Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Los jóvenes viven hoy en una cultura multimedia donde los contenidos a los que acceden y hacen circular a través de diferentes dispositivos tecnológicos audiovisuales, forman parte de su educación informal. En ese contexto, la publicidad clásica inserta en esos medios de comunicación está dando paso a nuevas estrategias en las que la publicidad se enmascara en otros contenidos dirigidos a los jóvenes. Estos creen estar suficientemente bien informados para considerar que la influencia de la publicidad sobre ellos es relativa y afirman estar dotados de eficaces estrategias que les inmunizan contra ella. Sin embargo, como se argumenta en el presente artículo, la actual publicidad está implementando nuevas formas persuasivas que no perciben. Se presenta una investigación empírica en la que participan 154 estudiantes. Mediante un dispositivo informático interactivo procesan un total de 223 estímulos correspondientes a un medio de comunicación gráfico. Como variables dependientes se recoge el grado de acierto en la identificación de la presencia de publicidad en los estímulos y el tiempo de reacción. Los resultados muestran cómo las nuevas estrategias de enmascaramiento en publicidad evitan la toma de conciencia de los jóvenes de estar recibiendo mensajes publicitarios. Ello favorece que éstos no contraargumenten. Estos resultados abren la discusión de la pertinencia de dar a conocer a los jóvenes, en su proceso educativo, estas actuales estrategias publicitarias eficaces provenientes de los sistemas de educación informal.

1. Introduction: from traditional advertising to masked advertising

At the beginning of the 21st century, it seemed that advertising had been sufficiently unmasked by young people. Its explicit messages, located in spaces that were perfectly defined in the media, were sufficiently well-known and identifiable by young people, given the informal learning about its codes they had received since infancy. Knowing where the advertising was allowed them to develop their counter-arguments to thus attempt to deflect any possible persuasive influence. As Kapferer (1985: 34) concluded, from a review of empirical studies, «the child acquires, from the age of three, the codes that allow it to differentiate what advertising is from what it is not». However, things have been changing at an accelerated pace in the last few years. Advertising is modifying the way it targets young people. Its renewed efficiency is enhanced by the current context of young people's relationship with technical and technological devices. In this multi-screen cultural environment (Pérez-Tornero, 2008), with bidirectional and multidirectional communication, certain features stand out which contribute to configuring their informal education. In the first place, young people's lives are immersed in a culture of audiovisual entertainment (Martínez, 2011). They use the media to get information, but especially for entertainment, acting with confidence as, in general, they consider that the content serves for enjoyment, not for persuasion (Shrum, 2004; Nabi & Beth, 2009; Sayre & King, 2010). In the second place, and fostered by new technologies, there is a framework of cognitive hyperstimulation (Klingberg, 2009). It is enough to imagine the stimuli received by a passer-by today in a city in comparison with those he or she would have received at the beginning of the last century (Bermejo, 2011a). Thirdly, the aforementioned phenomenon of cognitive hyperstimulation is accompanied by an increase in multitasking or dual-tasking. One of the consequences of being online often is that the amount of stimuli reaching young people today is greater than it was a few years ago (Klingberg, 2009). At the current time, it is not unusual to see young people focusing on their mobiles while they do other school activities or being interrupted by the sudden arrival of a message on their telephones, or to see university students who are attending their classes and at the same time consulting their computers in front of them, connected to the Internet (Jeong & Fishbein, 2007). This set of phenomena has introduced into the lives of young people new ways to mobilise different types of attention. The duration of voluntary or controlled periods of attention, which depends on a conscious effort to carry out a task (for example, paying attention in class or studying) is reduced by the arrival of external stimuli, which are increasingly abundant, which interrupt this period and give rise to stimulus-driven attention. This latter situation leads us to change our current focus of attention to another focus which breaks into our receptive stimuli field. Given that our processing abilities are limited, the working memory has to share its scant resources among several stimulations, thus diminishing its capacity to process with total relevance all the stimuli it is dealing with simultaneously. One detail provided by this current research is that the fuller the working memory, through having to deal with several stimuli at the same time, the greater the difficulty involved in concentrating through controlled attention, and the greater the chances of becoming distracted and of processing in a superficial manner the stimuli that are competing among themselves to get our attention (Ophir & al., 2009; Heylighen, 2008). This multi-stimulation cultural context creates attention-related habits that later affect the attention-related processes required by formal education at school, and explains in part the observations of certain teachers who complain about the current inattention levels of their students over prolonged periods.

Within this cultural framework, advertising, which has seen how the attention paid to its messages has been decreasing in conventional media, has been searching for new ways to attract the attention of consumers (Heath, 2012). It is directing its greatest efforts and attention towards new media, particularly the Internet, in so-called post-advertising society (Solana, 2010). These new marketing strategies have drawn the attention of researchers, partly due to the innovative aspect of these strategies and also because young people are exposed to them through the Internet, social networks (Sanagustin, 2009) and new activities consisting of audiovisual virtual entertainment (Martí, 2010). This is making that fact that conventional media, which continue to feature strongly, are also evolving become forgotten. They are in pursuit of new strategies to manipulate attention and thus attract their targets through renewed forms of persuasion. Please remember that traditional, or classic, advertising, inserted into conventional media, has used, throughout the 20th century, a persuasive strategy aimed at grabbing the conscious, voluntary attention of its targets. It considered that once it had managed to attract their attention to its message, the content thereof could persuade them. This type of advertising, which is still chiefly in force today, has certain well-defined features. One of the most characteristic features is its clear demarcation of genre. Its insertion in a restricted space in the media that contains them means that there is no mixing of genre. In the press, on the page there is a framed space for advertising which is thus separated from the news and reports. On the radio or television, there are also blocks for advertising with well-established codes that are learnt from the earliest years of childhood (Minot & Laurent, 2002; Dagnaud, 2003, Gunter & al., 2005). A second feature of classic advertising is that it simulates a two-way or dialogic process (Bajtin, 1991; Linell, 1998, Adam & Bonhomme, 2000). Dialogue in daily life implies two-way communication between those speaking and the participants in the dialogue. However, advertising can only send one-way messages through conventional media and therefore cannot establish, in the strictest sense, two-way communication and, therefore, real dialogue. Nonetheless, this has not prevented advertising from simulating direct dialogue with its public as if there were really bidirectional communication (Bermejo, 2013a).Together with this classic advertising, a new type of advertising is currently appearing. Recently we have been able to identify a new persuasive advertising strategy in current graphic communication media, which we have called «masking» and which until now had not been detected (Bermejo & al., 2011). Masking implicates our attention in a different manner to the manner which advertising had been using thus far, by targeting involuntary attention as opposed to voluntary attention. This strategy is characterised by the deletion of genre codes, by the hybridisation of genre by inserting and concealing advertising in other communicational genres, and, in third place, by the staging of a new dialogism (Bermejo, 2013a). In this initial research, we have identified the presence of three types of new graphic advertising in the written media in Spain which comprise three manifestations of this persuasive strategy of masking. We have named them embedded advertising, neoadvertorials and self-referent advertising.

These three modalities of masking advertising are characterised in this manner because the subject accesses an informative text incorporating an advertising message which, since that message is not highlighted or demarcated by codes which establish it as an independent text, is concealed within the text containing it. An example of embedded advertising can be found in interviews with celebrities and public figures. In the article, as the interviewee answers the questions posed by the interviewer, the celebrity recounts aspects of his or her life which include, in these cases, him or her alluding to using specific products and brands. Secondly, although advertorials were already being used in below-the-line advertising, there are two features of neoadvertorials that differentiate them from advertorials. One is that the genre-identifying code, which is found in the heading of the page or within the frame for the advertising text («special promotional feature», etc.) and which warns the reader about the content, disappears. A second feature is that neoadvertorials present themselves to the reader under the appearance of real articles attempting to inform the reader about a specific issue of their interest (e.g. how to make a festive meal, what presents to give or how to fight hair loss, etc.). Throughout the text, allusions are be made to products and brands that can help the reader to solve their problem or meet their need for information. Therefore, the advertising message appears in this type of text at a precise moment and by way of a suggestion that will serve the reader when deciding on the issue that led him or her to read the article. Finally, as in the previous case, self-referent advertising erases the codes that allow the reader to perceive and immediately classify the text as belonging to the promotional genre or as conventional self-promotional texts. While in traditional or classic advertising self-promotion meant an explicit text which invited the reader to consume the product or service, in this new, self-referent advertising a text is offered that is of interest to the reader into which self-promoting messages, through icons or text, have been slipped. For example, in «Cosmopolitan» magazine (nº 243; pages 82-93), which has been included in the empirical research detailed later on in this text, the reader finds photographs and descriptions of a party attended by numerous public figures, singers and actors, among others. As a background to several of the photographs where the celebrities are posing for the cameras, the logotype of the organiser of the event can be clearly seen, i.e. Cosmopolitan magazine, as well as explicit references to the brand. Even though the accent in the article is placed on the glamorous aspects of the event and on satisfying the possible curiosity of the reader as to, among other things, the dresses and attire of the guests, the party is subtly accompanied throughout by the sponsoring brand which made the event possible (Bermejo, 2013a).

This new strategy of masking advertising, through these three modalities we have been able to identify, targets involuntary attention, unlike traditional advertising which targets voluntary attention. The question arises as to how young people react to this type of advertising strategy and the potential persuasive influence it can have on them. In this article, we present the results of a study which investigates for the first time, taking an empirical approach, the influence on young people of this new advertising strategy.

2. Experimental study of masking advertising

2.1. Material and methods

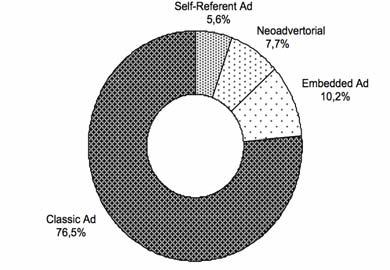

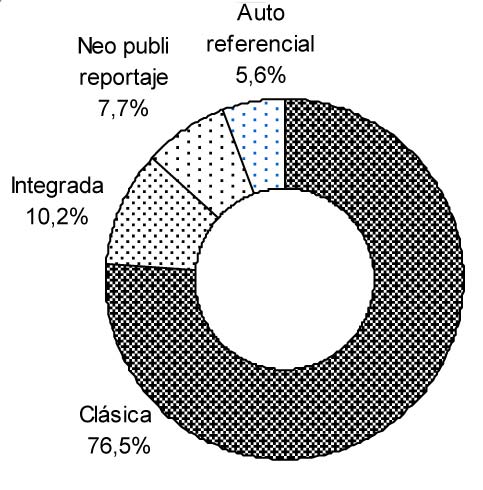

In a previous study, in 2011, we investigated the presence of new, graphic advertising within advertising in Spain as a whole. Having analysed all the types and categories of publications in the Spanish market which insert advertising and which can be bought at newsagents and bookshops, a representative corpus was selected that covered 232 publications, with a total of 26,930 pages, of which 7,183 included advertising, making a total of 7,771 adverts (Bermejo, 2011d). Analysing this corpus of adverts revealed that this new strategy of masking advertising is already present to a certain extent in the press and represents a quarter of the total, adding together the three manifestations of the strategy (embedded advertising, neoadvertorials and self-referent advertising) (Bermejo, 2011c).

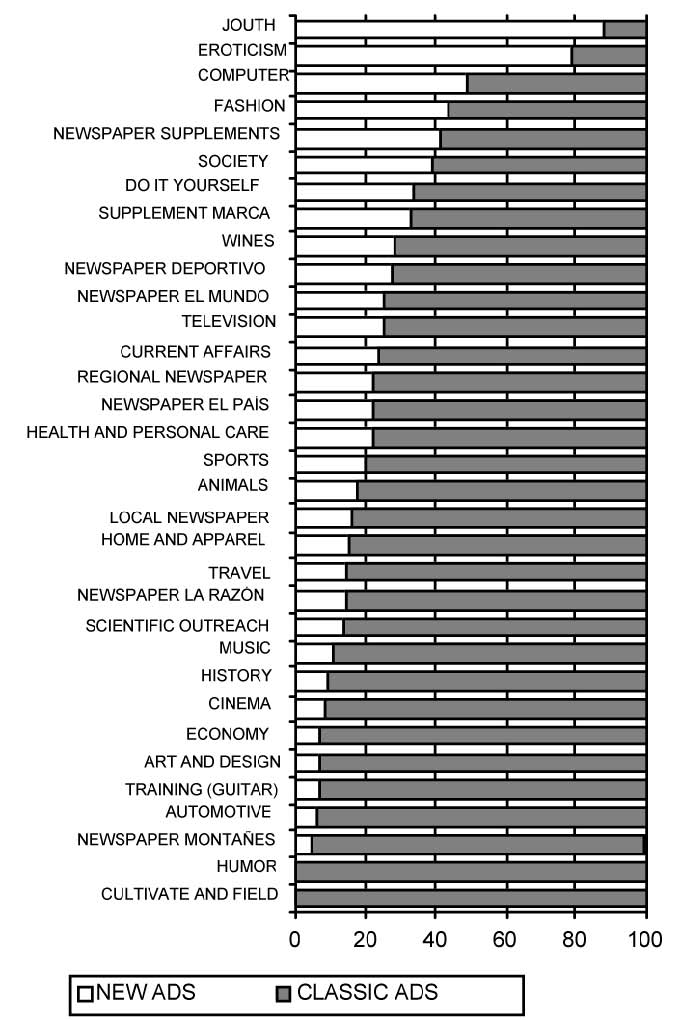

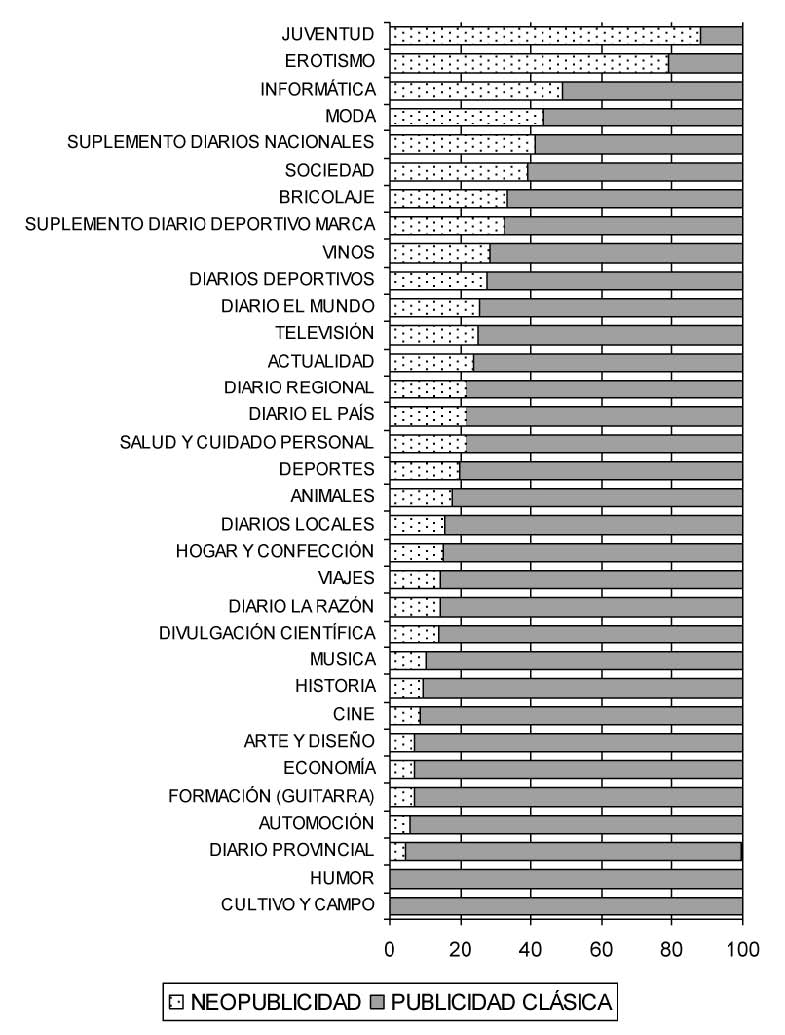

As can be seen in Figure 2, even when the three new advertising modalities (neoadvertising) appear in the majority of the publication categories, it is interesting to observe that they are concentrated above all in certain categories with common elements: Youth (which includes magazines such as «Loka Magazine», «Super Pop», «Ragazza», «Bravo por Ti», etc.) reaching 87.9% of the total number of adverts in the publications included in this category, Eroticism (79%), Fashion (with publications such as «Elle», «Tendencias», «Glamour», «Vogue», «Telva», etc.), representing 43.6%; Newspaper Fashion, such as «Dona», representing 41.1%, and Society (with over twenty publications including «Lecturas», «Cosmopolitan», «Pronto», «Hola») reaching 39.2%. These five categories of publications have to do with relations among individuals in a social setting, with trends, values and social uses. Many of these include patterns of conduct, values and social actions with which the advertising is associated, in accordance with the camouflaged style of the three modalities of new advertising described above. Therefore, this new persuasive strategy already has a significant presence in graphic advertising and is found in practically all publication categories. An interesting conclusion arising from this study is that masked advertising appears significantly in publications read by young people. A general aim suggested by this result is to find out if this new type of advertising influences them.

2.2. Objectives

The overarching objective of the study is to assess if the subjects, after being asked to look at a magazine (on sale at newsagents and bookshops) which inserts advertising, perceive and identify with the same degree of difficulty the four types of advertising, namely classic advertising, embedded advertising, neoadvertorials and self-referent advertising. It concerns finding out it the factor of masking, which is missing in classic advertising and present through different forms of expression in the other three types of advertising, has any influence on their ability to identify the presence of advertising in those pages. The masking has been used as an experimental technique to differentiate the conscious and unconscious processing of stimuli (Froufe & al., 2009). In our case, we understand masking to be that process used not in the laboratory but in the social environment by a new type of advertising, which consists of erasing genre markers, including the advertising message within the text of another informative genre which contains it and, thirdly, establishing a type of specific dialogism, described above in this text.

For this study, the «Cosmopolitan» magazine was selected as stimulatory material. This magazine belongs to the category of publications about society and was chosen because it contains abundant examples of classic advertising and new advertising and, in addition, because it is part of a general category of publications, together with publications for young people, that young people today read on a regular basis.

2.3. Experimental procedure

A total of 154 university students in the final year of their degrees in advertising and public relations, aged between 21 and 23 years old, took part in the study. The sample, made up of young men (24.7%) and young women (75.3%), was selected as it was deemed an expert group that is familiar with advertising messages in the media. Therefore it was to be expected that they would have no difficulty identifying advertising in conventional written media.

In the experimental situation, the participants performed the task individually on a computer onto which the program SuperLab 4.1, had been loaded, allowing the user's responses to be recorded. During the session, the subject visualised 224 screens corresponding to each of the pages, including the cover and back cover, of issue number 243 of the society magazine known as «Cosmopolitan». The task indicated in relation to this independent variable is that the subject presses the letter «S» key if the page being viewed contains advertising or the letter «N» key if the page does not contain advertising. When a response is entered, the program moves on to the next screen, and so on. Before starting, and in relation to the dependent variables taken into consideration, the subject was informed that both the accuracy of the response in identifying the presence of advertising on the page and the time taken to respond (Reaction Time in milliseconds, recorded by the software installed on the computer) will be taken into account.

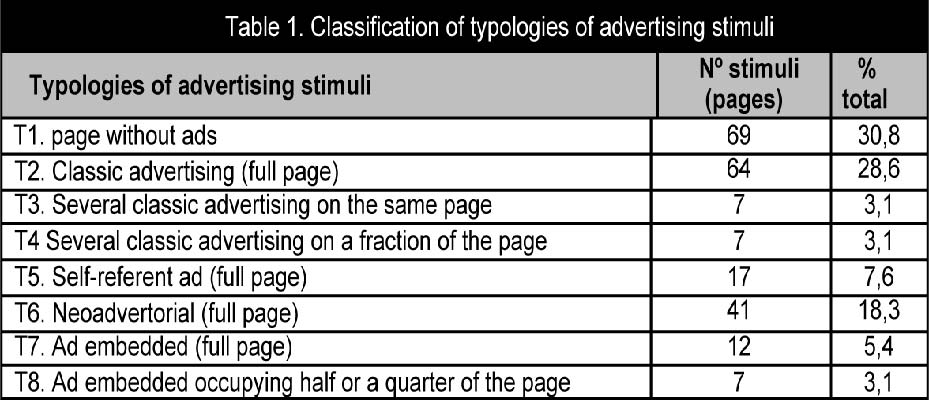

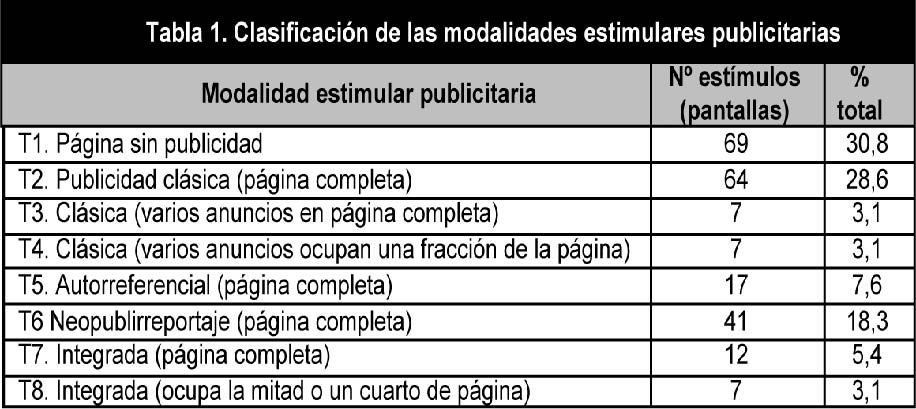

A prior selection and classification of the advertising in the magazine found a total of 155 advertising stimuli (i.e. 155 of the 224 screens contained advertising). Those 155 stimuli were classified under 7 typologies or modalities of advertising, resulting from taking into consideration two variables of the stimulus: a) type of advertising and b) amount of space taken up by the advert on the page. Table 1 contains the breakdown of the 224 pages of the magazine based on those two criteria. Categories T2, T3 y T4 correspond to stimuli including classic advertising. The following four categories (T5 to T8) correspond to the three types of new advertising. These four types include self-referent advertising, advertorials, embedded advertising within full-page text and, finally, embedded advertising partially within the text occupying half or a quarter of a page.

To keep the experimental design balanced with respect to the number of stimuli, seven pages corresponding to each of the seven categories of advertising stimuli were used in the statistical analysis, with the exception of the category of a page including a quarter with five items.

2.4. Hypothesis

The general hypothesis is that there is a differential perception between the four types of advertising described above.

H1: Classic advertising is noticed better that new advertising (self-referent advertising, neoadvertorials and embedded advertising), that is, accuracy in identifying classic advertising is greater than that of identifying masked advertising. This implies that, as the accuracy rate for identifying classic advertising is greater, part of the new advertising goes unnoticed.

H2: The subject takes less time to identify classic advertising than he/she does with new advertising. This second, supplementary entry illustrates the difficulty experienced by the subject in perceiving the masked advertising in the graphic text.

3. Results: the efficiency of persuasion of masked advertising in relation to young people

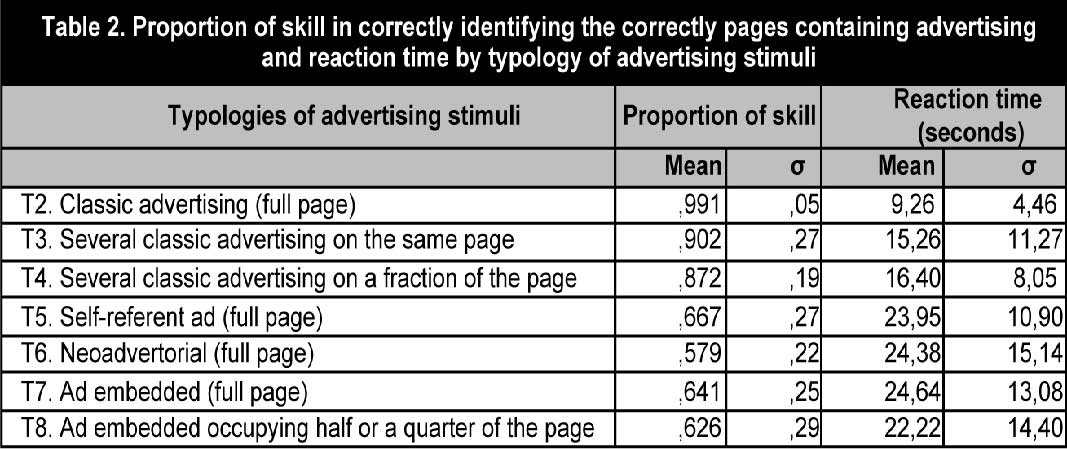

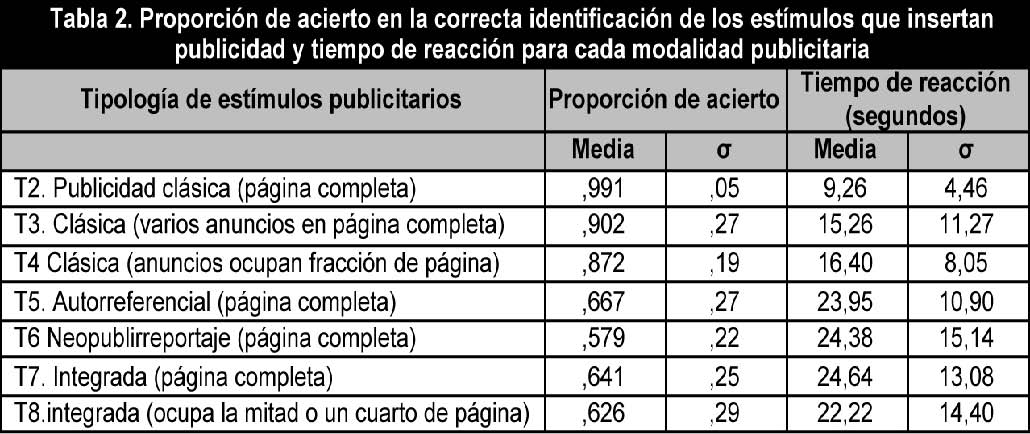

The first analysis has been done on the proportion of skill in correctly identifying the pages containing advertising. The advertising method shows clear differences in the proportion of people who correctly identify the presence of advertising in the pages of the magazine. The first two typologies of advertising, T2 and T3, are correctly identified in 99.1% and 90.2% of the cases (table 2). With a slightly lower rate of correct answers is the advertising that occupies a fraction of the page, which obtained an 87.2% correct identification rate. Therefore, these are advertising categories that cause us no type of trouble in classifying them as advertising, and they could be called classic advertising. The other four categories of stimuli, which correspond with masking ads, show a proportion of correct responses that is appreciably lower, as can be seen in the table. Self-referent advertising has a 66.7% correct identification rate, neoadvertorials obtain 57.9%, and advertising embedded in the text obtains 64.1% and 62.6% respectively. The four typologies represent advertising stimuli in formats or manners of presentation that are less evident in the classification of advertising. To create a record of the differences, a within-subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA) has been carried out and it has been verified that these differences are statistically significant (F=150.85, sig.=.000). Therefore, hypothesis 1 is confirmed and brings up a different perception between the two types of advertising.

The reaction time is the second variable recorded in the analysis and reflects the degree of processing required to give a response for each stimulus. In table 2, the results obtained are shown for each type of stimulus. An increase can be seen in the average time devoted to the processing of the image before giving a response as the stimulus passes from classic advertising to new advertising. In the full-page adverts the average time was 9.26 seconds, the category that contains several adverts on the same page obtained a slightly longer average processing time (15.26 seconds), and this was somewhat higher in the following category (16.40 seconds). The other four types of remaining stimuli, which corresponds with new advertising or masking ads, show a substantial increase in the time devoted to the processing, given that the average reaction time was situated between 22.2 and 24.64 seconds. Once again, a within-subjects analysis of variance, ANOVA, has been carried out and it has been discovered that the differences between the seven categories are statistically significant (F=189.3; sig.=.000). In fact, a second within-subjects analysis of variance carried out on the last four advertising categories does not show statistically significant differences (F=2.687; sig.=.055). Therefore, the analysis of this second variable shows that the decrease in the rate of correct responses for the advertising categories called neo-advertising is not due to a lack of attention, given that clearly the subjects have spent more time in giving a response. Therefore, it can be deduced that the difficulty of classifying these pages has required greater cognitive resources from the participants in the study.

4. Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study give rise to a debate about four issues. The first issue refers to the shift in persuasive strategies used by advertising to communicate with young people and which would be changing from targeting the conscious to targeting the subconscious. It is necessary to remember that subconscious is not the same as subliminal. The latter type of stimulation operates under the level of sensitive processing and, as is apparent in the study and meta-analysis, the influence of subliminal advertising on consumer decisions is not significant (Moore, 1982; Trappey, 1996). However, a subconscious process takes place when the advertising can be seen or heard, even if it does not attract the attention of the subject (Heath, 2007: 22). Unlike subliminal advertising, studies like that of Shapiro, Macinnis and Heckler (1997) have empirically confirmed that the subconscious processing of advertising can influence purchasing decisions.

Until recently, there was a notion that we assimilated only that which had passed through our conscious minds. This meant that advertising strategy sought to attract the conscious attention of its public. It was thought that what was retained through this channel could be recovered from memory and thus have an influence on favourable attitudes towards the brand, whereas that which was not processed by this voluntary channel was lost and did not influence our subsequent behaviour. According to this model, the interpretation of the results of this study would be that masked advertising would not be efficient, that is, would not influence the reader's mind, given that it had not been perceived in a conscious manner. However, recent breakthroughs in psychology and neuroscience have demonstrated that there are three forms of processing the stimuli that can later influence our behaviour (Klingberg, 2009; Heath, 2012). There is active learning, which occurs through high-attention, fully-conscious thinking, which commonly uses the foveal system. Secondly, there is passive learning, occurring through a low-attention focus, which uses above all the parafovea. Lastly, a third type of peripheral attention, which leads to so-called implicit learning, which occurs without the subject paying attention to the stimulus of any of the other two forms of attention. According to this third type of learning, the subject may not be aware of having perceived a stimulus and, despite this, may have assimilated it both sensorially and conceptually (Shapiro & al., 1997). In the light of these advances in knowledge about attention and learning processes, which indicate that implicit learning can occur through low attention and peripheral attention, the interpretation of the results of this study can be addressed from the perspective of possible future persuasive effects on young people. Given the context of exposure, where the subject is explicitly invited to look at images on a screen and make decisions regarding these, we have a task where the requirements for general processing are conscious and voluntary, requiring high attention in top-down processing controlled by the objectives (Eysenk & Keane, 2000: 2). However, the interesting thing is that, despite this particular context, a significant part of the subjects process the stimuli with low attention levels. It is as if, in fact, the effective processing had followed a bottom-up processing strategy in which the learning occurs unnoticed and is controlled by the stimuli and not by the subject’s objectives. This explains errors committed by the subjects which, if their level of attention had been increased, would not have occurred given their prior level of expertise in advertising. The incorrect verbal response given by our subjects indicates that they have not sufficiently processed the presence in the stimulus of a considerable part of the masked advertising. However, this does not mean to say that they have not processed it. That would have occurred either with a low attention level or even at a subconscious level, through peripheral attention. As scientific literature, through the study of the priming effect, has been able to show, stimuli processed through implicit learning can have a subsequent effect on behaviour, although this does not manifest itself through a conscious effort to recover the information (Harris & al., 2009). Therefore, this shift in strategy experienced in advertising, which is leading it to change from using strategies targeting the conscious mind to using strategies aimed at the subconscious mind and implicit learning, can be highly efficient as regards advertising since, as we have demonstrated here, these strategies go unnoticed by our subjects.

The second issue that arises from these results is that they reveal a new type of relationship with the reader. The dialogism of classic advertising has been using a process of direct dialogue. Once the reader's attention has been grabbed, from then on classic advertising deploys argumentative strategies focusing on the source and the message, where the enunciator offers a promise about a brand/product (Bermejo, 2011 b). Conversely, the type of masked advertising we have identified uses another form of dialogism. Within it, communication is undertaken around a matter or subject of information that interests the reader. In this process, this being the centrepiece of the communication, the product or brand is shifted, although not absent. Simulated dialogue in traditional advertising is replaced in masked advertising by a dialogic meeting around content attracting the reader (Bermejo, 2013a). At the same time, in this new communication context, the rational-emotional dichotomous axis fades into the background in favour of attention processes and conditioning processes, according to the mechanism already described by Paulov and reaffirmed by contemporary psychology and neuroscience (Health, 2012). As Health has demonstrated experimentally, the issue is no longer about advertising being more rational or emotional, but about the perceptive context in which exposure to advertising which induces a specific degree of processing and counterarguing (Heath & al., 2009).

In third place, if, as these results indicate, the masking strategy means that advertising in the media passes unnoticed to the conscience, individuals can end up with the impression that advertising, which was extremely invasive in the last years of the 20th century, is beginning to move beyond the media. However this, as we have seen, would be nothing but an illusion as it continues to be present. One of the consequences of this lack of perception is that the individual relaxes and does not become defensive or create counterarguments against the masked advertising messages. As we have known for some time, counter-argumentation is a powerful mediating variable in the message acceptance response (Wright, 1980; Knowles & Linn, 2004; Petrova & al., 2012). When the subject uses a counterargument, the likelihood of being persuaded is reduced as the subject's cognitive response runs contrary to the arguments offered by the advertising message. The deployment of the masking stratagem in other media can, paradoxically, lead to advertising persuasion becoming even more efficient in the future than nowadays since the subject, as he or she does not perceive the stimuli consciously, does not see the need to counterargue.

Fourthly and finally, and no less importantly, a reflection emerges from this study about the media literacy of young people in this new era of multichannel communication. The rediscovery of the so-called cognitive unconscious (Hassin & al., 2005; Froufe & al., 2009) has made us see that we are also capable of processing information presented peripherally, without being aware of it. If this study is an illustration of that phenomenon, this new knowledge about our capabilities, already used by advertising, suggests the possible need of making known to young people these sales procedures, which target not conscious attention but peripheral attention, so that they can, based on this knowledge, make their own individual decisions with a greater degree of freedom. This heightened awareness would thus begin to form part of their personal education process.

References

Adam, J.M. & Bonhomme, M. (2000). La argumentación publicitaria. Retórica del elogio y de la persuasión. Madrid: Cátedra.

Bajtin, M. (1991). Teoría y estética de la novela. Madrid: Taurus.

Bermejo, J. (2013a). Nuevas estrategias retóricas en la sociedad de la neopublicidad. Icono 14, 11 (1), 99-124.

Bermejo, J. (2011a). Hiperestimulación cognitiva y publicidad. Pensar la Publicidad, 5, 2, 13-19 (http://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/PEPU/article/view/38190/36949) (07-12-2012).

Bermejo, J. (2011b). Estrategias persuasivas de la comunicación publicitaria en el marco del sistema publicitario gráfico español. Sphera Pública, 11, 21-41.

Bermejo, J. (2011c). Estrategias persuasivas en la nueva comunicación publicitaria: del ‘below the line’ al ‘off the line’. Trípodos, Extra, 219-229.

Bermejo, J. (2011d). Estrategias de comunicación en las administraciones públicas a través de la publicidad impresa. El Profesional de la Información, 20, 4, 399-405.

Bermejo, J., De Frutos, B. & Couderchon, P. (2011). The Perception of Print Ad-vertising in the New Strategies of Hybridisation of Genres. X International Conference on Research in Advertising (ICORIA). Berlín, 23-25 de junio 2011. Europa-Universität Viadrina Frankurt (Oder) y Bergische Universität Wuppertal.

Dagnaud, M. (2003). Enfants, consommation et publicité télévisée. Paris: La Documentation Française.

Eysenck, M.W. & Keane, M.T. (2000). Cognitive Psychology. Hove: Psychology Press.

Froufe, M., Sierra, B. & Ruiz, M.A. (2009). El inconsciente cognitivo en la psicología científica del siglo XXI. Extensión Digital, 1, 1-22.

Gunter, B., Oates, C. & Blades, M. (2005). Advertising to Children on TV: Content, Impact and Regulation. Mahwah, New Jersey: LEA.

Harris, J.L., Bargh, J.A. & Brownell, K.D. (2009). Priming Effects of Television Food Advertising on Eating Behavior. Health Psychology, 28, 4, 404-413.

Hassin, R., Ulleman, J. & Bargh, J. (Eds.) (2005). The New Unconscious. New York: OUP.

Heath, R. (2007). Emotional Persuasion in Advertising: A Hierarchy-of-Processing Model. (http://opus.bath.ac.uk) (07-12-2012).

Heath, R. (2012). Seducing the Subconscious. The Psychology of Emotional Influence in Advertising. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Heath, R., Nairn, A.C. & Bottomley, P. (2009). How Effective is Creativity? Emotive Content in TV Advertising does not Increase Attention. Journal of Advertising Re-search, 49 (4), 450-463.

Heylighen, F. (2012). Complexity and Information Overload in Society: Why Increasing Efficiency Leads to Decreasing Control (http://pespmc1.vub.ac.be/Papers/Info-Overload.pdf) (14-12-2012).

Jeong, S.H. & Fishbein, M. (2007). Predictors of Multitasking with Media : Media Factors and Audience Factors. Media Psychology, 10, 3, 364-384.

Kapferer, J.N. (1985). L’enfant et la publicité. Paris: Dunod.

Klingberg, T. (2009). The Overflowing Brain: Information Overload and the Limits of Working Memory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Knowles, E.S & Linn, J.A. (2004). Resistance and Persuasion. Mahwah, New Jersey: LEA.

Linell, P. (1998). Approaching Dialogue. Talk, Interaction and Contexts in Dialogical Perspective. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Martí-Parreño, J. (2010). Funny Marketing. Madrid: Wolters Kluwer.

Martínez-López, J.S. (2011). Sociedad del entretenimiento: Construcción socio-histórica, definición y caracterización de las industrias que pertenecen a este sector. Revista Luciérnaga, III, 6, 6-16.

Minot, F. & Laurent, S. (2002).Les enfants et la publicité télévisée. Paris: Documenta-tion Française.

Moore, T.E. (1982) Subliminal Advertising: What you See is What you Get. Journal of Marketing, 46, 2, 38-47.

Nabi, R. & Beth, M. (2009). Media Processes and Effects. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Ophir, E., Nassb, C. & Wagnerc, A.D. (2009). Cognitive Control in Media Multitaskers. PNAS, 106, 35, 15.583-15.587.

Pérez-Tornero, J.M. (2008). La sociedad multipantallas: retos para la alfabetización mediática. Comunicar, 31, XVI, 15-25. (DOI:10.3916/c31-2008-01-002).

Petrova, P.K., Cialdini, R.B., Goldstein, N.J. & Griskevicius, N. (2012). Protecting Consumers from Harmful Advertising: What Constitutes an Effective Counter Ar-gument? (www.mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu) (19-12-2012).

Sanagustin, E. (2009). Claves del nuevo marketing. Barcelona: Gestión 2000.

Sayre, S. & King, C. (2010). Entertainment and Society: Influences, Impacts, and Innovations. New York: Routledge.

Shapiro, S., Macinnis, D.J. & Heckler, S.E. (1997). The Effects of Incidental ad Exposure on the Formation of Considerations Sets. Journal of Consumer Research, 24, 94-104.

Shrum, L.J. (Ed.). (2004). The Psychology of Entertainment Media : Blurring the Lines between Entertainment and Persuasion. Mahwah NJ: LEA.

Solana, D. (2010). Postpublicidad. Reflexiones sobre una nueva cultura publicitaria. Barcelona: Doubleyou.

Trappey, C. (1996). A Meta-Analysis of Consumer Choice. Psychology and Marketing, 13, 517-530

Wright, P.L. (1980). Message-Evoked Thoughts: Persuasion Research Using Thought Verbalizations. Journal of Consumer Research, 7, 151-175.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Young people today live in a media culture where the content they access and circulate through by means of different audiovisual technological devices is part of their informal education. In this context, the traditional advertising inserted into these media is giving way to new strategies through which advertising is masked within other content consumed by young people. They believe they are sufficiently wellinformed to consider advertising's influence on them to be relative, and claim to be equipped with effective strategies that immunize them against it. However, as argued in this article, current advertising is implementing new persuasive forms that go unnoticed. We present an empirical investigation involving 154 students. Through an interactive computing device, the students processed a total of 223 stimuli corresponding to a graphic communication medium. The dependent variables include the degree of success in identifying the presence of advertising in the stimuli and reaction time. The results show how new masking strategies in advertising hinder young people's awareness that they are receiving advertising messages. This facilitates a failure to create counterarguments. The results of this work open up the discussion of whether it is relevant to make known to young people, as part of their education and training, these current effective advertising strategies deriving from informal education systems.

1. Introducción: de la publicidad clásica a la publicidad enmascarada

Al comienzo del siglo XXI parecía que la publicidad había sido suficientemente desenmascarada por los jóvenes. Sus mensajes explícitos, ubicados en espacios perfectamente delimitados en los medios de comunicación, eran suficientemente bien conocidos e identificables por los jóvenes, dado el aprendizaje informal de sus códigos desde la infancia. Saber dónde estaba la publicidad les permitía desplegar su contraargumentación para así intentar contrarrestar su eventual influencia persuasiva. Como concluye Kapferer (1985: 34), a partir de una revisión de estudios empíricos, «el niño adquiere, ya desde los tres años, los códigos que le permiten diferenciar la publicidad de lo que no es publicidad». Sin embargo, las cosas están cambiando de manera acelerada en los últimos años. La publicidad está modificando su manera de dirigirse a los jóvenes. Su eficacia renovada se ve favorecida por el actual contexto de relación de éstos con los dispositivos técnicos y tecnológicos. En este entorno cultural multipantalla (Pérez-Tornero, 2008), de comunicación bidireccional y multidireccional, destacan algunos rasgos que contribuyen a configurar su educación informal. En primer lugar, los jóvenes viven inmersos en una cultura del entretenimiento audiovisual (Martínez, 2011). Utilizan los medios para informarse pero sobre todo para entretenerse, haciéndolo con una actitud de confianza pues, en general, se considera que sus contenidos están al servicio del disfrute y no de la persuasión (Shrum, 2004; Nabi & Beth, 2009; Sayre & King, 2010). En segundo lugar, favorecido por las nuevas tecnologías, hay un marco de hiperestimulación cognitiva (Klingberg, 2009). Basta imaginar los estímulos que recibe un paseante hoy en una ciudad en comparación con los que recibía a principios del siglo pasado (Bermejo, 2011a). En tercer lugar, el fenómeno anterior, de hiperestimulación cognitiva, se acompaña con el aumento de las multitareas o tareas duales (dual-tasking). Una de las consecuencias de estar muy frecuentemente conectado trae consigo que la cantidad de estímulos que llegan al joven hoy es mayor que hace algunos años (Klingberg, 2009). En la actualidad no es infrecuente observar jóvenes pendientes de su móvil mientras hacen otras actividades escolares o son interrumpidos por la abrupta llegada de un mensaje a su teléfono; universitarios que asisten a clase y, al mismo tiempo, tienen delante de sí sus ordenadores conectados a Internet (Jeong & Fishbein, 2007). Este conjunto de fenómenos introduce, en la vida de los jóvenes, nuevas formas de movilizar los diferentes tipos de atención. La duración de los períodos de atención voluntaria o controlada (controlled attention), que dependen de un esfuerzo consciente para ejecutar una tarea (por ejemplo, atender en clase o estudiar), se ven reducidos por la llegada de estímulos externos, cada vez más abundantes, que la interrumpen y hacen intervenir la atención involuntaria (stimulus-driven attention). Esta última hace que cambiemos nuestro objeto de atención actual por otro distinto que irrumpe en nuestro campo estimular. Dado que nuestra capacidad de procesamiento es limitada, la memoria de trabajo (working memory) ha de repartir sus escasos recursos entre varias estimulaciones, disminuyendo así su capacidad para procesar con total pertinencia todos los estímulos a los que se está atendiendo simultáneamente. Un dato que aporta la investigación actual es que, cuanto más cargada está la memoria de trabajo, al tener que atender varios estímulos al mismo tiempo, mayores son las dificultades para concentrarse por medio de la atención controlada, y mayores son las posibilidades tanto de distraerse como de procesar superficialmente los estímulos que compiten entre sí por acaparar nuestra atención (Ophir & al., 2009; Heylighen, 2008). En este contexto cultural multi-estimular hay que crear hábitos atencionales que afectan ulteriormente también a los procesos atencionales que requiere la educación formal en la escuela, y que explica en parte la observación de algunos docentes que se quejan de la actual falta de atención de sus estudiantes durante períodos prolongados.

En este marco cultural, la publicidad, que ha visto cómo la atención hacia sus mensajes ha ido disminuyendo en los medios de comunicación convencionales, está a la búsqueda de nuevas formas de atraer la atención de los consumidores (Heath, 2012). Está dirigiendo sus mayores esfuerzos y atención hacia los nuevos medios, particularmente en Internet, en la denominada sociedad de la post-publicidad (Solana, 2010). El nuevo marketing atrae la atención de los investigadores, en parte por la novedad, y también porque los jóvenes se exponen a él a través de Internet y las redes sociales (Sanagustin, 2009) y las nuevas actividades de entretenimiento virtual audiovisual (Martí, 2010). Ello está haciendo olvidar que los medios de comunicación convencionales, que siguen estando muy presentes, también están evolucionando. Están a la búsqueda de nuevas estrategias para manejar la atención y atraer así a los targets en renovadas formas de persuasión. Recordemos que la publicidad clásica, inserta en los medios de comunicación convencionales, se ha caracterizado por utilizar, a lo largo del siglo XX, una estrategia persuasiva dirigida a captar la atención consciente y voluntaria de sus destinatarios. Consideraba que una vez que había conseguido atraerles hacia su mensaje, su contenido podía persuadirles. Este tipo de publicidad, hoy todavía mayoritariamente vigente, tiene unos rasgos bien definidos. Uno de los más característicos es su clara delimitación de género. Su inserción en un espacio bien circunscrito en los medios de comunicación que los acoge hace que no haya mezcla de géneros. En prensa tiene su espacio en la página separado de noticias y reportajes mediante marcos. En radio o televisión tiene igualmente sus bloques publicitarios con códigos bien establecidos que son aprendidos desde los primeros años de la infancia (Minot & Laurent, 2002; Dagnaud, 2003, Gunter & al., 2005). Un segundo rasgo de la publicidad clásica es la de simular un proceso dialógico (Bajtin, 1991; Linell, 1998, Adam & Bonhomme, 2000). El diálogo en la vida cotidiana implica una comunicación bidireccionalidad entre los interlocutores y participantes en el diálogo. Sin embargo, la publicidad, únicamente puede dirigir mensajes unidireccionales a través de medios de comunicación convencionales, y por tanto no puede establecer, en sentido estricto, comunicación bidireccional y, en consecuencia, diálogo real. No obstante, ello no le ha impedido simular en sus mensajes un diálogo directo con su público como si realmente hubiera bidireccionalidad (Bermejo, 2013a). Junto a esta publicidad clásica, está apareciendo en la actualidad una nueva publicidad. Así, recientemente hemos podido identificar una nueva estrategia persuasiva publicitaria en los medios de comunicación gráficos actuales, que hemos denominado de enmascaramiento, y que no había sido detectada hasta ahora (Bermejo & al., 2011). Ésta interpela nuestra atención de manera diferente a como venía haciendo la publicidad hasta ahora, dirigiéndose a la atención involuntaria y no a la atención voluntaria. Esta estrategia se caracteriza por el borrado de códigos de género, la hibridación de géneros por inserción y ocultamiento de la publicidad en otros géneros comunicacionales y, en tercer lugar, por la puesta en escena de una nueva dialogicidad (Bermejo, 2013a). En esa investigación previa hemos identificado la presencia de tres tipos de nueva publicidad gráfica en los medios de comunicación escritos en España que constituyen tres manifestaciones de esta estrategia persuasiva de enmascaramiento. Las hemos denominado publicidad integrada, neopublirreportaje y publicidad autorreferencial.

Las tres modalidades de publicidad enmascarada se caracterizan porque el sujeto accede a un texto de naturaleza informativa en el que se encuentra incorporado un mensaje publicitario que, al no estar destacado o delimitado por códigos que lo independicen como texto autónomo, aparece disimulado en el texto que lo acoge. Un ejemplo de publicidad integrada lo podemos encontrar en entrevistas a famosos y personajes públicos. En el artículo, a medida que el entrevistado responde a las preguntas del entrevistador, el personaje cuenta aspectos de su vida que incluye, en estos casos, alusiones personales al consumo de productos y marcas concretos. En segundo lugar, si los publirreportajes ya se utilizaban en la publicidad convencional, hay dos rasgos en el neopublirreportaje que lo diferencian de aquellos. Uno es que desaparece el código identificador de género, ubicado en el encabezado de la página o del recuadro del texto publicitario, en el que se podía leer la palabra «publirreportaje» y que advertía al lector acerca del contenido. Un segundo rasgo es que los neopublirreportajes se presentan al lector con la apariencia de verdaderos reportajes informativos en los que se trata de informar al lector sobre algún asunto monográfico que le interesa (por ejemplo, cómo preparar una cena navideña, qué regalos hacer o cómo luchar contra la caída del cabello, etc.). A lo largo del texto, se van haciendo alusiones de productos y marcas que pueden ayudar al lector a resolver su problema o necesidad informativa. Por tanto, el mensaje publicitario no aparece en este tipo de texto sino en un momento preciso y a modo de sugerencia que acompañe al lector en la decisión acerca del asunto que le llevó a leer el artículo de prensa. Por último, al igual que en el caso anterior, la publicidad autorreferencial borra los códigos que permiten al lector percibir y categorizar de inmediato el texto y adscribirlo al género de promoción o autopromoción convencional. Si en la publicidad clásica la autopromoción era un texto explícito en el que se invitaba al lector a consumir el producto o servicio, en la nueva publicidad autorreferencial se presenta un texto de interés para el lector y, en su interior, se deslizan mensajes, sean icónicos o redaccionales, de autopromoción. Por ejemplo, en la revista «Cosmopolitan» (número 243; páginas 82-93), objeto de la investigación empírica más abajo, el lector encuentra fotos y descripciones de una fiesta a la que asistieron numerosos personajes públicos, cantantes y actores, entre otros. Como tela de fondo de varias fotografías, en las que posan los famosos para las cámaras, puede verse de manera nítida el logosímbolo del organizador del evento, a saber, la revista «Cosmopolitan», así como alusiones explícitas a la marca. Si el acento del texto está puesto en el glamour del evento y en satisfacer la eventual curiosidad del lector de, entre otras cosas, conocer los vestidos y atuendos de los asistentes, esta fiesta está sutilmente acompañada en todo momento de la marca promotora, que hizo posible el acontecimiento (Bermejo, 2013a).

Esta nueva estrategia de enmascaramiento publicitario, a través de estas tres modalidades que hemos podido identificar, se dirige a la atención involuntaria y no ya a la atención voluntaria como hacía la publicidad clásica. La cuestión que se plantea es conocer cómo reaccionan los jóvenes a este tipo de estrategia publicitaria y la eventual influencia persuasiva que puede tener en ellos. En el presente artículo presentamos los resultados de una investigación que indaga por primera vez, de manera empírica, la influencia de esta nueva estrategia publicitaria de enmascaramiento sobre la juventud.

2. Estudio experimental del enmascaramiento publicitario

2.1. Material y métodos

En un estudio previo, en 2011, hemos indagado la presencia de la nueva publicidad gráfica en el conjunto de la publicidad en España. Analizados todos los tipos y categorías de publicaciones existentes en el mercado nacional que insertan publicidad y que pueden ser adquiridas en quioscos y librerías, se seleccionó un corpus representativo que cubría 232 publicaciones, con un total de 26.930 páginas, de las cuales 7.183 incluían publicidad, arrojando un total de 7.771 anuncios (Bermejo, 2011d). El análisis de este corpus de anuncios ha puesto en evidencia que esta nueva estrategia de enmascaramiento ya está bastante presente en prensa y representa una cuarta parte del total, adicionadas sus tres modalidades de manifestación, integrada, neopublirreportaje y autorreferencial (Bermejo, 2011c).

Como se recoge en el gráfico 2, aun cuando las tres modalidades de nueva publicidad (neopublicidad) aparecen en la mayoría de las categorías de publicación, es interesante observar que se concentran sobre todo en algunas categorías que tienen elementos comunes: Juventud (que incluye revistas como «Loka Magazine», «Super Pop», «Ragazza», «Bravo por Ti», etc.) que alcanza el 87,9% del total de anuncios de las publicaciones incluidas en esta categoría; «Erotismo (79%)» «Moda» (con publicaciones como «Elle», «Tendencias», «Glamour», «Vogue», «Telva»...), que representa el 43,6%; Suplementos de Moda en periódicos, como «Dona», el 41,1%; «Sociedad» (con más de veinte publicaciones entre las que se encuentran: «Lecturas», «Cosmopolitan», «Pronto», «Hola») que supone el 39,2%. Estas cinco categorías de publicaciones tienen que ver con las relaciones interindividuales en el marco social, con las tendencias, valores y usos sociales. En muchas de ellas se incluyen patrones de conducta, valores y acciones sociales a los que se asocia publicidad, según el modo camuflado de las tres modalidades de nueva publicidad, descritas más arriba. Por tanto, esta nueva estrategia persuasiva de enmascaramiento tiene ya una presencia importante en la publicidad gráfica, encontrándose prácticamente en todas las categorías de publicación. Una interesante conclusión que se desprende de este estudio es que esta publicidad enmascarada aparece significativamente en publicaciones consumidas por los jóvenes. Un objetivo general que se plantea a partir de este resultado es conocer si ese nuevo tipo de publicidad les influye.

2.2. Objetivos

El objetivo general de la investigación es verificar si los sujetos, al ser expuestos a la lectura de una revista que inserta publicidad, de venta en quioscos y librerías, perciben e identifican con el mismo grado de dificultad los cuatro tipos de publicidad: clásica, integrada, neopublirreportaje, autorreferencial. Se trata de conocer si el factor de enmascaramiento, ausente en la publicidad clásica y presente con vías de expresión diferentes, en los otros tres tipos de publicidad, influye en su capacidad para identificar la presencia de la publicidad en esas páginas. El enmascaramiento se ha utilizado como técnica experimental para diferenciar el procesamiento consciente e inconsciente de los estímulos (Froufe & al., 2009). En nuestro caso, entendemos por enmascaramiento aquel proceso utilizado, no en el laboratorio, sino en el entorno social, por un nuevo tipo de publicidad que consiste en borrar los marcadores de género, incluir el mensaje publicitario dentro del texto de otro género informativo que lo acoge y, en tercer lugar, establecer un tipo de dialogicidad específico, descrito más arriba.

Para la presente investigación, se ha seleccionado como material estimular, la revista Cosmopolitan, perteneciente a la categoría de publicaciones de sociedad, porque en ella se encuentra, de manera abundante, tanto la publicidad clásica como la nueva publicidad, y además, porque forma parte de una categoría genérica de publicaciones, junto a las publicaciones de juventud, a las que los jóvenes hoy se exponen con asiduidad.

2.3. Procedimiento experimental

Participan en la investigación un total de 154 estudiantes universitarios de Publicidad y Relaciones Públicas de último curso, cuyas edades están comprendidas entre los 21 y los 23 años. La muestra, formada por un 24,7% de chicos y un 75,3% de chicas, ha sido seleccionada al considerarse un grupo experto, familiarizado con los mensajes publicitarios en los medios y, por tanto, en relación al que cabría esperar que no tuviera dificultad para identificar publicidad en medios convencionales escritos.

En la situación experimental, los participantes realizan la tarea de forma individual en un ordenador en el que se ha incorporado el programa SuperLab 4.1, que permite registrar las respuestas del usuario. Durante la sesión, el sujeto visualiza 224 pantallas correspondientes a cada una de las páginas, incluidas portada y contraportada, del número 243 de la revista de sociedad «Cosmopolitan». La tarea que se le indica en la consigna, en relación a esta variable independiente, es que presione en el teclado bien la letra S, si la página que está visionando contiene publicidad, bien la letra N, si la página no contiene publicidad. Al introducir la respuesta se pasa a la pantalla siguiente y así sucesivamente. Antes de comenzar, y en relación a las variables dependientes consideradas, se informa al sujeto que se tomará en cuenta en su respuesta tanto su grado de acierto en la identificación de la presencia de publicidad en la página como el tiempo que tardan en responder (tiempo de reacción en milisegundos, registrado por el software instalado en el ordenador).

Una selección y clasificación previa de la publicidad de la revista arrojó un conjunto de 155 estímulos publicitarios (es decir, 155 de las 224 pantallas contenían publicidad). Esos 155 estímulos se clasifican en 7 tipologías o modalidades publicitarias, resultantes de la toma en consideración de dos variables del estímulo: a) tipo de publicidad y b) cantidad de espacio ocupado por el anuncio en la página. La tabla 1 recoge la distribución de las 224 páginas de la revista en función de estos dos criterios. Las categorías T2, T3 y T4 corresponden a estímulos que incluyen publicidad clásica. Las siguientes cuatro categorías (T5 a T8) corresponden a los tres tipos de nueva publicidad. En estos cuatro tipos se incluyen la publicidad autorreferencial, el publirreportaje, la publicidad integrada dentro del texto a página completa y, por último, la publicidad integrada en el texto de forma parcial ocupando media página o un cuarto.

Para que el diseño experimental estuviera equilibrado respecto al número de estímulos se han utilizado en el análisis estadístico siete páginas correspondientes a cada una de las siete categorías de estímulos publicitarios, excepto la categoría de página integrada por un cuarto con cinco ítems.

2.4. Hipótesis

La hipótesis general es que existe una percepción diferencial entre los cuatro tipos de publicidad descritos más arriba.

H1: La publicidad clásica se percibe mejor que la nueva publicidad (autorreferencial, neopublirreportaje, integrada), es decir, el grado de acierto en la identificación de la publicidad clásica es superior al de la publicidad enmascarada. Ello implica que, siendo superior la tasa de acierto en la publicidad clásica, una parte de la nueva publicidad pasa desapercibida.

H2: El sujeto tarda menos tiempo en identificar la publicidad clásica que la nueva publicidad. Este segundo registro suplementario hace poner de manifiesto las dificultades del sujeto para percibir en el texto gráfico la publicidad enmascarada.

3. Resultados: la eficacia persuasiva del enmascaramiento publicitario sobre los jóvenes

El primer análisis se ha efectuado sobre la proporción de acierto en la identificación correcta de la página con publicidad. La modalidad publicitaria muestra claras diferencias en la proporción de personas que identifican correctamente la presencia de publicidad en la página de la revista. Las dos primeras tipologías de publicidad T2 y T3 se identifican correctamente en un 99,1% y un 90,2% de los casos (Tabla 2). Con una tasa de acierto algo inferior se encuentra la publicidad que ocupa una fracción de la página (T4), que obtiene un 87,2% de identificaciones correctas. Por lo tanto, estas categorías de publicidad clásica no presentan ningún tipo de problema en la categorización como publicidad por parte de los sujetos. En cambio, las otras cuatro categorías de estímulos, correspondientes a la publicidad enmascarada, muestran una proporción de acierto sensiblemente inferior como se puede apreciar en la tabla. La publicidad autorreferencial tiene un porcentaje de acierto del 66,7%, el neopublirreportaje obtiene un 57,9%, y la publicidad integrada en el texto obtiene un 64,1% y un 62,6% respectivamente. Las cuatro tipologías representan estímulos publicitarios en formatos o formas de presentación menos evidentes en la categorización publicitaria. Para tener constancia de las diferencias se ha llevado a cabo un análisis de varianza (ANOVA) de medidas repetidas y se ha comprobado que estas diferencias son estadísticamente significativas (F=150,85, sig.=.000). Por tanto, la hipótesis 1 se confirma y hace aparecer una percepción diferencial entre los dos tipos de publicidad.

El tiempo de reacción es la segunda variable registrada en el análisis y refleja el grado de procesamiento requerido para dar la respuesta en cada estímulo. En la tabla 2 se muestran los resultados obtenidos para cada tipo de estímulo. Se puede apreciar el incremento en el tiempo medio dedicado al procesamiento de la imagen, antes de dar una respuesta, a medida que se pasa de la publicidad clásica a la nueva publicidad. Así, en el anuncio a página completa el tiempo medio ha sido de 9,26 segundos, la categoría que recoge varios anuncios publicitarios en la misma página obtiene un procesamiento medio ligeramente superior (15,26 segundos), y algo superior en la siguiente con 16,40 segundos. Los otros cuatro tipos de estímulos restantes, correspondientes a neopublicidad, muestran un incremento sustancial en el tiempo dedicado al procesamiento, puesto que su tiempo de reacción medio se sitúa entre los 22,2 y los 24,64 segundos. De nuevo se ha realizado un análisis de varianza (ANOVA) de medidas repetidas y se ha comprobado que las diferencias entre las siete categorías son estadísticamente significativas (F=189,3; sig.=.000). De hecho, un segundo análisis de varianza de medidas repetidas realizado sobre las últimas cuatro categorías publicitarias no muestran diferencias estadísticamente significativas (F=2,687; sig. =.055). El análisis de esta segunda variable evidencia que la disminución en la tasa de acierto de estas categorías publicitarias de la nueva publicidad no se debe a una falta atencional, puesto que claramente los sujetos han empleado más tiempo en emitir una respuesta. En consecuencia, se puede deducir que la dificultad de clasificación ha demandado mayores recursos cognitivos a los participantes en la investigación. Esa dificultad es mayor, como acabamos de ver, para la publicidad enmascarada.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

Los resultados de esta investigación suscitan una discusión en torno a cuatro cuestiones. La primera se refiere al cambio en las estrategias persuasivas utilizadas por la publicidad para comunicar con los jóvenes y que estarían pasando de dirigirse no tanto a la conciencia sino al subconsciente. Es necesario recordar que subconsciente no es lo mismo que subliminal. Este último tipo de estimulación opera por debajo del nivel de procesamiento sensible y, como aparece en la investigación y metaanálisis, la influencia de la publicidad subliminal sobre las decisiones de los consumidores es insignificante (Moore, 1982; Trappey, 1996). En cambio, un proceso subconsciente tiene lugar cuando la publicidad puede ser vista u oída, aunque no atraiga la atención del sujeto (Heath, 2007: 22). A diferencia de la publicidad subliminal, investigaciones como la de Shapiro, Macinnis y Heckler (1997), han confirmado empíricamente que el procesamiento subconsciente de la publicidad puede influir sobre las decisiones de compra.

Hasta hace poco tiempo existía una concepción según la cual asimilábamos solo aquello que había pasado por nuestra conciencia. Ello hacía que la estrategia publicitaria haya buscado atraer la atención consciente de su público. Se pensaba que lo retenido a través de esta vía podía ser recuperado de la memoria y, de esa forma, influir sobre las actitudes favorables hacia la marca. Por el contrario, aquello que no se procesaba por esta vía voluntaria se perdía y no influía en nuestra conducta ulterior. Según esta concepción, la interpretación de los resultados de esta investigación sería que la publicidad enmascarada no sería eficaz, es decir, no influiría en la mente del lector, dado que no había sido percibida de manera consciente. Sin embargo, los recientes avances en psicología y neurociencias han puesto de manifiesto que existen tres vías de procesamiento del estímulo que pueden influir ulteriormente en nuestra conducta (Klingberg, 2009; Heath, 2012). Hay un aprendizaje activo (active learning), que tiene lugar a través de la atención voluntaria o consciente de alta intensidad (high attention), que utiliza comúnmente una vía foveal. Existe, en segundo lugar, un aprendizaje pasivo (passive learning) que se produce por medio de la atención de baja intensidad (low attention), que utiliza sobre todo la vía parafoveal. Existe por último, un tercer tipo de atención periférica que conduce al denominado aprendizaje implícito (implicit learning) que se produce sin que el sujeto atienda al estímulo de cualquiera de las otras dos formas de atención. Según este tercer tipo de aprendizaje, el sujeto puede no tener conciencia de haber percibido un estímulo y, a pesar de ello, haberlo asimilado tanto sensorial como conceptualmente (Shapiro & al., 1997). A la luz de estos avances en el conocimiento de los procesos atencionales y de aprendizaje que indican que se puede producir aprendizaje implícito a través de procesos atencionales de bajo nivel y periféricos, la interpretación de los resultados de la presente investigación se puede abordar desde sus eventuales efectos persuasivos sobre los jóvenes. Dado el contexto de exposición, donde el sujeto es invitado explícitamente a mirar imágenes en pantalla y tomar decisiones en relación a ellas, tenemos una tarea cuyos requerimientos de procesamiento general son conscientes y voluntarios, demandan un alto nivel atencional (higt attention) en un proceso descendente (top-down processing) controlado por los objetivos (Eysenk & Keane, 2000: 2). Sin embargo, lo interesante es que, a pesar de este contexto preciso, una parte significativa de los sujetos procesan los estímulos con una atención de baja intensidad (low attention). Es como si, de hecho, su procesamiento efectivo hubiera seguido una estrategia de atención pasiva ascendente (bottom-up processing) en la que el aprendizaje se produce de manera inadvertida y es controlada por los estímulos y no ya por los objetivos del sujeto. Ello explica que hayan cometido errores que, de haber aumentado su nivel atencional, no se hubieran producido dado su nivel previo de expertos publicitarios. La incorrecta respuesta verbal de nuestros sujetos indica que no han procesado con el nivel suficiente la presencia en el estímulo de buena parte de la publicidad enmascarada. Sin embargo, ello no quiere decir que no la hayan procesado. Este habría tenido lugar en modo de baja intensidad e incluso subconsciente, a través de una atención periférica. Como la literatura científica, mediante el estudio del efecto priming, ha podido poner de manifiesto, estímulos procesados mediante aprendizaje implícito pueden tener efectos ulteriores sobre la conducta, aunque no se manifiesten a través del esfuerzo consciente de recuperar la información (Harris & al., 2009). Por tanto, este cambio de estrategia que la publicidad está experimentando, que le está llevando desde el empleo de estrategias dirigidas a la conciencia hacia estrategias dirigidas al subconsciente y el aprendizaje implícito, pueden tener una alta eficacia publicitaria pues, como hemos mostrado aquí, pasan desapercibidas para nuestros sujetos.

La segunda cuestión que suscitan estos resultados es que desvelan una nueva forma de relación con el lector. La dialogicidad de la publicidad clásica ha venido utilizando un proceso de diálogo directo. Una vez conseguida la atención del lector y, a partir de ahí, despliega estrategias argumentativas centradas en la fuente y en el mensaje donde el enunciador presenta una promesa en torno a la marca/producto (Bermejo, 2011 b). En cambio, el tipo de publicidad enmascarada que hemos identificado utiliza otra forma de dialogicidad. En ella se articula una comunicación en torno a un asunto o tema informativo que interesa al lector. En ese proceso, siendo este el eje central de la comunicación, el producto o la marca queda desplazado, aunque no ausente. El diálogo simulado en la publicidad clásica es sustituido en la publicidad enmascarada por un encuentro dialógico en torno a un contenido que atrae al lector (Bermejo, 2013a). Al mismo tiempo, en este nuevo contexto comunicacional, el eje dicotómico racional-emocional pasa a segundo plano en beneficio de los procesos atencionales y de condicionamiento, según el mecanismo ya puesto en evidencia por Paulov y reafirmado por la psicología y las neurociencias contemporáneas (Health, 2012). Como este autor ha mostrado experimentalmente, la cuestión ya no es tanto si la publicidad es más racional o emocional sino el contexto perceptivo en el que tiene lugar la exposición a ella que induce un determinado grado de procesamiento y contraargumentación (Heath & al., 2009).

En tercer lugar, si, como indican estos resultados, la estrategia del enmascaramiento hace que pase desapercibida a la conciencia la publicidad en el medio de comunicación, el individuo puede acabar teniendo la impresión de que la publicidad, extremadamente invasiva durante los últimos años del siglo XX, estaría comenzado a salir de los media. Pero esto, como hemos visto, no sería sino una ilusión pues sigue estando presente. Una de las consecuencias de esta ausencia de percepción es que el individuo se relaja y no adopta actitudes de defensa y contraargumentación contra los mensajes publicitarios enmascarados. Como sabemos desde hace tiempo, la contraargumentación es una poderosa variable mediadora en la respuesta de aceptación del mensaje (Wright, 1980; Knowles & Linn, 2004; Petrova & al., 2012). Cuando el sujeto contraargumenta, la probabilidad de ser persuadido disminuye pues su respuesta cognitiva es contraria a los argumentos del mensaje publicitario. El despliegue de la estrategia de enmascaramiento en otros medios de comunicación puede traer consigo, paradójicamente, que la persuasión publicitaria sea, en el futuro, todavía más eficaz que hasta ahora pues el sujeto, al no percibir conscientemente el estímulo, no ve la necesidad de contraargumentar.

Finalmente, y no menos importante, de esta investigación se desprende una reflexión acerca de las competencias mediáticas de los jóvenes en esta nueva era de la comunicación multicanal. El reciente redescubrimiento del denominado inconsciente cognitivo (Hassin & al., 2005; Froufe & al., 2009) nos ha hecho ver que también somos capaces de procesar información presentada por vía periférica, sin tomar conciencia de ella. Si la presente investigación es una ilustración de este fenómeno, este nuevo conocimiento sobre nuestras capacidades, ya utilizado por la publicidad, plantea la eventual necesidad de dar a conocer a los jóvenes estos procedimientos comerciales, que se dirigen no ya a la atención consciente sino a la atención periférica, para que adopten, a partir de ese conocimiento, sus decisiones individuales, con un mayor grado de libertad. Esta toma de conciencia entraría así a formar parte de su proceso de educación personal.

Referencias

Adam, J.M. & Bonhomme, M. (2000). La argumentación publicitaria. Retórica del elogio y de la persuasión. Madrid: Cátedra.

Bajtin, M. (1991). Teoría y estética de la novela. Madrid: Taurus.

Bermejo, J. (2013a). Nuevas estrategias retóricas en la sociedad de la neopublicidad. Icono 14, 11 (1), 99-124.

Bermejo, J. (2011a). Hiperestimulación cognitiva y publicidad. Pensar la Publicidad, 5, 2, 13-19 (http://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/PEPU/article/view/38190/36949) (07-12-2012).

Bermejo, J. (2011b). Estrategias persuasivas de la comunicación publicitaria en el marco del sistema publicitario gráfico español. Sphera Pública, 11, 21-41.

Bermejo, J. (2011c). Estrategias persuasivas en la nueva comunicación publicitaria: del ‘below the line’ al ‘off the line’. Trípodos, Extra, 219-229.

Bermejo, J. (2011d). Estrategias de comunicación en las administraciones públicas a través de la publicidad impresa. El Profesional de la Información, 20, 4, 399-405.

Bermejo, J., De Frutos, B. & Couderchon, P. (2011). The Perception of Print Ad-vertising in the New Strategies of Hybridisation of Genres. X International Conference on Research in Advertising (ICORIA). Berlín, 23-25 de junio 2011. Europa-Universität Viadrina Frankurt (Oder) y Bergische Universität Wuppertal.

Dagnaud, M. (2003). Enfants, consommation et publicité télévisée. Paris: La Documentation Française.

Eysenck, M.W. & Keane, M.T. (2000). Cognitive Psychology. Hove: Psychology Press.

Froufe, M., Sierra, B. & Ruiz, M.A. (2009). El inconsciente cognitivo en la psicología científica del siglo XXI. Extensión Digital, 1, 1-22.

Gunter, B., Oates, C. & Blades, M. (2005). Advertising to Children on TV: Content, Impact and Regulation. Mahwah, New Jersey: LEA.

Harris, J.L., Bargh, J.A. & Brownell, K.D. (2009). Priming Effects of Television Food Advertising on Eating Behavior. Health Psychology, 28, 4, 404-413.

Hassin, R., Ulleman, J. & Bargh, J. (Eds.) (2005). The New Unconscious. New York: OUP.

Heath, R. (2007). Emotional Persuasion in Advertising: A Hierarchy-of-Processing Model. (http://opus.bath.ac.uk) (07-12-2012).

Heath, R. (2012). Seducing the Subconscious. The Psychology of Emotional Influence in Advertising. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Heath, R., Nairn, A.C. & Bottomley, P. (2009). How Effective is Creativity? Emotive Content in TV Advertising does not Increase Attention. Journal of Advertising Re-search, 49 (4), 450-463.

Heylighen, F. (2012). Complexity and Information Overload in Society: Why Increasing Efficiency Leads to Decreasing Control (http://pespmc1.vub.ac.be/Papers/Info-Overload.pdf) (14-12-2012).

Jeong, S.H. & Fishbein, M. (2007). Predictors of Multitasking with Media : Media Factors and Audience Factors. Media Psychology, 10, 3, 364-384.

Kapferer, J.N. (1985). L’enfant et la publicité. Paris: Dunod.

Klingberg, T. (2009). The Overflowing Brain: Information Overload and the Limits of Working Memory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Knowles, E.S & Linn, J.A. (2004). Resistance and Persuasion. Mahwah, New Jersey: LEA.

Linell, P. (1998). Approaching Dialogue. Talk, Interaction and Contexts in Dialogical Perspective. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Martí-Parreño, J. (2010). Funny Marketing. Madrid: Wolters Kluwer.

Martínez-López, J.S. (2011). Sociedad del entretenimiento: Construcción socio-histórica, definición y caracterización de las industrias que pertenecen a este sector. Revista Luciérnaga, III, 6, 6-16.

Minot, F. & Laurent, S. (2002).Les enfants et la publicité télévisée. Paris: Documenta-tion Française.

Moore, T.E. (1982) Subliminal Advertising: What you See is What you Get. Journal of Marketing, 46, 2, 38-47.

Nabi, R. & Beth, M. (2009). Media Processes and Effects. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Ophir, E., Nassb, C. & Wagnerc, A.D. (2009). Cognitive Control in Media Multitaskers. PNAS, 106, 35, 15.583-15.587.

Pérez-Tornero, J.M. (2008). La sociedad multipantallas: retos para la alfabetización mediática. Comunicar, 31, XVI, 15-25. (DOI:10.3916/c31-2008-01-002).

Petrova, P.K., Cialdini, R.B., Goldstein, N.J. & Griskevicius, N. (2012). Protecting Consumers from Harmful Advertising: What Constitutes an Effective Counter Ar-gument? (www.mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu) (19-12-2012).

Sanagustin, E. (2009). Claves del nuevo marketing. Barcelona: Gestión 2000.

Sayre, S. & King, C. (2010). Entertainment and Society: Influences, Impacts, and Innovations. New York: Routledge.

Shapiro, S., Macinnis, D.J. & Heckler, S.E. (1997). The Effects of Incidental ad Exposure on the Formation of Considerations Sets. Journal of Consumer Research, 24, 94-104.

Shrum, L.J. (Ed.). (2004). The Psychology of Entertainment Media : Blurring the Lines between Entertainment and Persuasion. Mahwah NJ: LEA.

Solana, D. (2010). Postpublicidad. Reflexiones sobre una nueva cultura publicitaria. Barcelona: Doubleyou.

Trappey, C. (1996). A Meta-Analysis of Consumer Choice. Psychology and Marketing, 13, 517-530

Wright, P.L. (1980). Message-Evoked Thoughts: Persuasion Research Using Thought Verbalizations. Journal of Consumer Research, 7, 151-175.

Document information

Published on 31/05/13

Accepted on 31/05/13

Submitted on 31/05/13

Volume 21, Issue 1, 2013

DOI: 10.3916/C41-2013-15

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?