sociales (Van Dijk, 2003).

En definitiva, a tenor de los resultados, existe una correlación clara entre las variables que definen el sentimiento anti-inmigrante y los encuadres noticiosos que ofrecen los medios de comunicación, puesto que éstos, al igual que ocurre en otras investigaciones nacionales ya citadas, e internacionales (Dursun, 2005; d'Haenens & de Lange, 2001; Ter Wal & al., 2005) muestran un claro carácter negativo del fenómeno migratorio. Sumado a que, en general, la representación mediática, a través de sus encuadres noticiosos, como el que les vincula a la violencia y/o delincuencia, o entrada irregular en pateras, juega un papel especial en el desarrollo de las actitudes prejuiciosas, a través de la legitimación de determinados discursos xenófobos y racistas. El error radica, pues, en que la selección del acontecimiento se hace bajo el paradigma y los parámetros estandarizados de lo noticiable y se incide poco o nada sobre lo descubierto. Estrategia informativa que supera el pluralismo informativo, ya que la progresiva monopolización de este sector conduce a la homogeneización de contenidos al priorizar los aspectos comerciales sobre la responsabilidad social atribuida al periodismo.

Por tanto, en sociedades cada vez más multiétnicas se deben hacer esfuerzos para potenciar una visión pluralista, a sabiendas que los medios de comunicación deben modificar sus estrategias, como por ejemplo, añadiendo nuevos encuadres noticiosos que superen la visión de la inmigración como amenaza percibida –identitaria y poblacional–, para reducir ese sentimiento anti-inmigrante, cuya tendencia es a incrementarse, casi con independencia de la situación económica real. De igual modo, el sistema educativo, no sólo como espacio de interacción intergrupal, elemento importante a la hora de emitir un juicio sobre el exogrupo, debe instruir en valores de igualdad y reconocimiento de la diferencia, que contrarreste las imágenes vertidas desde otras instituciones. En caso contrario, tal y como ha ocurrido hasta la actualidad, se irán sucediendo actos en xenófobos hacia colectivos o individuos.

Referencias

Allport, G.W. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. New York: Addison-Wesley.

Blalock, H.M. (1967). Toward a theory of minority-group relations. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Brader, T.; Valentino, N. & Suhay. E. (2004). Seeing Threats versus Feeling Threats: Group cues, Emotions, and Activating opposition to Immigration. Philadelphia: American Political Science Association.

Cachón, L. (2009). En la España inmigrante: entre la fragilidad de los inmigrantes y las políticas de integración. Papeles del CEIC, 45; 1-35.

Cea D'ancona, M.A. (2009). La compleja detección del racismo y la xenofobia a través de encuesta. Un paso adelante en su medición. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 125; 13-45.

Coenders, M. & Scheepers, P. (2008). Changes in Resistance to the Social Integration of Foreigners in Germany 1980-2000: Individual and Contextual Determinants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 34 (1); 1-26.

Dearing, J.W. & Rogers, E.M. (1996). Agenda Setting. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Díez Nicolás, J. (2005). Las dos caras de la inmigración. Madrid: OPI.

Dursun, O. (2005). News Coverage of the Enlargement of the European Union and Public Opinion: A Case Study of Agenda-Setting Effects in the United Kingdom. European Union Studies Association’s. Ninth Biennial International Conference. Austin, EEUU.

D´Haenens, L. & De Lange M. (2001). Framing of Asylum Seekers in Dutch Regional Newspapers. Media, Culture and Society, 23; 847-60.

Echevarría, A. & Villareal, M. (1995). Psicología social del racismo. In Echevarría, A. & al. (Eds.). Psicología social del prejuicio y el racismo. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Ramón Areces.

Escandell, X. & Ceobanu, M. (2009). When Contact with Immigrants matters Threat, Interethnic Attitudes and Foreinger Exclusionism in Spain´s Comunidades Autónomas. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 32 (1); 44-69.

Igartua, J.J. & Muñiz, C. (2004). Encuadres noticiosos e inmigración. Un análisis de contenido de la prensa y televisión españolas. Revista de Estudios de Comunicación, 16; 87-104.

Igartúa, J.J.; Humanes, M.L. & al. (2004). Tratamiento informativo de la inmigración en la prensa española y opinión pública. VII Congreso Latinoamericano de la Comunicación. La Plata (Argentina), 11-16 de octubre.

Igartua, J.J.; Muñiz, C. & Cheng, L. (2005). La inmigración en la prensa española. Aportaciones empíricas y metodológicas desde la teoría del encuadre noticioso. Migraciones, 17; 143-181.

Igartua, J.J.; Otero J.A. & al. (2007). Efectos cognitivos y afectivos de los encuadres noticiosos de la inmigración, en Igartua, J.J. & Muñiz, C. (Eds.). Medios de comunicación, Inmigración y Sociedad. Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca; 197-232.

Lorite, N. (2007). Tratamiento informativo de la inmigración en España 2007. Barcelona: Migracom.

Muñiz, C.; Igartu, J.J. & al. (2008). El tratamiento informativo de la inmigración en los medios españoles. Un estudio comparativo de la prensa y televisión. Perspectivas de la Comunicación, 1 (1); 97-112.

Pérez, M. & Desrues, T. (2005). Opinión de los españoles en materia de racismo y xenofobia. Madrid: Observatorio Español de Racismo y Xenofobia.

Quillian, L. (1995). Prejudice as a Response to Perceived Group Threat: Population Composition and Anti-immigrant and Racial Prejudice in Europe. American Sociological Review, 60 (4); 586-611.

Quillian, L. (1996). Group Threat and Regional Change in Attitudes toward African-americans. American Journal of Sociology, 102 (3); 816-860.

Scheufele, D. (2000). Agenda-setting, Priming and Framing Revisited: Another Look at Cognitive Effects of Political Communication. Mass Communication and Society, 3 (2-3); 297-316.

Schiefer, D.; Möllering, A. & al. (2010). Cultural Values and Outgroup Negativity: A Cross Cultural Analysis of Early and Late Adolescents. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40; 635-651.

Schlueter, E. & Scheepers, P. (2010). The Relationship between Outgroup Size and Anti-outgroup Attitudes: a Theorical Synthesis and Empirical Test Group Threat and Intergroup Contact Theory. Social Science Research, 39; 285-295.

Schneider, S.L. (2008). Anti-immigrant Attitudes in Europe: Outgroup Size and Perceived Ethnic Threat. European Sociological Review, 24 (1); 53-67.

Schwart, S.H. (2008). Culture Value Orientations: Nature and Implications of National Differences. Moscow: University Economic Press.

Semyonov, M.; Raijman, R. & Gorodzeisky, A. (2006). The Rise of Anti-foreigner Sentiment in European Societies 1988-2000. American Sociological Review, 71; 426-449

Semyonov, M.; Raijman, R. & Gorodzeisky, A. (2008). Foreigners Impact on European Societies: Public Views and Perceptions in a Cross-national Comparative Perspective. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 49 (1); 5-29.

Ter Wal, J.; D’Haenens, L. & Koeman, J. (2005). (Re)presentation of Ethnicity in EU and Dutch Domestic News: A quantitative Analysis. Media, Culture and Society, 27; 937-50.

Tood, E. (1996). El destino de los inmigrantes. Barcelona: Tusquets

Valkenburg, P.M.; Semetko, H.A. & de Vreese C.H. (1999). The Effects of News Frames on Reader’s thoughts and Recall. Communication Research, 26; 550-69.

Van Dijk, T.A. (2003). Dominación étnica y racismo discursivo en España y América Latina. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Worchel, S. (1998). Written in Blood. Ethnic Identity and the Struggle for Human Harmony. New York: Worth Publishers.

Zapata-Barrero, R. (2009). Policies and Public Opinion towards Immigrants: the Spanish Case. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 32 (7); 1101-1120.

Document information

Published on 30/09/11

Accepted on 30/09/11

Submitted on 30/09/11

Volume 19, Issue 2, 2011

DOI: 10.3916/C37-2011-03-06

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?