Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

News consumption is undergoing great changes due to the advance of digitisation. In this context, ascertaining the changes in readers’ consumption habits is essential for measuring the scope and effects of digital convergence and the outlook for the future. This article aims to analyse this transformation in the specific case of young people’s relationship with news reporting. The methodology is based on a quantitative survey of people aged between 16 and 30 (N=549) in order to examine their consumer habits and perceptions. The results show the emergence of social networks as a news medium and the decline of traditional media, and newspapers in particular. However, we observed a high level of interest in news stories and their positive valuation in civic terms on the part of young people. These data also reveal the obvious appeal of cost-free content. Finally, the results highlight the gender gap with men as the greater news consumers, and the impact of age, with news consumption increasing as young people mature. The conclusions of this research suggest that profound changes are emerging in news consumption patterns and the concept of news among young people.

1. Introduction

Digitisation has brought changes to the communicative system, with content production, work routines, media and distribution strategies and business models all undergoing important alterations. Public consumption patterns are also transforming and substantially modifying the system’s traditional dynamics. In this context, ascertaining the changes in readers’ consumption habits is essential for measuring the scope and effects of digital convergence and the outlook for the future, and to that end this article focuses on the analysis of information consumption in a specific age group: young people. They are pioneers in assimilating technological innovations related to digitisation, and for this they are known as digital natives (Prensky, 2001; Palfrey & Gasser, 2008) or members of the interactive generation (Bringué & Sádaba, 2009). Their condition as early users (Livingstone & Bovill, 1999) makes them a priviliged case study for exploring the changes that have resulted from the impact of the digital era.

In order to study news consumption in the convergence frame, this article begins with an examination of newspapers which later extends to general information, regardless of format. There are different reasons that justify this choice: newspapers have traditionally been considered the main referent source of information (Corroy, 2008). Moreover, they have been the subject of most investigations focused on the study of the relationship between young people and news (Qayyum & al., 2010), and are undergoing a process of redefinition caused by the current financial crisis (Casero-Ripollés, 2010). However, this article is not just confined to newspapers, as convergence imposes the predominance of interconnections and interdependences within the media scenario.

The aims of this investigation are:

1) To ascertain young people’s news consumption habits, particularly of newspaper, in the digital era.

2) To discover the attitudes and perceptions of young people towards journalistic information.

The hypotheses of the investigation connected to the above aims are:

• H1. Young people’s news consumption goes beyond newspapers, which are read less and less, and encompass a wide variety of media, especially online media.

• H2. Young people show great interest in information, and attribute positive values to it.

2. Literature review

Scientific investigation of young people’s news consumption habits has focused mainly on the analysis of newspapers. These studies have confirmed a consistent decline in readership among this age group, a tendency that began in the mid-Nineties (Lauf, 2001) and which affects most European countries (Brites, 2010; Lipani, 2008; Raeymaeckers, 2004) including Spain. The percentage of young people between 18 and 25 who consume print media is 25.7 (AEDE, 2010). Other investigations also confirm this rift between young people and newspapers in Spain (Navarro, 2003; Arroyo, 2006; Túñez, 2009; Parratt, 2010).

There are many reasons that explain the decline in young people’s newspaper consumption: lack of time, preference for other media, and little interest in the content (Huang, 2009; Bernal, 2009; Costera, 2007; Raeymaeckers, 2002). The near irrelevance of news in their daily lives and the lack of a connection to their personal experiences and interests are key factors (Patterson, 2007; Vanderbosch, Dhoets & Van der Bulck, 2009; Qayyum et al., 2010). Young people not only fail to see themselves reflected in newspapers or conventional media (Domingo, 2005), but feel that they are marginal to their agenda setting. In this sense, the invisibility of young people in the news has been verified (Figueras & Mauri, 2010; Kotilainen, 2009) and the negativity that frequently attaches to them has also been confirmed (Túñez, 2009; Faucher, 2009; Bernier, 2011). All this is matched by the transformation arising from the digital convergence (Islas, 2009) that leads to a multi-screen society (Pérez-Tornero, 2008) which in turn also has an effect. The emergence of windows and news providers promoted by the Internet generate an overabundance of news and strong competition for readers’ attention, which also partly explains this phenomenon of decline. Scientific literature also points to parental influence as a significant impact on young people’s press consumption (Qayyum & al., 2010; Huang, 2009; Costera, 2007; Raeymaeckers, 2004; 2002).

Young people’s news consumption is conditioned by two key factors: the age effect, as people get older they consume more and show greater interest in news (Qayyum et al., 2010; Huang, 2009; Lipani, 2008); the second factor is related to genre. Some authors detect a gap that sees men’s consumption become more intense than women’s (Brites, 2010; Raeymaeckers, 2004; Navarro, 2003; Lauf, 2001).

The distancing between young people and newspapers has three consequences. Firstly, the decline in young newspaper readers means the loss of an important potential market, and therefore, a fall in circulation and profits (Arnould, 2004). Secondly, the ageing of newspaper consumers does not guarantee a generational shift in readers (Lauf, 2001). Finally, newspapers have traditionally been considered the primary access point to public affairs (Brites, 2010), and also a socializing agent of politics for young people (Romer, Jamieson & Pasek, 2009). In this sense, the lack of interest in the press could diminish young people’s civic consciousness.

3. Methodology

The methodological design of this investigation is based on a quantitative survey. This technique aims to obtain data about objective aspects (frequencies) and subjective aspects (opinions and attitudes) based on the information from individual interviews. The questionnaire is formed of three types of close-ended questions: dichotomous choice, multiple choice and open-ended questions, using a set of values from 0 to 10. The study combines single-answer with multiple choice questions.

The field survey was carried out from January to April 2011. The procedure used was the face-to-face interview method. Subsequently, the data were treated with the statistical program SPSS. Age and genre have been used as dependent variables while consumption and information perceptions are taken to be independent variables. The former include the frequency of reading newspapers, the way they access news, the number of media used to get informed, and payment predisposition. The latter focus on interest in news, and the civic values attributed to it. The study population is made up of 16 to 30-year-olds living in Catalonia (Spain), a segment which numbers 1,.284,005 individuals according to Idescat data from 2009. The sample is formed of 549 surveys randomly selected. The genre distribution of the sample is 45.35% men and 54.65% women.

4. Results

4.1. Frequency of newspaper reading

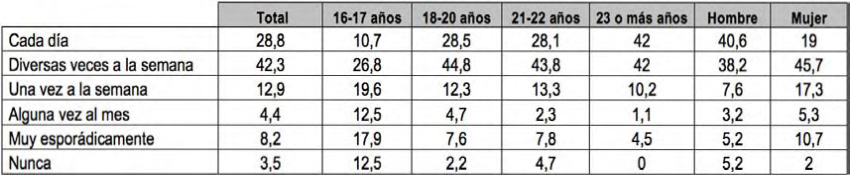

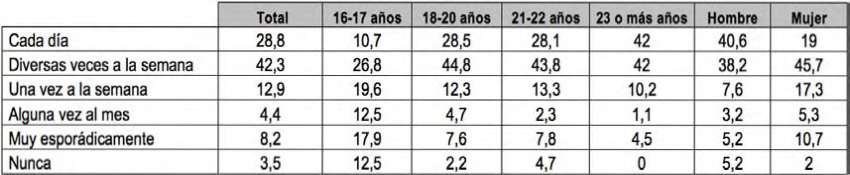

Young people who state that they read the press everyday account for 28.8% of the total (Table 1), which signifies reduced newspaper consumption among this age group.

The results reinforce the importance of the age effect on newspaper consumption; as readers get older, they mature and their interest in the press rises, hence the increase by 31.3 points between 16-17 year olds and those 23 or older (Table 1). These data demonstrate that as young people get older they acquire a greater need to be informed and a stronger interest in news, and at the same time their cognitive capacity to consume news grows (Huang, 2009). Two factors explain this: young people identify newspapers with the adult world (Raeymaeckers, 2004); young people have a utilitarian view of press – when the topics and content affect them directly they will read them, if not, they will ignore them as they their content and format do not fit their needs and expectations (Vanderbosch, Dhoets & Van der Bulck, 2009). In this sense, most young people associate newspaper consumption to professional activity and their incorporation into the labor market (Lipani, 2008).

The genre variable corroborates that young men read newspapers more than women. The survey shows that 40.6% of men read the press every day, while women register 19% (Table 1), revealing a clear genre gap in newspaper consumption.

4.2. Accessing media

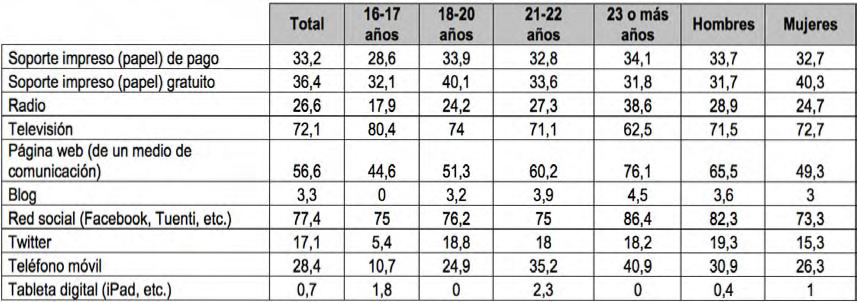

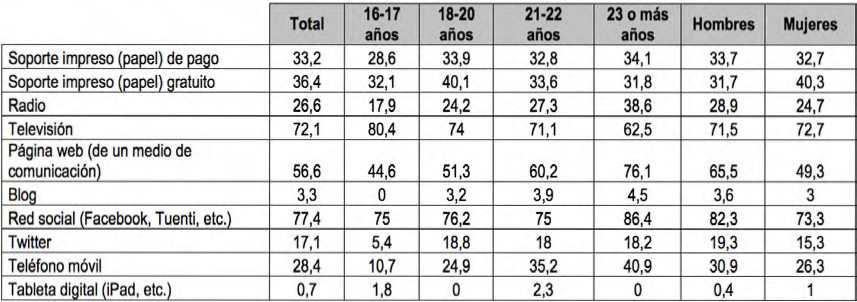

Today’s overabundance of information is due to the fact that news is not only provided by newspapers. Young people now have a wide range of media to choose from to get information and the results indicate that they indeed use several platforms to read the news. The use of television (watched by 72.1% of those polled) is significant but secondary to the social networks as a media for news consumption among young people (Table 2). Websites such as Facebook or Tuenti are now the leading information outlets for young people (77.4%), which is especially relevant for two reasons.

Firstly because it verifies that young people’s information consumption is increasingly online (Parratt, 2010), specifically via social networks. This predominance of social networks in young people’s accessing of news is one of the main contributions of this investigation. This feature also points to a shift in the use of social networks among young people. Until now several studies (Livingstone, 2008; Campos Freire, 2008; Boyd &Ellison, 2008; Carlsson, 2011) have highlighted the preeminently communicative function of social networks as young people use them to get in touch and interact with friends, as well as being a channel for self-expression. These new data show that social networks are now also used as means to read the news.

This change also emphasizes that young people increasingly turn to mass media websites to access news (56.6%), compared to paid-for newspapers (33.2%) and the cost-free press (36.4%). The mobile phone at 28.4%, is yet to consolidate as a window for news consumption among young people (Table 2).

The genre variable also reveals differences in preferences for news media among young people. Men score higher when selecting platforms and devices, except for television, digital tablets and the cost-free press where women score higher (Table 2). Men predominate in the use of social neteworks and mass media websites for news gathering.

The age variable confirms thatthe use of all media for news consumption grows as young people mature. Use of paid-for newspapers, radio, blogs, Twitter, social networks, mobile telephone and mass media websites increases as a result (Table 2). By contast,, watching television for news decreases as people get older, confirming the decline in prominence of this audiovisual medium among the young due to the emergence of new media in recent years (García Matilla & Molina Cañabate, 2008; López Vidales, González Aldea & Medina de la Viña, 2011).

4.3. Diversity

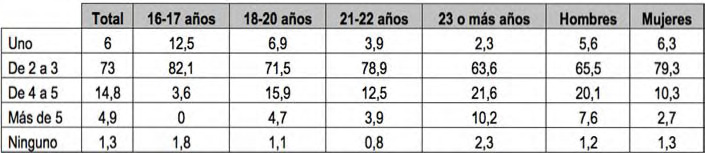

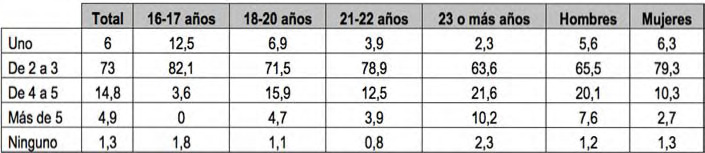

The results of our poll reveal that young people use a fairly wide range of mass media to get information, with 73% stating that they frequently use two to three different media to access news (Table 3). These data coincide with the study by Brites (2010: 185) who detected that young Portuguese aged 15 to 17 used an average of three different news sources. So, we can assume that young people’s news consumption is not restricted to a single medium, since this habit represents only 6% of the total (Table 3). This tendency, although not very high as only 4.9% consult more than five different media, shows that there is no longer a cognitive dependence on a single news source.

The reasons behind this remarkably diverse competence among young people to seek out news are numerous: Internet makes access to information easy, the increase in information on offer by the news media system and its sheer diversity. This diversity of news-providing media directly affects the forming of public opinion and its very richness, which is explained by the wide variety of points of view on any event and the elements that enable the reader to form an opinion (Kotilainen, 2009). In the same way, the range of media used by young people to access news is related to drastic changes in the way they process information (Rubio, 2010). The habit of channel-surfing acquired from TV watching is applied to news consumption in order to get a general impression of current affairs (Costera, 2007). That means an alteration in the traditional order of reading the news, from a linear, progressive reading to a non-sequential, diagonal, interrupted and hypertext reading (Domínguez Sánchez & Sádaba Rodríguez, 2005). The fact that young people use different news sources is connected to the transformation in their information consumption habits (Qayyum & al., 2010).

Age again turns out to be a decisive factor with regard to the plurality of news sources used by young people. The highest proportion of young people who use just one media outlet to check the news date is the 16 and 17 year old age group (Table 3). Moreover, none in this group uses five or more platforms for information consumption, the total opposite to the group of 23 year olds or older. Men are more diverse in the use of media than women (Table 3).

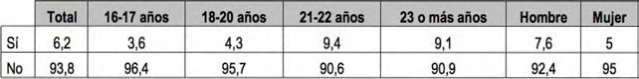

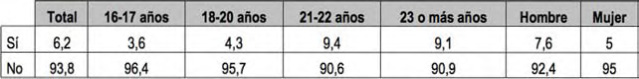

4.4. The consolidation of cost-free content

The results reveal that almost all young people are reluctant to pay to access information on the Internet. A total of 93.8% opposed paying for news with their own money (Table 4), demonstrating that the idea of cost-free content consumed online is deeply ingrained in young people. Only 6.2% said they would pay for news. This resistance to paying for information is also common in the rest of the population. Different studies register between 10-20% the number of people willing to pay for news (WAN, 2010; PEJ, 2010).

Although the refusal to pay diminishes with age, the percentage of 23 year olds or older willing to pay for news online is still small, representing only 9.1% (Table 4). Regarding the genre variable, the number of men in favor of paying is slightly higher than that of women, 7.6% against 5% (Table 4).

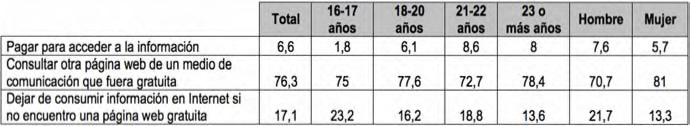

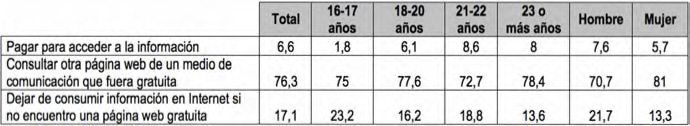

The deep-rooted support for cost-free content is demonstrated by the 76.3% of young people who say they would switch to another free access medium if their favorite web site charged for news (Table 5). In fact, cost-free access has become a powerful factor conditioning young people’s consumption of information on the Internet, with 17.1% of the sample stating that they would stop consuming news altogether if they could not find a free news outlet online (Table 5).

4.5. Interest in information

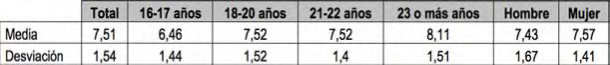

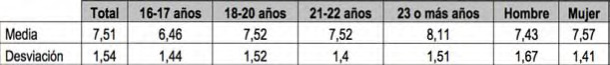

Finding out the attitudes and perceptions of young people towards news is essential for determining their information consumption. Young people’s interest in news registers an average of 7.51, on a scale of 0 to 10 in our survey (Table 6). Therefore, we can deduce that the low level of news consumption among the young, particularly newspapers, does not reflect apathy towards current affairs. On the contrary, young people have a considerable appetite for news and low consumption has nothing to do with indifference, rather dissatisfaction at the way information is presented, especially in the conventional media (Costera, 2007; Túñez, 2009; Huang, 2009; Raeymaeckers, 2002). This partly explains why young people tend to use other media, such as social networks, to get information, and have largely abandoned the print media (Lipani, 2008). Newspapers have not adapted to the interests and needs of their younger readers and are no longer considered a primary source of information by young people (Corroy, 2008).

The age effect is again evident as interest in news among young people rises remarkably as they enter adulthood. The genre variable is a paradox for as the previous data (frequency of reading, number of media used or willingness to pay) point out, men consume more information than women yet women declare a greater interest in news than men. The difference is small, 7.57 against 7.43 (Table 6), but noteworthy, and something similar occurs with regard to the civic importance attributed to news (Table 7).

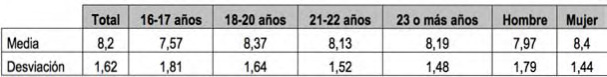

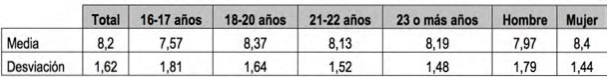

Young people also place a high civic value on information. On a scale of 0 to 10, young people give an average 8.2 to the fact that being well-informed enables you to participate in politics and be a good citizen (Table 7).Young people acknowledge that the availability of news is important for democracy and information enables and guarantees public debate and the development of a civic consciousness. Being well-informed is to be a fully active and responsible citizen, and news plays an important role in the civic and political socialization of young people (Romer, Jamieson & Pasek, 2009); young people have a positive concept of news, and although they are turning their backs on conventional media, they continue to value information.

5. Discussion and conclusions

The results allow us to verify the two hypotheses presented at the beginning of this article. The data demonstrate that young people’s news consumption is oriented towards new media, especially social networks, while newspaper readership among young people is in decline (H1). As a consequence, newspapers are no longer the primary source of information in the digital context (Lipani, 2008), which does not mean that the appetite for news among young people has diminished, quite the contrary, interest in information is strong and news consumption scores highly as a civic value (H2).

The data also reveal the diversity of news sources consulted to get information. News consumption is now a multiple media habit; each medium has a different level of prominence with news content subject to the effects of multiplatform distribution and the synchronic consumption habits of a younger generation able to perform various media activities simultaneously thanks to their multitasking skills (Micó, 2012; Van Dijk, 2006).

The data also reveal the deep-rooted habit of cost-free news access among the young. This is a serious problem for the paid-for media, and newspapers in particular, as it seriously affects the business model (Casero-Ripollés, 2010).

This investigation verifies the effect of age regarding young people and news. The frequency of information consumption and interest in news increase as younger readers mature. The great unresolved question for newspapers is whether this increase in news consumption will be enough to guarantee a minimum readership in the future, a question currently posed by many authors (Huang, 2009; Lauf, 2001).

The genre variable reveals a paradox in that men consume more news but women value information more positively in terms of interest and civic importance.

The results of this survey also throw up new questions concerning young people’s consumption of information that will require further investigation. The two major questions are: the transformation in news consumption arising from young people’s preference for social networks as information media. Many authors point out that information consumption on the Internet is no longer a preferential activity because young people rarely search for news in an active way (Qayyum & al., 2010), rather they access it if the news story attracts their attention while they surf the Net. Instead of a deliberate, consious, routine search, news consumption has changed and is now based on chance and coincidence (Patterson, 2007). This results from the way young people use the Internet; just as they use the Internet for social interaction (Carlsson, 2001) and entertainment (Vanderbosch, Dhoets & Van der Bulck, 2009), they also use this technology in a recreational (Tully, 2008) and utilitarian way (Rubio, 2010), and so information loses its prominence. This has enormous consequences for newspaper distributors and the rest of the news media.

The second question relates to changes in the conception of news among young people. The results suggest that this is due to the emergence of a conception of news as public service rather than product, although this change is gradual. Therefore, information has to be freely available at any time like, for example, the public health service (Costera, 2007). Accessibility becomes a key factor, as young people demand quick and easy access to information.

Finally, another interesting strand is that young people start to see information as lacking in value, worthless in that being cost-free devalues the journalistic credibility of the product. This opens a great many questions about the future of journalism that will need to be studied in depth in future investigations.

Support

This investigation was a prizewinner at the 5th Edition of the University Research Prize awarded by the Asociación Catalana de Prensa Comarcal (2011). It is also linked to the P1-1B2010-53 project financed by the Fundación Caixa Castelló-Bancaixa.

References

AEDE (2010). Libro blanco de la prensa diaria 2010. Madrid: AEDE.

Arnould, V. (2004). Publishers Using Variety of Ways to Reach Next Generation of Readers. Newspapers Techniques, January 2004, 10-13.

Arroyo, M. (2006). Los jóvenes y la prensa: hábitos de consumo y renovación de contenidos. Ámbitos, 15, 271-282.

Bernal, A.I. (2009). Los nuevos medios de comunicación y los jóvenes. Aproximación a un modelo ideal de medio. Bruselas: Euroeditions.

Bernier, A. (2011). Representations of Youth in Local Media : Implications for Library Service. Library & Information Science Research, 33, 158-167. (DOI: 10.1016/j.lisr.2010.09.007).

Boyd, D.M. & Ellison, N.B. (2008). Social Network Sites: De finition, History, and Scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13, 210-230. (DOI: 10.1111/j.1083-6101. 2007. 00393.x).

Bringué, X. & Sádaba, C. (2009). La generación interactiva en España. Barcelona: Ariel.

Brites, M.J. (2010). Jovens (15-18 anos) e informação noticiosa: a importância dos capitais cultural e tecnológico. Estudos em Co municação, 8, 169-192.

Campos-Freire, F. (2008). Las redes sociales trastocan los modelos de medios de comunicación tradicionales. Revista Latina de Co mu nicación Social, 63, 287-293.

Carlsson, U. (2011). Young People in the Digital Media Culture. In C. Von Feilitzen, U. Carlsson & C. Bucht (Eds.). New Questions, New Insights, New Approaches (pp. 15-18). Göteborg: The International Clearinghouse on Children, Youth and Media. Nordicom.

Casero-Ripollés, A. (2010). Prensa en Internet: nuevos modelos de negocio en el escenario de la convergencia. El Profesional de la Información, 19, 6, 595-601. (DOI: 10.3145/epi.2010.nov05).

Corroy, L. (Ed.) (2008). Les jeunes et les médias. Paris: Vuibert.

Costera, I. (2007). The Paradox of Popularity: How Young Peo ple Experience the News. Journalism Studies, 8, 1, 96-116. (DOI: 10.1080/14616700601056874).

Domingo, D. (2005). Medios digitales: donde la juventud tiene la iniciativa. Revista de Estudios de Juventud, 68, 91-102.

Domínguez-Sánchez, M. & Sádaba-Rodríguez, I. (2005). Trans for maciones en las prácticas culturales de los jóvenes. De la lectura como ocio y consumo a la fragmentación neotecnológica. Revista de Estudios de Juventud, 70, 23-37.

Faucher, C. (2009). Fear and Loathing in the News: A Qualitative Analysis of Canadian Print News Coverage of Youthful Offending in the Twentieth Century. Journal of Youth Studies, 12, 4, 439-456. (DOI: 10.1080/13676260902897426).

Figueras, M. & Mauri, M. (2010). Mitjans de comunicació i joves. Barcelona: Generalitat de Catalunya.

García-Matilla, A. & Molina-Cañabate, J.P. (2008). Televisión y jóvenes en España. Comunicar, 31, 83-90. (DOI: 10.3916/c31-2008-01-010).

Huang, E. (2009). The Causes of Youth’s Low News Con sumption and Strategies for Making Youths Happy News Con su mers. Convergence, 15, 1, 105-122. (DOI: 10.1177/135 485 65 08 097021).

Islas, O. (2009). La convergencia cultural a través de la ecología de medios. Comunicar, 33, 25-33. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/ c33-2009-02-002).

Kotilainen, S. (2009). Participación cívica y producción mediática de los jóvenes: «Voz de la Juventud». Comunicar, 32, 181-192.

Lauf, E. (2001). Research Note: The Vanishing Young Reader. Sociodemographic determinants of newspaper use as a source of political information in Europe, 1980-1998. European Journal of Communication, 16, 2, 233-243. (DOI: 10.1177/0267323 10201 70 03692).

Lipani, M.C. (2008). Une reencontré du troisième type. In L. Corroy (Ed.), Les jeunes et les médias (pp. 13-36). Paris: Vuibert.

Livingstone, S. & Bovill, M. (1999). Young People, New Media : Report of the Research Project Children Young People and the Changing Media Environment. Research Report, Department of Media and Communications. London: London School of Econo mics and Political Science (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/21177/) (19-08-2011).

Livingstone, S. (2008). Taking Risky Opportunities in Youthful Content Creation: Teenagers’ Use of Social Networking Sites for Intimacy, Privacy and Self-Expression. New Media & Society, 10, 3, 393-411. (DOI: 10.1177/1461444808089415).

López-Vidales, N., González-Aldea, P. & Medina-de-la-Viña, E. (2011). Jóvenes y televisión en 2010: un cambio de hábitos. Zer, 30, 97-113.

Micó-Sanz, J.L. (2012). Ciberètica. TIC i canvi de valors. Bar celona: Barcino.

Navarro, L.F. (2003). Los hábitos de consumo en medios de comunicación en los jóvenes cordobeses. Comunicar, 21, 167-171.

Palfrey, J. & Gasser, U. (2008). Born Digital: Understanding the First Generation of Digital Natives. New York: Basic Books.

Parratt, S. (2010). Consumo de medios de comunicación y actitudes hacia la prensa por parte de los universitarios. Zer, 28, 133-149.

Patterson, T.E. (2007). Young People and News. Joan Sho rens tein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy. Harvard Uni versity: John F. Kennedy School of Government.

PEJ (Project for Excellence in Journalism) (2010). State of the News Media 2010. The Pew Research Center. (www.stateofthemedia.org/2010/index.php) (20-07-2011).

Pérez-Tornero, J.M. (2008). La sociedad multipantallas: retos para la alfabetización mediática. Comunicar, 31, 15-25. (DOI: 10. 3916/c31-2008-01-002).

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. MCB Uni versity Press, 9 (5). (www.marcprensky.com/ writing/ Prensky% 20-%20Digital%20Natives, %20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf) (21-07-2011).

Qayyum, M.A., Williamson, K. & al. (2010). Investigating the News Seeking Behavior of Young Adults. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 41, 3, 178-191

Raeymaeckers, K. (2002). Research Note: Young People and Patterns of Time Consumption in Relation to Print Media. Euro pean Journal of Communication, 17, 3, 369-383. (DOI: 10.1177/ 0267323102017003692).

Raeymaeckers, K. (2004). Newspapers Editors in Search of Young Readers: Content and Layout Strategies to Win New Readers. Jour nalism Studies, 5, 2, 221-232. (DOI: 10.1080/146167 004 200 0211195).

Romer, D., Jamieson, K.H. & Pasek, J. (2009). Building Social Capital in Young People: The Role of Mass Media and Life Out look. Political Communication, 26, 1, 65-83. (DOI: 10.10 80/ 105 84 600802622878).

Rubio, Á. (2010). Generación digital: patrones de consumo de In ternet, cultura juvenil y cambio social. Revista de Estudios de Ju ventud, 88, 201-221.

Tully, C.J. (2008). La apropiación asistemática de las nuevas tecnologías. Informalización y contextualización entre los jóvenes alemanes. Revista Internacional de Sociología (RIS), 49, 61-88. (DOI: 10.3989/ris.2008.i49.83).

Tuñez, M. (2009). Jóvenes y prensa en papel en la era de Internet. Estudio de hábitos de lectura, criterios de jerarquía de noticias, satisfacción con los contenidos informativos y ausencias temáticas. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 15, 503-524.

Van Dijk, J. (2006). The Network Society. London: Sage.

Vanderbosch, H., Dhoest, A. & Van der Bulck, H. (2009). News for Adolescents: Mission Impossible? An Evaluation of Flemish Television News Aimed at Teenagers. Communications, 34, 125-148. (DOI: 10.1515/COMM.2009.010).

WAN (World Association of Newspapers) (2010). The Paid vs. Free Content Debate. Shaping the Future of Newspapers, Strategy Report, 9, 2, 1-38.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El consumo de noticias está inmerso en un proceso de grandes mutaciones debido al avance de la digitalización. En este contexto, conocer los cambios en los hábitos de consumo de la audiencia es fundamental para calibrar el alcance y los efectos de la convergencia digital y sus perspectivas de futuro. Este artículo tiene como objetivo el análisis de esta transformación en un caso concreto: la relación de los jóvenes con la información periodística. Partiendo de una encuesta cuantitativa a personas de entre 16 y 30 años (N=549) se examinan sus hábitos de consumo y sus percepciones. Los resultados muestran la emergencia de las redes sociales como soporte informativo y el desgaste de los medios convencionales, especialmente de los diarios. No obstante, se detecta un interés elevado de los jóvenes hacia las noticias y una valoración positiva de las mismas en términos cívicos. Los datos revelan, además, el arraigo de la gratuidad. Finalmente, se constata la existencia de una brecha de género en el consumo informativo, a favor de los hombres, y la incidencia del efecto de la edad, que provoca un aumento del acceso a las noticias a medida que los jóvenes van madurando. Las conclusiones de la investigación sugieren la aparición de cambios profundos en los patrones de consumo y en la concepción de la información por parte del público joven.

1. Introducción

La digitalización introduce numerosos cambios en el sistema comunicativo. La producción de contenidos, las rutinas de trabajo, los soportes y estrategias de distribución y los modelos de negocio están sufriendo importantes alteraciones. Los patrones de consumo del público también están viviendo profundas transformaciones que están modificando sustancialmente sus dinámicas tradicionales.

En este contexto, conocer los cambios en los hábitos de consumo de la audiencia es fundamental para calibrar el alcance y los efectos de la convergencia digital y sus perspectivas de futuro. Para ello, este artículo se centra en el análisis del consumo de información de un segmento específico de la población: los jóvenes. Éstos son pioneros en la incorporación de las innovaciones tecnológicas asociadas a la digitalización hasta el punto que han sido llamados nativos digitales (Prensky, 2001; Palfrey & Gasser, 2008) o miembros de la generación interactiva (Bringué & Sádaba, 2009). Su condición de usuarios tempranos (Livingstone & Bovill, 1999) los convierte en un objeto de estudio privilegiado para explorar los cambios derivados del impacto de la era digital. Para estudiar su consumo de información en el marco de la convergencia, se parte aquí, inicialmente, de los diarios para, posteriormente, ampliar el foco de estudio a la información en general, independientemente del soporte usado. Los motivos que justifican esta elección son diversos: los diarios se han considerado, tradicionalmente, la fuente prioritaria y de referencia para informarse (Corroy, 2008), han protagonizado la mayor parte de las investigaciones sobre las relaciones entre los jóvenes y las noticias (Qayyum & al., 2010) y se encuentran en un proceso de fuerte redefinición derivado de la aguda crisis que padecen (Casero-Ripollés, 2010). Sin embargo, este trabajo no se limita a los diarios, sino que partiendo de ellos va más allá, ya que la convergencia impone el predominio de las interconexiones y las interdependencias dentro del escenario mediático.

Los objetivos de esta investigación son:

1) Conocer los hábitos de consumo de noticias y, particularmente, de lectura de diarios, de los jóvenes en la era digital.

2) Conocer las actitudes y percepciones de los jóvenes respecto de la información periodística.

Las hipótesis de investigación, conectadas a los anteriores, son las siguientes:

H1. El consumo de noticias de los jóvenes se está desplazando desde los diarios, que registran cifras bajas de lectura, hacia una multiplicidad de soportes, con preferencia por aquellos vinculados al ámbito on-line.

H2. Los jóvenes muestran un elevado interés por la información a la que, además, atribuyen valores positivos.

2. Revisión de la literatura

La investigación científica sobre el consumo informativo de los jóvenes se ha centrado, principalmente, en el análisis de los diarios. Estos estudios han certificado una constante pérdida de lectores entre los miembros de este colectivo. Se trata de una tendencia que se origina a mediados de la década de los noventa (Lauf, 2001) y que se extiende a la mayor parte de los países europeos (Brites, 2010; Lipani, 2008; Raeymaeckers, 2004). También España se ve afectada por esta dinámica, puesto que el porcentaje de jóvenes de 18 a 25 años que consume prensa impresa es del 25,7% (AEDE, 2010). Otros trabajos también confirman este alejamiento entre la juventud y los diarios en el ámbito español (Navarro, 2003; Arroyo, 2006; Túñez, 2009; Parratt, 2010).

Los motivos de este declive del consumo joven de diarios son diversos. La falta de tiempo, la preferencia por otros soportes y el poco interés en los contenidos son los principales (Huang, 2009; Bernal, 2009; Costera, 2007; Raeymaeckers, 2002). La reducida relevancia de las noticias para su vida cotidiana y la escasa conexión con sus experiencias personales y sus intereses se alzan como factores clave (Patterson, 2007; Vanderbosch, Dhoets & Van der Bulck, 2009; Qayyum et al., 2010). Los jóvenes no solo no se ven reflejados en los diarios y los medios convencionales (Domingo, 2005), sino que también ocupan una posición marginal en su agenda informativa. En este sentido, se ha constatado la invisibilidad de la juventud en las noticias (Figueras & Mauri, 2010; Kotilainen, 2009) e incluso la negatividad con la que frecuentemente es presentada (Túñez, 2009; Faucher, 2009; Bernier, 2011). Junto a estos aspectos, las transformaciones derivadas de la convergencia digital (Islas, 2009), que abre paso a una sociedad multipantallas (Pérez-Tornero, 2008), también inciden. El aumento de las ventanas y de los proveedores informativos, auspiciado por Internet, que genera una sobreabundancia de noticias y una fuerte competencia para captar la atención del público, explican, asimismo, este fenómeno en parte. Igualmente, la literatura científica coincide en señalar que la influencia parental tiene un impacto significativo en el consumo joven de prensa (Qayyum & al., 2010; Huang, 2009; Costera, 2007; Raeymaeckers, 2004; 2002).

El consumo informativo de la juventud se ve condicionado por dos factores clave. El primero es el efecto de la edad, puesto que, a medida que van madurando, el acceso e interés de los jóvenes por las noticias aumenta (Qayyum et al., 2010; Huang, 2009; Lipani, 2008). El segundo está relacionado con el género. Diversos autores detectan la existencia de una brecha que determina que los hombres desarrollan un consumo más intenso de noticias que las mujeres (Brites, 2010; Raeymaeckers, 2004; Navarro, 2003; Lauf, 2001).

El distanciamiento entre jóvenes y diarios provoca tres consecuencias. En primer lugar, la escasa incorporación de la juventud a la lectura de diarios supone la pérdida de una porción importante del público potencial y, por lo tanto, el deterioro del negocio para la prensa (Arnould, 2004). En segundo término, el envejecimiento de los consumidores de diarios no garantiza el relevo generacional de los lectores (Lauf, 2001). Finalmente, los diarios se han considerado, tradicionalmente, un elemento primordial de acceso a la esfera pública (Brites, 2010) y un vehículo de socialización política para los jóvenes (Romer, Jamieson & Pasek, 2009). En este sentido, el desinterés hacia la prensa puede degradar la conciencia cívica de la juventud.

3. Metodología

El diseño metodológico de esta investigación se basa en la aplicación de la encuesta cuantitativa. Esta técnica persigue la obtención de datos sobre aspectos objetivos (frecuencias) y subjetivos (opiniones y actitudes) basados en la información proporcionada por los sujetos entrevistados. El cuestionario utilizado está compuesto por preguntas cerradas de tres tipos: dicotómicas, de elección múltiple y de estimación, tomando una escala de valoración de 0 a 10. El estudio ha combinado preguntas de respuesta única y de respuesta múltiple.

El trabajo de campo se ha desarrollado entre los meses de enero y abril de 2011. El procedimiento empleado ha sido la entrevista personal cara a cara. Posteriormente, los datos se han tratado estadísticamente con el programa SPSS. Como variables dependientes se han utilizado la edad y el género. Por su parte, las variables independientes se refieren al consumo y a las percepciones sobre la información. Las primeras incluyen la frecuencia de lectura de diarios, los soportes de acceso a las noticias, el número de medios usados para informarse y la predisposición al pago. Las segundas se centran en el interés por las noticias y en el valor cívico atribuido a las mismas. La población está integrada por personas de entre 16 y 30 años residentes en Cataluña (España) que asciende a 1.284.005 individuos con datos del Idescat de 2009. La muestra, elaborada mediante selección aleatoria, es de 549 encuestas. La distribución por sexos de la muestra es la siguiente: 45,35% hombres y 54,65% mujeres.

4. Resultados

4.1. Frecuencia de lectura de diarios

Los jóvenes que afirman leer cada día la prensa suponen un 28,8% del total (tabla 1). Una cifra que evidencia un nivel de consumo de diarios reducido por parte de la juventud.

Los resultados refuerzan la importancia del efecto de la edad en el consumo de diarios, ya que a medida que los jóvenes van madurando se incrementa su interés por la prensa, que aumenta en 31,3 puntos (tabla 1). Estos datos demuestran que con la edad, los jóvenes adquieren una mayor necesidad de estar informados y un mayor interés por las noticias a la vez que se incrementan sus capacidades cognitivas para consumirlas (Huang, 2009). Dos factores explican este hecho. Por un lado, la juventud identifica los diarios con el mundo de los adultos (Raeymaeckers, 2004). Por otro, los jóvenes tienen una visión utilitarista de la prensa: cuando sus temas y contenidos les afecten directamente ya la leerán, mientras tanto se mantienen alejados al considerar sus contenidos y formatos poco adecuados a sus necesidades y expectativas (Vanderbosch, Dhoets & Van der Bulck, 2009). En este sentido, muchos vinculan el consumo de diarios al desarrollo de una actividad profesional y a su incorporación al mundo laboral (Lipani, 2008).

La variable de género permite corroborar que los hombres jóvenes presentan unos índices mayores de lectura de diarios que las mujeres. Entre los primeros, el 40,6% consume prensa cada día, mientras que entre las segundas la cifra de lectoras diarias desciende al 19% (tabla 1). Con ello, queda patente la existencia de una brecha de género en el consumo de diarios.

4.2. Soportes de acceso

En el actual contexto de sobreabundancia informativa, el acceso a las noticias no solo se canaliza a través de los diarios. Los jóvenes cuentan con una amplia gama de soportes a su disposición para informarse. Los resultados indican que éstos recurren a una multiplicidad de plataformas para configurar su dieta informativa. Junto a la importancia que adquiere la televisión (empleada por el 72,1% de los jóvenes) es especialmente significativo el papel que asumen las redes sociales como soporte de consumo de noticias entre el público joven (tabla 2). De hecho, estos sitios, como Facebook o Tuenti, ocupan la primera posición entre los soportes informativos y son usados por un 77,4% de los encuestados. Este dato es especialmente significativo por dos motivos.

En primer lugar, porque se trata de la constatación del creciente desplazamiento del consumo informativo de los jóvenes hacia el ámbito online (Parratt, 2010) y, específicamente, hacia las redes sociales. El predominio de estas plataformas en el acceso a las noticias de los jóvenes es una de las principales aportaciones de esta investigación. Por otra parte, es importante porque supone una alteración de los usos principales de las redes sociales entre la juventud. Hasta ahora diversos estudios (Livingstone, 2008; Campos Freire, 2008; Boyd & Ellison, 2008; Carlsson, 2011) habían puesto de manifiesto que los jóvenes dan a estos sitios una función preeminentemente comunicativa, centrada en el establecimiento de contactos e interacciones con su grupo de amistades y en la autoexpresión de su propia identidad personal. Estos nuevos datos muestran que, sin abandonar esos usos, la función informativa se está abriendo paso entre los usuarios jóvenes de las redes sociales.

También destaca el elevado uso que dan los jóvenes a las páginas web de los medios de comunicación como soporte de acceso a las noticias (56,6%). Por lo que se refiere específicamente a los diarios, la prensa de pago consigue atraer al 33,2% del total y la gratuita al 36,4%. El teléfono móvil, con un 28,4% del total, no logra situarse como una ventana de consumo de información consolidada para los jóvenes (tabla 2).

La variable de género también permite observar diferencias en la preferencia de soportes de acceso a la información por parte de los jóvenes. Los hombres son hegemónicos en la mayor parte de las plataformas y dispositivos, exceptuando la televisión, las tabletas digitales y la prensa gratuita en las que el porcentaje de mujeres es superior (tabla 2). Por su parte, los soportes donde se localiza con más intensidad el predominio masculino son las redes sociales y las páginas web de medios de comunicación.

La variable de la edad permite corroborar que, en la mayor parte de los soportes, se registra un aumento del uso por parte de los jóvenes a medida que éstos van madurando. Los diarios de pago, la radio, los blogs, Twitter, las redes sociales, el teléfono móvil y las páginas web de medios de comunicación se ven afectados por este efecto (tabla 2). A la inversa, la televisión ve cómo se reduce su uso informativo con el aumento de la edad. Unos resultados que concuerdan con la pérdida de protagonismo entre la audiencia juvenil experimentada por este medio audiovisual en los últimos años ante la emergencia de nuevos soportes (García Matilla & Molina Cañabate, 2008; López Vidales, González Aldea & Medina de la Viña, 2011).

4.3. Diversidad

Los resultados revelan que el público joven recurre a un número moderadamente elevado de medios de comunicación para informarse. El 73% del total afirma que usa, frecuentemente, de dos a tres medios diferentes para acceder a las noticias (tabla 3). Estos datos coinciden con el estudio realizado por Brites (2010: 185) que detectó que los jóvenes portugueses entre 15 y 17 años usaban una media de tres fuentes distintas para informarse. Con ello, podemos sostener que los jóvenes se configuran una dieta moderadamente variada que queda lejos de un consumo monomedia, que solo llega al 6% del total (tabla 3). Esta diversidad, pese a no ser elevada, ya que únicamente el 4,9% del total consulta más de 5 medios, sí que consigue romper con la dependencia cognitiva a una única fuente de noticias.

Las razones que explican esta notable competencia informativa de la juventud son múltiples: la facilidad en el acceso a las noticias que posibilita Internet, el incremento de la oferta informativa experimentada por el sistema mediático o la pluralidad de soportes usados por los jóvenes para consumir información, como se acaba de poner de manifiesto. La diversidad de medios utilizados para informarse incide directamente en el proceso de formación de la opinión pública y en la riqueza de la misma, ya que permite conocer una mayor variedad de puntos de vista sobre los acontecimientos y contar con más elementos de juicio (Kotilainen, 2009). Igualmente, la multiplicidad de medios utilizados por los jóvenes para acceder a las noticias está relacionada con cambios drásticos en el procesamiento de información entre la juventud (Rubio, 2010). Ésta aplica un efecto zapping al consumo de información para conseguir una impresión general de la actualidad (Costera, 2007). Esto supone una alteración del orden de lectura tradicional que pasa de ser lineal y progresivo a ser fragmentario, no secuencial, diagonal, interrumpido e hipertextual (Domínguez Sánchez & Sádaba Rodríguez, 2005). El recurso a diversas fuentes por parte de los jóvenes está conectado, así, con la transformación de sus hábitos de consumo informativo (Qayyum & al., 2010).

La edad vuelve a mostrarse como un factor decisivo a la hora de incrementar la pluralidad de fuentes de noticias utilizadas por los jóvenes. El porcentaje más elevado de personas que recurren a un único medio para informarse se registra entre los 16 y 17 años (tabla 3). Además, ningún integrante de esta franja usa más de 5 plataformas diferentes para consumir información. Justo lo contrario se detecta en el segmento de 23 o más años. En cuanto al género, los hombres registran unos niveles más altos de diversidad en el empleo de medios que las mujeres (tabla 3).

4.4. La consolidación de la gratuidad

Los resultados revelan que la práctica totalidad de los jóvenes son reacios a pagar para acceder a la información en Internet. Un 93,8% del total se muestran contrarios a sufragar las noticias con su propio dinero (tabla 4). Con ello, se hace patente la fuerte consolidación de la gratuidad en el consumo informativo online de las personas jóvenes. Únicamente el 6,2% del total expresa su disponibilidad a pagar por las noticias. Esta resistencia al pago no solo afecta a la juventud sino que se extiende al conjunto de la población. Diferentes estudios sitúan el porcentaje de las personas dispuestas a pagar por las noticias online entre el 10% y el 20% del total de lectores (WAN, 2010; PEJ, 2010).

Pese a que la edad atenúa la negativa al pago, el porcentaje de personas de 23 o más años dispuestas a sufragar las noticias online continúa siendo muy reducido, ya que se sitúa en el 9,1% (tabla 4). En cuanto a la variable de género, el volumen de hombres favorables a pagar es ligeramente superior al de mujeres (7,6% frente al 5%) (tabla 4).

El arraigo de la gratuidad queda demostrado al constatar que un 76,3% de los jóvenes consultaría otro medio de acceso libre si su sitio web favorito decidiera cobrar por las noticias (tabla 5). Incluso la gratuidad se configura como un potente factor que condiciona el consumo informativo del público joven en Internet. De hecho, un 17,1% de los integrantes de la muestra dejaría de consumir noticias si no encuentra un medio online gratuito (tabla 5).

4.5. El interés por la información

El conocimiento de las actitudes y percepciones de la juventud respecto de las noticias es un elemento fundamental puesto que condiciona su consumo informativo. En este sentido, un aspecto importante es el grado de interés hacia la información expresado por los jóvenes. Los resultados muestran que éstos conceden una puntuación media de 7,51, en una escala de 0 a 10, a esta cuestión (tabla 6). Por lo tanto, podemos deducir que las bajas cifras de consumo de noticias entre el público joven, particularmente en lo referente a la lectura de diarios, no están relacionadas con una apatía hacia la información. Todo lo contrario, los jóvenes tienen un elevado apetito por las noticias. El hecho de que les presten menos atención no se debe a la indiferencia, sino a que no quedan satisfechos con la manera cómo se les presenta la información, especialmente en los medios convencionales (Costera, 2007; Túñez, 2009; Huang, 2009; Raeymaeckers, 2002). En parte, este factor explicaría que los jóvenes se orienten hacia otros soportes, como las redes sociales, para obtener la información y que hayan abandonado, en gran medida, a la prensa (Lipani, 2008). Los diarios, al no adecuar su oferta a los intereses y necesidades de los lectores jóvenes, están viendo cómo éstos dejan de considerarlos una fuente prioritaria de información (Corroy, 2008).

El efecto de la edad se evidencia nuevamente. El grado de interés atribuido por los jóvenes a la información se incrementa notablemente a medida que éstos se convierten en adultos. Por su parte, la variable de género muestra una paradoja. Si bien los indicadores anteriores (frecuencia de lectura, número de medios utilizados o disposición al pago) señalan un consumo informativo más intenso entre los hombres, las mujeres manifiestan un mayor grado de interés por las noticias que éstos. Aunque la diferencia es reducida, 7,57 frente a 7,43 (tabla 6), resulta interesante señalarla. Algo similar ocurre con la importancia cívica otorgada a la información (tabla 7).

Los jóvenes conceden también a la información un alto valor cívico. En una escala de 0 a 10, la juventud atribuye un grado de importancia de 8,2 de media al hecho de estar informado para participar políticamente y ser un buen ciudadano (tabla 7). Por lo tanto, las personas jóvenes conceden a las noticias un papel trascendental en términos democráticos. La información se alza como una fuente que posibilita y garantiza tanto el acceso al debate público como el desarrollo de una conciencia cívica. Estar bien informado se percibe como sinónimo de un ejercicio pleno y responsable de la ciudadanía. Así, se pone de manifiesto que las noticias juegan un rol destacado en la socialización cívica y política de los jóvenes (Romer, Jamieson & Pasek, 2009) y que éstos les atribuyen una concepción positiva en este sentido. Los jóvenes están dando, progresivamente, la espalda a los medios convencionales, no a la información.

5. Discusión y conclusiones

Los resultados permiten verificar las dos hipótesis formuladas al inicio de este artículo. Los datos demuestran que el consumo informativo de los jóvenes se orienta hacia los nuevos soportes, especialmente hacia las redes sociales, a la vez que se registra un desgaste de los diarios, que presentan cifras bajas de lectura (H1). En consecuencia, éstos están quedando desacralizados como fuente primaria de información en el contexto digital (Lipani, 2008). No obstante, eso no quiere decir que el apetito de la juventud por las noticias sea débil. Todo lo contrario, se detecta un interés latente de los jóvenes por la información que, además, se asocia a un alto valor cívico (H2).

Asimismo, se observa una diversificación del número de fuentes donde se informan. El consumo de noticias se está fragmentando en múltiples soportes, no todos con el mismo protagonismo, en una tendencia que remite a los efectos de la distribución multiplataforma de los contenidos periodísticos y de los consumos sincrónicos de unos jóvenes capaces de encadenar varias actividades mediáticas a la vez gracias a su capacidad multitarea (Micó, 2012; Van Dijk, 2006).

Los datos revelan, también, el sólido arraigo de la gratuidad en el acceso a las noticias entre el público joven. Una constatación que supone un problema grave para la financiación de los medios, en general, y de los diarios, en especial, puesto que afecta a su modelo de negocio (Casero-Ripollés, 2010).

La investigación corrobora la incidencia del efecto de la edad en la relación de los jóvenes con las noticias. La frecuencia, interés y riqueza de su consumo informativo se incrementan a medida que éstos van madurando. Pese a ello, la pregunta pendiente, en el caso de los diarios, es si este aumento bastará para garantizar un volumen de lectores suficiente en el futuro, aspecto que cuestionan algunos autores (Huang, 2009; Lauf, 2001).

En cuanto a la variable de género, los resultados revelan una paradoja. Por un lado, los hombres ostentan, claramente, la primacía en el consumo de noticias, demostrando la existencia de una brecha de género. Pero, por otro, las mujeres otorgan una valoración más positiva a la información en términos de interés e importancia cívica.

Pese a estas aportaciones, esta investigación también abre nuevos interrogantes sobre el consumo informativo de los jóvenes que deberán abordarse en futuros trabajos. Éstos se refieren, principalmente, a dos grandes cuestiones. En primer lugar, las transformaciones en el consumo de noticias derivadas de la preferencia de la juventud por las redes sociales como soporte informativo. En este sentido, son varios los autores que señalan que en Internet el consumo informativo deja de ser una actividad preferente ya que, raramente, los jóvenes buscan activamente noticias (Qayyum & al., 2010), sino que acceden a ellas si les llaman la atención mientras están navegando. Más que una búsqueda deliberada, consciente y rutinaria, el consumo de noticias pasa a basarse en la casualidad y la coincidencia (Patterson, 2007). Esto se debe a que el uso de Internet por parte de los jóvenes se enfoca hacia la interacción social (Carlsson, 2011) y el entretenimiento (Vanderbosch, Dhoets & Van der Bulck, 2009) ya que, entre este colectivo, prima un empleo lúdico (Tully, 2008) y utilitario (Rubio, 2010) de esta tecnología. En este contexto, la información pierde el protagonismo. Algo que puede tener profundas consecuencias para los diarios y el resto de proveedores mediáticos de noticias.

La segunda cuestión tiene que ver con la irrupción de cambios en la concepción de la información entre los jóvenes. Los resultados sugieren que esta transformación se despliega en dos frentes complementarios. Por un lado, está emergiendo, todavía de manera moderada, una forma de entender las noticias como un servicio público en lugar de como un producto. Bajo este nuevo prisma, la información tiene que estar disponible, preferiblemente gratis, a cualquier hora y en cualquier momento, como, por ejemplo, la sanidad pública (Costera, 2007). La accesibilidad se alza, así, como una cualidad clave, ya que los jóvenes priman la facilidad y la rapidez a la hora de informarse.

Finalmente, por otro lado, las personas jóvenes están empezando a considerar la información como algo desprovisto de valor, como algo que no vale nada. La gratuidad desvaloriza el producto periodístico, que pierde su valor de cambio. Algo que abre numerosas incógnitas sobre el futuro del periodismo en las que será necesario profundizar con nuevas investigaciones.

Apoyos

Esta investigación ha sido galardonada con el 5º Premio de Investigación Universitaria concedido por la Asociación Catalana de Prensa Comarcal (2011). También está vinculada al proyecto P1-1B2010-53, financiado por la Fundación Caixa Castelló-Bancaixa.

Referencias

AEDE (2010). Libro blanco de la prensa diaria 2010. Madrid: AEDE.

Arnould, V. (2004). Publishers Using Variety of Ways to Reach Next Generation of Readers. Newspapers Techniques, January 2004, 10-13.

Arroyo, M. (2006). Los jóvenes y la prensa: hábitos de consumo y renovación de contenidos. Ámbitos, 15, 271-282.

Bernal, A.I. (2009). Los nuevos medios de comunicación y los jóvenes. Aproximación a un modelo ideal de medio. Bruselas: Euroeditions.

Bernier, A. (2011). Representations of Youth in Local Media : Implications for Library Service. Library & Information Science Research, 33, 158-167. (DOI: 10.1016/j.lisr.2010.09.007).

Boyd, D.M. & Ellison, N.B. (2008). Social Network Sites: De finition, History, and Scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13, 210-230. (DOI: 10.1111/j.1083-6101. 2007. 00393.x).

Bringué, X. & Sádaba, C. (2009). La generación interactiva en España. Barcelona: Ariel.

Brites, M.J. (2010). Jovens (15-18 anos) e informação noticiosa: a importância dos capitais cultural e tecnológico. Estudos em Co municação, 8, 169-192.

Campos-Freire, F. (2008). Las redes sociales trastocan los modelos de medios de comunicación tradicionales. Revista Latina de Co mu nicación Social, 63, 287-293.

Carlsson, U. (2011). Young People in the Digital Media Culture. In C. Von Feilitzen, U. Carlsson & C. Bucht (Eds.). New Questions, New Insights, New Approaches (pp. 15-18). Göteborg: The International Clearinghouse on Children, Youth and Media. Nordicom.

Casero-Ripollés, A. (2010). Prensa en Internet: nuevos modelos de negocio en el escenario de la convergencia. El Profesional de la Información, 19, 6, 595-601. (DOI: 10.3145/epi.2010.nov05).

Corroy, L. (Ed.) (2008). Les jeunes et les médias. Paris: Vuibert.

Costera, I. (2007). The Paradox of Popularity: How Young Peo ple Experience the News. Journalism Studies, 8, 1, 96-116. (DOI: 10.1080/14616700601056874).

Domingo, D. (2005). Medios digitales: donde la juventud tiene la iniciativa. Revista de Estudios de Juventud, 68, 91-102.

Domínguez-Sánchez, M. & Sádaba-Rodríguez, I. (2005). Trans for maciones en las prácticas culturales de los jóvenes. De la lectura como ocio y consumo a la fragmentación neotecnológica. Revista de Estudios de Juventud, 70, 23-37.

Faucher, C. (2009). Fear and Loathing in the News: A Qualitative Analysis of Canadian Print News Coverage of Youthful Offending in the Twentieth Century. Journal of Youth Studies, 12, 4, 439-456. (DOI: 10.1080/13676260902897426).

Figueras, M. & Mauri, M. (2010). Mitjans de comunicació i joves. Barcelona: Generalitat de Catalunya.

García-Matilla, A. & Molina-Cañabate, J.P. (2008). Televisión y jóvenes en España. Comunicar, 31, 83-90. (DOI: 10.3916/c31-2008-01-010).

Huang, E. (2009). The Causes of Youth’s Low News Con sumption and Strategies for Making Youths Happy News Con su mers. Convergence, 15, 1, 105-122. (DOI: 10.1177/135 485 65 08 097021).

Islas, O. (2009). La convergencia cultural a través de la ecología de medios. Comunicar, 33, 25-33. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/ c33-2009-02-002).

Kotilainen, S. (2009). Participación cívica y producción mediática de los jóvenes: «Voz de la Juventud». Comunicar, 32, 181-192.

Lauf, E. (2001). Research Note: The Vanishing Young Reader. Sociodemographic determinants of newspaper use as a source of political information in Europe, 1980-1998. European Journal of Communication, 16, 2, 233-243. (DOI: 10.1177/0267323 10201 70 03692).

Lipani, M.C. (2008). Une reencontré du troisième type. In L. Corroy (Ed.), Les jeunes et les médias (pp. 13-36). Paris: Vuibert.

Livingstone, S. & Bovill, M. (1999). Young People, New Media : Report of the Research Project Children Young People and the Changing Media Environment. Research Report, Department of Media and Communications. London: London School of Econo mics and Political Science (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/21177/) (19-08-2011).

Livingstone, S. (2008). Taking Risky Opportunities in Youthful Content Creation: Teenagers’ Use of Social Networking Sites for Intimacy, Privacy and Self-Expression. New Media & Society, 10, 3, 393-411. (DOI: 10.1177/1461444808089415).

López-Vidales, N., González-Aldea, P. & Medina-de-la-Viña, E. (2011). Jóvenes y televisión en 2010: un cambio de hábitos. Zer, 30, 97-113.

Micó-Sanz, J.L. (2012). Ciberètica. TIC i canvi de valors. Bar celona: Barcino.

Navarro, L.F. (2003). Los hábitos de consumo en medios de comunicación en los jóvenes cordobeses. Comunicar, 21, 167-171.

Palfrey, J. & Gasser, U. (2008). Born Digital: Understanding the First Generation of Digital Natives. New York: Basic Books.

Parratt, S. (2010). Consumo de medios de comunicación y actitudes hacia la prensa por parte de los universitarios. Zer, 28, 133-149.

Patterson, T.E. (2007). Young People and News. Joan Sho rens tein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy. Harvard Uni versity: John F. Kennedy School of Government.

PEJ (Project for Excellence in Journalism) (2010). State of the News Media 2010. The Pew Research Center. (www.stateofthemedia.org/2010/index.php) (20-07-2011).

Pérez-Tornero, J.M. (2008). La sociedad multipantallas: retos para la alfabetización mediática. Comunicar, 31, 15-25. (DOI: 10. 3916/c31-2008-01-002).

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. MCB Uni versity Press, 9 (5). (www.marcprensky.com/ writing/ Prensky% 20-%20Digital%20Natives, %20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf) (21-07-2011).

Qayyum, M.A., Williamson, K. & al. (2010). Investigating the News Seeking Behavior of Young Adults. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 41, 3, 178-191

Raeymaeckers, K. (2002). Research Note: Young People and Patterns of Time Consumption in Relation to Print Media. Euro pean Journal of Communication, 17, 3, 369-383. (DOI: 10.1177/ 0267323102017003692).

Raeymaeckers, K. (2004). Newspapers Editors in Search of Young Readers: Content and Layout Strategies to Win New Readers. Jour nalism Studies, 5, 2, 221-232. (DOI: 10.1080/146167 004 200 0211195).

Romer, D., Jamieson, K.H. & Pasek, J. (2009). Building Social Capital in Young People: The Role of Mass Media and Life Out look. Political Communication, 26, 1, 65-83. (DOI: 10.10 80/ 105 84 600802622878).

Rubio, Á. (2010). Generación digital: patrones de consumo de In ternet, cultura juvenil y cambio social. Revista de Estudios de Ju ventud, 88, 201-221.

Tully, C.J. (2008). La apropiación asistemática de las nuevas tecnologías. Informalización y contextualización entre los jóvenes alemanes. Revista Internacional de Sociología (RIS), 49, 61-88. (DOI: 10.3989/ris.2008.i49.83).

Tuñez, M. (2009). Jóvenes y prensa en papel en la era de Internet. Estudio de hábitos de lectura, criterios de jerarquía de noticias, satisfacción con los contenidos informativos y ausencias temáticas. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 15, 503-524.

Van Dijk, J. (2006). The Network Society. London: Sage.

Vanderbosch, H., Dhoest, A. & Van der Bulck, H. (2009). News for Adolescents: Mission Impossible? An Evaluation of Flemish Television News Aimed at Teenagers. Communications, 34, 125-148. (DOI: 10.1515/COMM.2009.010).

WAN (World Association of Newspapers) (2010). The Paid vs. Free Content Debate. Shaping the Future of Newspapers, Strategy Report, 9, 2, 1-38.

Document information

Published on 30/09/12

Accepted on 30/09/12

Submitted on 30/09/12

Volume 20, Issue 2, 2012

DOI: 10.3916/C39-2012-03-05

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?