Highlights

- We examined the moderating effect of anxiety sensitivity on relations between smoking rate and clinical aspects of smoking

- Low anxiety sensitivity predicts lower tobacco dependence and lower rates of smoking expectancies and reasons for quitting

- These relations are not explained by related covariates including, alcohol use, medical problems, anxiety disorders, and more

Abstract

The current study examined the moderating effects of smoking amount per day on the relation between anxiety sensitivity and nicotine dependence, cigarette smoking outcome expectancies, and reasons for quitting smoking among 465 adult, treatment-seeking smokers (48% female; Mage = 36.6, SD = 13.5). Smoking amount per day moderated the relation between anxiety sensitivity and nicotine dependence, smoking expectancies for negative consequences and appetite control as well as intrinsic reasons for quitting. However, no moderating effect was evident for negative reinforcement expectancies. The form of the significant interactions indicated across dependent variables lower levels of smoking amount per day suppressed the relation between anxiety sensitivity and smoking related dependent variable, such that the positive relation of anxiety sensitivity to smoking dependence and cognitive–affective aspects of smoking is weaker in heavier smokers and more robust in lighter smokers.

Keywords

Smoking;Anxiety sensitivity;Quitting;Nicotine;Smoking motives

1. Smoking amount per day moderates the relation of anxiety sensitivity for smoking dependence and cognitive–affective aspects of smoking among treatment-seeking smokers

Anxiety disorders are among the most common psychiatric conditions (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005). Numerous clinical and epidemiological studies indicate higher amount per days of smoking among the anxiety-disordered population relative to both persons with no psychiatric illness as well as those with other psychiatric conditions (Lasser et al., 2000 ; McCabe et al., 2004). One means of elucidating the role of anxiety in smoking maintenance and dependence is to investigate the influence of transdiagnostic psychological vulnerability factors that influence anxiety-related conditions on smoking. Anxiety sensitivity is one of the transdiagnostic vulnerability factors that reflect the tendency to fear anxiety-related sensations (Reiss, Peterson, Gursky, & McNally, 1986). Indeed, anxiety sensitivity is a core transdiagnostic vulnerability factor for the etiology and maintenance of multiple anxiety disorders (e.g., panic and social anxiety) and other emotional disorders (e.g., depression and PTSD; Hayward et al., 2000; Maller and Reiss, 1992; McNally, 2002; Marshall et al., 2010; Schmidt et al., 1999; Schmidt et al., 2006 ; Taylor, 2003).

Recent research also indicates that anxiety sensitivity is associated with, and may contribute to, numerous aspects of smoking behavior. For example, anxiety sensitivity is positively correlated with smoking motives and expectancies for negative affect reduction as well as expectancies for negative consequences and sensorimotor effects (e.g., appetite control) of smoking (Comeau et al., 2001; Johnson et al., 2013; Leyro et al., 2008 ; Novak et al., 2003). From a cessation perspective, smokers higher relative to lower in anxiety sensitivity perceive quitting as more difficult (Zvolensky, Vujanovic, et al., 2007b), experience more intense nicotine withdrawal during smoking deprivation (Johnson et al., 2012; Langdon et al., 2013; Marshall et al., 2009; Vujanovic and Zvolensky, 2009 ; Zvolensky, Lejuez, Kahler and Brown, 2004), and are at greater odds of early lapse/relapse (Assayag et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2001; Zvolensky, Bernstein, et al., 2007; Zvolensky et al., 2009 ; Zvolensky et al., 2006). Importantly, the observed anxiety sensitivity-smoking effects are not explained by smoking amount per day, nicotine dependence, gender, other concurrent substance use (e.g., alcohol, cannabis), panic attack history, or trait-like negative mood propensity (Johnson et al., 2013 ; Wong et al., 2013).

Although promising, extant work has only begun to explore the interplay between anxiety sensitivity and differing levels of smoking behavior. Research has found that anxiety sensitivity moderates daily smoking amount per day in regard to the expression of anxiety symptoms and catastrophic thinking, such that higher levels of anxiety sensitivity and higher smoking amount per day are associated with greater anxiety (Leen-Feldner et al., 2007; McLeish et al., 2007; McLeish et al., 2009 ; Zvolensky, Kotov, Antipova and Schmidt, 2003). Integrative models of anxiety-smoking comorbidity posit that anxiety sensitivity may similarly interplay with smoking amount per day in relation to smoking processes, but possibly in a different manner (Zvolensky & Bernstein, 2005). Namely, smoking amount per day may diminish the relation between anxiety sensitivity and certain processes that relate to nicotine dependence and cognitive–affective aspects of smoking addiction at lower levels of anxiety sensitivity. Specifically, even lower smoking amount per day may be sufficient to elicit internal sensations that trigger catastrophic thinking (e.g., “I'm going to die”; “I am losing control”). Despite this possibility, no research has examined the moderating role of smoking rate per day on the relations between anxiety sensitivity and smoking-related processes, leaving a clinically significant gap in extant knowledge. Although the average cigarette consumption per smoker has decreased since the 1990s, nicotine dependence levels among smokers have remained stable (Jarvis, Giovino, O'Connor, Kozlowski, & Bernet, 2014). Thus, the exploration of factors that may influence the maintenance of smoking and smoking-based processes represents an important area of study.

Together, the present investigation evaluated the moderating role of smoking amount per day in regard to the relations between anxiety sensitivity and nicotine dependence, outcome expectancies (mood and sensorimotor) for smoking, and intrinsic reasons for quitting among daily smokers seeking treatment for smoking cessation. It was hypothesized that smoking amount per day would moderate the effect of anxiety sensitivity in regard to nicotine dependence, smoking outcome expectancies (negative consequences, negative reinforcement/negative affect reduction, and appetite control), and (intrinsic) reasons for quitting among smokers with lower (versus higher) smoking amount per day. These outcomes were chosen as dependent variables as they consistently are related to smoking behavior (Brandon & Baker, 1991), and thus, represent important targets for study and treatment development. Specifically, it was expected that lower levels of smoking amount per day would suppress the relation between anxiety sensitivity and smoking related dependent variable, such that the positive relation of anxiety sensitivity to smoking dependence and cognitive–affective aspects of smoking is weaker in heavier smokers and more robust in lighter smokers. It was additionally hypothesized that these associations would be found above and beyond the effects of other variables that affect smoking/anxiety relations, including gender, negative affectivity, alcohol use, medical problems, DSM-IV defined Axis-I disorders, and substance use.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants included 465 adult smokers (48% female; Mage = 36.6, SD = 13.5) who responded to study advertisements (e.g., flyers, newspaper ads, radio announcements). In terms of ethnic background, 85.6% of participants identified as Caucasian, 7.9% identified as African–American, 2.9% identified as Hispanic, 1.1% identified as Asian, and 2.5% identified as “other.” Participants reported smoking an average of 16.5 cigarettes per day (SD = 9.9), smoking their first cigarette at 14.8 years of age (SD = 3.4), and initiating regular (daily) smoking at 17.4 years of age (SD = 3.7). The average score on the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991) was 5.1 (SD = 2.3), indicating moderate levels of nicotine dependence. Participants were compensated $12.50 in cash for participation in the baseline appointment.

As determined by the baseline Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Non-Patient Version (SCID-I/NP; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2007), 44.3% of the sample met criteria for current (past year) Axis I psychopathology, with 21% meeting criteria for more than one diagnosis. The most common diagnoses were social anxiety disorder (14.3%), GAD, (8.5%), and current MDD (7%). Among participants with current psychopathology, the average number of diagnoses per participant was 1.4 (SD = 0.5).

Participants were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) current (past month) use of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation; (2) limited mental competency and inability to provide informed, voluntary, written consent; (3) endorsement of current or past psychotic-spectrum symptoms via structured interview screening; and (4) current suicidality or homicidality.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic questionnaire

Demographic information collected included age, gender, race, educational attainment, marital status, and employment. These data were used for descriptive purposes, and gender was used as a covariate in all analyses.

2.2.2. Structured Clinical Interview-Non-Patient Version for DSM-IV (SCID-N/P; First et al., 2007)

Diagnostic assessments for Axis I disorders and substance use disorders were performed using the SCID-N/P. The interviews were administered by trained staff and supervised by independent doctoral-level psychologists. All interviews were audio-taped and the reliability of a random selection of approximately 12.5% of interviews was checked (MJZ) for accuracy; no cases of diagnostic coding disagreement were noted.

2.2.3. Smoking History Questionnaire (SHQ; Brown, Lejuez, Kahler, & Strong, 2002)

The SHQ is a self-report questionnaire used to assess smoking history and pattern (e.g., smoking amount per day, age of onset of initiation). It has been successfully used in previous studies as a measure of smoking history (Zvolensky et al., 2004b). The present study utilized this measure to describe the sample holistically, and the item “average number of cigarettes per day” to index smoking amount per day.

2.2.4. Medical history form

Current and lifetime medical illnesses and current use of prescribed medication were assessed using a medical history checklist. For current and lifetime medical illnesses, a composite variable was computed for the present study as an index of tobacco-related medical illnesses, which was used as a covariate in all models. Items in which participants indicated having ever been diagnosed (respiratory disease, asthma, heart problems, and hypertension, all coded 0 = no, 1 = yes) were summed to create a total score (observed range from 0 to 4), with greater scores reflecting the presence of multiple markers of tobacco-related medical illnesses. The medical history form has been utilized as an indicator of medical problems among cigarette smokers in other work (e.g., Zvolensky, Farris, Leventhal, & Schmidt, 2014).

2.2.5. Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993)

The AUDIT is a 10-item self-report measure developed to identify individuals with problematic drinking. Its scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores reflecting more problematic drinking. In the current study, AUDIT score was used to index level of alcohol consumption. Psychometric properties for the AUDIT are well documented (e.g., Saunders et al., 1993). In the current investigation, internal consistency for the AUDIT total score was good (Cronbachs α = .89).

2.2.6. Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988)

The PANAS is a self-report measure on which participants rate the extent to which they experience each of 20 different feelings and emotions (e.g., interested, nervous) on a Likert-type scale (1 = “very slightly or not at all” to 5 = “extremely”). The measure yields two factors (negative and positive affect) with strong documented psychometric properties. The negative affectivity subscale (PANAS-NA) internal consistency was good in the present sample (Cronbachs α = .88).

2.2.7. Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3; Taylor et al., 2007)

The ASI-3 is an 18-item self-report measure of the sensitivity to, and fear of the potential negative consequences of anxiety-related symptoms and sensations. The ASI-3 was derived, in part, from the original ASI (Reiss & McNally, 1985). The ASI-3 is a self-report measure on which participants rate the extent to which they concerned about the possible negative consequences of anxiety (e.g. “It scares me when my heart beats fast”) on a Likert-Type scale (0 = very little to 4 = very much). In the present study, we utilized the ASI-3 total score (sum of scores for all 18 ASI-3 items; score ranges from 0 to 72). Internal consistency of ASI-III was good (Cronbachs alpha = .90).

2.2.8. Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton et al., 1991)

This instrument is a well-established six-item scale designed to assess gradations in nicotine dependence. This measure exhibits adequate internal consistency, high degrees of test–retest reliability (Pomerleau, Carton, Lutzke, Flessland, & Pomerleau, 1994), and positive relations with key smoking variables (e.g., salivary cotinine; Heatherton et al., 1991 ; Payne et al., 1994). The FTND demonstrated typical-range internal consistency among the present study sample (Cronbachs alpha = .60; Korte, Capron, Zvolensky, & Schmidt, 2013).

2.2.9. Smoking Consequences Questionnaire (SCQ; Brandon & Baker, 1991)

The SCQ is a 50-item self-report measure on which respondents indicate, on a 10-point Likert-type scale (0 = completely unlikely to 10 = completely likely), an individuals expectancies about cigarette smoking. The SCQ includes four subscales: positive reinforcement (15 items; e.g. “I enjoy the taste sensations while smoking”), negative reinforcement/negative affect reduction (12 items; e.g., “Smoking helps me calm down when I feel nervous”), negative consequences (18 items; e.g., “The more I smoke, the more I risk my health”), and appetite control (5 items; “Smoking helps me control my weight”). The SCQ and its constituent factors have excellent psychometric properties (Brandon and Baker, 1991; Buckley et al., 2005 ; Downey and Kilbey, 1995). In the present study, the SCQ subscales demonstrated good internal consistency with Cronbach alphas ranging from .82 to .89. The negative consequences, negative reinforcement/negative affect reduction, and appetite control were employed in the current investigation, as they were theoretically apt to interplay with anxiety sensitivity (Leventhal & Zvolensky, 2015).

2.2.10. Reasons for Quitting Scale (RFQ; Curry, Wagner, & Grothaus, 1990)

The RFQ is composed of 20 self-report items and measures intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for quitting smoking. The RFQ consists of two intrinsic motivation subscales: self-control (“To show myself I can quit if I really want to”) and health concerns (“Because I'm concerned that smoking will shorten my life”), and two extrinsic motivation subscales: immediate reinforcement (“To save money that I spend on cigarettes”) and social pressure (“Because someone has given me an ultimatum to quit”). The RFQ has demonstrated good psychometric properties in past work (Curry, McBride, Grothaus, Louie, & Wagner, 1995). In the present study, only the two intrinsic motivation subscales of the SCQ—health concerns and self-control—were utilized (Cronbach alphas .87 and .90, respectively). The two extrinsic subscales were not employed because there was no theoretical basis to suggest that anxiety sensitivity would be related to this type of reason for quitting.

2.3. Procedure

Interested participants who met the initial requirements during a telephone screen were scheduled to come in for a structured clinical interview to assess the presence or absence of any Axis I condition. Individuals who were deemed eligible after the screening/interview process were then scheduled to come in for a baseline appointment to complete various demographic, smoking, anxiety, and substance use assessments, presented in the same order to each participant. Following written informed consent, participants were interviewed using the SCID-I/NP and completed a computerized self-report battery. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Vermont and Florida State University (clinicaltrials.gov # NCT01753141). The current study is based on secondary analyses of baseline (pre-treatment) data for a subset of the sample, which was selected on the basis of complete data for all studied variables.

2.4. Analytic strategy

First, a series of zero-order correlations were conducted to examine associations between study variables. To test the main and interactive affects effects of anxiety sensitivity and smoking amount per day on the criterion variables, a Generalized Linear Modeling (GLM) in Proc GLM (SAS 9.4) was employed. Specifically, hierarchical regression analyses were conducted. In the first step of each model, gender (coded as male/female), tobacco-related medical illness (total number of illnesses as indicated on the Medical Screening Questionnaire), alcohol consumption (as determined by the AUDIT), negative affectivity (as determined by the PANAS), non-alcohol substance abuse problems (as determined by the SCID-N/P), and current Axis I disorders (as determined by the SCID-N/P) were entered as covariates (see 1). Next, anxiety sensitivity and smoking amount per day were entered (second step). Finally, the interaction term between smoking amount per day and anxiety sensitivity was entered at the third step. Continuous variables were grand mean centered. Nicotine dependence, smoking expectancies, and reasons for quitting were examined as dependent variables in separate conceptually-nested models. Given the multiple hypotheses tested in this analysis, a False Discovery Rate (FDR) control test was used to control for Type-I error (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive data

Descriptive data and correlations of the all variables included in the models are presented in Table 1. Anxiety sensitivity was significantly and positively related with all outcome variables. Smoking amount per day was significantly and positively correlated with RFQ-health concerns. Importantly, smoking amount per day and anxiety sensitivity were not significantly related, sharing approximately 0.01% variance.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gendera | 1 | .14** | − .11* | .00 | .19** | − .02 | − .08 | .08 | − .01 | .18** | .16** | .26** | .17** | .09 |

| 2. Negative affectb | 1 | .24** | .01 | .39** | .14** | .00 | .63** | .06 | .38** | .18** | .11* | .11* | .05 | |

| 3. AUDITc | 1 | − .11* | .09 | .18** | − .06 | .21** | − .12* | .16** | .07 | .01 | − .01 | .01 | ||

| 4. Medical problemsd | 1 | .08* | − .08 | .00 | .01 | − .02 | .− .10* | .02 | .00 | .14** | .10* | |||

| 5. Axis-I disordere | 1 | .09 | .03 | .36** | .13** | .20** | .05 | .11* | .09* | .12** | ||||

| 6. Substance usee | 1 | − .03 | .15** | − .04 | .03 | − .07 | .03 | − .07 | .00 | |||||

| 7. Cig per dayf | 1 | .01 | .57** | .02 | .06 | .04 | .09 | .05 | ||||||

| 8. ASg | 1 | .14** | .30** | .16** | .13** | .22** | .18** | |||||||

| 9. FTNDh | 1 | .18** | .18** | .17** | .21** | .18** | ||||||||

| 10. SCQ negative reinforcementi | 1 | .39** | .42** | .15** | .11* | |||||||||

| 11. SCQ negative consequencesi | 1 | .26** | .54** | .25** | ||||||||||

| 12. SCQ appetite controli | 1 | .12** | .13** | |||||||||||

| 13. RFQ health concernsj | 1 | .32** | ||||||||||||

| 14. RFQ self controlj | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Mean (or n) | 465 | 19.06 | 6.19 | .36 | 250 | 1.08 | 16.82 | 15.14 | 5.14 | 6.50 | 5.15 | 6.55 | 14.49 | 14.62 |

| SD (or %) 48%(female) | 7.06 | 6.01 | .62 | 44.3% | .28 | 9.05 | 12.28 | 2.28 | 1.25 | 2.37 | 1.28 | 3.84 | 4.01 |

Note: aGender = % listed are females (coded 0 = male; 1 = female). bNA = Positive and Negative Affect Scale—Negative Affect subscale. cAUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test—total score. dMedical problems = tobacco-related medical illnesses per the Medical Screening Questionnaire. eAxis I Disorder = Current Axis I disorder per the Structured Clinical Interview—Non-Patient Version for DSM-IV. eSubstance use = current non-alcohol substance abuse/dependence diagnosis per the Structured Clinical Interview—Non-Patient Version for DSM-IV. fCPD = number of cigarettes per day during past week per the Smoking History Questionnaire. gAS = Anxiety Sensitivity Index-III—total score. hFTND = Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence; iSCQ negative consequences, iSCQ appetite control, iSCQ negative reinforcement = the subscales of Smoking Consequences Questionnaire. jRFQ health concerns and jRFQ self-control = the subscales of Reasons for Smoking Scale.

- . p < .05.

- . p < .01.

3.2. GLM analyses

3.2.1. Nicotine dependence

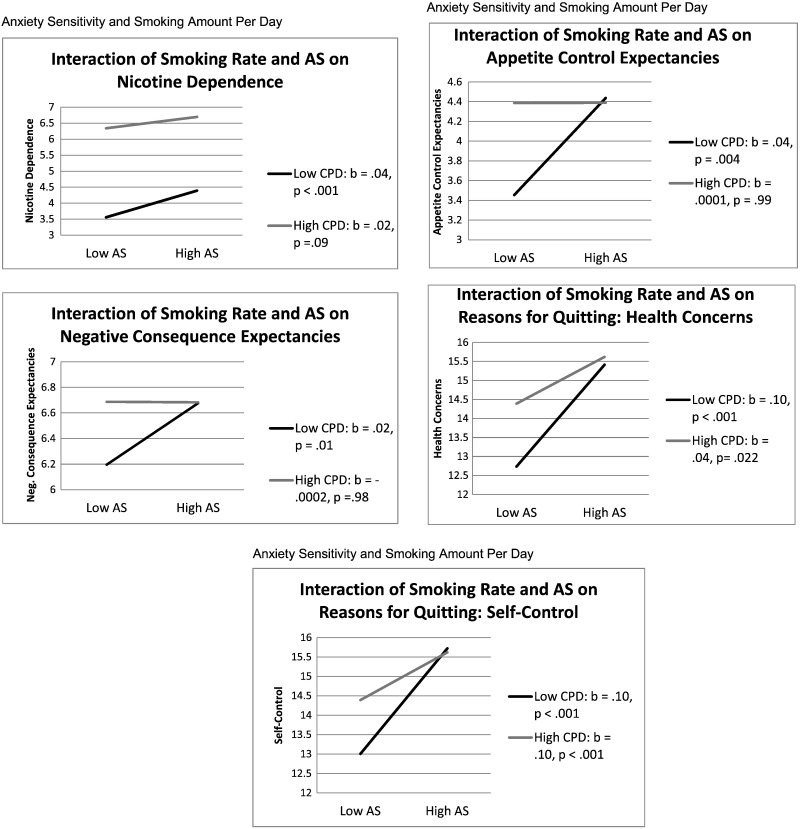

In terms of nicotine dependence, covariates entered at the first step accounted for a significant amount of variance (R2 = .04, F(10, 455) = 32.3, p < .01). Please refer to Table 1 for the significant covariate effects. At the second step, both smoking amount per day and anxiety sensitivity were significant predictors (b = .14, p < .001; b = .03, p < .01, respectively). The interaction term for anxiety sensitivity and smoking amount per day was significant (b = − .001, p < .05; Table 2). Simple slope analyses revealed that anxiety sensitivity predicted greater levels of nicotine dependence among lighter (versus heavier) smokers (b = .04, p < .001 and b = .02, p = .09 for lighter and heavier smokers respectively; see Fig. 1).

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard error | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine dependence | ||||

| Step 1. (R2 = .04, p < .01) | ||||

| Gendera | − .03 | .22 | − 1.17 | NS |

| Negative affectb | .02 | .02 | 1.07 | NS |

| AUDITc | − .06 | .02 | − 3.08 | < .01 |

| Medical problemsd | − .19 | .17 | − 1.13 | NS |

| Axis-I disordere | .65 | .24 | 2.74 | < .01 |

| Substance usef | − .30 | .37 | − .81 | NS |

| Step 2. (R2 = .36, p < 001) | ||||

| CPDa | 0.14 | .01 | 14.73 | < .001 |

| ASb | 0.03 | .01 | 3.23 | < .01 |

| Step 3. (R2 = .37, p < .001) | ||||

| AS × CPDc | − .001 | .001 | − 2.15 | < .05 |

| SCQ—neg. consequencesi | ||||

| Step 1. (R2 = .07, p < .001) | ||||

| Gendera | .39 | .12 | 3.25 | < .01 |

| Negative affectb | .03 | .01 | 3.58 | < .001 |

| AUDITc | .01 | .01 | 1.19 | NS |

| Medical problemsd | .05 | .09 | .51 | NS |

| Axis-I disordere | − .11 | .13 | − .81 | NS |

| Substance usef | − .41 | .21 | − 1.99 | < .05 |

| Step 2. (R2 = .08, p < .001) | ||||

| ASa | .01 | .01 | 1.46 | NS |

| CPDc | .01 | .01 | 1.62 | NS |

| Step 3. (R2 = .09, p < .001) | ||||

| AS × CPDc | − .001 | .00 | − 2.5 | < .05 |

| SCQ—neg. reinforcementi | ||||

| Step 1. (R2 = .18, p < .001) | ||||

| Gendera | .48 | .16 | 3.04 | < .01 |

| Negative affectb | .08 | .01 | 6.8 | < .001 |

| AUDITc | .02 | .01 | 1.85 | NS |

| Medical problemsd | − .32 | .12 | − 2.61 | < .01 |

| Axis-I disordere | .21 | .17 | 1.19 | NS |

| Substance usef | − .25 | .27 | − .92 | NS |

| Step 2. (R2 = .19, p < .001) | ||||

| ASa | .01 | .01 | 1.75 | NS |

| CPDb | .01 | .01 | 0.97 | NS |

| Step 3. (R2 = .19, p < .001) | ||||

| AS × CPDc | − .00007 | .00 | − 1.31 | NS |

| SCQ—appetite controli | ||||

| Step 1. (R2 = .07, p < .001) | ||||

| Gendera | 1.15 | .22 | 5.25 | < .001 |

| Negative affectb | .02 | .02 | 1.25 | NS |

| AUDITc | .00 | .02 | .23 | NS |

| Medical problemsd | − .04 | .17 | − .23 | NS |

| Axis-I disordere | .19 | .24 | .79 | NS |

| Substance usef | .15 | .38 | .39 | NS |

| Step 2. (R2 = .08, p < .001) | ||||

| ASa | .02 | .01 | 1.65 | NS |

| CPDb | .02 | .01 | 1.49 | NS |

| Step 3. (R2 = .10, p < .001) | ||||

| AS × CPDc | − .002 | .00 | − 2.76 | < .01 |

| RFQ—health concernsj | ||||

| Step 1. (R2 = .06, p < .001) | ||||

| Gendera | 1.08 | .36 | 3.01 | < .01 |

| Negative affectb | .05 | .03 | .15 | NS |

| AUDITc | .00 | .03 | .15 | NS |

| Medical problemsd | .92 | .28 | 3.25 | < .01 |

| Axis-I disordere | .24 | .40 | .60 | NS |

| Substance usef | − .99 | .62 | − 1.59 | NS |

| Step 2. (R2 = .11, p < .001) | ||||

| ASa | .08 | .02 | 4.17 | < .001 |

| CPDb | .04 | .02 | 2.18 | < .05 |

| Step 3. (R2 = .12, p < .001) | ||||

| AS × CPDc | − .003 | .001 | − 2.53 | < .05 |

| RFQ-Self-Control | ||||

| Step 1. (R2 = .03, p < .05) | ||||

| Gendera | .59 | .38 | 1.54 | NS |

| Negative affectb | − .00 | .03 | − .03 | NS |

| AUDITc | .01 | .03 | .34 | NS |

| Medical problemsd | .59 | .30 | 1.92 | = .06 |

| Axis-I disordere | .85 | .42 | 2.01 | < .05 |

| Substance usef | .01 | .66 | .01 | NS |

| Step 2. (R2 = .06, p < .001) | ||||

| ASa | .07 | .02 | 3.84 | < .001 |

| CPDb | .02 | .02 | 1.09 | NS |

| Step 3. (R2 = .07, p < .001) | ||||

| AS × CPDc | − .003 | .00 | − 2.58 | = .01 |

Note: aGender = % listed are females (coded 0 = male; 1 = female). bNA = Positive and Negative Affect Scale—Negative Affect subscale. cAUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test—total score. dMedical problems = tobacco-related medical illnesses per the Medical Screening Questionnaire. eAxis I Disorder = Current Axis I disorder per the Structured Clinical Interview—Non-Patient Version for DSM-IV. eSubstance use = current non-alcohol substance abuse/dependence diagnosis per the Structured Clinical Interview—Non-Patient Version for DSM-IV. fCPD = number of cigarettes per day during past week per the Smoking History Questionnaire. gAS = Anxiety Sensitivity Index-III—total score. hFTND = Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence. iSCQ negative consequences, iSCQ appetite control, iSCQ negative reinforcement = the subscales of Smoking Consequences Questionnaire. jRFQ health concerns and jRFQ self-control = the subscales of Reasons for Smoking Scale.

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Plotting the interactive effects of smoking amount per day (CPD) and anxiety sensitivity (AS) on nicotine dependence, outcome expectancies, and reasons for quitting. |

3.2.2. Smoking expectancies

In terms of negative consequences expectancies, covariates accounted for a significant amount of variance (R2 = .07, F(10, 455) = 5.4, p < .0001). Please refer to Table 1 for significant covariate effects. No significant effects emerged at the second step. The interaction term for anxiety sensitivity and smoking amount per day was significant (b = − .001, p < .05; Table 2). Simple slope analyses revealed that anxiety sensitivity predicted greater levels of negative consequences expectancies among lighter (versus heavier) smokers (b = .02, p = .01 and b = − .0002, p = .98 for lighter and heavier smokers respectively; see Fig. 1).

In terms of negative affect reduction expectancies, covariates entered at the first step accounted for a significant amount of variance (R2 = .09, F(10, 455) = 5.1, p < .0001). Please refer to Table 1 for significant covariate effects. There were no significant predictors at levels two or three in the model.

In terms of appetite control expectancies, covariates entered at the first step accounted for a significant amount of variance (R2 = .07, F(10, 455) = 6.2, p < .0001). Please refer to Table 1 for significant covariate effects. No significant effects were evident at the second step. The interaction term was significant (b = − .002, p < .01; Table 2). Simple slope analyses revealed that anxiety sensitivity predicted greater appetite control expectancies among lighter (versus heavier) smokers (b = .04, p = .004 and b = .0001, p = .99 for lighter and heavier smokers respectively; see Fig. 1).

3.2.3. Intrinsic reasons for quitting

In terms of reasons for quitting related to health concerns, covariates entered at the first step accounted for a significant amount of variance (R2 = .06, F(10, 455) = 4.2, p < .0001). Please refer to Table 1 for significant covariate effects. Anxiety sensitivity was the only significant predictor at step two (b = .04, p < .001). The interaction term for smoking amount per day was significant (b = − .003, p < .05; Table 2). Simple slope analyses revealed that anxiety sensitivity predicted reasons for quitting related to health concerns among both light and heavy smokers. However, in line with the significant interactive effect, the change slope was steeper among lighter (versus heavier) smokers (b = .10, p < .001 and b = .04, p = .022 for lighter and heavier smokers respectively; see Fig. 1).

In terms of reasons for quitting related to self-control, covariates entered at the first step accounted for a significant amount of variance (R2 = .02, F(10, 455) = 2.2, p < .05). Please refer to Table 1 for significant covariate effects. Anxiety sensitivity was the only significant predictor at step two (b = .07, p = .0001). The interaction term for smoking amount per day was significant (b = − .003, p = .01; see Table 2). Simple slope analyses revealed that anxiety sensitivity predicted reasons for quitting for self-control among both light and heavy smokers. However, in line with the significant interactive effect, the change slope was steeper among lighter (versus heavier) smokers (b = .10, p < .001 and b = .04, p = .046 for lighter and heavier smokers respectively; see Fig. 1).

4. Discussion

Although past work has indicated that anxiety sensitivity impacts numerous, clinically-significant aspects of smoking behavior (Leventhal & Zvolensky, 2015), research had not yet explored how this construct interplays with differing levels of smoking behavior. To address this gap, the current study explored whether smoking amount per day would moderate the effect of anxiety sensitivity in regard to nicotine dependence, smoking outcome expectancies, and (intrinsic) reasons for quitting among smokers with lower (versus higher) smoking amount per day.

Results were generally consistent with prediction. Namely, lower (versus higher) smoking amount per day moderated the relation between anxiety sensitivity and nicotine dependence, expectancies for negative consequences and appetite control as well as intrinsic reasons for quitting. In contrast to expectation, however, no moderating effect emerged for negative reinforcement/negative affect reduction. The lack of significant interaction for negative reinforcement expectancies may indicate that smoking amount per day is equally important across smokers with higher and lower anxiety sensitivity (i.e., the influence of the negative reinforcement mechanism may be stronger than that of smoking amount per day and anxiety sensitivity). The form of the significant interactions indicated across dependent variables lower levels of smoking amount per day suppressed the relation between anxiety sensitivity and smoking related dependent variable, such that the positive relation of anxiety sensitivity to smoking dependence and cognitive–affective aspects of smoking is weaker in heavier smokers and more robust in lighter smokers. Thus, although heavier versus lighter smokers are generally more at risk for tobacco addiction (e.g., Hatsukami, Stead, & Gupta, 2008), the present findings indicate that such main effects may be qualified by anxiety sensitivity.

Although not a primary aim of the investigation, anxiety sensitivity and smoking amount per day showed minimal relation to one another; only sharing approximately .01% overall variance. Such a finding is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Howell, Leyro, Hogan, Buckner, & Zvolensky, 2010) and suggests that they represent distinct biobehavioral processes influencing tobacco addiction.

The current study suggests that smoking amount per day may reduce certain processes that tap nicotine dependence and cognitive–affective aspects of smoking addiction at lower levels of anxiety sensitivity. Accordingly, ‘early intervention’ for smoking cessation may benefit by expanding assessment coverage to include anxiety sensitivity. Indeed, intervention efforts for smoking may benefit by assessing for, and intervening with, anxiety sensitivity. For example, there may be clinical utility to target reductions in anxiety sensitivity to improve cessation outcomes or decrease the severity of nicotine dependence by addressing this construct via psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and interoceptive exposure (Feldner et al., 2008; Zvolensky et al., 2014; Zvolensky, Lejuez, Kahler and Brown, 2003 ; Zvolensky et al., 2008).

There are a number of caveats to the present study. First, given the cross-sectional nature of these data, it is unknown whether smoking amount per day moderates the above-mentioned effects of anxiety sensitivity over time. Based upon the present results, future prospective studies are necessary to determine the directional effects of these relations. Second, our sample consisted of community-recruited, treatment-seeking daily cigarette smokers with moderate levels of nicotine dependence. Future studies may benefit by sampling from lighter and heavier smoking populations to ensure the generalizability of the results to the general smoking population. It also is noteworthy that the FTND internal consistency was relatively low, a common issue with this measure (Etter, Vu Duc, & Perneger, 1999), though Cronbach alpha values are fairly sensitive to the number of items in each scale and it is not uncommon to find lower Cronbach values with shorter scales (e.g., scales with < 10 items; DeVellis, 2003). Third, the current study relied solely on self-report measures to assess the examined predictor, moderator, and outcome variables. Future research could benefit by utilizing multi-method approaches and minimizing the role of method variance in the observed relations. For example, experimental provocation procedures such as emotion elicitation via biological challenge could be useful in examining the present relations in response to aversive interoceptive states elicited ‘in vivo.’ Finally, the sample was largely comprised of a relatively homogenous group of treatment-seeking smokers. To rule out a selection bias and increase the generalizability of these findings, it will be important for future studies to recruit a more ethnically/racially diverse sample of smokers.

Overall, the present study serves as an initial investigation into the interplay between anxiety sensitivity and smoking amount per day and a relatively wide range of smoking processes among adult treatment-seeking smokers. Specifically, there was generally consistent evidence that smoking amount per day suppressed the relation between anxiety sensitivity and smoking related dependent variable, such that the positive relation of anxiety sensitivity to smoking dependence and cognitive–affective aspects of smoking is weaker in heavier smokers and more robust in lighter smokers. Future work is needed to explore the extent to which anxiety sensitivity interplays with smoking amount per day in relation to other smoking processes (e.g., withdrawal, cessation outcome) to further clarify theoretical models of emotional vulnerability and smoking, and to inform clinical assessment and intervention development/refinement.

References

- Assayag et al., 2012 Y. Assayag, A. Bernstein, M.J. Zvolensky, D. Steeves, S.S. Stewart; Nature and role of change in anxiety sensitivity during NRTaided cognitive-behavioral smoking-cessation treatment; Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 41 (2012), pp. 51–62 https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2011.632437

- Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995 Y. Benjamini, Y. Hochberg; Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing; Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B: Methodological (1995), pp. 289–300

- Brandon and Baker, 1991 T.H. Brandon, T.B. Baker; The Smoking Consequences Questionnaire: The subjective expected utility of smoking in college students; Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 3 (3) (1991), pp. 484–491 https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.3.3.484

- Brown et al., 2001 R.A. Brown, C.W. Kahler, M.J. Zvolensky, C.W. Lejuez, S.E. Ramsey; Anxiety sensitivity: Relationship to negative affect smoking and smoking cessation in smokers with past major depressive disorder; Addictive Behaviors, 26 (2001), pp. 887–899 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00241-6

- Brown et al., 2002 R.A. Brown, C.W. Lejuez, C.W. Kahler, D.R. Strong; Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts; Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111 (2002), pp. 180–185 https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.111.1.180

- Buckley et al., 2005 T.C. Buckley, B.W. Kamholz, S.L. Mozley, S.B. Gulliver, D.R. Holohan, A.W. Helstrom, et al.; A psychometric evaluation of the Smoking Consequences Questionnaire--adult in smokers with psychiatric conditions; Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 7 (5) (2005), pp. 739–745 https://doi.org/10.1080/14622200500259788

- Comeau et al., 2001 N. Comeau, S.H. Stewart, P. Loba; The relations of trait anxiety, anxiety sensitivity, and sensation seeking to adolescents' motivations for alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use; Addictive Behaviors, 26 (2001), pp. 803–825 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00238-6

- Curry et al., 1995 S.J. Curry, C. McBride, L.C. Grothaus, D. Louie, E.H. Wagner; A randomized trial of self-help materials, personalized feedback, and telephone counseling with nonvolunteer smokers; Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63 (6) (1995), pp. 1005–1014 https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.63.6.1005

- Curry et al., 1990 S. Curry, E.H. Wagner, L.C. Grothaus; Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for smoking cessation; Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 58 (3) (1990), pp. 310–316 https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.58.3.310

- DeVellis, 2003 R.F. DeVellis; Scale development: Theory and application; (2nd ed.)Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA (2003)

- Downey and Kilbey, 1995 K.K. Downey, M.M. Kilbey; Relationship between nicotine and alcohol expectancies and substance dependence; Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 3 (2) (1995), pp. 174–182 https://doi.org/10.1037/1064-1297.3.2.174

- Etter et al., 1999 J. Etter, T. Vu Duc, T.V. Perneger; Validity of the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence and of the Heaviness of Smoking Index among relatively light smokers; Addiction, 94 (2) (1999), pp. 269–281 https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94226910.x

- Feldner et al., 2008 M.T. Feldner, M.J. Zvolensky, K. Babson, E.W. Leen-Feldner, N.B. Schmidt; An integrated approach to panic prevention targeting the empirically supported risk factors of smoking and anxiety sensitivity: Theoretical basis and evidence from a pilot project evaluating feasibility and short-term efficacy; Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22 (7) (2008), pp. 1227–1243 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.01.005

- First et al., 2007 M.B. First, R.L. Spitzer, M. Gibbon, J.B.W. Williams; Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders: research (nonpatient ed.; SCIDI/NP); Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY (2007)

- Hatsukami et al., 2008 D.K. Hatsukami, L.F. Stead, P.C. Gupta; Tobacco addiction; The Lancet, 371 (9629) (2008), pp. 2027–2038 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60871-5

- Hayward et al., 2000 C. Hayward, J.D. Killen, H.C. Kraemer, C.B. Taylor; Predictors of panic attacks in adolescents; Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39 (2000), pp. 207–214 https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200002000-00021

- Heatherton et al., 1991 T.F. Heatherton, L.T. Kozlowski, R.C. Frecker, K.O. Fagerström; The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire; British Journal of Addiction, 86 (1991), pp. 1119–1127 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x

- Howell et al., 2010 A.N. Howell, T.M. Leyro, J. Hogan, J.D. Buckner, M.J. Zvolensky; Anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, and discomfort intolerance in relation to coping and conformity motives for alcohol use and alcohol use problems among young adult drinkers; Addictive Behaviors, 35 (12) (2010), pp. 1144–1147 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.003

- Jarvis et al., 2014 M.J. Jarvis, G.A. Giovino, R.J. O’Connor, L.T. Kozlowski, J.T. Bernert; Variation in nicotine intake among U.S. cigarette smokers during the past 25 years; Evidence from NHANES surveys (2014)

- Johnson et al., 2013 K.A. Johnson, S.G. Farris, N.B. Schmidt, J.A. Smits, M.J. Zvolensky; Panic attack history and anxiety sensitivity in relation to cognitive-based smoking processes among treatment-seeking daily smokers; Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15 (2013), pp. 1–10 https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr332

- Johnson et al., 2012 K.A. Johnson, S. Stewart, D. Rosenfield, D. Steeves, M.J. Zvolensky; Prospective evaluation of the effects of anxiety sensitivity and state anxiety in predicting acute nicotine withdrawal symptoms during smoking cessation; Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26 (2012), pp. 289–297 https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024133

- Kessler et al., 2005 R.C. Kessler, W.T. Chiu, O. Demler, E.E. Walters; Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication; Archives of General Psychiatry, 62 (6) (2005), pp. 617–627 https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

- Korte et al., 2013 K.J. Korte, D.W. Capron, M. Zvolensky, N.B. Schmidt; The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: Do revisions in the item scoring enhance the psychometric properties?; Addictive Behaviors, 38 (3) (2013), pp. 1757–1763 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.10.013

- Langdon et al., 2013 K.J. Langdon, A.M. Leventhal, S. Stewart, D. Rosenfield, D. Steeves, M.J. Zvolensky; Anhedonia and anxiety sensitivity: Prospective relationships to nicotine withdrawal symptoms during smoking cessation; Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 74 (2013), pp. 469–478 https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024133

- Lasser et al., 2000 K. Lasser, J.W. Boyd, S. Woolhandler, D.U. Himmelstein, D. McCormick, D.H. Bor; Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study; JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, 284 (20) (2000), pp. 2606–2610 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.20.2606

- Leen-Feldner et al., 2007 E.W. Leen-Feldner, M.J. Zvolensky, J. van Lent, A.A. Vujanovic, T. Bleau, A. Bernstein, et al.; Anxiety sensitivity moderates relations among tobacco smoking, panic attack symptoms, and bodily complaints in adolescents; Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29 (2) (2007), pp. 69–79 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-006-9028-7

- Leventhal and Zvolensky, 2015 A.M. Leventhal, M.J. Zvolensky; Anxiety, depression, and cigarette smoking: A transdiagnostic vulnerability framework to understanding emotion-smoking comorbidity; Psychological Bulletin, 141 (2015), pp. 176–212

- Leyro et al., 2008 T.M. Leyro, M.J. Zvolensky, A.A. Vujanovic, A. Bernstein; Anxiety sensitivity and smoking motives and outcome expectancies among adult daily smokers: Replication and extension; Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 10 (6) (2008), pp. 985–994 https://doi.org/10.1080/14622200802097555

- Maller and Reiss, 1992 R.G. Maller, S. Reiss; Anxiety sensitivity in 1984 and panic attacks in 1987; Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 6 (3) (1992), pp. 241–247 https://doi.org/10.1016/0887-6185(92)90036-7

- Marshall et al., 2009 E.C. Marshall, K. Johnson, J. Bergman, L.E. Gibson, M.J. Zvolensky; Anxiety sensitivity and panic reactivity to bodily sensations: Relation to quit-day (acute) nicotine withdrawal symptom severity among daily smokers making a self-guided quit attempt; Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 17 (2009), pp. 356–364 https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016883

- Marshall et al., 2010 G.N. Marshall, J.V. Miles, S.H. Stewart; Anxiety sensitivity and PTSD symptom severity are reciprocally related: Evidence from a longitudinal study of physical trauma survivors; Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119 (2010), pp. 143–150 https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018009

- McCabe et al., 2004 R.E. McCabe, S.M. Chudzik, M.M. Antony, L. Young, R.P. Swinson, M.J. Zolvensky; Smoking behaviors across anxiety disorders; Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 18 (1) (2004), pp. 7–18 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.07.003

- McLeish et al., 2007 A.C. McLeish, M.J. Zvolensky, M.M. Bucossi; Interaction between smoking rate and anxiety sensitivity: Relation to anticipatory anxiety and panic-relevant avoidance among daily smokers; Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21 (6) (2007), pp. 849–859 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.11.003

- McLeish et al., 2009 A.C. McLeish, M.J. Zvolensky, K.S. Del Ben, R.S. Burke; Anxiety sensitivity as a moderator of the association between smoking rate and panic-relevant symptoms among a community sample of middle-aged adult daily smokers; The American Journal on Addictions, 18 (1) (2009), pp. 93–99 https://doi.org/10.1080/10550490802408985

- McNally, 2002 R.J. McNally; Anxiety sensitivity and panic disorder; Biological Psychiatry, 52 (2002), pp. 938–946 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01475-0

- Novak et al., 2003 A. Novak, E.S. Burgess, M. Clark, M.J. Zvolensky, R.A. Brown; Anxiety sensitivity, self-reported motives for alcohol and nicotine use and level of consumption; Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 17 (2) (2003), pp. 165–180 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6185(02)00175-5

- Payne et al., 1994 T.J. Payne, P.O. Smith, L.M. McCracken, W.C. McSherry, M.M. Antony; Assessing nicotine dependence: A comparison of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire (FTQ) with the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) in a clinical sample; Addictive Behaviors, 19 (3) (1994), pp. 307–317 https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(94)90032-9

- Pomerleau et al., 1994 C.S. Pomerleau, S.M. Carton, M.L. Lutzke, K.A. Flessland, O.F. Pomerleau; Reliability of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire and the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence; Addictive Behaviors, 19 (1994), pp. 33–39 https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(94)90049-3

- Reiss and McNally, 1985 S. Reiss, R.J. McNally; Expectancy model of fear; S. Reiss, R.R. Bootzin (Eds.), Theoretical issues in behavior therapy, Academic Press, San Diego, CA (1985), pp. 107–121

- Reiss et al., 1986 S. Reiss, R.A. Peterson, M. Gursky, R.J. McNally; Anxiety, sensitivity, anxiety frequency, and the prediction of fearfulness; Behaviour Research and Therapy, 24 (1986), pp. 1–8 https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(86) 90143-9

- Saunders et al., 1993 J.B. Saunders, O.G. Aasland, T.F. Babor, J.R. de la Fuente, M. Grant; Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption‐II; Addiction, 88 (6) (1993), pp. 791–804

- Schmidt et al., 1999 N.B. Schmidt, D.R. Lerew, R.J. Jackson; Prospective evaluation of anxiety sensitivity in the pathogenesis of panic: Replication and extension; Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108 (3) (1999), pp. 532–537 https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.108.3.532

- Schmidt et al., 2006 N.B. Schmidt, M.J. Zvolensky, J.K. Maner; Anxiety sensitivity: Prospective prediction of panic attacks and Axis I pathology; Journal of Psychiatric Research, 40 (8) (2006), pp. 691–699 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.009

- Taylor, 2003 S. Taylor; Anxiety sensitivity and its implications for understanding and treating PTSD; Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 17 (2003), pp. 179–186 https://doi.org/10.1891/jcop.17.2.179.57431

- Taylor et al., 2007 S. Taylor, M.J. Zvolensky, B.J. Cox, B. Deacon, R.G. Heimberg, D.R. Ledley, et al.; Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: Development and initial validation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3; Psychological Assessment, 19 (2007), pp. 176–188 https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.176

- Vujanovic and Zvolensky, 2009 A.A. Vujanovic, M.J. Zvolensky; Anxiety sensitivity, acute nicotine withdrawal symptoms, and anxious and fearful responding to bodily sensations: A laboratory test; Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 17 (3) (2009), pp. 181–190 https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016266

- Watson et al., 1988 D. Watson, L.A. Clark, A. Tellegen; Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales; Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54 (1988), pp. 1063–1070 https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Wong et al., 2013 M. Wong, A. Krajisnik, L. Truong, N.E. Lisha, M. Trujillo, J.B. Greenberg, et al.; Anxiety sensitivity as a predictor of acute subjective effects of smoking; Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15 (2013), pp. 1084–1090 https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nts208

- Zvolensky and Bernstein, 2005 M.J. Zvolensky, A. Bernstein; Cigarette smoking and panic psychopathology; Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14 (6) (2005), pp. 301–305 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00386.x

- Zvolensky, Bernstein, et al., 2007 M.J. Zvolensky, A. Bernstein, S.J. Cardenas, V.A. Colotla, E.C. Marshall, M.T. Feldner; Anxiety sensitivity and early relapse to smoking: A test among Mexican daily, low-level smokers; Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 9 (4) (2007), pp. 483–491 https://doi.org/10.1080/14622200701239621

- Zvolensky et al., 2014 M.J. Zvolensky, D. Bogiaizian, P.L. Salazar, S.G. Farris, J. Bakhshaie; An anxiety sensitivity reduction smoking-cessation program for Spanish-speaking smokers (Argentina); Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 21 (3) (2014), pp. 350–363 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.10.005

- Zvolensky et al., 2006 M.J. Zvolensky, M. Bonn-Miller, A. Bernstein, E. Marshall; Anxiety sensitivity and abstinence duration to smoking; Journal of Mental Health, 15 (2006), pp. 659–670 https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230600998888

- Zvolensky et al., 2014 M.J. Zvolensky, S.G. Farris, A.M. Leventhal, N.B. Schmidt; Anxiety sensitivity mediates relations between emotional disorders and smoking; (2014)

- Zvolensky, Kotov, Antipova and Schmidt, 2003 M.J. Zvolensky, R. Kotov, A.V. Antipova, N.B. Schmidt; Cross cultural evaluation of smokers risk for panic and anxiety pathology: A test in a Russian epidemiological sample; Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41 (10) (2003), pp. 1199–1215

- Zvolensky, Lejuez, Kahler and Brown, 2003 M.J. Zvolensky, C.W. Lejuez, C.W. Kahler, R.A. Brown; Integrating an interoceptive exposure-based smoking cessation program into the cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic disorder: Theoretical relevance and case demonstration; Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 10 (4) (2003), pp. 347–357 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1077-7229(03)80052-4

- Zvolensky, Lejuez, Kahler and Brown, 2004 M.J. Zvolensky, C.W. Lejuez, C.W. Kahler, R.A. Brown; Nonclinical panic attack history and smoking cessation: An initial examination; Addictive Behaviors, 29 (4) (2004), pp. 825–830 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.017

- Zvolensky et al., 2009 M.J. Zvolensky, S.H. Stewart, A.A. Vujanovic, D. Gavric, D. Steeves; Anxiety sensitivity and anxiety and depressive symptoms in the prediction of early smoking lapse and relapse during smoking cessation treatment; Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 11 (2009), pp. 323–331 https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntn037

- Zvolensky, Vujanovic, et al., 2007 M.J. Zvolensky, A.A. Vujanovic, M. Miller, A. Bernstein, A.R. Yartz, K.L. Gregor, et al.; Incremental validity of anxiety sensitivity in terms of motivation to quit, reasons for quitting, and barriers to quitting among community-recruited daily smokers; Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 9 (9) (2007), pp. 965–975 https://doi.org/10.1080/14622200701540812

- Zvolensky et al., 2008 M.J. Zvolensky, A.R. Yartz, K. Gregor, A. Gonzalez, A. Bernstein; Interoceptive exposure-based cessation intervention for smokers high in anxiety sensitivity: A case series; Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 22 (4) (2008), pp. 346–365 https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.22.4.346

Notes

1. In order to ensure that the primary associations are not due to suppression or other effects of the covariates, a separate set of analyses were run in which the covariates were entered as a block in the final step of the regression analyses. Our analyses remained the same using this alternative post hoc method.

Document information

Published on 26/05/17

Submitted on 26/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?