Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

The use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) has extended to all contexts of our lives in the last few years, modifying our communication, learning, entertainment and socialization habits. The aim of the present research is to investigate about primary-age children's habits with these tools, as well as these children's perception of parental mediation in this area. In this study we used an ex post facto descriptive methodology by survey. A questionnaire was applied for data recollection to 422 children of private schools in Santiago de Chile aged between 9 and 12 years old. The results point to an early access to electronic devices and the transversal and homogeneous use during childhood. There is no doubt that ICTs play an active role in daily life for most of these children. No significant differences in age or sex were detected in our study, but we encountered risky behaviours in how children use ICTs and in their perception of parental mediation. The complexity becomes more evident the more time they have with electronic devices connected to the Internet without adult supervision. This finding raises the need for the application of intervention programs on parental mediation of children's use of ICTs in order to promote a safe, responsible and ethical use of these tools.

1. Introduction and state of the art

Technological advances have changed our daily lives: communication or news reading are digital activities now. The most significant increase in the use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) took place among the younger population. Minors are exposed, from a very early age, to ICTs (Lepicnik & Samec, 2013) and they use them without any specific training (Area, Gros & Marzal, 2008). They are active members of the «e-society» (MacPake, Sthepen & Plowman, 2007), who have a considerable proficiency in digital technologies that provides them with «hyperconnectivity» and ubiquity. This creates a digital gap between children and adults. Although the use of ICTs entails a series of advantages, it can also involve some risks for minors.

We analyse here how ICTs are used by 9 to 12 year-old children and how they perceive parental mediation. The study covered four of the technologies more widely used by children (the Internet, television, video games and mobile phones). We studied how they were used (weekly frequency, place, time and whether they were accompanied or not) and also parental mediation in that use (times, activities and contents). The variables of sex and age were also taken into consideration.

1.1. Children and ICTs

Research (Gutnick, Robb, Takeuchi & Kotler, 2010; Bringué & Sádaba, 2008; Sádaba & Bringué, 2010; Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011) has shown some worrying data about children’s use of the Internet: 80% of children between the ages of 5 to 9 surf the Web regularly and 60% of them say they do it without supervision. Research carried out by Bringué & Sádaba (2008) in Chile offers some data about possible Internet risks for children, pointing out that 5% of 10-year-old users have occasionally accessed pornographic websites and that 13% accessed violent contents. More recent research (Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011) shows that more than half of the children aged between 6 and 9 are autonomous users and that 30% of minors use social networks such as Facebook. They also state the worrying fact that 50% of 10-year-old boys and 33% of 10-year-old girls state that they have met in person somebody they first met online. Although the Internet is a useful tool for the development of minors, some specialists (Bringué & Sádaba, 2008; Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011; García & Bringué, 2007; Garmendia, Casado, Martínez & Garitaonandia, 2013; Livingstone, 2013) have shown the risks of accessing the Internet unsupervised or without having proper training: violence, pornography, addictions or cyberbullying, among others.

One could think that the presence of technologies that allow interactivity, ubiquity and mobility would have replaced the use of the television. However, recent research carried out by Mediametrie and Eurodata TV for the 8th edition of «Kids TV Report: Trends & Hits in Children’s Programming in France, Germany, Italy, Spain & the UK» (2013) shows that daily television consumption among Europeans between 4 and 12 years of age during 2012 was 2 hours and 16 minutes. Research in Chile (CNTV, 2010; CNTV, 2012a; CNTV, 2012b) points out that the average television consumption time by children between 4-12 years is 4 hours a day. This figure means that they practically double the time of European children, although the most worrying fact is that 78.2% of them watch television programs for adults. Several authors have pointed out that access to inappropriate contents can result in behaviour problems due to the lack of appropriate topics and structures and the minor’s low level of maturity and lower capacity for assimilating contents.

The use of video games is very extensive among children. Video games are multi-platform leisure programs (for computers, mobile phones and consoles) (García & Bringué, 2007), where the variety of narrative structures and interactivity schemes allows the user to adapt the game to their rhythm and style (Rangel, Ladrón-de-Guervara, Goncalves & Zambrano, 2011). This is precisely what has allowed children to access video games at an early age, as research by (Lloret, Cabrera & Sanz, 2013) shows: in Spain, 90% of children between 6 and 9 years of age play video games. In Chile, 57% of children have this hobby (Bringué & Sádaba, 2008). Regarding sex and age of Chilean «videogamers», research by (Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011) concludes that 70% of children are already users at the age of 6, with no difference in sex. Between 7 and 10 years, that figure increases in boys and decreases in girls. It is important to point out that this activity promotes the acquisition of digital competencies, which favours the link with the educational context. Some researchers (Rojas, 2008) warn that video games have a certain amount of violence and that a continuous exposure to it might lead to increase of hostility and aggressiveness and lack of empathy. However, maybe different variables are responsible for the increase in aggressiveness.

Finally, in the last few years, mobile phones have become part of children’s daily lives: «In Europe, one out of three mobile phones are in the hands of a minor. In Spain, half of the children between 11 and 14 years of age have a mobile phone» (García & Bringué, 2007:111). A transnational study carried out in Japan, India, Indonesia, Egypt and Chile (Livingstone, 2013) shows that 65% of minors between 10 and 18 years of age have access to a mobile phone, 81% owns a new mobile phone and 20% owns a «smartphone». In Latin America, more than half of children between 6 and 9 years of age is a mobile phone user (Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011). In Chile, researchers established that children have their first mobile phone at approximately the age of 10. However, between 6 and 9 years, they already use them, mainly to play and talk, with similar percentages in boys and girls (Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011; Livingstone, 2013). It is clear, therefore, that Chilean children start using mobile phones at an early age. Accordingly, it is fundamental that adults promote a responsible and safe use of these devices to avoid risks such as addiction, cyber bullying, «grooming», «sexting», among others.

1.2. Parental mediation and ICTs

The massive use of ICTs during the last decade has caused a number of social changes, as can be seen in the denominations that our current generations receive in literature: digital natives, «e-society», «touch» generation or «multi-screen» generation (MacPake, Sthepen & Plowman, 2007; Prensky, 2011). These minors have grown up using ICTs, whereas adults have learnt on the fly, which has caused a digital gap between both generations. Probably, the lack of knowledge about the effects of using ICTs is the cause of the little concern in some parents, who just supervise the time and obviate contents that would require parental mediation (Garitaonandia & Garmendia, 2009; Garmendia, Casado, Martínez & Garitaonandia, 2013; Livingstone, Haddon, Görzig & Ólafsson, 2010). Research carried out in Chile (Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011) shows that 50% of children declare being asked by their parents about their online activities and 36% of them consider that they are being watched by their parents as they surf the Web. The activities which are more frequently forbidden are online shopping (47%) and giving personal information (46%). Chatting, downloading files and playing were forbidden for 7% of the children and accessing a social network was forbidden for 3% of the children surveyed. Parental mediation is very important because parents establish security and responsibility criteria for an appropriate use of ICTs and they play a role in the development and acquisition of adequate behaviours in the use of these technologies (Livingstone & Helsper, 2008).

2. Material and method

2.1. Sample selection and research instrument

The sample is intentional and the sample size is N=422 (50.5%, 49.5% female) between 9 and 12 years old, with an average of 9.8 years of age and a typical deviation of 0.906 years. The average in males is 9.86 years of age, with a deviation of 0.903. In females, the values are 9.74 and 0.878 respectively. They are pupils in the 4th, 5th and 6th years of Primary Education in 5 private schools in Santiago de Chile.

A survey was used to collect the following data: socio-demographic data (age, sex, year, school); how children between 9 and 12 years of age use ICTs (weekly frequency, place, time and what company they have while using them); how they perceive parental mediation when using ICTs (times, activities and risks).

2.2. Design

This is an exploratory study of empirical-analytical type, where an ex post facto descriptive methodology by survey has been used. The survey was checked for reliability before being applied. The reliability test was a=0,87, and therefore, considered satisfactory. The survey was validated by two specialists and it was conducted among 30 children in order to modify the items that lead to error. The definitive version was conducted during the 2013 school year. Respondents answered the survey anonymously and with previous consent of their legal tutors.

3. Analysis and results

A descriptive statistical analysis with frequencies and percentages was carried out using the SPSS statistical software program (v. 21.0). In order to check independent variables (sex and age), the ?2 test was applied.

3.1. Use of ICTs by children between 9 and 12 years of age

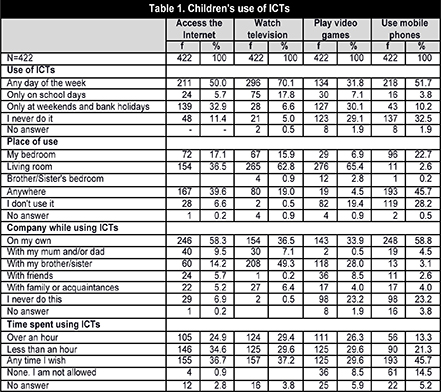

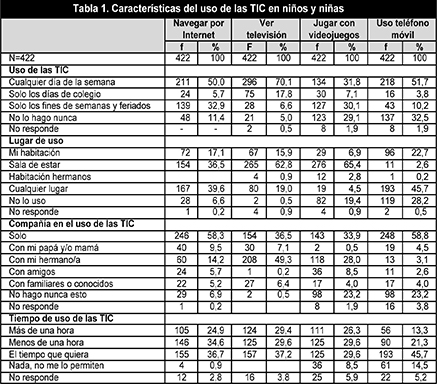

Table 1 shows the data provided by the sample regarding weekly frequency; place, company and time spent using ICTs. Results show that half of the children surf the Web any day of the week, over a third of the children connect from anywhere and that most of them access the Web without supervision. The small number of children surveyed that use the Internet accompanied by their parents is remarkable. Those who have no time restriction are about the same number as those who can log on less than an hour a day.

Regarding television consumption, most of them watch television any day of the week and this is done normally in the living room, mainly accompanied by brothers/sisters. The fact that 37.2% say that they can watch television as long as they wish is worthy of note.

On the topic of the use of video games, there are practically no differences between the percentages of those who play any day of the week, those who only play at weekends and bank holidays and those who never play. Most of them play in the living room and unaccompanied. Only two children play with their parents. Regarding daily use, results are homogeneous: 29.6% are allowed to play less than an hour and the same percentage is allowed to play as long as they wish. Mobile phones are used by more than half of the children any day of the week from anywhere and mainly without any time restriction. The fact that 32.5% declare that they do not use it is worthy of mention.

3.2. Perceived parental mediation while using ICTs

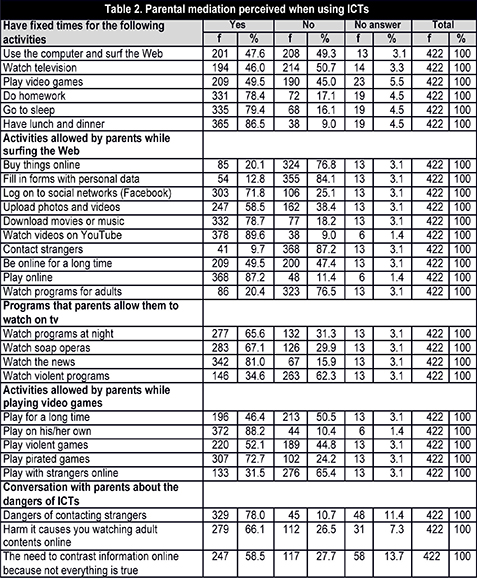

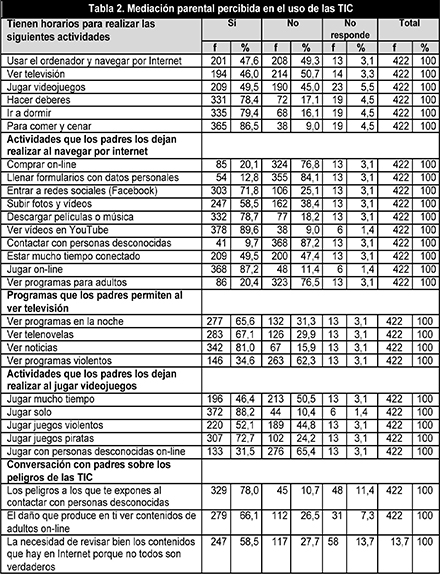

Table 2 shows the main results concerning how parental mediation is perceived by children. Half of the children surveyed indicate that they have no time constraints when they use the computer, surf the Web or watch television. Time limits are present, however, when they play video games. In other activities of their daily life (doing homework, sleeping, meals), most of them say they do have fixed times.

As regards allowed Internet activities, most of the children state that they are allowed to log on to social networks (Facebook), to upload pictures and videos, to download movies and music, to watch videos on YouTube, to be online for a long time and to play online video games. The forbidden activities are online shopping, filling in forms with personal details and contacting strangers.

These results show risk behaviours. Accessing social networks such as Facebook is one of these risks, taking into account that the subjects surveyed are all under 13 of age, which is the legally required minimum age to create a profile in that website by filling in a form with personal details. Furthermore, it is very easy to contact strangers in this social network. The other activities allowed entail certain risks such as access to inappropriate contents (violence, pornography), giving away personal information, addiction or contact with strangers. Therefore, there is a contradiction that shows a certain lack of knowledge about the dangers that these activities imply in the children’s lives.

As for television programs, most of the children surveyed indicate that they are allowed to watch programs at night, soap operas and the news. Forbidden programs are those with adult or highly violent contents. These results show a paradox, as programs allowed do have adult contents and show explicit or implicit violence in some cases.

Regarding parental mediation perceived while playing video games, the high percentage of children who are allowed to play on their own is worthy of note and also that more than half of the children say they do not have any parental restriction for violent games. Risky behaviours can be noted: 46.4% of the children have parental permission to play for a long time and 31.5% state that they are allowed to play with strangers online. On the other hand, most of the children state that they talk with their parents about the risks of ICTs, especially about the topic of contacting strangers.

3.3. Age and sex in the use of ICTs

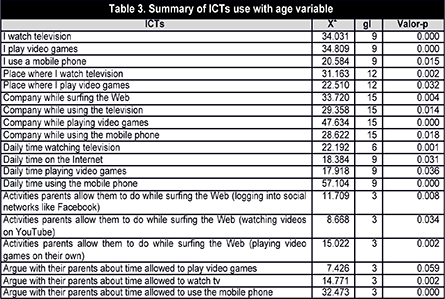

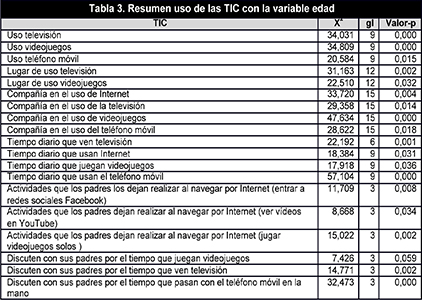

To analyze the influence of «age» and «sex», Chi-square tests were conducted in contingency tables, which prove the association between the variables analyzed. If we selected «age» with four categories (9, 10, 11 and 12 years old) the requirements for the test (minimum expected values of less than 5 per cell) would not be met. To solve this problem, we group «age» in two blocks (9-10 and 11-12), although this creates categories with two ages and this will alter the true behaviour between the variables. Despite the fact it is a significant figure from a strictly statistical point of view, 53.5% cannot be considered as representative. Significant results should be greater when the sample increases.

When doing a crosstab between variable «sex» and the results obtained in ICTs, 96.0% of them show no significance. However, we appreciate a certain significance in the activity «watch videos on YouTube» [(?2=4.170; GL=1; p=0.041)] and the perception of digital skills that they consider they have in comparison to their family, friends and teachers [(?2=8.056; GL=3; p=0.045)]. Significance in the case of males is slightly greater than in the case of females.

4. Discussion and conclusions

According to our analysis of how children use ICTs (frequency, place, company and time), most of the children surveyed have access to the Internet, half of them access the Web any day of the week and more than a third do that from anywhere. Compared to previous years, this shows a change in the place of access that can be explained due to the massive proliferation of 3G devices, which provide ubiquity and hyperconnectivity, important characteristics of children of this generation. Regarding the company they have while surfing the Web, 58.3% state they do it on their own, only 9.8% are accompanied by their parents while they are online and 36.7% has no limit to be online. We can appreciate that there is a risk in children using the Internet without parental supervision (Casado, Martínez & Garitaonandia, 2013; Livingstone, 2013).

Regarding television consumption, results show that 70.0% of the children watch television any day of the week, although is important to point out that this activity takes places mainly in the living room and they are accompanied, mostly by their siblings. If the television is in a common space and they are accompanied there are less probabilities that they may have access to inappropriate contents. However, 37.2% state that they watch television as long as they wish, which is coherent with results from (CNTV, 2012a).

As regards mobile phones, results indicate that most children have a mobile device and more than half of them uses a mobile phone any day of the week from anywhere and has no time limit to use it. This corroborates data by (Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011; Livingstone 2013), who insist on the need for parental supervision on the use of mobile phones due to the risky behaviours observed.

As long as perceived parental mediation in the use of ICTs is concerned, results point out that half of the children do not have specific times to use the computer, to access the Internet or to watch television. They do, however, have time limits when playing video games. Establishing fixed times for activities is a fundamental part of setting boundaries and, as well as helping in a better use of ICTs, it contributes to the prevention of risky behaviours.

As regards Internet activities allowed, the high percentage of children allowed to log on to social networks (Facebook), to upload pictures and videos, to download movies and music, to watch videos on YouTube, to be online for a long time and to play online video games is worthy of note. The forbidden activities are online shopping, filling in forms with personal details and contacting strangers. There is a paradox in the fact that despite the fact that children are not allowed to provide personal information or to contact strangers, most of them are allowed to use Facebook. The subjects surveyed are all under 13 of age, which is the legally required minimum age to create a profile in that social network by filling in a form with personal details. Furthermore, it is very easy to contact strangers on Facebook. The other activities allowed entail certain risks such as access to inappropriate contents (violence, pornography), giving away personal information, addiction or contact with strangers. This information shows a certain lack of knowledge about the risks that these activities imply in the children’s lives. Therefore, family dialogue should be encouraged to agree on the right times and places for use of ICTs and on the accepted digital contents, web services and people that can be contacted (Berríos & Buxarrais, 2005; Buxarrais, Noguera, Tey, Burguet & Duprat, 2011).

Concerning television consumption, children declare that their parents allow them to see evening programming, soap operas and the news, whereas adult and violent programs are forbidden. This coincides with data by CNTV (2012b).These results show a contradiction, as programs allowed have adult contents and show explicit or implicit violence in some cases. This lack of attention might lead to children’s misunderstanding of what they are watching, experiencing strong emotions without expressing them or lack of a critical point of view towards the information received. The positive aspect is that most children surveyed watch television in common spaces, which facilitates supervision.

Most indicate that they talk to their parents about the risks of using ICTs such as contacting strangers, harm derived from watching adult contents or reliability of documents online.

According to the variables analysed (age and sex), in the four age rangesthere is no difference in the use of ICTs, although there is a link between age and use. For television and video games, space is generally closely linked to common areas of the house. When using each device, there is a correlation with age, use and company. They use ICTs mostly on their own. No significant differences were found between males and females either in use of ICTs or in how children perceive parental mediation. This contradicts previous research by (Bringué & Sádaba, 2008; Bringué & Sádaba, 2009; Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011).

We can appreciate that ICTs are part everyday life for most of the 9-12 year-old children surveyed. The Chilean interactive generation surpasses the average of other countries in the region, due to the access to all technologies (Bringué & Sádaba, 2008). There is no doubt that this is a generation with early access to the technological world (Aguaded, 2011): at pre-school age, they already have access to ICTs at home (Plowman, McPake & Stephen, 2010; Plowman, Stevenson, Stephen & McPake, 2012; Plowman, Stephen & McPake, 2012; Lepicnik & Samec, 2013). Due to its importance in cognitive development, we propose here parenting schools that promote training in the appropriate use of technologies with a safe, ethical, integrative and responsible way, so that children’s times in front of a screen can be controlled and the contents they access can be supervised.

The main limitation of this study is that the research instrument was applied only in private schools of high socio-economic level. Therefore, results could hardly explain the reality of stat e schools and publicly-funded private schools, mainly due to the social segmentation present in Chilean education. As a prospective expansion of the research, the survey will be conducted with children from state schools, publicly-funded private schools and private schools to establish a comparison between all three realities. Also, a qualitative section will be incorporated to take into consideration families and teachers.

The study shows innovative contributions regarding the children’s perceptions concerning parental mediation in the use of ICTs within the Chilean context. Being an exploratory study, it is only an initial study of this topic.

References

Aguaded, I. (2011). Niños y adolescentes: nuevas generaciones interactivas. Comunicar, 36, 7-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C36-2011-01-01).

Area, M., Gros, B. & Marzal, M. (2008). Alfabetizaciones y tecnologías de la información y la comunicación. Madrid: Síntesis.

Berríos, L., & Buxarrais, M.R. (2005). Las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC) y los adolescentes. Algunos datos. OEI, 5. (http://goo.gl/cEJjtA) (10-02-2015).

Bringué, X., & Sádaba, C. (2009). La generación interactiva en España: Niños y adolescentes ante las pantallas. Barcelona: Ariel.

Bringué, X., & Sádaba, C. (Coord.). (2008). La generación interactiva en Iberoamérica 2008: Niños y adolescentes ante las pantallas. Barcelona: Ariel/Fundación Telefónica.

Bringué, X., Sádaba, C., & Tolsá, J. (2011). La generación interactiva en Iberoamérica 2010. Niños y adolescentes ante las pantallas. Madrid: Foro Generaciones Interactivas.

Buxarrais, M.R., Noguera, T., Tey, A., Burguet, M., & Duprat, F. (2011). La influencia de las TIC en la vida cotidiana de las familias y los valores de los adolescentes. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona/ Observatori Educació Digital.

Consejo Nacional de Televisión. (2010). Anuario de programación infantil: oferta y consumo. Santiago: Consejo Nacional de Televisión de Chile.

Consejo Nacional de Televisión. (2012a). Los padres y la regulación televisiva. Santiago: Consejo Nacional de Televisión de Chile.

Consejo Nacional de Televisión. (2012b). Encuesta niños, adolescentes y televisión: consumo televisivo multi-pantalla, control parental, identificación con jóvenes en pantalla. Santiago: Consejo Nacional de Televisión de Chile.

García, F., & Bringué, X. (2007). Educar hij@s interactiv@s. Una reflexión práctica sobre las pantallas. Madrid:Rialp/Instituto de Ciencias para la Familia, Universidad de Navarra.

Garitaonandia, C., & Garmendia, M. (2009). Cómo usan Internet los jóvenes: hábitos, riesgos, y control parental. (http://goo.gl/PNrTYk) (10-04-2014).

Garmendia, M., Casado, M., Martínez, G., & Garitaonandia, C. (2013). Las madres y padres, los menores e Internet. Estrategias para la mediación parental en España. Doxa, 17, 99-117.

Gutnick, A.L., Robb, M., Takeuchi, L., & Kotler, J. (2010). Always Connected: The New Digital Media Habits of Young Children. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop.

Lepicnik, J., & Samec, P. (2013). Uso de tecnologías en el entorno familiar en niños de cuatro años de Eslovenia. Comunicar, 40, 119-126. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-03-02

Livingstone, S. (2013). Children´s Use of Mobile Phones: An International Comparasion, 2012. GSM, 3. (http://goo.gl/DIZDyl) (10-02-2015).

Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. (2008). Parental Mediation and Children’s Internet Use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 52(4), 581-599.

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., & Olafsson, K. (2010). Risks and Safety on the Internet. The Perspective of European Children. Initial Findings from the EU Kids Online Survey of 9-16 Year Olds and their Parents. (http://goo.gl/NpjfvQ) (10-02-2015).

Lloret, D., Cabrera, V., & Sanz, Y. (2013). Relaciones entre hábitos de uso de videojuegos, control parental y rendimiento escolar. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 3, 249-260.

Mcpake, J., Stephen, C. & Plowman, L. (2007). Entering E-Society. Young Children’s Development of E-Literacy. University of Stirling (http://goo.gl/sZk6BW) (13-04-2012).

Mediametrie, Eurodata TV. (2013). Kids TV Report: Trends & Hits in Children’s Programming in France, Germany, Italy, Spain & the UK. (http://goo.gl/4VOlbb) (17-01-2014).

Plowman, L., Mcpake, J., & Stephen, C. (2010). The Technologisation of Childhood? Young Children and Technologies at Home. Children and Society, 24(1), 63-74.

Plowman, L., Stephen, C., & Mcpake, J. (2012). Young Children Learning with Toys and Technology at Home. Research Briefing, 8 (http://goo.gl/fY9Yxk) (10-02-2015).

Plowman, L., Stevenson, O., Stephen, C., & Mcpake, J. (2012). Preschool Children’s Learning with Technology at Home. Computers & Education, 59(1), 30-37.

Prensky, M. (2011). Enseñar a nativos digitales. Madrid: SM.

Rangel, A., Ladrón-De-Guevara, I., Goncalves, I., & Zambrano, L. (2011). Los videojuegos en ambientes de desarrollo infantil y juvenil: propuestas para definirlos, clarificarlos y aprovecharlos como entornos de investigación psicológica. Psicología, 30(2), 15-29.

Rojas, V. (2008). Influencia de la televisión y videojuegos en el aprendizaje y conducta infanto-juvenil. Revista Chilena de Pediatría, 79, 80-85. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S037-41062008000700012

Sádaba, C., & Bringué, X. (2010). Niños y adolescentes españoles ante las pantallas: rasgos configuradores de una generación interactiva. CEE Participación Educativa, 15, 86-104. (http://goo.gl/cNkeCd) (12-08-2011).

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El uso de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC) se ha ido masificando en los últimos años, modificando los hábitos de comunicación, aprendizaje, entretenimiento y de socialización. Hemos investigado sobre los hábitos de los menores con dichas herramientas, además de su percepción de la mediación parental en este terreno. Se presenta un estudio exploratorio, en el que se emplea metodología ex post facto descriptiva por encuesta, con un cuestionario como instrumento de recolección de datos aplicado a 422 niños/as de 9-12 años de colegios privados de Santiago de Chile. Los resultados indican que las TIC forman parte de la vida cotidiana para la mayoría de los niños/as. A pesar de no apreciarse diferencias significativas, en edad y género, se encontraron comportamientos de riesgo entre las características de uso y en la percepción de la mediación parental, por lo que vislumbramos la necesidad de implementar programas de intervención sobre mediación parental en el uso de las TIC, para así promover un uso seguro, responsable y ético de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación. De los resultados deriva la reflexión en cuanto a la importancia de formar y fomentar desde temprana edad en el uso idóneo de las TIC, considerando que estas herramientas son utilizadas de forma cada vez más transversal y homogénea entre los más jóvenes.

1. Introducción y estado de la cuestión

Los avances tecnológicos han irrumpido en la vida cotidiana: comunicarse, leer noticias han sido digitalizados. Pero el aumento más significativo del uso de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC) ocurre precisamente entre la población más joven. Los menores están expuestos desde muy pequeños a las TIC (Lepicnik & Samec, 2013) y las usan sin formación específica (Area, Gros & Marzal, 2008). Son miembros activos de la «esociety» (MacPake, Sthepen & Plowman, 2007), que posee una elevada digitalización, lo que les dota con «hiperconectividad» y ubicuidad, generándose una brecha digital entre niños y adultos. Si bien, el uso de las TIC comporta varias ventajas, conlleva además una serie de riesgos para los menores.

Aquí analizamos el uso de las TIC y la mediación parental percibida por los niños y niñas entre los 912 años. En el estudio se abordaron cuatro de las tecnologías más utilizadas por los menores (Internet, televisión, videojuegos y teléfono móvil). Se investiga sobre las características de su uso (frecuencia semanal, lugar, compañía y tiempo) y sobre la mediación parental en el tema (horarios, actividades y contenidos). Además, se examinaron las variables categóricas edad y sexo.

1.1. Niños y TIC

Diversos estudios (Gutnick, Robb, Takeuchi & Kotler, 2010; Bringué & Sádaba, 2008; Sádaba & Bringué, 2010; Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011) han puesto de manifiesto algunos datos preocupantes referidos al uso de Internet por parte de los niños. Según ellos, el 80% de niños entre 59 años navega regularmente y el 60% y 70% admite navegar solo.

En Chile, el estudio realizado por Bringué y Sádaba (2008) ofrece datos sobre los riesgos a los que se exponen los niños en Internet, señalando que un 5% de los usuarios de 10 años ha accedido ocasionalmente a páginas pornográficas y un 13% a contenidos violentos. Estudios más recientes (Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011) establecen que más de la mitad de los niños entre 69 años son usuarios autónomos. Además, cifran en un 30% el número de menores que utiliza redes sociales como Facebook. Otro dato preocupante es que los menores de 10 años expresan haber conocido físicamente a un amigo virtual, comportamiento apreciable en el 50% de los niños y en el 33% de las niñas. Si bien Internet es una herramienta útil para el desarrollo de los menores, algunos especialistas (Bringué & Sádaba, 2008; Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011; García & Bringué, 2007; Garmendia, Casado, Martínez & Garitaonandia, 2013; Livingstone, 2013) han presentado los riesgos de la exposición a Internet sin la compañía ni la formación adecuada, como violencia, pornografía, adicción y ciberacoso, entre otros.

Otro medio utilizado por los niños es la televisión. Se podría pensar que la irrupción de las tecnologías que permiten interactividad, ubicuidad y movilidad, reemplazarían su uso. Sin embargo, un estudio reciente, elaborado por Mediametrie y Eurodata TV, para la octava edición de «Kids TV Report: Trends & Hits in Children’s Programming in France, Germany, Italy, Spain & the UK» (2013), de Mediametrie y Eurodata TV, señala que el consumo televisivo diario de los menores europeos entre 4 y 12 años durante el año 2012 es de 2 horas 16 minutos. Mientras que los resultados de las investigaciones chilenas (CNTV, 2010; CNTV, 2012a; CNTV, 2012b) apuntan a que el consumo televisivo promedio de los niños entre 412 años es de cuatro horas diarias. Si bien esta cifra supone prácticamente el doble que la de sus coetáneos europeos, lo inquietante es que el 78,2% consume programación para adultos. Sobre este tema, diversos autores destacan que el acceso a contenido inadecuado puede derivar en problemas conductuales por la falta de formulación de temáticas y estructuras apropiadas, la escasa madurez y capacidad de asimilación de los menores. Por otra parte, el uso de los videojuegos es una práctica muy extendida entre los niños. Son programas de ocio multiplataforma (ordenador, consolas, móviles) (García & Bringué, 2007), cuya variedad de estructura narrativa y esquemas de interactividad permiten al usuario adaptarse a su ritmo y estilo (Rangel, LadróndeGuevara, Goncalves & Zambrano, 2011). Esto mismo ha permitido a los niños y niñas acceder a los videojuegos precozmente. Así lo demuestra el estudio de Lloret, Cabrera y Sanz (2013): en España el 90% de los menores entre 69 años juega con videojuegos. En Chile, un 57% de los niños tiene esta afición (Bringué & Sádaba, 2008). Sobre la edad y sexo de los videojugadores chilenos, Bringué, Sádaba y Tolsá (2011) concluyen que a los 6 años de edad, el 70% ya es usuario, sin evidenciar diferencias en función del sexo, mientras que entre los 710 años esta cifra aumenta en los niños y disminuye en las niñas. Es importante destacar que a través de esta actividad se potencia la adquisición de competencias digitales, las cuales favorecen su vinculación con el ámbito educativo. Algunos estudios señalan que los videojuegos poseen cierta carga de violencia cuya exposición reiterada puede derivar en: aumento de hostilidad, falta de empatía e incremento de agresividad (Rojas, 2008), pero quizás sean otras las variables que contribuyan al aumento de la agresividad en los niños.

Finalmente, en los últimos años el teléfono móvil ha llegado a formar parte de la vida cotidiana de los menores: «En Europa, uno de cada tres móviles está en manos de un menor de edad. En España, la mitad de niños/as entre 11 y 14 años dispone de él» (García & Bringué, 2007: 111). En esta misma línea, el estudio transnacional realizado en Japón, India, Indonesia, Egipto y Chile (Livingstone, 2013), indica que: un 65% de los menores entre 1018 años tiene acceso a un teléfono móvil, el 81% posee un móvil nuevo y el 20% tiene «smartphone». En Iberoamérica más de la mitad de los niños entre 69 años es usuario de la telefonía móvil (Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011). En Chile, los estudios concluyen que los menores tienen su primer móvil alrededor de los 10 años. No obstante, entre los 69 años el 54% ya es usuario, cuyas principales actividades son jugar y hablar con porcentajes similares entre niños y niñas (Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011; Livingstone, 2013). Esto corrobora que el uso del teléfono móvil por parte de los niños chilenos se inicia precozmente. Por tanto, es fundamental que los adultos promuevan pautas de uso seguro y responsable con el fin de evitar riesgos como: adicción, ciberacoso, «grooming», «sexting», entre otros.

1.2. Mediación parental y TIC

La masificación del uso de las TIC durante la última década ha producido una serie de cambios sociales. Prueba de ello es que desde la literatura la generación actual recibe diversas denominaciones: nativos digitales, «esociety», generación «touch» y generación «multipantalla» (MacPake, Sthepen & Plowman, 2007; Prensky, 2011). Estos menores han crecido utilizando las TIC, mientras los adultos han aprendido sobre la marcha, ocasionando una brecha digital entre ambas generaciones. Probablemente, el desconocimiento sobre el efecto del uso de las TIC sea el motivo de la escasa preocupación de algunos padres, quienes se limitan a controlar el tiempo y obvian contenidos que requieren mediación parental (Garitaonandia & Garmendia, 2009; Garmendia, Casado, Martínez & Garitaonandia, 2013; Livingstone, Haddon, Görzig & Ólafsson, 2010). En esta línea, el estudio realizado en Chile (Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011) concluye que un 50% de los niños afirma ser preguntados por sus padres sobre las actividades que realizan en Internet, mientras que un 36% considera ser vigilado por sus progenitores a la hora de navegar. Asimismo, admiten que las actividades prohibidas en Internet son: compras online (47%) y dar información personal (46%). Por otro lado, actividades como chatear, descargar archivos y jugar son prohibidas a un 7% de los menores. Finalmente, solo el 3% de los encuestados afirma que sus padres les prohíben acceder a una red social. Por lo anterior, adquiere gran importancia la mediación parental debido a que los padres establecen criterios de seguridad y responsabilidad para el uso adecuado de las TIC e influyen en el desarrollo y adquisición de conductas apropiadas en el uso de las TIC (Livingstone & Helsper, 2008).

2. Material y métodos

2.1. Muestra e instrumento

La muestra es de tipo intencionada y corresponde a N=422 (el 50,5%, varones; el 49,5%, mujeres) entre 912 años, con una media de 9,8 años y una desviación típica de 0,906 años. La media en varones es de 9,86 años, con una desviación de 0,931. En mujeres, los valores son 9,74 y 0,878, respectivamente. Pertenecen a 4°, 5° y 6° básico de 5 colegios privados de Santiago de Chile.

Se elaboró un cuestionario en el que se recopiló la siguiente información: datos sociodemográficos (edad, sexo, curso, colegio); uso de las TIC que hacen los niños/as de 912 años (frecuencia semanal, ubicación, compañía y tiempo); mediación parental percibida en el uso de las TIC (horarios, actividades, y riesgos).

2.2. Diseño

Es un estudio de carácter exploratorio mediante metodología «ex post facto» descriptiva por encuesta, de tipo empírico analítico. Antes de aplicar el cuestionario, se sometió a una prueba de fiabilidad. La que arrojó a=0,87, considerada satisfactoria. Fue validado por dos especialistas y se procedió a aplicar la prueba piloto a 30 niños/as para modificar las preguntas que inducían a error. La versión definitiva se aplicó durante el año escolar 2013, los participantes respondieron el cuestionario en sus clases de forma anónima, previo consentimiento de sus apoderados.

3. Análisis y resultados

Se efectuó un análisis estadístico descriptivo con frecuencias y porcentajes utilizando el programa estadístico SPSS (versión 21.0). Para contrastar las variables independientes (edad y sexo) se realizó la prueba de ?2.

3.1. Uso de las TIC que hacen niños y niñas de 9 a 12 años

En la tabla 1 se presenta la información proporcionada por la muestra, sobre la frecuencia semanal, lugar, compañía y tiempo de uso de las TIC. Los resultados evidencian que la mitad de los niños navega por Internet cualquier día de la semana, que más de un tercio realiza esta conexión desde cualquier lugar y, finalmente, la mayoría accede sin tutela. Un dato importante a destacar es la baja cantidad de menores que usa Internet en compañía de sus padres. Por otro lado, el tiempo de uso no presenta variaciones entre los menores que permanecen conectados sin límite de tiempo y aquellos que se conectan menos de una hora al día.

En el consumo televisivo, la gran mayoría ve televisión cualquier día de la semana y esta actividad es realizada preferentemente desde el salón del hogar, actividad realizada principalmente con la compañía de sus hermanos/as. Es importante destacar que el 37,2% afirma que ve televisión el tiempo que quiere.

Sobre el uso de los videojuegos, prácticamente no existen diferencias entre los menores que juegan cualquier día de la semana, aquellos que solo juegan los fines de semana y festivos, y quienes nunca juegan. Sin embargo, la mayoría realiza esta actividad en la sala de estar y principalmente sin compañía. Solo dos niños juegan con los padres. En el tiempo de uso diario, los resultados son homogéneos: el 29,6% indica que puede jugar menos de una hora, y el mismo porcentaje afirma que puede jugar el tiempo que quiera. El teléfono móvil es utilizado por más de la mitad de los niños cualquier día de la semana desde cualquier lugar y principalmente sin restricción del tiempo, sin embargo, es destacable que un 32,5% indique no usarlo.

3.2. Mediación parental percibida en el uso de las TIC

Respecto a la mediación parental percibida por los menores, los principales resultados se aprecian en la tabla 2.

Sobre la imposición de horarios, en las actividades relacionadas con el uso las TIC, la mitad de los menores indica no tener horarios para usar el ordenador y navegar por Internet y ver televisión. En este aspecto, la restricción horaria se evidencia preferentemente en el uso de videojuegos. Mientras que en actividades de la vida diaria (hacer deberes, dormir, comer y cenar), la mayoría indica tener horarios establecidos. En relación a las actividades que son permitidas en el uso de Internet, la mayoría de los menores indican que sus padres les conceden: entrar a redes sociales (Facebook), subir fotos y vídeos, descargar películas y vídeos, ver vídeos desde YouTube, estar mucho tiempo conectado y jugar online. Mientras que las actividades que les prohíben al navegar por Internet son: comprar, llenar formularios con datos personales y contactar con personas desconocidas.

Los resultados evidencian conductas de riesgo, acceder a redes sociales como Facebook, considerando que los sujetos de la muestra son menores de 13 años, edad mínima para crear un perfil en dicha página, a la que se accede mediante un formulario con datos personales. Además, en esta página es fácil contactar con desconocidos. Las otras actividades, como subir fotos y vídeos, descargar archivos multimedia, reproducir vídeos desde YouTube, estar mucho tiempo conectado y jugar online, conllevan ciertos riesgos, a saber: acceder a contenido inadecuado (violencia, pornografía), entregar información personal en la red, adicción y establecer contacto con desconocidos. Por tanto, existe una contradicción, de la cual se desprende cierto desconocimiento sobre los peligros que estas actividades implican en la vida de los menores.

Sobre los programas de televisión, la mayoría de los menores indica que sus padres les permiten ver programas en la noche, telenovelas y noticias. Por otro lado, los programas prohibidos consisten en programación adulta y de contenido altamente violento. En estos resultados se produce una dicotomía, ya que la programación permitida posee contenidos para adultos, además de presentar violencia explícita o implícita en algunos casos.

En cuanto a la mediación parental percibida en los videojuegos, es importante destacar la alta frecuencia de menores que señalan que pueden jugar solos, y más de la mitad indica no tener restricción parental para los juegos violentos. Por otro lado, se aprecian indicadores de conductas de riesgo, un 46,4% que afirma tener consentimiento parental para jugar mucho tiempo y un 31,5% manifiesta que puede jugar con desconocidos online. Por otra parte, la mayoría de los menores admite conversar con sus padres sobre los riesgos de las TIC. Esto ocurre con mayor frecuencia en cuanto al contacto con personas desconocidas.

3.3. Edad y sexo en el uso de las TIC

Para analizar la influencia de «edad» y «sexo», se realizaron pruebas Chicuadrado en tablas de contingencia, que prueban la asociación entre las variables estudiadas. Al emplear «edad» con cuatro categorías (9, 10, 11 y 12 años) no se cumplen las condiciones para realizar las pruebas (valores mínimos esperados de 5 por celda). Para resolverlo, se agrupa «edad» en dos bloques 910 y 1112 años, aunque cada categoría tiene dos edades y ello variaría el verdadero comportamiento entre las variables. Con esta agrupación, se cumplen las condiciones en la mayoría de las pruebas. A pesar de la significación estadística, es conveniente señalar que el 53,5% no son significativas. Al presentarse significaciones, estas debieran acentuarse al aumentar la muestra.

Al cruzar la variable «sexo» con puntuaciones de las TIC, el 96% no presenta significación. No obstante, existe un grado significativo en las actividades de «ver vídeos en YouTube» [(?2=4,170; GL=1; p= 0,041)], y la percepción de habilidades digitales que consideran tener respecto a su familia, amigos y profesores [(?2=8,056; GL=3; p=0,045)]. La significación en el caso de los varones es levemente superior al de las mujeres.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

Los resultados de las características de uso de las TIC analizadas (frecuencia, lugar, compañía y tiempo) evidencian que el uso de Internet es generalizado en los menores encuestados, la mitad de ellos accede cualquier día de la semana, y más de un tercio se conecta desde cualquier lugar. Esto refleja un cambio respecto al lugar de conexión en los últimos años. Este cambio se fundamenta en la masificación de los dispositivos 3G, los cuales aportan ubicuidad e hiperconectividad, características importantes para los menores de esta generación. Respecto a la compañía a la hora de navegar en Internet, el 58,3% admite que navega solo. Solo un 9,8% de los menores utiliza Internet en compañía de sus padres y además el 36,7% navega sin límite de tiempo. Ante esto se concluye que la exposición a Internet sin la supervisión y mediación parental presenta riesgos (Casado, Martínez & Garitaonandia, 2013; Livingstone, 2013).

En cuanto al consumo televisivo, los resultados indican que el 70% ve televisión cualquier día de la semana, aunque es importante señalar que esta actividad es realizada principalmente en el salón y son acompañados preferentemente por sus hermanos. Estos aspectos son beneficiosos para los niños, si el televisor se encuentra en un espacio común. Además, si están acompañados, existen menos posibilidades de que los menores accedan a contenido inadecuado. Sin embargo, el 37,2% afirma que ve televisión sin límite de tiempo, resultados que van en la línea de los publicados por CNTV (2012a).

Respecto al teléfono móvil, los resultados señalan que la mayoría de los niños posee un dispositivo móvil, que más de la mitad de los menores utiliza uno, cualquier día de la semana y desde cualquier lugar, y que lo hace principalmente sin límite de tiempo. Esto se corrobora con los datos aportados por Bringué, Sádaba y Tolsá (2011) y por Livingstone (2013), quienes reafirman la necesidad de la mediación parental en el uso del móvil debido a las conductas de riesgo que reflejan los datos obtenidos.

De acuerdo a la mediación parental percibida en el uso de las TIC, los resultados muestran que la mitad de los menores no tienen horarios establecidos por sus padres para usar el ordenador e Internet y ver televisión. Aunque, en el uso de videojuegos se evidencia restricción horaria. La fijación de horarios es fundamental para establecer límites, además de colaborar con el uso adecuado de las TIC, contribuye en la prevención de conductas de riesgo.

En relación a las actividades que pueden realizar en Internet con autorización parental, es de remarcar el alto porcentaje de niños con acceso a redes sociales (Facebook), «subir fotos y vídeos, descargar películas y vídeos, ver vídeos desde YouTube, estar mucho tiempo conectado y jugar online. Y por el contrario, no pueden: realizar compras online, rellenar formularios con datos personales y contactar con personas desconocidas». Esto resulta paradójico, porque si bien los menores no pueden entregar información personal y contactar con personas desconocidas, a la mayoría se le permite utilizar Facebook, red social en la que es necesario tener la edad legal correspondiente, se deben cumplimentar formularios con datos personales, y en la que es muy fácil contactar con desconocidos. Las otras actividades permitidas también presentan riesgos que van desde el acceso a contenido no adecuado, entrega de información personal, adicción y contacto con desconocidos. Esta información evidencia cierto desconocimiento frente a los riesgos que estas actividades implican en la vida de los menores, motivo por el cual debería impulsarse el diálogo familiar sobre los momentos y lugares idóneos de uso, y acordar la adecuación de contenidos digitales, servicios web y relaciones que puedan establecer (Berríos & Buxarrais, 2005; Buxarrais, Noguera, Tey, Burguet & Duprat, 2011).

Sobre el consumo televisivo, los menores afirman que sus padres les permiten ver programas nocturnos, telenovelas y noticias; mientras tienen vetados programas de adultos y violentos. Esto coincide con los datos entregados por CNTV (2012b). Se aprecia cierta contradicción en la información, debido a que los programas que pueden ver emiten contenido para adultos y en diversos casos presentan escenas de violencia. Esta desatención puede ocasionar desconocimiento de los menores hacia lo que ven, experiencia de emociones fuertes sin expresarlas y falta de desarrollo de una postura crítica frente a lo percibido. El aspecto positivo es que la mayoría ve televisión en espacios comunes, hecho que facilitaría la supervisión.

La mayoría indica conversar con sus padres sobre los riesgos derivados del uso de las TIC, tales como: contacto con desconocidos, daño por ver contenidos adultos y revisión de la fiabilidad de los documentos.

De acuerdo a las variables analizadas (edad y sexo), en los cuatro rangos de edad expuestos no existe diferencia en el uso de TIC, aunque se desprende una vinculación entre la edad y el uso. En la televisión y videojuegos, el espacio está estrechamente vinculado: preferentemente a zonas comunes del hogar. Al usar cada dispositivo hay una relación con la edad, el uso y la compañía. Usan las TIC principalmente solos. No se encontraron diferencias estadísticas significativas en función del género tanto en las características del uso, como en la mediación parental percibida por los menores, contradiciendo estudios anteriores (Bringué & Sádaba, 2008; Bringué & Sádaba, 2009; Bringué, Sádaba & Tolsá, 2011).

Constatamos que las TIC forman parte de la cotidianidad para la gran mayoría de los niños entre 912 años. La generación interactiva chilena supera la media respecto a otros países de la región, debido al acceso a todas las tecnologías (Bringué & Sádaba, 2008). Sin duda, se trata de una generación precoz en el quehacer tecnológico (Aguaded, 2011): en edad preescolar ya acceden a las TIC en su hogar (Plowman, McPake & Stephen, 2010; Plowman, Stevenson, Stephen & McPake, 2012; Plowman, Stephen & McPake, 2012; Lepicnik & Samec, 2013). Por su incidencia en el desarrollo cognitivo, se propone que las escuelas para padres promuevan la formación en el uso idóneo de las tecnologías, con una mirada segura, ética, integradora y responsable, de tal forma que puedan regular el tiempo de exposición de sus hijos frente a una pantalla y supervisar los contenidos de Ias TIC.

La limitación que presenta nuestro estudio es la aplicación del instrumento solo en colegios privados de nivel socioeconómico alto. Por ello, difícilmente los resultados se pueden extrapolar a la realidad de los colegios públicos y concertados, principalmente por la segmentación existente en la educación chilena. Como prospectiva, se plantea aplicar el cuestionario a niños/as de colegios públicos, concertados y privados, para establecer una comparación entre las tres realidades. Asimismo, se incluirá la parte cualitativa, considerando a las familias y el profesorado.

El estudio arroja aportaciones novedosas, respecto a la percepción de los menores acerca de la mediación parental en el uso de las TIC dentro del contexto chileno. Al tratarse de un trabajo de tipo exploratorio, constituye una primera aproximación a la realidad.

Referencias

Aguaded, I. (2011). Niños y adolescentes: nuevas generaciones interactivas. Comunicar, 36, 7-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C36-2011-01-01).

Area, M., Gros, B. & Marzal, M. (2008). Alfabetizaciones y tecnologías de la información y la comunicación. Madrid: Síntesis.

Berríos, L., & Buxarrais, M.R. (2005). Las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC) y los adolescentes. Algunos datos. OEI, 5. (http://goo.gl/cEJjtA) (10-02-2015).

Bringué, X., & Sádaba, C. (2009). La generación interactiva en España: Niños y adolescentes ante las pantallas. Barcelona: Ariel.

Bringué, X., & Sádaba, C. (Coord.). (2008). La generación interactiva en Iberoamérica 2008: Niños y adolescentes ante las pantallas. Barcelona: Ariel/Fundación Telefónica.

Bringué, X., Sádaba, C., & Tolsá, J. (2011). La generación interactiva en Iberoamérica 2010. Niños y adolescentes ante las pantallas. Madrid: Foro Generaciones Interactivas.

Buxarrais, M.R., Noguera, T., Tey, A., Burguet, M., & Duprat, F. (2011). La influencia de las TIC en la vida cotidiana de las familias y los valores de los adolescentes. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona/ Observatori Educació Digital.

Consejo Nacional de Televisión. (2010). Anuario de programación infantil: oferta y consumo. Santiago: Consejo Nacional de Televisión de Chile.

Consejo Nacional de Televisión. (2012a). Los padres y la regulación televisiva. Santiago: Consejo Nacional de Televisión de Chile.

Consejo Nacional de Televisión. (2012b). Encuesta niños, adolescentes y televisión: consumo televisivo multi-pantalla, control parental, identificación con jóvenes en pantalla. Santiago: Consejo Nacional de Televisión de Chile.

García, F., & Bringué, X. (2007). Educar hij@s interactiv@s. Una reflexión práctica sobre las pantallas. Madrid:Rialp/Instituto de Ciencias para la Familia, Universidad de Navarra.

Garitaonandia, C., & Garmendia, M. (2009). Cómo usan Internet los jóvenes: hábitos, riesgos, y control parental. (http://goo.gl/PNrTYk) (10-04-2014).

Garmendia, M., Casado, M., Martínez, G., & Garitaonandia, C. (2013). Las madres y padres, los menores e Internet. Estrategias para la mediación parental en España. Doxa, 17, 99-117.

Gutnick, A.L., Robb, M., Takeuchi, L., & Kotler, J. (2010). Always Connected: The New Digital Media Habits of Young Children. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop.

Lepicnik, J., & Samec, P. (2013). Uso de tecnologías en el entorno familiar en niños de cuatro años de Eslovenia. Comunicar, 40, 119-126. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-03-02

Livingstone, S. (2013). Children´s Use of Mobile Phones: An International Comparasion, 2012. GSM, 3. (http://goo.gl/DIZDyl) (10-02-2015).

Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. (2008). Parental Mediation and Children’s Internet Use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 52(4), 581-599.

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., & Olafsson, K. (2010). Risks and Safety on the Internet. The Perspective of European Children. Initial Findings from the EU Kids Online Survey of 9-16 Year Olds and their Parents. (http://goo.gl/NpjfvQ) (10-02-2015).

Lloret, D., Cabrera, V., & Sanz, Y. (2013). Relaciones entre hábitos de uso de videojuegos, control parental y rendimiento escolar. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 3, 249-260.

Mcpake, J., Stephen, C. & Plowman, L. (2007). Entering E-Society. Young Children’s Development of E-Literacy. University of Stirling (http://goo.gl/sZk6BW) (13-04-2012).

Mediametrie, Eurodata TV. (2013). Kids TV Report: Trends & Hits in Children’s Programming in France, Germany, Italy, Spain & the UK. (http://goo.gl/4VOlbb) (17-01-2014).

Plowman, L., Mcpake, J., & Stephen, C. (2010). The Technologisation of Childhood? Young Children and Technologies at Home. Children and Society, 24(1), 63-74.

Plowman, L., Stephen, C., & Mcpake, J. (2012). Young Children Learning with Toys and Technology at Home. Research Briefing, 8 (http://goo.gl/fY9Yxk) (10-02-2015).

Plowman, L., Stevenson, O., Stephen, C., & Mcpake, J. (2012). Preschool Children’s Learning with Technology at Home. Computers & Education, 59(1), 30-37.

Prensky, M. (2011). Enseñar a nativos digitales. Madrid: SM.

Rangel, A., Ladrón-De-Guevara, I., Goncalves, I., & Zambrano, L. (2011). Los videojuegos en ambientes de desarrollo infantil y juvenil: propuestas para definirlos, clarificarlos y aprovecharlos como entornos de investigación psicológica. Psicología, 30(2), 15-29.

Rojas, V. (2008). Influencia de la televisión y videojuegos en el aprendizaje y conducta infanto-juvenil. Revista Chilena de Pediatría, 79, 80-85. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S037-41062008000700012

Sádaba, C., & Bringué, X. (2010). Niños y adolescentes españoles ante las pantallas: rasgos configuradores de una generación interactiva. CEE Participación Educativa, 15, 86-104. (http://goo.gl/cNkeCd) (12-08-2011).

Document information

Published on 30/06/15

Accepted on 30/06/15

Submitted on 30/06/15

Volume 23, Issue 2, 2015

DOI: 10.3916/C45-2015-17

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?