Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Violent behaviors cause concern among people, policy makers, politicians, educators, social workers, parents associations, etc. From different fields and perspectives, measures are taken to try to solve the problem of violence. Institutional communication campaigns against violence and the publication of news related to violent events are often some of the actions used by policy makers. But some of the literature and data have shown that its effectiveness is not always exactly as expected. And even some anti-violence messages, can have the opposite effect and reinforce the attitudes of those who thought that violence is necessary. The hypothesis is that most people assume with no problem the core message of anti-violence campaigns. But, and this is the key issue and most problematic, individuals who are more likely to be violent (precisely those who should address such communications) could react to anti-violence message in a violent way. There is a tragic paradox: the anti-violence message could increase the predisposition to violent behavior. This would be a case of what some literature called boomerang effect. This article highlights the need for detailed empirical studies on certain effects of media (desensitization, imitation, accessibility and reactance), which could help explain the emergence of the boomerang effect.

1. Introduction. Violence as a social problem

Today violent behavior is one of the problems that most concerns society as a whole. Numerous public institutions and diverse social-action organizations (NGOs, Anti-violence associations, etc.) have begun to implement different initiatives to eradicate or at least minimize violent conduct as much as possible.

In this article we concentrate on those initiatives that focus on awareness and sensitization campaigns against violence in order to consider the extent to which these measures are effective and explain why they may be failing. We begin with two proven facts: a) an important communicative effort is being made against violence, but at the same time, b) the data suggest that this effort is not generating the desired results.

The evidence that an important dissemination effort is underway is that the anti-violence awareness campaigns have required a significant economic investment over the last several years. For example, according to the Spanish Ministry of Equality, in 2008 the state-funded campaign against gender violence Ante el maltratador, tolerancia cero cost 4 million euros to fund.

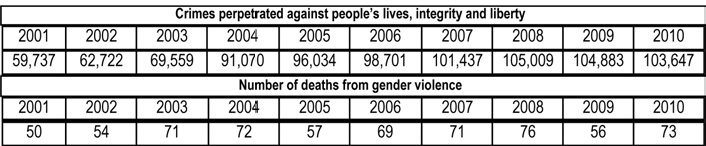

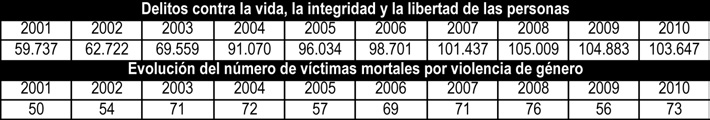

Nevertheless, the desired results have not yet been achieved. Despite the existence of these awareness campaigns, violent behavior has not decreased, with some of the indicators reflecting truly alarming statistics. For example, in the last decade, the total number of violent crimes has experienced a significant increase:

Meanwhile, the statistics of victims of gender violence in Spain during the last decade also show a similar worrying trend despite the fact that now is precisely when more measures are being put into place to eradicate this serious social problem1.

Therefore, the question that needs asking is: What is going wrong? Although it is evident that social phenomenon can result from diverse causes, one of the possible reasons may be the clearly limited effectiveness of the campaigns designed to sensitize the population against the use of violence. This would explain why the statistics on the occurrence of violence remain unchanged, or do not show a significant decrease. How can one explain that the number of violent acts increase after awareness campaigns? In this case, we are not only talking about the ineffectiveness of these campaigns, but also of a much more relevant and problematic issue: the possibility that an unforeseen perverse effect is being generated. Our hypothesis is that although the majority of people take on the anti-violence message as their own, there is a reduced number of individuals with a higher propensity towards violence that may react to these messages in a very undesirable way, in that the campaign’s message may cause a higher predisposition in them for developing violent behavior; resulting in what some literature calls the boomerang effect.

.In this context, critical reflection is needed to determine the social consequences of anti-violence awareness campaigns and identify the causes behind their apparent failure, and at the same time allow us to find the key to developing new campaigns that would be more effective against all types of violence. Several lines of reasoning can aid in explaining the problem. In this article, we will discuss some of them in detail.

2. The root of the problem

When designing an awareness campaign, one of the first steps to follow is to determine to whom the message is directed, who our target audience is. This means that the characteristics of the intended recipient of the campaign may be quite diverse and in the case of sensitization campaigns against violence, it may be especially important to keep in mind that some people are more prone to violent behavior and that their exposure to the campaign could generate different responses in them than those expected.

According to data from a 2008 survey on the use of cellular phones among minors, a sample from the Autonomous Region of Madrid of 1053 minors between 10 and 16 years of age demonstrates that roughly 10% of the child and young adult population are particularly prone to violent behavior (García Galera & al., 2008). The results of this study reveal that these young people confess their desire to record the hooliganism of others, show indifference to or enjoy watching violence posted on the Internet, and even on occasion have used their cellular phones to film fights, humiliating or violent acts (for example, pranks played on professors) or have posted these recordings on the Internet (YouTube, MySpace).

This is clearly alarming data, and presents us with a phenomenon that is quantitatively and qualitatively relevant to social coexistence. We are witnessing a scenario in which certain youths demonstrate an elevated degree of insensitivity and tolerance toward certain acts of violence, which they not only enable, but on occasion sometimes participate in. In our opinion, this data should be considered when designing anti-violence campaigns that aim to sensitize this target audience that unquestionably is the intended recipient of the message.

3. The risk of the boomerang effect in awareness campaigns: Empirical evidence

If, as mentioned above, the main institutional strategy used to combat undesired social behavior consists of the dissemination of awareness campaigns aimed at sensitizing the population with respect to different social and public health problems (abuse of alcohol, tobacco or other drugs), it has been demonstrated that in certain circumstances, these campaigns could be generating an effect contrary to the intended one. In fact, it would appear that it may be precisely the very target audience of these campaigns (alcoholics, smokers or drug-addicts) who are more prone to reject or experience the boomerang effect from the institutional message.

In this respect, in a variety of fields where institutional campaigns are used to warn about the risks of developing certain behaviors, an abundance of empirical evidence is being gathered on the boomerang effect. Of special significance are the following: campaigns that stress the risks of smoking (Hyland & Birrell, 1979; Robinson & Killen, 1997; Unger & al., 1999); campaigns against drug use (Feingold & Knapp, 1997); or those that focus on alcohol consumption (Ringold, 2002).

In the field of violence, there is a limited corpus of investigations, although one could cite studies such as the one by Bushman and Stack (1996) in which they reveal how the use of labels that alert about the broadcasting of programs with violent content could increase the audience’s interest for viewing the programs. If, as it has been demonstrated, a relationship exists between the exposure to violent content and the subsequent impulses and acts of violence, the problem would be that the use of these labels leads to a higher consumption of measured violence, and as a consequence, a higher level of real violence.

4. The risk of the boomerang effect in anti-violence awareness campaigns

4.1. An explanation based on the proven media effects

There is a long tradition of in depth studies done on media effects2. Some of these effects have contrasted empirical evidence, such as the ample consensus in the scientific community on the relationship that exists between the consumption of audiovisual violence and the tendency to develop violent behavior in the child and young adult population3. In fact, a number of studies have achieved significant results when correlating the exposure to violent content in the media (mainly on television and in video games) with the generation of violent thoughts, attitudes, and behavior. These effects have been demonstrated for the short, medium and long term. Relevant conclusions have been made for both men and women, and equally significant results have been obtained in a variety of situations studied in different countries. Among others, we can cite the studies by Huesmann and Moise (1996), Anderson (1997), Anderson and Dill (2000), Anderson and Bushman (2002), Huesmann & al. (2003), Anderson & al. (2003), Gentile & al. (2004), and Huesmann and Taylor (2006).

In order to demonstrate the influence that the consumption of audiovisual violence may have on the generation of violent behavior, different mechanisms are used; among which the desensitization effect and the imitation effect stand out. The former allows us to explain why the anti-violence campaigns are ineffective in reducing the number of violent acts; while the latter could explain not only why the campaigns are not effective, but also why sometimes these campaigns generate an effect contrary to the one desired by increasing the probability that violent acts take place.

4.1.1. Desensitization effect

Although it is true that the exposure to violent content initially produces a rejection response, it is also true that repeated exposure to violence ends up creating a process of decreased response or habituation. When presented with successive violent images, the spectator tends to show progressively smaller psychological and emotional responses. A state of emotional desensitization can be reached in which there are no emotional responses to stimuli that when viewed for the first time caused a strong response. Similarly, a cognitive desensitization is produced when violence is no longer considered as something infrequent or abnormal and begins to be viewed as an inevitable and normal aspect of daily life. Both emotional and cognitive desensitization can influence behavior, resulting in either a decrease in the probability that the desensitized person is critical of violent conduct or an increase in the probability that desensitized people develop aggressive conduct, which in turn may be more intense (Drabman & Thomas, 1974; Drabman & Thomas, 1976; Thomas & al., 1977; Molitor & Hirsch, 1994; Carnagey, Anderson & Bushman, 2006).

The desensitization effect has also been studied in investigations on the effectiveness of warning labels on certain products that may be harmful to a person’s health or security. In these studies, the repeated exposure to warning labels of all types (food, road safety, etc.) is found to be a contributing factor when people stop paying attention to them, even leading them to ignore many of them altogether (Twerski & al., 1976). This is especially true in those cases in which the harmful consequences do not immediately arise after engaging in the risky behavior, leading us to what Breznitz (1984) calls false alarms. An example of this would be the messages warning of the risks associated with smoking: while in the opinion of this author it is evident that drinking bleach has an immediate adverse effect, smoking a cigarette does not appear to have any, which makes the warning labels on cigarette packs less effective.

When applying this reasoning to the question of violence, it may be that some especially violent people feel a type of immunity effect regarding their actions, since the immediate consequences for the aggressor of a violent action (for example the prison sentences associated) are seldom discussed. Violent people who consider violence to be a normal part of daily life (cognitive desensitization) may believe (the same as some smokers) that their violent conduct will not result in any negative consequences for them.

Although the desensitization effect may not necessarily be related to the appearance of a boomerang effect, it is important to highlight that the greater the desensitization the person experiences towards violence, the less efficient the anti-violence awareness campaigns will be. Furthermore, if a person’s level of desensitization impedes them from reacting to real-life violence it is unlikely that the anti-violence messages (that usually deliberately avoid using damaging images) will have any effect on them.

4.1.2. Imitation effect

A social creature by nature, the human being learns to repeat or imitate behavior that is apparently valid or common by observing the other members of its community. Because of this, one of the most characteristic effects associated with the media is known precisely as the imitation effect. In the context of anti-violence awareness campaigns, this effect is produced solely in the case of messages that contain violence: news stories that contain explicit violence or campaigns that use images with violent content.

This imitation effect can be produced through two different mechanisms, both possibly resulting in an undesirable boomerang effect. They can be observed through increased violent conduct immediately following an awareness campaign or media piece containing violence:

a) Instrumental validity: the spectator imitates the behavior they view because they deduce that it is useful, since the person who has carried out the action has obtained something beneficial by behaving a certain way. In particular, in the context of violence, studies exist that demonstrate how children and adolescents not only tend to imitate the behavior of those people they interact with most frequently (family members, parents, etc.) but also media personalities. Along these lines, classic studies not only show that children imitate aggressive conduct exhibited by adult role models (Bandura & al., 1961), but that they also imitate the conduct of fictional characters (Bandura & al., 1963a). This is especially true when the imitated action is seen to have a reward (instrumental learning) or when the role model is admired or identified with. Therefore, one can deduce from this that if the awareness campaigns contain violence, they could generate more violence by imitation. Or in other words, it would be preferable that awareness campaigns and news stories on violence avoid displaying violent content in order to avoid the imitation effect.

b) Social validity: the spectator imitates a conduct that they perceive many people to be carrying out, and therefore, they presume that it must be correct behavior. Numerous studies show how people tend to behave the same way other people do since the fact that other people behave a certain way is interpreted as a validating factor about the appropriateness of the behavior (Gould & Shaffer, 1986; Reingen, 1982). This is a factor to consider when designing anti-violence awareness campaigns. Recent studies have shown that when trying to eradicate an undesirable behavior (for example violent behavior) a message that states that unfortunately many people still behave in a certain way may have the exact opposite effect since may of the campaigns focus the public’s attention (especially those with higher tendency towards the behaviors in question) more on the prevalence of the action, providing it with more visibility, than the undesirability of the action (Cialdini, 2003; Cialdini & al., 2006; Shulz & al., 2007). Along these lines, recent studies (Vives, Torrubiano and Álvarez, 2009) have brought to light that television news reports on gender violence have a negative influence on the number of deaths attributed to male violence.

4.2. Other mechanisms that could explain the boomerang effect

In addition to the aforementioned documented media effects, we deem appropriate the mention of two mechanisms that could explain the emergence of the boomerang effect after the dissemination of anti-violence awareness and sensitization campaigns: enhanced accessibility and psychological reactance.

4.2.1. Enhanced accessibility

As we have already suggested, the use of images with violent content in anti-violence messages could increase the probability that violent behavior is reproduced in the future. We believe that a new alternative explanation is possible, based on the fact that the exposure to these images could cause these violent behaviors to be more accessible to the recipients’ minds. Taking it a step further, accessibility (the ease or speed that a construct or concept comes to mind) could also help to explain the possible perverse effect of anti-violence awareness campaigns even when they do not contain violent content. In line with previous investigations that found that the attempt to eliminate certain thoughts can make them even more accessible (Wegner, 1994), a hypothesis could be made that the mass media’s use of messages that refer to violence (even when the ultimate purpose is to criticize it) can have a negative effect by activating and increasing accessibility to violent thoughts and ideas, especially for those individuals already particularly prone to violence.

4.2.2. Psychological reactance

Psychological reactance has been defined as the state of psychological stimulation that arises when our freedom appears to us to be limited or threatened (Brehm and Brehm, 1981). The most direct consequence of this state is a tendency to resist everything that could be considered as a threat to one’s personal liberty (Brehm, 1966). Therefore, in the same way that we tend to show reactance when, for example, we are told how to think or we are given orders, we tend to experience reactance when certain behaviors are forbidden (Dillard & Shen, 2005; Miller & al., 2006; Miller & al., 2007). This means that those people who behave in a way that is criticized by the authorities reaffirm their actions as being a defense against a threat to their way of life.

This is also the same motive that leads people to more intensely desire information that has been censored (Worchel & Arnold, 1973). The explanation is found in the need that some people feel to engage in risky or taboo behavior, or to violate societal norms. Stewart and Martin (1994) believe that the warning messages about the risks associated with certain behaviors attract the attention of some people, impelling them to behave in the manner that was trying to be prevented. It is like eating the forbidden fruit (Bushman & Stack, 1996).

As a result, many researchers have identified psychological reactance as one of the main factors for explaining the boomerang effect caused by different media campaigns (Bushman & Stack, 1996; Ringold, 2002; Hornik & al., 2008). From our perspective, this could also apply to the anti-violence campaigns that generate a boomerang effect when individuals who are more prone to violence or who routinely use violence in their daily lives come into contact with campaigns that prohibit or criticize violence.

5. Conclusions

The need to consider the effects of desensitization, imitation, accessibility and psychological reactance in the awareness campaigns and information dissemination on violence. In summary, the difficulties of ending violent behavior could be related to the lack of adaptation between the objectives proposed by those responsible for social policy (such as the eradication of all violent conduct) and the communication strategies used (such as the anti-violence awareness and sensitization campaigns in the media).

Our aim here is not to assert that the messages about violence in the media or in certain institutional awareness campaigns are the only causes of violence, but rather to point out that not all of the well-meaning institutional campaigns or anti-violence information reach their goal of preventing violence, and that these initiatives could result in harmful effects (the boomerang effect) just as in other areas (for example, the case of drug consumption).

It is our belief, therefore, that in order to avoid generating any negative effects, the different risks shown in the studies on media effects should be taken into account when designing any anti-violence awareness campaigns or portraying violence in the news.

A two-fold proposal for reaching this goal would necessitate on the one hand that the existing studies on desensitization be consulted. Although at first the existence of information and campaigns may have had a positive effect towards the eradication of violence, the reiteration of those messages may have led to the desensitization of the recipients, thus suggesting the possible ineffectiveness of the messages being disseminated.

On the second hand, it should be kept in mind that an imitation effect is possibly being generated, which is even more worrying. If this is the case, not only do we have useless campaigns, but also the risk that the messages about violence or those containing violence may actually cause violent behavior. The imitation effect has abundant empirical evidence supporting it, and therefore institutional awareness campaigns generally keep it in mind. The information disseminated through the media presents a bigger problem since it does not always comply with these standards (Vives, Torrubiano & Álvarez, 2009).

Finally, the risk that the messages against violence are not fulfilling their objectives could also be related to two especially relevant psychological effects. On one hand, the research on construct accessibility show that any message about violence, even those whose aim is to combat it, can cause the concept of violence to be more present in people’s thoughts. On the other hand, studies on reactance beg us to consider the tendency for certain people to position themselves against any message that may threaten their freedom or self-esteem.

At the same time, it is important to add that in the case of the messages designed to combat violence these effects could intensify in those individuals that are particularly prone to developing violent conduct. This is especially worrying since those who are more prone to developing violent conduct are the target audience for anti-violence messages.

This suggests that inefficient strategies are being implemented, or what is worse, we may be increasing the probability that violent behavior occurs after the dissemination of informative or sensitization messages.

As a result, the theoretical reflection and bibliographical review that we have carried out shows the need for a more exhaustive study to be conducted on phenomenon such as desensitization, imitation, enhanced accessibility, and psychological reactance, in order to create a more efficient design for future anti-violence communication campaigns. Specifically, it is particularly necessary that empirical research be developed that would allow for the experimental verification of the hypothesis proposed in this paper.

Notes

1 In 2004 the Ministry of Equality was created (incorporated in October 2010 as Secretary General of the new Ministry of Health, Social Policy and Equality) that has implemented diverse measures of prevention, sensitization and action such as the Ley Integral contra la Violencia de Género (L.O. 1/2004) (Law on Integral Protection Measures against Gender Violence), awareness campaigns, pedagogical activities, and a personal attention telephone line, etc.

2 Due to the abundance of publications on media effects, several texts have tried to systematize published information of the research on the effects. Among the classics, the work by authors McQuail (1991) or Wolf (1994) stands out. At the same time, a background in the research in Spanish is had by consulting the work by Brändle, Martín Cárdaba, and Ruiz San Roman (2009); Igartua & al. (2001); Fernández Villanueva & al. (2008); Cohen (1998); and Barrios (2005).

3 The recent elaboration of a text presented to the Supreme Court in the United States by the American Psychological Association (APA) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) that warned of the proven relationship that exists between the use of violent video games and the subsequent aggressive conduct displayed by children and adolescents (see American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009) is evidence of the consensus among the scientific community.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics (2009). Pediatrics. (www.pediatrics.org) (15-12-2010).

Anderson, C.A. & Bushman, B. J. (2002). The Effects of Media Violence on Society. Science, 295; 2.377-2.378.

Anderson, C.A. & Dill, K.E. (2000). Video Games and Aggressive Thoughts, Feelings, and Behavior in the La-boratory and in Life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(4; 772-790.

Anderson, C.A. (1997). Effects of Violent Movies and Trait Hostility on Hostile Feelings and Aggressive Thoughts. Aggressive Behavior, 23; 161-178.

Anderson, C.A.; Berkowitz, L. & al. (2003). The Influence of Media Violence on Youth. American Psychological Society, 4(3); 81-110.

Bandura, A., Ross, S. & Ross, S. A. (1963b). Vicarious Reinforcement and Imitative Learning. Journal of Ab-normal and Social Psychology, 67(6); 601-607.

Bandura, A., Ross, S. & Ross, S.A. (1961). Transmission of Aggression through Imitation of Aggressive Models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63(3); 575-582.

Bandura, A.; Ross, S. & Ross, S.A. (1963a). Imitation of Film-mediated Aggressive Models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66(1); 3-11.

Barrios Cachazo, C. (2005). La violencia audiovisual y sus efectos evolutivos: un estudio teórico y empírico.

Brehm, J.W (1966). A Theory of Psychological Reactance. New York: Academic Press.

Brehm, S.S. & Brehm, J.W. (1981). Psychological Reactance: A Theory of Freedom and Control. Academic Press: New York.

Breznitz, S. (1984). Cry Wolf: The Psychology of False Alarms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum & Associates.

Brändle, G.; Martín Cárdaba, M.A. & Ruiz San Román, J.A. (2009). El riesgo de efectos no queridos en cam-pañas de comunicación contra la violencia. Discusión de una hipótesis de trabajo, en Nova, P.; Del Pino, J. (Eds.). Sociedad y tecnología: ¿qué futuro nos espera? Madrid: Asociación Madrileña de Sociología; 191-198.

Bushman, B.J. & Stack, A.D. (1996). Forbidden fruit versus tainted fruit: effects of warnings labels on attraction to television violence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 2; 207-226.

Carnagey, N.L.; Anderson, C.A. & Bushman, B.J. (2007). The Effect of Videogame Violence on Psychological Desensitization to Real-life Violence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43; 489-496.

Cialdini, R.B. (2003). Crafting Normative Messages to Protect the Environment. Current Directions in Psycho-logical Science, 12; 105-109.

Cialdini, R.B.; Demaine, L.J. & al. (2006). Managing Social Norms for Persuasive Impact. Social Influence, 1; 3-15.

Cohen, D. (1998). La violencia en los programas televisivos. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 6. (www.ull.es/publicaciones/latina/a/81coh.htm) (12-11-2010).

Comunicar: Revista científica iberoamericana de comunicación y educación, 25.

Drabman, R.S. & Thomas, M.H. (1974). Does Media Violence Increase Children’s Toleration of Real-life Ag-gression? Developmental Psychology, 10(3); 418-421.

Drabman, R.S. & Thomas, M.H. (1976). Does Watching Violence on Television Cause Apathy? Pediatrics, 57(3); 329-331.

Feingold, P.C. & Knapp, M.L. (1977). Antidrug Abuse Commercials. Journal of Communications, 27; 20-28.

Fernández Villanueva, C.; Revilla Castro. J.C. & al. (2008). Los espectadores ante la violencia televisiva: fun-ciones, efectos e interpretaciones situadas. Comunicación y Sociedad, 2; 85-113.

García Galera, M.C. (Dir.) (2008). La telefonía móvil en la infancia y la adolescencia. Informe del Defensor del Menor, Madrid: CAM.

Gentile, D.A.; Lynch, P.J. & al. (2004). The Effects of Violent Videogame Habits on Adolescent Hostility, Ag-gressive Behaviors, and School Performance. Journal of Adolescence, 27; 5-22.

Hornik, R.; Jacobson, L. & al. (2008). Effects of the National Youth Anti-drug Media Campaign on Youths. American Journal of Public Health, 98 (12); 2.229-2.236.

Huesmann, L.R. & Moise, J. (1996). Media Violence: a Demonstrated Public Health Threat to Children. Harward Mental Health Letter, 12 (12); 5-8.

Huesmann, L.R. & Taylor, L.D. (2006). The Role of Media Violence in Violent Behavior. Annual Review of Public Health, 27(1); 393-415.

Huesmann, L.R.; Moise-Titus, J. & al. (2003). Longitudinal Relations between Children’s Exposure to TV Violence and their Aggressive and Violent Behavior in Young Adulthood: 1977-1992. Developmental Psychology, 39; 201-221.

Hyland, M. & Birrell, J. (1979). Government Health Warnings and the Boomerang Effect. Psychological Reports, 44; 643-647.

Igartua, J.J.; Cheng, L. & al. (2001). Hacia la construcción de un índice de violencia desde el análisis agregado de la programación. Zer. Revista de Estudios de Comunicación, 10; 59-79.

McQuail, D. (1991). Introducción a la teoría de la comunicación de masas. Barcelona: Paidós.

Miller, C.H.; Burgoon, M. & al. (2006). Identifying Principal Risk Factors for the Initiation of Adolescent Smoking Behaviors: The Significance of Psychological Reactance. Health Communication, 19; 241-252

Miller, C.H.; Lane, L.T. & al. (2007). Psychological Reactance and Promotional Health Messages: The Effects of Controlling Language, Lexical Concreteness, and the Restoration of Freedom. Human Communication Research, 33; 219-240.

Molitor, F. & Hirsch, K.W. (1994). Children’s Toleration of Real-life Aggression after Exposure to Media Vi-olence: a Replication of the Drabman and Thomas Studies. Child Study Journal, 24 (3); 191-208.

Ringold, D.J. (2002). Boomerang Effect: In Response to Public Health Interventions: Some Unintended Con-sequences in the Alcoholic Beverage Market. Journal of Consumer Policy, 25; 27-63.

Robinson, T.N. & Killen, J.D. (1997). Do Cigarette Warnings Labels Reduce Smoking? Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 151; 267-272.

Stewart, D.W. & Martin, I.M. (1994). Intended and Unintended Consequences of Warning Messages: A Review and Synthesis of Empirical Research. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 13; 1-19.

Thomas, H.M.; Horton, R. & al. (1977). Desensitization to Portrayals of Real-life Aggression as a Function of Exposure to Television Violence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(6); 450-458.

Twerski, A.D.; Weinstein, A.S. & al. (1976). The Use and Abuse of Warnings in Products Li-ability: Design Defect Litigation Comes of Age. Cornell Law Review, 61; 495.

Unger, J.B.; Rohrbach, L.A. & al. (1999). Attitudes toward Anti-tobacco Policy among California Youth: Asso-ciations with Smoking Status, Psychological Variables and Advocacy Actions. Health Educations Research Theory and Practice, 14; 751-763.

Vives, C.; Torrubiano, J. & Álvarez, C. (2009). The Effect of Television News Items on Intimate Partner Violence Murders. European Journal of Public Health; 1-5.

Wegner, D.M. (1994). Ironic Processes of Mental Control. Psychological Review, 10; 34-52.

Wolf, M. (1994). Los efectos sociales de los media. Barcelona: Paidós.

Worchel, S. & Arnold, S.E. (1973). The Effects of Censorship and the Attractiveness of the Censor on Attitude Change. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 9; 365-377.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Los comportamientos violentos causan inquietud entre los responsables públicos (políticos, educadores, asistentes sociales, asociaciones de madres y padres, etc.) que, desde diversos ámbitos, toman medidas que tratan de dar solución al problema de la violencia. La difusión de campañas institucionales de comunicación en contra de la violencia y el fomento de la publicación de noticias relacionadas con sucesos violentos suelen ser algunas de las acciones utilizadas. No obstante, parte de los datos y de la literatura disponible han demostrado que su eficacia no siempre es la esperada e, incluso, dichas acciones pueden llegar a tener efectos contrarios al deseado y reforzar las actitudes de los que piensan que la violencia es necesaria. Se sostiene la hipótesis de que la mayoría de la población asumiría como propios los mensajes contrarios a la violencia. Sin embargo –y esto es la cuestión clave y más problemática– son justo aquellos individuos con mayor propensión a la violencia (precisamente aquellos a quienes deberían dirigirse tales comunicaciones) quienes podrían reaccionar ante el mensaje antiviolencia de un modo no deseado. Se da una dramática paradoja: el mensaje antiviolencia podría aumentar la predisposición a desarrollar comportamientos violentos. Estaríamos ante un caso de lo que cierta literatura denomina efecto boomerang. Por último, se señala la necesidad de un estudio detallado sobre determinados efectos de los medios de comunicación (insensibilización, imitación, accesibilidad y reactancia), que podrían ayudar a explicar la aparición de dicho efecto boomerang.

1. Introducción. La violencia como un problema social

En las sociedades actuales los comportamientos violentos constituyen uno de los problemas que más preocupan al conjunto de la sociedad. Por ello, un amplio grupo de instituciones públicas y diversas organizaciones de iniciativa social (ONGs, asociaciones contra la violencia, etc.) han ido poniendo en marcha diversas acciones para erradicar o, cuanto menos, minimizar las conductas violentas.

Entre todas estas iniciativas, aquí nos ocupamos de aquellas que se centran en la difusión de campañas de comunicación y sensibilización contra la violencia, a fin de plantear hasta qué punto están resultando eficaces y por qué podrían estar fracasando. Partimos de dos hechos probados: a) se está haciendo un importante esfuerzo comunicativo contra la violencia pero, paralelamente, b) los datos parecen indicar que ese esfuerzo no está consiguiendo los resultados deseados.

Prueba de que se está haciendo un importante esfuerzo de difusión, es que las campañas de comunicación contra la violencia han supuesto una importante inversión económica en los últimos años. Por ejemplo, en 2008, la campaña estatal contra la violencia de género Ante el maltratador, tolerancia cero supuso una inversión de cuatro millones de euros, según los datos proporcionados por el Ministerio de Igualdad.

Sin embargo, los resultados esperados no acaban de llegar y a pesar de la existencia de estas campañas de comunicación, los comportamientos violentos no disminuyen, manteniéndose algunos indicadores en cifras verdaderamente alarmantes. Por ejemplo, la evolución en el número de delitos de carácter violento ha experimentado un crecimiento significativo en la última década:

Mientras que en relación a la evolución de las víctimas por violencia de género en España a lo largo de la última década, se puede observar igualmente que los datos siguen siendo preocupantes a pesar de que precisamente ahora se están poniendo más medios para erradicar este grave problema social1.

La pregunta que, por tanto, cabe hacerse es: ¿qué está fallando? Aunque es evidente que todo fenómeno social puede ser explicado por diversas causas, parece que una de las posibles respuestas a esta pregunta es que las campañas diseñadas para sensibilizar a la población en contra del uso de la violencia tienen una eficacia ciertamente limitada. Lo que explicaría que los datos sobre ocurrencia de la violencia se mantengan estables o no disminuyan significativamente. Pero, ¿cómo explicar que tras la difusión de una campaña los datos sobre violencia se eleven? En este sentido, estaríamos hablando no solo de la ineficacia de estas campañas, sino de una cuestión mucho más relevante y problemática: la posibilidad de que se esté generando un efecto perverso y no previsto. Nuestra hipótesis es que aunque la mayoría de las personas integran como propios los mensajes en contra de la violencia, habría un reducido grupo de individuos –con una mayor propensión a la violencia– que reaccionarían ante estos mensajes de una forma no deseada, de manera que el mensaje de la campaña les originara una mayor predisposición a desarrollar comportamientos violentos. Se produce lo que cierta literatura denomina efecto boomerang.

En este contexto, se hace necesaria una reflexión crítica sobre las consecuencias sociales de las campañas de comunicación contra la violencia, que posibilite identificar los motivos que expliquen su aparente fracaso y que nos permita encontrar las claves para idear nuevas campañas más eficaces contra cualquier tipo de violencia. Varias líneas de argumentación pueden ayudarnos a explicar el problema. En este artículo nos ocuparemos de algunas de ellas y de su discusión.

2. El inicio de un problema

Cuando se plantea el diseño de una campaña de comunicación, uno de los primeros pasos es saber a quién nos estamos dirigiendo, cuál es nuestro público objetivo. En este sentido, las características del receptor de la campaña pueden ser muy diversas y, en el caso de las campañas de sensibilización contra la violencia, puede ser especialmente importante tener en cuenta que algunas personas son más proclives a llevar a cabo comportamientos violentos y que la exposición a la campaña podría generar en ellos efectos diferentes a los pretendidos.

Según datos de una encuesta realizada en 2008 sobre uso de móviles por parte de los menores a una muestra de 1053 menores de la Comunidad de Madrid comprendidos entre los 10 y los 16 años, quedaría de manifiesto que existe en torno a un 10% de la población infantil y juvenil de la que podemos afirmar que es particularmente proclive a los comportamientos violentos (García Galera et al., 2008). Los resultados de este estudio revelan cómo estos jóvenes reconocen el deseo de grabar las gamberradas de otros, muestran indiferencia o se divierten con las imágenes violentas colgadas en Internet e incluso en alguna ocasión han grabado peleas, actos violentos o humillantes (por ejemplo bromas al profesor) a través del móvil o colgado dichas grabaciones en la web (YouTube, MySpace).

Este es un dato ciertamente alarmante, que nos sitúa ante un fenómeno cuantitativa y cualitativamente relevante para la convivencia social, ya que estaríamos asistiendo a un escenario en el que determinados jóvenes presentan un elevado grado de insensibilidad y tolerancia hacia ciertos actos de violencia, que no sólo consienten sino que en ocasiones también protagonizan. Desde nuestro punto de vista, este debería ser un dato a tener en cuenta a la hora de diseñar las campañas de sensibilización contra la violencia, ya que ese es el público objetivo al que, indiscutiblemente, debería dirigirse el mensaje de tales campañas.

3. El riesgo del efecto boomerang en la comunicación: evidencia empírica

Si bien, como habíamos señalado, la difusión de campañas de comunicación que pretenden sensibilizar a la población respecto a diferentes problemas sociales y de salud pública (abuso del alcohol, tabaco u otras drogas) es una de las acciones institucionales más utilizadas para tratar de prevenir ciertos comportamientos sociales no deseados, se ha demostrado que, en determinadas circunstancias, dichas campañas podrían estar produciendo un efecto contrario al pretendido. De hecho, parece probarse que podría ser precisamente el público objetivo de estas campañas (alcohólicos, fumadores o drogadictos) el más proclive a generar un efecto rechazo o boomerang ante el mensaje institucional.

A este respecto, se ha ido acumulando una amplia evidencia empírica del efecto boomerang en una variedad de campos donde se difunden campañas institucionales con mensajes de advertencia sobre los riesgos de desarrollar un determinado comportamiento, siendo especialmente significativos los siguientes: las campañas que inciden sobre los riesgos de fumar (Hyland & Birrell, 1979; Robinson & Killen, 1997; Unger & al., 1999); las campañas contra el uso de drogas (Feingold & Knapp, 1997); o las que se centran en el consumo de alcohol (Ringold, 2002).

En el campo de la violencia existe un corpus de investigaciones limitado, aunque se pueden reseñar estudios como el de Bushman y Stack (1996) en los que se pone de manifiesto cómo la utilización de etiquetas que advierten de la emisión de programas con contenido violento, podrían incrementar el interés por ver dichos programas en la audiencia. Si, como se ha demostrado, existe una relación entre la exposición a contenidos violentos y la generación subsiguiente de impulsos o comportamientos violentos, el problema sería que la utilización de dichas etiquetas conduciría a un mayor consumo de violencia mediada y, en consecuencia, a un mayor nivel de violencia real.

4. El riesgo del efecto boomerang en las campañas de comunicación contra la violencia

4.1. Una explicación a partir de los efectos probados de los medios

Hay una larga tradición de estudios que tratan de profundizar en los efectos de los medios de comunicación2. Algunos de estos efectos gozan de una contrastada evidencia empírica, por ejemplo, en lo que se refiere al amplio acuerdo de la comunidad científica a la hora de establecer una relación entre el consumo de violencia audiovisual y la tendencia al desarrollo de comportamientos violentos entre la población infantil y juvenil3. En este sentido, son abundantes los estudios que han conseguido resultados significativos a la hora de correlacionar la exposición a contenidos violentos en los medios de comunicación (fundamentalmente la televisión y los videojuegos) con la generación de pensamientos, actitudes y comportamientos violentos. Estos efectos se han demostrado tanto a corto, como a medio y largo plazo, se han obtenido conclusiones relevantes tanto en varones como en mujeres, y se han conseguido resultados igualmente significativos en una variedad de situaciones de estudio y en diferentes países. Entre otros, podemos citar los trabajos de Huesmann y Moise (1996), Anderson (1997), Anderson y Dill (2000), Anderson y Bushman (2002), Huesmann y otros (2003), Anderson y otros (2003), Gentile y otros (2004), y Huesmann y Taylor (2006).

Para demostrar la influencia que podría tener el consumo de violencia audiovisual en la generación de comportamientos violentos se recurre a diferentes mecanismos entre los que destacan: el «efecto insensibilización» y el «efecto imitación». El primero de ellos nos permitiría explicar por qué las campañas contra la violencia son ineficaces a la hora de reducir la aparición de actos violentos; mientras que el segundo podría explicar no sólo por qué las campañas son ineficaces, sino también por qué a veces dichas campañas generan un efecto contrario al deseado, elevando la probabilidad de que se produzcan actos violentos.

4.1.1. Efecto insensibilización

Aunque es cierto que la exposición a un contenido violento suele producir, en un primer momento, una reacción de rechazo, no es menos cierto que la exposición repetida a la violencia termina por crear un proceso de habituación o acostumbramiento. El espectador, ante las sucesivas escenas de violencia, tiende a mostrar cada vez menores activaciones psicológicas y emocionales. Se puede llegar así a un estado de insensibilización emocional en el que no hay reacción emocional ante estímulos que las primeras veces sí desencadenaban reacciones fuertes. Asimismo, se puede producir una insensibilización cognitiva si se deja de considerar la violencia como algo poco frecuente y anormal, y se empieza a considerar como un aspecto inevitable y habitual de la vida cotidiana. Tanto la insensibilización emocional como la insensibilización cognitiva pueden influir en el comportamiento, dando lugar: bien a una disminución de la probabilidad de que la persona insensibilizada censure una conducta violenta, bien a un aumento de la probabilidad de que las personas insensibilizadas desarrollen conductas agresivas y de que ésta sea, a su vez, de mayor intensidad (Drabman & Thomas, 1974; 1976; Thomas & al., 1977; Molitor & Hirsch, 1994; Carnagey, Anderson & Bushman, 2006).

El efecto insensibilización también ha sido estudiado en el contexto de las investigaciones sobre la efectividad de los mensajes de advertencia que acompañan a determinados productos que podrían ser perjudiciales para la salud o la seguridad del individuo. En este sentido, se considera que la exposición continuada a mensajes de advertencia de todo tipo (alimentación, seguridad vial, etc.) podría contribuir a que las personas dejen de prestarles atención, llegando a ignorar muchos de ellos (Twerski & al., 1976). Esto es especialmente cierto en aquellos casos en el que las consecuencias perjudiciales no aparecen inmediatamente después de realizar la conducta de riesgo, situándonos así ante lo que Breznitz (1984) denomina como falsas alarmas. Un ejemplo, en este sentido, serían los mensajes de advertencia sobre el riesgo de fumar, ya que para este autor si bien es evidente que tragar lejía tiene una consecuencia adversa inmediata, fumar un cigarrillo parece una conducta que no implica riesgos, al menos no inmediatos, y por tanto ello podría reducir la efectividad de los mensajes de advertencia que se exhiben en las cajetillas de tabaco.

Extrapolándolo al tema de la violencia, se podría plantear que algunas personas especialmente violentas podrían sentir una especie de efecto inmunidad ante sus acciones, ya que al no aparecer habitualmente acciones comunicativas que expongan las consecuencias inmediatas de una acción violenta para el agresor (por ejemplo las penas de cárcel asociadas), los violentos ya insensibilizados que consideran la violencia como algo que forma parte de la vida cotidiana –insensibilización cognitiva– podrían llegar a pensar –al igual que algunos fumadores– que su conducta violenta no tendrá consecuencias negativas para ellos mismos.

Aunque el efecto insensibilización podría no relacionarse necesariamente con la aparición de un efecto rebote, sí parece importante destacar que cuanto mayor sea la insensibilización de la persona hacia la violencia en general, menor eficacia tendrán las campañas de comunicación contra la violencia. Y es que, si dado su nivel de insensibilización muchas personas no reaccionan siquiera ante imágenes de violencia real, parece difícil que el mensaje de las campañas contra la violencia –que suelen evitar deliberadamente la difusión de imágenes lesivas– llegue a tener efecto sobre ellas.

4.1.2. Efecto imitación

El ser humano –como ser social que es– aprende, a través de la observación de los demás miembros de su comunidad, a repetir o imitar los comportamientos que son aparentemente válidos o comunes. Por ello, uno de los efectos más característicos asociados a los medios de comunicación es precisamente el conocido como efecto imitación. En el ámbito de las campañas de comunicación contra la violencia, dicho efecto se produciría sólo en el caso de que los mensajes que se comuniquen contengan violencia: informaciones periodísticas que expongan contenidos de violencia explícita o difusión de campañas que contengan imágenes con contenido violento.

Este efecto imitación puede producirse a través de dos mecanismos diferentes que, en cualquier caso, podrían derivar en un efecto boomerang no deseado al elevar la ocurrencia de las conductas violentas inmediatamente después de la difusión de una campaña o información relacionada con la violencia:

a) Validez instrumental: el espectador imitaría el comportamiento porque al observarlo deduce que es útil, ya que la persona que lo ha llevado a cabo previamente ha conseguido algo provechoso con dicho comportamiento. En concreto, en el ámbito de la violencia, existen estudios que muestran cómo los niños y adolescentes tienden a imitar tanto el comportamiento de aquellas personas con las que interactúan habitualmente (familiares, pares, etc.), como el de los personajes que aparecen en los medios de comunicación. En esta línea son ya clásicos los estudios que demuestran tanto la imitación por parte de los niños de conductas agresivas exhibidas por modelos adultos (Bandura & al., 1961), como la imitación de dichas conductas exhibidas por personajes de ficción (Bandura & al., 1963a). Esto es especialmente cierto cuando la acción imitada se ve recompensada (aprendizaje instrumental) o cuando existe admiración y/o identificación con el modelo. De ello cabe deducir que si las campañas de comunicación contienen violencia, podrían generar más violencia por imitación. O dicho de otro modo, conviene evitar que las campañas de comunicación o las informaciones sobre violencia expongan contenidos violentos para evitar el efecto imitación.

b) Validez social: el espectador imitaría la conducta porque observa que la realiza mucha gente y, por tanto, supone que debe ser un modo apropiado de obrar. Numerosos estudios muestran cómo la gente tiende a realizar comportamientos que son compartidos por otras personas, puesto que el hecho de que más gente realice un comportamiento es interpretado como un dato a favor de la validez o corrección de dicho comportamiento (Gould & Shaffer, 1986; Reingen, 1982). Este es un aspecto a tener en cuenta en el diseño de las campañas de comunicación contra la violencia, ya que recientes estudios han mostrado cómo intentar erradicar un comportamiento no deseable (por ejemplo los comportamientos violentos) dando a entender que, desgraciadamente, son muchos los que aún lo realizan, puede tener precisamente el efecto contrario ya que dichas campañas podrían centrar la atención de su público –especialmente el más proclive a tales comportamientos– más en la prevalencia de la acción, otorgándole así una mayor visibilidad, que en su indeseabilidad (Cialdini, 2003; Cialdini & al., 2006; Shulz & al., 2007). En esta línea, estudios recientes (Vives, Torrubiano & Álvarez, 2009) han puesto de manifiesto la influencia negativa que las noticias televisivas acerca de la violencia de género pueden tener sobre el número de muertes registradas por violencia machista.

4.2. Otros mecanismos del efecto boomerang

Además de los efectos probados de los medios señalados con anterioridad, nos parece apropiado señalar aquí dos mecanismos más que podrían explicar –al igual que el efecto imitación– la aparición del efecto rebote o boomerang tras la difusión de una campaña de sensibilización contra la violencia: el aumento de la accesibilidad y la reactancia psicológica.

4.2.1. Aumento de la accesibilidad

Como hemos sugerido anteriormente, el uso de imágenes con contenido violento en comunicaciones destinadas a combatir la violencia podría aumentar las probabilidades de que dichos comportamientos sean reproducidos en un futuro. Consideramos que una nueva posible explicación, alternativa a las anteriores, partiría del hecho de que la exposición a esas imágenes podría provocar que tales comportamientos se hicieran más accesibles en la mente de los receptores. Sin embargo, yendo más allá, la accesibilidad –esto es, la facilidad o rapidez con la que un constructo o concepto viene a nuestra mente– podría también ayudar a explicar el posible efecto perverso de las comunicaciones contra la violencia aun cuando dichas campañas no incluyan imágenes con contenido violento. En línea con investigaciones previas que muestran que intentar suprimir ciertos pensamientos puede hacerlos aun más accesibles (Wegner, 1994), se podría hipotetizar que la utilización que los medios hacen de mensajes con referencia a la violencia aun cuando su finalidad sea la de criticarla, puede tener un efecto perverso al activar y aumentar la accesibilidad de pensamientos e ideas violentas especialmente en aquella parte de la población que ya de por sí sea particularmente proclive a la violencia.

4.2.2. Reactancia psicológica

La reactancia psicológica ha sido definida como el estado activación psicológica que surge cuando nuestra libertad se ve reducida o amenazada (Brehm & Brehm, 1981). La consecuencia más directa de ese estado es una tendencia a resistirse ante todo aquello que pueda considerarse como una amenaza a dicha libertad personal (Brehm, 1966). Así pues, al igual que tendemos a mostrar reactancia cuando, por ejemplo, nos dicen cómo debemos pensar o cuando recibimos órdenes, también tendemos a experimentar reactancia cuando nos prohíben determinados comportamientos (Dillard & Shen, 2005; Miller & al., 2006; Miller & al., 2007). De esta forma, aquellas personas que realizan un comportamiento que está siendo censurado desde las instituciones, se reafirmarían en el mismo como reacción ante una amenaza a su estilo de vida.

Este es también el motivo por el cual, por ejemplo, la gente tiende a desear con mayor intensidad aquella información que ha sido previamente censurada (Worchel & Arnold, 1973). La explicación podría deberse a la necesidad que sienten algunas personas de realizar conductas de riesgo o de trasgredir las normas y los tabús impuestos por la sociedad. En este sentido, Stewart y Martin (1994) consideran que los mensajes de advertencia sobre el riesgo de realizar determinados comportamientos podrían llamar la atención de ciertas personas, impulsándoles a realizar el comportamiento que se trataba de prevenir. Sería como morder la fruta prohibida (Bushman & Stack, 1996).

En consecuencia, han sido muchos los investigadores que han identificado la reactancia psicológica como uno de los factores principales a la hora de explicar el efecto boomerang provocado por diversas campañas persuasivas (Bushman & Stack, 1996; Ringold, 2002; Hornik & al., 2008). Desde nuestro punto de vista, este resultado podría también generalizarse para las campañas contra la violencia, las cuales generarían un efecto rebote cuando las personas más proclives a la violencia o que la utilizan de forma habitual en su vida cotidiana, presencian campañas que prohíben o censuran el uso de la misma.

5. Conclusiones

Es necesario tener en cuenta los efectos insensibilización, imitación, accesibilidad y reactancia psicológica en las campañas e informaciones sobre violencia. Se puede concluir, por tanto, que las dificultades para acabar con los comportamientos violentos podrían estar relacionadas con una falta de adecuación entre los objetivos que se proponen los responsables de políticas sociales (erradicación de los comportamientos violentos) y las acciones de comunicación empleadas (por ejemplo, la difusión de campañas de sensibilización contra la violencia en los medios de comunicación).

No se pretende afirmar aquí que el tratamiento comunicativo que se da a la violencia en los medios de comunicación o en determinadas campañas institucionales sea la única causa de la violencia, sino más bien subrayar que no toda campaña institucional y no toda información bienintencionada contra la violencia alcanzan el fin preventivo que se propone y que, incluso, podrían llegar a tener efectos perjudiciales (efecto boomerang) al igual que sucede en otros ámbitos (por ejemplo, el consumo de drogas).

Consideramos, por ello, que el diseño de cualquier campaña de comunicación contra la violencia, así como el tratamiento periodístico de las noticias sobre violencia, deberían tener en cuenta los distintos riesgos que los estudios sobre los efectos de los medios de comunicación han puesto de manifiesto, con la finalidad de evitar dicho posible efecto perverso.

Una posible propuesta en aras de alcanzar este objetivo partiría en primer lugar de la necesidad de tener en cuenta los estudios disponibles sobre insensibilización. De modo que, aunque en un primer momento la presencia de informaciones o campañas pudo tener un efecto positivo en la erradicación de la violencia, la reiteración de mensajes ha llegado a insensibilizar a los receptores. De ahí la posible ineficacia de los mensajes que se difunden.

En segundo lugar, se debería tener presente la posibilidad de estar generando un efecto imitación, ya que las consecuencias serían todavía más preocupantes. Estaríamos en este caso no sólo ante unas campañas inútiles, sino ante el riesgo de que la presencia de mensajes sobre o con violencia genere acciones violentas. El efecto imitación tiene numerosas pruebas empíricas que lo avalan y, por ello, las campañas de comunicación institucional generalmente lo tienen en cuenta. El mayor problema estaría en las informaciones expuestas en los medios de comunicación, que no siempre cumplen con esos estándares (Vives, Torrubiano & Álvarez, 2009).

Por último, el riesgo de que la comunicación contra la violencia no alcance su objetivo también podría estar relacionado con dos efectos psicológicos de especial relevancia. Por una parte, los estudios sobre accesibilidad del constructo nos alertan de que cualquier mensaje sobre la violencia, incluso aquellos cuya finalidad es combatirla, podría hacer más presente dicho concepto en los pensamientos de las personas. Y por otra parte, los estudios sobre reactancia reclaman nuestra atención sobre el riesgo de que determinadas personas tiendan a posicionarse en contra de cualquier mensaje que amenace su libertad o su autoestima.

A su vez, es importante añadir que, en el caso de las comunicaciones diseñadas a combatir la violencia, tales efectos podrían verse intensificados en todos aquellos sujetos que son particularmente propensos a la violencia. Esto sería especialmente preocupante, ya que estos sujetos más propensos a desarrollar comportamientos violentos son precisamente el público al que deberían dirigirse dichos mensajes.

De lo expuesto se deduce, por tanto, que se podrían estar llevando a cabo prácticas ineficaces o, lo que es incluso más grave, podríamos estar elevando la probabilidad de que se produzcan acciones violentas tras una comunicación de carácter informativo o sensibilizador.

En consecuencia, la reflexión teórica y la revisión bibliográfica que hemos realizado ponen de manifiesto la necesidad de un estudio más profundo sobre fenómenos como la insensibilización, la imitación, el aumento de la accesibilidad y la reactancia psicológica, de cara a poder realizar un diseño más eficaz de futuras acciones comunicativas contra la violencia. En concreto, parece especialmente necesario el desarrollo de investigaciones empíricas que permitan comprobar experimentalmente las hipótesis propuestas en este trabajo

Notas

1 De hecho en 2004 se creó el Ministerio de Igualdad (integrado en octubre de 2010 como Secretaría General del nuevo Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad) que ha impulsado diversas medidas de prevención y sensibilización y actuación como la Ley Integral contra la Violencia de Género (L.O. 1/2004), campañas de comunicación, actividades pedagógicas, teléfono de atención personalizada, etc.

2 No son pocos los textos que, ante la abundancia de publicaciones sobre efectos de los medios de comunicación, han tratado de sistematizar lo publicado y proponen un recorrido por las investigaciones sobre los efectos. Entre los textos clásicos destacan el de McQuail (1991) o el de Wolf (1994). Asimismo, para una aproximación en castellano se pueden consultar los trabajos de Brändle, Martín Cárdaba y Ruiz San Roman (2009); Igartua et al. (2001); Fernández Villanueva et al. (2008); Cohen (1998); Barrios (2005).

3 Prueba de esta consonancia entre la comunidad científica es la reciente elaboración de un texto presentado en la Corte Suprema Americana por la American Psychological Association (APA) y la American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) que alertaba de la probada relación entre el uso de videojuegos violentos y la subsiguiente generación de conductas agresivas en niños y adolescentes (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009).

Referencias

American Academy of Pediatrics (2009). Pediatrics. (www.pediatrics.org) (15-12-2010).

Anderson, C.A. & Bushman, B. J. (2002). The Effects of Media Violence on Society. Science, 295; 2.377-2.378.

Anderson, C.A. & Dill, K.E. (2000). Video Games and Aggressive Thoughts, Feelings, and Behavior in the La-boratory and in Life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(4; 772-790.

Anderson, C.A. (1997). Effects of Violent Movies and Trait Hostility on Hostile Feelings and Aggressive Thoughts. Aggressive Behavior, 23; 161-178.

Anderson, C.A.; Berkowitz, L. & al. (2003). The Influence of Media Violence on Youth. American Psychological Society, 4(3); 81-110.

Bandura, A., Ross, S. & Ross, S. A. (1963b). Vicarious Reinforcement and Imitative Learning. Journal of Ab-normal and Social Psychology, 67(6); 601-607.

Bandura, A., Ross, S. & Ross, S.A. (1961). Transmission of Aggression through Imitation of Aggressive Models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63(3); 575-582.

Bandura, A.; Ross, S. & Ross, S.A. (1963a). Imitation of Film-mediated Aggressive Models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66(1); 3-11.

Barrios Cachazo, C. (2005). La violencia audiovisual y sus efectos evolutivos: un estudio teórico y empírico.

Brehm, J.W (1966). A Theory of Psychological Reactance. New York: Academic Press.

Brehm, S.S. & Brehm, J.W. (1981). Psychological Reactance: A Theory of Freedom and Control. Academic Press: New York.

Breznitz, S. (1984). Cry Wolf: The Psychology of False Alarms. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum & Associates.

Brändle, G.; Martín Cárdaba, M.A. & Ruiz San Román, J.A. (2009). El riesgo de efectos no queridos en cam-pañas de comunicación contra la violencia. Discusión de una hipótesis de trabajo, en Nova, P.; Del Pino, J. (Eds.). Sociedad y tecnología: ¿qué futuro nos espera? Madrid: Asociación Madrileña de Sociología; 191-198.

Bushman, B.J. & Stack, A.D. (1996). Forbidden fruit versus tainted fruit: effects of warnings labels on attraction to television violence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 2; 207-226.

Carnagey, N.L.; Anderson, C.A. & Bushman, B.J. (2007). The Effect of Videogame Violence on Psychological Desensitization to Real-life Violence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43; 489-496.

Cialdini, R.B. (2003). Crafting Normative Messages to Protect the Environment. Current Directions in Psycho-logical Science, 12; 105-109.

Cialdini, R.B.; Demaine, L.J. & al. (2006). Managing Social Norms for Persuasive Impact. Social Influence, 1; 3-15.

Cohen, D. (1998). La violencia en los programas televisivos. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 6. (www.ull.es/publicaciones/latina/a/81coh.htm) (12-11-2010).

Comunicar: Revista científica iberoamericana de comunicación y educación, 25.

Drabman, R.S. & Thomas, M.H. (1974). Does Media Violence Increase Children’s Toleration of Real-life Ag-gression? Developmental Psychology, 10(3); 418-421.

Drabman, R.S. & Thomas, M.H. (1976). Does Watching Violence on Television Cause Apathy? Pediatrics, 57(3); 329-331.

Feingold, P.C. & Knapp, M.L. (1977). Antidrug Abuse Commercials. Journal of Communications, 27; 20-28.

Fernández Villanueva, C.; Revilla Castro. J.C. & al. (2008). Los espectadores ante la violencia televisiva: fun-ciones, efectos e interpretaciones situadas. Comunicación y Sociedad, 2; 85-113.

García Galera, M.C. (Dir.) (2008). La telefonía móvil en la infancia y la adolescencia. Informe del Defensor del Menor, Madrid: CAM.

Gentile, D.A.; Lynch, P.J. & al. (2004). The Effects of Violent Videogame Habits on Adolescent Hostility, Ag-gressive Behaviors, and School Performance. Journal of Adolescence, 27; 5-22.

Hornik, R.; Jacobson, L. & al. (2008). Effects of the National Youth Anti-drug Media Campaign on Youths. American Journal of Public Health, 98 (12); 2.229-2.236.

Huesmann, L.R. & Moise, J. (1996). Media Violence: a Demonstrated Public Health Threat to Children. Harward Mental Health Letter, 12 (12); 5-8.

Huesmann, L.R. & Taylor, L.D. (2006). The Role of Media Violence in Violent Behavior. Annual Review of Public Health, 27(1); 393-415.

Huesmann, L.R.; Moise-Titus, J. & al. (2003). Longitudinal Relations between Children’s Exposure to TV Violence and their Aggressive and Violent Behavior in Young Adulthood: 1977-1992. Developmental Psychology, 39; 201-221.

Hyland, M. & Birrell, J. (1979). Government Health Warnings and the Boomerang Effect. Psychological Reports, 44; 643-647.

Igartua, J.J.; Cheng, L. & al. (2001). Hacia la construcción de un índice de violencia desde el análisis agregado de la programación. Zer. Revista de Estudios de Comunicación, 10; 59-79.

McQuail, D. (1991). Introducción a la teoría de la comunicación de masas. Barcelona: Paidós.

Miller, C.H.; Burgoon, M. & al. (2006). Identifying Principal Risk Factors for the Initiation of Adolescent Smoking Behaviors: The Significance of Psychological Reactance. Health Communication, 19; 241-252

Miller, C.H.; Lane, L.T. & al. (2007). Psychological Reactance and Promotional Health Messages: The Effects of Controlling Language, Lexical Concreteness, and the Restoration of Freedom. Human Communication Research, 33; 219-240.

Molitor, F. & Hirsch, K.W. (1994). Children’s Toleration of Real-life Aggression after Exposure to Media Vi-olence: a Replication of the Drabman and Thomas Studies. Child Study Journal, 24 (3); 191-208.

Ringold, D.J. (2002). Boomerang Effect: In Response to Public Health Interventions: Some Unintended Con-sequences in the Alcoholic Beverage Market. Journal of Consumer Policy, 25; 27-63.

Robinson, T.N. & Killen, J.D. (1997). Do Cigarette Warnings Labels Reduce Smoking? Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 151; 267-272.

Stewart, D.W. & Martin, I.M. (1994). Intended and Unintended Consequences of Warning Messages: A Review and Synthesis of Empirical Research. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 13; 1-19.

Thomas, H.M.; Horton, R. & al. (1977). Desensitization to Portrayals of Real-life Aggression as a Function of Exposure to Television Violence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(6); 450-458.

Twerski, A.D.; Weinstein, A.S. & al. (1976). The Use and Abuse of Warnings in Products Li-ability: Design Defect Litigation Comes of Age. Cornell Law Review, 61; 495.

Unger, J.B.; Rohrbach, L.A. & al. (1999). Attitudes toward Anti-tobacco Policy among California Youth: Asso-ciations with Smoking Status, Psychological Variables and Advocacy Actions. Health Educations Research Theory and Practice, 14; 751-763.

Vives, C.; Torrubiano, J. & Álvarez, C. (2009). The Effect of Television News Items on Intimate Partner Violence Murders. European Journal of Public Health; 1-5.

Wegner, D.M. (1994). Ironic Processes of Mental Control. Psychological Review, 10; 34-52.

Wolf, M. (1994). Los efectos sociales de los media. Barcelona: Paidós.

Worchel, S. & Arnold, S.E. (1973). The Effects of Censorship and the Attractiveness of the Censor on Attitude Change. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 9; 365-377.

Document information

Published on 30/09/11

Accepted on 30/09/11

Submitted on 30/09/11

Volume 19, Issue 2, 2011

DOI: 10.3916/C37-2011-03-08

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?